Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Statistical Model and New Ridge Estimation

3. Strategy Improvements for the RE Estimator

3.1. Preliminary and Shrinkage Estimators

3.2. Modified Preliminary and Shrinkage Estimators

4. Analytical Properties

5. Some Penalizing Techniques

5.1. Ridge Estimator

5.2. LASSO Estimator

5.3. Elastic Net Estimator

5.4. SCAD Estimator

5.5. Adaptive LASSO Estimator

6. Machine Learning

6.1. Random Forest

6.2. K-Nearest Neighbors

6.3. Neural Network

7. Numerical Illustrations

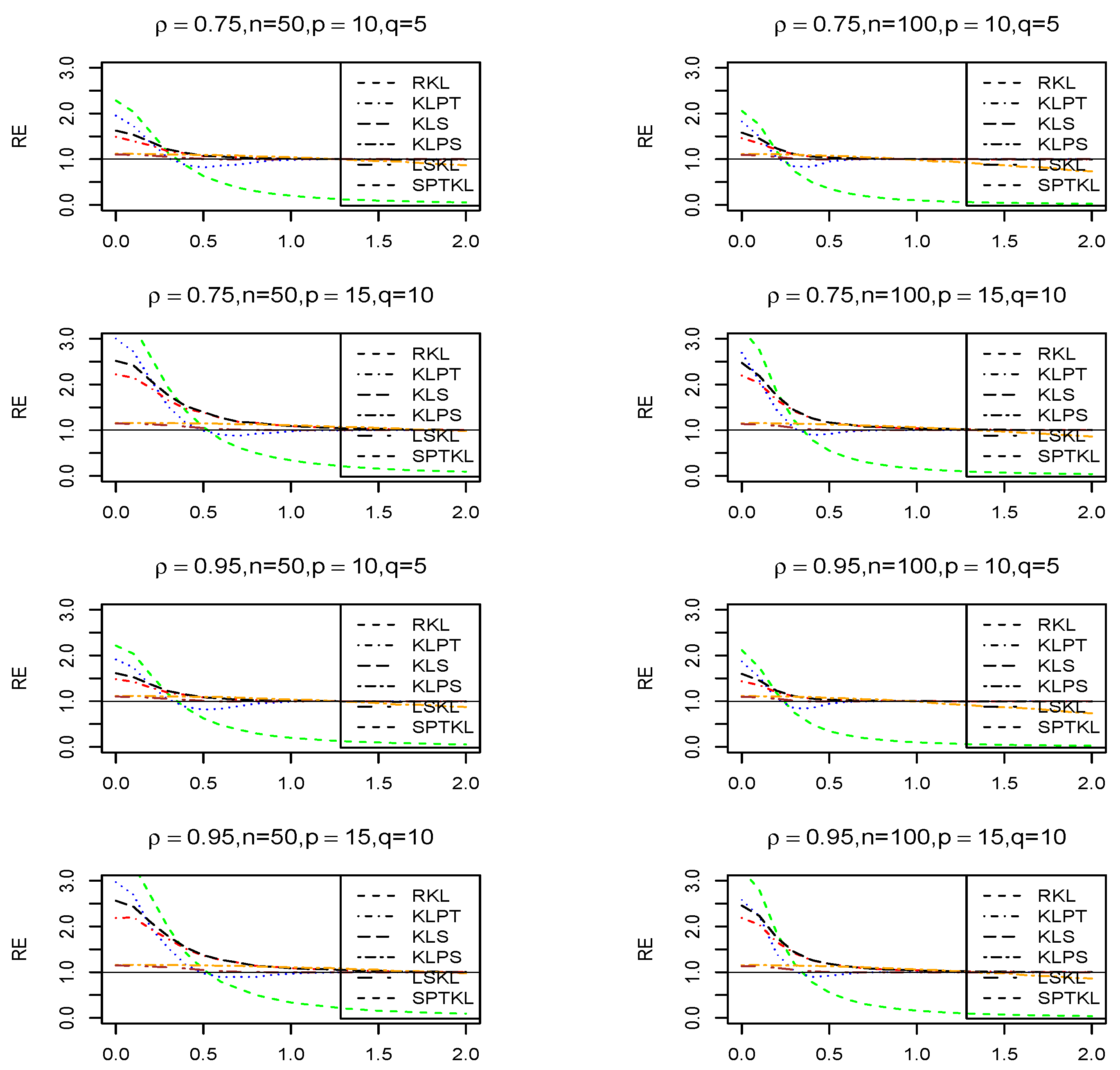

7.1. Simulation Experiments

- The sub-model estimate consistently beats the all other estimators when the null hypothesis in (3) is true or approximately true. However, its relative efficiency decreases and eventually approaches zero as increases. Moreover, all estimators outperform the regular estimator in terms of mean squared error across all values of .

