Submitted:

02 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Oligofructans Powder

2.1.2. Inoculum Preparation

2.1.3. Oligofructans Fermentation

2.1.4. Oligofructans Powder

2.2. Analysis of Fermentation Kinetics and Properties of Oligofructans Powder

2.2.1. Sugar Contents and Short-Chain of Fructo-Oligosaccharide Using High Performance Liquid Chromatography

2.2.2. Total Oligofructans in Form of Total Free Fructose

2.3. Determination of Physicochemical Properties of Oligofructans Powder

2.3.1. Viscosity

2.3.2. pH and Thermal Stability

2.4. Structural Analysis of B. subtilis TISTR 001 Oligofructans Powder

2.4.1. Fourier Transform-Infrared Spectroscopy

2.4.2. 1H and 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

2.4.3. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry

2.5. Evaluation of Bioactivity Properties of Oligofructans Powders

2.5.1. Antioxidant Activity

2.5.2. Cytotoxicity Test

2.6. Statical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

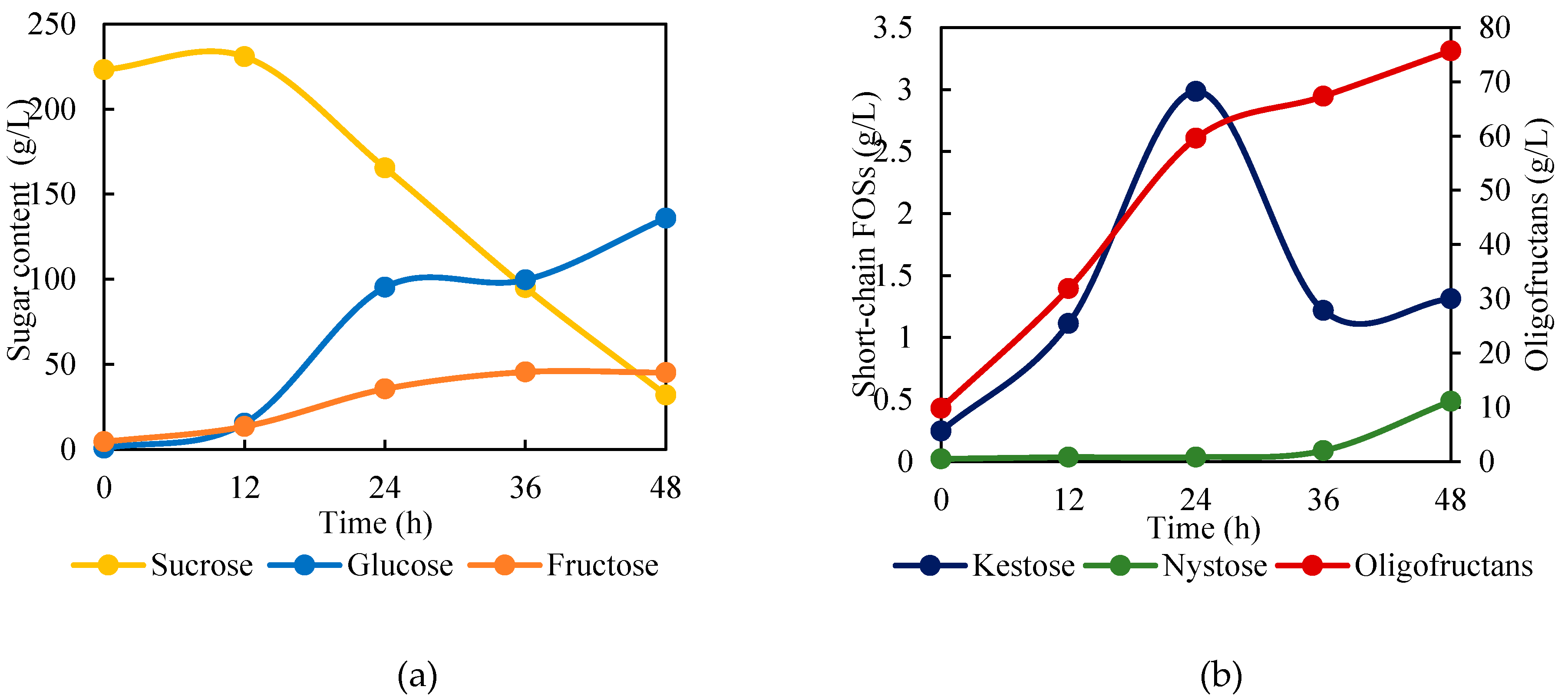

3.1. Production of Oligofructans Powder by B. subtilis TISTR001

