1. Introduction: The Imperative for a Paradigm Shift in Fungal Disease Management

1.1. The Twilight of the Chemical Fungicide Era

The current agricultural model, highly dependent on synthetic fungicides, faces unsustainable challenges that threaten global food security. The intensive application of these compounds has precipitated a multifaceted crisis. Firstly, the selection pressure exerted by broad-spectrum fungicides, such as azoles, has accelerated the evolution of resistant pathogen populations, rendering frontline treatments ineffective [

1]. This phenomenon is not a future threat but a current reality that leaves farmers on a “fungicide treadmill,” where the emergence of resistance to one chemical forces the adoption of another, often more expensive and with an equally limited useful lifespan [

2,

3,

4]. The history of crop protection is marked by the sequential emergence of variant genotypes with reduced sensitivity to the most potent single-site fungicide classes, including methyl benzimidazole carbamates (MBCs), demethylation inhibitors (DMIs), quinone outside inhibitors (QoIs), and succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHIs) [

5]. This evolutionary arms race is a serious problem; for example, resistance to benzimidazoles, phenylamides, and sterol biosynthesis inhibitors is a growing issue in Brazilian agriculture, affecting numerous fruit pathogens [

6].

Beyond resistance, there is growing concern about the impact on the environment and human health. The overuse of agrochemicals leads to soil and water contamination, with detrimental effects on non-target organisms [

7]. An alarming example of unintended consequences is the documented connection between the agricultural use of azoles and the emergence of drug-resistant human pathogens, such as

Aspergillus fumigatus, which underscores a serious threat under the “One Health” concept [

8]. The non-target effects of fungicides are not merely collateral damage; they are a direct cause of increased ecosystem fragility. Repeated applications of broad-spectrum fungicides can create a “microbial desert,” eliminating not only the pathogen but also the beneficial microorganisms that contribute to plant health and natural disease suppression. This systematic destruction of the immunity conferred by the plant’s microbiome creates a cycle of dependency: the more you spray, the more necessary it becomes to spray, as the natural biological control mechanisms have been eradicated [

9]. Recent research has shown that intensive fungicide use can decrease the activity of beneficial soil microbes, leading to a more disease-prone microbial environment. In fact, soils from locations with a history of less intensive fungicide use have been observed to show greater disease suppression, suggesting that intensive fungicide use can suppress the natural microbial antagonism of pathogen activity [

2].

1.2. The Promise and Pitfalls of First-Generation Biologicals

In response to the shortcomings of chemical products, biological alternatives have emerged, such as microbial biofungicides and botanical extracts [

10]. These biological control agents (BCAs) offer a more favorable ecological profile, often with a short half-life in the environment and lower toxicity to non-target organisms. However, their widespread adoption has been hindered by significant limitations. First-generation biologicals often exhibit inconsistent efficacy in the field, as their performance is highly dependent on environmental conditions like temperature and humidity, making them less reliable than their synthetic counterparts [

11]. Furthermore, issues such as a shorter shelf life, high production costs, and difficulties in scaling up the manufacturing of active compounds have limited their market competitiveness. The transition from the lab to the field is a notorious challenge; many BCAs that show great success under controlled conditions fail to replicate those results outdoors [

12]. Formulation is another major hurdle, as these living organisms require special storage and formulation techniques to maintain their viability and efficacy. The path from academic research to a robust and reliable commercial product, such as the case of Fungifree AB®, is a considerable challenge that few manage to overcome, often requiring more than a decade of research and development, from basic science to product registration and the creation of a spin-off company [

13].

