1. Introduction

The global cement industry faces significant environmental challenges due to its substantial energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. Cement clinker production alone accounts for nearly 8% of global CO₂ emissions, primarily attributed to the high temperatures (~1450°C) required during clinker formation [

1,

2]. The reliance on fossil fuels and natural raw materials such as limestone and clay further exacerbates these environmental impacts [

3]. Consequently, considerable attention has been given to finding alternative raw materials and innovative processes that can mitigate these issues by reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions [

4].

One promising strategy involves utilizing industrial waste streams as partial substitutes for traditional raw materials. Incorporating waste materials into cement production not only contributes to resource conservation but also promotes circular economic practices [

5]. Previous research has demonstrated the successful use of various industrial wastes, including fly ash, blast furnace slag, and sewage sludge, as partial replacements for conventional raw materials. These practices have consistently resulted in improved environmental profiles and potential energy savings [

6,

7].

Recently, semiconductor industry waste, particularly chemical mechanical polishing (CMP) sludge, has garnered attention as a potential cement substitute due to its unique chemical composition, which contains significant amounts of SiO₂, Al₂O₃, and fluorine (F) [

8]. Despite its classification as hazardous waste, semiconductor sludge shows potential benefits due to its pozzolanic properties, high silica-alumina content, and fluxing characteristics derived from fluorine [

9,

10]. The property is especially advantageous in clinker production, as fluxing agents can significantly lower sintering temperatures [

11].

Fluorine has historically been used in small quantities as a mineralizer in cement kilns due to its ability to lower the melting temperature of clinker raw mixes, enhance mineral phase formation, and improve kiln efficiency [

12]. However, research specifically targeting semiconductor industry-derived fluorine-rich waste for reducing clinker temperature remains limited [

13]. Understanding how this waste influences clinker formation processes and mineralogical characteristics could open a novel pathway toward energy-efficient cement production [

14].

This study focuses on exploring the potential of semiconductor industrial waste containing 11.4 wt.% fluorine as a mineralizing agent in Portland cement clinker production. By systematically investigating clinker sintering behavior at different substitution levels (6%, 9%, and 12%) and varying temperatures (1300–1500°C), this research aims to identify the optimal parameters for significant temperature reduction. Furthermore, it assesses the impact of incorporating fluorine-rich sludge on clinker mineralogy, chemical balance, and overall clinker quality parameters, including free CaO content and oxide composition.

The findings from this research provide valuable insights into achieving lower clinker sintering temperatures, enhancing energy efficiency, and promoting sustainable cement manufacturing practices. Ultimately, this contributes to reducing the environmental footprint of the cement industry, aligning with global objectives for sustainable development and waste resource management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

In this study, reagent-grade chemicals and fluorine-rich semiconductor industrial waste sludge were utilized as raw materials for producing cement clinker. The Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) raw materials conformed to KSL 5201 (2013) standards and exhibited a compressive strength of 42.5 MPa, serving as the baseline reference [

15]. he semiconductor sludge was sourced from a local manufacturing facility in South Korea and was notable for its high fluorine content (11.4 wt.%), elevated alumina levels (19 wt.%), and substantial CaO concentration (36.8 wt.%). Comprehensive chemical characterization of the sludge was carried out using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) for elemental analysis, carbon/sulfur analyzers for determining organic and sulfur content, and ion chromatography for fluoride ion detection. The complete chemical composition of the sludge is presented in

Table 1, with principal oxides expressed as weight percentages (wt.%).

The high fluorine concentration suggests the sludge may act as a mineralizing flux during clinker sintering, lowering melting points and facilitating phase formation. The elevated alumina content is expected to influence the formation of aluminate phases, which are critical in clinker mineralogy [

16].

2.2. Raw Mix Preparation and Chemical Moduli Calculation

Raw mixes were prepared by partially substituting OPC raw materials with semiconductor sludge at mass replacement levels of 6%, 9%, and 12%. The mixing proportions of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃), silicon dioxide (SiO₂), ferric oxide (Fe₂O₃), and sludge content for each blend are detailed in

Table 2.

The replacement levels of semiconductor sludge (6%, 9%, and 12%) were carefully selected based on preliminary tests and relevant literature. Initially, a lower substitution rate (6%) was chosen to observe the primary effects of sludge incorporation on clinker properties. Subsequently, increments of 3% were applied (9% and 12%), aligning with common experimental practices in cement industry research. Higher replacement levels (>12%) were avoided to prevent potential deterioration of clinker quality and practical difficulties during the sintering process.

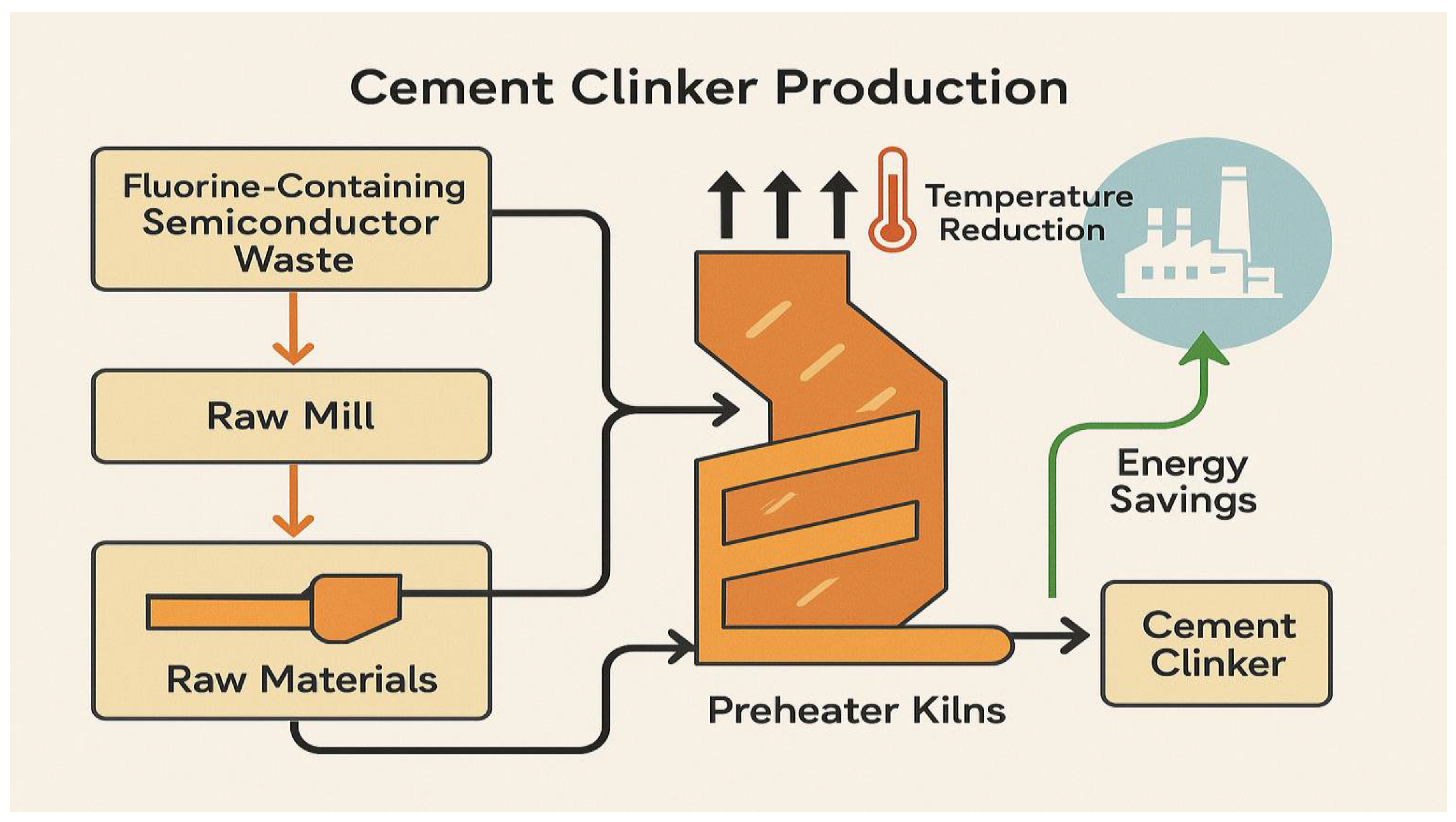

The schematic diagram in

Figure 1 illustrates the process of incorporating semiconductor sludge into cement clinker production. In this process, fluorine-rich semiconductor waste is blended with conventional raw materials and then processed through the standard cement manufacturing steps. The presence of semiconductor sludge helps lower the required sintering temperature, which leads to reduced energy consumption and increased efficiency in clinker production. This approach not only offers energy savings but also promotes the utilization of industrial waste, contributing to more sustainable cement manufacturing practices

To evaluate the suitability of the raw mixes for clinker formation, key chemical moduli were calculated based on oxide weight percentages:

Lime Saturation Factor (LSF): Indicates the proportion of calcium oxide relative to silica, alumina, and iron oxide, and is critical for clinker burnability [

17].

