Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Role of Plant Tissue Culture

- Callus and Cell Suspension Cultures: Sufficient for the production of uniform biomass. e.g., Taxus spp. cell cultures for the production of paclitaxel (Tomilova et al., 2023).

- Hairy Root Cultures: They are obtained from Agrobacterium rhizogenes and have genetic stability and high biosynthetic potential. Withania somnifera and Rauwolfia serpentine are a few among them (Singh et al., 2022; Srivastava et al., 2016).

- Shoot/Root Organ Cultures: Sustain site-specific biosynthesis, which generally yields more than undifferentiated cells (Kikowska et al., 2025; Sánchez-López et al., 2025).

1.2. Elicitation Strategies

- Biotic Elicitors: Consist of fungal or bacterial cell wall materials e.g., chitosan (Javed et al., 2025), yeast extract (Lescano et al., 2025).

- Abiotic Elicitors Salicylic acid (Rithichai et al., 2024), jasmonic acid (Rasheed et al., 2017 silver nanoparticles (Bernela et al.,2023; Verma et al., 2024 and UV light are some of them.

1.3. Precursor Feeding

1.4. Metabolic

- Overexpression of pathway-specific genes (e.g., PAL, CHS). Research has also been found to reveal that Salicylic acid and Gibberellic acid induce the expression of the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) synthesis genes responsible for an increase in phenolics (e.g., rosmarinic acid) and falvanoid as well in Salvia officinalis ( Moreira et al., 2022).

- Silencing of competitive pathways. The sterol pathway is a competitive pathway of artemisinin biosynthesis in A. annua. Four competitive branch pathway genes β-caryophyllene synthase gene (CPS), β-farnesene synthase gene (BFS), germacrene A synthase gene (GAS) and SQS were further down-regulated independently by the antisense method in A. annua. The content of artemisinin and dihydroartemisinic acid (DHAA) were increased significantly in different transgenic lines.

