Nearly four decades of research on copper oxide high-temperature superconductors (HTSCs) has yielded a rich and complex phase diagram [

1]. Fundamentally, the primary distinction between cuprates and conventional superconductors lies in their doped nature [

2,

3]. Remarkably, subtle adjustments to the doped carrier concentration can trigger nearly all known condensed matter phase transitions [

4,

5]. These phenomena defy explanation within the framework of existing solid-state theories, presenting a severe challenge to traditional electron theory [

6,

7,

8]. Undoubtedly, there is an urgent need for a universal mechanism that enables both explanation and prediction. This mechanism must not only consistently describe the zero electrical resistance and Meissner effect of the superconducting state but also elucidate various anomalous phenomena in the normal state [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. It should account for not only copper-based superconductors but also emerging classes of superconducting materials [

17,

18].

Recent experimental insights enable a universal, self-consistent high-temperature superconductivity (HTS) theory with explanatory and predictive power, underpinned by four key observations:

(1) In correlated superconductors, the electron mean free path is subatomic (theoretically infinite), violating the Mott-Ioffe-Regel (MIR) limit and breaking well-defined quasiparticle excitations [

19,

20].

(2) Shot noise measurements in strange metals challenge discrete quasiparticle current models, showing electric and superconducting currents arise without quasiparticles [

21].

(3) In overdoped HTSCs and FeSe, the positive

-resistivity coefficient correlation [

22,

23] shows higher resistivity may enhance

, while overly low resistivity hinders it. This paradox implies superconductivity arises from an insulating (not metallic) background, consistent with good conductors (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu) lacking superconductivity, while HTS occurs in non-metallic cuprates.

(4) In topological insulator

, STM/STS studies reveal nanoscale coexistence of insulating and conducting domains [

24]. Analogous to charge-ordered structures in doped high-

superconductors (parented by Mott insulators), this coexistence further confirms that current/supercurrent is non-carrier-driven.

This paper defines the dissipation-free superconducting state as a Planck energy-quantized ground state, realized via the Planckian limit

[

25,

26]. Unlike conventional theories describing direct metal-superconductor transitions below

, our framework reveals a two-step pathway: (1) Metal-insulator transition at

, where ultralow temperatures localize electrons in polyhedral quantum wells via coherent condensation to form an insulating Wigner crystal; (2) Insulator-superconductor transition, where an external electric field induces collective electron micro-displacement relative to ionic lattices, forming a polarization capacitor (Coulomb-attractive electron-hole pairing, requiring no additional "glue" [

6]) that triggers symmetry breaking and Maxwell’s displacement current. This mechanism generates dissipation-free current without quasiparticle motion, consistent with the four key experimental findings above.

We derive the critical formula

, where

is the quantum well depth determined by the lattice constant, and

represents the electron–lattice correlation strength in quantum well states. This formula precisely predicts

for cuprate and iron-based superconductors using lattice constants, aligning excellently with experimental data and implying universal applicability. We uncover dualistic relationships between electron-ordered structures and doping [

27], as well as superconducting and pseudogap phases [

28]. Our analytical derivation of the HTSC phase diagram comprehensively accounts for all observed phase transitions. Remarkably, the theory resolves two enduring enigmas: the linear decline of pseudogap magnitude with doping in underdoped regions [

29] and the linear temperature dependence of resistivity in overdoped strange metals [

30].

Quantized Polyhedral Quantum-Well and Planckian Limit

Blackbody radiation, a foundational physics phenomenon that spurred the quantum revolution and reshaped understanding of the microcosm, may also resolve the HTS puzzle. Blackbody experiments show electrons emit radiation and dissipate energy at , yet superconductors exhibit zero energy dissipation for . Thus, superconducting research hinges on explaining how the thermodynamically stable superconducting state avoids spontaneous energy radiation in temperature fields.

