1. Introduction

Salvia rosmarinus (syn.

Rosmarinus officinals L.) [

1] commonly known as rosemary, is a perennial, aromatic shrub belonging to the

Lamiaceae family and native to the Mediterranean region. Traditionally cultivated for both culinary and medicinal purposes, rosemary has been integrated into the daily lives of Mediterranean populations for centuries. Its historical applications span a variety of ailments, including digestive complaints, headaches, muscle pain, and memory enhancement, reflecting its broad therapeutic reputation in folk medicine [

2,

3]. The growing demand for natural, plant-based therapeutics has propelled rosemary extract-based products to the forefront of the nutraceutical and functional food markets. The global rosemary extract market was valued at approximately USD 260 million in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 377 million by 2032, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.9% [

4]. This expansion is fueled by consumer preferences for clean-label, natural ingredients and the recognition of rosemary’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits across food, pharmaceutical, and personal care sectors).

The phytochemical richness of rosemary is central to its pharmacological potential. Its leaves are abundant in polyphenols, flavonoids, and terpenoids, standing out the phenolic diterpenes carnosic acid and carnosol, as well as rosmarinic acid. These compounds are recognized for their potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which are believed to underlie many of rosemary’s health-promoting effects [

5,

6,

7]. In addition, rosemary contains other bioactive constituents such as triterpenes (e.g., ursolic acid, betulinic acid), phenolic acids, and essential oils (e.g., 1,8-cineole, alpha-pinene), further contributing to its therapeutic versatility [

8]. Rosemary’s role in the Mediterranean diet is not only culinary but also therapeutic, as its regular consumption has been associated with reduced risk of chronic diseases prevalent in Mediterranean populations [

9,

10]. Pharmacological surveys have documented its use for metabolic, inflammatory, and neurocognitive disorders, supporting the scientific investigation of its traditional claims [

11,

12].

Contemporary research has elucidated several mechanisms underlying the health-promoting properties of rosemary extracts, with particular emphasis on their anti-inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, and antioxidant effects. The anti-inflammatory activity of rosemary is primarily attributed to the modulation of key molecular pathways, including the inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation, downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), and suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression [

5,

13]. Notably, both carnosic acid and carnosol have demonstrated the capacity to attenuate inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo, with evidence suggesting that whole rosemary extracts may exert synergistic effects beyond those of isolated compounds [

7,

14].

The antihyperglycemic properties of rosemary have been substantiated in several preclinical models of type 2 diabetes mellitus, where administration of rosemary extracts or their polyphenolic constituents resulted in significant reductions in fasting plasma glucose, improved lipid profiles, and enhanced antioxidant defense systems. Mechanistically, these effects are linked to the inhibition of intestinal glucosidase enzymes, enhancement of insulin sensitivity, and upregulation of endogenous antioxidant enzymes [

6,

10]. Recent human studies, though limited, have indicated that rosemary tea consumption can lead to significant improvements in glycemic control among individuals with type 2 diabetes, supporting its potential as a complementary metabolic regulator [

9].

Rosemary’s antioxidant capacity is largely ascribed to its high content of phenolic diterpenes and polyphenols, which act as free radical scavengers, metal ion chelators, and modulators of redox-sensitive signaling pathways such as Nrf2 [

15]. In vitro and in vivo studies have consistently demonstrated that rosemary extracts can inhibit lipid peroxidation, reduce oxidative stress markers, and enhance the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [

5,

10,

16]. These findings have prompted the widespread application of rosemary extracts as natural antioxidants in the food industry and as potential therapeutic agents for oxidative stress-related disorders.

These pharmacologically active molecules are plant’s secondary metabolites, which role is plant adaptation to changing environmental conditions, and therefore, inducible. Among the strategies to trigger plant secondary metabolism, beneficial bacterial strains and their metabolites have been used successfully [

17,

18]. Recent advances in nanotechnology have opened new avenues for enhancing plant metabolism by formulating the bacterial metabolites in nanoparticles, i.e. the metabolites are used as bioreductants of the metals, generating a nanoparticle coated with bacterial metabolites that hold biological activity [

19]. The biological synthesis of nanoparticles using bacterial metabolites or plant extracts (green synthesis) offers several advantages, including biocompatibility, reduced toxicity, and environmental sustainability, aligning with the growing demand for natural and safe therapeutic products [

20,

21]. A specific type of nanoparticles obtained by green synthesis were delivered to rosemary improving key phytochemicals contents, potentially amplifying their anti-inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, and antioxidant effects [

22,

23]. Bacterial metabolites act as reducing and capping agents in the green synthesis of metallic or polymeric nanoparticles, enabling the development of hybrid systems that harness both the therapeutic potential of rosemary and the functional benefits of nanotechnology [

24]. Preliminary in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that bacterial metabolites-loaded nanoparticles exhibit enhanced cellular uptake, with a consequent higher phytochemical modulation of the plant extract [

20,

23].

Among the beneficial strains, the genus

Pseudomonas holds a number of strains able to trigger plant metabolism [

25]. Strain

Pseudomonas shirazensis NFV3 had shown potential to stimulate plant immune system [

18], so we reasoned that it could stimulate rosemary metabolism, increasing phytochemical concentration, and therefore, its antioxidant potential and health benefits. To reach this objective, the strain, its metabolites and a formulation of this metabolites in silver nanoparticles were delivered to rosemary stems, and after a metabolomic characterization, the ability to inhibit alfa-lucosidase as indicator of antihyperglycemic activity, and COX1 and 2 as indicators of anti-inflammatory potential were evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Synthesis of Nanoparticles

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were synthesized following the protocol described by Plokhovska [

24]. Briefly, a 24-hour culture of

Pseudomonas shirazensis NFV3 (CECT 31128) was centrifuged, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.25 µm membrane to remove bacterial cells. The resulting filtrate was mixed with 1 mM AgNO₃ at a 2:4 (v/v) ratio and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. The synthesized AgNPs were characterized by UV-Vis spectroscopy (λ = 430 nm) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), revealing spherical nanoparticles with an average diameter of 20.71 ± 0.43 nm and an organic corona composed of bacterial metabolites. The AgNPs were lyophilized and resuspended in MilliQ water to a stock concentration of 6000 µg/mL; a working solution of 60 µg/mL was prepared for experiments (NP). The bacterial filtrate (ML) and corresponding cells were also used as treatments (LM, cells, respectively).

