1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the most critical health issues, claiming numerous lives worldwide regardless of gender or age [

1,

2]. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy, as two of the most potent strategies, are employed to mitigate, stop, and eliminate cancerous tumors [

3]. In both methods, anticancer drugs must act on the cancerous tumors and destroy them. To achieve this goal, drugs such as Cisplatin [

4] must be carried by drug carriers to reach the cancerous tumors. Near the cancerous tumors, the walls of the drug carriers break down under endogenous stimuli (e.g., changes in pH or redox gradients) or exogenous stimuli (e.g., temperature, magnetic fields, sound, or light waves), resulting in the release of the drug [

5,

6]. Consequently, the drug acts on the cancerous tumors, damaging and deactivating them. This strategy ensures that the active anticancer drug is delivered directly to the tumors while minimizing its interaction with healthy tissues. As a result, the treatment's effectiveness increases, and the response time is reduced. In these methods, both the drug carriers and the drug release mechanisms play critical roles and must be carefully chosen for each purpose.

Drug carriers are biocompatible cages that encapsulate anticancer drugs, keeping them safe and preventing contact with healthy tissues from the point of injection until the release stage [

7,

8,

9,

10]. They are typically designed using nanoparticles, nanotubes, nanocapsules, dendrimers, liposomes, hydrogels, or natural drug carriers [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The drug release stage involves the controlled release of drugs and their delivery to cancerous tumors under endogenous or exogenous stimuli [

16,

17,

18]. Both of these components need to be accurately understood and carefully selected for use in drug delivery systems. In recent decades, significant progress in this field has been achieved through global research efforts [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. As a state-of-the-art result, nanocapsules have been reported as efficient nanocarriers [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], and bubble cavitation [

19,

20,

21] has been identified as an effective method for their release.

Nanocapsules, due to their small scale and self-assembly characteristics, can be promising candidates for drug carrier applications. Previous studies on these aspects have revealed that for two-end-open nanocapsules, commonly known as nanotubes, the releasing agent can be designed based on iron and gold nanowires [

4,

23]. Doping the wall of drug carriers affects the drug-releasing process [

4]. The well-known materials used for carriers include carbon, silicon-carbide, and boron-nitride [

4,

22,

23,

25,

27]. The anticancer drugs that these carriers can carry include temozolomide and carmustine for silicon-carbide [

22], cisplatin [

22], gemcitabine [

23], and antimicrobial peptides [

25] for carbon materials, as well as all of the above for boron-nitride [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Moreover, the self-assembly of nanocapsules in pure water facilitates the encapsulation of anticancer drugs within their carriers, demonstrating the practical applicability of nanocapsules [

24]. Although these studies provide in-depth knowledge regarding drug carriers, the diffusion of these carriers, which signifies their mobility in locating and reaching cancerous tumors from the injection to delivery stages in the human body, remains almost unclear and needs to be addressed.

In the case of cavitation bubbles used during the drug release stage, the literature [

19,

20,

21,

33,

34] reveals that the emission of acoustic waves near cancerous tumors, induces nano- and micro-bubbles by changing the pressure of the liquid surrounding the tumors through expansion and contraction cycles. These induced bubbles collapse, creating jets directed toward the carriers or the cancerous tumors. The impact of the jet on the carriers leads to their rupture and the release of anticancer drugs. In contrast, the direct effect of the jet on the cancerous tumors causes damage, and over prolonged treatment times, it eventually leads to deactivation. However, the mechanisms of jet formation and its effects on the carriers remain unclear and require further investigation.

To address these two main aspects (diffusion phenomena and drug release by nanobubble cavitation), the current study focuses on the diffusivity behavior of carbon and boron-nitride nanocapsules in pure water in the first section. Subsequently, the effects of nanobubble cavitation on nanocapsules will be investigated to provide a clearer insight into the interaction between drug carriers and the nanojets formed after the collapse of nanobubbles. All analyses will be conducted using the molecular dynamics (MD) method, a powerful technique for drug delivery research [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Carbon and boron-nitride nanocapsules were chosen due to their applicability in carrying a wide range of anticancer drugs. At the same time, water was chosen as the medium because the human body is primarily composed of water. The results obtained from the first section will aid in selecting the optimal nanocapsule material for enhanced migration and drug-carrying efficiency. The results from the second section will elucidate the interaction of nanocapsules with nanojets at the atomic scale. The novelty of this paper lies in the investigation of the diffusion characteristics of nanocapsules and their interaction with nanojets, which can provide a deeper understanding of the underlying physics to advance drug delivery systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Configuration

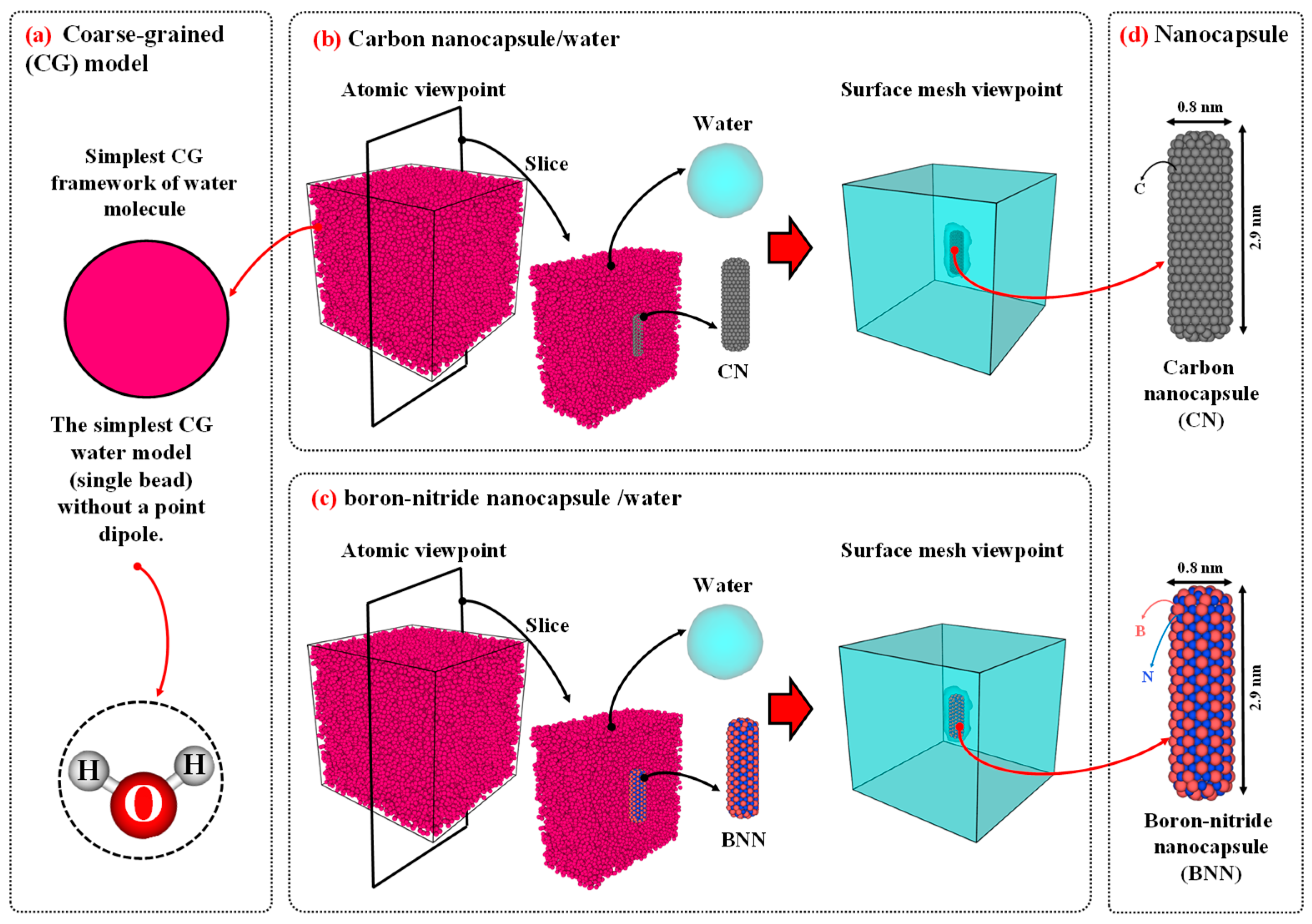

To model the water/nanocapsule configurations, water was defined using a coarse-grained (CG) approach [

35]. In contrast, the carbon nanocapsule (CN) and boron-nitride nanocapsule (BNN) were modeled in an all-atom approach, with chiral indices of (n=6, m=6), diameters of 0.8 nanometers (nm), and lengths of 2.9 nm. Using similar nanocapsules allows for a comparable evaluation of the diffusion properties of both, helping to determine which is more suitable for drug carrier applications. The size of the simulation box for the diffusion study was set to 10×10×10 nm

3, which is sufficiently large to maintain the bulk behavior of pure water [

36]. The nanocapsules (CN or BNN) were placed at the center of the simulation box, and the remaining space was filled with water molecules at a density of 0.997 g/cm

3 [

37,

38] in two independent simulations (one for CN/water and the other for BNN/water).

