Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hypothesis

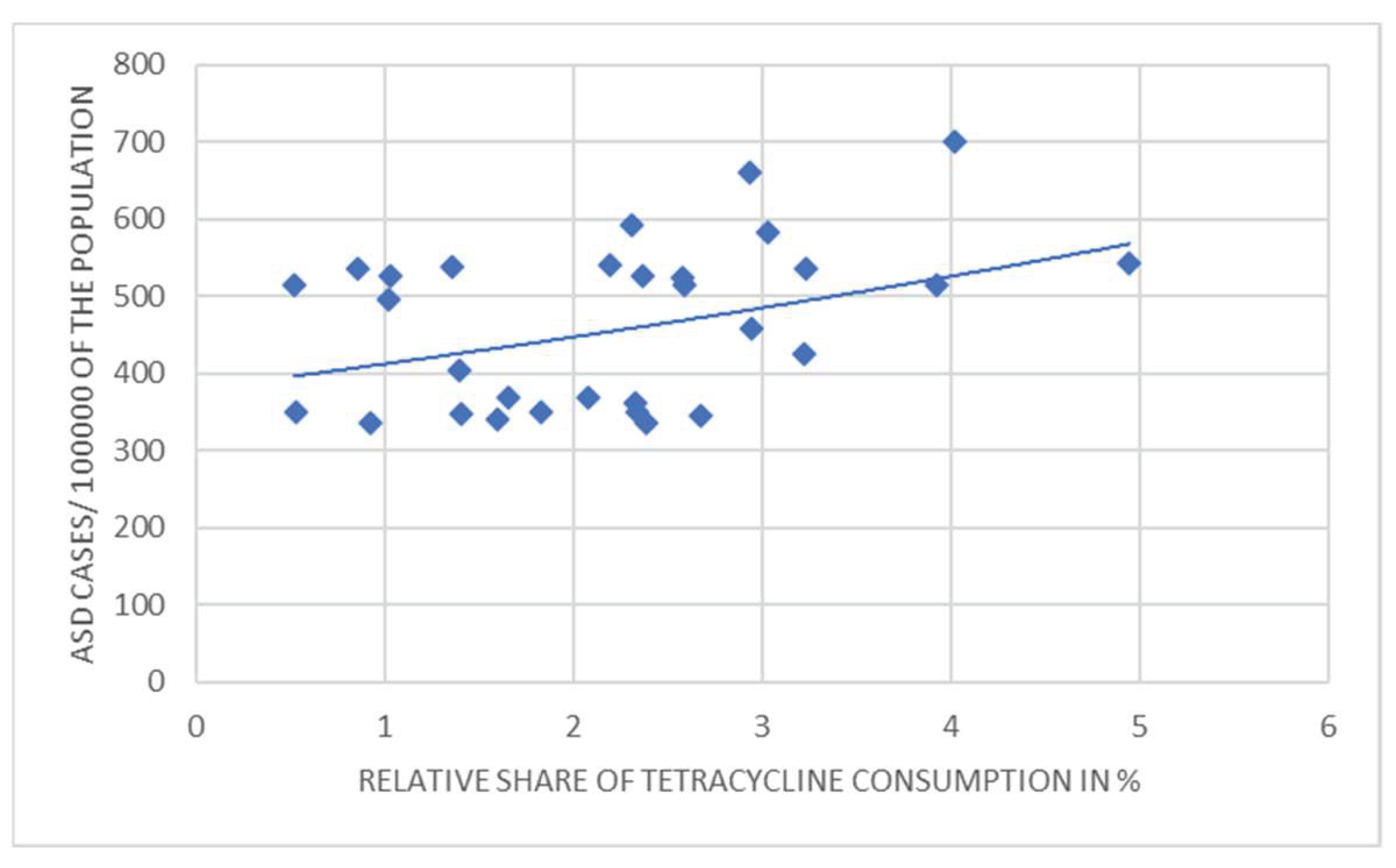

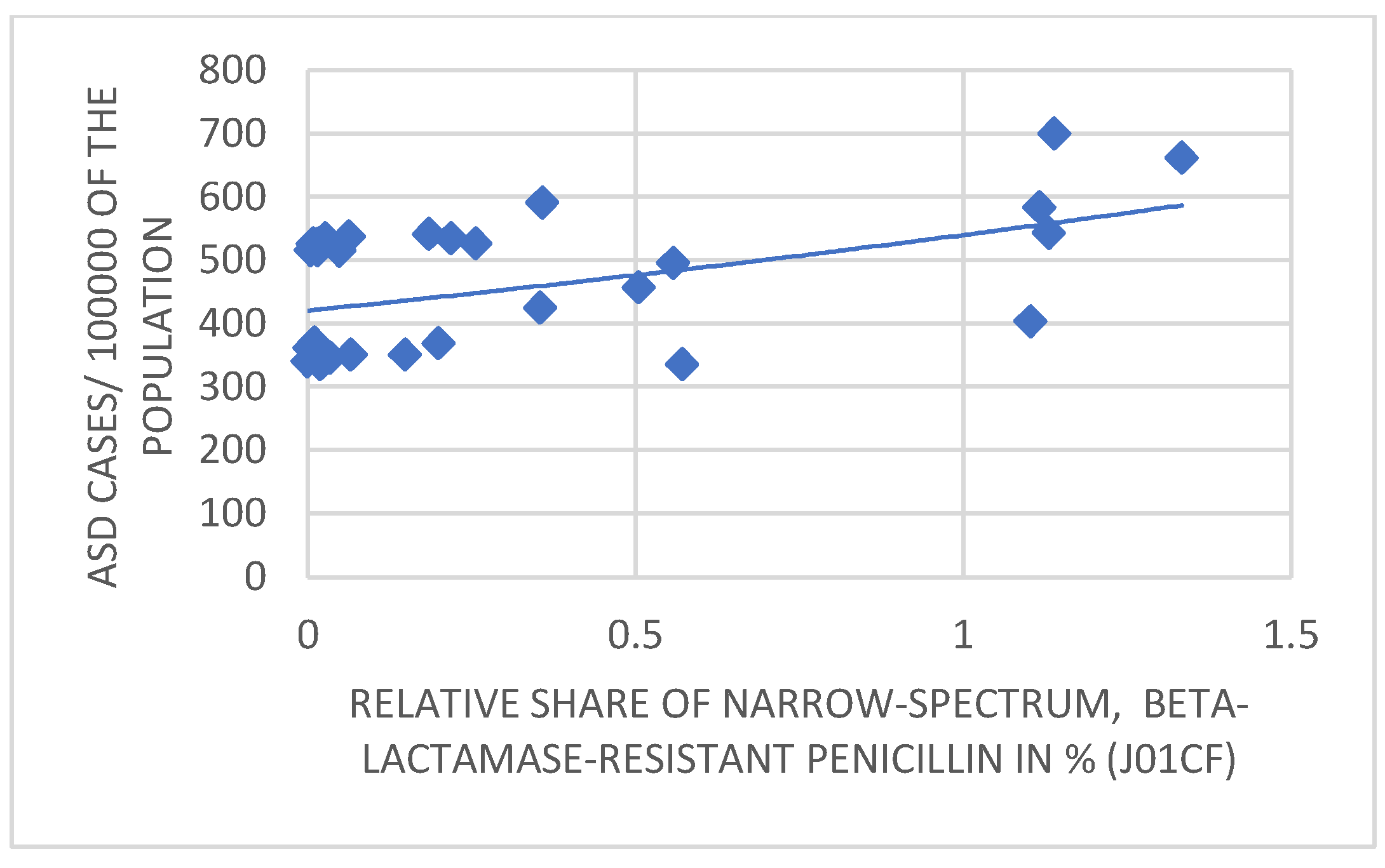

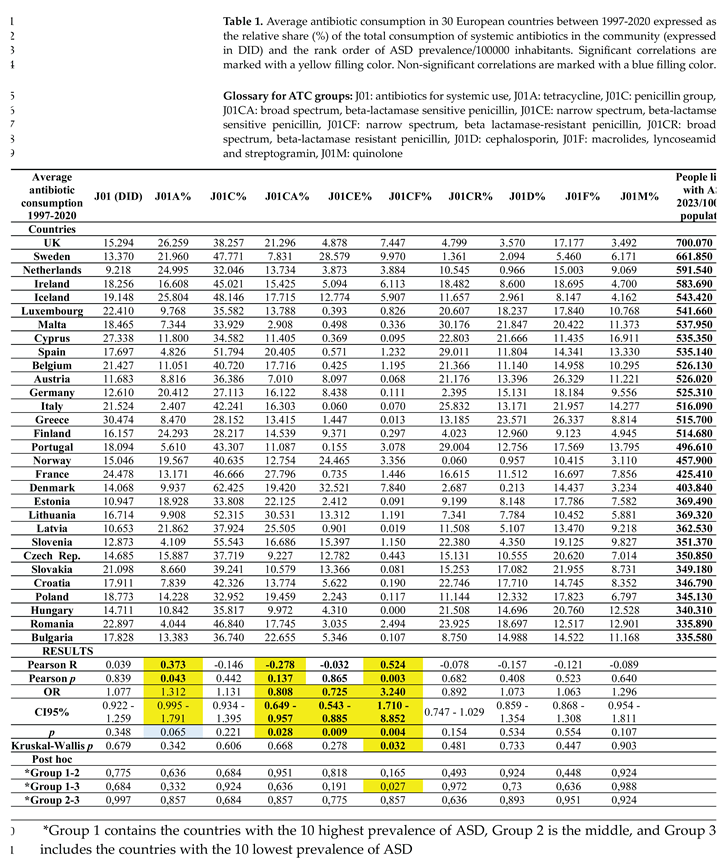

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Materials and Methods

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ziats CA, Patterson WG, Friez M. Syndromic Autism Revisited: Review of the Literature and Lessons Learned. Pediatr Neurol. 2021, 114:21-25. [CrossRef]

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z,. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018, 67:1-23. [CrossRef]

- Rapin I, Tuchman RF. Autism: definition, neurobiology, screening, diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008, 55:1129-46. [CrossRef]

- Kočovská E, Fernell E, Billstedt E, Minnis H, Gillberg C. Vitamin D and autism: clinical review. ResDev Disabil. 2012, 33:1541-50. [CrossRef]

- Rylaarsdam L, Guemez-Gamboa A. Genetic Causes and Modifiers of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019, 20;13:385. [CrossRef]

