1. Introduction

Microorganisms produce exopolysaccharides (EPS) to adapt to their environment [

1,

2]. In general, pathogenic microorganisms use EPS to form biofilms to attach extracellular cells and protect against environmental factors [

3,

4,

5]. In addition, acetic acid bacteria (AAB) form biofilms with β-glucan structures similar to cellulose, whereas lactic acid bacteria (LAB) form biofilms with ⍺-glucans [

6,

7].

Dextrans are a major EPS produced by LAB and are homopolymers of D-glucopyranosyl residues that are primarily coupled by α-1,6 linkages and variable amounts of α-1,4-, α-1,3-, and α-1,2 linkages [

6,

8,

9,

10]. Dextran is mainly synthesized from sucrose by

Leuconostoc spp. via transglucosylation by dextransucrases (DSases; E.C. 2.4.1.5) that produce dextran containing a high percentage of consecutive α-1,6 linkages and a low percentage of α-1,3 linkages [

11,

12]. In 1949, [

13] showed that polysaccharides from Acetobacter capsulatum (i.e.,

Gluconobacter oxydans) can produce ropy beer, similar to polysaccharides from

Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Additionally, [

14,

15] reported that dextran dextrinase (DDase; E.C. 2.4.1.2) derived from

G. oxydans can convert dextran from maltodextrin (MD) in contrast to DSase. The structure of dextran synthesized by

G. oxydans DDase harbored α-1,4 branches and α-1,4 linkages in α-1,6 glucosyl linear chains [

16,

17]. In particular, DDase has an advantage over DSase in the dextran production process because DDase does not produce monosaccharide by-products such as fructose [

18,

19].

Dextran is a biopolymer isolated from microorganisms, which use dextran to form parts of their viscous extracellular matrix [

20]. Dextrans are industrially useful polymers that do not exist in nature and have demonstrated multifunctional applications in the biochemical (e.g., molecular sieves for chromatography) and pharmaceutical (e.g., blood plasma substitute) industries [

9,

18]. Moreover, these microbial polysaccharides can exert distinct functions depending on their molecular weight (MW), the targeted saccharide substrate, the position of linkages, and the presence or absence of branched bonds [

21]. Given their unique structural characteristics, dextrans from

Gluconobacter spp. have been used in the food industry as sources of dietary fiber, cryostabilizers, fat substitutes, and low-calorie bulking agents for sweeteners [

20]. Furthermore, dextrans have been applied broadly in other industries, including as components for cosmetics [

22], dietary fiber due to its low digestibility by intestinal enzymes [

48], in high-viscosity gums [

17], and as food additives [

23].

Numerous studies have reported the production and characteristics of dextran derived from heterogeneous expression of

G. oxydans DDase [

12,

15,

16,

24,

25]. However, use of this enzyme as a food ingredient requires approval from government food agencies. Additionally, the production of biomaterials via fermentation of AAB demonstrating enzyme activity might be affected by various factors, including medium composition, substrate concentration, and culture temperature. Furthermore, previous studies report increased productivity of

G. oxydans in bioreactors owing to their lower biomass [

26,

27]. Nevertheless, there is a knowledge gap associated with the establishment of optimal culture conditions for efficient dextran production, especially in regard to the optimal pH employed during semi-continuous fermenter operations.

Therefore, in this study, we analyzed the rheological characteristics of the culture media and physiochemical characteristics of G. oxydans dextran synthesized in dextrin media at different pH values. These results provide fundamental information that can be applied to generate functional carbohydrates as food raw materials via the bioconversion process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Strains and Preparation of Stock Cultures

G. oxydans KACC 19357 (ATCC 11894) was obtained from the Korean Agricultural Culture Collection (KACC, Suwon, Korea). The bacteria were grown at 30℃ in acetic acid bacterium (AAB) medium containing 5 g bactopeptone, 5 g yeast extract, 5 g D-glucose, 1 g MgSO4∙7H2O per liter at a pH range of 6.6 to 7.0. The organisms were initially cultured on AAB agar medium at 30℃ for 72 h and then inoculated into liquid medium at 30℃ for 24 h. At the end of the incubation time, stock cultures were prepared by dispensing 1 mL of the inoculum into sterile 2 mL cryovials containing 0.5 mL glycerol. The resulting suspensions were mixed and stored at −70℃.

2.2. Cultivation of the Jar Fermenter

Dextran production by

G. oxydans was conducted in a 5.0-L jar fermenter (Kobiotech, Incheon, Korea). Jar fermenter cultures were performed as follows. The strain was precultivated for 20 h to an optical density at 600 nm (OD

600) of 0.5 in a 250-mL flask containing 60 mL AAB medium at 30℃ with shaking at 200 rpm. The media from the seed culture was then transferred to media in the 2.5-L jar fermenter media, the composition of which was described previously [

28,

29,

30]. The culture conditions, including dextrin composition, injection time, and shaking speed, were established and slightly modified in several preliminary experiments [

31]. The final culture medium comprised 1.2 L of media comprising 6 g yeast extract, 0.6 g KH

2PO

4, 0.6 g K

2HPO

4, 6 g D-glucose, 1.2 g MgSO

4∙7H

2O, 60 g MD [dextrose-equivalent; Serimfood, Buchoen, Korea), and 2% (v/v) glycerol. Additionally, we manually added substrate solution (60 g MD, 2 g MgSO

4∙7H

2O, and 100 mL distilled water) at 50-mL increments at 12 h and 24 h of culture. The pH of the culture was controlled by automated addition of 10% (v/v) NaOH and 50% (v/v) glycerol solution. Foam content was automatically controlled by addition of 0.05 % (v/v) antifoam solution (Antifoam 204; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A pH of 4.5 is considered optimal for DDase activity, and a pH of 5.0 considered optimal for cell-mass proliferation and DDase stability following isolation from acetic acid bacteria [

15,

32]. According to previous results showing that pH affects G.

oxydans growth [

33], we compared the culture characteristics of

G. oxydans under different pH values by employing three cultures with different pH status (Jp-UC, jar fermentor pH uncontrolled; Jp-4.5, pH controlled to 4.5; and Jp-5.0, pH controlled to 5.0) (

Table 1). The OD

600 of the cultures was determined using a 1mL cuvette in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 3500 UV-Vis; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Samples were appropriately diluted in order to maintain the OD

600 value between 0.2 and 0.8.