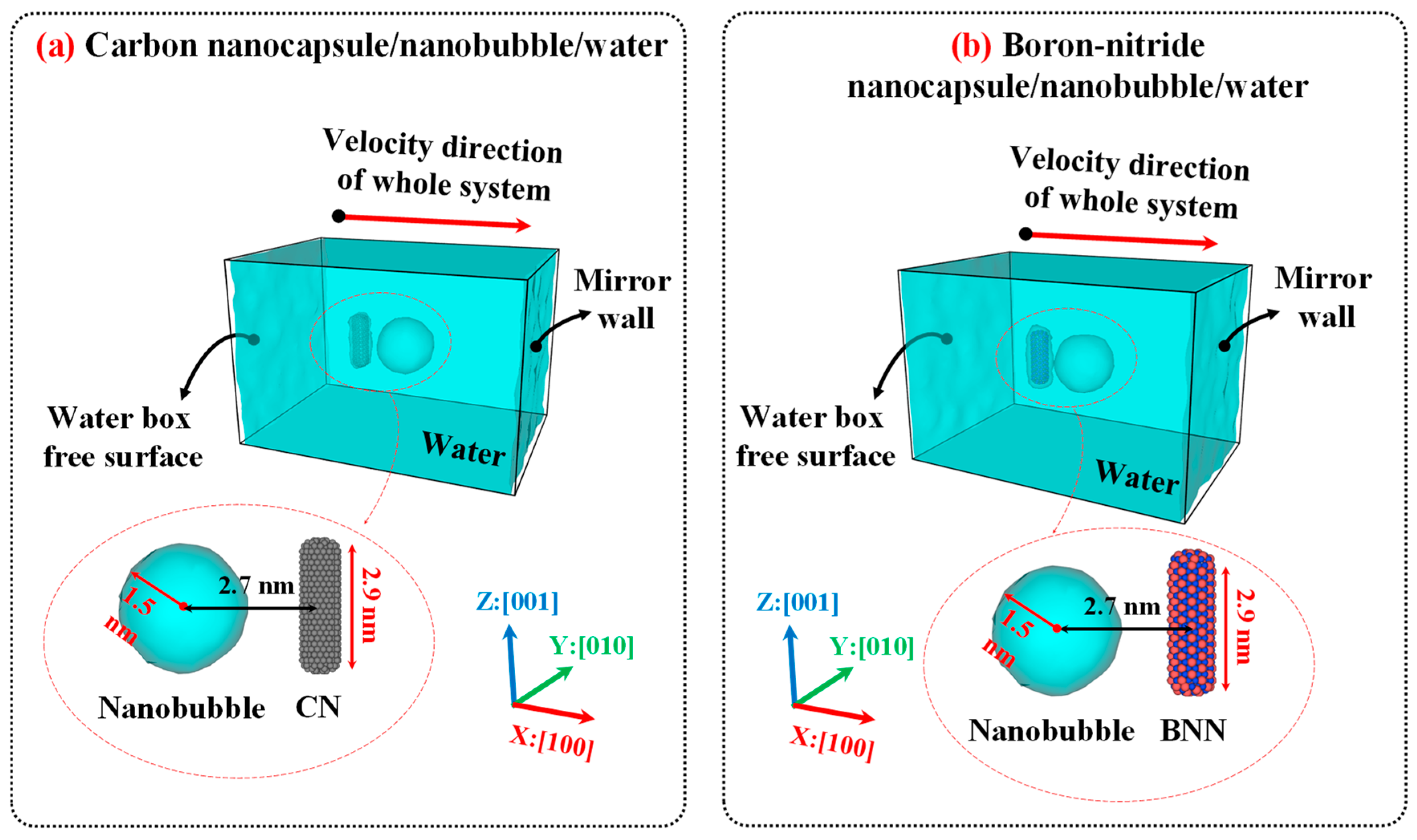

Figure 2 illustrates the initial configurations of CN/water and BNN/water. The configuration for studying bubble cavitation effects is similar to that used in the diffusion simulations; however, the simulation box was set to 10×10×15 nm

3 to provide sufficient space for shock wave propagation and interaction with the nanocapsules.

Figure 3 illustrates the initial configurations used for nanobubble cavitation studies.

2.2. Interatomic Potential

To model the interaction between carbon (C) atoms in CN, the adaptive intermolecular reactive empirical bond order (AIREBO) potential was used [

39,

40]. This potential can accurately predict the physical properties of low-dimensional carbon materials. For modeling the interaction between boron (B) atoms and nitrogen (N) atoms, as well as B–N interactions in BNN, the extended bond-order Tersoff potential [

41] was employed due to its accuracy in modeling interactions within this system and its ability to account for the formation and breaking of B–N bonds [

42]. The interaction between water molecules was also modeled using the CG approach proposed by Zavadlav et al. [

35]. This potential can reproduce the thermodynamic properties of water closely to all-atom models while significantly reducing computational costs, making it useful for simulating large systems [

37]. The interaction between water CG beads and C, B, and N atoms was defined by non-bonding Lennard-Jones “12/6” potentials using the Lorentz– Berthelot mixing rules [

36] to model water–solid interphase interactions [

35,

43].

Figure 1.

a) The schematic of coarse-grained (CG) model. The initial configurations of (b) carbon nanocapsule (CN)/water and (c) boron-nitride nanocapsule (BNN)/water. (d) Carbon and boron-nitride nanocapsules were modeled in an all-atom approach, with chiral indices of (n=6, m=6), diameters of 0.8 nanometers (nm), and lengths of 2.9 nm. The size of the simulation was set to 10×10×10 nm3 and filled with water CG bead corresponding to 0.997 g/cm3.

Figure 1.

a) The schematic of coarse-grained (CG) model. The initial configurations of (b) carbon nanocapsule (CN)/water and (c) boron-nitride nanocapsule (BNN)/water. (d) Carbon and boron-nitride nanocapsules were modeled in an all-atom approach, with chiral indices of (n=6, m=6), diameters of 0.8 nanometers (nm), and lengths of 2.9 nm. The size of the simulation was set to 10×10×10 nm3 and filled with water CG bead corresponding to 0.997 g/cm3.

Figure 2.

Initial configuration of (a) carbon nanocapsule (CN)/nanobubble/water and (b) boron-nitride nanocapsules (BNN)/nanobubble/water after creating nanobubble. Carbon and boron-nitride nanocapsules were modeled in an all-atom approach, with chiral indices of (n=6, m=6), diameters of 0.8 nanometers (nm), and lengths of 2.9 nm. The size of the simulation was set to 10×10×15 nm3 and filled with water CG bead corresponding to 0.997 g/cm3. The distance between the center of the nanobubble and the axis of the nanocapsules was set to 2.7 nm. The initial radius of the nanobubble is 1.5 nm. The gamma distance (the relative wall distance, defined as the distance between the center of the nanobubble and the axis of the nanocapsules (2.7 nm) divided by the radius of the nanobubble (1.5 nm)) is equal to 1.8.

Figure 2.

Initial configuration of (a) carbon nanocapsule (CN)/nanobubble/water and (b) boron-nitride nanocapsules (BNN)/nanobubble/water after creating nanobubble. Carbon and boron-nitride nanocapsules were modeled in an all-atom approach, with chiral indices of (n=6, m=6), diameters of 0.8 nanometers (nm), and lengths of 2.9 nm. The size of the simulation was set to 10×10×15 nm3 and filled with water CG bead corresponding to 0.997 g/cm3. The distance between the center of the nanobubble and the axis of the nanocapsules was set to 2.7 nm. The initial radius of the nanobubble is 1.5 nm. The gamma distance (the relative wall distance, defined as the distance between the center of the nanobubble and the axis of the nanocapsules (2.7 nm) divided by the radius of the nanobubble (1.5 nm)) is equal to 1.8.