1.3. Thesis: The Dawn of a New Technological Trifecta

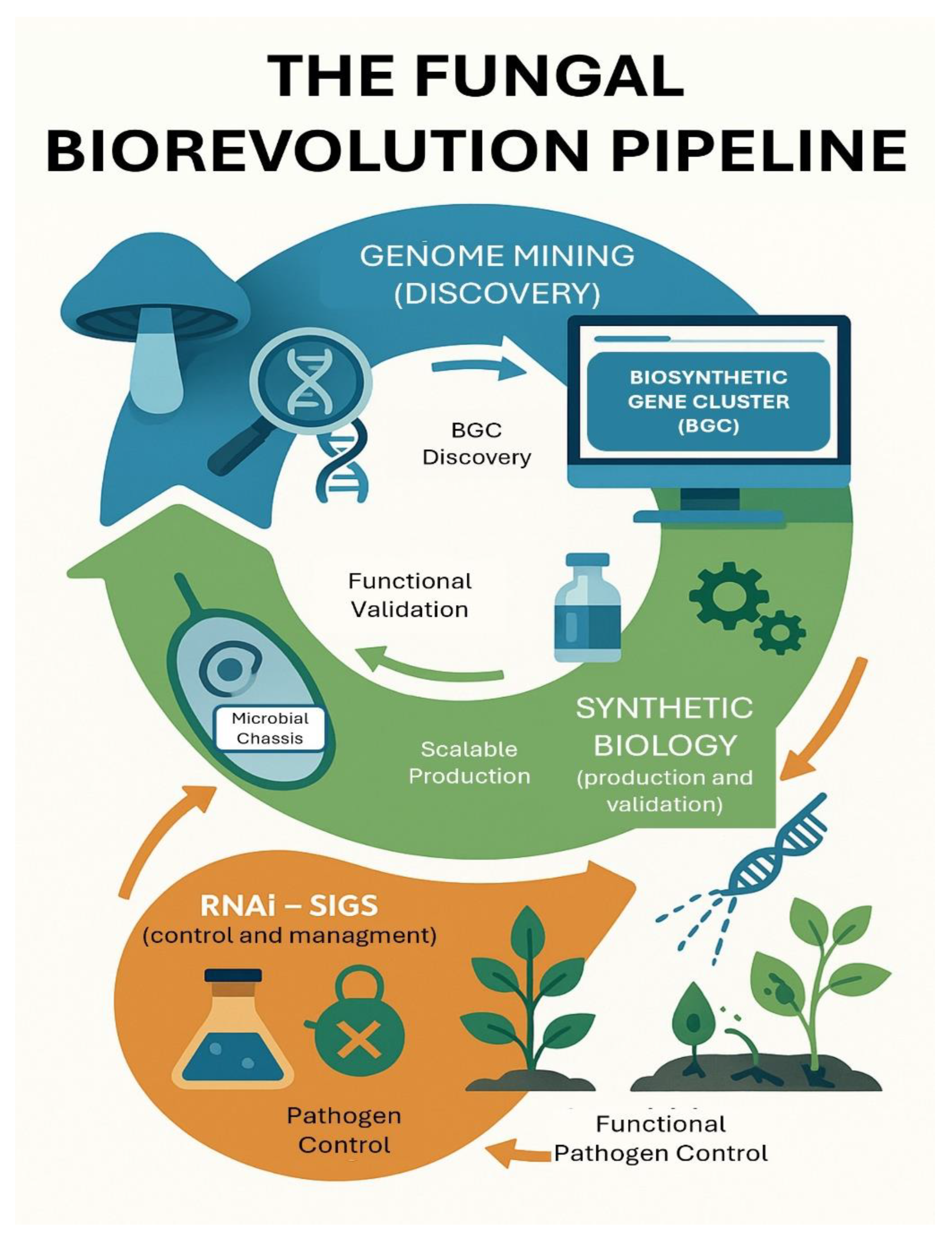

To achieve a true paradigm shift, it is necessary to go beyond simply replacing one product with another and adopt an integrated, technology-driven approach. This article posits that the convergence of three technological fields—genome mining, synthetic biology, and RNA interference (RNAi)—offers a synergistic and multifaceted solution. This trifecta represents a complete pipeline (

Figure 1):

- Genome Mining: For the rational and targeted discovery of new antifungal natural products.

- Synthetic Biology: For the reliable, scalable, and cost-effective production of these discovered products.

- RNA Interference (RNAi): For hyper-specific, non-chemical control and strategic resistance management.

Figure 1.

The Technological Trifecta for a New Generation of Biofungicides. This diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of the fungal biorevolution and the synergy between three key technologies. Genome mining allows for the rational discovery of new antifungal compounds and their biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from vast fungal diversity. Synthetic biology provides the tools for reliable, scalable, and cost-effective production of these discovered compounds by engineering microbial “chassis”. RNA interference (RNAi), specifically through Spray-Induced Gene Silencing (SIGS), offers hyper-specific, non-chemical pathogen control and a powerful strategy for resistance management. The integration of these fields creates a robust, adaptable, and synergistic pipeline to overcome the limitations of both conventional fungicides and first-generation biologicals.

Figure 1.

The Technological Trifecta for a New Generation of Biofungicides. This diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of the fungal biorevolution and the synergy between three key technologies. Genome mining allows for the rational discovery of new antifungal compounds and their biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from vast fungal diversity. Synthetic biology provides the tools for reliable, scalable, and cost-effective production of these discovered compounds by engineering microbial “chassis”. RNA interference (RNAi), specifically through Spray-Induced Gene Silencing (SIGS), offers hyper-specific, non-chemical pathogen control and a powerful strategy for resistance management. The integration of these fields creates a robust, adaptable, and synergistic pipeline to overcome the limitations of both conventional fungicides and first-generation biologicals.

The synergy between these three pillars can overcome the limitations of both chemical fungicides and first-generation biologicals. This integrated approach directly addresses the need for sustainable alternatives that minimize environmental and health impacts while providing effective and durable disease control [

9]. A comparative analysis of these technologies is presented in

Table 1.

2. Unlocking Nature’s Blueprint: Fungal Genome Mining for Novel Antifungal Chemotypes

2.1. From Random Screening to Rational Discovery

The “golden age” of antibiotic discovery was based on cultivating microbes and screening their activity, an inherently random process that led to a high rate of rediscovery of known compounds [

25]. This traditional methodology was blind and contingent, lacking a rational experimental design from strain isolation to compound extraction. Genome mining represents a fundamental shift toward a rational, sequence-based approach. By analyzing an organism’s genome, scientists can predict the chemical diversity it

can produce, even if the compounds are not expressed under laboratory conditions. This allows for targeted discovery and computational “de-replication,” dramatically increasing efficiency and the likelihood of finding novel structures. This genome-based approach transforms natural product discovery from a low-productivity process to a revolutionary strategy that can address the need for new pesticides and medicines [

26].

2.2. The Centrality of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

BGCs are the genomic “factories” responsible for the production of secondary metabolites. Typically, they consist of a core gene encoding a synthase enzyme (such as a polyketide synthase, PKS, or a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase, NRPS) along with genes encoding modification enzymes, transporters, and regulators [

27]. The potential of this resource is immense; fungal genomes harbor a vast number of BGCs, and it is estimated that over 80-95% of their chemical potential remains “silent” or cryptic under standard culture conditions, waiting to be discovered [

28]. Bioinformatic tools like antiSMASH, and the development of new pipelines to identify non-canonical BGCs (such as those producing isocyanides), are fundamental to exploring this vast genomic territory [

29]. The scientific community now has access to databases like MIBiG (Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster) and analysis tools like BiG-SCAPE, which allow for large-scale comparison and network analysis of BGCs to prioritize novel candidates [

30,

31].