2.3. Analysis of Rheological Properties

We performed rheological measurements to describe the flow behaviors of the culture medium while using 10% and 20% dextran solution (dextran 40; Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) as positive controls. Flow sweep test was conducted using a rheometer (Discovery HR-1; TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) interfaced with TRIOS software (TA Instruments). All experiments were performed using Peltier plate geometry (diameter: 40 mm) and at 25℃. The viscosity was measured as a function of shear rate in the range of 0.1 s−1 to 300 s−1, with apparent viscosity expressed at a shear rate of 100 s-1.

2.4. Dextran Isolation

The fermented media were centrifuged in 7119 ×g for 10 min at 4℃ to remove cells, after which dextran was precipitated from the culture supernatant following the addition of nine volumes of ice-cold absolute ethanol and centrifuged after incubation at −80℃ for 2 h. The precipitate was freeze dried, with the powder form used for analysis. The yield was expressed as the ratio (%) of the amount of polymer (dextran) obtained divided by the amount of substrate MD used.

2.5. Gel permeation Chromatography (GPC) Analysis

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was used to analyze the molecular weight distribution of the polysaccharides produced. The culture solution was treated with 90% (v/v) cold ethanol to precipitate the polysaccharides, which were then recovered and freeze-dried. The sample (10 mg/mL) was dissolved in distilled water, filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter (13 mm, 0.22 μm, NYLON, Thermo Fisher Scientific Co.), and used for analysis. An HPLC system (Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a TSK gel G3000PW column (7.8 mm × 30 cm, Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) was used for separation. The column was maintained at 40°C, with a sample injection volume of 10 μL and distilled water as the solvent. Molecular weight was determined by elution time, using glucose, maltose, and pullulan standards from Sigma-Aldrich as reference substances.

2.6. NMR Analysis

The ratio of ⍺-1,4 and ⍺-1,6 glycosidic bonds in high molecular weight polysaccharides produced under different culture conditions was analyzed using 1H-NMR spectroscopy (500 MHz FT-NMR, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Polysaccharides were recovered by ethanol precipitation from the culture supernatant, and the freeze-dried sample (20 mg/ml) was dissolved in deuterium oxide (D2O). The solution was incubated at 45°C for 20 minutes before performing the 1H-NMR analysis.

2.7. Hydrolysis Properties of EPS by Mammalian Mucosal α-Glucosidase

To investigate the digestibility characteristics of the culture medium, the glucose content released by the action of the digestive enzyme RIAP (rat intestinal acetone powder), a mammalian α-glucosidase, was measured using a modified method from Um et al. [

