Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Part I

2.1. Physics of the Two Fluids

- 1)

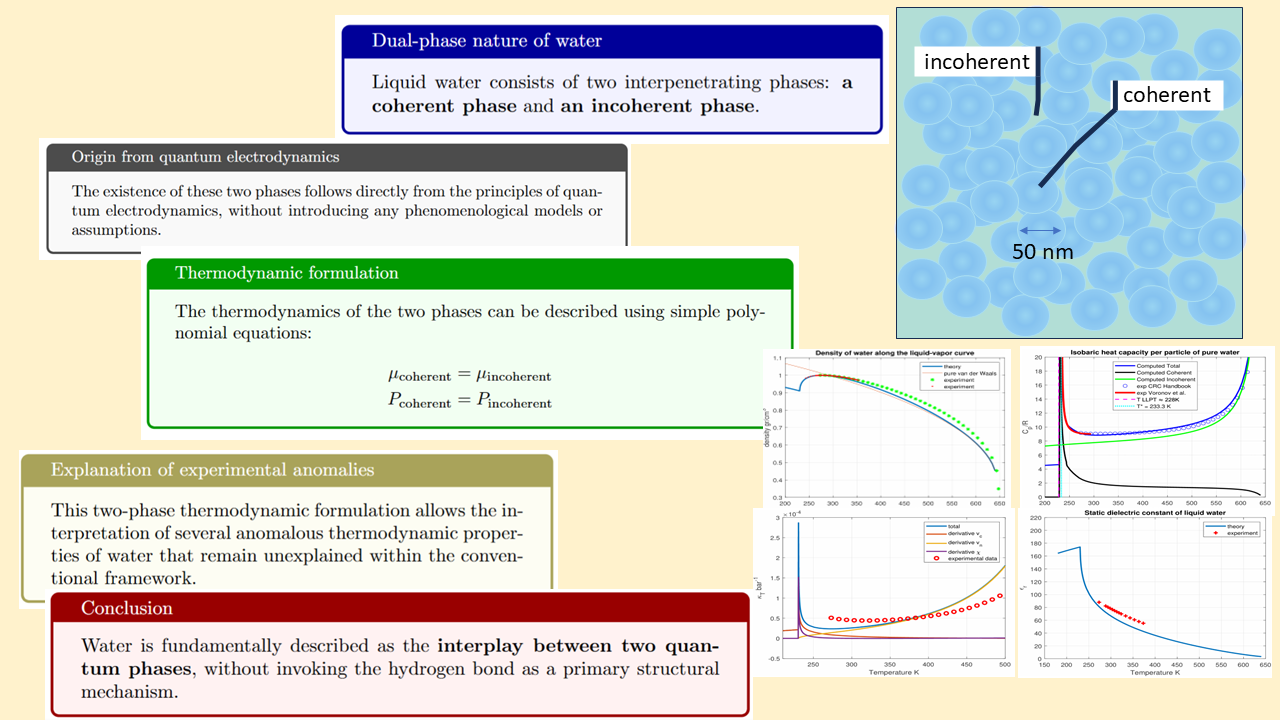

- Liquid water is composed by two different mixed fractions over the whole range of existence of the liquid: a coherent phase where molecules are phase-locked over an extended space-time region and a incoherent (or normal) phase made up of individual molecules forming a dense incoherent fluid. The two phases are interspersed and cannot be separated as in the case of the two-fluids model of superfluid 4He. As a general rule, the incoherent phase predominates at high temperatures and gradually decreases in favor of the coherent phase with decreasing temperature in a way that will be described in the following paragraphs.

- 2)

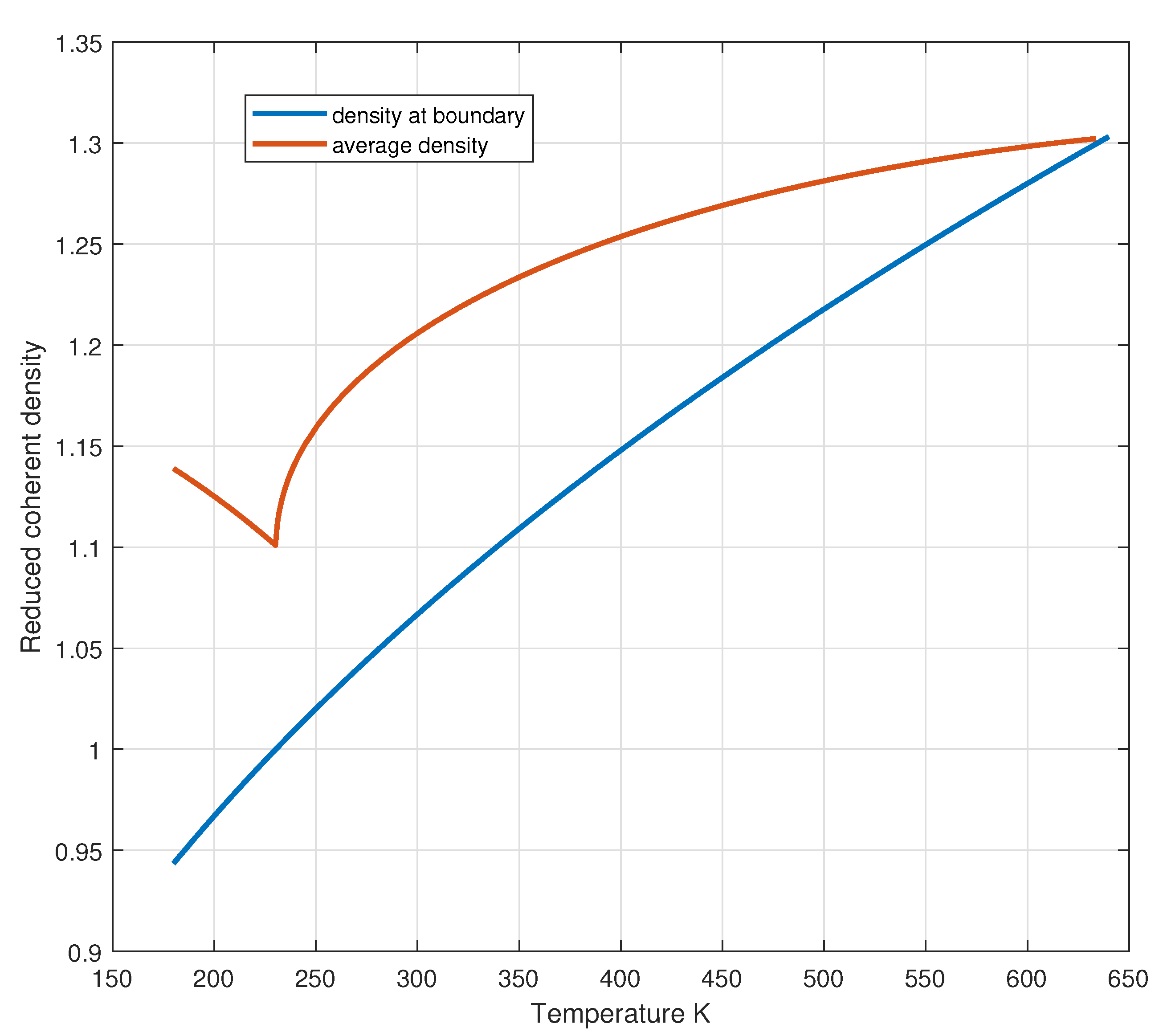

- The coherent phase is made up by an ensemble of Coherence Domains (CDs) that can be assumed as spheres whose radius depends on the temperature. The centers of the CDs are arranged in a regular configuration in order to minimize the energy of the system. When the temperature decreases, the CDs tend to increase their size until they merge into a single macroscopic domain for sufficiently low temperature. This may account for increased viscosity when temperature is decreased and may account for the glassy nature of supercooled water [16].

