1. Introduction

Transformations that humankind has done on nature are so generalized and ancient, that also natural protected areas show great variety of their effects. Some of such transformations are even operative in protected areas [

1,

2,

3]. In the central Pyrenees, like in other Alpine mountains, there are many hydropower infrastructures (i.e., dams, power engines and canals) elsewhere and also in protected natural areas –in fact, most of these infrastructures are prior to the protection rules [

2,

4].

The generalized need for restoring ecosystems is particularly appropriate in protected areas, since one of the goals of these areas is strengthening the knowledge of the ecosystems contents and functions [

5]. Therefore, such areas should host pleasantly field research activity or regular monitoring. This is noteworthy, since to improve restoring procedures it is necessary to conduct sound monitoring and to evaluate accurately the actions performed [

6].

Indeed, the National Park Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici and other Pyrenean protected areas include a number of hydropower infrastructures which, in the future, will create the necessity of restoration [

4]. This process will include dams’ removal to recover the natural basins hydrology and sediments flow, and ecology-based interventions to promote vegetation succession and habitats recovery. In many cases within the Alpine mountains the natural habitats to restore will correspond to mires (peat-forming wetlands, i.e. fens and bogs). Many dams have already been removed all over Europe to restore ecological functions [

7] but procedures of mire restoration in high mountains are far from being known. Concretely, to our knowledge there is no experience of mire restoration in the Pyrenees, and not much more is known from similar Alpine mountain systems [

8]. The particular biogeographic and ecological situation of mountain mires in the Pyrenees [

9,

10] reinforces the need of creating local sound knowledge on their restoration.

Project LIFE+ LimnoPirineus gave us the opportunity of planning and performing the restoration of two Habitats of Community Interest (HCI) in a recently created wasteland after removing a small dam, named Font Grossa. These habitats, transition mires and sphagnum bogs, are habitats of particular significance within the National Park Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici, for their relative abundance in this space and for their rarity in the Catalan Pyrenees [

11,

12]. The two types of mire are well represented in the Trescuro lakes, located just above the Font Grossa and within the same basin, which made these two habitats particularly appropriate for restoration trials in full natural conditions.

Under a broader view, the local opportunity of learning to restore vulnerable ecosystems (i.e. sphagnum hummocks and transition mires) should contribute to focus on restoration of habitats at the edge of their distribution area. In our case, the National Park includes a number of vulnerable species and sensitive ecosystems –even more under climate change– [

11], which have to be managed or restored from ancient anthropic activities (i.e., water use). Restoring ecosystems that are so scarce in the landscape poses particular strength in enhancing the appropriate plant succession, i.e. in improving the appropriate abiotic conditions to initiate the ecosystem development, and in facilitating the targeted species of these ecosystems to build promising populations and communities [

13,

14]. Mainly in water related environments, such species are very rare within the landscape, thus immigration from other populations is hazardous.

Referring to the scientific knowledge of vegetation, we must face the difficulties of initiating ecological succession from scratch over degraded land, under suboptimal environment conditions and within the scarcity of applied knowledge in alpine conditions. Moreover, restoration must focus on mid and long term, to preview that beyond a feasible first step (i.e., setting reasonable populations of engineer species) spontaneously immigrating species assemble into appropriate plant communities; or that further hampering factors (i.e., meteorological events, competition from unpredicted species, geochemical dynamics) might divert the ecological succession [

14].

At present, there is wide experience in sphagnum mire restoration, mainly covering situations where ancient peatland had been deeply degraded [e.g., 15–17]. Most of the acquired knowledge refers to new plant communities developing on ancient bare peat, sometimes submitted to rewetting [

18]. But to our knowledge, no experience has been reported treating ancient reservoirs, i.e. peaty substrata previously inundated, which are now greatly mineral; and very few case studies refer to Alpine mountains [

8,

19].

The main objectives of this study are i) assess the better way of restoring mire ecosystems in alpine landscapes, on the basis of mandatory analysis of the response of appropriate species to the local conditions, their adequate transplantation, and detailed monitoring of the new populations and communities; and ii) evaluate the weight of operating hampering forces and disturbance events that shape the succession progress and their phases –in our case, growing frequency of dry spells or high temperature events in summer, or hydrological irregularities related to alpine landscapes. We therefore aim at gaining knowledge on alpine mires and on the way to shape their restoration. This becomes mandatory for providing the nature managers with science-based solutions to restore ecosystems that, moreover, are scarce and sensitive within fragmented landscapes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Restoring Site

The area studied, Font Grossa, lays in the Peguera water course (2,007 m a.s.l., 42°33'19"N 1°03'46"E), in the National Park Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici, at the Catalan Central Pyrenees, NE Spain. The main environmental conditions come from the local high mountain climate, with mean annual temperature of 5.7 °C and annual precipitation of 1,150 mm, with spring and autumn peaks (data from the last 15 years [

20]). The annual growth period would last less than five months [

21], roughly from mid-May to the beginning of October (more information in

Appendix A). The surrounding landscape is dominated by mesophilous mountain pine (

Pinus uncinata Ram. ex DC.) and alpenrose (

Rhododendron ferrugineum L.) forest, which, given the rough physiography and the ancient land use of the area, is spotted by mat grassland, rocky areas and water related vegetation units (

Figure 1).

Along the main Peguera water course and surrounding springs and rivulets, these vegetation units include small pieces of mire, in the form of tiny spots of

Trichophorum cespitosum (L.) Hartm. fens (Tofieldo-Scirpetum cespitosi),

Carex rostrata Stokes transition mires (Sphagno-Caricetum rostratae) and sphagnum hummocks (Vaccinio-Sphagnetum capillifolii; [

22]. The two latter associations correspond to two Habitats of Community Interest [

23], namely HCI 7140 Transition mires and quaking bogs, in the form of open swards of

C. rostrata with hydrophilic sphagnum carpets bordering still waters; and HCI 7110* Active raised bogs (a priority Habitat), in the form of small (< 5 m

2) sphagnum hummocks protruding from fens. Both habitats find in the National Park and nearby mountains their southernmost locations in Europe, a biogeographic particularity shared with the handful of

Sphagnum species found in them. One of these species,

S. divinum Flatberg & K. Hassel, is classified as Vulnerable in the Iberian Peninsula (formerly included in the

S. magellanicum agg.) [

24,

25].