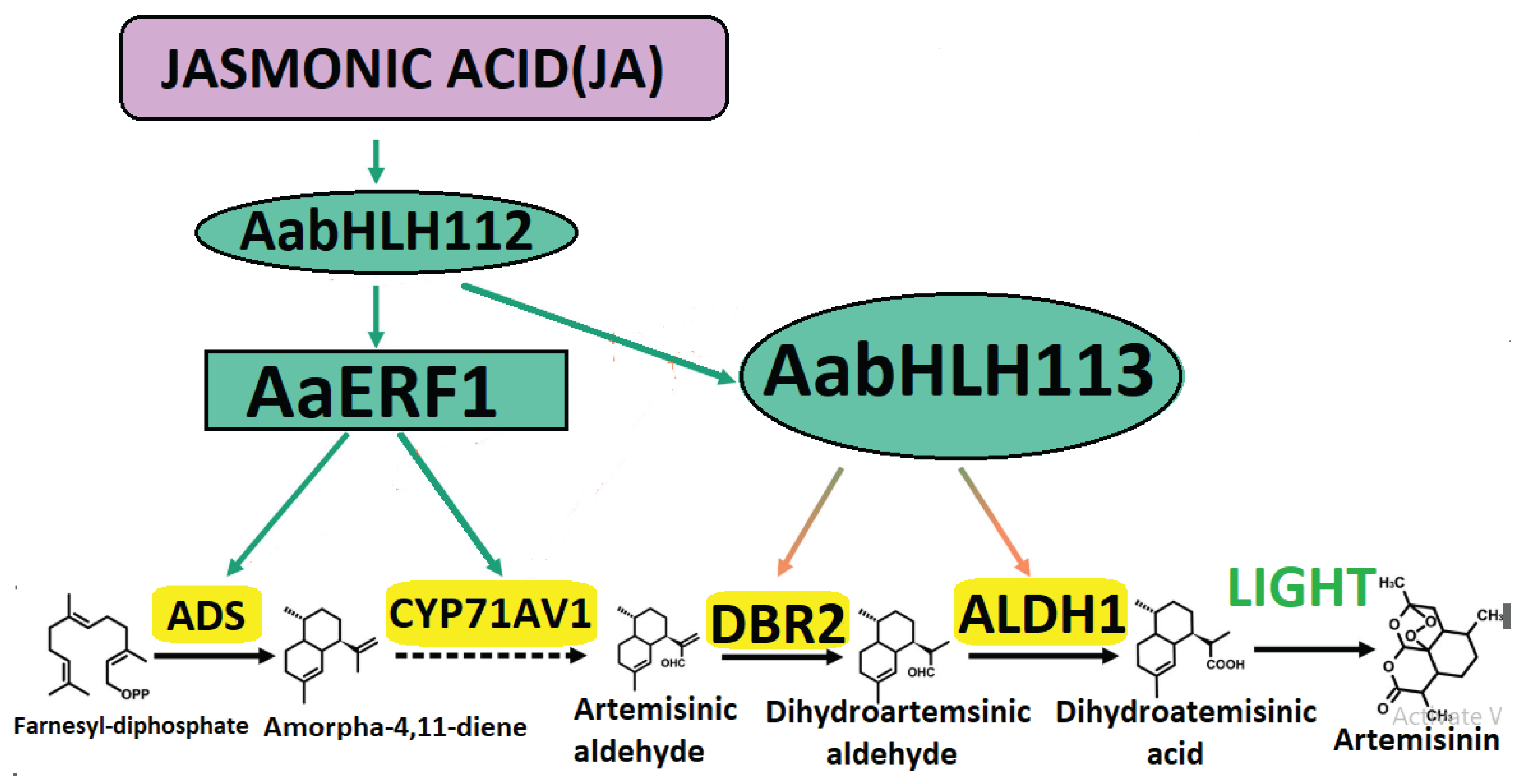

- Engineering transcription factors to co-upregulate multiple genes (Shi et al., 2024) (Figure 5).

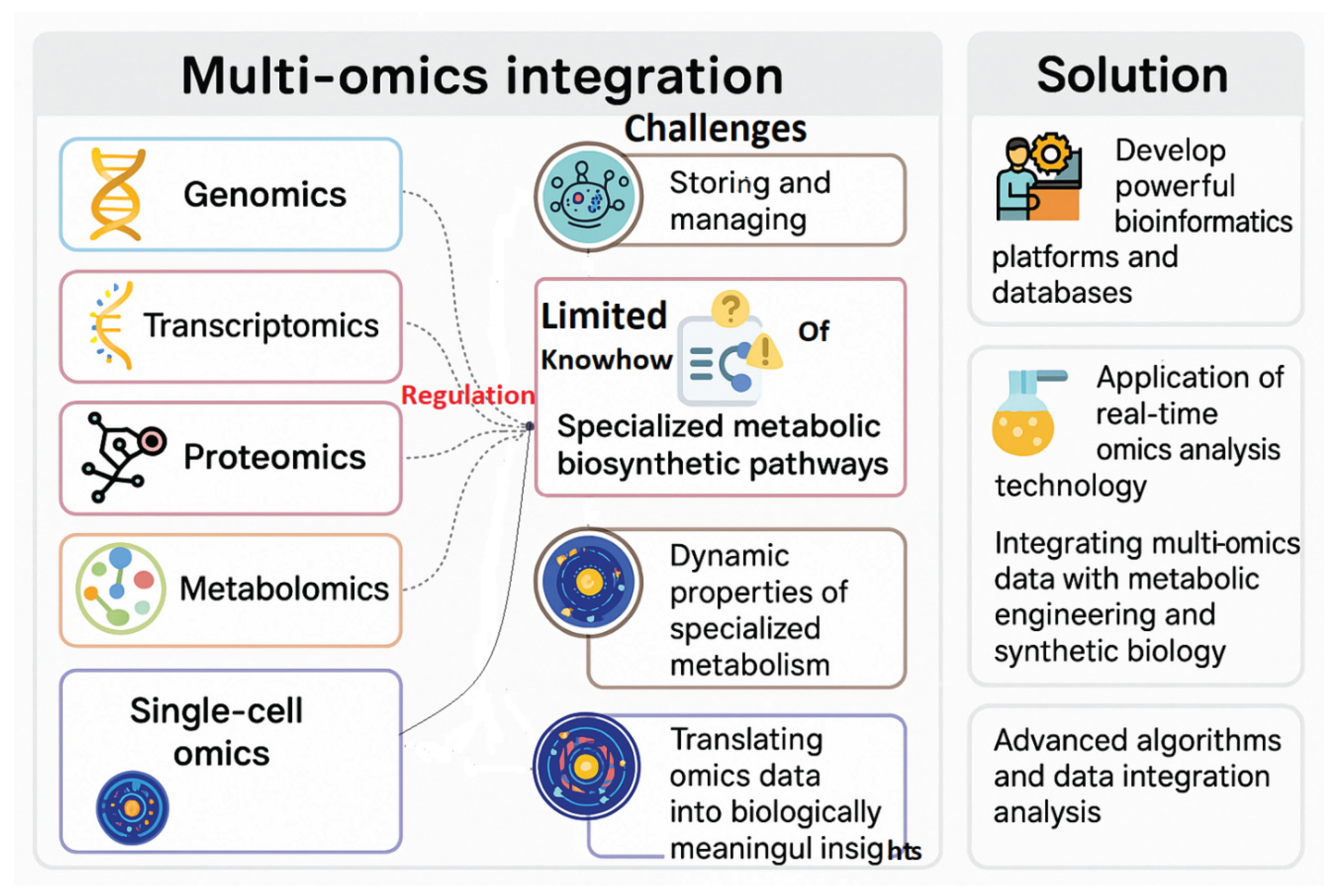

1.5. Omics and Systems Biology Approaches

- Selection of critical metabolic bottlenecks.

- Marker-assisted selection for cell lines with high yields.

- In silico modeling of biosynthetic networks for targeted intervention.

1.6. Limitations and Challenges

- Somaclonal variation in long-term cultures.

