1. Introduction

As climate change and sustainability challenges intensify globally, the demand for professionals equipped with ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) competencies and practical capabilities has grown rapidly across industry, government, and academia [

1,

2]. Aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Taiwan’s “2050 Net-Zero Emissions” roadmap, higher education now plays a critical role in cultivating students’ sustainability literacy and interdisciplinary problem-solving skills [

3,

4].

In response to this need, the present study designed and implemented a general education course entitled “ESG: Organizational Greenhouse Gas Inventory, Decarbonization, and Net-Zero Transition.” The course aims to enhance students’ awareness of climate risks and organizational sustainability responsibilities while fostering their ability to apply sustainability strategies in real-world contexts [

5,

6]. The curriculum was developed based on SDG principles and ESG, with a focus on enabling students to construct a comprehensive view of sustainable development—from individual behaviors to corporate practices and broader societal frameworks [

7].

To achieve these goals, the course employed Problem-Based Learning (PBL) and discussion-based pedagogy, engaging students in midterm and final projects rooted in real or simulated ESG scenarios [

8]. Key instructional themes included ESG frameworks, GHG accounting methodologies, net-zero strategies, and international regulatory standards (e.g., ISO guidelines, Taiwan EPA definitions, CDP, SBTi, CBAM), thereby equipping students with both conceptual understanding and practical tools for sustainability transition.

Previous teaching experiences have revealed that while students generally possess sound digital literacy, they often require further development in core competencies such as communication, collaboration, and problem-solving. Our previous teaching project, which integrated digital learning and hands-on tasks in a materials science course, found that contextualized, experiential learning significantly improved student outcomes in innovation and analytical thinking. Building on this foundation, the present course incorporated ESG-centered topics with a more challenging and interdisciplinary task design [

9].

To evaluate the course’s educational impact, this study employed the UCAN Common Competency Survey a national instrument promoted by the Ministry of Education Republic of China, administered both before and after the course. The six assessed dimensions included: communication, continued learning, interpersonal interaction, problem-solving, innovation, and information technology application. Quantitative analysis was conducted to determine whether the course significantly enhanced student competencies, and to inform future curriculum refinement [

10,

11,

12].

Accordingly, the study addresses two main research questions:

(1) Does the course effectively enhance students’ competencies across the six UCAN domains?

(2) Can a curriculum integrating ESG topics, PBL pedagogy, and practice-based assignments foster students’ interdisciplinary sustainability capabilities?

This research seeks to develop a transferable instructional model for general education, offering empirical evidence to support the design of ESG-related courses in higher education. By embedding complex sustainability issues within practice-driven, student-centered learning environments, the study contributes to the advancement of competence-based sustainability education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background

In recent years, with the promotion of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in higher education, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has evolved beyond mere knowledge transmission, emphasizing instead students’ participation in action, reflection, and social practice. Corresponding to this pedagogical shift, traditional lecture-based teaching has gradually been replaced by student-centered approaches such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL), Challenge-Based Learning (CBL), and the Flipped Classroom.

For instance, integrating local issues into STEAM curricula using PBL strategies has been shown to significantly enhance students’ sense of place and environmental literacy, particularly in relation to SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities [

13]. In the field of engineering education, PBL has further evolved into Practice-Based Education (PBE) to meet the industry’s demand for students with practical and decision-making competencies. While PBL focuses on problem-solving processes, a lack of hands-on experience may limit its effectiveness in engineering practice. Therefore, PBE emphasizes scenario-based and task-integrated learning to equip students with the ability to analyze problems from multiple perspectives and develop appropriate solutions. Studies further indicate that ethical responsibility and cross-cultural communication are also essential competencies to be cultivated through ESD [

14].

CBL takes this further by challenging students with open-ended problems that lack predefined solutions, requiring them to work collaboratively and synthesize diverse information to propose creative and feasible strategies. When CBL is integrated with the flipped classroom model in engineering courses, students acquire foundational knowledge through digital resources before class and engage in thematic problem discussions during class. Such integration has been found to strengthen students’ systems thinking and action competence on topics like the circular economy [

15], while also enhancing student engagement and motivation [

16].

The flipped classroom, widely applied in recent years, emphasizes pre-class knowledge acquisition and in-class interactive learning. In ESD, it is often combined with PBL or CBL, allowing for “preparation before class and hands-on activities during class.” Students involved in flipped and challenge-based courses tend to show greater initiative and deeper understanding of sustainability topics such as circular economy, suggesting that the flipped classroom facilitates knowledge internalization and learning transfer [

17].

ESD emphasizes not only knowledge acquisition but also the cultivation of diverse competencies including action competence, systems thinking, ethical reasoning, and communication and collaboration skills. Literature has shown that ESD can significantly enhance students’ motivation and confidence to engage in social and environmental issues, shifting their learning from cognition to action and cultivating responsible, civic-minded learners [

18]. Some studies have noted gender and disciplinary differences in the development of action competence after ESD instruction, underscoring the importance of inclusivity and diversity in curriculum design [

19].

Regarding ethics and social responsibility, studies suggest that current curricula still lack sufficient emphasis on macro-ethical practices. Through cross-cultural comparisons and teacher perspectives, researchers advocate for the integration of sustainability themes with ethical deliberation, supported by simulation and discussion-based pedagogies to enhance students’ critical thinking and moral sensitivity [

20].

Effective ESD also relies on collaboration and interdisciplinary communication. Teaching strategies such as cooperative learning, group projects, and reflective journaling have been shown to improve students’ teamwork and coordination skills while fostering a stronger willingness to engage in sustainability challenges. Such courses typically incorporate real-world issues and community resources to help students develop interdisciplinary integration capabilities [

21].

Given the complexity and interdisciplinary nature of sustainability—spanning environmental, ecological, economic, social, technological, and ethical dimensions—higher education curricula must integrate diverse knowledge areas and practical contexts. Studies have repeatedly emphasized that interdisciplinary collaboration and practice-based teaching have become mainstream trends in ESD, serving as key mechanisms for developing the comprehensive competencies needed to meet future societal challenges.

The European Project Semester (EPS), an innovative ESD teaching model, exemplifies this approach. Implemented through cross-national university partnerships, students work in multinational teams to complete project designs aligned with the SDGs. By engaging in long-term, real-world projects, students cultivate collaboration, project management, and social responsibility skills. This model effectively expands their global perspectives and problem-solving pathways [

22].

At the institutional and curricular level, surveys on faculty engagement with ESD reveal that while interdisciplinary teaching is highly valued, its implementation faces challenges such as varying faculty backgrounds, coordination difficulties, and insufficient institutional support. It is therefore recommended that institutions establish support systems and resource platforms to facilitate cross-departmental and cross-disciplinary collaboration and integrate sustainability into academic program planning [

23].

Technological advancement has also transformed interdisciplinary learning environments. Tools such as virtual reality, open educational resources, and hybrid learning models have brought unprecedented flexibility and interactivity to ESD. These tools reshape classroom dynamics and expand students’ exposure to real-world issues and international case studies. In particular, they enable meaningful connections between local contexts and global challenges, providing students with more comprehensive problem understanding and reflective capacity [

24].

Furthermore, systematic literature reviews suggest that higher education institutions should embed sustainability literacy into curriculum design, integrating theme-based and bilingual teaching strategies to strengthen students’ intercultural understanding and global citizenship. The studies emphasize that interdisciplinary co-teaching will be a critical pathway for the future development of ESD [

25].

In summary, ESD has transitioned from traditional knowledge dissemination toward the development of students’ practical engagement, action-oriented learning, and interdisciplinary integration capabilities. Blending diverse teaching strategies—including PBL, CBL, and flipped classrooms—can enhance students’ systems thinking, ethical judgment, learning motivation, and practical ability. Real-world tasks and authentic scenarios further facilitate the application of knowledge to social and industrial problems. Interdisciplinary teaching not only helps students grasp the multifaceted nature of sustainability issues but also fosters collaboration, problem integration, and global perspective. Overall, effectively integrating diverse pedagogies with hands-on learning in ESD can promote students’ core competence development and lay a solid foundation for future challenges in environmental and social domains.

2.2. Materials

The instructional setting of this study is a general education course titled “ESG Organization’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory, Decarbonization, and Net-Zero Curriculum.” The course is grounded in the core principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), integrating Problem-Based Learning (PBL) and University Social Responsibility (USR) practices. It aims to cultivate students’ sustainability literacy and practical competencies in addressing climate change and achieving net-zero emissions.

2.2.1. Course Design

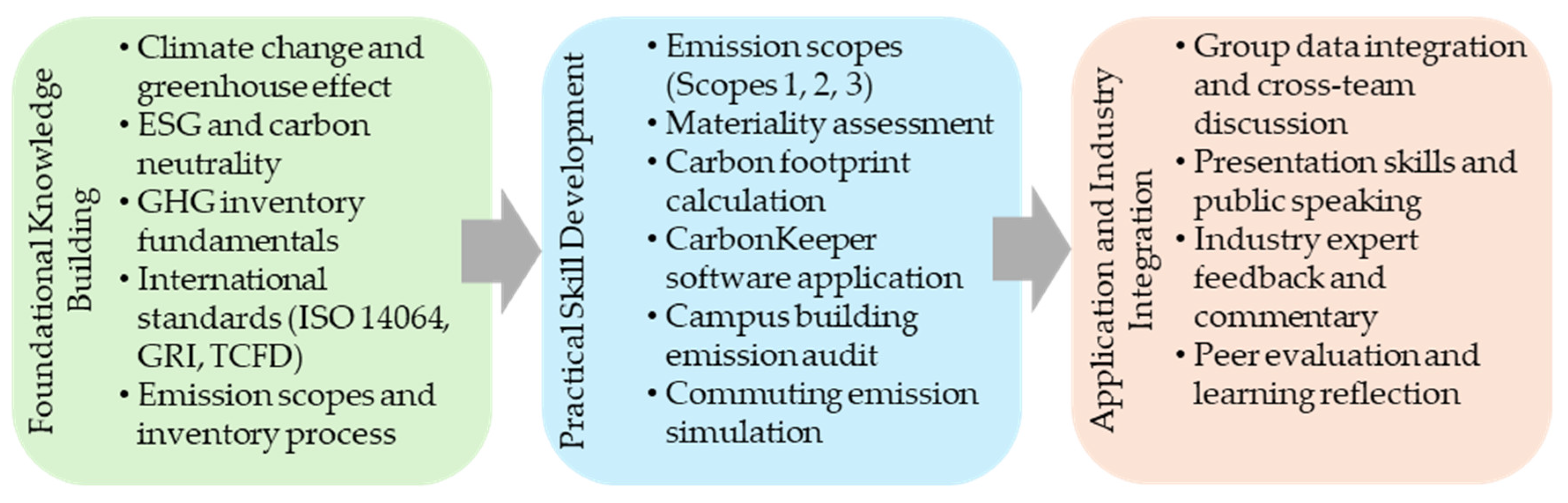

The course is divided into three main phases. The first phase, Foundational Knowledge Building, concentrates on helping students understand key concepts like climate change, the greenhouse effect, and carbon neutrality, while highlighting the importance of greenhouse gas (GHG) inventories and relevant international standards (e.g., ISO 14064). Through a mix of lectures and guided class discussions, the instructor assists students in developing a foundational knowledge framework in sustainability, which forms the theoretical basis for later practical work.