Silica Modulus (SM): Ratio of silica to the combined alumina and ferric oxides, impacting the silicate phase formation [

18].

Iron Modulus (IM): Ratio of ferric oxide to alumina, influencing aluminate and ferrite phase content [

19].

The calculated moduli for all blended raw mixes were within optimal ranges (LSF ~92.0, SM ~2.5, IM ~1.6), indicating favorable conditions for clinker production.

2.3. Sample Preparation and Sintering Procedure

All raw materials were carefully and precisely weighed according to the specific mix proportions provided in

Table 2, ensuring consistency and reproducibility of the samples. The weighed powders were then subjected to homogenization using an HT-1000 ball mill for 1 hour. During this milling process, zirconia grinding media with diameters of 10 mm and 20 mm were employed to promote effective particle size reduction and uniform mixing of the constituent powders. The dual size of grinding media facilitated both impact and attrition mechanisms, enhancing the overall homogenization quality.

Following the milling step, distilled water was gradually introduced into the powder mixture at a controlled ratio of 35% by weight relative to the total powder mass. This addition was critical to achieve an optimal level of plasticity, enabling the mixture to be easily shaped without cracking or crumbling during sphere formation [

20]. The resulting moist paste was then formed into spherical spheres, each with an approximate mass of 25 grams, using a manual press. This manual pressing method ensured consistent sphere size and shape, which is essential for uniform sintering behavior.

After shaping, the spheres were dried at 120°C for 24 hours to remove moisture thoroughly and improve their structural integrity before sintering. This drying step was necessary to prevent defects such as cracking or bloating during the subsequent high-temperature sintering process. The dried spheres were then placed in a high-temperature electric furnace and sintered at temperatures ranging from 1300°C to 1500°C, with increments of 50°C, to systematically investigate the effect of sintering temperature on the material properties. Each sintering cycle was carefully controlled in terms of heating rate, dwell time, and atmosphere to maintain consistency.

For comparative purposes, reference spheres made of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) were prepared and sintered under the same conditions at temperatures ranging from 1300°C to 1500°C in 50°C increments. These OPC spheres served as the baseline for evaluating the performance and properties of the test samples.

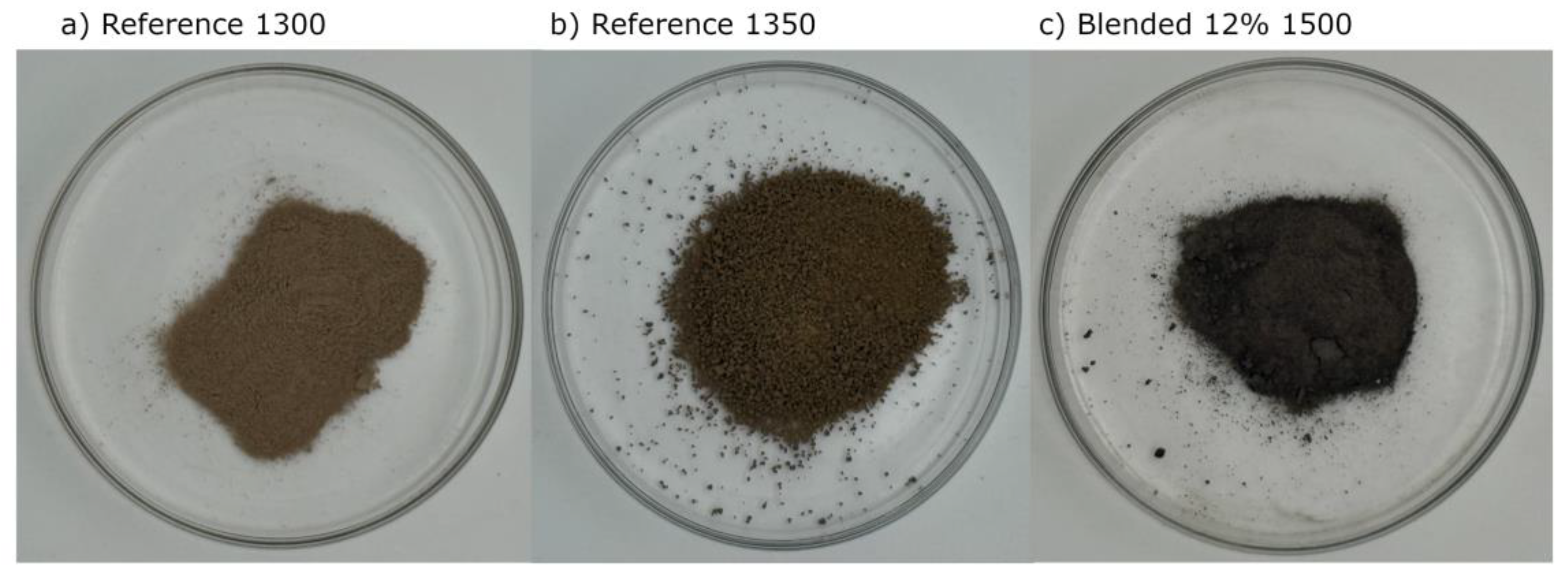

Figure 2 presents photographs of cement clinker samples following the sintering process. The reference OPC clinker sintered at 1300°C displays a finer particle morphology, indicative of incomplete sintering. In contrast, the reference OPC clinker processed at 1350°C exhibits a coarser texture with larger and more aggregated particles, reflecting enhanced sintering progression. Notably, the blended clinker containing 12% semiconductor sludge and sintered at 1500°C demonstrates a distinctly darker color and the presence of well-defined crystalline structures, suggesting significant phase development and possible alterations in mineralogical composition resulting from the higher temperature and sludge incorporation.

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Determination of Free Calcium Oxide (Free CaO)

The Free Calcium Oxide content, which indicates incomplete clinker formation, was determined using a chemical extraction method. The clinker was finely ground, and its weight was precisely measured. It was then mixed with ethylene glycol, a solvent specifically used to dissolve only the Free CaO. The mixture was incubated in a temperature-controlled water bath at 50–60°C for approximately 30 minutes to ensure the complete dissolution of the Free CaO, while minimizing the dissolution of calcium silicate and carbonate phases. After incubation, the mixture was filtered under vacuum to separate undissolved solid particles. The resulting clear solution, containing dissolved Free CaO, was carefully collected to avoid loss or contamination [

21].

The filtrate was titrated with a standardized 0.1 M hydrochloric acid solution. Bromo-cresol green was used as the pH indicator because it exhibits a distinct color change around pH 4.7–5.2, allowing for the accurate determination of the titration endpoint. During titration, hydrochloric acid neutralizes the dissolved Free CaO, and the color change from blue to yellow indicates the endpoint [

22]. The volume of hydrochloric acid consumed at the endpoint was accurately recorded, and the Free CaO content was calculated using the stoichiometric relationship between CaO and hydrochloric acid. The calculation accounted for the sample weight and dilution factors to express Free CaO as a percentage of the clinker sample [

23].