- Problems of scalability for commercial cultivation.

- Regulatory problems with genetically modified products.

- Limited knowledge of intricate metabolic controls in non-model plants (Dsouza et al., 2025; Karalija et al., 2025; Singh et al., 2025).

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

- PubMed

- ScienceDirect

- Scopus

- Google Scholar

- SpringerLink

2.2. Search Terms and Keywords

- “Secondary metabolites”

- “Medicinal plants”

- “Plant tissue culture”

- “Hairy root culture”

- “Elicitation”

- “Metabolic engineering”

- “Synthetic biology”

- “Biotechnological enhancement”

- “Plant-derived compounds”

- “Omics approaches in plants”

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Articles published in the English language.

- functor web Studies that report experimental or review data on biotechnological enhancement of secondary metabolites.

- functor web Research on plant in vitro culture methods (e.g., callus, hairy root, suspension culture).

- functor web Articles discussing elicitor-based, molecular, or omics-level intervention.

- Studies not focused on medicinal plants.

- Articles with poor methodological description.

- Descriptions of primary metabolites or non-target plant species.

- Articles in non-peer-reviewed journals or without available full texts.

2.4. Organization and Data Extraction

- Type of biotechnological intervention (e.g., elicitation, genetic modification, tissue culture)

- Plant species studied

- Targeted enhanced metabolite(s)

- Mechanism or pathway targeted

- Experimental outcome and yield improvements

2.5. Review Process and Quality Evaluation

- Scientific quality and reproducibility

- Novelty in methodology

- Relevance to upgrading of pharmaceutically important compounds

2.6. Synthesis of Results

- In vitro tissue culture techniques

- Elicitor-based improvement

- Synthetic biology and metabolic engineering

- Indirect tissue culture strategies (miRNA, Ploidy)