2.2. Plant Material and Experimental Setup

A total of twelve (Salvia rosmarinus) plants cultivated under homogeneous conditions were selected for the study. From each plant, apical stem segments measuring 15 cm in length were randomly excised to ensure sample homogeneity.

Four different treatments were prepared:

1. Control

2. Cells (bacterial cells suspended in water),

3. LM (likely a liquid medium containing bacterial metabolites),

4. NP (bacterial metabolites LM formulated in silver nanoparticles).

Each treatment was applied to three independent rosemary branches (n = 3 per treatment). For application, 5 mL of the corresponding solution were uniformly sprayed over the surface of each branch using a fine-mist sprayer. An additional set of three untreated branches was collected to serve as the negative control group.

All branches, treated and untreated, were air-dried under controlled laboratory conditions until they reached a constant weight, ensuring complete desiccation.

2.3. Sample Processing and Extraction Procedure

After drying, each rosemary branch (previously treated and used as a replicate) was processed individually. Leaves were carefully separated from the stems and ground using a mortar and pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen to facilitate sample pulverization.

To extract bioactive compounds, 0.5 g of the powdered material from each replicate was subjected to maceration in 10 mL of 75% ethanol (v/v). The extraction was performed overnight at room temperature (22 °C) under dark conditions to minimize photodegradation of sensitive metabolites. After maceration, the suspensions were centrifuged at 1100 rpm for 20 minutes. The supernatant was collected, and the pellet was discarded. This supernatant was then filtered through a 0.2 μm cellulose acetate membrane to remove particulate matter. The resulting filtrate was concentrated using a rotary evaporator until complete removal of the ethanol-water solvent phase.

The resulting dry extract was subsequently resuspended in the original volume (10 mL) of 100% ethanol to ensure concentration consistency across replicates. A final filtration through a 0.2 μm cellulose acetate filter was performed to ensure purity. Extracts were stored at –20 °C in amber, airtight glass vials to protect them from light and oxidation until further use.

2.4. Quantification of Active Compounds by HPLC

The chemical composition of the ethanolic extracts was analyzed using a modified version of the protocol described by Wellwood & Cole [

26]. The analysis was carried out using an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system, equipped with a G1315A diode array detector (DAD). Chromatographic separation was achieved using an Inertsil ODS-3V column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size; GL Sciences). The mobile phase consisted of:

1. Phase A: 90% (840 mL Milli-Q water + 8.5 mL acetic acid + 150 mL acetonitrile)

2. Phase B: 100% methanol

A linear gradient was applied, decreasing phase A from 90% to 0% over 30 minutes. The flow rate was set at 1.5 mL/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C.

Detection was performed at 284 nm, with a ±30 nm bandwidth, while full UV absorption spectra were recorded from 200 to 800 nm for each peak to support compound identification. Active constituents were identified based on retention times and spectral profiles, compared to authentic standards, and quantified using calibration curves constructed from standard compounds.

2.5. Metabolic Profile by HPLC-MS. Scan Mode

The metabolic profiling of

Salvia rosmarinus extracts was carried out using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS). Analyses were conducted at the Structural Molecular Analysis Unit of the SIDI (Interdepartmental Research Service, Autonomous University of Madrid) (

https://www.uam.es/uam/sidi/unidades-de-analisis/unidad-analisis-elemental-quimico-isotopico/cromatografia), following the protocol proposed by Sharma et al [

27]. In summary, Chromatographic separation was performed using a Bruker UHPLC/MS Triple Quadrupole ELITE system, equipped with an HPG1300 binary pump, automatic degasser, column oven (maintained at 40 °C), and a thermostatted autosampler BR840 set at 4 °C. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (Milli-Q water with 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid), delivered at a constant flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The following gradient program was applied: 0.00 min, 95% A / 5% B; 6.00 min, 85% A / 15% B; 21.00 min, 75% A / 25% B; 23.00 min, 50% A / 50% B; 24.10 min, 0% A / 100% B; 28.10 min, 95% A / 5% B; ending at 32.00 min with the initial conditions. Mass spectrometric detection was carried out using an ELITE triple quadrupole analyzer equipped with HESI (Heated Electrospray Ionization) and APCI sources. For HESI in negative ion mode, the following parameters were set, spray voltage 5000 V, capillary (cone) temperature 350 °C, cone gas flow 40 units, heated probe temperature 400 °C, probe gas flow 50 units, nebulizer gas flow 60 units, and the exhaust gas system activated. Identification of compounds was done by retention times as in [

27].

2.6. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The total phenolic content was determined spectrophotometrically using a Biomate-5 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A volume of 50 μL of the previously prepared ethanolic extract was used for each analysis. The Folin–Ciocalteu method, adapted from Benvenuti [

28] with slight modifications, was employed. Briefly, Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the extract, followed by sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃). After 30 minutes of incubation in the dark at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 765 nm. Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g) based on a standard calibration curve with gallic acid.

2.7. Total Flavonol Content (TFC)

The total flavonol content was quantified according to the colorimetric method proposed by Zhishen [

29], with modifications. For each sample, 1 mL of the ethanolic extract was reacted with aluminum chloride (AlCl₃) and sodium acetate under controlled conditions. Absorbance was measured at 510 nm, and quantification was based on a calibration curve prepared with quercetin. Results were expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg QE/g).

2.8. Antioxidant Capacity (AC) by DPPH Assay

The antioxidant capacity (TAC) of the extracts was assessed using the colorimetric DPPH assay described by Di Sotto [

30], with some modifications using a 0.11 mM DPPH solution and measuring the decrease in absorbance at 517 nm and gallic acid as positive control. The assay was performed in duplicates, using three replicates per sample. Gallic acid was used as positive control and IC50 (g/mL) was calculated for each extract.

2.9. Inhibition of α-glucosidase activity

The inhibitory activity of extracts on α-glucosidase was evaluated using a microplate-based assay. The assay utilizes α-glucosidase enzyme from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sigma Aldrich, G5003-1KU) and 4-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside (PNPG, Sigma Aldrich, N1377-1G) as the substrate. Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5) was prepared using 0.144 g KH₂PO₄, 9 g NaCl, and 0.795 g Na₂HPO₄·7H₂O per liter of distilled water.