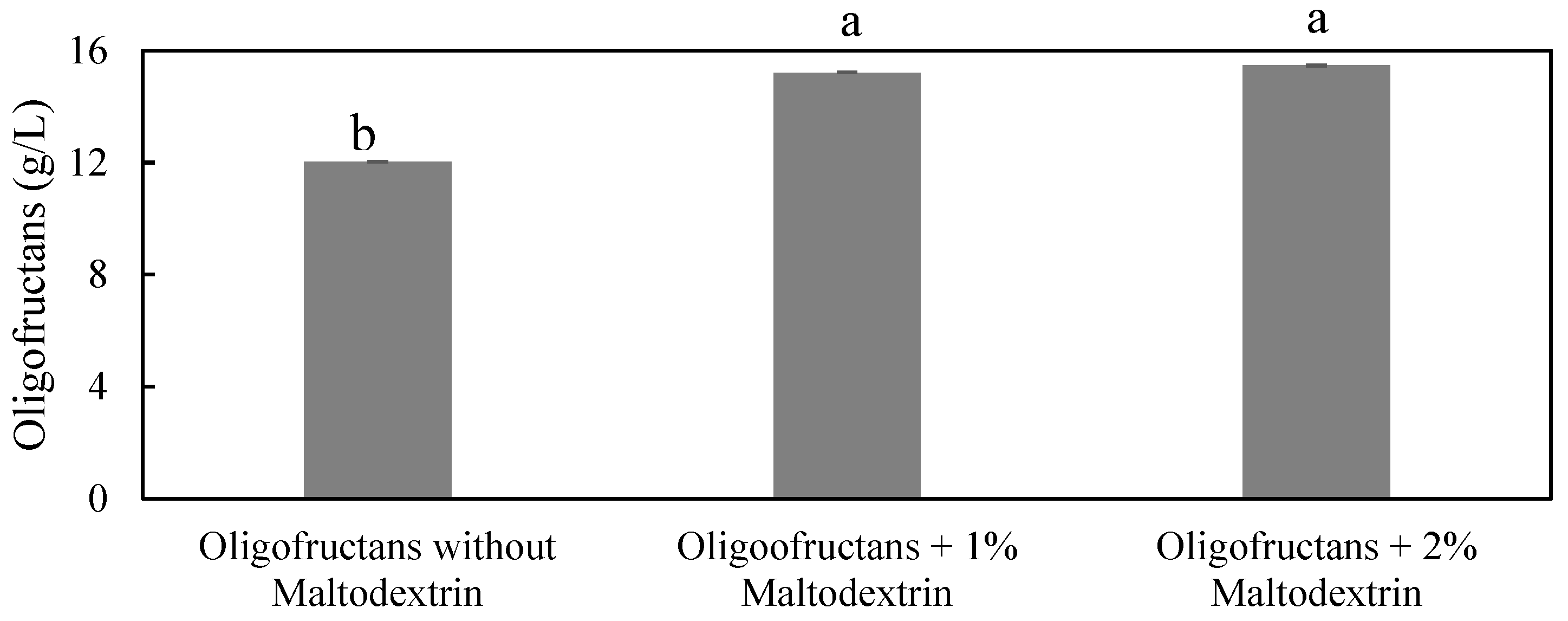

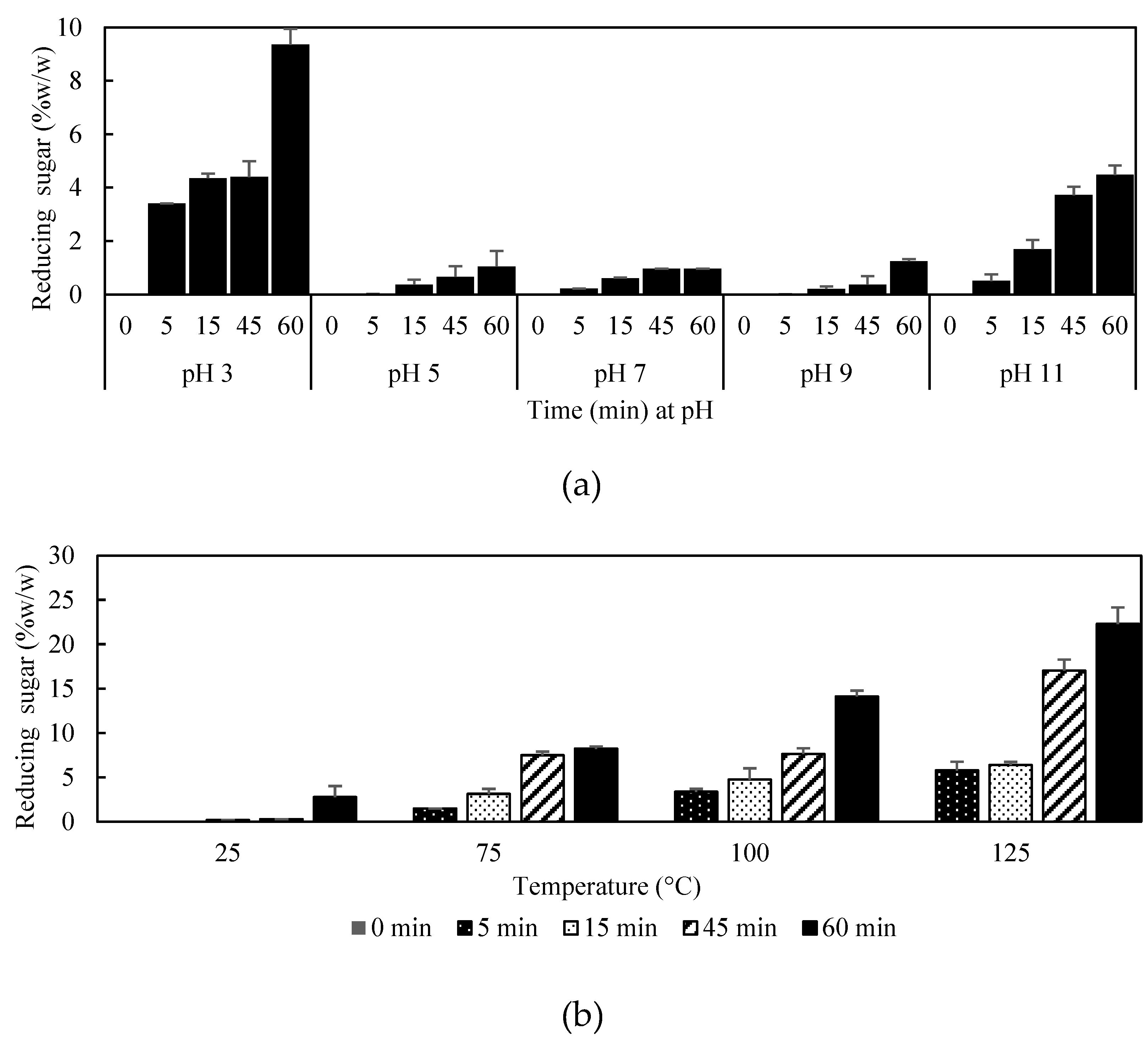

3.2. Physical Properties of Oligofructans Powder

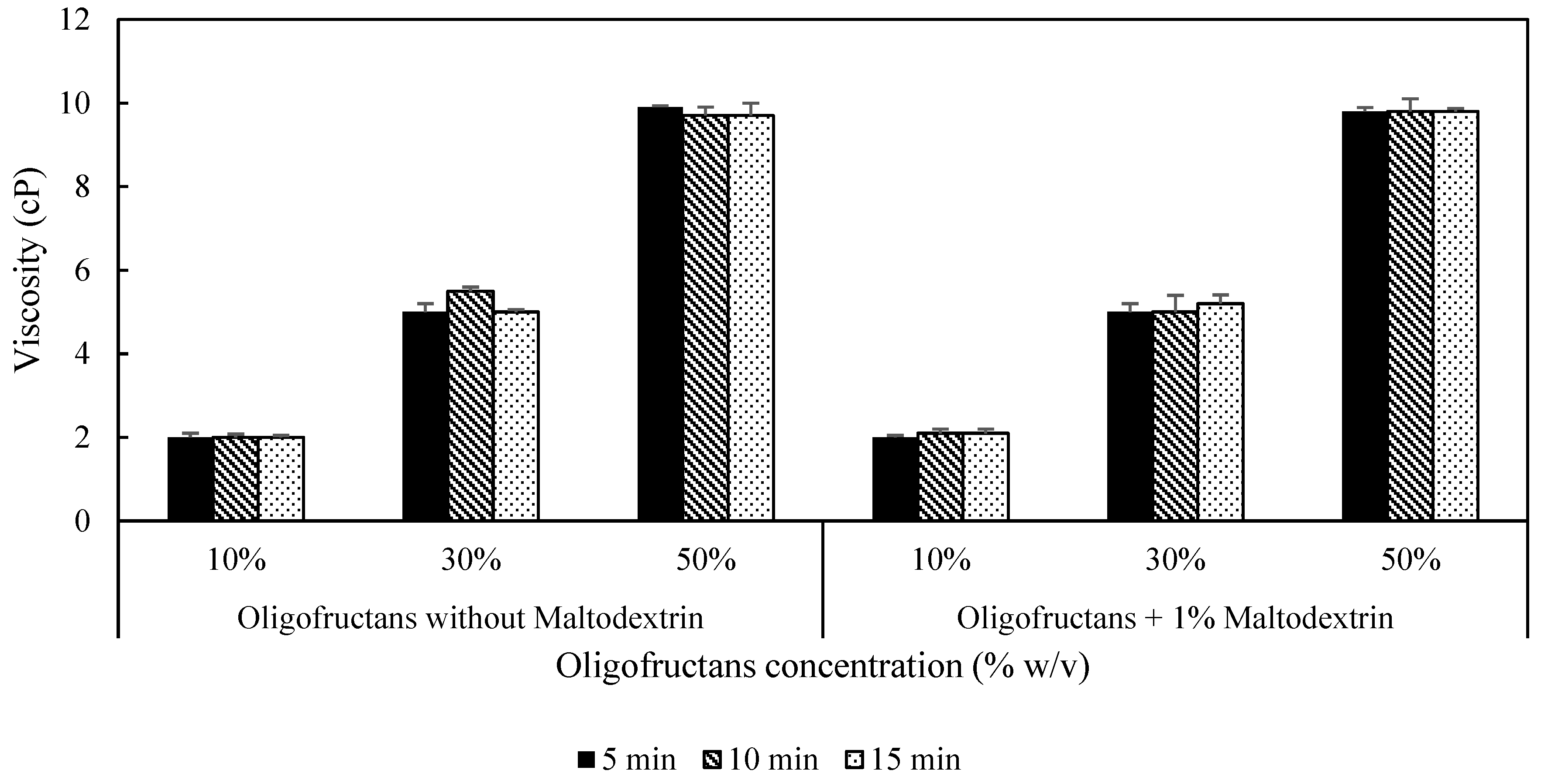

3.2.1. Viscosity of Oligofructans Solution

3.3. Structure of B. subtilis TISTR 001 Oligofructans Powder

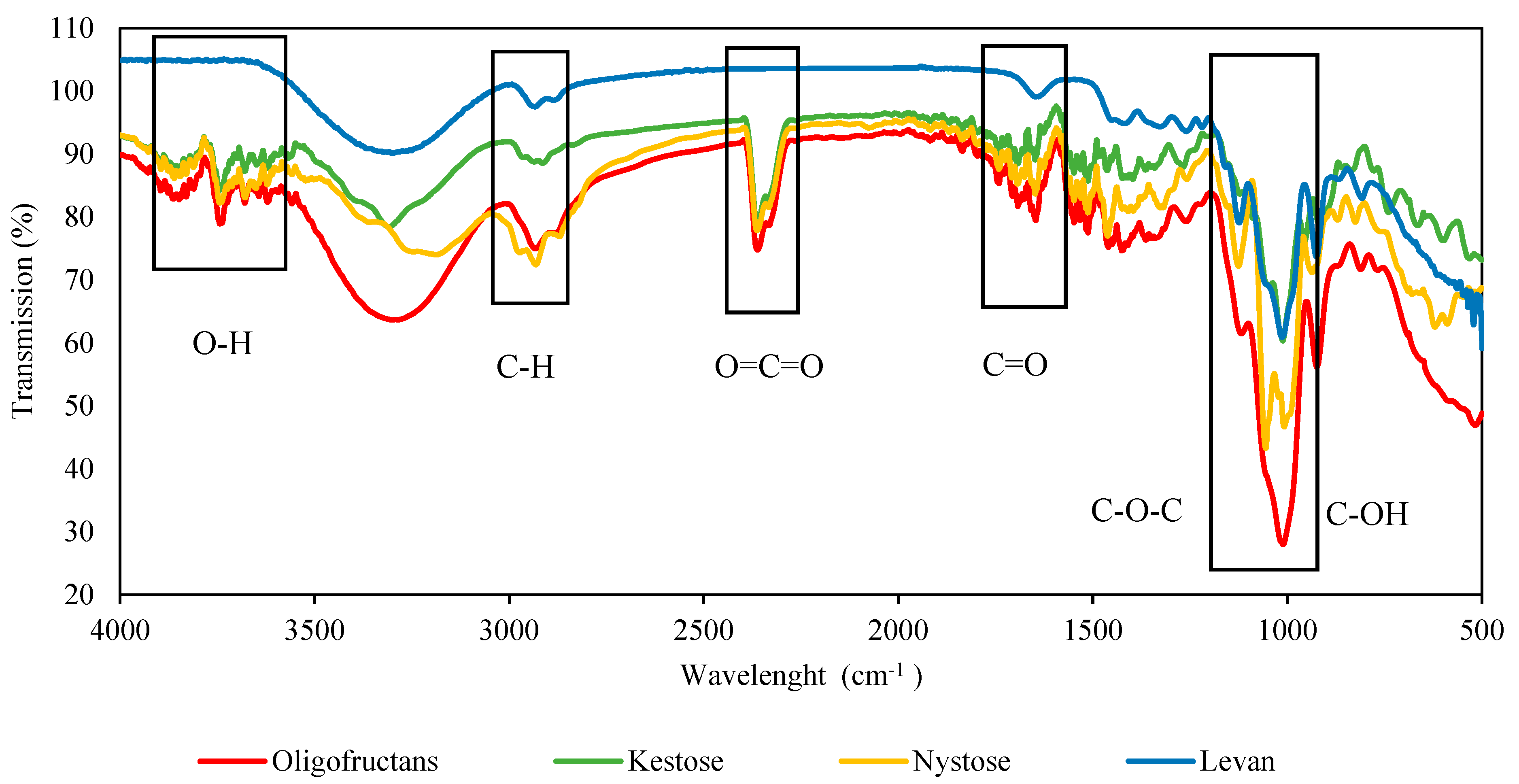

3.3.1. FTIR Spectra

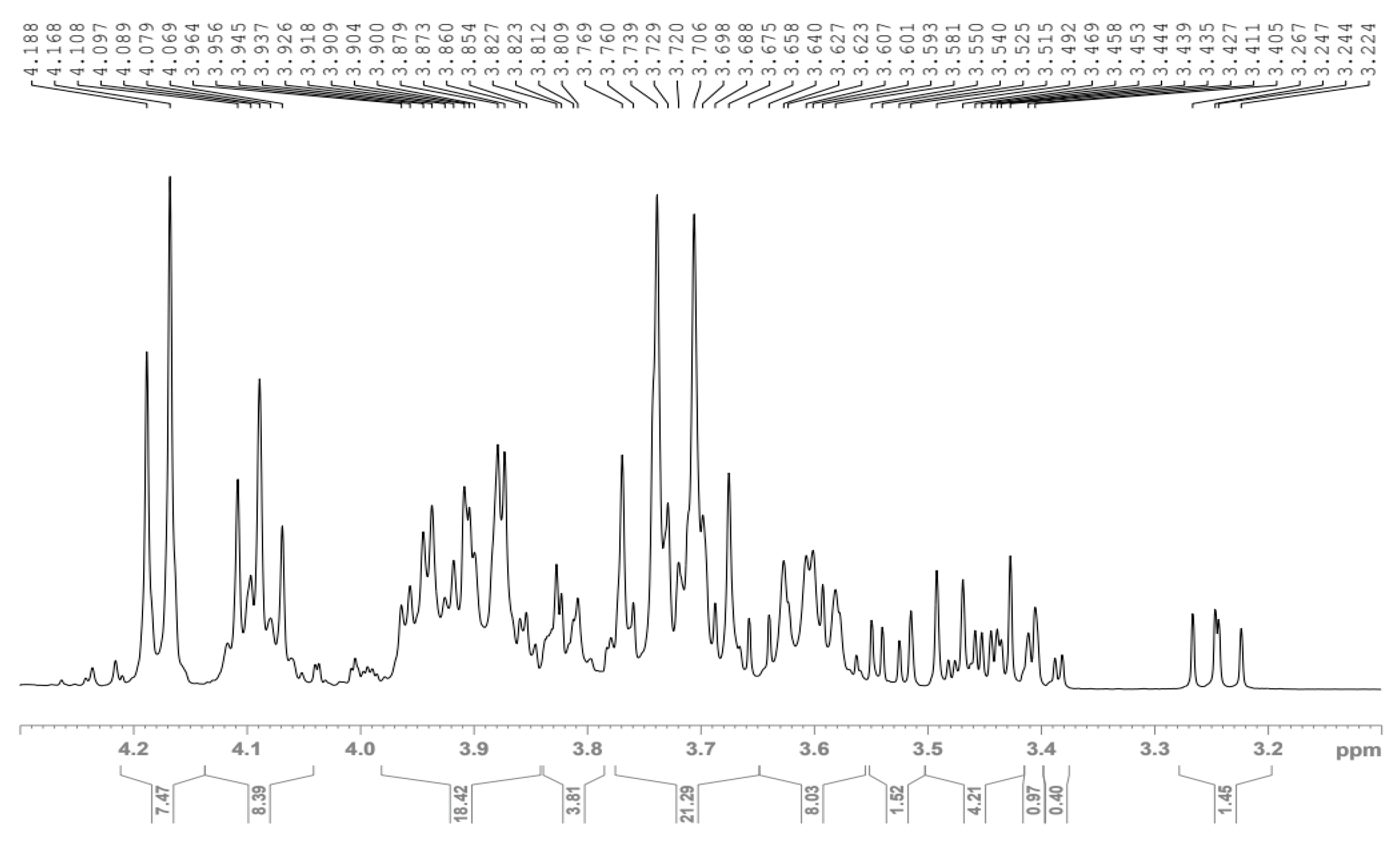

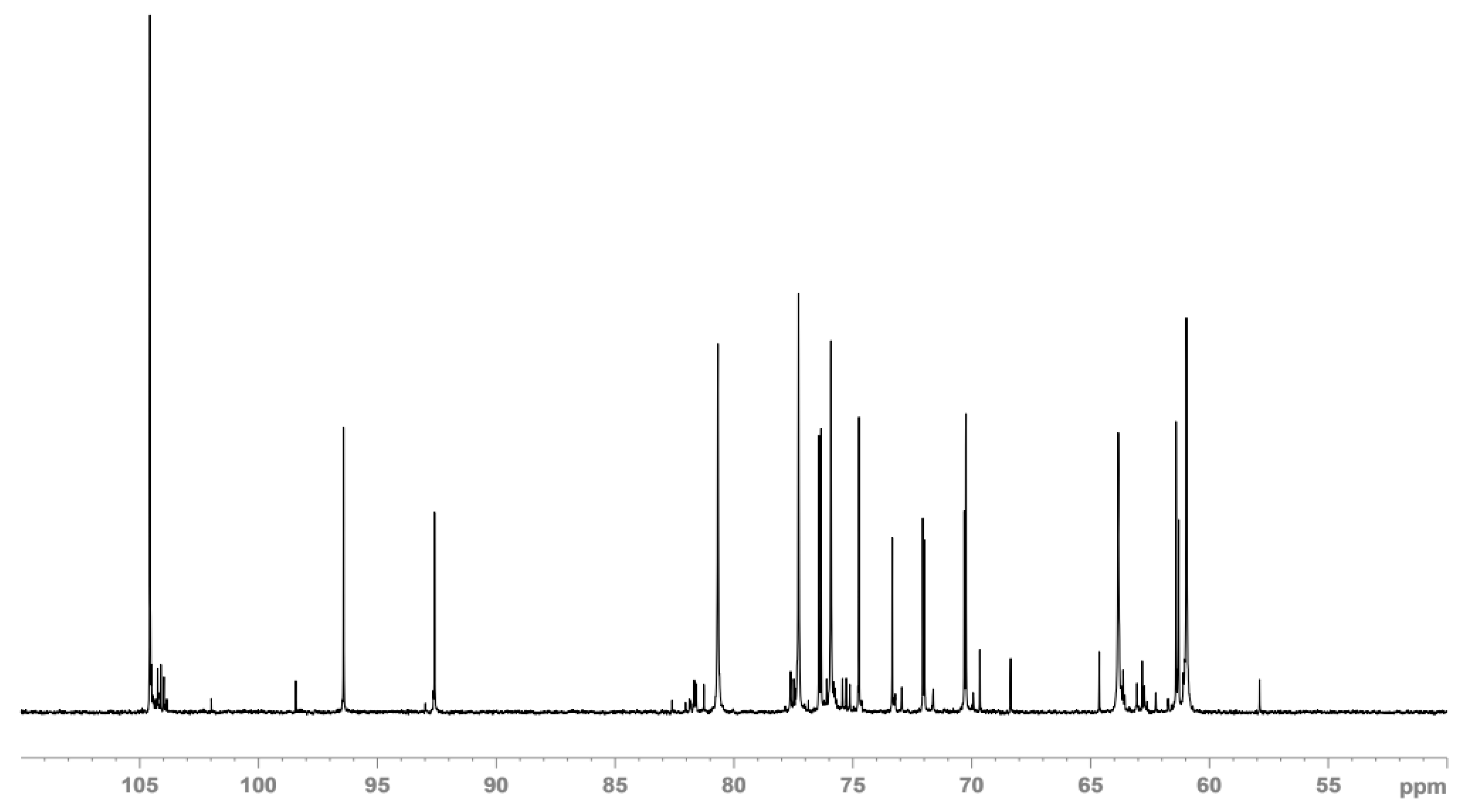

3.3.2. NMR Spectra

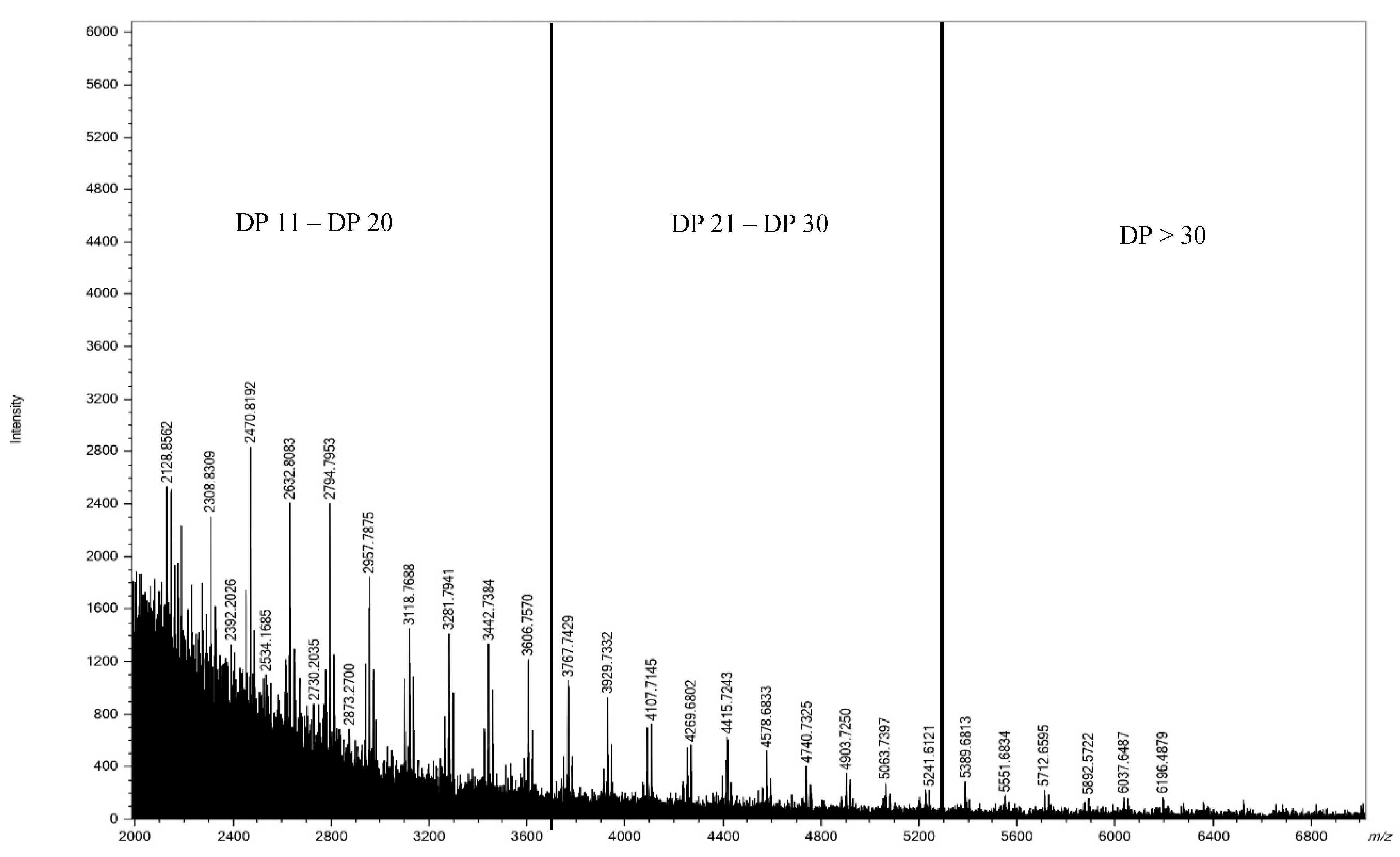

3.3.3. MALDI-TOF-Mass Spectrum

3.4. Bioactivity Properties of Oligofructans Powder

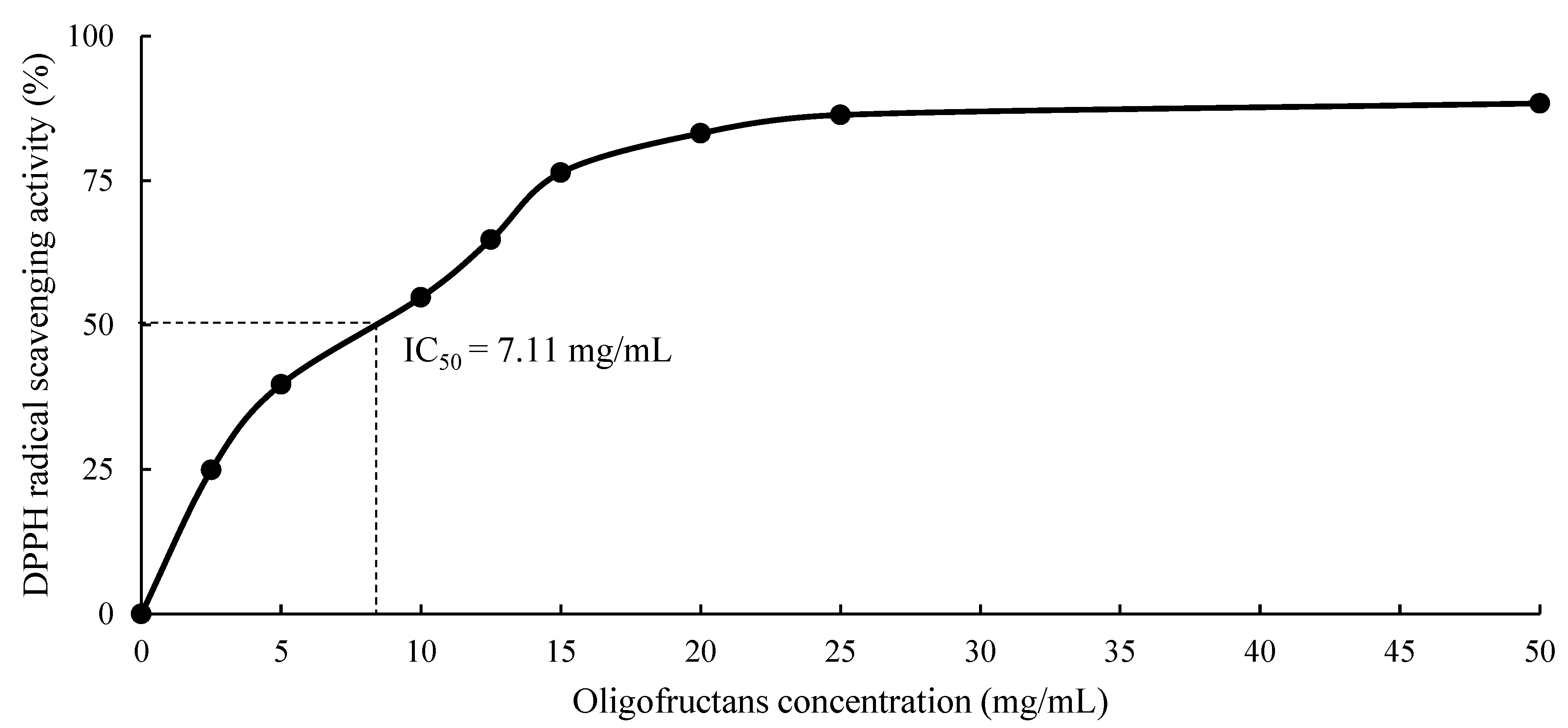

3.4.1. Antioxidant Activity

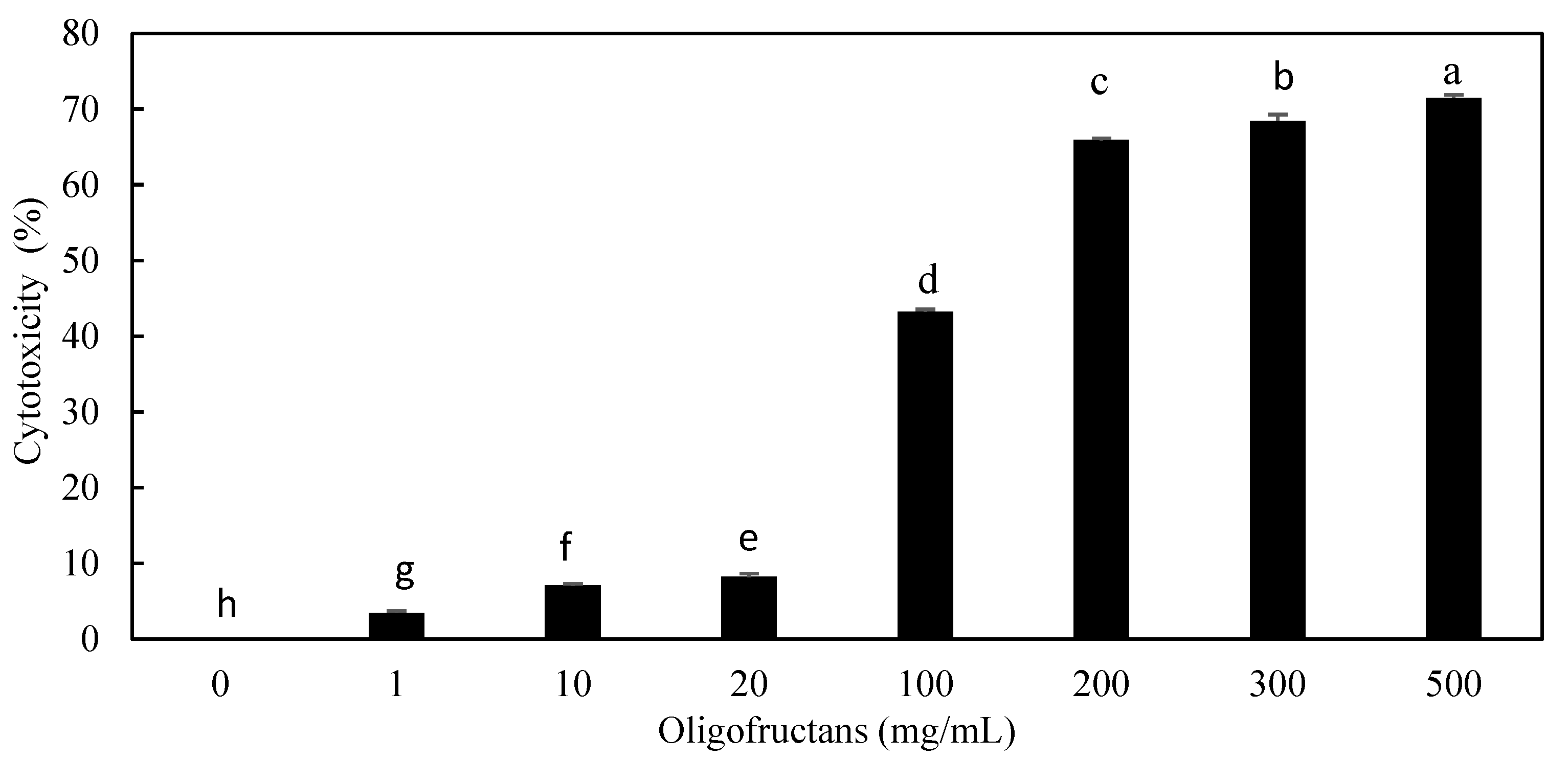

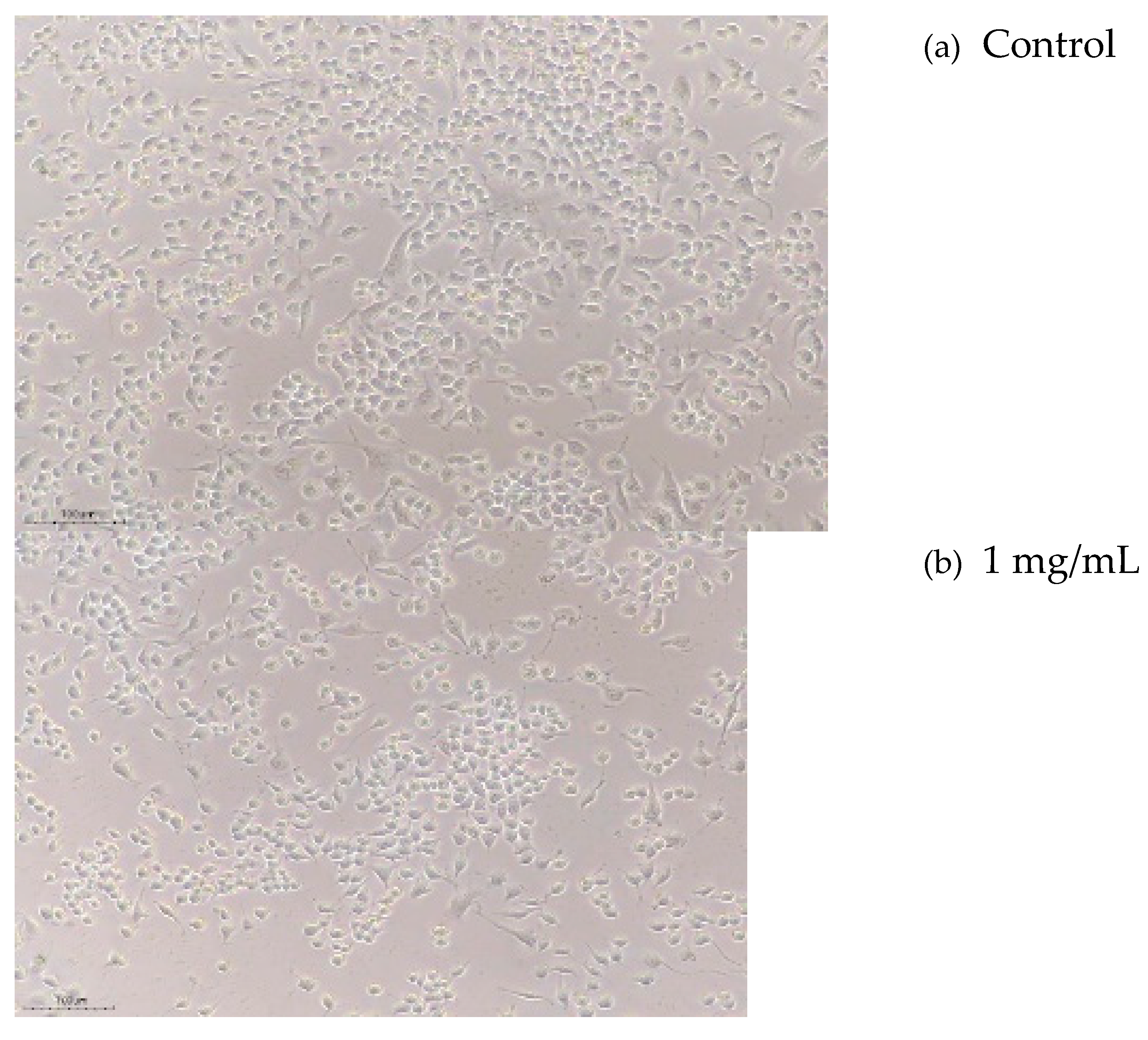

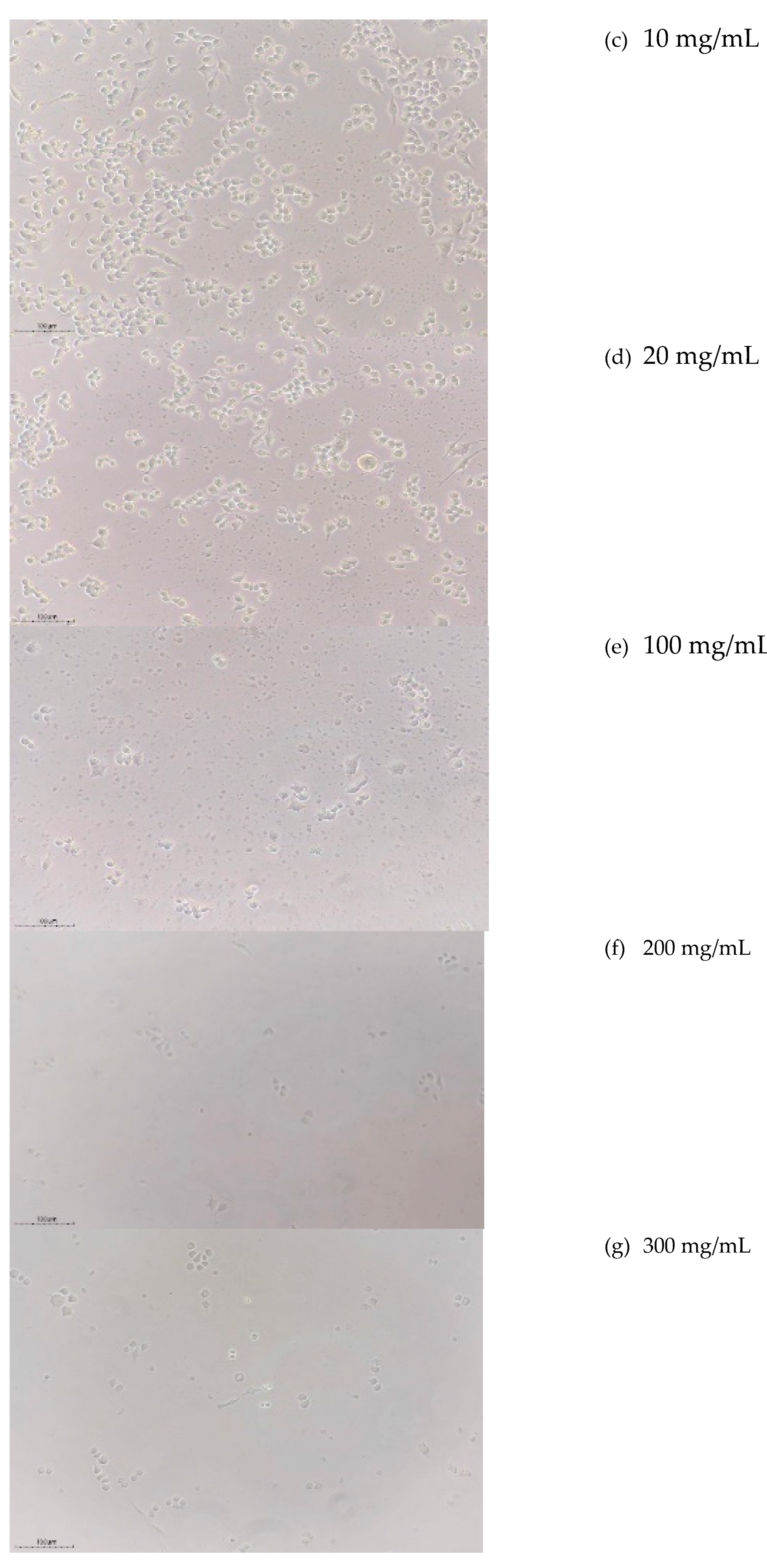

3.4.2. Cytotoxicity

4. Conclusion

Funding

Authors Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bersaneti, G. T.; Pan, N. C.; Baldo, C.; Celligoi, M. A. P. C. Co-production of fructo-oligosaccharides and levan by levansucrase from Bacillus subtilis natto with potential application in the food industry. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnolog. 