- Omics and systems biology platforms

3. Results

3.1. Tissue Culture-Based Enhancement

3.2. Elicitor-Mediated Enhancement

3.3. Genetic Modification and Metabolic Engineering

3.4. Indirect Methods of Plant Tissue Culture Use

3.4.1. MicroRNA (amiRNA, eTMs)

3.4.2. Ploidy Engineering

3.5. Omics and Systems Biology Contributions

4. Discussion

4.1. Refinement of Tissue Culture Based

4.2. Elicitor Mediated Enhancement

4.3. Metabolic Engineering and Genetic Modification

4.4. Ploidy Engineering

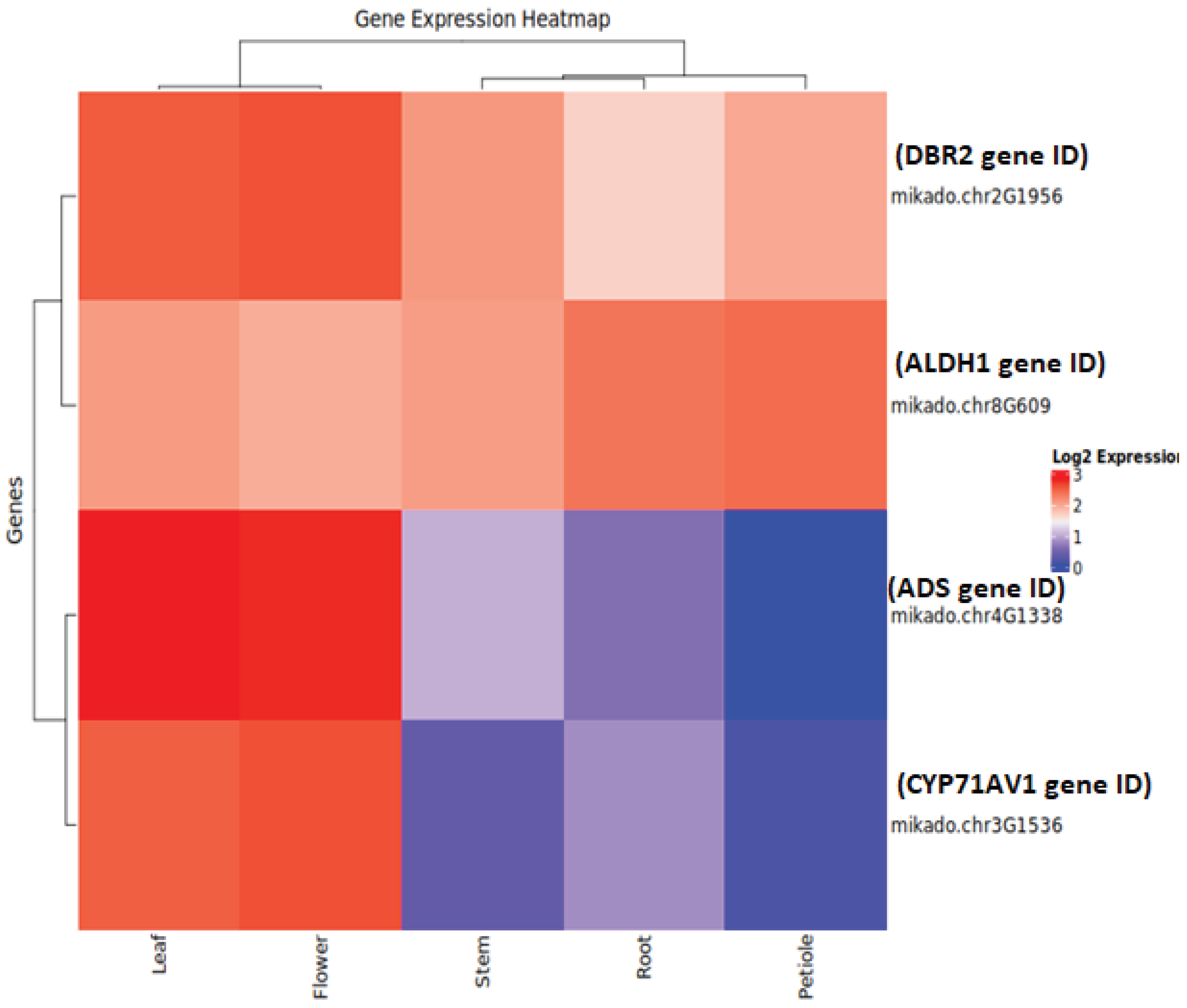

4.5. Engineering Strategies to Enhancing Artemisinin Synthesis in Artemisia annua

5. Future Prospects

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdoli, M., Moieni, A., & Naghdi Badi, H. (2013). Morphological, physiological, cytological and phytochemical studies in diploid and colchicine-induced tetraploid plants of Echinacea purpurea (L.). Acta Physiologiae Plantarum, 35(7), 2075-2083. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11738-013-1242-9. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J. M., Sudheer, W. N., Lakshmaiah, V. V., Mukherjee, E., Nizam, A., Thiruvengadam, M., M., Nagella, P., Alessa, F.M., Al-Mssallem, M.Q., Rezk, A.A. and Shehata, W.F., & Attimarad, M. (2022). Biotechnological approaches for production of artemisinin, an anti-malarial drug from Artemisia annua L. Molecules, 27(9), 3040. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/9/3040. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., Kwon, M., & Kim, J. Y. (2024). Enhancement of specialized metabolites using CRISPR/Cas gene editing technology in medicinal plants. Frontiers in plant science, 15, 1279738. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2024.1279738/full. [CrossRef]

- Delfi, S. A., Putri, S. I., Santoso, P., & Idris, M. (2025). Twenty-Five Years Research on Micropropagation of Stevia and Curcuma sp. and Improving Secondary Metabolites using Precursor-elicitor in vitro: A Review. Jurnal Biologi Tropis, 25(2), 1921-1940. [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, A., Dixon, M., Shukla, M., & Graham, T. (2025). Harnessing controlled-environment systems for enhanced production of medicinal plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 76(1), 76-93. [CrossRef]

- Fathimunnissa Begum, F. B. (2011). Augmented production of vincristine in induced tetraploids of Agrobacterium transformed shooty teratomas of Catharanthus roseus. Medicinal Plants, International journal of Phytomedicines and Related Industries. 3(1).59-64. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20123177175, https://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:mpijpri&volume=3&issue=1&article=008. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, I., Akram, M., Mukhtar, H., Gohar, U. F., Sajid, Z. A., & Hameed, U. (2023). Tissue Culture of Medicinal Plants. In Essentials of Medicinal and Aromatic Crops. 1-32. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-35403-8_1.

- Fett-Neto, A. G., & DiCosmo, F. (2020). Production of paclitaxel and related taxoids in cell cultures of Taxus cuspidata: perspectives for industrial applications. In Plant Cell Culture Secondary Metabolism Toward Industrial Application, 139-166. CRC Press. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9780138743208-6/production-paclitaxel-related-taxoids-cell-cultures-taxus-cuspidata-perspectives-industrial-applications-arthur-fett-neto-frank-dicosmo.

- Gantait, S., Das, S., Mahanta, M., & Banerjee, M. (2023). Influence of in vitro culture age on morphology, antioxidant activities, reserpine production, and genetic fidelity in Indian snakeroot (Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz.). South African Journal of Botany, 162, 864-872. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0254629923006002. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Pei, X., Song, X., Wang, S., Yang, Z., Zhu, J., Lin, Q., Zhu, Q., & Yang, X. (2025). Application and development of CRISPR technology in the secondary metabolic pathway of the active ingredients of phytopharmaceuticals. Frontiers in Plant Science, 15, 1477894. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2024.1477894/full. [CrossRef]

- Halder, T., & Ghosh, B. (2024). Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal: Enhanced production of withanolides and phenolic acids from hairy root culture after application of elicitors. Journal of Biotechnology, 388, 59-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2024.04.010, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168165624001093. [CrossRef]

- Hassani, D., Fu, X., Shen, Q., Khalid, M., Rose, J. K., & Tang, K. (2020). Parallel transcriptional regulation of artemisinin and flavonoid biosynthesis. Trends in plant science, 25(5), 466-476. https://www.cell.com/trends/plant-science/abstract/S1360-1385(20)30015-7?dgcid=raven_jbs_etoc_email.

