1. Introduction

Leishmania is an important genus of parasitic protozoa due to their medical and veterinary significance. They have made efficient adaptations to survive in a large diversity of hosts or reservoirs. Therefore, they survive in a variety of vertebrates such as dogs (the main reservoir of these parasites, though the causative agent of canine leishmaniasis identified is not restricted to Leishmania infantum), domestic cats, wild animals, and synanthropic animals, while being transiently infectious to humans (

Figure 1) [

1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the ability of

Leishmania to infect multiple hosts has facilitated their spread through phlebotomine sandflies. During their digenetic life cycle, female phlebotomine sandflies of several species of

Phlebotomus and

Lutzomyia act as vectors in the zoonotic transmission of

Leishmania between mammals and sandflies (

Figure 1) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

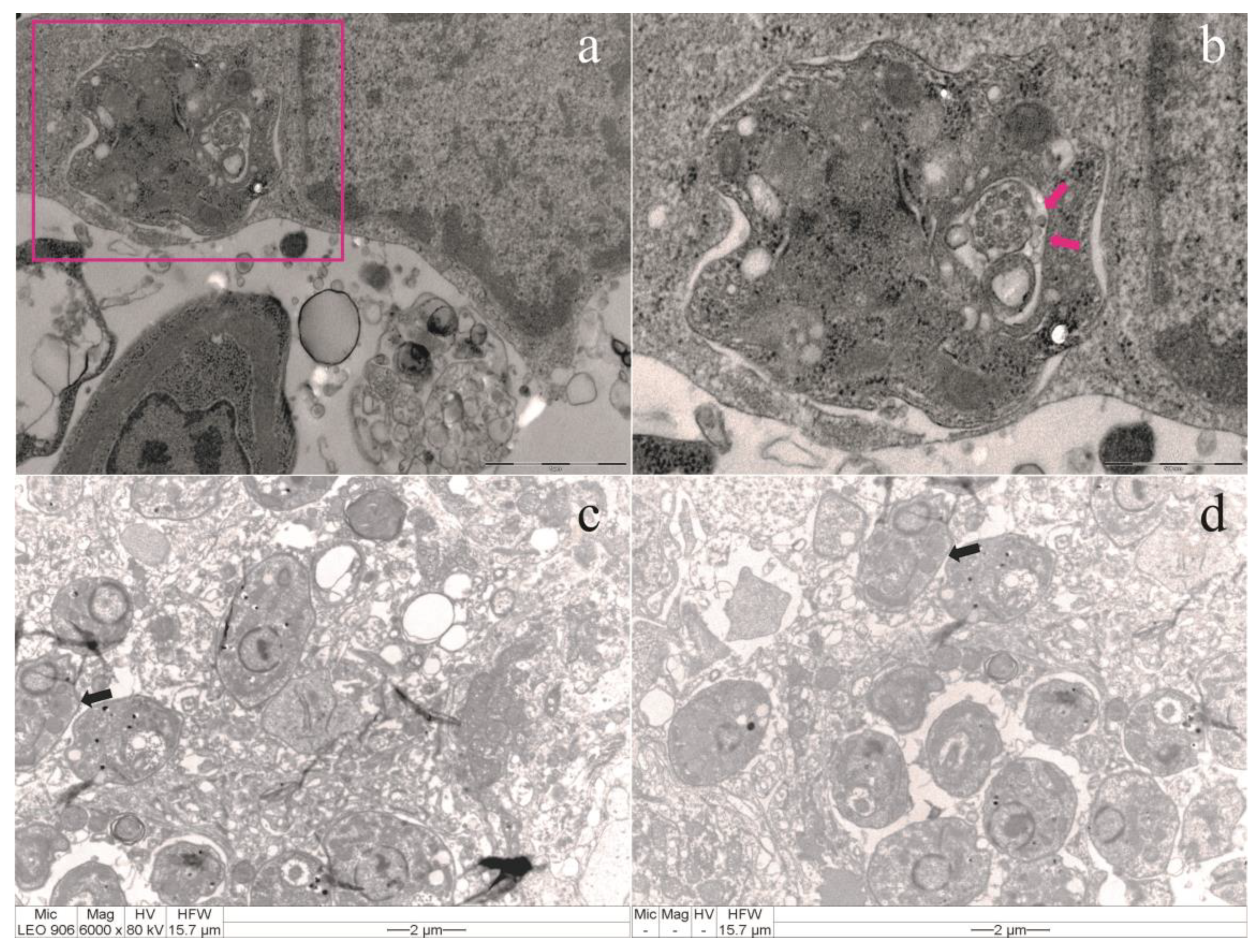

It is, therefore, important to draw the attention of veterinarians to transmission and the risk of transmission as clinical keys to establish the signs and pathological abnormalities of

