Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The General Framework: Strange Metallicity in Cuprates and Elsewhere

1.2. The Shrinking Fermi Liquid Scenario

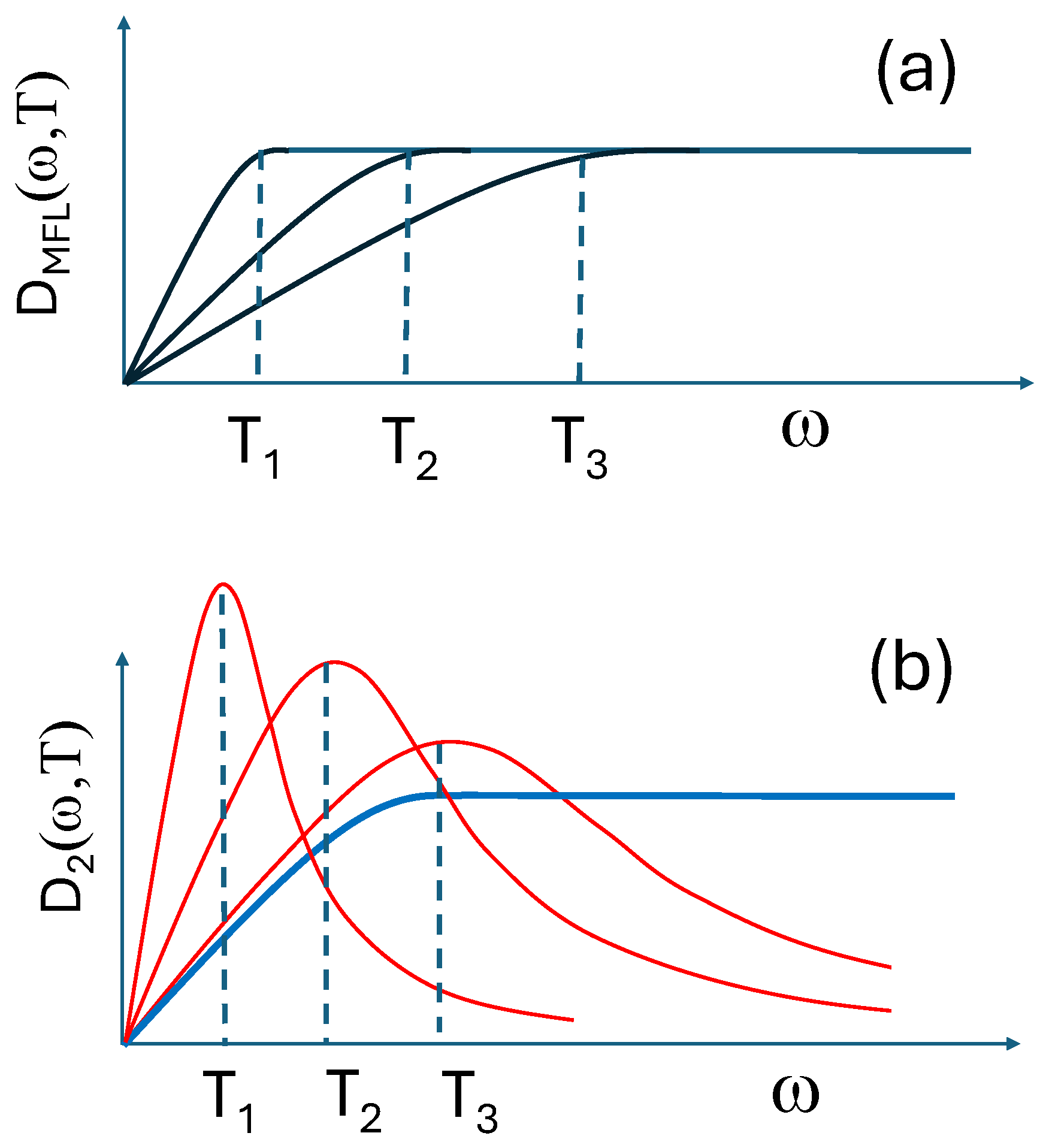

2. Optical Conductivity within the SFL Scenario

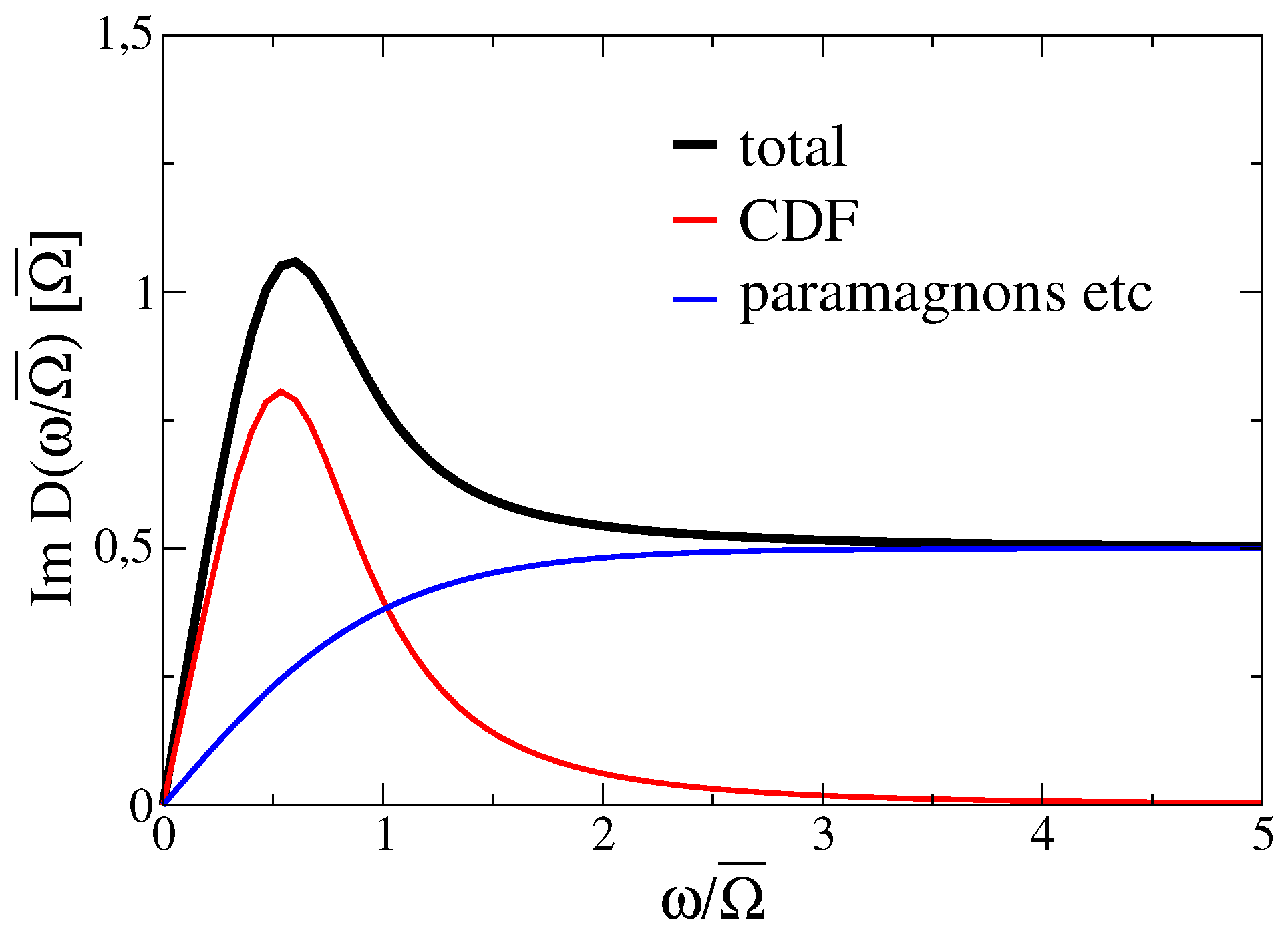

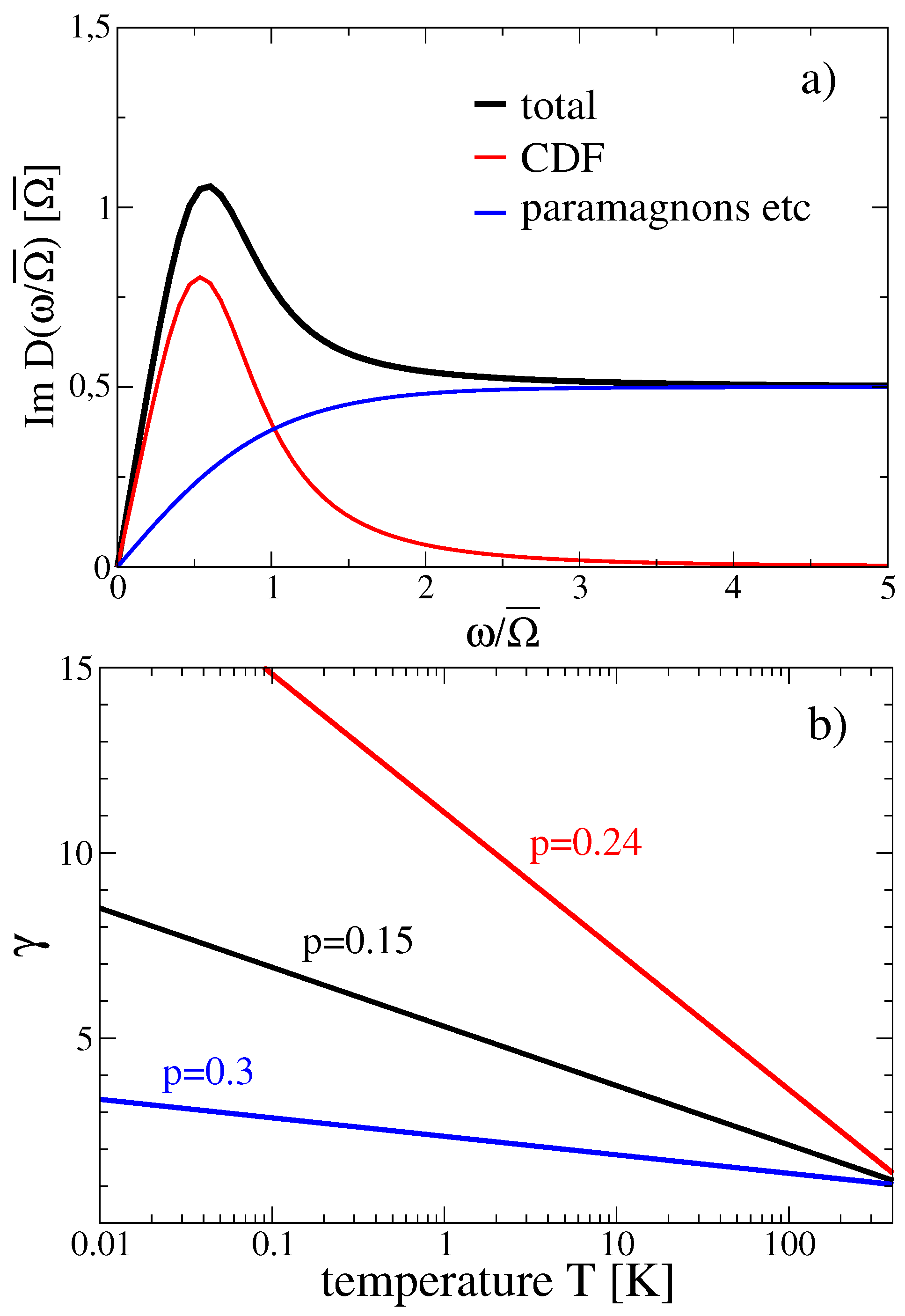

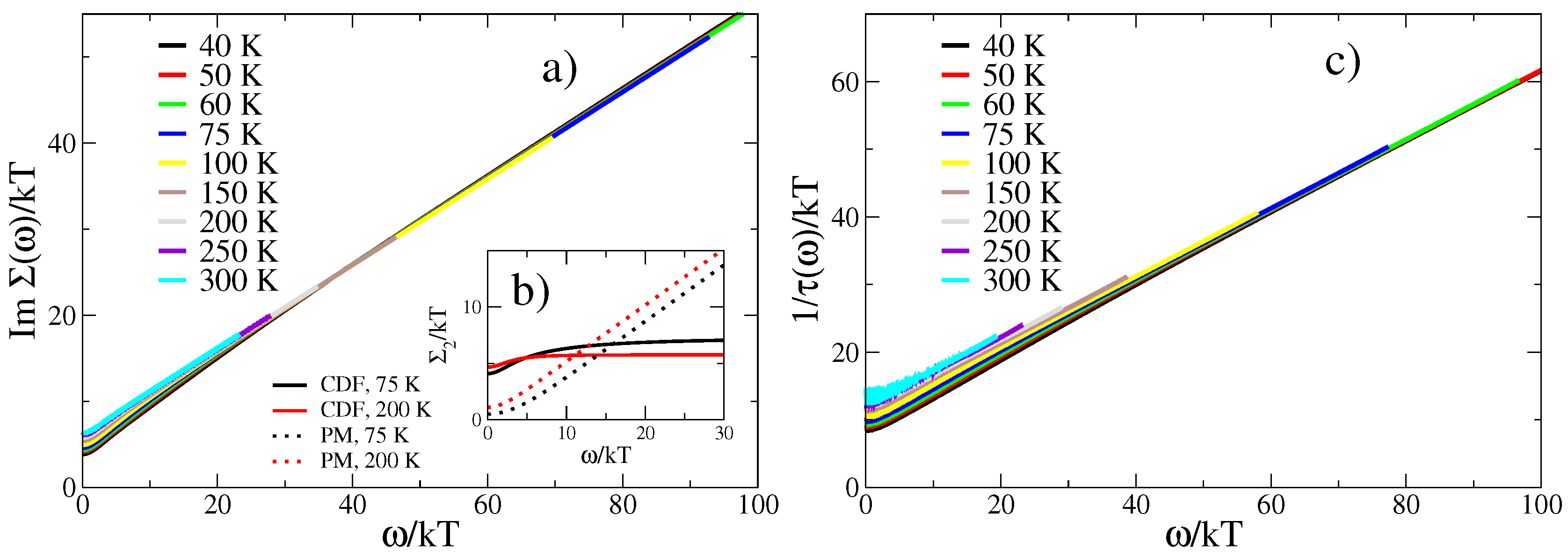

2.1. The Experimental Characterization for Charge Density Fluctuations

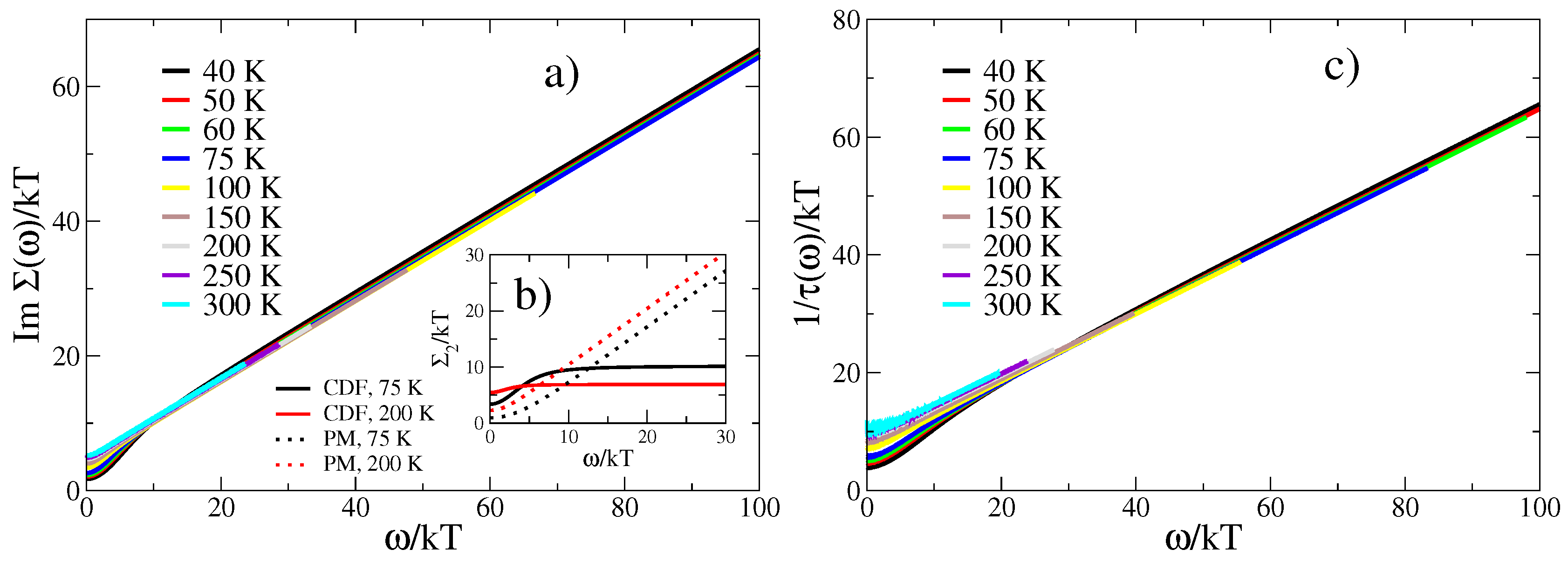

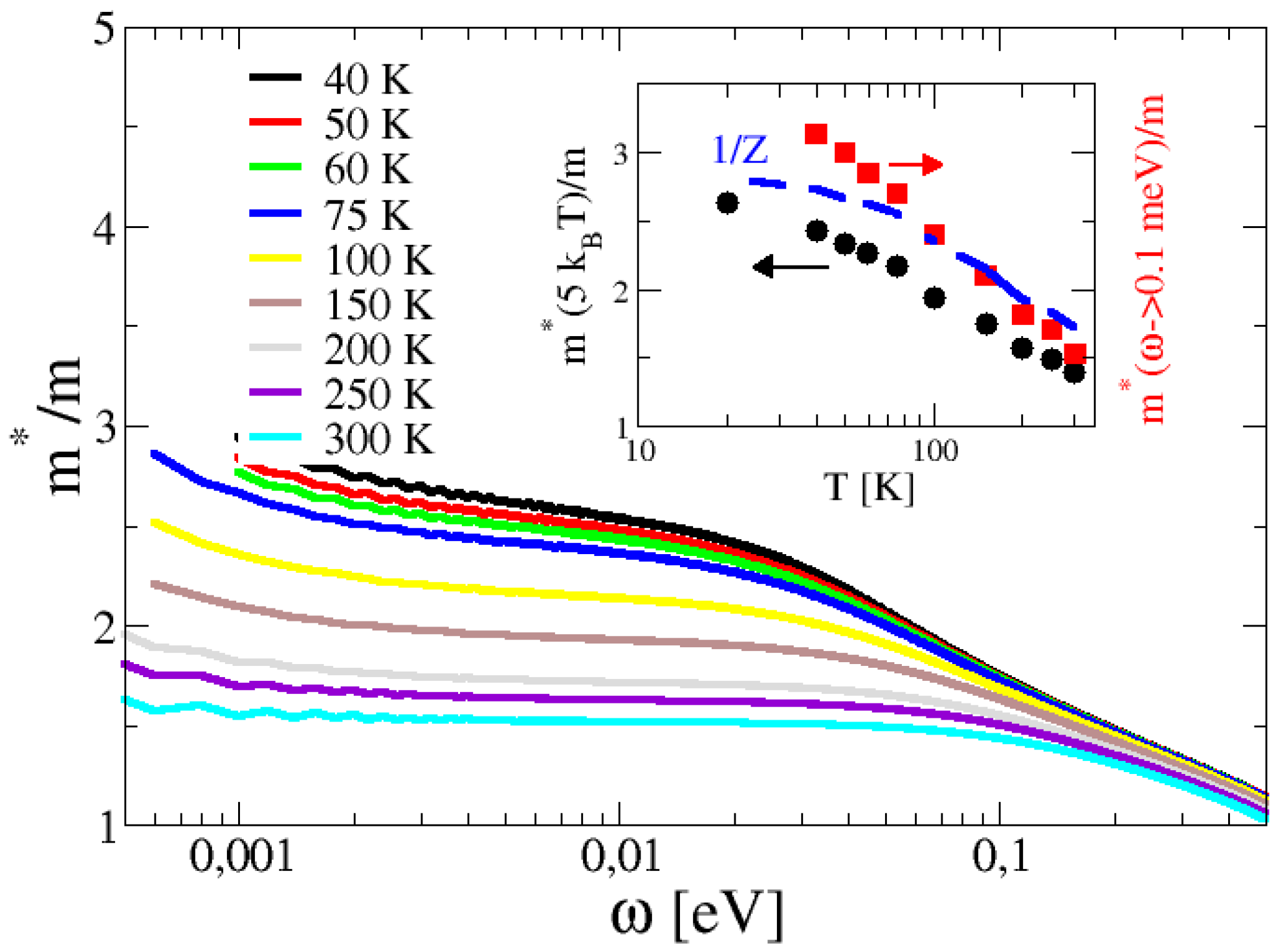

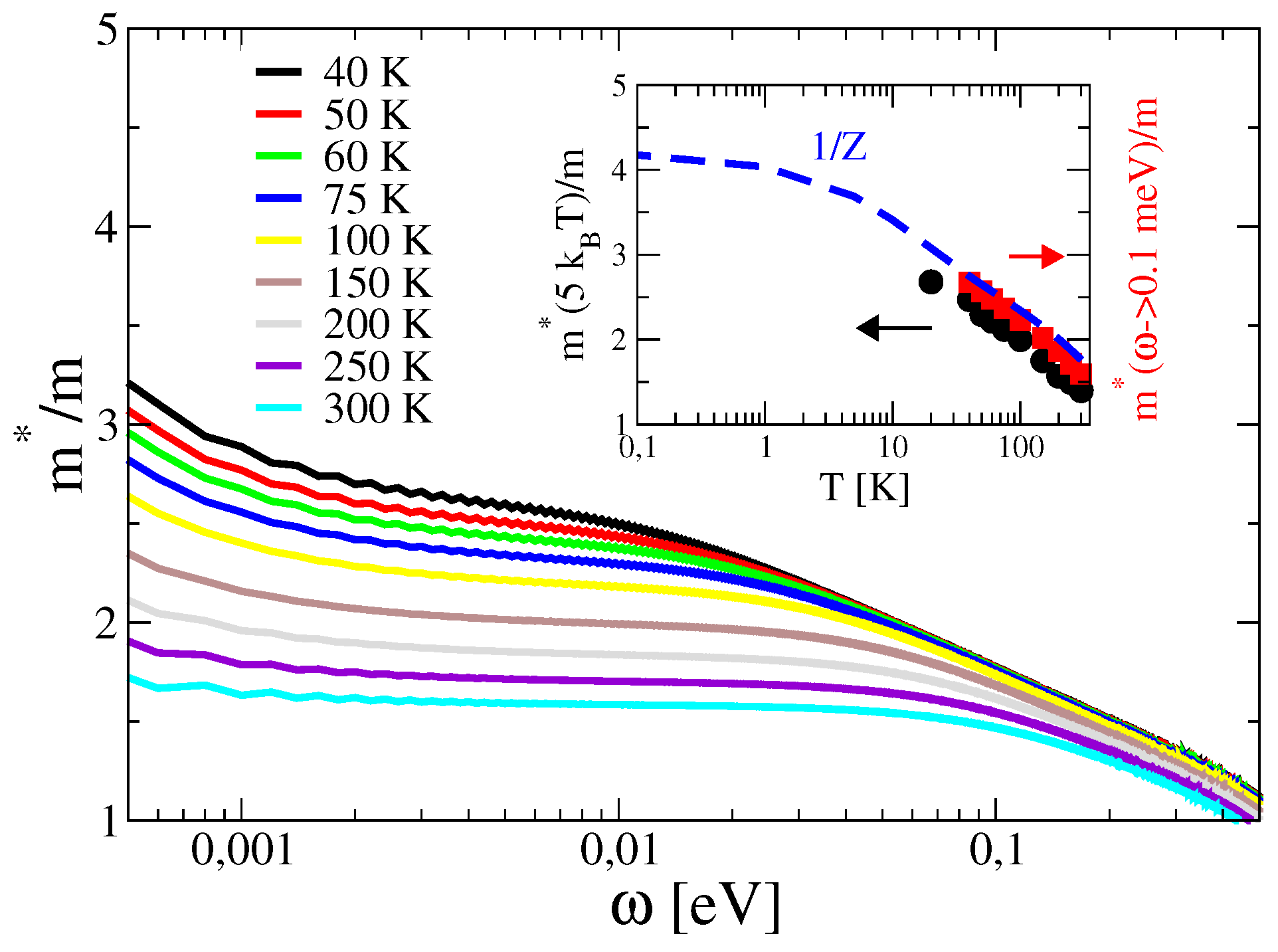

2.2. Optical Conductivity Calculation

