Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mass Rearing of Corcyra cephalonica

2.2. Mass Rearing of Coelophora inaequalis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

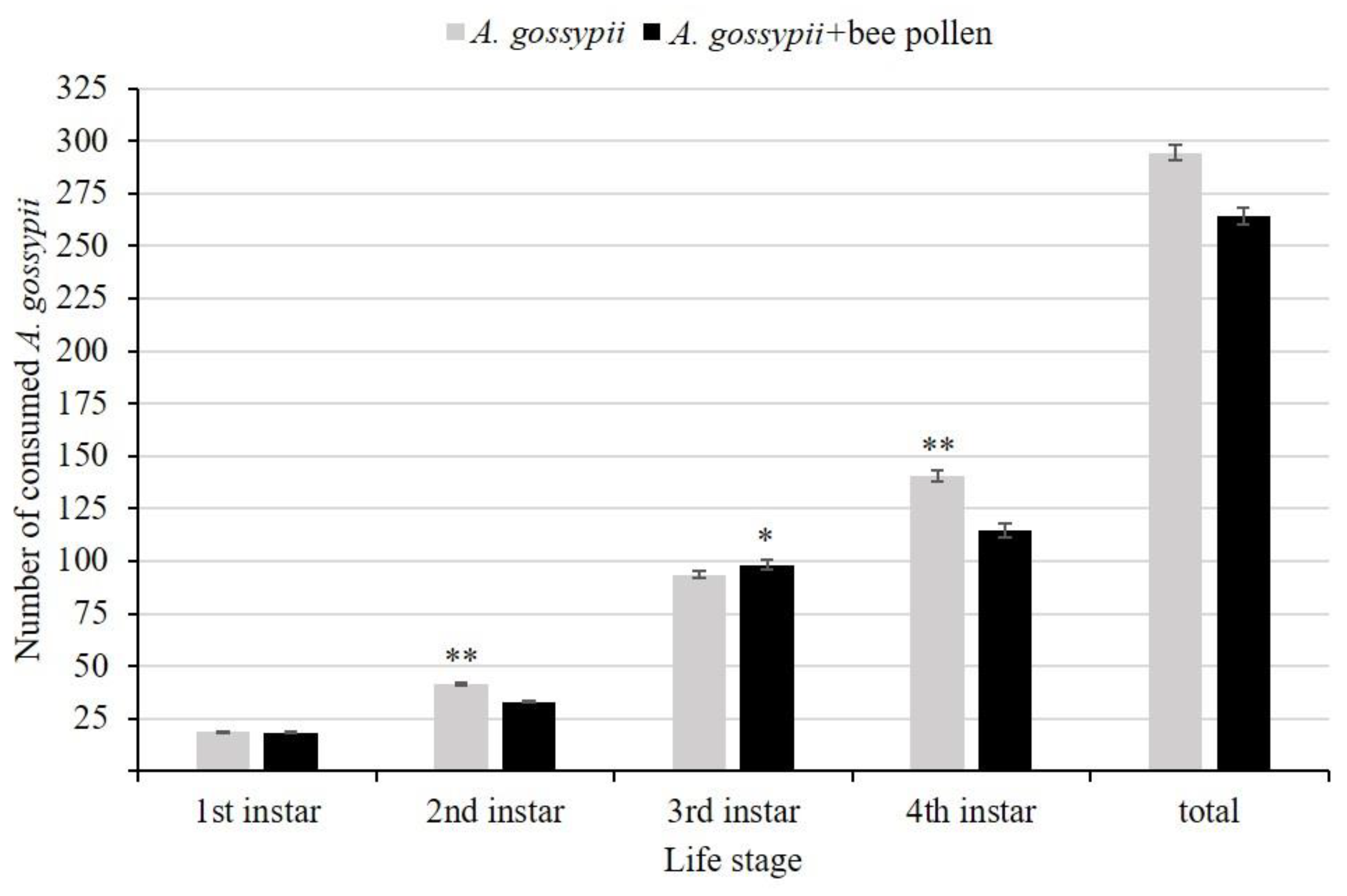

3.1. Effect of Prey and Alternative Food Sources on C. inaequalis Development and Reproduction

| Life stage | Development time (days, Mean±SE) | t-test | |

| A. gossypii | A. gossypii + bee pollen | ||

| 1st larva | 3.68±0.09 | 3.20±0.05 | t = -4.634, P<0.0001 |

| n | 60 | 60 | |

| 2nd larva | 2.87±0.11 | 2.67±0.09 | t = -1.289, P = 0.200 |

| n | 60 | 60 | |

| 3rd larva | 2.15±0.05 | 2.27±0.06 | t = 1.577, P = 0.118 |

| n | 60 | 60 | |

| 4th larva | 2.98±0.07 | 2.60±0.06 | t = -3.820, P<0.0001 |

| n | 60 | 60 | |

| pupa | 4.53±0.10 | 4.13±0.34 | t = -3.584, P = 0.001 |

| n | 57 | 52 | |

| Overall immature | 16.26±0.18 | 14.98±0.11 | t = 6.046, P<0.0001 |

| n | 57 | 52 | |

| Adult | 108.04±0.87 | 104.91±0.86 | t = 2.497, P=0.014 |

| n | 53 | 46 | |

| Male adult | 103.88±1.18 | 102.70±0.10 | t = 0.719, P = 0.476 |

| n | 25 | 20 | |

| Female adult | 111.75±0.76 | 106.62±1.24 | t = 3.560, P = 0.001 |

| n | 28 | 26 | |

3.2. Effect of Alternative Food Sources on Longevity of C. inaequalis Adult

| Prey | Longevity (day) | |

| male | female | |

| Bee pollen | 8.88±0.27a | 9.38±0.27a |

| Rice moth egg | 4.45±0.16b | 4.05±0.12b |

| Rice moth egg + bee pollen | 8.84±0.26a | 9.34±0.23a |

| F-test | F2,177 = 237.392, P < 0.0001 | F2,177 = 448.443, P < 0.0001 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pemberton, R.W.; Vandenberg, N.J. Extrafloral nectar feeding by ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 1993, 95, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, R.L.; Burkness, E.C.; Wold Burkness, S.J.; Hutchinson, W.D. Phytophagous preferences of the multicolored Asian ladybeetle (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) from autumn-riping fruit. J. Econ. Entomol. 2004, 97, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, S.E.; Harwood, J.D.; Obrycki, J.J. Larval feeding on Bt hybrid and non-Btcorn seedlings by Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) and Coleomegilla maculata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Environ. Entomol. 2008, 37, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lundgren, J.G. Nutritional aspects of non-prey foods in the life histories of predaceous Coccinellidae. Biol. Control. 2009, 51, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrouse, O.M.; Oran, O.M.; AL-Abbadi, S.Y. Chemical analysis and identification of pollen grains from different Jordanian honey samples. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2004, 39, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, J.G.; Wiedenmann, R.N. Nutritional suitability of field corn pollen as food for the predator, Coleomegilla magulata and Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) during anthesis in an Illinois cornfield. Environ. Entomol. 2004, 33, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, P.; Bonte, M.; Vanspebroeck, K.; Bolckmans, K.; Deforce, K. Development and reproduction of Adalia bipunctata (Coleoptera Coccinellidae) on eggs of Ephestia kuehniella (Lepidoptera: Phycitidae) and pollen. Pest Manag. Sci. 2005, 61, 1129–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omkar. Suitability of different foods for a generalist ladybird, Micraspis discolor (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2006, 26, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triltsch, H. Food remains in the guts of Coccinella septempunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) adults and larvae. Eur. J. Entomol. 1999, 96, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hemptinne, J.L.; Desprets, A. Pollen as a spring food for Adalia bipunctata. In Ecology of Aphidophaga; Hodek, I., Ed.; Academia, Prague and Dr. W. Junk, Dordrecht, 1986; pp. 29–35.

