Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Collection of Wild Edible Mushroom Mycelium

2.3. Fungal Genomic DNA Extraction

2.4. Species Identification of Mushrooms

2.5. In-House Cultivation of Mushrooms

2.6. The Extraction of Crude Polysaccharides

2.7. Determination of Total Carbohydrate

2.8. Determination of Reducing Sugar, Protein Content, and Phenolic Compounds

2.9. Simulation of Human Gastrointestinal Digestion

2.10. Selection and Allocation of Volunteers for the Feces Donation

2.11. Fecal Slurry Preparation

2.12. In Vitro Batch Fermentation

2.13. Extraction and Qualification of Genomic DNA

2.14. Metagenomics 16S rRNA Sequencing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Species Identification of Mushrooms

3.2. Deposition of Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequence in the NCBI Database

3.3. Cultivation of Mushrooms

3.4. Compound Component in Extracted Crude Polysaccharides

3.5. Characteristics of Volunteers for the Feces Donation

3.6. Total Number of Fermentation Treatments

3.7. Verification of the Genomic DNA Extracted Before and After the Fermentation

3.8. The Quality of Nucleotide Sequencing Output

3.9. Bacterial Species Present in the Samples Were Almost Detected and Analyzed

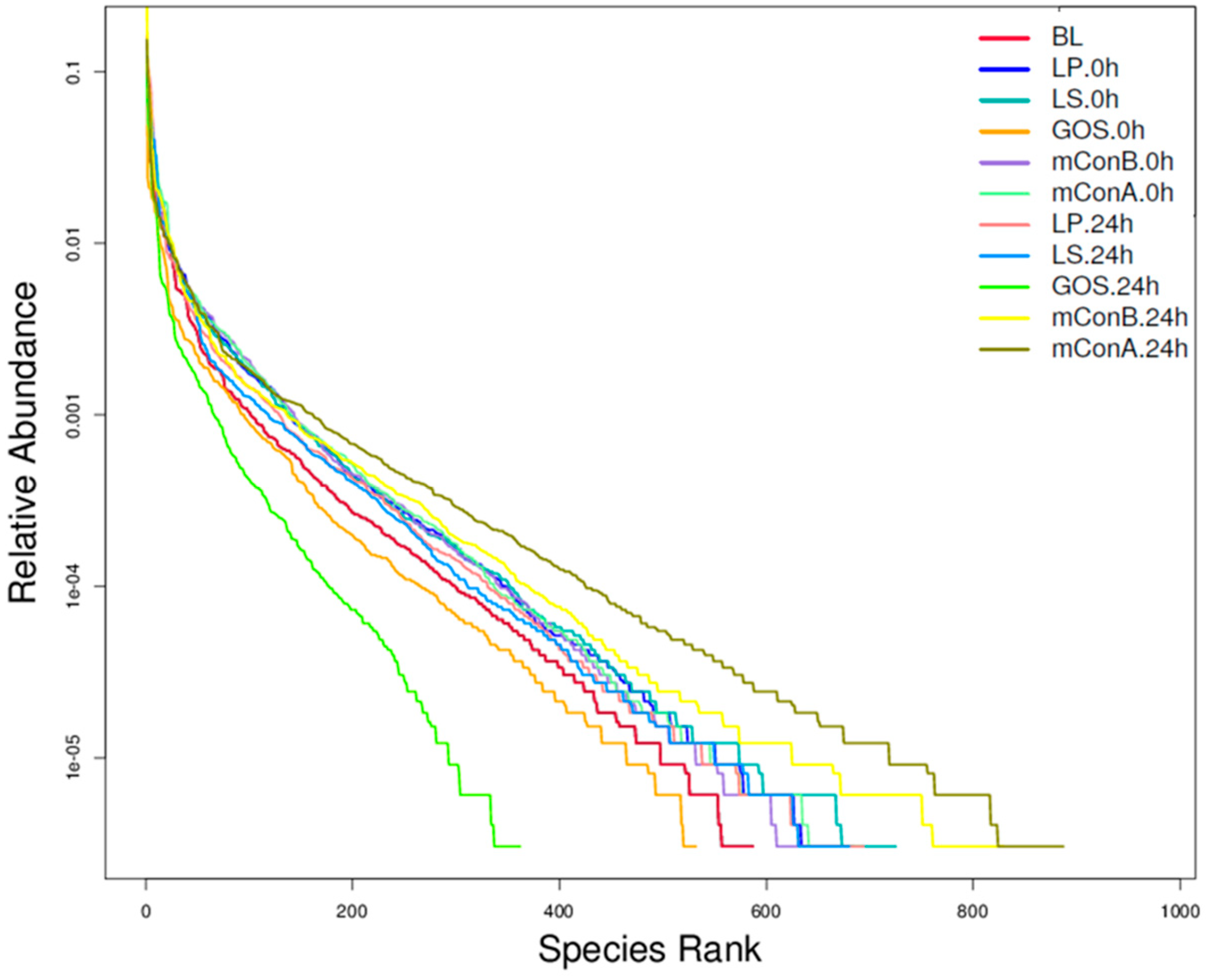

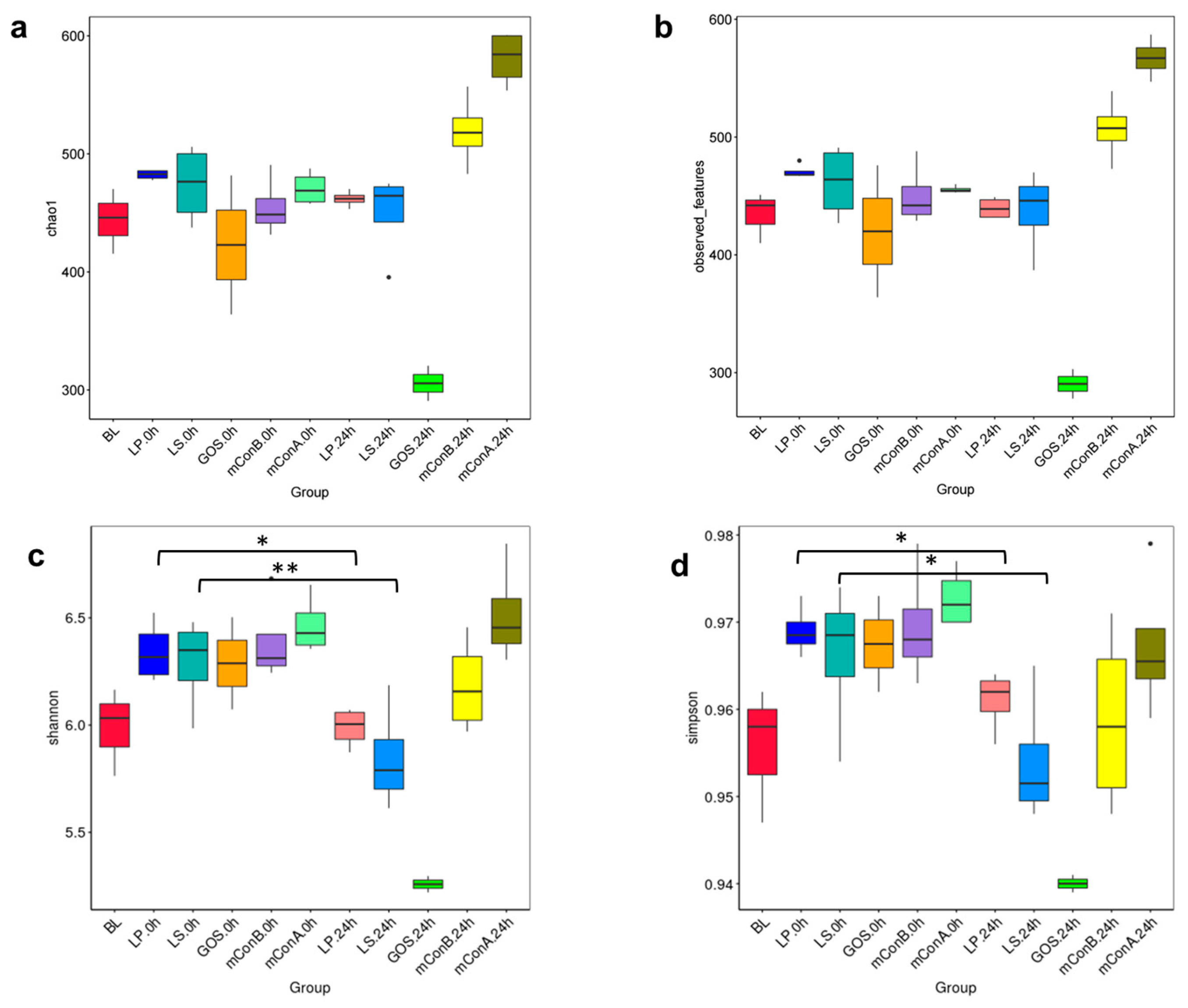

3.10. Crude Polysaccharides Altered the Diversity of Gut Microbiota

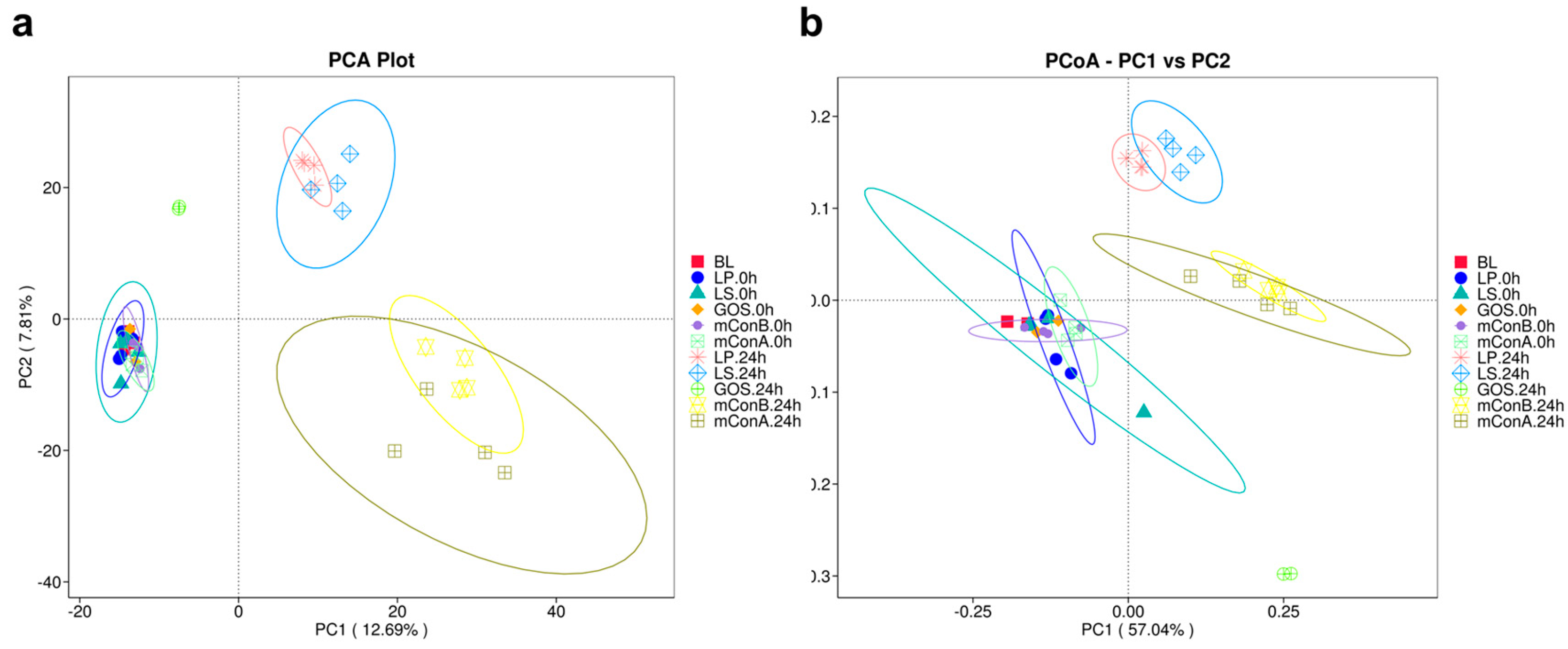

3.11. Beta Diversity Analysis Shows a Clear Distinction of Treatment Groups

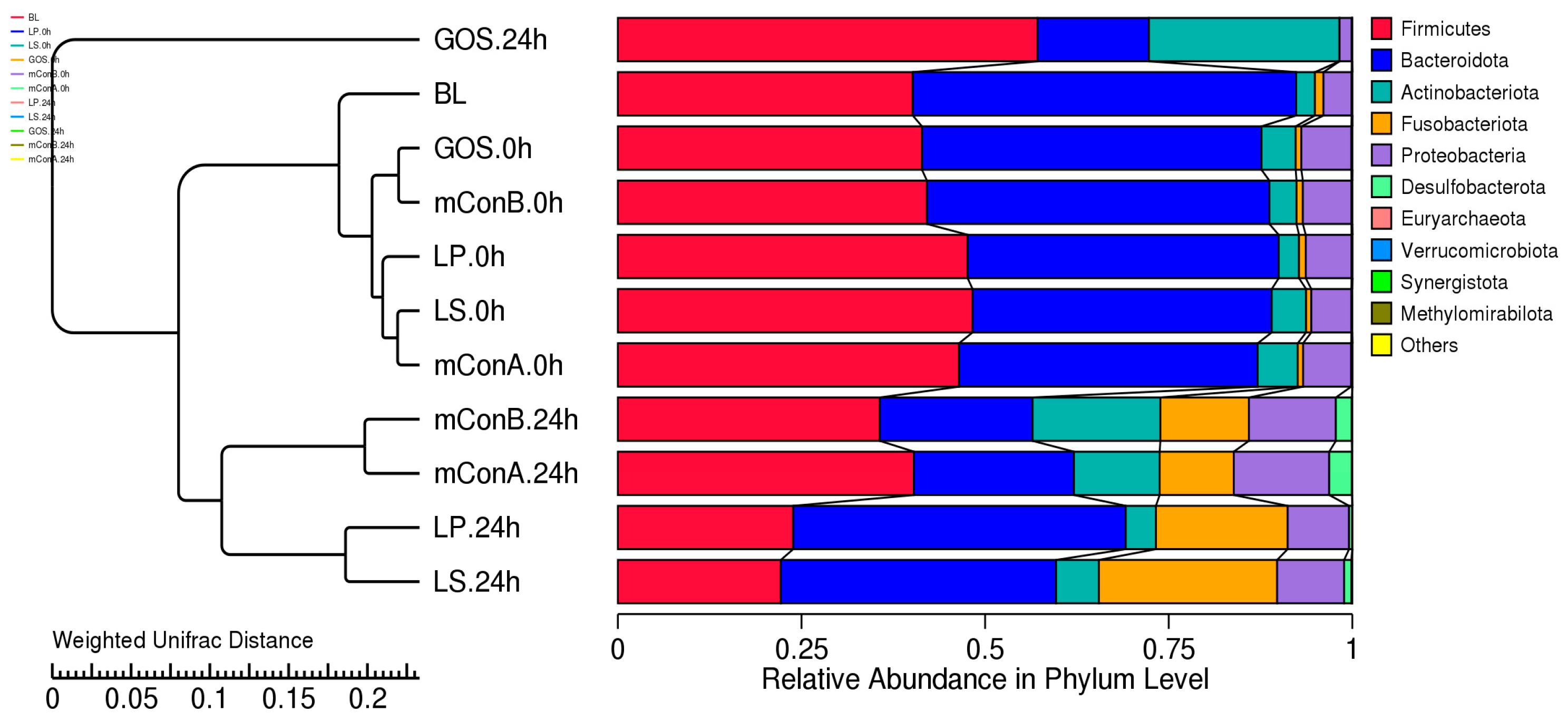

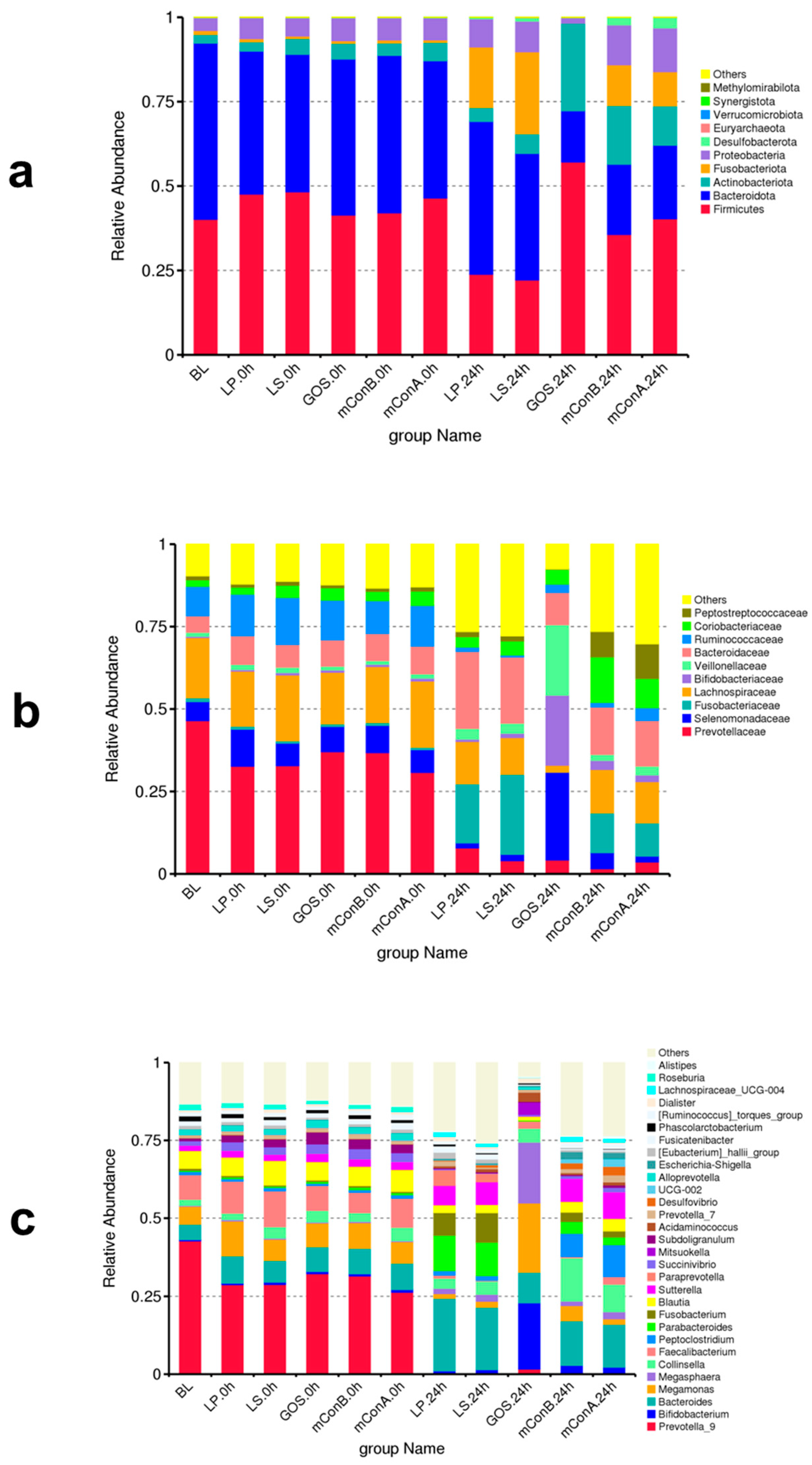

3.12. Effect of Crude Polysaccharides LP and LS on the Fecal Gut Bacteriome at Different Taxonomy Levels

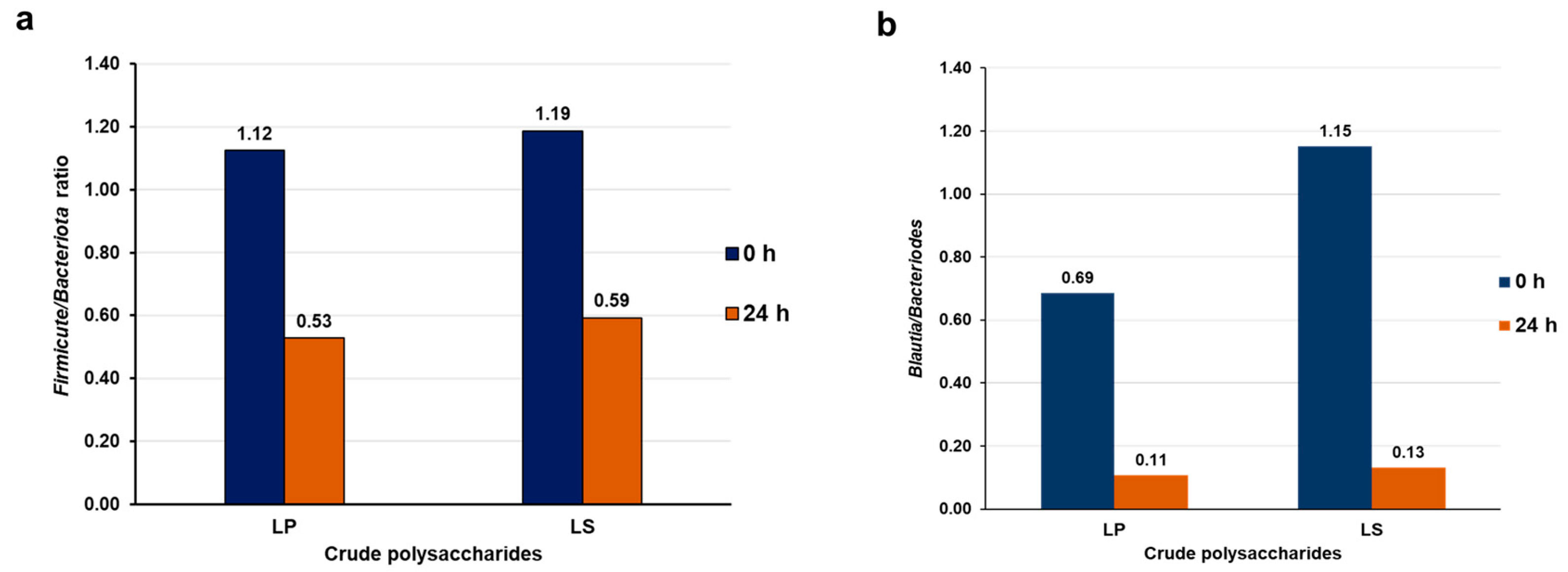

3.13. Crude Polysaccharides Reduced the Ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes and Blautia/Bacteroides

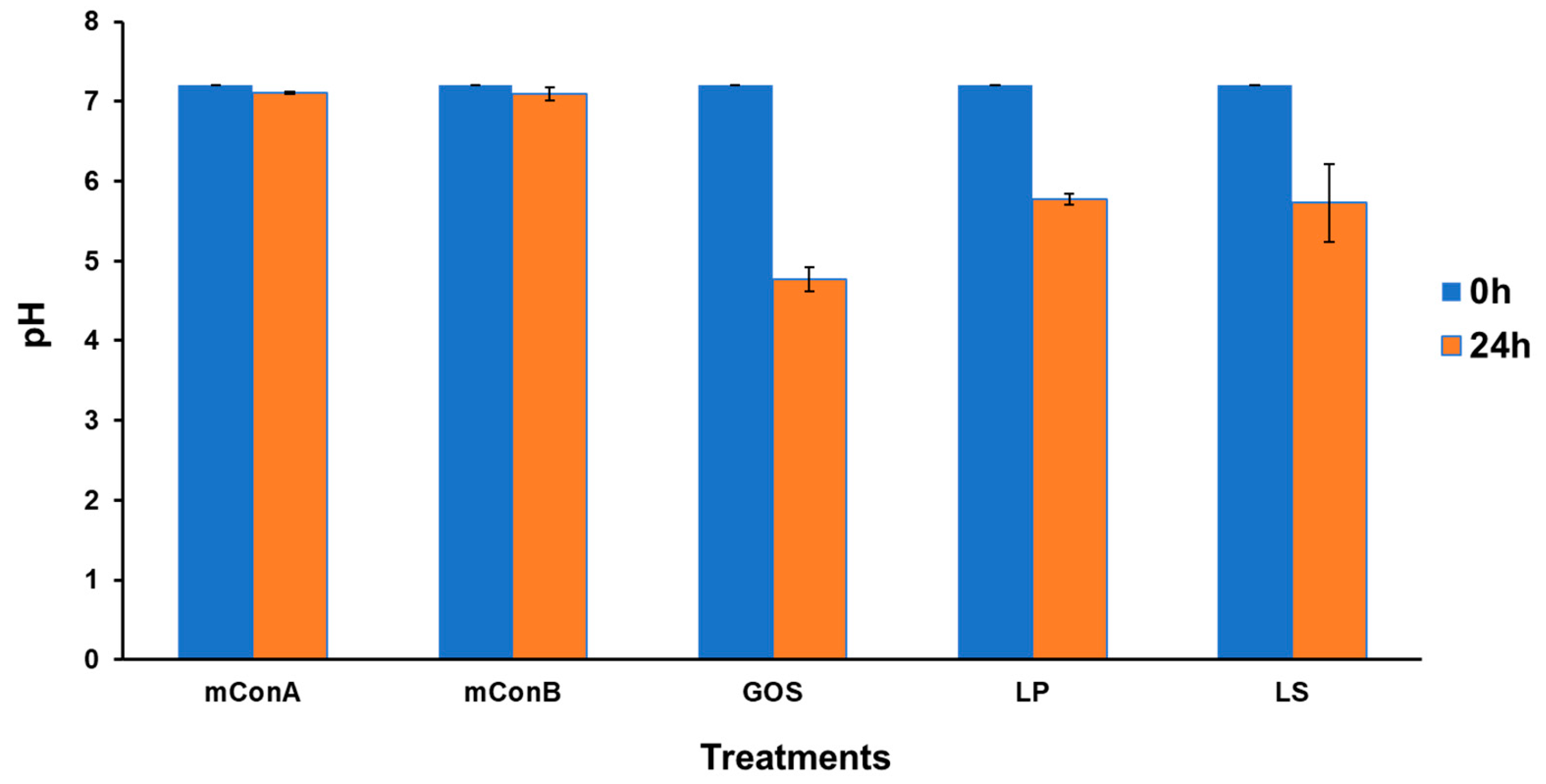

3.14. Changing of pH after the Fermentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, K.E.; Lynch, S.V. Microbiota in Allergy and Asthma and the Emerging Relationship with the Gut Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An Obesity-Associated Gut Microbiome with Increased Capacity for Energy Harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, K.; Li, J.; Li, K.; Hu, C.; Gao, Y.; Chen, M.; Hu, R.; Liu, Y.; Chi, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Disordered gut microbiota and alterations in metabolic patterns are associated with atrial fibrillation. GigaScience 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Marzal, L.N.; Rojas-Velazquez, D.; Rigters, D.; Prince, N.