Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

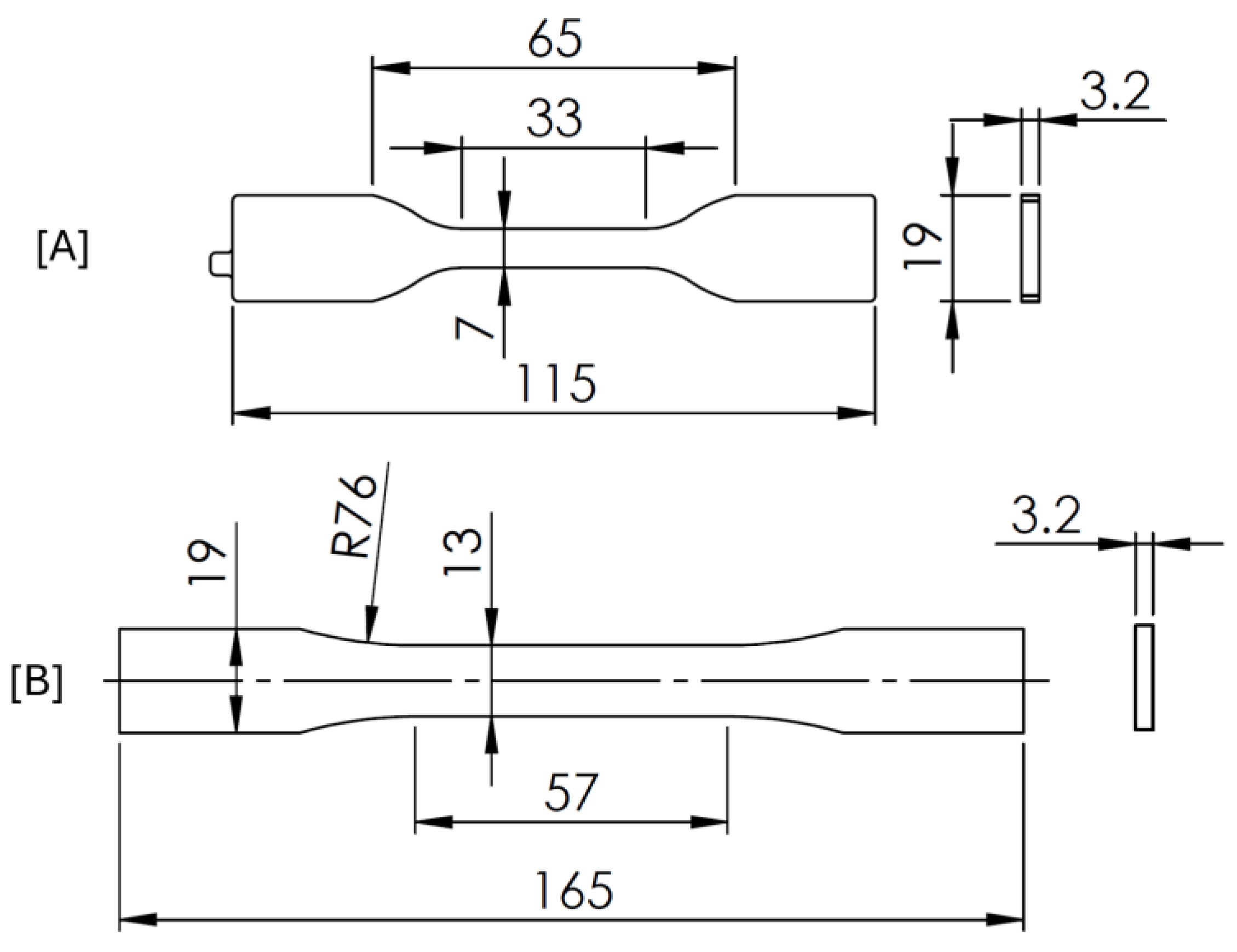

2. Materials and Testing Procedure

2.1. TPU

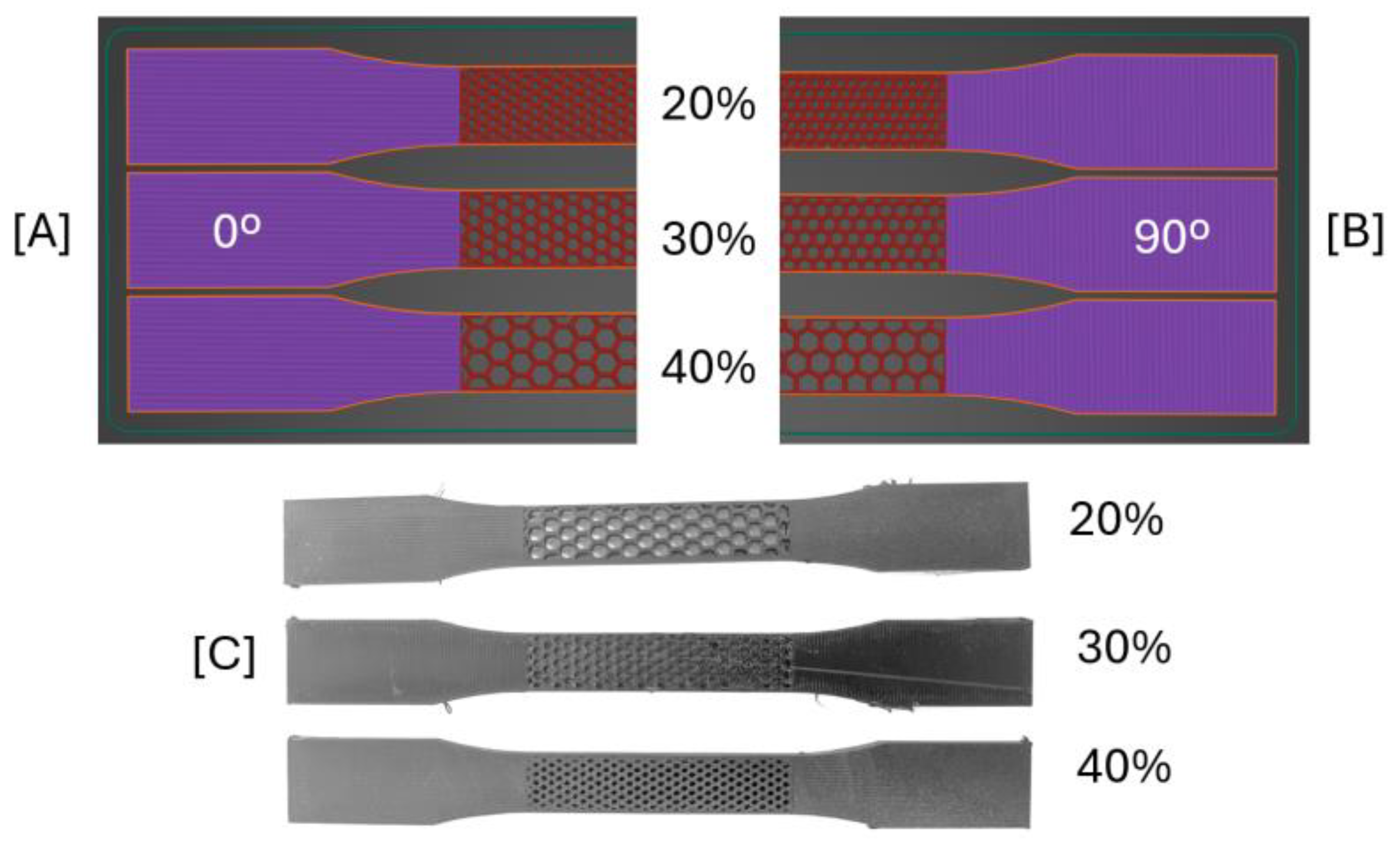

2.2. Composite

3. Results Analysis

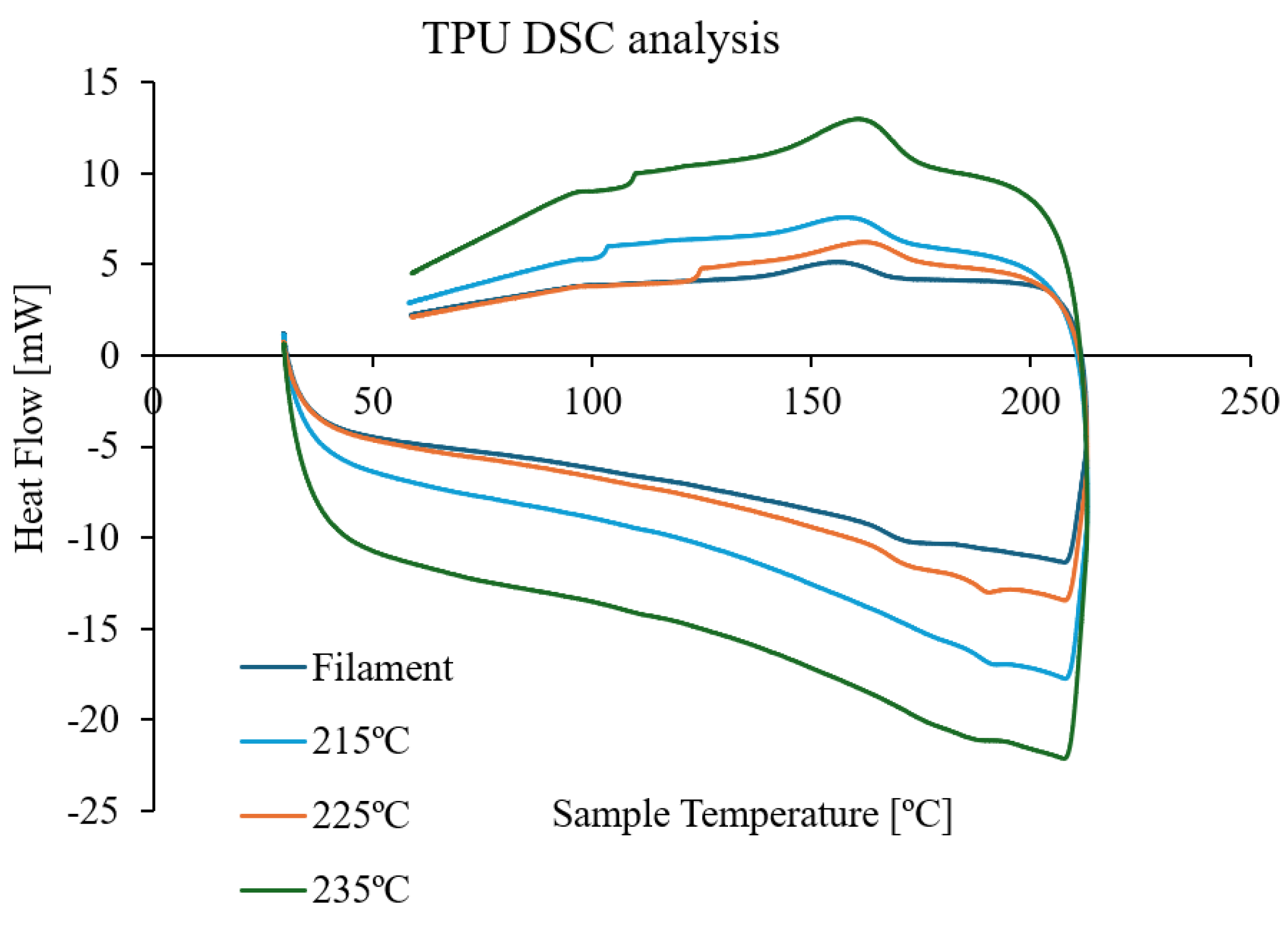

3.1. Thermal Characterization

3.1.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry Analysis (DSC)