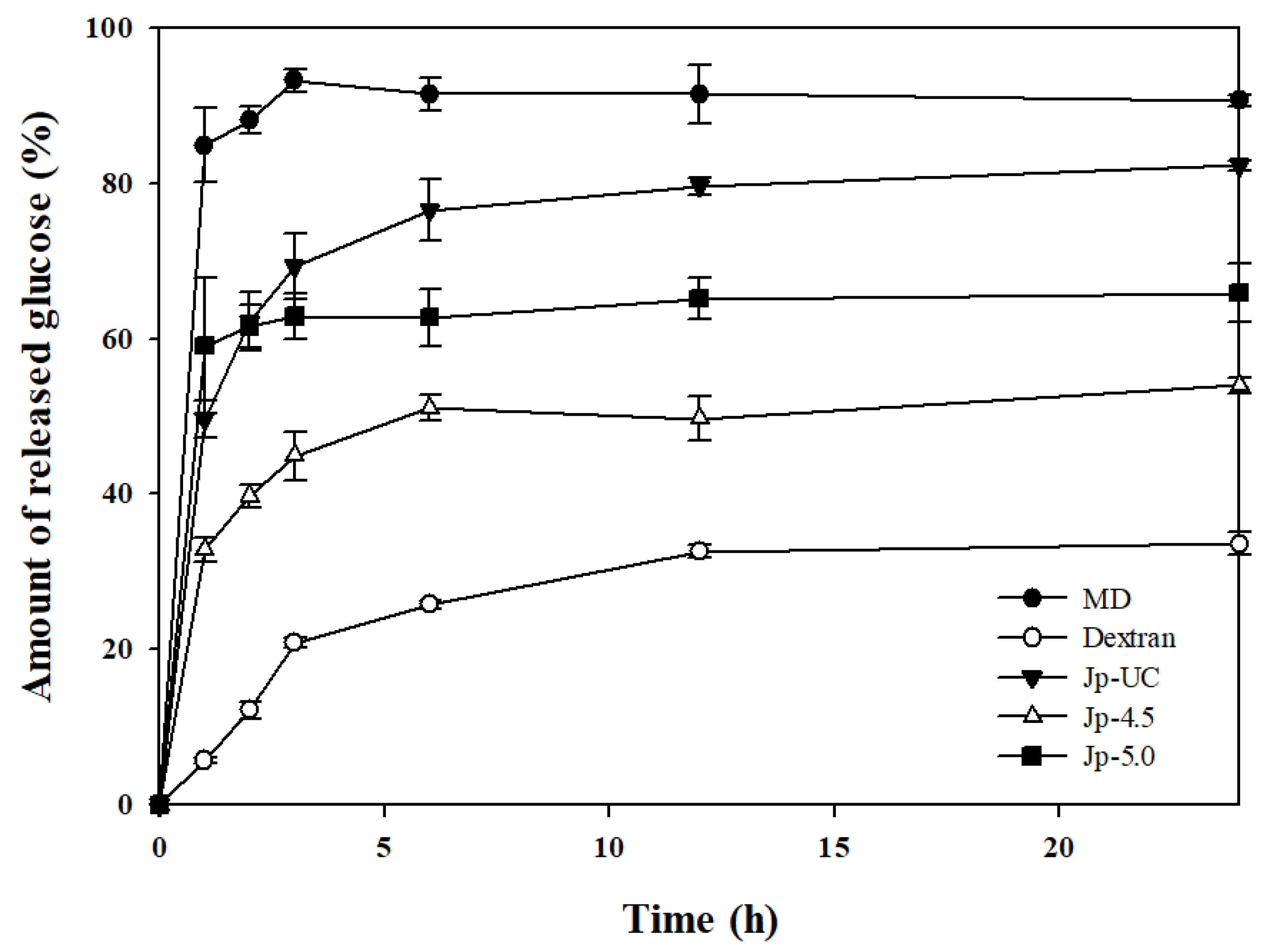

34]. A freeze-dried polymer sample, recovered by ethanol precipitation from the culture medium, was dissolved at a concentration of 0.1% (w/v) in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 6.7 mM NaCl and 0.2% sodium azide. This solution was then incubated with RIAP (10 mg/mL, w/v) at 37°C. Ampicillin (0.0005%, w/v) was added to prevent microbial growth during the reaction. Substrate-enzyme mixtures were collected at intervals of 0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours, with enzyme activity terminated by heating to 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 7,119 × g for 5 minutes. The glucose released by enzymatic hydrolysis was quantified using the D-Glucose Assay Kit (Megazyme Co., Bray, Wicklow, Ireland), with maltodextrin and dextran included as controls for comparative analysis.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean 土 standard deviation for each experiment. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (v27.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) along with one-way analysis of variance and Duncan’s multiple range tests. The results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Growth Properties of G. oxydans

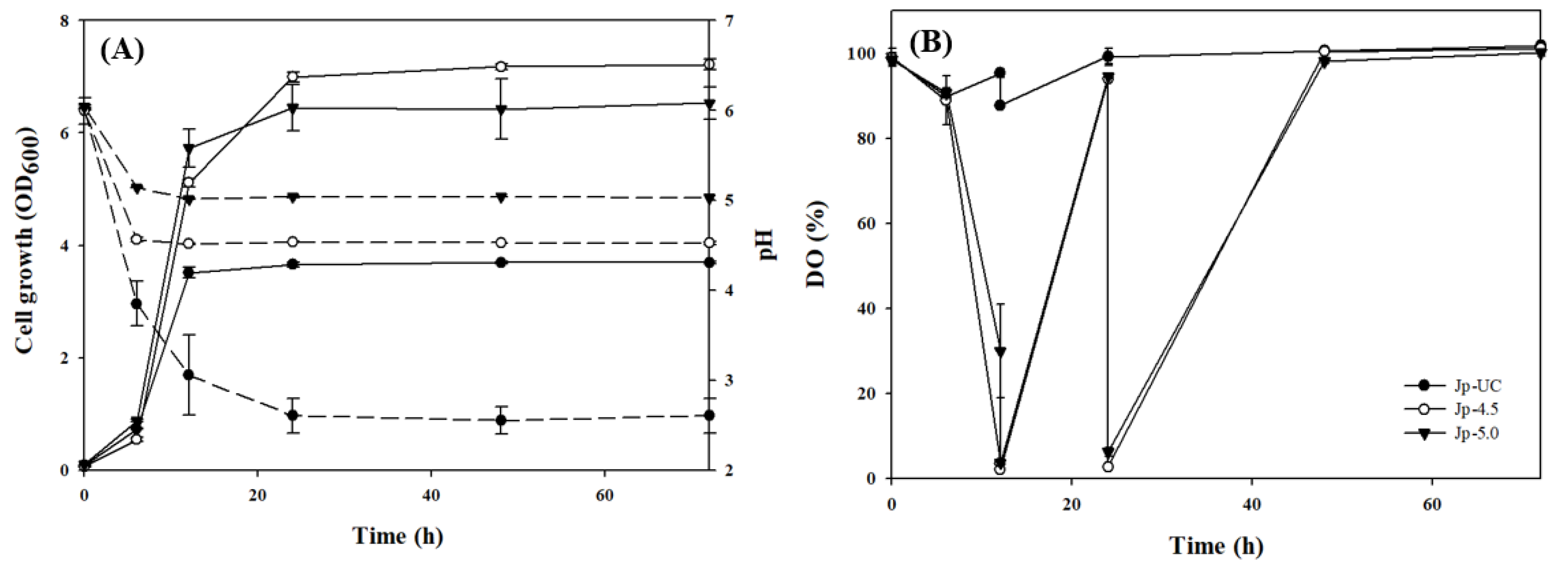

The growth characteristics of the three different pH condition culture groups of

G. oxydans are shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. The Jp-UC group, in the absence of NaOH-solution feeding, the pH rapidly decreased to 4.0 after 6 hours and to 3.0 after 12 hours of growth, eventually stabilizing at pH 2.5 for the remainder of the 72-hour incubation period.

G. oxydans oxidizes and metabolizes glycerol into acidic substances in medium [

35], resulting in acidification of the medium and subsequent hampering of growth at pH levels <3.5 by completely inhibiting the activities of enzymes in the pentose phosphate pathway [

20]. The optimal pH for

G. oxydans growth lies between 4.0 and 5.0, which promotes oxidation of acetaldehyde to acetate and shifts the culture medium to lower pH values [

36]. After adjusting the medium pH with NaOH, the Jp-4.5 and Jp-5.0 groups maintained stable pH values of 4.5 and 5.0, respectively. These conditions supported increased growth, reflected in OD

600 values of 7.2 and 6.5 for Jp-4.5 and Jp-5.0, respectively. This resulted in a 1.8- to 1.9-fold increase in cell mass compared to the Jp-UC group, which had an OD

600 of 3.7. This was in agrement with a previous study, which reported that

G. oxydans showed optimal growth at a pH range of 4.0 to 6.0 [

32,

37].

Additionally, we observed initial decreases in dissolved oxygen (DO) content from 6 to 12 hours, followed by gradual increases to a plateau after 24 hours across all experimental groups. In each case, cells exhibited an exponential growth phase between 6 and 24 hours, likely due to enhanced growth facilitated by the utilization of available oxygen. Moreover, the observed patterns of decreased DO (Jp-4.5 > Jp-5.0 > Jp-UC) and increased growth (Jp-4.5 > Jp-5.0 > Jp-UC) confirmed the expected correlation between DO and growth rate in these obligate aerobic bacteria. Dextran biosynthesis would be possible in cultures grown in maltodextrin-containing media due to the DDase activity of

G. Oxydans [

15]. Given that the enzyme is pH-sensitive, a distinct patterns in dextran production may emerge, potentially leading to differences in the charateristics or composition of the resulting bioconversion products. Yamamoto et al. [

15] reported that the optimal and stable pH of DDase ranges from 4.0 to 4.5 and 3.2 to 5.0, respectively.

