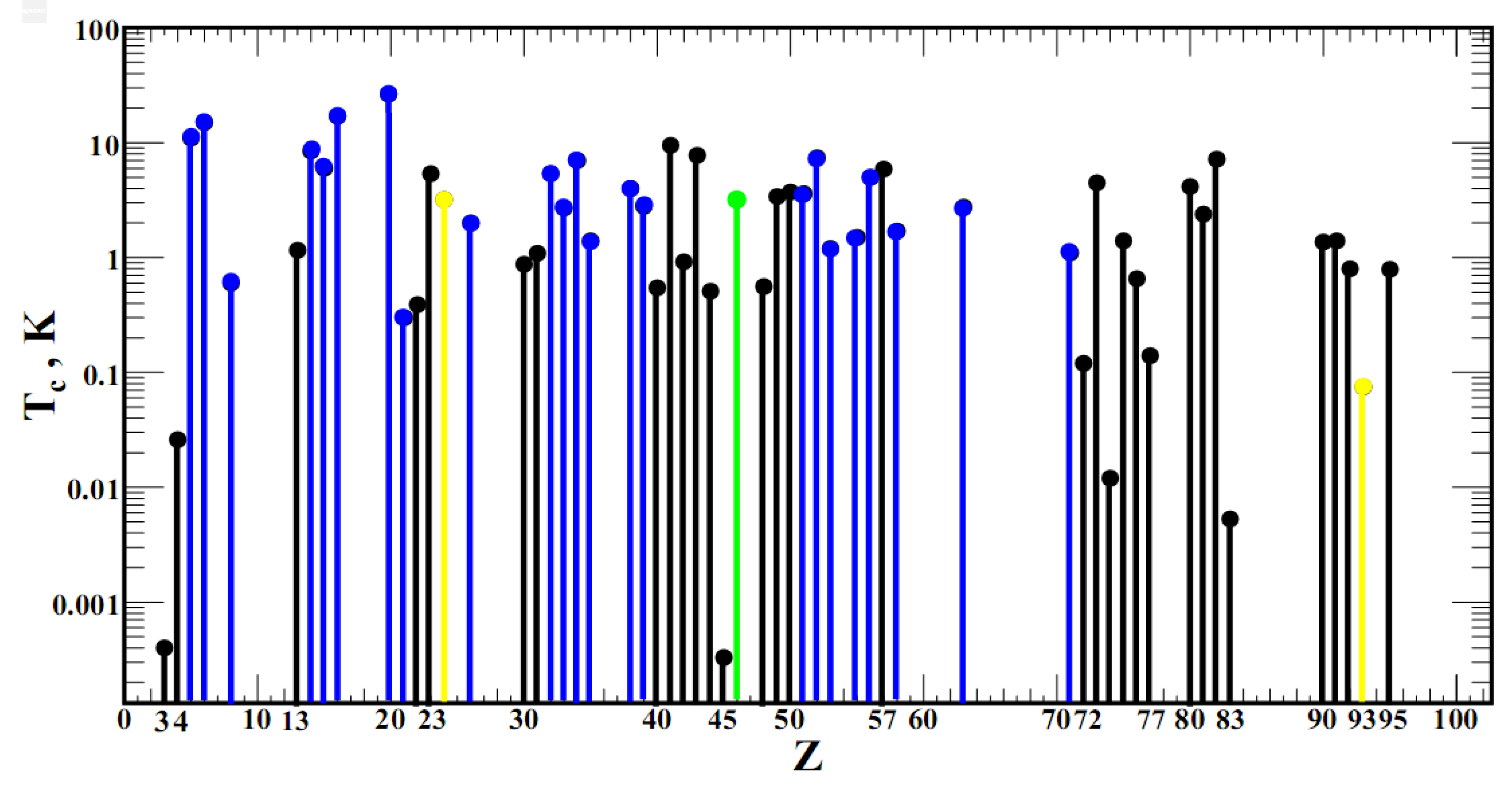

2. Finding a Mathematical Expression for the Tc(Z) Graph

First, we find the domain and range of the function

Tc(

Z), shown in

Figure 1. The domain of this function is the set of natural numbers {

Z ∈

N: 1 ≤

Z ≤ 95}, but this is at first glance. It is known that new transuranic superheavy elements continue to be discovered, and everyone hopes for the existence of an island of nuclear stability after