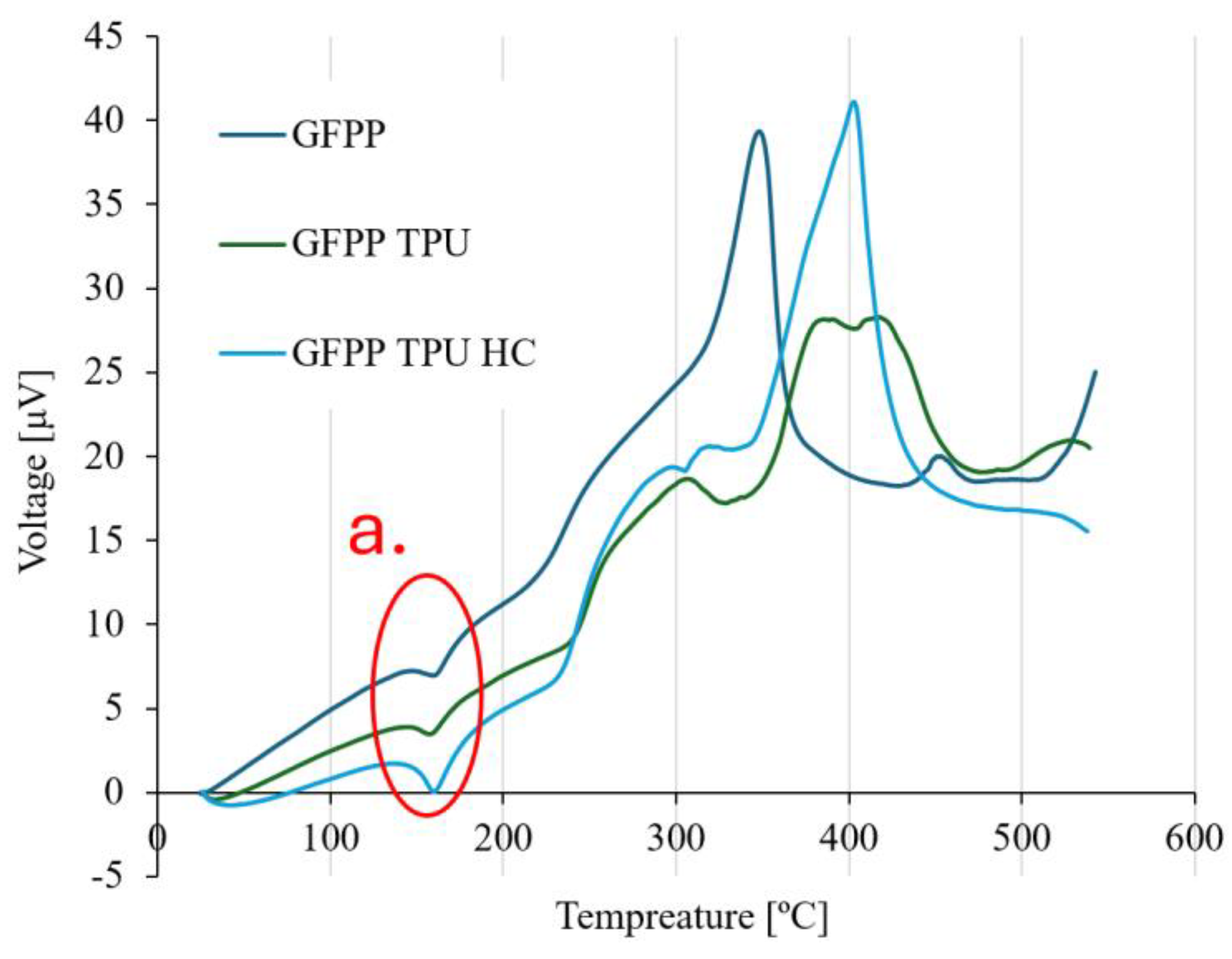

3.1.2. Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) / Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG)