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Results for Constant γ=1

References

- R. L. Greene. The strange metal state of the high-Tc cuprates. Physica C 2023, 612, 1354319. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Hussey, C. N. E. Hussey, C. Duffy. Strange metallicity and high-Tc superconductivity: Quantifying the paradigm. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 985-987. [CrossRef]

- S. Sachdev. Strange Metals and Black Holes: Insights From the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev Model. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Patel; H. Guo; I. Esterlis; S. Sachdev. Universal theory of strange metals from spatially random interactions. Science 2023, 381, 790. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Patel; J. McGreevy; D. P. Arovas; S. Sachdev. Magnetotransport in a model of a disordered strange metal. Phys. Rev. X 2018, 8, 021049. [CrossRef]

- E. Tulipman; N. Bashan; J. Schmalian; E. Berg. Solvable models of two-level systems coupled to itinerant electrons: Robust non-Fermi liquid and quantum critical pairing. arXiv:2404. 0653. [CrossRef]

- R. Arpaia; S. Caprara; R. Fumagalli; G. De Vecchi; Y. Y. Peng; E. Anderson; D. Betto; G. M. De Luca; N. B. Brookes; F. Lombardi; M. Salluzzo; L. Braicovich; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli; G. Ghiringhelli. Dynamical charge density fluctuations pervading the phase diagram of a Cu-based high-Tc superconductor, Science 2019, 365, 906-910. [CrossRef]

- R., Arpaia; L., Martinelli; M. M. Sala, S. R. Arpaia; L. Martinelli; M. M. Sala, S. Caprara; A. Nag; N. B. Brookes; P. Camisa; Q. Li; Q. Gao; X. Zhou; M. Garcia-Fernandez; K.-J. Zhou; E. Schierle; T. Bauch; Y. Y. Peng; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli; F. Lombardi; L. Braicovich; G. Ghiringhelli. Signature of quantum criticality in cuprates by charge density fluctuations. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7198. [CrossRef]