2.4.2. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectroscopy

The major oxide compositions of clinker samples were quantitatively analyzed by X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy using a RIGAKU Supermini 200 instrument. To prepare the samples for analysis, powdered clinker was pressed into pellets and covered with polyethylene (P.E.) film to prevent contamination and sample loss while maintaining a consistent surface for measurement. This thin P.E. film is X-ray transparent, allowing accurate excitation and detection of characteristic fluorescence without interfering with the analysis [

24]. Each sample underwent measurement for 30 minutes to ensure high precision, accuracy, and reproducibility. The analysis targeted key oxides including calcium oxide (CaO), silicon dioxide (SiO₂), aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃), iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃), magnesium oxide (MgO), sulfur trioxide (SO₃), sodium oxide (Na₂O), and potassium oxide (K₂O) [

25]. The resulting quantitative data were used to verify the chemical composition of the clinker after sintering, confirming that the sintering process achieved the intended oxide proportions [

26]. Furthermore, these measurements enabled a direct comparison with the raw mix proportions, providing insight into the consistency and efficiency of the clinker production process.

2.4.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

The mineralogical phase identification and quantification of clinker samples were systematically performed using a Bruker D6 Phaser X-ray diffractometer, operated at an accelerating voltage of 40 kV and an emission current of 15 mA. This instrument configuration ensures sufficient X-ray intensity for clear diffraction signals and optimal resolution [

27]. To prevent hydration and alteration of the clinker phases during sample preparation, samples were finely ground while suspended in 95% isopropanol [

28]. The use of isopropanol as a grinding medium minimizes exposure to atmospheric moisture, thus preserving the original mineral phases for accurate analysis. The powdered samples were then evenly spread on a zero-background sample holder designed to reduce noise and enhance signal clarity [

29,

30].

Diffraction data were collected by scanning over a 2θ angular range from 5° to 70°, employing a step size typically between 0.02° and 0.05° 2θ, with a total scan time of approximately 3 hours. This extended scan duration and acceptable angular resolution enable the acquisition of high-quality diffraction patterns with well-defined peaks, allowing for the precise identification of both major and minor mineralogical phases. For quantitative phase analysis, the Rietveld refinement technique was applied using HighScore Plus software. The Rietveld method involves fitting a calculated diffraction pattern to the observed data by adjusting crystal structure parameters, peak shapes, background, and instrumental effects [

31]. This comprehensive approach facilitates the accurate quantification of phase abundances, even in complex multiphase clinker samples. The resulting phase compositions provide critical insight into clinker quality, informing the optimization of raw material mixtures and sintering conditions to achieve desired cement performance characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. FreeCao Analysis

The FreeCaO content of clinker samples incorporating fluorine-containing semiconductor sludge at replacement levels of 6%, 9%, and 12% was systematically evaluated across sintering temperatures ranging from 1300°C to 1500°C. The results are summarized in

Table 3.

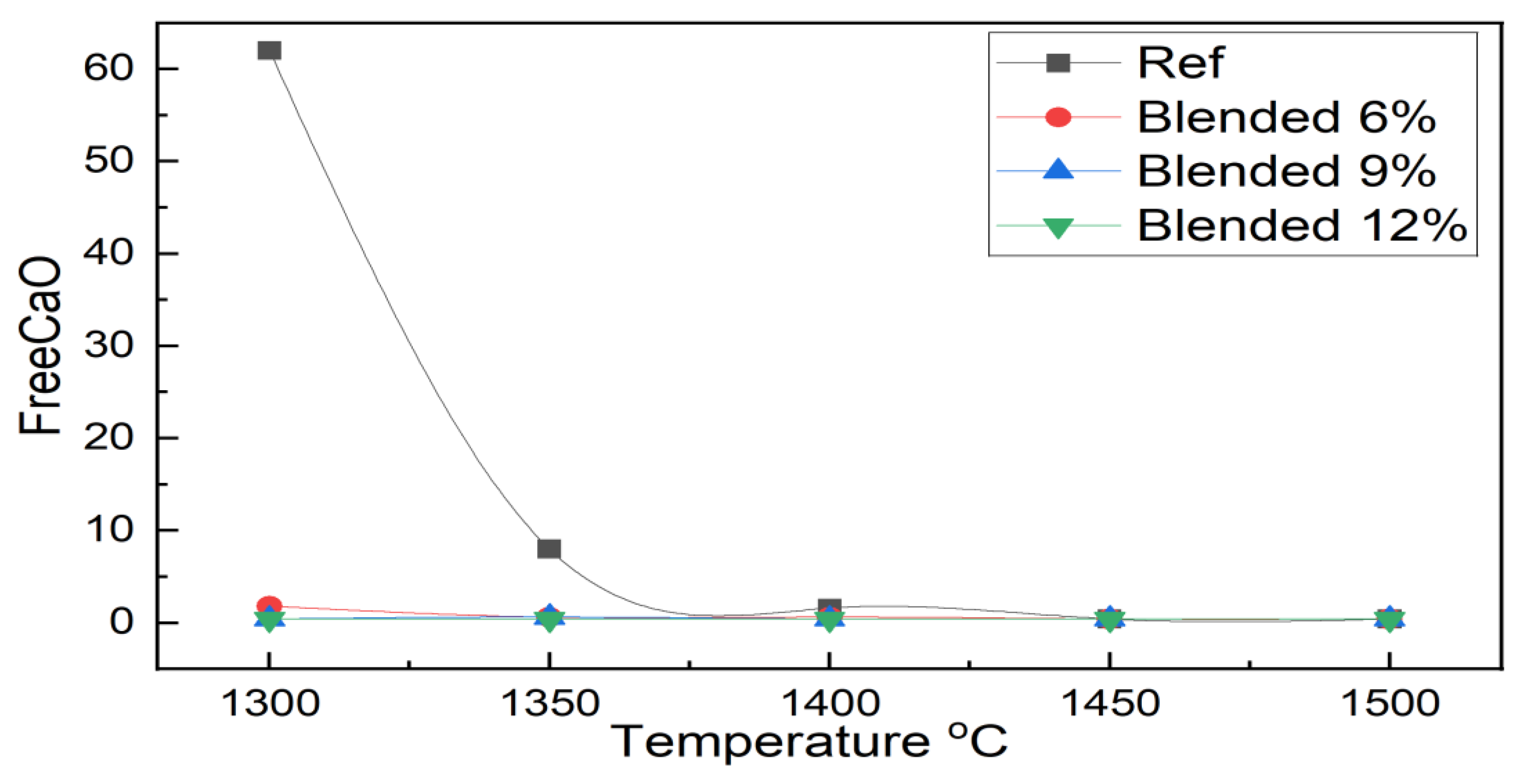

A detailed examination of

Table 3 and

Figure 3 reveals a pronounced difference in FreeCaO content between the reference OPC and the sludge-blended clinkers, highlighting the impact of fluorine-containing semiconductor sludge on clinker formation kinetics and burnability. Specifically, the reference OPC clinker exhibits a FreeCaO value of 62 at 1300°C, which is indicative of highly incomplete clinker mineralization and insufficient solid-state reactions under these conditions. In stark contrast, the blended samples containing 9 and 12 units of semiconductor sludge demonstrate a drastic reduction in FreeCaO to 0.4 at the same temperature. This result provides compelling evidence that the introduction of fluorine-rich sludge acts as an effective mineralizer, significantly enhancing the reactivity of the raw mix and accelerating the decarbonation and silicate phase formation processes at lower temperatures.

At 1350°C, this beneficial effect is further corroborated by the FreeCaO values: the reference clinker remains at a relatively high value of 8, while the blended samples achieve near-complete conversion with FreeCaO values of 0.6 and 0.4 for 9 and 12 units of sludge, respectively. The sharp decrease in residual FreeCaO in the sludge-containing blends across both temperature points suggests improved melt formation and greater mobility of constituent ions, facilitating the incorporation of free lime into major clinker phases such as alite (C₃S) and belite (C₂S) [

32].