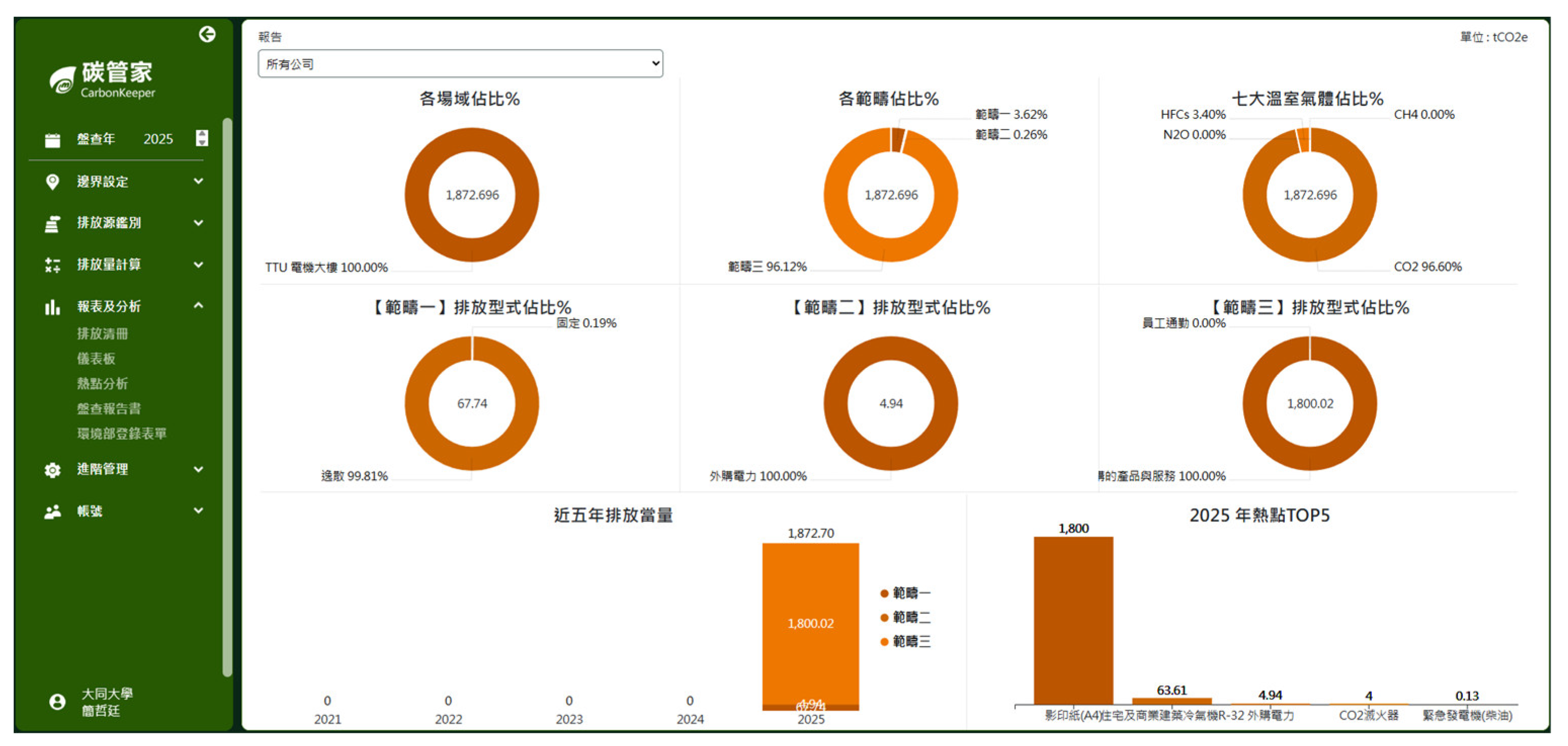

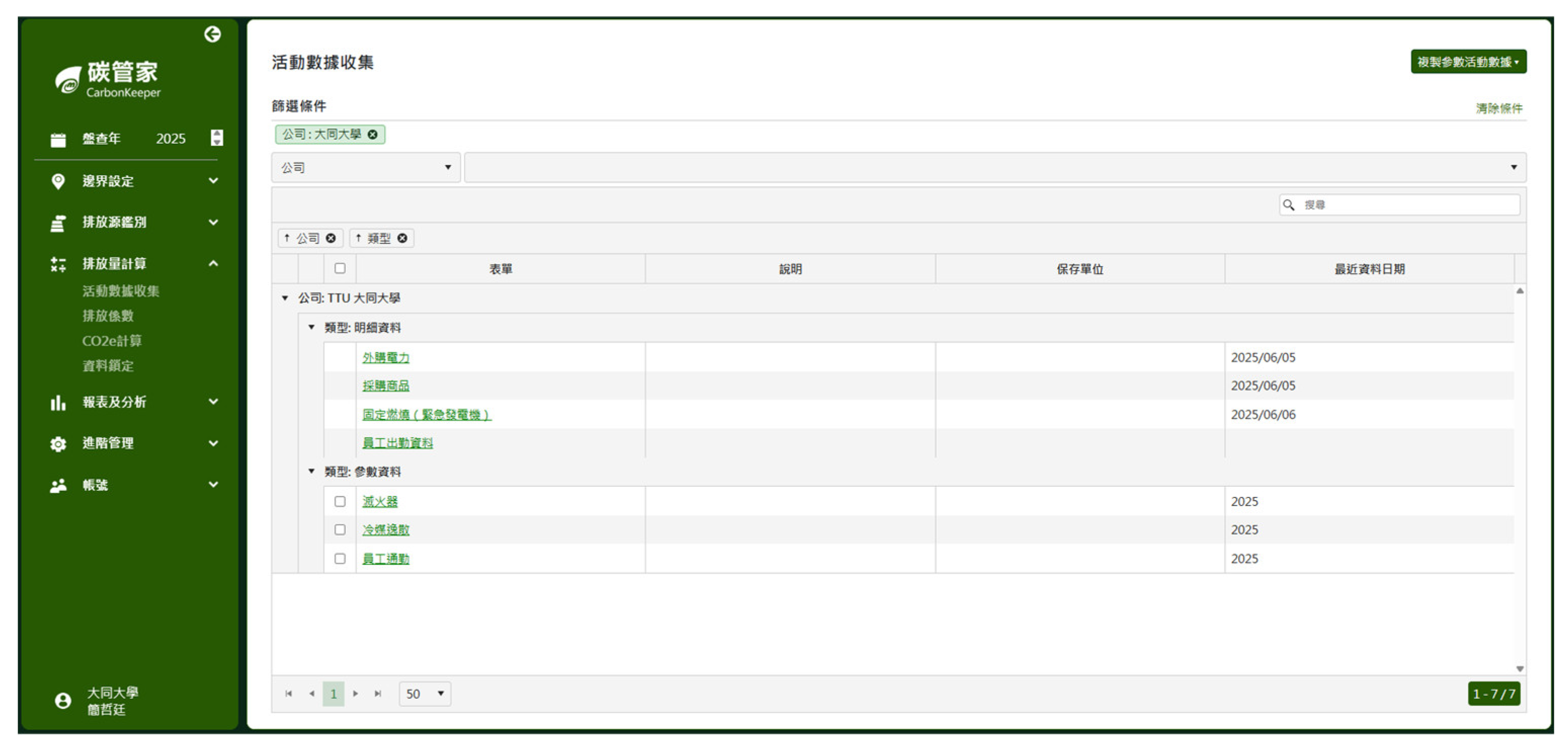

The second phase centers on Practical Skill Development. Students explore the three emission scopes (Scopes 1, 2, and 3), conduct materiality assessments, calculate carbon footprints, and plan emission reduction strategies. The curriculum includes simulation exercises such as campus building emission audits and commuting emission modeling. Students also learn how to use the CarbonKeeper software, as shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, and basic reporting techniques, enabling them to perform simplified GHG inventories and suggest practical improvement strategies.

The third phase focuses on Application and Industry Integration. Students compile group data and present their project findings through collaboration across teams. Industry lecturers are invited to provide feedback and share real-world insights into carbon management practices. Students must complete a final group report, document their data, and develop an evidence-based action proposal. Peer evaluations and reflective activities are included to enhance learning. Throughout all phases, task-based learning is the main teaching approach, reinforced by interdisciplinary content and multi-level feedback. This strategy encourages students to “learn by doing” and equips them with the skills needed to tackle complex sustainability issues.

Each phase included targeted topics and learning activities designed to guide students from conceptual understanding to applied learning in the context of ESG and carbon management, as shown in

Figure 4.

2.2.2. Lectures and Company Visits

As part of the course design to enhance students’ practical understanding of ESG and carbon neutrality, a series of four industry expert lectures and one corporate site visit were organized. These activities aimed to bridge theoretical knowledge with real-world applications, enabling students to construct a more comprehensive framework of sustainability practice. The guest lectures covered topics such as carbon inventory systems, international sustainability disclosure standards, carbon reduction mechanisms, and interdisciplinary practices—each session strategically building upon the last to deepen students’ conceptual and applied understanding.

The first lecture was delivered by Deputy General Manager Mr. Chang of M-Power Information Co., Ltd., titled “Why Conduct Carbon Inventory?”. This session provided an overview of global ESG development trends and emphasized the necessity of implementing corporate carbon inventory systems. It also addressed the implications of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and introduced practical case studies on the integration of digital carbon management platforms in industry, as shown in

Figure 5.

Subsequently, a lecture entitled “Value-Added Applications of Carbon Inventory and Practical Sustainability Reporting” was presented by a certified public accountant from a professional accounting firm. This lecture guided students through the ISO 14064 framework and its operational procedures, while also demonstrating how international sustainability disclosure frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) are incorporated into business practices, as shown in

Figure 6.

To further deepen students’ understanding of carbon reduction project frameworks, a guest lecture titled “ISO 14064-2 Project-Based Carbon Reduction Methods and Taiwan’s Voluntary Emission Reduction Mechanism” was delivered by a specialist from Lin Yuan Property Management Co., Ltd. The session provided a comprehensive overview of Taiwan’s voluntary carbon reduction schemes, the MRV (Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification) system, and additionality assessment procedures, enabling students to develop a systematic understanding of the policy rationale and institutional design behind carbon reduction strategies, as shown in

Figure 7.

The final guest lecture, “Why Carbon Inventory Matters,” was presented by a consultant specializing in environmental and carbon management from ATAX Accounting Firm. Drawing from extensive field experience, the speaker shared practical insights into the challenges and observations of conducting carbon inventories across various industries and organizations. Emphasis was placed on the interdisciplinary nature of carbon inventory work, which requires collaboration among financial, operational, technical, and environmental domains. This lecture further reinforced students’ understanding of the comprehensive skillsets needed to advance ESG practices in real-world contexts, as shown in

Figure 8.

In addition to the guest lectures, the course also included a site visit to the Formosa Plastics Group Museum. Through guided tours and on-site observations, students gained firsthand insights into how corporations implement ESG and CSR strategies in practice. Key topics included the integration of green manufacturing processes, energy-saving and carbon reduction initiatives, and corporate approaches to social engagement. This experiential learning activity effectively complemented the classroom-based instruction and encouraged students to critically reflect on the strategic planning and practical implications of sustainability from a corporate perspective, as shown in

Figure 9.

2.2.3. Practical Task

To deepen students’ understanding and application of sustainability issues, this course is designed with two practical tasks focusing on transportation carbon emissions and energy usage in campus buildings. Through scenario simulations and field data collection, students were guided to implement carbon inventory techniques, thereby cultivating their systems thinking and interdisciplinary analytical skills.