- G. Seibold; R. Arpaia; Y. Y. Peng; R. Fumagalli; L. Braicovich; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli; G. Ghiringhelli; S. Caprara. Strange metal behaviour from charge density fluctuations in cuprates. Commun. Phys. 2021, 4, 7. [CrossRef]

- S. Caprara; C. Di Castro; G. Mirarchi; G. Seibold; M. Grilli. Dissipation-driven strange metal behavior. Commun. Phys. 2022, 5, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- M. Grilli; C Di Castro; G. Mirarchi; G. Seibold; S. Caprara. Dissipative Quantum Criticality as a Source of Strange Metal Behavior. Symmetry 2023, 15, 569. [CrossRef]

- G. Mirarchi; M. Grilli; G. Seibold; S. Caprara. The Shrinking Fermi Liquid Scenario for Strange-Metal Behavior from Overdamped Optical Phonons. Condensed Matter 2024, 9, 14. [CrossRef]

- D. van der Marel; H. J. A. Molegraaf; J. Zaanen; Z. Nussinov; F. Carbone; A. Damascelli; H. Eisaki; M. Greven; P. H. Kes; M. Li. Quantum critical behaviour in a high-Tc superconductor. Nature 2003, 425, 271. [CrossRef]

- D. van der Marel; F. Carbone; A.B. Kuzmenko; E. Giannini. Scaling properties of the optical conductivity of Bi-based cuprates. Annals of Physics 2006, 321, 1716. [CrossRef]

