1. Introduction

“…the plaque count of successive samples remains constant until the end of the latent period when lysis begins.” Adams [

1], p. 15

After phage titering, along with phage host-range determination, a key breakthrough in the quantitative development of phage biology was the one-step growth curve [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] , also described as “single step growth” [

8]. These experiments, at their most basic, consist of following, through time, what can be described as infective centers [

1,

4], which today are more commonly known as plaque-forming units (PFUs). This is from a pre-lysis phage-infected state, through lysis (described as a rise), and finally to a stable, post-lysis or ‘post-rise’ state. Summers [

9] described this OSG technique as having been “systematized” in 1939 by Emory Ellis and his one-time collaborator, Max Delbrück [

2]. Summers added, however, that one-step growth-type experiments had existed “since the early days of d’Herelle” (p. 41); see Sankaran [

10] for details of the latter. Stent [

4], furthermore, described one-step growth experiments (p. 72) as what “marked the beginning of modern phage work”.

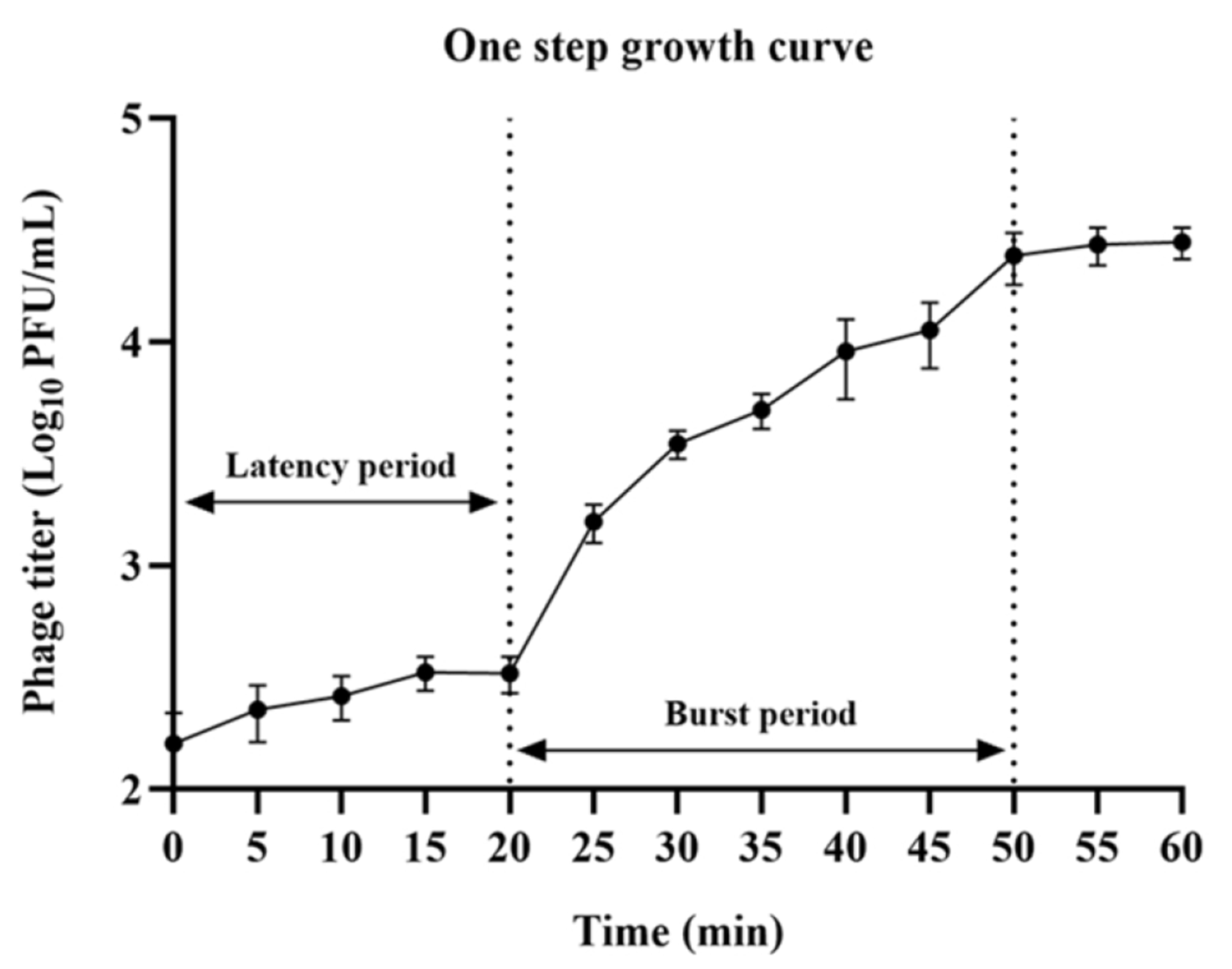

The OSG technique provides two key aspects of what can be labeled as a phage’s growth parameters, organismal-level phenotypes, or life-history characteristics [

11]. Specifically, these important aspects of the phage life cycle are what are known as the phage latent period, which is the length of a phage’s lytic cycle [

12], and the number of new virions produced and released by a phage-infected cell, called the burst size. Technically, these are ‘minimum latent period’ (also known as a ‘constant period’) and ‘average burst size’, respectively [

1,

3]. Together, these two values, along with measures of virion durability and adsorption rates [

13], determine both the rapidity and extent with which phages can increase their population sizes. This thereby controls the impact of phages on bacterial populations. The degree of impact of phages on bacterial populations is crucial, for example, toward determining the success of phages as antibacterial therapeutic agents, often described as phage therapies [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. They also are important in ascertaining the potential impact of phages on bacterial ecology [

22] as well as on bacterial evolution [

23].

Phage adsorption rates [

6,

13,

24,

25,

26,

27] and virion resistance to decay [

28,

29,

30] both contribute as well to phage life cycles, including to virion survivability. Those phage life-history traits, along with burst size, determine what also can be described as a phage’s basic reproductive number or, more or less equivalently [

12], their “effective” burst size [

22,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Phage host range [

17,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], as another key organismal-level phenotype of phages, also encompasses at least three of these phage growth parameters. These are (1) latent period length, which must be finite in duration; (2) burst size, which must be greater than one; and (3) adsorption rates, which must be greater than zero, all for a phage’s host range to encompass a given bacterium.

Thus, if there is a desire to characterize the most basic phenotypic aspects of either a phage isolate or instead of a laboratory modified version of a phage, then much can be surmised from OSG curves. The key to better determining these crucial characteristics, however, is to perform characterization assays correctly, and that of course includes OSG experiments, as is our emphasis here. Though seemingly simple in concept, such OSG ‘correctness’ is not necessarily as easily accomplished as one might imagine. Indeed, our experience with both submitted and published manuscripts suggests that OSG determinations can often leave substantial room for improvement. Improved OSG determination nonetheless should allow better appreciation of phage abilities to amplify their numbers, survive as replicating populations, and impact targeted bacteria ecologically, evolutionarily, and therapeutically.

Here we present various considerations on both how to and how not to perform these very basic phage-characterization experiments. For specific, more-detailed protocols, see for example Hyman and Abedon [

