Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

16 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Penalized weighted score function method

3. Statistical properties

- (A1)

- There exists a positive constant such that .

- (A2)

- The satisfy that , and for .

- (A3)

- There exists such that

- (A4)

- Let be a convex three times differentiable function such that for all , the function satisfies for all , , where is a constant.

- (A5)

- For some integer s such that and a positive number , the follow condition holdswhere is the Hessian matrix for . Different from the restricted eigenvalue condition mentioned in Bickel et al. [25] for linear regression models, the group restricted eigenvalue condition for logistic regression is converted from the norm to the block norm for the denominator part and from the Gram matrix to the Hessian matrix for the numerator part of (9).

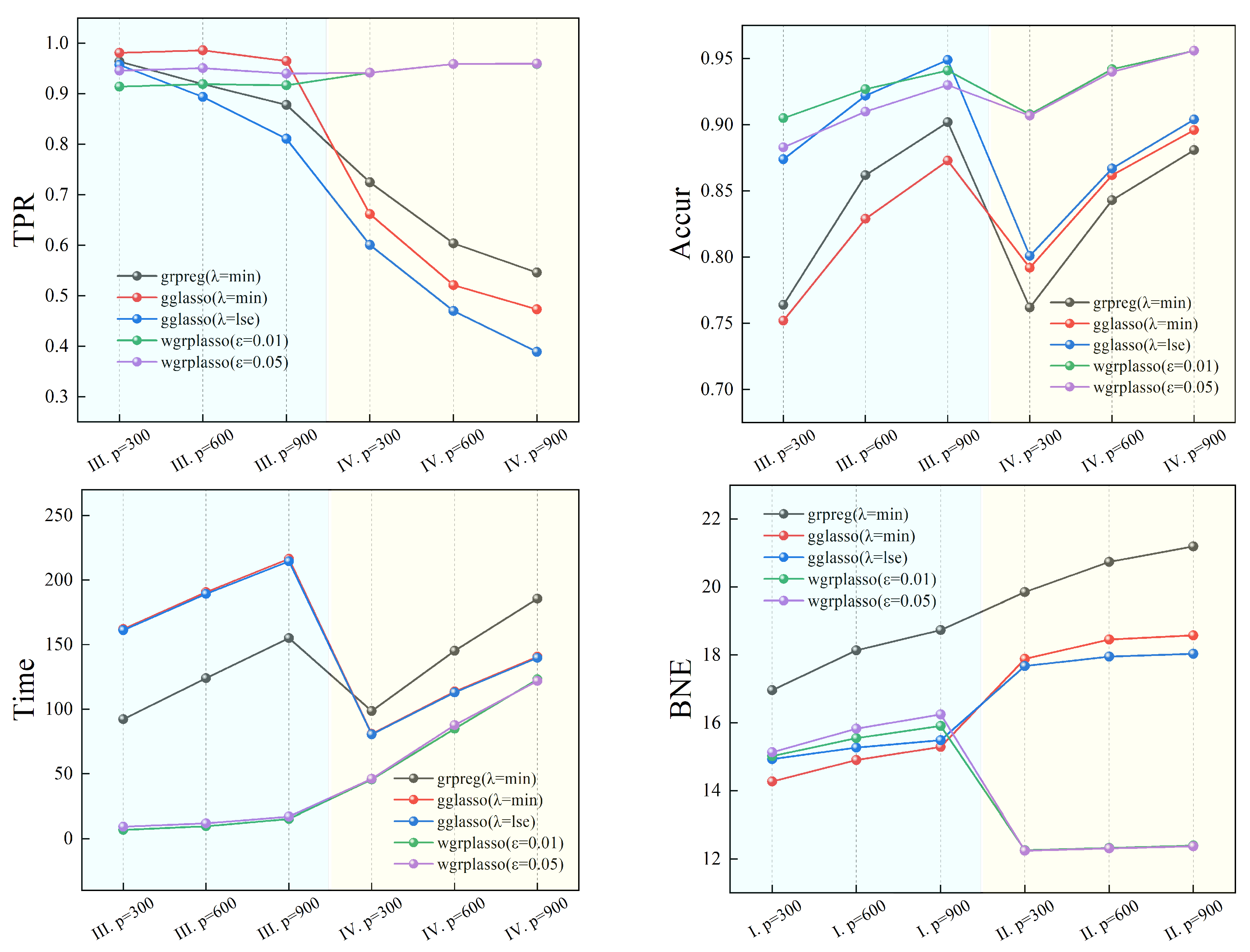

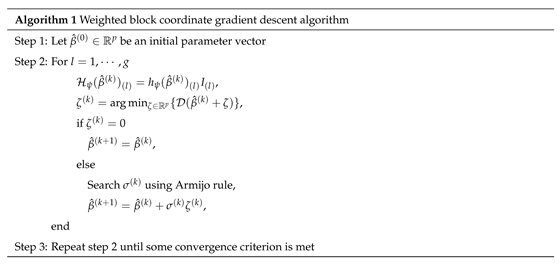

4. Weighted block coordinate descent algorithm

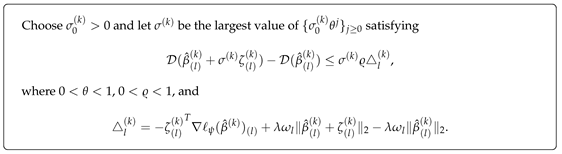

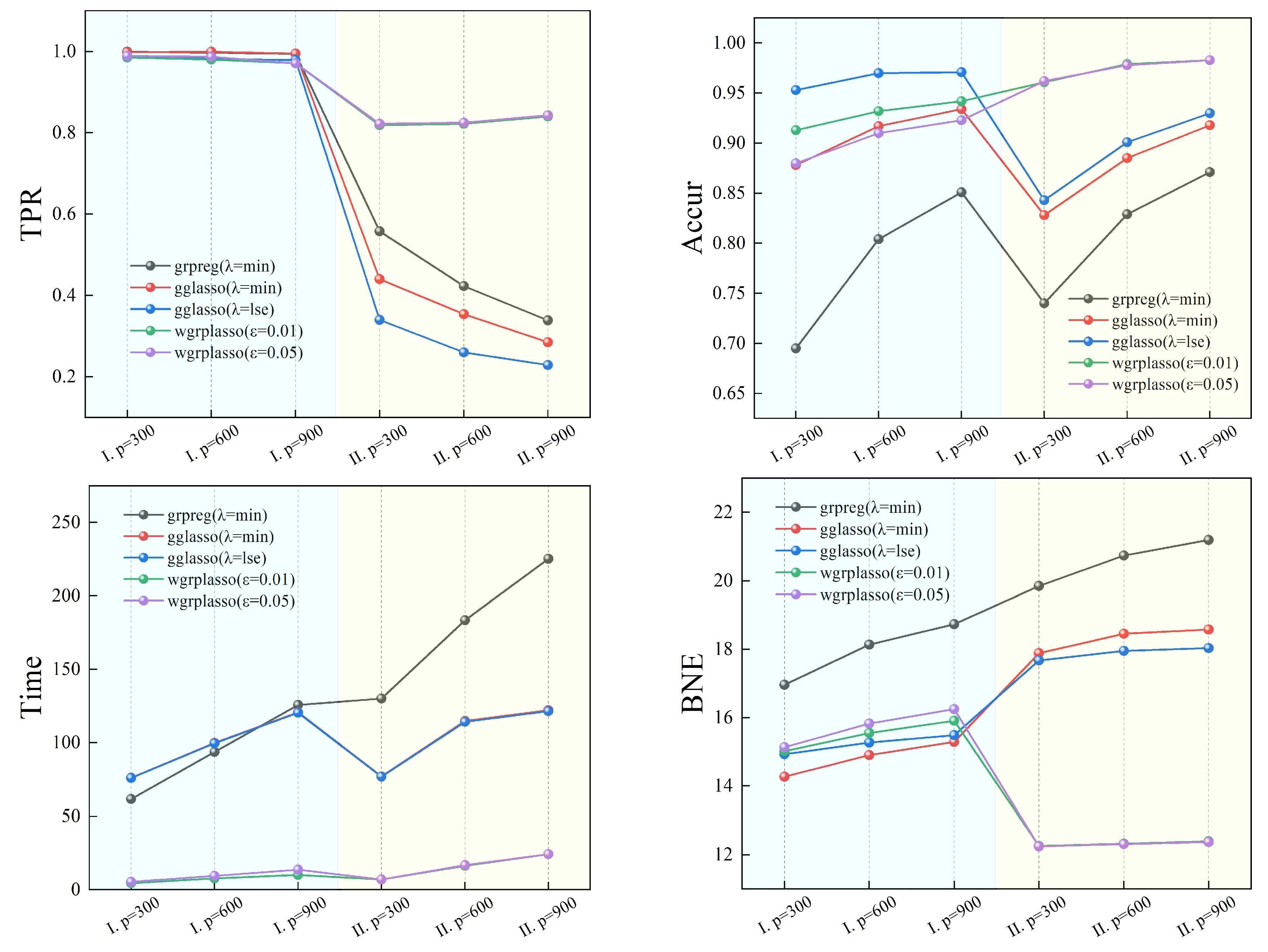

5. Simulations

- TP: the number of predicted non-zero values in the non-zero coefficient set when determining the model

- TN: the number of predicted zero values in the zero coefficient set when determining the model

- FP: the number of predicted non-zero values in the zero coefficient set when determining the model

- FN: the number of predicted zero values in the non-zero coefficient set when determining the model

