Music-Induced Activation of the Reward System

Studies indicate an activation in the ventral and dorsal striatum during happy music [

1,

5]. The ventral striatum is a collection of brain areas in the brain's center, just above and behind the ears. It includes the nucleus accumbens (closely related to the dopamine system), mediating pleasure and reward-related learning. On the other hand, the dorsal striatum is more associated with habit formation, action selection, and reward-driven behaviors.

Reward pathways (for example, the mesolimbic dopamine system) are networks of interconnected brain regions that underlie these pleasure-driven responses and also reinforce positive behaviors.

Reports have shown that statistically significant effects of happy classical music were centered in the dorsal striatum's caudate and the striatum's ventral region [

1,

2,

4,

6]. Those activations can reveal the ability of happy classical music to elicit movement or motivate approach behaviors (the tendencies to move toward a positive stimulus). These findings offer direct neurochemical evidence linking music to the reward circuitry of the brain.

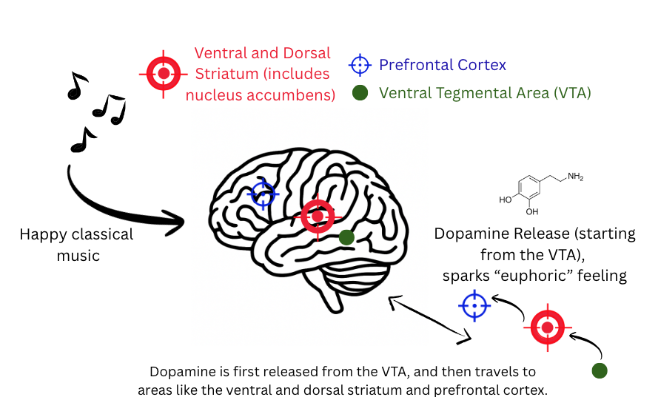

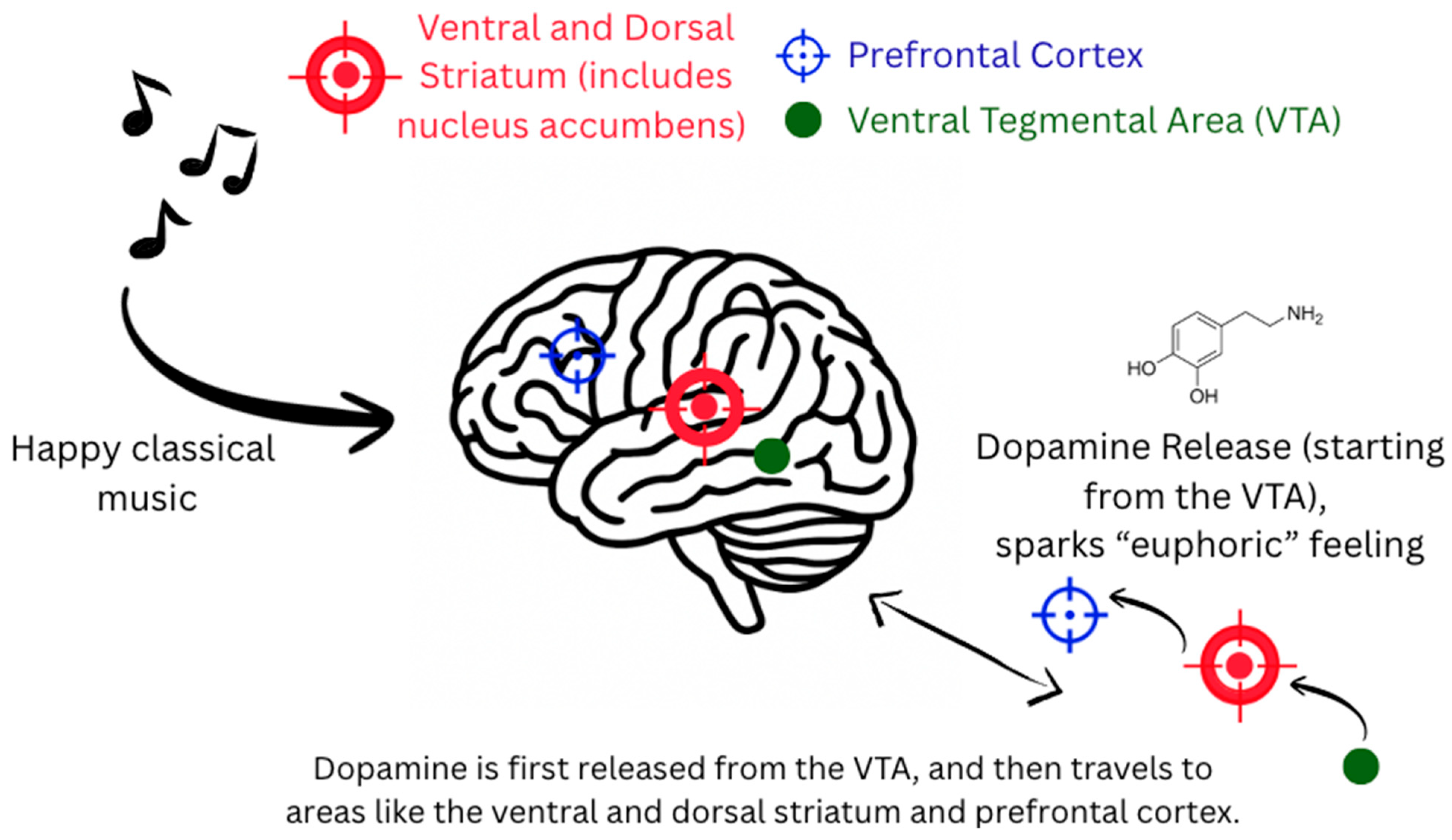

To illustrate the neural pathway by which music engages the brain’s reward system,

