1. Introduction

A classical problem in the theory of particle physics is the problem how to give an explanation for the quantitative value of the mass of the electron. One of the first scientists who struggled with the problem was Hendrik Lorentz. He and others (Abraham and Poincaré) tried to tackle the problem by assuming that the mass of the electron had to be conceived as the energy stored in its electric field [

1]. Unfortunately, he ran into problems because of two problems:

Infinte self-energy due to:

Stability problem:

A charged sphere should blow itself apart due to the repulsion of its own charge. What holds it together? Lorentz (and Poincaré) postulated mysterious “Poincaré stresses” — hypothetical forces to keep the charge from exploding. While he didn’t have the final answer, Lorentz showed deep insight into this puzzle. In 1904, he wrote [

2]:

“One cannot help thinking that the whole inertia of matter is of electromagnetic origin.”

So, Lorentz hoped that all of an electron’s mass could be explained electromagnetically — no extra “mechanical” mass needed.

In 1926 Paul Dirac formulated his ground-breaking theory on the electron that eventually led to the development of Quantum Electro Dynamics (QED). Dirac knew that an electron interacting with its own electromagnetic field leads to infinite self-energy, just like Lorentz found in classical theory. Dirac was the first to grapple with this in a quantum context:

- -

In QED, an electron constantly emits and reabsorbs virtual photons.

- -

These interactions shift the electron’s mass to infinity unless you use renormalization — a process to systematically subtract the infinities.

Dirac found this idea disturbing. He famously said [

3]:

“I must say that I am very dissatisfied with the situation, because this so-called ‘infinity’ is something which we do not understand.”

To the end of his life, Dirac criticized mainstream quantum field theory for its dependence on renormalization, which he saw as a patch rather than an explanation.

In the present canonical theory of particle physics, known as the Standard Model, renormalization is one of the pillars. The electron mass is taken as a phenomenological fundamental parameter.

- -

It arises from how the electron interacts with the Higgs field,

- -

The Yukawa coupling (strength of interaction with the Higgs) sets the electron’s mass.

Formally, the massive energy

of the electron in its rest frame is expressed as [

4],

in which

GeV is the vacuum expectation value of the Higgs field.

Why the coupling has the specific value that sets the rest mass of the electron to 0.511 MeV/c2 is unknown. It is still an open question in physics.

It means that any theory that claims to have an answer on the puzzle is worthwhile to be considered. In this article I wish to show that the answer of the classical electron mass problem can be found in a structural view on particle physics, such as described in earlier work and summarized in [

5,

6].