- TPR: the ratio of predicted non-zero values in the non-zero coefficient set when determining the model, which is calculated by the following formulation:

- Accur: the ratio of accurate predictions when determining the model, which is calculated by the following formulation:

- Time: the running time of the algorithm.

- BNE: the block norm of the estimation error, which is calculated by the following formulation:

6. Real data

6.1. Studies on the molecular structure of Muscadine

6.2. Gene expression studies in epithelial cells of breast cancer patients

7. Conclusion

Appendix

Funding

References

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, R. Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. Journal of the American statistical Association 2001, 96, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candes, E.; Tao, T. The Dantzig selector: Statistical estimation when p is much larger than n. The Annals of Statistics 2007, 35, 2313–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.H. Nearly unbiased variable selection under minimax concave penalty. The Annals of Statistics 2010, 38, 894–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, C.H. The iterated lasso for high-dimensional logistic regression. The University of Iowa, Department of Statistics and Actuarial Sciences 2008, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bianco, A.M.; Boente, G.; Chebi, G. Penalized robust estimators in sparse logistic regression. TEST 2022, 31, 563–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovich, F.; Grinshtein, V. High-dimensional classification by sparse logistic regression. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2018, 65, 3068–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, B. Weighted Lasso estimates for sparse logistic regression: Non-asymptotic properties with measurement errors. Acta Mathematica Scientia 2021, 41, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z. Variable selection for sparse logistic regression. Metrika 2020, 83, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Lin, Y. Model selection and estimation in regression with grouped variables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 2006, 68, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.; Van De Geer, S.; Bühlmann, P. The group lasso for logistic regression. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 2008, 70, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; You, Y.; Lian, H. Convergence and sparsity of Lasso and group Lasso in high-dimensional generalized linear models. Statistical Papers 2015, 56, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazere, M.; Loubes, J.M.; Gamboa, F. Oracle Inequalities for a Group Lasso Procedure Applied to Generalized Linear Models in High Dimension. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2014, 60, 2303–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwemou, M. Non-asymptotic oracle inequalities for the Lasso and group Lasso in high dimensional logistic model. ESAIM: Probability and Statistics 2016, 20, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, S.; Pokarowski, P.; Rejchel, W.; Sołtys, A. Improving Group Lasso for high-dimensional categorical data. International Conference on Computational Science. Springer, 2023, pp. 455–470.