3.2. Physicochemical Properties of EPS (Dextran) Produced in G.oxydans Culture Media

3.2.1. Flow Behavior

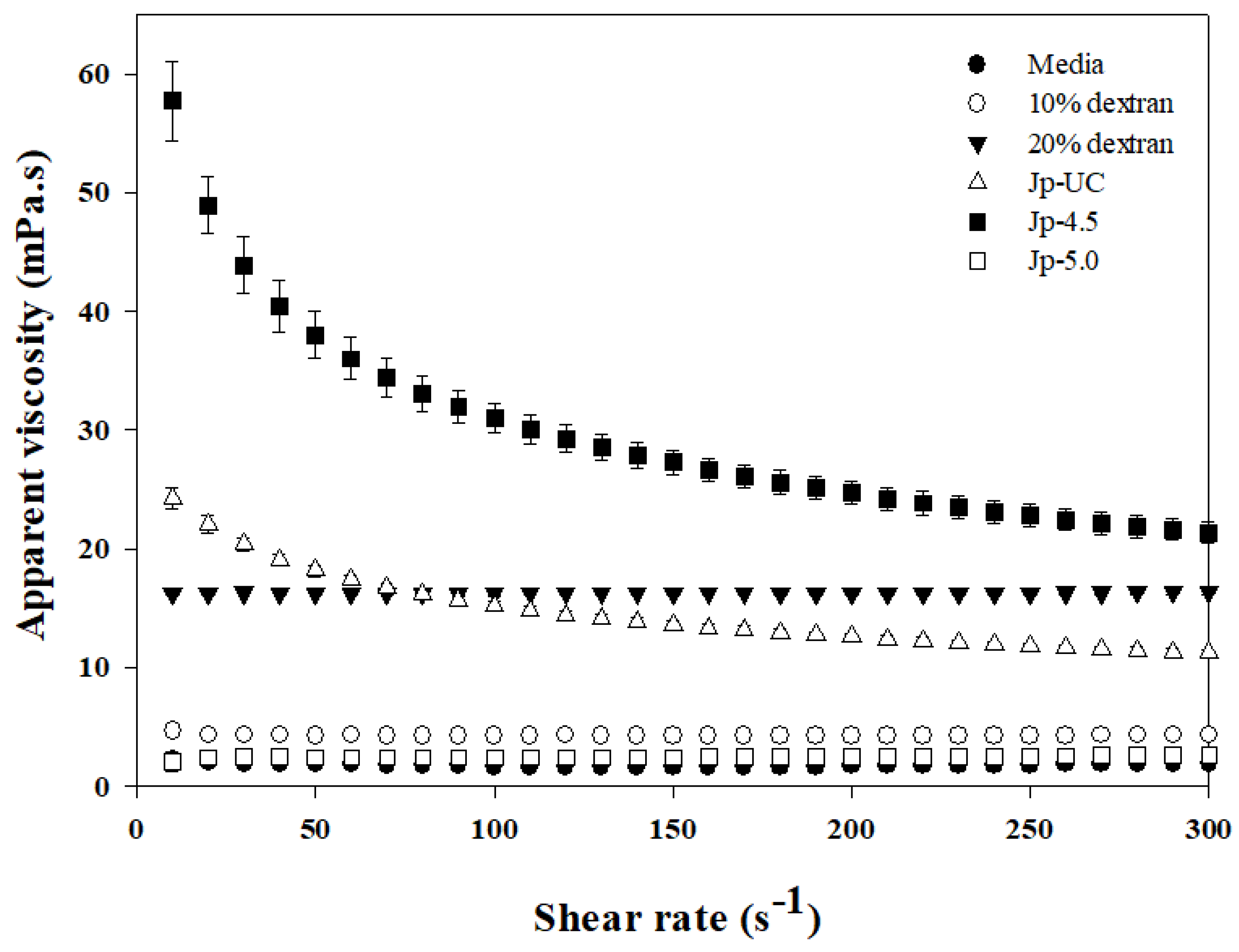

The apparent viscosity values presented in

Table 2 reveal distinict differences among the culture media. Jp-4.5 exhibited the highest viscosity (30.99 mPa·s), even surpassing that of a 20% dextran solution (16.17 mPa·s), suggesting significant polymer formation. The Jp-UC medium showed an intermediate viscosity (15.2 mPa·s), comparable to a 10% dextran solution, while Jp-5.0 had a considerably lower viscosity (2.39 mPa·s), comparable to the initial medium, implying limited polymer synthesis at pH 5.0.

On the other hand,

Figure 2 shows the rheological properties of

Gluconobacter oxydans culture media under different pH conditions, where the Jp-4.5 medium demonstrated non-Newtonian, shear-thinning behavior, with high shear stress at low shear rates that gradually decreased as shear rates increased, while the Jp-5.0 and Jp-Uc media exhibited Newtonian fluid behavior. Zarour et al. [

38] reported that dextran solutions from five lactic acid bacteria (LAB) sources displayed viscosity behaviors dependent on concentration and shear rate, with low concentrations maintaining Newtonian, shear rate-independent viscosity similar to certain commercial dextrans, while higher concentrations showed a viscosity decrease with increasing shear rate, indicating non-Newtonian, pseudoplastic behavior. Similarly, Xu et al. [

39] found that a high molecular weight dextran solution (5.223 x 10

5) at 30 wt% also displayed pseudoplastic properties, likely due to hydrodynamic forces disrupting structural entanglements among α-glucan chains in solution under shear [

39]. These suggest that the Jp-4.5 medium likely contains a higher dextran concentration than the Jp-5 and JU media, which may account for its distinctive shear-thinning behavior.

