Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Preparation of the Extract

2.3. Phytochemical Characterization by Spectrophotometry

2.3.1. Quantitative Determination of Total Phenols

2.3.2. Quantitative Determination of Flavonoids

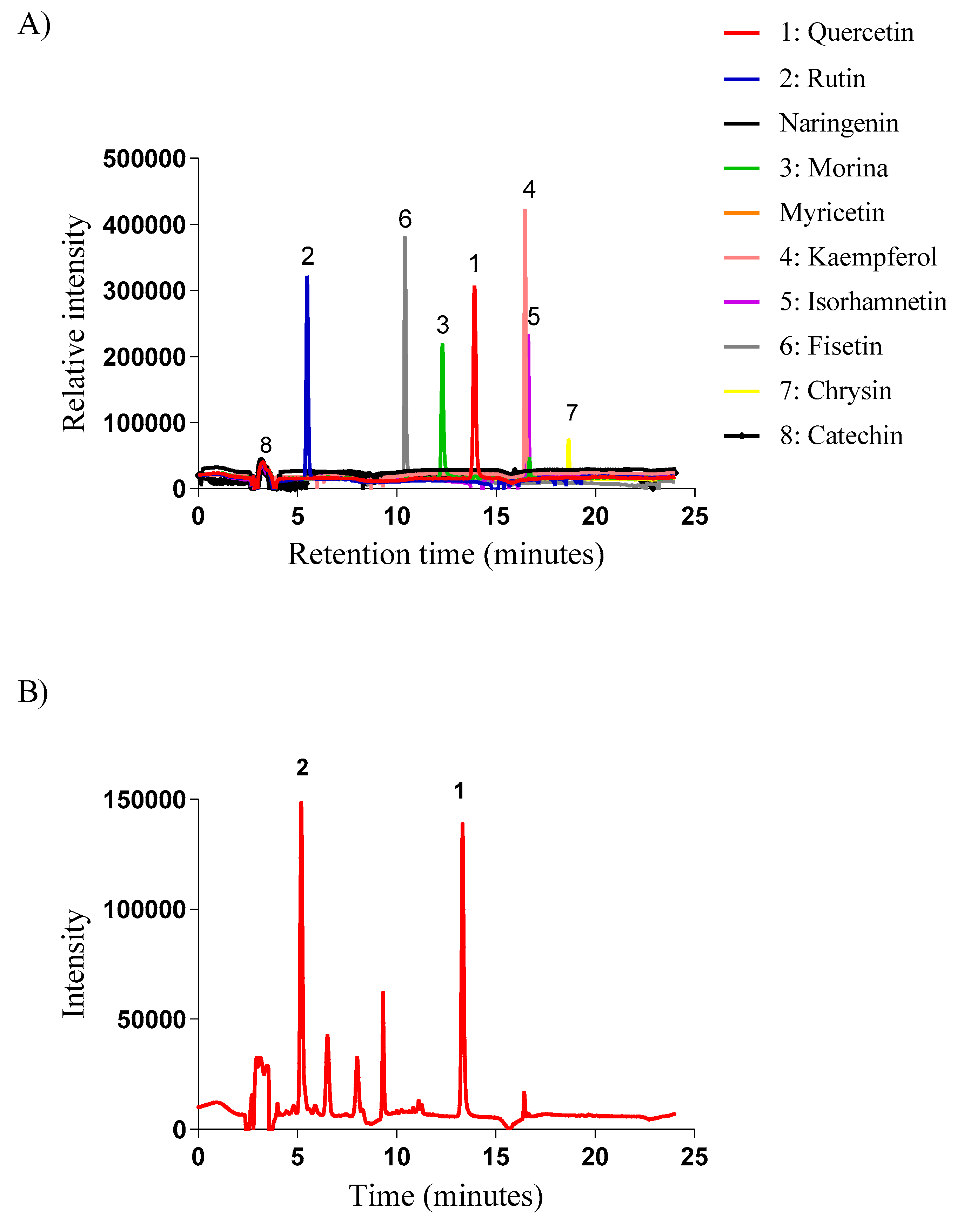

2.3.3. Phytochemical Characterization by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