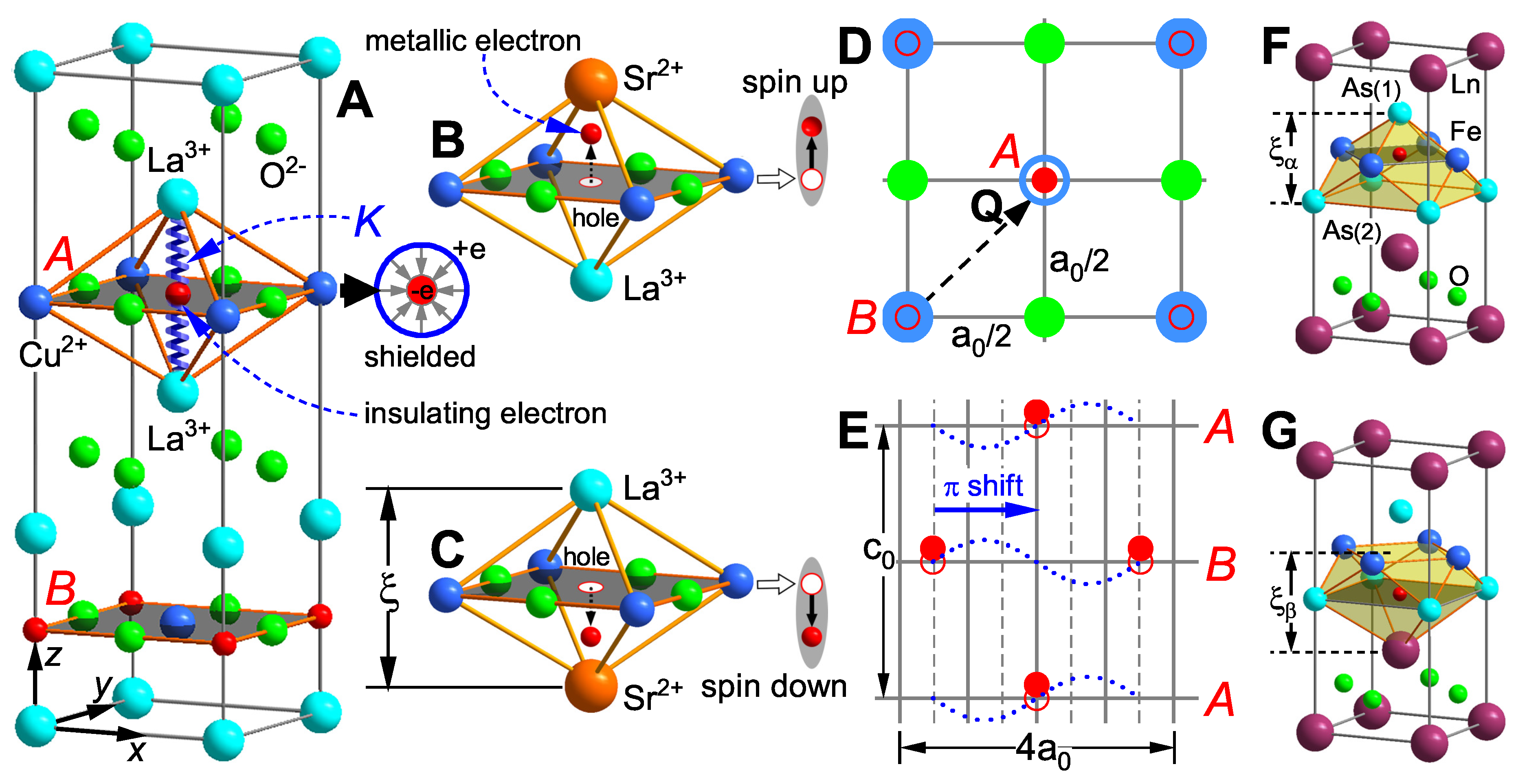

The first high-temperature superconductor was achieved by doping insulator

with Sr/Ba [

31]. In the undoped parent compound (

Figure 1A), quantum well ions show perfect

-directional symmetry, causing complete overlap of positive and negative charge centers. This fully shields localized octahedral electrons via the

shell (right inset) or renders them undetectable, making them unresponsive to external fields; these are termed insulating electrons. When Sr is doped,

substitutes

in two ways. Upper-position doping (

Figure 1B) breaks charge balance at the vertices and the octahedron’s mirror symmetry, pushing electrons upward from the

plane to a new equilibrium position above and leaving a hole at their original site. Lower-position doping (

Figure 1C) similarly pushes electrons downward from the

plane, forming a hole. Doping induces symmetry breaking, generating upward and downward electron-hole electric dipoles (right insets of

Figure 1B and C) that can be depicted by spin-up and spin-down states. These electrons, no longer shielded, respond to external fields and are called metallic or superconducting electrons.

Return to

Figure 1A again, according to Planck’s quantum hypothesis, the localized electron in the figure can be simplified as a quasi-one-dimensional harmonic oscillator. Here,

K represents the stiffness coefficient, which is determined by the Coulomb confinement strength of ions at the two vertices of the octahedral quantum well. The intrinsic frequency

of the harmonic oscillator can then be expressed as:

where

is the angular frequency and

is the effective mass of electron.

Eq. (

1) represents the minimum vibration frequency or the natural frequency of Planck’s quantization theory. For a given material, it has a definite value of

K and a definite Planck energy quantum

. An electron harmonic oscillator must absorb and radiate a complete energy quantum through resonance. However, if the thermal energy provided externally is less than the minimum energy quantum, the thermal vibrations of all electrons will be suppressed entirely. At this point, the electrons will condense into a insulating state with zero entropy and no energy consumption.

Based on the thermodynamic principle of energy equipartition, a superconductor with parameter

K may have a specific critical temperature

satisfying the following relationship:

where

is the Boltzmann constant and

represents the relaxation time of the harmonic oscillator or the scattering rate.

The relationship described by Eq. (

2) universally exists as the Planckian limit in various superconducting materials, with its physical significance readily interpretable. First,

embodies a quintessential quantum effect: were Planck’s constant

,

would necessarily vanish. Second,

serves as an intrinsic material property, precisely characterizing the inherent frequency of superconductors. Therefore, increasing the

K-value (stiffness constant) is the sole method to enhance

. Harder and more brittle materials (e.g., ceramics) with larger

K values are more likely to achieve higher

, while more ductile materials (e.g., good conductors like gold, silver, and copper) have smaller

K values, leading to low or no superconductivity. Based on the definition of resistivity, we can also derive the relationship between the intrinsic resistivity of superconducting materials and their corresponding

:

where

is a material-dependent constant.