35] and Kropinski [

7], plus [

1,

4,

5,

42] as well as the methods provided here in the following section (2.3) and in

Section 4. See

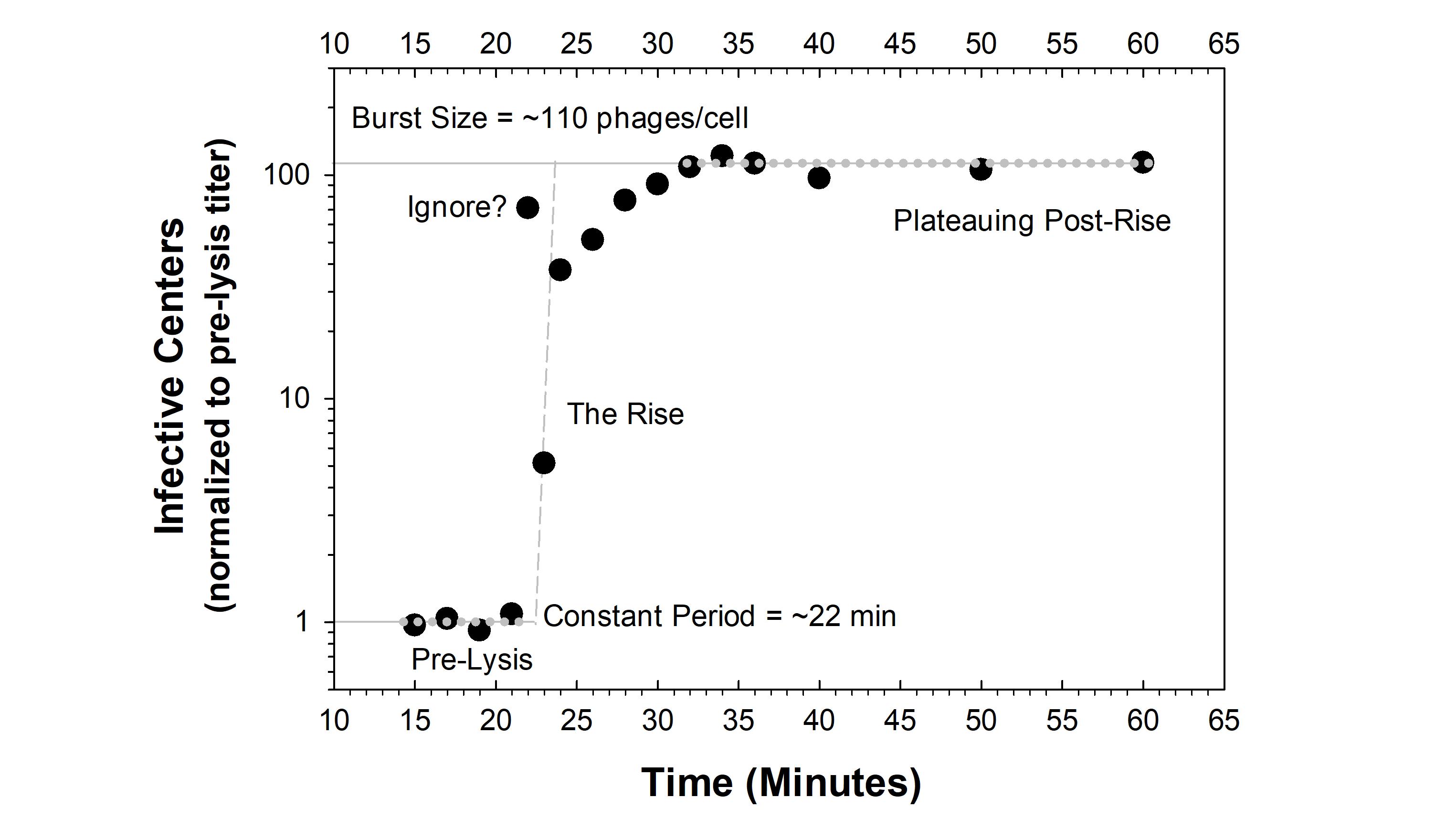

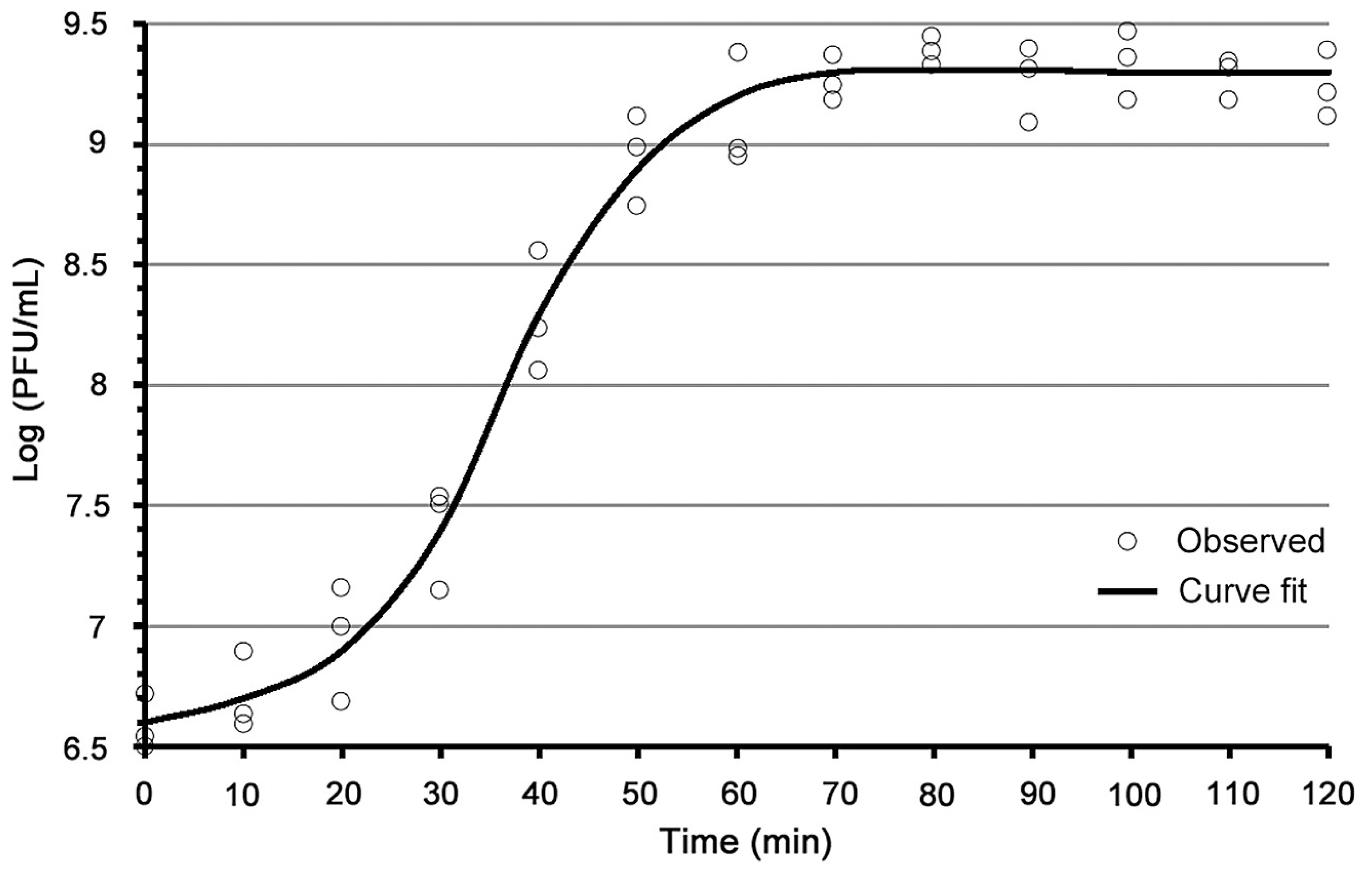

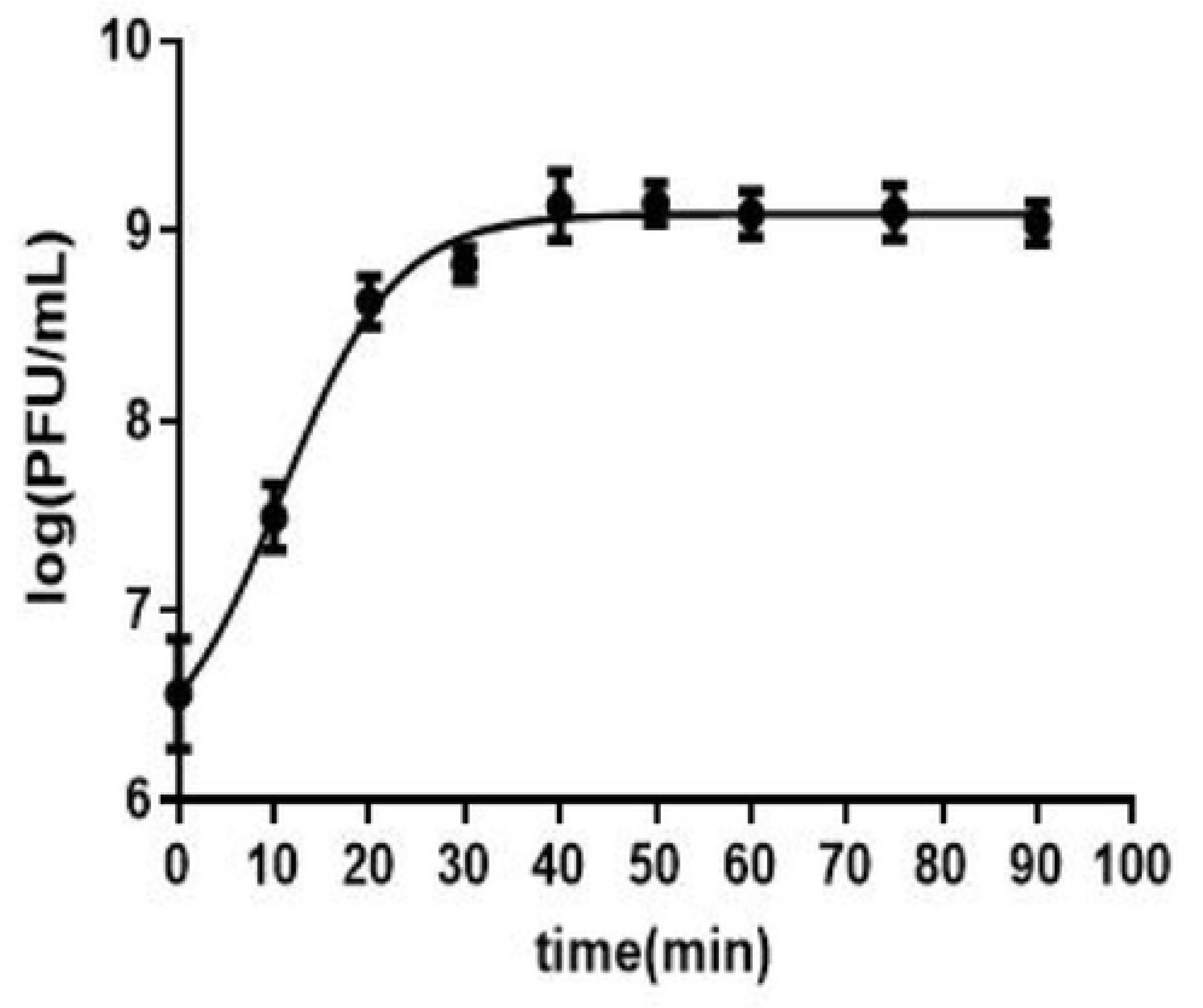

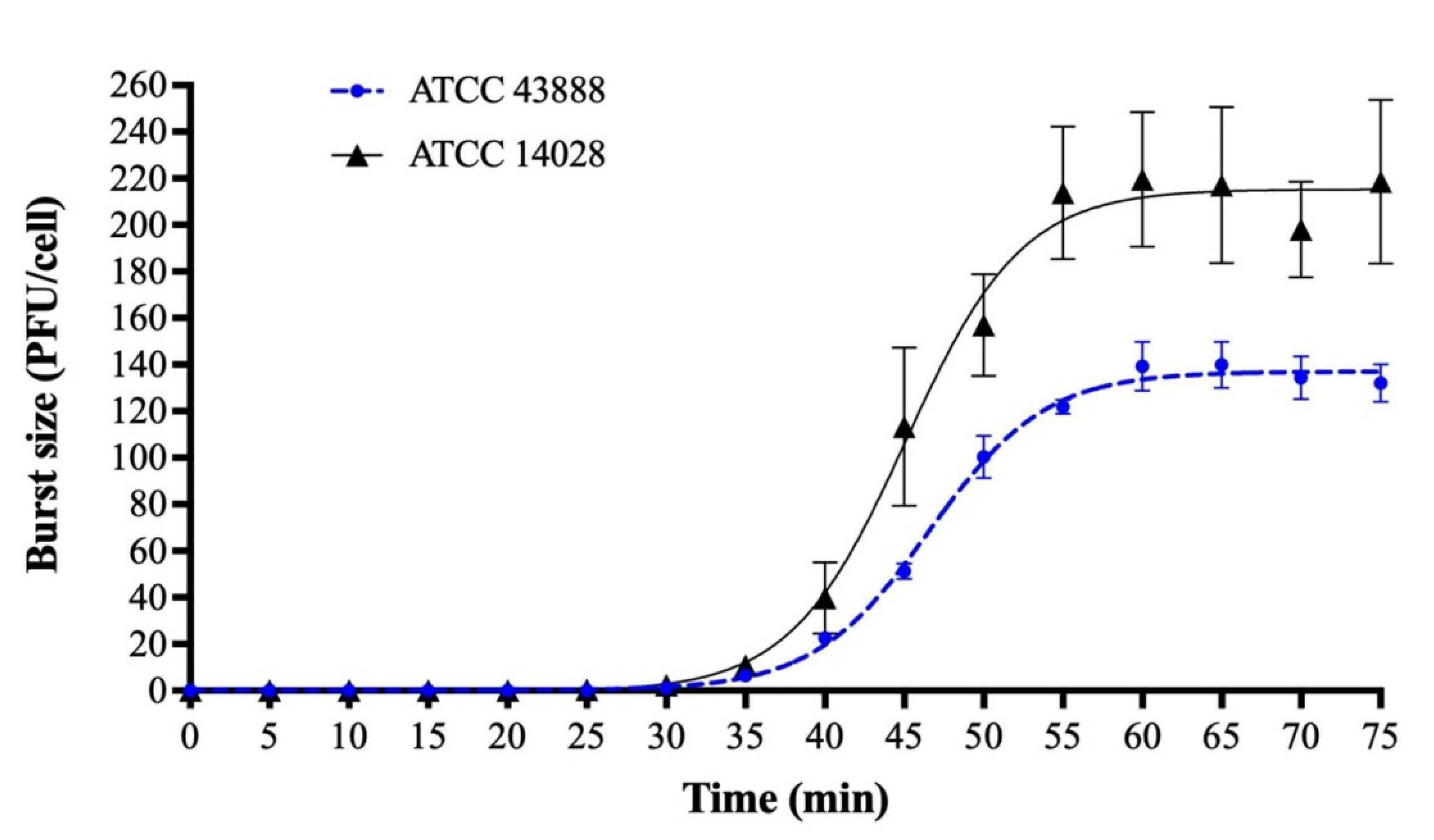

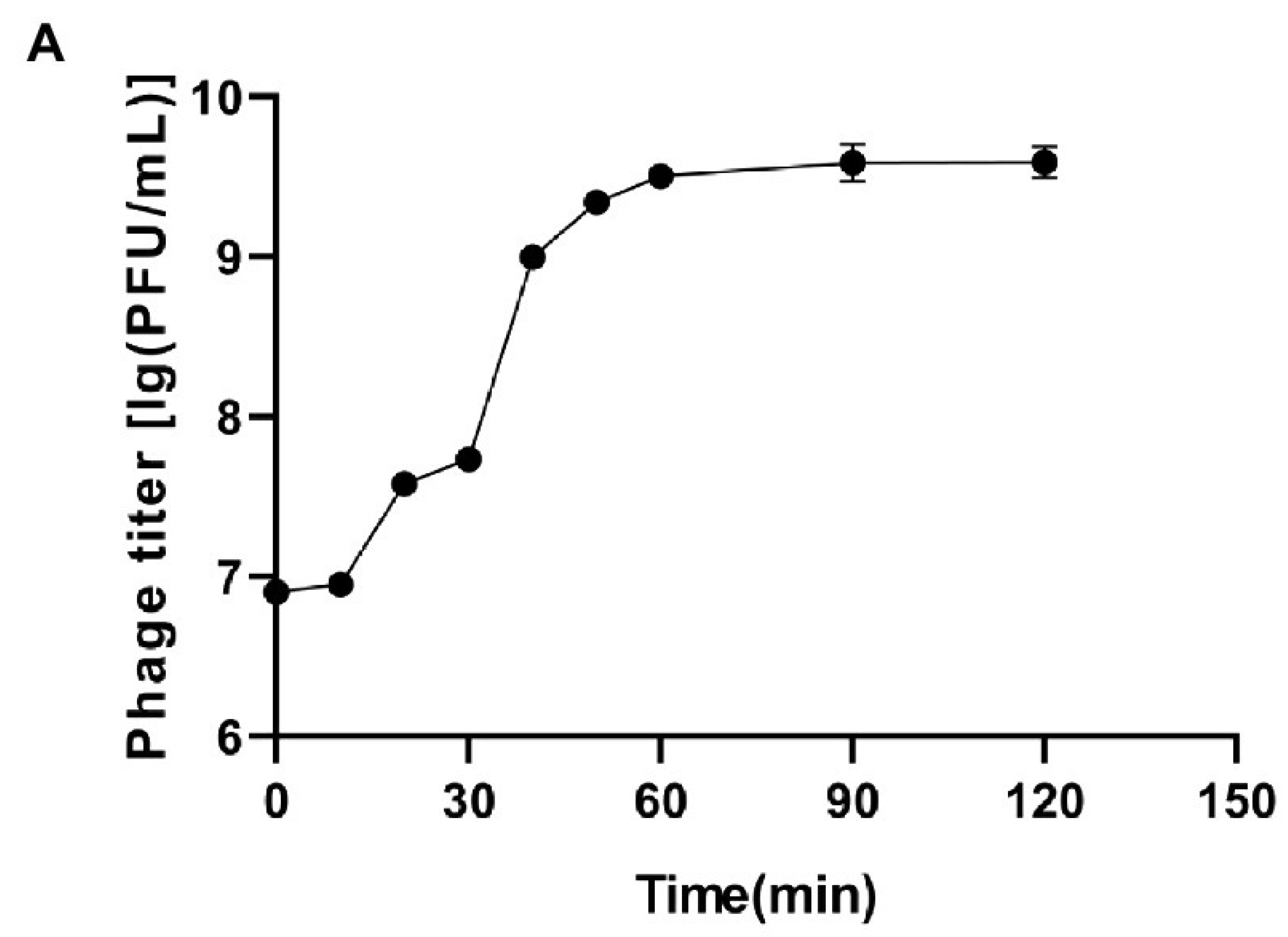

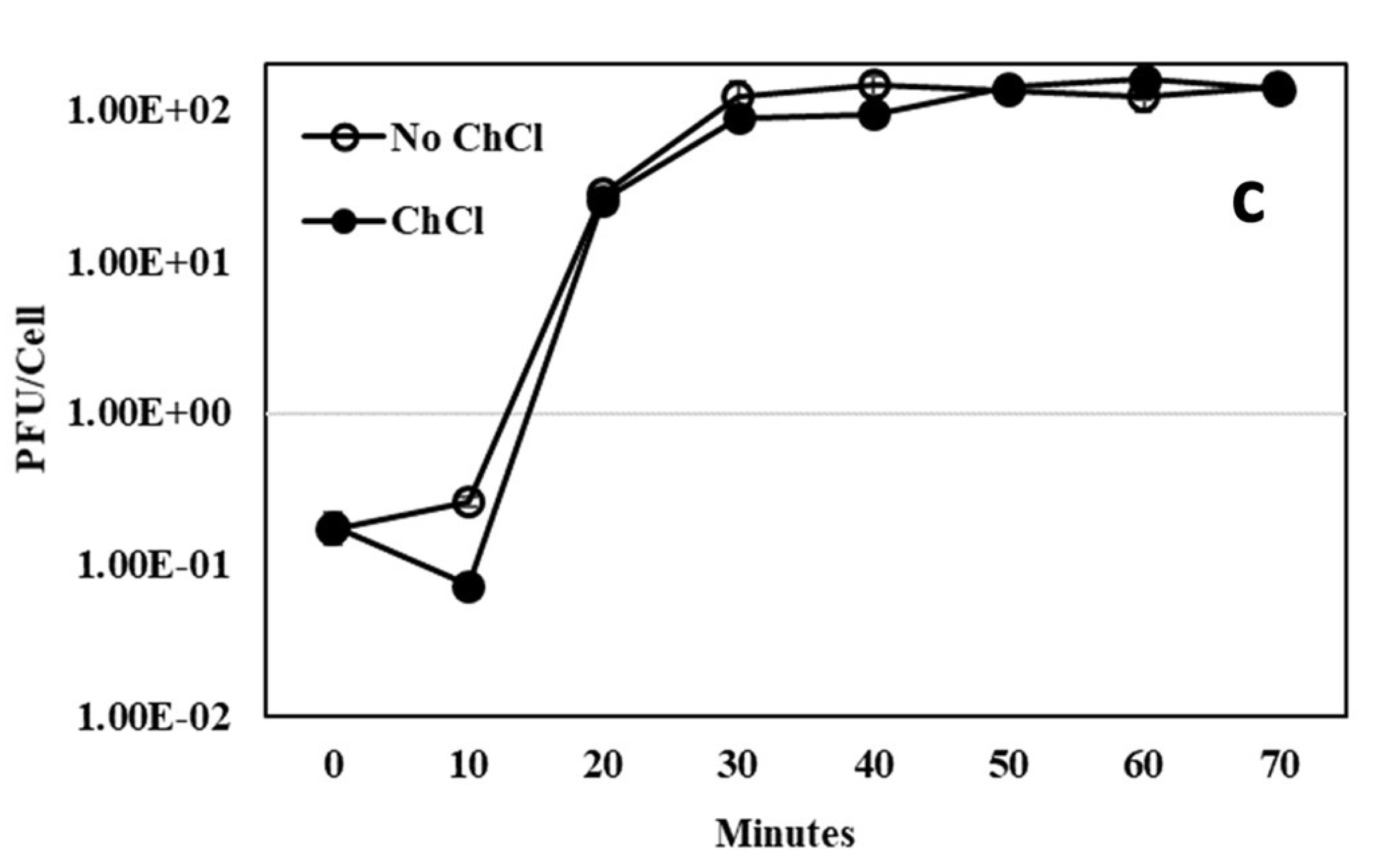

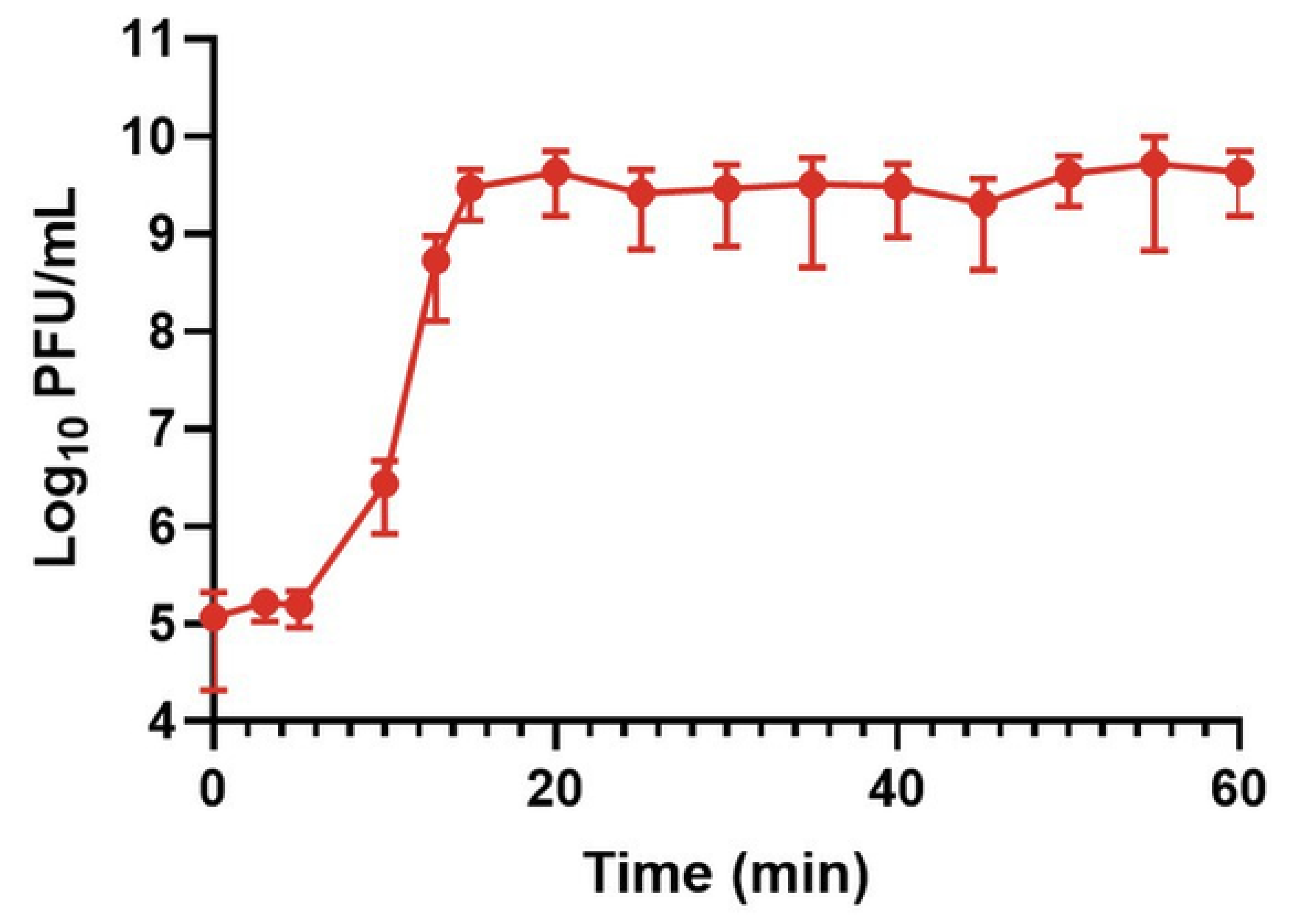

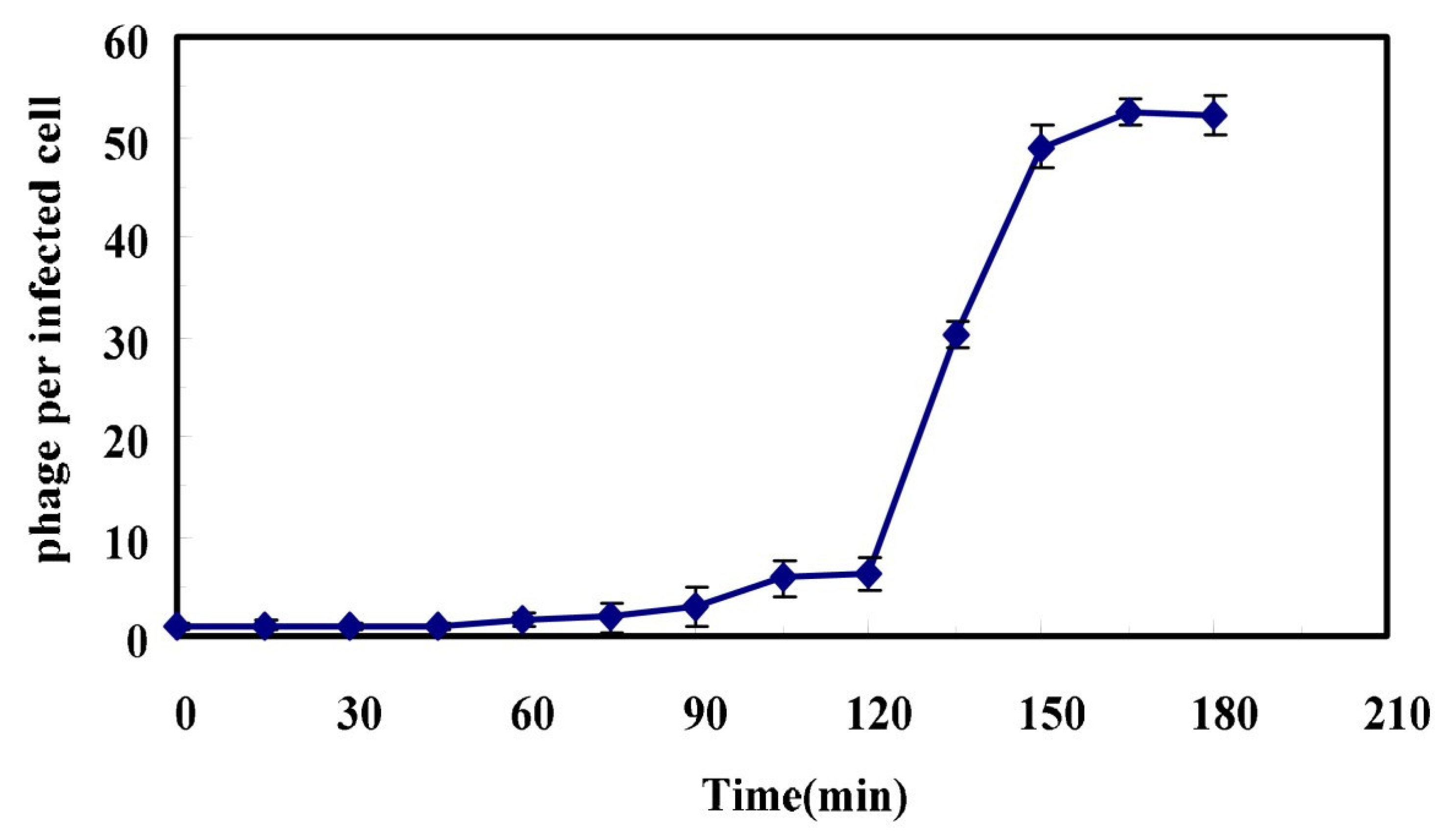

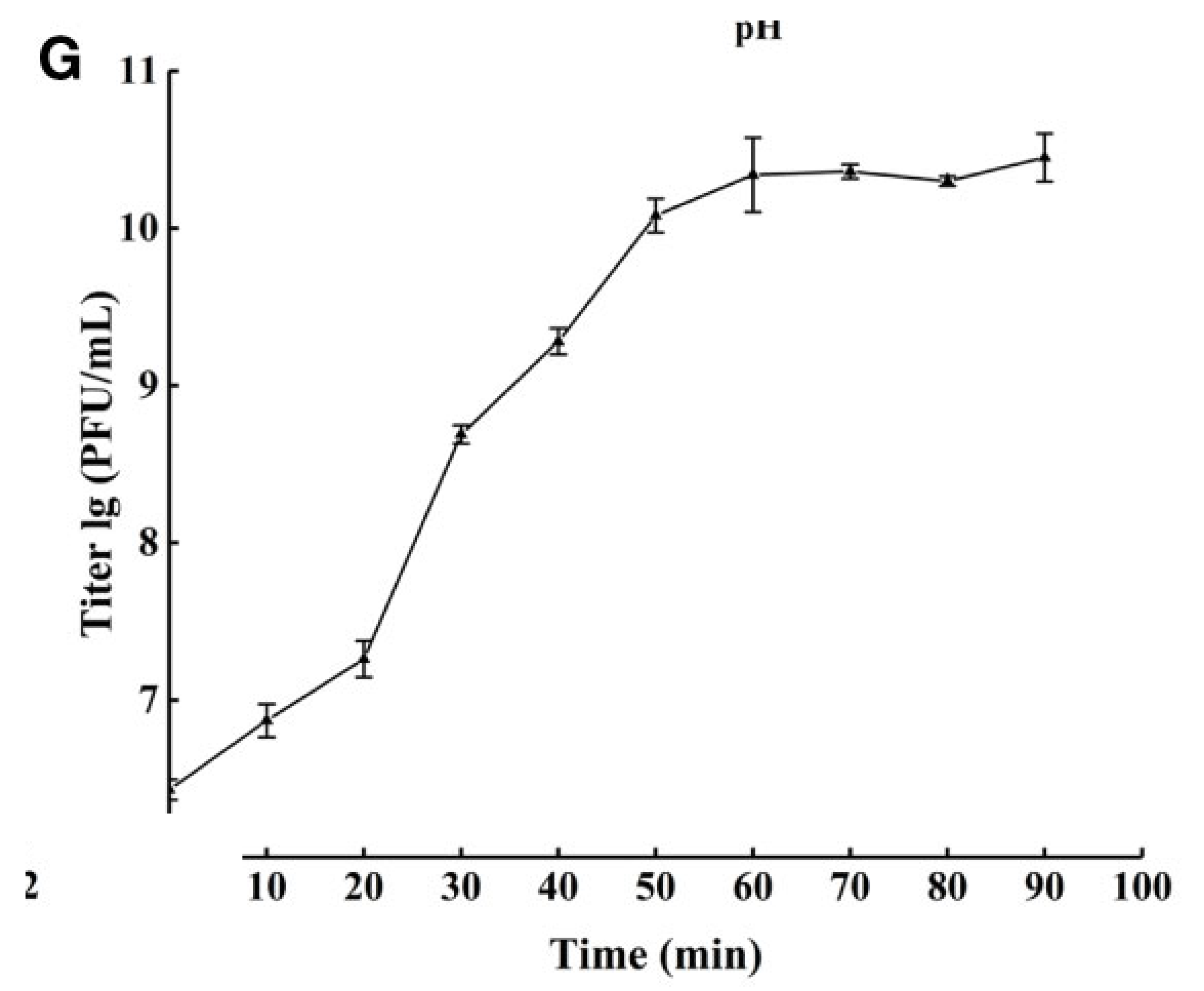

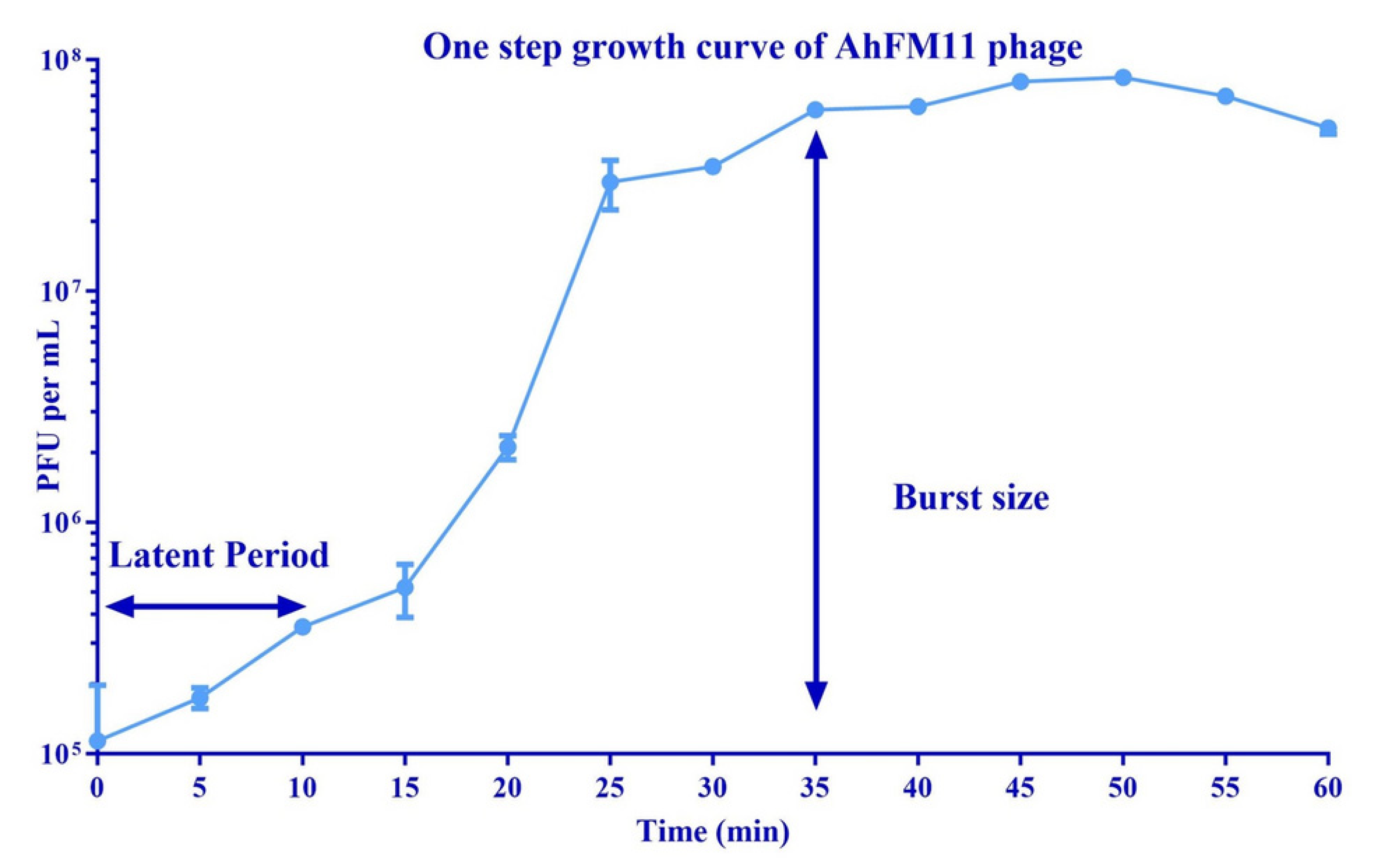

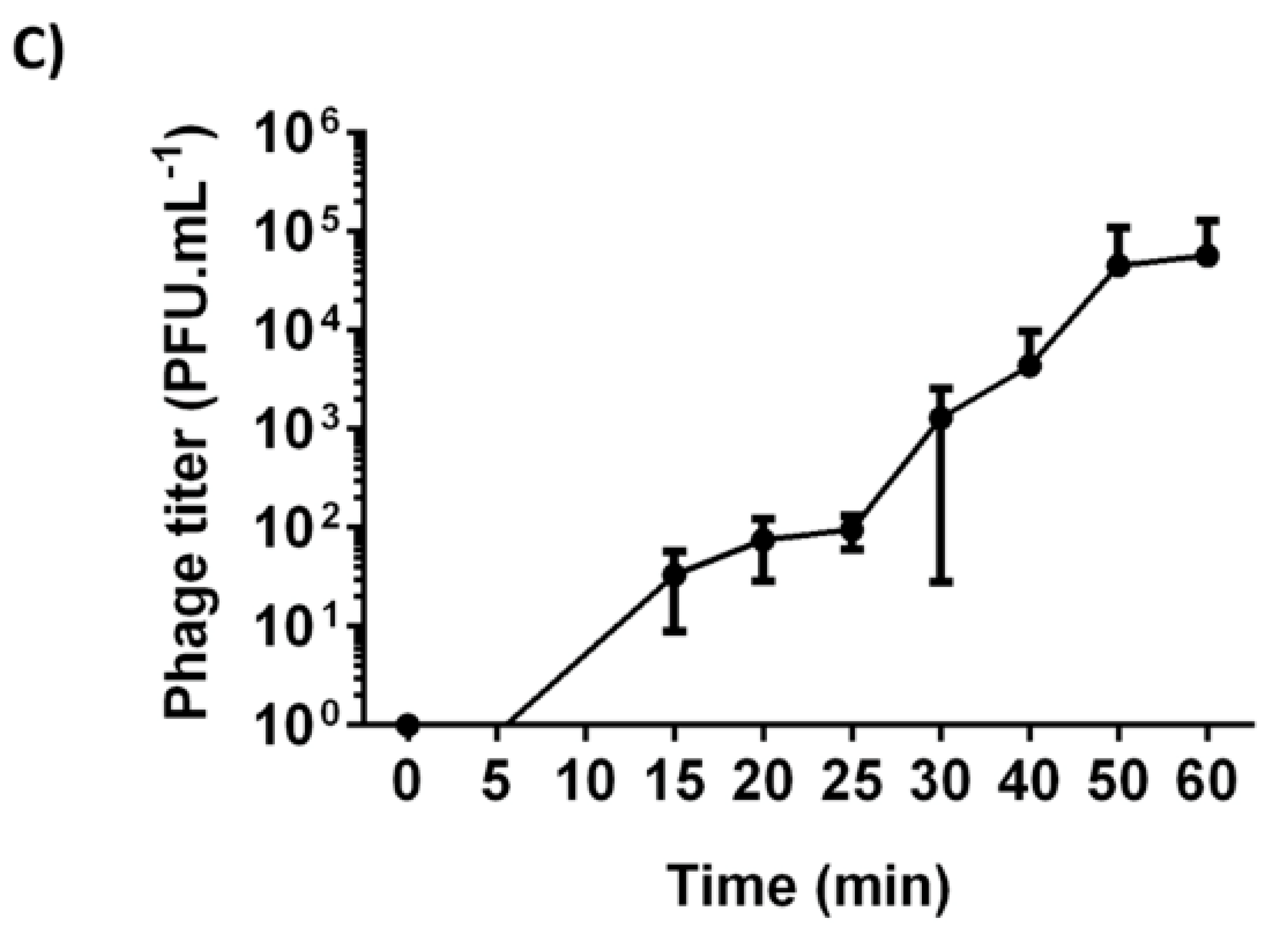

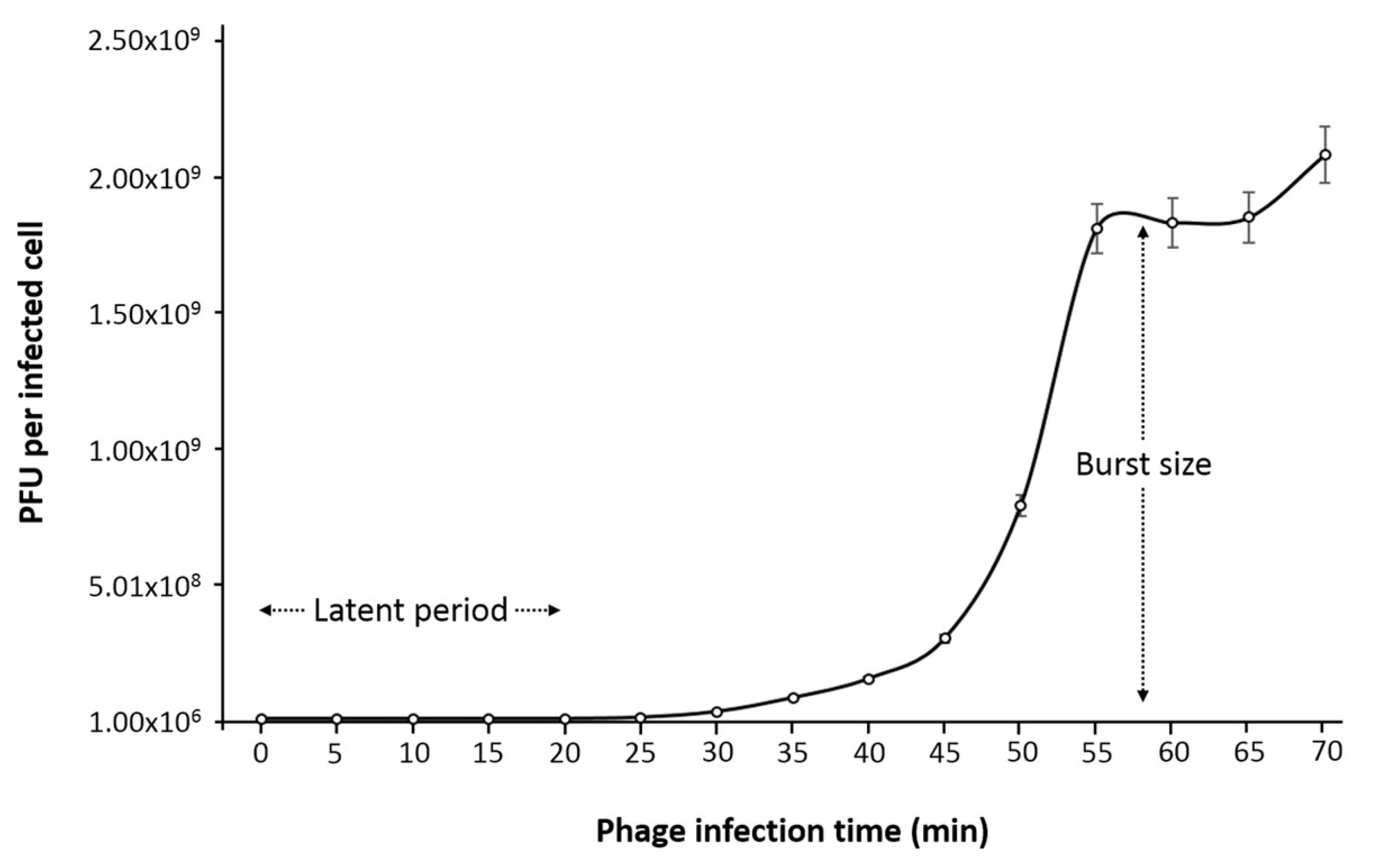

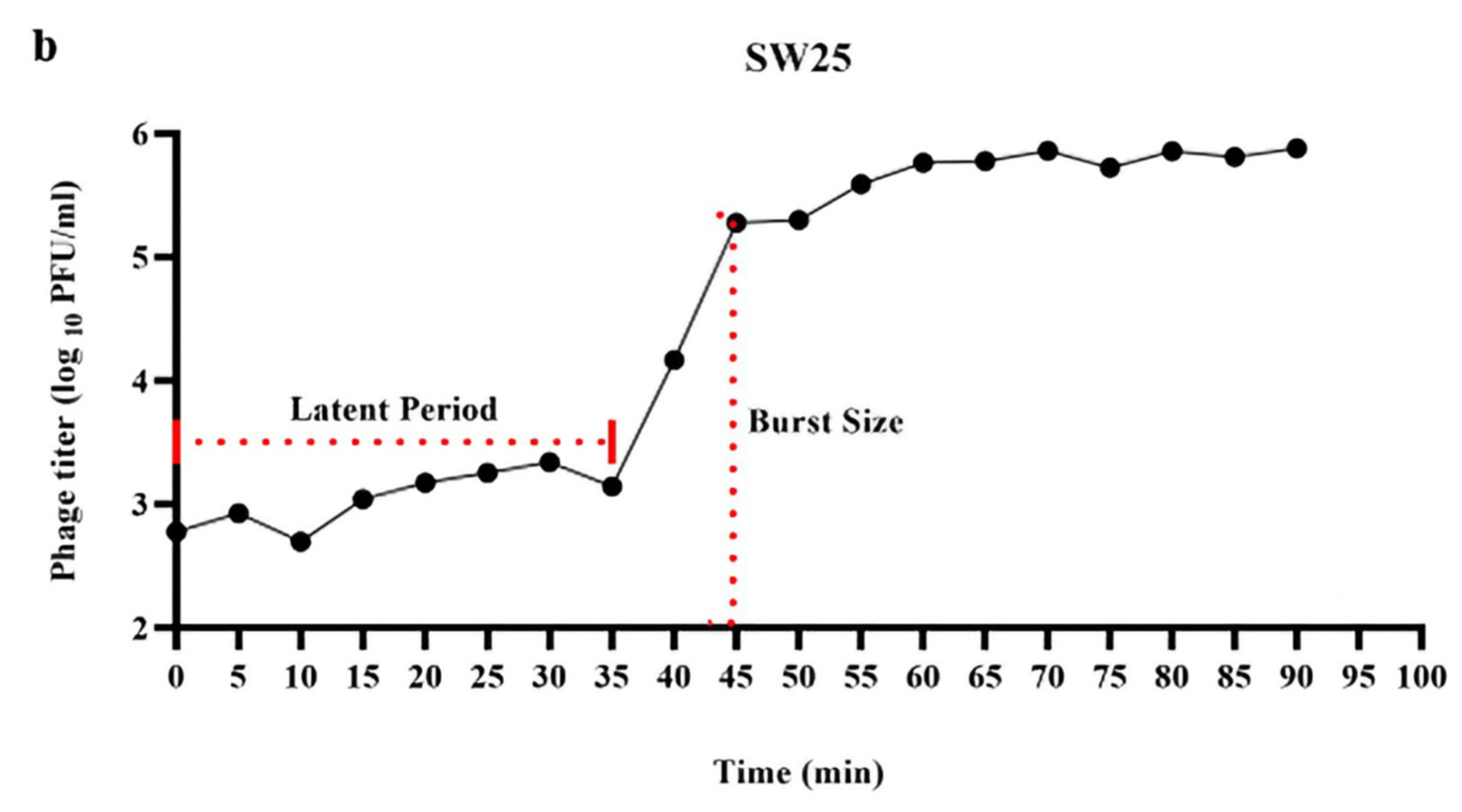

Figure 1 and

Appendix A for a number of examples of OSG curves obtained from the Creative Commons literature along with extensive critiques of those experiments and their presentation. See

Table 1 for definitions.

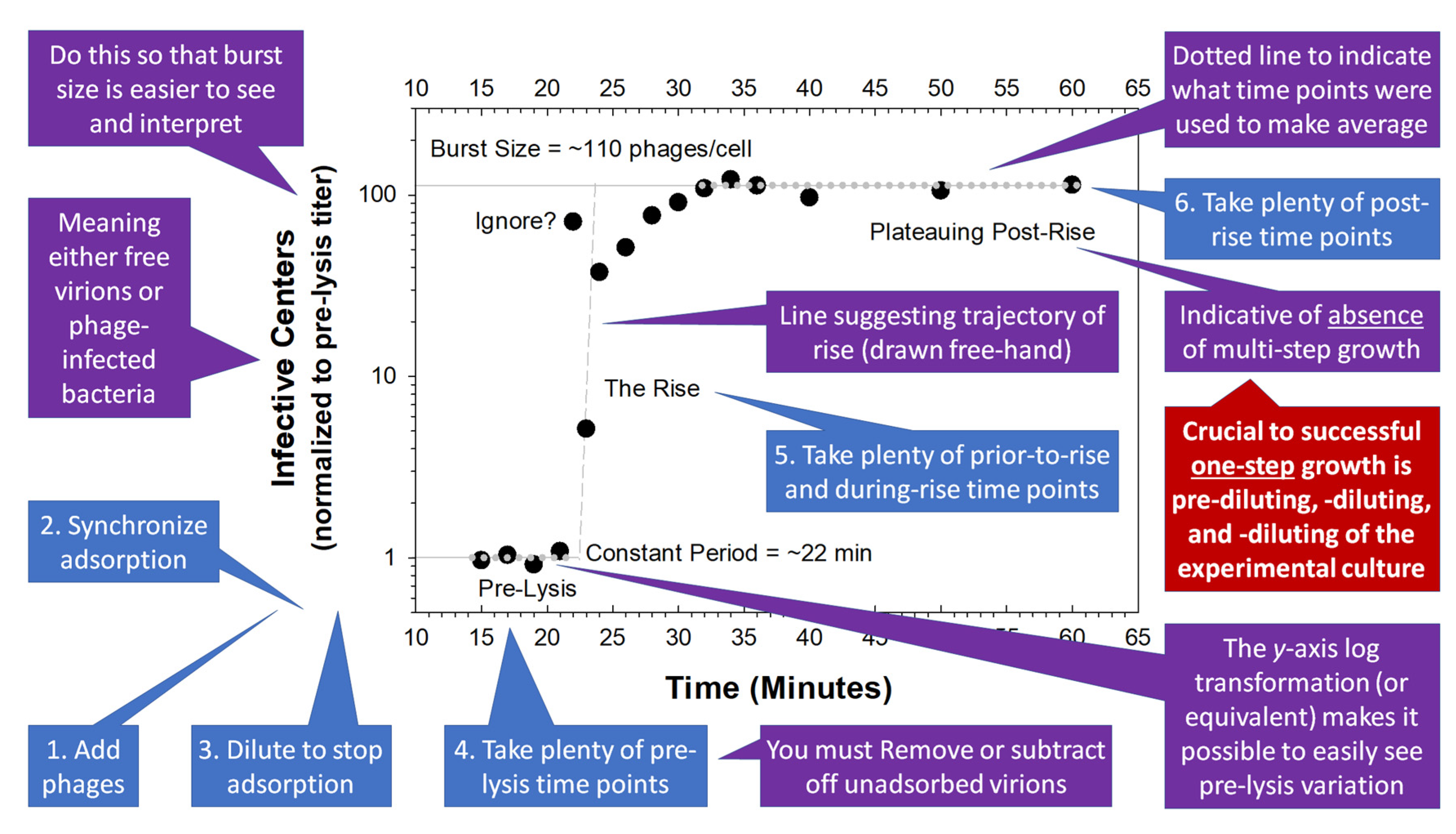

3. One-Step Dos and Don’ts

In this section, we provide guidance toward improving the execution of OSG experiments. We do this in a narrative form rather than providing as a series of explicit OSG “dos” and “don’ts”, which are found instead in

Section 2.4, immediately above. Major headings correspond to “Experimental Setup” (

Section 3.1), “Phage adsorption” (

Section 3.2), “Post-adsorption, prior to lysis” (

Section 3.3), “During lysis (the rise)” (

Section 3.4), and “After lysis” (

Section 3.5). We then provide a sub-section titled, “What data are important” (

Section 3.6). See

Figure 2 for a summary of some of the concepts considered in this section. In

Box 1, we also present a published, though here anonymous, example of what sorts of things often can be improved upon during experimental one-step growth.

3.1. Experimental Setup

Discussed in this section are suggestions to consider implementing prior to the start of experiments.

3.1.1. Use Log Phase Experimental Bacteria

Two distinguishable bacterial cultures are used in one-step growth experiments, the experimental culture and the indicator bacteria. The latter are used to support phage plaquing. Considering just the experimental bacteria, the goal should be, with OSG, for those bacteria to display the physiology that one is interested in for phage characterization. Typically this would be mid-log phase. Generally, unless that is one’s specific interest, it should not be lag phase experimental bacteria that are used, meaning don’t just add overnight cultures to fresh media and then, after some only short span of time, start experiments (as was possibly done in the OSG assays discussed in

Box 1).

Kropinski [

7] suggests simply growing bacteria to mid-log phase and then, presumably, immediately starting the experiment, using that bacterial culture directly while continuing to incubate it at the same temperature it was grown at, including starting with a pre-warmed experimental flask. It is certainly permissible to explore different bacterial physiologies over the course of a series of OSG experiments, if that is one’s intention. Just make sure that bacterial physiologies are consistent both during individual experiments and from day to day. It is also permissible to use different types of broth to grow bacteria to log phase, e.g., Hadas et al. [

45], such as for comparison between different growth conditions or instead to better mimic conditions found in situ.

Box 1. Example of a Problematic One-Step Growth Protocol.

In a recent, 2025, article – published in a reasonably noteworthy journal (impact factor ≈ 3) but which we otherwise are not citing for reasons of anonymity – two OSG curves are presented in which we have identified a number of errors. It is noteworthy, however, that these authors did separate unadsorbed virions from phage-infected bacteria (Section 3.3.2 and 3.5.4.1), as actually is fairly often done, but the experiment otherwise seems to possess the following issues:

The experiment was initiated with stationary phase bacteria (“an overnight host”;

Section 3.1.1).

The experimental bacterial culture, at least as indicated, was not diluted during the experiment (

Section 3.3.4), except that bacteria were suspended in fresh broth following phage adsorption and removal of free phages via centrifugation.

Prior to the start of lysis, the number of infective centers rises somewhat, perhaps as we speculate due to phage infections of initially metabolizing stationary phase bacteria being detrimentally affected by the plating process.

Five-minute time points were used throughout the experiment, including during the rise, resulting in only a single time point definitely capturing the lysis event (

Section 3.4.2 and

Section 3.4.4).

Latent period is defined as the last pre-lysis time point, though in one case whether it is prior to or following that time point is ambiguous and in both cases, with five-minute time points it is difficult to say whether the start of lysis actually occurred at the indicated time point or instead occurred a few minutes later (

Section 3.4.5).

The burst size, at least diagrammatically, is defined as the first time point at which titers seem to start to stabilize, possibly post-lysis, rather than involving multiple post-lysis time points (

Sections 3.4.4 and 3.5.5?).

It is difficult for the reader to determine which time points were used to define the post-lysis phage titer in burst-size calculations.

Phage titers are graphed as seemingly arbitrary values in absolute terms, i.e., starting around 103 PFU/ml. What do these titer values mean?

Ideally these values would have been normalized to the pre-lysis phage titers in the presented figure (

Section 3.5.3).

This latter titer increase is only slight (point 10), though has been visually minimized in the figure by having the curve graphed using a log-transformed

y axis. This, log-transformation of the

y axis, indeed is something that we recommend (

Section 3.4.5,

Section 3.6.1, and

Section 3.6.2), but which also for some aspects of figures can be obscuring, such as in this case of the ongoing increase in titers following lysis. Nonetheless, such an increase is inconsistent with the lack of pre-lysis diluting, which ought to give rise to more robust multi-step growth. That is, given the speculated lack of diluting, we would expect a greater post-rise ongoing increase in phage titers than we actually observe.

We have two possible explanations for that contradiction. First, perhaps the authors did in fact dilute, which is supported by their having taken more time points throughout the experiment than they seemingly had volume – as indicated in the methods – to take from. The one-step protocol they cite, however, also does not describe diluting, and also shows a somewhat consistently increasing titer between 20 and 130 or so minutes. The protocol this cited article cites in turn cuts off the experiment prior to the time of any ongoing increase in phage titer might have occurred. The second possibility is that multi-step growth was occurring, but that it was not robust due to the OSG experiment taking place using high, overnight-culture concentrations of bacteria. The bacteria thus were presumably able to use up the nutrients available in the added broth fairly quickly, particularly after entering into a lag phase, resulting in some but not much post-rise titer increase.

Overall, our opinion from this analysis is that this OSG curve, as well as the one these authors directly cite, is sufficiently flawed to be insufficiently useful toward either latent period or burst size determination. It is because of the existence of such OSG efforts and others (

Appendix A) that we have undertaken the effort provided here.