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Perez-Pardo, P.; Lopez-Rincon, A. A robust microbiome signature for autism spectrum disorder across different studies using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, H. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and cancers: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. An Update on Prebiotics and on Their Health Effects. Foods 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davani-Davari, D.; Negahdaripour, M.; Karimzadeh, I.; Seifan, M.; Mohkam, M.; Masoumi, S.J.; Berenjian, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods 2019, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Islam, F.; -Or-Rashid, H.; Al Mamun, A.; Rahaman, S.; Islam, M.; Meem, A.F.K.; Sutradhar, P.R.; Mitra, S.; Mimi, A.A.; et al. The Gut Microbiota (Microbiome) in Cardiovascular Disease and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 903570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R.; Nowacka-Jechalke, N.; Juda, M.; Malm, A. The preliminary study of prebiotic potential of Polish wild mushroom polysaccharides: the stimulation effect on Lactobacillus strains growth. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P.; Vlassopoulou, M.; Zervou, M.; Xanthakos, E.; Moulos, P.; Koutrotsios, G.; Zervakis, G.I.; Kerezoudi, E.N.; Mitsou, E.K.; Saxami, G.; et al. In Vitro Fermentation of Pleurotus eryngii Mushrooms by Human Fecal Microbiota: Metataxonomic Analysis and Metabolomic Profiling of Fermentation Products. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, J.; Zhang, L.; Si, F.; Li, D.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C. Gastrointestinal digestion fate of Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide and its effect on intestinal flora: an in vitro digestion and fecal fermentation study. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yu, Q.; Ni, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, L. Effect of Agaricus bisporus Polysaccharides on Human Gut Microbiota during In Vitro Fermentation: An Integrative Analysis of Microbiome and Metabolome. Foods 2023, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priori, E.C.; Ratto, D.; De Luca, F.; Sandionigi, A.; Savino, E.; Giammello, F.; Romeo, M.; Brandalise, F.; Roda, E.; Rossi, P. Hericium erinaceus Extract Exerts Beneficial Effects on Gut–Neuroinflammaging–Cognitive Axis in Elderly Mice. Biology 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayimbila, F.; Siriwong, S.; Nakphaichit, M.; Keawsompong, S. In vitro gastrointestinal digestion of Lentinus squarrosulus powder and impact on human fecal microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, H.A.; Miller, A.N.; Pearce, C.J.; Oberlies, N.H. Fungal Identification Using Molecular Tools: A Primer for the Natural Products Research Community. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panya, M.; Kaewraemruaen, C.; Saenwang, P.; Pimboon, P. Evaluation of Prebiotic Potential of Crude Polysaccharides Extracted from Wild Lentinus polychrous and Lentinus squarrosulus and Their Application for a Formulation of a Novel Lyophilized Synbiotic. Foods 2024, 13, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuko, T.; Minami, A.; Iwasaki, N.; Majima, T.; Nishimura, S.-I.; Lee, Y.C. Carbohydrate analysis by a phenol–sulfuric acid method in microplate format. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 339, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thetsrimuang, C.; Khammuang, S.; Chiablaem, K.; Srisomsap, C.; Sarnthima, R. Antioxidant properties and cytotoxicity of crude polysaccharides from Lentinus polychrous Lév. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-Y.; Seguin, P.; Ahn, J.-K.; Kim, J.-J.; Chun, S.-C.; Kim, E.-H.; Seo, S.-H.; Kang, E.-Y.; Kim, S.-L.; Park, Y.-J.; et al. Phenolic Compound Concentration and Antioxidant Activities of Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms from Korea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7265–7270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A standardised staticin vitrodigestion method suitable for food – an international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Burillo, S.; Molino, S.; Navajas-Porras, B.; Valverde-Moya, Á.J.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; López-Maldonado, A.; Pastoriza, S.; Rufián-Henares, J.Á. An in vitro batch fermentation protocol for studying the contribution of food to gut microbiota composition and functionality. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 3186–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Ge, X.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Cheng, D.; Shao, R. Simulated digestion and fermentation in vitro by human gut microbiota of polysaccharides from Helicteres angustifolia L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; Mcmurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLOS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Tao, J.; Tian, G.; Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Cui, Q.; Geng, B.; et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome 2017, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabebe, E.; Robert, F.O.; Agbalalah, T.; Orubu, E.S.F. Microbial dysbiosis-induced obesity: role of gut microbiota in homoeostasis of energy metabolism. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Fang, L.; Lee, M.-H. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in promoting the development of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O.; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircana, A.; Framarin, L.; Leone, N.; Berrutti, M.; Castellino, F.; Parente, R.; De Michieli, F.; Paschetta, E.; Musso, G. Altered Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes: Just a Coincidence? Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2018, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Geng, Y.; Xu, T.; Zou, X.; Mao, R.; Pi, X.; Wu, W.; Huang, L.; Yang, K.; Zeng, X.; et al. Digestive Characteristics of Hericium erinaceus Polysaccharides and Their Positive Effects on Fecal Microbiota of Male and Female Volunteers During in vitro Fermentation. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 858585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mleczek, M.; Budka, A.; Siwulski, M.; Mleczek, P.; Budzyńska, S.; Proch, J.; Gąsecka, M.; Niedzielski, P.; Rzymski, P. A comparison of toxic and essential elements in edible wild and cultivated mushroom species. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Ham, E.-J.; Yoo, Y.-J.; Kim, E.-S.; Shim, K.-K.; Kim, M.-K.; Koo, C.-D. Effects of Aeration of Sawdust Cultivation Bags on Hyphal Growth of Lentinula edodes. Mycobiology 2012, 40, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeewanthi, L.A.M.N.; Ratnayake, K.; Rajapakse, P. Growth and Yield of Reishi Mushroom [Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst] in Different Sawdust Substrates. J. Food Agric. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Liang, C.-H.; Liang, Z.-C. Evaluation of Using Spent Mushroom Sawdust Wastes for Cultivation of Auricularia polytricha. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Manzi, H.P.; Su, L.; Liu, D.; Huang, X.; Long, D.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Y. The benefits of edible mushroom polysaccharides for health and their influence on gut microbiota: a review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1213010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, P.; Patra, A.; Barge, S.; Khan, M.R.; Mukherjee, A.K. Therapeutic Potential of Bioactive Compounds from Edible Mushrooms to Attenuate SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Some Complications of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). J. Fungi 2023, 9, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Fanigliulo, A.; Crescenzi, A.; Liuzzi, G.M.; Rossano, R. Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides from the Edible Mushroom Pleurotus eryngii. Molecules 2023, 28, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, E.; Tel-Çayan, G.; Çayan, F.; Altınok, B.Y.; Aktaş, S. Characterization of Polysaccharide Extracts of Four Edible Mushrooms and Determination of In Vitro Antioxidant, Enzyme Inhibition and Anticancer Activities. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25887–25901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Du, H.; Hu, Q.; Yang, W.; Pei, F.; Xiao, H. Health benefits of edible mushroom polysaccharides and associated gut microbiota regulation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 6646–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Gan, J.; Yan, B.; Wang, P.; Wu, H.; Huang, C. Polysaccharides from Russula: a review on extraction, purification, and bioactivities. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1406817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangthong, S.; Pintathong, P.; Pongsua, P.; Jirarat, A.; Chaiwut, P. Polysaccharides from Volvariella volvacea Mushroom: Extraction, Biological Activities and Cosmetic Efficacy. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.S.E.; Lukasiewicz, M. The Optimization of the Hot Water Extraction of the Polysaccharide-Rich Fraction from Agaricus bisporus. Molecules 2024, 29, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butkhup, L.; Samappito, W.; Jorjong, S. Evaluation of bioactivities and phenolic contents of wild edible mushrooms from northeastern Thailand. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Ge, X.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Cheng, D.; Shao, R. Simulated digestion and fermentation in vitro by human gut microbiota of polysaccharides from Helicteres angustifolia L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Di, Q.; Liang, T.; Zhou, N.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Z.; Luo, Y.; Shaker, M. Effects of in vitro simulated digestion and fecal fermentation of polysaccharides from straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) on its physicochemical properties and human gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ke, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Hu, B.; Liu, A.; Luo, Q.; Wu, W. In vitro saliva-gastrointestinal digestion and fecal fermentation of Oudemansiella radicata polysaccharides reveal its digestion profile and effect on the modulation of the gut microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 251, 117041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarza, P.; Yilmaz, P.; Pruesse, E.; Glöckner, F.O.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.-H.; Whitman, W.B.; Euzéby, J.; Amann, R.