As shown in Eq. (

3),

correlates positively with

: poorer conductivity implies stronger superconductivity or a higher transition temperature, contradicting conventional solid-state electron conduction theory. However, recent experiments found

[

22,

23], where

is the linear resistance coefficient, a finding that perfectly validates the physical meaning of Eq. (

3). Despite their apparent opposition, this relation reveals an intrinsic unity between the dissipationless superconducting transition temperature and dissipative resistance. This ubiquitous parameter relation in various systems suggests a universal mechanism underlies resistivity and unconventional superconductivity.

Our research, based entirely on the single-electron approximation, posits that indistinguishability of electron states is prerequisite for the superconducting electron state as a stable thermodynamic system free from thermal fluctuations. That is, clarifying one local electron’s properties reveals all electrons’ behavior. This assumption simplifies the quantum many-body problem to a single-particle one and addresses coherent condensation in the superconducting state. Achieving this requires accounting for structural specifics of high-temperature superconductor crystals. As

Figure 1A shows, each unit cell typically contains two copper oxide planes (

A and

B) with

-plane projections differing by vector

(

Figure 1D). This enables superconducting electrons to form a

-shifted triangular stable Wigner symmetric structure in the non-superconducting

-plane (

Figure 1E). Notably, many high-quality copper oxide superconductors have lattice constants with

, e.g.,

(Bi2201,

[

32]) and

(CCOC,

[

33]). Subsequent sections will further show that all observed charge-ordered phases, exotic phase transitions (especially STM results with four-unit-cell periodicity) derive fundamentally from

Figure 1E.

Universal Inverse-Square Law of

From Eqs. (

1) and (

2), the magnitude of

K directly determines that of

. The parameter

K, characterizing material ductility or brittleness, is fundamentally determined by lattice structure. This explains why doping, pressure, etc., affect

in superconductors by altering lattice parameters. As shown in

Figure 1C, the depth

of the polyhedral quantum well is the key factor influencing

: smaller

enhances Coulomb confinement of local electrons by ions at both vertices, leading to synchronous increases in

K and

. For simplification, assuming the effective charge of polyhedral vertex ions is

and the electric field energy density at the electron’s position is

P, we have:

where

is an undetermined constant related to the properties of the material. Substituting Eq. (

4) into Eq. (

2) , we can immediately obtain:

where

represents the coupling strength between electrons and quantum wells, which is called the correlation strength factor.

Table 1 shows the experimentally measured superconducting transition temperature

of cuprate and iron-based superconductors versus the depth

of polyhedral quantum wells, both following the inverse-square relationship in Eq. (

5). The difference lies in the correlation strength factors, with average values of

and

, three times higher for cuprates, indicating stronger electron correlation and higher

. Notably, the record

of cuprates (164 K) [

34] is also three times that of iron-based superconductors (55 K) [

35]. It has been revealed that the same superconductor can typically form two quantum well structures, corresponding to the frequently observed two superconducting domes with distinct

values, such as in cuprates [

36] and iron-based compounds [

37]. In particular, two groups independently identified superconducting phases at 43 K and 55 K in SmFeAsOF (Rows 10-11 of

Table 1) in 2008 [

35,

38], and our theory predicted

values of 42.2 K and 54.3 K, which are in close agreement with the experiments. Sun et al. observed dual transitions at 32 K and 48.7 K in high-pressure KFeSe [

37], and our model predicted 32.1 K and 49 K (last two rows of

Table 1). Additionally, quantum wells act as quantum resonators where the resonance energy of localized electrons follows the same inverse-square law. For iron-based superconductors,

(meV). Xie et al. found three resonance peaks at 9.5, 13.0, and 18.3 meV in

via neutron spin scattering [

39], while our calculations based on the three resonator heights (fourth last row of

Table 1) yield 9.9, 13.4, and 17.6 meV, consistent with the experimental results.

Superconductivity in

with

80 K under pressures above 14 GPa [

18] has reignited global interest in Ni-based superconductors [

40,

41,

42]. A pivotal question remains: Can Ni-based materials exceed Cu-based

limits? Theories suggest Ni-based

may surpass Cu-based values and even approach room temperature [

40]. Our analysis shows Ni- and Cu-based superconductors share octahedral quantum well structures (

Figure 1A,

). Using

Å [

18] in Eq. (

5), we predict a maximum

K for Ni-based systems. Recent work by Wang et al. confirms this trend:

exhibits

K (2.5 K higher than

) due to Pr-induced lattice contraction (

pm,

pm). The theoretical

K aligns well with experimental results [

42].

To the best of our knowledge, Eq. (

5) represents the first formula capable of accurately predicting the superconducting transition temperature exclusively from crystal structure parameters. This theoretical framework not only enhances our mechanistic understanding of superconducting phenomena but also paves the way for unraveling the enigmatic behavior of matter at the microscale.

