Appendix A1. Derivations of Equations (3.12 - 3.14)

Accordingly, equation (3.12) can be expressed as:

Equivalently, from (3.9), we obtain the bias as in equation (3.13):

Also, the variance of an estimator given in (3.14) can be derived as follows:

As a result, it can be expressed as the following result with abbreviation as in (3.14):

Hence, derivation has been completed.

Thus, the hat matrix is written as follows:

Appendix B

. Asymptotic Supplement: Bias, AQDB, and ADR

This appendix provides a treatment of the asymptotic bias, Asymptotic Quadratic Distributional Bias (AQDB), and Asymptotic Distributional Risk (ADR) for the GRTK-based estimators introduced in

Section 3. Specifically, we focus on:

The baseline GRTK (FM) estimator from equation (3.4),

The ordinary Stein shrinkage estimator from equation (3.6), and

The positive-part Stein shrinkage estimator from equation (3.7).

with covariance matrix

capturing possible autocorrelation (e.g.,

). Throughout, we assume

is known (or replaced with a consistent estimator

, which suffices for the same asymptotic properties). We also assume standard regularity conditions on the kernel smoothing for

(bandwidth

and smoothness conditions as

). Under these conditions, all estimators in

Section 3 are consistent for

, and we can derive their bias, variance, and risk expansions.

Appendix B

1. Baseline GRTK (FM) Estimator

Recall that the full-model GRTK estimator may be written as

where is the partially centered response (subtracting off the estimated nonparametric component ), and is the design matrix for the parametric covariates. Let us Define

Hence . If (the decomposition after partial kernel smoothing of , then

One can show that is effectively , capturing the ridge shrinkage on the parametric coefficients. Hence,

Exact Bias. Taking expectation (condition on ) and noting for large , we get

plus small terms from the smoothing residual. Since in typical regressions and may vanish with (or remain bounded), this bias goes to zero as . The asymptotic behavior of this bias term depends crucially on how k scales with n. We can distinguish several cases:

If (remains constant or bounded as n→∞):Since , we have (, and the bias term becomes , which converges to zero at rate .

If for some : The bias term becomes , which still converges to zero when α < 1, but at a slower rate than in case (i).

If : The bias may not vanish asymptotically, potentially compromising consistency.