Test samples were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The enzyme solution was prepared at 0.2 U/mL by dissolving 1 mg of α-glucosidase in 50 mL of Milli-Q water and diluted to a final concentration of 0.015 U/mL per well. The PNPG substrate was freshly prepared at 4 mM and diluted to a final concentration of 1 mM in each well, with a total reaction volume of 200 μL.

All reagents and equipment were preheated to 37°C prior to use. In each well of a 96-well microplate, 125 μL of phosphate buffer, 10 μL of sample solution, 15 μL of enzyme solution, and 50 μL of PNPG substrate were added sequentially. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C, and the formation of p-nitrophenol was monitored by measuring absorbance at 405 nm every 30 seconds for 35 minutes using a microplate reader. The percentage inhibition of α-glucosidase activity was calculated for each sample concentration using the formula: % Inhibition = (Blank slope – Sample slope) / Blank slope) × 100, where the blank refers to wells without inhibitor. The IC₅₀ value was determined from the plot of sample concentration versus percentage inhibition. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and fresh substrate was prepared on the day of the experiment to ensure optimal results.

2.10. Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase Activity (COX)

Cyclooxygenase (COX) activity was assessed using the Cayman Chemical COX Activity Assay Kit (Item No. 760151), following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor adaptations as required. This colorimetric assay quantifies peroxidase activity by monitoring the oxidation of N, N, N’,N’-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD), which results in a measurable color change at 590 nm.

All reagents were equilibrated to room temperature before use. The assay was performed in a 96-well plate with a final volume of 210 µl per well. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, alongside background and standard controls. For background determination, 150 µl of each sample was boiled for five minutes, centrifuged, and the supernatant was used as the background control. The plate was set up as follows: COX standard wells received 150 µl Assay Buffer, 10 µl Hemin, and 10 µl COX Standard; background wells received 120 µl Assay Buffer, 10 µl Hemin, and 40 µl boiled sample; sample wells received 120 µl Assay Buffer, 10 µl Hemin, and 40 µl sample; COX1 or 2 specific inhibition wells received 110 µl Assay Buffer, 10 µl Hemin, 40 µl sample, and 10 µl of either DuP-697 or SC-560. The plate was gently shaken and incubated for five minutes at 25°C, after which 20 µl of colorimetric substrate was added to each well. The reaction was initiated by adding 20 µl of Arachidonic Acid solution, followed by a five-minute incubation at 25°C. Absorbance was measured at 590 nm using a microplate reader.

Data analysis involved calculating the average absorbance for each set of replicates and subtracting the background values from the corresponding sample and inhibitor wells. Total COX activity was determined according to the kit’s formula, accounting for the requirement of two TMPD molecules to reduce PGG2 to PGH2. Percent inhibition by each inhibitor was calculated to determine the relative proportions of COX-1 and COX-2 activity in the samples.

2.11. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

All extractions and quantifications were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and statistical reliability. Final values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent measurements per treatment. A one-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the differences among groups. When the ANOVA indicated statistical significance (p < 0.05), Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test was applied to identify pairwise differences. All statistical analyses were conducted using the JASP software (version 0.19.3) [JASP Team, University of Amsterdam].

3. Results

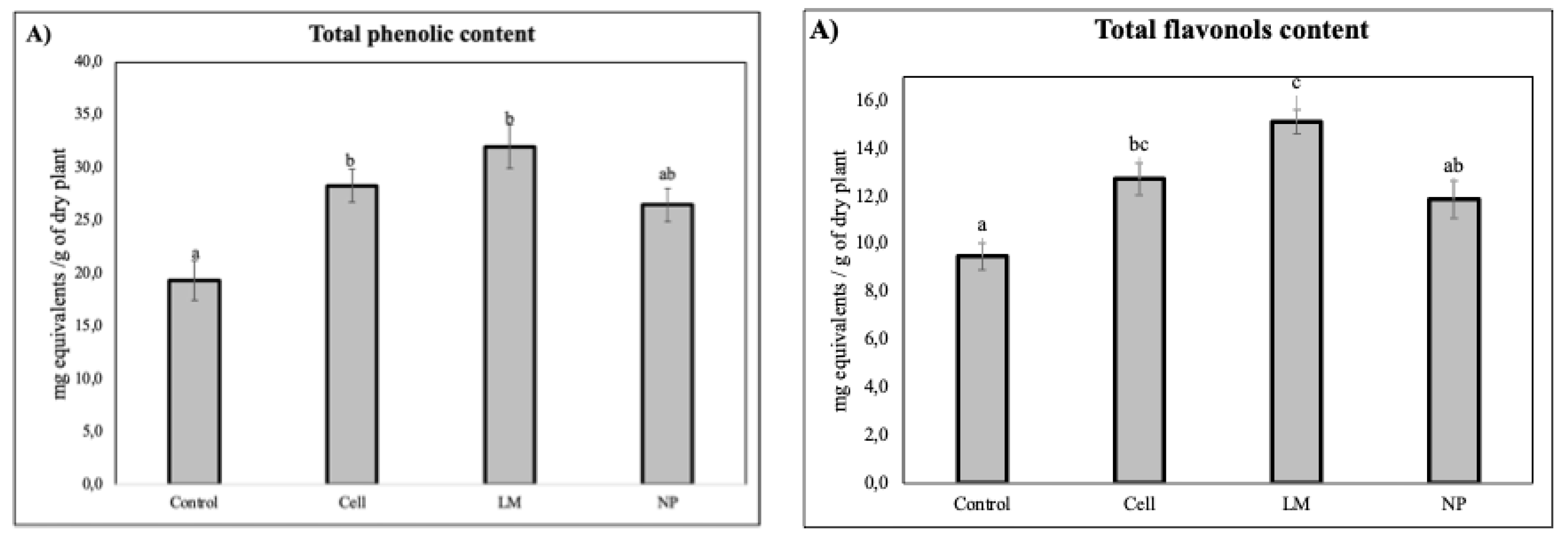

Quantification of total phenolic content revealed that all treatments significantly decreased total phenols and total flavonols in rosemary extracts (

Figure 1).