Z = 164 [

9], which, probably, in the distant future will make it possible to create at least microparticles of these elements to determine their physical properties. Therefore, we will extend the domain of

Tc(

Z) to infinity: {

Z ∈

N: 1 ≤

Z < + ∞}. On the other hand, it is widely believed that the center of neutron stars contains nuclear matter consisting only of neutrons, and great efforts are being made to describe the properties of this matter [

10]. Therefore, we will have to extend the domain of

Tc(

Z) to integers: {

Z ∈

Z: 0 ≤

Z < + ∞}. But in 2011, 309 antihydrogen atoms were produced and trapped for 1000 seconds [

11]. This means that we have the right to assume the possibility of obtaining in the distant future or detecting in space antimatter with an arbitrary negative

Z. Therefore, the domain of

Tc(

Z) is the set of integers: {

Z ∈

Z: – ∞ <

Z < + ∞}.

Figure 1 shows what we have now, but how the graph

Tc(

Z) will expand along the

Z axis over the next hundreds of years, no one knows. The range of

Tc(

Z) is the set of real numbers: {

Tc ∈

R: 0 ≤

Tc ≤ 29}. But we must take into account the possibility of further increasing the critical temperature of elemental superconductors with the improvement of high-pressure technology. Taking into account the possible superconductivity of metallic hydrogen at 450 K and 3.5 TPa pressure [

12], we will expand the range of

Tc(

Z) to 450 K: {

Tc ∈

R: 0 ≤

Tc ≤ 450}.

Suppose we are trying to obtain

Tc(

Z) by solving the Schrödinger equation for electrons in a crystal with arbitrary

Z of its atoms and arbitrary

T,

p, and

D. Inevitably, we will obtain quantum selection rules for some quantum numbers that characterize our system of electrons in this crystal with the ability to form Cooper pairs. Let us denote these quantum numbers by the letter

N, and let them run through integer values from 1 to 57 and further. Let us further assume that these selection rules determine those atomic numbers

Z for which the existence of Cooper pairs is possible. This means that there is some function

Zsc =

f (

N) such that for

N varying from

N = 1 to 57,

f (

N) yields integers that coincide with the atomic numbers of superconducting elements:

Zsc = {3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 13, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57, 58, 63, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 80, 81, 82, 83, 90, 91, 92, 93, 95}. We assume that 57 values of

N can be associated with 57 values from the set

Zsc in any order. We found a combination of integers that matches only 28 numbers from the set

Zsc. Since the range of this combination of integers coincides with the quantum rule (with a given

Zsc) not completely, but only by half, we designated it as

f1/2(

N):

where

rpi(

x) is a function that rounds

x to the nearest integer of

x [

13],

Table 1 contains the values of

N and

f1/2 (

N) without and with rounding. For some values of

f1/2(

N) =

Z we have different

N (these values are highlighted in black in

Table 1): if

N=14 or 28, then

Z = 58, etc.

Let us now return to the dependence of

Tc on

Z in

Figure 1. It can be assumed that

Tc should be expressed in terms of Dirac functions:

where are integers:

Z0 ∈

Zsc. The rule for elements of the set

Zsc is approximately expressed by formula (1). Among the physical characteristics of a superconducting crystal that affect

Tc, we consider the lattice parameters

a ≡

a(

Z,

T,

p,

D),

b ≡

b(

Z,

T,

p,

D) and

c ≡

c(

Z,

T,

p,

D) as functions of atomic number

Z, temperature

T, pressure

p, and irradiation dose

D. In this case the lattice parameters must be taken at

Tc or near

Tc, but as can be seen below, it is not easy to find from scientific data the lattice parameters of crystals of chemical elements at low temperatures.