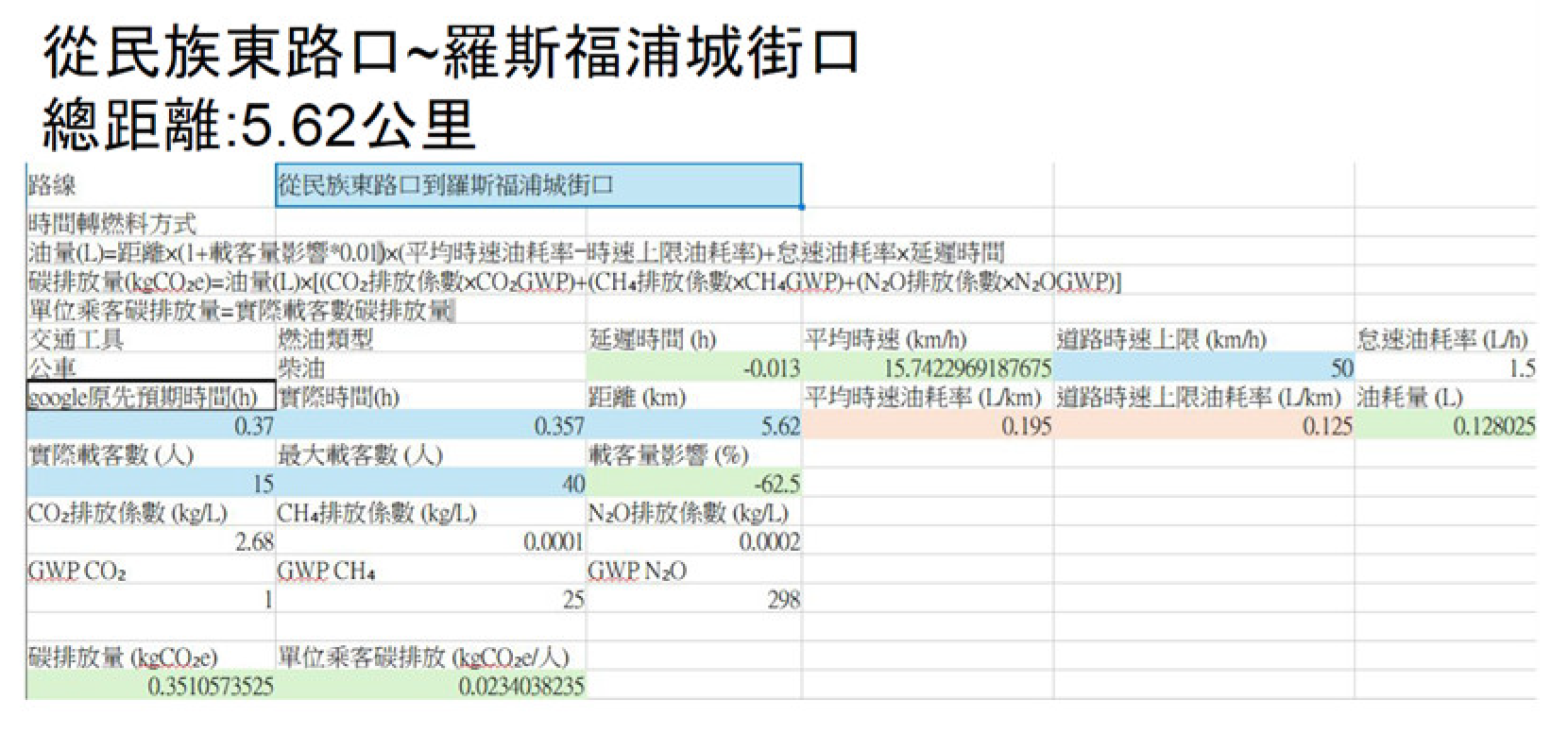

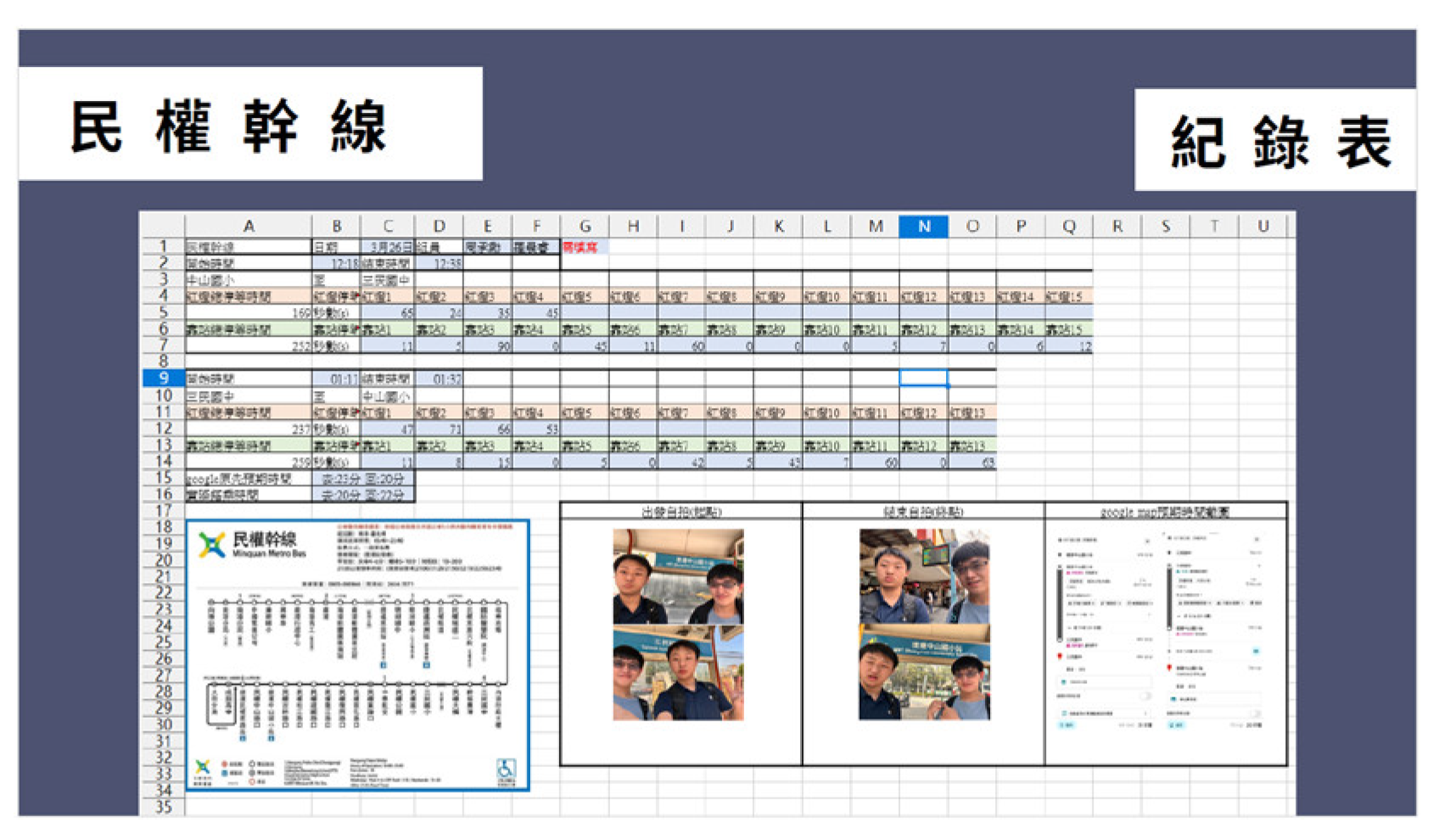

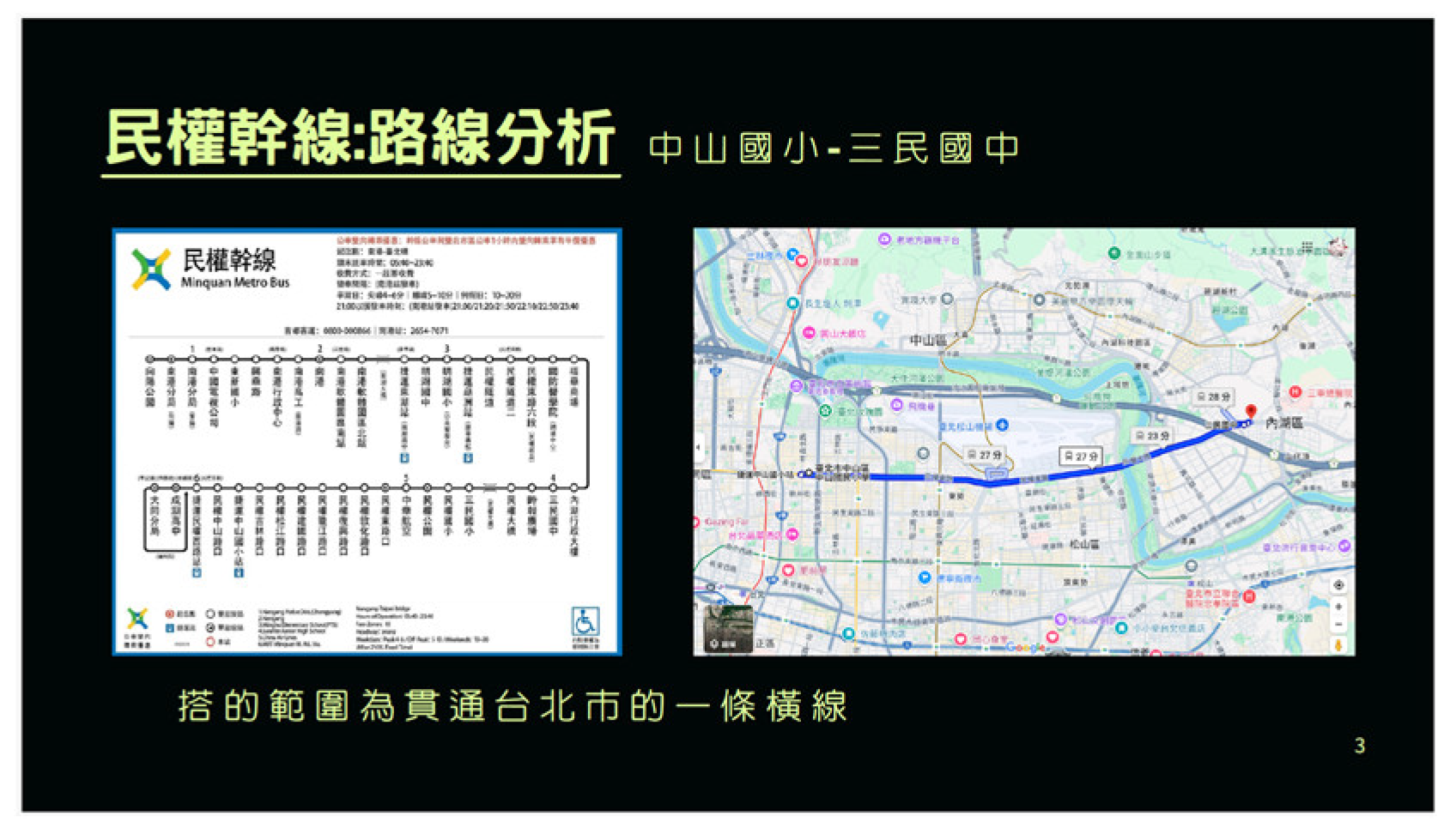

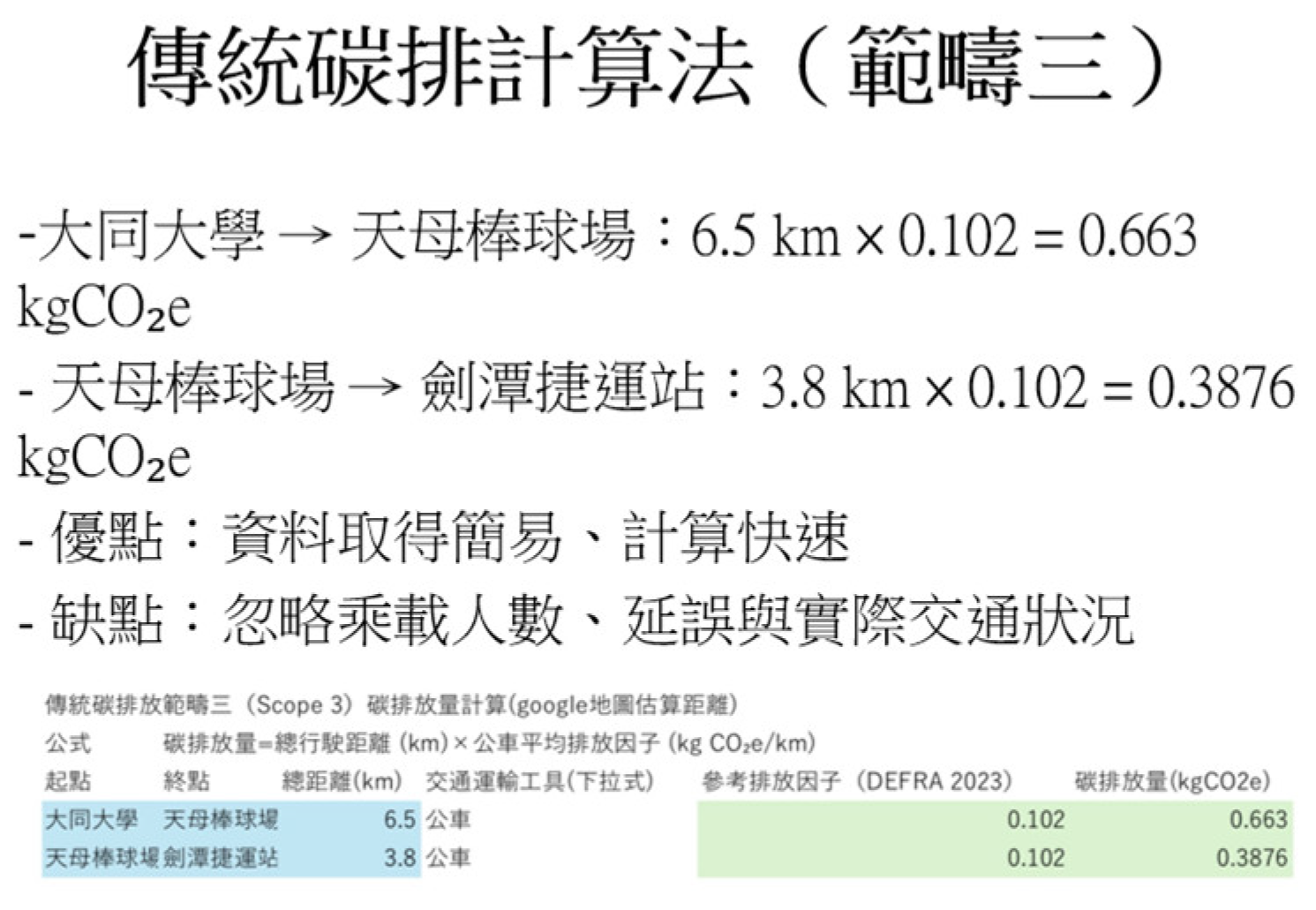

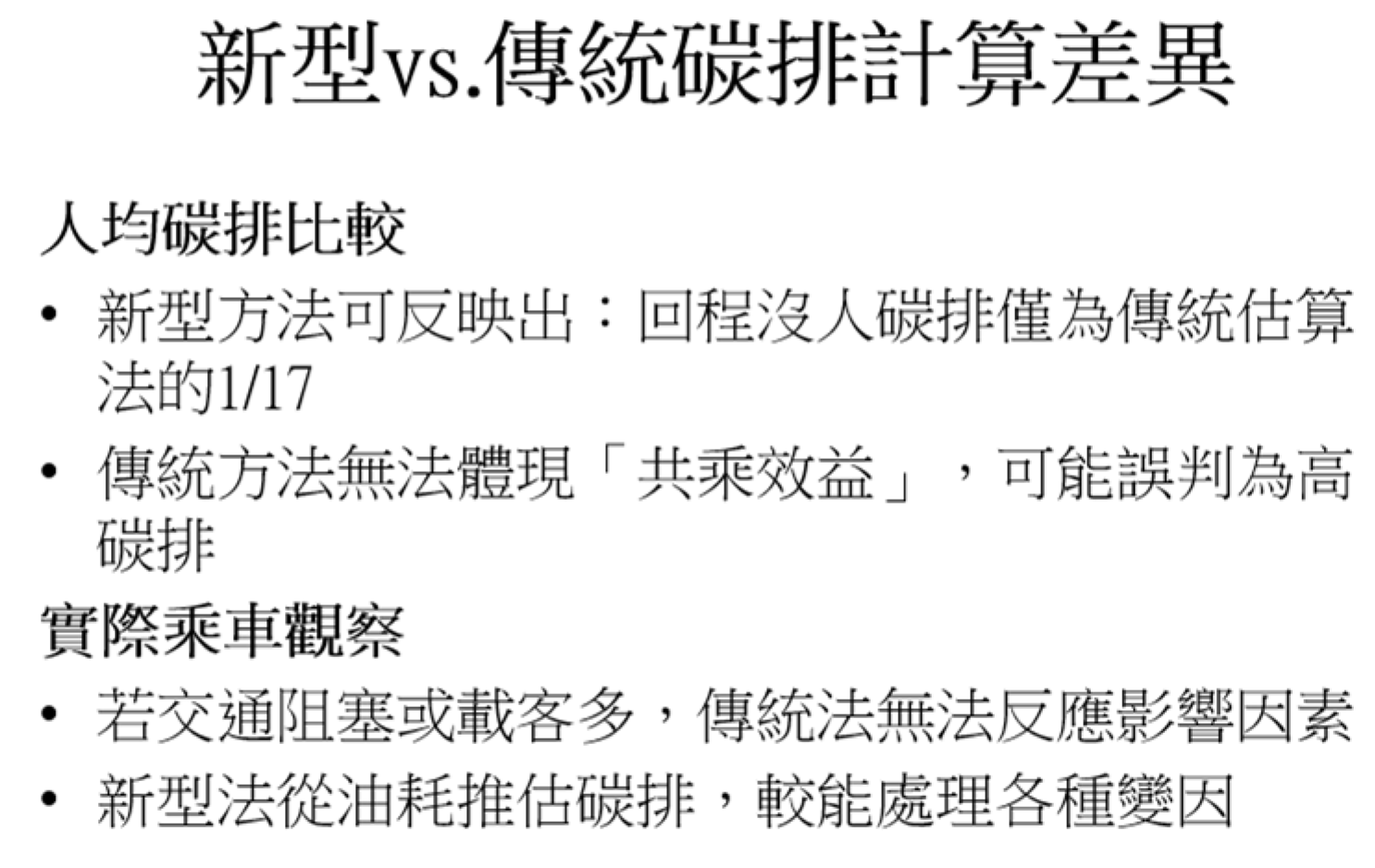

The first practical task, titled “Simulation and Analysis of Transportation Carbon Emissions”, required students to take public buses to simulate transportation behaviors arising from business-related activities. They recorded parameters such as departure and destination points, travel distance, number of passengers, duration, and average speed. Using emission factors published by DEFRA and the IPCC, students calculated carbon emissions via two methods: the traditional estimation and the advanced estimation (which considers passenger load and delays). Through the analysis process, students were encouraged to explore how travel time and occupancy rates affect carbon intensity, reflect on how commuting, business travel, or academic mobility contribute to the carbon footprint, and propose possible improvements. This task aimed at enhancing students’ critical thinking and data interpretation skills. The results of the students’ practical tasks are shown in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