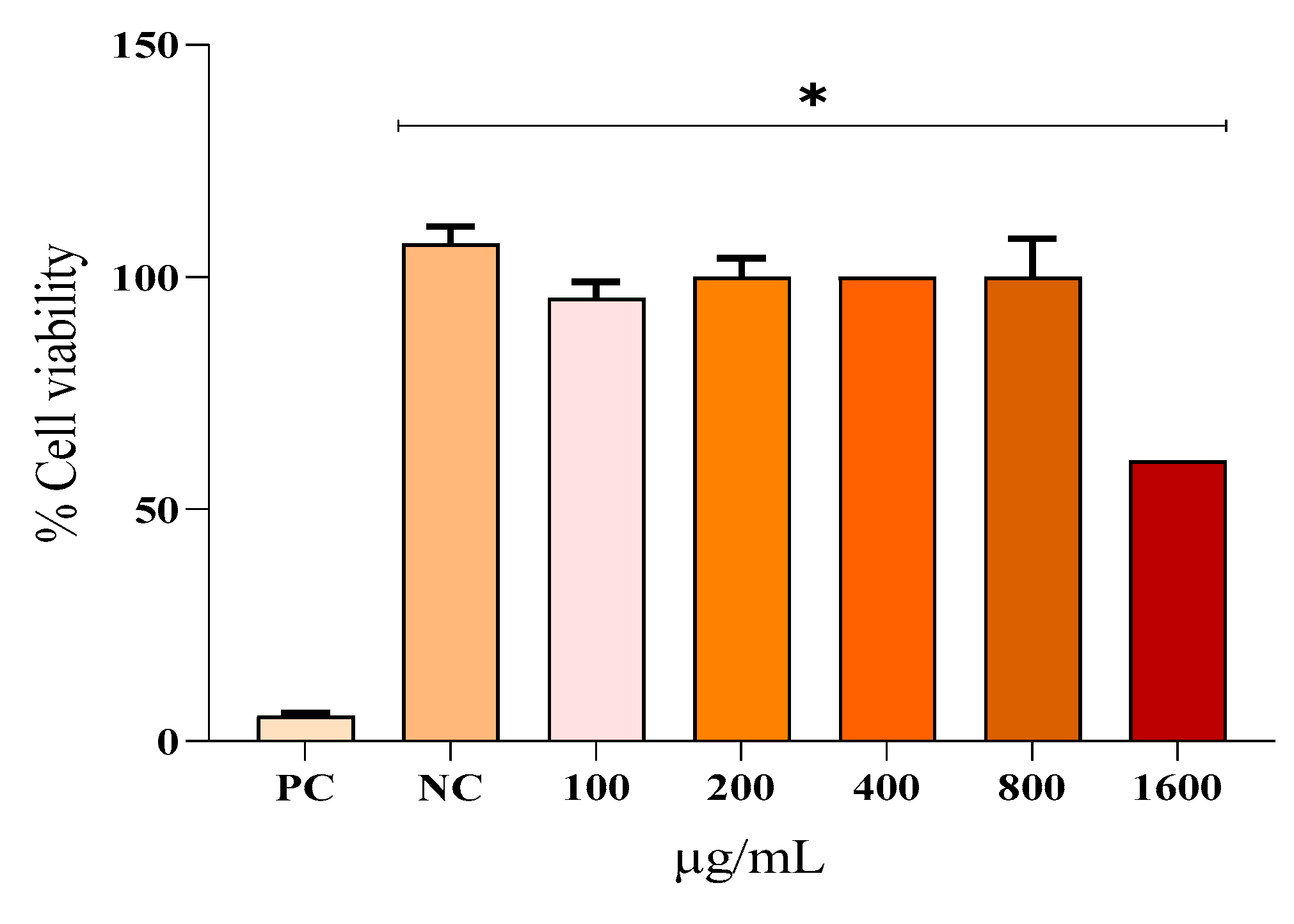

2.4. Evaluation of In Vitro Cytotoxicity by MTT [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide]

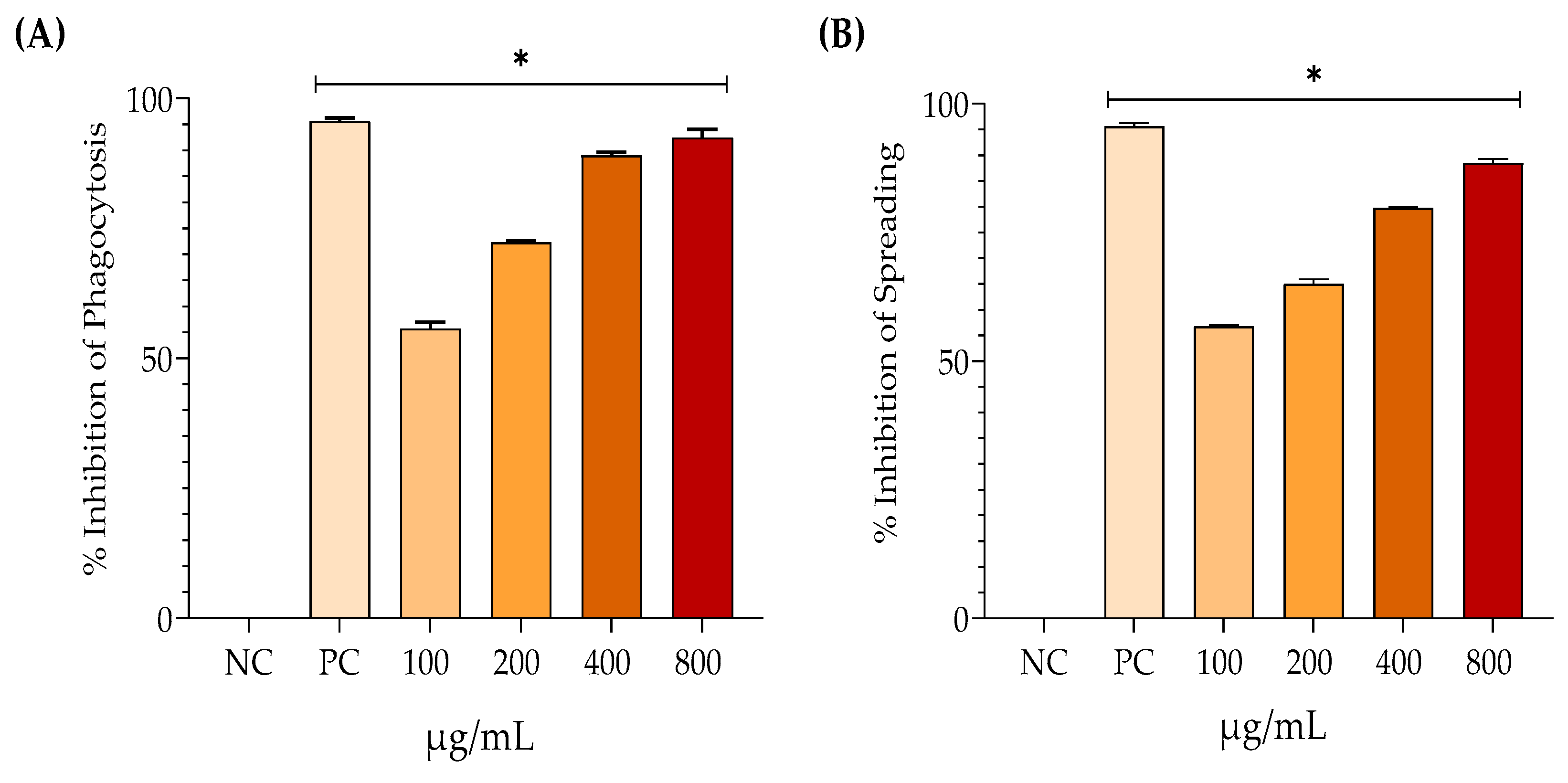