In the next step, we take into account that most elemental superconductors have an inverse dependence of

Tc on the lattice parameters with increasing pressure [

6]. This dependence is valid only for the first gigapascals or the first tens of GPa. With further increase in pressure, the dependence becomes very complex. To simplify the reasoning, we will adopt a simple inversely proportional relationship between

Tc and the lattice parameters and complicate the Dirac function, which will be responsible for the behavior of

Tc at high pressure:

where

Z0 ∈

Zsc, and we plan to use the following property of the Dirac function:

. Applying this property to (3), we obtain:

These derivatives have a complex behavior with pressure, so we assume that they are responsible for the behavior of

Tc at high pressure via lattice parameters since

a ≡

a (

Z,

p,

D), …. We must take into account that the left side is in Kelvin and to bring the right side to it we must multiply it by the coefficient

:

where

is Planck constant,

c is the speed of light,

kB is Boltzmann constant. We introduced a dimensionless quantity

SZ related to the symmetry of the crystal at given

Tc,

p and

D.

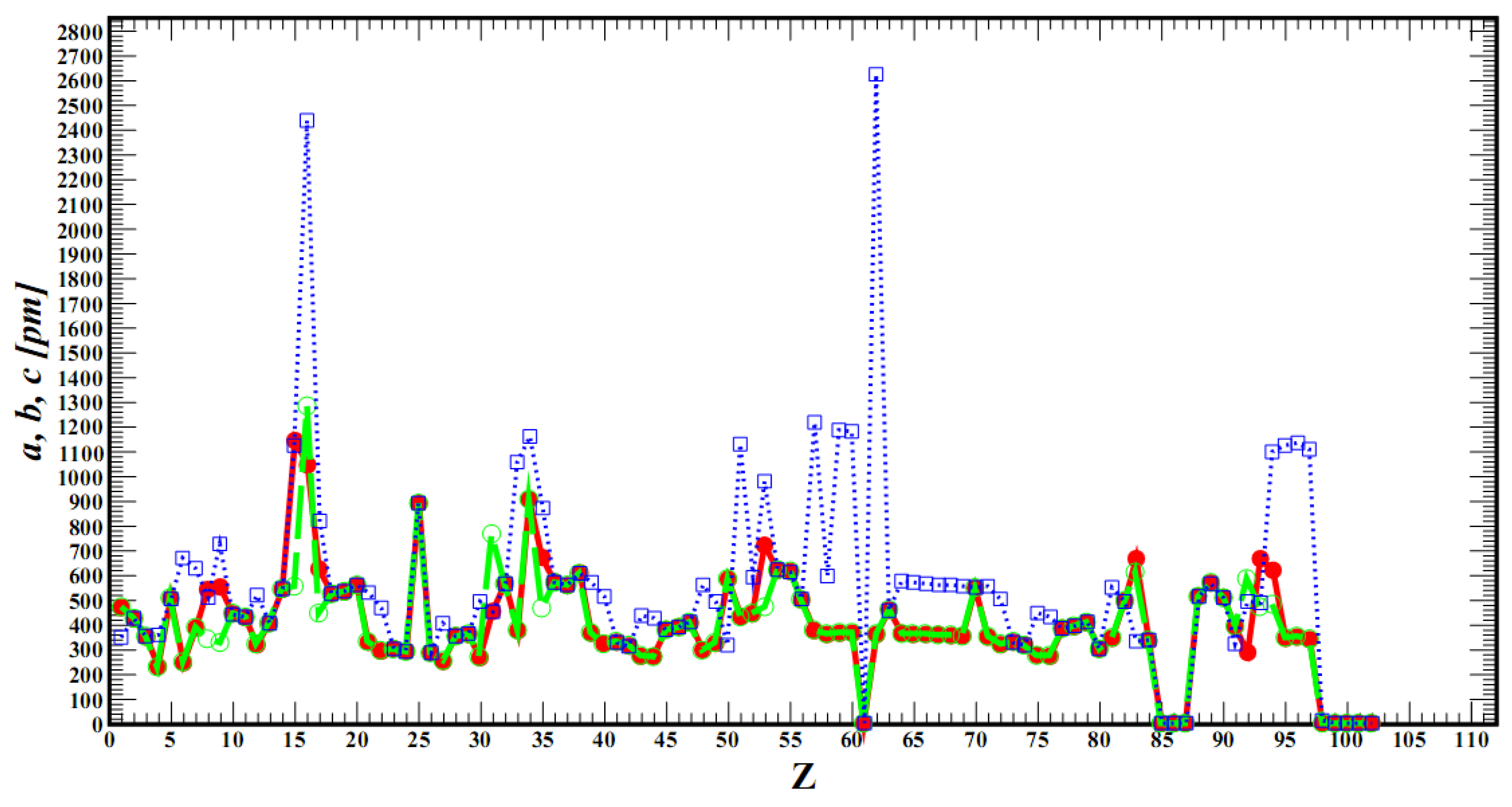

If we know

Tc and the dependence of the lattice parameters on atomic numbers, we can substitute the derivatives into (5) and find

SZ for a particular elemental superconductor. If we find the law of change of

SZ, then we can substitute it into (5) and find the general law of dependence

Tc(

Z). We found that the law of change of lattice parameters from the atomic number of a chemical element does not exist in mathematical form. There are data on the lattice parameters of elements mainly at room temperatures and only for inert gases at low temperatures. In

Figure 2 we have depicted this dependence. There are two ways to calculate the derivatives in (5). The first way is to find a mathematical relationship for

a(

Z),

b(

Z), and

c(

Z) (for fixed

p =

p′ and

D =

D′) using some phenomenology and take derivatives with respect to

Z at

Z0 ∈