2.3. Activating the Silent Majority: Strategies to Awaken Cryptic BGCs

To access the chemistry encoded in these silent BGCs, several activation strategies have been developed:

Genetic Manipulation: Overexpression of pathway-specific transcription factors or manipulation of global regulators, such as LaeA, can induce the expression of entire clusters [

16].

Co-culture: Simulating natural microbial interactions by growing two or more species together can trigger the expression of BGCs as a form of chemical defense or communication. The fungus

Epicoccum dendrobii, for example, induces profound metabolic changes in other fungi when co-cultured with them, revealing its hidden chemical potential [

32]. This strategy, sometimes called OSMAC (One Strain, Many Compounds), exploits the idea that secondary metabolites are often produced in response to specific environmental stimuli [

33].

Epigenetic Modification: The use of chemical inhibitors of histone deacetylases or methyltransferases can alter chromatin structure, making previously inaccessible BGCs transcriptionally active. This approach can unlock the production of compounds that would otherwise remain hidden [

16].

2.4. Case Studies in Fungal Bioprospecting

Two examples illustrate the power of this approach:

The Genus Epicoccum: A systematic study of

E. dendrobii began with the sequencing of its genome, which revealed 34 BGCs. Subsequent chemical analysis led to the isolation of 13 compounds, including novel polyketides and diketopiperazines with potent antibacterial and antifungal activity against relevant pathogens like

Botrytis cinerea. This work exemplifies the complete pipeline: from genome to bioactive compound and functional validation [

32].

Lichenized Fungi: These often-overlooked symbioses are a treasure trove of unique chemistry. Genome mining of

Umbilicaria species showed that 25% to 30% of their BGCs are highly divergent from known clusters, suggesting they encode natural products with novel structures and functions [

27]. This demonstrates the value of exploring unique ecological niches for bioprospecting.

Marine Fungi: Fungi derived from marine environments are another promising frontier. They have evolved unique metabolic and defense mechanisms to survive in their extreme environments, making them a prolific source of structurally novel and bioactive compounds. Genome mining of these organisms is uncovering BGCs that produce polyketides, terpenoids, and alkaloids with significant potential for drug development [

33].

The advancement in sequencing has fundamentally shifted the bottleneck in natural product discovery. The challenge is no longer finding new organisms, but functionally characterizing the overwhelming number of predicted BGCs. We are in an era rich in sequence data but poor in functional characterization [

25]. This “characterization bottleneck” creates strong selective pressure for the development of the technologies discussed in the next section [

34]. The sheer number of uncharacterized BGCs makes heterologous expression (a pillar of synthetic biology) not just an option, but a necessity for high-throughput functional screening. It is far more efficient to synthesize and express BGCs in a well-characterized host than to attempt to create mutants in thousands of non-model fungi.

This establishes a direct causal link between the challenges of genome mining and the solutions offered by synthetic biology.

Table 2.

Promising Fungal Taxa for Antifungal Genome Mining.

Table 2.

Promising Fungal Taxa for Antifungal Genome Mining.

| Fungal Group |

Key Genera |

Classes of Secondary Metabolites |

Noteworthy Bioactivity/Novelty |

References |

| Endophytic Fungi |

Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium

|

Polyketides, NRPS, Terpenoids, Alkaloids |

Prolific source of bioactive compounds with diverse applications |

[28] |

| Marine-Derived Fungi |

Aspergillus, Penicillium, Acremonium

|

Polyketides, Alkaloids (often halogenated) |

Unique chemical structures adapted to extreme environments |

[33] |

| Lichenized Fungi |

Umbilicaria |

PKS, NRPS |

Highly divergent BGCs suggesting novel chemical scaffolds |

[27] |

| Known Biocontrol Genera |

Epicoccum, Trichoderma

|

Polyketides, Diketopiperazines (DKPs), Peptides |

Proven antifungal activity against pathogens like B. cinerea

|

[32] |

| Extremophiles |

Various |

Compounds adapted to extreme conditions |

Potential for novel, stable enzymes and molecules |

[14] |

| Associated Bacteria |

Pseudomonas, Streptomyces

|

Lipopeptides, Polyketides, Alkaloids |

Rich source of antifungal compounds discovered through genome mining |

[26] |

3. Engineering the Cellular Factory: Synthetic Biology for Scalable Biofungicide Production

3.1. The Microbial Chassis Concept

Synthetic biology addresses the production challenge through the concept of “chassis” or “cell factories”: well-characterized and industrially robust microorganisms that are engineered to produce molecules of interest [

14]. These chassis are optimized to channel metabolic precursors into the desired biosynthetic pathway, overcoming the low yields often found in native producers [

18]. Two types of chassis are particularly relevant:

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast): It is a powerful eukaryotic host with GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status, a vast toolkit for genetic engineering, and limited native secondary metabolism, which minimizes interference with the engineered production pathways [

20]. Its industrial robustness and the deep knowledge of its biology make it an ideal platform for the heterologous expression of complex pathways [

22].

Filamentous Fungi (Aspergillus, Penicillium): As natural producers of complex secondary metabolites, these fungi possess the necessary cellular machinery, such as enzymes for post-translational modifications, to correctly fold and modify complex fungal products. They are invaluable workhorses for natural product research and production [

16]. Their secretion capacity and ability to grow on low-cost substrates make them highly attractive for biotechnological applications [

35].

3.2. The Synthetic Biologist’s Toolkit for Pathway Engineering

To build and optimize these cell factories, scientists employ a suite of cutting-edge tools:

Heterologous Expression: This is the key process connecting genome mining to production. It involves taking a BGC from a rare, slow-growing, or genetically intractable fungus and expressing it in a high-performance industrial chassis. This unlocks access to the chemistry discovered in the mining phase [

16].