- 3)

- The molecules belonging to the coherent phase are energetically separated from the non-coherent phase by an energy gap, protecting them from the thermal fluctuations. The reason of the existence of an energy gap is due to a collective ground state different from the ‘perturbative’ ground state of the isolated molecules [11].

- 4)

-

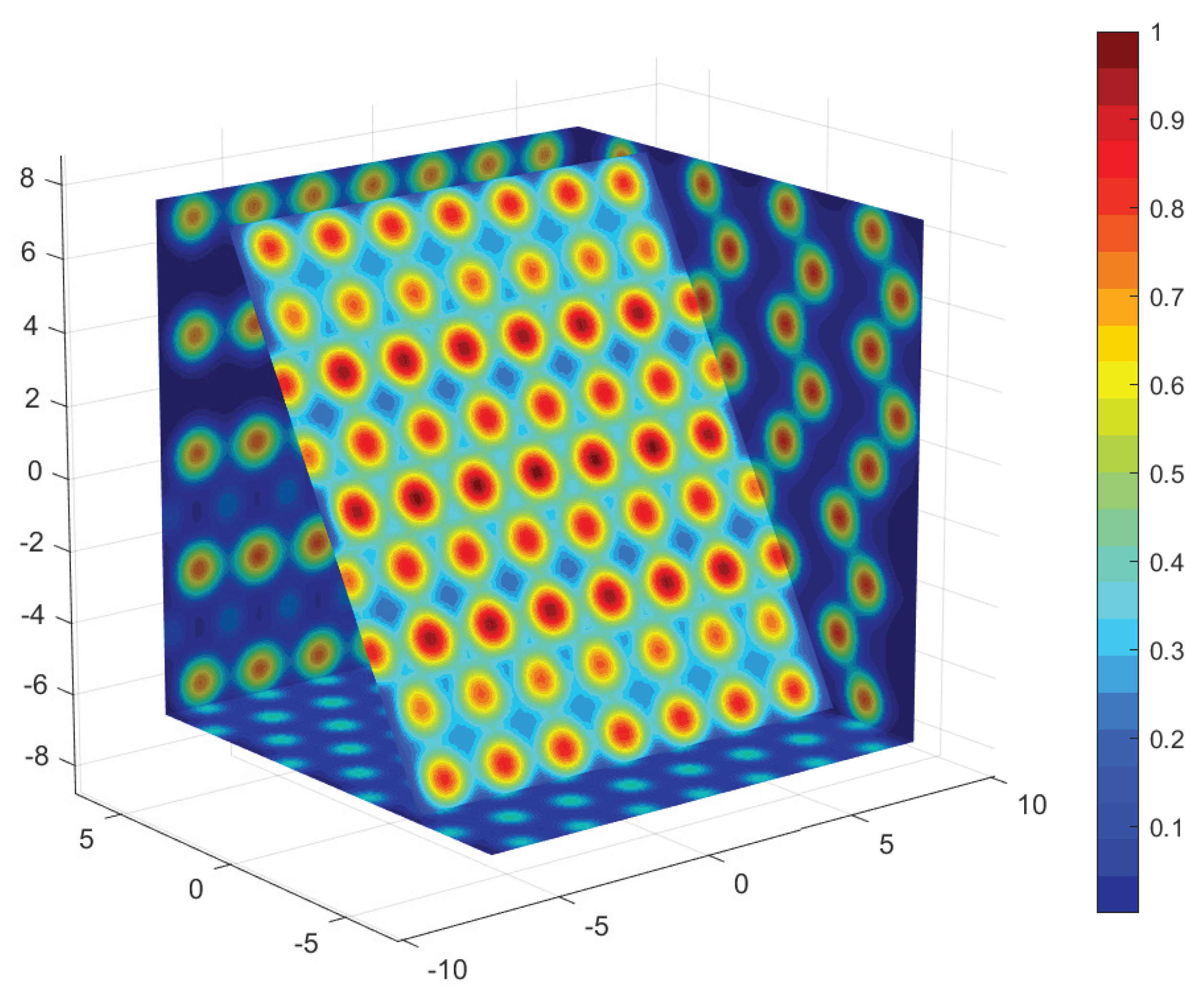

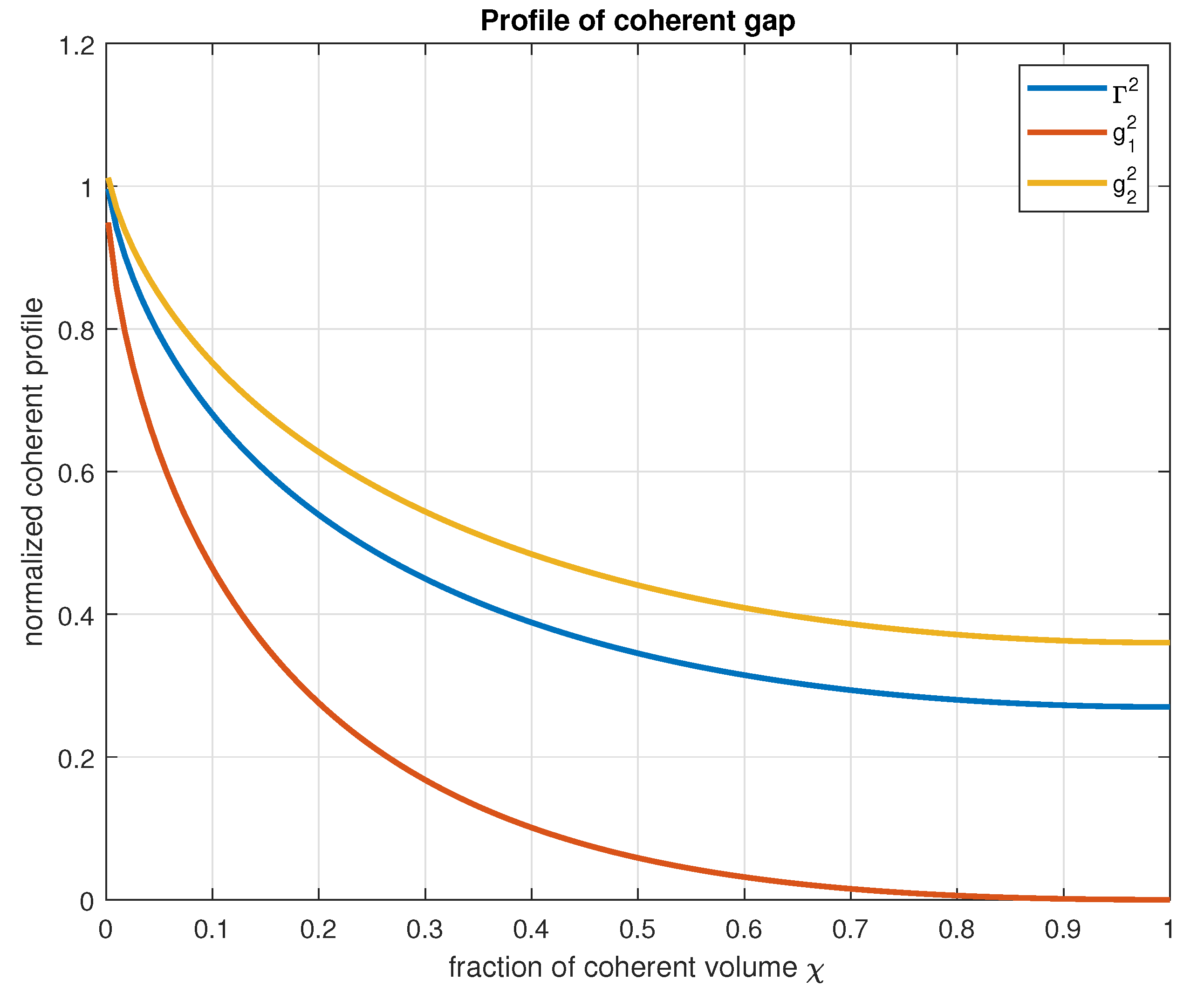

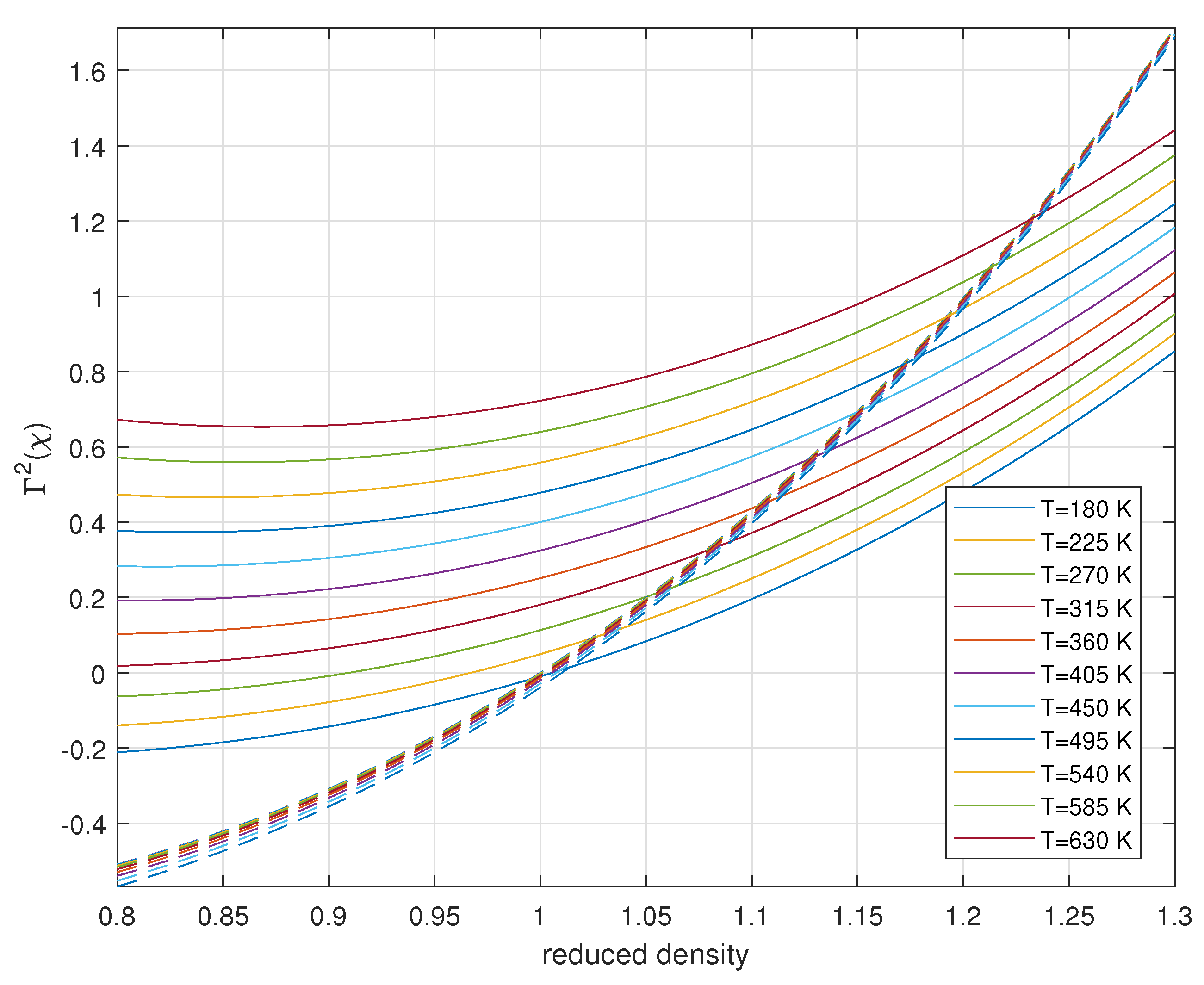

The single CD at zero temperature is characterized by a collective interaction among the water molecules through a macroscopic coherent electromagnetic field. These molecules are kept in phase by the electromagnetic field whose profile is given by [11]where , r is the radial distance from the center of the CD and 38 nm is the CD radius. The profile of the energy gap per particle for a single CD is given by , since the energy per particle is proportional to the square of the amplitude of the coherent electromagnetic field.In the bulk liquid composed by CDs, the profile of the energy gap at position is given bywhereand where are the positions of the CD centers.

- 5)