Therefore, for consistency of the

estimator, we require that

→ 0 as

, which is satisfied when

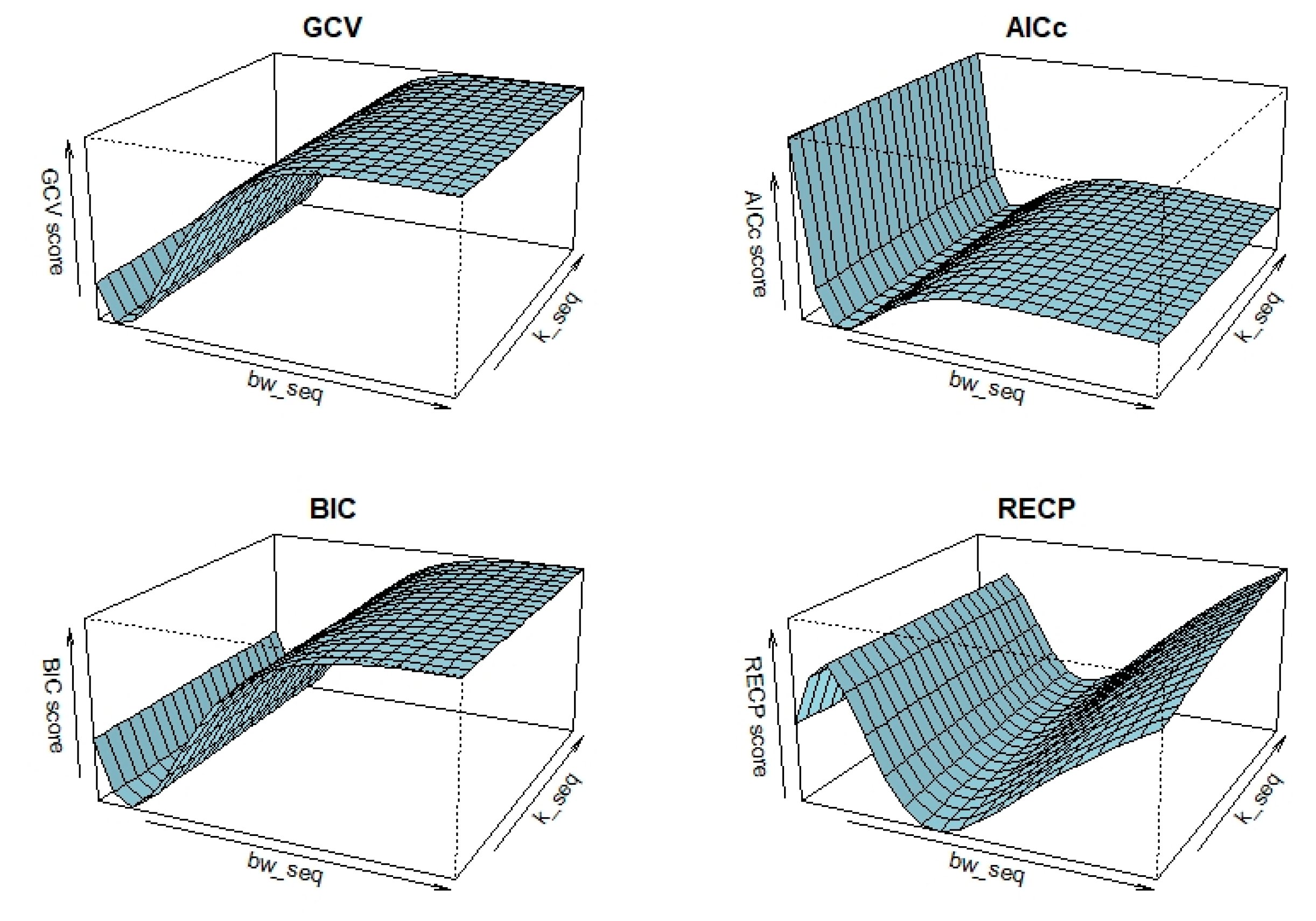

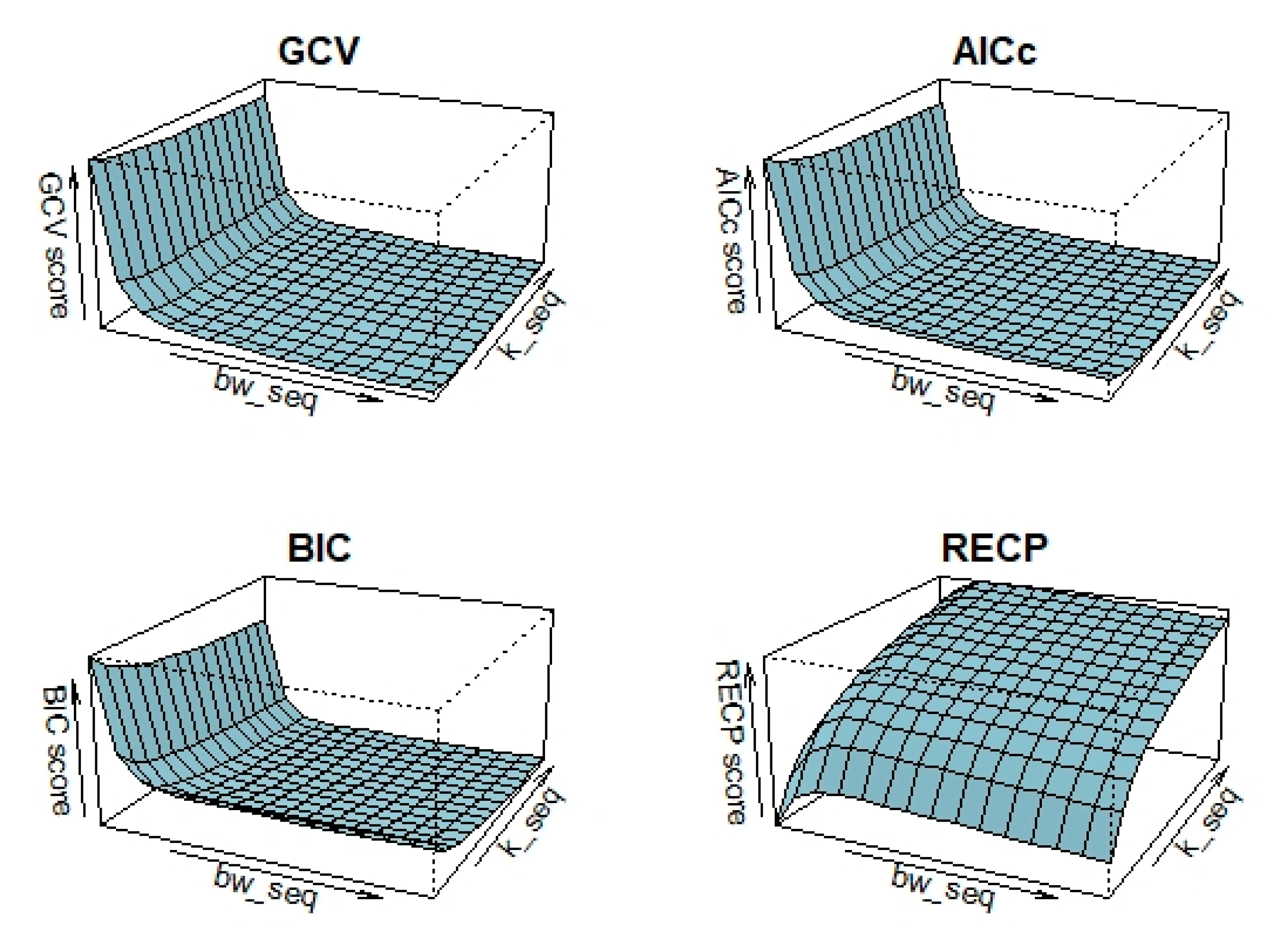

. This asymptotic requirement aligns with our parameter selection methods in

Section 4, which implicitly balance the bias-variance tradeoff by choosing appropriate

values. Hence the GRTK estimator is consistent and has

bias in finite

, shrinking

towards

. In summary:

Appendix B

2. Shrinkage Estimators

Denote by the submodel estimator, obtained by fitting the same GRTK procedure but only to a subset of regressors using BIC criterion. In practice, we set the omitted coefficients to zero. Then the ordinary Stein-type shrinkage estimator is

where is a shrinkage factor determined from the data (discussed in Subsection B3). If , no shrinkage is applied (we use the full model); if , we revert to the submodel; for , we form a weighted compromise. The positive-part shrinkage estimator is

so that negative values of (which might arise due to sampling error) are replaced by 0 to prevent over-shrinkage. Regarding the bias of shrinkage estimators,

note that itself has some bias (particularly if the omitted coefficients are not truly zero), while has the ridge bias but includes all parameters. Let and . A first-order approximation, assuming is not strongly correlated with the random errors in (, gives

Hence the bias of is approximately a linear mixture of submodel bias and fullmodel bias. In large , we typically find small, and is either (when the submodel is correct) or (if some omitted coefficients are actually nonzero) has a bigger or term. Thus, has a bias that is smaller than the submodel's in cases where .

Positive-Part Variant. For , the same expansion holds but with replaced by . This cannot exceed , so

