1. Introduction

Let

X be an

design matrix and let

be an

n-dimensional response. Consider the following standard linear regression model

where

is a noise term. The popular model focused on sparsity assumption of the regression vector. The Lasso [

2] (Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) is among the most popular procedures for estimating the unknown sparse regression vector in a high-dimensional linear model. Lasso is formulated as an

-penalized regression problem as follows:

where

is a regularization parameter and

(resp.

) is the

(resp.

) norm. Here, we consider the case where the design matrix

X contains missing data. Missing data is prevalent and inevitable, which affects not only the representativeness and quality of data but also the results of Lasso regression. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a method applicable to process missing data. HMLasso [

1] was proposed to effectively address this issue and is formulated as follows:

where ⊙ is Hadamard product,

is Frobenius norm,

is defined using

X (see

Section 2 for details) and

(i.e.,

is the solution to problem (

3)). It is known that problem (4) can be equivalently written as Lasso (

2), and in the literature dedicated to sparse regression the most encountered algorithm is the proximal gradient method when dealing with a sum of two convex functions. Therefore, the key to solving HMLasso is to consider how fast and accurately problem (

3) can be solved.

To deal with this challenge, we consider two structural results on the HMlasso problem. The first, we show that the gradient of the objective function of (

3) is Lipschitz continuous; the second, we show that the objective function of (

3) is strongly convex. These results guarantee that accelerated algorithms for strongly convex functions can be applied to solve (

3). Finally, we conduct numerical experiments on the real data considered in [

1]. The numerical results show that the accelerated algorithm for strongly convex functions is effective for solving problem (

3).

2. Preliminaries

This section reviews basic definitions, facts, and notation that will be used throughout the paper.

For two matrices

, their Hadamard product

is defined by

The Frobenius inner product is defined by

. The Frobenius norm of

A is defined by

denotes the set of symmetric matrices of size

. We write

(resp.

) to denote that

is positive semidefinite (resp. positive definite).

denotes the set of positive semidefinite matrices.

Let

. The indicator function

of

is defined by

Let

be a proper and convex function. The proximal mapping

of

f is defined by

Let

. Then there exist a diagonal matrix

and a

orthogonal matrix

U such that

. Let

be the matric projection from

onto

. Then, the following holds (see for example [

3], [Example 29.31], [

4] [Theorem 6.3]):

where

is the diagonal matrix obtaind from

by setting the negative entries to 0.

Let

be a design matrix. Set

and let

be the number of elements of

. We define matricies

and

W as follows:

Let

and let

be a differentiable function. The gradient

of

h is said to be

L-Lipschitz continuous if

This condition is often called

L-smoothness in the literature. Let

be

L-smooth on

, Then, we can upper bound the function

h as

( see for example [

5] [Theorem 5.8], [

6] [Theorem A.1]).

Let

and let

.

g is said to be

-strongly convex if for each

and

, we have

Suppose that

g is

-strongly convex and differentiable. Then (

9) is equivalent to the following condition:

3. Main Results

In this section, we present two structural results on the HMlasso problem (

3).

Define

. In this case, the gradient

of

f is described as the following:

(see [

1]).

3.1. Lipschitz continuity

The first structural result deals with the gradient of the objective function in (

3). We show the Lipschitz continuity of

.

Lemma 1. The gradient of f is Lipschitz continuous and its Lipschitz constant is .

Proof.

On the other hand,

This implies

where the last inequality follows from

for any

j and

k. Hence

□

3.2. Strong monotonicity

We next consider the strong monotonicity of f. This is our second result.

Lemma 2. f is -strongly convex.

Proof. We show (

10) with constant

. Let

.

where the second to last inequality follows from

for any

j and

k. This implies that

f is

-strongly convex. □

Remark 1. From Lemmas 1 and 2, the objective function of (3) is strongly convex and has Lipschitz gradient. It should be noted that we can guarantee faster convergence than just on regular convex function is if we know the objective function is strongly convex and it is smooth (see for example [6]).

4. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we consider a strongly convex variant of FISTA [

6] [Algorithm 19] to solve problem (

3).

4.1. Strongly convex FISTA

Let

be an

L-smooth and

-strongly convex function with

, and let

be a convex function with

. We consider the problem of minimizing sum of

f and

h:

In this setting, forward-backward splitting strategies were introduced as classical methods for solving (

12). In the context of acceleration methods, the fast iterative shrinkage threshold algorithm (FISTA) was introduced by Beck and Teboulle [

7] using the idea of forward-backward splitting. This topc is addressed in many references, and we refer to [

3,

5,

6].

Here, we focus on the following strongly convex variant of FISTA involving backtracking investigated in [

6].

|

Algorithm 1: Strongly convex FISTA [6] [Algorithm 19] |

-

Input:

An initial point , and initial estimate . - 1:

Initialize, , and some . - 2:

fordo

- 3:

- 4:

while do

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

set and

- 8:

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

if holds then

- 12:

- 13:

else

- 14:

- 15:

end if

- 16:

end while

- 17:

end for -

Output:

An approximate solution

|

Remark 2.