-

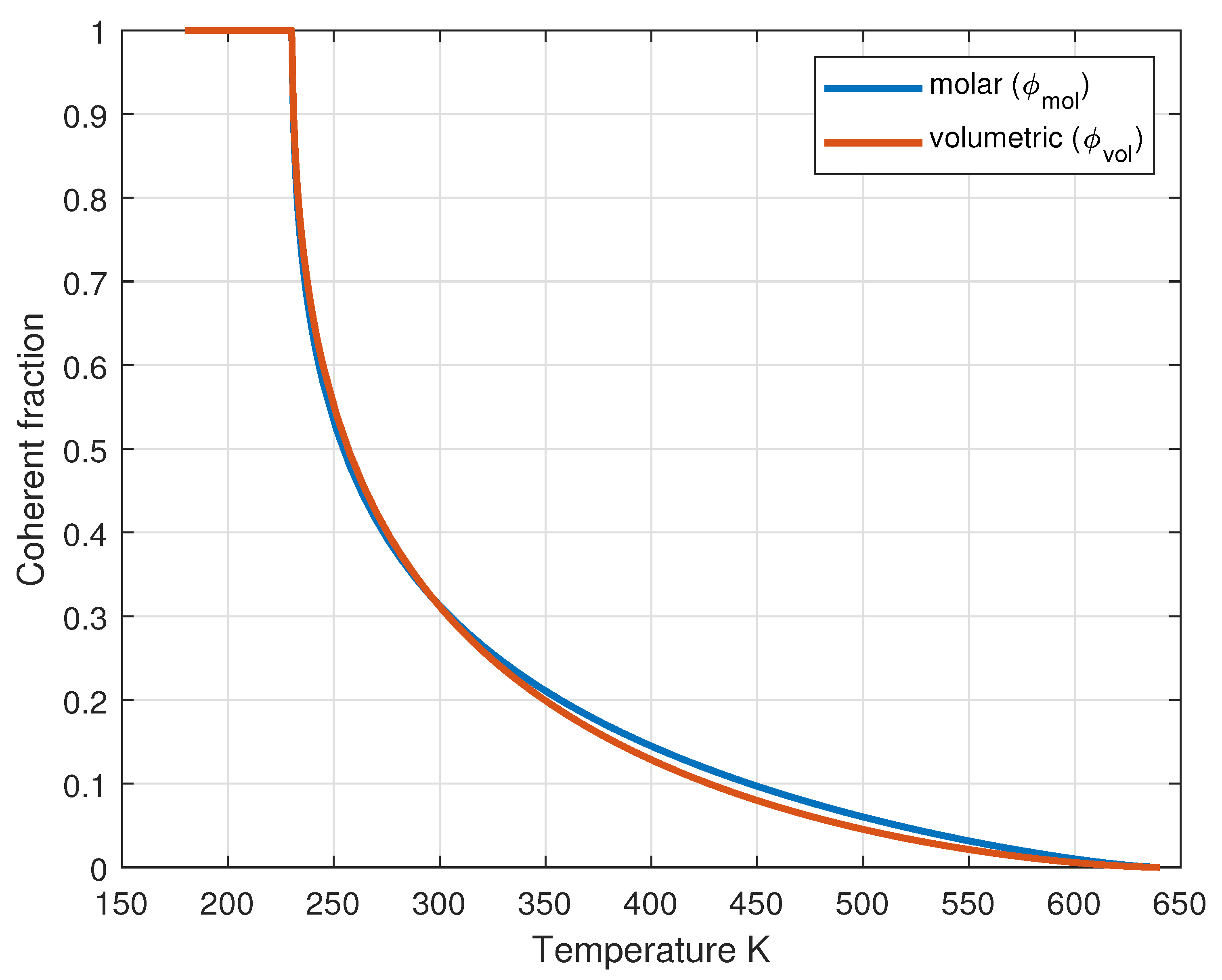

The CDs are arranged in a HPC configuration in order to minimize the total energy. As the temperature increases, the molecules belonging to the coherent state migrate towards the incoherent state, thus reducing the coherent fraction. A fluid of incoherent molecules is then formed which fills the interstices between the CDs and the size of the CDs gets reduced. It is worth noting that the arrangement of the CDs does not form a rigid crystal, as each CD can slide over the adjacent ones, separated by the incoherent fluid.

- 6)

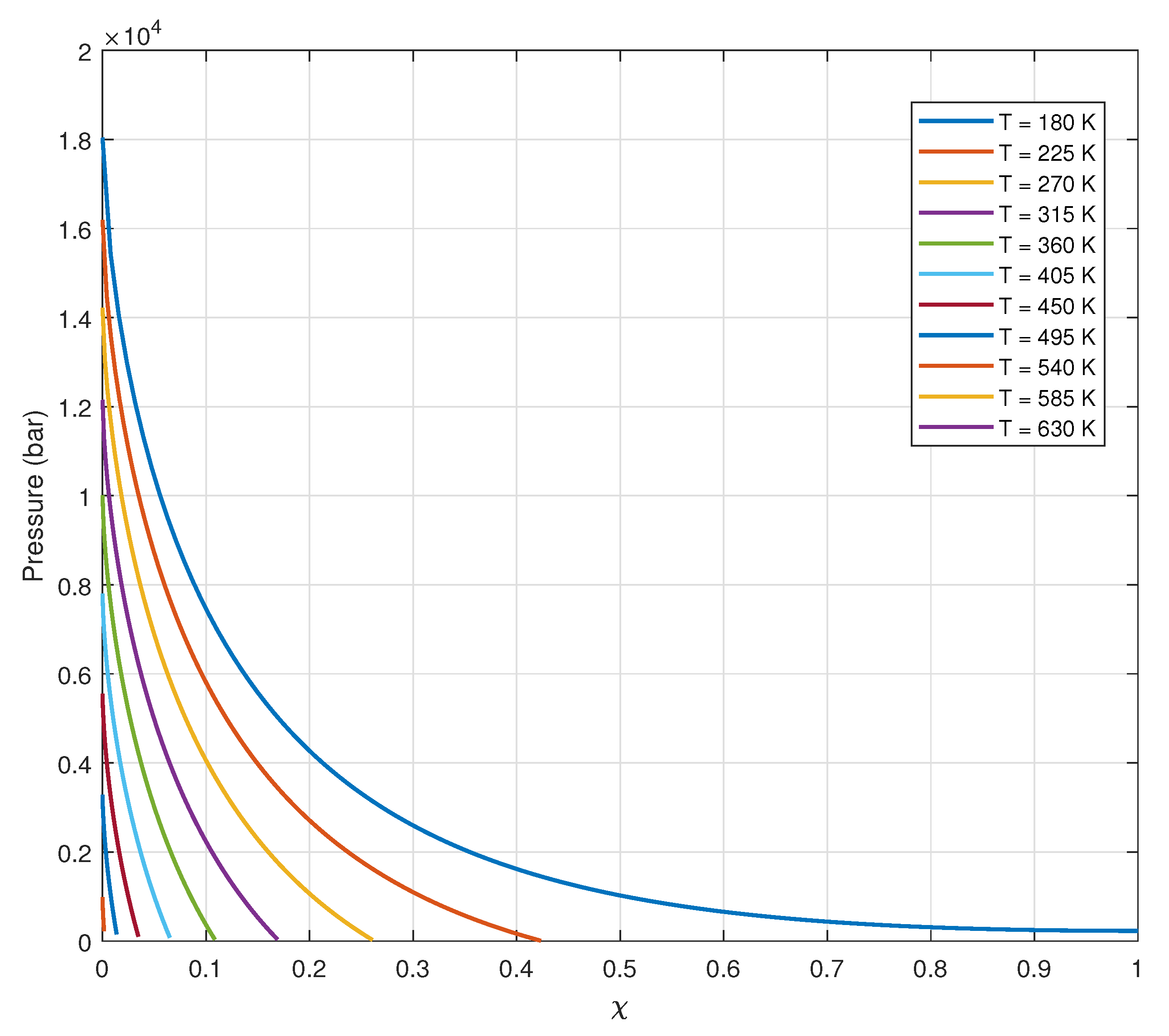

- At a fixed temperature T and pressure P the total number of molecules N can be written as , being the number of molecules in the coherent phase, the number of molecules in the incoherent phase and the number of molecules in the vapor phase.