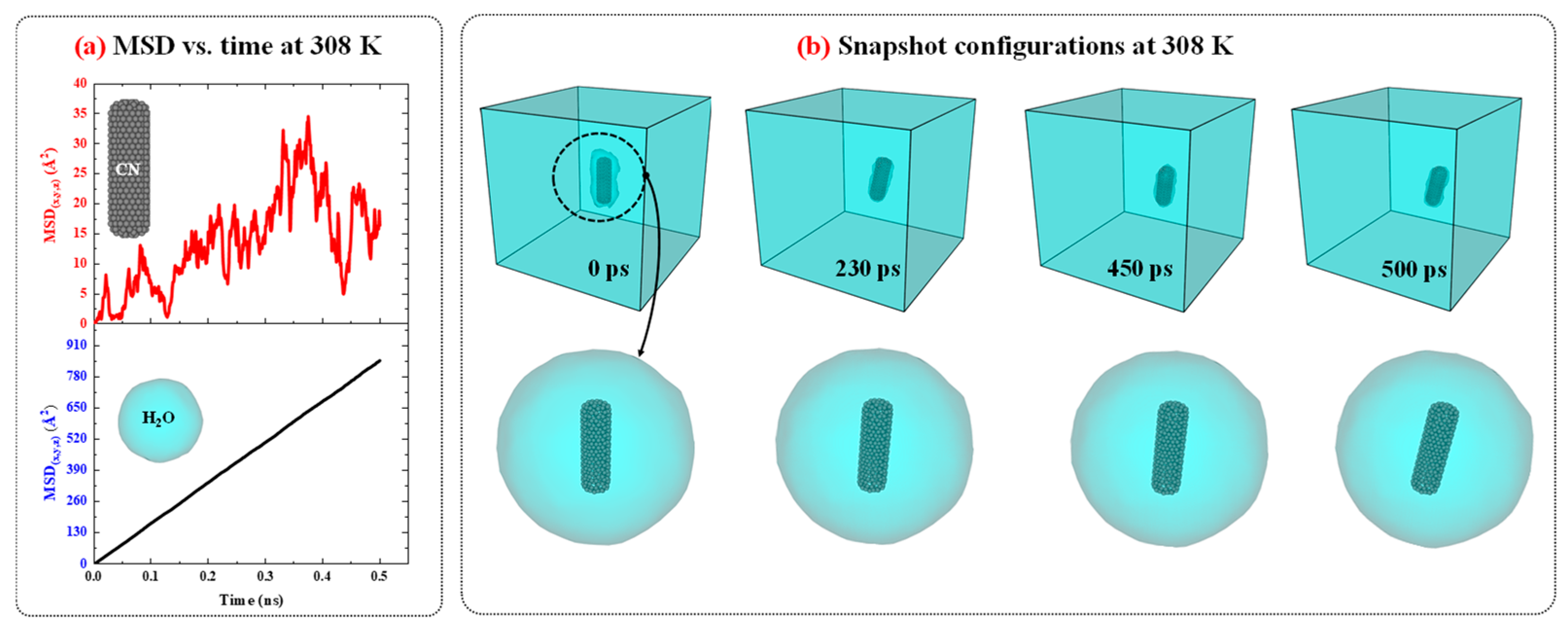

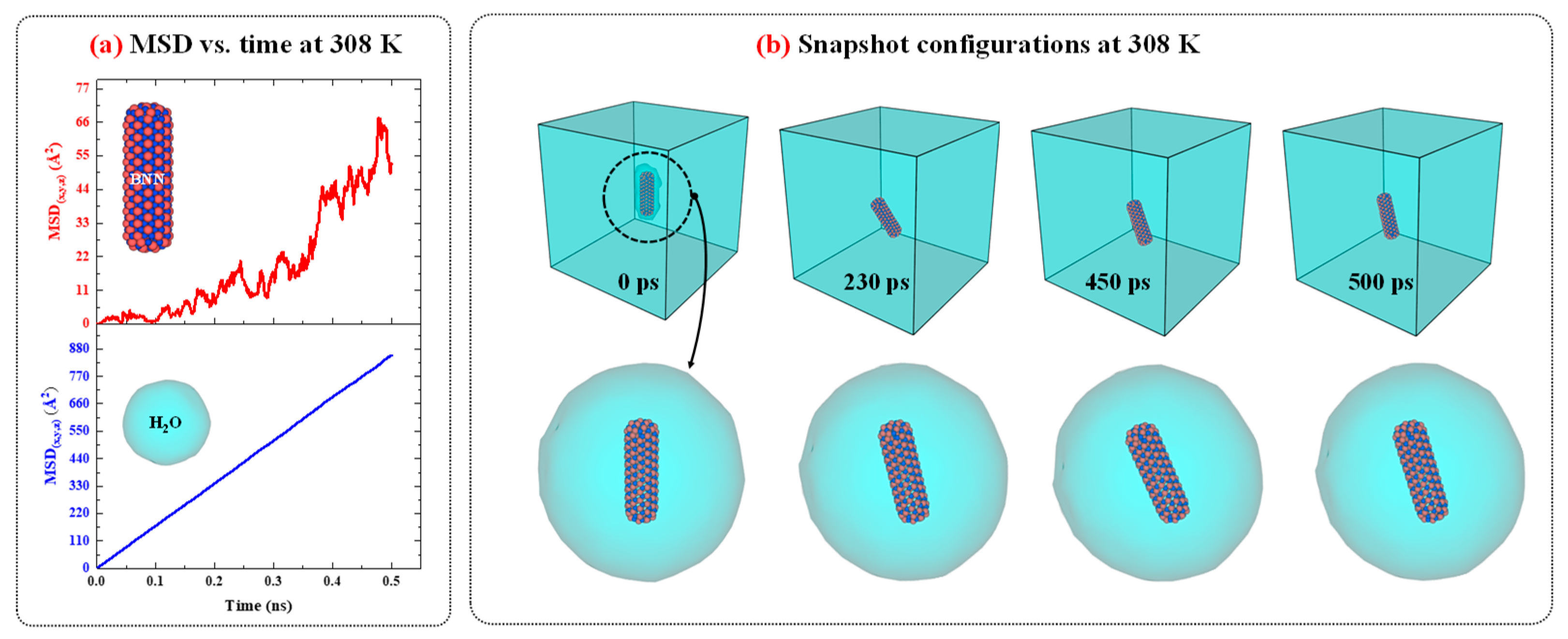

Figure 3.

a) The MSD vs. time diagrams for CN and water in CN/water system at 308 K and 1 atm. (b) The snapshots configuration of CN/water system at 308 K and 1 atm as function of time.

Figure 3.

a) The MSD vs. time diagrams for CN and water in CN/water system at 308 K and 1 atm. (b) The snapshots configuration of CN/water system at 308 K and 1 atm as function of time.

2.3. Simulation Algorithm

All molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the LAMMPS package[

44], and OVITO [

45] software was used for visualization. Two separate algorithms were employed for diffusion and cavitation purposes. In the diffusion algorithm, the minimization, equilibrium, and diffusion stages were defined. In contrast, the cavitation algorithm replaced the final stage with a shock wave propagation stage. For computing diffusion properties, periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) were applied in all directions to ensure that the bulk behavior of water remained consistent near the boundaries. Prior to the main simulation, a combination of the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble and the Langevin thermostat was used to reduce the system's energy from a metastable to a stable microstate over 1 picosecond (ps) with a time step of 0.1 femtoseconds (fs) [

38]. After achieving the stable microstate, the NVE and Langevin thermostat were turned off, and the time step was changed to 1 fs. Subsequently, the isothermal–isobaric ensemble (NPT) with the desired temperature and a pressure of 1 atmosphere was applied to the system for 2 nanoseconds (ns) to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium. This time is sufficient to ensure the system reaches equilibrium. Finally, the NPT was turned off, and the NVE was used for 1 ns to calculate the diffusion coefficient. To evaluate diffusion as a function of temperature, the range of 288, 293, 298, 303, and 308 K was chosen, as these values are close to the operating temperature range of enzymes in the human body [

46,

47].

For nanobubble cavitation, the minimization and equilibration stages were performed as in the diffusion algorithm. However, after reaching thermodynamic equilibrium, a mirror-wall protocol was applied to generate a shock wave [

38]. The simulations for nanobubble cavitation were performed at 298 K and 1 atm. Periodic boundary conditions along x:[100] were replaced with fixed boundaries, and two virtual mirror walls were defined at the lower and upper faces of the simulation box in this direction. A spherical region (radius = 0.8 nm) was created near the nanocapsules, and all water molecules within it were removed, producing a void that served as the nanobubble. Using this method, the void nanobubble with a gamma distance (relative wall distance) of 1.8 was created. The vapor phase inside the bubble was not explicitly modeled because its density is extremely low; including it would slightly reduce the post-collapse jet pressure but would not change the qualitative cavitation behavior [

48]. The entire system was then given an initial center-of-mass velocity of 3 nm/ps (3 km/s) along the x:[100] axis toward the upper mirror wall. Upon impact, the water molecules reflected, reversing their momentum and generating a shock wave that propagated in the opposite direction along x:[

00]. When the shock front reached the nanobubble interface, the bubble collapsed, forming a water nanojet that impacted the nanocapsules.

2.4. Formal Analysis

In this study, two classes of formal analysis were utilized to investigate the diffusion behavior and the effects of cavitation. For the diffusion analysis, the mean square displacement (MSD), which reveals the displacement and diffusion of each particle (water CG bead, CN, and BNN), was computed during the diffusion stage and then plotted against simulation time to determine the diffusion coefficient. Eq. (1) illustrates the MSD equation used in the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation [

49,

50].

Here, is the number of particles for which the MSD is computed, denotes the position vector of the ith particle, signifies the time, and points to the initial time. The slope of the MSD versus time can be used to determine the diffusion coefficient based on the following equation:

where MSD is a function of time,

signifies the dimension,

D is the diffusion coefficient, and

is the thermodynamically sensitive factor that depends on temperature, density, impurities, or other environmental variables. For the cavitation part, the dynamics and phenomena were evaluated using visualization snapshots, velocity maps, pressure contours, and temperature profiles. Each of these formal analyses helps in revealing the cavitation dynamics and thermodynamic criteria during collapse, which facilitates the study of the interaction between nanobubbles and nanocapsules. More information regarding the post-processing analysis methods can be found elsewhere for shock wave and laser-induced cavitation methods [

37,

38].

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results obtained from this study and discusses them. In the first section, the verification of the simulation results is provided to demonstrate the validity of the algorithm and interatomic potentials. In the second and third sections, the diffusivity and the impact of nanobubble cavitation on the nanocapsules were investigated as properties of drug carriers and releasing agents, respectively. These sections facilitate understanding of the diffusion behavior of nanocapsules in pure water and help determine their suitability for rapid diffusion or navigation. Moreover, the investigation of the effects of nanobubble cavitation on nanocapsules, which are used as releasing agent, provides in-depth insight into the underlying physics of this phenomenon and will help improve the release process by understanding its behavior at the molecular scale. In the final section, the outlook and perspectives for future explorations are addressed.

3.1. Results Verification

To benchmark the simulation results and evaluate the accuracy of the computed diffusion coefficients, pure water, CN/water, and BNN/water systems were simulated under the diffusion algorithm at environment condition (298 K and 1 atm). Then, the

D of water molecules was calculated for each system and compared with previously reported data [

36,

51] in

Table 1. As shown in this table, the results obtained in the present study are in good agreement with the earlier data, indicating that the employed potential models and algorithm reliably predict the physical properties water. In addition, single nanobubble cavitation was simulated using the mirror-wall algorithm, and the results were in close agreement with previous findings [

38], demonstrating that the cavitation protocol functions correctly and can now be applied to nanocapsule/water systems. Thus, both the diffusion and cavitation algorithms are practical for achieving the objectives of the current study.

