Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Overall Approach

Systematic Evaluation of All Articles Containing the Terms Autism and Acetaminophen in Any PubMed Search Field

Treatment of Seminal Studies in The field by Subsequent Work

Results

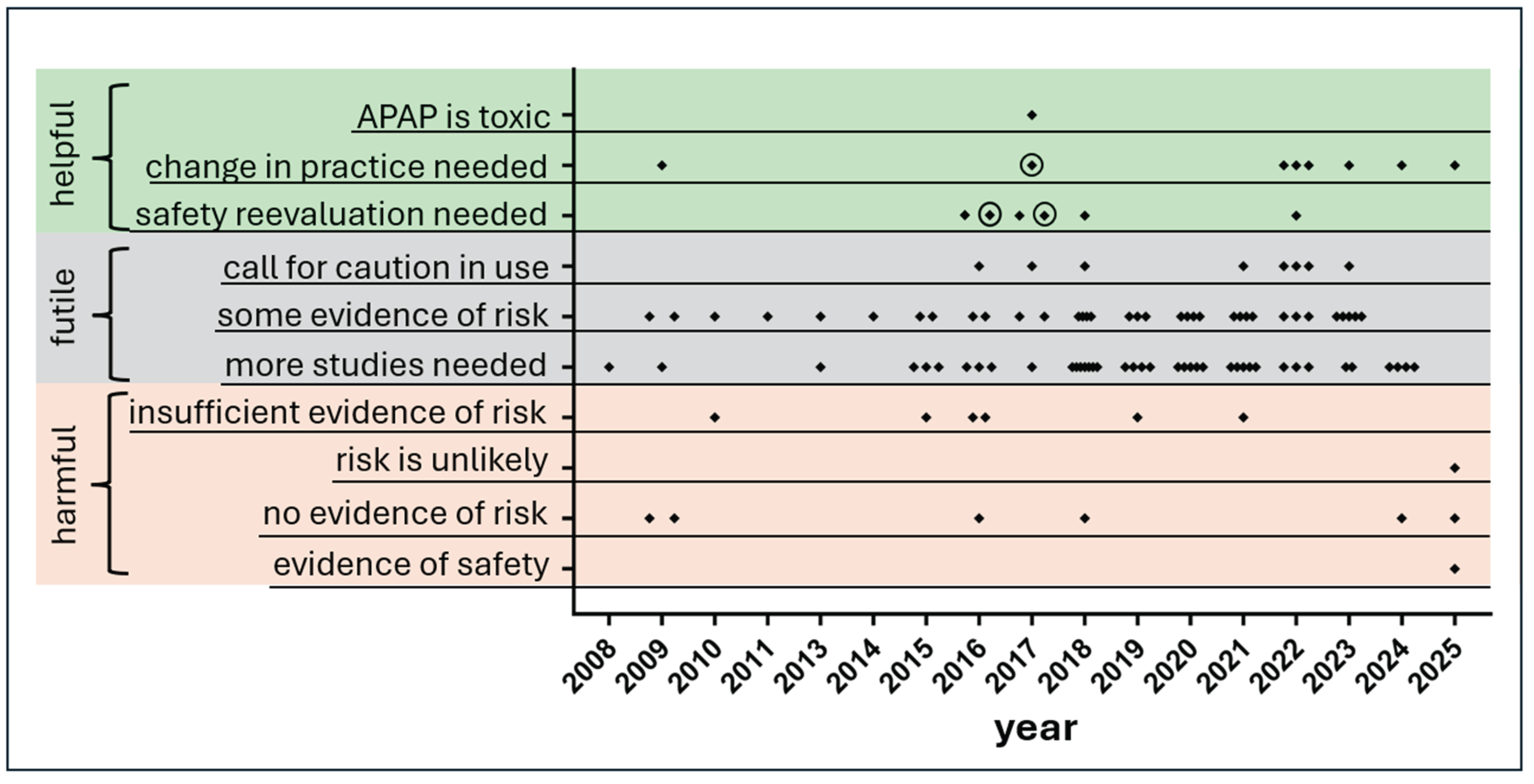

Predominance of Statements in the Medical Literature Either of Questionable Utility or not Helpful From a Clinical Perspective