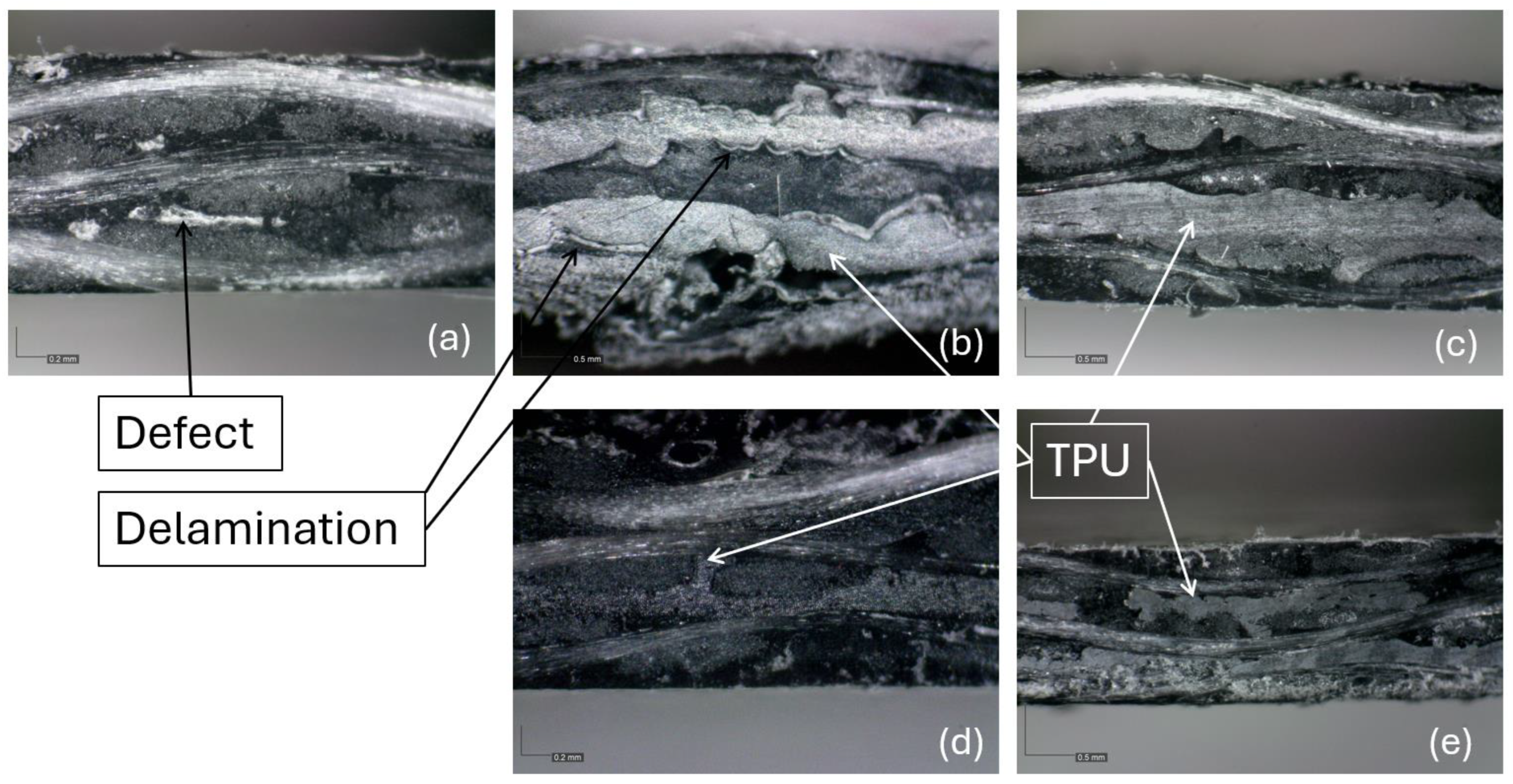

3.2. Surface Morphology

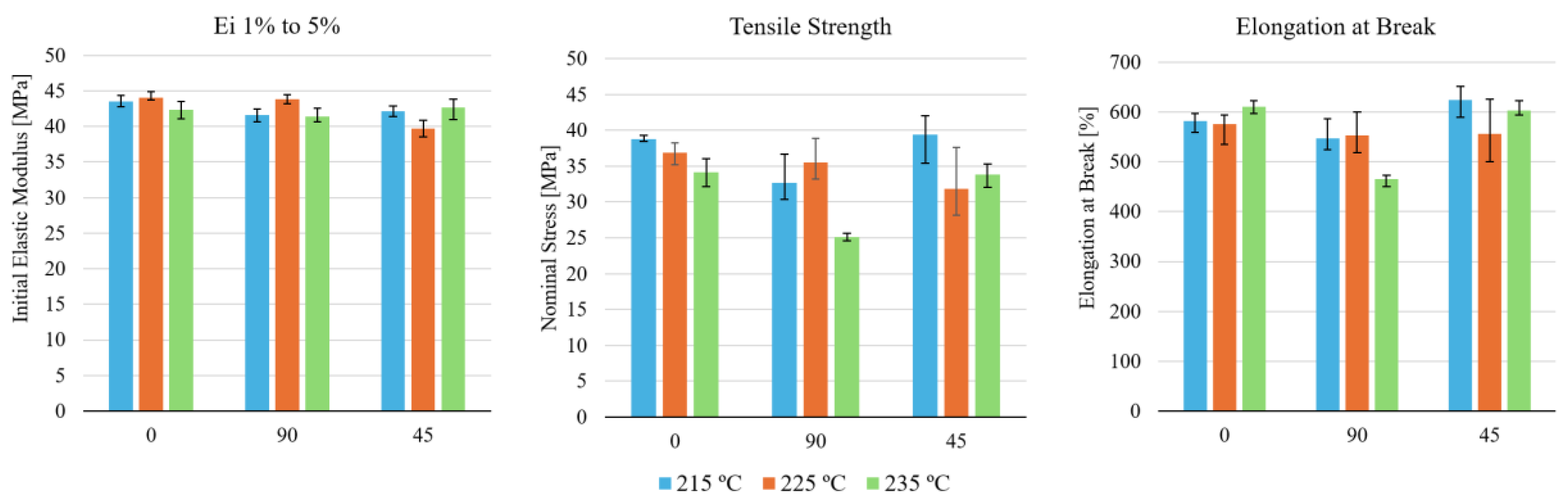

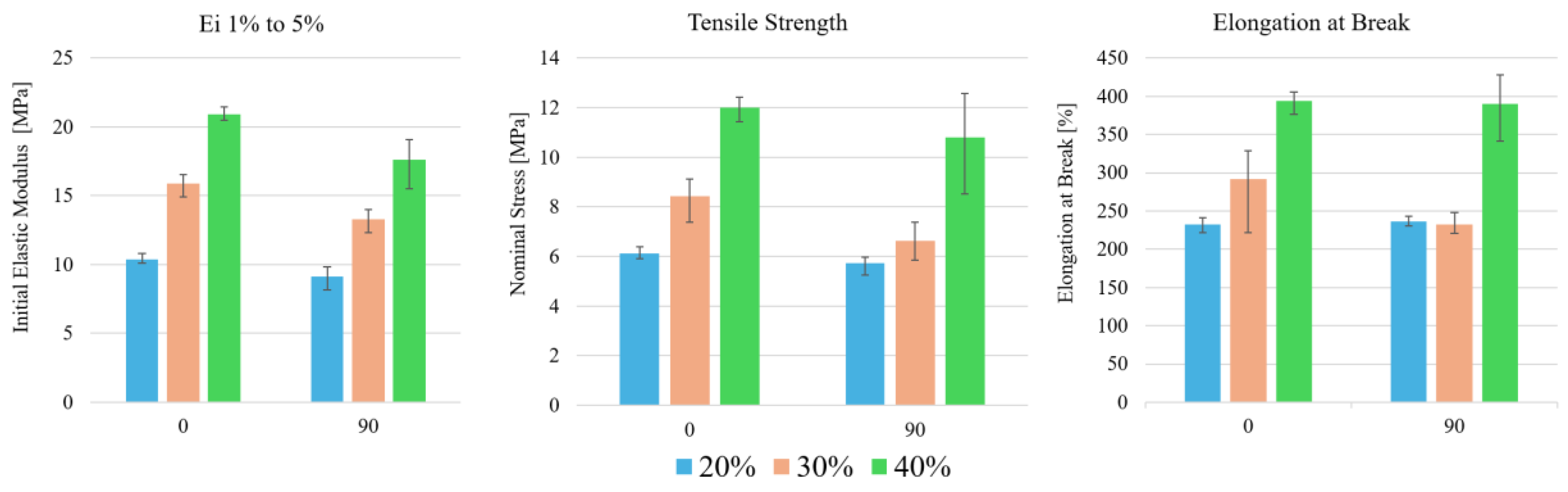

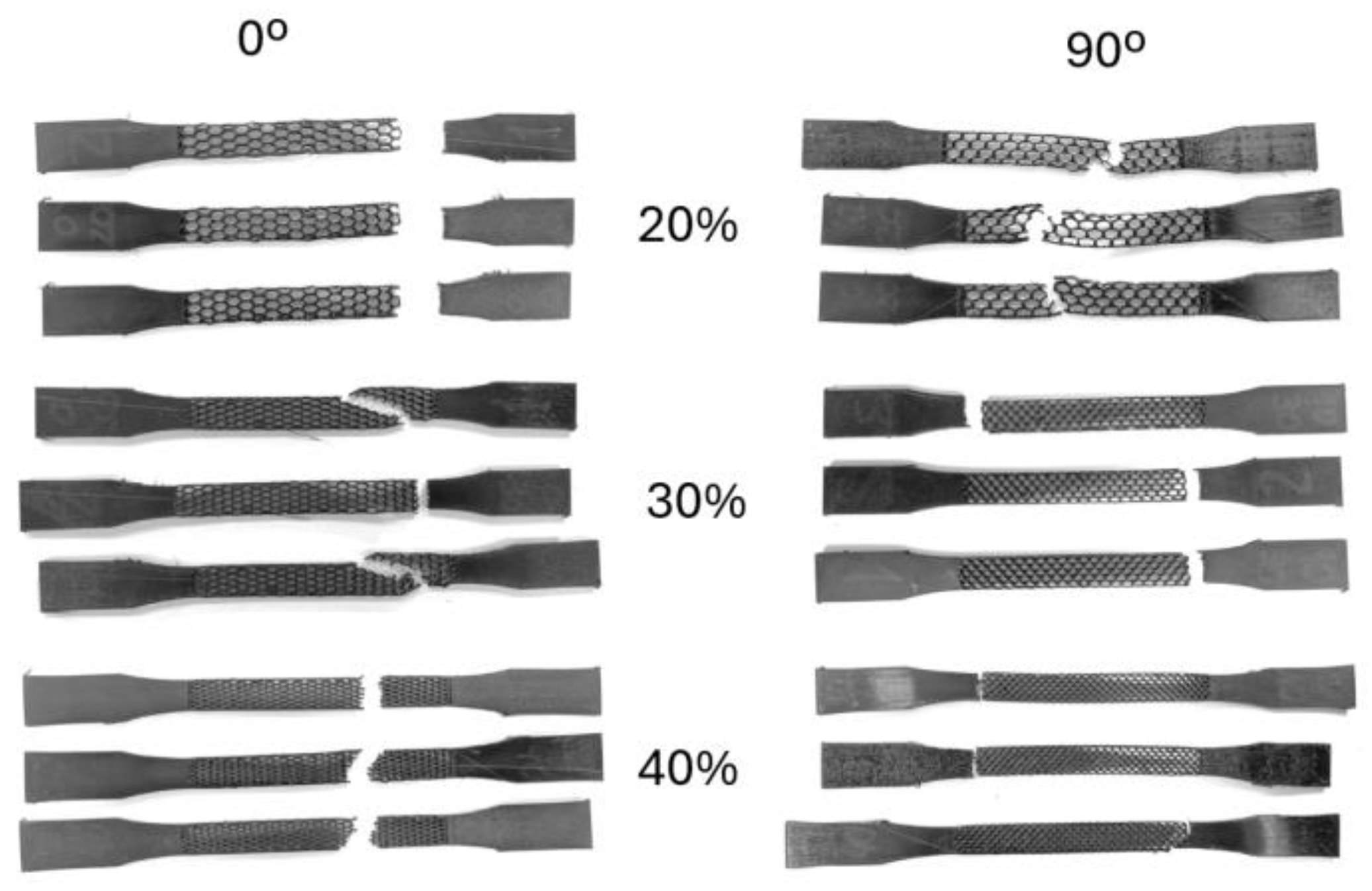

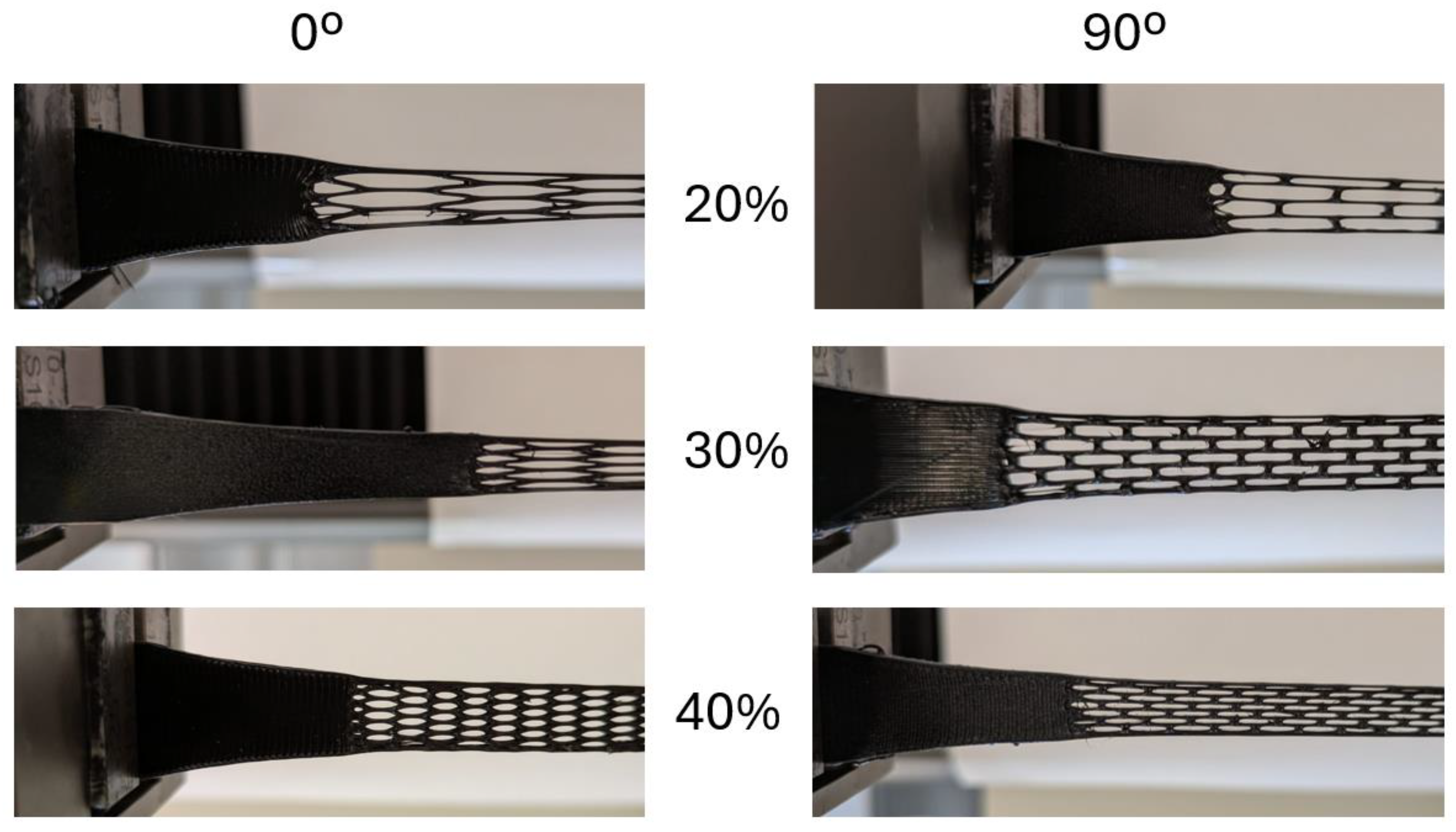

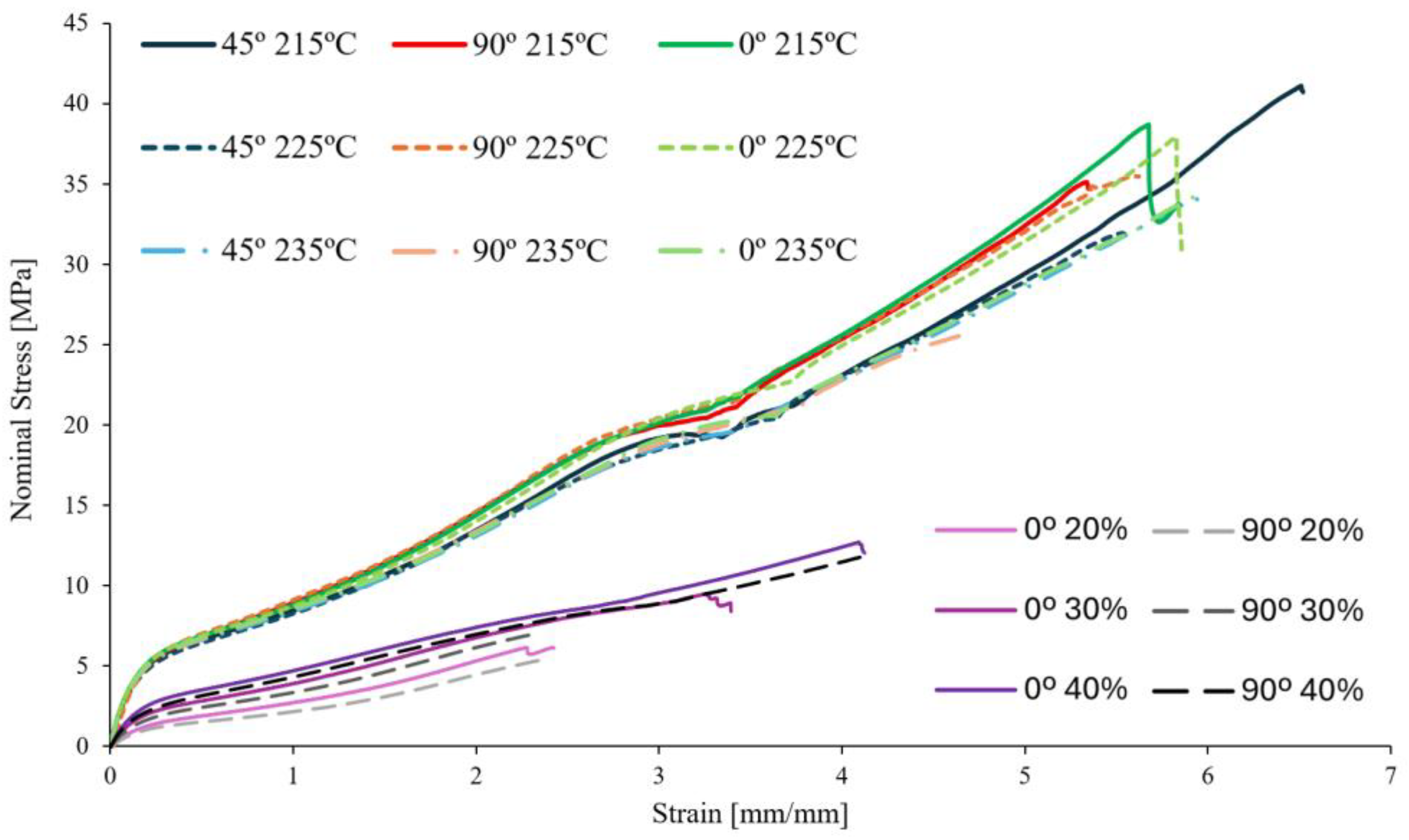

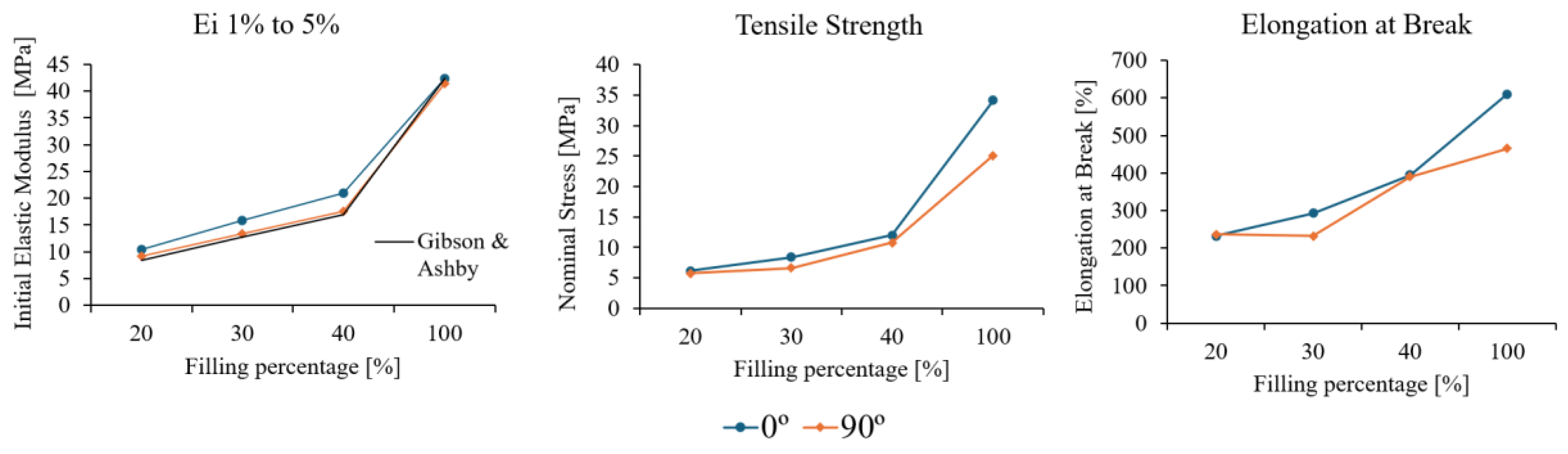

3.3. Tensile Testing

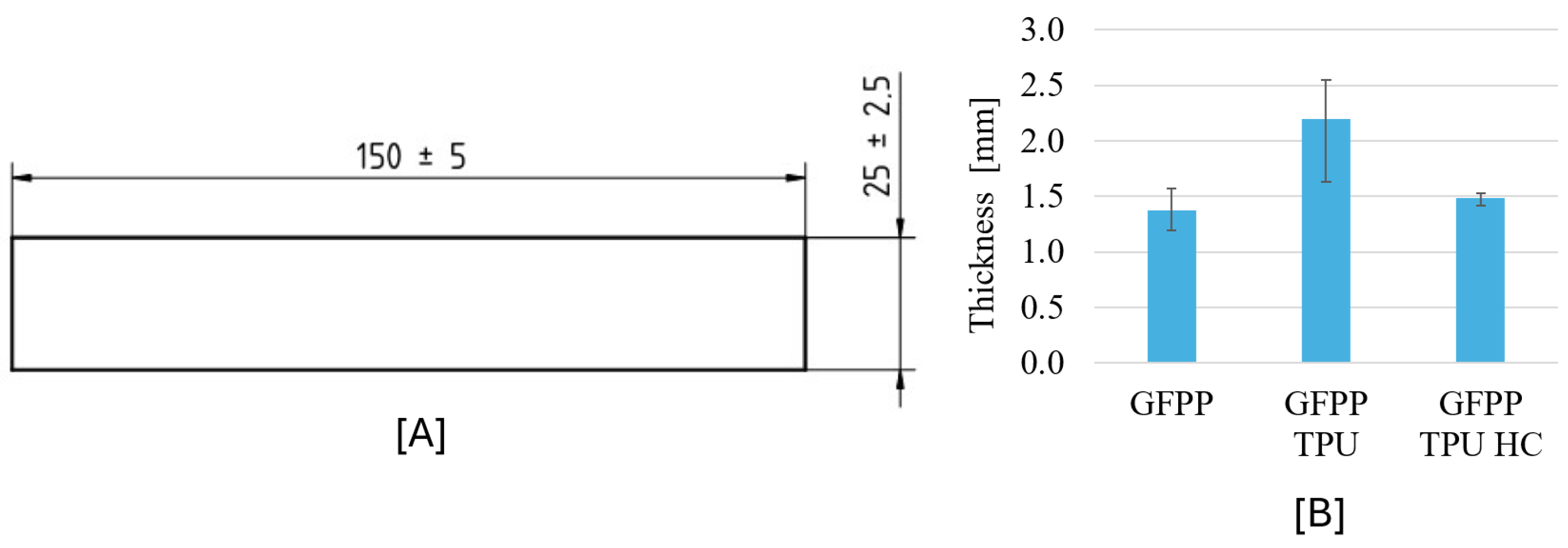

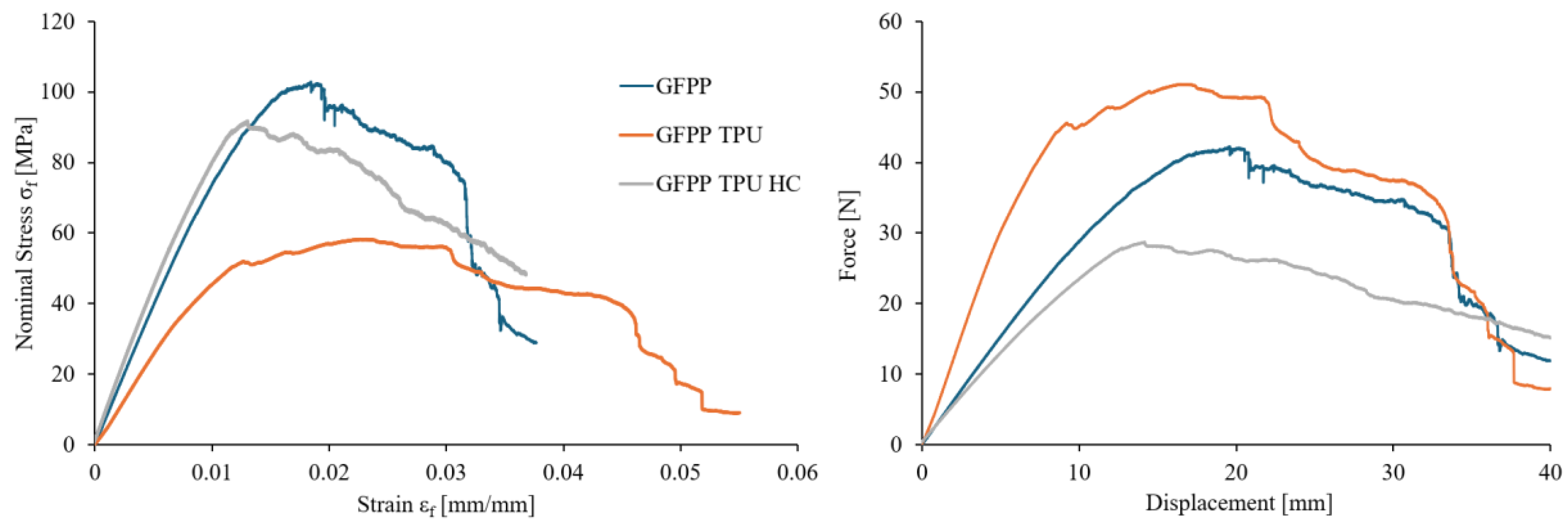

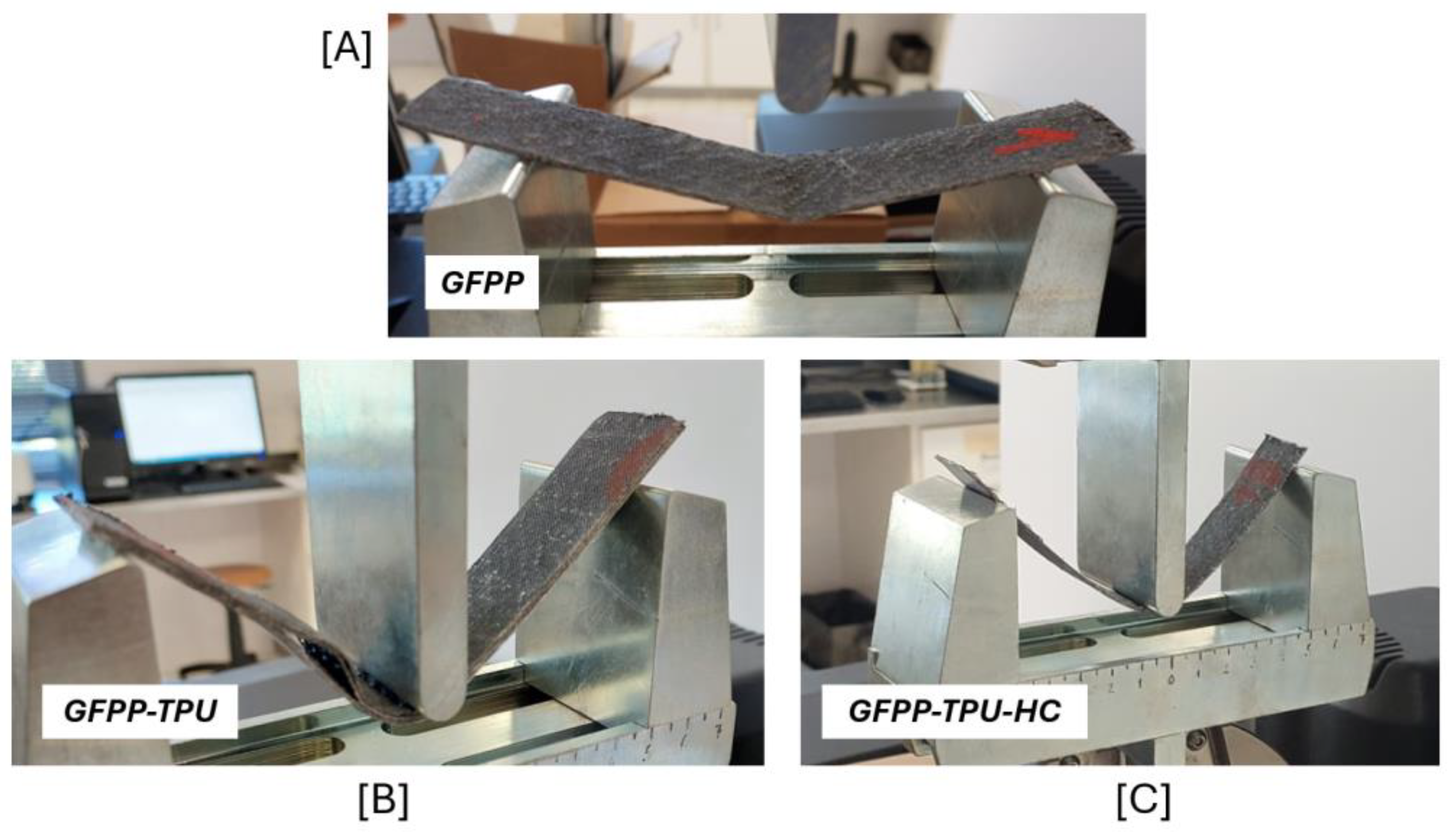

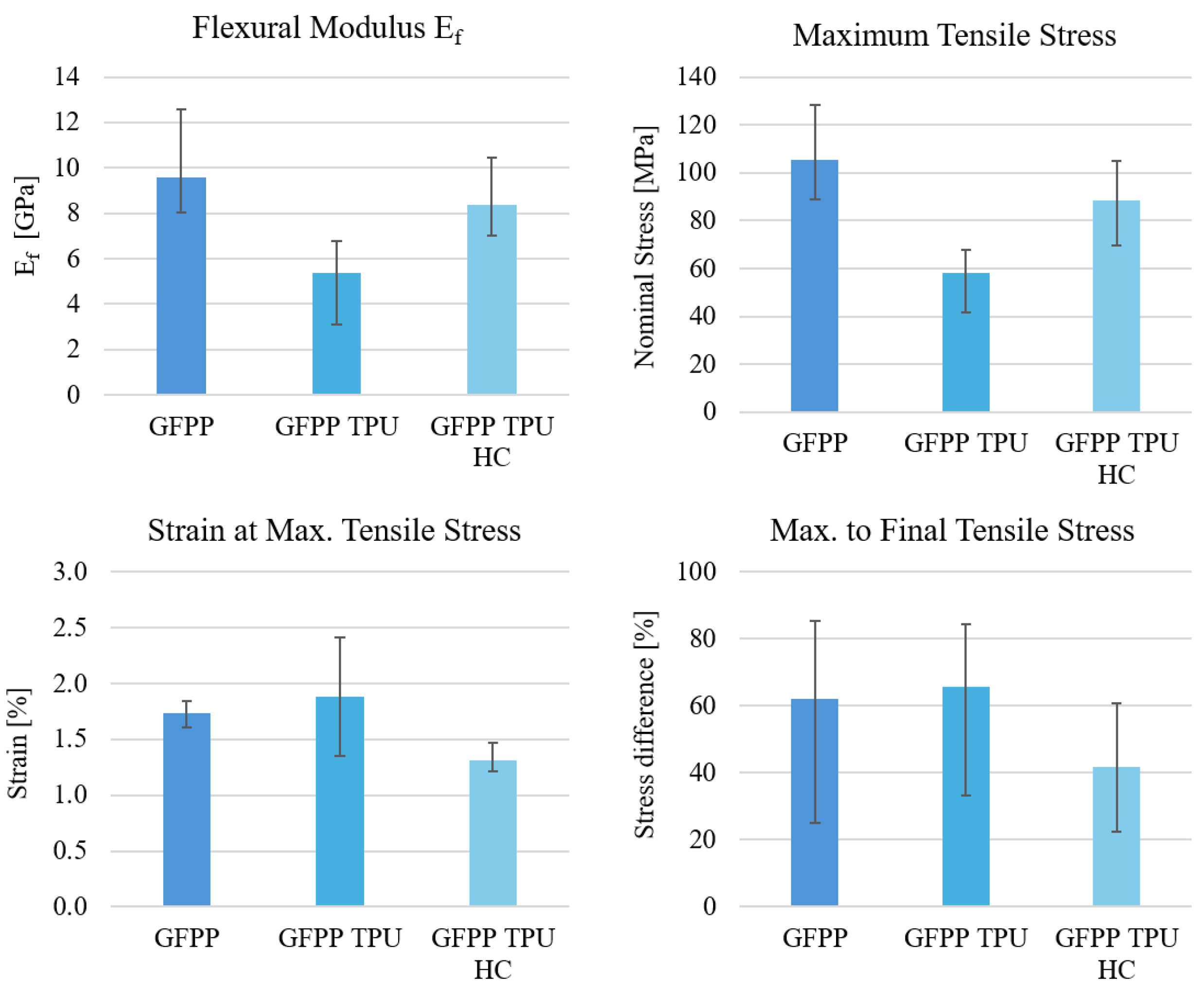

3.4. Bending Testing

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Jiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, F.; Hou, Z. Influence of Polymer Matrices on the Tensile and Impact Properties of Long Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilge, K.; Papila, M. Interlayer Toughening Mechanisms of Composite Materials. In Toughening Mechanisms in Composite Materials; Elsevier Inc., 2015; pp. 263–294 ISBN 9781782422914.