- Abrahams BS, Geschwind DH. Advances in autism genetics: on the threshold of a new neurobiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2008, 9:341-55. [CrossRef]

- Finegold SM, Downes J, Summanen PH. Microbiology of regressive autism. Anaerobe. 2012, 18:260-2. [CrossRef]

- Finegold SM. (2011) State of the art; microbiology in health and disease. Intestinal bacterial flora in autism. Anaerobe. 2011, 17:367-8. [CrossRef]

- Finegold SM. Therapy and epidemiology of autism--clostridial spores as key elements. Med Hypotheses, 2008, 70:508-11. [CrossRef]

- Pequegnat B, Sagermann M, Valliani M, Toh M, Chow H, Allen-Vercoe E, et al. A vaccine and diagnostic target for Clostridium bolteae, an autism-associated bacterium. Vaccine. 2013, 31:2787-90. [CrossRef]

- Finegold SM. Desulfovibrio species are potentially important in regressive autism. Med Hypotheses, 2011, 77:270-4. [CrossRef]

- Heberling CA, Dhurjati PS, Sasser M. Hypothesis for a systems connectivity model of Autism Spectrum Disorder pathogenesis: links to gut bacteria, oxidative stress, and intestinal permeability. Med Hypotheses. 2013 80:264-70. [CrossRef]

- Zafeiriou DI, Ververi A, Vargiami E. Childhood autism and associated comorbidities. Brain Dev. 2007, 29:257-72. [CrossRef]

- Webb SJ, Mourad PD. Prenatal Ultrasonography and the Incidence of Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172:319-320. [CrossRef]

- Richmond BJ. Hypothesis: conjugate vaccines may predispose children to autism spectrum disorders. Med Hypotheses. 2011, 77:940-7. [CrossRef]

- Steinman G, Mankuta D. Insulin-like growth factor and the etiology of autism. Med Hypotheses. 2013, 80:475-80. [CrossRef]

- Odent M. (2010) Autism and anorexia nervosa: Two facets of the same disease? Med Hypotheses. 75(1):79-81. [CrossRef]

- Herbert MR, Sage C. Autism and EMF? Plausibility of a pathophysiological link part II. Pathophysiology. 2013, 20:211-34. [CrossRef]

- Good P. Evidence the U.S. autism epidemic initiated by acetaminophen (Tylenol) is aggravated by oral antibiotic amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) and now exponentially by herbicide glyphosate (Roundup). Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018, 23:171-183. [CrossRef]