Gene Editing (CRISPR-Cas9): Allows for the precise insertion of entire BGCs, the deletion of native pathways that compete for precursors, and targeted genetic modifications to optimize metabolic flux [

36]. Versatile CRISPR-Cas9 systems have been developed specifically for filamentous fungi, enabling rapid and efficient genetic engineering across a wide range of species.

Modular Cloning and Standardized Parts: Platforms like FungalBraid (FB), compatible with systems like GoldenBraid, allow for the rapid and standardized assembly of genetic circuits from a library of pre-characterized parts (promoters, terminators, resistance markers). This drastically accelerates the design-build-test-learn cycle [

35].

Promoter Engineering: The use of a suite of constitutive, inducible, and synthetic promoters with different strengths allows for fine-tuning gene expression levels within the BGC. This is crucial for maximizing product titer and avoiding the accumulation of toxic intermediates [

37]. Synthetic promoters can be created by incorporating cis-regulatory elements into a minimal promoter, enabling precise and programmable control of gene expression.

3.3. Beyond Imitation: Creating “Better-Than-Nature” Molecules

Synthetic biology is not limited to recreating natural products; it enables the creation of analogs with improved properties. By engineering the core synthase enzymes (PKS, NRPS) to incorporate different building blocks, or by altering modification enzymes, it is possible to generate libraries of new compounds through “combinatorial biosynthesis” [

14]. This approach can yield molecules with higher bioactivity, stability, or specificity. This approach directly addresses the historical obstacles to the commercialization of natural products: low yields from native sources, supply chain instability, and high production costs [

18].

The relationship between synthetic biology and genome mining is not linear (Discover → Produce), but cyclical and mutually reinforcing. Instead of trying to activate a BGC in its native, often difficult-to-manipulate host, researchers can now synthesize the predicted BGC in silico, express it in a clean yeast or Aspergillus chassis, and use metabolomics to identify the new compound produced. This transforms heterologous expression from a “production” technology to a “high-throughput discovery and validation” platform. This cycle (mine genomes for targets → use SynBio to validate targets and identify products → identify promising products → use SynBio to optimize production) dramatically accelerates the entire pipeline from gene to field.

4. Precision Warfare: RNAi-Based Biofungicides for Targeted Pathogen Neutralization

4.1. The Mechanism of RNAi as a Fungicide

RNA interference (RNAi) is a conserved mechanism of post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) in eukaryotes [

15]. The process is triggered by the presence of exogenous double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which is processed by the Dicer enzyme into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) of 21-24 nucleotides. These siRNAs are loaded into the RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC), which uses the siRNA as a guide to find and degrade the complementary target mRNA, effectively silencing gene expression [

19]. This natural defense mechanism can be co-opted to develop highly specific biopesticides [

17].

4.2. SIGS: A Non-Transgenic Route for Crop Protection

It is crucial to distinguish between Host-Induced Gene Silencing (HIGS), which requires the creation of a genetically modified (GM) plant, and Spray-Induced Gene Silencing (SIGS). SIGS is a non-GM approach where dsRNA is applied topically, similar to a conventional pesticide. The advantages of SIGS are significant: it bypasses the regulatory hurdles and public acceptance issues associated with GMOs, and it can be rapidly deployed in response to an outbreak without the need for lengthy breeding programs [

17]. This technology represents an ecological and sustainable alternative to chemical fungicides, with minimal risk to non-target organisms and human health.

4.3. Key Challenges and Emerging Solutions for Field Application

Despite its promise, the practical application of SIGS faces several challenges:

dsRNA Stability: “Naked” dsRNA is rapidly degraded in the environment by UV light and microbial nucleases, providing only a narrow window of protection (a few days).

Delivery and Uptake: To be effective, the dsRNA must penetrate the fungal cell. Several pathogenic fungi, including

Fusarium circinatum, have been shown to be able to take up externally applied dsRNA [

38]. Two routes have been proposed: direct uptake by the fungus (“environmental RNAi”) and uptake by the plant followed by transfer to the pathogen (“cross-kingdom RNAi”).

Innovative Formulations: The use of nanocarriers (such as layered double hydroxides, liposomes, or carbon dots) to protect dsRNA from degradation and enhance its uptake and persistence is a critical area of research that is overcoming the stability bottleneck. These formulations can improve efficacy and prolong the protection window, making SIGS more commercially viable [

21].

Target Gene Selection: Safety and efficacy depend on selecting genes that are essential for the pathogen (e.g., for virulence or development) and have no off-target homology in the host plant or beneficial organisms [

17]. Advances in bioinformatics and functional genomics have greatly improved the ability to identify and validate these target genes with high precision [

39].

4.4. Successful Applications Against Relevant Fungal Pathogens

Several proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated the efficacy of SIGS against fungi of great economic importance, such as

Botrytis cinerea (gray mold) and

Fusarium graminearum (Fusarium head blight), validating the potential of this technology (

Table 3) [

40]. Research has shown that SIGS can significantly reduce pathogen virulence and protect crops in both laboratory and field conditions [

41].

The most profound application of RNAi in agriculture may not be as a standalone fungicide, but as a strategic tool to manage and even reverse resistance to other fungicides. Resistance is a genetic phenomenon, often caused by a specific mutation or the overexpression of a resistance gene. Since RNAi has exquisite sequence specificity, it can be designed to specifically silence the mRNA of the gene conferring resistance. A SIGS product could, for example, target the mutated version of a target gene, eliminating only the resistant members of the pathogen population. Alternatively, it could silence an efflux pump gene, making the pathogen susceptible again to a conventional fungicide. This “resistance-buster” strategy elevates RNAi from a simple “biopesticide” to a cornerstone of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and the sustainable chemistry of the future.