2. Structural Model for the Pion

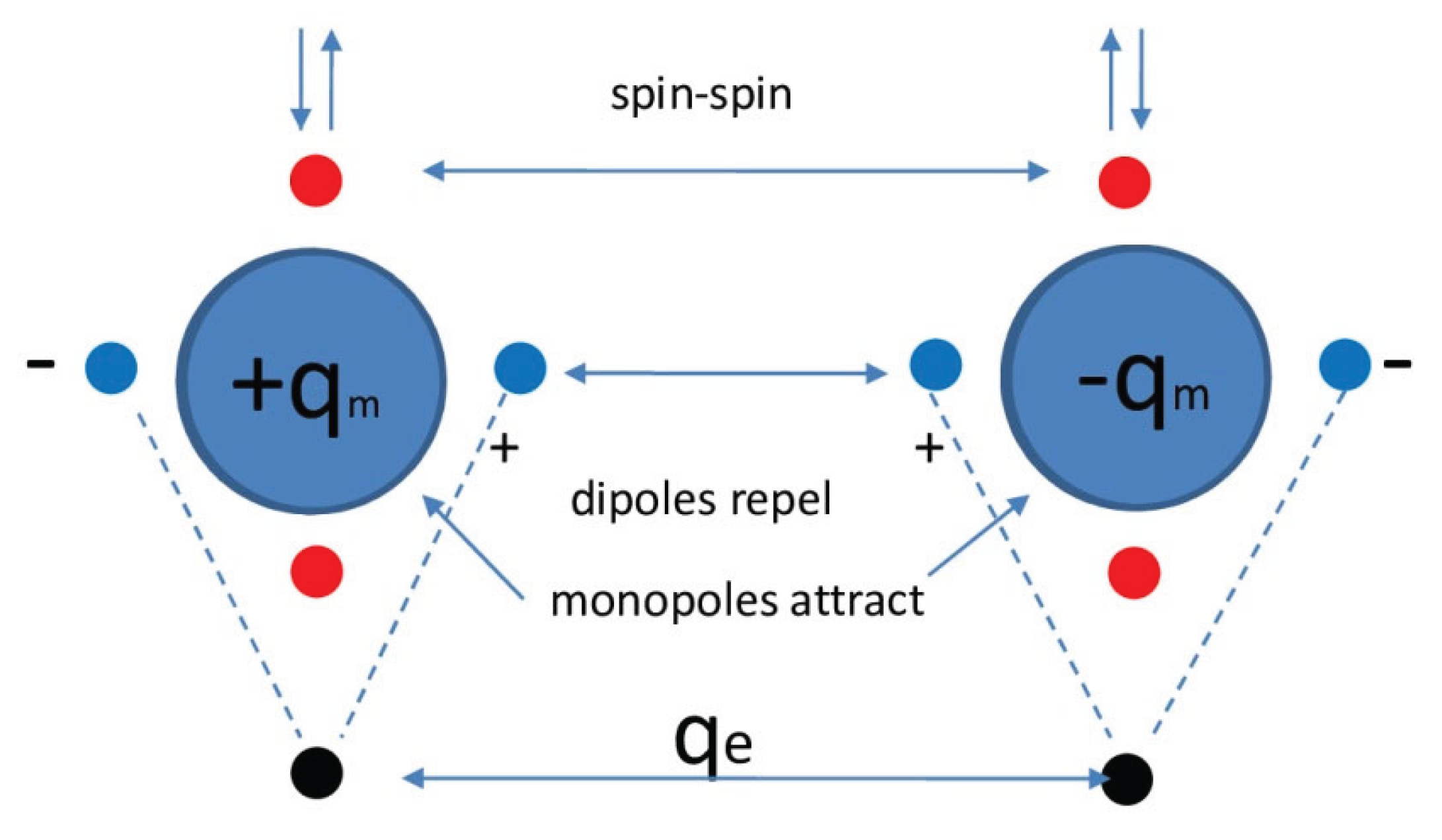

Figure 1 is an illustration of the structural model for a pion as developed by the author over the years [

4]. It shows that two quarks are structured by a balance of two nuclear forces and two sets of dipoles. The two quarks are described as Dirac particles with two real dipole moments by the virtue of particular gamma matrices. The vertical one is the equivalent of the magnetic dipole moment of an electron. The (real valued) horizontal dipole moment is the

real equivalent of the (

imaginary valued) electric dipole moment of an electron [

7,

8].

In a later description, after recognizing that this structure shows properties that match with a Maxwellian description, the quarks have been described as magnetic monopoles in Comay’s Regular Charge Monopole Theory (RCMT) [

9,

10]. This allows to give an explanation of the quark’s electric charge by assuming that the quark’s second dipole moments (the horizontal ones) coincide with the magnetic dipole moments of electric kernels

. This description allows to conceive the nuclear force as the cradle of baryonic mass (the ground state energy of the created anharmomic oscillator) as well as the cradle of electric charge.

The model allows a pretty accurate calculation of the mass spectrum of mesons. It also allows the development of a structural model of baryons including an accurate calculation of the mass spectrum of baryons as well. This calculation relies upon the recognition that the structure can be modeled as a quantum mechanical anharmonic oscillator. Such anharmonic oscillators are subject to excitation, thereby producing heavier hadrons with larger (constituent) masses of their constituent quarks. The increase of baryonic energy under excitation is accompanied with a loss of binding energy between the quarks. This sets a limit to the maximum constituent mass value of the quarks. It is the reason why quarks heavier than the bottom quark cannot exist and why the topquark has to be interpreted different from being the isospin sister of the bottom quark [

4].

The structural model is a two-body quantum mechanical oscillator that in the rest frame of the pion can be described in terms of the quantum mechanical wave equation

for its center-of-mass,

In which is Planck’s reduced constant, 2 the kernel spacing, is the effective mass of the center, its potential energy, and the generic energy constant, which is subject to quantization. By convention, the coupling factor in the context of the Structural Model has been defined as the square root of the electromagnetic fine structure constant as . The potential energy can be derived from a potential . Similarly as in the case of the pion quarks, this potential is a measure for the energetic properties of the kernels. It characterized by a strength (in units of energy) and a range (in units of length: the dimension of is [m-1]).