- For all values of , the RE positive shrinkage estimator dominates all other estimators, except when the sub-model is true, in which case the RE sub-model and the pertest estimators outperformed it.

- The relative efficiencies exhibit a consistent pattern when the values of , and are held constant for both sample sizes used in this simulation.

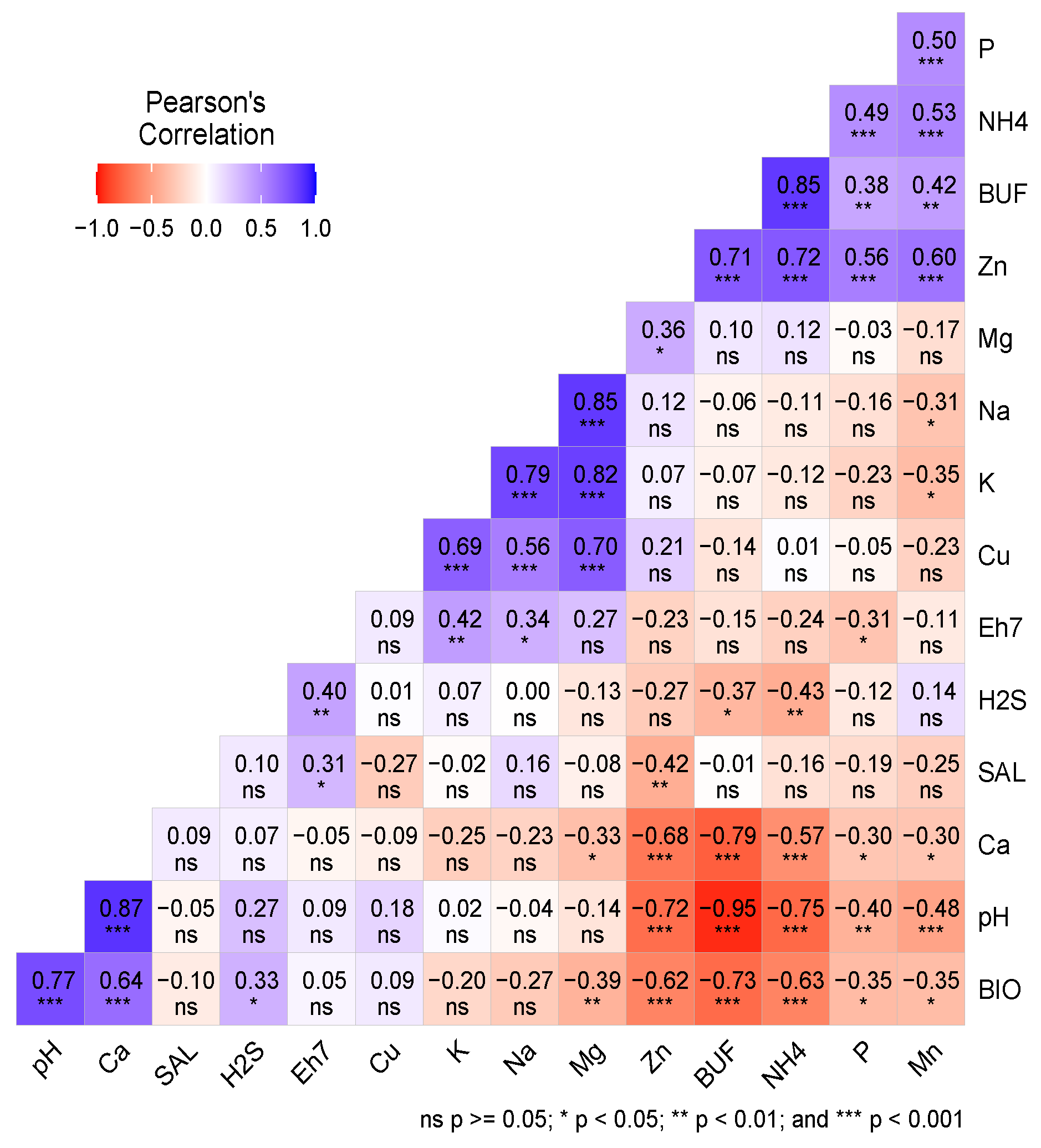