These findings underscore the role of fluorine, introduced via semiconductor sludge, in reducing the activation energy required for key clinker-forming reactions. The fluxing action of fluorine lowers the melting point of the system, expands the temperature window for liquid phase formation, and promotes earlier onset of mineralogical transformations. Consequently, full clinker formation can be achieved at temperatures substantially lower than conventional practice without sacrificing product quality. Such improvements not only enhance thermal efficiency and reduce fuel consumption but also open new pathways for the sustainable utilization of industrial waste in cement manufacturing.

3.2. X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis

The chemical compositions of clinker samples prepared by partially replacing raw materials with fluorine-containing semiconductor sludge at 0% 6%, 9%, and 12% were analyzed by XRF spectroscopy and compared to the reference OPC clinker. This analysis quantified principal oxides, such as CaO, SiO₂, Al₂O₃, and Fe₂O₃, as well as minor oxides including MgO, SO₃, Na₂O, and K₂O, with high precision.

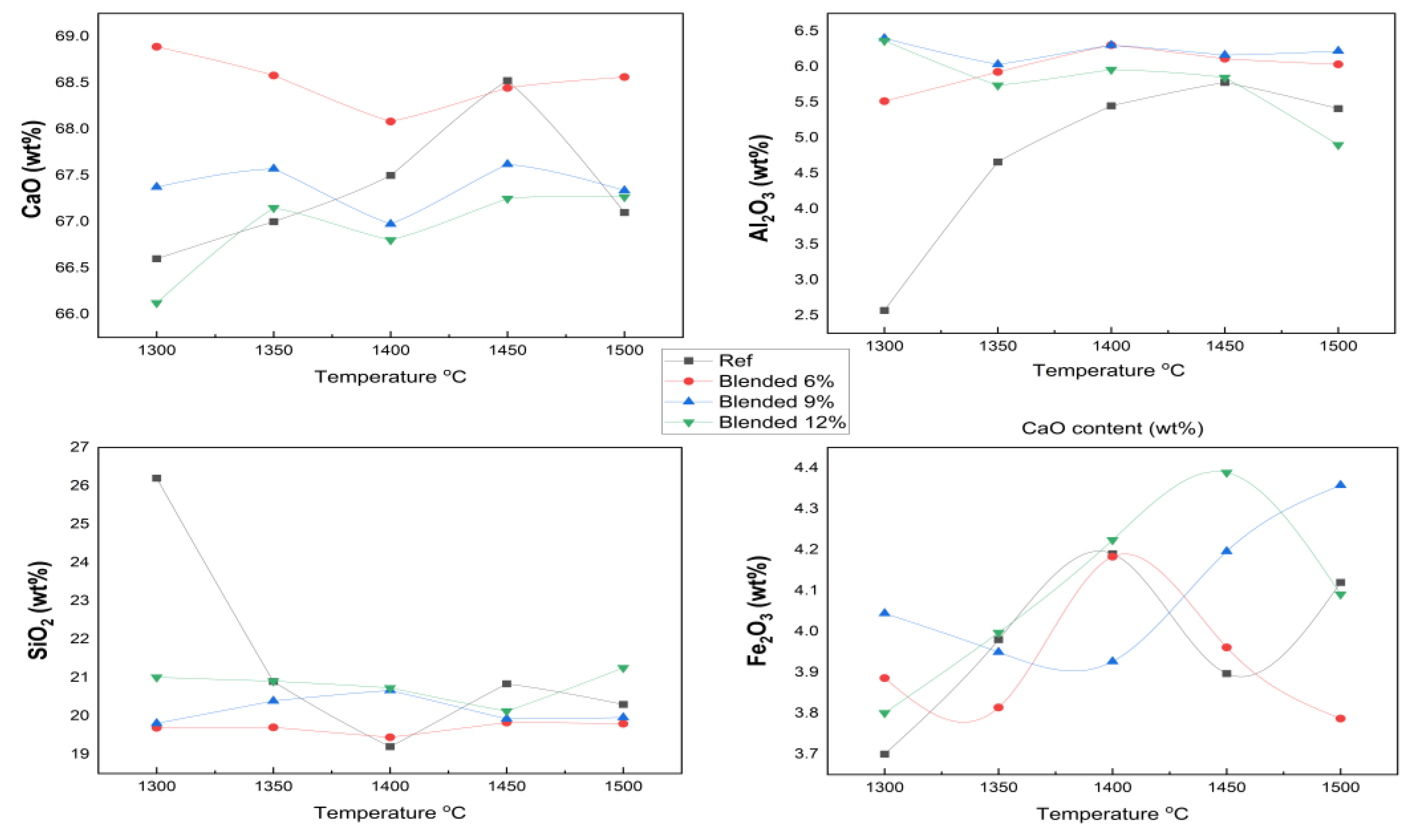

The comprehensive XRF analysis presented in

Table 4 reveals systematic variations in clinker chemical composition as a function of semiconductor sludge replacement levels and sintering temperatures. The CaO content a critical factor influencing clinker phase stability and hydraulic reactivity—remained consistently within the typical Portland cement clinker range (~60–68), demonstrating robust compositional integrity despite partial substitution of raw materials.

Notably, the Al₂O₃ concentration increased proportionally with sludge addition, reflecting the high alumina content inherent to the semiconductor sludge. This chemical enrichment is expected to significantly influence clinker phase assemblage, particularly by promoting the formation and volume fraction of calcium aluminate phases (e.g., C₃A), which can affect cement hydration kinetics and early strength development.

Conversely, the SiO₂ content remained relatively stable across all samples, thereby maintaining the silica modulus within optimal limits essential for clinker quality. Minor oxides such as MgO, SO₃, Na₂O, and K₂O exhibited minimal fluctuations, indicating that sludge incorporation did not adversely impact these constituents. Importantly, the fluorine-rich sludge appears to function as a flux during sintering, lowering the eutectic temperature and facilitating liquid phase formation. This enhances mass transport and accelerates phase transformations, consistent with the reductions in FreeCaO content shown in

Figure 3 and the stabilized oxide concentrations illustrated in

Figure 4. The fluxing effect of fluorine thus underpins the improved burnability and sintering efficiency observed in sludge-blended clinkers.

Calculated chemical indices Lime Saturation Factor (LSF), Silica Modulus (SM), and Iron Modulus (IM) remain within optimal ranges for all blends, confirming the chemical viability for producing high-performance clinker. Collectively, these results demonstrate that partial replacement of raw materials with semiconductor sludge does not compromise clinker chemical integrity or phase equilibrium but rather introduces beneficial modifications enhancing sintering and clinker quality. clinker.

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

The Clinker samples sintered between 1300°C and 1500°C with 6%, 9%, and 12% fluorine-containing semiconductor sludge were quantitatively analyzed by Rietveld refinement of XRD patterns.

