1. Introduction

Product traceability, especially in the food industry, has gained importance in recent years due to the demand for greater transparency, safety, and sustainability in supply chains (SC). [

1]. This traceability is based on the ability to recognize key traceability events and preserve the integrity of the associated data, which allows the prevention of fraud, ensuring the authenticity of the origin [

2]. This process does not occur automatically; companies play a crucial role in recording operational data, which requires that each stage of the chain collects relevant data to ensure transparency [

3,

4].

Regulations and certifications have promoted the adoption of systems focused on traceability, helping to create more equitable conditions among companies and fostering improvements in transparency and control throughout the supply chain [

5]. However, these efforts still face critical challenges in legacy systems, such as a lack of transparency and interoperability that complicates traceability. [

6].

As a result, one of the main challenges lies in the collection and management of information. In the initial stages, traceability is compromised by sensor failures, which are vulnerable to interference during data transmission and by manual manipulation of the information. This technological fragility generates inconsistencies in the records related to the origin and condition of the product, affecting its traceability throughout the entire chain. [

7].

These technical limitations are added to the lack of interoperability between traceability platforms, which complicates seamless communication between the different systems involved in the supply chain. The absence of common standards for information exchange is particularly problematic in contexts composed of multiple small and medium-sized companies (SMEs) with limited technological capabilities [

8,

9]. This not only generates data overload but also makes it difficult to detect failures related to product quality or safety. [

10].

In this context, this study aims to design a web application based on blockchain technology to optimize traceability and efficiency in agricultural supply chains. To conclude, the objective is to analyze previous solutions with this technology in traceability systems, to interpret their approaches and to provide the foundation for the design of a solution that addresses the specific needs of the agricultural sector.

2. Related Works

Recent technological advances have favored the digitization of supply chains, which has significantly improved the traceability and visibility of processes [

11]. In this context, two prominent platforms IBM Food Trust at Wal-Mart and SmartBeanFutures for Colombian coffee offer innovative blockchain-based approaches. The following sections describe the purpose, and the specific problems addressed by each of these systems.

2.1. Blockchain in Supply Chain Traceability

IBM Food Trust was developed to address the slow and unreliable traceability of fresh produce within the Wal-Mart supermarket chain, which traditionally took up to six days to track the source of a batch. The platform employs enterprise blockchain technology on the Ethereum network adapted by IBM, with smart contracts that securely record data on batches, origin, processing, and transportation in real-time. Its implementation spanned from production to consumption at Wal-Mart, performing traceability tests with real data from multiple batches and measuring query times. The result in traceability time of its implementation reduced from six days to 2.2 seconds and achieved a 15.3 % decrease in food waste, increasing trust between parties in the chain. The tests concluded that blockchain can contribute to traceability in large supply chains with some challenges in adoption (costs, integration, adaptation) [

12]. IBM Food Trust presents a large-scale success story demonstrating the viability of enterprise blockchain in mass retail.

2.2. Web Applications with Traceability Technologies

The SmartBeanFutures web platform was developed to facilitate transparent and secure records of every agricultural transaction for smallholder farmers. This application uses Ganache, Truffle, and MetaMask to deploy and test smart contracts in blockchain networks, and it introduces NFTs as unique product identifiers to ensure authenticity and traceability. During its development, it carried out smart contract simulations to validate quality attributes and then tested the prototype with several coffee farmers in Colombia, evaluating usability and the robustness of the system. An increase in transparency and trust between producers and buyers, a reduction of intermediaries and an opening of access to international markets for small coffee growers were observed, although without specifying exact quantitative metrics. The developers concluded that smart contracts helped the efficiency and traceability of the process, especially in critical stages such as verification and fulfillment of conditions. [

13]. SmartBeanFutures extends the concept of smart contracts and NFTs to the coffee sector, highlighting its inclusion of small producers.

2.3. Blockchain in the Agricultural Supply Chain

Blockchain technology is proposed as an effective solution to the problems of traceability, transparency, and authenticity in the agricultural supply chains. The ability to record events in an unchangeable way allows monitoring of every stage of the product flow, from production to final consumption, reducing the risk of fraud and improving operational efficiency [

6]. Each block that is added to the chain becomes immutable and cannot be altered or removed by any single participant. [

14].

2.4. Impacts and Benefits of Using Blockchain

Table 1 presents Blockchain use cases along with their descriptions and key benefits, offering insight into features and immutability that optimize traceability, security, and efficiency in sectors such as supply chains.

3. Methodology

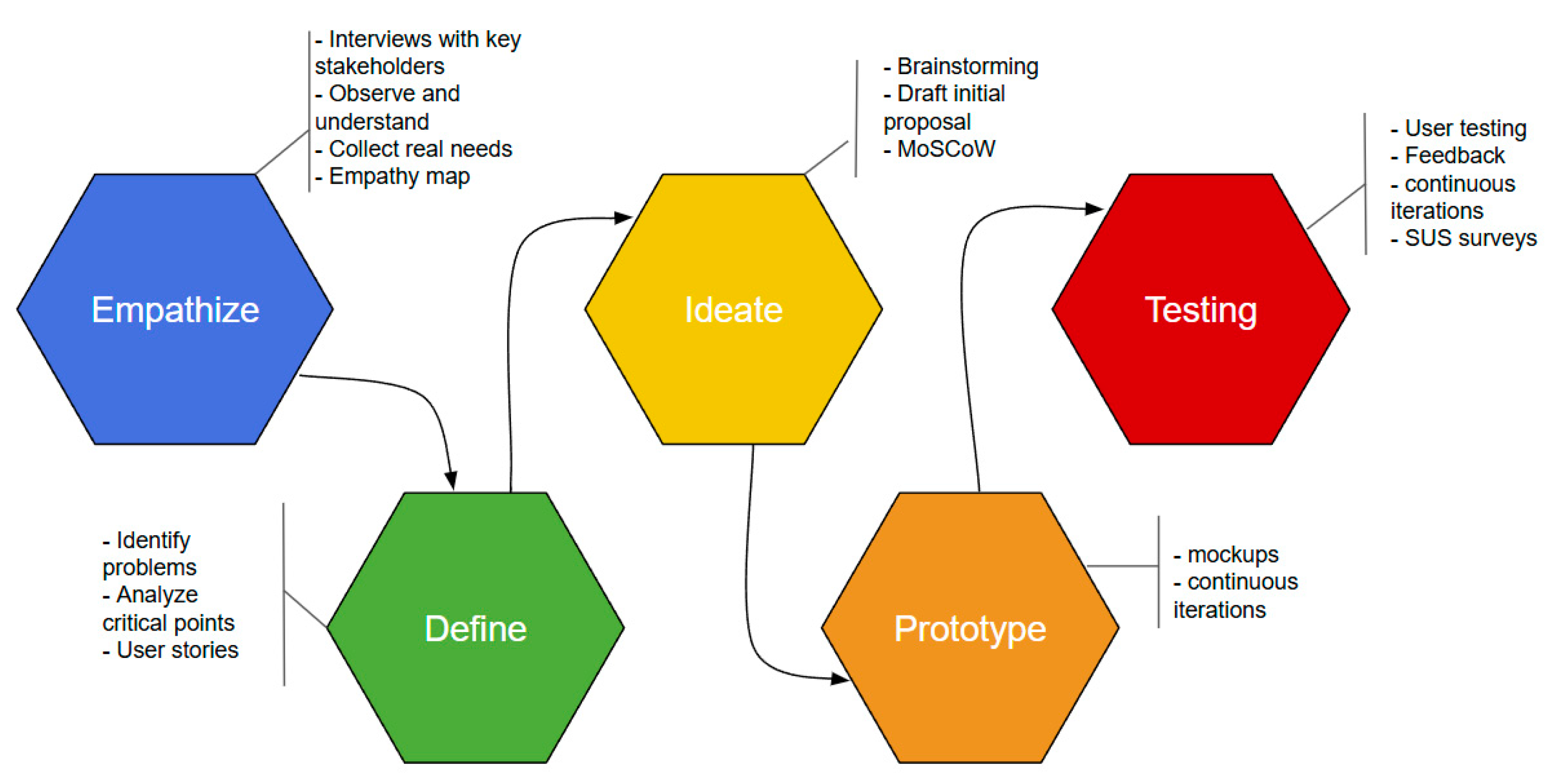

The design of the proposed application was focused on user experience, which aims to ensure an intuitive and easy-to-understand interface. The methodology used was Design Thinking which focuses on human-centered solutions, iterative development, and collaborative problem-solving. [

20].