- Javadian, N., Karimzadeh, G., Sharifi, M., Moieni, A., & Behmanesh, M. (2017). In vitro polyploidy induction: changes in morphology, podophyllotoxin biosynthesis, and expression of the related genes in Linum album (Linaceae). Planta, 245(6), 1165-1178. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00425-017-2671-2. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Cui, J. L., & Li, X. K. (2021). MicroRNA-mediated gene regulation of secondary metabolism in plants. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 40(6), 459-478. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07352689.2022.2031674. [CrossRef]

- Kajla, M., Roy, A., Singh, I. K., & Singh, A. (2023). Regulation of the regulators: transcription factors controlling biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites during biotic stresses and their regulation by miRNAs. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1126567. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1126567/full. [CrossRef]

- Karalija, E., Macanović, A., & Ibragić, S. (2025). Revisiting Traditional Medicinal Plants: Integrating Multiomics, In Vitro Culture, and Elicitation to Unlock Bioactive Potential. Plants, 14(13), 2029. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12252194/. [CrossRef]

- Karuppusamy, S. (2009). A review on trends in production of secondary metabolites from higher plants by in vitro tissue, organ and cell cultures. J Med Plants Res, 3(13), 1222-1239. https://academicjournals.org/article/article1380530836_Karuppusamy.pdf.

- Khan, A., Kanwal, F., Ullah, S., Fahad, M., Tariq, L., Altaf, M. T., Riaz, A., & Zhang, G. (2025). Plant secondary metabolites—Central regulators against abiotic and biotic stresses. Metabolites, 15(4), 276. https://www.mdpi.com/2218-1989/15/4/276. [CrossRef]

- Kharde, A. V., Chavan, N. S., Chandre, M. A., Autade, R. H., & Khetmalas, M. B. (2017). In vitro enhancement of bacoside in brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) using colchicine. J plant biochem physiol, 5(1), 1-6. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Autade-Haribhau/publication/312165383_In_Vitro_Enhancement_of_Bacoside_in_Brahmi_Bacopa_monnieri_Using_Colchicine/links/5873afdf08ae8fce4924bc61/In-Vitro-Enhancement-of-Bacoside-in-Brahmi-Bacopa-monnieri-Using-Colchicine.pdf?origin=journalDetail&_tp=eyJwYWdlIjoiam91cm5hbERldGFpbCJ9.

- Kikowska, M., Urbańska, M., Hermosaningtyas, A., Gornowicz-Porowska, J., Budzianowska, A., Siwulski, M., Blicharska, E., & Thiem, B. (2025). Biotechnological stimulation of phenolics in Lychnis flos-cuculi shoot cultures. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC), 162(1), 2. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11240-025-03117-z. [CrossRef]

- Kochan, E., Szymczyk, P., Kuźma, Ł., Lipert, A., & Szymańska, G. (2017). Yeast extract stimulates ginsenoside production in hairy root cultures of American ginseng cultivated in shake flasks and nutrient sprinkle bioreactors. Molecules, 22(6), 880. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/22/6/880. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S., Rai, N., Singh, S., Saha, P., Bisen, M. S., & Pandey-Rai, S. (2025). Functional identification of AaDREB-9 transcription factor in Artemisia annua L. and deciphering its role in secondary metabolism under PEG-induced osmotic stress. Plant Physiology Reports, 1-12. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40502-025-00857-0. [CrossRef]

- Lescano, L., Cziáky, Z., Custódio, L., & Rodrigues, M. J. (2025). Yeast extract elicitation enhances growth and metabolite production in Limonium algarvense callus cultures. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC), 160(2), 45. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11240-025-02991-x. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., Zhou, Y., Zhang, J., Lu, X., Zhang, F., Shen, Q., Q., Wu, S., Chen, Y., Wang, T., & Tang, K. (2011). Enhancement of artemisinin content in tetraploid Artemisia annua plants by modulating the expression of genes in artemisinin biosynthetic pathway. Biotechnology and applied biochemistry, 58(1), 50-57. https://iubmb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/bab.13. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Ahmad, N., Tao, Y., Hussain, H., Chang, Y., Umar, A. W., & Liu, X. (2025a). Reprogramming Hairy Root Cultures: A Synthetic Biology Framework for Precision Metabolite Biosynthesis. Plants, 14(13), 1928. https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/14/13/1928. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. H., Zeng, W. Q., Tao, S. F., Du, Y. N., Yu, F. H., Qi, Z. C., & Yang, D. F. (2025b). SmilODB: a multi-omics database for the medicinal plant danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza, Lamiaceae). Frontiers in Plant Science, 16, 1586268. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1586268/full. [CrossRef]