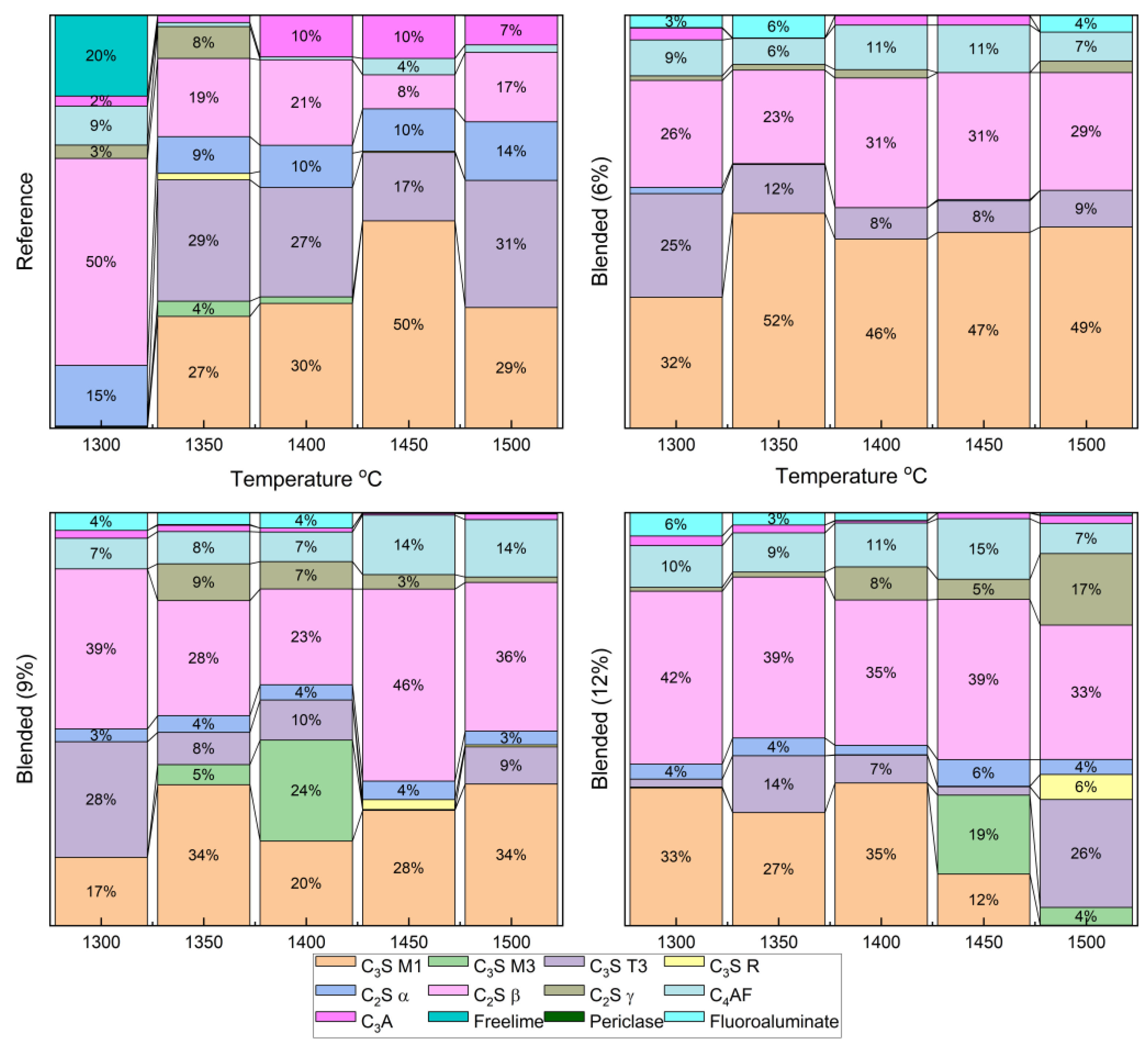

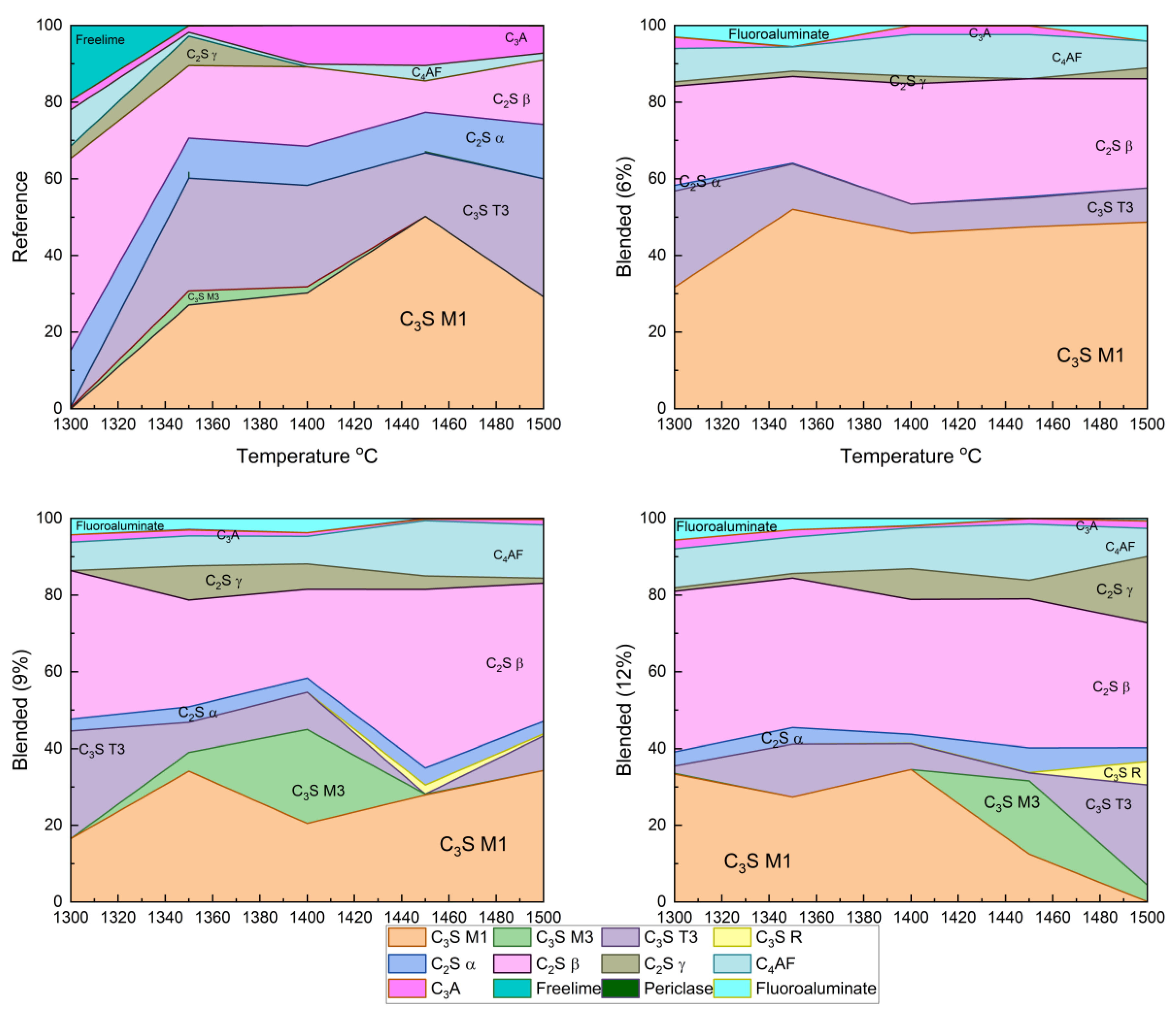

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show detailed phase distributions, including alite polymorphs (C₃S M1, M3, T3, R), belite polymorphs (C₂S α, β, γ), ferrite (C₄AF), aluminate (C₃A), free lime, periclase, and a fluorine-containing compound (Al₇Ca₆O₁₆F).

The reference clinker sintered at 1300°C showed insufficient alite and belite formation, resulting in a poorly sintered, dusted structure, confirmed by high free lime content in

Figure 3 and

Figure 5. In contrast, fluorine-rich sludge addition stabilized reactive belite polymorphs and altered alite polymorph distribution, increasing C₃S M3 and T3 phases.

These changes enable clinker formation at lower temperatures without compromising quality, enhancing sintering efficiency and reducing cement production energy consumption. Reduced aluminate (C₃A) content and unique fluorine-bearing phases highlight sludge-derived fluorine’s complex chemical role, potentially improving hydration kinetics and long-term durability.

-

1.