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, J.L.; Portik, D.M.; Driscoll, M.D.; Jackson, E.; Chakraborty, S.; Gratalo, D.; Ashby, M.; Valladares, R. Finding the right fit: evaluation of short-read and long-read sequencing approaches to maximize the utility of clinical microbiome data. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Mercado, A.I.; Plaza-Diaz, J. Dietary Polysaccharides as Modulators of the Gut Microbiota Ecosystem: An Update on Their Impact on Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Di, Q.; Liang, T.; Zhou, N.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Z.; Luo, Y.; Shaker, M. Effects of in vitro simulated digestion and fecal fermentation of polysaccharides from straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) on its physicochemical properties and human gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Kong, K.; Li, C.; Fang, Z.; Hu, B.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Wu, W.; et al. Effect of in vitro simulated digestion and fecal fermentation on Boletus auripes polysaccharide characteristics and intestinal flora. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 126461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Tillotson, G.; MacKenzie, T.N.; Warren, C.A.; Wexler, H.M.; Goldstein, E.J. Bacteroides and related species: The keystone taxa of the human gut microbiota. Anaerobe 2024, 85, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnode, M.L.; Beller, Z.W.; Han, N.D.; Cheng, J.; Peters, S.L.; Terrapon, N.; Henrissat, B.; Le Gall, S.; Saulnier, L.; Hayashi, D.K.; et al. Interspecies Competition Impacts Targeted Manipulation of Human Gut Bacteria by Fiber-Derived Glycans. Cell 2019, 179, 59–73.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhou, W.; Chen, G.; Yi, W.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, X. The Utilization by Bacteroides spp. of a Purified Polysaccharide from Fuzhuan Brick Tea. Foods 2024, 13, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Zheng, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Xie, C.; Zuo, W.; Xia, X.; Sun, L.; et al. Selective utilization of medicinal polysaccharides by human gut Bacteroides and Parabacteroides species. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Xu, X.; Lei, P.; Xu, H.; Li, S. In vitro digestion and fecal fermentation of Tremella fuciformis exopolysaccharides from basidiospore-derived submerged fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Que, Y.; Liang, F.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; et al. Physicochemical properties and fermentation characteristics of a novel polysaccharide degraded from Flammulina velutipes residues polysaccharide. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.L.; Kei, N.; Yang, F.; Lauw, S.; Chan, P.L.; Chen, L.; Cheung, P.C.K. In Vitro Fermentation Characteristics of Fungal Polysaccharides Derived from Wolfiporia cocos and Their Effect on Human Fecal Microbiota. Foods 2023, 12, 4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Sun, H.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Yin, A.; Yin, A.; Hu, J.; Hu, J.; et al. Gut commensalParabacteroides distasonisalleviates inflammatory arthritis. Gut 2023, 72, 1664–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kverka, M.; Zakostelska, Z.; Klimesova, K.; Sokol, D.; Hudcovic, T.; Hrncir, T.; Rossmann, P.; Mrazek, J.; Kopecny, J.; Verdu, E.F.; et al. Oral administration of Parabacteroides distasonis antigens attenuates experimental murine colitis through modulation of immunity and microbiota composition. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010, 163, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liao, M.; Zhou, N.; Bao, L.; Ma, K.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; et al. Parabacteroides distasonis Alleviates Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunctions via Production of Succinate and Secondary Bile Acids. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 222–235.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Ye, H.; Hu, B.; Zeng, X. Influences of structures of galactooligosaccharides and fructooligosaccharides on the fermentation in vitro by human intestinal microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 13, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 23, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Kounatidis, D.; Tsilingiris, D.; Panagopoulos, F.; Christodoulatos, G.S.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. The Role of Next-Generation Probiotics in Obesity and Obesity-Associated Disorders: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Pan, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, H. Fusobacterium nucleatum in tumors: from tumorigenesis to tumor metastasis and tumor resistance. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2024, 25, 2306676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woting, A.; Blaut, M. The Intestinal Microbiota in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Son, D.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, K.H.; Seo, K.W.; Jung, K.; Park, S.J.; Lim, S.; Kim, J.H. Association between the Blautia/Bacteroides Ratio and Altered Body Mass Index after Bariatric Surgery. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 37, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemicals | Simulated digestive solutions and their final concentration (mmol/l) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| simulated salivary fluid (SSF) |