These findings partially align with those of [

15,

40], who reported DDase stability between pH 3.2 and 5.5 and optimal

G. oxydans growth at pH 5.5. However, under the controlled pH conditions of the jar fermentor used here, pH 5.0 did not support effective dextran synthesis, as reflected in the low viscosity in Jp-5.0. While pH adjustments between 4.5 and 5.0 enhanced

G. oxydans growth by reducing medium oxidation, our results demonstrate that a narrower pH range, closer to 4.5, is required for optimal dextran production. Thus, pH 4.5 appears to balance both growth and dextran biosynthesis, underscoring the importance of precise pH control to maximize EPS yield.

3.2.2. Molecular Weight Distribution

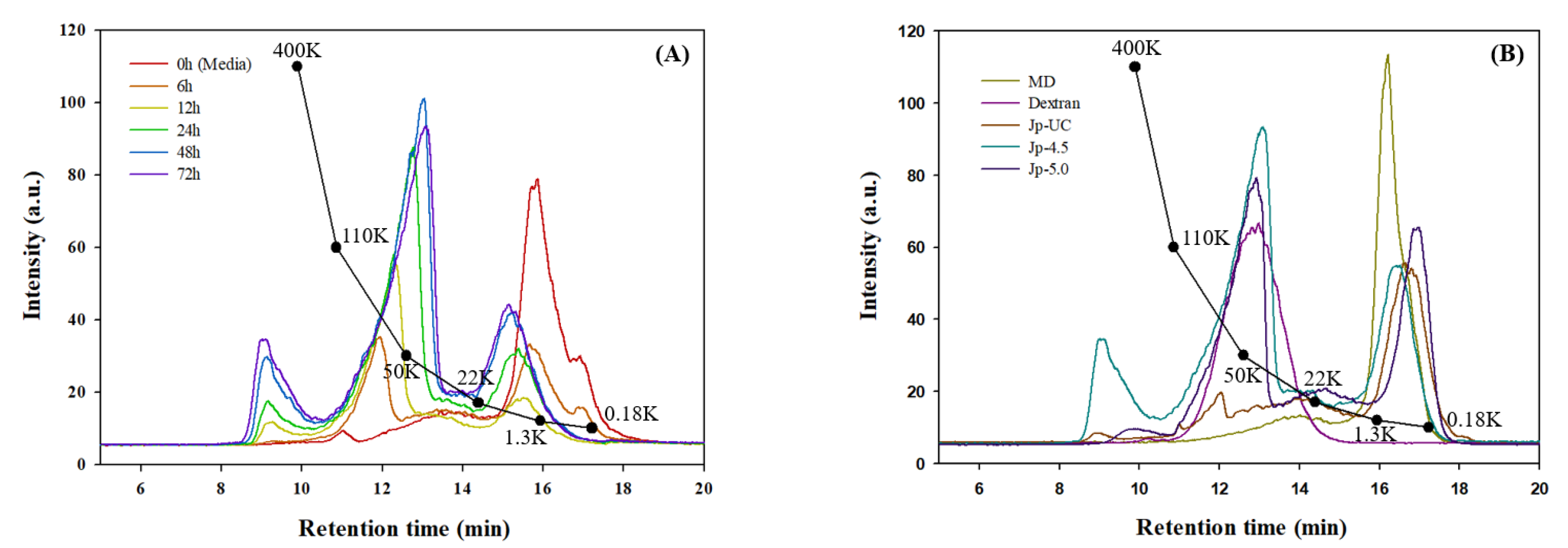

Figure 3 and

Table 3 show the molecular weight (MW) distribution of EPS and dextran synthesized through

G. oxydans culture, as analyzed by GPC. In

Figure 3A, the decrease in substrate (consumption pattern) and the formation of products, as well as their size distribution over time, are presented. At 0 hours (initial medium), the peak eluting at 15-18 minutes corresponds to the maltodextrin component added as a substrate, with a peak molecular weight (Mp) of 1,284 Da, indicating that it is a maltooligosaccharide with a degree of polymerization (DP) of 7-8, composed primarily of glucose. It can be observed that the distribution of molecular weights extends to components above 22 kDa. This peak rapidly decreased over the course of 6 and 12 hours, suggesting that as the

G. oxydans culture progressed, lower molecular weight substances were consumed, indicating efficient utilization of carbon sources and sugar-transferring substrates. At 12 hours, the peak at 16 minutes was significantly lower, indicating that maltodextrin, which had been depleted at the appropriate time, was likely injected as a feeding solution. At 12 hours, the supernatant of the culture showed significant differences in peak patterns from the initial medium. As the culture progressed, the peak at 12-14 minutes corresponding to a 50 kDa molecular weight increased, suggesting effective EPS and polysaccharide production. The molecular weight distribution patterns at 48 and 72 hours were similar, with the peaks for low molecular weight substances slightly shifting to the left compared to the initial medium, indicating the use of maltodextrin chains as acceptors and the transfer of glucose molecules, leading to an increase in the molecular weight of the products.

In

Figure 3B, EPS from the culture supernatants at 72 hours under different pH conditions were recovered by ethanol precipitation and compared by preparing 1% (w/v) aqueous solutions of the dried EPS. The Mp of the Jp-UC sample was significantly smaller than those of Jp-4.5 and Jp-5.0, which were 44,267 Da and 50,722 Da, respectively. This result was consistent with the lower peak observed between 12-14 minutes in the chromatogram. Notably,

G. oxydans cultured at pH 5.0 showed a decrease in glucose levels without a significant increase in either maltooligosaccharide synthesis or high-molecular-weight substance production (

Figure 3B). In evaluating DDase activity based on substrate specificity, Yamamoto et al. [

15] reported that 30.2% and 57.6% of dextran was synthesized from maltohexaose and short-chain amylose, respectively. Additionally, other studies have indicated that dextran synthesized by DDase exhibits a broad molecular weight distribution, ranging from 6.6 kDa to 96.8 kDa [

9,

24]. A recent study [

41] reported conversion into isomalto-megalosaccharides, which differ slightly from dextran, with similar-sized products appearing between 6 kDa and 1.3 kDa in the chromatogram (

Figure 3B). Similarly, the polysaccharide composition and yield biotransformed by