- 7)

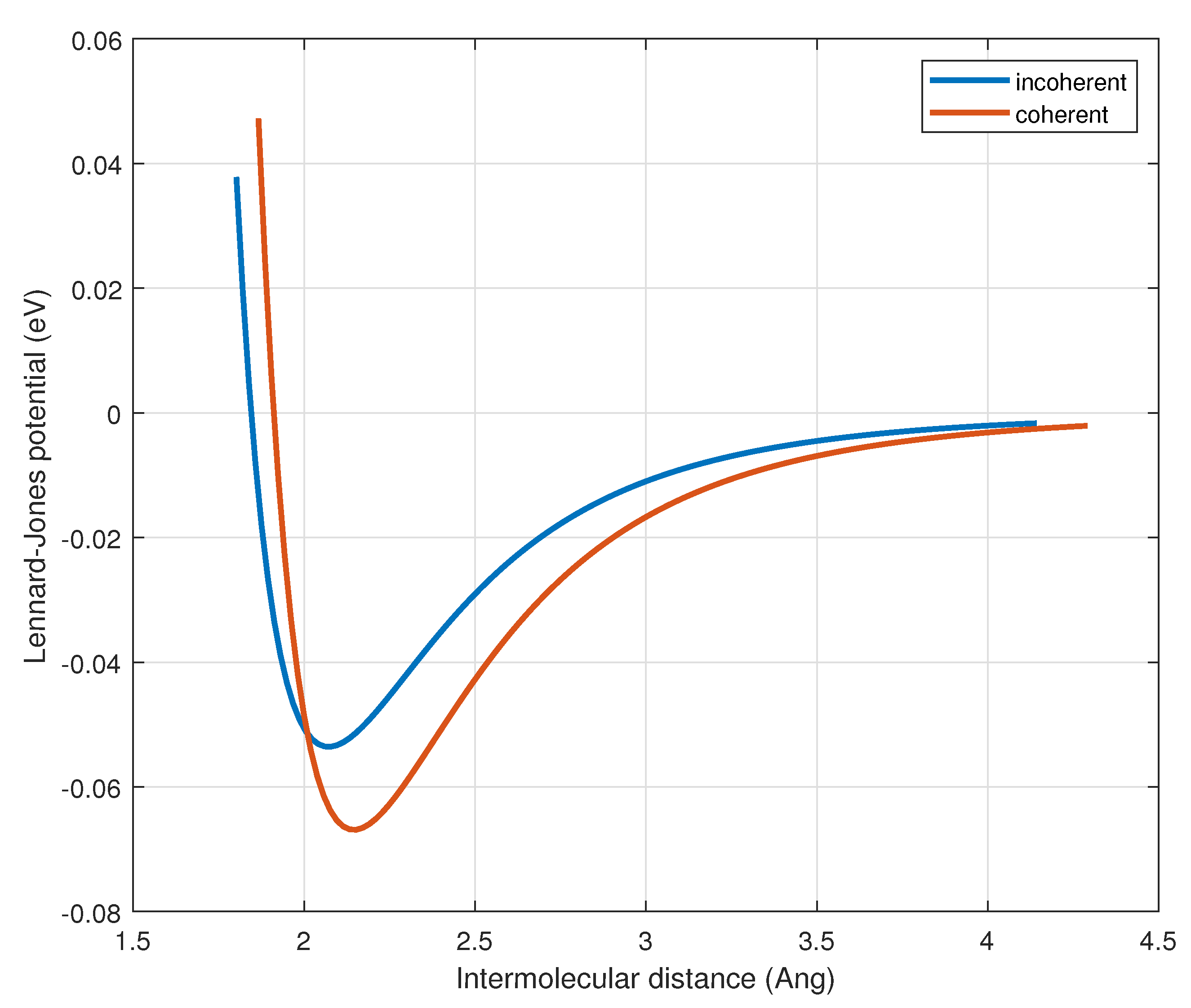

- The molecules belonging to the coherent phase are in an excited electronic state given by the superposition of the ground state and the 5d state corresponding to an energy of 12.06 eV according to the formulawith [11], whose energy gap is =-0.3 eV per molecule. Since the excited state is spatially quite more extended than the ground state , the intermolecular distance is larger than would be predicted from the standard molecular size. Furthermore, the new electronic configuration accounts for the tetrahedral coordination of the water molecules in the coherent phase. In Ref. [17] this problem has been thoroughly discussed. This fact implies that the water molecules in the coherent phase are arranged in an ice-like spatial configuration.

- 8)

- It is worth noting that the coherence involves the electronic levels and the only, so that the nuclei of the molecules are still able to perform vibrations but not rotations limited to small angles around the equilibrium directions defined by the H-bonds that, in this context, are determined by the modified electronic distribution of the coherent water molecules [17]. The kinetic contribution to the partition function of the coherent phase is therefore purely vibrational.

- 9)

-

The incoherent phase is treated as a polar fluid, where interactions are governed by a combination of the Lennard-Jones potential and dipole-dipole forces. It remains in thermodynamic equilibrium with the coherent phase, with which it continuously exchanges particles. A rigorous approach to describing the many-body interactions within the incoherent phase would involve applying the Bogoliubov diagonalization procedure, leading to a gas of quasi-particles and a phonon/roton-like interpretation. This approach would provide a detailed understanding of the thermodynamic properties of the incoherent phase, as well as the propagation of sound in liquid water.However, in this study, we approximate the incoherent phase as a vdW liquid, whose thermodynamic properties are well established. Although this approximation does not fully capture certain characteristics of liquid water, particularly the pressure-temperature coexistence curve, our primary goal is to demonstrate the qualitative explanatory power of our theoretical framework.

- 10)

- Solidification of liquid water (freezing) will not be taken into account in the present paper since it is related to the onset of a different type of electromagnetic symmetry breaking, leading to an energy gap of a different nature. The formation of ice will be the subject of a future work.