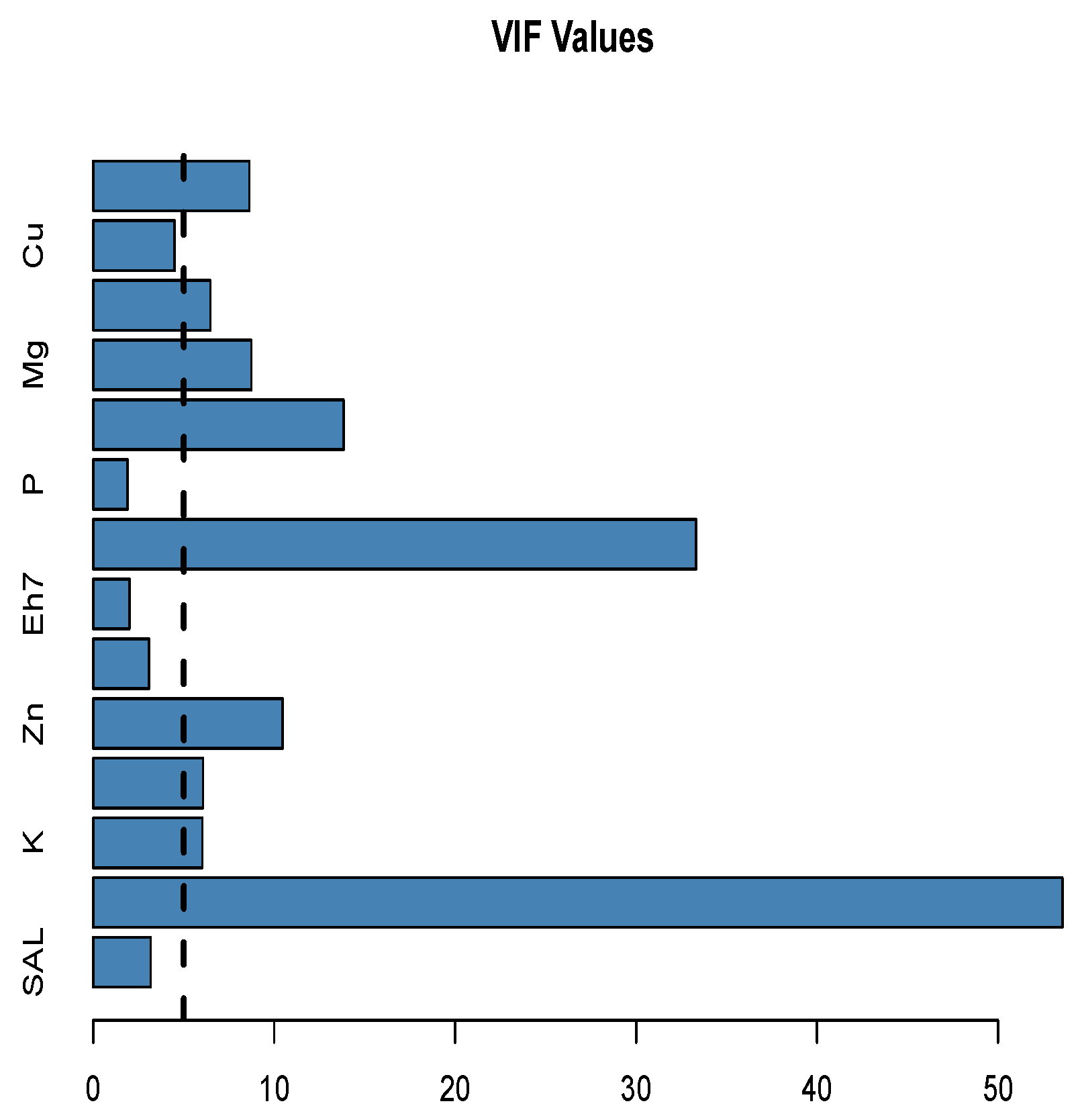

7.2. Data Examples

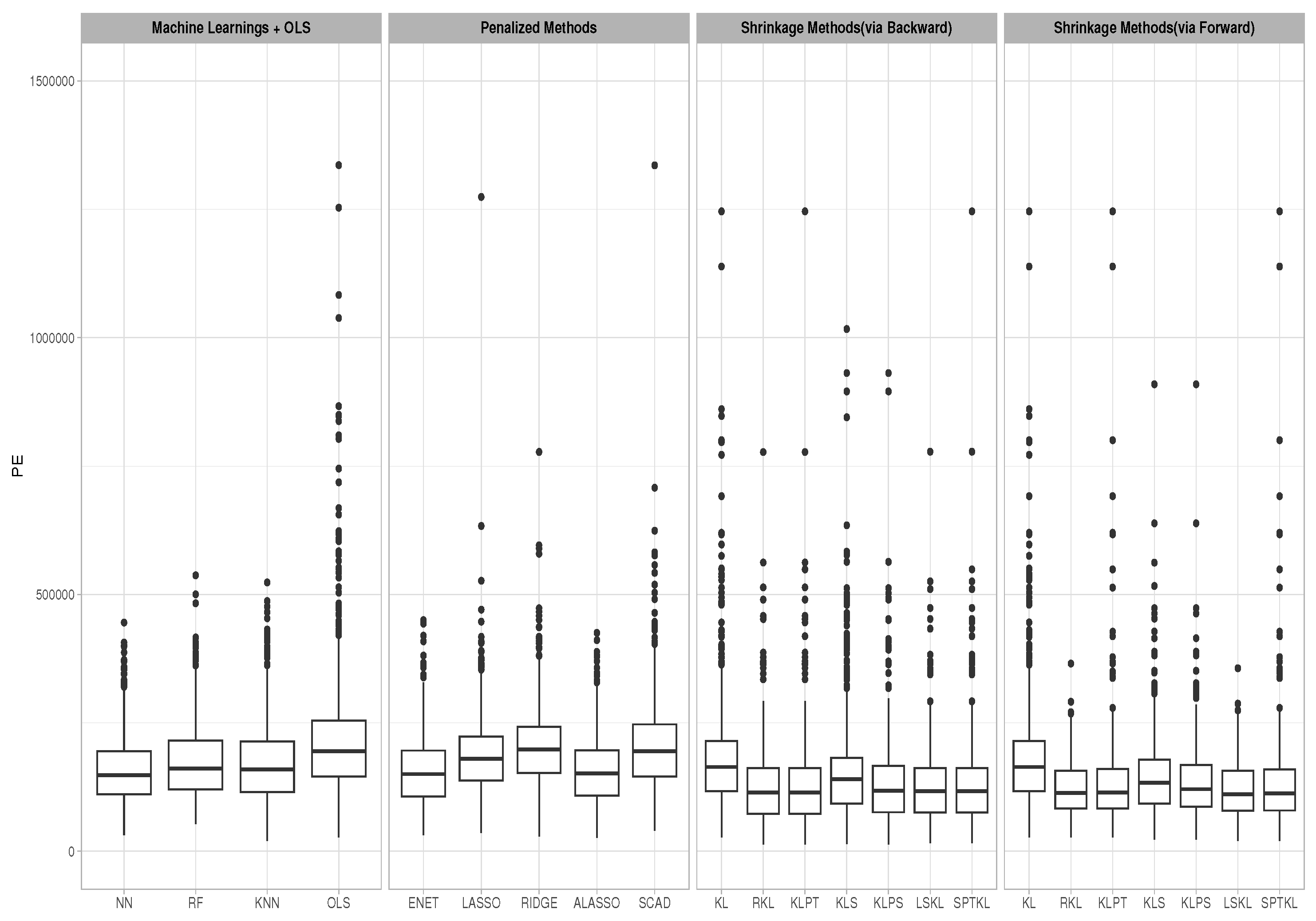

- Select with replacement a sample of size from the data set times, say .