Fluorine-Induced Modulation of Alite (C₃S) Polymorph Distribution and Stability

The incorporation of fluorine-rich semiconductor sludge into the raw mix significantly alters the polymorphic distribution of alite phases. Quantitative analysis revealed a marked increase in metastable polymorphs C₃S M3 and T3 at the expense of the dominant stable C₃S M1 phase. This transformation suggests that fluorine acts to destabilize the equilibrium favoring C₃S M1, promoting dynamic phase transitions that enhance crystal nucleation and growth kinetics. Such modulation is critical as polymorphic form influences the hydration reaction rates and, consequently, the early strength development and durability of the cementitious matrix. The dynamic balance among alite polymorphs under fluorine influence likely facilitates more efficient hydration pathways and mechanical performance improvements.

-

2.

Belite Enhanced Stabilization and Prevalence of Reactive Belite (C₂S β) Polymorph

The study found a consistent and significant increase in the highly reactive β-polymorph of belite (C₂S β) with increasing sludge content. This polymorph is known for its superior hydraulic reactivity and contribution to long-term strength gain in cement. Fluorine’s stabilizing effect on this polymorph suggests an alteration of the clinker’s phase equilibrium, enabling enhanced formation and retention of reactive belite at lower sintering temperatures. This stabilization not only supports improved mechanical properties over extended curing periods but also indicates a potential reduction in energy consumption by lowering the required sintering temperature for clinker production.

-

3.

The Impact on Aluminate (C₃A) and Ferrite (C₄AF) Phase Chemistry

Fluorine-rich sludge significantly suppressed the formation of the aluminate phase (C₃A), reducing its content to nearly a quarter of that observed in conventional OPC clinker. Since C₃A influences setting time and sulfate resistance, this suppression could lead to cement with enhanced durability and tailored setting characteristics. Concurrently, the ferrite phase (C₄AF) increased in concentration, which affects clinker color and hydraulic properties. The interplay of these phase shifts reflects complex chemical rebalancing induced by fluorine incorporation, which alters the overall clinker mineralogy and its functional properties.

-

4.

Free Near-Complete Reaction Evidenced by Minimal Free Lime (CaO) Content

The near absence of free lime across all samples, regardless of sludge content, indicates highly efficient sintering and reaction completeness. This observation confirms that fluorine addition does not compromise clinker quality but rather maintains or enhances the full conversion of raw materials into stable clinker phases. The minimized free lime content is a crucial indicator of clinker stability and long-term performance.

-

5.

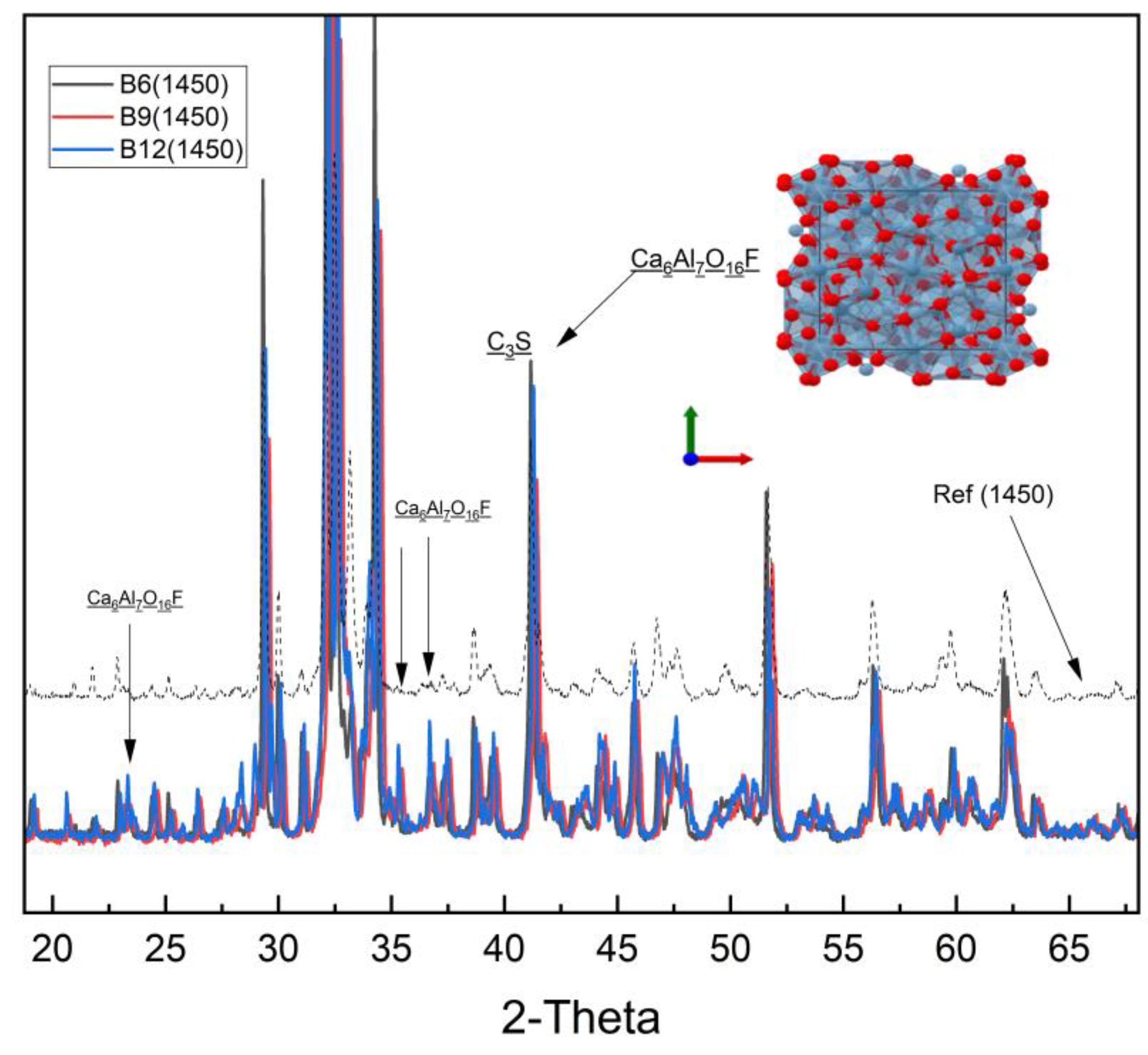

Formation of Unique Fluorine-Bearing Mineral Phase as Mineralizer

The exclusive detection of the Al7Ca6O16F phase in sludge-containing clinkers substantiates the role of fluorine as a mineralizing agent. This unique fluorine-bearing phase integrates into the clinker lattice and promotes phase transformations at reduced sintering temperatures. By lowering the energy barrier for phase formation, this mineralizer facilitates clinker densification and phase homogeneity, ultimately improving clinker microstructure and mechanical integrity.

These fluorine-driven modifications of clinker mineralogy open pathways for energy-efficient cement production by enabling lower temperature sintering without sacrificing product quality. The altered phase assemblage enhances hydration kinetics and mechanical performance, particularly improving early strength gain and long-term durability. This study underscores the potential of using fluorine-containing industrial by-products, such as semiconductor sludge, as functional additives to tailor clinker chemistry, supporting sustainable manufacturing practices and advancing the development of high-performance cementitious materials.

Figure 7 shows powder X-ray diffraction patterns of belite-rich clinkers B6 (black), B9 (red), and B12 (blue) sintered at 1450°C, compared to a laboratory reference clinker (grey dashed). Major peaks correspond to belite (C₂S), with minor alite (C₃S) and a fluoride-stabilized calcium aluminate phase, Ca₆Al₇O₁₆F. Black arrows indicate Ca₆Al₇O₁₆F reflections. The inset depicts the crystal structure of Ca₆Al₇O₁₆F (Ca: blue; AlO₄ tetrahedra: grey; O/F: red). Intensities are normalized, and patterns are vertically offset for clarity.

3.4. Energy Saving and Carbon Emission Reduction Estimation

The incorporation of fluorine-containing semiconductor sludge into clinker production demonstrated the potential to reduce sintering temperature by approximately 100 to 150°C compared to conventional Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) clinker, which typically sinters at around 1450°C. This temperature reduction directly translates into significant energy savings and associated reductions in carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions [

34].