Table 3.

Successful Applications of Spray-Induced Gene Silencing (SIGS) Against Phytopathogenic Fungi.

Table 3.

Successful Applications of Spray-Induced Gene Silencing (SIGS) Against Phytopathogenic Fungi.

| Target Pathogen |

Host Plant |

Target Gene(s) |

dsRNA Delivery Method |

Reported Efficacy |

References |

| Botrytis cinerea |

Various (tomato, strawberry) |

Dicer-like genes (DCL1/2), virulence genes |

Spraying of naked dsRNA, nanocarriers |

Significant reduction of pre- and post-harvest disease |

[40] |

| Fusarium graminearum |

Barley, wheat |

CYP51 genes (A, B, C) |

Spraying of naked dsRNA |

Reduction of disease and mycotoxin accumulation |

[41] |

| Podosphaera xanthii |

Cucumber |

Chitin synthase genes |

Spraying of naked dsRNA |

Inhibition of powdery mildew growth |

[19] |

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum |

Canola |

Photolyase gene |

Spraying of naked dsRNA |

Reduction of disease severity |

[42] |

| Phomopsis obscurans |

Strawberry |

Virulence genes |

Bioautography with dsRNA |

Demonstrated antifungal activity |

[26] |

| Fusarium circinatum |

Pine |

Vesicle trafficking, signal transduction, cell wall biosynthesis genes |

Spraying of naked dsRNA |

Inhibition of pathogen virulence in pine seedlings |

[38] |

5. The Integrated Biofungicide Pipeline: A Synergistic Framework for the Future

5.1. From Silos to Synergy

The greatest potential of these technologies lies not in their isolated use, but in their integration into a unified pipeline. While current research often treats them as separate alternatives, true innovation lies in merging them into a coherent strategy that leverages the strengths of each to compensate for the weaknesses of the others. This holistic approach is essential for developing robust and sustainable solutions that can cope with the complexity of real-world plant diseases.

5.2. A Hypothetical Case Study: Designing a Next-Generation Control Strategy for Botrytis Cinerea

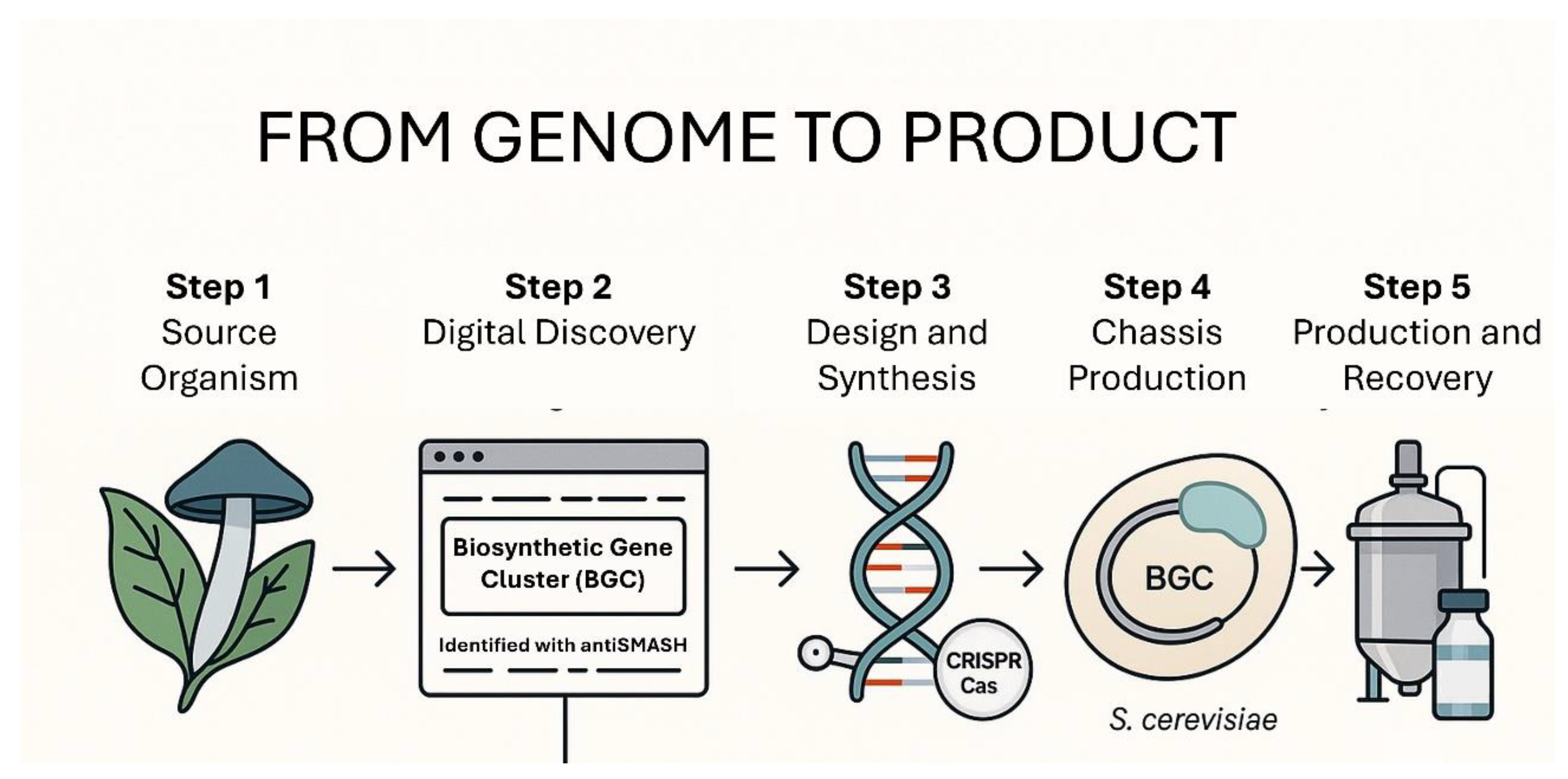

To illustrate this integrated workflow, one can imagine a pipeline to combat gray mold in grapevines (

Figure 2):

Phase 1 (Discovery and Validation): Genome mining is used on a panel of endophytic fungi isolated from grapevines. An AI-assisted BGC analysis identifies a promising and novel NRPS cluster predicted to produce a lipopeptide. The BGC is synthesized and expressed in S. cerevisiae (SynBio for validation). The resulting compound shows potent, targeted activity against the cell membrane integrity of B. cinerea.