Zsc. This is another scientific problem that distracts us from the problem posed in this article. The second way is to take into account that

a(

Z) (and of course

b(

Z),

c(

Z)) is a discrete function, the derivative of which is a simple change in the function when the argument changes by one. We calculate the derivative by averaging this change on the left and right sides of

Z0:

and for

and

we do the same.

Let us find the symmetry coefficients for lithium

S ≡

SLi at room and low temperatures. We will take the pressure equal to atmospheric

p0, and the ionizing radiation is zero (or natural)

D0. We do this to estimate errors in determining symmetry coefficients as majority of lattice parameters data in literature concerns only the room temperature. Lattice parameters of

Li (Z

0 = 3) at room temperature:

a =

b =

c = 351 pm [

14]. Lattice parameters of

He (

Z =

Z0 – 1 = 2) at a temperature of 1 – 1.5 K and a pressure of 2.5 MPa (the solid state is absent at p < 2.5 MPa):

a =

b =

c = 424.2 pm [

15]. Lattice parameters of

Be (

Z =

Z0 + 1 = 4) at room temperature, ambient pressure and zero radiation:

a =

b = 228.58 pm,

c = 358.43 pm [

16]. As a result:

= (228.58 – 424.20)/2 = – 97.81 pm, = – 97.81 pm,

= (358.43 – 424.20)/2 = – 32.88 pm.

Now we substitute this result into (5) and find the symmetry coefficient for lithium SLi:

Tc (Li, p0, D0) = – SLi ⋅ ℏc/kB ⋅1012 ⋅ (97.81 + 97.81 + 32.88)/3512 = – SLi ⋅ 0.23 ⋅ 228.5/3512 = – SLi ⋅ 4.2658 ⋅ 106, SLi = – Tc (Li, p0, D0) / (4.2658 ⋅ 106) = – 4 ⋅ 10 – 4 / (4.2658 ⋅ 106) = – 0.9377 ⋅ 10 – 10.

We have intentionally removed the brackets for the modulus to get the exact value of the symmetry coefficient. Let us repeat the above calculations, taking into account the lattice parameters of

Li at

T = 4.2 K:

a =

b = 311.1 pm,

c = 509.3 pm [

17]. We did not find data for beryllium at low temperatures, and we got:

= (228.58 – 424.20)/2 = – 97.81 pm, = – 97.81 pm,

= (358.43 – 424.20)/2 = – 32.88 pm,

Tc(Li,p0,D0)= – SLi⋅⋅c/kB⋅1012[m]⋅((2⋅97.81/311.12) + 32.88/509.32) = – SLi⋅4.9403⋅106,

SLi = – Tc(Li, p0, D0) / (4.9403⋅106) = – 4⋅10–4 /(4.9403⋅106) = – 0.8097⋅10–10.