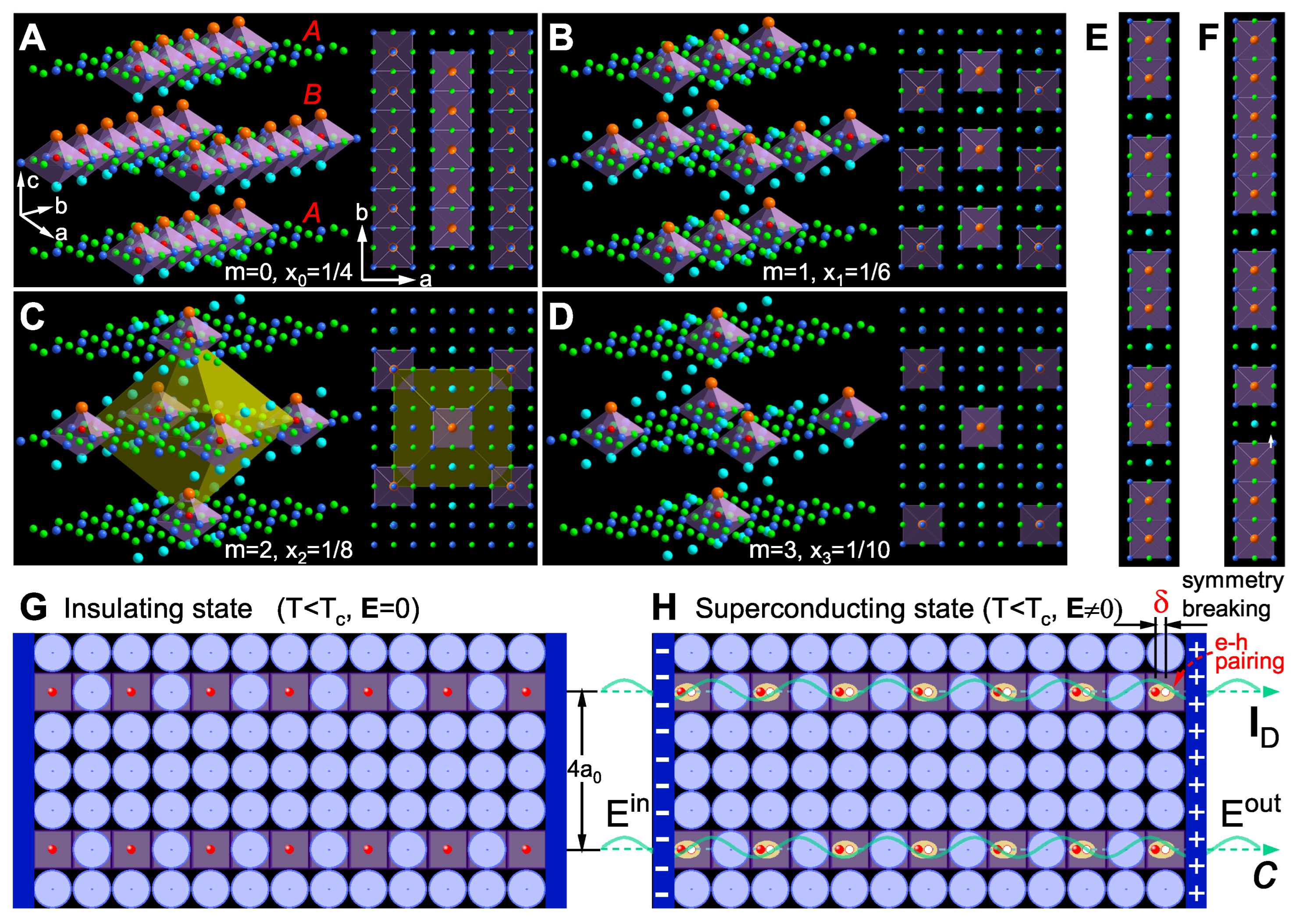

Doping Concentration, Charge Order, Symmetry Breaking and Superconducting Transition

Increasing evidence suggests that layered superconductors exhibit striped superconductivity, where the charge stripe phase is quasi-one-dimensional. Experiments further indicate that superconductivity originates from charge stripes extending along the crystal’s

b-axis, with significantly higher superfluid density than in the

a-axis direction [

43]. As shown in

Figure 1E, the charge

-shift structure on the non-superconducting

-plane is fixed, confining doping concentration changes to the

b-axis direction. Based on the indistinguishability of superconducting electrons and electron crystal stability, the quasi-one-dimensional doping along the

b-axis is assumed periodically uniform, such that the doping concentration can be expressed as:

where

m, the doping principal quantum number, determines many critical properties, including high-temperature superconducting charge order, pseudogap, strange metal behavior, and phase diagrams.

The physical meaning of Eq. (

6) is straightforward: the numerator 2 denotes two types of

planes (

A and

B) along the

c-axis, the denominator 4 represents the charge stripe spacing along the

a-axis, and

m can be written as

(where

p is the number of undoped vacancies and

q is the number of doped sites in quasi-one-dimensional stripes).

Figure 2, A to D depicts four characteristic real-space charge-ordered patterns in cuprate superconductors governed by Eq. (

6).