Figure 1 illustrates the methodology as applied in this study.

3.1. Design Thinking Method

Composed of five phases: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. This method allows design teams to promote interdisciplinary participation, empathy, and iteration as key principles during the technology creation process. [

21].

3.1.1. Empathize: Understand the Needs, Challenges, Emotions, Aspirations, and Fears of Users Through Interviews, Observation, Focus Groups, and Stakeholder Mapping [

21].

3.1.2. Define: Analyze the Information Collected and Formulate the Problem to Obtain a User Perspective for the Generation of Solutions [

22].

3.1.3. Ideate: Create Multiple Alternative Solutions to Consider Several Possible Outcomes [

23].

3.1.4. Prototyping: Create Tangible Versions of Selected Ideas that Are Aligned with the User's Objective [

24].

3.1.5. Testing: Conduct Usability Tests with Users to Obtain Feedback on Prototypes, Identify Problems, and Make Improvements Before Final Implementation [

25]. Tools Such as Standardized SUS (System Usability Scale) Surveys Provide a Quantitative Evaluation of How Easy it Is to Use the System from the User's Perspective. [

26].

Figure 1.

Design thinking process.

Figure 1.

Design thinking process.

4. Results

This section presents the results obtained in each phase of the Design Thinking methodology, applied to the design of a Blockchain-based web application to optimize traceability in the agricultural supply chain.

4.1. Empathize

Interviews and process analyses were conducted within a batch management workflow to identify key user needs. The following issues were highlighted:

Reliable traceability: Lack of product journey visibility generates mistrust and quality risks.

Data integrity: Concern about manipulable records; automatic and immutable validation is required.

Alerts and operational visibility: Need for visual indicators and stock and status notifications.

Usability: A simple and intuitive platform is required for non-technical users.

External transparency: Companies are seeking to demonstrate verified traceability to build customer confidence and maintain quality standards at the time of their audits.

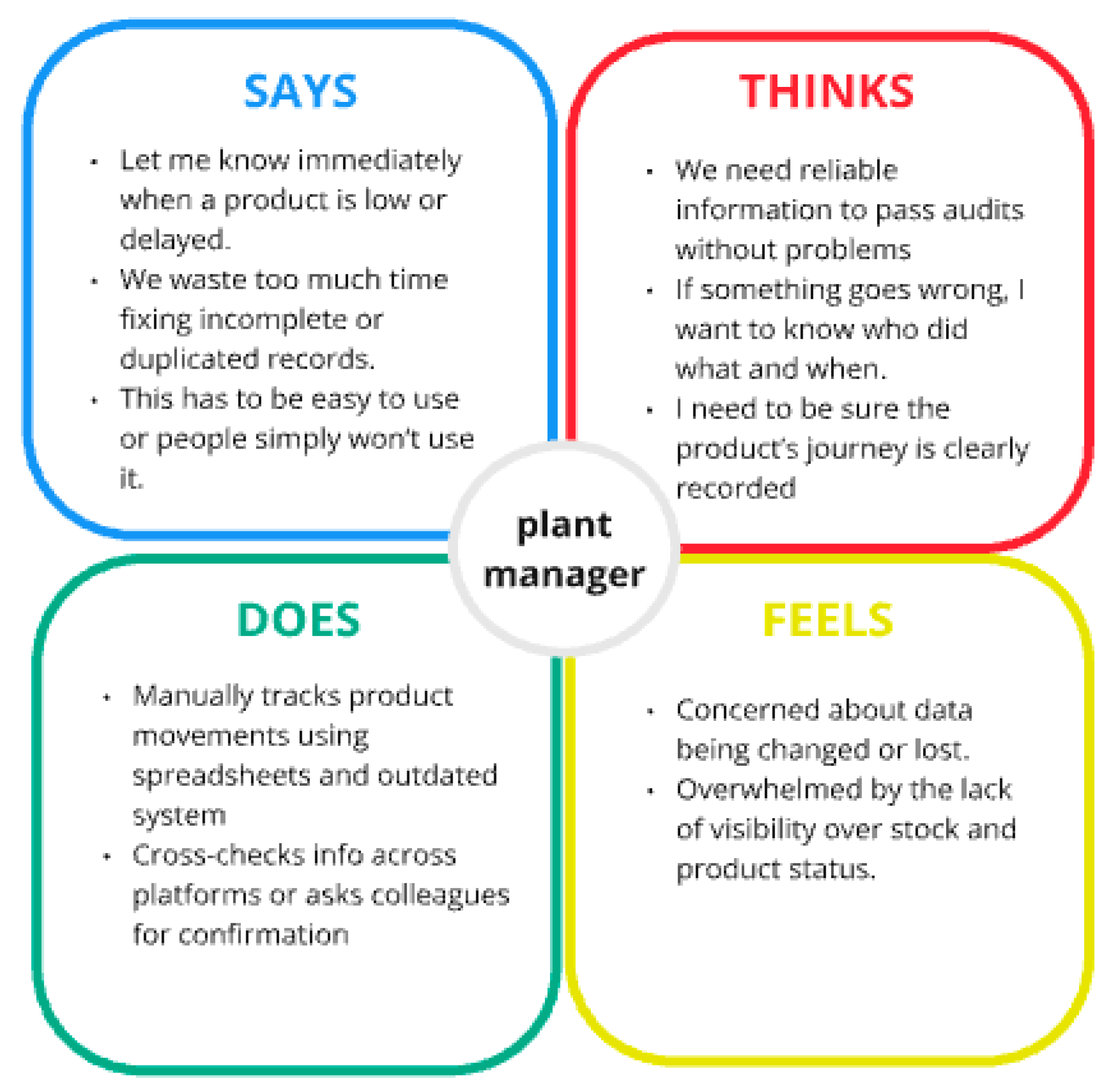

As a complement, an Empathy Map

Figure 2 was elaborated to represent the thoughts, emotions, actions, and expressions of the plant manager, one of the main actors in the system.

4.2. Define

Based on the previous analysis, the following were identified as priority requirements:

Recording and monitoring of batches in phases with traceability evidence.

Automatic generation of events and history in an immutable blockchain network.

User-friendly interface to register products, filter data, and consult traceability.

Secure access with defined roles for plant managers and auditors.

Problem statement: Based on these observations, the following central problem was identified, which gives rise to the solution.

The Peruvian agricultural supply chain faces limitations in traceability, unreliable records, and poor visibility of processes, which contribute to food losses, mistrust among stakeholders, and low operational efficiency. It is necessary to implement a digital solution that ensures reliable traceability, integrity of data, and an accessible interface for users with basic technical knowledge.

4.3. Ideate

During this phase, key assumptions and hypotheses were formulated to guide the initial design of the solution, making it possible to anticipate the context of use and validate the proposed technological approach.

Assumptions: To structure the development under realistic and feasible conditions, the following key assumptions were made:

It is assumed that end users have a stable internet connection to navigate the platform without interruptions.

Key users are assumed to have basic digital knowledge to interact with web interfaces.

It is assumed that companies in the agricultural sector will be willing to adopt a digital solution as long as it helps them to comply with regulations and improve the efficiency of their operations.