2018, 184, 838–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninchan, B.; C. Noidee. Optimization of oligofructans production from sugarcane juice fermentation using Bacillus subtilis TISTR001. Agriculture and Natural Resources 2021, 55, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, M.; Serizawa, R.; Tanuma, M.; Kikuchi, A.; Sadahiro, J.; Tagami, T.; Lang, W.; Kimura, A. Molecular insight into regioselectivity of transfructosylation catalyzed by GH68 levansucrase and β-fructofuranosidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2021, 296, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, D.; Lavid, N.; Schwartz, A.; Shoham, G.; Danino, D.; Shoham, Y. Two active forms of Zymomonas mobilis levansucrase: An ordered microfibril structure of the enzyme promotes levan polymerization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008, 283, 32209–32217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noidee, C.; Ninchan, B.; Ninchan, B. Investigation of optimized microbial oligofructans production by Bacillus subtilis TISTR 001 using response surface methodology. Sugar Tech. 2024, 26, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghith, K. S.; Dahech, I.; Belghith, H.; Mejdoub, H. Microbial production of levansucrase for synthesis of fructooligosaccharides and levan. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2012, 50, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Dietary fibers and their emerging benefits for liver health: The role of oligofructans. Nutrition Reviews. 2020, 78, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkeblia, N. . Fructooligosaccharides and fructans analysis in plants and food crops. Journal of Chromatography A, 2013, 1313, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherade, M.; Solanke, S.; Tawar, M.; Wankhede, S. Fructooligosaccharides: A comprehensive review. Journal of Ayurvedic and Herbal Medicine. 2021, 7, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G. R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M. E.; Prescott, S. L.; Reimer, R. A.; Salminen, S. J.; Scott, T.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; Vevbeke, V.; Reid, G. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M. Prebiotics: The concept revisited. The Journal of Nutrition 2007, 137, 830S–837S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, X. The crucial function of gut microbiota on gut-liver repair. hLife 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A. , Debelius, J., Brenner, D. A., Karin, M., Loomba, R., Schnabl, B., & Knight, R. The gut–liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2018, 15, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P. D.; Neyrinck, A. M.; Fava, F.; Knauf, C.; Burcelin, R. G.; Tuohy, K. M.; Gibson, G.R.; Delzenne, N. M. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G. R.; Roberfroid, M. B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Introducing the concept of prebiotics. The Journal of Nutrition. 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hrout, A. A.; Cervantes-Gracia, K.; Chahwan, R.; Amin, A. Modelling liver cancer microenvironment using a novel 3D culture system. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, P.; Rozek, L. S.; Pongnikorn, D.; Sriplung, H.; Meza, R. Comparison of cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma incidence trends from 1993 to 2012 in Lampang, Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 9551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. 2024. Hospital-based cancer registry 2022. Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. Retrieved from http://www.nci.go.th.

- Bosscher, D.; Van Loo, J.; Franck, A. Inulin and oligofructose as prebiotics in the prevention of intestinal infections and diseases. Nutrition Research Reviews 2006, 19, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femia, A. P.; Luceri, C.; Dolara, P.; Giannini, A.; Biggeri, A.; Salvadori, M.; Clune, Y.; Collins, K. J.; Paglierani, M.; Caderni, G. Antitumorigenic activity of the prebiotic inulin enriched with oligofructose in combination with the probiotics Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis on azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rats. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolida, S.; Tuohy, K.; Gibson, G. R. Prebiotic effects of inulin and oligofructose. British Journal of Nutrition. 2002, 87, S193–S197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.; Simões, L. S.; Gonçalves, D. A.; Berni, P.; Teixeira, J. A. Fructooligosaccharides production and the health benefits of prebiotics. In Current developments in biotechnology and bioengineering. 2022, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool-Zobel, B. L. Inulin-type fructans and reduction in colon cancer risk: review of experimental and human data. British Journal of Nutrition. 2005, 93(S1), S73–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahech, I.; Belghith, K. S.; Belghith, H.; Mejdoub, H. Partial purification of a Bacillus licheniformis levansucrase producing levan with antitumor activity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2012, 51, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrutha, N.; Hebbar, H. U.; Prapulla, S. G.; Raghavarao, K. S. M. S. Effect of additives on quality of spray-dried fructooligosaccharide powder. Drying Technology. 2014, 32, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showa Denko, K.K. 2021. Fructo-oligosaccharide Syrup (NH2P-50 4E). Showa Denko K.K. Tokyo, Japan. https://www.shodex.com/en/dc/03/03/17.html, 11 July 2021.