- Partition each Sample in (1) into separate training and testing sets. The training and testing sets are divided at a ratio of 80% and 20%, respectively. Then, fit a full and sub models using the training data set, and obtain the values of all RE-type estimators.

- Evaluate the predicted response values using each estimator based on the testing data set as follows:where , , and is the matrix of other variables in the model, and is any of the proposed RE estimators.

- Find the prediction error of each estimator for each sample as follows:where

- Calculate the average prediction error of all estimators as follows:

- Finally, calculate the relative efficiency of the prediction error with respect to as follows:

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

References

- Hoerl, A. E. and Kennard, R. W. Ridge Regression: Applications to Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics1970, 12(1), pp. 69–82. [CrossRef]

- Liu Kejian. A new class of blased estimate in linear regression. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods 1993, 22(2), pp. 393–402.

- B. M. Golam Kibria, Adewale F. Lukman, . A New Ridge-Type Estimator for the Linear Regression Model: Simulations and Applications. Scientifica, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, T. A. (1944). On biases in estimation due to the use of preliminary tests of significance. Ann. Math. Statistics, 1944, 43, pp. 190–204.

- Stein, C. Inadmissibility of the usual estimator for the mean of a multivariate normal distribution. In Proceedings of the Third Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley and Los Angeles. University of California Press., 1956, 1, pp. 197–206.

- Stein, C.. An approach to the recovery of inter-block information in balanced incomplete block designs. Research Papers in Statistics, 1966, pp. 351–366.

- Al-Momani M, Riaz M, Saleh M F. Pretest and shrinkage estimation of the regression parameter vector of the marginal model with multinomial responses. Statistical Papers, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Al-Momani M. Liu-type pretest and shrinkage estimation for the conditional autoregressive model. PLOS ONE, 2023, 18(4). [CrossRef]

- Arashi M, Kibria BMG, Norouzirad M, Nadarajah S. Improved preliminary test and Stein-rule Liu estimators for the ill-conditioned elliptical linear regression model. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 2014, 126(126), pp. 53–74.

- Arashi M, Norouzirad M, Ahmed SE., Bahadir Y. Rank-based Liu Regression. Computational Statistics. 2018, 33(3), pp. 53–74.

- Yüzbaşı , Bahadır, Ahmed , S E, and Güngör, Mehmet. Improved Penalty Strategies in Linear Regression Models. REVSTAT-Statistical Journal. 2017, 15(2), pp. 251–276.

- Bahadir Y, Arashi M, Ahmed SE. Shrinkage estimation strategies in Generalised Ridge Regression Models: Low/high-dimension regime. International Statistical Review. 2020, 88(1), pp. 229–251.

- Al-Momani M, Hussein AA, Ahmed SE. Penalty and related estimation strategies in the spatial error model. Statistica Neerlandica. 2016, 71(1), pp. 4–30.

- Al-Momani, Marwan and Arashi, Mohammad. Ridge-Type Pretest and Shrinkage Estimation Strategies in Spatial Error Models with an Application to a Real Data Example. Mathematics. 2024, 12(3), 390. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Md. E. Saleh. Theory of Preliminary Test and Stein-Type Estimation with Applications. Wiley. 2006. doi:0.1002/0471773751.

- Ehsanes S A K M, Arashi M, Saleh R A, Norouzirad M. Theory of ridge regression estimation with applications. John Wiley & amp; Sons, Inc. 2019.

- Nkurunziza S, Al-Momani M, Lin EY. Shrinkage and lasso strategies in high-dimensional heteroscedastic models. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods. 2016, 45(15), pp. 4454–4470.

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B: (Methodological), 1996, 58(1), pp. 267–288.

- Zou, Hui and Hastie, Trevor. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B: (Methodological), 2005, 67(2), pp. 301–320.

- Fan, J. and Li, R. Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 2001, 96(456), pp. 1348–1360.

- Zou, H. The adaptive lasso and its oracle properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 2006, 101(476), pp. 1418–1429.