While several reservoirs upstream remain in use for hydropower production, at Font Grossa there was a small reservoir (area ~1,500 m2) which became useless at the turn of the century. In 2012 the dam and the associated infrastructure were mostly removed to re-naturalize the area, according to an initiative from the National Park to provide a first experiment of passive restoration. This action led the reservoir to lowering the water level about 80 cm and to reduce its area at about 620 m2. Thus, it turned into an almost natural pond with the Peguera ravine course running through the bottom and the remaining base of the old dam retaining water downstream. In addition, over the right shore of the pond there is a significant water surge and some diffuse sources that already maintained a small mire spot prior to the reservoir construction, of which the part above the flood level remained in a good condition.

The ground strip uncovered by water following the elimination of the dam was quite uneven, containing numerous granite blocks. Between these, there was a set of relatively soft surfaces, slightly sloping (~3°), formed by a sandy and silty substrate coming from granite and slate bedrock. Here, the water table remains relatively superficial, determined by slope runoff and the small seasonal oscillation of the pond surface, and subjected to sporadic highs and downs caused by the hydroelectric use of the upstream waters (shifts in the water level up to 13 cm along the growing seasons of 2014 and 2015). The lower part of the shore was potentially appropriate for the targeted transition mire development. The ground water (measured in summer 2014) was slightly acidic and poorly mineralized (pH from 5 to 5.5, electric conductivity from 17 to 31 μS/cm, and Ca content from 3.8 to 7 ppm), whereas the water in the pond gave slightly higher values (pH = 5.5, EC = 48 μS/cm, and Ca = 16 ppm).

After the water lowering and until 2017, the most favourable parts of the newly exposed ground had been irregularly colonised by opportunistic mire or meadow plants, whereas substantial parts of the ground remained bare. The most successful of these species was Juncus articulatus L., which achieved a noticeable population.

2.2. Preparing Experiences with Plant Material

Previously to begin with the restoration experiment, from autumn 2014 to spring 2017 we experienced with distinct plant propagules of appropriate species, mainly in controlled conditions at the University of Barcelona facilities, and eventually in small plots at the restoring site, Font Grossa. This plant material was collected in nearby locations, where their populations would be not affected by this activity. This chiefly included cuttings of

Carex rostrata and small swards of three

Sphagnum species. In all cases, they were species that have a structural role in one habitat or another, covering a certain range of the ecological gradient prevailing in acid mires, mainly that of flooding [

11,

12,

22]. In addition, they were clonal species, i.e. capable of forming large populations from the lateral expansion of one or few individuals [

26]. In the case of vascular plants,

C. rostrata uses to be dominant in periodically flooded mires and on lake shorelines [

27]. Regarding mosses, we chose

Sphagnum teres (Schimp.) Ångström as typical of substantially flooded environments, particularly HCI 7140;

S. capillifolium (Ehrh.) Hedw., typical of the upper part of the sphagnum hummocks in relatively dry conditions (HCI 7110*); and

S. divinum, which is found in an intermediate spectrum of hydrological conditions, but which frequently forms low hummocks (HCI 7110*) [

22,

28,

29].

We tested these species under controlled conditions in two water levels and in distinct competition regimes; and in field plots at the restoring site in distinct water levels and, in the case of vascular plants also in distinct competition regimes. Under controlled conditions,

C. rostrata survived and established in a very high proportion from small cuttings. After three months of culture, growth (leaves, rhizomes) was optimal in young plants in pure culture, regardless of the two water levels experienced. Under field conditions from summer 2015 to autumn 2016, young plants of

C. rostrata established better in flooding conditions than ashore, regardless of whether they faced competition. Therefore, this sedge showed good capacity for implantation and establishment from cuttings into the transition mire to be restored, both in and out of the water [

30,

31].

Regarding mosses, in a first experience we assembled small culture pots, where to arrange caulidium segments of sphagnum including the heads. The trials under controlled conditions included distinct water levels and substrata (such as peat, dead wood or sand). For all three species, survivorship of the fragments was almost total, and growth was significantly affected by the level of flooding and the type of substrata, with more growth using peat and with water at the same level as the substrate [

32]. Afterwards, we run some field experimental trials from midsummer 2016 to autumn 2017. We used commercial peat and entire shoots of sphagnum, since larger fragments proved to grow more vigorously and seemed less sensitive to occasional dry conditions. Moreover, we added a fourth species,

S. subsecundum Nees, to have a second species for the flooded habitat (HCI 7140). The trials were based on small pots of pressed peat (4.5 × 4.5 × 5 cm) with just four shoots of sphagnum on each, covered with a wide mesh of natural fibre. Results highlighted that the reintroduction of sphagnum populations would be sensitive to summer droughts (with some mortality during 2016), and that it would improve through creating particular protective microhabitats since some experimental pots become disturbed, or disappeared, due to episodes of greater intensity in the water flow [

18,

30].

2.3. Setting and Monitoring the Habitats Restoration

Restoration of the transition mire (HCI 7140) started in summer 2017, when the appropriate areas were slightly reshaped and protected from violent flowing episodes with wood stakes sunk into the pond bottom (

Figure A4). Then, the lower part of the gentle shores and the slightly flooded margins of the pond –a patchy area amounting about 135 m

2– were planted with

C. rostrata, to form the basis for the HCI 7140 (

Figure A5). The transplanting units were short (2-4 cm) segments of rhizome with one rosette of leafs each, collected from the margins of a nearby reservoir. These cuttings were directly planted in the restoring area, in a density of about 45 units per square metre. We expected that such light population could shortly grow into a more tied and structured population, similar to those found in natural environments. As monitoring system, we fixed five plots of about 1 × 2 m evenly distributed along the restoring area, where to evaluate the cover and development of

C. rostrata. This evaluation was based on photographic images taken periodically from the same point for each plot, which could be later analysed. In this way, we assigned foliage density values to each image after overlying them with a virtual grid, standardised as percentage quartiles.

In June and July 2018, we transplanted into the restoring places the four

Sphagnum species treated so far. Thus, we prepared 44 plots (each composed by four peat pots of 4.5 × 4.5 × 5 cm) of

S. subsecundum and 30 plots of

S. teres to restore the transition mire (HCI 7140,

Figure A6). The plots of these two species were set at three distinct water levels along the shore gradient. At the just inundated situation, namely 1-2 cm below the water level in regular midsummer conditions, we put 20 and 13 plots of the two species, respectively. Just ashore, namely at 3-4 cm over this water level, we set the same number of plots (20 and 13, respectively). And at about 8-9 cm over the water level we put four plots for each species. This setting was distributed into seven distinct sites along the area already settled by

C. rostrata. There, we expected that the light sward of this sedge would exert some protection from wind and sun on the sphagnum young turfs [

13]. To restore the sphagnum hummocks (HCI 7110*) we set 20 plots of

S. capillifolium and five plots of

S. divinum, as the starting point of the hummocks. They were set looking for favourable spots, namely points with diffuse water flowing and framed by some protective elements such as pieces of dead wood.