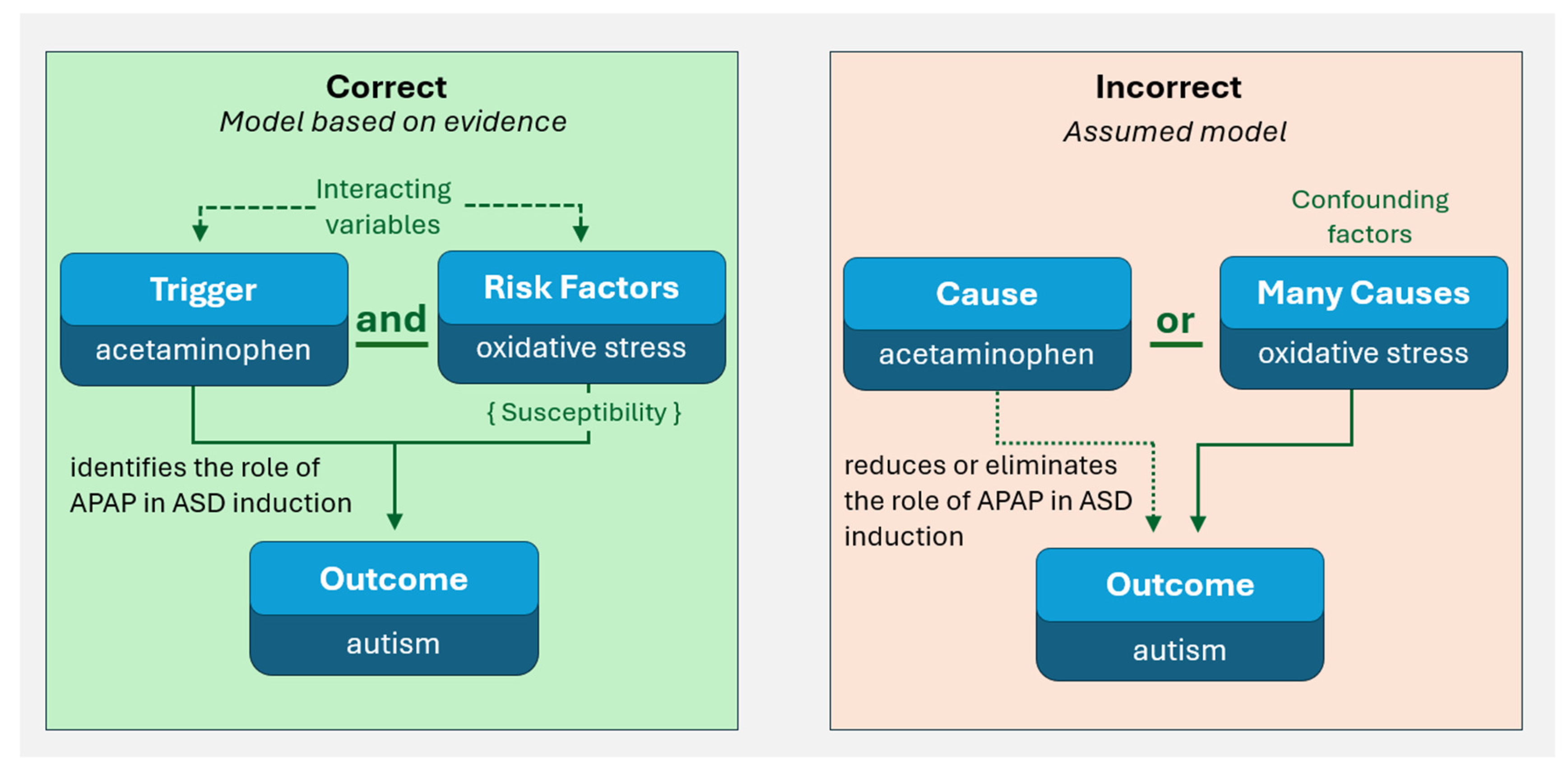

Mishandling of Evidence 1: The Prevalent and Fundamental Statistical Error of Assuming Interacting Variables Are Confounding Factors