Hypotheses: Based on the defined assumptions and the information gathered in the previous stages, the following design hypotheses were developed, which served as a guide to focus the development of the solution on clear goals:

If blockchain technology is used to register traceability events, then data integrity will be guaranteed, avoiding subsequent manipulations of the initial data.

If the system interface is intuitive and clear, then it will facilitate its adoption for all users, thus decreasing the need for additional training.

If automated processes through smart contracts, then the response time in critical operations will be reduced, increasing the overall efficiency of the system.

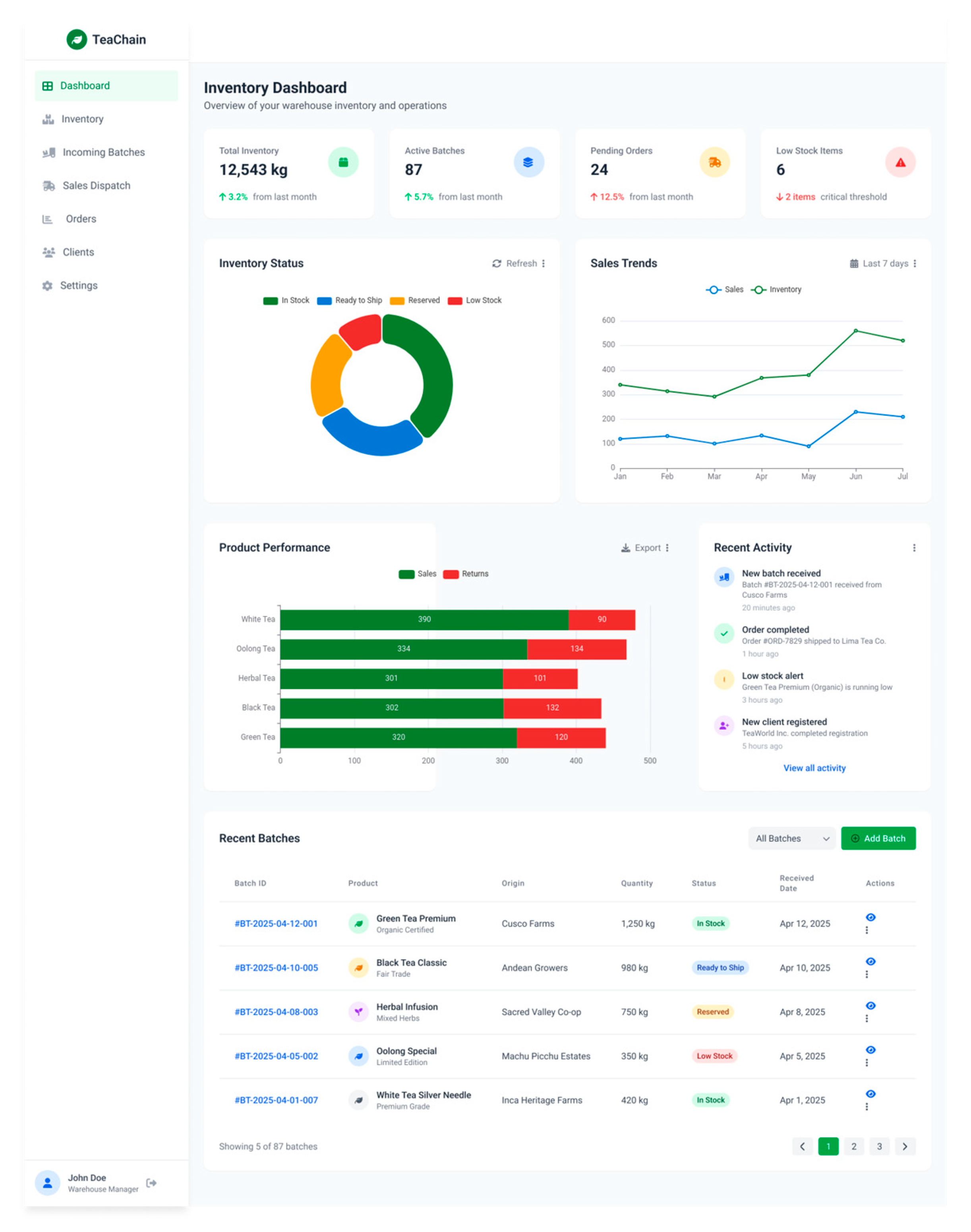

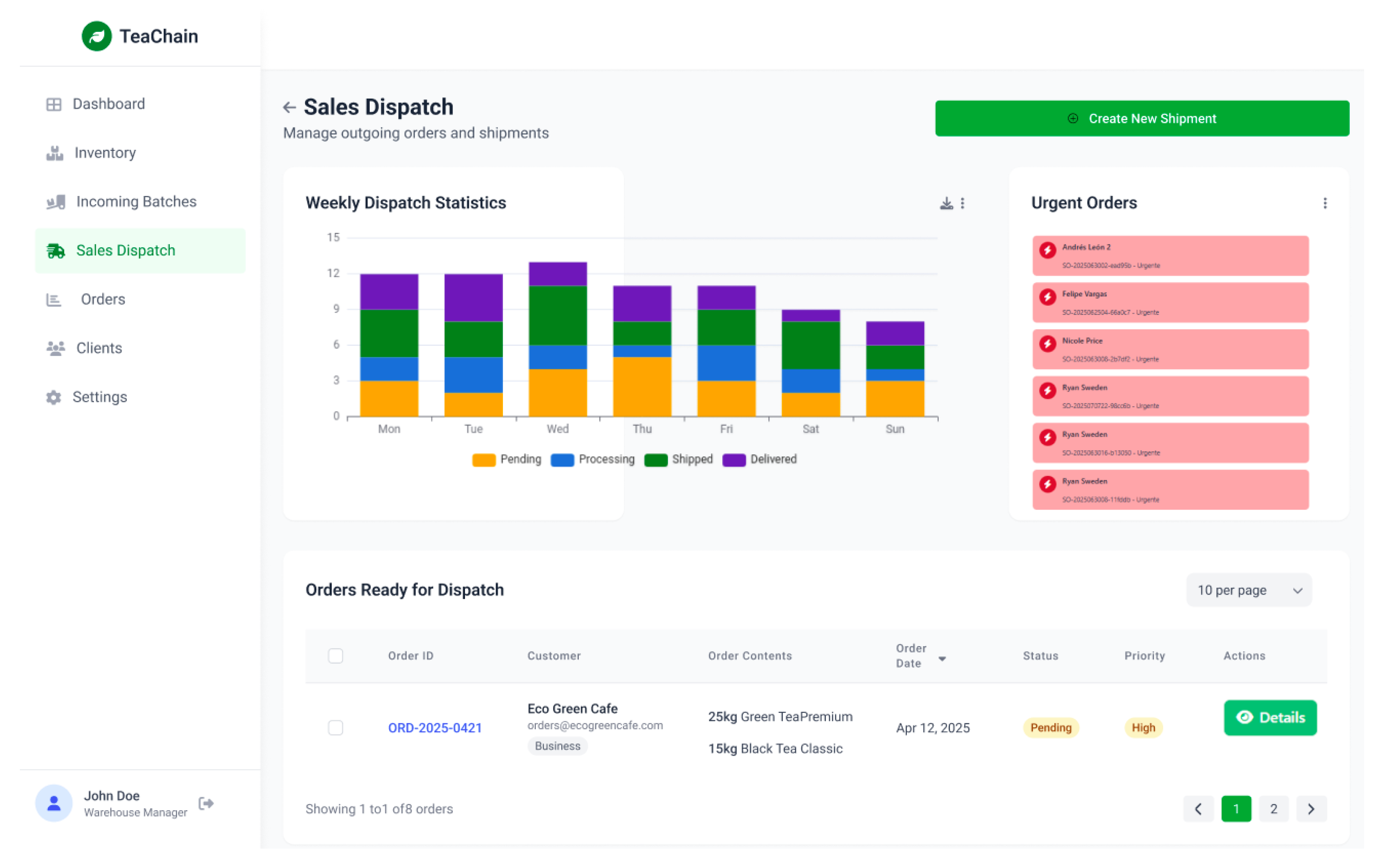

4.4. Interface Prototypes

During this phase, we developed navigation prototypes that represented the functional structure of the web application, based on the prioritized functional requirements, usability principles, and the needs identified in previous phases. The objective was to early validate user interaction with the essential modules of the system. For this purpose, we used the tool Figma, which allowed us to create and share interactive interfaces with the target users, thus facilitating rapid iterations and visual validations in real-time. The prototypes were high fidelity and allowed accurate evaluation of key aspects such as element layout, navigation between modules, and understanding of critical flows such as batch traceability, order management, and inventory monitoring.