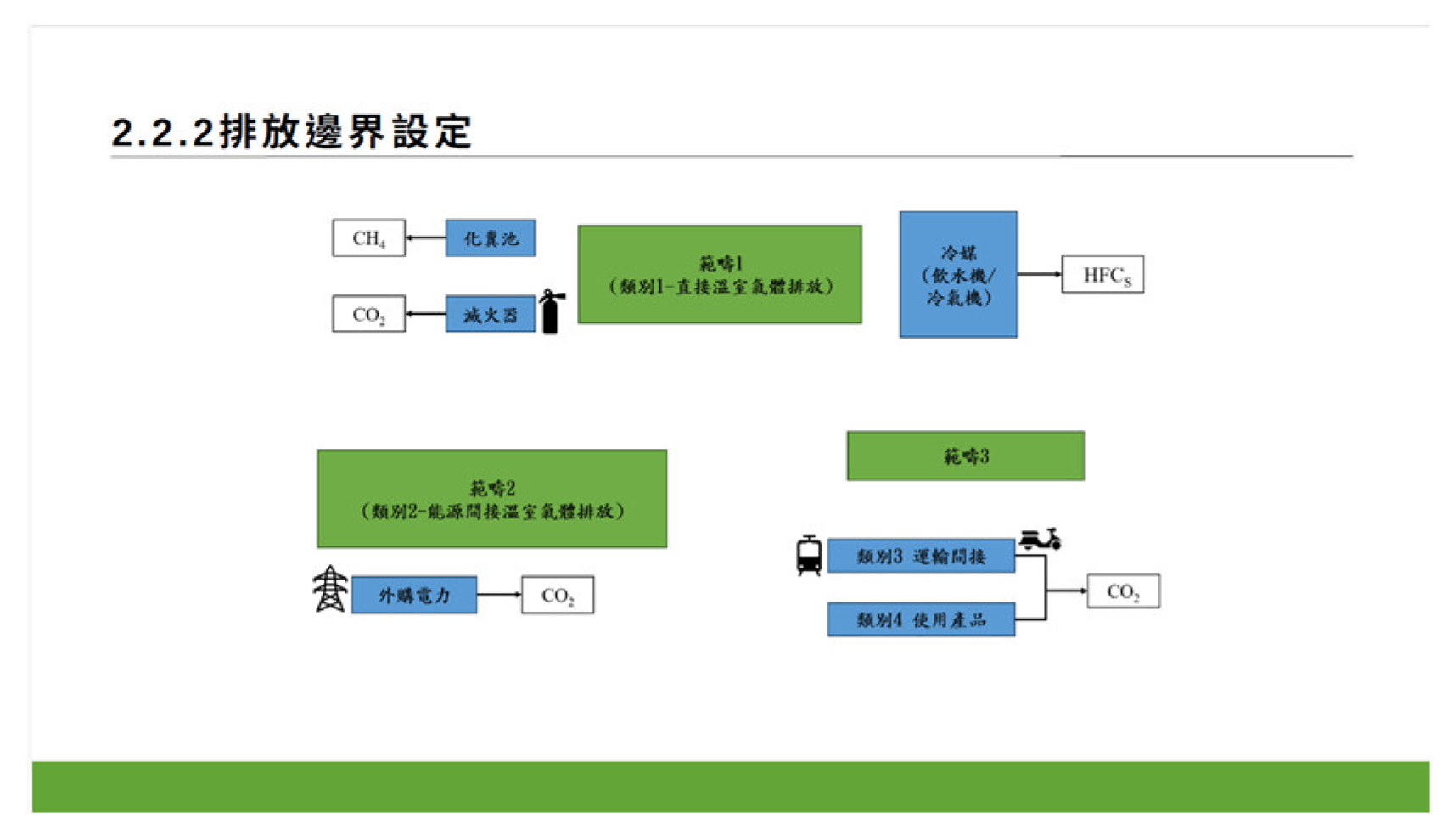

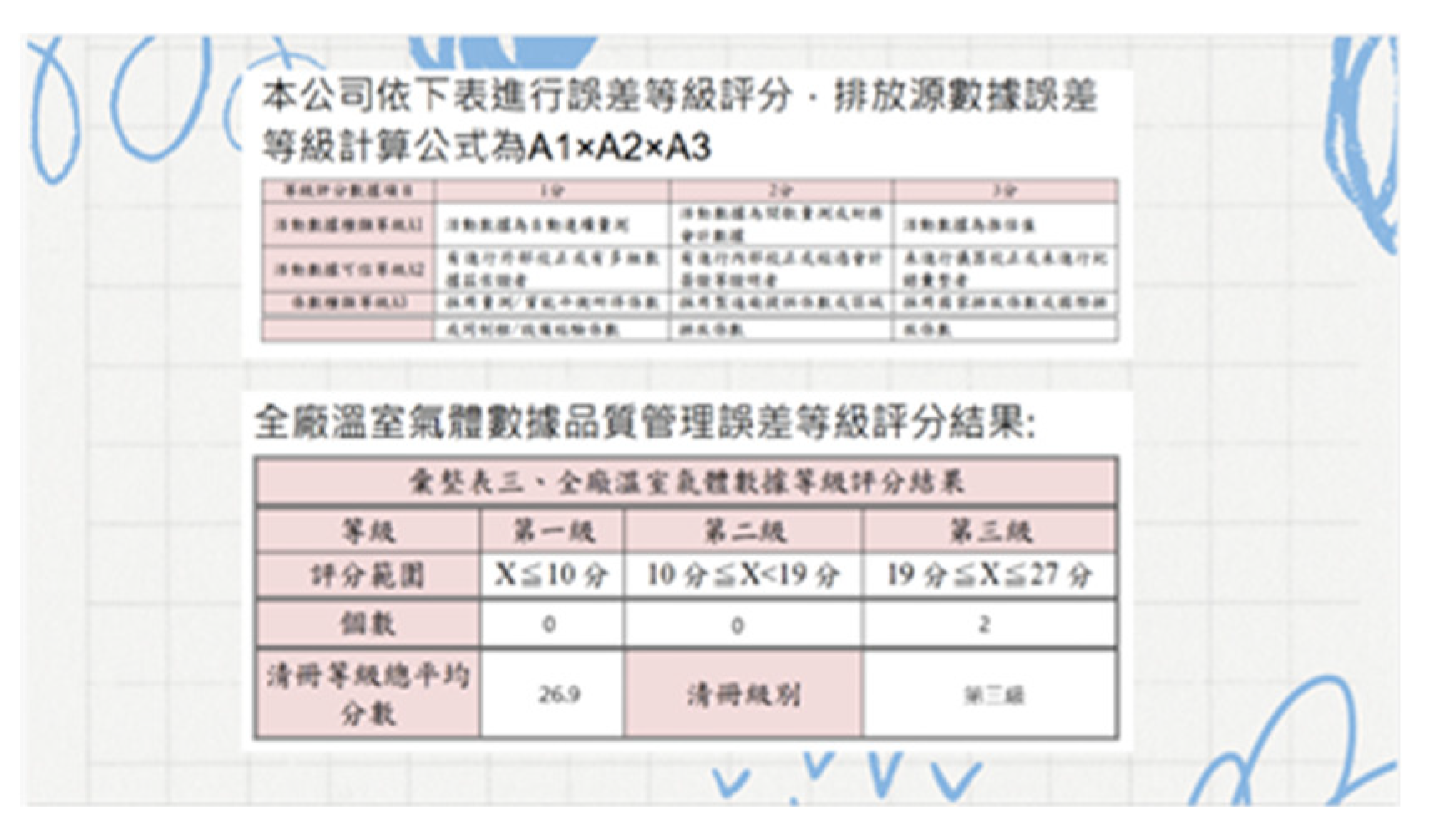

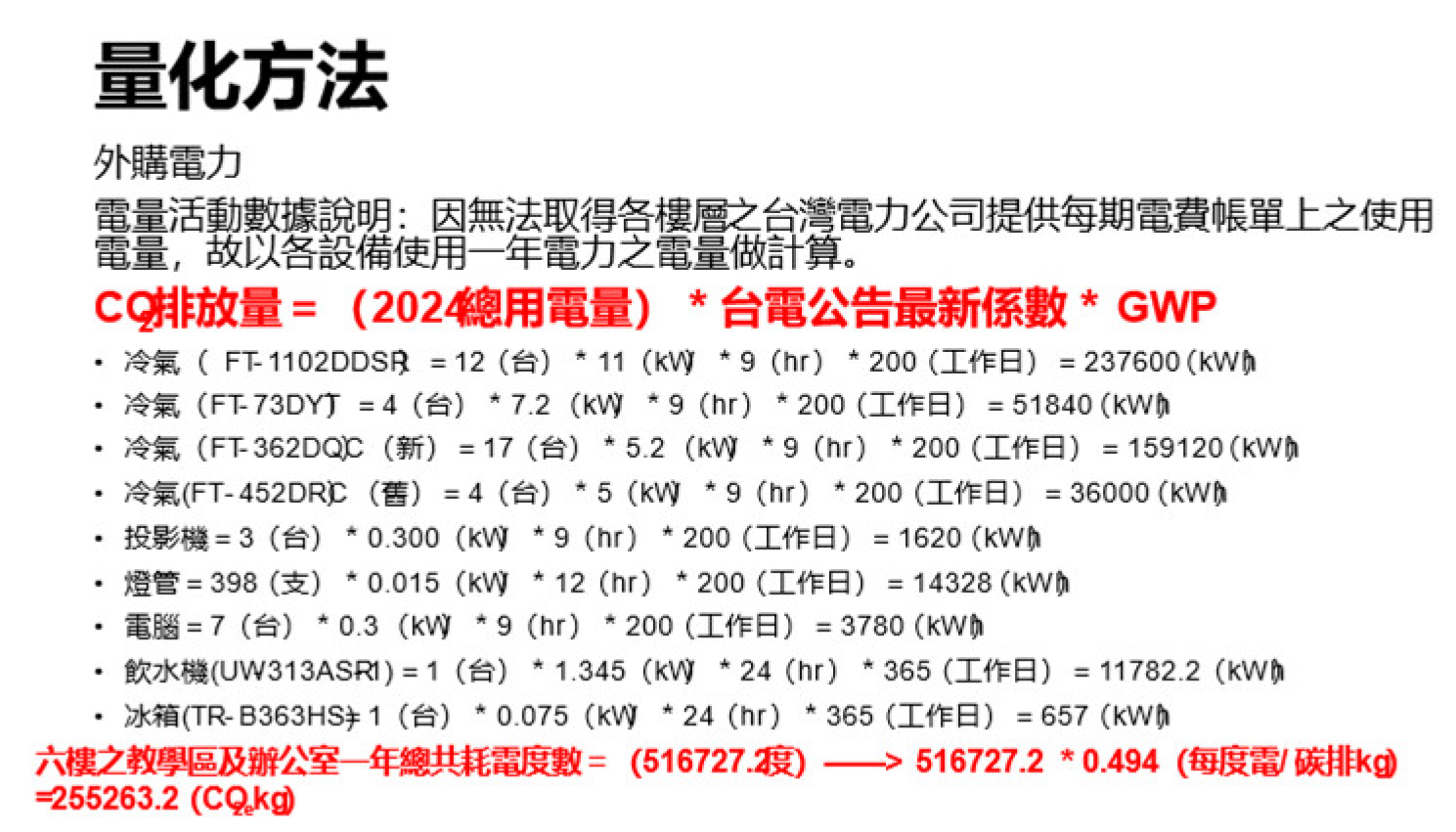

The second practical task, titled “Campus Building Carbon Inventory and Departmental Energy Structure Comparison,” guided students to conduct a simplified carbon inventory of university department buildings following the ISO 14064-1 framework. The focus was placed on Scope 2 emissions from electricity consumption and the identification and conversion of data related to major energy-consuming equipment.

During the course, students were instructed to investigate the types of teaching and research equipment used in different department buildings, along with their operating hours and energy consumption characteristics. For example, the Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering typically houses heavy machinery with high electricity demands; electrical and computer engineering departments may have server rooms requiring a stable and continuous power supply; while chemical and bioengineering laboratories often utilize reaction and ventilation equipment that also consume significant energy.

Students were required to estimate emissions based on the collected data and complete an inventory report. They then compared the energy consumption structures across different faculties and proposed concrete improvement strategies. This task not only deepened their understanding of carbon inventory processes but also enhanced their ability to integrate interdisciplinary knowledge and solve organizational-level sustainability problems. The results of the students’ practical tasks are shown in

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17.

Both of the aforementioned practical tasks are explicitly aligned with the UCAN Common Competency Indicators, emphasizing the cultivation of observable and measurable core competencies through task-based learning processes. The transportation carbon emission task requires students to record transport parameters and calculate emission factors, involving substantial data processing and analytical interpretation. This aligns with the indicators of Technological Information Application and Problem-Solving Ability. Moreover, the critical comparison of traditional versus advanced estimation models further enhances students’ Learning Ability and Innovative Thinking, encouraging them to transcend conventional logic and explore diverse perspectives in assessment.

In the campus carbon inventory task, students must tackle the analytical challenges posed by the heterogeneity of departmental buildings. Through data collection, energy activity conversion, and report writing, they are required to collaborate with peers across teams to complete presentations and project proposals, aligning with the indicators of Interpersonal Interaction and Communication Skills. Furthermore, by integrating the results of their carbon inventory to propose energy-saving strategies, students demonstrate their ability to apply professional knowledge creatively and solve problems effectively.

In summary, the design of these two project-based tasks not only facilitates students’ knowledge construction and technical practice in sustainability issues, but also concretely corresponds to the core competencies emphasized in ESD. By combining pre- and post-course questionnaires and learning process assessments, the course effectively verifies its impact and effectiveness in fostering students’ professional and transferable skills.

2.3. Methods

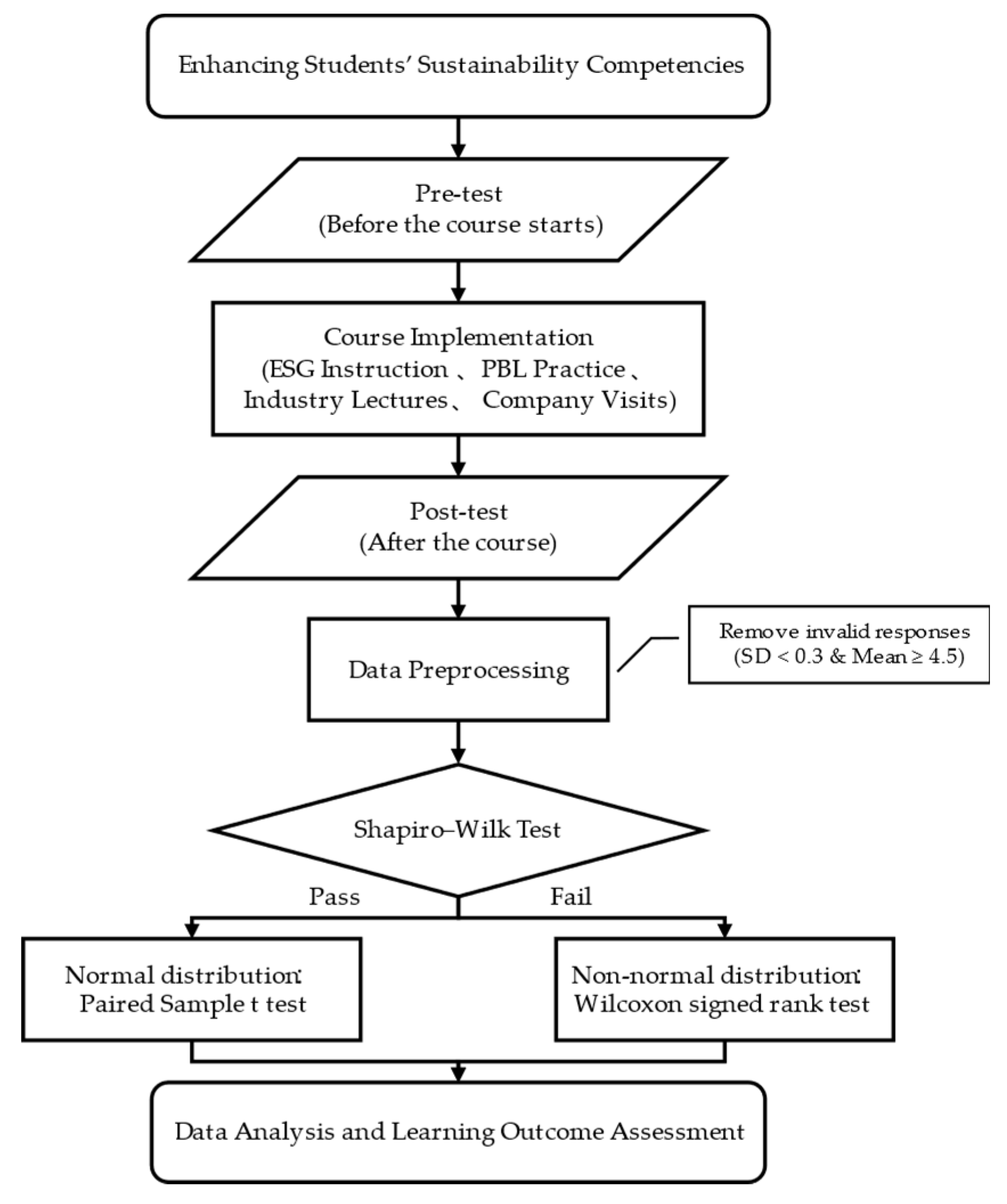

2.3.1. Research Procedure

This study’s research procedure integrates the actual steps of course implementation with a structured statistical validation framework. It emphasizes the use of quantitative data to examine changes in students’ learning outcomes across six core aspects: First Aspect: Communication, Second Aspect: Continued Learning, Third Aspect: Interpersonal Interaction, Fourth Aspect: Problem Solving, Fifth Aspect: Innovation, and Sixth Aspect: Information Technology Application. By following a systematic approach to data collection and analysis, the study not only rigorously responds to its research questions but also establishes a replicable assessment model for future instructional designs. This model can serve as an empirical reference for evaluating and tracking the effectiveness of similar sustainability-oriented curricula. The research procedure is illustrated in

Figure 18.