3.1.2. Start with a Reasonably Fresh Phage Stock

To the extent that phage infection characteristics do not change during storage, then this second consideration may be ignored. Nevertheless, for the sake of consistency from experiment to experiment, or from laboratory to laboratory, it can be useful to define a specific phage stock age as standard, with freshly generated, e.g., not multiple years old, a reasonable standard. Particularly important is to avoid using phage stocks whose killing titers [

46] greatly exceed numbers of PFUs. That is, it is helpful for numbers of adsorbing phages to be similar to numbers of viable phages, so as to avoid varying multiplicities of adsorption between phage stocks (this more generally is an issue of low phage efficiency of plating, as considered in the following section, 3.1.3). Note also that virions can potentially aggregate over time during storage, but which can disaggregate over the course of incubation at, e.g., 37°C [

47].

It is important regardless to make sure that a phage stock’s titer has been determined reasonably recently prior to OSG, since starting titers and multiplicities of infection (MOIs) are important for the mechanics of OSG determinations. Ideally, that is, it will be possible to anticipate how many plaques will be found on plates, particularly prior to OSG lysis. For more on MOIs, see [

48,

49,

50]. Considered in the following section (3.1.3) is why avoiding unexpectedly high MOIs can matter when performing OSG experiments.

3.1.3. Taking into Account Phage Efficiency of Plating

Related to the above idea that phage plating titers (PFUs) and phage killing titers ideally should be similar – the latter being numbers of phages calculated in terms of their abilities to kill bacteria rather than their abilities to form plaques [

46] – is an issue of phage efficiency of plating (EOP) [

1,

4,

43,

44]. Phages whose killing titers exceed their plating titers will have EOPs of less than one, at least in terms of absolute efficiency of plating [

1,

4]; that is, more phages able to adsorb and kill than are able to form plaques. Low EOPs could be present perhaps especially if stationary phase rather than log phase indicator bacteria are used for titering of phage stocks (

Section 3.4.1).

If EOP is low, then the result will be starting phage multiplicities that, in terms of phage adsorptions, are greater than anticipated based on PFU counts alone. Though in practice this issue is perhaps almost never considered when performing OSG experiments, it still could be relevant. It therefore should not be completely ignored, and this is so especially if the phage being characterized is able to display lysis inhibition.

Lysis inhibition is a multiple phage adsorption-induced extension of the phage latent period, resulting also in an increase in the phage burst size [

51]. In particular, a phage displaying a low EOP on the titering host, and which also displays lysis inhibition, could register unexpectedly long single-step latent periods as well as larger burst sizes, due to excessive phage adsorption. Indeed, an important reason that OSG experiments are initiated with MOIs of somewhat less than one is to avoid induction of lysis inhibition. We discuss in

Section 3.4.1 another way that this issue of low EOPs can be relevant during OSG experiments.

3.1.4. Start with Fresh Indicator Bacteria

At a minimum, indicator bacteria should be reasonably consistent in terms of ability to support phage plaquing, going from experiment to experiment as well as over the course of individual experiments, the latter point considering especially EOPs for free phages vs. phage-infected bacteria. Thus, as a general rule, indicator bacteria, i.e., plating culture, should be made up fresh for individual OSG experiments. The properties of indicator bacteria are considered further in

Section 3.4.1.