- Marchezan J. Editorial: Autism Spectrum Disorder and Autoimmune Diseases: A Pathway in Common? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019, 58:481-483. [CrossRef]

- Gottfried C, Bambini-Junior V, Francis F, Riesgo R, Savino W. The Impact of Neuroimmune Alterations in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Psychiatry, 2015, 6:121. [CrossRef]

- Mead J, Ashwood P. Evidence supporting an altered immune response in ASD. Immunol Lett. 2015, 163:49-55. [CrossRef]

- Wing L. The autistic spectrum. Lancet. 1997, 350:1761-6. [CrossRef]

- Caronna EB, Milunsky JM, Tager-Flusberg H. Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers. Arch Dis Child. 2008, 93:518-23. [CrossRef]

- Phillips KL, Schieve LA, Visser S, Boulet S, Sharma AJ, Kogan MD, et al Prevalence and impact of unhealthy weight in a national sample of US adolescents with autism and other learning and behavioral disabilities. Matern Child Health J. 2014, 18:1964-75. [CrossRef]

- Sharon G, Cruz NJ, Kang DW, Gandal MJ, Wang B, Kim YM, et al Human Gut Microbiota from Autism Spectrum Disorder Promote Behavioral Symptoms in Mice. Cell. 2019, 30:1600-1618.e17. [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju K, Sudeep KS, Kurhekar MP. A cellular automaton model to find the risk of developing autism through gut-mediated effects. Comput Biol Med. 2019, 110:207-217. [CrossRef]

- Weston B, Fogal B, Cook D, Dhurjati P. An agent-based modeling framework for evaluating hypotheses on risks for developing autism: effects of the gut microbial environment. Med Hypotheses. 2015, 84:395-401. [CrossRef]

- Finegold SM, Dowd SE, Gontcharova V, Liu C, Henley KE, Wolcott RD, et al 3rd. Pyrosequencing study of fecal microflora of autistic and control children. Anaerobe. 2010, 16:444-53. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis M, Piccolo M, Vannini L, Siragusa S, De Giacomo A, Serrazzanetti DI, et al Fecal microbiota and metabolome of children with autism and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. PLoS One. 2013, 8:e76993. [CrossRef]

- Finegold SM, Molitoris D, Song Y, Liu C, Vaisanen ML, Bolte E, et al Gastrointestinal microflora studies in late-onset autism. Clin Infect Dis. 2002, 35(Suppl 1):S6-S16. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Christophersen CT, Sorich MJ, Gerber JP, Angley MT, Conlon MA. Elevated fecal short chain fatty acid and ammonia concentrations in children with autism spectrum disorder. Dig Dis Sci. 2012, 57:2096-102. [CrossRef]

- Parracho HM, Bingham MO, Gibson GR, McCartney AL. Differences between the gut microflora of children with autistic spectrum disorders and that of healthy children. J Med Microbiol. 2005, 54:987- 991. [CrossRef]

- Andreo-Martínez P, García-Martínez N, Sánchez-Samper EP, Martínez-González AE. An approach to gut microbiota profile in children with autism spectrum disorder. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2020, 12:115-135. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Bolte ER. Autism and Clostridium tetani. Med Hypotheses. 1998, 51:133-44. [CrossRef]

- Tomova A, Husarova V, Lakatosova S, Bakos J, Vlkova B, Babinska K, et al Gastrointestinal microbiota in children with autism in Slovakia. Physiol Behav. 2015, 138:179-87. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis M, Francavilla R, Piccolo M, De Giacomo A, Gobbetti M. Autism spectrum disorders and intestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2015, 6:207-13. [CrossRef]

- Persico AM, Napolioni V. Urinary p-cresol in autism spectrum disorder. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2013, 36:82-90. [CrossRef]

- Macfabe DF. Short-chain fatty acid fermentation products of the gut microbiome: implications in autism spectrum disorders. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2012, 24;23. [CrossRef]

- Cryan JF, O'Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, Sandhu KV, Bastiaanssen TFS, Boehme M, et al The Microbiota- Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev. 2019, 99:1877-2013. [CrossRef]