- Malu, M., Chatterjee, J., Choudhary, D., Ramakrishna, W., & Kumar, R. (2025). Biotic, abiotic, and genetic elicitors as a new paradigm for enhancing alkaloid production for pharmaceutical applications. South African Journal of Botany, 177, 579-597. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0254629924008019. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G. C., Carneiro, C. N., Dos Anjos, G. L., da Silva, F., Santos, J. L., & Dias, F. D. S. (2022). Support vector machine and PCA for the exploratory analysis of Salvia officinalis samples treated with growth regulators based in the agronomic parameters and multielement composition. Food Chemistry, 373, 131345. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308814621023517. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S., Biswas, D., & Ghosh, B. (2025). Carbohydrates acting as enhancers of secondary metabolites synthesis in in vitro cultures of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC), 161(2), 1-16. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11240-025-03055-w. [CrossRef]

- Navrátilová, B., Ondřej, V., Vrchotová, N., Tříska, J., Horník, Š., & Pavela, R. (2022). Impact of Artificial Polyploidization in Ajuga reptans on content of selected biologically active glycosides and Phytoecdysone. Horticulturae, 8(7), 581. https://www.mdpi.com/2311-7524/8/7/581. [CrossRef]

- Nordine, A. (2025). Trends in plant tissue culture, production, and secondary metabolites enhancement of medicinal plants: a case study of thyme. Planta, 261(4), 84. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00425-025-04655-8. [CrossRef]

- Paul, P., Singh, S. K., Patra, B., Sui, X., Pattanaik, S., & Yuan, L. (2017). A differentially regulated AP 2/ERF transcription factor gene cluster acts downstream of a MAP kinase cascade to modulate terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus. New Phytologist, 213(3), 1107-1123. https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nph.14252. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, F., Naeem, M., Uddin, M., & Khan, M. (2017). Synergistic effect of irradiated sodium alginate and methyl jasmonate on anticancer alkaloids production in periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus L.). https://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:jfeb&volume=7&issue=2&article=002. [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A. Rauf, A., Naz, S., Khan, M. U., Zahid, T., Ahmad, Z., Akram, Z., ... & Alhomrani, M. (2025). Aldose reductase inhibitory evaluation and in Silico studies of bioactive secondary metabolites isolated from Fernandoa. Adenophylla (Wall. Ex G. Don). Journal of Molecular Structure, 1328, 141308. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022286024038134. [CrossRef]

- Rithichai, P., Jirakiattikul, Y., Nambuddee, R., & Itharat, A. (2024). Effect of salicylic acid foliar application on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in holy basil (Ocimum sanctum L.). International Journal of Agronomy, 2024(1), 8159886. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1155/2024/8159886. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, G. C., Carranza-Ojeda, D., Pérez-Picaso, L., Martínez-Pascual, R., Viñas-Bravo, O., López-Torres, A., Molphe-Bach, E.P., García-Ríos, E., Morales-Serna, J.A., & Villalobos-Amador, E. (2025). Establishment of in vitro root cultures and hairy roots of Dioscorea composita for diosgenin production. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC), 161(1), 1-22. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11240-025-03022-5. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M., Zhang, S., Zheng, Z., Maoz, I., Zhang, L., & Kai, G. (2024). Molecular regulation of the key specialized metabolism pathways in medicinal plants. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 66(3), 510-531. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jipb.13634. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., Suyal, D. C., Dinkar, N., Joshi, S., Srivastava, N., Maurya, V. K., Agnihotri, A., & Agrawal, S. (2023). Agrobacterium rhizogenes as molecular tool for the production of hairy roots in Withania somnifera. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol., 11, 1-10. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/113878469/870_pdf-libre.pdf?1714297075=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DAgrobacterium_rhizogenes_as_molecular_to.pdf&Expires=1753888727&Signature=SLb2izVSl8HHUO9MjO~94lfbfFjfaBXG9wAt96q453~jE5A7QNcWRWctJBRi5yAjKkytRV0fIJst4fCgxQ1zKROymZINaWjO~mQG0CI9YvLSLZ7qCS0SDxwvGdPtRHq4japnEFojb9AIXJag4EFXnwxiOjU7e85zsRa0Mqbg~B2u3jtW338pe5wCV7gF-wOoG7w-MIbixF8ebhr5uHvxcSy~kUQWTDf-JnB-hOiluWM75Z2cIljV7gvHNduXhTgOEWKyRmvMI5Xmt69zwZ4BIK~iHJ5nT4mnRMgXvb391C4LBMz95-QgC~j-K5~V3MY3iv4DiVYjBK7i1KLNDiRWfg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

- Singh, R., Yadav, R., & Fatima, S. K. (2025). The engineering of medicinal plants: Future prospects and limitations. In Medicinal Biotechnology (pp. 79-102). Academic Press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780443222641000050.