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, C.; Liu, X. Group Logistic Regression Models with Lp, q Regularization. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P. Convergence of a block coordinate descent method for nondifferentiable minimization. Journal of optimization theory and applications 2001, 109, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breheny, P.; Huang, J. Group descent algorithms for nonconvex penalized linear and logistic regression models with grouped predictors. Statistics and computing 2015, 25, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belloni, A.; Chernozhukov, V.; Wang, L. Square-root lasso: pivotal recovery of sparse signals via conic programming. Biometrika 2011, 98, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, F.; Lederer, J.; She, Y. The group square-root lasso: Theoretical properties and fast algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2013, 60, 1313–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, C. Consistent functional methods for logistic regression with errors in covariates. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2001, 96, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, F. Self-concordant analysis for logistic regression. Electronic Journal of Statistics 2010, 4, 384–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, C.; Meng, K.; Qin, J.; Yang, X. Group sparse optimization via lp, q regularization. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2017, 18, 960–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, P.J.; Ritov, Y.; Tsybakov, A.B. Simultaneous analysis of Lasso and Dantzig selector. The Annals of Statistics 2009, 37, 1705–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.; Yun, S. A coordinate gradient descent method for nonsmooth separable minimization. Mathematical Programming 2009, 117, 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zou, H. A fast unified algorithm for solving group-lasso penalize learning problems. Statistics and Computing 2015, 25, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.; de Las Morenas, A.; Tripathi, A.; King, C.; Kavanah, M.; Mendez, J.; Stone, M.; Slama, J.; Miller, M.; Antoine, G.; others. Gene expression in histologically normal epithelium from breast cancer patients and from cancer-free prophylactic mastectomy patients shares a similar profile. British journal of cancer 2010, 102, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhanenko, A. Berry-Esseen type estimates for large deviation probabilities. Siberian Mathematical Journal 1991, 32, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model I | |||||||

| TP | TPR | FP | Accur | Time | BNE | ||

| p=300 | grpreg(=min) | 29.97 (0.30) |

0.999 | 91.71 (20.45) |

0.694 | 75.93 | 16.963 (1.17) |

| gglasso(=min) | 29.94 (0.42) |

0.998 | 36.60 (25.76) |

0.878 | 61.59 | 14.275 (0.55) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 29.67 (1.12) |

0.989 | 13.74 (14.25) |

0.953 | 76.11 | 14.933 (0.46) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 29.55 (1.08) |

0.985 | 25.80 (8.19) |

0.912 | 4.55 | 15.021 (0.50) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 29.67 (0.94) |

0.989 | 25.80 (9.39) |

0.879 | 5.47 | 15.133 (0.56) |

|

| p=600 | grpreg(=min) | 29.91 (0.51) |

0.997 | 115.89 (27.43) |

0.807 | 99.54 | 18.136 (1.49) |

| gglasso(=min) | 29.97 (0.30) |

0.999 | 49.56 (36.29) |

0.917 | 93.64 | 14.904 (0.62) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 29.46 (1.43) |

0.982 | 17.25 (18.61) |

0.970 | 99.90 | 15.271 (0.37) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 29.40 (1.48) |

0.980 | 40.53 (12.07) |

0.931 | 7.75 | 15.553 (0.52) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 29.61 (1.25) |

0.987 | 53.97 (12.85) |

0.909 | 9.42 | 15.829 (0.61) |

|

| p=900 | grpreg(=min) | 29.82 (0.72) |

0.994 | 134.37 (32.87) |

0.851 | 120.47 | 18.736 (1.53) |

| gglasso(=min) | 29.85 (0.66) |

0.995 | 59.19 (42.77) |

0.934 | 125.79 | 15.292 (0.57) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 29.37 (1.37) |

0.979 | 25.23 (24.93) |

0.971 | 120.78 | 15.486 (0.41) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 29.13 (1.43) |

0.971 | 51.48 (12.94) |

0.942 | 10.06 | 15.907 (0.55) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 29.34 (1.32) |