Figure 2A depicts the overdoped regime (

,

,

) with complete filling of doping sites (see the top view on the right); any additional doping destabilizes the charge order and quenches superconductivity.

Figure 2B illustrates optimal doping

,

,

), where one-dimensional superconducting chains reach half-filling to maximize

.

Figure 2C demonstrates the 1/8 anomaly [

44] at

(

), where equal charge stripe periodicities along the

a- and

b-axes trigger an LTO→ LTT phase transition. This transition pins electrons into stable yellow octahedra, forming an isotropic checkerboard pattern. The resulting structure exhibits insulating behavior, suppressing the superconducting phase transition. Finally,

Figure 2D shows the underdoped state (

,

), where sparse carriers reduce interelectronic coupling, weakening ordered-state stiffness and

K values, thus lowering

.

It should be noted that

Figure 2, A to D show the ideal theoretical results of long-range charge-ordered structures with integer doping. In experiments, fractional doping (

Figure 2E), disordered doping (

Figure 2F), mixed doping, and local inhomogeneous doping occur due to variations in doping concentration, temperature, etc. Different dopings induce commensurate/incommensurate and long/short-range electron orders, jointly forming the rich high-temperature superconducting phase diagram [

1]. Regarding the relationship between

Figure 2 A to D charge ordering structures and superconductivity: Traditional views suggest that superconducting phase transition occurs spontaneously at

. However, we propose a different perspective: Superconducting phase transition must be accompanied by symmetry breaking, while cooling alone does not induce macroscopic symmetry breaking. Take

as an example: Below

, all half-doped quasi-1D electrons in the

plane freeze at equilibrium positions (

Figure 2G). Due to the lattice field symmetry shielding effect, electrons condense into a rigid insulating state. Despite coherent condensation, the superconducting phase transition has not yet occurred.

Figure 2H shows that an external electric field induces collective electron displacement

and symmetry breaking, which microscopically resembles electron-hole pairing (requiring no additional “glue" [

6]) or the generation of quantized capacitance (yellow ellipse). These structures act as capacitive elements in large-scale integrated circuits, and their superposition forms macroscopic polarized charges and total capacitance at the ends of the superconductor. According to Maxwell’s hypothesis, a displacement current

arises within the superconductor. The superconducting current, essentially an electromagnetic wave that requires no directional electron motion, can propagate noiselessly and unimpeded during transmission even when the confined quasi-1D quantum channels are not fully doped (with spatially segregated conducting (doped) and insulating (undoped) regions) [

21]. Notably, quasi-1D electronic structures serve as a universal guarantee for maintaining superconductivity in various monolayer 2D superconductors [

45,

46,

47].

The superconducting phase transition is a two-step process, with the intermediate insulating state being crucial. Strictly speaking, superconductivity is impossible without the insulating state. In metals like gold, silver, and copper, electrons cannot completely freeze into an insulating state under existing low-temperature conditions, hence no superconductivity is exhibited. Everything has two sides, though: if the insulating property (locality) is too strong, as in the undoped parent compounds of high-temperature superconductors, an external field cannot drive the symmetry breaking of electron states as shown in

Figure 2H, preventing the superconducting phase transition from occurring.