3.2. Nanocapsules Diffusivity as Drug Carrier Properties

3.2.1. Carbon Nanocapsules/Water System

Figure 3 presents the MSD versus time diagrams for CN and water in the CN/water system separately, and illustrates the snapshot configurations of this system at 308 K as a function of time. As shown in

Figure 3.a, the MSD of H

2O molecules increases linearly over time with a constant slope, indicating normal diffusion behavior. In contrast, for CN, the increase in MSD over time also suggests diffusion; however, the fluctuations are more pronounced compared to water. A more detailed analysis of the MSD diagrams suggests that these fluctuations may be attributed to changes in the orientation of the CN axis as well as the low concentration of CN in water.

To provide further evidence regarding this issue, the configuration snapshots over time were captured and plotted in

Figure 3.b. Based on this figure, the changes and rotational movements around the axis of the CN are observed over time and influence the MSD. Since, in MSD analysis, particle diffusion is the primary focus, and for water molecules, the rotational movements are smaller than their translational degrees of freedom, the significant contribution to diffusion is attributed to translational motion, resulting in MSD curves with lower thermal fluctuations. On the other hand, for CN, due to its low concentration in water, with only one CN present, the rotational degrees of freedom around its axis affect translational motion and induce fluctuations in the MSD curve. The diffusion behavior of the CN/water system at other temperatures is similar to that observed at 308 K; however, as temperature decreases, both the MSD values and the slopes of their curves decrease accordingly.

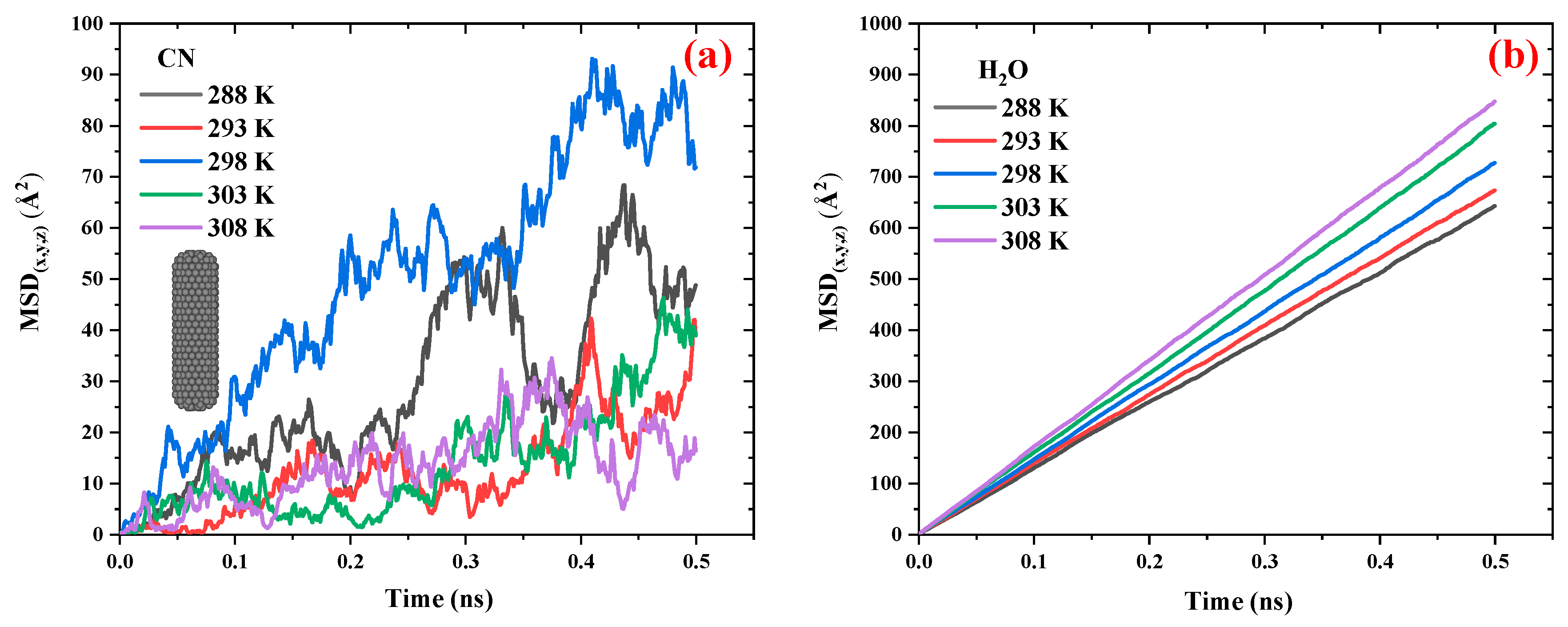

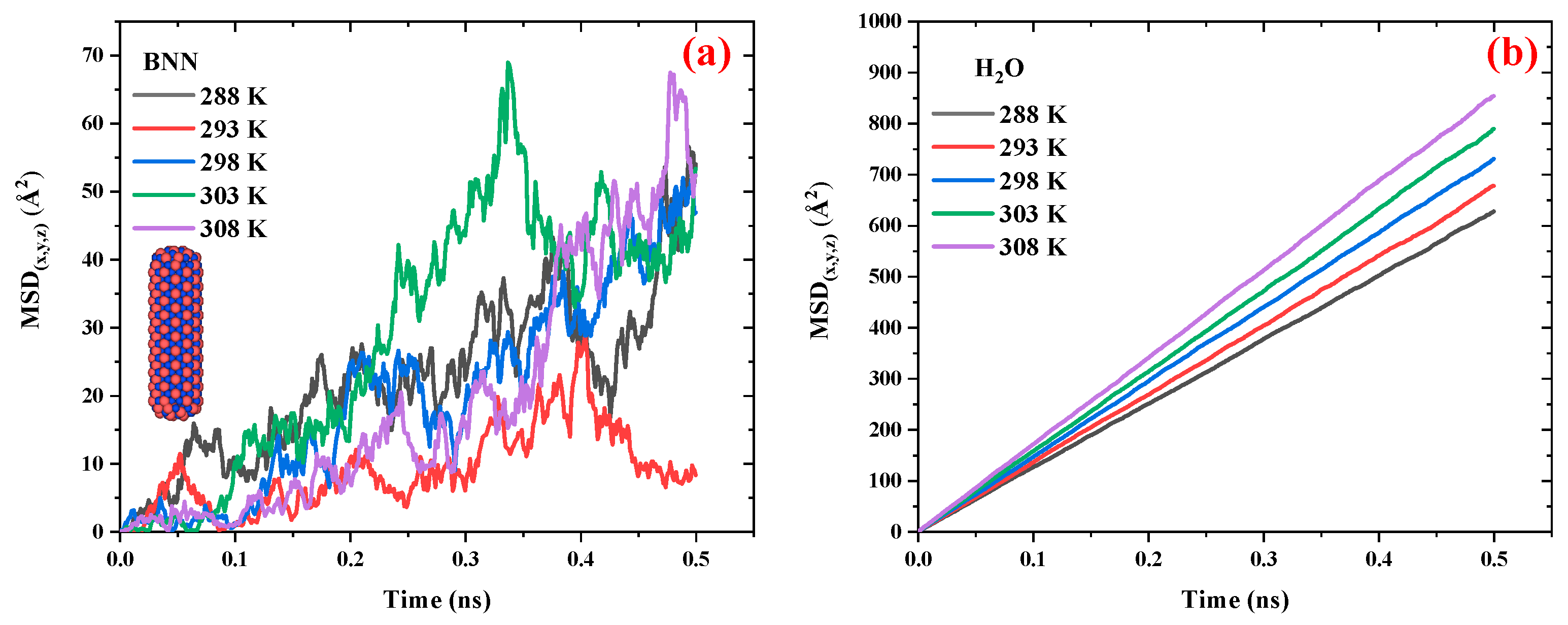

Figure 4 compares the MSD vs. time diagrams for CN and water in the CN/water system at different temperatures ranging from 288 to 308 K.

Figure 4.a illustrates that, with increasing temperature, the distance between the peaks and valleys of the MSD curves for CN decreases, resulting in a smoother trend. This behavior is attributed to the influence of temperature on CN diffusivity; as temperature increases, translational motion becomes the dominant mode of movement compared to rotational degrees of freedom, thereby reducing large fluctuations in the MSD curves. Although temperature does not exhibit a strictly linear effect on the slope of the MSD diagrams, a slight increase in slope is observed as the temperature rises from 288 K to 298 K. However, in the range from 298 K to 308 K, the slope remains relatively unchanged, indicating a nearly constant diffusion coefficient in this temperature interval.

Figure 4.b shows that the MSD of H

2O molecules in the CN/water system follows a more consistent and ordered pattern. With increasing temperature, the slope of the MSD curves increases, indicating enhanced diffusion of water molecules.