Figure 1 presents a simplified side-view diagram of the brain. When pleasurable music is perceived, auditory signals ultimately influence the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a midbrain structure that serves as the origin of dopamine release.

This supports the idea that happy classical music, by stimulating these regions, reinforces reward-driven behaviors and certain physical responses. The connection between happy music and reward in the brain is also reinforced by evidence regarding dopamine release in the ventral striatum [

5,

6]. The release of dopamine provides the basis for pleasurable emotions and a sense of reward from happy music, linking the experience of pleasure to the ventral and dorsal striatal activation. These discoveries regarding activations in the brain reward pathways reveal that happy classical music promotes both pleasure and motivation to move.

Happy classical music is also linked to pleasure-related reactions because it activates important areas of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). With functional MRI, Mitterschiffthaler et al. observed significant activation in the rostral pregenual and dorsal ACC when subjects listened to happy music: It has also been observed that happy music resulted in significant activation in the rostral pregenual and dorsal ACC, which regulates autonomic arousal, error monitoring, and conflict processing.5 The dorsal ACC is involved in goal-directed behavior and conflict monitoring. In contrast, the rostral pregenual ACC is involved in autonomic arousal, emotional regulation, etc. These regions integrate emotional and cognitive aspects of reward processing, highlighting how happy music can influence both emotional responses and physiological arousal. This activation supports the pleasurable experience associated with happy classical music by engaging multiple aspects of the nervous system linked to reward and positive emotions.

Research indicates that happy classical music triggers different physiological and neural responses than sad and fearful classical music. Baumgartner et al. found that happy and fearful classical music statistically increases respiration rates, while sad music does not [

1]. The evidence magnifies the effects of happy and fearful classical music on the body’s respiratory system in ways that sad music does not. Interestingly, other physiological differences arise in happy and sad music. Mitterschiffthaler et al. demonstrated that while happy classical music activates the ventral and dorsal striatum, sad music activates the amygdala and hippocampus (regions involved in processing threats and memories) [

5]. These results imply that happy music reflects high emotional arousal in the reward-related brain regions, as well as showing the contrast between the effects of happy and sad music.

Each study design has unique advantages, highlighting the multifaceted nature of music and emotion research. Fuentes-Sánchez and colleagues integrate subjective self-reports, facial expression analysis, and physiological recordings to capture temporal emotional reactions in detail [

3], while Vuust et al. employ the predictive coding of the music model to demonstrate how the brain continually anticipates and updates its expectations based on certain musical features [

7]. Mitterschiffthaler et al. harness functional MRI to distinguish the neural correlates of happy versus sad affective states, illustrating how specific classical pieces can shape distinct emotional outcomes [

5]. Likewise, Baumgartner and coauthors use EEG to compare how pictures and classical music evoke different stages of emotion perception and experience, offering insight into the unfolding of affective responses over time.

1 Finally, Blood et. al. connect intensely pleasurable “chills” with increased activity in dopamine-rich reward circuits, underscoring the powerful influence of music on core affective systems in the brain [

2].

While the understanding of how happy classical music triggers pleasure-related reactions in one’s nervous system has certainly advanced, several restrictions must be pointed out. One important restriction is the feasibility of specific tempo, pitch, and timbre variations [8]. For example, faster tempi in some happy pieces might have caused high levels of arousal regardless of any other possible factors. This can be resolved by choosing pieces with varied musical characteristics or using computer programs to create music that would not entail so many variations. In addition, some researchers believe that gender, personality traits, and age can affect study results [

5]. To yield accurate results, it would be helpful to use different groups of participants with uniform music examples to investigate how these factors affect the brain and the emotions among different subjects. Including these variables would make an inclusive viewpoint and make the findings more comprehensive.

Conclusions

Happy classical music distinctly impacts the nervous system, eliciting pleasurable responses including dopamine release, striatal activation, and changes in autonomic arousal. Studies consistently confirm that exposure to happy classical music activates the ventral and dorsal striatum, leading to dopamine release that underlies pleasure and reward-related behaviors. These reactions often differ from those triggered by sad or fearful music, demonstrating the unique power of happy music in enhancing emotional well-being. In contrast, sad music engages regions like the amygdala and hippocampus, eliciting different autonomic responses and underscoring happy music’s unique role in stimulating positive emotion and motivation. To deepen our understanding of this effect, future research should control for musical variables, such as tempo and pitch, and systematically examine individual differences, such as age and personality, thereby clarifying how happy music triggers these robust pleasure-related neural and physiological responses. These insights could help develop the future application of happy music in therapy.