- Roullet FI, Wollaston L, Decatanzaro D, Foster JA. Behavioral and molecular changes in the mouse in response to prenatal exposure to the anti-epileptic drug valproic acid. Neuroscience. 2010, 170:514-22. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Bek MK, Prince NZ, Peralta Marzal LN, Garssen J, Perez Pardo P, Kraneveld AD. The Role of Bacterial-Derived Aromatic Amino Acids Metabolites Relevant in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Front Neurosci. 2021, 15:738220. [CrossRef]

- Atladóttir HÓ, Henriksen TB, Schendel DE, Parner ET. Autism after infection, febrile episodes, and antibiotic use during pregnancy: an exploratory study. Pediatrics. 2012 130(6):e1447-54. [CrossRef]

- Niehus, R., and Lord, C. Early medical history of children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2006, 2(Suppl.), S120–S127. [CrossRef]

- Davidovitch M, Slobodin O, Weisskopf MG, Rotem RS. Age-Specific Time Trends in Incidence Rates of Autism Spectrum Disorder Following Adaptation of DSM-5 and Other ASD-Related Regulatory Changes in Israel. Autism Res. 2020, 13:1893-1901. [CrossRef]

- Sandler RH, Finegold SM, Bolte ER, Buchanan CP, Maxwell AP, Väisänen ML, et al Short-term benefit from oral vancomycin treatment of regressive-onset autism. J Child Neurol. 2000, 15:429-35. [CrossRef]

- Nitschke AS, do Valle HA, Vallance BA, Bickford C, Ip A, Lanphear N, Lanphear B, Weikum W, Oberlander TF, Hanley GE. Association between prenatal antibiotic exposure and autism spectrum disorder among term births: A population-based cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2023 Aug;37(6):516-526. [CrossRef]

- Diamanti T, Prete R, Battista N, Corsetti A, De Jaco A. Exposure to Antibiotics and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Could Probiotics Modulate the Gut-Brain Axis? Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Dec 7;11(12):1767. [CrossRef]

- Hermansson H, Kumar H, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E, Rautava S. Breast Milk Microbiota Is Shaped by Mode of Delivery and Intrapartum Antibiotic Exposure. Front Nutr. 2019 Feb 4;6:4. [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, S.; Pike, K.; Jones, D.R.; Brocklehurst, P.; Marlow, N.; Salt, A.; Taylor, D.J. Childhood outcomes after prescription of antibiotics to pregnant women with spontaneous preterm labor: 7-year follow-up of the ORACLE II trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 1319–1327.

- Duong QA, Pittet LF, Curtis N, Zimmermann P. Antibiotic exposure and adverse long-term health outcomes in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2022 85, 213-300. [CrossRef]

- Volker E, Tessier C, Rodriguez N, Yager J, Kozyrskyj A. Pathways of atopic disease and neurodevelopmental impairment: assessing the evidence for infant antibiotics. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022, 18, 901-922. [CrossRef]

- Fallon J. Could one of the most widely prescribed antibiotics, amoxicillin/clavulanate "augmentin," be a risk factor for autism? Med Hypotheses. 2005, 64, 312-5. [CrossRef]

- Köhler O, Petersen L, Mors O, Mortensen PB, Yolken RH, Gasse C, Benros ME. Infections and exposure to anti-infective agents and the risk of severe mental disorders: a nationwide study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017, 135, 97-105. [CrossRef]

- Slykerman, R.F.; Thompson, J. Waldie, K.E.; Murphy, R. Wall, C. Mitchell, E.A. Antibiotics in the first year of life and subsequent neurocognitive outcomes. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 87–94.

- Hamad AF, Alessi-Severini S, Mahmud SM, Brownell M, Kuo IF. Antibiotic Exposure in the First Year of Life and the Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 1923-1931. [CrossRef]

- Slob EMA, Brew BK, Vijverberg SJH, Dijs T, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Koppelman GH et al, Early-life antibiotic use and risk of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: results of a discordant twin study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021 50, 475-484. [CrossRef]

- Łukasik J, Patro-Gołąb B, Horvath A, Baron R, Szajewska H; SAWANTI Working Group. Early Life Exposure to Antibiotics and Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019. 49, 3866-3876. [CrossRef]

- Socała K, Doboszewska U, Szopa A, Serefko A, Włodarczyk M, Zielińska A, et al, The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2021, 172:105840. [CrossRef]

- Cryan JF, O'Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, Sandhu KV, Bastiaanssen TFS, Boehme M, et al, The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev. 2019, 99, 1877-2013. [CrossRef]