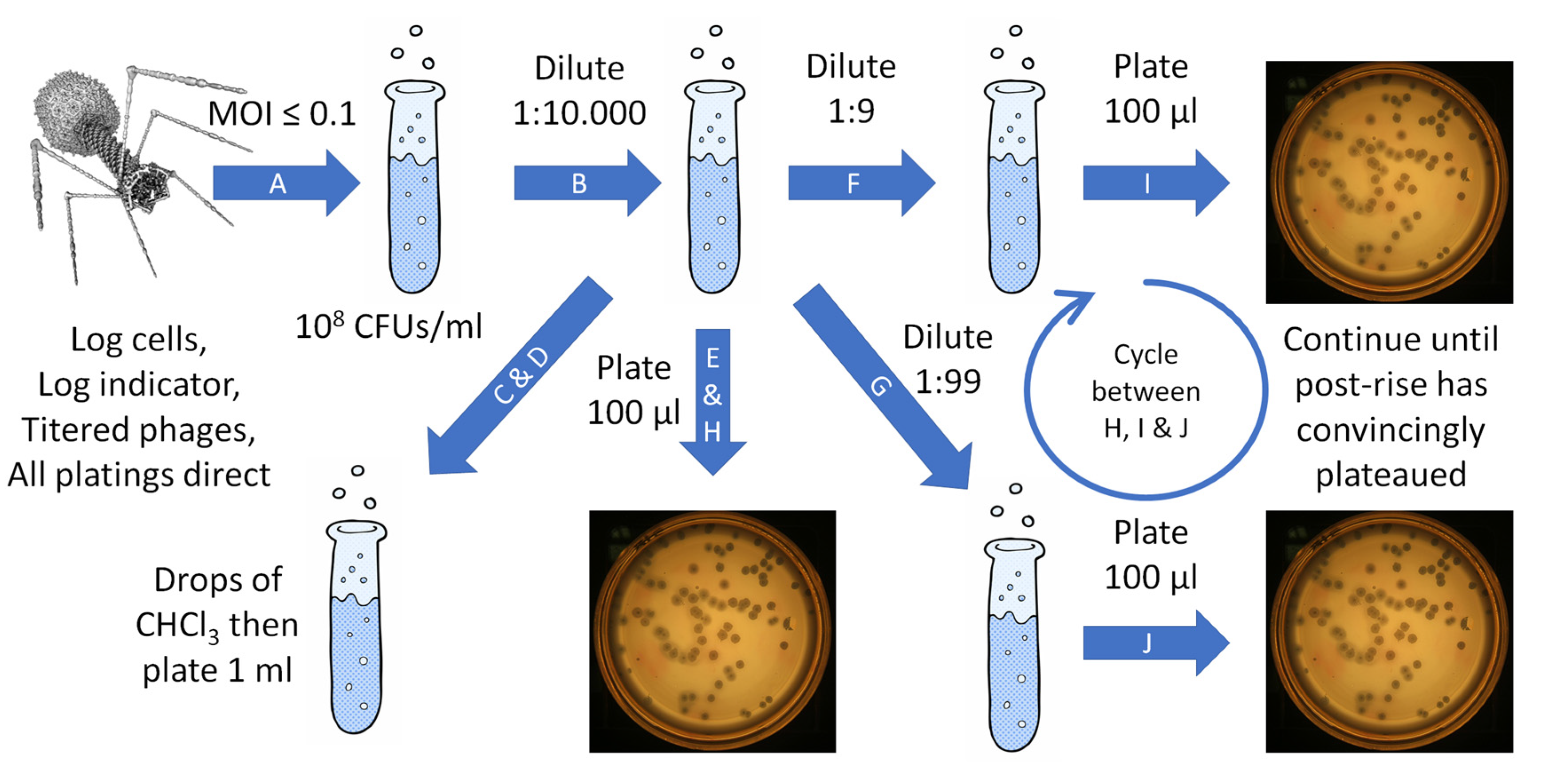

3.2. Phage Adsorption: A Time for Synchronization

The phage adsorption step during OSG involves adding phage virions to experimental, broth bacterial cultures and then, waiting. Ideally, this wait will be over after a relatively short interval (see “Synchronization…”,

Section 3.2.3). For instance, Kropinski [

7], p. 41, notes that OSG experiments are “based upon the assumption that 90–95% of the phages adsorb to the host cells within 5 min” Generally, the adsorption interval is terminated – at a minimum – by a substantial dilution of the experimental culture. Consequently, this necessary culture dilution, particularly step iii in

Section 2.3, should not come too soon after phage addition to bacteria (minutes later rather than seconds later). As noted above (

Section 2.3), this OSG-essential dilution step often appears to be missing from published OSG experiments. As a general rule, if there is no dilution of experimental bacterial cultures, then there is no

one-step growth. See

Section 3.5.1 for more on multi-step phage growth.

3.2.1. Use a Sufficient Concentration of Experimental Bacteria

It is bacterial concentrations that determine the rate at which individual phages adsorb, which is what is of concern at the start of OSG. This actually is the opposite of the concern with phage therapy, where instead it is the rate at which individual bacteria are adsorbed by that is relevant rather than explicitly how fast individual phages are adsorbing [

52]. From Adams [

1], p. 14, “1. Phage and bacteria are mixed at [bacterial] concentrations that permit rapid adsorption.” That statement, however, is complicated by the fact that having too concentrated a bacterial culture can result in undesired changes in bacterial physiology. Thus, more properly stated, one should be using experimental bacterial cultures that are sufficiently concentrated to allow for rapid phage adsorption, but not necessarily so concentrated that this impacts bacterial physiologies in undesired ways.

As indicated by Ellis and Delbrück [

2], initial bacterial concentrations in the range of 10

8 per ml should be targeted, while Adams [

1] instead suggests 5 × 10

7 CFUs/ml. Keep in mind, however, that numbers of individual bacteria and numbers of colony-forming units (CFUs) are not necessarily identical. Note also that it should be possible to concentrate bacteria, if need be, prior to the phage adsorption step, such as concentration via centrifugation. This too, though, should be done in such a way that does not inappropriately impact bacterial physiological states. That is, the reason one does OSG experiments is to assess phage infection during growth on bacteria of a reasonably well defined physiology, so some thought and effort should go into retaining that physiology. In addition, handling of experimental bacteria certainly should be consistent from experiment to experiment.

3.2.2. Use an Appropriate MOI

As originally conceived, as well as subsequently developed, OSG experiments were intended to characterize not just a single round of phage infection but also to have that single round be dominated by infected bacteria that have been adsorbed by only a single phage, though Ellis and Delbrück [

2] did explore as well multiple virion adsorption. Adsorption of every bacterium by only a single phage, under most circumstances, is however not possible to achieve absolutely across a bacterial population, and this is due to Poissonal distributions of virion adsorptions over targeted bacteria [

5,

49,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. Nevertheless, singly infected bacteria can substantially predominate in cultures if starting MOIs are sufficiently low. Thus, an MOI of 1 will result in an anticipated 42% of phage-infected bacteria present having been adsorbed by more than one virion (of 63% of bacteria which in total are phage adsorbed, i.e., 1 - e

-1, multiplied by 100 to make the value a percentage). Dropping the MOI to 0.1, however, reduces that percentage to only 5%. Specifically, in Microsoft Excel, use the formula, “=100*(1-(POISSON.DIST(1,

n,FALSE)/(1-POISSON.DIST(0,

n,FALSE))))”, where

n is equal to the realized multiplicity of infection, i.e., an MOI

actual such as 0.1.

Note that if attempting to perform OSG experiments using multiplicities of greater than one, then one has to be certain that CFUs consist of individual cells. The goal in other words should be to define phage multiplicities of infection explicitly as phages per cell rather than phages per CFU. If that is not the case, that is, if CFUs consist of more than one bacterium linked together (a cellular arrangement or bacterial microcolony), then one risks having individual infective centers consisting of more than one phage-infected bacterium. That in turn will have the effect of artificially increasing calculated burst sizes as well as result in multi-step growth—more phages produced per phage-infected CFU as MOIs are increased, but not necessarily also more phages produced per phage-infected bacterium, and with this phage production taking place over multiple phage latent periods. For possible evidence of this effect, see in particular the results of Gadagkar and Gopinathan [

57], as discussed by Abedon and Thomas-Abedon [

32]. An example of use of an MOI of greater than 1 can be seen in Figure 0045249 (

Appendix A).

It nonetheless certainly is permissible to explicitly study the infection characteristics of multiply phage-infected bacteria. Regardless of what MOI is used, though, just make sure when adding phages that bacterial cultures do not become excessively diluted with phage buffer, as that would have the effect of possibly modifying experimental conditions to the detriment of accurate latent period and burst size determination.

3.2.3. Synchronization of Adsorption

OSG provides a description of population averages of phage characteristics rather than single-cell precision. It is possible alternatively to study single-cell lysis timing [

58] or single-cell productivity (single burst experiment) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

59], but these are more complicated to do. Nonetheless, OSG precision

can be increased. One way to accomplish this, particularly for latent period determinations, is by taking sufficient numbers of time points, particularly at crucial times (

Section 3.4.2 and

Section 3.4.5). Synchronization of phage adsorption, however, is also important toward increasing that precision. From Adams [

1], p. 441, “One-step growth of phage: A single cycle of infection and lysis,

nearly synchronous in all the infected bacteria of the culture…” Specifically, the closer one can get to physiologically starting all phage infections at the same time, then the shorter the duration of the rise and the closer the rise is to describing the distribution of lysis timing across infections, vs. also the distribution of adsorptions.

Failure to employ one or more strategies toward synchronizing adsorption will result in artificially long rise periods due to more drawn-out adsorption. This is less of an issue if latent period is defined as the start of the rise rather than, e.g., its middle, and if the duration of the rise is not otherwise considered to be relevant to assay success. Excessively slow virion adsorption relative to the start of bacterial metabolism could, however, impact determinations of minimum latent periods, i.e., by delaying the beginnings of virion release. Thus, at a minimum, it is best to start with sufficient numbers of bacteria (

Section 3.1.2), and then to halt adsorption relatively soon, particularly a few minutes after it has begun. Adams [

1] used, for example, 5 minutes for pre-dilution phage adsorption, though noted that this may need to be longer for slowly adsorbing phages (see too Kropinski [

7]). Adams also cautioned (p. 477) that, “The adsorption time is limited by the necessity of completing the dilutions before the end of the latent period.” For OSG curves suggesting a lack of adsorption synchronization, see for example Figures 0045242 and 0045243 (

Appendix A).

3.2.4. Routes to Adsorption Synchronization

Synchronization of phage adsorption explicitly is in terms of phage-infection metabolism. That is, the goal is for as large a fraction of phages as possible to adsorb at something close to

t = 0 for the OSG experiment. There are multiple approaches, not necessarily all mutually exclusive, to achieving such adsorption synchronization. One is to start, as noted (

Section 2.2), not with virions at all but instead with bacterial lysogens that can be simultaneously induced (

Section 5.1). That approach, though, only works with temperate phages.

A second synchronization strategy is to dispense with infection metabolism altogether, by adsorbing to temporarily metabolically inhibited bacteria [

46]. This includes as can be accomplished by washing bacteria in media lacking in appropriate energy sources. A compromise is to simply slow bacterial metabolism by performing the adsorption step at a lower temperature, such as room temperature. The latter is an elaboration on Carlson’s [

46] suggestion that the entire experiment might be performed at a lower temperature (see too Kropinski [

7]), though if carried out over the entire OSG experiment that obviously would modify resulting phage growth parameter values, resulting, for example, in a lengthening of measured latent periods [

2]. Note, though, that Carlson [

5] cautions against such delays in plating as (p. 434) “chilling cells or using growth inhibitors… usually gives less reproducible results.” Kropinski [

7] similarly states, “We do not recommend chilling the phage-host mixture.”

A third and probably most-standard approach is to use both sufficient concentrations of bacteria and sufficiently permissive adsorption conditions that the adsorption process itself is rapid (

Section 3.1.2).

A fourth approach, also fairly standard and not mutually exclusive, is to stop adsorption after a relatively brief period of time. This can be done by either diluting bacteria (though with the issue that free phages will remain in the media), selectively killing free phages using virucides [

60], or using specific anti-virion serum [

3]. Alternatively, it is possible to physically separate free phages from bacteria as can be accomplished via centrifugation. Note if doing the latter that it is the supernatant that is discarded and the pellet that is kept; for a possible example where instead the pellet may have been discarded, at least in the course of titering, see Figure 0045249,

Appendix A. Adams [

1], p. 14, indicates this adsorption stopping process as, “2. After a suitable adsorption period the mixture is diluted into antiphage antibody to stop adsorption and inactivate unadsorbed phage.” Stent [

4] too suggests the use of antiphage serum, though more recent protocols have not.

3.3. Post-Adsorption, Prior to Lysis: The Phage Infection

Steps to be taken prior to the start of lysis, especially once adsorption has been stopped, include providing any additional necessary dilutions of the phage-infected bacteria and to plate for PFUs. Plating for PFUs requires that unadsorbed free phages be excluded from those counts. As noted above, it is the necessary dilution step that seems to be most-often missing from problematic OSG experiments.

3.3.1. Infective Centers

As noted, traditionally PFUs in the context of OSG were referred to not as PFUs but instead as infective centers [

1,

2,

4]. This was done so as to not distinguish explicitly between plaques initiated by free phages vs. plaques initiated instead by phage-infected bacteria. From Adams [

1], p. 440, “Infective center: A plaque-forming particle that may be either a productively infected bacterium or a free phage particle. When one or the other is meant, the term infective center should not be used.” We will use “Infective center” here as appropriate, but it can be interpreted as equivalent to PFU. Its use is relevant particularly in this section, however, since what is being enumerated, post-adsorption and prior to lysis, are plaque-forming units that consist (ideally) of just phage-infected bacteria rather than also unadsorbed virions.

3.3.2. Accounting for Free, Unadsorbed Phages

From Adams [

1], p. 15, “If unadsorbed phage were not inactivated the early plaque counts would include unadsorbed phage as well as infected bacteria and the estimate of the burst size would be too small.” The suggested use of anti-phage antibodies, or instead using virucides, or use of centrifugation (

Section 3.2.3), are all for the sake of eliminating free phages early during OSG experiments. More generally, however, these are approaches to achieving a broader aim, which is one of properly accounting for unadsorbed free phages, something which can also be achieved by assessing for free phages after the adsorption period.

Eliminating free phages such as by using anti-phage serum or virucides should be done prior to the initial plating for infective centers. If free-phage inactivation is used, though, then it is important to dilute away the inactivating agent subsequent to both plating for infective centers and the phage rise (for the latter, see

Section 3.4). It also is helpful to employ a free-phage assessment step (

Section 3.3.3) even when using the aforementioned virucides, etc. Assessing for remaining free phages should be done after cultures have been diluted rather than prior to diluting, as diluting serves as a means of lowering the concentrations of antibodies or virucides, if present, as well as serving as an alternative means of substantially reducing ongoing phage adsorption. Such plating for free phages, though, does not necessarily need to be done explicitly prior to plating for infective centers, as further phage adsorption during experiments, following diluting of the experimental culture, is unlikely. On the other hand, it is important to complete this assessment for free phages prior to the start of the rise. Given both culture dilution and plating for unadsorbed virions, explicit free phage inactivation to stop phage adsorption in most cases is not essential.

The goal in any case is to account for free, unadsorbed phages so as to make sure that their numbers are not included among the infective centers that are being enumerated prior to the start of lysis. Burst sizes, in other words, are determined by dividing numbers of free phages that are present post-lysis (specifically, post-rise) by numbers of phage-infected bacteria that are present prior to that lysis (

Section 3.5.4). Especially the latter, pre-lysis phage numbers, can be exaggerated by the presence of free phages, so those must in some manner be accounted for, i.e., subtracted off from total, pre-lysis number of PFUs. Numbers of post-rise free phages can be impacted as well by these numbers of initial, unadsorbed phages. That, however, is less of a problem [

61] unless phage adsorption has been particularly poor or burst sizes excessively small, i.e., since otherwise the impact of inclusion of those pre-lysis unadsorbed phages in counts of post-lysis phage numbers will tend to be trivial.