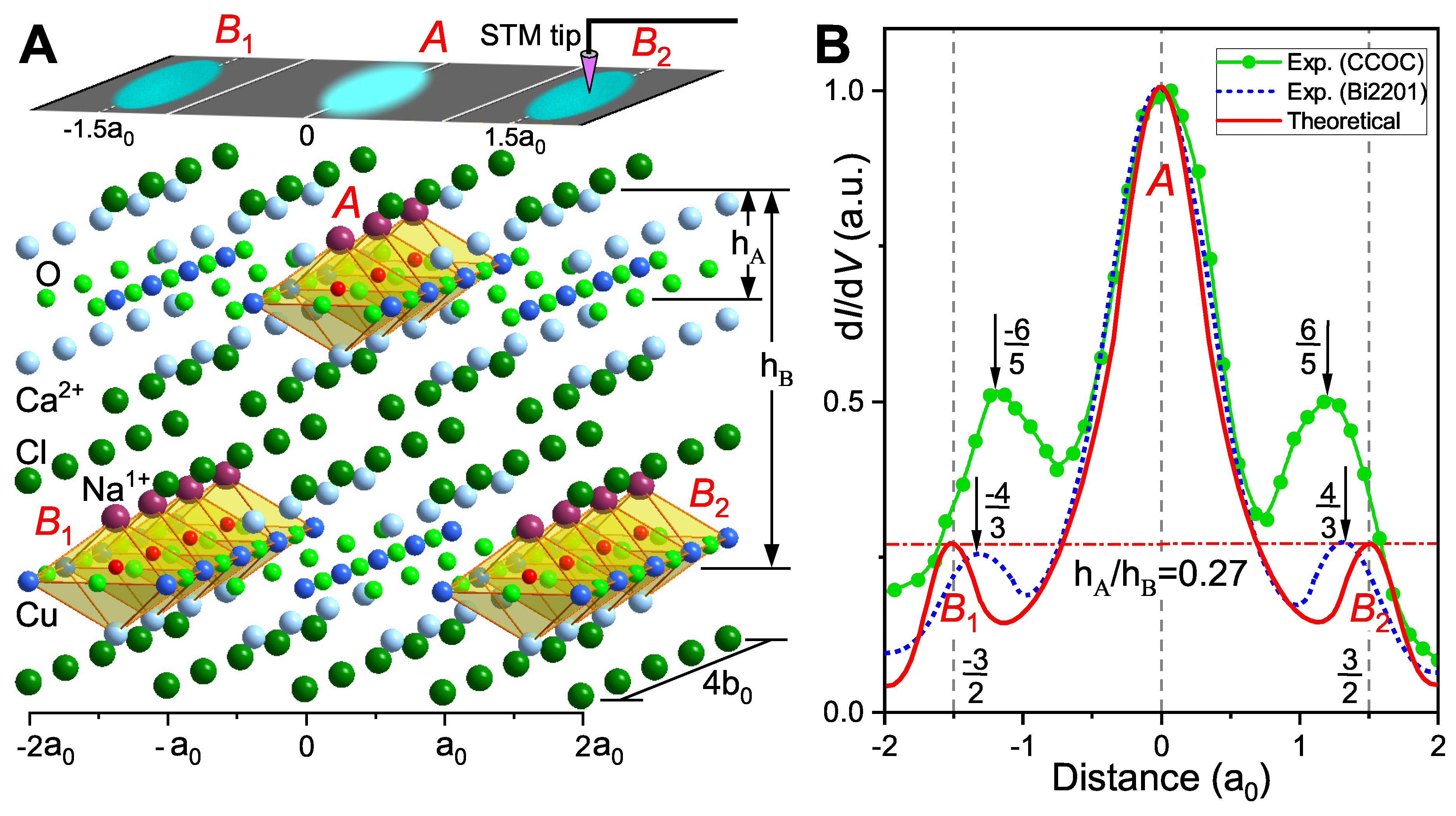

It is well-known that stripe phases with 4-fold lattice periodicity widely exist in cuprate superconductors, though theoretical interpretations of their origin remain controversial. Here, we propose a plausible explanation: these phases arise from intrinsic double

layers (

) and

-shift stability in high-

materials (

Figure 1E). In extreme underdoping (

), sparse charge carriers fail to form long-range order due to weak interactions/competition, driving electrons to form short-range

near-cube incommensurate clusters. Recently, two teams independently observed via STM local nematic states of typical size

in (Bi2201) [

32] and (CCOC) [

33] systems, providing new experimental support for our mechanism.

Figure 3A shows the

plaquette cluster in CCOC, where

replaces

, breaking mirror symmetry and inducing hole doping in octahedral quantum wells. From stability and symmetry, doping at the central position of the upper

layer forms three connected octahedral quantum wells (

A), whose electrons correspond to the brightest central bar in STM experiments. Doping at

in the lower

plane forms symmetrically arranged four-connected octahedral quantum wells (

and

). As the lower

plane (

B) is farther from the cleavage plane (

), its STM bars appear darker. Based on

Figure 3A, the theoretical DOS peak result is qualitatively shown as the red line in

Figure 3B. The intensity ratio of the central peak to secondary peaks is quantitatively determined by

. Taking the central peak as 1, secondary peaks equal

. For CCOC and Bi2201,

and

are (2.742 Å, 10.263 Å) and (4.662 Å, 17.175 Å), giving

k values of 0.267 and 0.271, respectively. Then, the value of the two secondary peaks is approximately 0.27 (red dotted line in

Figure 3B). Experimental results for CCOC (green) and Bi2201 (blue) show good agreement for Bi2201, while CCOC has secondary peak position/intensity errors, likely due to scanning speed and probe-sample distance.