Once set the plots with sphagnum propagules, we saw onto them a few specialist species through seeds collected in nearby natural populations. In the transition mire (HCI 7140) we saw Carex canescens L. (a few more than 10 seeds in each pot of 33 plots of S. teres and S. subsecundum) and Viola palustris L. (more than 10 seeds in each pot of 10 plots of S. teres). In the restoring sphagnum hummocks (HCI 7110*) we saw Drosera rotundifolia L. (more than 20 seeds in each pot of 15 plots of S. capillifolium) and Potentilla erecta (L.) Räuschel (more than 20 seeds in each pot of 10 plots of S. capillifolium).

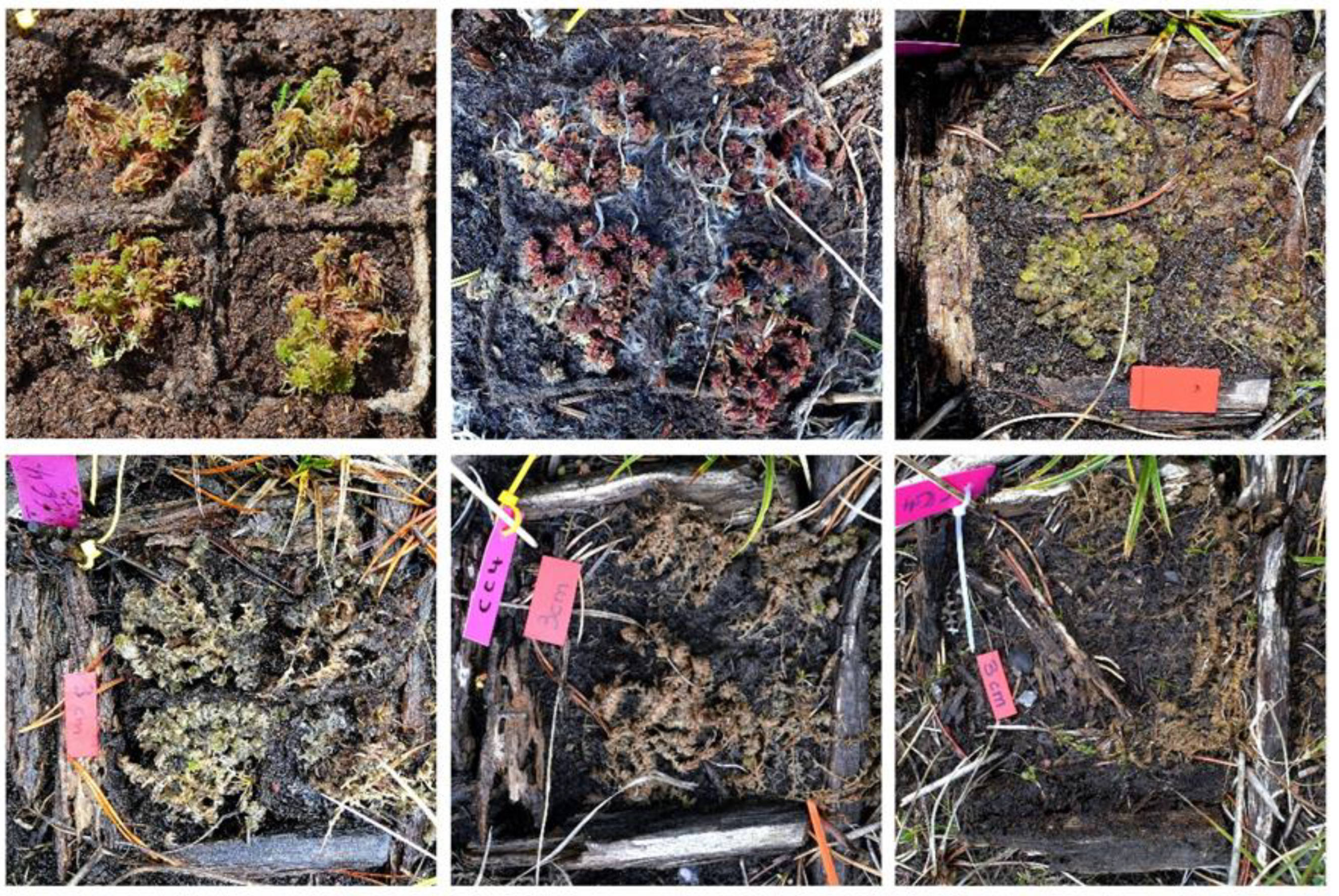

During the first summer most of the sphagnum propagules remained in place. The protective mesh proved to be a key element to prevent the small sphagnum turfs moving through water flows (

Figure A1) and to give some protection against high radiation and temperatures. The plots reached autumn 2018 in good condition, with most sphagnum shoots grown through the protective mesh (

Figure A6).

To monitor the evolution of the sphagnum new populations we assessed the survivorship and the size of the transplants at early and ending summer in 2018, 2019 and 2020, and at ending summer in 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024. The size was assessed through the height achieved by the sphagnum turf at each container in mm, and their canopy projected area in cm

2. To do so, at each monitoring time we took one digital image with a camera set over each group of four pots (i.e., one plot), which included a size reference set at the margin of the sphagnum sward. Once in the laboratory, we digitized each image to contour the sphagnum canopy (

Figure A7) and to calculate its projected area through the software ImageJ [

33]. In 2021, the estimation of the area occupancy of the sphagnum swards in the transition mire became inaccurate in some cases, since the lateral expansion of the swards had led a number of them to coalesce. Then, we set a different design for further monitoring intended to cover more generally the area restored, although not differentiating the two

Sphagnum species. It was based on 21 transects beginning in the external drier conditions and heading to the flooded parts, distributed in the whole area of the transition mire restored and crossing a high proportion of the original sphagnum plots. Along these transects, we recorded the frequency of the sphagnum swards from 2021 to 2024, as well as that of other plant species or relevant elements (water, rocks) through the intercept method at each 10 cm. Moreover, in the monitoring of sphagnum plots of both habitats, we recorded the occurrence of plant species, including the ones sown in the restoration and those arrived spontaneously.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses included the survivorship rate of pots at every sampling campaign (in percentage of pots alive) from 2018 to 2024 and the canopy area of the sphagnum swards along time (in cm

2). We tested the differences between the three distinct water levels in HCI 7140. Moreover, we analysed the differences on survivorship and canopy area among the different species for each HCI (

S. teres and

S. subsecundum in HCI 7140;

S. capillifolium and

S. divinum in HCI 7110*). Since the variables showed strong non-normal distributions, we analysed them with the Kruskal–Wallis test. For multiple group comparisons, we used the Bonferroni p-value correction. Analyses were performed with R [

34], using the package “vegan 2.6-4” [

35].

