Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Parasite Cultivation

2.2. Growth Curve

2.3. Morphological Analysis

2.4. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm) Assay

2.5. Murine Peritoneal Macrophages In Vitro Infection

2.6. Amphotericin B Sensitivity Assays

2.7. In Vivo Experimental Infection Models

2.8. RT-qPCR Quantification

2.9. Sandflies Experimental Infection

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

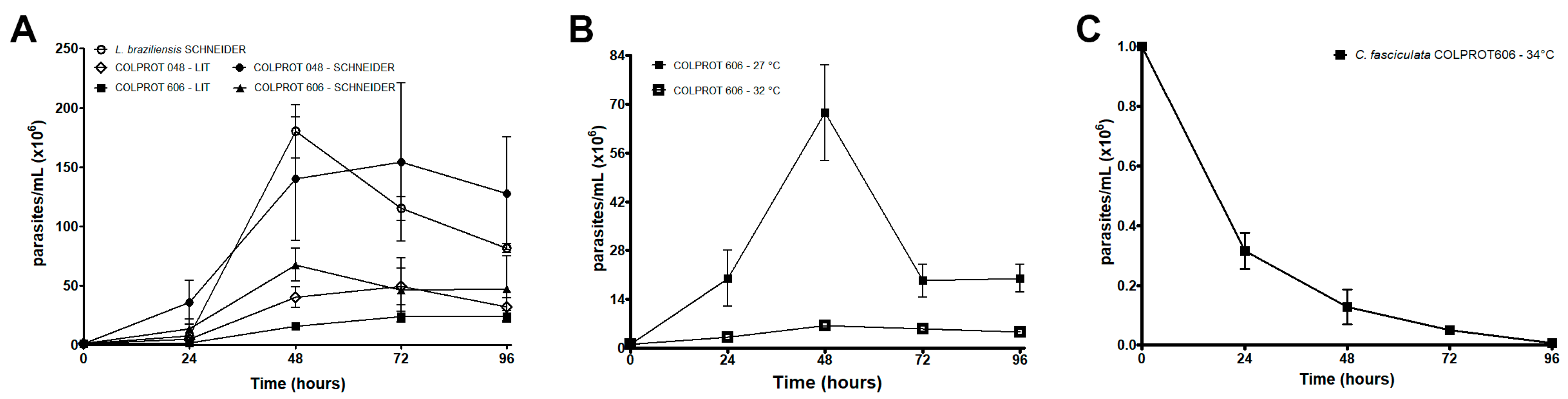

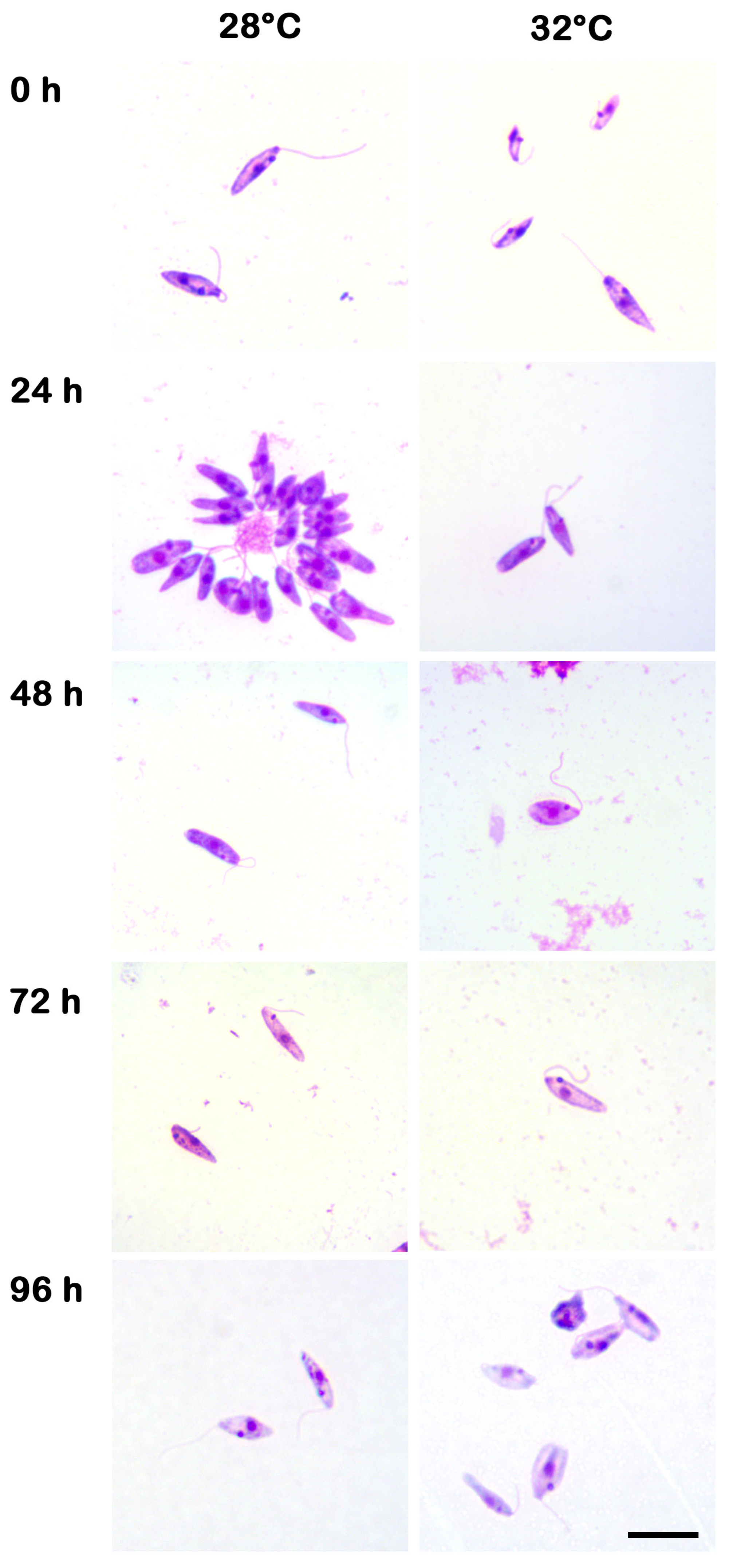

3.1. Growth Kinetics of C. fasciculata COLPROT606 and ΔΨm Analysis

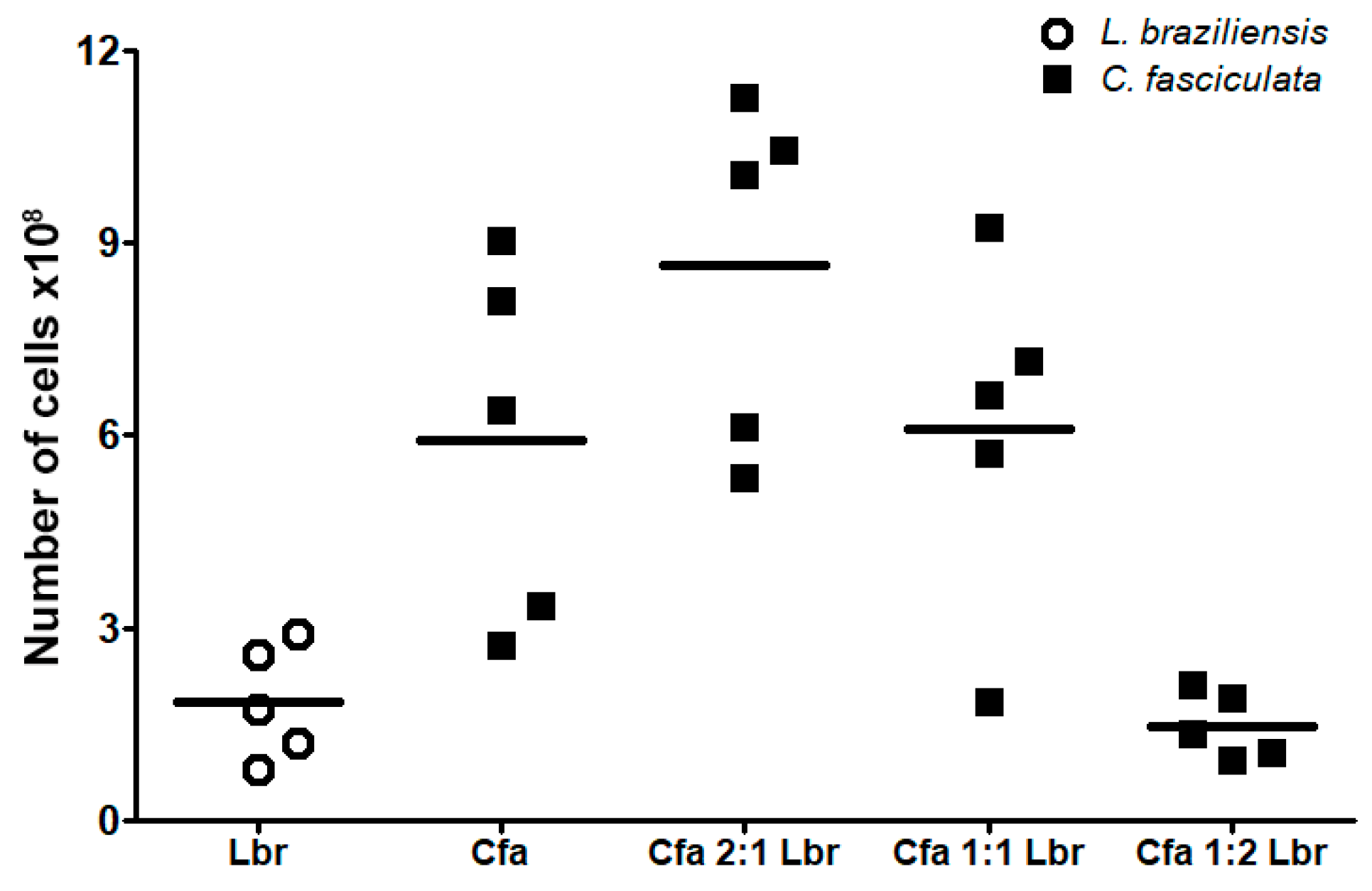

3.2. Cell Growth Evaluation in Leishmania-Crithidia Co-Cultures