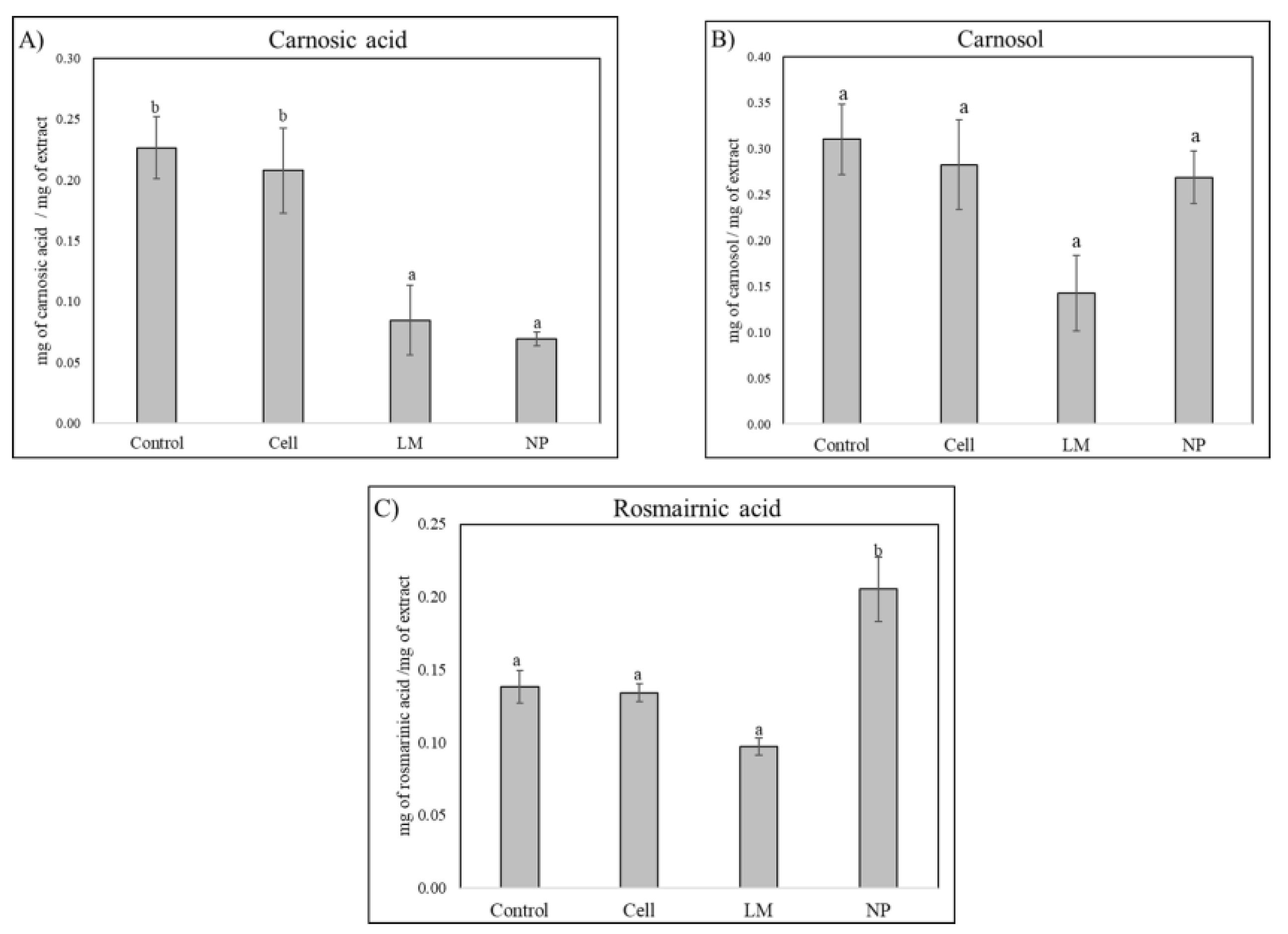

HPLC analysis revealed significantly lower concentration of the diterpene carnosol in LM and NP, while a significant increase in rosmarinic acid was detected in the NP treatments (

Figure 2)

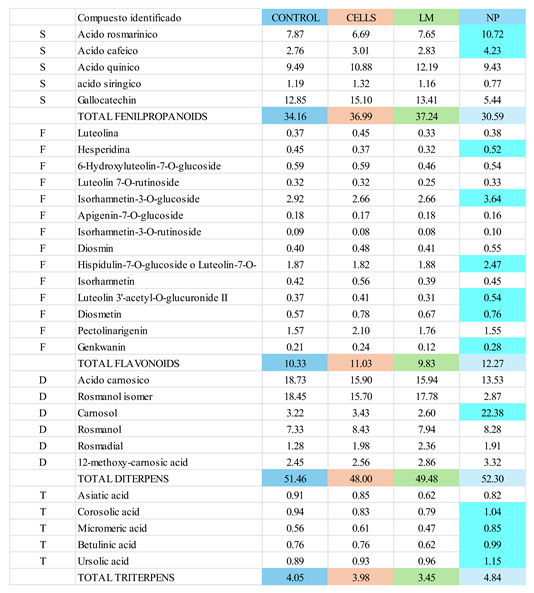

Scan HPLC-MS analysis of extracts revealed distinct variations in the metabolic profiles, specifically in the relative abundance of secondary metabolites among control, cell-treated, LM-treated, and NP-treated plant extracts (

Table 1). Notably, NP-treated samples exhibited selective upregulation of several key compounds, particularly within the phenylpropanoid and flavonoid classes. For instance, rosmarinic acid and caffeic acid among the fenilpropanoid class, luteolin-derivatives among the flavonoid class, carnosol in the diterpene class and all triterpenes except for asiatic acid. These changes suggest a targeted activation of specific branches of secondary metabolism in response to nanoparticle treatment. Conversely, other compounds such as gallocatechin or syringic acid were downregulated, indicating a possible metabolic reallocation or competitive flux through biosynthetic pathways. The detailed distribution of relative changes in metabolite abundance is summarized in

Table 1.