0.978 | 68.55 (14.97) |

0.923 | 13.77 | 16.251 (0.62) |

|

| Model II | |||||||

| TP | TPR | FP | Accur | Time | BNE | ||

| p=300 | grpreg(=min) | 16.74 (4.27) |

0.558 | 65.19 (9.30) |

0.739 | 76.81 | 19.851 (0.82) |

| gglasso(=min) | 13.20 (5.22) |

0.440 | 35.70 (11.74) |

0.825 | 130.13 | 17.889 (0.62) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 10.20 (4.78) |

0.340 | 27.69 (11.51) |

0.842 | 77.11 | 17.676 (0.41) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 24.57 (2.58) |

0.819 | 6.24 (4.61) |

0.961 | 7.01 | 12.256 (0.54) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 24.66 (2.47) |

0.822 | 6.51 (4.75) |

0.961 | 6.95 | 12.241 (0.55) |

|

| p=600 | grpreg(=min) | 12.69 (4.28) |

0.423 | 85.35 (12.24) |

0.829 | 114.24 | 20.737 (0.76) |

| gglasso(=min) | 10.62 (4.09) |

0.354 | 49.77 (14.23) |

0.885 | 183.45 | 18.459 (0.68) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 7.80 (4.02) |

0.260 | 37.35 (13.77) |

0.901 | 114.80 | 17.952 (0.44) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 24.66 (2.91) |

0.822 | 7.50 (5.40) |

0.979 | 14.17 | 12.323 (0.43) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 24.75 (2.81) |

0.825 | 7.71 (5.33) |

0.978 | 15.17 | 12.309 (0.44) |

|

| p=900 | grpreg(=min) | 10.17 (4.53) |

0.339 | 95.97 (14.07) |

0.871 | 141.31 | 21.192 (0.78) |

| gglasso(=min) | 8.55 (4.42) |

0.285 | 52.08 (16.18) |

0.918 | 224.54 | 18.582 (0.73) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 6.87 (4.25) |

0.229 | 39.96 (14.36) |

0.930 | 142.08 | 18.038 (0.53) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 25.20 (2.70) |

0.840 | 10.77 (6.74) |

0.983 | 22.06 | 12.393 (0.56) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 25.29 (2.67) |

0.843 | 11.07 (6.59) |

0.982 | 21.83 | 12.373 (0.58) |

|

| Model III | |||||||

| TP | TPR | FP | Accur | Time | BNE | ||

| p=300 | grpreg(=min) | 28.92 (2.15) |

0.964 | 69.87 (20.50) |

0.763 | 161.17 | 18.771 (1.41) |

| gglasso(=min) | 29.43 (3.10) |

0.981 | 74.16 (29.85) |

0.751 | 92.28 | 16.155 (0.84) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 28.71 (3.82) |

0.957 | 36.66 (21.05) |

0.874 | 162.14 | 15.849 (0.52) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 27.42 (2.86) |

0.914 | 25.95 (7.98) |

0.905 | 6.86 | 15.093 (0.49) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 28.38 (2.06) |

0.946 | 33.66 (8.31) |

0.882 | 9.22 | 16.294 (0.55) |

|

| p=600 | grpreg(=min) | 27.57 (4.02) |

0.919 | 80.61 (30.38) |

0.862 | 189.25 | 19.277 (1.56) |

| gglasso(=min) | 29.58 (1.05) |

0.986 | 102.12 (41.15) |

0.829 | 124.10 | 17.521 (1.26) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 26.82 (7.21) |

0.894 | 43.86 (34.66) |

0.922 | 190.67 | 16.644 (0.58) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 27.57 (2.62) |

0.919 | 41.37 (11.08) |

0.927 | 9.60 | 16.709 (0.60) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 28.53 (1.93) |

0.951 | 52.68 (12.12) |

0.910 | 11.95 | 17.024 (0.68) |

|

| p=900 | grpreg(=min) | 26.34 (5.59) |

0.878 | 84.69 (38.07) |

0.902 | 214.50 | 19.459 (1.92) |

| gglasso(=min) | 28.95 (3.20) |

0.965 | 113.34 (49.11) |

0.873 | 155.14 | 17.835 (1.33) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 24.33 (9.68) |