3.3. Susceptibility to Amphotericin B

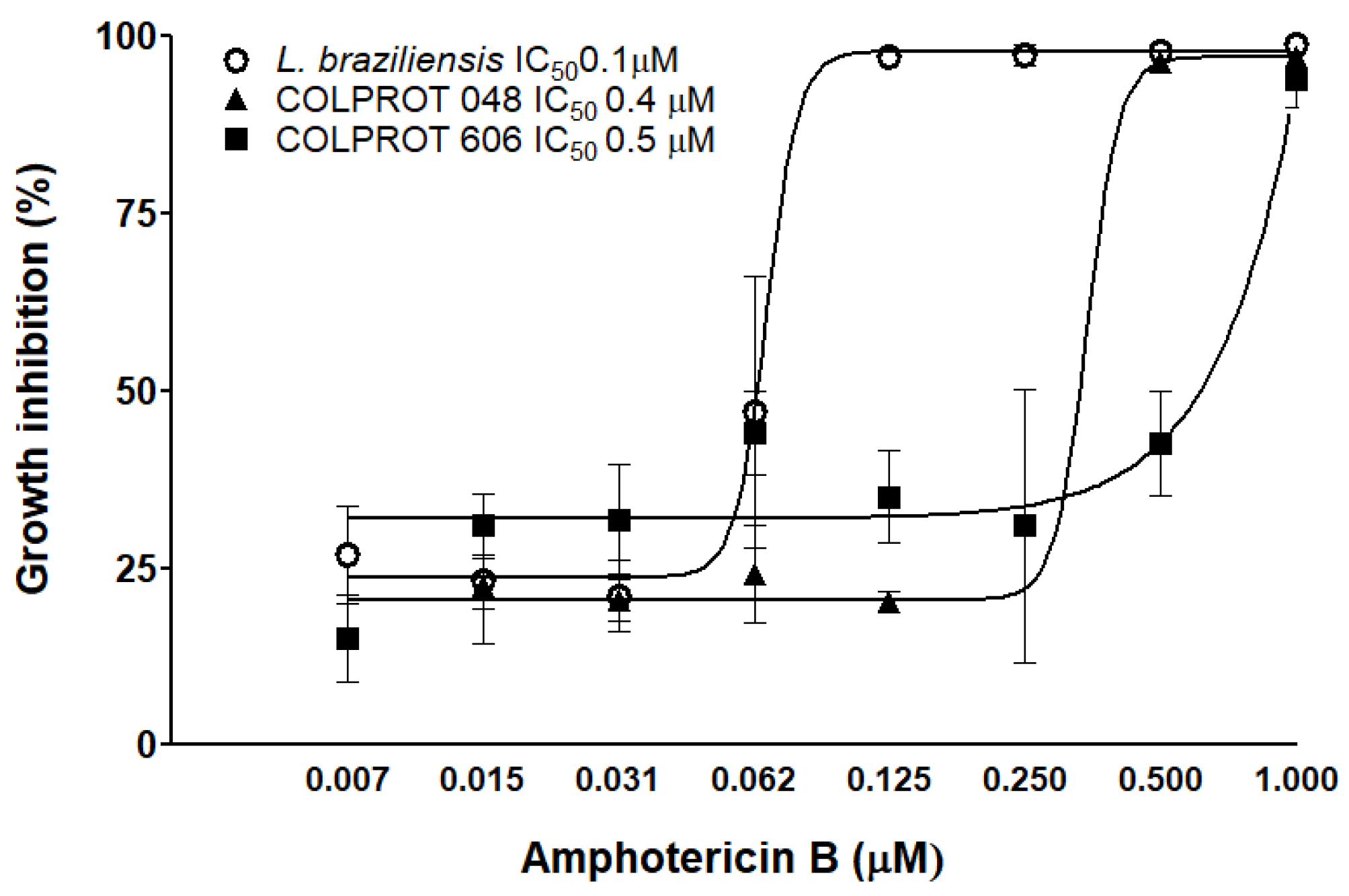

3.4. In Vitro Coinfection of C. fasciculata and L. braziliensis

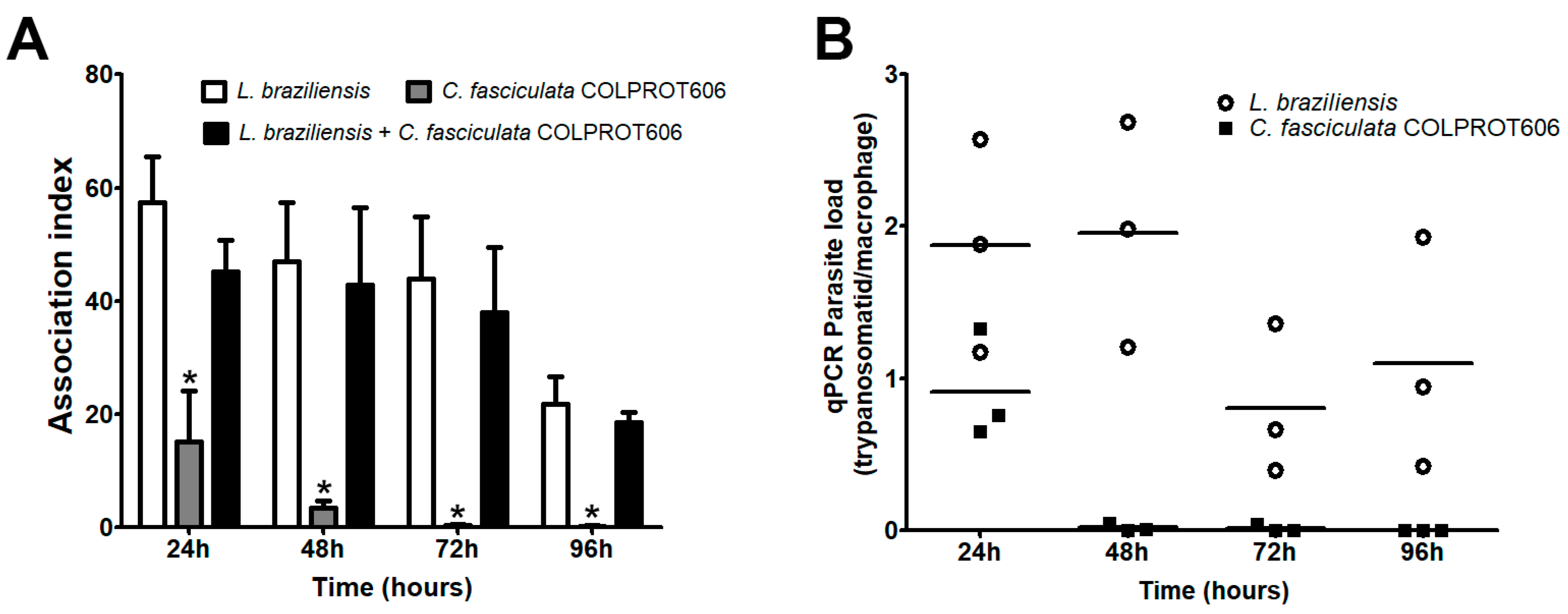

3.5. In Vivo Experimental Infections

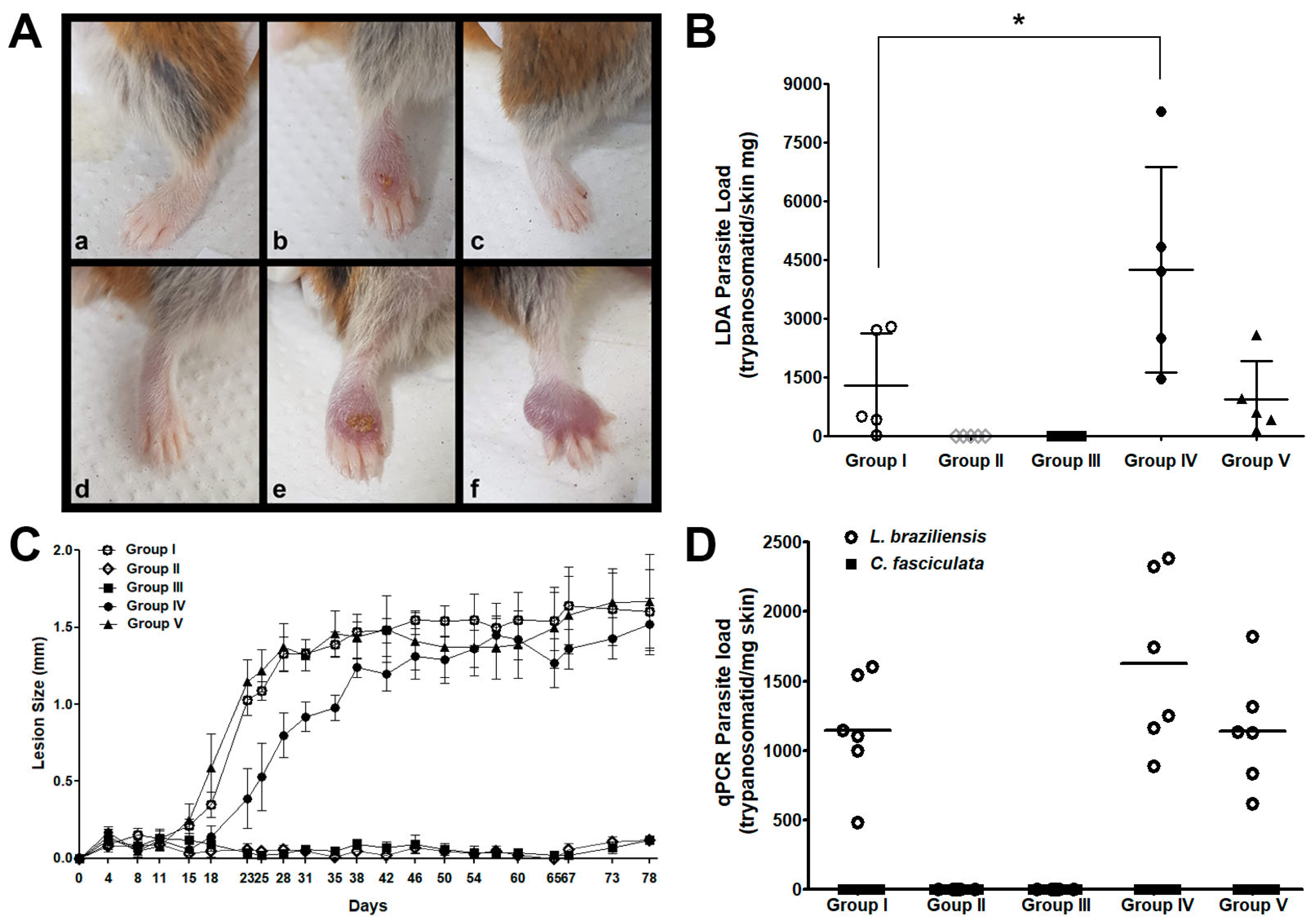

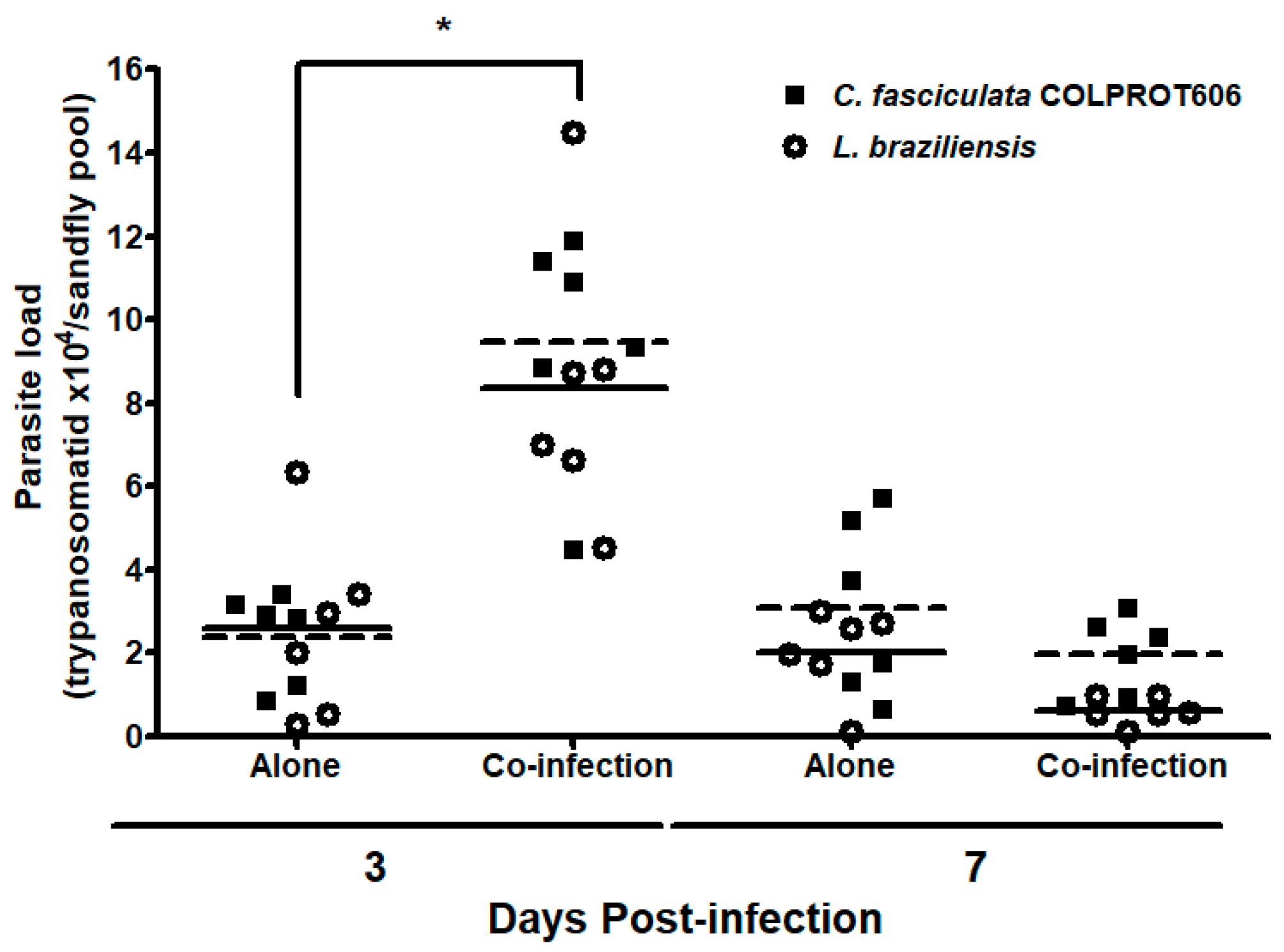