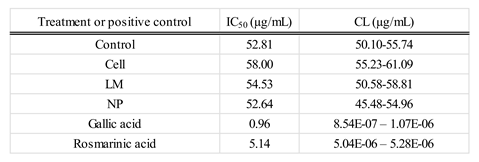

The Antioxidant Capacity (AC) of extracts according to DPPH Assay (

Table 2). IC₅₀ values (expressed in µg/mL) indicated similar antioxidant activity across most treatments when compared to the control, suggesting that the overall free radical scavenging capacity remained largely unaffected. Specifically, Cells and LM extracts exhibited slightly higher IC₅₀ values (58.00 and 54.53 µg/mL, respectively), which correspond to a modest reduction in antioxidant potency relative to the control. In contrast, the NP treatment demonstrated an IC₅₀ value of 52.64 µg/mL, closely comparable to that of the control (52.81 µg/mL), indicating that nanoparticle application-maintained antioxidant efficacy. These subtle variations may reflect differences in the qualitative composition of antioxidant compounds rather than total antioxidant capacity, highlighting the need for further analysis of specific metabolite contributions to the observed activity.

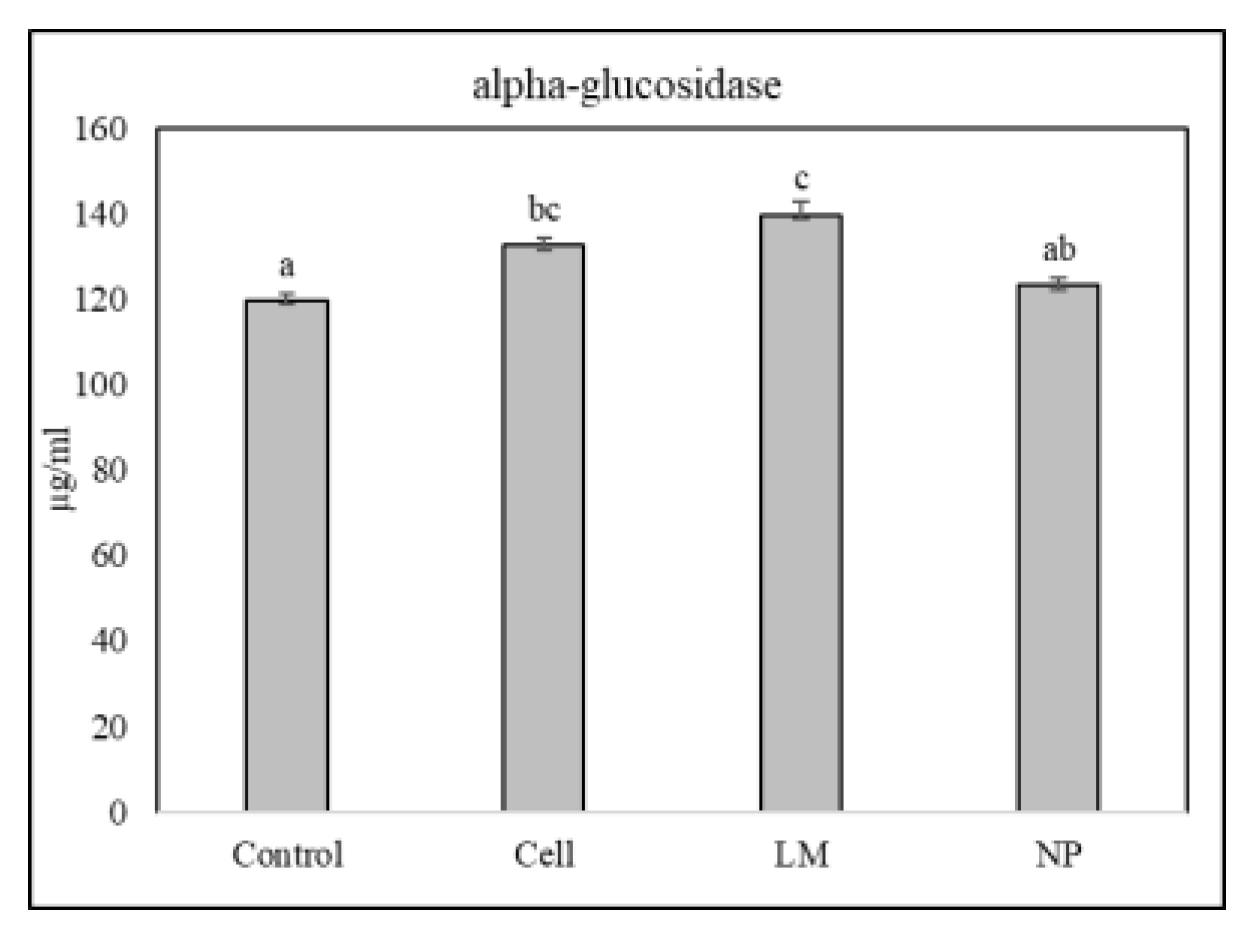

The extracts’ potential to inhibit α-glucosidase activity was calculated as IC50 (

Figure 3). Cells and LM extracts increased IC50 as compared to controls, therefore achieving worse results than controls or NP.