- Sharon G, Cruz NJ, Kang DW, Gandal MJ, Wang B, Kim YM, Zink EM, et al, Human Gut Microbiota from Autism Spectrum Disorder Promote Behavioral Symptoms in Mice. Cell. 2019, 177, 1600- 1618.e17. [CrossRef]

- Żebrowska P, Łaczmańska I, Łaczmański Ł. Future Directions in Reducing Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children With ASD Using Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021, 11:630052. [CrossRef]

- Abuaish S, Al-Otaibi NM, Aabed K, Abujamel TS, Alzahrani SA, Alotaibi SM, et al The Efficacy of Fecal Transplantation and Bifidobacterium Supplementation in Ameliorating Propionic Acid- Induced Behavioral and Biochemical Autistic Features in Juvenile Male Rats. J Mol Neurosci. 2022, 72, 372-381. [CrossRef]

- Johnson D, Letchumanan V, Thurairajasingam S, Lee LH. A Revolutionizing Approach to Autism Spectrum Disorder Using the Microbiome. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1983. [CrossRef]

- Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, Grigoryan Z, Dominguez-Bello MG. The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends Mol Med. 2015, 21, 109-17. [CrossRef]

- Kang DW, Adams JB, Gregory AC, Borody T, Chittick L, Fasano A, et al Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome. 2017, 5, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn M, Grave S, Bransfield R, Harris S. Long-term antibiotic therapy may be an effective treatment for children co-morbid with Lyme disease and autism spectrum disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012, 78, 606-15. [CrossRef]

- Rodakis J. An n=1 case report of a child with autism improving on antibiotics and a father's quest to understand what it may mean. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015 26:26382. [CrossRef]

- Mintál K, Tóth A, Hormay E, Kovács A, László K, Bufa A, et al Novel probiotic treatment of autism spectrum disorder associated social behavioral symptoms in two rodent models. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 5399. [CrossRef]

- Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, Grigoryan Z, Dominguez-Bello MG. The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends Mol Med. 2015, 21:109-17. [CrossRef]

- Steinman G. The putative etiology and prevention of autism. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2020, 173:1-34. [CrossRef]

- Hamad AF, Alessi-Severini S, Mahmud SM, Brownell M, Kuo IF. Prenatal antibiotics exposure and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2019, 14:e0221921. [CrossRef]

- Abelson N, Meiri G, Solomon S, Flusser H, Michaelovski A, Dinstein I, et al Association Between Antenatal Antimicrobial Therapy and Autism Spectrum Disorder-A Nested Case-Control Study. Front Psychiatry. 2021, 12, 771232. [CrossRef]

- Volkova A, Ruggles K, Schulfer A, Gao Z, Ginsberg SD, Blaser MJ. Effects of early-life penicillin exposure on the gut microbiome and frontal cortex and amygdala gene expression. Science, 2021, 24, 102797. [CrossRef]

- Leclercq S, Mian FM, Stanisz AM, Bindels LB, Cambier E, Ben-Amram H, et al. Low-dose penicillin in early life induces long-term changes in murine gut microbiota, brain cytokines and behavior. Nat Commun. 2017, 8,15062. [CrossRef]

- Dhudasia MB, Flannery DD, Pfeifer MR, Puopolo KM. (2021) Updated Guidance: Prevention and Management of Perinatal Group B Streptococcus Infection. Neoreviews. 2021, (3):e177-e188. [CrossRef]

- Amangelsin Y, Semenova Y, Dadar M, Aljofan M, Bjørklund G. The Impact of Tetracycline Pollution on the Aquatic Environment and Removal Strategies. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023, 12, 440. [CrossRef]

- Lee BK, Magnusson C, Gardner RM, Blomström Å, Newschaffer CJ, Burstyn I, et al Maternal hospitalization with infection during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2015, 44, 100-5. [CrossRef]

- Brown AS, Sourander A, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, McKeague IW, Sundvall J, Surcel HM. Elevated maternal C-reactive protein and autism in a national birth cohort. Mol Psychiatry. 2014, 19, 259-64. [CrossRef]

- Atladóttir HO, Thorsen P, Østergaard L, Schendel DE, Lemcke S, Abdallah M, et al Maternal infection requiring hospitalization during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010, 40, 1423-30. [CrossRef]