- Srivastava, M., Sharma, S., & Misra, P. (2016). Elicitation based enhancement of secondary metabolites in Rauwolfia serpentina and Solanum khasianum hairy root cultures. Pharmacognosy magazine, 12(Suppl 3), S315. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4971950/. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M., Singh, G., Sharma, S., Shukla, S., & Misra, P. (2019). Elicitation enhanced the yield of glycyrrhizin and antioxidant activities in hairy root cultures of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 38(2), 373-384. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00344-018-9847-2. [CrossRef]

- Strzemski, M., Dresler, S., Hawrylak-Nowak, B., Tkaczyk, P., Kulinowska, M., Feldo, M., Maggi, F., & Hanaka, A. (2025). Chitosan elicitation enhances biomass and secondary metabolite production in Carlina acaulis L. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 23411. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-07085-4. [CrossRef]

- Svecarova, M., Navrátilová, B., Hasler, P., & Ondrej, V. (2019). Artificial induction of tetraploidy in Humulus lupulus L. using oryzalin. Acta Agrobotanica, 72(2). https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Artificial+induction+of+tetraploidy+in+Humulus+lupulus+L.+using+oryzalin&author=%C5%A0v%C3%A9carov%C3%A1,+M.&author=Navr%C3%A1tilov%C3%A1,+B.&author=Ha%C5%A1ler,+P.&author=Ond%C5%99ej,+V.&publication_year=2019&journal=Acta+Agrobot.&volume=72&pages=1764&doi=10.5586/aa.1764. [CrossRef]

- Swain, H. , Gantait, S., & Mandal, N. (2023). Developments in biotechnological tools and techniques for production of reserpine. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 107(13), 4153–4164. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, A., Almeida-Silva, F., Zhang, Y., Fu, X., Li, L., Wang, Y., & Tang, K. (2025). Artemisia Database: A Comprehensive Resource for Gene Expression and Functional Insights in Artemisia annua. bioRxiv, 2025-05. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.05.21.655314v1.abstract.

- Tomilova, S. V., Globa, E. B., Demidova, E. V., & Nosov, A. M. (2023). Secondary metabolism in Taxus spp. plant cell culture in vitro. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology, 70(3), 23. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S102144372270008X. [CrossRef]

- Twaij, B. M., & Hasan, M. N. (2022). Bioactive secondary metabolites from plant sources: types, synthesis, and their therapeutic uses. International Journal of Plant Biology, 13(1), 4-14. https://www.mdpi.com/2037-0164/13/1/3.

- Verma, P., Dixit, J., Singh, C., Singh, A. N., Singh, A., Tiwari, K. N., Muthu, M.S., Nath, G., & Mishra, S. K. (2024). Preparation of hydrogel from the hydroalcoholic root extract of Premna integrifolia L. and its mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for wound healing efficacy. Materials Today Communications, 41, 110228. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352492824022098. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Zhang, S., Li, R., & Zhao, Q. (2024). Unraveling the specialized metabolic pathways in medicinal plant genomes: A review. Frontiers in Plant Science, 15, 1459533. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2024.1459533/full. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Hu, Y., Hao, R., Li, R., Lu, X., Itale, M. W., Yuan, Y., Zhu, X., Zhang, J., Wang, L. and Sun, M., & Hou, X. (2025). Research Progress of Genomics Applications in Secondary Metabolites of Medicinal Plants: A Case Study in Safflower. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(8), 3867. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/26/8/3867. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L. Xiang, L., Zhu, S., Zhao, T., Zhang, M., Liu, W., Chen, M., Lan, X., & Liao, Z. (2015). Enhancement of artemisinin content and relative expression of genes of artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua by exogenous MeJA treatment. Plant growth regulation, 75(2), 435-441. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10725-014-0004-z. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L., Jian, D., Zhang, F., Yang, C., Bai, G., Lan, X., Chen, M., Tang, K., & Liao, Z. (2019). The cold-induced transcription factor bHLH112 promotes artemisinin biosynthesis indirectly via ERF1 in Artemisia annua. Journal of experimental botany, 70(18), 4835-4848. https://academic.oup.com/jxb/article/70/18/4835/5489275. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., Yan, T., Li, L., Chen, M., Hassani, D., Li, Y., Qin, W., Liu, H., Chen, T., Fu, X. and Shen, Q., & Tang, K. (2021). An HD-ZIP-MYB complex regulates glandular secretory trichome initiation in Artemisia annua. New Phytologist, 231(5), 2050-2064. https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nph.17514. [CrossRef]