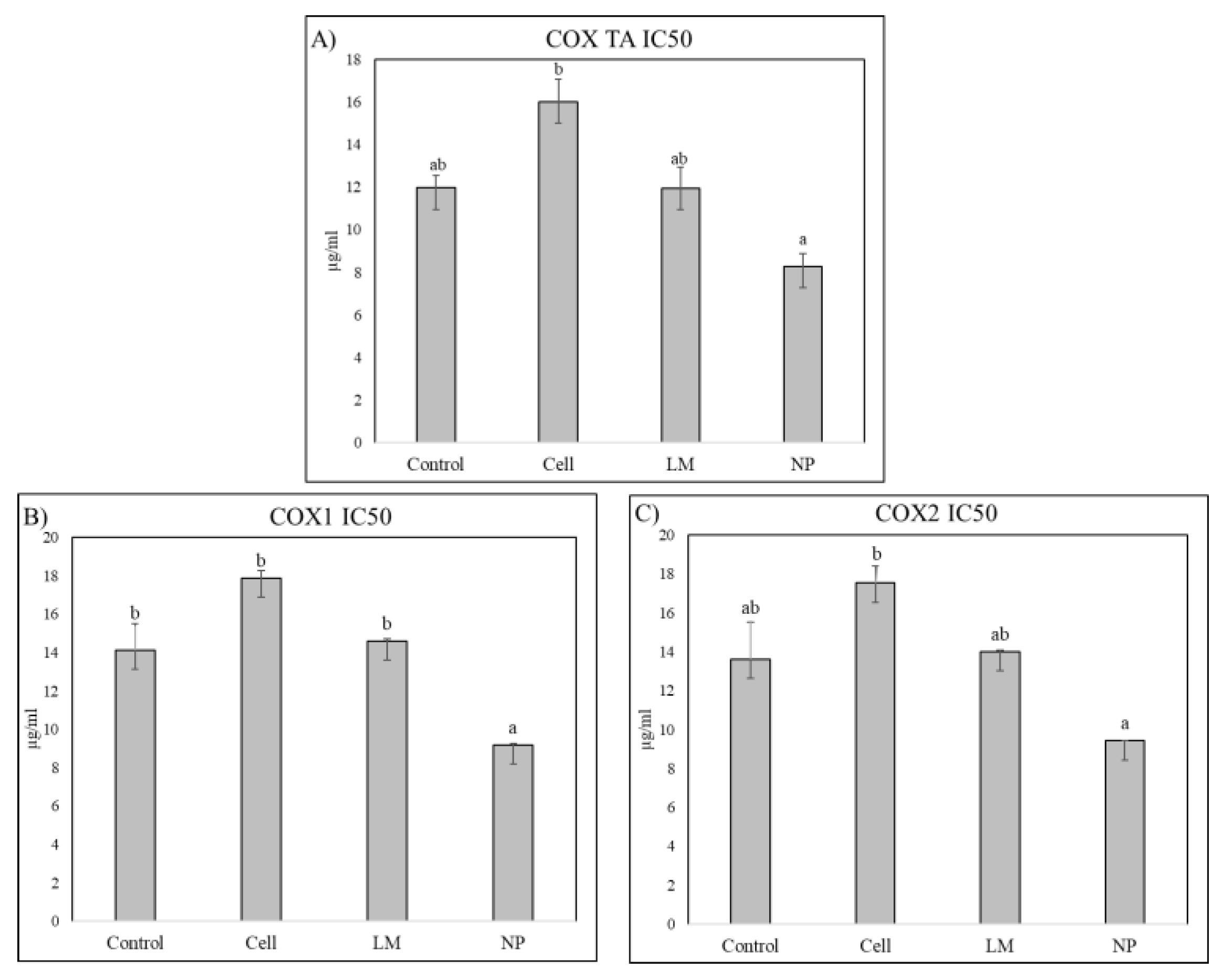

The extract’s anti-inflammatory potential was evaluated on the ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX), evaluating COX1, COX2 and total COX (

Figure 4).

COX inhibition assays revealed a significant decrease in IC₅₀ values for rosemary extracts derived from NP-treated plants, indicating enhanced inhibitory potency against both cyclooxygenase isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2. This suggests that nanoparticle treatment effectively increased the concentration or bioavailability of active compounds capable of modulating inflammatory pathways. The improved inhibition of COX enzymes highlights the potential of NP-mediated metabolic induction to augment the anti-inflammatory properties of rosemary extracts.

4. Discussion

The ability of AgNP coated with beneficial bacteria metabolites to trigger Salvia rosmarinus metabolism during the postharvest period has been shown as a valuable biotechnological tool to improve anti-inflammatory potential of rosemary extracts. AgNP cause a different response to that of the original strain or the complex mixture of bacterial metabolites, showing that effects are attributed to the formulation of metabolites on the nano size, that allows a deeper penetration and a concomitant more intense response.

The HPLC and HPLC-MS analyses conducted in this study revealed a significant metabolic modification in samples treated with AgNP, demonstrated by the increased accumulation rosmarinic acid and a decrease in carnosol (

Figure 2). These metabolites are well-documented for their potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, contributing substantially to the pharmacological value of

Salvia rosmarinus extracts [

5,

6,

7]. The observed modification on these compounds indicates a robust activation of the phenylpropanoid and modification of diterpenoid biosynthetic pathways, which are typically involved in response to biotic and abiotic stimuli [

10,

12].

Interestingly, the NP treatment resulted in a markedly lower concentration of carnosic acid compared to the control and other treatments. This suggests a selective modulation or metabolic reallocation triggered by the nanoparticle formulation, potentially involving differential regulation of key enzymes such as geranylgeranyl diphosphate reductase or ferruginol synthase, which are crucial in the diterpenoid biosynthetic cascade [

31]. Selective metabolic reprogramming in response to nanoparticles has been previously described in species such as

Arabidopsis thaliana and

Medicago sativa, where metallic and polymeric nanoparticles induced divergent transcriptomic responses and metabolite fluxes depending on particle size, composition, and surface functionalization [

20,

21]. Such selective responses may be mediated by a combination of oxidative signaling, hormone crosstalk, and epigenetic reconfiguration, emphasizing the complexity of nanoparticle-plant interactions [

24].

The dual effect observed, wherein some branches of the secondary metabolism are enhanced while others are downregulated, underscores the specificity and potential of NP-based elicitation to fine-tune metabolite profiles. This complexity highlights the necessity of integrating omics approaches (transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) to comprehensively elucidate the molecular mechanisms underpinning such metabolic plasticity [

21,

23]. Moreover, studies involving nanoparticle uptake, translocation, and subcellular localization would further clarify how these materials influence cellular metabolism at the biochemical level [

20].

The HPLC-MS profiling further supported these findings, showing that all rosemary extracts exhibited a similar profile, all showed the same composition, despite profiles from NP-treated plants showed increased relative peak areas compared to controls (

Table 1); interestingly, triterpens were noticeable increased specially betulinic and ursolic acid. This broad-spectrum metabolic activation implies that nanoparticle exposure may act as a general elicitor, potentially triggering multiple biosynthetic pathways through stress-induced signaling networks such as ROS bursts, MAPK cascades, or jasmonate signaling [

21,

24]. These networks are known to orchestrate transcriptional reprogramming of specialized metabolism genes, contributing to the activation of complex metabolite assemblages that confer adaptive advantages to the plant while simultaneously increasing extract bioactivity [

5].