-

1.

Energy Consumption Reduction

Cement clinker production is an energy-intensive process, with fuel consumption strongly dependent on sintering temperature. Previous studies indicate that for every 10°C decrease in sintering temperature, energy consumption decreases by approximately 1.5%. Applying this relationship to the observed temperature reduction yields an estimated energy saving of:

-

2.

Carbon Emission Reduction

Cement manufacturing accounts for approximately 5–7% of global anthropogenic CO₂ emissions, primarily due to the combustion of fossil fuels during the production of clinker. Given that CO₂ emissions are roughly proportional to energy consumption, the reduction in emissions can be estimated as:

As summarized in

Table 5, a reduction in clinker sintering temperature by 100 to 150°C has the potential to decrease energy consumption by approximately 15 to 22.5%. This substantial energy savings directly correlates with a significant reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, estimated to be between 0.105 and 0.203 tons of CO₂ per ton of clinker produced, assuming emission factors of 0.7 and 0.9 tons of CO₂ per ton of clinker.

The use of fluorine-rich semiconductor sludge as a mineralizer not only improves clinker quality and promotes phase formation at lower temperatures but also offers a pathway to reduce the environmental footprint of cement production. The potential energy savings and CO₂ emission reductions contribute to both economic and ecological sustainability, supporting global efforts to mitigate climate change.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the significant mineralogical and environmental benefits of incorporating fluorine-containing semiconductor sludge into cement clinker production. Integrating experimental results from XRD, XRF, and FreeCaO analyses provides a comprehensive understanding of fluorine’s impact on clinker phase formation, sintering temperature reduction, and sustainability metrics.

-

1.

Mineralogical Impacts and Phase Transformations

Rietveld refinement of XRD data showed that fluorine alters the polymorphic distribution of alite (C₃S), favoring metastable phases C₃S M3 and T3. This polymorphic shift is likely to positively influence early hydration kinetics and mechanical strength developments [

35]. The reactive belite (C₂S β) polymorph is stabilized and enriched with increasing sludge content, potentially improving long-term strength. Suppression of aluminate (C₃A) phases in sludge-containing clinkers suggests enhanced sulfate resistance and altered setting behavior[

36]. The formation of fluorine-bearing phases such as Al

7Ca

6O

16F confirm fluorine’s role as a mineralizer, facilitating clinker formation at lower temperatures [

37].

-

2.

Environmental and Energy Implications

A reduction in sintering temperature by approximately 100–150°C is estimated to save 15–22.5% energy. Given the high energy demand of clinker production, this reduction translates into significant operational cost savings and lower fossil fuel consumption[

38]. Based on emission factors of 0.7–0.9 tons of CO₂ per ton of clinker, this corresponds to a reduction of about 0.1–0.2 tons CO₂ emissions per ton of clinker produced, substantially mitigating the cement industry’s carbon footprint [

39].

-

3.

Practical Considerations and Future Work

While the benefits of fluorine-containing sludge are evident, further research is necessary to evaluate the long-term durability of cements produced with modified clinker phases. Scale-up studies are required to assess industrial feasibility, including kiln operation, emission control, and product consistency. Detailed investigations of phase transformation kinetics and fluorine’s influence on hydration mechanisms will deepen understanding and enable optimization of formulations for maximal environmental and performance benefits.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant influence of fluorine-containing semiconductor sludge as a partial substitute in cement clinker production. The incorporation of fluorine fundamentally alters clinker mineralogy by stabilizing the reactive β-polymorph of belite and shifting the polymorphic distribution of alite phases. These mineralogical changes are shown to improve early hydration kinetics and enhance the mechanical strength development of cementitious materials, indicating clear performance benefits from sludge addition.

Moreover, the presence of fluorine facilitates a marked reduction in clinker sintering temperature by up to 150°C without compromising phase quality or clinker stability. This thermal reduction corresponds to substantial energy savings estimated between 15% and 22.5%, and a decrease in CO₂ emissions of approximately 0.1 to 0.2 tons per ton of clinker produced. The formation of unique fluorine-bearing mineral phases acts as mineralizers that promote clinker phase development and reactivity at lower temperatures, further reinforcing the environmental and operational advantages of this approach.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate a promising pathway for sustainable cement manufacturing through the valorization of industrial semiconductor sludge waste. Future research should focus on scaling up the process to industrial levels, thoroughly evaluating long-term durability, and elucidating the mechanistic effects of fluorine on clinker hydration and phase transformation kinetics. Such efforts will enable the optimization of clinker formulations for enhanced environmental performance and mechanical properties, advancing the development of eco-efficient cement production technologies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M and Y.S.C; methodology, B.M; software, B.M and Y.J.L; validation, B.M, Y.J.L and Y.S.C; formal analysis, B.M; investigation, B.M and Y.S.C; resources, Y.J.L and Y.S.C data curation, B.M; writing—original draft preparation, B.M; writing—review and editing, Y.J.L, J.H.J.K and B.M, supervision; J.H.J.K, Y.S.C; funding acquisition, Y.S.C; correspondence, J.H.J.K and Y.S.C; additional contributions including project coordination, technical guidance, and manuscript revision support, Y.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (RS-2024-00438915, Development of technology for continuous process of low-temperature sintering clinkers and high efficiency of preheating and cooling processes) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea)

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to SAMPYO Cement Company and their dedicated R&D team for their generous support and valuable contributions to this study. Their willingness to provide

supplementary materials and share critical information played a significant role in the successful completion of our research. We greatly appreciate their collaboration, which enhanced the depth and quality of our work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| XRD |

X-Ray Diffraction |

| XRF |

X-Ray Fluorescence |

| OPC |

Ordinary Portland Cement |

| FreeCaO |

Free Calcium Oxide |

| C₃S |

Tricalcium Silicate (Alite) |

| C₂S |

Dicalcium Silicate (Belite) |

| C₃A |

Tricalcium Aluminate |

| C₄AF |

Tetracalcium Aluminoferrite (Ferrite) |

| OPC |

Ordinary Portland Cement |

| M1, M3, T3, R |

Polymorphs of Alite (C₃S) |

Appendix A

This appendix contains supplementary experimental data and detailed calculations supporting the main findings presented in the manuscript.

XRD Rietveld Refinement Data: Complete phase quantification results for all clinker samples at various sintering temperatures, including minor phases not shown in the main text.

FreeCaO Measurements: Detailed raw data and calculation methods for free calcium oxide content across samples.

XRF Elemental Analysis: Full elemental composition tables with raw spectral data used for Thermo-Calc input.

Energy and CO₂ Emission Calculations: Step-by-step calculation sheets for estimating energy savings and carbon emission reductions based on sintering temperature reductions, including assumptions and formula derivations.

Experimental Setup: Photographs and schematic diagrams of the experimental setup and sample preparation protocols.

All raw data and calculation spreadsheets are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Table A1.

Extended XRD Phase Quantification Data.

Table A1.