3.6. Co-Infection of Sandflies with L. braziliensis and C. fasciculata COLPROT606

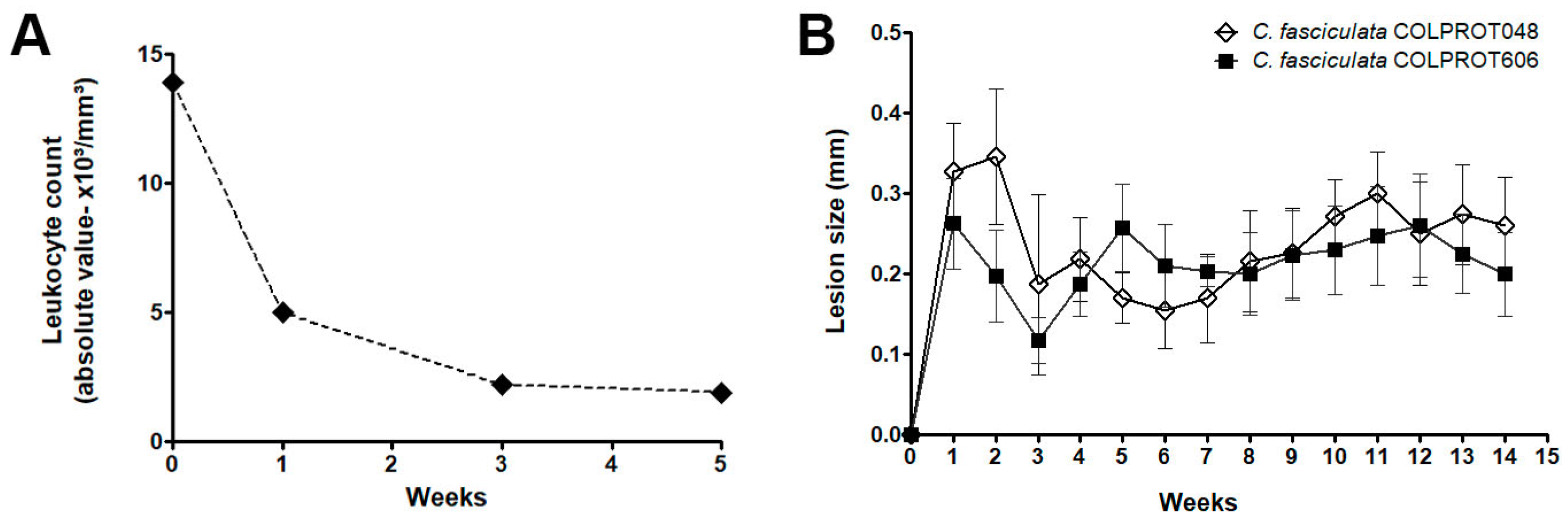

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamida, A.; Ilyas, D.; Zahra, M.; Shehnaz, G. In Leishmaniasis: A Neglected Tropical Disease. In Global Immunological & Infectious Diseases Review; APA, 2019; Volume IV, Chapter 1, pp. 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Volpedo, G.; Zhang, W.W.; Lypaczewski, P.; Ismail, N.; Oliveira, F.; et al. Centrin-deficient Leishmania mexicana confers protection against Old World visceral leishmaniasis. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7(1), 157. [CrossRef]

- Maslov, D.A.; Votýpka, J.; Yurchenko, V.; Lukeš, J. Diversity and phylogeny of insect trypanosomatids: all that is hidden shall be revealed. Trends Parasitol. 2013, 29, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Toledo, P.D. Comportamiento in vitro de um Kinetoplastido Trypanosomatidae Aislado de uma Lesion Cutanea. Licenciate Thesis, Universidad Nacional Siglo XX, Llallagua, Bolivia, 2007.