3.3.3. Assessing Unadsorbed Phages

Perhaps the easiest way to assess for unadsorbed virions is to use centrifugation to remove bacteria, including phage-infected bacteria, and then to titer the resulting supernatant [

1]. This should be done well prior to the start of lysis, however, so as to minimize the likelihood of inadvertently releasing free phages from infected bacteria. Alternatively, one can use chloroform to kill phage-infected bacteria while sparing free virions or instead can sonically disrupt bacteria toward the same end [

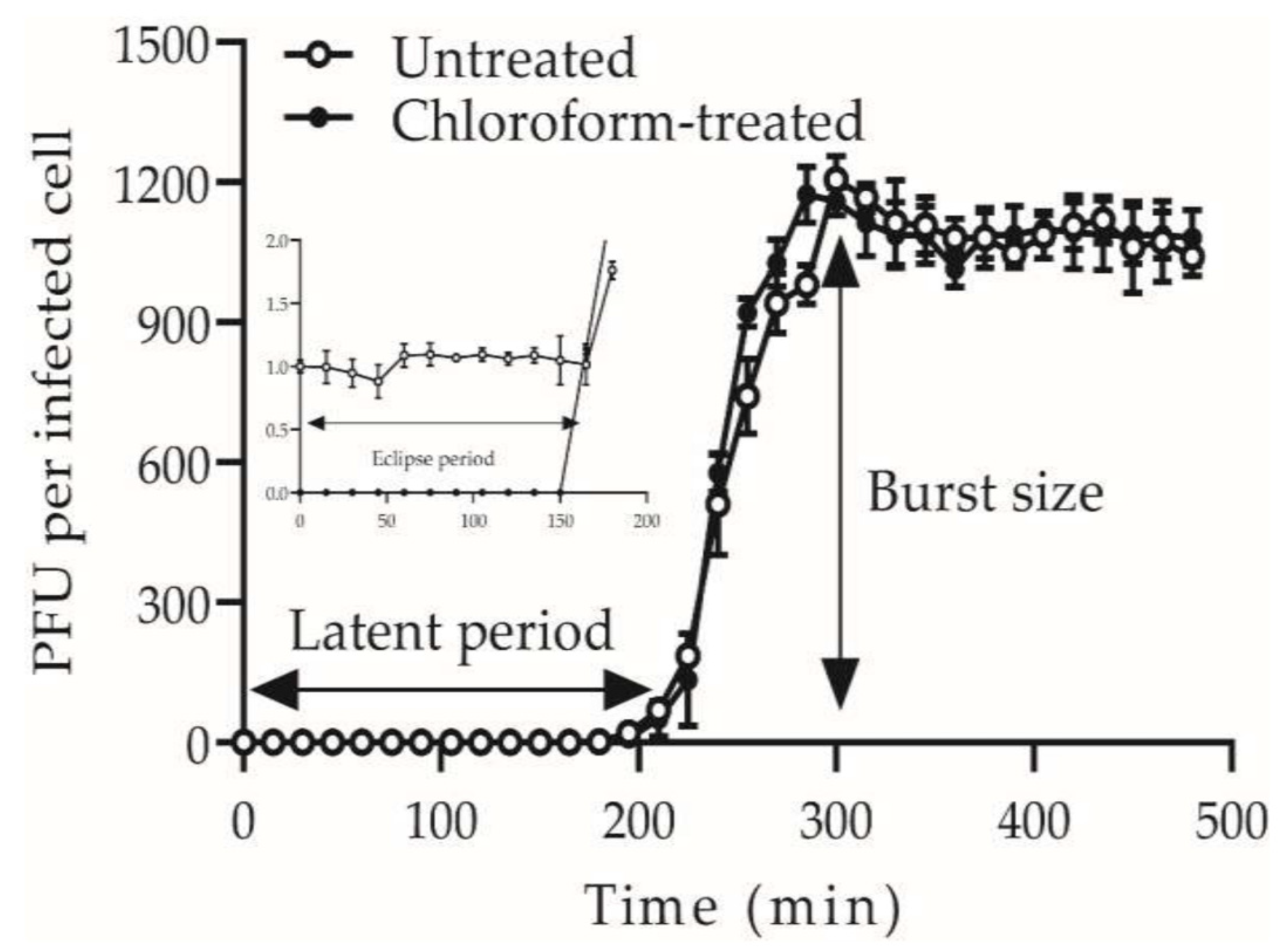

1]. This is at least to the extent that those treatments don’t also disrupt virions [

7,

62] and note also that such cell disruptions not necessarily occurring with 100% efficiency [

61]. These latter approaches, however, are limited to being used prior to the end of the eclipse, since lysis of phage-infected bacteria after that point by definition will release intracellular virions into the extracellular environment (

Section 5.3).

One can inactivate virions, such as by adding virucide, and then plate for remaining infective centers, looking for differences in titers with and without such treatment. That approach, however, will tend to provide a less definite indication of how many phages had remained unadsorbed. In any case, ideally at least two or three plates, from different dilution series if dilution series are used, should be run to determine the quantity of unadsorbed virions, so as to minimize operator error [

63]. What certainly should not be done is to just assume, without supporting evidence, that the number of phages added will be equal to the number of bacteria infected.

3.3.4. Dilute Enough, but Not Too Much

From Adams [

1], p. 14, “3. After sufficient time for antibody action”, or otherwise removal of virions by other means or accounting for free phages, “the mixture is further diluted in growth medium so that each sample will contain about 100 infected bacteria.” This dilution specifically is done prior to the start of lysis, but it is important also not to dilute too much. The latter is so as to avoid excessive variability due to sampling error, which is expected to be 10% with a minimum count of 100, such as of phage-infected bacteria. This is equal to the square root of the mean [

1,

64], something that is greater with lower numbers, e.g., 14% for a count of 50 or 20% for a count of 25. Also important, burst sizes will vary between phage-infected bacteria [

59], so the fewer bacteria supplying bursts, such as less than 100 phage-infected bacteria, then the more likely that burst size determinations could be skewed by rare, especially larger bursts.

As suggested by Ellis and Delbrück [

2], this dilution should be on the order of 10,000-fold. So too Stent [

4] suggests 40-fold dilution into media containing antiphage serum and then another 250-fold into serum-less media (40 × 250 = 10,000); see similarly Carlson [

5,

46] but without the exposure to serum, as nor do Ellis and Delbrück suggest use of anti-phage serum. If one started with 10

8 bacteria/ml, adsorbed 10

7 phages/ml to these bacteria, and diluted the mixture the indicated 10

4-fold, then you would expect to have a total 10

3 phage-infected bacteria/ml. That can then be conveniently titered by plating 100 μl volumes (

Section 4). If instead an MOI of 0.01 is employed, then that number would be 10

2 phage-infected bacteria/ml, requiring plating using 1 ml volumes. If the phage being used is slow to adsorb, then the number of phage-infected bacteria could be even lower, also requiring either less diluting prior to plating or instead plating greater volumes.

Hyman and Abedon [

6] by contrast suggested a 2,500-fold initial dilution rather than 10,000-fold dilution. This has the effect of increasing initial platings to average an anticipated 400 PFUs/plate, which has a minimum expected error of 5% rather than the 10% for an average of 100 PFUs/plate. Of course, it also has the effect of increasing plaque-counting efforts. While Ellis and Delbrück [

2] suggested instead the noted 10,000-fold dilution, they also started with 2 × 10

8 bacteria/ml, a two-fold greater bacterial concentration than that suggested by Hyman and Abedon. With an MOI of 0.1 and near-complete adsorption, Ellis and Delbrück’s approach would yield roughly 200 infected bacteria prior to lysis per 100 μl plated. Thus, there are no hard-and-fast rules as to what starting bacterial concentrations, phage MOIs, or fold-dilutions to use, just so long as phage adsorption is adequate and that with the first dilution step one ends up with neither too few nor too many phage-infected bacteria (

Section 3.3.5). It in other words is important to think through diluting issues in designing OSG experiments, as addressed in more detail here in

Section 4. For examples of OSG curves in which diluting may not have taken place following phage addition, see Figures 0045243, 0045248, 0045249, 0043940, 0044206, 0042333, 0044790, and 0045021 as well as Figure 0039663 (

Appendix A).

3.3.5. Reducing Post-Lysis Adsorption

Also from Adams [

1], p. 15, “The dilution of the adsorption mixture at the end of the adsorption period is an essential feature of the experiment because it prevents further adsorption.” Thus, if the amount of dilution is insufficient, then phages that are released upon lysis will be too likely to adsorb either infected or uninfected bacteria, due to some combination of too high resulting concentration of phages and too high remaining concentrations of bacteria. (Recall that uninfected bacteria should exceed infected bacteria in number by at least ten-fold when striving for multiplicities of 0.1 and also that uninfected bacteria can replicate in the course of OSG.) Though such additional adsorption would occur only post-lysis, the concern is included in this section because the actual dilution needs to be made pre-lysis.

Adsorption of already phage-infected bacteria can result in induction of lysis inhibition for those phages that are capable of displaying that phenotype (

Section 3.1.3). Multi-step rather than only single-step growth alternatively is the consequence of adsorption by released phages, post-lysis, of phage-uninfected bacteria (

Section 3.5.1). Either of these can result in overestimations of phage burst sizes and sometimes these overestimations can be dramatic. Be concerned especially if the rise seems to take place in multiple steps or instead if burst sizes, at least for most phages, are much greater than roughly 500. Certainly burst sizes of 1,000 or more should almost always be viewed as red flags, though with some exceptions (

Figure 1 and

Section 3.6.3). Also, the larger the burst size, then the more likely that released phages will adsorb still-intact bacteria. See

Section 3.5.1 and

Section 3.5.2 for additional discussion of these issues.

A further advantage of this post-adsorption, pre-lysis dilution step is that it eliminates a need to aerate cultures, since resultant bacterial densities are so low [

5,

46]. That, of course, assumes that the media is already aerated, but such aeration can be assured via vortexing in the course of this diluting. See

Box 1 where we speculate that a failure to sufficiently dilute could have led, e.g., to poor oxygenation of bacteria later in experiments.

3.3.6. Bacteria Can Lyse During Enumeration

Something that can occur upon plating of seemingly still pre-lysis cultures is the lysis of phage-infected bacteria, particularly as OSG experiments get closer to the start of the rise. As a consequence, for example, long delays between sampling and plating can give rise to latent period underestimations, with the timing of sample acquisition differing somewhat from the timing at sample plating. Such events can result in unusually high plaque counts, i.e., unexpectedly large jumps in these counts that also don’t follow the otherwise smooth increase in titers normally seen during the rise. Adams [

1], p. 481, as a consequence wrote that “any point along the rise portion of the single step curve may lie well above the curve. Since there is no compensating error which may lead to correspondingly low counts, these high points must be disregarded in drawing the curve. … If this is included in the average value used to calculate the burst size, it may lead to significant error.”

3.4. During Lysis: The Phage Rise

During lysis, plating for infective centers should take place as a continuation of especially late pre-lysis enumeration, since generally the reason that OSG enumeration is being undertaken is that we don’t precisely know when the start of lysis is going to occur. This plating for plaques should continue through to the end of lysis, and then some, with the span from start to finish of this lysis known as the rise. It certainly is possible to learn from previous OSG experiments, i.e., prior biological repeats, just when lysis is expected to occur, especially its beginning, and then adjust the timing of ones plating accordingly (e.g., see

Section 4.1).

3.4.1. Use Log-Phase Indicator Bacteria

It is not uncommon to use stationary phase bacteria, such as overnight cultures, as indicator for titering [

65]. A concern here is that efficiency of plating might vary as a function of the physiology of indicator bacteria, particularly often declining with the use of stationary-phase rather than log-phase bacteria, though not always [

66,

67]. In addition, however, EOPs can vary with the state of the potential plaque-forming units [

66]. Specifically, a plaque should be more likely to form starting with, e.g., 100 phages released from a just-plated phage-infected bacterium than from an isolated virion. As summarized by Adams [

1], p. 494: “The relative efficiency of plating of infected bacteria is usually higher than that of free phage, so both should be determined.” Thus, using, e.g., stationary phase indicator bacteria could have the effect of reducing measured burst sizes, which explicitly during OSG are ratios of free phages (potentially displaying lower EOPs) to phage-infected bacteria (potentially displaying higher EOPs) (

Section 3.5.4).

The previous point can be generalized to concerns over efficiencies of plating that are reduced by any mechanism (

Section 3.1.3). As the primary concern is that of differences between the plating efficiencies of free phages vs. phage-infected bacteria, this issue can be readily checked experimentally and then accommodated in calculations as needed. For example, compare the titers of pre-adsorbed phages [

67] to directly plated free phages. Ideally those titers will be the same. But even if they are not the same, their ratios can be used to adjust burst size calculations [

66]. Nonetheless, it is probably good practice simply to avoid using stationary phase bacteria as indicator when generating OSG curves, unless efforts are made to assure that it doesn’t impact free phage vs. phage-infected bacteria efficiencies of plating.

3.4.2. Too Many Time Points Is Preferable to Too Few

Adams [

1], p. 14, states, “4. The suspension of infected bacteria is sampled at intervals until lysis is completed and each sample is assayed by the plaque count method.” Note, though, that no mention is made in that statement of either when or how often to sample. Though subsequently addressed by Adams (time points in the example presented by Adams were taken every 1 to 2 min for much of the assay), over the years many researchers, in our opinion, have become overly obsessed with ‘when’ and insufficiently concerned with ‘how often’. Thus, and though seemingly obvious, our experience has been that this still has to be stated explicitly: The precision of the lysis timing event should be directly proportional to the length of intervals between time points. In this section we thus consider ‘how often’, whereas in the next two sections (3.4.3 and 3.4.4) we address ‘when’.

In terms of how often, if OSG experiments are sampled every five minutes, then it can be difficult to describe measured latent periods – particularly the length of what is known as the constant period, i.e., which ends at the start of the rise – in any less than five-minute units (e.g., 10, 15, or 20 min). Certainly, it is not permissible to conclude that measured latent periods were, e.g., 18 min after having taken five-min time points. Thus, Adams [

1], p. 475, states that if “plaque counts… are constant through 21 min[,] but increase suddenly by 23 min[,] so the end of the latent period comes between 21 and 23 min.” The conclusion, in other words, should not be, e.g., 22 min (though see

Figure 2 where for convenience we conclude just that). See though

Section 3.4.5 for a possible contradiction to this latter statement, but one requiring more rather than fewer time points. If high precision is desired, and we certainly hope that it would be, at least following pilot experiments, then consider taking additional time points especially while lysis is thought to be occurring. Indeed, feel free to take as many time points as you can in the time-vicinity of especially of the initial lysis event (

Section 3.4.4).

Adams in his example takes time points every minute from 19 to 26 minutes, as encompasses the start of lysis, as occurred indeed at 22 min. In addition are four time points taken prior to lysis. Doermann (1952) took at least 25 time points over 25 min (10 to 35 min) in the OSG experiment he presents. This includes over 10 time points prior to lysis and at least 8 time points during the rise, seemingly taken at random intervals. Of course, there are only so many time points that can be taken especially at the start of lysis, since the interval over which this occurs is short. Nevertheless, there is nothing stopping one from taking as many time points during this brief, rise-initiating interval as one possibly can.

3.4.3. It’s Not Essential to Keep Intervals Between Time Points Constant

Time points need to be taken for OSG experiments during three distinct, post-adsorption periods: prior to, during, and following phage-induced bacterial lysis (

Section 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5, respectively). There is no inherent reason, however, that the intervals between time points should be identical during these distinct periods. We note that this statement seems to contradict Kropinski’s [

7], p. 41, indication of an importance to “following a rigid time frame.” Kropinski in his example OSG experiment, however, uses 2-min time points. Therefore, to clarify: Not keeping intervals between time points “Rigid”, as suggested in this section, is a means of

reducing the overall number of time points taken. Unfortunately, exploration of phage publications (e.g., see

Appendix A) suggest that many researchers have used this notion of a desire for rigidity toward reducing the number of time points taken overall, e.g., by using 5-min rather than the 2-min rigid time point intervals used by Kropinski. Indeed, Kropinski goes on to note (p. 46): “After running your experimental OSG experiment the first time you will be able to judge how often you should sample and from which flask. To make sampling easier, an overlapping timing of sampling from each flask is recommended.” Thus, we both recommend

not explicitly following the advice for rigidity provided by Kropinski while at the same time commending the effort he put into assuring OSG precision.

Notwithstanding that latter point, and as emphasized in the previous section (3.4.2), reducing intervals between time points should be encouraged. This is particularly when lysis is thought to be occurring, i.e., during the phage rise and especially at the start of the rise (the latter defining the end of the constant/minimum latent period). That is, quite the opposite of following a rigid plating schedule. Nonetheless, clearly using multiple, different time point intervals over the course of a single experiment can be complicating. One solution is to record time points as they are taken, as seems to be the case in the classic, Doermann (1952) OSG experiments and see also the OSG example found in Adams [

1]. This is rather than limiting time points to explicit intervals, e.g., every five minutes (as an aside: OSG curves using five-min time intervals should never be acceptable for publication except for viruses that display very long latent periods, e.g., of roughly one hour or more).

At the same time, this somewhat more unstructured approach to taking time points can lend itself to both not delaying platings and not plating individual time points multiple times per experiment, two things we recommend (

Section 4). To present multiple experiments having non-overlapping time points in the same graph, if that is desired, then one can simply show all of the time points taken – also something that we encourage – rather than indicating individual time points as averages. Taking that approach, however, requires normalizing titer outputs, which is something that we suggest regardless (

Section 3.5.3).

3.4.4. Take Sufficient Numbers of Time Points at Each Stage

During all three post-adsorption OSG stages, phase, or periods, sufficient numbers of time points should be taken. For example, up to five, if not even more, for each of these periods, for a total 15 time points, and ideally even more. There are, however, different reasons for taking numerous time points during each period.

Following adsorption and prior to lysis (

Section 3.3), the goal is to be highly sure of what is the initial number of phage-infected bacteria. This will be your denominator in burst size calculations (

Section 3.5.4), as well as the number to normalize to when comparing experiments (

Section 3.5.3). See

Section 3.5.3 as well for discussion of how you may go about generating those pre-lysis determinations of representative numbers of infective center.