Leishmania infection, despite the difficulty in determining the incubation period. This is particularly true given that intracellular parasites may appear only after several weeks or months, typically with shorter incubation periods for cutaneous forms (

Figure 2) [

11,

12]. Concurrently, with the spread of leishmaniasis, recent studies reveal that the most popular pet animals worldwide are at risk of acquiring leishmaniasis coinfection with other emerging zoonotic parasites, viruses, and other infectious agents. These findings underscore the need for further studies on extracellular vesicle production and the simultaneous cascade effects of molecular interactions on the host immune system (

Section 1, Supplementary material) [

1,

13,

14,

15]. In this sense, coinfected companion animals (e.g., dogs and cats) are important elements of the

Leishmania life cycle, and at the same time, they contribute to the transmission of other disease agents of medical and veterinary importance. These infections can cause sensible health deterioration (e.g., weight loss, anemia, and low immune resistance), leading to secondary infections, increased morbidity, and even the death of infected animals [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. What hypotheses should still be considered in the

Leishmania zoonotic cycle? a. Hosts have different biochemical, immunological, behavioral, and other defense mechanisms to ward off parasites, and many features of parasites are adaptations to overcoming these defenses. b. The different levels of

Leishmania virulence depend on the evolution of both the host and the parasite. c. The susceptibility of potential new hosts and vectors can vary under interconnected factors. d. Even more impressive than the life cycles of

Leishmania are their many defenses against the antibodies of vertebrate hosts. These antibodies are proteins that recognize and bind to foreign proteins and other molecules in polydisperse complex biological samples (e.g., extracellular vesicles surrounded by a lipid layer of the parasite membrane) [

1,

14,

15,

17,

19]. The clinical signs of leishmaniasis are directly related to the immune response of the infected dog; however, it is estimated that more than half of infected dogs do not manifest clinical signs of the disease [

20]. Despite the development of some veterinary vaccines, the lack of effective vaccines and drug treatments for humans has led to the increase of this major health problem worldwide [

1,

2,

12]. These parasites exhibit a high level of genetic variability

in vivo and a propensity for rapid evolution

in vitro. Infection is established through heterogeneous extracellular vesicles released by the parasite, which contain many molecules that modulate the host immune responses. These molecules were generically referred to as

Leishmania extracellular vesicles or

LEVs by Gabriel et al. (2021) [

1,

21].

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the isolation and biological and functional characterization of the lipoproteic vesicles released by

Leishmania (

LEVs). This is due to their apparent potential for the development of effective diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, including the prediction of the outcome of the interaction between cells [

1,

21,

22]. Technology advances have led to the production of new tools that make progress in the study of extracellular vesicle biology and its applications. However, mechanisms of the selective packaging of

LEVs are still poorly understood. Moreover, there is no consensus on the differential isolation and characterization of these extra-cellular vesicles or the ultrasensitive detection of specific sub-types, biomarkers, and biogenesis [

1,

21]. Recent studies indicated that the lipid composition of extracellular vesicles influences their biogenesis, cargo sorting, interactions with target cells, and functional effects on recipient cells [

22,

23,

24,

25]. In this way, there is an emerging focus on lipids in

LEVs. Nevertheless, still there are gaps in the research for understanding the mechanisms and biological aspects involved in

Leishmania–host interactions [

1,

21,

22]. We note that lipid bodies are organelles distributed in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, largely associated with lipid storage in the past. However, they are now recognized as dynamic and functionally active organelles, involving in a variety of functions such as lipid metabolism, cell signaling, and inflammation. These lipid bodies have been identified inside dermal macrophages and are actively formed within heart macrophages following infection of another protozoan parasite,

Trypanosoma cruzi [

22,

23]. The study emphasizes the importance of diagnosing natural canine leishmaniasis. In addition, it compares the findings with

in vitro results related to the endocytosis and exocytosis processes that occur during the disease’s pathogenesis. This comparison complements the authors’ previous research on lipids in extracellular vesicles (

LEVs). The ultimate goal is to contribute to future nanotechnological research within the One Health framework. This will further contribute to the development of new management approaches that improve prophylactic measures, ensure effective diagnosis and prognosis for both acute and chronic leishmaniases, and advance treatment options.