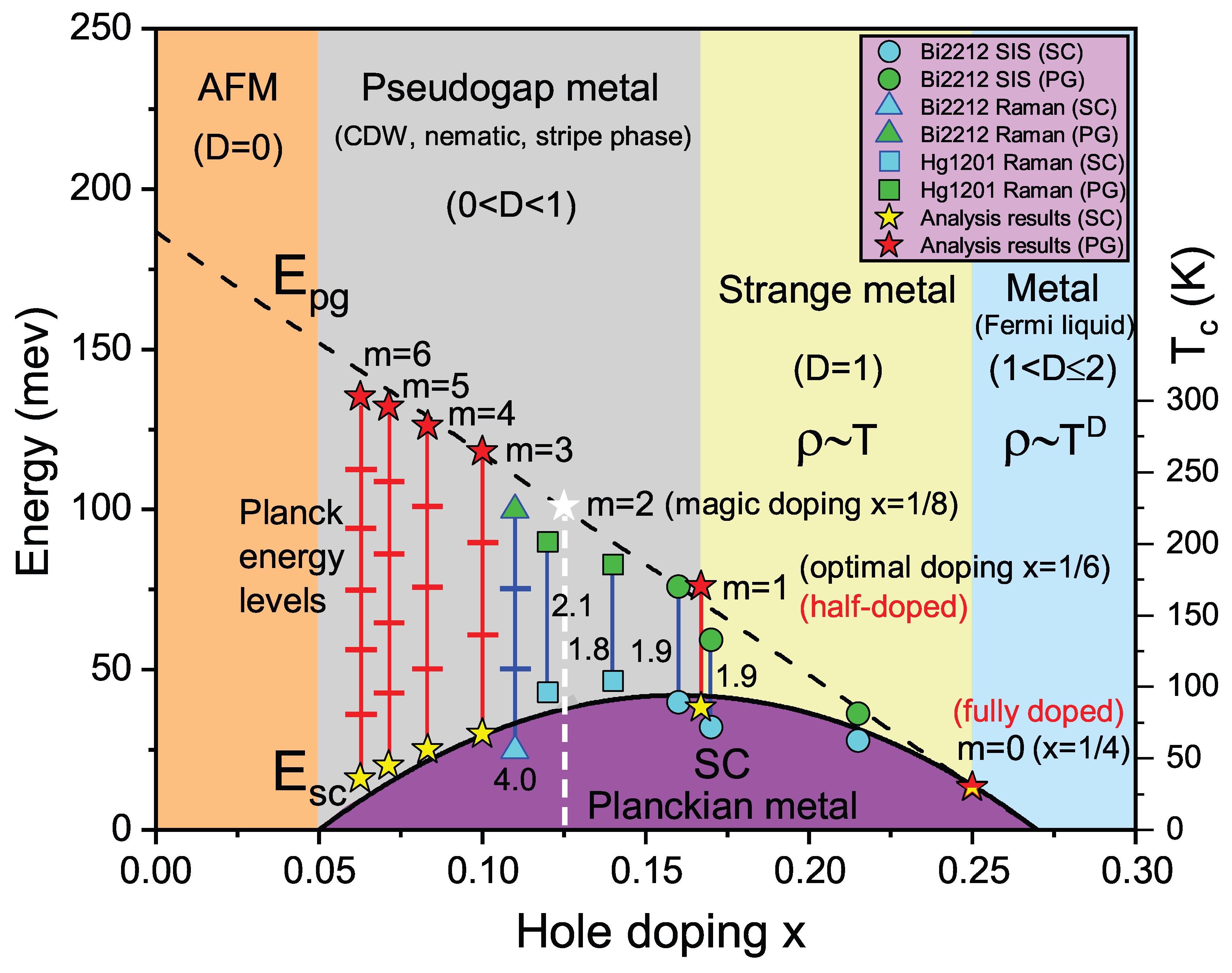

Pseudogap, Strange Metal, Linear Dependence and Phase Diagram

Two perfect linearities represent two major puzzles in condensed matter physics. In cuprate superconductors, experiments such as tunneling spectroscopy and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) have shown that the pseudogap decreases linearly with hole-doping concentration, deviating from the -shaped evolution of

[

29]. In the overdoped regime of HTSCs (the strange metal state), the normal-state resistivity exhibits auniversal linear dependenceon temperature [

30]. We propose a theoretical framework to explain these two phenomena within our current model.

The peculiar pseudogap exhibited by HTSCs in the normal state has been extensively verified by experiments. However, its origin and relationship with the superconducting mechanism remain controversial. Notably, the pseudogap strongly depends on the doping concentration. Through analyzing extensive experimental data, Hüfner et al. concluded the coexistence of two energy scales in HTSCs [

29], as shown in

Figure 4. They found that the superconducting energy scale follows a dome-shaped curve (denoted as

meV), while the pseudogap can be represented by a linear relationship

meV.

Interestingly, it will be shown that the integer

m in Eq. (

6) governs the superconducting properties and exhibits a remarkably close correlation with the pseudogap. We find that the pseudogap

and the superconducting energy scale

satisfy the following quantization relationship:

Figure 4 shows

exhibits a dome-shaped dependence on doping concentration

x (yellow stars), while

decreases linearly with

x (red stars). This gap discrepancy stems from their origins:

originates from the Planck ground state, and

from Planck excited states. As in

Figure 2A, when

(saturation occupancy), all polyhedral quantum wells in the 1D chain are occupied, closing the pseudogap. Reducing doping creates vacancies, gradually opening the pseudogap. At optimal doping (

, half-filling in

Figure 2B),

completely opens to twice

, corresponding to electron transitions from the ground to first excited state. Four sets of experimental data near optimal doping confirm

, indicating half-filling dominance. The 1/8 anomaly suppresses superconductivity in the underdoped region, preventing

(white stars). At

, three vacancies between quantum wells (

Figure 2D) induce a third excited-state pseudogap with

, matching the quadruple

signal (triangles) near

. Asmincreases, excited-state energy levels rise, driving the pseudogap to depend linearly on doping. As shown in

Figure 2A to D and Eq. (

7), the superconducting phase arises from doped quantum well electrons (conducting domains), while undoped vacancies (insulating domains) form the pseudogap phase. These two phases are a contradictory unity of competition and unity [

28], with their proportions summing to one.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, besides the purple superconducting region (referred to here as the Planck metallic state), the high-temperature superconducting phase diagram can be divided into four areas based on doping: orange for undoped antiferromagnetic Mott insulator, gray for underdoped pseudogap metal, yellow for strange metal, and blue for Fermi liquid. The dimension

D in the phase diagram represents the charge-ordered phase and measures electron behavior in the normal state. Our research focuses on the anomalous resistivity behavior of strange metals, which corresponds to the mixed state between full doping (

Figure 2A) and half-doping (

Figure 2B), with the doping concentration expressed as:

where

and

are the proportions of the two states, satisfying

.