Figure 3 represents the main dashboard, which provides a visual overview of inventory, product performance, sales trends, and recently recorded batches.

Figure 4 displays the sales dispatch panel with a visual overview of pending orders, processing times and rush orders.

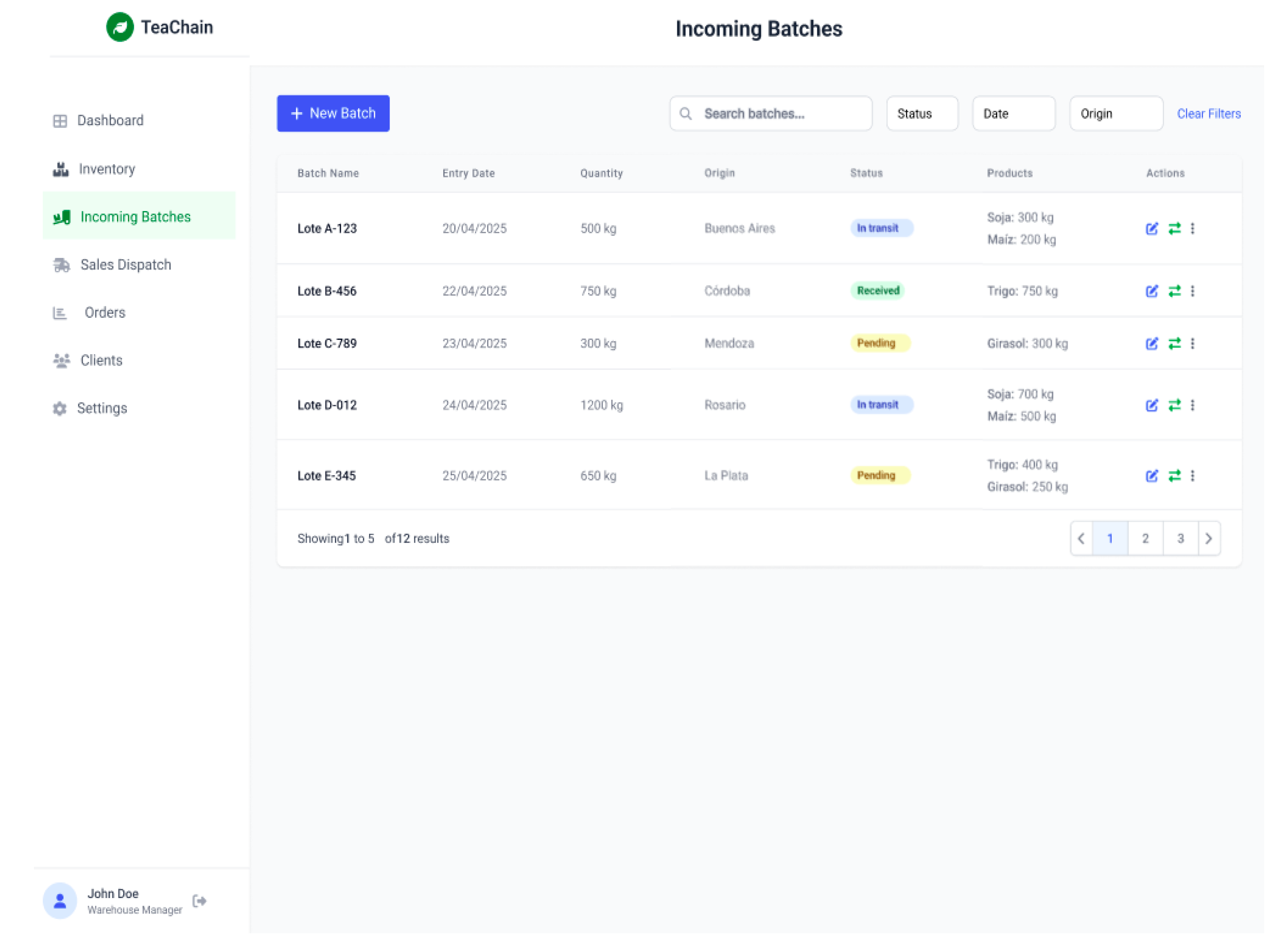

Figure 5 displays the table view of incoming lots, with details of their origin, quantity, and status