In essence, this study aims to bridge the gap between observations of natural infection and laboratory findings to enhance the overall understanding and management of leishmaniasis.

4. Discussion

The clinical signs of leishmaniasis in dogs are directly related to their immune response and follow four stages based on serological status, clinical signals, laboratory findings, and type of therapy and prognosis. These stages result from the interactions between lipids in extracellular vesicles (

LEVs) and host cells, which are not well understood. In susceptible animals, parasites can spread from the skin to the local lymph node, spleen, and bone marrow within hours, providing a valuable area for molecular studies of host–parasite interactions [

12,

31]. According to the present molecular results,

L. infantum infection is not associated with the gender or age of the dogs nor were coinfections considered in the positive cases. No difference was found between the types of biological samples studied (blood and conjunctival swab) in the detection of

Leishmania sp. However, for greater reliability of the results, PCR is indicated for various types of samples, given the importance of

Leishmania infection, mainly due to its high zoonotic potential.

Detection of infection by amplifying

kDNA segments and

SSUr-rDNA showed similar sensitivity, indicating that both can be used for the diagnosis of canine leishmaniasis [

29,

30]. The sequencing of 18S rRNA segments allowed the identification of

L. infantum in all cases, and four animals were infected by strains with genetic variability, including three heterozygous samples and one with a pyrimidine (C→T) transition-type mutation. According to a clinical study, in resistant dogs, the parasite remains restricted to the skin and draining lymph nodes [

31]. Based on these considerations, the first-choice samples for PCR should be bone marrow, lymph node, spleen, skin, and conjunctival swabs. Other samples, such as blood, buffy coat, and urine, are considered less sensitive [

12]. New nanotechnology-based approaches to extracellular vesicles have gained significant interest in the scientific community for their potential in therapeutic and diagnostic innovation in parasitology [

1]. Despite advances in the

Leishmania research, the selective mechanisms of lipids in extracellular vesicles (

LEVs) remain poorly understood. There is no consensus on their differential characterization, ultrasensitive detection, specific subtypes, biomarkers, or biogenesis. Understanding the molecular mechanisms and strategies parasites use (e.g., lipids and proteins) to ensure survival could help develop novel antiparasitic drug targets, therapies, and early diagnostic methods [

1,

32]. Actually, the diagnostic methods for canine leishmaniasis include parasitological (cytology or histology, immunohistochemistry, and culture), molecular (conventional, nested, and real-time PCR, which is considered the most sensitive technique), and serological (quantitative IFAT and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and quantitative rapid tests) methods [

12]. However, individual case reports can add new parameters for the accuracy of diagnosis, confirming coinfection and the range of differential diagnoses—or if the animal remains healthy or develops a mild, self-limiting illness [

31]. These hardy dogs mount a weak antibody response against canine leishmaniasis, but a strong and effective Th1 response. They may have low antibody titers but produce IFN-γ in response to parasitic antigens, generate type I granulomas, mount a strong late-type hypersensitivity response, and eventually destroy the parasites [

31]. Resistance to

Leishmania has a strong genetic component. For example, Ibizan Hounds, an ancient rabbit-hunting breed, appear resistant to

Leishmania. This resistance may be associated with specific major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II haplotypes and certain Slc11a1 (Nramp) alleles. Therefore, Ibizan Hounds could serve as a good canine model for studying protective anti-

Leishmania immune responses [

33].