3. Results

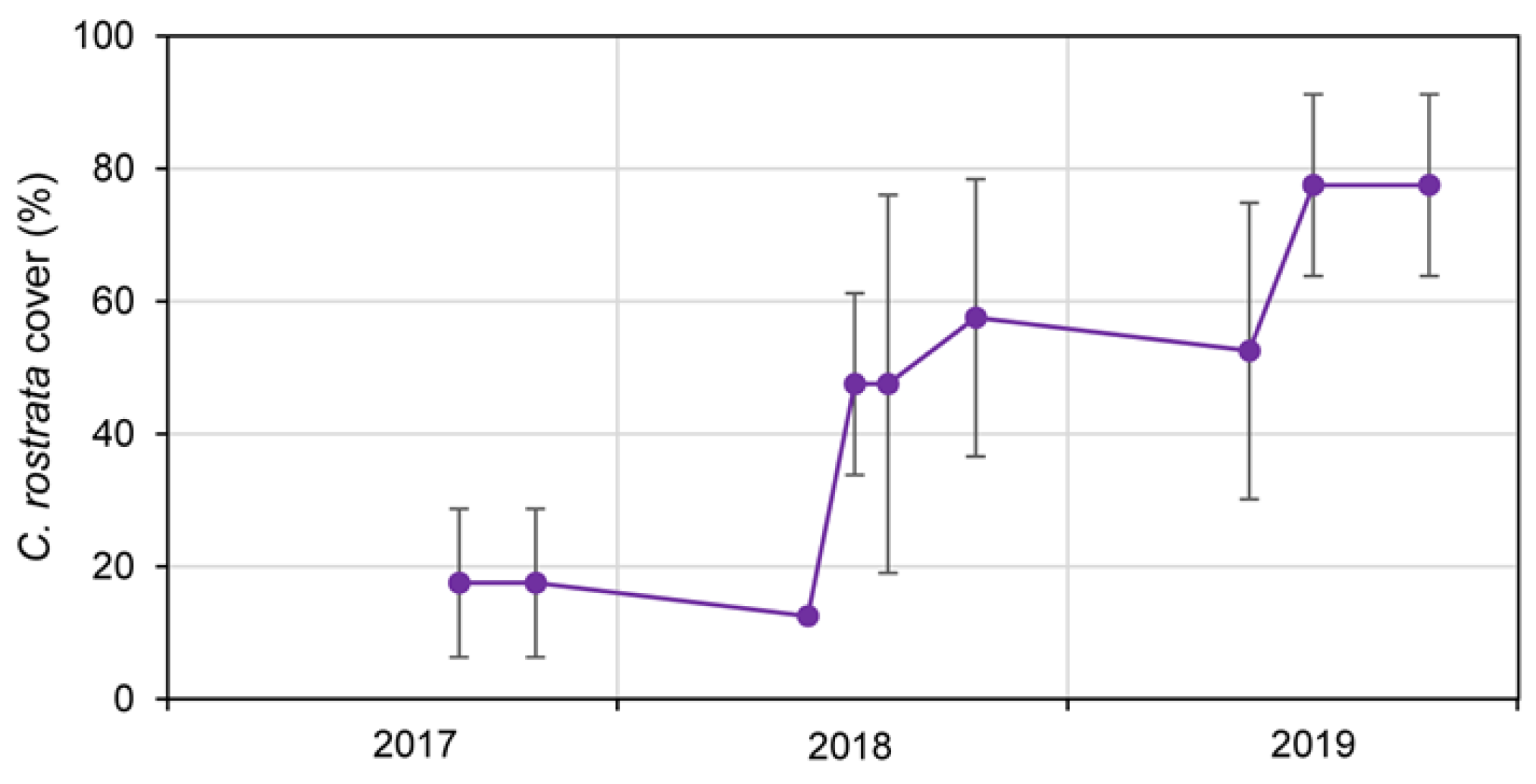

The C. rostrata population established overall very well. By late summer 2017 the plants barely had produced new leafs, but they had rooted and formed new rhizomes, and mortality was very scarce (

Figure 2 and

Figure A4). In 2018 there was noticeable densification and high survivorship, even after two very strong floods, one coming from the massive snow thaw at the end of spring, and the other from an extraordinary rain event in August (

Figure A1). The sedges remained all in place, although in some sectors they were partly buried by flood debris. In 2019 both snow melting and summer rainfall were poor, and temperatures were high in the first half of summer. Although these conditions strongly limited the development of the outermost fringe of the C. rostrata population, at ending summer the densification proceeded overall –achieving similar cover than that of natural mires–, and the population was spontaneously expanding from the area planted through neighbouring shallow water (

Figure A5). Moreover, the established shoots produced rather massive blossom and fruiting.

The survivorship pattern in the newly established sphagnum populations was contrasting between the two habitats, once established in 2018. Both S. teres and S. subsecundum turfs transplanted in the transition mire –within the C. rostrata population– kept very high survival rates from 2019 onwards in the mid and low water levels (

Figure 3). In fact, some of the turfs firstly recorded as dead in early summer 2019 because of signs of decline of most sphagnum shoots, proved to be alive (and growing) along the same summer, which gives some positive slopes in the survivorship graphs. From 2021 onwards, survivorship was presumably very high, and anywhere the very active lateral expansion of most sphagnum turfs made impractical the survivorship assessment of each plot individually. The response in the two Sphagnum species was clearly poorer in the high water level, where the turfs survived only moderately until late summer 2019, and dropped to low rates through 2020, particularly in S. teres. According to non-parametrical tests, the survivorship of both species was significantly lower under the high water table (flooded condition) in late summer 2021 (

Figure 3). Moreover, we found no differences on the survivorship between the two species in the transition mire.

In the sphagnum hummocks, S. capillifolium survivorship decreased from 2019 to ending summer 2024, moderately at first, sharper in 2021-2022, and moderately until 2024, when barely one quarter of the plants remained alive (

Figure 3 and

Figure A8). In the same habitat, S. divinum kept very high survivorship until ending summer 2021, while dropping to about one half of the plants alive after summer 2022 (

Figure 3), and decreasing to one quarter in 2024. Anyway, the final values were not significantly different between the two species. Thus, survivorship pattern of the Sphagnum species after the mid-term monitoring depended primarily on the water table level in the transition mire, and secondly on the habitat, since the sphagnums in the hummocks showed lower survivorship rates than those in the non-inundated area of the transition mire.