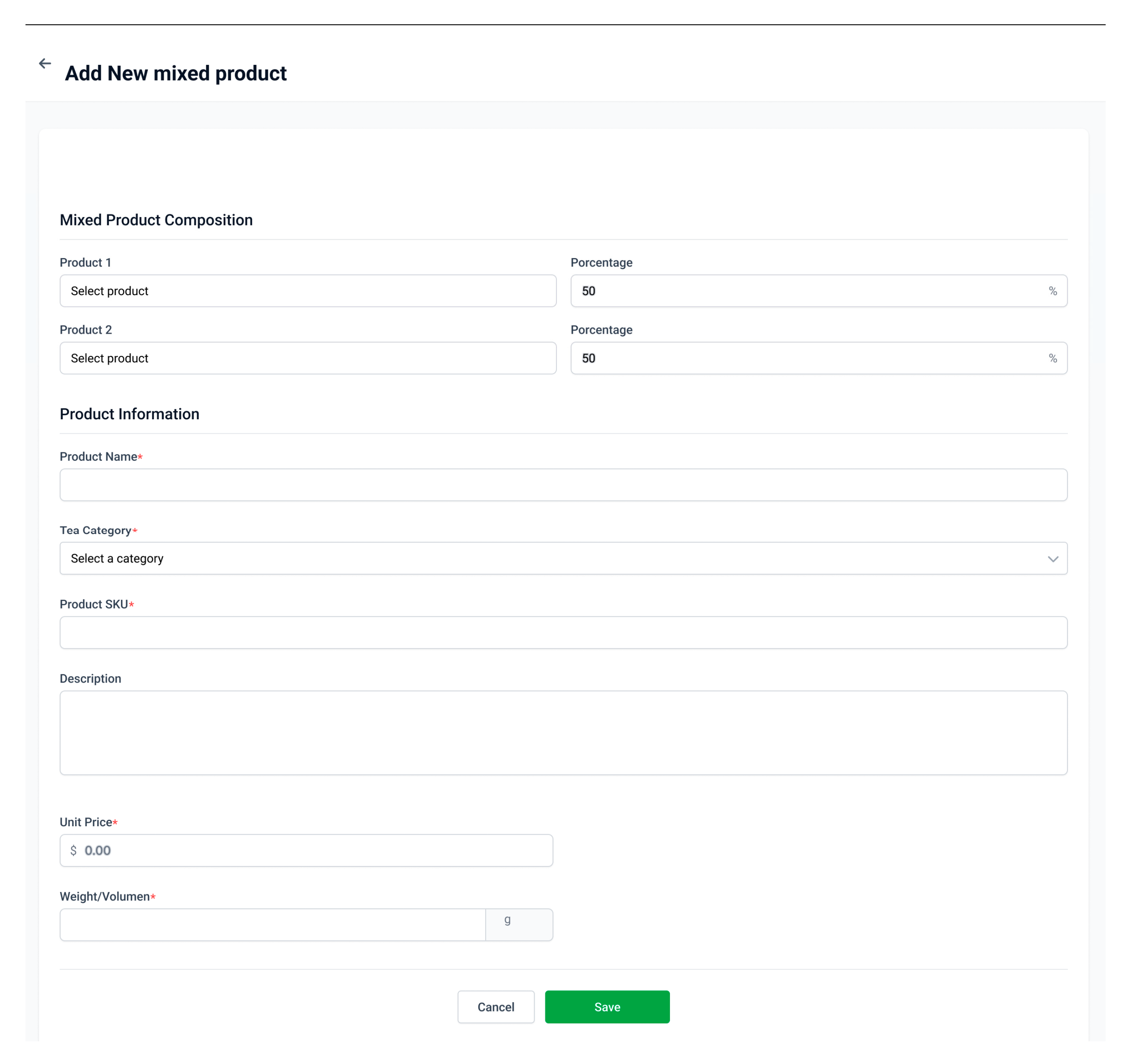

Figure 6 displays the registration form for a mixed product, allowing composition in percentages, as well as its commercial attributes.