Recent research shows significant differences in the cytokine serum profile and genetic variants related to immune response among canine breeds. Notable genes with fixed polymorphisms include

IFNG and

IL6R, while other variants with frequencies of 0.7 or higher were found in

ARHGAP18,

DAPK1,

GNAI2,

MITF,

IL12RB1,

LTBP1,

SCL28A3,

SCL35D2,

PTPN22,

CIITA,

THEMIS, and

CD180. Epigenetic regulatory genes, like

HEY2 and

L3MBTL3, also show intronic polymorphisms [

34]. Future studies should further explore why immune response regulation differs in Ibizan Hounds compared to other breeds [

34]. Some dogs develop severe and generalized nodular dermatitis, granulomatous lymphadenitis, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly, exhibiting activation of polyclonal (occasionally monoclonal) B lymphocytes involving all four classes of IgG, as well as hypergammaglobulinemia. They may develop lesions associated with hypersensitivity types II and III [

31]. Excessive immunoglobulin production can lead to immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and antinuclear antibodies [

31]. Chronic immune complex deposition can result in glomerulonephritis, uveitis, and synovitis, leading to renal failure and death [

31]. Elevated anti-histone antibodies are a feature of some dogs with glomerulonephritis associated with leishmaniasis, correlating with the protein/creatinine ratio and increasing the likelihood of glomerulonephritis [

31]. In susceptible animals, parasites can spread from the skin to the local lymph node, spleen, and bone marrow within hours. In resistant dogs, the parasite remains restricted to the skin and draining lymph node, resulting in either a healthy state or a mild, self-limiting disease. Susceptible dogs mount a Th2 response characterized by high antibody levels but poor cell-mediated immunity, attributed to IL-10-producing Treg lymphocytes. The parasite can suppress IL-12 gene transcription, ensuring that the Th2 response predominates. These immune challenges affect the balance between progression to clinical disease and maintaining subclinical disease during chronic infection or progressive disease in susceptible dogs [

31].

Following these considerations, vaccines and immunotherapies targeted at recovering or maintaining T and B cell functions can be important in mending the immune balance of parasite–host interactions required for the pathogenesis of canine leishmaniasis [

35]. In veterinary practice, infected dogs may show signs of disease, but some positive dogs with subclinical infection or those infected but clinically healthy may exhibit clinicopathological abnormalities or no clinical signs of leishmaniasis. Anti-

Leishmania therapeutic protocols can reduce parasite load and infectiousness in treated animals, though their efficacy is only temporary [

3,

12]. Dogs exhibit extraordinary phenotypic diversity due to selective breeding over the past 200 years, leading to significant variation in immune system function between breeds. This diversity is evident in the unique susceptibility of different breeds to immune-mediated and infectious diseases. Understanding the mechanisms of adaptive and innate immunity in dogs is crucial for elucidating the progression of diseases and the immune response. This knowledge is essential for comprehending how the immune system functions during disease progression in individual dogs [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In veterinary immunology, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are receptors that recognize specific molecular structures on pathogens. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL), a key soluble C-type lectin, is present at high levels in serum and binds to various oligosaccharides. Despite weak individual binding, multiple sites confer high functional activity, allowing MBL to strongly bind pathogens like

Leishmania and activate the complement system [

31]. Phagocytic cells have many PRRs that interact with infectious agents. Pathogens can bind to neutrophils in plasma, leading to quick ingestion by phagocytosis. Neutrophils can undergo NETosis, releasing nuclear contents into the extracellular fluid after activation by CXCL8 or lipopolysaccharides [

31]. This forms networks of extracellular fibers called “neutrophil extracellular traps” (NETs) [

29]. NETs are abundant at the sites of acute inflammation. These networks trap and kill several pathogens such as

L. amazonensis [

31]. NETs can be very important in containing microbial invaders by acting as physical barriers, capturing large numbers of parasites and thus preventing their spread [

31]. When promastigote forms of this parasite are injected by sandflies into the skin of a dog, they are quickly phagocytosed by the neutrophils [

31]. When neutrophils go into NETosis, parasites are released and then engulfed by macrophages and dendritic cells, in which organisms differentiate into amastigotes.

Leishmania amastigotes are obligate intracellular parasites that divide within macrophages until the cells rupture, and when released into the body, they are phagocytosed by adjacent cells [

31]. Depending on the degree of host immunity, parasites can be restricted to the skin (skin disease); alternatively, dendritic cells may migrate to the lymph nodes or enter the circulation and lodge in the internal organs, leading to the visceral spread of the disease.