- Vertical Chromatography, Co. Ltd. 2021. VertiSepTM sugar HPLC columns. Vertical Chromatography Co. Ltd. Nonthaburi, Thailand. http://www.vertichrom.com/pdf/hplc_sugar.pdf, 11 July 2021.

- Nelson, N. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1944, 153, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glibowski, P.; Bukowska, A. The effect of pH, temperature and heating time on inulin chemical stability. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria. 2011, 10, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth, R.; Siddartha, G.; Reddy, C. H. S.; Harish, B. S.; Ramaiah, M. J.; Uppuluri, K. B. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory levan produced from Acetobacter xylinum NCIM2526 and its statistical optimization. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015, 123, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarlina, V. P.; Rizky, A.; Diva, A.; Zaida, Z.; Djali, M.; Andoyo, R.; Lani, M. N. Maltodextrin concentration on the encapsulation efficiency of tempeh protein concentrated from Jack Bean (Canavalia ensiformis): Physical, chemical, and structural properties. International Journal of Food Properties. 2024, 27, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobulska, M.; Zbicinski, I. Advances in spray drying of sugar-rich products. Drying Technology. 2021, 39, 1774–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprodu, I.; Banu, I.; Banu, I. . Effect of starch and dairy proteins on the gluten free bread formulation based on quinoa. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization. 2021, 15, 2264–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siccama, J. W.; Pegiou, E.; Zhang, L.; Mumm, R.; Hall, R. D.; Boom, R. M.; Schutyser, M. A. I. , Maltodextrin improves physical properties and volatile compound retention of spray-dried asparagus concentrate. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2021, 142, 111058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Thakur, N.; Kajla, P.; Thakur, S.; Punia, S. Application of encapsulation technology in edible films. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5, 734921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glibowski, P.; Biaduń, P. Chemical stability of inulin in acidic environment as an effect of a long-term storage. Polish Journal of Natural Sciences 2021, 35, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Matusek, A.; Merész, P.; Le, T. K. D.; Örsi, F. Effect of temperature and pH on the degradation of fructo-oligosaccharides. European Food Research and Technology 2009, 228, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensink, M. A.; Frijlink, H. W.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K.; Hinrichs, W. L. Inulin, a flexible oligosaccharide. II: Review of its pharmaceutical applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 134, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramsangtienchai, P.; Kongmon, T.; Pechroj, S.; Srisook, K. Enhanced production and immunomodulatory activity of levan from the acetic acid bacterium, Tanticharoenia sakaeratensis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 163, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yue, X.; Zeng, Y.; Hua, E.; Wang, M.; Sun, Y. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens levan and its silver nanoparticles with antimicrobial properties. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 2018, 32, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A. J. B.; Gonçalves, R. A. C.; Chierrito, T. P. C.; Dos Santos, M. M.; de Souza, L. M.; Gorin, P. A. J.; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M. Structure and degree of polymerisation of fructooligosaccharides present in roots and leaves of Stevia rebaudiana (Bert.) Bertoni. Food Chemistry. 2011, 129, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Xu, X.; Gao, C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z. Levan-producing Leuconostoc citreum strain BD1707 and its growth in tomato juice supplemented with sucrose. Applied and Environmental Microbiolog. 2016, 82, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madia, V. N.; De Vita, D.; Messore, A.; Toniolo, C.; Tudino, V.; De Leo, A.; Pindinello, I.; Lalongo, D.; Saccoliti, F.; D’Ursa, A.M.; Grimaldi, M.; Ceccobelli, P.; Scipione, L.; Santo, R.D.; Ialongo, D. Analytical characterization of an inulin-type fructooligosaccharide from root-tubers of Asphodelus ramosus L. Pharmaceuticals. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cérantola, S.; Kervarec, N.; Pichon, R.; Magné, C.; Bessieres, M. A.; Deslandes, E. NMR characterisation of inulin-type fructooligosaccharides as the major water-soluble carbohydrates from Matricaria maritima (L.). Carbohydrate Research. 2004, 339, 2445–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. K.; Park, Y. H.; Shin, B. A.; Choi, E. S.; Park, Y. R.; Akaike, T.; Cho, C.S. Synthesis and characterization of fructo-oligosaccharides produced by β-fructofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger ATCC 20611. Carbohydrate Research. 2000, 328, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, P. F. P.; Iacomini, M.; Cordeiro, L. M. Chemical characterization of fructooligosaccharides, inulin and structurally diverse polysaccharides from chamomile tea. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2019, 214, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Gallagher, J. A.; Ratcliffe, I.; Williams, P. A. Determination of the degree of polymerisation of fructans from ryegrass and chicory using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and gel permeation chromatography coupled to multiangle laser light scattering. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016, 53, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; You, H. J.; Lee, Y. G.; Jeong, Y.; Johnston, T. V.; Baek, N. I.; Ku, S.; Ji, G. E. Production, structural characterization, and in vitro assessment of the prebiotic potential of butyl-fructooligosaccharides. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020, 21, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, D.; Liu, C.; Wu, X. Z.; Dong, C. X.; Zhou, J. Structural characterization and anti-tumor effects of an inulin-type fructan from Atractylodes chinensis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2016, 82, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasikumar, J. M.; Erba, O.; Egigu, M. C. In vitro antioxidant activity and polyphenolic content of commonly used spices from Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Cui, J. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cichorium intybus root extract using orthogonal matrix design. Journal of Food Science. 2013, 78, M258–M263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H. M.; Zhou, H. Z.; Yang, J. Y.; Li, R.; Song, H.; Wu, H. X. X. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities of inulin. PloS One. 2018, 13, e0192273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roupar, D.; Coelho, M. C.; Gonçalves, D. A.; Silva, S. P.; Coelho, E.; Silva, S.; Coimbra, M.A.; Pintada, M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Nobre, C. Evaluation of microbial-fructo-oligosaccharides metabolism by human gut microbiota fermentation as compared to commercial inulin-derived oligosaccharides. Foods 2022, 11, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.; Miller, N.; Paganga, G. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends in Plant Science 1997, 2, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungland, B. C.; Meyer, D. Nondigestible oligo-and polysaccharides (Dietary Fiber): their physiology and role in human health and food. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2002, 1, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gong, X.; Xu, J.; Guo, Y. Construction of inulin-based selenium nanoparticles to improve the antitumor activity of an inulin-type fructan from chicory. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 210, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Elmén, L.; Segota, I.; Xian, Y.; Tinoco, R.; Feng, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Munoz, R.R.S.; Schmaltx, R.; Bradley, L.M.; Ramer-Tait, A.; Zarecki, R.; Long, T.; Peterson, S.N.; Ze’ev, A. R. Prebiotic-induced anti-tumor immunity attenuates tumor growth. Cell Reports 2020, 30, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M. B. Introducing inulin-type fructans. British Journal of Nutrition 2005, 93, S13–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharib, S. A. Anticancer and antioxidant effects of fructooligosaccharide (FOS) on chemically-induced colon cancer in rats. Electronic Journal of Polish Agricultural Universities 2016, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).