In pharmacological terms, this compositional remodeling translated into functional improvements in terms of anti-inflammatory potential but not to hypoglycemic effects. Notably, COX inhibition assays demonstrated a significant decrease in IC₅₀ values for extracts derived from NP-treated plants, indicating enhanced inhibitory activity against both COX-1 and COX-2 isoforms. This increased potency correlates with the observed accumulation of specific anti-inflammatory compounds such as rosmarinic acid, diosmetin, micromeric acid, and carnosol, all of which are known to interfere with eicosanoid synthesis or modulate NF-κB signaling [

5,

7,

14]. This pharmacological enhancement occurred despite the absence of significant differences in total phenolic content, emphasizing that it is the qualitative remodeling of the bioactive profile, not merely a quantitative increase, that defines extract potency and activity [

10,

23].

These findings indicate that nanoparticle treatment not only expands the overall metabolite pool but also specifically modulates the composition and functional direction of the secondary metabolome to enhance its anti-inflammatory potential. This insight is particularly valuable for phytopharmaceutical applications, where the therapeutic efficacy of plant extracts often depends on the presence of synergistic combinations of bioactive compounds rather than high concentrations of a single molecule [

5,

9,

32]. In this context, NP-mediated elicitation emerges as a promising tool in the field of plant metabolic engineering, allowing for controlled enhancement of targeted pharmacological properties [

21,

24].

In contrast to the highly specific metabolic remodeling observed in NP-treated plants, total phenolic quantification showed no significant differences between NP and the control, suggesting that the overall pool of phenolic compounds remained relatively stable. However, both cells and LM treatments led to a statistically significant increase in total phenolics, reflecting a broader, non-selective stimulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism [

6,

12]. This observation indicates that while classical biotechnological tools such as plant cell cultures or metabolic liquids can upregulate entire pathways, nanoparticle formulations offer the advantage of selective pathway modulation [ 23, 21].

The marked increase in flavonol content observed in extracts from LM-treated plants further supports this differential mode of action. It is plausible that LM contains endogenous or exogenously induced elicitors such as signaling peptides or microbial metabolites capable of activating transcription factors (e.g., MYB12, TTG1) involved in flavonoid biosynthesis [

20,

24] that are not able to reduce silver, and therefore out of the organic crown of NP. Given the central role of flavonoids in oxidative stress protection, UV shielding, and hormone transport, such increases have physiological relevance beyond pharmacological interest and may improve plant resilience and postharvest extract quality when delivered along the plant cycle [

9,

10].

Regarding antioxidant activity, IC₅₀ values from DPPH assays showed only modest variations across treatments, with NP extracts exhibiting nearly identical antioxidant potency to control samples. Although cells and LM treatments yielded slightly higher IC₅₀ values, suggesting marginally lower scavenging capacity, these changes are unlikely to be biologically significant. Rather, they likely reflect qualitative shifts in the antioxidant profile, wherein metabolites with high radical scavenging potential may be replaced by others with lower activity but greater relevance to anti-inflammatory or cytoprotective functions [

5,

7,

10]. This further illustrates that antioxidant capacity is a multifactorial trait governed not solely by phenolic abundance, but by the chemical nature, redox potential, and synergistic interactions of the constituent metabolites.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that formulating Pseudomonas shirazensis bacterial metabolites in nanoparticles can effectively modulate the secondary metabolism of Salvia rosmarinus, leading to significant alterations in metabolite composition and pharmacological activity, even when delivered during the postharvest period. Nanoparticle treatments offer a unique advantage by enabling targeted remodeling of metabolite profiles, enhancing specific anti-inflammatory compounds without indiscriminately increasing total phenolics. These findings open new avenues for the application of nanotechnology in phytopharmaceutical optimization and targeted metabolic engineering. Further work integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data, as well as in vivo pharmacological and toxicological assessments, will be essential to fully exploit the therapeutic potential of nanoparticle-enhanced medicinal plant extracts.

In summary, delivering NP to Salvia rosmarinus during the postharvest period represents a promising tool to further increase natural bioactives, improving anti-inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, and antioxidant properties. This tool appears as an excellent alternative for the plant extracts industry. However, further research is required to overcome current challenges related to standardization, mechanistic elucidation, and clinical efficacy.

6. Patents

A patent application has been filed with reference P202430961 entitled “Pseudomonas shirazensis NVF3 y sus metabolitos vehiculizados en nanopartículas de plata como promotores del crecimiento vegetal, estimulantes de la adaptación en situaciones de estrés hídrico y del metabolismo secundario de interés farmacológico y alimentario. The IET+OE has been published and recognizes patentability. It is not public yet.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, BRS. and JGM.; methodology, EFG, EGA.; validation, EGA, JGM, BRS.; formal analysis, SA EFG EGA ; investigation, SA, EFG, EGA.; resources, BRS JGM; data curation, EGA EFG; writing—original draft preparation, EGA EFG.; writing—review and editing, EGA BRS.; visualization, JGM.; supervision, BRS.; project administration, BRS.; funding acquisition, BRS JGM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions fellowship (MSCA4Ukraine-project ID:101101923“. The APC was funded by own funds.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are stored on the computers of CEU San Pablo University and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no specific support or assistance to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Cell |

Pseudomonas shirazensis NFV3 cells suspended in water |

| LM |

Liquid medium containing metabolites Pseudomonas shirazensis NFV3 metabolites |

| NP |

Pseudomonas shirazensis NFV3 metabolites LM formulated in silver nanoparticles |

References

- Drew, B.T.; González-Gallegos, J.G.; Xiang, C.L.; Kriebel, R.; Drummond, C.P.; Walked, J.B.; Sytsma, K.J. Salvia united: The greatest good for the greatest number. Taxon 2017, 66, 133–145. [CrossRef]

- Begum, A.; Sandhya, S.; Ali, S.S.; Vinod, K.R.; Swapna, R.; Banji, D. An in-depth review on the medicinal flora Salvia rosmarinus (Lamiaceae). Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2013, 12, 61–73.

- de Oliveira, J.R.; Camargo, S.E.A.; de Oliveira, L.D. Salvia rosmarinus (rosemary): An ancient plant with uses in dentistry and medicine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 1137–1150.