Although the disease is widespread in endemic areas, most dogs are resistant to

Leishmania, and only 10%–15% develop the visceral form of the disease [

31]. Macrophages are the major host cells for

Leishmania, as well as the effector cells that limit or allow the adaptative growth of these parasites within infected macrophage phagolysosomes (intracellular form) [

31]. Their resistance to intracellular destruction is the result of multiple mechanisms, including genetic factors. Comparative studies of 245 macrophage genes demonstrated that 37% were suppressed by

Leishmania infection [

31].

Leishmania lipophosphoglycans (LPGs) delay the maturation of the phagosome, preventing the production of nitric oxide (NO) and inhibiting the response of macrophages to cytokines [

31]. These parasites also reduce the presentation of macrophage antigen by suppressing the expression of class II MHC when the parasites stimulate chronic inflammation. They are thus characterized by granulocytic invasion, followed by macrophages, lymphocytes, and natural killer (NK) cells that collectively form granulomas [

31]. Additionally, one important factor that determines the success or failure of an infection is the availability of iron [

31]. Innate resistance to many intracellular organisms, such as

Leishmania, is controlled, in part, by a gene called

Slc11a1 (short for solute carrier family 11, member 1a; formerly called

Nramp1) [

31].

Leishmania can evade the host’s immune response and ensure their survival and completion of their life cycles. In general, antibody-mediated immune responses protect against extracellular protozoa, while cell-mediated responses control intracellular protozoa [

31]. Parasitic protozoa employ some sophisticated techniques to ensure their survival in the face of an animal’s immune response [

31]. The Th1-mediated responses that result in macrophage activation are important in many diseases caused by protozoa, in which organisms are resistant to intracellular destruction [

31]. One of the most significant routes of destruction in M1 cells is the production of NO [

31]. The nitrogen radicals formed by the interaction of NO with oxidants are lethal to many intracellular protozoa [

31]. However, protozoa, such as

Leishmania and

T. cruzi, are adept at surviving inside macrophages. They can migrate to safe intracellular vacuoles by blocking phagosome maturation and suppressing the production of oxidants or cytokines [

31]. The development of canine immune organs was reviewed, highlighting that hematopoietic and immune cells originate from a common bone marrow stem cell. B cells mature in the fetal liver and bone marrow, acquiring B cell receptor (BCR) and undergoing selection to ensure that only functional BCR-expressing B cells survive. Immature T cells are exported to the thymus for final maturation. While puppies are considered immunocompetent between six and 12 weeks of age, the onset of immunocompetence varies due to the presence of maternal-derived antibodies (MDA) [

40]. Increased lifespan has revealed age-related susceptibility to infectious, inflammatory, autoimmune, and neoplastic diseases. Age-related changes include impaired cell-mediated immune responses, reduced blood lymphocyte proliferation, and decreased cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity [

40]. Additionally, there is a decline in the humoral immune response, likely due to decreased Th cell functionality. Despite this, the ability to mount humoral immune responses persists, as shown by protective vaccine antibody titers and responses to booster vaccinations. The triennial revaccination program provides adequate protection for young and adult dogs but may not protect geriatric dogs.

Older dogs often exhibit impaired immune responses to new antigenic challenges, likely due to a reduced pool of naïve T cells and lower T cell receptor diversity [

40]. The key genetic elements of immune responsiveness are found in the MHC genes, present as the dog leukocyte antigen (DLA) and feline leukocyte antigen (FLA) systems [

36]. This suggests that specific dog breeds have genetically determined immune functions, with recent studies showing breed-specific serological responses to vaccination. This genetic background likely affects immune system maturation. In dogs, C-reactive protein (CRP) is the main acute-phase protein, increasing significantly in infectious diseases, such as leishmaniasis, babesiosis, parvovirus, and colibacillosis [

36]. Acute-phase protein levels also rise moderately in canine inflammatory bowel disease. CRP, haptoglobin, and serum amyloid A (SAA) protein levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum of dogs with corticosteroid-responsive arthritis and meningitis. Pregnant dogs show moderately higher levels of haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin, and fibrinogen [

36]. Some studies have shown that dogs in the asymptomatic and symptomatic groups exhibit heterogeneity in copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and iron (Fe) concentrations compared with the control group, emphasizing the important roles of trace elements (TEs) in leishmaniasis [

40]. This suggests that TEs could be assessed as a prognostic factor in leishmaniasis and/or as an adjuvant for the treatment of leishmaniasis [