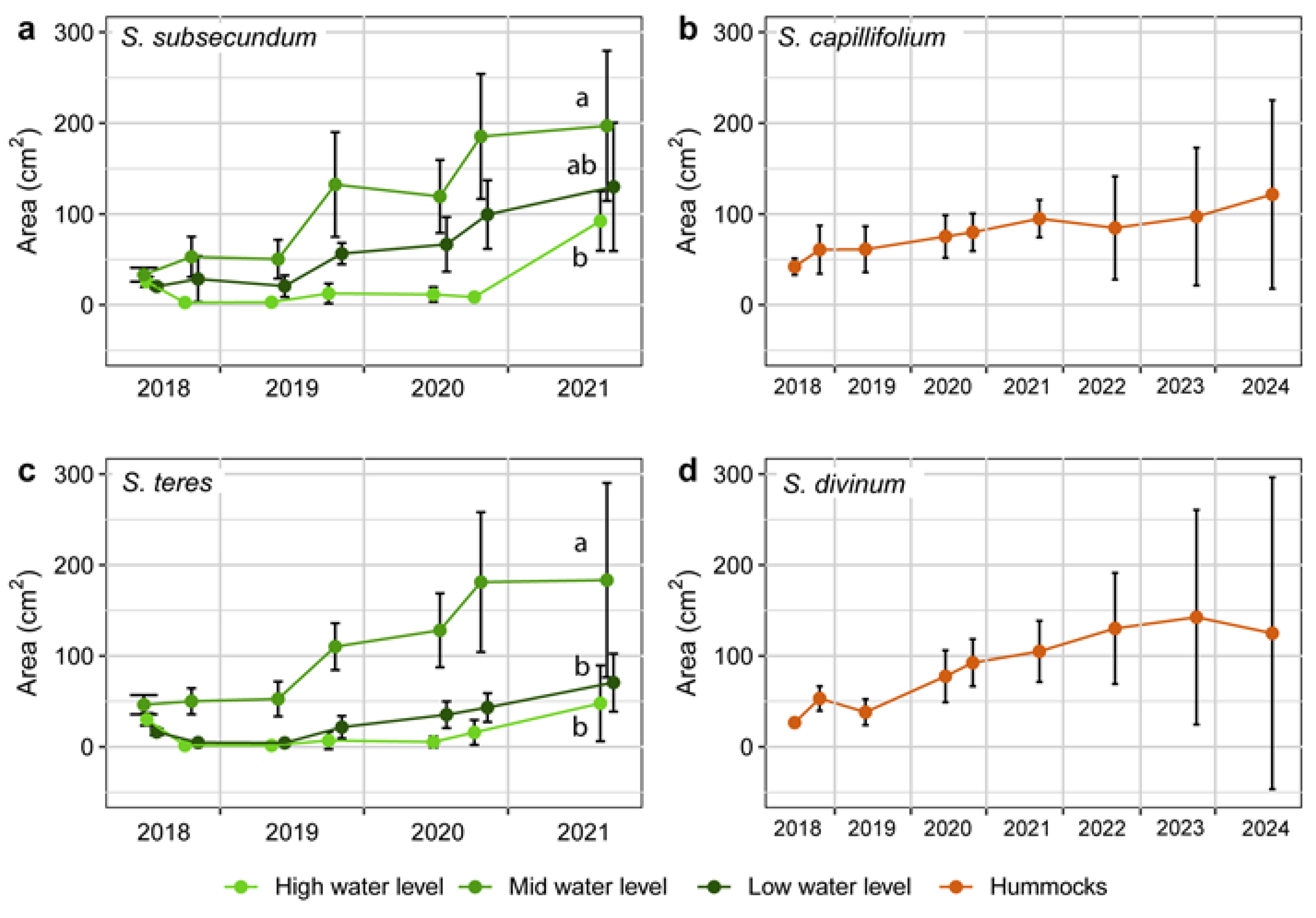

The lateral expansion of each Sphagnum species, measured through the projection area of the samples alive, produced swards significantly larger in 2021 than at the beginning of the experience in all cases. In the transition mire, both S. teres and S. subsecundum expanded through the same pattern, which was different according to the water level (