- https://www.qyresearch.com/reports/3480301/rosemary-extract (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Habtemariam, S. Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutic Mechanisms of Natural Products: Insight from Rosemary Diterpenes, Carnosic Acid and Carnosol. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 545. [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, F.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Mohamadi, N.; Askari, V.R. Effects of rosmarinic acid, carnosic acid, rosmanol, carnosol, and ursolic acid on the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Biofactors 2023, 49, 478–501. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W.R.; Seca, A.M.L.; Silva, A.M.S. Diterpenes from rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus): Defining their pharmacological activities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 76, 90–99.

- Kurek-Górecka, A.; Górecki, M.; Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Balwierz, R.; Stojko, J. Salvia rosmarinus: A Comprehensive Review of its Phytochemical Profile and Health-Promoting Properties. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Drug Res. 2020, 11, 155–162.

- Efenberger-Szmechtyk, M.; Nowak, A.; Kregiel, D. Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) as a functional ingredient. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 68–82.

- Noor, S.; Mohammad, T.; Rub, M.A.; Raza, A.; Azum, N.; Yadav, D.K.; Hassan, M.I.; Asiri, A.M. Biomedical features and therapeutic potential of rosmarinic acid. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2022, 45, 205–228. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sereiti, M.R.; Abu-Amer, K.M.; Sen, P. Critical review on biological effect and mechanisms of diterpenoids from Salvia rosmarinus. Front. Med. Chem. 2025, 3, 112–130.

- Rašković, A.; Milanović, I.; Pavlović, N.; Ćebović, T.; Vukmirović, S.; Mikov, M. Antioxidant activity of rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) essential oil and its hepatoprotective potential. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 225.

- Wan, S.S.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, S.R.; Tang, S. The function of carnosic acid in lipopolysaccharides-induced hepatic and intestinal inflammation in poultry. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103415. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Lu, M.; Huang, R.; Wang, G.; Yushanjiang, F.; Jiang, X.; Li, J. Carnosol prevents cardiac remodeling and ventricular arrhythmias in pressure overload-induced heart failure mice. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 3763–3781.

- Tong, X.P.; Ma, Y.X.; Quan, D.N.; Zhang, L.; Yan, M.; Fan, X.R. Rosemary extracts upregulate Nrf2, Sestrin2, and MRP2 protein level in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 7359806. [CrossRef]

- El Kantar, S.; Yassin, A.; Nehmeh, B.; et al. Deciphering the therapeutical potentials of rosmarinic acid. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15489.

- Gutiérrez-Albanchez, E.; Gradillas, A.; García, A.; García-Villaraco, A.; Gutierrez-Mañero, F.J.; Ramos-Solano, B. Elicitation with Bacillus QV15 reveals a pivotal role of F3H on flavonoid metabolism improving adaptation to biotic stress in blackberry. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0232626. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rivilla, H.; Garcia-Villaraco, A.; Ramos-Solano, B.; Gutierrez-Manero, F.J.; Lucas, J.A. Metabolic elicitors of Pseudomonas fluorescens N21.4 elicit flavonoid metabolism in blackberry fruit. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 205–214.

- Plokhovska, S., García-Villaraco, A., Lucas, J. A., Gutiérrez-Mañero, F. J., & Ramos-Solano, B. Pseudomonas sp. N5. 12 Metabolites Formulated in AgNPs Enhance Plant Fitness and Metabolism Without Altering Soil Microbial Communities. Plants 2025, 14(11), 1655. [CrossRef]

- Marslin, G.; Sheeba, C.J.; Franklin, G. Nanoparticles alter secondary metabolism in plants via ROS burst. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 832.

- Silva, S.; Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Metabolomics as a Tool to Understand Nano-Plant Interactions: The Case Study of Metal-Based Nanoparticles. Plants 2023, 12, 491. [CrossRef]

- Hadi Soltanabad, M.; Bagherieh-Najjar, M.B.; Mianabadi, M. Carnosic Acid Content Increased by Silver Nanoparticle Treatment in Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191, 482–495.

- Afrouz, M.; Ahmadi-Nouraldinvand, F.; Elias, S.G.; Alebrahim, M.T.; Tseng, T.M.; Zahedian, H. Green synthesis of spermine coated iron nanoparticles and its effect on biochemical properties of Salvia rosmarinus. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 775. [CrossRef]

- Plokhovska, S., García-Villaraco, A., Lucas, J.A., Gutierrez-Mañero, F.J., Ramos-Solano, B. Silver nanoparticles coated with metabolites of Pseudomonas sp. N5.12 inhibit bacterial pathogens and fungal phytopathogens. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 1522. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Albanchez, E.; García-Villaraco, A.; Lucas, J.A.; Horche, I.; Ramos-Solano, B.; Gutierrez-Mañero, F.J. Pseudomonas palmensis sp. nov., a novel bacterium isolated from Nicotiana glauca microbiome: draft genome analysis and biological potential for agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 672751.

- Wellwood, C.R.; Cole, R.A. Relevance of carnosic acid concentrations to the selection of rosemary, Rosmarinus officinalis (L.), accessions for optimization of antioxidant yield. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 6101–6107. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Velamuri, R.; Fagan, J.; Schaefer, J. Full-spectrum analysis of bioactive compounds in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) as influenced by different extraction methods. Molecules 2020, 25, 4599.

- Benvenuti, S.; Pellati, F.; Melegari, M.; Bertelli, D. Polyphenols, anthocyanins, ascorbic acid, and radical scavenging activity of Rubus, Ribes, and Aronia. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, FCT164–FCT169.

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [CrossRef]

- Di Sotto, A.; Di Giacomo, S.; Amatore, D.; Locatelli, M.; Vitalone, A.; Toniolo, C.; Nencioni, L. A polyphenol rich extract from Solanum melongena L. DR2 peel exhibits antioxidant properties and anti-herpes simplex virus type 1 activity in vitro. Molecules 2018, 23, 2066. [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Lou, G.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, D. Unveiling the spatial distribution and molecular mechanisms of terpenoid biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza and S. grandifolia using multi-omics and DESI–MSI. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad109.

- González-Vallinas, M.; Reglero, G.; Ramírez de Molina, A. Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) extract as a potential complementary agent in anticancer therapy. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 1223–1231.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).