- E. v. Heumen; X. Feng; S. Cassanelli; L. Neubrand; L. de Jager; M. Berben; Y. Huang; T. Kondo; T. Takeuchi; J. Zaanen. Strange metal electrodynamics across the phase diagram of Bi2-xPbxSr2-yLayCuO6+δ cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 054515. [CrossRef]

- B. Michon; C. Berthod; C. W. Rischau; A. Ataei; L. Chen; S. Komiya; S. Ono; L. Taillefer; D. van der Marel; A. Georges. Reconciling scaling of the optical conductivity of cuprate superconductors with Planckian resistivity and specific heat. Nature Communications 2023 14:3033. [CrossRef]

- A. El Azrak; R. Nahoum; N. Bontemps; M. Guilloux-Viry; C. Thivet; A. Perrin; S. Labdi; Z. Z. Li; H. Raffy. Infrared properties of YBa2Cu3O7 and Bi2Sr2Can-1CunO2n+4 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 9846. [CrossRef]

- J. Hwang; T. Timusk; G. D. Gu. Doping dependent optical properties of Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. J. Phys.: Condens. Mat. 2007, 19, 125208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. M. Varma; P. B. Littlewood; S. Schmitt-Rink; E. Abrahams; A. E. Ruckenstein. Phenomenology of the normal state of Cu-O high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 63, 1996. [CrossRef]

- C. Girod; D. LeBoeuf; A. Demuer; G. Seyfarth; S. Imajo; K. Kindo; Y. Kohama; M. Lizaire; A. Legros; A. Gourgout; H. Takagi; T. Kurosawa; M. Oda; N. Momono; J. Chang; S. Ono; G.-Q. Zheng; C. Marcenat; L. Taillefer; T. Klein. Normal state specific heat in the cuprate superconductors La2-xSrxCuO4 and Bi2+ySr2-x-yLaxCuO6+δ near the critical point of the pseudogap phase. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 214506. [CrossRef]

- G. Ghiringhelli; M. Le Tacon; M. Minola; S. Blanco-Canosa; C. Mazzoli; N. B. Brookes; G. M. De Luca; A. Frano; D. G. Hawthorn; F. He; T. Loew; M. Moretti Sala; D. C. Peets; M. Salluzzo; E. Schierle; R. Sutarto; G. A. Sawatzky; E. Weschke; B. Keimer; L. Braicovich. Long-range incommensurate charge fluctuations in (Y,Nd)Ba2Cu3O6+x. Science 2012, 337, 821. [CrossRef]

- J. Chang; E. Blackburn; A. T. Holmes; N. B. Christensen; J. Larsen; J. Mesot; R. Liang; D. A. Bonn; W. N. Hardy; A. Watenphul; M. V. Zimmermann; E. M. Forgan; S. M. Hayden. Direct observation of competition between superconductivity and charge density wave order in YBa2Cu3O6.67. Nature Phys. 2012, 8, 871. [CrossRef]

- S. Blanco-Canosa; A. Frano; E. Schierle; J. Porras; T. Loew; M. Minola; M. Bluschke; E. Weschke; B. Keimer; M. Le Tacon. Resonant x-ray scattering study of charge-density wave correlations in YBa2Cu3O6+x. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 054513. [CrossRef]

- C. Castellani; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli. Singular quasiparticle scattering in the proximity of charge instabilities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 4650. [CrossRef]

- C. Castellani; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli. Non-Fermi-liquid behavior and d-wave superconductivity near the charge-density-wave quantum critical point. Z. Phys. B 1996, 103, 137. [CrossRef]

- C. Castellani; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli. Stripe formation: A quantum critical point for cuprate superconductors. J. of Phys. and Chem. of Sol. 1998, 59, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Seibold; F. Becca; F. Bucci; C. Castellani; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli. Spectral properties of incommensurate charge-density wave systems. Eur. Phys. J. B 2000, 13, 87. [CrossRef]

- S. Andergassen; S. Caprara; C. Di Castro; M. Grilli. Anomalous Isotopic Effect Near the Charge-Ordering Quantum Criticality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 056401. [CrossRef]

- R. Arpaia; G. Ghiringhelli. Charge Order at High Temperature in Cuprate Superconductors. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 2021, 90, 111005. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Varma; Z. Nussinov; W. van Saarloss. Singular or non-Fermi liquids. Phys. Rep. 2002, 361, 267. [CrossRef]

- G. R. Stewart. Non-Fermi-liquid behavior in d- and f -electron metals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 797. [CrossRef]

- J. A. N. Bruin; H. Sakai; R. S. Perry; A. P. Mackenzie. Similarity of scattering rates in metals showing T-linear resistivity. Science 2013, 339, 804. [CrossRef]

- M. Taupin; S. Paschen. Are heavy fermion strange metals Planckian. Crystals 2022, 12, 251. [CrossRef]