- Boyd, S.E.; Bogetti, T.A.; Staniszewski, J.M.; Lawrence, B.D.; Walter, M.S. Enhanced Delamination Resistance of Thick-Section Glass-Epoxy Composite Laminates Using Compliant Thermoplastic Polyurethane Interlayers. Compos Struct 2018, 189, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsotsis, T.K. Interlayer Toughening of Composite Materials. Polym Compos 2009, 30, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhameed, O.; Al-Ahmari, A.; Ameen, W.; Mian, S.H. Additive Manufacturing: Challenges, Trends, and Applications. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Huang, S.; Zhang, G.; Qin, R.; Liu, W.; Xiong, H.; Shi, G.; Blackburn, J. Progress in Additive Manufacturing on New Materials: A Review. J Mater Sci Technol 2019, 35, 242–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.M.S.; Sardinha, M.; Reis, L.; Ribeiro, A.; Leite, M. Large-Format Additive Manufacturing of Polymer Extrusion-Based Deposition Systems: Review and Applications. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2023, 8, 1257–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, H.K.; Davim, J.P. Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing; Harshit, K. Dave, J. Paulo Davim, Eds. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pulipaka, A.; Gide, K.M.; Beheshti, A.; Bagheri, Z.S. Effect of 3D Printing Process Parameters on Surface and Mechanical Properties of FFF-Printed PEEK. J Manuf Process 2023, 85, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Liu, T.; Yang, C.; Wang, Q.; Li, D. Interface and Performance of 3D Printed Continuous Carbon Fiber Reinforced PLA Composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2016, 88, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Harper, C. A. Harper, C. Handbook of Plastics, Elastomers & Composites, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Shen, W.; Lin, X.; Xie, Y.M. Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) Material Affected by Various Processing Parameters. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardinha, M.; Ferreira, L.; Diogo, H.; Ramos, T.R.P.; Reis, L.; Vaz, M.F. Material Extrusion of TPU: Thermal Characterization and Effects of Infill and Extrusion Temperature on Voids, Tensile Strength and Compressive Properties. Rapid