- Yan, T., Chen, M., Shen, Q., Li, L., Fu, X., Pan, Q., Shi, P., Lv, Z., Jiang, W. and Ma, Y.N., & Tang, K. (2017). HOMEODOMAIN PROTEIN 1 is required for jasmonate-mediated glandular trichome initiation in Artemisia annua. New Phytologist, 213(3), 1145-1155. https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nph.14205. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Chen, W., Mei, Z., & Liu, Y. (2025). The multifaceted role of microRNA in medicinal plants. Medicinal Plant Biology, 4(1). https://maxapress.com/article/doi/10.48130/mpb-0025-0006. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y. C., Hou, J. M., Tian, S. K., Yang, L., Zhang, Z. X., Li, W. D., & Liu, Y. (2020). Overexpressing chalcone synthase (CHS) gene enhanced flavonoids accumulation in Glycyrrhiza uralensis hairy roots. Botany Letters, 167(2), 219-231. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23818107.2019.1702896. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M., Shu, G., Zhou, J., He, P., Xiang, L., Yang, C., Chen, M., Liao, Z., & Zhang, F. (2023). AabHLH113 integrates jasmonic acid and abscisic acid signaling to positively regulate artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. New Phytologist, 237(3), 885-899. https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nph.18567. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M., Sheng, Y., Bao, J., Wu, W., Nie, G., Wang, L., & Cao, J. (2025). AaMYC3 bridges the regulation of glandular trichome density and artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 23(2), 315-332. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/pbi.14449. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Zhu, Y., Jia, H., Han, Y., Zheng, X., Wang, M., & Feng, W. (2022). From plant to yeast—Advances in biosynthesis of artemisinin. Molecules, 27(20), 6888. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/20/6888. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, W., Tang, Y., & Wang, S. (2023). Transcriptomics and physiological analyses reveal changes in paclitaxel production and physiological properties in Taxus cuspidata suspension cells in response to elicitors. Plants, 12(22), 3817. https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/12/22/3817, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168165624001093. [CrossRef]

- Zunun-Pérez, A. Y., Guevara-Figueroa, T., Jimenez-Garcia, S. N., Feregrino-Pérez, A. A., Gautier, F., & Guevara-González, R. G. (2017). Effect of foliar application of salicylic acid, hydrogen peroxide and a xyloglucan oligosaccharide on capsiate content and gene expression associated with capsinoids synthesis in Capsicum annuum L. Journal of Biosciences, 42(2), 245-250. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12038-017-9682-9. [CrossRef]

| Plant Species | Culture Type | Target Metabolite | Yield Increase | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisia annua | Organ culture | Artemisinin | 7.8 fold | Al-Khayri et al., 2022 |

| Rauwolfia serpentina | Callus culture | Reserpine | 2 fold | Gantet et al., 2023 |

| Taxus brevifolia and Taxus cuspidata | Cell suspension | Paclitaxel | Commercial large scale | Fett-Neto & DiCosmo, 2020; Zhao et al., 2023 |

| Withania somnifera | Hairy roots | Withanolides | 11.49 fold | Haider and Gosh, 2024 |

| Elicitor Type | Plant Model | Metabolite | Observed Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgNPs | Achillea millefolium | Essential oil | 2.3× increase | Lala et al., 2021 |

| Cellulase | Glycyrrhiza glabra | Glycyrrhizin | 8.6× increase | Srivastava et al., 2019 |

| Jasmonic Acid | Catharanthus roseus | Vinblastine, Vincristine | 0.6× increase | Rasheed et al., 2017 |

| Salicylic Acid | Ocimum sanctum | Eugenol | 282.96× increase | Rithichai et al., 2024 |

| Yeast Extract | Panax ginseng | Ginsenosides | 1.57× increase | Kochan et al., 2017 |

| Modification Strategy | Plant | Gene Targeted | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme and amorpha-4,11-diene synthase coexpression | Artemisia annua | HMGR and ADS genes | ↑Artemisinin 8.65× increase |

Zhao et al., 2022 |

| ADS-FPPS enzymes co-expression | Artemisia annua | ADS-FPPS genes | ↑Artemisinin 2.6× increase |

Zhao et al., 2022 |

| Co-expression of TFs ORCA3 and MYC2 | Catharanthus roseus | Transcriptional regulators | ↑ TIA Biosynthesis as Vincristine and ajmalicine | Paul et al., 2017 |

| FPPS, CYP71AV1 and CPR enzymes co-expression | Artemisia annua |

FPPS, CYP71AV1 and CPR genes |

↑Artemisinin 3.6× increase |

Zhao et al., 2022 |

| Overexpression of CHS | Glycyrrhizia uralensis | Chalcone synthase | ↑ Flavonoid content | Yin et al., 2020 |

| salicylic acid/H2O2 | Capsicum annuum | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | ↑ Capsiate production | Zunun-Pérez et al., 2017 |

| Agent | Plant Model | Mechanism | Metabolite | Observed Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oryzalin | Ajuga reptans | Tetraploidy | 20-hydroxecdysone | Increased content | Navrátilová et al., 2022; Svecarova et al., 2019 |

| Colchicine | Catharanthus roseus | Autoploidy (chromosome doubling) | vincristine | 2× increase | Fathimunnissa, 2011 |

| Colchicine | Bacopa monnieri | Autoploidy (diploidy) | bacoside | 4× increase | Kharde et al., 2017 |

| Colchicine | Artemisia annua | Tetraploidy | artemisinin | 0.7× increase | Lin et al., 2011 |

| Colchicine | Echinacea purpurea | Tetraploidy | cichoric acid and chlorogenic acid | 0.45× and 0.71× increase respectively | Abdoli et al., 2013 |

| Colchicine | Linum album | Polyploidy | podophyllotoxin | 1.39× increase | Javadian et al., 2017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).