41]. Susceptible dogs mount a Th2 response with high antibody levels but poor cell-mediated immunity, attributed to IL-10-producing Treg lymphocytes [

31]. The parasite can suppress IL-12 gene transcription, ensuring Th2 response predominance. This leads to chronic, progressive disease with macrophages accumulating parasites and spreading throughout the body [

31]. Despite their antigenicity, parasitic protozoa survive using multiple evasion mechanisms. Studies focus on blocking these mechanisms and developing vaccines for canine leishmaniasis [

1,

31]. Effective vaccines, such as those using purified

Leishmania glycoproteins (fucose–mannose ligands), prevent disease and serve as immunotherapeutic agents [

31]. An alternative vaccine with

L. infantum promastigote excretory and secretory products and muramyl dipeptide also shows promise [

31]. Experimental vaccines, including attenuated and DNA based, have shown promising results in veterinary medicine [

31]. Additional

Leishmania control mechanisms and tools are needed, including new drugs, vaccines, diagnostics, and vector control agents and strategies [

1,

42].

Considering these important points, for the future of prevention and treatment of leishmaniases, we can include all advances resulting from the

LEVs research worldwide, which represent a variety of advantages over live biotherapeutics (next-generation therapies) [

42]. Over the past years, the isolation and analysis of extracellular vesicles from

Leishmania have been challenging. The protocols are not yet standardized, as referred to in the guidelines for extracellular production of

Leishmania published by Gabriel et al. in 2021 [

1,

42], since many protocols with potential effects on the outcome are used and published. It is important to note that several protocols are labor-intensive, requiring costly equipment, increasing risks for the loss of heterogeneous extracellular vesicles, and not discriminating well between exosomes and contaminating structures such as lager vesicles and protein/lipid aggregates [

43].