G. oxydans, recovered from media cultured under varying pH conditions, exhibited diverse compositions.

3.2.3. 1H-NMR Analysis

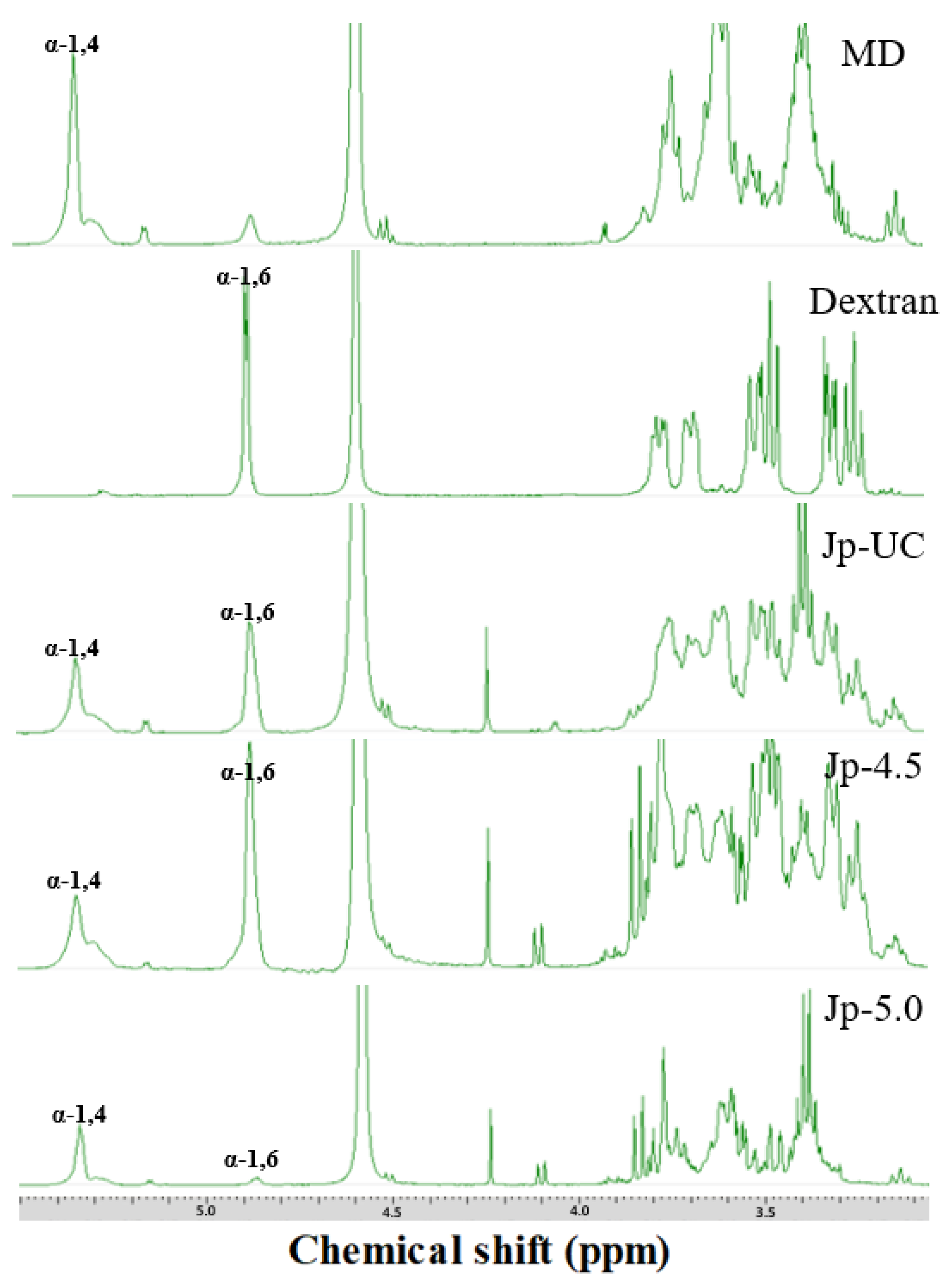

Figure 4 shows the

1H-NMR spectrum of dextran isolated from

G. oxydans culture media confirming the formation of dextran from dextrin through chemical shifts at 5.3 ppm and 4.9 ppm, which correspond to the formation of an α-(1→4) and an α-(1→6) linkage (glycosidic bonds in the polymer), respectively [

42]. Consistent with our results, Cheetham et al. [

43] also observed the anomeric proton resonance for the α-(1→6) D-glycosyl residue at approximately 4.94 ppm in their studies on Dextran T10 and B-512. In our analysis of polysaccharides from each experimental group (Jp-UC, Jp-4.5, and Jp-5.0), the presence of a α-(1→6) linkage was confirmed by specific peak absent in MD alone (

Figure 4). Among the groups, the estimated linkage ratio [α-(1→4) to α-(1→6)] in the polysaccharides from the Jp-4.5 was 1:2.84; which was 1.5- and 16-fold higher than that in Jp-UC (1:1.84) and Jp-5.0 (1:0.17), as showen in

Table 4. These findings indicated that DDase activity was affected by culture pH, with maximum dextran synthesis observed at pH 4.5 but not at pH 5.0 and suggesting that glycosyltransfer activity might be hindered at pH 5.

3.3. Digestibility of EPS (Dextran) by Mammalian α-Glucosidases

To evaluate the digestibility of synthesized EPS into glucose via bioconversion by mammalian α-glucosidase under different pH conditions, the reaction with digestive enzymes derived from rat small intestine tissue was measured for 24 hours (

Figure 5). α-glucosidase is an enzyme that breaks down polysaccharides and disaccharides into monosaccharides in the small intestine; its activity and pattern of action are known to vary depending on the evolutionary level of the organism [

34,

44]. The small intestinal mucosa contains a complex of enzymes, maltase-glucoamylase (MGAM) (EC 3.2.1.20 and 3.2.1.3) and sucrose-isomaltase (SI) (EC 3.2.148 and 3.2.10), which have different actions to digest carbohydrates and hydrolyse them to free glucose [

45]. Mammalian digestive enzymes derived from rat intestine were used for these measurements instead of AMG, a microbial enzyme commonly utilized in digestion studies, because they closely mimic digestion in the human body [

46].