To evaluate the effect of temperature on the diffusion coefficients of CN and H

2O molecules in the CN/water system, the diffusion coefficients were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2) and

Figure 4 and were listed in

Table 2. This table compares the diffusion coefficients of CN and water in the CN/water system at various temperatures ranging from 298 to 308 K at a pressure of 1 atm. The data show that with a temperature increase of approximately 3.3%, the average diffusion coefficient of CN is around 0.1×10

-9 m

2.s

-1. In contrast, under the same temperature increase, the diffusion coefficient of H

2O increases from 2.16 to 2.83 ×10

-9 m

2.s

-1 (an approximate rise of 31%). These results indicate that temperature has a significantly greater effect on water molecules than on CN. Consequently, temperature alone cannot be effectively used as a navigational mechanism for directing CN delivery to cancerous tumors.

3.2.2. Boron-Nitride Nanocapsule/Water System

Figure 5 illustrates the MSD vs. time diagrams for BNN and water in the BNN/water system, separately, and shows the snapshot configurations of this system at 308 K as a function of time. The MSD behavior of BNN and water in the BNN/water system, along with the snapshot configuration analysis, reveals that BNN exhibits a similar diffusion pattern to CN when immersed in water. However, BNN shows lower fluctuations and greater diffusion, as indicated by the steeper slope of the MSD vs. time curve for BNN compared to CN at the same temperature in

Figure 5. The reduced thermal fluctuations of BNN, in comparison to CN, can be attributed to its lower rotational motion. Therefore, as rotational movements contribute less significantly, the translational movements dominate, resulting in increased diffusion.

Figure 6 compares the MSD vs. time diagrams for BNN and water in the BNN/water system at different temperatures ranging from 298 to 308 K.

Figures 6.a and 6.b present the MSD of BNN and H

2O molecules, respectively. A comparison of this figure with

Figure 4 shows that the behavior of the BNN/water system is similar to that of the CN/water system; however, BNN exhibits greater mobility than CN. In the case of water, the H₂O molecules display a similar diffusion pattern in the presence of both BNN and CN, suggesting that these nanocarriers have no significant effect on their surrounding medium. This outcome is advantageous for drug delivery applications, as it indicates that CN and BNN can be introduced into biological environments (composed primarily of water) without significantly disrupting the medium, while still serving effectively as drug carriers.

Table 3 compares the diffusion coefficients of BNN and water in the BNN/water system at various temperatures, ranging from 298 to 308 K, under a pressure of 1 atm. The results show that when the temperature increases by 3.3%, the diffusion coefficient of H

2O increases by 31%, while the diffusion coefficient of BNN remains unchanged. The diffusion coefficient of BNN across the temperature range of 298–308 K remains constant at 0.11×10

-9 m

2.s

-1 m²/s. This outcome suggests that temperature has no significant effect on the diffusivity of BNN, presenting both advantages and limitations for drug delivery systems. The advantage is that BNN, as a nanocarrier, can reach cancerous tumors regardless of local temperature fluctuations near tumor sites. Conversely, the limitation is that temperature cannot be used as a navigational stimulus to guide BNN toward specific targets, reducing the feasibility of thermally driven targeting strategies for this nanocarrier.

3.2.2. Comparison of the Diffusivity of Carbon and Boron-Nitride Nanocapsules

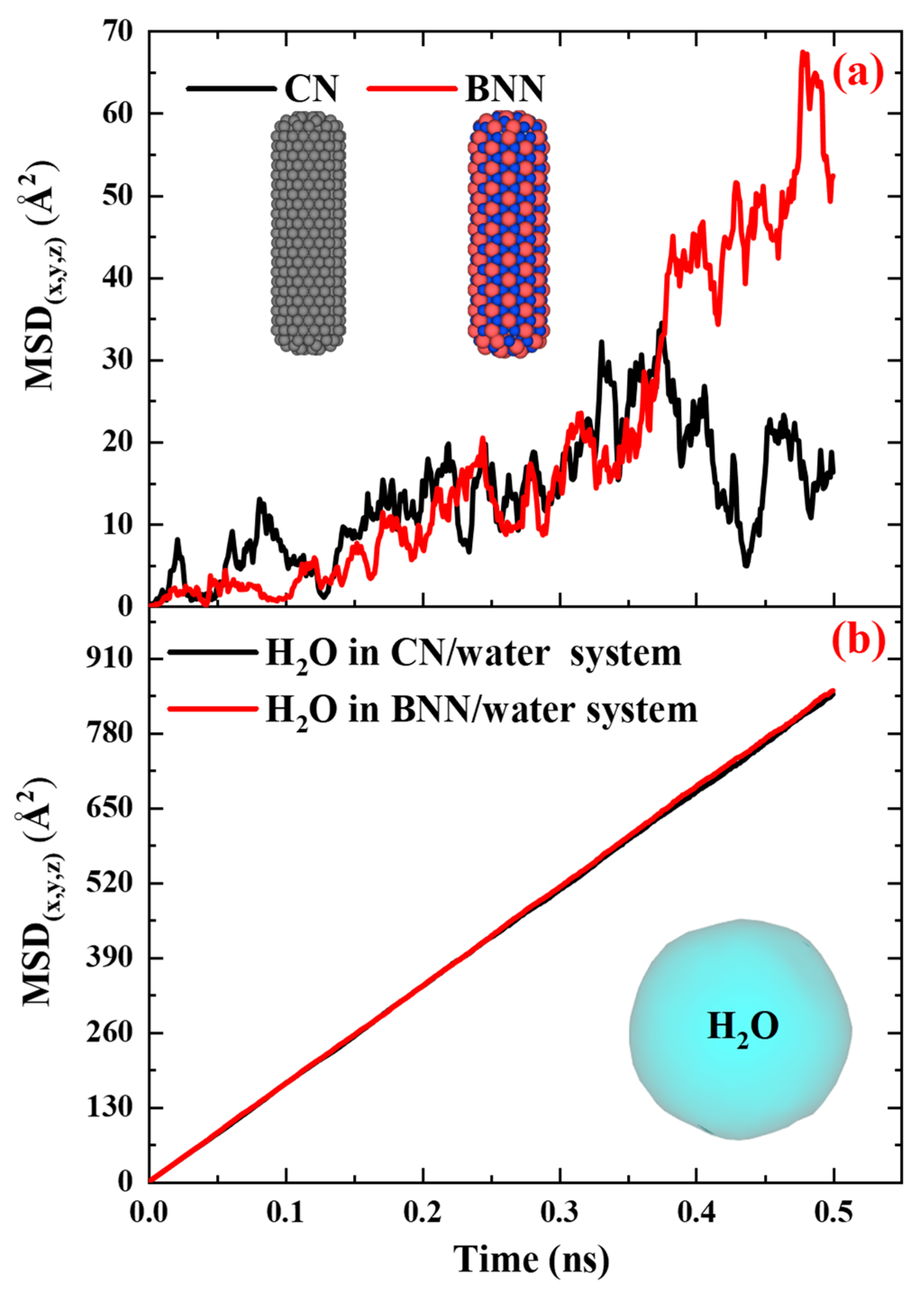

Figure 7 compares the MSD vs. time diagrams for CN and BNN, along with their surrounding water molecules, at 308 K and 1 atm pressure, to provide a clear comparison between these drug nanocarriers and their effects on water.

Figure 7.a reveals that the MSD of BNN increases gradually over time, while that of CN becomes nearly horizontal after 400 ps. This change in MSD indicates that BNN (0.11×10

-9 m

2.s

-1 m²/s) has higher mobility compared to CN (0.10×10

-9 m

2.s

-1 m²/s), resulting in a greater diffusion coefficient. This behavior can be attributed to the atomic interactions at the nanocapsule–water interface. In the CN–water interface, only carbon atoms interact with water, producing uniform repulsive and attractive forces. However, at the BNN–water interface, both boron and nitrogen atoms interact independently with water, generating a combination of distinct attractive and repulsive forces that enhance mobility and diffusivity. Further investigation into this phenomenon requires bond-order simulations, typically referred to as reactive simulations, which are discussed in the next section. In the case of H

2O (

Figure 7.b), the MSD over time in the presence of both BNN and CN exhibits an almost identical linear trend, indicating equivalent diffusion coefficients. These results demonstrate that neither BNN nor CN has a significant effect on the surrounding water.