- Maruyama, S.R.; Santana, A.K.M.; Takamiya, N.T.; Takahashi, T.Y.; Rogerio, L.A.; Oliveira, C.A.B.; et al. Non-Leishmania parasite in fatal visceral leishmaniasis-like disease, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2088–2092. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, N.; Motazedian, M.H.; Naderi, S.; Ebrahimi, S. Isolation of Crithidia spp. from lesions of immunocompetent patients with suspected cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24, 116–126. [CrossRef]

- Boucinha, C.; Andrade-Neto, V.V.; Ennes-Vidal, V.; Branquinha, M.H.; Santos, A.L.S.; Torres-Santos, E.C. A stroll through the history of monoxenous trypanosomatids infection in vertebrate hosts. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 804707. [CrossRef]

- Fakhar, M.; Derakhshani-nia, M.; Gohardehi, S.; Karamian, M.; Hezarjaribi, H.Z.; Mohebali, M.; et al. Domestic dogs carriers of Leishmania infantum, Leishmania tropica, and Crithidia fasciculata as potential reservoirs for human visceral leishmaniasis in northeastern Iran. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 2329–2336. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.S.; Santos, G.Q.; Silva, M.V.d.; Barros, J.H.S.; Bernardo, A.R.; Diniz, R.L.; et al. Chagas immunochromatographic rapid test in the serological diagnosis of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in wild and domestic canids. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 835383. [CrossRef]

- Rogerio, L.A.; Takahashi, T.Y.; Cardoso, L.; Takamiya, N.T.; de Melo, E.V.; Ribeiro de Jesus, A.; et al. Co-infection of Leishmania infantum and a Crithidia-related species in a case of refractory relapsed visceral leishmaniasis with non-ulcerated cutaneous manifestation in Brazil. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 133, 85–88. [CrossRef]

- Takamiya, N.T.; Rogerio, L.A.; Torres, C.; Leonel, J.A.F.; Vioti, G.; Oliveira, T.M.F.S.; et al. Parasite detection in visceral leishmaniasis samples by dye-based qPCR using new gene targets of Leishmania infantum and Crithidia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8(8), 405. [CrossRef]

- Fadhil, S.A.; Ali, M.J. Molecular identification of Crithidia sp. from naturally infected dogs. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 38(4), 831–837. [CrossRef]

- Khademi, A.; Mohammadi, Z.; Tohidi, F. Investigating Crithidia spp. in ulcer smear of patients suspected of leishmaniasis in Aq-Qala, Golestan province, Northern Iran, 2019–2020. Jorjani Biomed. J. 2024, 12(3), 15–17. [CrossRef]

- Boucinha, C.; Caetano, A.R.; Santos, H.L.; Helaers, R.; Vikkula, M.; Branquinha, M.H.; et al. Analysing ambiguities in trypanosomatids taxonomy by barcoding. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e200504. [CrossRef]

- Kraeva, N.; Butenko, A.; Hlaváčová, J.; Kostygov, A.; Myškova, J.; Grybchuk, D.; et al. Leptomonas seymouri: adaptations to the dixenous life cycle analyzed by genome sequencing, transcriptome profiling and co-infection with Leishmania donovani. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005127. [CrossRef]

- Sukla, S.; Nath, H.; Kamran, M.; Ejazi, S.A.; Ali, N.; Das, P.; et al. Detection of Leptomonas seymouri in an RNA-like virus in serum samples of visceral leishmaniasis patients and its possible role in disease pathogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14436. [CrossRef]

- Ennes-Vidal, V.; Vitório, B.S.; Menna-Barreto, R.F.S.; Pitaluga, A.N.; Gonçalves-da-Silva, S.A.; Branquinha, M.H.; et al. Calpains of Leishmania braziliensis: genome analysis, differential expression, and functional analysis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2019, 114, e190147. [CrossRef]

- Bombaça, A.C.S.; Gandara, A.C.P.; Ennes-Vidal, V.; Bottino-Rojas, V.; Dias, F.A.; Farnesi, L.C.; et al. Aedes aegypti infection with trypanosomatid Strigomonas culicis alters midgut redox metabolism and reduces mosquito reproductive fitness. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 732925. [CrossRef]

- Santa-Rita, R.M.; Henriques-Pons, A.; Barbosa, H.S.; De Castro, S.L. Effect of the lysophospholipid analogues edelfosine, ilmofosine and miltefosine against Leishmania amazonensis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 704–710. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Neto, V.V.; Cunha-Júnior, E.F.; Canto-Cavalheiro, M.M.; Atella, G.C.; Fernandes, T.A.; Costa, P.R.; et al. Antileishmanial activity of Ezetimibe: inhibition of sterol biosynthesis, in vitro synergy with azoles, and efficacy in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6844–6852. [CrossRef]

- Inacio, J.D.F.; Gervazoni, L.; Canto-Cavalheiro, M.M.; Almeida-Amaral, E.E. The effect of (-)-epigallocatechin 3-O in vitro and in vivo in Leishmania braziliensis: involvement of reactive oxygen species as a mechanism of action. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8(8), e3093. [CrossRef]

- Meireles, A.C.A.; Amoretty, P.R.; Souza, N.A.; Kyriacou, C.P.; Peixoto, A.A. Rhythmic expression of the cycle gene in a hematophagous insect vector. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006, 7, 38. [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Silva, A.; Valverde, J.G.; Ribeiro-Romão, R.P.; Placido-Pereira, R.M.; Da-Cruz, A.M. Golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) as an experimental model for Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis infection. Parasitology 2013, 140(6), 771–779. [CrossRef]