During lysis (this section), the precision of your determination of the start of lysis, as the end of the constant period, will be highly dependent on the extent to which you succeed in catching the start of that lysis. Alternatively, catching the start of lysis can depend on how effectively you are able to graph the rise overall (see

Section 3.4.5 for the latter). Thus, taking only five time points may not be enough over the course of the rise, and certainly will not be enough if the goal is to precisely characterize the extent of the rise, unless that interval is very short.

Following lysis (

Section 3.5), it is important again to take a reasonable number of times points. This should be done for a number of reasons: (1) To assure yourself that the rise really has ended, (2) to better determine post-lysis phage titers, and (3) to make sure that post-lysis phage titers have stabilized rather than continue to rise (

Section 3.5.2). All three, but especially (1) and (2), need to be done for the sake of burst size determinations (

Section 3.5.4), while (3) is needed to make sure that experiments don’t involve more than one step (

Section 3.5.1), or indeed aren’t displaying lysis inhibition (

Section 3.1.3). It will tend to be easier to accomplish these goals if more time points are taken post-rise rather than fewer. Examples of OSG curves in which too few time points were taken during one or more periods of OSG include Figures 0045242, 0045243, 0045246, 0042856, 0045247, 0045248, 0045249, 0043940, 0043940, 0034153, 0039663, 0045245, 0044206, 0045250, 0039663, 0042333, 0044790, and 0044790, 0045021 (

Appendix A).

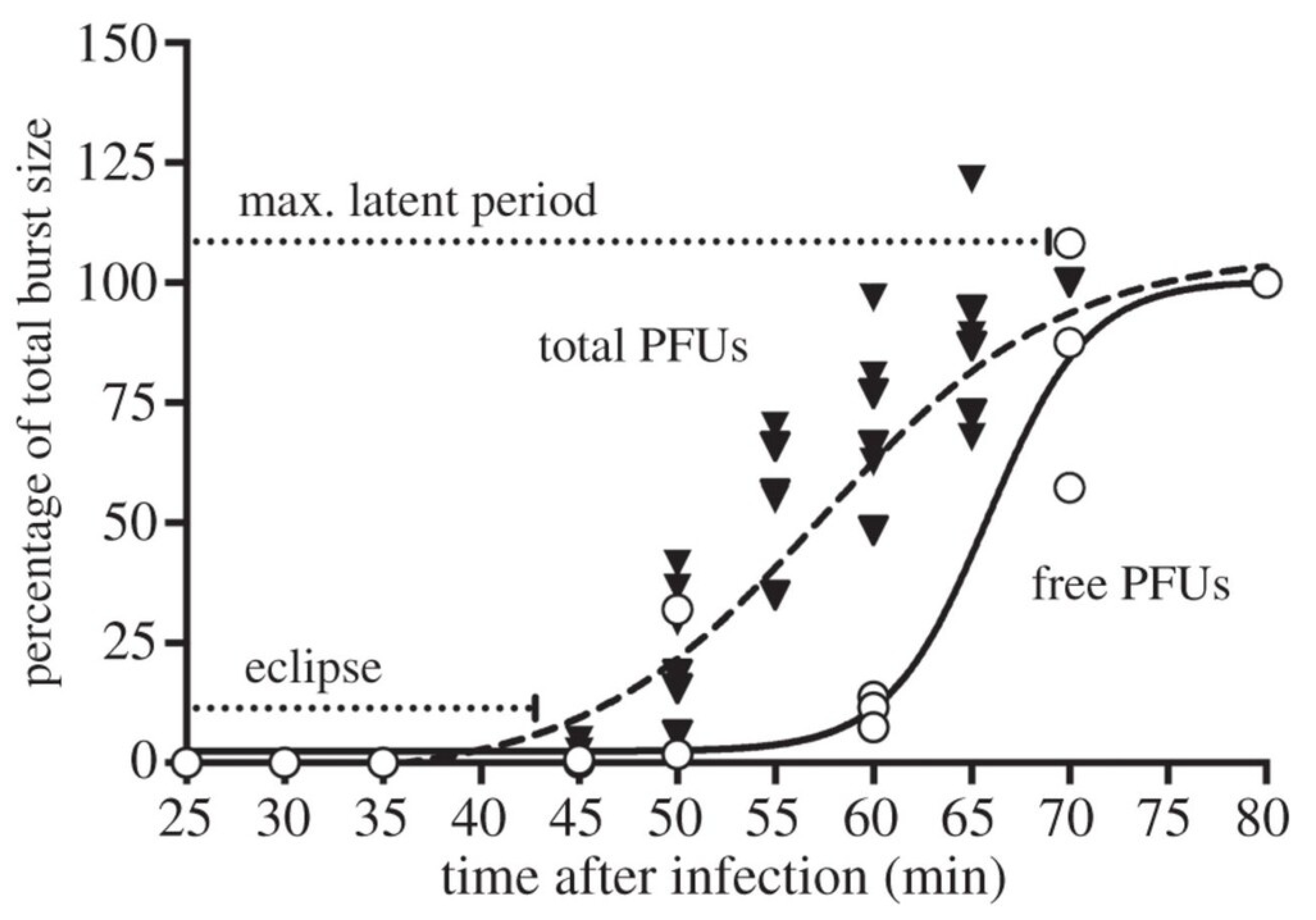

3.4.5. Defining the Constant Period

Adams [

1], p. 14, states, “The latent period is defined as the minimum time between the adsorption of phage to [the] host cell and the lysis of the host cell with release of phage progeny”. This places the end of the phage latent period, or what here we are describing as the minimum phage latent period, at the start of the rise, where minimum latent period is also called a constant period. Since the start of the rise is a specific time, the more time points that are taken during an OSG experiment, then the more precisely the minimum latent period can be determined. The alternative would be capturing the rise in its entirety with a single time point, such as is the case in the example described in

Box 1 (and see also

Appendix A, Figures 0045243, 0045249, 0034153, 0039663, and 0039663).

That is, consider this progression: the titer is the same as pre-lysis (first time point), then the titer is above the pre-lysis titer (second time point), and then the titer is the same as post-lysis titer (third time point). With only a single time point being intermediate between the pre-lysis and post-lysis phage titers, then at best one can declare that the rise began and ended sometime between those two extremes (pre-lysis and post-rise). This is instead of the rise corresponding in some way to that single, intermediate, during-rise time point. In other words, if lysis hasn’t occurred by 20 min, has started by 25 min, and has more or less been completed by 30 min, then there is no justification for declaring that the rise spanned those ten minutes nor, and more to the point, that the minimum latent period is either 20 minutes or 25 minutes, even if the titer at 25 minutes is somewhat greater than the pre-lysis titer. Rather, the minimum latent period, in this case, must have ended somewhere between 20 and 25 minutes, and we have no idea the full duration of the rise.

Or Draw a Line Through the Rise

Notwithstanding the previous paragraph, there actually are at least two ways to go about defining the timing of the start of the rise, and how that timing is defined should always be explicitly stated in publications. Though it can be tempting to describe this timing as the first time point that exceeds the pre-lysis titer, i.e., as emphasized immediately above, it in fact can be preferable instead to draw a line through those time points that unambiguously make up the rise (i.e.,, see

Figure 2). Then, consider at least comparing the first time point where the rise seems to have started with where the two lines intersect, the slanted line corresponding to the rise and the horizontal line corresponding to the average (or equivalent; Section 3.5.4.2) initial phage titer. Consider, though, how difficult it can be to draw a meaningful line if only a minimal number of time points define the upward trajectory in phage titers of the rise. Thus is the alternative utility of taking as many time points as possible (

Section 3.4.2), especially in the vicinity of the rise, or at least the early rise (

Section 3.4.4).

Note that Kropinski [

7], pp. 44 and 46, in fact suggests both approaches, though not necessarily concurrently. Thus, on the one hand is this statement, “Determine the intersect between the AVERAGE 1 line and the slope will give you the latent period of your phage.” But on the other hand is this, “If you are planning on just determining the latent period in the first experiment you do not need FLASKS B or C.” The former, that is, is recommending drawing a line through the rise while the latter is recommending that only the very beginning of the rise be monitored quantitatively. In the example presented in that publication, these two approaches would calculate different constant period lengths, with the former’s being a few minutes longer than latter’s. Further complicating this matter, Kropinski [

7] also suggests using semi-log graph paper for plotting OSG curves (see too Adams [

1]), though he contradictorily provides an example OSG experiment using instead a linearly plotted

y axis, with the latter plot being used as the example of line drawing. Presumably that line would indicate a different constant period, however, if the plot instead were graphed using the semi-log approach. What all of this points to regardless is a need to describe in publications explicitly how latent periods have been calculated.

Or Don’t Define Latent Period as the Constant Period

One may instead declare the timing of lysis, as defining the duration of the latent period, as occurring at the mid-point of the rise, e.g., [

68]. If that is the case, then again it should be unambiguously indicated in publications that this was done (which indeed is the case in the cited publication). Determining that mid-point can be greatly aided by using the same approach of line drawing for a best fit curve through the rise (previous section), though here it will be important to determine two intersections, one intersection with the before-lysis average (or equivalent; Section 3.5.4.2) phage titer and the other intersection with after-lysis average phage titers (again or equivalent). Note also that it may be preferable to draw the line with a

y axis, which denotes numbers of infective centers, that has been log-transformed [

1], that is, rather than that axis graphed linearly. The midpoint of the rise is then found as the halfway point between the two intersections.

Unfortunately, as a further complication on the concept of latent period and the time of the midway point of lysis, the concept of midway can have more than one meaning. Specifically, the midpoint can be defined either in terms of time only – halfway between the time of start of the rise and the time of the end of the rise – or instead represent the time at which the rise has increased by halfway. One advantage of the latter is that it eliminates the need to precisely estimate the starting and ending points of the rise since the point at which the rise has increased by half is simply 50% of the burst size, though it is still important to draw a best-fit line representing the rise, and in this case presumably to use a linear rather than log-transformed scale for the

y axis. Thus, we can envision defining a phage’s latent period in terms of the start of the rise, the end of the rise (see

Figure 1), the midway point in time between those two extremes, and the time at which burst size has reached 50%. The latter might even vary depending upon whether the best-fit line for the rise as being used to correlate time with phage titer is or is not based on a log-transformed

y axis even if still defining 50% linearly (that is, the two lines and therefore the 50% points would not necessarily be identical). Also, the placement of the midpoint can be dependent on how well phage adsorption was synchronized (

Section 3.2.3), i.e., the less synchronization, the longer the rise, and the farther from zero the midpoint.

Which Approach Is Preferable?

The process of determining the mid-point of the rise can be complicated (above). Therefore, it often is preferable to just consider the constant period as the latent period (Section 3.4.5.1) and then also, if desired, describe an estimation of the duration of the rise. Regardless of how one defines the concept of latent period, it is insufficient to state only that latent period length is x minutes. Instead, and as noted, it is important to explicitly indicate, e.g., that lysis began at some point after the start of adsorption, thereby unambiguously defining a phage’s minimum latent period, a.k.a., constant period (and if possible to indicate the uncertainty associated with the estimation, e.g., between 21 and 23 minutes rather than just stating, “22 minutes”). Alternatively, that latent period may be described as ending at the middle of the rise, thereby serving as an approximation of an average latent period. That definition of latent period, however, also needs to be explained explicitly, as without such guidance the reader may find it difficult to tell what exactly was meant by latent period. Given all of these variables, including variation as seen between both experiments and laboratories (as well as conditions and bacterial hosts), it is best in most cases to not read too much precision into published latent period determinations.

3.5. After Lysis: The Post-Rise

The time during OSG that follows lysis, i.e., the post-lysis phase or period, can be described also as a post-rise [

6,

69,

70]. Ideally, over this interval, PFUs will consist entirely of free phages, and those free phages will remain constant in number over time. That is, following lysis, titers during OSG should plateau. Enumeration during this period serves to determine the numerator in burst size calculations, i.e., [post-lysis PFUs] ÷ [pre-lysis PFUs] = burst size (

Section 3.5.4). This measurement also can be relevant toward defining a midway point of the rise (Section 3.4.5.2). Our advice is as follows.

3.5.1. Avoid Two- or Multi-Step Growth

Defining features of OSG are for phage population growth (

Section 2.1) to span only a single lytic cycle (

Section 2.2) along with lysis occurring in a coordinated fashion across a culture (for the latter, contrast, e.g., phage release from uninduced bacterial lysogens). Both – one step of growth and coordination of lysis – require that virions released in the course of bacterial lysis should not be able to encounter and then adsorb additional cells, particularly phage-uninfected bacteria that are found in the same culture. To avoid that post-lysis adsorption, some means are needed to reduce the likelihood during OSG of this so-called epidemiological secondary infection [

71]. The principal means of preventing this occurrence of new phage infections is to dilute cultures (

Section 3.3.4). This is so that bacteria, both infected (source of new virions) and uninfected (adsorption target of new virions), are no longer present at higher concentrations. For an example of at least possible two-step phage population growth during an “OSG” experiment, see Figure 0045248 (

Appendix A). For possible multi-step growth, see Figures 0044206, 0039663, 0042333, and 0045251 (also

Appendix A).