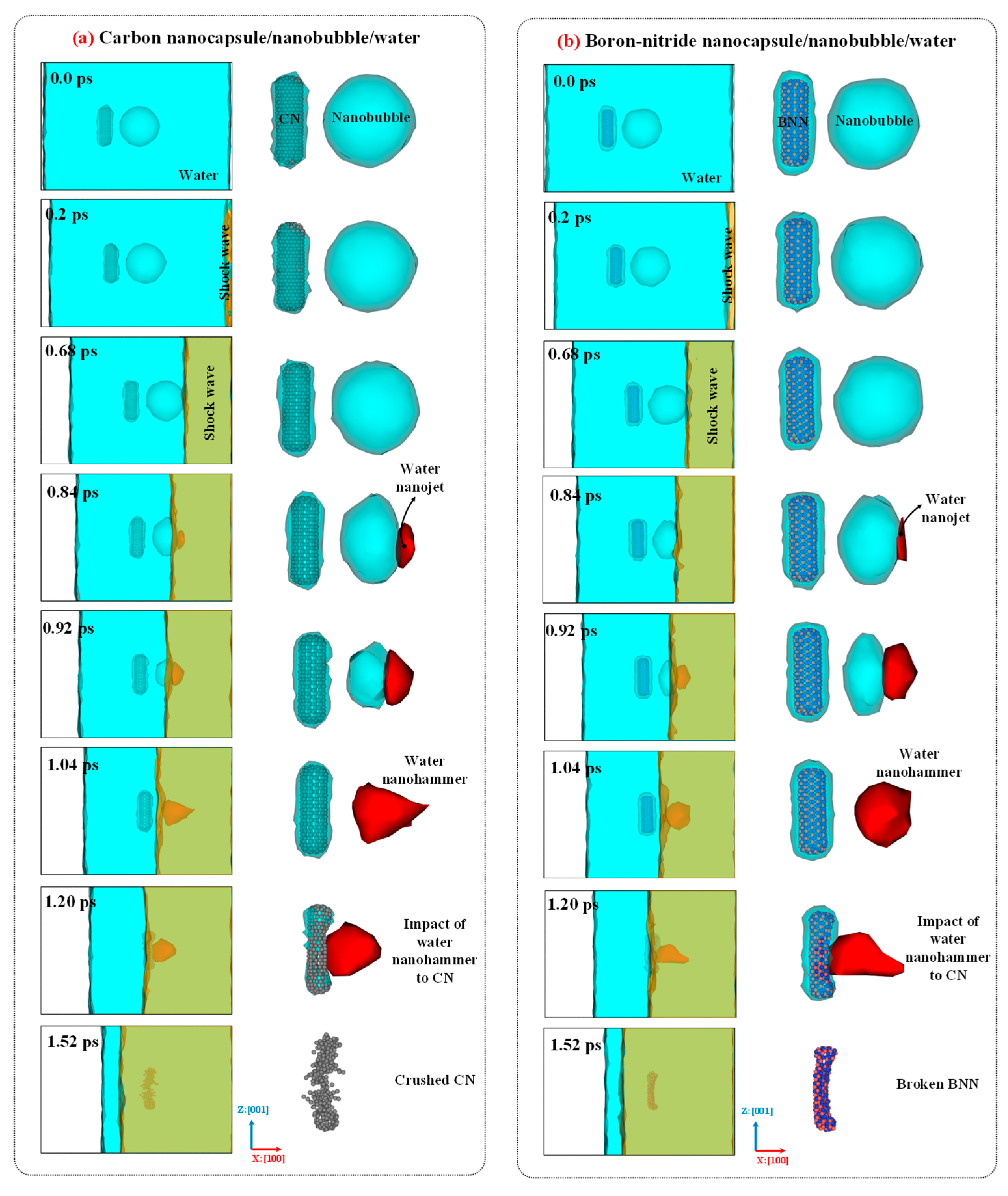

3.3. Nanobubble Cavitation as Releasing Agent

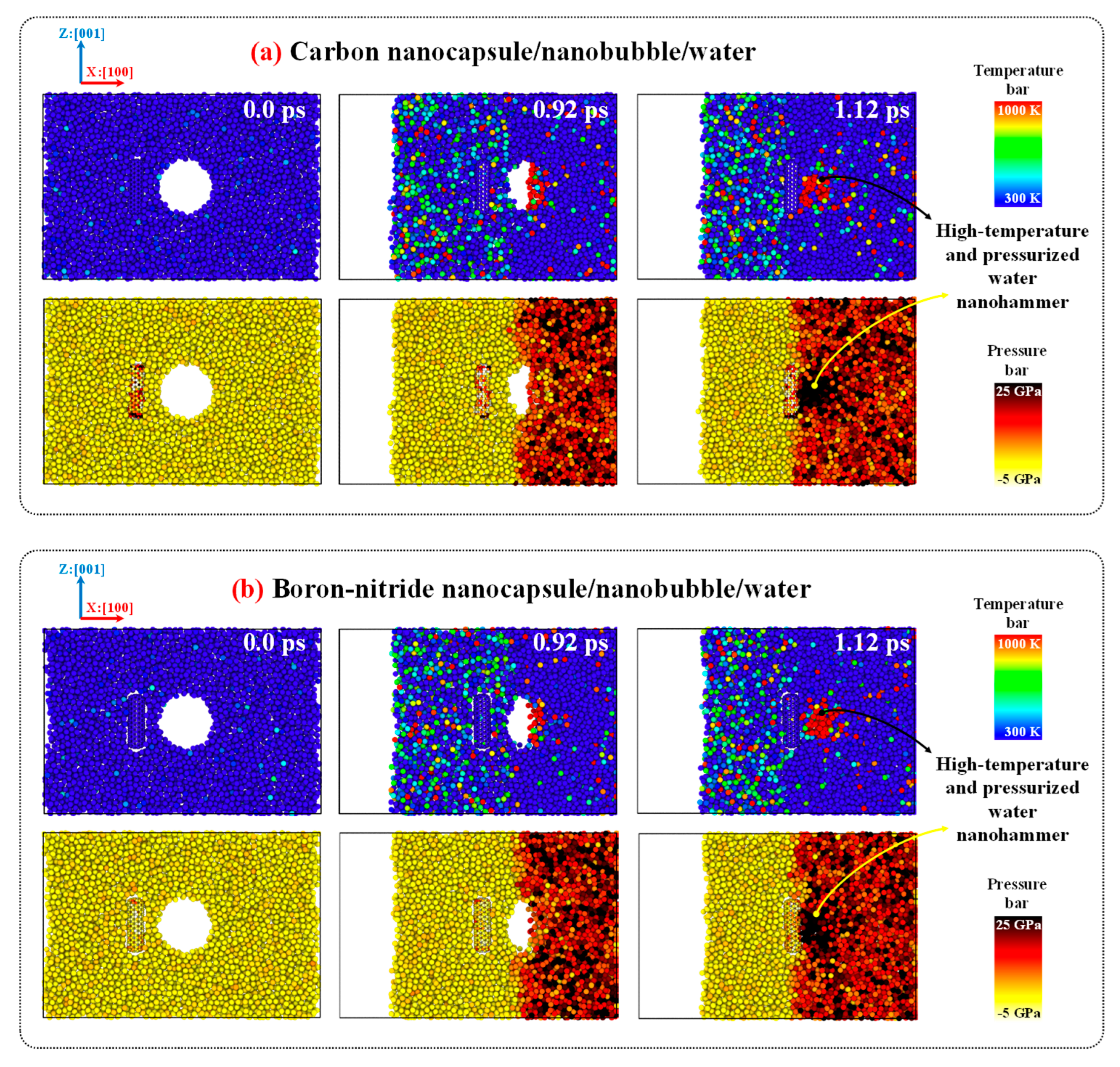

Figure 8 illustrates the collapse dynamics, formation of the water nanojet, emergence of the water nanohammer, collision of the nanohammer with the nanocapsules, and nanocapsule-induced damage caused by the nanohammer during nanobubble cavitation at 298 K and 1 atm. As shown in the figure, the movement of the entire system toward the mirror wall along the x:[100] direction leads to the collision of water molecules with mirror wall. As a result, the momentum of the water molecules is altered upon collision, and a planar shock wave forms and propagates along the x:[

00] direction. The orange mesh color in the figure illustrates this shock wave. Then, the shock wave moves upward and eventually reaches the upper wall of the nanobubble, where it collides with the interface of nanobubble-water. Upon this impact, the nanobubble begins to collapse, and its volume decreases as the pressure exerted by the shock wave exceeds the internal pressure of the nanobubble's wall.

As the nanobubble volume decreases (as evident in

Figure 8 between 0.68 and 1.04 ps), a water nanojet forms (highlighted by the red mesh in the figure) on the side where the nanobubble begins to collapse. This occurs because water molecules move rapidly into the vacated volume of the nanobubble, encountering little resistance, which leads to an increase in their velocity and the formation of a focused jet. The volume of the water nanojet gradually increases as the collapse proceeds. When the nanobubble entirely collapses at 1.04 ps, the nanojet reaches its maximum volume and is typically referred to as the "water nanohammer," as it is responsible for the final impact and damage. Ultimately, the water nanohammer strikes the nanocapsules, breaking them and thereby creating favorable conditions for the release of the drug.