- P. W. Phillips; N. E. Hussey; P. Abbamonte. Stranger than metals, Science 2022, 377,169. [CrossRef]

- S. Ciuchi; S. Fratini. Strange metal behavior from incoherent carriers scattered by local moments. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 235173. [CrossRef]

- S. Martin; A. T. Fiory; R. M. Fleming; L. F. Schneemeyer; J. V. Waszczak. Normal-state transport properties of Bi2+xSr2-yCuO6+δ crystals. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 41, 846(R). [CrossRef]

- P. Fournier; P. Mohanty; E. Maiser; S. Darzens; T. Venkatesan; C. J. Lobb; G. Czjzek; R. A. Webb; R. L. Greene. Insulator-Metal Crossover near Optimal Doping in Pr2-xCexCuO4: Anomalous Normal-State Low Temperature Resistivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 4720. [Google Scholar]

- R. Daou; N. Doiron-Leyraud; D. LeBoeuf; S. Y. Li; F. Laliberté; O. Cyr-Choinière; Y. J. Jo; L. Balicas; J.-Q. Yan; J.-S. Zhou; J. B. Goodenough; L. Taillefer. Linear temperature dependence of resistivity and change in the Fermi surface at the pseudogap critical point of a high-Tc superconductor. Nature Physics 2009, 5, 31. [CrossRef]

- R. Hlubina; T. M. Rice. Resistivity as a function of temperature for models with hot spots on the Fermi surface. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 51, 9253. [CrossRef]

- S. Caprara; M. Grilli; C. Di Castro; T. Enss. Optical conductivity near finite-wavelength quantum criticality. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 140505(R). [CrossRef]

- A. Legros; S. Benhabib; W. Tabis; F. Laliberté; M. Dion; M. Lizaire; B. Vignolle; D. Vignolles; H. Raffy; Z. Z. Li; P. Auban-Senzier; N. Doiron-Leyraud; P. Fournier; D. Colson; L. Taillefer; C. Proust. Universal T-linear resistivity and Planckian dissipation in overdoped cuprates. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 142. [CrossRef]

- B. Michon; C. Girod; S. Badoux; J. Kacmarcik; Q. Ma; M. Dragomir; H. A. Dabkowska; B. D. Gaulin; J. S. Zhou; S. Pyon; T. Takayama; H. Takagi; S. Verret; N. Doiron-Leyraud; C. Marcenat; L. Taillefer; T. Klein. Thermodynamic signatures of quantum criticality in cuprate superconductors, Nature 2019, 567, 218-222. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Norman; A. V. Chubukov. High-frequency behavior of the infrared conductivity of cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 140501R. [CrossRef]

- P. B. Allen. Electron self-energy and generalized Drude formula for infrared conductivity of metals. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 054305. [CrossRef]

- P. B. Allen. Electron-Phonon Effects in the Infrared properties of Metals, Phys. Rev. B 1971, 3, 305. [CrossRef]

- W. Götze; P. Wölfle. Homogeneous dynamical conductivity of simple metals. Phys. Rev. B 1972, 6, 1226. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Allen; J. C. Mikkelsen. Optical properties of CrSb, MnSb, NiSb, and NiAs. Phys. Rev. B 1977, 15, 2952. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Basov; R. D. Averitt; D. van derMarel; M. Dressel; K. Haule. Electrodynamics of correlated electron materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 471. [CrossRef]

- H.K. Pala; V.I. Yudson; D.L. Maslov. Resistivity of non-Galilean-invariant Fermi- and non-Fermi liquids. Lithuanian Journal of Physics 2012, 52, 142-164. [CrossRef]

- G. Kotliar; E. Abrahams; A. E. Ruckenstein; C. M. Varma; P. B. Littlewood; S. Schmitt-Rink. Long-Wavelength Behavior, Impurity Scattering and Magnetic Excitations in a Marginal Fermi Liquid. EPL 1991, 15, 655. [CrossRef]

- S. Caprara; C. Di Castro; S. Fratini; M. Grilli. Anomalous Optical Absorption in the Normal State of Overdoped Cuprates Near the Charge-Ordering Instability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 147001. [CrossRef]

- S. Caprara; C. Di Castro; T. Enss; M. Grilli. Low-energy signatures of charge and spin fluctuations in Raman and optical spectra of the cuprates. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2008, 69, 2155-2159. [CrossRef]

- S. Fratini; S. Ciuchi. Displaced Drude peak and bad metal from the interaction with slow fluctuations. SciPost Phys. 2021, 11, 039. [CrossRef]

- S. Fratini; K. Driscoll; S. Ciuchi;. Ralko. A quantum theory of the nearly frozen charge glass. SciPost Phys. 2023, 14, 124. [CrossRef]

- H. Rammal; A. Ralko; S. Ciuchi; S. Fratini. Transient localization from the interaction with quantum bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 266502. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).