- Berkvens, N.; Bonte, J.; Berkvens, D.; Deforce, K.; Tirry, L.; Clercq, P.D. Pollen as an alternative food for Harmonia axyridis. BioControl. 2008, 53, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.-L.; Wang, X.-F.; Feng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ji, F.; Cui, W.-X.; Qiao, B.-M. 2024. Effect of pollen consumption on development and intraguild predation of two predatory coccinellidae. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.S.; Pontes, W.J.T.; Nobrega, R.L. Pollen did not provide suitable nutrients for ovary development in a ladybird Brumoides foudraii (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Diversitas J. 2020, 5, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, T.M. Rice moth, Corcyra cephalonica (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae) – A boon for biocontrol as a factitious host for mass production of parasitoids and predators. J. Biol. Control, 2023, 37, 01–05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Peng, J.; Liang, J.F.; Huang, C.; Xie, Y.-H.; Wang, X. Changes in life history parameters and transcriptome profile of Serangium japonicum associated with feeding on natural prey (Bemisia tabaci) and alternate host (Corcyra cephalonica eggs). BMC Genomics. 2023, 24, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorani, J. Coelophora inaequalis. In An illustrated guide to lady beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) of the Indian Subcontinent. Part 1. Tribe Coccinellini, pp. 1–307 in Zootaxa (Vol. 5332, Number 1, pp. 106–107). Zenodo. 2023.

- Peck, S.; Thomas, M. A distributional checklist of the beetles (Coleoptera) of Florida. Arthropods of Florida and Neighboring Land Areas. Volume 16. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Gainesville. 1998, 180 pp.

- Mora, J.G.; Gapud, V.P.; Velasco, L.R.I. Life history and voracity of Coelophora inaequalis (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on Aphis craccivora Koch (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Philippine-Entomologist (Philippines). 1995, 9, 523–553. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, J.P. On the assessment of prey suitability in aphidophagous coccinellidae. European J. Entomol. 2005, 102, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.L.; Yao, F.L.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, X.S.; He, Y.X. Effect of two alternative prey species on development and fecundity of Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Chin. J. Biol. Cont. 2019, 35, 855–860. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, J.P. Development and reproduction of lady beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on the citrus aphids Aphis spiraecola Patch and Toxoptera citricida (Kirkaldy) (Homoptera: Aphididae). Biol. Control. 2000, 18, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sigsgaard, L. A floral diet increases the longevity of the coccinellid Adalia bipunctata but does not allow molting or reproduction. Front. Ecol. Evo. 2019, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagraves, M.P. Lady beetle oviposition behavior in response to the trophic environment. Biol. Control. 2009, 51, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodek, I.; Honek, A. Ecology of Coccinellidae. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht. 1996. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).