2.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.5.1. Phagocytosis

2.5.2. Spreading

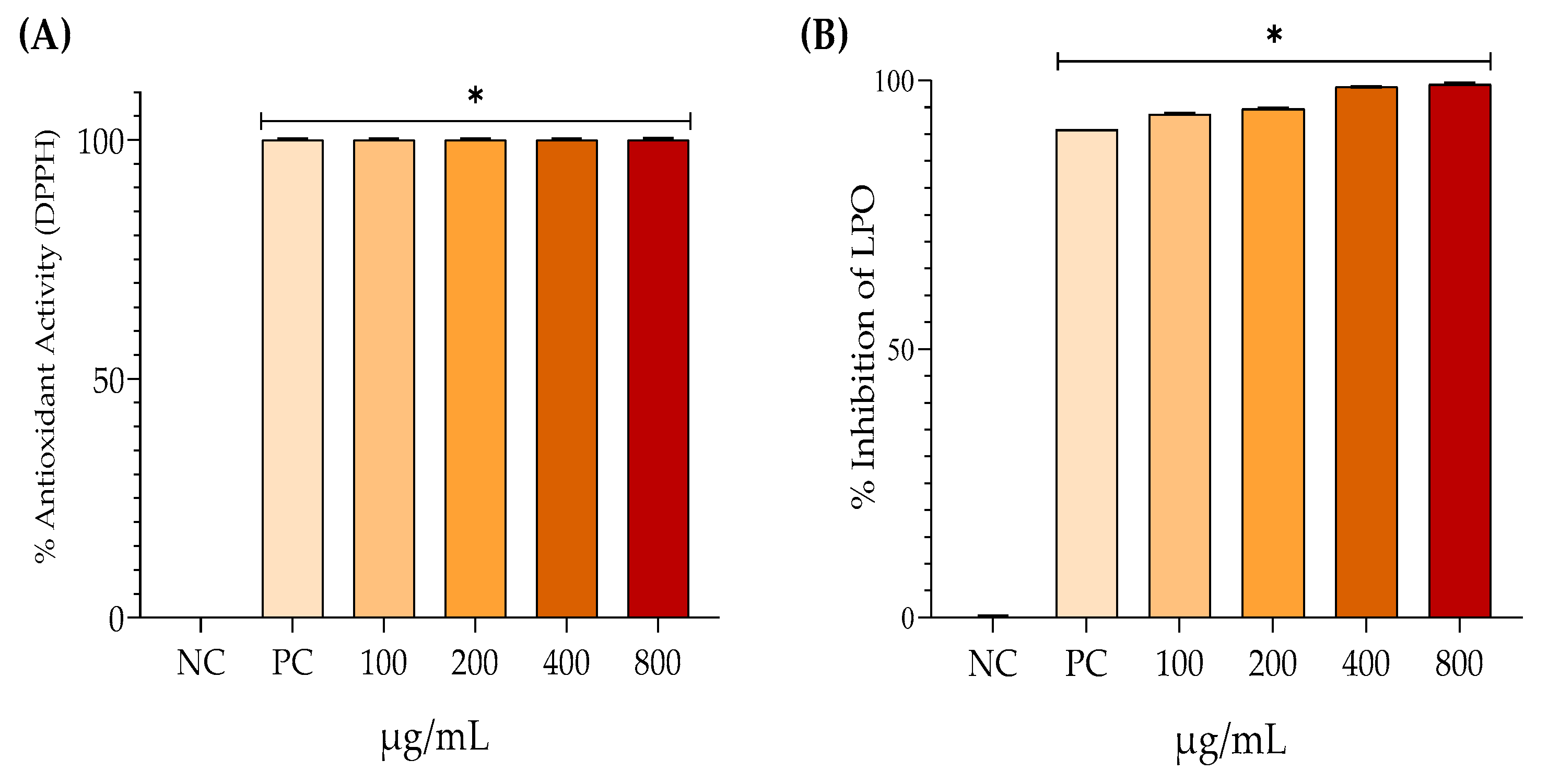

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.6.1. Inhibition of Lipoperoxidation