We found that 84.8% of the maltodextrin used as a substrate was hydrolyzed to glucose within the first hour of digestion, compared to 49.6% and 59.1% for Jp-UC and Jp-5.0, respectively, and only 32.8% for Jp-4.5. Over a total of 24 hours, Jp-UC released 82.3% glucose, showing a similar level of hydrolysis to that of maltodextrin (90.6%). In contrast, Jp-4.5 exhibited a total glucose release of only 54.0%, indicating a clear pattern of slow glucose decomposition and highlighting significant differences in EPS digestibility depending on the pH conditions during culture. This finding aligns with the glycosidic linkage ratios shown in

Figure 4; maintaining the pH at 4.5 during

G. oxydans fermentation led to active dextrin-to-dextran converting enzyme (DDase) activity, transforming the substrate into dextran, an α-1,6 glucan. Meanwhile, commercial dextran derived from sucrose, used as a positive control for the digestion reaction, showed an initial glucose release of 5.7%, increasing to 33.6% by the end of the 24-hour reaction.

Maltodextrin, an α-1,4 glucan, is hydrolyzed by amylase in the body to produce maltose units. These maltose units are either directly absorbed by the intestinal epithelium or further broken down by maltase to release glucose, resulting in a rapid rise in blood glucose levels [

47,

48]. However, studies have shown that α-1,6 bonds are hydrolyzed more slowly than α-1,4 bonds, which reduces in vitro digestibility [

45]. Thus, increasing the number of α-1,6 bonds while decreasing α-1,4 bonds is significantly associated with improved slow digestibility, and recent research has focused on increasing the proportion of α-1,6 bonds [

44,

49]. This reduction in the rate of initial glucose breakdown is crucial as it helps prevent blood glucose spikes, thereby suppressing insulin secretion and potentially lowering the metabolic load on organs involved in digestion [

50]. Thus, cultured solutions synthesized through

G. oxydans enzyme reaction and their product by ethanol precipitated under specific pH conditions may serve as functional ingredients to prevent blood sugar spikes and regulate postprandial glycemic response by promoting slow digestion.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that appropriate pH adjustments are critical in optimizing G. oxydans growth and dextran production, with pH 4.5 proving particularly effective compared to uncontrolled pH and pH 5.0. The highest apparent viscosity (30.99 mPa∙s) and α-1,6 linkage ratio observed at pH 4.5 indicate enhanced enzyme activity and efficient dextran synthesis. Molecular size distribution analysis confirmed that dextran molecular weights ranged from 1.3 × 10³ Da to 5.1 × 10⁴ Da, with a broader size range under the tested pH conditions. Moreover, the Jp-4.5 condition exhibited the slowest glucose release, suggesting the production of α-1,6 glucan with slow-digesting characteristics. Therefore, dextran bio-converted from dextrin by G. oxydans has potential as a functional carbohydrate ingredient to help manage postprandial glycemic response.

Author Contributions

S.M.B.: Conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis; investigation, data curation; writing—original draft. L.S.C.: Writing, methodology, review and editing, supervision Y.S.S.: Data curation. J.H.J.: Conceptualization, methodology. S.L.: Methodology. J.Y.P.: Visualization. B.R.P.: Conceptualization, writing—original draft and editing, resources, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Program for Agricultural Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ01417801), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Nicolaus, B.; Kambourova, M.; Oner, E.T. Exopolysaccharides from extremophiles: from fundamentals to biotechnology. Environ. Technol. 2010, 31, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, I.W. Surface carbohydrates of the prokaryotic cell. (No Title). 1977.

- Donot, F.; Fontana, A.; Baccou, J.C.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Microbial exopolysaccharides: main examples of synthesis, excretion, genetics and extraction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.; Madamwar, D. Partial characterization of extracellular polysaccharides from cyanobacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1822–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kant, C.; Yadav, R.K.; Reddy, Y.P.; Abraham, G. Cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides: composition, biosynthesis, and biotechnological applications. In Cyanobacteria: From Basic Science to Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bounaix, M.S.; Robert, H.; Gabriel, V.; Morel, S.; Remaud-Siméon, M.; Gabriel, B. Characterization of dextran-producing Weissella strains isolated from sourdoughs and evidence of constitutive dextransucrase expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 311, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Hugenholtz, J.; Zoon, P. An overview of the functionality of exopolysaccharides produced by lactic acid bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 2002, 12, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besrour-Aouam, N.; Fhoula, I.; Hernández-Alcántara, A.M.; Mohedano, M.L.; Najjari, A.; Prieto, A. The role of dextran production in the metabolic context of Leuconostoc and Weissella Tunisian strains. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountzouris, K.C.; Gilmour, S.G.; Jay, A.J.; Rastall, R.A. (1999). A study of dextran production from maltodextrin by cell suspensions of Gluconobacter oxydans NCIB 4943. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 87, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robyt, J.F. Structure, biosynthesis and uses of non-starch polysaccharides: dextran, alternan, pullulan and algin. In Developments in Carbohydrate Chemistry; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1992; pp. 261–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hehre, E.J. Production from sucrose of a serologically reactive polysaccharide by a sterile bacterial extract. Sci. 1941, 93, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naessens, M.; Cerdobbel, A.; Soetaert, W.; Vandamme, E.J. Leuconostoc dextransucrase and dextran: production, properties and applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2005, 80, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, E.J.; Hamilton, D.M. Bacterial conversion of dextrin into a polysaccharide with the serological properties of dextran. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1949, 71, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, E.J. The biological synthesis of dextran from dextrins. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 192, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, k.; Yoshikawa, K.; Kitahata, S.; Okada, S. Purification and some properties of dextrin dextranase from Acetobacter capsulatus ATCC 11894. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 1992, 56, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Wang, S.; Kan, F.; Wei, D.; Li, F. A novel dextran dextrinase from Gluconobacter oxydans DSM-2003: purification and properties. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 168, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Yoshikawa, K.; Okada, S. Structure of dextran synthesized by dextrin dextranase from Acetobacter capsulatus ATCC 11894. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 1993, 57, 1450–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, C.; Pereira, C.S.S.; Naessens, M.; Parmentier, S.; Soetaert, W.; Vandamme, E.J. The genus Gluconobacter oxydans: comprehensive overview of biochemistry and biotechnological applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2007, 27, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naessens, M. Dextran Dextrinase from Gluconobacter oxydans: Production and Characterization. PhD thesis, Ghent University, Gent, 2003.