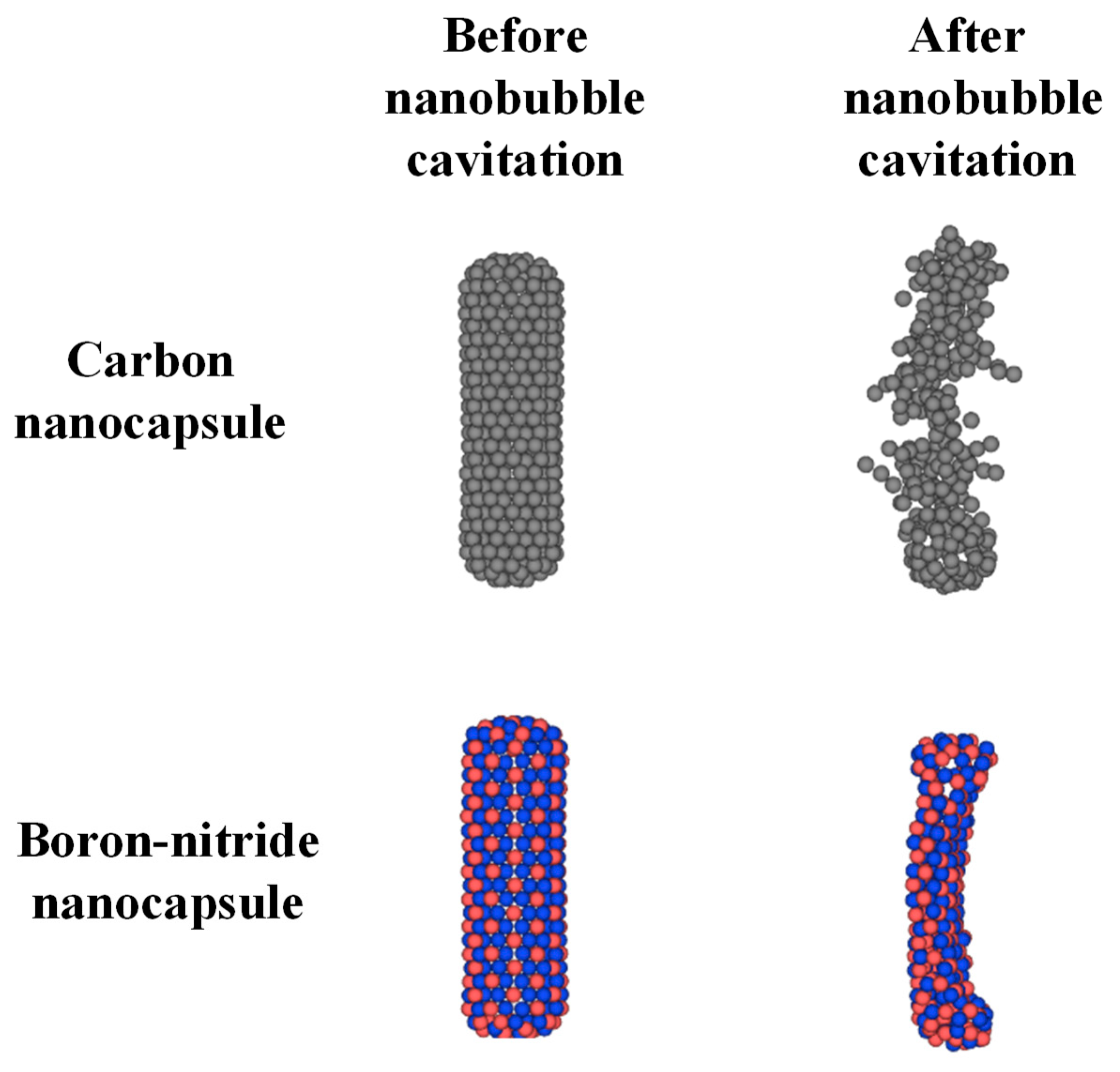

Comparing the time-evolved snapshots for the CN/nanobubble/water and BNN/nanobubble/water systems in

Figure 8 reveals that the nanobubble cavitation behavior in both cases is similar, and the type of nanocapsule material (CN or BNN) does not significantly affect the collapse dynamics. However, the damage induced by the water nanohammer differs markedly between the two systems. At the end of the nanobubble collapse, the water nanohammer forms and moves toward both CN and BNN with approximately equal volume and energy; nevertheless, it interacts with them differently. As shown in this figure, when the water nanohammer transfers all its energy to the nanocapsules at the final stage (1.52 ps), the CN nanocapsule is crushed, whereas the BNN nanocapsule is broken.

This outcome suggests that the water nanohammer collides with greater intensity with CN compared to BNN. The origin of this phenomenon can be attributed to the nature of atomic interactions between the water nanohammer and the constituent atoms of the nanocapsules. Carbon atoms in CN interact uniformly with water molecules at the leading edge of the nanohammer, whereas boron and nitrogen atoms in BNN exhibit different interaction behaviors. As a result, the momentum transfer from the water nanohammer is more focused in the CN system and more dispersed in the BNN system. Consequently, the CN is crushed, while the BNN is merely broken. The crushing of CN indicates that this system can facilitate efficient drug release under cavitation conditions. However, such crushing may also pose a risk of damaging the encapsulated anticancer drug. In contrast, the structural failure in BNN, characterized by wall breakage rather than crushing, may enable drug release with reduced risk of molecular damage.

To provide further evidence regarding the causes of crushing and breakage in CN and BNN, respectively,

Figure 9 compares the temperature and pressure profiles of the CN/nanobubble/water and BNN/nanobubble/water systems during cavitation. As shown in the figure, the pressurized shock wave initiates the collapse of the nanobubble. Once the collapse begins, the resulting water nanojet carries high-pressure and elevated-temperature reaching up to 25 GPa and 1000 K, respectively. At the end of the collapse, this high-energy nanojet transforms into the water nanohammer, which transfers its thermal energy and pressure to the nanocapsules upon impact, causing structural damage. In the CN system, due to the localized nature of the collision, the nanocapsule absorbs nearly all of the transferred energy and pressure, resulting in complete crushing. In contrast, the BNN system disperses a portion of the temperature and pressure upon impact, leading to breakage rather than total collapse.

3.4. Outlook and Perspective

The main findings indicate that BNN diffuses more than CN, and that neither nanocapsule significantly influences its surrounding medium. Additionally, temperature cannot be utilized as a navigation parameter for either system. Under nanobubble cavitation, CN undergoes crushing, while BNN experiences breakage.

Figure 10 compares the configurations of CN and BNN before and after cavitation-induced damage. The crushing and breaking of CN and BNN, respectively, provide favorable conditions for the release of the drug. However, the complete crushing of CN increases the possibility of damage to the encapsulated drug. It is now necessary to develop a strategy for navigating CN and BNN nanocapsules and to further investigate the drug release mechanisms from these nanocapsules, as well as the potential for drug damage under nanobubble cavitation.

To address navigation challenges, functional groups can be added to CN or BNN to activate them for chemical reactions and to render them responsive to external electric or magnetic fields. When functional groups containing metallic atoms such as iron or nickel are introduced, both of which respond to external electromagnetic fields, they enable the nanocapsules to alter their direction and move along a desired pathway under the influence of these fields. This mechanism facilitates controlled navigation and targeted delivery to cancerous tumors, thereby enhancing the overall performance of drug delivery.

To minimize drug degradation caused by collapse-induced shock, alternative release mechanisms, such as neutron radiation [

52,

53], may be employed. This approach can be efficient for BNN nanocapsules, due to the presence of B, which is capable of absorbing neutron radiation. Upon interaction with neutron-rays, B atoms can facilitate localized wall breakage, triggering drug release without damaging the drug itself, especially since the drug molecules do not contain B and therefore do not absorb neutron radiation. Furthermore, this method requires reactive MD simulations to confirm whether new chemical species are formed following wall breakage and drug release. These proposed strategies are promising for future applications in drug delivery systems utilizing CN and BNN nanocapsules.

4. Conclusions

The current study investigates the diffusion behavior of CN and BNN as drug carriers, as well as the effects of cavitation nanobubbles on them, to provide in-depth theoretical insight into drug delivery and release strategies using MD simulations. Investigation of the diffusion behavior of the CN/water system over the temperature range 298–308 K reveals that CN nanocarriers exhibit both translational and rotational degrees of freedom; as temperature increases, translational motion becomes dominant. A 3.3 % rise in temperature increases the diffusion coefficient of water by 31% (from 2.16×10-9 to 2.83×10-9 m2.s-1), while having no significant influence on CN (0.1×10-9 m2.s-1), indicating that temperature has a more substantial effect on water than on CN.

Examination of the diffusion characteristics of the BNN/water system reveals that, in all cases, BNN exhibits a similar behavior to CN; however, its diffusion coefficient (DBNN=0.1×10-9 m2.s-1) is approximately 1% higher than that of CN and remains independent of temperature. The differing diffusivity behaviors of CN and BNN can be attributed to variations in interaction forces at the CN-water and BNN-water interfaces, respectively. In the CN-water system, only carbon atoms interact with water, whereas in the BNN-water system, both boron and nitrogen atoms participate in interactions with water.

H2O also displays nearly identical behavior and diffusion coefficients in the presence of both BNN and CN. These results can be categorized into two types: positive and negative. Regarding the adverse outcomes, the findings suggest that temperature variations, such as those occurring in tissues near cancerous tumors, are unlikely to facilitate the targeted delivery of CN or BNN nanocarriers; thus, temperature alone is not an effective navigational cue for these drug delivery systems. On the positive side, these drug nanocarriers have no significant influence on their medium and can be used in drug delivery systems without altering the behavior of their surrounding environment.

Investigation of the effects of nanobubble cavitation on CN and BNN as drug releasing agents at 298 K and 1 atm reveals that these nanocapsules do not influence the dynamics of nanobubble behavior or collapse. However, the water nanohammer, formed following the collapse of nanobubbles and moving toward the nanocapsules at a temperature of approximately 1000 K and a pressure of 25 GPa, induces different types of damage. Under the impact of the water nanohammer, CN is crushed, while BNN undergoes breakage. This difference arises from the distinct interaction mechanisms at the nanohammer interface: C–water interactions in the CN/nanohammer system differ fundamentally from B–water and N–water interactions in the BNN/nanohammer system. The crushing of CN under cavitation facilitates efficient drug release; however, it may also increase the risk of damage to the encapsulated anticancer drug. In contrast, the wall breakage observed in BNN provides favorable conditions for drug release while potentially minimizing the risk of damage to the encapsulated therapeutic agents.

In summary, this study concludes that BNN exhibits better diffusion characteristics and offers more favorable conditions for drug release under nanobubble cavitation compared to CN. However, challenges related to navigation, targeted delivery to cancerous tumors, and the safe release of drugs without damaging the encapsulated drug remain to be addressed. To address these challenges, functional groups containing metallic atoms such as iron or nickel may be employed to enable navigation and tumor targeting under external electromagnetic fields. Additionally, neutron radiation may serve as an alternative mechanism for controlled drug release. These aspects require further investigation in future research on drug delivery systems to establish a comprehensive and safe framework for biomedical applications, particularly those intended for use in the human body.