Extended XRD Phase Quantification Data.

| Sample ID |

C₃S M1 |

C₃S M3 |

C₃S T3 |

C₂S b |

C₄AF |

C₃A |

Free CaO |

Other Phases |

| Ref-1450°C |

49.4 |

0 |

16.3 |

8.1 |

3.9 |

10.3 |

0 |

12.0 |

| B6-1300°C |

31.7 |

0 |

25.1 |

25.9 |

8.7 |

2.9 |

0.1 |

11.6 |

References

- W. Luo, Z. Shi, W. Wang, A. Yu, and Z. Liu, “Eco-Friendly Cement Clinker Manufacturing Using Industrial Solid Waste and Natural Idle Resources as Alternative Raw Materials,” Energy & Environment Management, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 59–65, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Jessa and A. Ajidahun, “Sustainable practices in cement and concrete production: Reducing CO2 emissions and enhancing carbon sequestration,” https://wjarr.com/sites/default/files/WJARR-2024-1412.pdf, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 2301–2310, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Vasiliu, L. Lazar, L. Rusu, and M. Harja, “EFFECT OF ALTERNATIVE RAW MATERIALS OVER CLINCKER QUALITY AND CO2 EMISSIONS,” Scientific Study & Research. Chemistry & Chemical Engineering, Biotechnology, Food Industry, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 325–334, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu, “Carbon Emission Assessment and Environmental Impact of Cement in the Context of Carbon Neutrality,” Applied and Computational Engineering, vol. 159, no. 1, pp. 77–84, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Abdul-Wahab, H. Al-Dhamri, G. Ram, and V. P. Chatterjee, “An overview of alternative raw materials used in cement and clinker manufacturing,” International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 743–760, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Mangi et al., “Potentiality of Industrial Waste as Supplementary Cementitious Material in Concrete Production,” International Review of Civil Engineering (IRECE), vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 214–221, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Flegar, M. Serdar, D. Londono-Zuluaga, and K. Scrivener, “Regional Waste Streams as Potential Raw Materials for Immediate Implementation in Cement Production,” Materials 2020, Vol. 13, Page 5456, vol. 13, no. 23, p. 5456, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Kırgız et al., “Waste marble sludge and calcined clay brick powders in conventional cement farina production for cleaner built environment,” Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 3467, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Jang and T. N. Abebe, “Utilizing Wheel Washing Machine Sludge as a Cement Substitute in Repair Mortar: An Experimental Investigation into Material Characteristics,” Materials 2024, Vol. 17, Page 2037, vol. 17, no. 9, p. 2037, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Shyamala et al., “Evaluation of Paper Industry waste sludge and nano materials on properties of concrete,” E3S Web of Conferences, vol. 621, p. 01018, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. O. Rusănescu et al., “Recovery of Sewage Sludge in the Cement Industry,” Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 2664, vol. 15, no. 7, p. 2664, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bouregba, A. Diouri, B. Elghattas, A. Boukhari, and T. Guedira, “Influence of Fluorine on Clinker burnability and mechanical properties of CPA Moroccan cement,” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 149, p. 01075, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sinharoy, G. Y. Lee, and C. M. Chung, “Optimization of Calcium Fluoride Crystallization Process for Treatment of High-Concentration Fluoride-Containing Semiconductor Industry Wastewater,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 7, p. 3960, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. A., D. Yu., N. I., and V. Yu., “EFFICIENCY OF USING A TECHNOGENIC PRODUCT OF ELECTROLYTIC PRODUCTION OF ALUMINUM AS A MINERALIZER WHEN FIRING PORTLAND CEMENT CLINKER,” Bulletin of Belgorod State Technological University named after. V. G. Shukhov, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 71–80, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mend, Y. J. Lee, D. Y. Kwon, J. H. Bang, and Y. S. Chu, “Utilisation of industrial sludge-derived ferrous sulfate for hexavalent chromium mitigation in cement,” Advances in Cement Research, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. A., D. Yu., N. M., N. I., and K. S., “STUDY OF THE MINERALIZING EFFECT OF CRYOLITE AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE PROCESSES OF CLINKER FORMATION,” Bulletin of Belgorod State Technological University named after. V. G. Shukhov, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 86–95, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, Y. Cui, and X. Tong, “The regeneration of cement from completely recyclable mortar: effect of raw materials compositions,” Advances in Cement Research, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Author, Y.-S. Chu, Y.-J. Lee, N.-I. Kim, J.-H. Cho, and S.-K. Seo, “A Study on the Characteristics of Clinker and Cement as Chlorine Content,” Resources Recycling 2021 30:5, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 10–16, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Guo, S. Wang, L. Lu, and H. Wang, “Influence of barium oxide on the composition and performance of alite-rich Portland cement,” Advances in Cement Research, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 139–144, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. M. L. Pereira, A. L. R. de Souza, V. M. S. Capuzzo, and R. de Melo Lameiras, “Effect of the water/binder ratio on the hydration process of Portland cement pastes with silica fume and metakaolin,” Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais, vol. 15, no. 1, p. e15105, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Lau, S. F. Luk, N. L. N. Cheng, and H. Y. Woo, “Determination of free lime in clinker and cement by lodometry: An undergraduate experiment in redox titrimetry,” J Chem Educ, vol. 78, no. 12, pp. 1671–1673, 2001. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Tobón, M. F. Díaz-Burbano, and O. J. Restrepo-Baena, “Optimal fluorite/gypsum mineralizer ratio in Portland cement clinkering,” Materiales de Construcción, vol. 66, no. 322, pp. e086–e086, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Mao, W. Zhang, L. Zhang, Z. Ma, Q. Cui, and H. Wang, “Research on Preparation Process of Lithium Slag for High Belite Sulfoaluminate Cement Clinker,” Waste Biomass Valorization, pp. 1–11, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Khelifi, F. Ayari, H. Tiss, and D. Ben Hassan Chehimi, “X-ray fluorescence analysis of Portland cement and clinker for major and trace elements: Accuracy and precision,” Journal of the Australian Ceramic Society, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 743–749, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Test Methods for Chemical Analysis of Hydraulic Cement,” May 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Abdul et al., “On the variability of industrial Portland cement clinker: Microstructural characterisation and the fate of chemical elements,” Cem Concr Res, vol. 189, p. 107773, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tlamsamania, M. Ait-Mouha, S. Slassi, Y. Khaddam, D. Londono Zuluaga, and K. Yamni, “Quantitative phase analysis of anhydrous clinker Portland using Rietveld method,” Reviews in Inorganic Chemistry, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 189–199, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Santos et al., “Novel high-resistance clinkers with 1.10 < CaO/SiO2 < 1.25: production route and preliminary hydration characterization,” Cem Concr Res, vol. 85, pp. 39–47, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Her, J. Park, P. Li, and S. Bae, “Feasibility study on utilization of pulverized eggshell waste as an alternative to limestone in raw materials for Portland cement clinker production,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 324, p. 126589, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cao et al., “Compressive strength prediction of Portland cement clinker using machine learning by XRD data,” J Sustain Cem Based Mater, vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 1120–1131, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim and J. Yoon, “Automated Mineral Identification of Pozzolanic Materials Using XRD Patterns,” Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, vol. 36, no. 12, p. 04024415, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. L. G. Reno, R. J. Silva, M. L. N. M. Melo, and S. B. V. Boas, “AN OVERVIEW OF INDUSTRIAL WASTES AS FUEL AND MINERALIZER IN THE CEMENT INDUSTRY,” Latin American Applied Research - An international journal, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 43–50, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhao, Z. Liu, F. Wang, and S. Hu, “Elucidating factors on the strength of carbonated compacts: Insights from the carbonation of γ-C2S, β-C2S and C3S,” Cem Concr Compos, vol. 155, p. 105806, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. He et al., “Recovery of thermally treated fluorine-containing sludge as the substitutions of Portland cement,” J Clean Prod, vol. 260, p. 121030, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Isteri et al., “The Effect of Fluoride and Iron Content on the Clinkering of Alite-Ye’elimite-Ferrite (AYF) Cement Systems,” Front Built Environ, vol. 7, p. 698830, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Da et al., “Probing into the Triggering Effects of Zinc Presence on the Mineral Formation, Hydration Evolution, and Mechanical Properties of Fluorine-Bearing Clinker,” Langmuir, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Kacimi, A. Simon-Masseron, A. Ghomari, and Z. Derriche, “Reduction of clinkerisation temperature by addition of salts containing fluorine,” Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 1090–1097, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Toure, N. Auyeung, F. M. Sambe, J. S. Malace, and F. Lei, “Cement Clinker based on industrial waste materials,” Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 1–5, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bouregba, A. Diouri, B. Elghattas, A. Boukhari, and T. Guedira, “Influence of Fluorine on Clinker burnability and mechanical properties of CPA Moroccan cement,” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 149, p. 01075, 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).