- Naessens, M.; Cerdobbel, A.; Soetaert, W.; Vandamme, E.J. Dextran dextrinase and dextran of Gluconobacter oxydans. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 32, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, B.S.; Park, S.K.; Lee, S.W.; Sung, C.K.; Seo, K.I. Viscosity of exopolysaccharide from Xanthomonas sp. EPS-1. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 1996, 25, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Vettori, M.H.P.B.; Blanco, K.C.; Cortezi, M.; De Lima, C.J.; Contiero, J. Dextran: effect of process parameters on production, purification and molecular weight and recent applications. Diálogos Ciênc. 2012, 31, 171–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food, S.C.O.; Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on a Dextran Preparation, Produced using Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Lactobacillus spp. as a Novel Food Ingredient in Bakery Products. European Commission; Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General, Brussels. 18 October 2000.

- Wang, S.; Mao, X.; Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Li, F.; Wei, D. Characterization of a novel dextran produced by Gluconobacter oxydans DSM 2003. Appl, Microbiol, Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Yoshikawa, K.; Okada, S. Substrate Specificity of dextrin dextranase from Acetobacter capsulatus ATCC 11894. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 1994, 58, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, V.K.; Qazi, G.N.; Kumar, A. Gluconobacter oxydans: Its Biotechnological Applications. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 3, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Yang, X.; Gan, T.; Zhou, W.; Lin, J.; Wei, D. High cell density fermentation of Gluconobacter oxydans DSM 2003 for glycolic acid production. J, Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 36, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habe, H.; Shimada, Y.; Yakushi, T.; Hattori, H.; Ano, Y.; Fukuoka, T.; Kitamoto, D.; Itagaki, M.; Watanabe, K.; Yanagishita, H.; Matsushita, K.; Sakaki, K. Microbial Production of Glyceric Acid, an Organic Acid That Can Be Mass Produced from Glycerol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7760–7766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Morita, N.; Kitamoto, D.; Yakushi, T.; Matsushita, K.; Habe, H. (2013). Change in product selectivity during the production of glyceric acid from glycerol by Gluconobacter atrains in the presence of methanol. AMB express. 2013, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong-Ce, H.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zheng, Y.G.; Shen, Y.C. Production of 1,3-Dihydroxyacetone from Glycerol by Gluconobacter oxydans ZJB09112. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, J.H.; Park, S.Y.; Park, C.S.; Park, B.R. Synthesis and physicochemical properties of polysaccharides by Gluconobacter oxydans with glycosyltransferase activity. Food Sci. Preserv. 2021, 28, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olijve, W.; Kok, J.J. An analysis of the growth of Gluconobacter oxydans in chemostat cultures. Arch. Microbiol. 1979, 121, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberbach, M.; Maier, B.; Zimmermann, M.; Büchs, J. Glucose oxidation by Gluconobacter oxydans: characterization in shaking-flasks, scale-up and optimization of the pH profile. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 62, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, H.E.; Park, B.R.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, B.H. Slow digestion properties of long-sized isomaltooligosaccharides synthesized by a transglucosidase from Thermoanaerobacter thermocopriae. Food Chem. 2023, 417, 135892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prust, C.; Hoffmeister, M.; Liesegang, H.; Wiezer, A.; Fricke, W.F.; Ehrenreich, A. Complete genome sequence of the acetic acid bacterium Gluconobacter oxydans. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, O.; Matsushita, K.; Shinagawa, E.; Ameyama, M. Crystallization and characterization of NADP-dependent D-glucose dehydrogenase from Gluconobacter suboxydans. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1980, 44, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ley, J.; Swings, J. The genus Gluconobacter. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology; Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1984; pp. 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Zarour, K.; Llamas, M.G.; Prieto, A.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Dueñas, M.T.; de Palencia, P.F.; Lopez, P. Rheology and bioactivity of high molecular weight dextrans synthesised by lactic acid bacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 174, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, X. Hydrodynamic properties of aqueous dextran solutions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 111, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadahiro, J.; Mori, H.; Saburi, W.; Okuyama, M.; Kimura, A. Extracellular and cell-associated forms of Gluconobacter oxydans dextran dextrinase change their localization depending on the cell growth. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 456, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, W.; Kumagai, Y.; Sadahiro, J.; Saburi, W.; Sarnthima, R.; Tagami, T.; Kimura, A. A practical approach to producing isomaltomegalosaccharide using dextran dextrinase from Gluconobacter oxydans ATCC 11894. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Unno, T.; Okadal, G. Simple purification and characterization of an extracellular dextrin dextranase from Acetobacter capsulatum ATCC 11894. J. Appl. Glycosci. 1999, 46, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, N.W.; Fiala-Beer, E.; Walker, G.J. Dextran structural details from high-field proton NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 1990, 14, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Yan, L.; Phillips, R.J.; Reuhs, B.L.; Jones, K.; Rose, D.R.; Hamaker, B.R. Enzyme-synthesized highly branched maltodextrins have slow glucose generation at the mucosal α-glucosidase level and are slowly digestible in vivo. PloS one. 2013, 8, e59745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hamaker, B.R. Slowly digestible starch: concept, mechanism, and proposed extended glycemic index. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.M.; Lamothe, L.M.; Shin, H.; Austin, S.; Yoo, S.H.; Lee, B.H. Determination of glucose generation rate from various types of glycemic carbohydrates by mammalian glucosidases anchored in the small intestinal tissue. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, D.L.; Van Buul, V.J.; Brouns, F.J. Nutrition, health, and regulatory aspects of digestible maltodextrins. Crit. Rev. Food sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2091–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, D.S. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Jama. 2002, 287, 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Z.; Simsek, S.; Zhang, G.; Venkatachalam, M.; Reuhs, B.L.; Hamaker, B.R. Starch with a slow digestion property produced by altering its chain length, branch density, and crystalline structure. J. Agric. Food chem. 2007, 55, 4540–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Hamaker, B.R. Slowly digestible starch and health benefits. Resistant Starch. 2013, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).