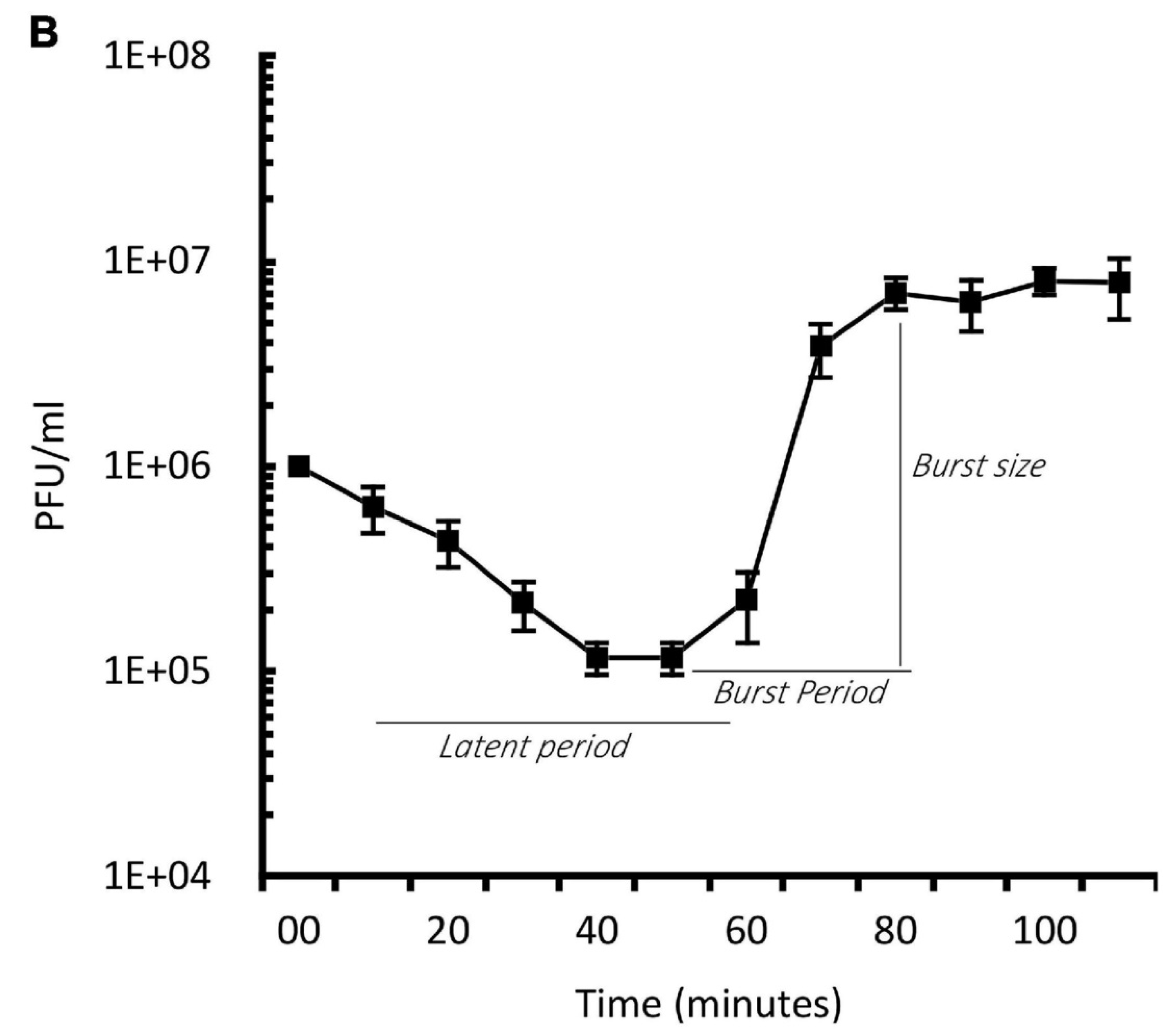

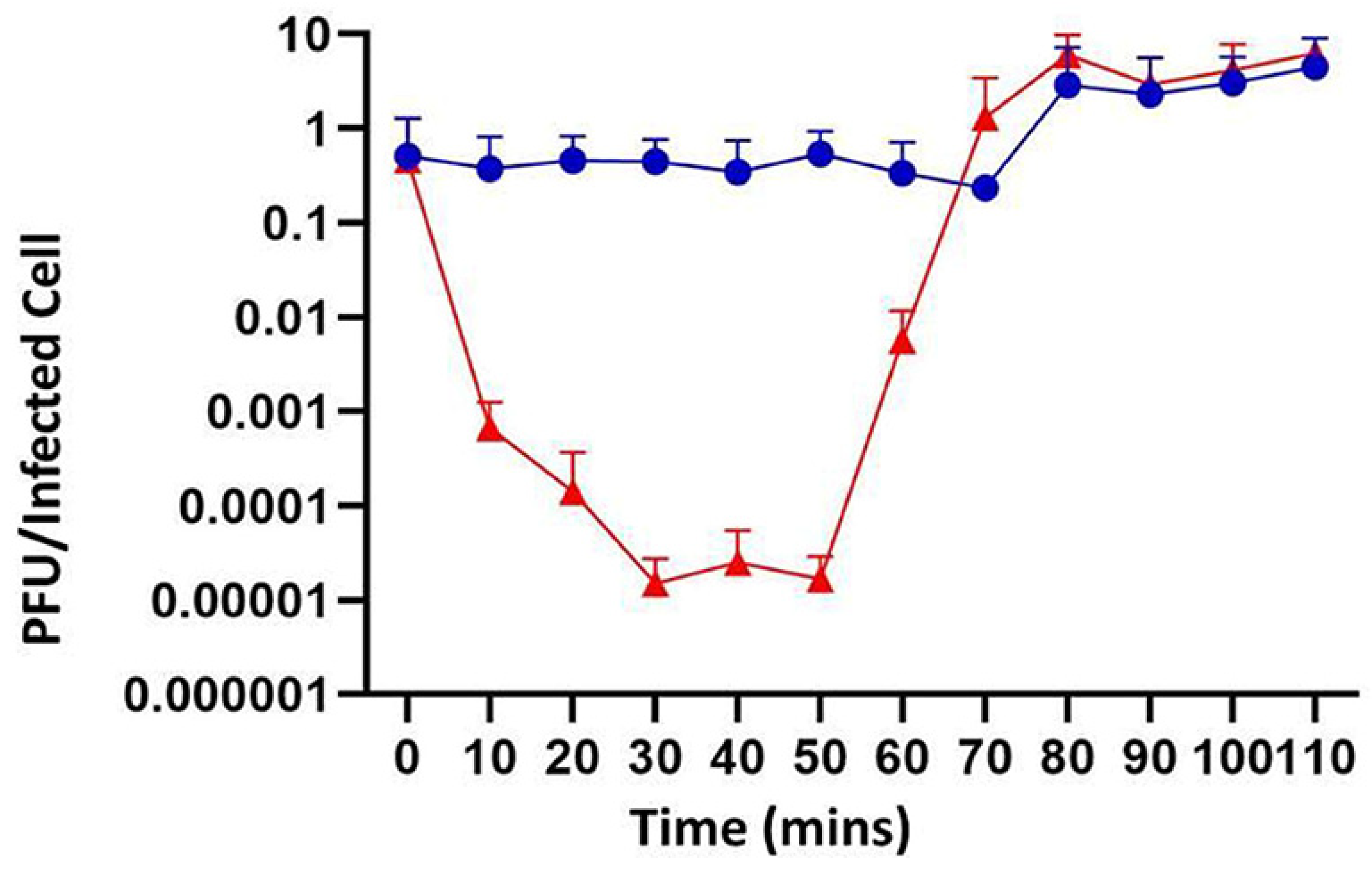

If those efforts toward reducing subsequent infections of bacteria by phages are not successful, then this can be evidenced by observation of unexpectedly long rises, as indicating ongoing phage bursts, i.e., less-coordinated culture-wide bacterial lysis. Alternatively, one could observe post-rise plateaus in phage titers that don’t remain plateaued, but instead which come to rise again – thus no longer stabilized in titer – as indicating phage bursts occurring in multiple steps [

2,

10,

72,

73,

74]. Additional evidence for such multi-step growth is unexpectedly large burst sizes, i.e., post-rise numbers of PFUs that too substantially exceed pre-lysis numbers of PFUs. Though an indirect measure, the latter also is suggestive of more than one round of phage population growth, again perhaps particularly due to insufficient culture dilution prior to lysis. Rises that lead to unexpectedly large burst sizes are not uncommon in the phage literature (

Appendix A).

3.5.2. Looking for Post-Rise Plateauing

Necessary for avoiding multi-step growth is being able to recognize that such growth has occurred, i.e., as considered immediately above (

Section 3.5.1). One cannot tell that multi-step growth has occurred, however, unless the post-lysis aspect of OSG has been extended for sufficiently long. How long is sufficient, however, is an open question. Certainly, it should be intuitively obvious to a reader when looking at OSG curves that an experiment has been extended beyond the rise and then has stabilized in terms of the resulting titer. Simply stopping after one or two seeming post-rise time points, by contrast, should not be viewed as acceptable practice.

For examples of well-establish post-rise plateauing, see Figures 0045249, 0045246, 0042856, and 0043940 (

Appendix A). Examples of inadequate explorations of the post-rise period include those of Figures 0045242, 0045243, 0045248, 0034153, 0039663, 0039663, 0042333, and 0044790 (also

Appendix A). Examples of a post-rise that continues to increase in titer include Figures 0045245, 0045251, and 0044790 (

Appendix A).

For the sake of burst-size determination precision, it can be useful to obtain at least five post-rise time points. If 5-min time intervals are being used at this point – here unlike during the rise, 5-min time intervals are perfectly appropriate – then it is not unreasonable to extend OSG experiments for approximately one-half hour post-rise. If those time points have been taken over such a span of time that it is unambiguous that the rise is over, then that should be sufficient to declare an OSG experiment completed. Or, in other words, the goal in OSG is one step of phage replication, as should be determined by observing that a reasonably stable post-rise plateauing has occurred. If that is what is observed, even if determined only by eye, then that generally is good enough. Alternatively, it is of concern if titers continue to increase over the course of the post-rise, or if a post-rise never seems to occur then that should be viewed as problematic. In the case of a rise that ‘refuses’ to plateau, the first suspect in debugging the experiment should be insufficient pre-lysis dilution (

Section 3.3.4).

Often, post-rise increases in titers within OSG figures are less than obvious when viewing a submitted or published manuscript, or even when viewing one’s own experiment. It is possible, however, to draw virtual boxes within PDFs to help gauge whether such increases have occurred (e.g., see Figure 0044790,

Appendix A). As a bottom line: OSG curves that display rises that have not plateaued, or excessively large burst sizes, may not consist of only a single step but instead may be displaying two or more serial rounds of phage infection and lysis. Such multi-step growth is definitively unacceptable for claimed OSG experiments.

3.5.3. Normalize to Starting Numbers of Plaque-Forming Units

Many times one sees OSG experiments graphed with the y axis indicated as PFUs per ml. That is, plaque-forming units, or, more traditionally, as infective centers per some volume. This can be problematic for at least two reasons. The first issue occurs when comparing biological repeats of the same experiments. These may begin at slightly different titers, thereby greatly complicating graphing or, at least, complicating the viewing of the variation associated with multiple repeats. The second issue is that this per-volume data-presentation approach makes it difficult for readers to easily estimate burst sizes by eye, which can be very helpful to readers, as well as to experimenters, especially when attempting to establish whether burst sizes were calculated correctly (obviously correct calculation of burst sizes, strikingly, is not always the case).

What normalizing the

y axis of OSG curves consists of is simply dividing all titer values by the average titer of phage-infected bacteria found prior to lysis. Thus, curves should start with the number of infective centers averaging around 1 (or averaging around some other statistic, also giving rise to a value of 1; Section 3.5.4.2). At the end of the constant period, numbers of infective centers should then rise to above 1. Post-rise, numbers of infective centers will (ideally) have then stabilized (

Section 3.5.2) to a value that as graphed is explicitly equal to the phage average burst size. Thus, it should be possible to estimate with minimal effort both the start of the rise and the resulting burst size visually from graphs of OSG. That is, one should be able to easily see that the curve has risen above 1 (the start of the rise), and there also should be no need for readers to mentally divide post-rise titers by pre-lysis phage titers.

See Figures 0045241, 0045247, and 0044790 (

Appendix A) as examples of normalized

y axes as well as

Figure 2. For examples of oddly, seemingly incorrectly normalized

y axis or just inadequate presentations, see Figures 0045249, 0039663, and 0039663 (

Appendix A).

If reporting actual titers is still preferred, consider presenting in separate panels both figure types, raw titers and titers normalized (divided) by pre-lysis PFU counts. Caution, though, as the latter can make it easier for reviewers to intuitively identify issues with OSG experiments! The upshot is that actual titers, though they may seem to be more ‘real’ than normalized titers, in fact are fairly arbitrary, often reflecting simply what dilutions were being used as the experiment was conducted rather than necessarily having relevant biological meaning. Phage numbers starting at 1 (for one phage-infected bacterium) and then increasing to a burst-size number of phages upon plateauing, by contrast, does have explicit biological meaning.

3.5.4. Burst Size Calculation

The standard burst-size calculation is the following: (phage numbers after lysis has occurred = numerator) divided by (numbers of phage infected bacteria found prior to the occurrence of lysis = denominator), i.e., [post-lysis] ÷ [pre-lysis]. For robust burst-size determinations, both measures need to be accurate. In part this means that numbers of time points taken to define both numerator and denominator need to be reasonably high, i.e., consisting of at least three time points and ideally at least five time points. It also means that these time points should be somewhat internally consistent and, particularly for the numerator, have plateaued (

Section 3.5.2). Therefore, it should be possible to simply look at a figure depicting an OSG curve and observe a more-or-less horizontal line that is found prior to the start of lysis (ideally normalized to 1;

Section 3.5.3) and then a more-or-less horizontal line that is found post-rise (which, in a normalized curve, is equal to the burst size). If the line following lysis seems to be rising, then as noted (

Section 3.5.2) it may be that insufficient dilution prior to lysis has taken place; such experiments should be discarded and the OSG protocol then modified.

Subtracting off Unadsorbed Virions

Accurately defining the denominator, i.e., the starting number of phage infections, as we have suggested actually has two aspects. These are the precision of measures (

Section 3.4.4) and the biological accuracy of measures. The latter means that it is necessary to make sure that starting numbers of phage-infected bacteria include just phage-infected bacteria and not also free, unadsorbed virions (

Section 3.3.3). This issue comes up explicitly because it usually cannot be counted upon that all added phages will adsorb during the adsorption step (

Section 3.3.2), and this is especially a concern the greater the fraction of starting phages that have not adsorbed. For example, if 10% of starting phages haven’t adsorbed, then burst size claims will inherently be calculated as ~10% smaller than they actually are (

x/1.0 vs.

x/0.9, where

x is the number of phages, i.e., numbers of PFUs as infective centers that are present post-lysis). To combat this inaccuracy, it therefore is necessary to both determine and subtract off numbers of free, unadsorbed phages that are present after the adsorption stage has been intentionally ended, i.e., especially following culture dilution (

Section 3.3.4).

Addressing Outlier Values

Another consideration is the issue of outlier data, which can skew input values for burst size calculation. This skewing especially is higher should a lysing bacterium be found within a single plating, though Adams [

1] explicitly suggests to simply disregard such time points (

Section 3.3.6). One way to address this latter problem, of bacteria lysing during plating, is to take more time points both before and after lysis, as well as to not delay platings (

Section 4), so that outlier data are more noticeable.

Alternatively, it is possible to statistically disregard outlier data points, or at least reduce their impact, without explicitly ignoring them. Thus, for example, it is also possible to employ geometric rather than arithmetic means, which can reduce the impact of especially higher outlier points. For example, the arithmetic mean of 110, 90, 125, 87, and 250 is 132.4, whereas the geometric mean, GEOMEAN in Microsoft Excel®, is 121.9, which is somewhat less affected by the 250 datum than the arithmetic mean. Another approach, also statistical, is to employ medians for the numerator as well as for the denominator rather than means. This is a suggestion for titering generally [

63] and has the benefit of automatically eliminating outlier values from calculations. Thus, the median of the above data is 110, which does a good job of reflecting the non-outlier values of 87, 90, 110, and 125. An equivalent but more refined approach, also as discussed in Abedon and Katsaounis [

63], is to employ instead trimmed means (TRIMMEAN in Excel®), which serve to remove outlier data points while at the same time not eliminating averaging to the same degree that use of medians can. For example, the mean of the above data set in which one-quarter is trimmed from either end (TRIMMEAN([array],0.5)) is equal to 108.3. In any case, the idea is to minimize the impact of outlier data prior to dividing post-lysis titers by pre-lysis titers and, ideally, to use an approach that is other than arbitrary removal of those outliers (though we agree with Adams that unexpected high titers observed near the expected point of phage lysis should be simply removed from pre-lysis titer calculations, assuming that they can be recognized as outliers).

From the pre-lysis data provided by Adams [

1], the numbers are 98, 105, 93, and 110, which have an average (arithmetic mean) of 101.5, a median of 101.5, a geometric mean of 101.3, a 25% trimmed mean of 101.5, a standard deviation of 7.5, and square root of the mean of 10.1 (the latter is the theoretical minimum standard deviation of these data; see

Section 3.3.4). Replace the number 93 with the number 32 and results of the same calculations instead are 86.3,

101.5, 77.6, 101.5, 36.5, and 9.3, respectively. Change that same number, 93, to 210 and the results are 130.8,

107.5, 124.2, 107.5, 53.1, and 11.4. As you can see, the median value, emphasized with bold text, is the least affected by these changes: 101.5, 101.5, and 107.5 for the median (as well as for trimmed mean) but 101.5, 86.3, and 130.8 for the arithmetic mean. Importantly, in this case we are working with an

n of 4. With an

n of 3 it is still possible to attain similar results using the median if two ‘correct’ values are somewhat close (e.g., for 100, 110, and 250 the median is 110). That utility is lost completely relative to the arithmetic mean, however, if

n is reduced to 2 (e.g., for 100 and 250, the median is 175). Thus, it pays to obtain at least three unadsorbed phage-free time points prior to lysis and ideally more time points than that, if only for the sake of increasing median-mediated precision in burst size data handling. Regardless, false burst sizes that are generated from faulty OSG titer averaging effectively are worse than not attempting burst size determinations at all.

Averaging Average Burst Sizes

Average, referring to the burst size output of an OSG experiment, is shorthand for ‘population average’. That is, across a population of phage infections, burst sizes are expected to vary from cell to cell [

59], while OSG experiments by design determine the averages of this variation.

Alternatively, there is an average, or equivalent value, referring especially to pre-lysis and post-rise phage titers, which is addressed in the previous section (3.5.4.2). It is these values that are used to calculate the population average burst size for a given biological repeat (

Section 3.5.4, above). The resulting population average burst size, per biological repeat, therefore is the product of averaged pre-lysis and averaged post-rise titers. At this point a global average of population average burst sizes can be determined, an average of the calculated population average burst-size results of the individual biological repeats.

The reason that this latter point (previous sentence) needs to be made is that one means of presenting OSG growth curves is as averages of the individual time points obtained per biological repeat, which is yet another kind of average, an average of time-point values. That approach, however, might lead to determining pre-lysis phage titers and post-rise phage titers as averages of average time-point values: One value for each time point obtained by averaging those time-point values from multiple biological repeats. The problem here, though, is that pre-lysis phage titers especially can vary randomly as a function of the number of virions initially supplied to bacteria.

Imagine, at an extreme, pre-lysis averaged titers of either 1 or 10 and corresponding post-rise titer averages, respectively, of 100 and 400 (that is, one biological repeat with a calculated population average burst size of 100 and another biological repeat with a calculated population average burst size of 40). Here, for simplicity, we will assume that just one averaged time point is being used to generate the pre-lysis titer and one averaged time point is being used to generate the post-rise titer (see for example

Section 3.5.4.4). Taking the average of pre-lysis time point values gives (1+10)/2 = 5.5. Taking the average of the post-rise values gives (100+400)/2 = 250. Using those two values gives an average of the population average burst size of 250/5.5 = 45.5. Alternatively, as suggested here, the calculation should be (100+40)/2 = 70, which obviously is a different value. This difference, though, will decline the closer the population average burst size values are for individual biological repeats.

In addition, not all OSG experiments necessarily are done in such a way that it is possible to calculate burst sizes based on averages of individual time points, i.e., as suggested here (

Section 4.1.5). For these reasons, consider determining population average burst sizes on a per-biological repeat basis, and then calculate the average of these individual, per biological repeat, population average burst sizes. Alternatively, it is also possible to approach this ‘averaging’ of the results of individual biological repeats in the same manner as described immediately above for pre-lysis and post-rise titers (Section 3.5.4.2). Consider too publishing OSG curves showing all, normalized (

Section 3.5.3), time points taken (e.g.,

Figure 1) rather than averaging together the time-point values from individual biological repeats, even if doing such averaging is possible (again, e.g.,

Figure 1).

Yes, there are advantages to being maximally orderly, taking time points always after the same interval and then averaging those individual time points together when performing and then presenting many types of experiments. It’s just not nearly as advantageous to do so during OSG, plus can actually be detrimental to the process. The appropriate English-language idiom, regarding such OSG orderliness without actually aiding, in this case, successful burst size determination, is that of “Putting lipstick on a pig”.

How Not to Calculate Burst Size