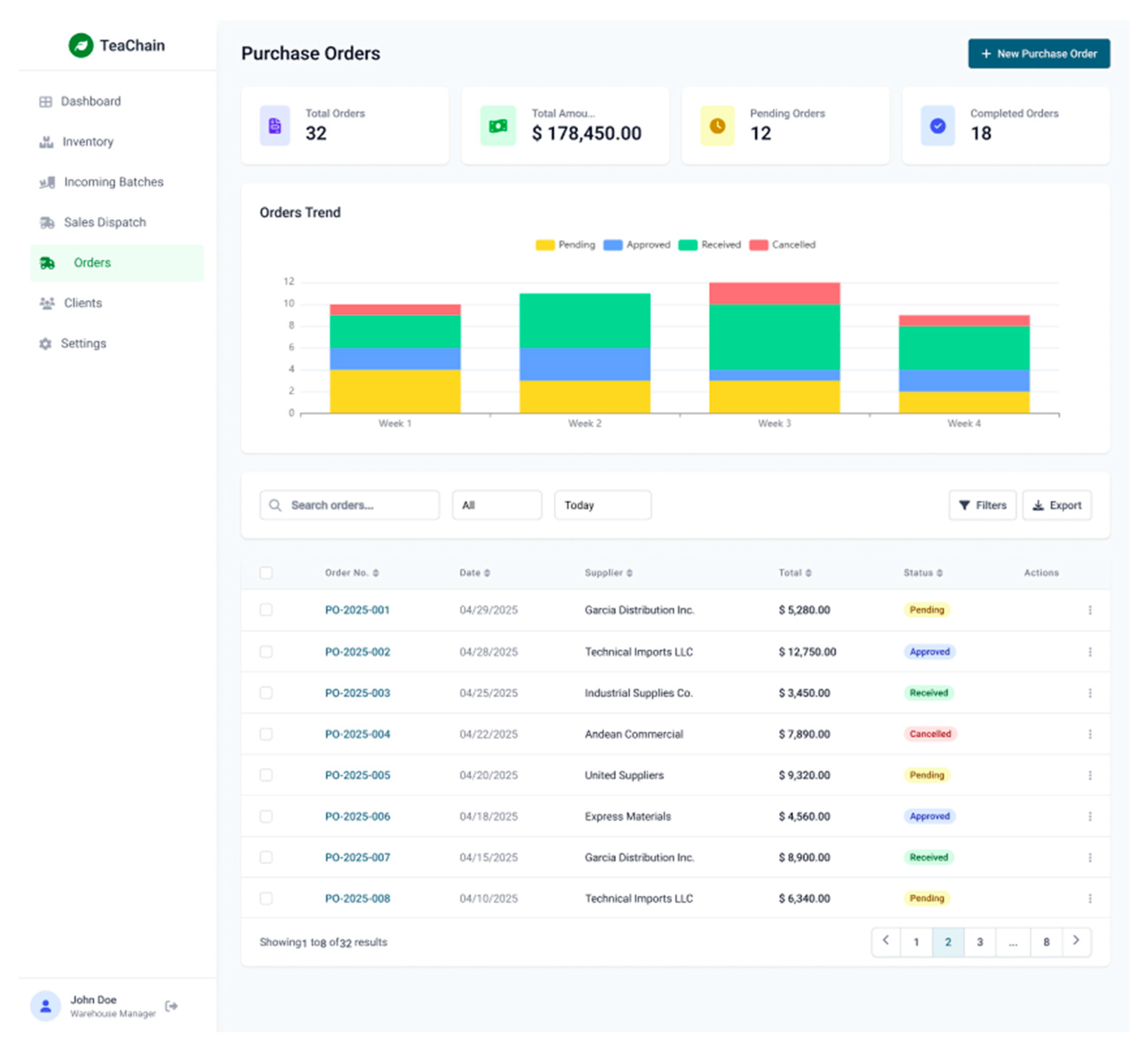

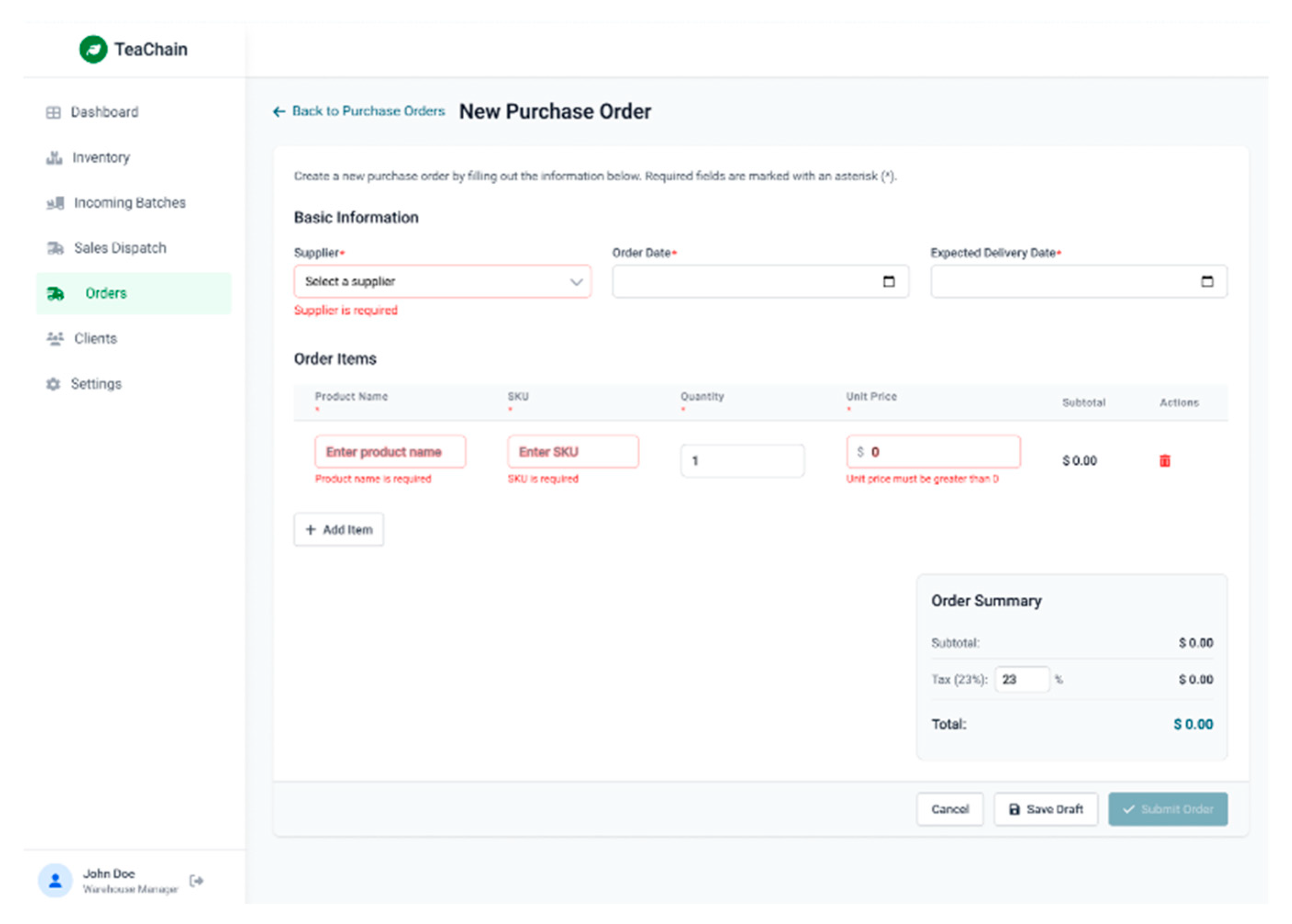

Figure 7 presents the purchase orders module, featuring a detailed list of supplier orders, a trend chart, and direct access to generate new purchase orders.

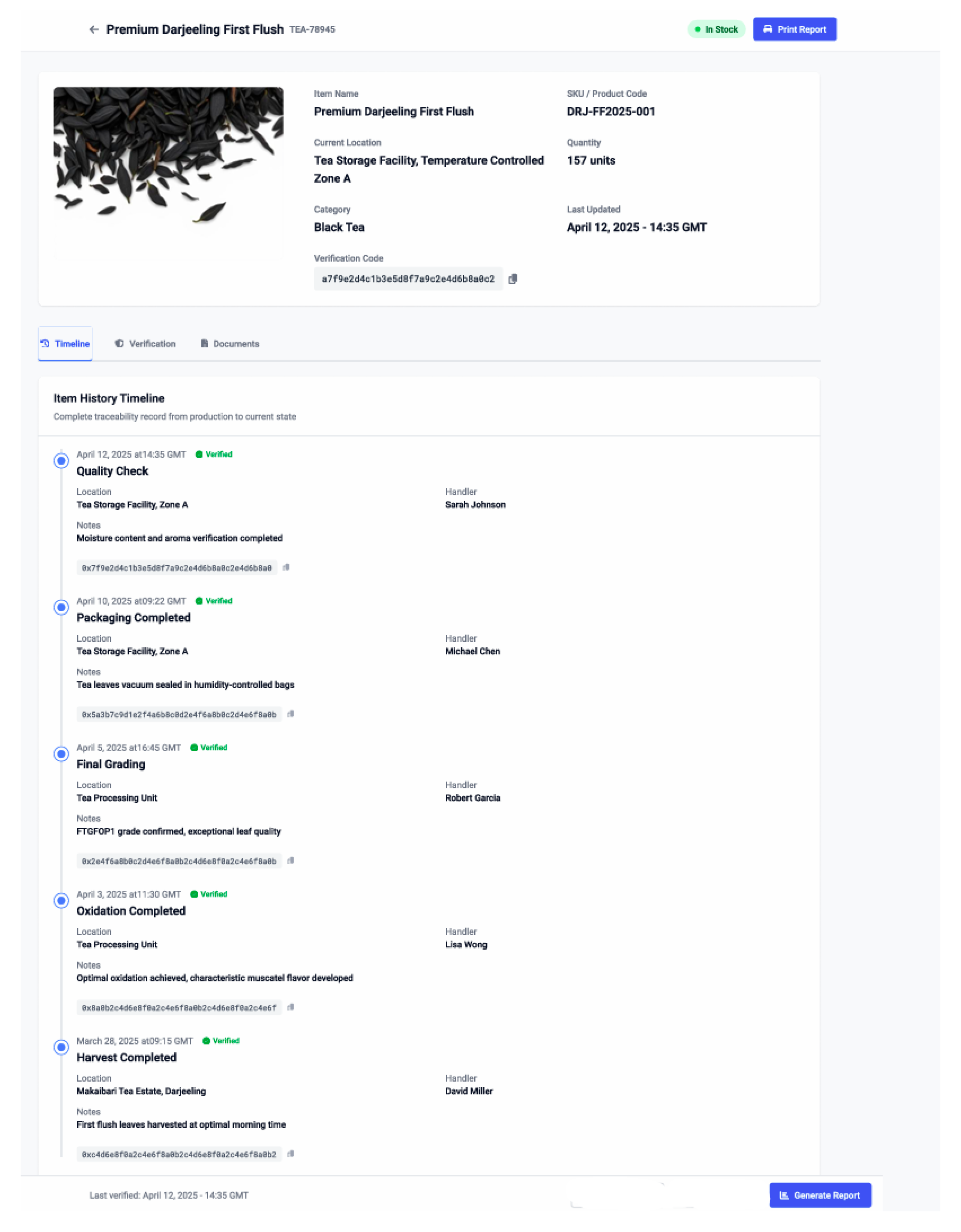

Figure 8 shows the traceability record of batch “TEA-78945” showing a timeline with key steps in its process flow.

Figure 9 presents the necessary form and fields to handle purchase orders for the inventory items.