2.3.2. Participants

The participants of this study were students enrolled in the general education course “ESG Organization’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory, Decarbonization, and Net-Zero Curriculum” offered by the General Education Center at the university. A total of 84 students participated, representing diverse academic backgrounds across engineering, design, management, and humanities and social sciences, thereby reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the learning context.

2.3.3. Questionnaire

This study adopted the University Career and Competency Assessment Network (UCAN) questionnaire, developed by the Ministry of Education, Republic of China (Taiwan), as the instrument for evaluating students’ learning outcomes. The UCAN questionnaire is a nationally endorsed tool with strong construct validity and reliability, and it has been widely applied in competency-based education programs across universities in Taiwan. It assesses six core aspects: Communication, Continued Learning, Interpersonal Interaction, Problem Solving, Innovation, and Information Technology Application, providing a comprehensive and practical measure for evaluating students’ general competencies in higher education settings.

2.3.4. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

To evaluate the instructional effectiveness of this course in enhancing students’ core competencies, this study adopted a quasi-experimental one-group pretest–posttest design. After collecting the questionnaire responses, the research team performed data cleaning and screening to ensure data quality and analytical accuracy. A total of 32 valid samples were retained based on the following criteria: (1) each student’s response standard deviation in each aspect had to be greater than 0.3, excluding uniform or potentially inattentive answers; and (2) the average score had to be below 4.5, removing cases where students selected the highest rating for all items to reduce the ceiling effect. These criteria ensured that the dataset had sufficient variability and satisfied the assumptions of statistical analysis, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the research findings. Although the final sample size of 32 is relatively conservative, it was sufficient to reflect the course’s impact on students’ competency development and provides empirical support for future instructional refinement and promotion.

IBM SPSS was used as the primary tool for data processing and statistical analysis. The analysis included normality testing, paired sample t tests, and Wilcoxon signed rank tests. SPSS, a commonly used software in educational research, supports rigorous quantitative analysis and ensures the reliability and reproducibility of statistical outcomes. Normality of the pretest and posttest data was first examined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For data following a normal distribution, paired sample t-tests were applied to assess differences in learning outcomes. If the normality assumption was violated, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used as a non-parametric alternative[

26]. Addressing skewed data appropriately is crucial, as misidentifying distribution characteristics can lead to biased statistical inferences[

27]. This analytical procedure ensured that the study’s methodology adhered to statistical standards and yielded robust conclusions.

2.3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study strictly adhered to the principles of research ethics. All data collected were solely used for academic analysis and publication purposes related to this study. At the beginning of the course, students were fully informed about the purpose and content of the questionnaire. Participation in the survey was conducted only after obtaining students’ informed consent, thereby ensuring that the research process complied with ethical standards of respect, transparency, and legality.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Shapiro–Wilk Test

This study performed gain score calculations and normality testing on the pretest and posttest data of the valid samples. The gain score refers to the difference between each student’s posttest and pretest total scores in each aspect, serving as an indicator of competency change after the course intervention.

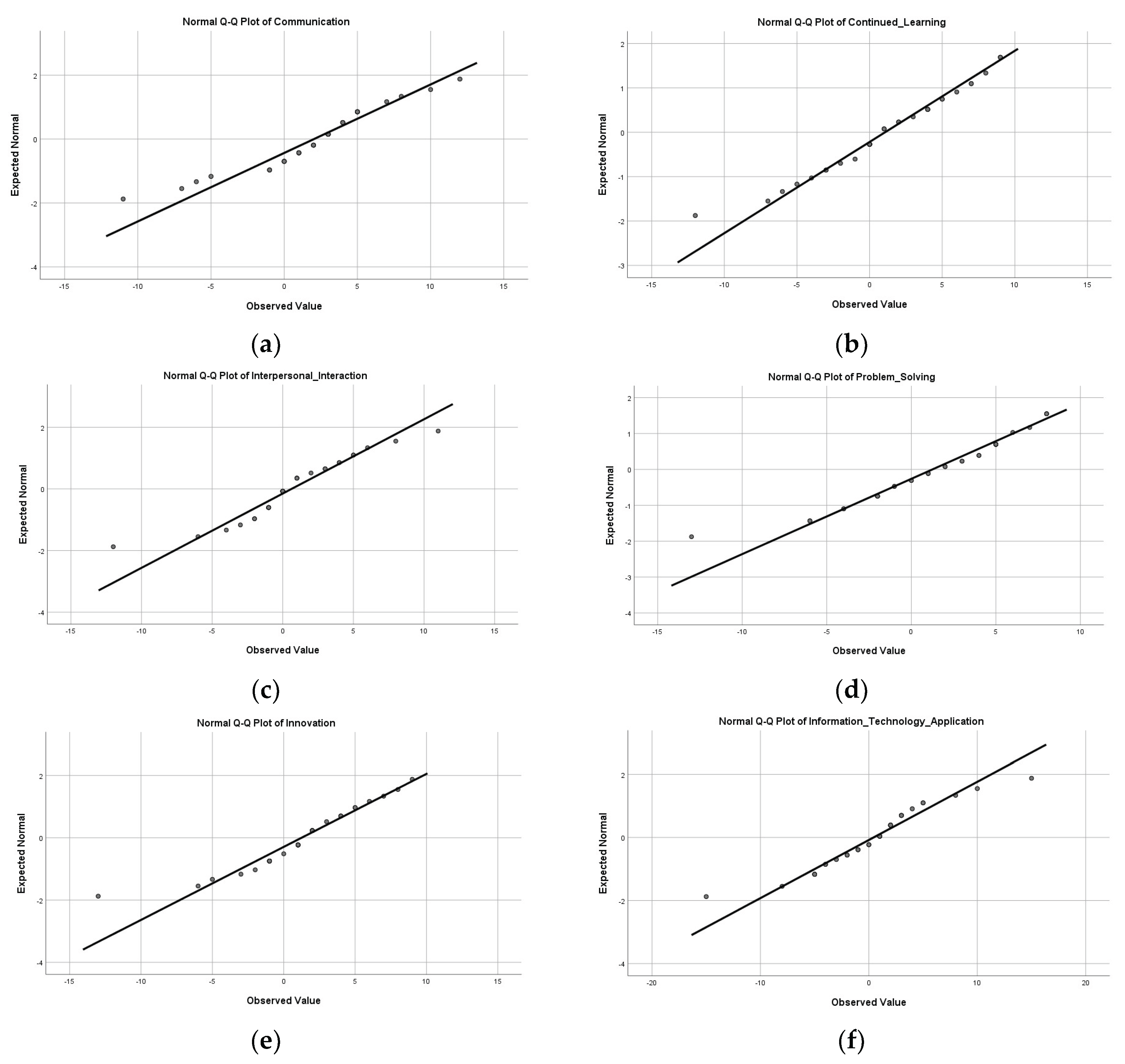

Given the sample size of 32, the Shapiro–Wilk test, known for its high statistical power and suitability for small samples, was employed to assess the normality of the data. A p-value greater than .05 was used as the criterion to determine whether the data followed a normal distribution. If p > .05, the result was considered to pass the normality test. The test results are summarized in

Table 1, and the Q–Q plots for each aspect are shown in

Figure 19.

Based on the results of the normality test, the subsequent statistical analysis methods were determined as follows. For the aspects that passed the normality test: Communication, Continued Learning, Problem Solving, and Information Technology Application, paired sample t tests were used. For the aspects that failed the normality test: Interpersonal Interaction and Innovation, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was employed for non-parametric analysis.

3.2. First Aspect: Communication

According to the results of the paired sample t test, as shown in

Table 2, there was a statistically significant difference in students’ scores in the Communication aspect between the pre-test and post-test (t = -2.463, df = 31,

p = 0.020). The negative mean difference (M = -2.031) indicates that post-test scores were generally higher than pre-test scores, suggesting that the course had a positive effect on improving students’ communication skills.

This improvement can be credited to the variety of learning activities included in the course, such as group discussions, scenario simulations, and project presentations, which gave students practical chances to practice their verbal expression and logical organization skills. Specifically, the midterm and final ESG case presentations required students to represent their groups in oral reporting and data synthesis, which effectively improved their presentation skills, oral communication, and teamwork. Additionally, industry expert lectures and company visits allowed students to participate in cross-functional communication settings, further deepening their understanding of professional language and interpersonal interactions. Overall, the notable improvement in the “Communication” aspect highlights the effectiveness of combining problem-based and practice-oriented teaching approaches in developing students’ professional language skills and interdisciplinary communication abilities.

3.3. Second Aspect: Continued Learning

According to the results of the paired sample t test, as shown in

Table 3, although students’ posttest scores in the aspect of Continued Learning showed an upward trend compared to the pretest, the difference did not reach statistical significance (t = -1.235, df = 31, p = .226). The mean difference was -1.062, indicating that posttest scores were slightly higher than pretest scores. However, there was considerable variability in student performance. While some students exhibited substantial improvement, others showed minimal change or even a slight decline, leading to greater overall data dispersion and reduced statistical significance.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, positive trends in students’ learning motivation and engagement were observed. The course employed diverse instructional strategies, such as the integration of sustainability topics, problem-based learning (PBL) tasks, carbon footprint calculation exercises, and ESG case discussions. These approaches progressively fostered students’ active learning attitudes and willingness to explore further.

In the latter part of the course, site visits to companies and interdisciplinary discussion activities were incorporated to help students connect classroom knowledge with real-world professional contexts, thereby enhancing their understanding of future career applications and driving learning motivation. Additionally, industry lectures that shared experiences related to industrial transformation and international net-zero trends helped students link theoretical knowledge to practical development, further strengthening their perceived value of learning and their willingness to engage in lifelong learning.

Overall, although the statistical analysis did not reveal a significant difference, students’ learning trajectories reflected positive behaviors such as continuous exploration, active learning, and cross-disciplinary understanding. Future studies are encouraged to adopt a longer observation period and integrate qualitative data to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of learning effectiveness in this aspect.

3.4. Third Aspect: Interpersonal Interaction

According to the results of the Wilcoxon signed rank test, as shown in

Table 4, there was no statistically significant difference in the median scores of students’ pretest and posttest in the aspect of Interpersonal Interaction (p = .329). Thus, the null hypothesis could not be rejected, indicating that students’ interpersonal interaction abilities did not show statistically significant changes after completing the course.

Although the course incorporated group discussions, collaborative presentations, and team-based assignments to enhance peer interaction, interpersonal interaction is generally considered a subtle and cumulative competency that often requires prolonged engagement in social contexts and real interpersonal experiences to show measurable improvement. Therefore, it is challenging to observe significant changes within the short duration of a single course.