The most critical feature of the mixed state defined by Eq. (

8) is that it can ensure the

-shift stability in

Figure 1E and the quasi-one-dimensional charge order and conductivity characteristics (

Figure 2, A and B). Consequently, the strange metal arising from this mixed state necessarily satisfies

. Generally, the temperature-dependent resistivity can be expressed as:

. For the strange metal’s mixed state (

), naturally leading to the universal linear temperature dependence of electrical resistivity

. When

(saturation doping concentration), excess doping disrupts the

-shift stability and quasi-one-dimensional charge order, in this case

; as doping increases, the

component emerges and increases, and the resistivity exhibits the conventional Fermi liquid behavior of metals.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Haihu Wen, Yayu Wang, Liling Sun, and Ningning Wang for sharing and the helpful discussion of their experimental results. The author would like to acknowledge Duan Feng for his invaluable suggestions and helpful discussions at the early stage of this research. The author is grateful to Shusheng Jiang, Changde Gong, and Dingyu Xing for their unwavering encouragement and support of the research process during his stay at Nanjing University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- B. Keimer, S. A. Kivelson, M. R. Norman, S. Uchida, J. Zaanen, Nature 518, 179–186 (2015).

- P. A. Lee, N. Nagaosa, X. G. Wen, Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 17–85 (2006).

- H. Yang, et al., Science 344, 608–611 (2014).

- P. W. Phillips, et al., Science 377, eabh4273 (2022).

- P. Giraldo-Gallo, et al., Science 361, 479–481 (2018).

- P. W. Anderson, Science 31, 1705–1707 (2007).

- S. Dal Conte, et al., Science 335, 1600–1603 (2012).

- J. Zaanen, Nature 430, 512–513 (2004).

- S. Badoux, et al., Nature 531, 210–214 (2016).

- C. C. Tsui, J. R. Kirtley, Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 969–1016 (2000).

- D. Fausti, et al., Science 331, 189–191 (2011).

- R. Comin, et al., Science 343, 390–392 (2014).

- E. Dagotto, Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 763 (1994).

- . Fischer, et al., Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 353–419 (2007).

- D. N. Basov, T. Timusk, Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 721–779 (2005).

- C. M. Varma, Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 031001 (2020).

- Y. Kamihara, T. Watanabe, M. Hirano, H. Hosono, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296-3297 (2008).

- H. L. Sun, et al., Nature 621, 493–498 (2023).

- S. Martin, et al., Phys. Rev. B 41, 846 (1990).

- O. Gunnarsson, M. Calandra, J. E. Han, Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 1085–1099 (2003).

- L. Chen, et al., Science 382, 907–911 (2023).

- J. Yuan, Q. Chen, K. Jiang, et al., Nature 602, 431–436 (2022).

- J. Jiang, et al., Nat. Phys. 19, 365–371 (2023).

- A. Coe, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 236205 (2025).

- S. A. Hartnoll, A. P. Mackenzie, Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 041002 (2022).

- G. Grissonnanche, et al., Nature 595, 667–672 (2021).

- T. Hanaguri, et al., Nature 430, 1001–1005 (2004).

- M. R. Norman, D. Pines, C. Kallin, Adv. Phys. 54, 715–733 (2005).

- S. Hüfner, et al., Rep. Prog. Phys. 71, 062501 (2008).

- A. Legros, et al., Nat. Phys. 15, 142–147 (2019).

- J. G. Bednorz, K. A. Müller, Z. Phys. B 64, 189–193 (1986).

- S. S. Ye, et al., Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.09260 (2023).

- H. Li, et al., npj Quantum Mater. 8, 18 (2023).

- L. Gao, et al., Phys. Rev. B 50, 4260–4263 (1994).

- Z. A. Ren, et al., Chin. Phys. Lett. 25, 2215–2216 (2008).

- R. A. Cooper et al., Science 323, 603–607 (2009).

- L. Sun, et al., Nature 483, 67–69 (2012).

- X. H. Chen, et al., Nature 453, 761–762 (2008).

- T. Xie, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 267003 (2018).

- B. Geisler, et al., npj Quantum Mater. 9, 38 (2024).

- Y. Zhu, et al., Nature 631, 531–536 (2024).

- N. Wang, et al., Nature 634, 579–584 (2024).

- T. Wu, et al., Nature 477, 191–194 (2011).

- S. Komiya, H. D. Chen, S. C. Zhang, Y. Ando, Phy. Rev. Lett. 94, 207004 (2005).

- D. Qiu, et al., Adv. Phys. 33, 2006124 (2021).

- Y. Yu, et al., Nature 575, 156–163 (2019).

- V. Fatemi, et al., Science 362, 926–929 (2018).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).