2.6.2. DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl Radical Scavenging)

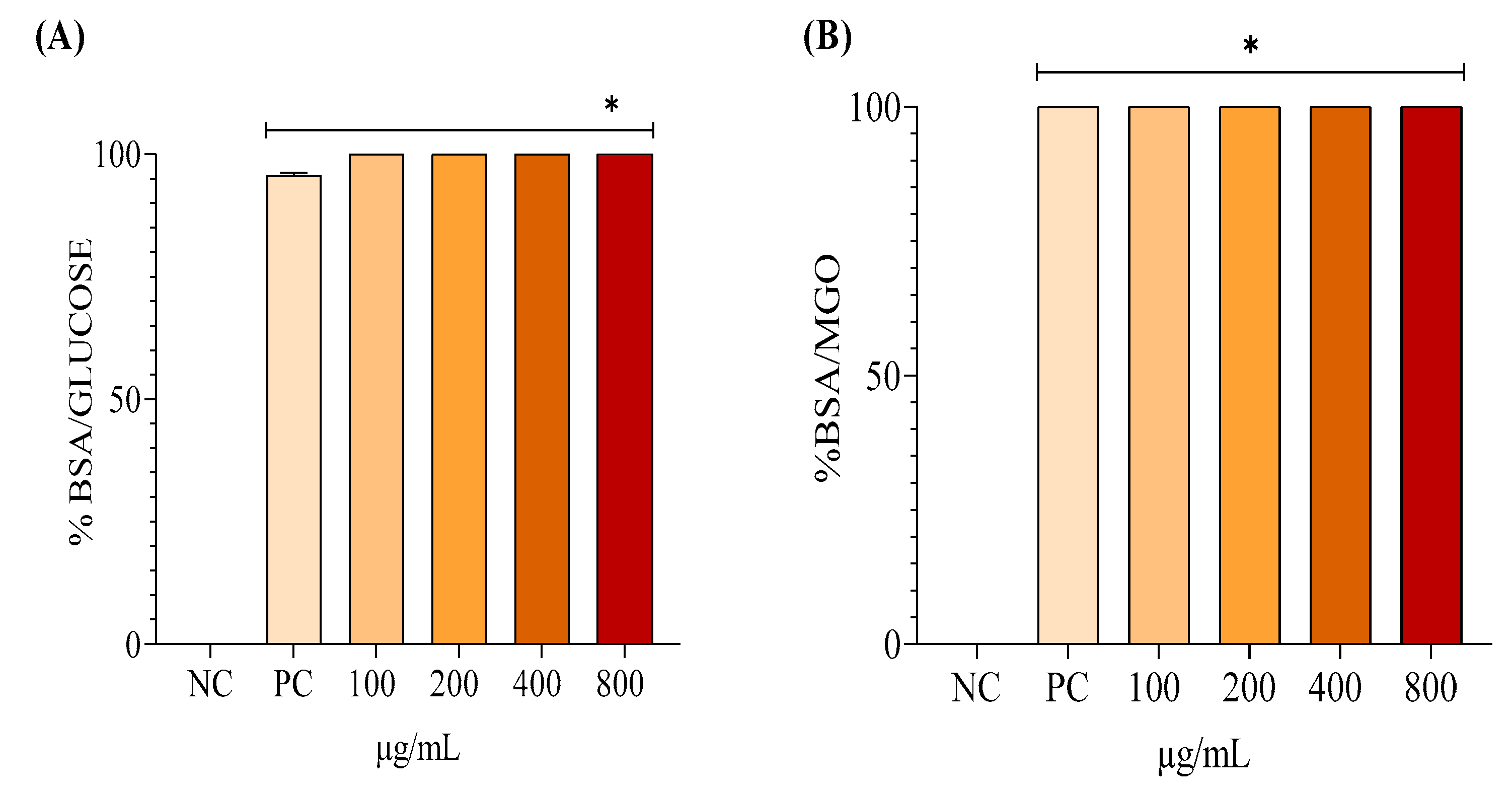

2.7. Antiglycation Activity

2.7.1. Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)/Glucose System

2.7.2. BSA/MGO System

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phytochemical Characterization

3.2. Cell Viability

3.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.5. Antiglycant Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- EHAC shows promise as an extract for creating a new plant-based therapeutic treatment for diseases associated with oxidative stress and inflammation. As a result, additional studies will be carried out to verify these effects in living organisms.