- Choi GB, Yim YS, Wong H, Kim S, Kim H, Kim SV, et al. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science, 2016, 26;351, 933-9. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Kim H, Yim YS, Ha S, Atarashi K, Tan TG, et al Maternal gut bacteria promote neurodevelopmental abnormalities in mouse offspring. Nature, 2017, 28;549(7673):528-532. [CrossRef]

- Rose DR, Yang H, Serena G, Sturgeon C, Ma B, Careaga M, et al, Differential immune responses and microbiota profiles in children with autism spectrum disorders and co-morbid gastrointestinal symptoms. Brain Behav Immun. 2018, 70, 354-368. [CrossRef]

- Vuong HE, Hsiao EY. Emerging Roles for the Gut Microbiome in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2017, 81, 411-423. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Li J, Wu F, Zheng H, Peng Q, Zhou H. Altered composition and function of intestinal microbiota in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2019, 9, 43. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wan GB, Huang MS, Agyapong G, Zou TL, Zhang XY, Liu YW, Song YQ, Tsai YC, Kong XJ. Probiotic Therapy for Treating Behavioral and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Curr Med Sci. 2019, 39, 173-184. [CrossRef]

- Duque ALRF, Demarqui FM, Santoni MM, Zanelli CF, Adorno MAT, Milenkovic D, et al, Effect of probiotic, prebiotic, and synbiotic on the gut microbiota of autistic children using an in vitro gut microbiome model. Food Res Int. 2021, 149:110657. [CrossRef]

- Tan Q, Orsso CE, Deehan EC, Kung JY, Tun HM, Wine E, et al, Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of behavioral symptoms of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 1820-1836. [CrossRef]

- Yap CX, Henders AK, Alvares GA, Wood DLA, Krause L, Tyson GW, et al Autism-related dietary preferences mediate autism-gut microbiome associations. Cell. 2021 Nov 24;184(24):5916-5931.e17. [CrossRef]

- Andreo-Martínez P, García-Martínez N, Sánchez-Samper EP, Martínez-González AE. An approach to gut microbiota profile in children with autism spectrum disorder. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2020 Apr;12(2):115-135. [CrossRef]

- Karin Rystedt, Petra Edquist, Christian G Giske, Katarina Hedin, Mia Tyrstrup, Gunilla Skoog Ståhlgren, et al, Effects of penicillin V on the fecal microbiota in patients with pharyngotonsillitis— an observational study, JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance, Volume 5, Issue 1, February 2023, dlad006. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor R, Moloney GM, Fulling C, O'Riordan KJ, Fitzgerald P, Bastiaanssen TFS, et al. Maternal antibiotic administration during a critical developmental window has enduring neurobehavioural effects in offspring mice. Behav Brain Res. 2021, 404:113156. [CrossRef]

- Njotto LL, Simin J, Fornes R, Odsbu I, Mussche I, Callens S, et al. Maternal and Early-Life Exposure to Antibiotics and the Risk of Autism and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Childhood: a Swedish Population-Based Cohort Study. Drug Saf. 2023, 46, 467-478. [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewski J, Mamun N, Czaja K. Bidirectional Interaction between Tetracyclines and Gut Microbiome. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023, 12(9):1438. [CrossRef]

- Ai Y, Zhao J, Shi J, Zhu TT. Antibiotic exposure and childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021 238(11):3055- 3062. [CrossRef]

- Choi A, Lee H, Jeong HE, Lee SY, Kwon JS, Han JY, et al. Association between exposure to antibiotics during pregnancy or early infancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disorder, language disorder, and epilepsy in children: population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2024 May 22;385:e076885. [CrossRef]

- Love C, Sominsky L, O'Hely M, Berk M, Vuillermin P, Dawson SL. Prenatal environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorder and their potential mechanisms. BMC Med. 2024, 16;22(1):393. [CrossRef]

- Di Gesù CM, Buffington SA. The early life exposome and autism risk: a role for the maternal microbiome? Gut Microbes. 2024 16(1):2385117. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Xiao P, Cao R, Le J, Xu Q, Xiao F, Ye L, Wang X, Wang Y, Zhang T. Effects and microbiota changes following oral lyophilized fecal microbiota transplantation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Pediatr. 2024, 9;12:1369823. [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 Autism Spectrum Collaborators. The global epidemiology and health burden of the autism spectrum: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Psyducts referred to in the content.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).