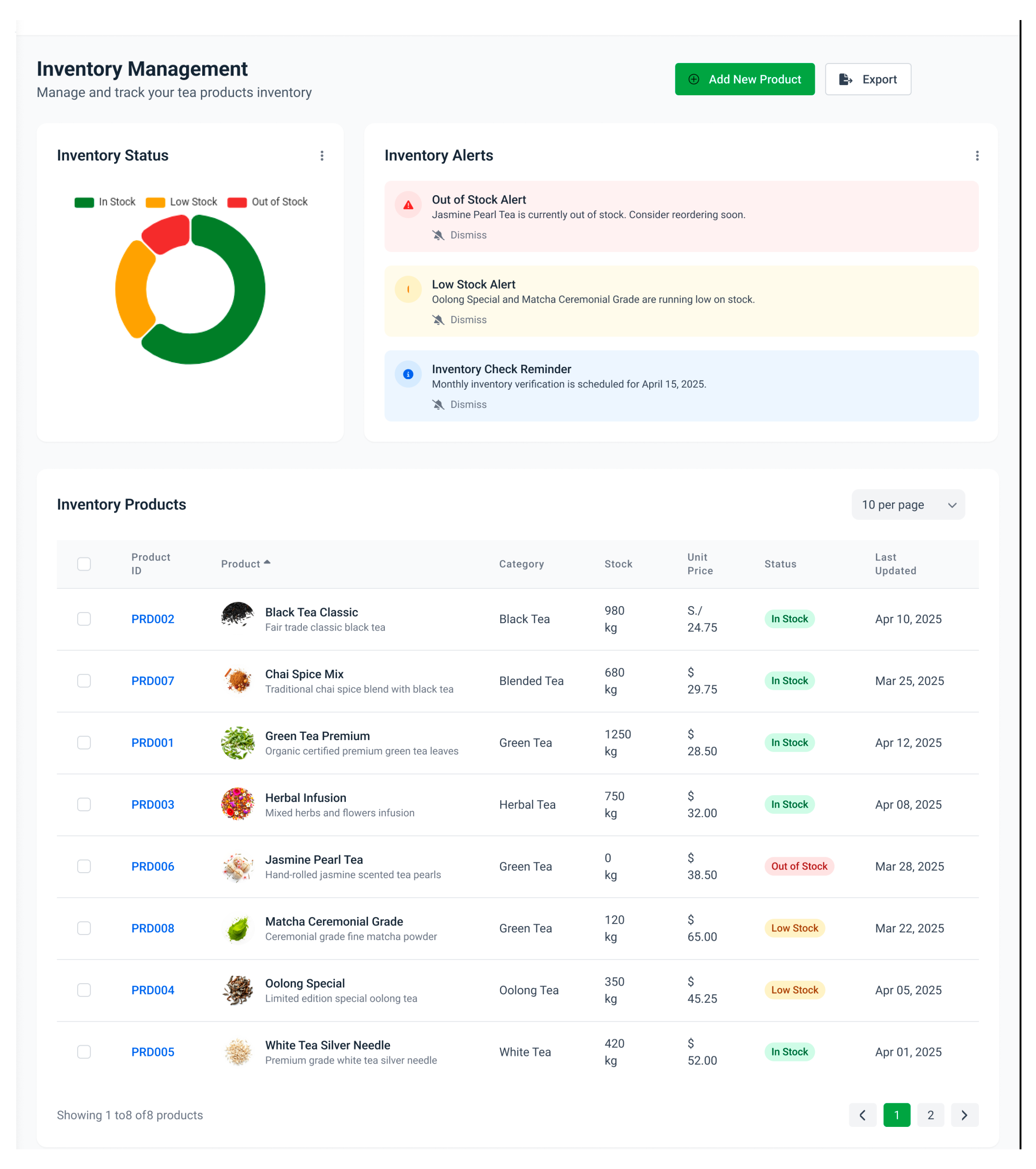

Figure 10 displays the inventory module, with overall metrics, visual alerts and a detailed list of inventory records in the system.