- (2)

- The development of a phytotherapeutic product based on EHAC, by adding value to a plant species from the Cerrado, may contribute to sustainable development and the preservation of this important Brazilian biome, which is currently facing intensive deforestation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martemucci, G.; Costagliola, C.; Mariano, M.; D'Andrea, L.; Napolitano, P.; D'Alessandro, A.G. Free Radical Properties, Source and Targets, Antioxidant Consumption and Health. Oxygen 2022, 2, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghan Shahreza, F. Oxidative Stress, Free Radicals, Kidney Disease and Plant Antioxidants. Immunopathol. Persa 2016, 3, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Tossou, M.C.B.; Rahu, N. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 7432797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, K.; Jung, T.; Höhn, A.; Weber, D.; Grune, T. Advanced Glycation End Products and Oxidative Stress in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justino, A.B.; Franco, R.R.; Silva, H.C.G.; Saraiva, A.L.; Sousa, R.M.F.; Espindola, F.S. Procyanidins of Annona Crassiflora Fruit Peel Inhibited Glycation, Lipid Peroxidation and Protein-Bound Carbonyls, with Protective Effects on Glycated Catalase. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.D.; Carneiro, F.M.; Fernandes, A.S.; Morais, J.M.; Borges, L.L.; Chen-Chen, L.; Almeida, L.M.; Bailão, E.F.L.C. Toxic Potential of Cerrado Plants on Different Organisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, P.; Marslin, G.; Siram, K.; Beerhues, L.; Franklin, G. Elicitation as a Tool to Improve the Profiles of High-Value Secondary Metabolites and Pharmacological Properties of Hypericum perforatum. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Mariateresa, O.; Torello, G.; Russo, M. Oxidative Stress: The Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.; Nobre, M.S.C.; Albino, S.L.; Lócio, L.L.; Nascimento, A.P.S.; Scotti, L.; Scotti, M.T.; Oshiro-Junior, J.A.; Lima, M.C.A.; Mendonça-Junior, F.J.B. Secondary Metabolites with Antioxidant Activities for the Putative Treatment of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Experimental Evidences. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5642029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T.M.; Sousa, P.; Campos, C.; Perestrelo, R.; Câmara, J.S. Secondary Bioactive Metabolites from Foods of Plant Origin as Theravention Agents against Neurodegenerative Disorders. Foods 2024, 13, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, H.S.; Pastore, G.M. Araticum (Annona Crassiflora Mart.) as a Source of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds for Food and Non-Food Purposes: A Comprehensive Review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 450–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa Oliveira, C.; De Matos, N.A.; De Carvalho Veloso, C.; Lage, G.A.; Pimenta, L.P.S.; Duarte, I.D.G.; Romero, T.R.L.; Klein, A.; De Castro Perez, A. Anti-Inflammatory and Antinociceptive Properties of the Hydroalcoholic Fractions from the Leaves of Annona Crassiflora Mart. in Mice. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar, J.B.; Ferri, P.H.; Chen-Chen, L. Genotoxicity Investigation of Araticum (Annona Crassiflora Mart., 1841, Annonaceae) Using SOS-Inductest and Ames Test. Braz. J. Biol. 2011, 71, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar, J.B.; Ferreira, F.L.; Ferri, P.H.; Guillo, L.A.; Chen Chen, L. Assessment of the Mutagenic, Antimutagenic and Cytotoxic Activities of Ethanolic Extract of Araticum (Annona Crassiflora Mart. 1841) by Micronucleus Test in Mice. Braz. J. Biol. 2008, 68, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, H.S.; Borsoi, F.T.; Andrade, A.C.; Pastore, G.M.; Marostica Junior, M.R. Scientific Advances in the Last Decade on the Recovery, Characterization, and Functionality of Bioactive Compounds from the Araticum Fruit (Annona crassiflora Mart.). Plants 2023, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailão, E.; Devilla, I.; Da Conceição, E.; Borges, L. Bioactive Compounds Found in Brazilian Cerrado Fruits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 23760–23783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaie, L.; Bamdad, S.; Delazar, A.; Nazemiyeh, H. Antioxidant, Total Phenol and Flavonoid Contents of Two Pedicularis L. Species from Eastern Azarbaijan, Iran. BioImpacts 2012, 2, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The Determination of Flavonoid Contents in Mulberry and Their Scavenging Effects on Superoxide Radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Tang, A.; Pi, L.; Xiao, L.; Ao, X.; Pu, Y.; Wang, R. Determination of Kynurenine in Serum by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with on-Column Fluorescence Derivatization. Clin. Chim. Acta 2008, 389, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboy, M.S.; Marcarini, J.C.; Luiz, R.C.; Barros, I.B.; Ferreira, D.T.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Mantovani, M.S. In Vitro Evaluation of the Genotoxic Activity and Apoptosis Induction of the Extracts of Roots and Leaves from the Medicinal Plant Coccoloba Mollis (Polygonaceae). J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-H. Antitumor Efficacy of Lidamycin on Hepatoma and Active Moiety of Its Molecule. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Libera, A.M.M.P.; Birgel, E.H.; Kitamura, S.S.; Rosenfeld, A.M.F.; Mori, E.; Gomes, C.D.O.M.-S.; Araújo, W.P.D. Macrófagos Lácteos de Búfalas Hígidas: Avaliações da Fagocitose, Espraiamento e Liberação de H2O2. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2006, 43, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azedo, M.R.; Blagitz, M.G.; Souza, F.N.; Benesi, F.J.; Della Libera, A.M.M.P. Avaliação Funcional de Monócitos de Bovinos Naturalmente Infectados pelo Vírus da Leucose Bovina. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2011, 63, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.C.; Sousa-e-Silva, M.C.C.; Borelli, P.; Curi, R.; Cury, Y. Crotalus durissus terrificus snake venom regulates macrophage metabolism and function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001, 70, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento Júnior, B.J.; Santos, A.M.T.; Souza, A.T.; Santos, E.O.; Xavier, M.R.; Mendes, R.L.; Amorim, E.L.C. Estudo da ação da romã (Punica granatum L.) na cicatrização de úlceras induzidas por queimadura em dorso de língua de ratos Wistar (Rattus norvegicus). Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2016, 18, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.J.; Oldoni, T.L.C.; Alencar, S.M.; Reis, A.; Loguercio, A.D.; Grande, R.H.M. Antioxidant activity by DPPH assay of potential solutions to be applied on bleached teeth. Braz. Dent. J. 2012, 23, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starowicz, M.; Zieliński, H. Inhibition of advanced glycation end-product formation by high antioxidant-leveled spices commonly used in European cuisine. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, P.F.; Todescato, A.P.; Santos, M.d.M.C.d.; Ramos, L.F.; Menon, I.C.; Carvalho, M.O.; Vale-Oliveira, M.d.; Custódio, F.B.; Gloria, M.B.A.; Dala-Paula, B.M. Anonna crassiflora suppresses colonic carcinogenesis through its antioxidant effects, bioactive amines, and phenol content in rats. Food Res. Int. 2024, 175, 113666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.L.C.C.; Minighin, E.C.; Soares, I.I.C.; Ferreira, R.M.d.S.B.; Sousa, I.M.N.d.; Augusti, R.; Labanca, R.A.; Araújo, R.L.B.d.; Melo, J.O.F. Evaluation of the total phenolic content, antioxidative capacity, and chemical fingerprint of Annona crassiflora Mart. Bioaccessible molecules. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, H.S.; Pereira, G.A.; Pastore, G.M. Brazilian Cerrado fruit araticum (Annona crassiflora Mart.) as a potential source of natural antioxidant compounds. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 2005–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lage, G.A.; Medeiros, F.D.S.; Furtado, W.D.L.; Takahashi, J.A.; Filho, J.D.D.S.; Pimenta, L.P.S. The first report on flavonoid isolation from Annona crassiflora Mart. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz, C.R.; Silva, D.B.; Prado, L.C.D.S.; Canabrava, H.A.N.; Bispo-da-Silva, L.B. Antidiarrhoeic effect and dereplication of the aqueous extract of Annona crassiflora (Annonaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugraha, A.S.; Damayanti, Y.D.; Wangchuk, P.; Keller, P.A. Anti-Infective and Anti-Cancer Properties of the Annona Species: Their Ethnomedicinal Uses, Alkaloid Diversity, and Pharmacological Activities. Molecules. 2019, 24, 4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.J.D.; Cerdeira, C.D.; Chavasco, J.M.; Cintra, A.B.P.; Silva, C.B.P.D.; Mendonça, A.N.D.; Ishikawa, T.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Chavasco, J.K. In vitro screening antibacterial activity of Bidens pilosa Linné and Annona crassiflora Mart. against oxacillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ORSA) from the aerial environment at the dental clinic. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. S. Paulo 2014, 56, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, L.A.M.; Roberto-Neto, J.; Monteiro, V.G.; Lobato, C.S.S.; De Oliveira, M.A.; da Cunha, M.; D’Ávila, H.; Seabra, S.H.; Bozza, P.T.; DaMatta, R.A. Culture of mouse peritoneal macrophages with mouse serum induces lipid bodies that associate with the parasitophorous vacuole and decrease their microbicidal capacity against Toxoplasma gondii. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, D.M. Macrophage recognition of zymosan particles. J. Endotoxin Res. 2003, 9, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Oliveira, C.; De Matos, N.A.; De Carvalho Veloso, C.; Lage, G.A.; Pimenta, L.P.S.; Duarte, I.D.G.; Romero, T.R.L.; Klein, A.; De Castro Perez, A. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties of the hydroalcoholic fractions from the leaves of Annona crassiflora Mart. in mice. Inflammopharmacol. 2019, 27, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Ballester, I.; López-Posadas, R.; Suárez, M.D.; Zarzuelo, A.; Martínez-Augustin, O.; Medina, F.S.D. Effects of flavonoids and other polyphenols on inflammation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, Q.; Yao, Q.; Xu, B.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Tu, C. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates liver inflammation and fibrosis by regulating hepatic macrophages activation and polarization in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-F.; Chen, G.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Shen, C.-K.; Lu, D.-Y.; Yang, L.-Y.; Chen, J.-H.; Yeh, W.-L. Regulatory effects of quercetin on M1/M2 macrophage polarization and oxidative/antioxidative balance. Nutrients 2021, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassiri-Asl, M.; Nikfarjam, B.A.; Adineh, M.; Hajiali, F. Treatment with Rutin - A Therapeutic Strategy for Neutrophil-Mediated Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases. J. Pharmacopuncture 2017, 20, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonato, E.F. Capacidade Antioxidante in Vitro e Efeito Hepatoprotetor de Umbu (Spondias Tuberosa Arr. Cam.) Em Resposta Ao Estresse Oxidativo Induzido Por Tetracloreto de Carbono, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, 2017.