The potential

of a pion quark has been determined as,

This potential function for a quark is made up along the spatial axis of the quark’s real dipole moment by a classical potential and a dipole moment potential . The quark’s potential is shielded by as a consequence from an ambient energetic fielded. The functional equivalent of this spatial field shows similar characteristics as the heuristic Higgs potential in the Standard Model, which is attributed to Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking. In the interpretation shown by (4) the symmetry breaking of a classical potential is attributed to the ambient energy field and the influence of the non-angular dipole moment shown by a uncommon mode of the gamma matrices in Dirac’s equation for fermions. These features were unknown at the time of the Standard Model’s conception .

A binomial expansion of the potential energy

allows to rewrite the wave equation as,

The quantum wave equation can be normalised to the simple form by

in which

,

,

,

The oscillator settles into a minimum energy state at

. At this setting we have

Using the potential function (2), a little algebra reveals the simple relationships,

Note: is the natural logarithm constant.

In the oscillator models the spatial dimensions are normalized such that the spacing between the quarks in the state of minimum energy . The normalizing spatial parameter is closely related with the energy of the Higgs boson as . This normalization gives a gyrometric value .

The

parameter shown in (6) can be written as [

5],

It shows that the bond between the two quarks is maintained under influence of weak interaction embodied by the weak interaction boson GeV. In the table the parameters of the pion oscillator have summarized.

All this is a concise description of the pion’s behavior conceived in a structural interpretation of the theory of particle physics as an alternative, if not equivalent, for the canonical Standard Model. Note that

relates the oscillator

boson with the weak interaction boson

. The constant term

in the normalized potential

is a measure for the binding energy

. Because the pion decays under emission of the weak interaction boson

, this boson can be interpreted as the relativistic state of the rest mass energy

of the pion. This energy is built up as the sum of the binding energy of the oscillator and the ground state energy. In a harmonic oscillator the two contributions would be the same. In the anharmonic pion oscillator, oscillating at

, the two contributions are different, but nevertheless constituting a sum

. It explains that whereas a harmonic oscillator would show the binding energy [

6],

The anharmonic pion oscillator, while oscillating at

, shows,

Table 1.

Explicit expressions for the parameter values of the muon oscillator and the pion oscillator.

Table 1.

Explicit expressions for the parameter values of the muon oscillator and the pion oscillator.

| property |

parameter |

pion |

| quantum mechanical coupling factor |

|

|

| gyrometric ratio |

|

|

| normalizing spacing parameter |

|

|

| spacing for minimum energy |

|

|

| constant term potential energy |

|

|

| quadratic term potential energy |

|

|

|

|

|

| oscillator constant |

|

|

| mass relationship |

|

|

| mass curve |

|

|

3. The Birth of the Elementary Electric Charge

The key for solving the classical problem of the mass of the electron is based upon two unrecognized properties of a quark. That the quark is a Dirac particle of a kind as described in Dirac’s classical theory of electrons is commonly taken for granted. Dirac’s theory allows different choices for the canonical gamma matrix coefficients in the quantum mechanical wave equation. A well-known example is the Majorana variant. The Structural Model of particle physics has been based upon another variant. Unlike the electron-type, that variant shows two anomalous real dipole moments (the common angular one and an uncommon non-angular one) instead of a real one next to an imaginary one. Next to this feature, the quark has been described as non-electromagnetic Maxwellian monopole. As noted before,

Figure 1 shows the bond between a quark and an antiquark. The energy of its center-of-mass is the cradle of baryonic energy. And, recognizing that the non-angular dipole moment may represent the angular dipole moment of an electric kernel makes this bond the cradle of electric energy as well. As I wish to show, it is this view that will allow the calculation of the mass attribute of the elementary amount of electric charge.