In addition, the implementation period of this course was only 16 weeks, and some students might have already possessed a solid foundation in interpersonal skills. This limited variance may have also contributed to the lack of statistical significance. Nevertheless, classroom observations and student feedback revealed generally positive attitudes toward group collaboration and the division of labor in ESG case tasks. These findings suggest that the course still holds potential for fostering teamwork and communication. Future iterations could consider extending the duration of group activities or incorporating qualitative interviews to strengthen the evidence base.

3.5. Fourth Aspect: Problem Solving

According to the results of the paired sample t test, as shown in

Table 5, although students’ scores in the Problem Solving aspect showed an upward trend from pretest to posttest, the difference did not reach statistical significance (t = –1.484, df = 31, p = .148). This indicates that the improvement in students’ problem-solving ability after completing the course was not statistically confirmed.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, students were indeed exposed to a series of complex tasks during the later stages of the course. These included simulations of transportation carbon emissions, campus building carbon inventory analysis, and report writing for ESG cases. These tasks required students to interpret incomplete information and formulate strategies within limited time frames, closely mirroring real-world conditions. Such challenges contributed to the development of logical reasoning and strategic problem-solving skills, helping students gradually establish a systematic approach to tackling problems.

However, the internalization and demonstration of problem-solving abilities typically demand higher-order thinking and long-term training. As such, significant improvement in this area may not be easily reflected in short-term quantitative measures. Future implementations may consider extending the duration of project-based activities, increasing the frequency of decision-making simulations, and incorporating qualitative feedback or process records. These measures can enhance students’ reflection and strategy adjustment, thereby improving both the observability and statistical significance of learning outcomes in this aspect.

3.6. Fifth Aspect: Innovation

According to the results of the Wilcoxon signed rank test (

p = .027), as shown in

Table 6, the posttest median score for the Innovation aspect was significantly higher than the pretest score, indicating a notable improvement in students’ innovation performance after completing the course. Since the normality assumption was not met for this aspect, a non-parametric test was employed. The results demonstrate that the course had a statistically significant positive effect on students’ creative thinking and practical innovation abilities.

This improvement can be primarily attributed to the curriculum design, which integrated project-based tasks and problem-based learning activities centered around real-world ESG topics. Regardless of their academic backgrounds, most students had limited prior exposure to sustainability issues, making these topics relatively novel and challenging. Tasks such as estimating transportation-related carbon emissions and conducting campus building carbon audits required students to apply newly acquired methods, construct analytical frameworks, and generate feasible solutions independently. This process encouraged students to move beyond textbook knowledge and adopt diverse perspectives in interpreting sustainability challenges, leading to the development of original and actionable strategies.

While industry experts provided contextual background to support students’ understanding, their guidance ensured that students’ creative interpretations of sustainability issues were grounded in practical relevance and remained on the right track. Overall, the statistically significant improvement in this dimension confirms that the course’s integration of theoretical foundations and hands-on application effectively enhanced students’ capacity for creative thinking, interdisciplinary integration, and innovative problem interpretation.

3.7. Sixth Aspect: Information Technology Application

According to the results of the paired sample t test (t = −0.456, df = 31,

p = .651), as shown in

Table 7, students’ average post-test scores in the “Information Technology Application” dimension showed a slight increase compared to the pre-test, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. This result indicates that although the course included content related to digital tools and system operations, the students’ ability to apply information technology did not show significant improvement in this assessment.

One possible explanation is that the students enrolled in this course already possessed fundamental digital skills. As a result, the systems and tools adopted in the course, such as Excel and the Carbon Management System, did not present sufficient challenges to facilitate significant skill enhancement. Moreover, the course’s ICT components primarily served as supportive tools and did not focus on cultivating advanced abilities such as information integration, system analysis, or data visualization.

In addition, certain tools required students to manually input numerous parameters, which may have led to difficulties in correct usage due to a lack of familiarity. This highlights a need for future instructional designs to provide predefined parameter settings or guided simulation modules to help students develop a clearer understanding of system functions before actual operation.

Despite these limitations, the inclusion of practical components, such as the hands-on implementation of carbon inventory systems and ESG data organization tasks, still offered students opportunities to apply digital tools in real-world sustainability contexts. Future courses that incorporate more structured training in data analytics, visual representation, and ESG information platforms may further enhance students’ capabilities in Information Technology Application.

3.8. Qualitative Student Feedback

-

Improved Understanding of ESG and Carbon Inventory Topics:

Many students reported an enhanced understanding of ESG concepts, carbon inventory methods, and related terminology, including carbon tax, carbon credits, and net-zero emissions. Qualitative student feedback includes: “This course helped me understand the meaning and practice of net-zero carbon and how to conduct carbon inventory,” and “I learned a lot about carbon-related professional knowledge, such as what carbon credits and carbon taxes are, and why net-zero is important across industries.”

-

Positive Feedback on Course Design and Instruction

Students generally appreciated the course structure and the efforts of the teaching team, noting that both the instructors and teaching assistants were actively engaged. For example: “The teacher and TA were very dedicated; there were many activities,” and “The guest speakers made the course very rich,” and “The real-world case studies helped me realize that ESG is not just about ethics, but a critical factor for corporate competitiveness.”

-

Practical Experience through Practical Tasks and Field Visits:

Several students highlighted that assignments such as carbon emission simulations, transportation tracking, and energy audits deepened their understanding and interest in environmental issues. Feedback included: “Actually doing carbon inventory calculations helped me grasp the concept,” and “I learned a lot from this course, and the company visit enriched the overall experience.”

-

Challenges Faced and Suggestions for Future Improvement:

A few students expressed difficulty in comprehending some of the more complex course content. For instance: “The classroom atmosphere was relaxed, and I learned useful knowledge, but some deeper topics were hard to understand.” Others suggested that adding more examples of local business sustainability practices or site visits would enhance relevance and engagement.

4. Discussion

The results of this study revealed significant improvements in two of the six core competency aspects, communication and innovation, as evidenced by statistical significance (

p < .05). These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that problem-based learning (PBL) and authentic project tasks can effectively enhance students’ expressive and creative abilities, particularly when embedded within real-world sustainability issues (e.g., SDG-oriented education initiatives)[

28,

29,

30]. For example, the students’ increased performance in communication may be attributed to the inclusion of oral presentations, group discussions, and inter-group proposals, which align with prior studies emphasizing the role of collaborative discourse in strengthening workplace communication skills[

31,

32,

33].

On the other hand, competencies such as continued learning, interpersonal interaction, problem solving, and information technology application did not reach statistical significance. Nonetheless, all four demonstrated a consistent upward trend, suggesting that the course had a generally positive impact across multiple dimensions[

34,

35]. These partial gains may be attributed to the limited duration of the course (16 weeks)[

36], students’ varied academic backgrounds, and the inherent complexity of the subject matter, which encompasses carbon emission calculations, boundary setting, and multi-departmental collaboration.

In light of this, our findings contribute to the growing literature on sustainability education by demonstrating how integrated ESG and PBL frameworks can be applied effectively in a general education setting. Compared with similar studies that reported improvements in innovation and interdisciplinary thinking through active learning methodologies, our results affirm the value of immersive, data-driven projects such as carbon footprint estimation using the CarbonKeeper software and field-based carbon inventory assessments.

Given the technical depth and cross-disciplinary requirements of the course, lower-year students in particular faced challenges in comprehending emission factor systems (e.g., DEFRA and IPCC) and producing data-driven analytical reports. This suggests a need for differentiated instructional design or the incorporation of pre-course foundational modules to better support learners with limited prior exposure. These insights resonate with studies that underscore the importance of scaffolding and long-term experiential learning to foster higher-order problem-solving and sustained engagement[

37,

38,

39].

Future research could explore the course’s long-term effects on student behavior, career orientation, and sustainability literacy[

40,

41]. It may also be worthwhile to incorporate mixed-method approaches, such as follow-up interviews or classroom observations, to deepen the understanding of students’ cognitive and affective development[

42]. Furthermore, the course structure could be adapted for cross-institutional deployment, allowing comparative studies across contexts[

43] and helping to formulate a more unified pedagogical framework for sustainability education in higher education.

5. Conclusions

This study implemented a general education course that integrated problem-based learning and practical tasks focused on ESG and carbon inventory, aiming to enhance students’ sustainability competencies. The results of the paired sample t test and Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed significant improvements in the Innovation and Communication Aspects, while other areas, such as Continued Learning and Problem Solving, showed positive, though statistically non-significant, trends.

Despite the limited significance across all aspects, qualitative feedback demonstrated that students gained a clearer understanding of ESG-related topics and became more engaged through hands-on project tasks such as carbon footprint estimation, data collection, and campus site analysis. These findings suggest that the incorporation of real-world sustainability challenges can foster students’ creativity, critical thinking, and motivation to engage with emerging global issues.

Furthermore, the combination of classroom instruction, practical task design, expert insights, and field-based activities contributed to a learning environment that bridged theoretical content with real-world application. While industry experts provided contextual background, students were encouraged to independently explore complex sustainability challenges and transform their ideas into actionable solutions thereby strengthening their innovation skills.

To further enhance the educational impact, future courses may consider extending the duration of project implementation, incorporating advanced digital analysis tools, and reinforcing interdisciplinary collaboration. These improvements could help students consolidate their problem-solving abilities and information technology competence while deepening their engagement with sustainability topics. Overall, this research supports the potential of combining PBL with ESG-focused content to cultivate essential 21st-century competencies and sustainability literacy among students from diverse academic backgrounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T.C. and C.H.C.; methodology, C.T.C. and C.H.C.; software, C.T.C.; validation, C.T.C. and C.H.C.; formal analysis, C.T.C.; investigation, C.T.C.; resources, C.H.C.; data curation, C.T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T.C.; writing—review and editing, C.T.C. and C.H.C.; visualization, C.T.C.; supervision, C.H.C.; project administration, C.T.C. and C.H.C.; funding acquisition, C.H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Education Republic of China (Taiwan), grant number MOE-113-TPRGE-1022-001Y1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its nature as a non-clinical educational research project involving human participants through anonymous and voluntary participation. Although the study involved interaction and data collection from identifiable individuals or groups, it was conducted under the guidance of institutional policies requiring prior submission of recruitment and informed consent documentation. These documents included the name of the research institution and funding source, research objectives and methods, contact information of the principal investigator, protection mechanisms for participants’ rights and personal data, data retention and usage plans, and participants’ right to withdraw consent at any time.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Tatung University for this work. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Tatung University for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- da Costa, T.; Aranda Lopez, L.I.; Perussello, C.; Quinn, F.; Crowley, Q.G.; McMahon, H.; Holden, N.M. Addressing the Demand for Green Skills: Bridging the Gap Between University Outcomes and Industry Requirements. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.-T.; Pan, C.-L.; Zhang, Y. Collaborating on ESG consulting, reporting, and communicating education: Using partner maps for capability building design. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023, 11, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-C.; Lu, H.-Q. Competency and Training Needs for Net-Zero Sustainability Management Personnel. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tite, C.N.; Pontin, D.; Dacre, N. (2021). Embedding sustainability in complex projects: A pedagogic practice simulation approach. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2104.04068.

- Reimers, F.M. Educating Students for Climate Action: Distraction or Higher-Education Capital? Daedalus 2024, 153, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, A. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals Through Curriculum Innovation and Development. Journal of Arabic Language Teaching 2024, 4, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M.; Alanazi, F. Integrating environmental social and governance values into higher education curriculum. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) 2024, 13, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Escoffier, L.N.; Guerra, A.; Braga, M. Problem-Based Learning and Engineering Education for Sustainability: Where we are and where could we go? Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education 2024, 12, 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Ting Chien, a. C. H. C.(2024)。探討問題式導向教學法(PBL)結合線上測驗及教具在工程教育中提升學生核心能力的成效-以材料科學與工程導論(一)為例。「Chinese Society of Mechanical Engineers」發表之論文, Taiwan.