- Silva, M.A.D.; Silva, G.A.D.; Marques, M.J.; Bastos, R.G.; Silva, A.F.D.; Rosa, C.P.; Espuri, P.F. Triagem Fitoquímica, Atividade Antioxidante e Leishmanicida Do Extrato Hidroetanólico 70% (v/v) e Das Frações Obtidas de (Annona Crassiflora Mart.). Rev. Fitos 2017, 10, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, A.W.; Haenen, G.R.M.M.; Bast, A. Health Effects of Quercetin: From Antioxidant to Nutraceutical. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 585, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, R.M.; Costa, M.M.; Martins, D.B.; França, R.T.; Schmatz, R.; Graça, D.L.; Duarte, M.M.M.F.; Danesi, C.C.; Mazzanti, C.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Paim, F.C.; Palma, H.E.; Abdala, F.H.; Stefanello, N.; Zimpel, C.K.; Felin, D.V.; Lopes, S.T.A. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Quercetin in Functional and Morphological Alterations in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 95, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, E.; Mazzi, L.; Terzuoli, G.; Bonechi, C.; Iacoponi, F.; Martini, S.; Rossi, C.; Collodel, G. Effect of Quercetin, Rutin, Naringenin and Epicatechin on Lipid Peroxidation Induced in Human Sperm. Reprod. Toxicol. 2012, 34, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, M.; Lecomte, J.; Villeneuve, P. Evaluation of the Ability of Antioxidants to Counteract Lipid Oxidation: Existing Methods, New Trends and Challenges. Prog. Lipid Res. 2007, 46, 244–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.P.C. Frações Enriquecidas Com Proantocianidinas Da Casca Do Fruto Da Annona Crassiflora Com Propriedades Antioxidante e Antiglicante e Potencial Inibitório Contra Hidrolases Glicosídicas. Master's Thesis, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.; Ahmad, H.; Ahmad, B. Anti-Glycation and Anti-Oxidation Properties of Capsicum Frutescens and Curcuma Longa Fruits: Possible Role in Prevention of Diabetic Complication. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 27, 1359–1362. [Google Scholar]

| Secondary Metabolites | Quantity |

| Total phenols | 23.08 ± 1.58 EAG |

| Flavonoids | 2.27 ± 0.08 EAQ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).