4. The Mass of the Electron

(Note: the major part of the text in this paragraph is inherited from [

6])

Because the angular dipole moment of each electric kernel has the character of conventional angularly induced spin, the sign of the electric charge has an ambiguous value. It can be either positive or negative. Although the orientation of the non-angular dipole moment of the quark is imposed by the stability condition of the structure, its inherent statistical properties are the same as those of conventional spin. It is fair to say that this mechanism can be identified as the isospin attribute of the quark. In the canonical Standard Model, this isospin attribute was simply defined axiomatically, without any physical explanation. We can learn more about this explanation of the origin of electric charge by studying the quark in confinement with another quark. It suffices to add an electric component to the force derived from the far-field component of the interquark potential, so that

where

for mesons. This numerical value is derived from an assumed uniform charge distribution along the dipole axis. Taking into account the electromagnetic fine structure expression

, this leads to a modification of the far field such that

The potential

of the field built up by the quarks felt by the centre of mass, expanded along the dipole axis, is now built up by the near-field

from the dipole moment, the far-field

component of the weak interaction and the electromagnetic potential

such that

Taking into account the relationship the binding energy expression (11), we have,

The potential

of the field built up by the quarks felt by the centre of mass, expanded along the dipole axis, is made up of the near field

from the dipole moment, the far field

component of the weak interaction and the electromagnetic potential

such that

So, the constants

and

are modified so that

It are these two expressions allow the assignment of an energetic massive value to the elementary electric charge that is carried by the charged pion. The charge share

in the pion energy consists of two contributions. The electric charge energy

due to

is a fraction of the pion’s massive energy. Hence,

The electric charge energy

due to

is a fraction of the pion’s binding energy. Hence, from (18) and (11),

Taking the two contributions together, we have

The massive energy of the elementary electric charge can now be related with the rest mass of the pion as,

Invoking the parameter values shown in the table, we conclude

derived from first principles of the Structural Model of particle physics. It’s the amount of baryonic mass that can be assigned to the electron, that next to a neutrino, is the final decay product of the pion.

It has to be emphasized here that this massive energy of the elementary electric charge is different from the mass difference between a charged pion and a neutral pion. As discussed in [

4], that mass difference is determined by the influence of the electric charge on the spacing between the

monopoles in the pion structure. The massive energy calculated in this paragraph, though, is the pure energy embodied by the two dipole kernels that compose the elementary charge borne in the cradle of the pion structure.

5. Discussion

In this calculation the rest mass of the pion has been taken as reference. Of course, the pion mass on its turn may be brought in relationship with other quantum physical quantities. But in the end a reference is needed anyway. In the Structural Model of particle physics, the pion rest mass has appeared as being the most effective one. The capabilities in the Standard Model for calculating mass attributes of nuclear particles are not very impressive and are mostly stand-alone for particle-categories without showing the mass relationships between mesons, baryons and leptons. The present instrument, known as lattice QCD, needs references as well. The mass of quarks would be the most appealing one. And indeed, lattice QCD pretends being able to adopt the quark’s masses as the basic reference. A close inspection, though, reveals that the reference values are derived from empirically established values of the pion mass and the kaon mass [

11]. Whether the lattice QCD instrument is powerful enough to challenge the result shown in this article is doubtful. Probably no attempts will be made, because the mass of the electron is in the Standard Model accepted as empirical data of an elementary particle.

References

- Lorentz, H.A. 1952: The Theory of Electrons and Its Applications to the Phenomena of Light and Radiant Heat, 2nd Ed., Dover Publ. Inc.

- Lorentz, H. A. 1904: Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity less than that of light, Proc. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 6: 809–831.

- Dirac, P.A.M. 1973 The Physicist’s Conception of Nature, p. 19, Boston, Reidel ISBN 9027703450.

- Thomson, M. (2013), Modern Particle Physics, ch.9, Cambridge Univ. ISBN: 9781107034266.

- Roza, E. 2023: From black-body radiation to gravity: why quarks are magnetic electrons and why gluons are massive photons, J. Phys. Astron. 11, 342. [CrossRef]

- Roza, E. 2025: Introduction to the Structural Model of Particle Physics, Kindle Books ISBN 978-90-90401-461.

- Roza, E. 2020: On the second dipole moment of Dirac’s particle, Found. of Phys. 50, 828. [CrossRef]

- Roza, E. 2021: On the second dipole moment of Dirac’s particle, updated, www.preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Comay, E. 1985: Comments on the charge-monopole canonical formalism, Lett. Nuovo Cimento 80B, 159. [CrossRef]

- Comay, E. 1995: Charges, Monopoles and Duality Relations, Nuovo Cimento, 80B,1347 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto S., Laiho J., Sharpe S.R. 2020: Lattice Quantum Chromodynamics, pdg.libl.gov, rpp2020-rev-lattce-qcd.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).