- Ji, D.-Y. (2024). POLICY OF COMMON COMPETENCY ASSESSMENT IN TAIWAN’S HIGHER EDUCATION AND ITS APPLICATION IN UNIVERSITY AFFAIRS DATA. European Journal of Education Studies, 11. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.C.; Hou, H.-Y.; Cheng, T.-M. The evaluation of competency-based diagnosis system and curriculum improvement of information management. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE) 2021, 17, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.-Y.; Wu, P.-J.; Chen, C.-T.; Huang, L.-W. Applying University Competence Assessment Network Common Competency and EMI Pedagogy. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE) 2025, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 何昕家, & 黃天麒. 探究STEAM教育實踐聯合國永續發展目標(SDGs)問題導向學習模式. [Integrating the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals into STEAM Education: A Problem-Based Learning Approach in Elementary and Secondary Education]. 教科書研究. 2024, 17, 79–117. [CrossRef]

- Beagon, U.; Kövesi, K.; Tabas, B.; Nørgaard, B.; Lehtinen, R.; Bowe, B. . Spliid, C.M. Preparing engineering students for the challenges of the SDGs: what competences are required? European Journal of Engineering Education 2023, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Molina-García, A.; García-Aranda, C.; Pérez, J.; Rodríguez, E. Understanding sustainability and the circular economy through flipped classroom and challenge-based learning: an innovative experience in engineering education in Spain. Environmental Education Research 2020, 26, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofel-Grehl, C.; Hansen, T.; Penrod, C.; Ellis, M. Pixels in a Larger Picture: A Scoping Review of the Uses of Technology for Climate Change Education. Journal of Science Education and Technology 2025, 34, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Peng, A.; Yang, T.; Deng, S.; He, Y. A Design-Based Learning Approach for Fostering Sustainability Competency in Engineering Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carracedo, F.; Segalas, J.; Bueno, G.; Busquets, P.; Climent, J.; Galofré, V.G. . Vidal, E. Tools for Embedding and Assessing Sustainable Development Goals in Engineering Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Boeve-de Pauw, J. The effectiveness of education for sustainable development revisited – a longitudinal study on secondary students’ action competence for sustainability. Environmental Education Research 2022, 28, 405–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polmear, M.; Bielefeldt, A.R.; Knight, D.; Canney, N.; Swan, C. Analysis of macroethics teaching practices and perceptions in engineering: a cultural comparison. European Journal of Engineering Education 2019, 44, 866–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, T.; Ali, S.; Sajid, M.; Akhtar, K. Sustainability of Project-Based Learning by Incorporating Transdisciplinary Design in Fabrication of Hydraulic Robot Arm. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.J.; Malheiro, B.; Arnó, E.; Perat, I.; Silva, M.F.; Fuentes-Durá, P. . Ferreira, P. Engineering Education for Sustainable Development: The European Project Semester Approach. IEEE Transactions on Education 2020, 63, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskaite-Taraseviciene, A.; Lagzdinyte-Budnike, I.; Gaiziuniene, L.; Sukacke, V.; Daniuseviciute-Brazaite, L. Assessing Education for Sustainable Development in Engineering Study Programs: A Case of AI Ecosystem Creation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadgraft, R.G.; Kolmos, A. Emerging learning environments in engineering education. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education 2020, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 蔡瀞慧, & 黃雲龍. 永續素養的教育研究發展趨勢. [Educational Research Trends of Sustainability Literacy]. 休閒研究. 2023, 12, 18–33.

- Nurwiani, T.; L. B. Independent samples t test and the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test to know the effect of the drill method on mathematics learning outcomes. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 2025, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, H.; Bhonge, P. (2025). Assessing Skew Normality in Marks Distribution, a Comparative Analysis of Shapiro Wilk Tests.

- Nurwidodo, N.; Wahyuni, S.; Hindun, I.; Fauziah, N. The effectiveness of problem-based learning in improving creative thinking skills, collaborative skills and environmental literacy of Muhammadiyah secondary school students. Research and Development in Education (RaDEn) 2024, 4, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamere, M.; Leon, M.; Fowles-Sweet, W.; Yeomans, L.; Fogg-Rogers, L. Using problem-and project-based learning to integrate sustainability in engineering education.

- García-Zambrano, L.; Ruiz-Roqueñi, M. Challenge based learning and sustainability: practical case study applied to the university. Journal of Management and Business Education 2024, 7, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thị, N.L.P. (2023). Investigation into the effectiveness of using problem-based learning in teaching communication skills in English to engineering students. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 17.

- Lestari, E.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Widyandana, D.; Scherpbier, A. Does PBL deliver constructive collaboration for students in interprofessional tutorial groups? BMC medical education 2019, 19, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menekse, M.; Purzer, S.; Heo, D. An investigation of verbal episodes that relate to individual and team performance in engineering student teams. International Journal of STEM Education 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. Journal of graduate medical education 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelsbrunner, P.A.; Thurn, C.M. Improving the utility of non-significant results for educational research: A review and recommendations. Educational Research Review 2024, 42, 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Guacas, A.F.; Chacón, M.F.; Munar, A.P.; Ospina, M.; Agudelo, M. Evolution of teaching in short-term courses: A systematic review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M.; Van der Veen, J.T. Scaffolding interdisciplinary project-based learning: a case study. European Journal of Engineering Education 2020, 45, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiort af Ornäs, V.; Keitsch, M. (2013). Teaching design theory: Scaffolding for experiential learning. Paper presented at the DS 76: Proceedings of E&PDE 2013, the 15th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Dublin, Ireland, 05-06.09. 2013.

- Richardson, J.C.; Caskurlu, S.; Castellanos-Reyes, D.; Duan, S.; Duha, M.S.U.; Fiock, H.; Long, Y. Instructors’ conceptualization and implementation of scaffolding in online higher education courses. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 2022, 34, 242–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundermann, A. (2024). Change in Sustainability Conceptions: A Mixed-methods Study of Undergraduates’ Learning Processes and Outcomes. Leuphana Universität Lüneburg.

- Leal Filho, W.; Viera Trevisan, L.; Sivapalan, S.; Mazhar, M.; Kounani, A.; Mbah, M.F. . Abzug, R. Assessing the impacts of sustainability teaching at higher education institutions. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.-T.; Ho, S.-T.; Lin, H.-C. Designing Cross-Domain Sustainability Instruction in Higher Education: A Mixed-Methods Study Using AHP and Transformative Pedagogy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annelin, A.; Boström, G.-O. (2024). Interdisciplinary perspectives on sustainability in higher education: a sustainability competence support model. Frontiers in Sustainability, Volume 5 - 2024. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

CarbonKeeper Software – Emission Source Identification.

Figure 1.

CarbonKeeper Software – Emission Source Identification.

Figure 2.

CarbonKeeper Software – Reports and Analysis.

Figure 2.

CarbonKeeper Software – Reports and Analysis.

Figure 3.

CarbonKeeper Software – Activity Data Collection.

Figure 3.

CarbonKeeper Software – Activity Data Collection.

Figure 4.

Staged Learning Design from ESG Concepts to Practice.

Figure 4.

Staged Learning Design from ESG Concepts to Practice.

Figure 5.

Why Conduct Carbon Inventory?

Figure 5.

Why Conduct Carbon Inventory?

Figure 6.

Value-Added Applications of Carbon Inventory and Practical Sustainability Reporting.

Figure 6.

Value-Added Applications of Carbon Inventory and Practical Sustainability Reporting.

Figure 7.

ISO 14064-2 Project-Based Carbon Reduction Methods and Taiwan’s Voluntary Emission Reduction Mechanism.

Figure 7.

ISO 14064-2 Project-Based Carbon Reduction Methods and Taiwan’s Voluntary Emission Reduction Mechanism.

Figure 8.

Why Carbon Inventory Matters.

Figure 8.

Why Carbon Inventory Matters.

Figure 9.

Visit to the Formosa Plastics Group Museum.

Figure 9.

Visit to the Formosa Plastics Group Museum.

Figure 10.

Carbon Emission Estimation Table.

Figure 10.

Carbon Emission Estimation Table.

Figure 11.

Bus Ride Record and Passenger Statistics.

Figure 11.

Bus Ride Record and Passenger Statistics.

Figure 12.

Bus Route Analysis Diagram.

Figure 12.

Bus Route Analysis Diagram.

Figure 13.

Traditional Carbon Emission Calculation Method.

Figure 13.

Traditional Carbon Emission Calculation Method.

Figure 14.

Comparison of New and Traditional Emission Calculation Methods.

Figure 14.

Comparison of New and Traditional Emission Calculation Methods.

Figure 15.

Definition of Emission Boundaries.

Figure 15.

Definition of Emission Boundaries.

Figure 16.

GHG Emission Source Significance Evaluation Criteria Table.

Figure 16.

GHG Emission Source Significance Evaluation Criteria Table.

Figure 17.

Model Calculation Methods and Results.

Figure 17.

Model Calculation Methods and Results.

Figure 18.

Research procedure.

Figure 18.

Research procedure.

Figure 19.

The Q–Q plots for each aspect. (a) First Aspect: Communication; (b) Second Aspect: Continued Learning; (c) Third Aspect: Interpersonal Interaction; (d) Fourth Aspect: Problem Solving; (e) Fifth Aspect: Innovation; (f) Sixth Aspect: Information Technology Application.

Figure 19.

The Q–Q plots for each aspect. (a) First Aspect: Communication; (b) Second Aspect: Continued Learning; (c) Third Aspect: Interpersonal Interaction; (d) Fourth Aspect: Problem Solving; (e) Fifth Aspect: Innovation; (f) Sixth Aspect: Information Technology Application.

Table 1.

Results of the Shapiro–Wilk Test.

Table 1.

Results of the Shapiro–Wilk Test.

| Aspect |

Shapiro-Wilk Test (p >.05) |

Normality Test Result

(pass/fail) |

| First Aspect: Communication |

.080 |

Pass |

| Second Aspect: Continued Learning |

.484 |

Pass |

| Third Aspect: Interpersonal Interaction |

.049 |

Fail |

| Fourth Aspect: Problem Solving |

.105 |

Pass |

| Fifth Aspect: Innovation |

.029 |

Fail |

| Sixth Aspect: Information Technology Application |

.179 |

Pass |

Table 2.

Paired sample t test results for Communication.

Table 2.

Paired sample t test results for Communication.

| Comparison |

Mean Difference |

t |

df |

p-value |

| Pre - Post |

-2.031 |

-2.463 |

31 |

.020* |

Table 3.

Paired sample t test results for Continued Learning.

Table 3.

Paired sample t test results for Continued Learning.

| Comparison |

Mean Difference |

t |

df |

p-value |

| Pre - Post |

-1.062 |

-1.235 |

31 |

.226 |

Table 4.

Wilcoxon signed rank test results for Interpersonal Interaction.

Table 4.

Wilcoxon signed rank test results for Interpersonal Interaction.

| Comparison |

Test Method |

p-value |

Statistical Conclusion |

| Pre vs. Post |

Wilcoxon signed rank test |

.329 |

Not statistically significant |

Table 5.

Paired sample t test results for Problem Solving.

Table 5.

Paired sample t test results for Problem Solving.

| Comparison |

Mean Difference |

t |

df |

p-value |

| Pre - Post |

-1.250 |

-1.484 |

31 |

.148 |

Table 6.

Wilcoxon signed rank test results for Innovation.

Table 6.

Wilcoxon signed rank test results for Innovation.

| Comparison |

Test Method |

p-value |

Statistical Conclusion |

| Pre vs. Post |

Wilcoxon signed rank test |

.027* |

Not statistically significant |

Table 7.

Paired sample t test results for Information Technology Application.

Table 7.

Paired sample t test results for Information Technology Application.

| Comparison |

Mean Difference |

t |

df |

p-value |

| Pre - Post |

-.437 |

-.456 |

31 |

.651 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).