2.2. Definition of the Coherent Spatial Profile

2.3. Free Energy of the Coherent Fluid

2.4. Free Energy of the Incoherent Fluid

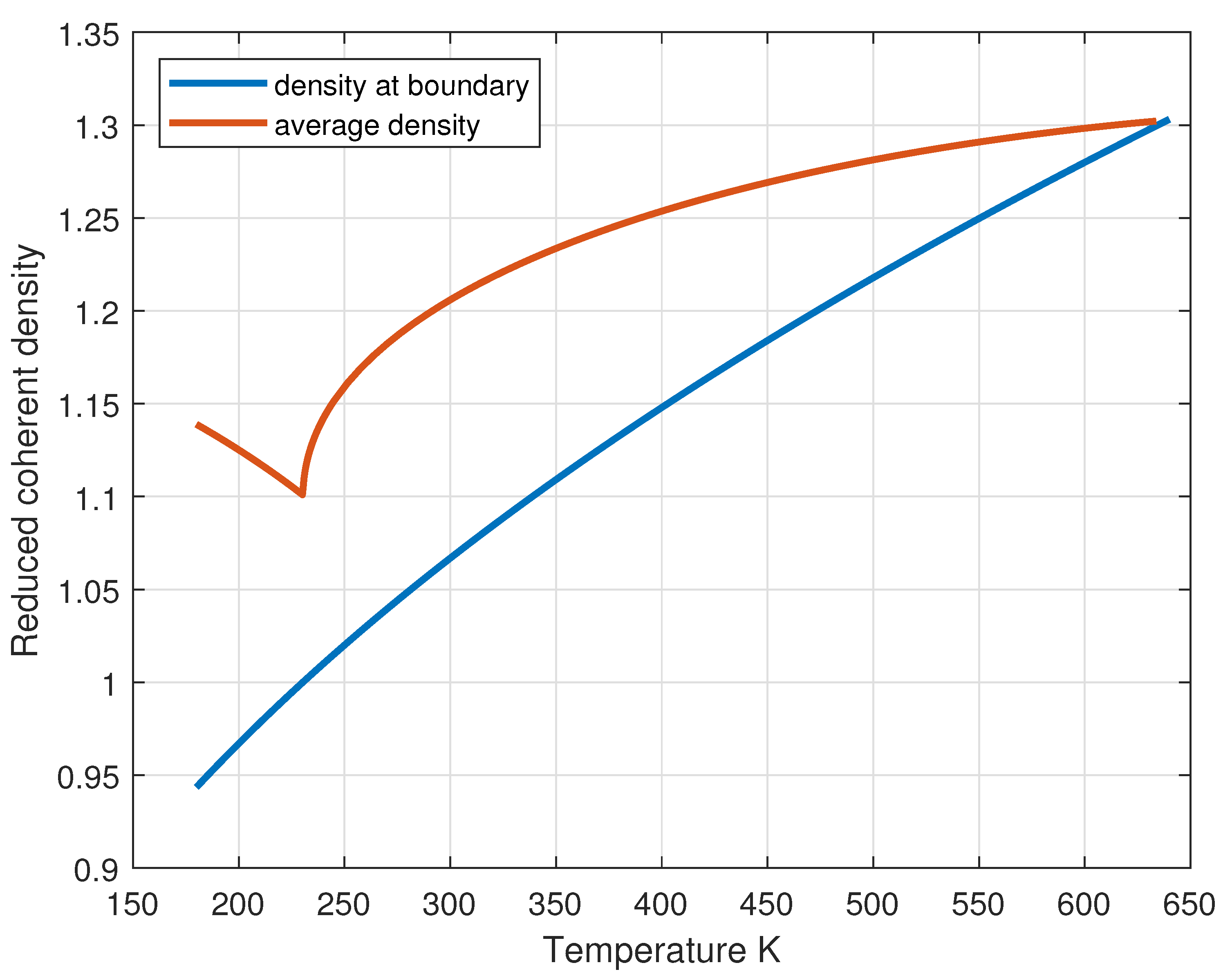

2.5. Solution of the Equilibrium Equations and Calculation of the Coherent Fraction

3. Part II

3.1. Thermodynamic Properties

3.2. Parameter Optimization

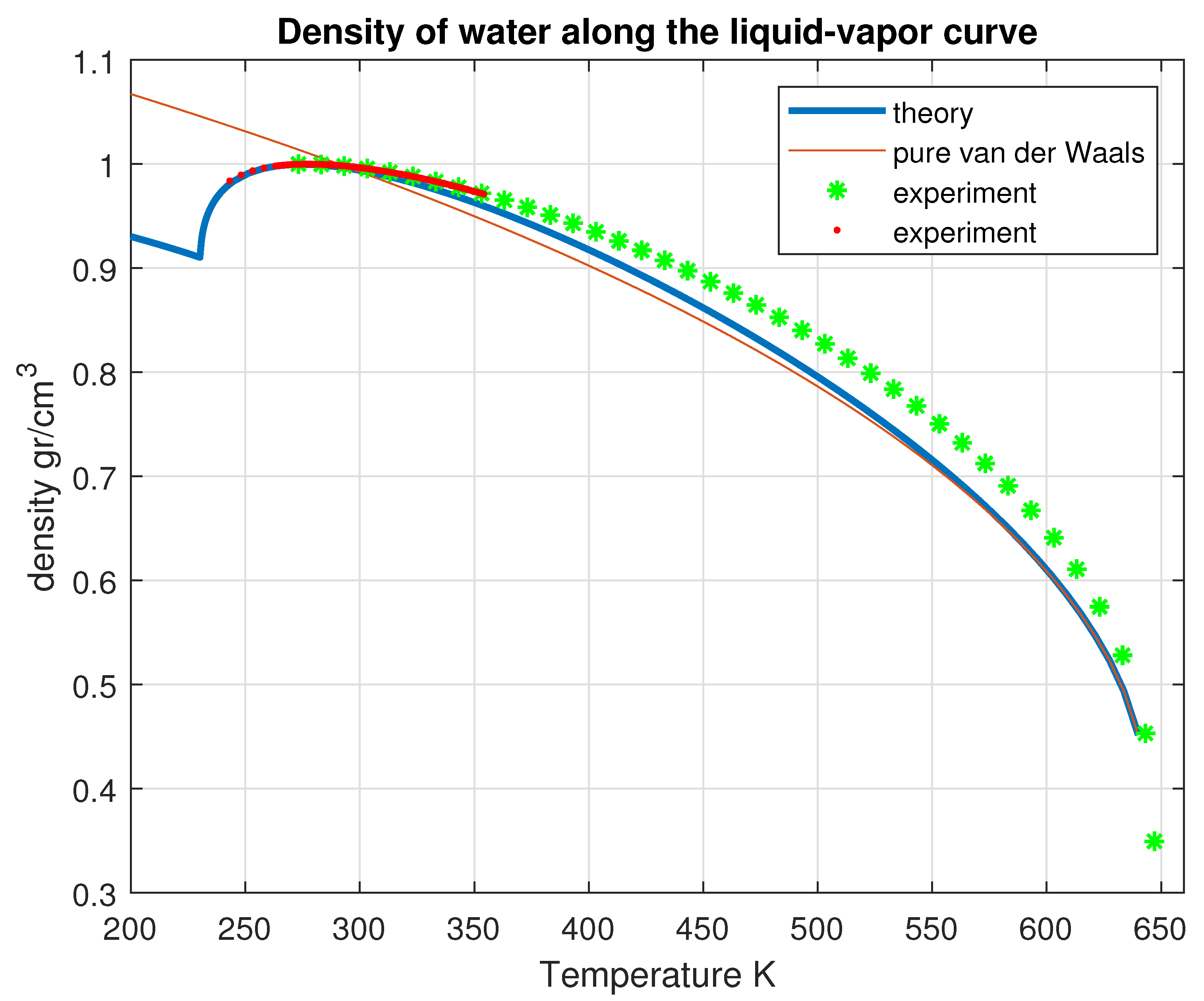

3.3. Density and Thermal Expansion Coefficient

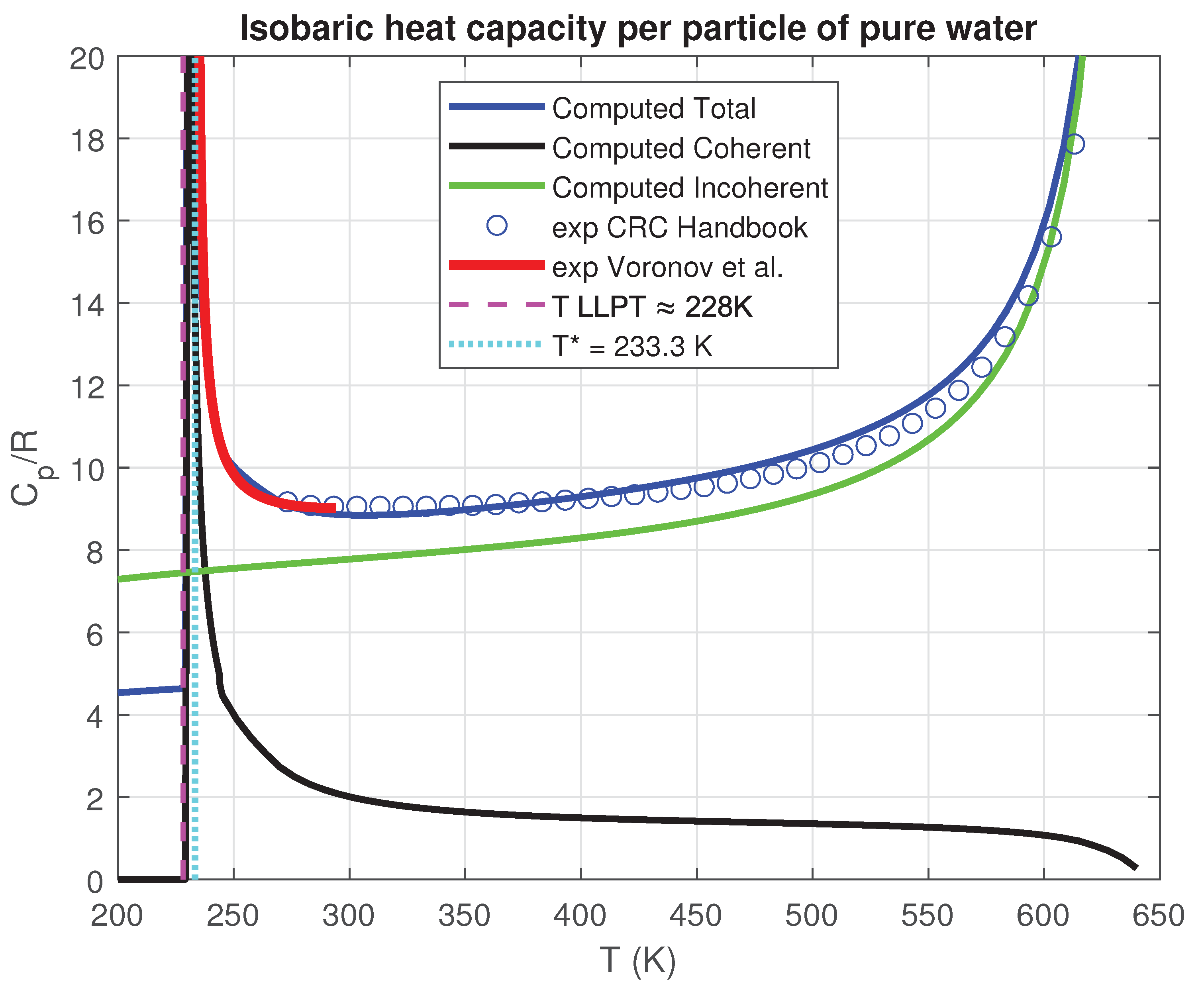

3.4. Isobaric Heat Capacity

3.5. Isothermal Compressibility

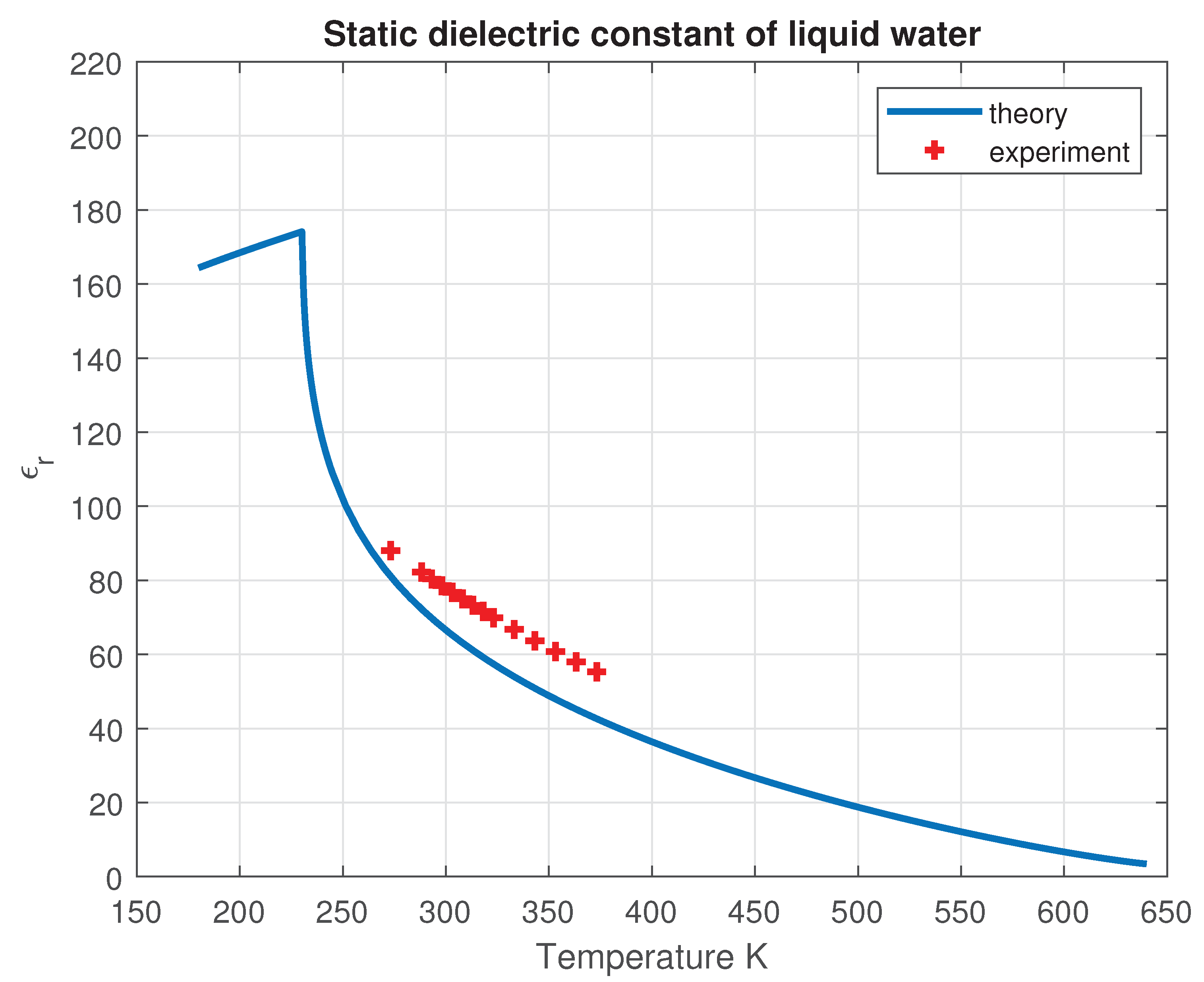

3.6. Static Dielectric Constant

3.6.1. Coherent Component of the Static Dielectric Constant

3.6.2. Evaluation of the Dielectric Constant

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- It elucidates the physical mechanisms underlying the formation and stability of the distinct liquid phases. The coherent low-density liquid (LDL) phase arises via spontaneous symmetry breaking of the electromagnetic field, resulting in macroscopic quantum domains with an average size of nm characterized by an energy gap and a spatial distribution described by the spherical Bessel function . The HDL phase, described as a polar van der Waals fluid, fills the interstices between domains. Our solutions quantitatively determine the relative abundances of these phases over a range of temperatures, reinterpreting the so-called liquid–liquid phase transition (LLPT) not as a true critical phenomenon, but rather as the temperature threshold—upon cooling—at which the incoherent phase (HDL) vanishes.

- The theory offers a first-principles explanation for several of water’s most perplexing anomalies. The well-known density maximum at 277 K emerges from the competition between the volumetric expansion of LDL domains and the densification of the HDL phase. The observed minimum in the isobaric heat capacity near 309 K reflects a balance between the stabilization of the coherent phase and thermal excitation. Most notably, the model accounts for the sharp divergence in thermodynamic behavior near 228 K as a consequence of the complete disappearance of the HDL fraction.

- The theory resolves the longstanding quantum–classical duality exhibited by water. Below approximately 320 K, the system demonstrates macroscopic quantum coherence through extended networks of coherence domains, while simultaneously retaining classical fluidity through the intervening HDL phase. As temperature increases, the coherent fraction diminishes, leading to the gradual loss of quantum coherence and explaining the crossover to purely classical behavior near the critical point.

References