References

- Chhikara, B.S.; Parang, K. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: the trends projection analysis. Chem. Biol. Lett. 2023, 10, 451. [Google Scholar]

- Gaidai, O.; Yan, P.; Xing, Y. Future world cancer death rate prediction. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakarla, A.B.; Kong, I. In Vitro and In Vivo Cytotoxicity of Boron Nitride Nanotubes: A Systematic Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaspour, M.; Namayandeh Jorabchi, M.; Akbarzadeh, H.; Salemi, S.; Ebrahimi, R. Molecular dynamics simulation of anticancer drug delivery from carbon nanotube using metal nanowires. J. Comput. Chem. 2019, 40, 2179–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Rasheed, T.; Nabeel, F.; Hayat, U.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Endogenous and exogenous stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems for programmed site-specific release. Molecules 2019, 24, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yang, F.; Xiong, F.; Gu, N. The smart drug delivery system and its clinical potential. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1306–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, N.; Leroux, J.C. The journey of a drug-carrier in the body: An anatomo-physiological perspective. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Jain, C.P. Advances in niosome as a drug carrier: A review. Asian J.pharmacy 2007, 1, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Lei, H.; Zhang, D. Recent progress in nanotechnology-based drug carriers for resveratrol delivery. Drug Deliv. 2023, 30, 2174206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, J. Therapeutic poly(amino acid)s as drug carriers for cancer therapy. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucillo, P. Drug carriers: Classification, administration, release profiles, and industrial approach. Processes 2021, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, Y.; Vadla, P.; Rodda, S.; Parimi, D.S.; Paila, B.; Dasari, V. V.; Suresh, A.K. Fundamentals of Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems. In Emergence of Sustainable Biomaterials in Tackling Inflammatory Diseases; Springer, 2025; pp. 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- Saripilli, R.; Sharma, D.K. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery system for the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilder, T.A.; Hill, J.M. Carbon nanotubes as drug delivery nanocapsules. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2008, 8, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C. Nanocapsules as drug delivery systems. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2005, 28, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.H.; Huang, E.; Lo, W.C.; Yeh, C.K. Ultrasound-cavitation-enhanced drug delivery via microbubble clustering induced by acoustic vortex tweezers. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 114, 107273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, J.L.; Mannaris, C.; Cabañas, M.V.; Carlisle, R.; Manzano, M.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Coussios, C.C. Ultrasound-mediated cavitation-enhanced extravasation of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for controlled-release drug delivery. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 340, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Shah, J.; Hein, S.; Misra, R.D.K. Controlled and extended drug release behavior of chitosan-based nanoparticle carrier. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Refaai, K.A.; AlSawaftah, N.A.; Abuwatfa, W.; Husseini, G.A. Drug Release via Ultrasound-Activated Nanocarriers for Cancer Treatment: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harish, V.; Kumar, A.; Babu, M.R.; Leo, A.; Srivastav, S. Acoustic Cavitation-Based Drug Delivery. In Transdermal Applications of Minimally Invasive Drug Delivery Systems: Current Trends and Future Perspectives; Springer, 2025; pp. 107–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, C.F.; Lin, C.W.; Yeh, C.K. Ultrasound-triggered drug release and cytotoxicity of microbubbles with diverse drug attributes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 112, 107182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizi, A.; Kalantar, Z.; Hashemianzadeh, S.M. Drug delivery by SiC nanotubes as nanocarriers for anti-cancer drugs: Investigation of drug encapsulation and system stability using molecular dynamics simulation. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, F.; Hashemianzadeh, S.M.; Bagheri, Y. Insight into the encapsulation of gemcitabine into boron- nitride nanotubes and gold cluster triggered release: A molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 278, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Shi, X.; Chen, X. Self-assembled nanocapsules in water: A molecular mechanistic study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 20377–20382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaghani, M.Z.; Yousefi, F.; Seidi, F.; Sajadi, S.M.; Rabiee, N.; Habibzadeh, S.; Esmaeili, A.; Mashhadzadeh, A.H.; Spitas, C.; Mostafavi, E.; et al. Dynamics of Antimicrobial Peptide Encapsulation in Carbon Nanotubes: The Role of Hydroxylation. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2022, 17, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdoğar, N.; Akkın, S.; Bilensoy, E. Nanocapsules for Drug Delivery: An Updated Review of the Last Decade. Recent Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2019, 12, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasim, S.A.; Al-Lami, M.S.; J, A.A.; Shather, A.H.; Aldhalmi, A.K.; Taki, A.G.; Ahmed, B.A.; Al-Hamdani, M.M.; Krishna Saraswat, S. Nanostructures of boron nitride: A promising nanocarrier for anti-cancer drug delivery. Micro and Nanostructures 2024, 185, 207708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavifar, A.; Raissi, H.; Akbari, A. DFT and MD investigations on the functionalized boron nitride nanotube as an effective drug delivery carrier for Carmustine anticancer drug. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.A.; Rady, A.S.S.M.; Sidhom, P.A.; Sayed, S.R.M.; Ibrahim, K.E.; Awad, A.M.; Shoeib, T.; Mohamed, L.A. A Comparative DFT Investigation of the Adsorption of Temozolomide Anticancer Drug over Beryllium Oxide and Boron Nitride Nanocarriers. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25203–25214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaghani, M.Z.; Bagheri, B.; Yousefi, F.; Nasiriasayesh, A.; Mashhadzadeh, A.H.; Zarrintaj, P.; Rabiee, N.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Fierro, V.; Celzard, A.; et al. Boron nitride nanotube as an antimicrobial peptide carrier: A theoretical insight. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Ur-Rehman, S.; Khalid, L.; Bhatti, I.A.; Bhatti, H.N.; Iqbal, J.; Bai, F.Q.; Zhang, H.X. Investigation of the adsorption properties of gemcitabine anticancer drug with metal-doped boron nitride fullerenes as a drug-delivery carrier: A DFT study. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 2873–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosta, S.; Hashemianzadeh, S.M.; Ketabi, S. Encapsulation of cisplatin as an anti-cancer drug into boron-nitride and carbon nanotubes: Molecular simulation and free energy calculation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 67, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M.; Guerriero, G.; Shakya, G.; Krattiger, L.A.; G. Paganella, L.; Narciso, M.L.; Supponen, O. Cyclic jetting enables microbubble-mediated drug delivery. Nat. Phys. 2025, 21, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wei, T.; Gu, L.; Yang, H.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y. Focal opening of the neuronal plasma membrane by shock-induced bubble collapse for drug delivery: a coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 29862–29869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavadlav, J.; Arampatzis, G.; Koumoutsakos, P. Bayesian selection for coarse-grained models of liquid water. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Bo, Z.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Shuai, X.; Yan, J.; Cen, K. Temperature dependence of ion diffusion coefficients in NaCl electrolyte confined within graphene nanochannels. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 7678–7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, S.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. Molecular Dynamics-Based Approach for Laser-Induced Cavitation Bubbles: Bridging Experimental and Hybrid Analytical–Computational Approaches. Langmuir 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, S.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. The role of sawtooth-shaped nano riblets on nanobubble dynamics and collapse-induced erosion near solid boundary. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 405, 124947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S.J.; Tutein, A.B.; Harrison, J.A. A reactive potential for hydrocarbons with intermolecular interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 6472–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.C.; Andzelm, J.; Robbins, M.O. AIREBO-M: A reactive model for hydrocarbons at extreme pressures. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Los, J.H.; Kroes, J.M.H.; Albe, K.; Gordillo, R.M.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Fasolino, A. Extended Tersoff potential for boron nitride: Energetics and elastic properties of pristine and defective h -BN. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 184108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, N. Nano-electro-mechanical conduct of boron nitride nanotube as piezoelectric nanogenerators and nanoswitches. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 25037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabay, M.; Jahanbin Sardroodi, J.; Rastkar Ebrahimzadeh, A. Adsorption and immobilisation of human insulin on graphene monoxide, silicon carbide and boron nitride nanosheets investigated by molecular dynamics simulation. Mol. Simul. 2017, 43, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO-the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 18, 15012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneva, I.I.; Cuzzo, B.; Fazili, T.; Javaid, W. Normal body temperature: A systematic review. In Proceedings of the Open Forum Infectious Diseases; Oxford University Press US, p. ofz032., 2019; Vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Protsiv, M.; Ley, C.; Lankester, J.; Hastie, T.; Parsonnet, J. Decreasing human body temperature in the United States since the industrial revolution. Elife 2020, 9, e49555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, X.; Dong, R.; Wang, H. The impact of low-velocity shock waves on the dynamic behaviour characteristics of nanobubbles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 11945–11957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, N.; Rezaee, S. Lithium-Doped Barium Titanate as Advanced Cells of ReRAMs Technology. J. Electron. Mater. 2023, 52, 1575–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, N.; Rezaee, S.; Azizi, B. Mechanical properties and role of 2D alkynyl carbon monolayers in the progress of lithium-air batteries. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, M.; Heil, S.R.; Sacco, A. Temperature-dependent self-diffusion coefficients of water and six selected molecular liquids for calibration in accurate 1H NMR PFG measurements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2000, 2, 4740–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ahn, Y.; Song, S.H.; Lee, D. Tungsten nanoparticle anchoring on boron nitride nanosheet-based polymer nanocomposites for complex radiation shielding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 221, 109353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerwein, W.A.G.; Wittig, A.; Moss, R.; Nakagawa, Y. Neutron capture therapy: Principles and applications; Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).