The relative deviation between

SLi at room temperature and low temperatures is about 14%. Let us keep in mind that the symmetry coefficients calculated for other superconducting elements with use of lattice parameters at room temperatures deviate from the symmetry coefficient at low temperatures to the same extent. We assume that, just as the derivatives of the lattice parameters of a superconducting element depend on the lattice parameters of neighboring elements with atomic numbers one unit higher and one unit lower, so the symmetry coefficient depends on the crystal structure of neighboring elements. The symmetry coefficients for superconducting bulk elements at ambient pressure

p0 and zero radiation

D0 are given in

Table 2. We did not calculate the symmetry coefficients for superconductors at high pressure or at non-zero ionizing radiation due to the lack of data on the lattice parameters under these conditions. The space group numbers of superconducting elements and their neighbors are also shown in

Table 2. For example, the space group of helium is 225, lithium is 194, and beryllium is also 194, and the transition between these symmetries is denoted as 225 – 194 – 194, where the space group of the superconductor is in the center.

To find a mathematical expression for

SZ, we first find in

Table 2 those that have the same transition space groups, in the hope that they will be close in order of magnitude. And indeed, we have three associations:

1. The 194-194-229 transition for

STi,

SZr and

SHf is highlighted in red in

Table 2, the

SZ for these three elements of Group 4 of the periodic table have similar negative values.

2. The 194-229-229 transition for

SV,

SNb, and

STa, which are related to the elements in Group 5 of the periodic table, is highlighted in blue in

Table 2.

3. The 229-194-194 transition for

STc,

SLa and

SRe in

Table 2 is highlighted in green and has the worst agreement. And three more associations with two elements in each, highlighted in bold black, light gray and yellow. Within pairs, their values have at least the same sign. We explain the discrepancy in each association by using incorrect crystal lattice parameters at room temperatures (they should be at low temperatures), which additionally affects the calculations of derivatives. Now we need to express the symmetry coefficient

SZ in terms of the symmetry properties of crystals of superconducting elements and their neighbors in the periodic table for all these associations.

Since

SZ depends on the symmetry of the superconductor crystal and its neighbors in the periodic table, we can write, for example, for the three transitions 194 – 194 – 229:

where

A194 characterizes the

hcp crystal structure, since the space group number 194 corresponds to the

hcp (hexagonal close-packed) crystal structure of the

P63/mmc space group,

A229 characterizes the

bcc (body-centered cubic) crystal structure. Similarly for the other two associations 194 – 229 – 229 and 229 – 194 – 194:

Since the order of the space groups in their combination for

SZ matters, the signs in (7 – 9) can be different, despite the fact that we have only two coefficients:

A194 and

A229. Having struggled with these expressions, we came to the conclusion that when going from hexagonal to cubic symmetry there should be a sum, and when going from cubic to hexagonal symmetry there should be a subtraction:

A(space grope number) ≡

Asgn must be a function of integers representing the number of mirror planes, the order of the symmetry axes and their number, the presence of a center and axes of inversion, and so on. The best expressions we found satisfactory (10 – 11):

A194 = 1/(9!3!4) = 0.115⋅10

–6,

A229 = –1/(8!3!4) = – 1.033⋅10

–6. These values give an approximate

SZ of (10 – 11). Knowing

A194, we found

A225 from 194 – 194 – 225 for

SRu and

SOs using rule (10):

A225 = – 1/(9!4!4) = – 3⋅10

–8. And we can write approximate formula for

SZ:

where

Asg(atomic number) is the symmetry factor for the element with atomic number

Z with space group number

sg,

n is the number of symmetry axes,

k is the number of mirror planes plus 1 for hexagonal or plus 2 for cubic symmetry,

m = 4 at least for hexagonal and cubic symmetry. And we recall that

SZ is a function of external parameters:

SZ =

SZ (

T,

p,

D), that is, the symmetry of the crystal changes under the influence of external parameters, which we must take into account in the calculations.