- Röntgen, W.C. Ueber die Constitution des flüssigen Wassers. Annalen der Physik 1892, 281, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, E.; Preparata, G.; Vitiello, G. Water as a free electric dipole laser. Physical Review Letters 1988, 61, 1085–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preparata, G. QED Coherence in Matter; World Scientific, 1995.

- Poole, P.H.; Sciortino, F.; Essmann, U.; Stanley, H.E. Phase behaviour of metastable water. Nature 1992, 360, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, O.; Stanley, H.E. The relationship between liquid, supercooled and glassy water. Nature 1998, 396, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernet, P.; Nordlund, D.; Bergmann, U.; Cavalleri, M.; Odelius, M.; Ogasawara, H.; Naslund, L.A.; Hirsch, T.K.; Ojamae, L.; Glatzel, P.; et al. The structure of the first coordination shell in liquid water. Science 2004, 304, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wikfeldt, K.T.; Tokushima, T.; Nordlund, D.; Harada, Y.; Bergmann, U.; Niebuhr, M.; Weiss, T.M.; Horikawa, Y.; Leetmaa, M.; et al. The inhomogeneous structure of water at ambient conditions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 15214–15218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taschin, A.; Bartolini, P.; Eramo, R.; Righini, R.; Torre, R. Evidence of two distinct local structures of water from ambient to supercooled conditions. Nature communications 2013, 4, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, I.; Del Giudice, E.; Gamberale, L.; Henry, M. Emergence of the Coherent Structure of Liquid Water. Water 2012, 4, 510–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, P.; Amann-Winkel, K.; Angell, C.A.; Anisimov, M.A.; Caupin, F.; Chakravarty, C.; Lascaris, E.; Loerting, T.; Panagiotopoulos, A.Z.; Russo, J.; et al. Water: A Tale of Two Liquids. Chemical Reviews 2016, 116, 7463–7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arani, R.; Bono, I.; del Giudice, E.; Preparata, G. QED coherence and the thermodynamics of water. International Journal of Modern Physics B 1995, 9, 1813–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninno, A.D.; Giudice, E.D.; Gamberale, L.; Castellano, A.C. The Structure of Liquid Water Emerging from the Vibrational Spectroscopy: Interpretation with QED Theory. Water 2014, 6, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice, E.; Vitiello, G. The role of the electromagnetic field in the formation of domains in the process of symmetry breaking phase transitions. Physical Review A 2006, 74, 022105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ninno, A.; De Francesco, M. Water molecules ordering in strong electrolytes solutions. Chemical Physics Letters 