Phase 2 (Optimized Production): The validated BGC is transferred to a high-performance

P. chrysogenum chassis. Synthetic promoters and metabolic engineering are used to maximize product titer and formulate a stable, field-ready biofungicide (SynBio for production). This involves optimizing fermentation conditions and developing a formulation that ensures product stability and shelf life [

1].

Phase 3 (Proactive Resistance Management): Simultaneously, a SIGS product is developed. Bioinformatics identifies a key ABC transporter gene known to be overexpressed in multi-fungicide-resistant strains of B. cinerea. A dsRNA molecule targeting this gene is designed and formulated with a biodegradable nanocarrier to enhance stability and uptake (RNAi for resistance management).

Phase 4 (Integrated Deployment): The SynBio-derived lipopeptide and the RNAi-based “resistance buster” are deployed in an integrated program. They can be used in rotation to provide different modes of action, or even co-formulated for a two-pronged attack, drastically reducing the likelihood of resistance evolution. This strategy aligns with the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), which promotes the use of multiple control tactics for sustainable pest management [

43].

Figure 2.

Integrated Workflow for the Development of a Biofungicide against Botrytis cinerea. This diagram shows a hypothetical case study detailing the integrated pipeline to develop a next-generation control strategy against.

Figure 2.

Integrated Workflow for the Development of a Biofungicide against Botrytis cinerea. This diagram shows a hypothetical case study detailing the integrated pipeline to develop a next-generation control strategy against.

This integrated pipeline fundamentally changes the economic and strategic calculus of fungicide development. Instead of a static product destined for obsolescence, it creates a “living” pest management system that can evolve alongside the pathogen. The SynBio chassis is a reusable asset, and the genome mining database is a continuously growing resource. If resistance to the first product emerges, the platform can be rapidly reconfigured: a new BGC is pulled from the database and plugged into the existing production chassis. Concurrently, the RNAi component can be redesigned to target the new resistance gene. This transforms fungicide R&D from a series of discrete, high-risk “bets” into a flexible, adaptable, and sustainable manufacturing system.

6. Ecological Compatibility and Regulatory Horizons

6.1. Designing for the Holobiont

The high specificity of SynBio-derived molecules and RNAi-based fungicides means they can target the pathogen with minimal disruption to the plant’s beneficial microbiome, known as the holobiont [

44]. The holobiont concept considers the plant and its associated microbiota as a single unit of selection, recognizing that these microbes play a crucial role in the plant’s health, growth, and disease resistance [

44]. This “microbiome-friendly” approach contrasts sharply with the broad-spectrum activity of many chemical fungicides, which can inadvertently harm microbes that contribute to natural disease suppression. By preserving these beneficial communities, the new technologies can foster disease-suppressive soils, where indigenous microbial activity keeps pathogens in check [

45].

6.2. Navigating the Regulatory Landscape

Novel technologies face novel regulatory challenges. The framework for SynBio products (regulated as chemicals or as GMO products?) and for topically applied dsRNA is still evolving globally [

23,

24]. Key questions revolve around data requirements for off-target effects, environmental fate, and potential impacts on closely related species. Overcoming these hurdles, along with the challenges of manufacturing scale-up and farmer adoption, will be crucial for their successful commercialization. Farmer adoption will depend not only on efficacy but also on economic viability, ease of use, and the perceived benefits compared to existing practices.

7. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

7.1. Summary of the Integrated Vision

The synergy between genome mining, synthetic biology, and RNAi offers a clear path toward a new era in crop protection. This integrated approach allows for the development of fungicides that are not only potent and specific but also scalable, sustainable, and adaptable to the evolutionary challenges posed by pathogens. By addressing the full cycle from discovery to production and resistance management, this technological trifecta has the potential to revolutionize agriculture and ensure food security in an ecologically responsible manner.

7.2. The Role of AI and Machine Learning

Looking ahead, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning will accelerate every phase of this pipeline: from predicting BGCs and their products from genomic data, to optimizing metabolic pathways in the SynBio chassis [

46], to designing the most effective and specific dsRNA sequences for RNAi while minimizing off-target risks. Machine learning algorithms can analyze vast genomic and metabolomic datasets to identify hidden patterns, prioritize the most promising BGCs, and predict the bioactivity of novel compounds [

47]. In synthetic biology, AI can guide the design of genetic circuits and optimize fermentation conditions for maximum production. For RNAi, AI can help design dsRNA molecules with high silencing efficacy and low off-target potential, accelerating the development of safer biopesticides [

39].

7.3. On-Demand and In Situ Production

Future research could focus on engineering plants or beneficial microbes to produce these biofungicides directly in the field (in situ), creating self-protecting crops and further reducing the need for external applications. This could involve engineering the plant microbiome to include strains that produce antifungal compounds or dsRNA molecules on demand, in response to pathogen detection.