simulated gastric fluid (SGF) | simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) | |

| KCl | 15.10 | 6.90 | 6.80 |

| KH2PO4 | 3.70 | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| NaHCO3 | 13.60 | 25.00 | 85.00 |

| NaCl | - | 47.20 | 38.40 |

| MgCl2(H2O)6 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.33 |

| (NH4)2CO3 | 0.06 | 0.50 | - |

| CaCl2(H2O) | 1.50 | 0.15 | 0.60 |

| Final pH | 7.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 |

| Treatments | Components | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermentation mediuma | 32% (w/v) Fecal slurry | Supernatant from the simulation of human gastrointestinal digestion | Solid Residue from the simulation of human gastrointestinal digestion | |

| Crude polysaccharide LS | 7.5 ml | 2 ml | 350 µl | 0.5 g |

| Crude polysaccharide LP | 7.5 ml | 2 ml | 350 µl | 0.5 g |

| GOS | 7.5 ml | 2 ml | 0.5 g GOS was dissolved in 1.0 ml sterile water and filtered through a 0.2 µm syringe filterb | |

| mConA | 7.5 ml | 2 ml | 0.85 ml Milli-Q water | |

| mConB | 7.5 ml | 2 ml | 350 µl from tubeAc |

0.5 g from tubeAc |

| Crude Polysaccharide | Yielda (%) |

Total Carbohydrate (mg/g) |

Reducing Sugar (mg/g) |

Polysaccharide (mg/g) |

Total Protein (mg/g) |

Phenolic compound (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS | 7.68±0.04 | 462.22 ± 28.70 | 83.82±4.32 | 378.41 ± 29.26 | 19.08±3.15 | 34.38±4.53 |

| LP | 9.29±0.03 | 509.74 ± 27.08 | 87.09±3.47 | 422.65 ± 25.84 | 28.46±1.32 | 67.72±2.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).