elementwise (in a typical risk comparison sense). That is, the positive-part always improves or equals the Stein shrinkage in terms of bias magnitude, since it disallows negative .

As given in

Section 3, the distance measure

quantifies how far

is from the submodel

. A convenient choice is the squared Mahalanobis distance:

Under the "null" submodel assumption (that the omitted parameters are actually zero), follows approximately a distribution with degrees of freedom, possibly noncentral if the omitted effects are not truly zero. The main text (see eqn. (3.6)) uses in the formula for the shrinkage factor:

where . If goes negative; the positive-part approach sets . Asymptotic Distribution of . Under standard conditions (normal or asymptotically normal errors, large ):

where is a noncentrality parameter linked to how large the omitted true coefficients are. In a local-alternatives framework with for the omitted block, remains finite as . If (null case), and . If tends to be , so . This adaptivity is what drives the shrinkage phenomenon.

If is large ( ), we suspect omitted coefficients are nonzero, so retains the full-model estimate.

If is near is moderate , partially shrinking FM toward SM.

If , then is negative, which is clipped to 0 by the positive-part rule.

Appendix B

3. Asymptotic Quadratic Bias (AQDB) and Distributional Risk (ADR)

We next assess each estimator's risk and define the Asymptotic Quadratic Distributional Bias (AQDB). For an estimator , define

In the local alternatives setting (where the omitted block ), we often look at as , which splits into an asymptotic variance component plus an asymptotic (squared) bias:

Here and . We denote:

where the Asymptotic Quadratic Distributional Bias (AQDB) is and the Asymptotic Distributional Risk (ADR) is their sum.