Mishandling of Evidence 2: Small Fraction of Available Evidence Used to Draw Conclusions

Mishandling of Evidence 3: Irrational Criticisms of Some Evidence

Discussion

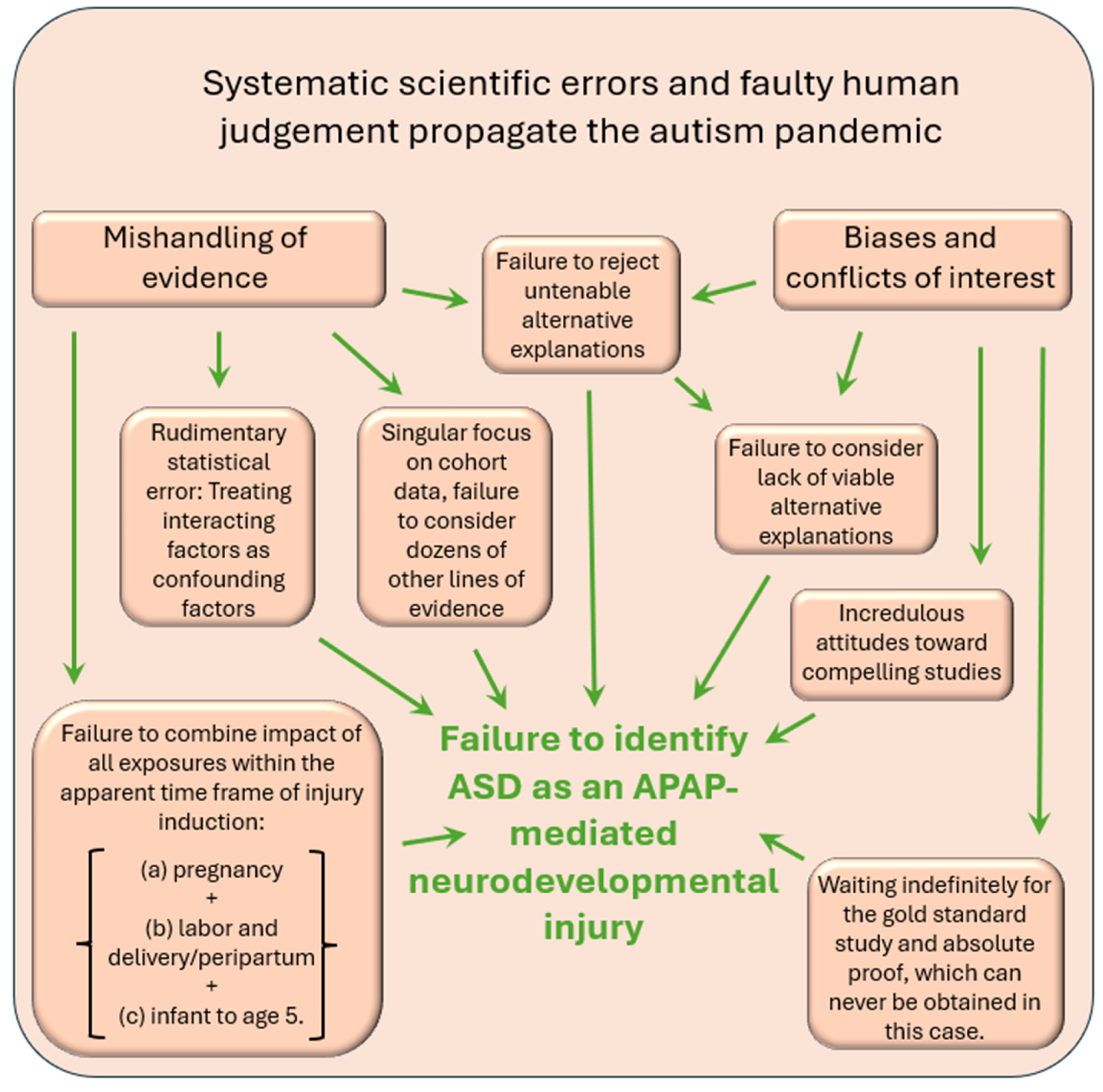

No Single Problem Underlying Widespread Failure to Accept Current Evidence

Study Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Patel, E.; Jones Iii, J.P., 3rd; Bono-Lunn, D.; Kuchibhatla, M.; Palkar, A.; Cendejas Hernandez, J.; et al. The safety of pediatric use of paracetamol (acetaminophen): a narrative review of direct and indirect evidence. Minerva pediatrics. 2022, 74, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.P., 3rd; Williamson, L.; Konsoula, Z.; Anderson, R.; Reissner, K.J.; Parker, W. Evaluating the Role of Susceptibility Inducing Cofactors and of Acetaminophen in the Etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, L.; Jones, J.; Anderson, L.; Konsoula, Z.; Nevison, C.; Reissner, K.; et al. Acetaminophen causes neurodevelopmental injury in susceptible babies and children: no valid rationale for controversy. Clinical and experimental pediatrics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, W.; Anderson, L.G.; Jones, J.P.; Anderson, R.; Williamson, L.; Bono-Lunn, D.; et al. The Dangers of Acetaminophen for Neurodevelopment Outweigh Scant Evidence for Long-Term Benefits. Children. 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, W.; Hornik, C.D.; Bilbo, S.; Holzknecht, Z.E.; Gentry, L.; Rao, R.; et al. The role of oxidative stress, inflammation and acetaminophen exposure from birth to early childhood in the induction of autism. J Int Med Res. 2017, 45, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, S.T.; Klonoff-Cohen, H.S.; Wingard, D.L.; Akshoomoff, N.A.; Macera, C.A.; Ji, M. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) use, measles-mumps-rubella vaccination, and autistic disorder. The results of a parent survey. Autism. 2008, 12, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, P. Did acetaminophen provoke the autism epidemic? Alternative Medicine Review. 2009, 14, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuishi, T.; Shiotsuki, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Shoji, H.; Imuta, F.; Yamashita, F. High prevalence of infantile autism in Kurume City, Japan. J Child Neurol. 1987, 2, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, A.; Pirrone, P.; Elia, M.; Waring, R.H.; Romano, C. Sulphation deficit in “low-functioning” autistic children: a pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 1999, 46, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, L. The Metabolism of Paracetamol. Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) A Critical Bibliographic Review; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1996; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Anvik, J.O. Acetaminophen toxicosis in a cat. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne. 1984, 25, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Savides, M.C.; Oehme, F.W.; Nash, S.L.; Leipold, H.W. The toxicity and biotransformation of single doses of acetaminophen in dogs and cats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984, 74, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Omer, V.V.; McKnight, E.D., 3rd. Acetylcysteine for treatment of acetaminophen toxicosis in the cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1980, 176, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.P.; Roberts, R.J.; Fischer, L.J. Acetaminophen elimination kinetics in neonates, children, and adults. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976, 19, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, G.; Khanna, N.N.; Soda, D.M.; Tsuzuki, O.; Stern, L. Pharmacokinetics of acetaminophen in the human neonate: formation of acetaminophen glucuronide and sulfate in relation to plasma bilirubin concentration and D-glucaric acid excretion. Pediatrics. 1975, 55, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cendejas-Hernandez, J.; Sarafian, J.; Lawton, V.; Palkar, A.; Anderson, L.; Lariviere, V.; et al. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) Use in Infants and Children was Never Shown to be Safe for Neurodevelopment: A Systematic Review with Citation Tracking. . Eur J Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1835–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.D.; Shires, T.K.; Fischer, L.J. Hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen in neonatal and young rats. I. Age-related changes in susceptibility. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984, 74, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freed, G.L.; Clark, S.J.; Butchart, A.T.; Singer, D.C.; Davis, M.M. Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009. Pediatrics. 2010, 125, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzano, A.; Zeldin, A.; Schuster, E.; Barrett, C.; Lehrer, D. Vaccine-related beliefs and practices of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012, 117, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbach, R.L.; Harris, M.J.; Ballan, M.S.; Fischbach, G.D.; Link, B.G. Is there concordance in attitudes and beliefs between parents and scientists about autism spectrum disorder? Autism. 2016, 20, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonsu, N.E.M.; Mire, S.S.; Sahni, L.C.; Berry, L.N.; Dowell, L.R.; Minard, C.G.; et al. Understanding Vaccine Hesitancy Among Parents of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Parents of Children With Non-Autism Developmental Delays. J Child Neurol. 2021, 36, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rimland, B. The autism increase: research needed on the vaccine connection. Autism Research Review International 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D. MMR, autism, and adam. BMJ. 2000, 320, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schultz, S. Understanding Autism: My Quest for Nathan; Schultz Publishing LLC, 2013; 92 p. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, E.; Dawson, G. Validation of the phenomenon of autistic regression using home videotapes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005, 62, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viberg, H.; Eriksson, P.; Gordh, T.; Fredriksson, A. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) Administration During Neonatal Brain Development Affects Cognitive Function and Alters Its Analgesic and Anxiolytic Response in Adult Male Mice. Toxicol Sci. 2013, 138, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Simonsen, J. Ritual circumcision and risk of autism spectrum disorder in 0- to 9-year-old boys: national cohort study in Denmark. J R Soc Med. 2015, 108, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Azuine, R.E.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; et al. Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020, 77, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brandlistuen, R.E.; Ystrom, E.; Nulman, I.; Koren, G.; Nordeng, H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: a sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1702–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.Y.; Kabiraj, G.; Ahmed, M.A.; Adam, M.; Mannuru, S.P.; Ramesh, V.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Acetaminophen: A Mystery to Resolve. Cureus. 2022, 14, e26995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecharz-Klin, K.; Wawer, A.; Jawna-Zboińska, K.; Pyrzanowska, J.; Piechal, A.; Mirowska-Guzel, D.; et al. Early paracetamol exposure decreases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in striatum and affects social behaviour and exploration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2018, 168, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palta, P.; Szanton, S.L.; Semba, R.D.; Thorpe, R.J.; Varadhan, R.; Fried, L.P. Financial strain is associated with increased oxidative stress levels: the Women’s Health and Aging Studies. Geriatric nursing (New York, NY). 2015, 36 (2 Suppl), S33–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eick, S.M.; Barrett, E.S.; van ‘t Erve, T.J.; Nguyen, R.H.N.; Bush, N.R.; Milne, G.; et al. Association between prenatal psychological stress and oxidative stress during pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2018, 32, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrabalova, J.; Drastichova, Z.; Novotny, J. Morphine as a Potential Oxidative Stress-Causing Agent. Mini-reviews in organic chemistry. 2013, 10, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kalghatgi, S.; Spina, C.S.; Costello, J.C.; Liesa, M.; Morones-Ramirez, J.R.; Slomovic, S.; et al. Bactericidal antibiotics induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Mammalian cells. Science translational medicine. 2013, 5, 192ra85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moller, P.; Wallin, H.; Knudsen, L.E. Oxidative stress associated with exercise, psychological stress and life-style factors. Chem-Biol Interact. 1996, 102, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lean, S.C.; Jones, R.L.; Roberts, S.A.; Heazell, A.E.P. A prospective cohort study providing insights for markers of adverse pregnancy outcome in older mothers. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2021, 21, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marseglia, L.; Manti, S.; D’Angelo, G.; Nicotera, A.; Parisi, E.; Di Rosa, G.; et al. Oxidative stress in obesity: a critical component in human diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2014, 16, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Rajavelu, I.; Pereira, M.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; et al. Inside the genome: understanding genetic influences on oxidative stress. Front Genet. 2024, 15, 1397352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Forsberg, L.; de Faire, U.; Morgenstern, R. Oxidative stress, human genetic variation, and disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001, 389, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, R.C.; Claiborne, J.; Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz, M.; Reddy, R.; Aschner, M.; Lewis, D.A.; et al. Altered expression of genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis in frontal cortex in major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011, 16, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk, M.; Williams, L.J.; Jacka, F.N.; O’Neil, A.; Pasco, J.A.; Moylan, S.; et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC medicine 2013, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, S. Oxidative Stress and the Central Nervous System. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017, 360, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Foo, J.; Bellot, G.; Pervaiz, S.; Alonso, S. Mitochondria-mediated oxidative stress during viral infection. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 30, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milhelm, Z.; Zanoaga, O.; Pop, L.; Iovita, A.; Chiroi, P.; Harangus, A.; et al. Evaluation of oxidative stress biomarkers for differentiating bacterial and viral infections: a comparative study of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and reduced glutathione (GSH). Medicine and pharmacy reports. 2025, 98, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bauer, A.; Kriebel, D. Prenatal and perinatal analgesic exposure and autism: an ecological link. Environmental Health. 2013, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A.R.; McDowell, S. A response to the article on the association between paracetamol/acetaminophen: use and autism by Stephen T. Schultz. Autism. 2009, 13, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, S.T. Response to the Letter by Cox and McDowell: Association of Paracetamol/Acetaminophen Use and Autism. Autism. 2009, 13, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietrantonj, C.; Rivetti, A.; Marchione, P.; Debalini, M.G.; Demicheli, V. Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021, CD004407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pietrantonj, C.; Rivetti, A.; Marchione, P.; Debalini, M.G.; Demicheli, V. Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020, 4, Cd004407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tenny, S.; Kerndt, C.C.; Hoffman, M.R. Case Control Studies. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL).

- Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025.

- Morris, B.J.; Moreton, S.; Krieger, J.N.; Klausner, J.D. Infant Circumcision for Sexually Transmitted Infection Risk Reduction Globally. Global health, science and practice. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morris, B.J.; Katelaris, A.; Blumenthal, N.J.; Hajoona, M.; Sheen, A.C.; Schrieber, L.; et al. Evidence-based circumcision policy for Australia. Journal of men’s health. 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morris, B.J.; Moreton, S.; Bailis, S.A.; Cox, G.; Krieger, J.N. Critical evaluation of contrasting evidence on whether male circumcision has adverse psychological effects: A systematic review. Journal of evidence-based medicine. 2022, 15, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morris, B.J.; Moreton, S.; Krieger, J.N. Critical evaluation of arguments opposing male circumcision: A systematic review. Journal of evidence-based medicine. 2019, 12, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morris, B.J.; Krieger, J.N.; Klausner, J.D. CDC’s Male Circumcision Recommendations Represent a Key Public Health Measure. Global health, science and practice. 2017, 5, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morris, B.J.; Wiswell, T.E. ‘Circumcision pain’ unlikely to cause autism. J R Soc Med. 2015, 108, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miani, A.; Di Bernardo, G.A.; Højgaard, A.D.; Earp, B.D.; Zak, P.J.; Landau, A.M.; et al. Neonatal male circumcision is associated with altered adult socio-affective processing. Heliyon. 2020, 6, e05566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahlqvist, V.H.; Sjöqvist, H.; Dalman, C.; Karlsson, H.; Stephansson, O.; Johansson, S.; et al. Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy and Children’s Risk of Autism, ADHD, and Intellectual Disability. Jama. 2024, 331, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Juujärvi, S.; Saarela, T.; Pokka, T.; Hallman, M.; Aikio, O. Intravenous paracetamol for neonates: long-term diseases not escalated during 5 years of follow-up. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2021, 106, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qubty, W.; Gelfand, A.A. The Link Between Infantile Colic and Migraine. Current pain and headache reports. 2016, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, Z.; Ritz, B.; Virk, J.; Olsen, J. Maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders in childhood: A Danish national birth cohort study. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2016, 9, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, Z.; Ernst, A. Intrauterine Exposure to Acetaminophen and Adverse Developmental Outcomes: Epidemiological Findings and Methodological Issues. Current environmental health reports. 2021, 8, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coluzzi, F.; Di Stefano, G.; Scerpa, M.S.; Rocco, M.; Di Nardo, G.; Innocenti, A.; et al. The Challenge of Managing Neuropathic Pain in Children and Adolescents with Cancer. Cancers. 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lexchin, J.; Bero, L.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Clark, O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ. 2003, 326, 1167–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bero, L.A. Tobacco industry manipulation of research. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 2005, 120, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fabbri, A.; Holland, T.J.; Bero, L.A. Food industry sponsorship of academic research: investigating commercial bias in the research agenda. Public health nutrition. 2018, 21, 3422–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Whitstock, M. Manufacturing the truth: From designing clinical trials to publishing trial data. Indian journal of medical ethics. 2018, 3, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Chernesky, J.; Lembke, A.; Michaels, D.; Tomori, C.; Greene, J.A.; et al. The opioid industry’s use of scientific evidence to advance claims about prescription opioid safety and effectiveness. Health affairs scholar. 2024, 2, qxae119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Legg, T.; Hatchard, J.; Gilmore, A.B. The Science for Profit Model-How and why corporations influence science and the use of science in policy and practice. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0253272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tran, T.H.; Steffen, J.E.; Clancy, K.M.; Bird, T.; Egilman, D.S. Talc, Asbestos, and Epidemiology: Corporate Influence and Scientific Incognizance. Epidemiology. 2019, 30, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brownell, K.D.; Warner, K.E. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q. 2009, 87, 259–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kougias, D.G.; Atillasoy, E.; Southall, M.D.; Scialli, A.R.; Ejaz, S.; Chu, C.; et al. A quantitative weight-of-evidence review of preclinical studies examining the potential developmental neurotoxicity of acetaminophen. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.A.; Kennon-McGill, S.; Parker, L.D.; James, L.P.; Fantegrossi, W.E.; McGill, M.R. NAPQI is absent in the mouse brain after sub-hepatotoxic and hepatotoxic doses of acetaminophen. Toxicol Sci. 2025, 205, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Philippot, G.; Gordh, T.; Fredriksson, A.; Viberg, H. Adult neurobehavioral alterations in male and female mice following developmental exposure to paracetamol (acetaminophen): characterization of a critical period. J Appl Toxicol. 2017, 37, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenburg, W.R.; Gramling, R.; Davidson, D.J. Scientific Certainty Argumentation Methods (SCAMs): Science and the Politics of Doubt. Sociological Inquiry. 2008, 78, 2–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, J.W. Uncertainty as a fundamental scientific value. Integrative psychological & behavioral science. 2010, 44, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, M. The uncertainty of science and the science of uncertainty. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2010, 31, 1767–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Ryan, M.L.; Saxena, S.; Baum, F. Time for a revolution in academic medicine? BMJ. 2024, 387, q2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Konsoula, Z.; Williamson, L.; Anderson, R.; Meza-Keuthen, S.; Parker, W. Three Mandatory Doses of Acetaminophen During the First Months of Life with the MenB Vaccine: A Protocol for the Induction of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Susceptible Individuals. Preprints: Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar]

- de Fays, L.; Van Malderen, K.; De Smet, K.; Sawchik, J.; Verlinden, V.; Hamdani, J.; et al. Use of paracetamol during pregnancy and child neurological development. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).