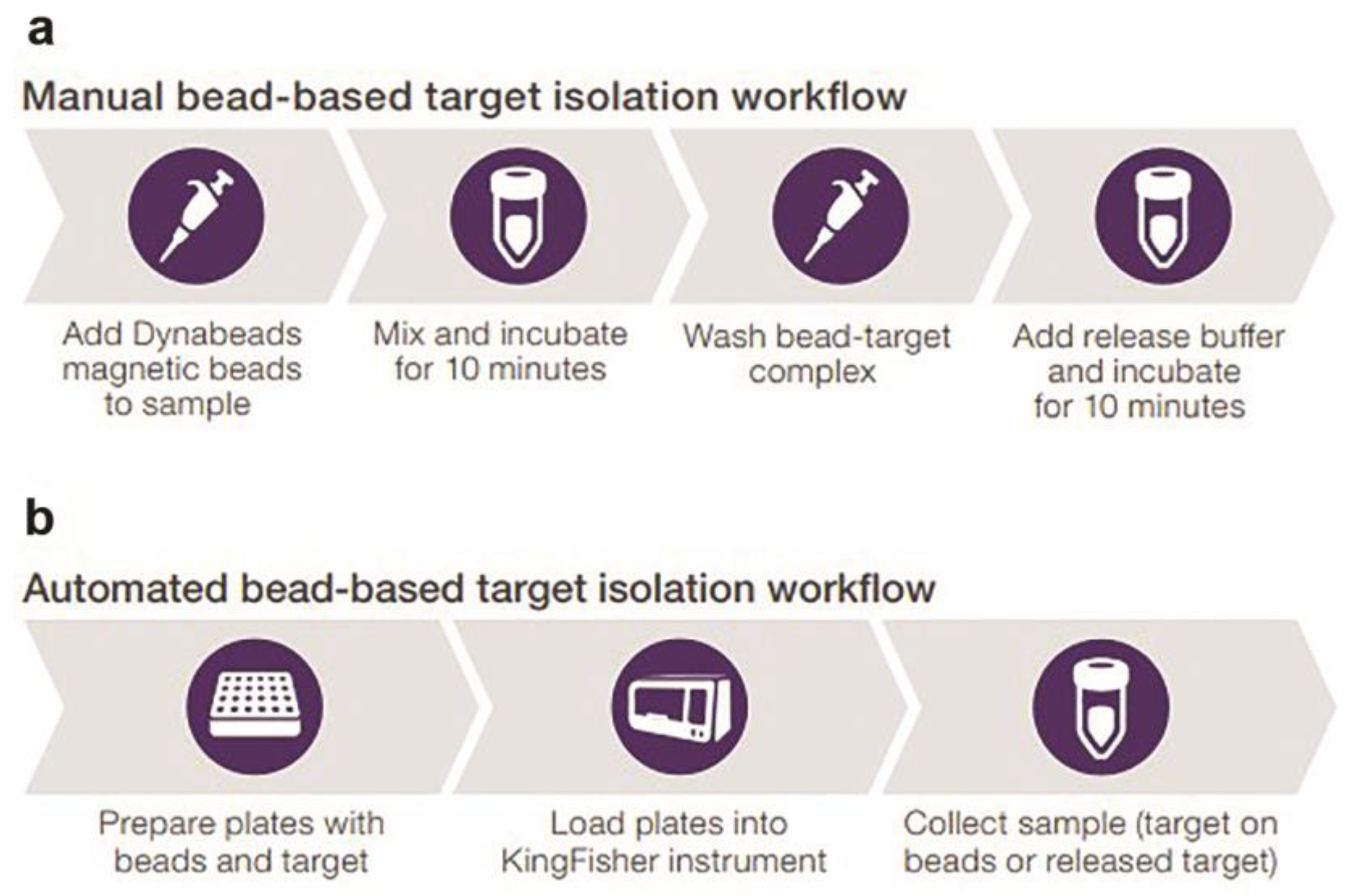

In vitro direct isolation performed with magnetic beads for multiomic analysis (size, concentration, and phenotype by Spectradyne particle analysis, western blot analysis, LC–MS analysis, and flow cytometry) can be applied for

LEVs research, requiring minimal hands-on activities and providing highly pure exosomes with a minimal loss of material. It also enables future automation opportunities in different formats and other simple, rapid, and reliable bead-based extracellular vesicle isolation methods based on the strong anion exchange (SAX) principle (e.g., using both automated KingFisher for rapid and efficient isolation of exosomes compatible with the KingFisher Duo Prime, Flex, and Apex systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and improved manual protocols) (

Figure 7) [

44].

For medical parasitology, multidisciplinary cooperation in multiomic extracellular vesicle research is crucial to understanding

Leishmania–host cell interactions. This includes a broad-scale analysis of extracellular molecules and the development of innovative applications based on

Leishmania virulence factors, such as LPG, surface acid proteinase (GP63), glycoinositolphospholipids (GIPLs), proteophosphoglycan (PPG), A2 protein, kinetoplastid membrane protein-11 (KMP-11), nucleotidases, heat-shock proteins (HSPs), and transmembrane transporters, which support parasite survival and propagation in host cells [

1]. Based on these findings, we propose a rapid bead-based isolation of

LEVs for future multiomic research. This includes techniques for manual and automated bead-based target isolation workflows to achieve quick

LEVs isolation (e.g., within ten minutes using Invitrogen™ Dynabeads™, Thermo Fisher Scientific), based on our observations and practice [

1,

44].

This study reinforces previous guidelines for

LEVs research

in vitro and

in vivo, aiming to improve prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutics. Our results emphasize the importance of focusing on lipids in

LEVs and understanding their release mechanisms from parasites, and their role in sensing the lysosome-specific environment (pH and host temperature).

LEVs have a lipid bilayer membrane that protects encapsulated materials (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and metabolites) from the extracellular environment. Exploring the mechanisms and functions of

LEVs in parasitic production and signaling can help activate or deactivate barriers to prevent host infection and understand how

LEVs interfere with disease progression [

1]. Lipids Lipids are crucial components of extracellular vesicles, serving as energy sources, structural elements, and signaling mediators in Apicomplexa parasites. However, our knowledge about the lipid composition and the function of lipids in mechanisms involved in vesicular trafficking during leishmaniasis is limited [

45,

46]. Thus, analyzing the reproducible results for lipid bodies of

Leishmania labeled with BODIPY™ 493/503 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) has shown that the crucial 72-hour period is a limit to the decrease of lipids released by parasites of genus

Leishmania and subgenus

Leishmania (e.g., species complex:

Leishmania donovani,

Leishmania tropica,

Leishmania major,

Leishmania aethiopica, and

Leishmania mexicana) [

1]. According to Zhang (2021), amastigotes likely acquire most of their lipids from host cells while retaining some capacity for de novo synthesis. In contrast, promastigotes rely on de novo synthesis to produce most of their lipids, including glycerophospholipids, sterols, and sphingolipids [

45]. This balance is just the tip of the iceberg in lipid metabolism, playing a crucial role in

Leishmania infection within the first 72 hours after transmission. It likely alters plasma membrane fluidity and could become a new focus for cell–cell communication research between trypanosomatids and their hosts [

46]. Factors linked to these changes include the length of the fatty acid tail, temperature, cholesterol content of the bilayer, and the degree of saturation of fatty acid tails [

47]. Therefore, new protocols are needed to improve prevention and clinical treatment, considering the relationship of lipids released from parasites [

1].

Various laboratory tests are available to diagnose parasitic infections, including conventional gold standard methods and serological tests. In recent decades, several molecular diagnostic tools have been developed to detect parasites and new strains [

48,

49,

50]. Accurate diagnosis of zoonotic infections involves collaboration between medical scientists, policymakers, and public health officials working to prevent the dissemination of these diseases and establish a worldwide network of surveillance for the coinfection of parasitic infections [

49,

50]. Advanced techniques for studying and diagnosing simultaneous infections indicate that multi-parasitism is more common than single infections [

51,

52]. Evolutionarily, multi-parasite systems are ecologically dynamic, involving key host species and contributing to transmission [

52]. Understanding these complex relationships is a top priority for biomedical sciences in the 21st century [

53]. Clinically, coinfection of zoonotic parasites in companion animals may appear in its classical form, with acute aggressive evaluation or as long-standing infection, which may be asymptomatic or sometimes nonspecific, making clinical diagnosis difficult [

52,

53,

54]. Veterinarians and clinical researchers should consider the health status and background of the patients (animals or humans) to implement a better parasite management program [

53]. Considering certain factors, such as resource-mediated processes, often influence how, where, and which coinfecting parasites interact. These factors may dictate the need for more intensive monitoring for effective treatment, while others may suggest a less aggressive approach [

53,

55,

56]. Furthermore, innovative strategies applying knowledge about extracellular vesicles and their specific profiles (e.g., proteic and lipidic data basis) from studies of host–parasite mechanisms can be incorporated into immunotherapy. This incorporation can interfere in the dynamics of disease transmission and progression and the development of effective, safe, and available vaccines against leishmaniasis, thus helping protect puppies and dogs of different ages. Four vaccines against canine leishmaniasis are available on the market, Leishmine® and Leish-Tec® in Brazil and CaniLeish® and LetiFend® in Europe (the first vaccine based on purified excreted/secreted antigens of

Leishmania has been licensed in Europe since 2011) [

1,

3,

35,

57]. Current vaccine recommendations require vaccinating seronegative dogs. In regions where the disease is endemic in both dogs and humans, accurately identifying healthy, uninfected animals is challenging due to limitations in diagnostics. Adverse events were mild and localized, suggesting that vaccinating healthy subclinical dogs may justify revising current vaccination and immunotherapy guidelines for infected but healthy animals [

35]. Despite existing studies on licensed vaccines for canine leishmaniasis, they are still considered insufficient due to lack of standardization, methodological deficiencies, and differences in study populations.

Further research is needed in xenodiagnostic studies to assess the infectivity of

Leishmania and the potential interference of vaccination in diagnosing its infection. Additionally, long-term pharmacological surveillance should be maintained post-licensing to provide reliable information to relevant organizations and the public [

57]. As indicated in our previous publication on Guidelines for Exosomal Research, further advances in techniques and protocols are expected to improve the accuracy of isolating and characterizing

LEVs and their activity on host immune responses. This includes understanding their lipid bilayer membrane, which protects encapsulated materials like lipids from the extracellular environment. Knowledge about the lipid composition and function of

LEVs is limited, and we propose its significant molecular role during the pathogenesis of leishmaniasis. Changes in lipid profile and metabolism in both parasite and host during disease development depend on lipid bodies. Further research is needed to fully understand the

in vivo relationship between host lipid metabolism and

LEVs, immune responses, disease prognosis, and the necessary advances in the prevention and treatment of leishmaniasis [

58].