We demonstrate how strongly convex FISTA can be applied to (3). Set

In this case, problem (3) is the special instanse of problem (12). The gradient can be computed by (11). Moreover, the proximal mapping is (see for example [3], Example 12.25) and hence the computation in the algorithm is simple.

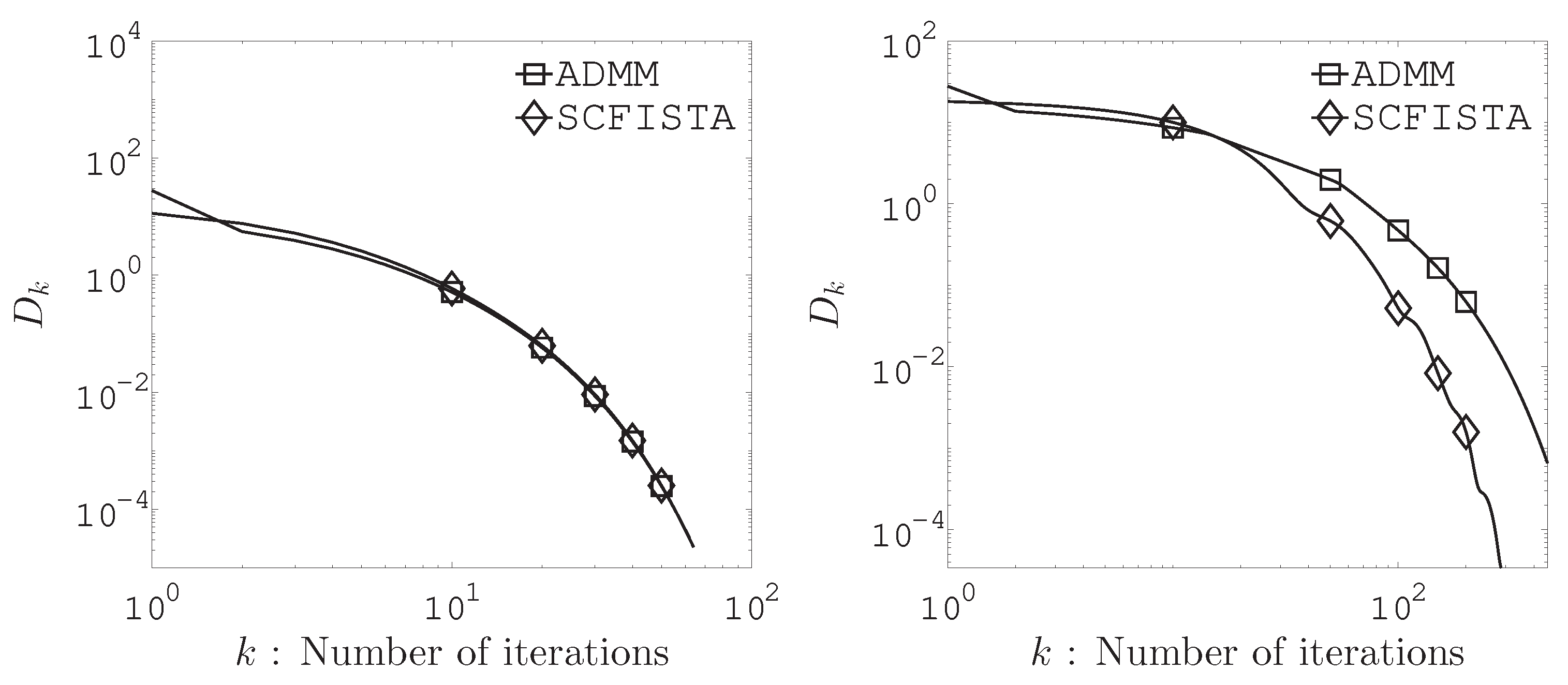

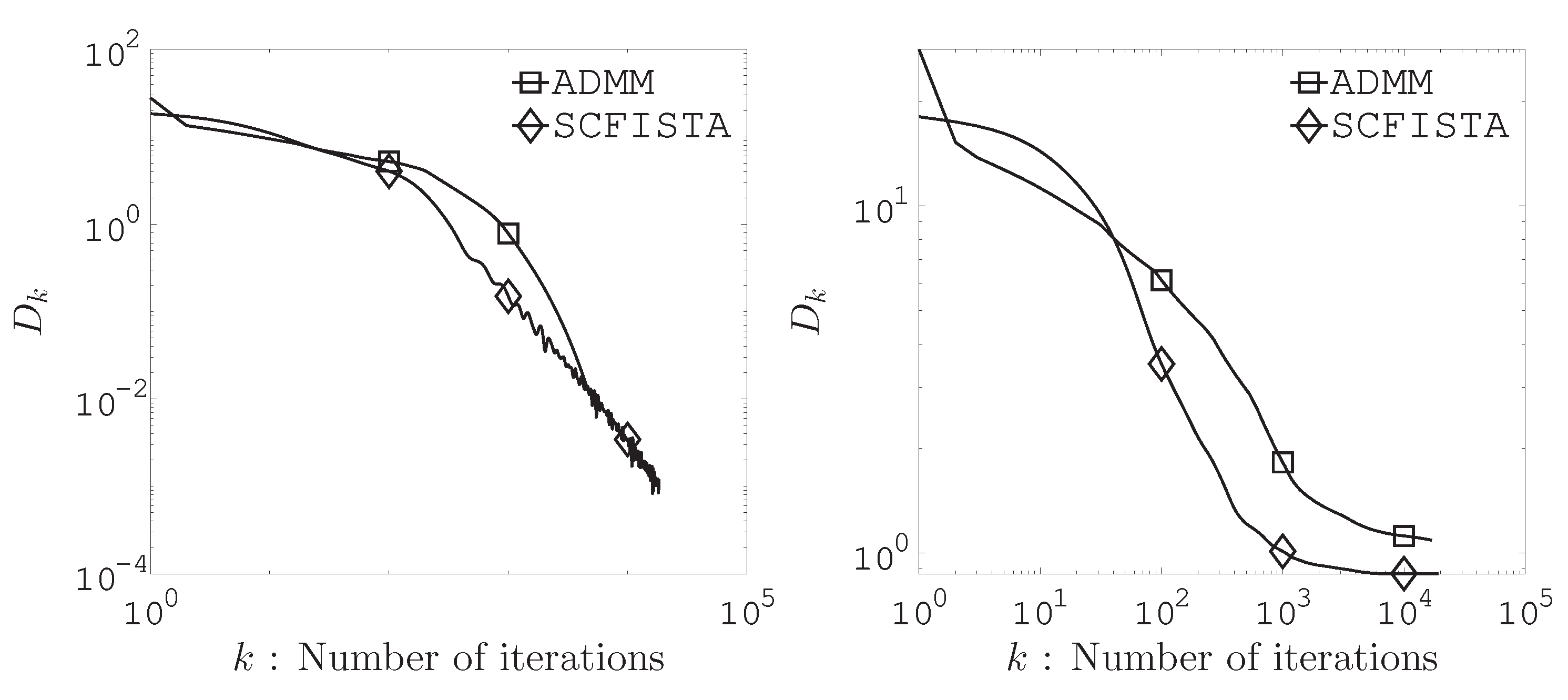

4.2. Residential Building Dataset

We compared the performance of HMLasso (

3) with the strongly convex FISTA (SCFISTA) and the alternating direction multiplier method (ADMM) used in [

6]. All experiments are conducted on a PC with Apple M1 Max CPU and 32GB RAM. Methods are implemented with MATLAB (R2025a).

The numerical experiment uses actual residential building dataset from the UCI Data Repository

1. The data consisted of

samples and

variables. We set the average missing rates to

,

,

and

. As choices for

,

and

occuring in algorithm, we let

,

and

. We chose 10 random initial points

(

) and all entries at the initial point are defined from a standard normal distribution. Figures demonstrate the following function

where

denotes the solution obtained by cvx

2 and

is the sequence generated by

and each of SCFISTA and ADMM.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the computation results of the relation between the distance to a solution and iteration number. As we can see from these figures, SCFISTA and ADMM converge to the solution as the number of iterations increases. Furthermore, we found it more effective to solve the HMLasso problem using the acceleration algorithm for strongly convex functions.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we present two structural results on the HMlasso problem, covering Lipschitz continuity of the gradient of the objective function and strong convexity of the objective function. These results allow existing acceleration algorithms for strongly convex functions to be applied to solve the HMLasso problem. Our numerical experiments suggest that accelerated algorithms for strongly convex functions are computationally attractive.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Writing - original draft, Shin-ya Matsushita; Software, Sasaki Hiromu. All authors have read andagreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number 23K03235.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Takayasu Yamaguchi of Akita Prefectural University for providing the initial inspiration for this research. This work was supported by the Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences, an International Joint Usage/Research Center located in Kyoto University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Takada, M.; Fujisawa, H.; Nishikawa, T. HMLasso: Lasso with High Missing Rate. Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI) 2019, 3541–3547. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. Stat. Methodol. 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces, 2nd ed.; Springer: CMS Books in Mathematics, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante, R.; Raydan, M. Alternating Projection Methods; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. First-order Methods in Optimization; SIAM: MOS-SIAM Series on Optimization, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- d’Aspremont, A.; Scieur, D.; Taylor, A. Acceleration Methods; Now Publishers: Fundations and Trends in Optimizaion, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.; Teboulle, M. A fast iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems. SIAM J. Imag. Sci., 2009, 2, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).