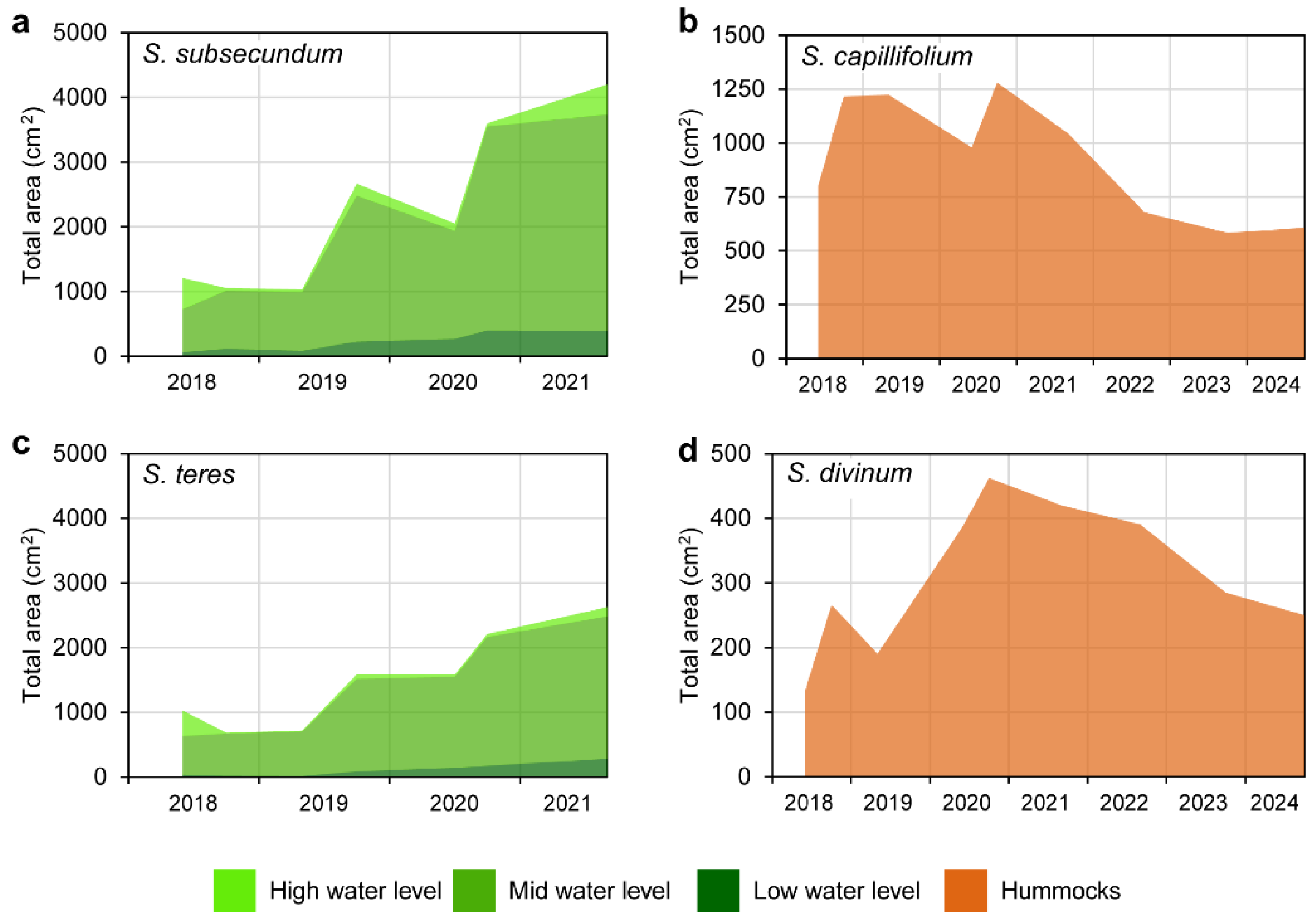

Figure 4). The swards in the high water level decreased already from early to late summer 2018, and did not expand from there to 2021, when showed noticeable growth. In addition, the flowing dynamics may have affected them along the whole experience, via sediment arrived above the swards (field observations). At the other two water levels, both Sphagnum species behaved similarly, with no substantial changes in occupancy during the first growing season, and expanding regularly from 2019 to ending 2021 –with sharper expansion in the middle of the growing periods. Growth has been poorer at the low water level, where summer drought events have been more influential and where the C. rostrata population kept lower density along the monitoring. Nevertheless, relative growth was not significantly different between the two species at the intermediate level, where the swards alive of each species occupied in ending 2021 roughly four times the area set in early 2018. In terms of general cover in the area restored, the sphagnum in the transition mire extended broadly along the mid water level, while faint expansions took place at lower and higher levels (