7.4. A Call to Action

Realizing the full potential of this transformative approach requires greater interdisciplinary collaboration among genomicists, synthetic biologists, plant pathologists, ecologists, and regulators. The scientific community must work together to build this pipeline of the future, ensuring that the next generation of agrochemicals effectively protects our crops while safeguarding the health of our planet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C.-R.; methodology, V.C.-R.; formal analysis, V.C.-R.; investigation, V.C.-R.; resources, V.C.-R. and.; data curation, V.C.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, V.C.-R.; writing—review and editing, V.C.-R.; visualization, V.C.-R. and.; supervision, V.C.-R.; project administration, V.C.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All the research data can be found in the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| BCAs |

Biological Control Agents |

| BGC |

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster |

| CRISPR-Cas9 |

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats associated protein 9 |

| DMIs |

Demethylation Inhibitors |

| dsRNA |

double-stranded RNA |

| GRAS |

Generally Recognized as Safe |

| HIGS |

Host-Induced Gene Silencing |

| IPM |

Integrated Pest Management |

| MBCs |

Methyl Benzimidazole Carbamates |

| NRPS |

Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase |

| OSMAC |

One Strain, Many Compounds |

| PKS |

Polyketide Synthase |

| PTGS |

Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing |

| QoIs |

Quinone outside Inhibitors |

| RNAi |

RNA interference |

| SDHIs |

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors |

| SIGS |

Spray-Induced Gene Silencing |

| siRNAs |

small interfering RNAs |

| SynBio |

Synthetic Biology |

References

- Fenta, L.; Mekonnen, H. Microbial Biofungicides as a Substitute for Chemical Fungicides in the Control of Phytopathogens: Current Perspectives and Research Directions. Scientifica 2024, 2024, 5322696. [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.-Y.; Patil, A.T.; Huo, D.; Lei, Q.; Kao-Kniffin, J.; Koch, P. Fungicide use intensity influences the soil microbiome and links to fungal disease suppressiveness in amenity turfgrass. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e01771-24. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, L.; van der Werf, W.; Tittonell, P.A.; Wyckhuys, K.A.G.; Bianchi, F.J.J.A. Neonicotinoids in global agriculture: evidence for a new pesticide treadmill? Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 26. [CrossRef]

- Mikaberidze, A.; Gokhale, C.S.; Bargués-Ribera, M.; Verma, P. The cost of fungicide resistance evolution in multi-field plant epidemics; bioRxiv: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2023.

- Lucas, J.A.; Hawkins, N.J.; Fraaije, B.A. The evolution of fungicide resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 90, 29–92. [CrossRef]

- Deising, H.B.; Reimann, S.; Pascholati, S.F. Mechanisms and significance of fungicide resistance. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2008, 39, 286–295. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Wu, V.C.; Li, W.-H.; Tsai, C.-W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Huang, J.-W. Effects of synthetic and environmentally friendly fungicides on powdery mildew management and the phyllosphere microbiome of cucumber. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282809. [CrossRef]

- Verweij, P.E.; Chowdhary, A.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Meis, J.F. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: Can we retain the clinical use of mold-active antifungal azoles? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 362–368. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M.S.; Yurgel, S.N.; Abbasi, P.A.; Ali, S. The effects of chemical fungicides and salicylic acid on the apple microbiome and fungal disease incidence under changing environmental conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1342407. [CrossRef]

- Cenobio-Galindo, A.d.J.; Hernández-Fuentes, A.D.; González-Lemus, U.; Zaldívar-Ortega, A.K.; González-Montiel, L.; Madariaga-Navarrete, A.; Hernández-Soto, I. Biofungicides Based on Plant Extracts: On the Road to Organic Farming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6879. [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio-Vásquez, M.; Espinoza-Lozano, F.; Espinoza-Lozano, L.; Coronel-León, J. Biological control agents: mechanisms of action, selection, formulation and challenges in agriculture. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1578915. [CrossRef]

- Bonaterra, A.; Badosa, E.; Cabrefiga, J.; Francés, J.; Montesinos, E. Prospects and limitations of microbial pesticides for control of bacterial and fungal pomefruit tree diseases. Trees 2012, 26, 215–226. [CrossRef]

- Galindo, E.; Serrano-Carreón, L.; Gutiérrez, C.R.; Balderas-Ruíz, K.A.; Muñoz-Celaya, A.L.; Mezo-Villalobos, M.; Arroyo-Colín, J. Desarrollo histórico y los retos tecnológicos y legales para comercializar Fungifree AB®, el primer biofungicida 100% mexicano. TIP Rev. Espec. Cienc. Quím.-Biol. 2015, 18, 52–60.

- Medema, M.H.; Fischbach, M.A. Computational and synthetic-biology advances are reshaping the hunt for new drugs from nature. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 629–638.

- Sellamuthu, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Vetukuri, R.R.; Sarath, S.; Roy, A. RNAi-biofungicides: A quantum leap for tree fungal pathogen management. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2025, 45, 1131–1158. [CrossRef]

- Mattern, D.J.; Valiante, V.; Unkles, S.E.; Brakhage, A.A. Synthetic biology of fungal natural products. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 775. [CrossRef]

- Mitter, N.; Worrall, E.A.; Robinson, K.E.; Li, P.; Jain, R.G.; Taochy, C.; Fletcher, S.J.; Carroll, B.J. A Perspective on RNAi-Based Biopesticides. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 51. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. Research Progress on the Synthetic Biology of Botanical Biopesticides. Molecules 2022, 27, 3485.