Prototyp J 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifvianto, B.; Nur Iman, T.; Tulung Prayoga, B.; Dharmastiti, R.; Agus Salim, U.; Mahardika, M. Tensile Properties of the FFF-Processed Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) Elastomer. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2021, 117, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, P.; Sardinha, M. ; M. Vaz, F.; Reis, L. Design and Stiffness Assessment of Non-Pneumatic Bicycle Tyres with Latticed Cores Produced by Fused Filament Fabricationsite) Journal Name. Journal of Materials: Design and Applications.

- Mian, S.H.; Abouel Nasr, E.; Moiduddin, K.; Saleh, M.; Alkhalefah, H. An Insight into the Characteristics of 3D Printed Polymer Materials for Orthoses Applications: Experimental Study. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardinha, M.; Ferreira, L.; Ramos, T.; Reis, L.; Vaz, M.F. Challenges on Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing of Thermoplastic Polyurethane. Engineering Manufacturing Letters 2024, 2, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International D638 - 14 Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Pham, R.D.; Hütter, G. Influence of Topology and Porosity on Size Effects in Stripes of Cellular Material with Honeycomb Structure under Shear, Tension and Bending. Mechanics of Materials 2021, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Shu, X. Size Effects on the In-Plane Mechanical Behavior of Hexagonal Honeycombs. Science and Engineering of Composite Materials 2016, 23, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhattab, K.; Bhaduri, S.B.; Sikder, P. Influence of Fused Deposition Modelling Nozzle Temperature on the Rheology and Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed β-Tricalcium Phosphate (TCP)/Polylactic Acid (PLA) Composite. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM International D790-17 Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials 2017.

- Gibson J., Lorna; Ashby, F. Michael Cellular Solids Structure and Properties; second. 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Shore Hardness |

Density [kg/m3] |

Tensile Strength [MPa] |

Elongation at Break [%] | Young Modulus [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92A | 1149 | 44.2 | 661 | 48.4 |

| Glass Transition Temperature [ºC] | Melting Temperature [ºC] | Recommended Nozzle Temperature [ºC] |

|---|---|---|

| -25 | 144 | 210-230 |

| Consolidation Temperature [ºC] | Glass fibre content by volume [%] | Nominal Weight [g/m2] |

Density [kg/m3] |

Thickness of fully consolidated ply [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 190-230 | 35% | 700 | 1560 | 0.47 |

| Tested Material | Melting Temperature Tm |

|---|---|

| Filament TPU95A Ultrafuse | 172.1 ºC |

| FFF extruded at 215ºC | 191.0 ºC |

| FFF extruded at 225ºC | 190.1 ºC |

| FFF extruded at 235ºC | 185.1 ºC |

| Mass Fraction [%] | Volume Fraction [%] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | Fibre Glass | Polymer | Fibre Glass | Polymer |

| GFPP | 62.5 | 37.5 | 37.7 | 62.3 |

| GFPP-TPU | 51.4 | 48.6 | 25.9 | 74.1 |

| GFPP-TPU-HC | 56.9 | 43.1 | 35.4 | 64.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).