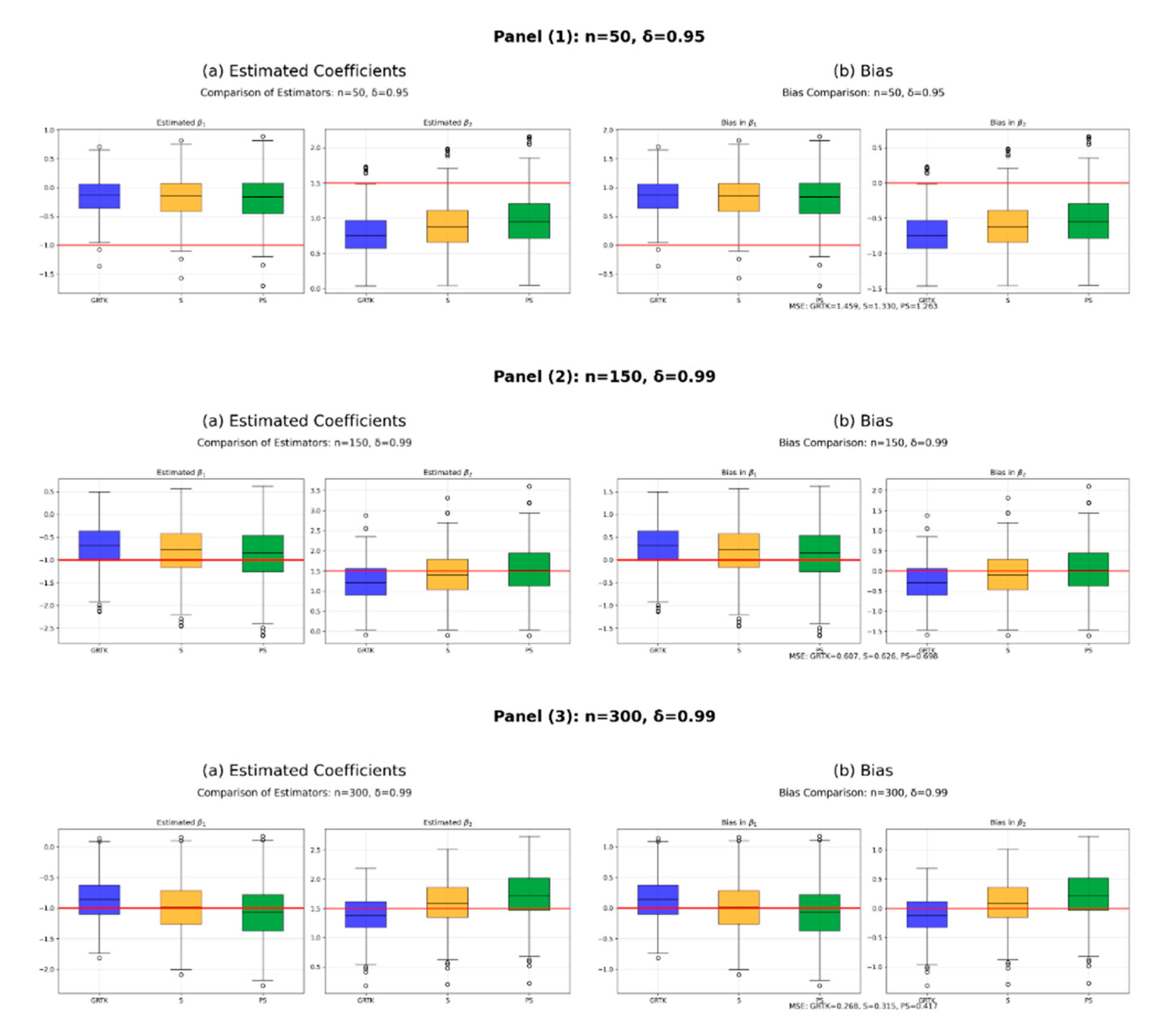

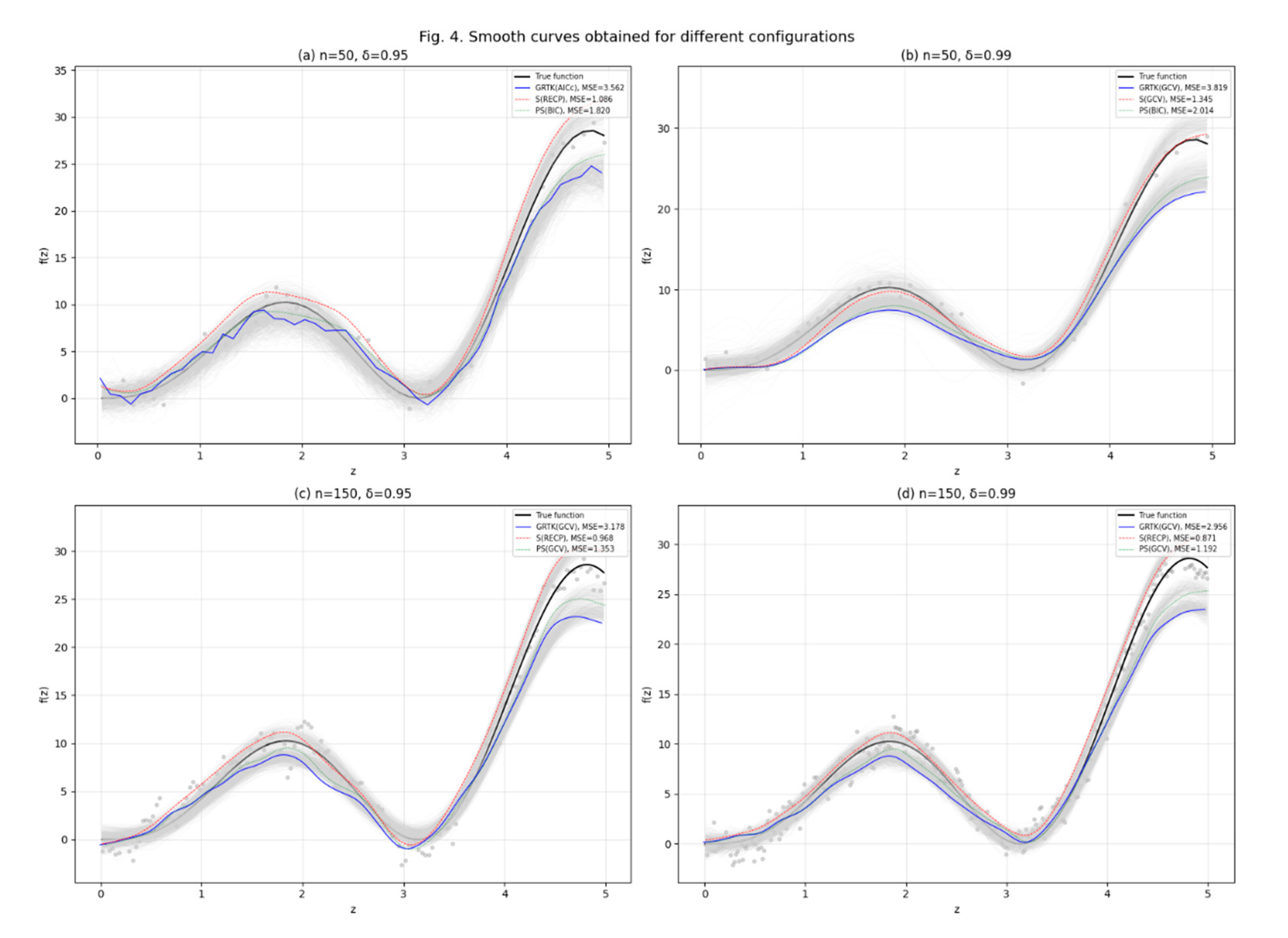

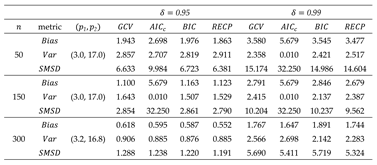

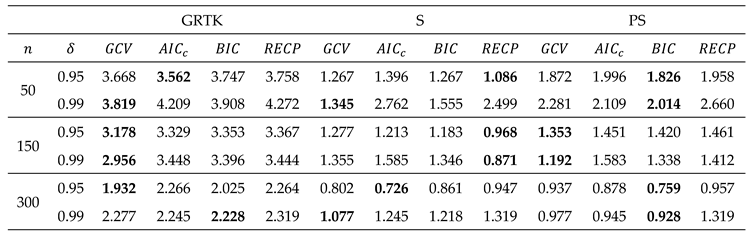

Full-Model (FM): has negligible bias (so ), but a higher variance from estimating all coefficients. Hence , typically .

Submodel (SM): has lower variance (only parameters) but possibly large bias if , giving and a big . Specifically, if the omitted block is , then so .