- Ray, P.; Sahu, D.; Aminedi, R.; Chandran, D. Concepts and considerations for enhancing RNAi efficiency in phytopathogenic fungi for RNAi-based crop protection using nanocarrier-mediated dsRNA delivery systems. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 977502. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.S.; Thodey, K.; Trenchard, I.; Smolke, C.D. Advancing secondary metabolite biosynthesis in yeast with synthetic biology tools. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012, 12, 144–170. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Imran, M.; Feng, X.; Shen, X.; Sun, Z. Spray-induced gene silencing for crop protection: Recent advances and emerging trends. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1527944. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. The impact of genetically engineered crops on farm sustainability in the United States; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Mandel, G.N.; Marchant, G.E. The Living Regulatory Challenges of Synthetic Biology. Iowa Law Rev. 2014, 100, 155–200.

- Rinaldi, A.; Mat Jalaluddin, N.S.; Mohd Hussain, R.B.; Abdul Ghapor, A. Building public trust and acceptance towards spray-on RNAi biopesticides: Lessons from current ethical, legal and social discourses. GM Crops Food 2025, 16, 398–412. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, D.; Shen, Y. Discovery of novel bioactive natural products driven by genome mining. Drug Discov. Ther. 2018, 12, 318–328. [CrossRef]

- Tamang, P.; Upadhaya, A.; Paudel, P.; Meepagala, K.; Cantrell, C.L. Mining Biosynthetic Gene Clusters of Pseudomonas vancouverensis Utilizing Whole Genome Sequencing. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 548. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Dal Grande, F.; Schmitt, I. Genome mining as a biotechnological tool for the discovery of novel biosynthetic genes in lichens. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 993171. [CrossRef]

- Keller, N.P. Fungal secondary metabolism: regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 167–180. [CrossRef]

- Nickles, G.R.; Oestereicher, B.; Keller, N.P.; Drott, M.T. Mining for a new class of fungal natural products: The evolution, diversity, and distribution of isocyanide synthase biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 7220–7235. [CrossRef]

- Kautsar, S.A.; Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Navarro-Muñoz, J.C.; Terlouw, B.R.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; van Santen, J.A.; Tracanna, V.; Suarez Duran, H.G.; Pascal Andreu, V.; et al. MIBiG 2.0: a repository for biosynthetic gene clusters of known function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D454–D458. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Muñoz, J.C.; Selem-Mojica, N.; Mullowney, M.W.; Kautsar, S.A.; Tryon, J.H.; Parkinson, E.I.; De Los Santos, E.L.C.; Yeong, M.; Cruz-Morales, P.; Abubucker, S.; et al. A computational framework to explore large-scale biosynthetic diversity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 60–68. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Xu, X.; Yin, W.-B. Genome Mining of Epicoccum dendrobii Reveals Diverse Antimicrobial Natural Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 6691–6701. [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Song, A.; He, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Dai, W.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, S. Genome mining and biosynthetic pathways of marine-derived fungal bioactive natural products. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1520446. [CrossRef]

- Richman, E.K.; Hutchison, J.E. The nanomaterial characterization bottleneck. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 2441–2446. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Giménez, E.; Gandía, M.; Sáez, Z.; Manzanares, P.; Yenush, L.; Orzáez, D.; Marcos, J.F.; Garrigues, S. FungalBraid 2.0: Expanding the synthetic biology toolbox for the biotechnological exploitation of filamentous fungi. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1222812. [CrossRef]

- Nødvig, C.S.; Nielsen, J.B.; Kogle, M.E.; Mortensen, U.H. A CRISPR-Cas9 System for Genetic Engineering of Filamentous Fungi. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133085. [CrossRef]

- Blount, B.A.; Weenink, T.; Ellis, T. Rational diversification of a promoter providing fine-tuned expression and orthogonal regulation for synthetic biology. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33279. [CrossRef]

- Bocos-Asenjo, I.T.; Amin, H.; Mosquera, S.; Díez-Hermano, S.; Ginésy, M.; Diez, J.J.; Niño-Sánchez, J. Spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS) as a tool for the management of Pine Pitch Canker forest disease; bioRxiv: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2024.

- Zhu, S.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Yang, H.; Tao, L. Computational advances in biosynthetic gene cluster discovery and prediction. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 79, 108532. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Sherif, S.M. RNAi-Based Biofungicides as a Promising Next-Generation Strategy for Controlling Devastating Gray Mold Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2072. [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Biedenkopf, D.; Furch, A.; Weber, L.; Rossbach, O.; Abdellatef, E.; Linicus, L.; Johannsmeier, J.; Jelonek, L.; Goesmann, A.; et al. An RNAi-based control of Fusarium graminearum infections through spraying of long dsRNAs involves a plant passage and is controlled by the fungal silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005901. [CrossRef]

- Mu, F.; Xie, J.; Cheng, S.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J.; Jia, J.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Fu, Y.; Chen, T.; et al. Virome characterization of a collection of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from Australia. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2540. [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M. Integrated Pest Management: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Developments. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1998, 43, 243–270. [CrossRef]

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P.; Quaiser, A.; Duhamel, M.; Le Van, A.; Dufresne, A. The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 1196–1206. [CrossRef]

- Todorović, I.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Raičević, V.; Jovičić-Petrović, J.; Muller, D. Microbial diversity in soils suppressive to Fusarium diseases. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1228749. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.E.; Martí, J.M.; Radivojevic, T.; Jonnalagadda, S.V.R.; Gentz, R.; Hillson, N.J.; Peisert, S.; Kim, J.; Simmons, B.A.; Petzold, C.J.; et al. Machine learning for metabolic engineering: A review. Metab. Eng. 2021, 63, 34–60. [CrossRef]

- Riedling, O.; Walker, A.S.; Rokas, A. Predicting fungal secondary metabolite activity from biosynthetic gene cluster data using machine learning; bioRxiv: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).