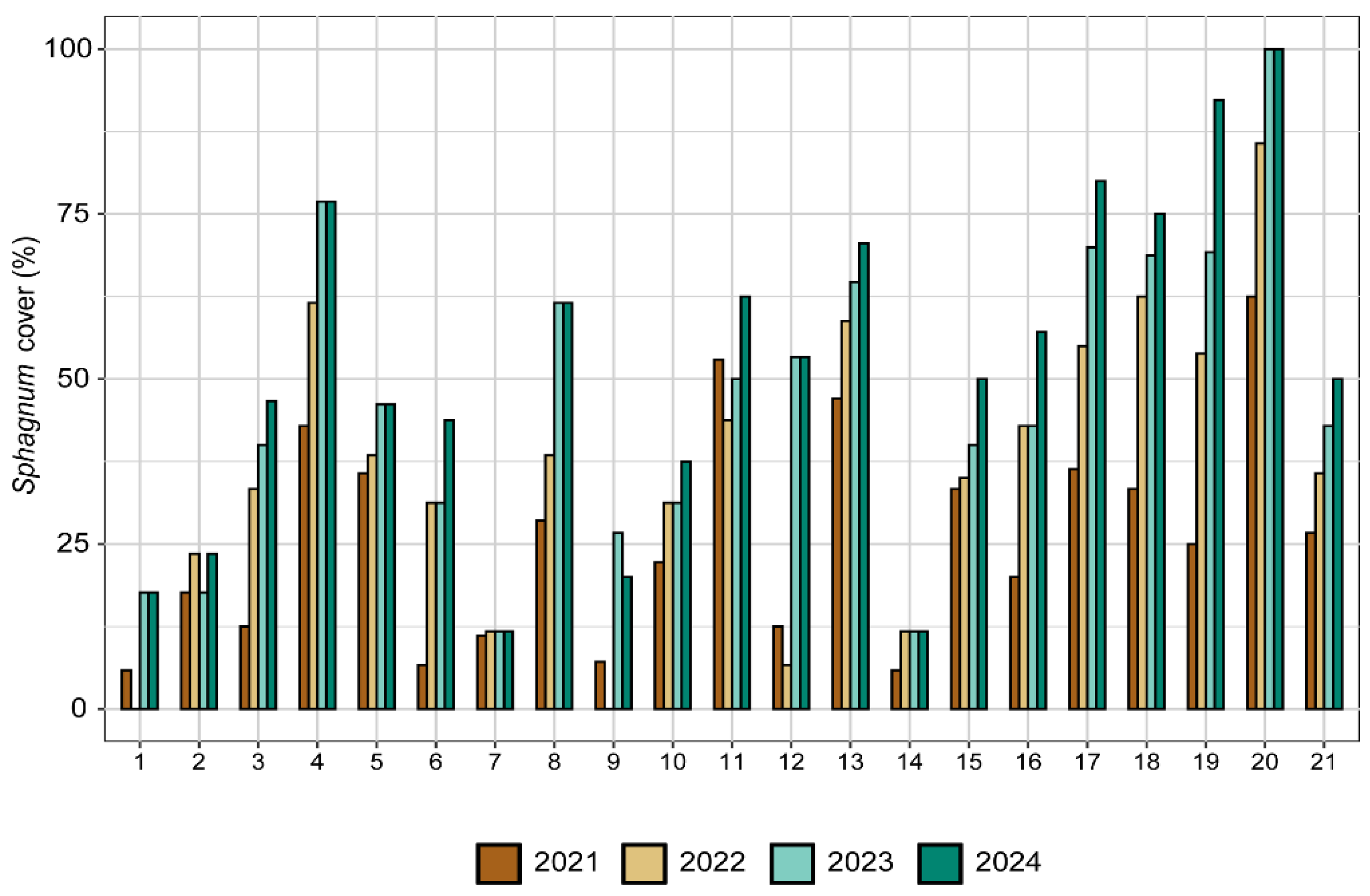

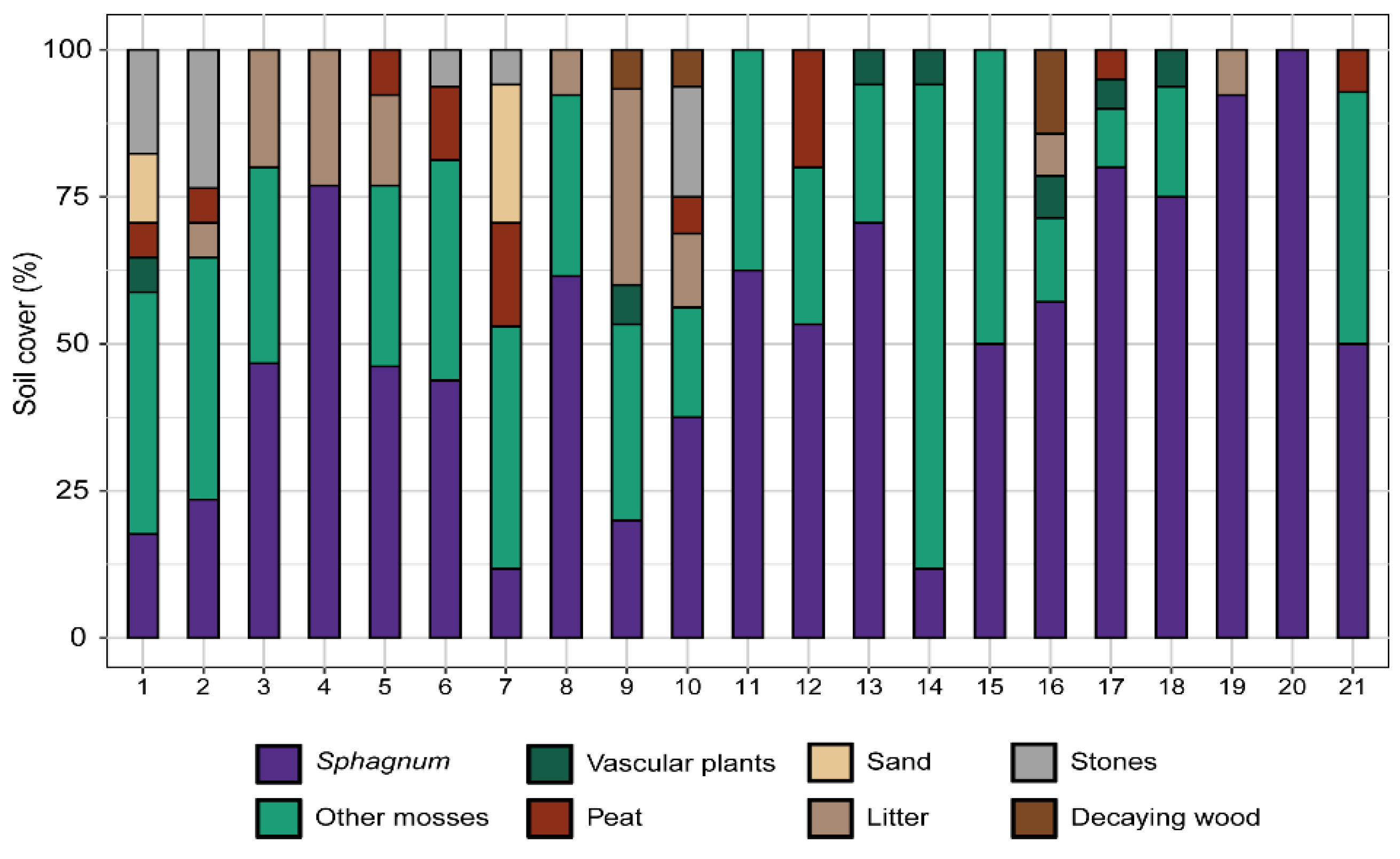

Figure 5). Measured through transects, the two Sphagnum species covered together about 25% of the area in 2021 and reached over 51% in 2024 (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) and showed good vitality. The high cover variability found between transects reflected the noticeable patchiness of the sphagnum lawn in the restored mire, which is usual in natural transition mires.

In the sphagnum hummocks (

Figure A8), the expanding growth of the two species used was moderate and not lineal until 2019 –similarly to that of the Sphagnum species in the transition mire (

Figure 4). But from then to 2024 the two species behaved a bit differently. While the swards of S. divinum expanded regularly at a good rate and decreased the last year, those of S. capillifolium grew moderately most years with a small decrease in 2022. In any case, the first years of establishment of sphagnum turfs has proven to be hazardous for their survivorship and growth, partly due to having planted them in more appropriate microsites, and partly due to damaging weather events. After all, however, the loss of vanishing turfs might be compensated by the growth of the remaining ones.

A general trend arisen in the lateral expansion of sphagnum through habitats, species and water levels is the increasing variability in the response within each case. Namely, the expanding growth became increasingly variable along time between replicate swards (

Figure 4).

Referring to the vascular species sown on the sphagnum swards, Potentilla erecta and Drosera rotundifolia emerged and established in most experimental sphagnum plots of HCI 7110* before 2021, whereas Carex canesces and Viola palustris settled on just one third of the transition mire plots, HCI 7140 (

Figure A3).

From the installation of the sphagnum plots onwards, a number of species established spontaneously in them at both habitats, most grace to seeds –or spores– immigrated and others through rhizome expansion (

Table A1). In the case of the transition mire, in the 2021 monitoring only one plot remained not settled by any of the 23 species recorded as spontaneously arrived. Here, C. rostrata had invaded 83% plots from the surroundings –where it had been planted– grace to its active rhizomes. Other frequent species were Potentilla erecta (20%), Juncus articulatus L. (18%), Epilobium sp. (16%) and Prunella vulgaris L. (13%) (

Figure A11). A few moss species –apart from Sphagnum– established with lower frequency in the plots of both habitats. In the sphagnum hummocks, none of the plots remained free from being spontaneously settled by at least one vascular plant species. In 2024 these were 17 in the whole, the most frequent being Pinus uncinata as small seedlings (found in 66% of the plots), Carex rostrata (44%), Potentilla erecta (33%) and Eleocharis quinqueflora (Hartmann) O. Schwarz (33%) (

Figure A12).

4. Discussion

Our aim of restoring bare ground fostering plant succession towards target mire habitats has yielded promising results, albeit including noticeable pitfalls. Plant growth and survival was uneven between the two restored habitats –and between distinct positions within each habitat–, and the drought spells in the summer of 2021 disturbed the development expected for the new plant populations and communities. Climatic variability worsens the challenge of restoring habitats and species so dependent on even water availability along the growing season, as shown by previous experiences in southern Europe [

36]. Due to climate variability and the clear trend towards a warming climate [

37], it is foreseeable that these effects will make restoration projects more hazardous [

38]. Moreover, the relative success in building plant populations and communities evidenced through our short-term monitoring could develop variously at mid-term, when indicators other than plant growth and new species occurrence would be considered [

14,

19,

39].