- Andy Liaw and Matthew Wiener. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News, 2002, 2(3), pp. 18–22. url: https://CRAN.R-project.org/doc/Rnews/.

- M. Revan Özkale and Selahattin Kaçiranlar. The Restricted and Unrestricted Two-Parameter Estimators. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, 2007, 36(15)(15), pp. 2707–2725. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S.E., Feryaal Ahmed, and Bahadir Yuzbasi. Post-Shrinkage Strategies in Statistical and Machine Learning for High Dimensional Data. Boca Raton : CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group. 2023.

- Ahmed S.E. Penalty, shrinkage and Pretest Strategies Variable Selection and estimation. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2014.

- Ahmed S.E. Shrinkage preliminary test estimation in multivariate normal distributions. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, 1992, 43(3-4), 177–195.

- Ho, Tin Kam. Random Decision Forests. Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, 1995, pp. 278–282. [CrossRef]

- Ho, Tin Kam. The random subspace method for constructing decision forests. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 1998, 20(8), pp. 832–844. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L . Random Forests. Machine Learning, 2001, 45, pp. 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Liaw, Andy and Wiener, Matthew . Classification and Regression by Random Forest. Forest, 2001, 23.

- Fix, E. and Hodges, J.L. Discriminatory Analysis, Nonparametric Discrimination: Consistency Properties. Technical Report 4, USAF School of Aviation Medicine, Randolph Field., 1951.

- Cover, T. and Hart, P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 1967, 13(1), pp. 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Imandoust, Sadegh Bafandeh and Bolandraftar, Mohammad. Application of k-nearest neighbor (knn) approach for predicting economic events: Theoretical background. International journal of engineering research and applications, 2013, 3(5), pp. 605–610.

- Arif Ridho Lubis, Muharman Lubis, Al-Khowarizmi. Optimization of distance formula in K-Nearest Neighbor method. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, 2020, 9(1), pp. 326–338.

- Cunningham, Padraig and Delany, Sarah Jane. K-nearest neighbour classifiers- A tutorial. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 2021, 54(6), pp. 1–25.

- McCulloch, W.S., Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, 1943, 5(4), pp. 115–133. [CrossRef]

- Masri, SF and Nakamura, M and Chassiakos, AG and Caughey, TK. Neural network approach to detection of changes in structural parameters. Journal of engineering mechanics, 1996, 122(4), pp. 350–360.

- Eliana Angelini and Giacomo di Tollo and Andrea Roli. A neural network approach for credit risk evaluation. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 2008, 48(4), pp. 733–755.

- K.-L. Du. Clustering: A neural network approach. Neural Networks, 2010, 23(1), pp. 89–107. [CrossRef]

- Adeli, Hojjat. Neural Networks in Civil Engineering: 1989–2000. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, 2001, 16(2), pp. 126–142. [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, John O and Pantula, Sastry G and Dickey, David A. Applied regression analysis: a research tool. Springer., 1998.

- Rick Linthurst. Aeration, nitrogen, pH and salinity as factors affecting Spartina Alterniflora growth and dieback. PhD Thesis, North Carolina State University. 1979.

- Friendly, M. VisCollin: Visualizing Collinearity Diagnostics. R package version 0.1.2, 2023. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=VisCollin.

- Judge, George G., and M. E. Bock. The Statistical Implications of Pre-Test and Stein-Rule Estimators in Econometrics. North-Holland Pub. Co., 1978.

| Full Model | FW | BW/BS | Lasso | ALasso | SCAD | ELNT |

| SAL | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| pH | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| K | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Na | ||||||

| Zn | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| H2S | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Eh7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| BUF | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| P | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Ca | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Mg | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mn | ✓ | |||||

| Cu | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| NH4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Estimator | Sub.1 | Sub.2 |

| 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 1.482 | 1.473 | |

| 1.392 | 1.451 | |

| 1.263 | 1.129 | |

| 1.355 | 1.404 | |

| 1.517 | 1.453 | |

| 1.422 | 1.431 |

| Penalized Method | MLM | ||

| Ridge | 0.891 | RF | 1.039 |

| Lasso | 0.983 | KNN | 1.053 |

| ELNT | 1.170 | NN | 1.138 |

| SCAD | 0.889 | ||

| Alasso | 1.148 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).