2018, 705, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majolino, D.; Mallamace, F.; Migliardo, P. Spectral evidence of connected structures in liquid water: Effective Raman density of vibrational states. Physical Review E 1993, 47, 2454–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzacchi, M.; Del Giudice, E.; Preparata, G. Coherence of the Glassy State. International Journal of Modern Physics B 2002, 16, 3771–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, E.; Galimberti, A.; Gamberale, L.; Preparata, G. Electrodynamical Coherence in Water: A Possible Origin of the Tetrahedral Coordination. Modern Physics Letters B 1995, 09, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.C. Advances in Thermodynamics of the van der Waals Fluid; 2053-2571; Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.K.; Clary, D.C.; Liu, X.; Brown, M.; Saykally, R.J. The water dipole moment in water clusters. Science 1997, 275, 814–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, W.M. (Ed.) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Voronov, V.P.; Podnek, V.E.; Anisimov, M.A. High-resolution adiabatic calorimetry of supercooled water. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2019, 1385, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Pettersson, L. The structural origin of anomalous properties of liquid water. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ninno, A.; Nikollari, E.; Missori, M.; Frezza, F. Dielectric permittivity of aqueous solutions of electrolytes probed by THz time-domain and FTIR spectroscopy. Physics Letters A 2020, 384, 126865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1998; See Chapters 4 and 8 for detailed discussion on dielectric polarization and the Langevin function. [Google Scholar]

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Spectral weight | Energy (meV) |

|---|---|---|

| 52 | 0.61 | 6.5 |

| 161 | 4.39 | 20 |

| Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| electric dipole for vapor | 1.84 | D |

| mass of water molecule | eV | |

| 0.0554 | eV | |

| (fit parameter) | ||

| reference coherent density (fit parameter) | ||

| coherent energy gap (fit parameter) | eV | |

| (fit parameter) | 0 | - |

| (fit parameter) | 0.2 | eV |

| (fit parameter) | 0.066 | eV |

| eV | |

|---|---|

| 7.400 | 0.0500 |

| 9.700 | 0.0732 |

| 10.000 | 0.0052 |

| 10.170 | 0.0140 |

| 10.350 | 0.0107 |

| 10.560 | 0.0092 |

| 10.770 | 0.0069 |

| 11.000 | 0.0218 |

| 11.120 | 0.0223 |

| 11.385 | 0.0098 |

| 11.523 | 0.0086 |

| 11.772 | 0.0178 |

| 12.074 | 0.0101 |

| 12.243 | 0.0053 |

| 12.453 | 0.0025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).