Stein (S): interpolates. Variance is but . Bias is less than the SM's if omitted effects are actually nonzero, but not zero: times roughly, so .

Positive-Part Stein (PS): ensures no negative shrinkage, so with . Consequently, . Moreover, in typical settings, so dominates in ADR.

Thus, positive-part shrinkage is usually recommended when

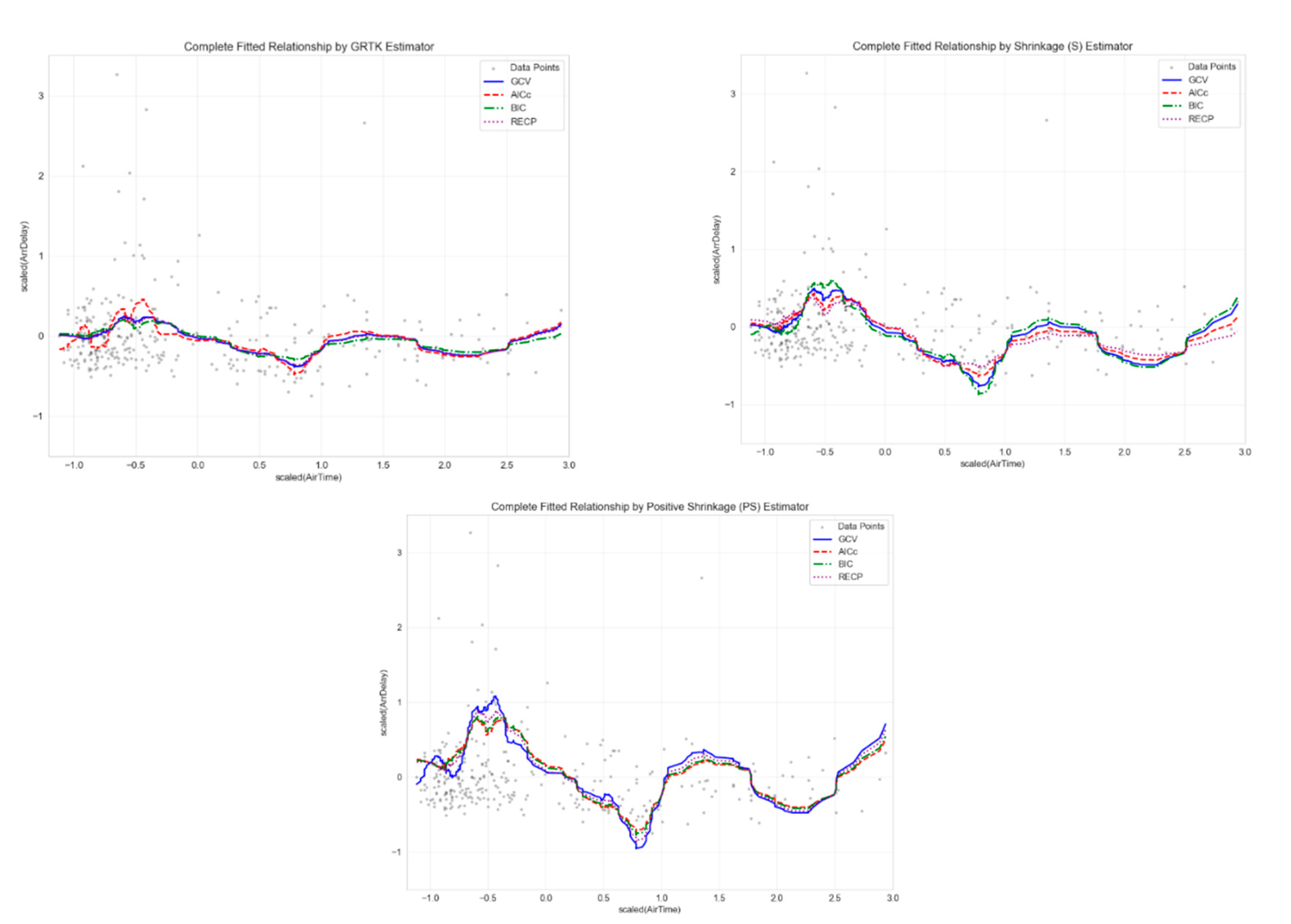

or under moderate correlation/collinearity, as it yields the lowest or nearly lowest ADR across different parameter regimes. This is consistent with the numerical results in

Section 5 of the main text and references such as [

21] and [

3].