4.1. Plants Response to the Restoration Procedure

The restoration of the transition mire has been reasonably successful, from various aspects. The main structural species, the sedge

C. rostrata, proceeded even faster than previewed, since in barely two years formed a uniform, rather dense sward, despite the short growth periods and some sudden flood events (

Figure A9). Transplanting the sphagnum plots one year later than the

C. rostrata cuttings would have enhanced facilitation from the sedge to the mosses, given the very high survivorship and the expanding trend of the sphagnum swards –at least, in those set at mid or low water levels. Other restoration studies have emphasized the facilitation role exerted by sedges or grasses on sphagnum establishment, in the form of partial interception of light and wind, and in amelioration of soil structure and water ascent [

13,

40,

41].

The sphagnum populations in the transition mire, although growing clearly slower than

C. rostrata, performed positively in any case. Both species responded similarly along time and through distinct ecological positions, with

S. subsecundum being slightly more expansive than

S. teres, seemingly through less sensitivity to drought. Setting and monitoring the plots according an elevation gradient on the shore gave us good information on the limiting factors for sphagnum restoration. On the one hand, these hygrophilous mosses need the proximity of the water level; the plots at the upper position on the slope survived but grew less than those set at the intermediate level did. On the other hand, the semi-flooded position was detrimental mainly due to hydrodynamic disturbance –causing early mortality or loss of turfs– and to microhabitat unsuitability, through growth limitation. Thus, the intermediate position enhanced a very satisfactory sphagnum implantation, and would be good place for a whole –though small– example of transition mire, from which expansion to the neighbouring water levels may proceed. The carpet of these

Sphagnum species showed cumulative growth even after the unfavourable 2021 and 2022 summers (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

Hummock sphagnums performed less positively and more diversely among plots. Their swards highly survived the first years, but progressively disappeared through 2021 and 2022 summers. At the same time, however, most of the remaining swards kept expanding trends. Between the two species used,

S. divinum responded better at short term than

S. capillifolium, both in survivorship and in lateral expansion. This may be connected with the higher affinity of

S. divinum for settling on open new habitats, where its development would initiate hummocks, whereas

S. capillifolium would perform better on hummocks already developed [

42,

43]. This should be expression of more ombrophilous character for

S. capillifolium than for

S. divinum [

12,

22]. In our case study, the poor rainfall occurred some summers –particularly 2021 and 2022– would turn the initial hummocks into more influenced by ground water than by rainfall. This shift to less ombrotrophic conditions would have worsened the poor conditions that the restored hummocks –barely elevated from the ground– offered to

S. capillifolium (

Figure A10). However, during the two last growing seasons the different response of the two hummock

Sphagnum species tended to equalize their success. In any case, the restored hummocks became a good chance for reinforcing the most threatened

Sphagnum species in the area,

S. divinum [

23,

24].

The response in both hummock

Sphagnum species became more variable along the monitoring period. This reflects that small differences between plots in terms of microtopography or proximity to protective elements turned into growing differences in plant response, which was emphasized by the fact that Font Grossa is a suboptimal location for sphagnum hummocks [

10,

12]. Under adverse conditions, subtle differences in microhabitats likely determined the survival of hummock-forming sphagnum. However, after the first seven years we observe that the surviving individuals are progressively expanding their cover and appear to be on a trajectory toward long-term persistence. Given that initiating sphagnum hummocks from scratch is a challenging task —since optimal conditions are rarely met within the core of a minerotrophic mire— [

17], we consider the method employed to be successful enough, replicable, and scalable across the Pyrenean region. In our case, restoration success is determined less by the overall survival rate and more by the effective establishment within a portion of the plots.

4.2. Ecological Succession in the Newly Restored Habitats

While C. rostrata and Sphagnum formed noticeable populations in the restored transition mire, the structure and complexity of this new ecosystem increased noticeably. Several vascular wetland plants progressively settled on, and some hydrophilic mosses apart from the

sphagnum joined at the moss level. Therefore, the structure and the species richness of the mire community is approaching to those of natural sites of this habitat [

22]. Similarly to more natural situations, the habitat show some patchiness, partly due to the roughness of the area restored. Apart from granite blocks, other bare spots corresponding to sand or peat ground or to dead wood would become appropriate substrata for the mire species at medium term. The ecosystem is therefore still in a young evolutionary phase.

As expected in the sphagnum hummocks succession in an earlier stage, the accumulation of organic litter is still very poor. The occurrence of dry summers sharply reduces the productivity of these Sphagnum species [

42]. In our case, this hampered the performance expected for the

sphagnum swards, and throw some uncertainty on the fate of this restoring habitat in Font Grossa. The mature hummocks found in areas next to this site may have developed through long periods (

Figure A10). Even some of these natural hummocks showed spots of

sphagnum mortality following the two last summers, which included noticeable drought events. Thus, the formation of new hummocks might only occur favoured by periods of summers regularly rainy. In any case, the initial hummocks set in most favourable microenvironments have persisted and grown after several unfavourable summers. Meanwhile, they are place for some immigrated vascular plants –mainly sedges and grasses– that would enhance their stability and performance if remaining at low to medium densities [

13]. Therefore, at least in these points the restored habitat is prone to positive evolution –though slow and even erratic.

4.3. Learning Points

It is crucial to gain precise knowledge on the system and species to restore through direct experiences, prior to address any restoring action. Even being available quality information on the species and ecosystems, the precise environment treated may cause unpredicted responses. In our case study, previously experiencing with different species under distinct conditions was essential to design and rule the mire restoration.

Restoring planning should evaluate in each case the actual possibility of jumping to further successional stages by artificial means. Transplantation should proceed after physical-chemical improving of the site where abiotic conditions do not meet some minimum conditions needed for plant communities [

14]. Restoring hummocks probably would improve if setting the sphagnum turfs on domes of peat or other appropriate substratum disposed previously (

Figure A13).

Restoring habitats give the opportunity to reintroduce or enhance populations of threatened species. Contrasting with their biogeographic vulnerability or local rarity, they may develop good colonizing capacity in a restoration context, as occurred with S. divinum in our study. The use of propagules of these species should not compromise in any case the persisting capacity of the populations sampled.

We particularly emphasize the importance of monitoring the ecosystems and populations restored. This is key not only to reliably assess the progress made, but to describe the plant succession in reasonable detail. This is particularly useful in poorly known systems, as is the case of peatlands in southern European mountains. Thus, restoration actions and ecological knowledge of natural systems must coexist and strengthen each other. While restoration actions need some knowledge of the structure and function of ecosystems, such knowledge feeds from management and restoration actions –including proper monitoring of the ecosystems restored.