- Volf, P.; Myskova, J. Sand flies and Leishmania: specific versus permissive vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2007, 23, 91–92. [CrossRef]

- de Melo, L.V.; Vasconcelos dos Santos, T.; Ramos, P.K.; Lima, L.V.; Campos, M.B.; Silveira, F.T. Antigenic reactivity of Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni axenic amastigote proved to be a suitable alternative for optimizing Montenegro skin test. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 402. [CrossRef]

- Kaewmee, S.; Mano, C.; Phanitchakun, T.; Ampol, R.; Yasanga, T.; Pattanawong, U.; et al. Natural infection with Leishmania (Mundinia) martiniquensis supports Culicoides peregrinus (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) as a potential vector of leishmaniasis and characterization of a Crithidia sp. isolated from the midges. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1235254. [CrossRef]

- Domagalska, M.A.; Dujardin, J. Non-Leishmania parasite in fatal visceral leishmaniasis-like disease, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 388. [CrossRef]

- Barral-Netto, M.; Badaró, R.; Barrai, A.; Carvalho, E.M. Imunologia da Leishmaniose Tegumentar. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 1986, 19, 173–191. [CrossRef]

- Kaye, P.; Scott, P. Leishmaniasis: complexity at the host-pathogen interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 604–615. [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.L.; Freire, M.L.; Troian, I.L.; Morais-Teixeira, E.; Cota, G. Local amphotericin B therapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18(4), e0012127. [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, C.J.; Lambros, C.; Goldberg, B.; Hutner, S.H.; De Carvalho, G.D.F. Susceptibility of an insect Leptomonas and Crithidia fasciculata to several established anti-trypanosomatid agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1974, 6, 785. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghafli, H.; Barribeau, S.M. Double trouble: trypanosomatids with two hosts have lower infection prevalence than single host trypanosomatids. Evol. Med. Public Health 2023, 11(1), 202–218. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.S.; Minuzzi-Souza, T.T.; Andrade, A.J.; Coelho, T.O.; Rocha, D.A.; Obara, M.T.; et al. Molecular detection of Trypanosoma sp. and Blastocrithidia sp. (Trypanosomatidae) in phlebotomine sand flies (Psychodidae) in the Federal District of Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2015, 48, 776–779. [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, M.; Motazedian, M.H.; Asgari, Q.; Soltani, Z.; Soltani, A.; Azizi, K. Bionomics of phlebotomine sand flies species (Diptera: Psychodidae) and their natural infection with Leishmania and Crithidia in Fars Province, Southern Iran. J. Parasit. Dis. 2018, 42, 511–518. [CrossRef]

- Tanure, A.; Rêgo, F.D.; Tonelli, G.B.; Campos, A.M.; Shimabukuro, P.H.F.; Gontijo, C.M.F.; et al. Diversity of phlebotomine sand flies and molecular detection of trypanosomatids in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0234445. [CrossRef]

- Songumpai, N.; Promrangsee, C.; Noopetch, P.; Siriyasatien, P.; Preativatanyou, K. First evidence of co-circulation of emerging Leishmania martiniquensis, Leishmania orientalis, and Crithidia sp. in Culicoides biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae), the putative vectors for autochthonous transmission in Southern Thailand. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 379. [CrossRef]

- Ennes-Vidal, V.; Pitaluga, A.N.; Britto, C.F.P.C.; Branquinha, M.H.; dos Santos, A.L.S.; Menna-Barreto, R.F.S.; et al. Expression and cellular localisation of Trypanosoma cruzi calpains. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e200142. [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, S.; Bahrami, F.; Parvizi, P.; Fard-Esfahani, P.; Ajdary, S. An overview of the sand fly salivary proteins in vaccine development against leishmaniases. Iran J. Microbiol. 2022, 14(6), 792–801. [CrossRef]

| Trypanosomatid | 48 hours | 96 hours | ||||

| TMRE+ cells (%) | IVa | TMRE+ cells (%) | IVa | |||

| C. fasciculataCOLPROT048 | 27°C | 91.0±1.1b | 0.00 | 84.1±1.7 | 0.00 | |

| 27°C +CCCP10 µM |

20.1±1.8* | -0.58* | 14.9±1.0* | -0.95* | ||

| 32°C | 82.8±2.0 | 0.07 | 79.6±0.5 | -0.60* | ||

| C. fasciculataCOLPROT606 | 27°C | 87.5±1.7 | 0.00 | 74.4±0.8 | 0.00 | |

| 27°C +CCCP10 µM |

29.9±2.0* | -0.63* | 26.8±1.9* | -0.81* | ||

| 32°C | 66.1±6.6 | -0.62* | 52.1±1.3* | -0.64* | ||

| L. braziliensis | 27°C | 86.0±0.7 | 0.00 | 73.8±2.6 | 0.00 | |

| 27°C +CCCP10 µM |

3.3 ±4.1* | -0.57* | 10.0±2.1* | -0.96* | ||

| 32°C | 51.8±4.1 | -0.30* | 13.2±0.9* | -0.90* | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).