0.811 | 39.99 (31.89) |

0.949 | 216.52 | 16.691 (0.46) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 27.51 (2.77) |

0.917 | 50.49 (12.26) |

0.941 | 15.23 | 16.939 (0.68) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 28.20 (2.33) |

0.940 | 61.77 (12.53) |

0.929 | 16.97 | 17.307 (0.74) |

|

| Model IV | |||||||

| TP | TPR | FP | Accur | Time | BNE | ||

| p=300 | grpreg(=min) | 21.75 (3.94) |

0.725 | 63.24 (9.34) |

0.762 | 80.51 | 23.983 (1.19) |

| gglasso(=min) | 19.86 (4.41) |

0.662 | 52.47 (9.74) |

0.791 | 98.53 | 18.512 (1.21) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 18.03 (4.58) |

0.601 | 47.82 (11.15) |

0.801 | 80.87 | 18.051 (1.11) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 28.26 (2.05) |

0.942 | 26.31 (8.76) |

0.906 | 45.56 | 14.895 (1.04) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 28.26 (2.01) |

0.942 | 26.4 (8.67) |

0.906 | 46.08 | 14.934 (1.03) |

|

| p=600 | grpreg(=min) | 18.12 (4.45) |

0.604 | 82.29 (12.32) |

0.843 | 112.95 | 24.765 (1.38) |

| gglasso(=min) | 15.63 (4.94) |

0.521 | 68.28 (12.20) |

0.862 | 145.22 | 19.121 (1.30) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 14.10 (5.07) |

0.470 | 64.11 (13.27) |

0.867 | 113.62 | 18.523 (1.14) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 28.77 (1.66) |

0.959 | 34.11 (10.02) |

0.941 | 84.97 | 15.353 (1.11) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 28.77 (1.66) |

0.959 | 34.89 (10.25) |

0.940 | 87.64 | 15.38 (1.11) |

|

| p=900 | grpreg(=min) | 16.38 (3.99) |

0.546 | 93.60 (14.46) |

0.881 | 139.78 | 25.239 (1.44) |

| gglasso(=min) | 14.19 (4.69) |

0.473 | 78.21 (13.51) |

0.896 | 185.60 | 19.309 (1.25) |

|

| gglasso(=lse) | 11.67 (4.73) |

0.389 | 67.86 (13.89) |

0.904 | 140.75 | 18.453 (1.09) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.01) | 28.77 (1.71) |

0.959 | 38.79 (12.26) |

0.956 | 123.20 | 15.780 (1.14) |

|

| wgrplasso(=0.05) | 28.80 (1.71) |

0.960 | 38.79 (11.90) |

0.956 | 121.92 | 15.827 (1.15) |

|

| wgrplasso (ϵ=0.05) |

grpreg (λ=min) |

gglasso (λ=min) |

glmnet (λ=min) |

|

| Prediction accuracy | 0.820 | 0.813 | 0.771 | 0.758 |

| Model size | 66.53 | 31.29 | 30.14 | 53.53 |

| Time | 0.69 | 3.04 | 2.70 | 2.12 |

| wgrplasso (ϵ=0.05) |

grpreg (λ=min) |

gglasso (λ=min) |

|

| Prediction error | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.71 |

| Model size | 14 | 9 | 14 |

| Selected genes | 117_at 1255_g_at 200000_s_at 200002_at 200030_s_at 200040_at 200041_s_at 200655_s_at 200661_at 200729_s_at 201040_at 201465_s_at 202707_at 211997_x_at |

201464_x_at 201465_s_at 201778_s_at 202707_at 204620_s_at 205544_s_at 211997_x_at 213280_at 217921_at |

200047_s_at 200729_s_at 200801_x_at 201465_s_at 202046_s_at 202707_at 205544_s_at 208443_x_at 211374_x_at 211997_x_a212234_at 213280_at 217921_at 220811_at |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).