4.5. System Architecture

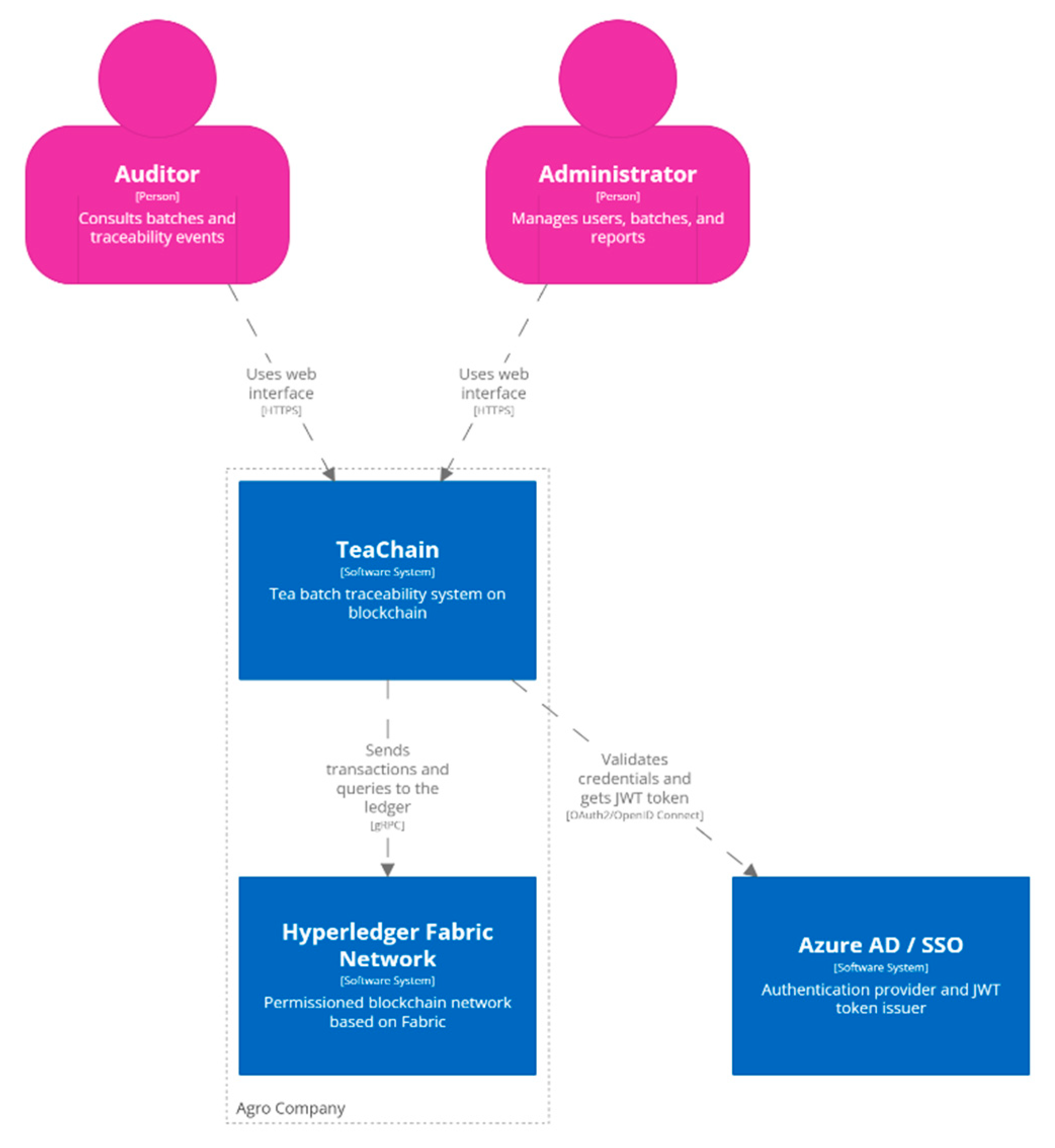

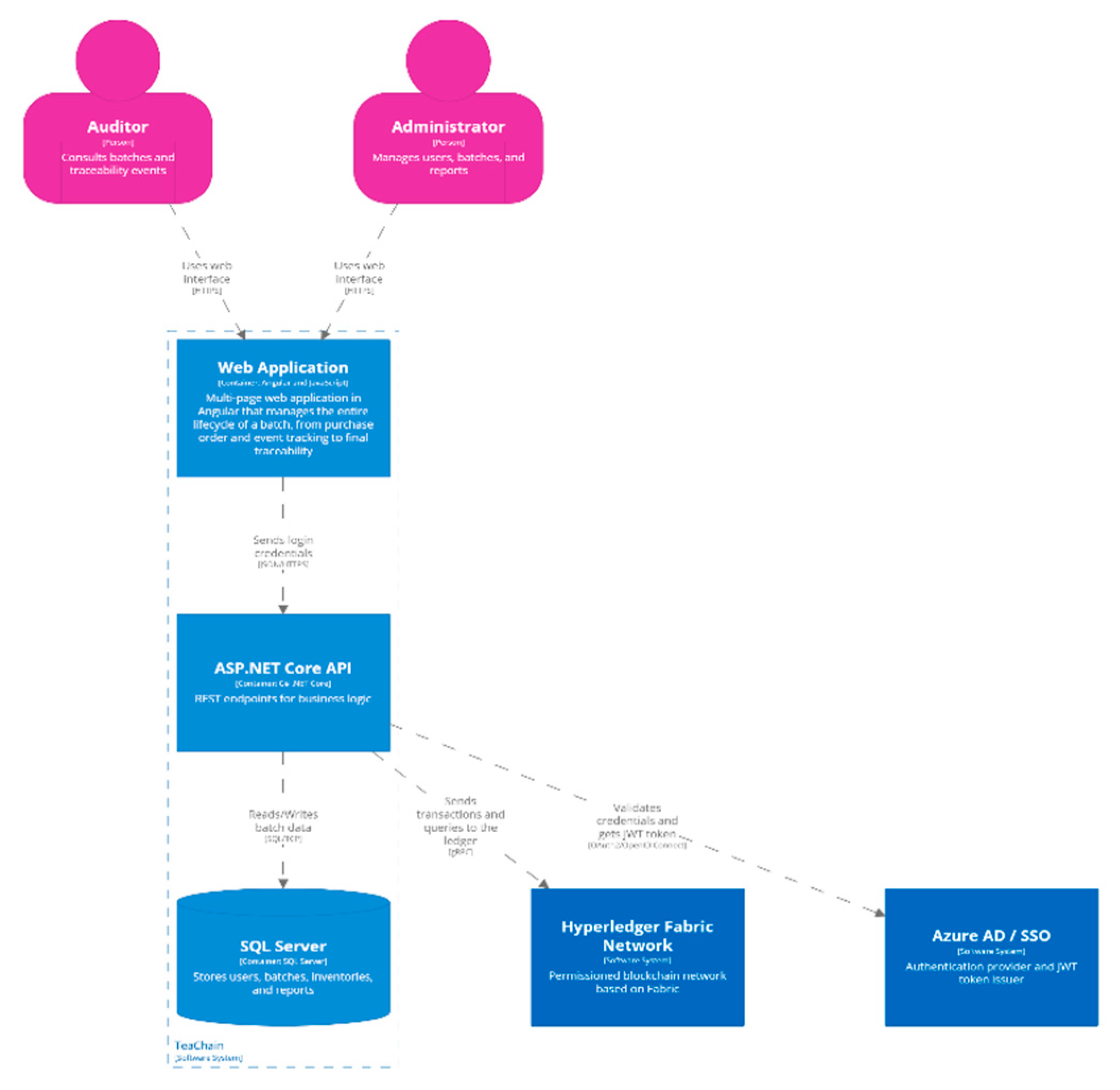

In the proposed system, the following key containers were identified:

Web Application: web application developed in Angular framework that acts as the primary interface for users.

ASP.NET Core API: REST API that implements the business logic of the system, handling operations such as batch registration, event validation and connection to the blockchain.

SQL Server: Relational database used to store operational system information such as users, inventory, events, and intermediate traceability.

Hyperledger Fabric Network: Permissioned blockchain network responsible for the immutable recording of critical events associated with batches, such as status changes, audits, and deliveries.

Azure Active Directory: External authentication service used to handle login and JWT token issuing.

Figure 11 presents the system context diagram, which shows the main interactions between users, our system, and external components such as the Blockchain network and the authentication provider.

Figure 12 shows the system’s container diagram, including the web application developed in Angular, the .NET Core API, the SQL Server database, the Hyperledger Fabric network, and Azure AD for authentication.

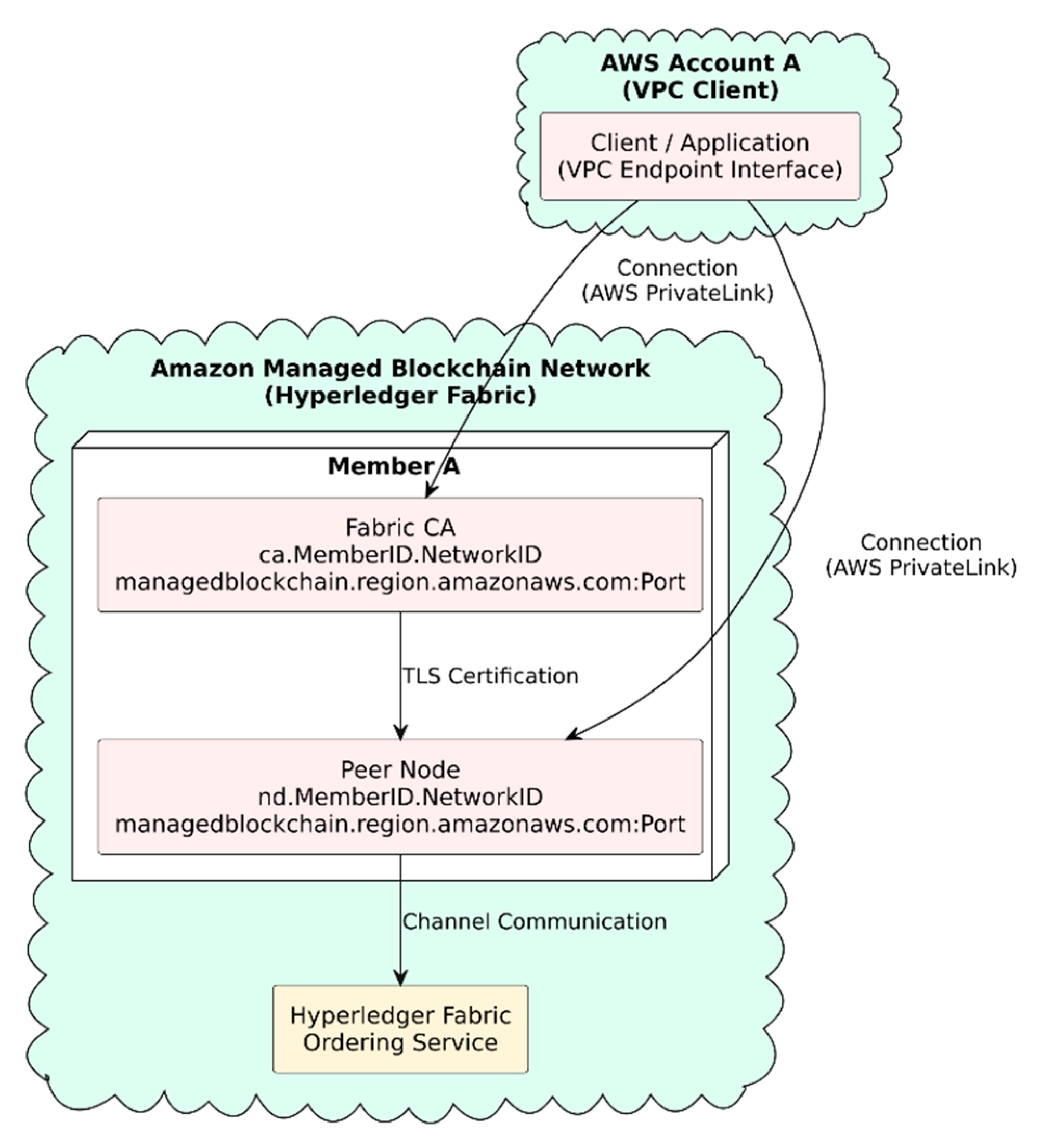

Figure 13 presents the network architecture used in this approach, based on Hyperledger Fabric deployed on Amazon Managed blockchain service. This implementation contemplates a single-member network (Member A), sufficient for small-scale scenarios such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The network is composed of a certificate authority (Fabric CA) and a peer node, both accessible through secure endpoints configured with TLS, and connected to Hyperledger Fabric's Ordering Service for block management. The access to this infrastructure is done from the API backend of the system, which is hosted by a separate client VPC (AWS Account A), through a secure connection provided by AWS PrivateLink. This configuration ensures encrypted, private and low-risk communication between the application and the blockchain network. This architecture ensures a reliable, scalable and easy-to-integrate environment for SMEs that require robust traceability without the need for a complex local infrastructure.

For theoretical and validation purposes of this approach, a private Hyperledger Fabric network deployed through the Amazon Managed Blockchain service has been used, due to its quick ease of configuration. This choice responds to practical criteria related to the testing environment and does not imply mandatory dependency on the provider.

The architecture is designed to be portable and adaptable to other Hyperledger Fabric-compatible environments, including on-premises deployments or other cloud platforms to manage peer nodes, certificate authorities and ordering services. This ensures that the solution can be adopted by small and medium-sized enterprises with different technical or budgetary capabilities, without limiting its implementation to a single vendor.

Network access is managed exclusively from the backend of the system, allowing security controls to be applied and critical traceability operations to be kept isolated. This structure offers a balance between operational simplicity, future scalability and compliance with agro-industrial security standards.

4.6. Testing

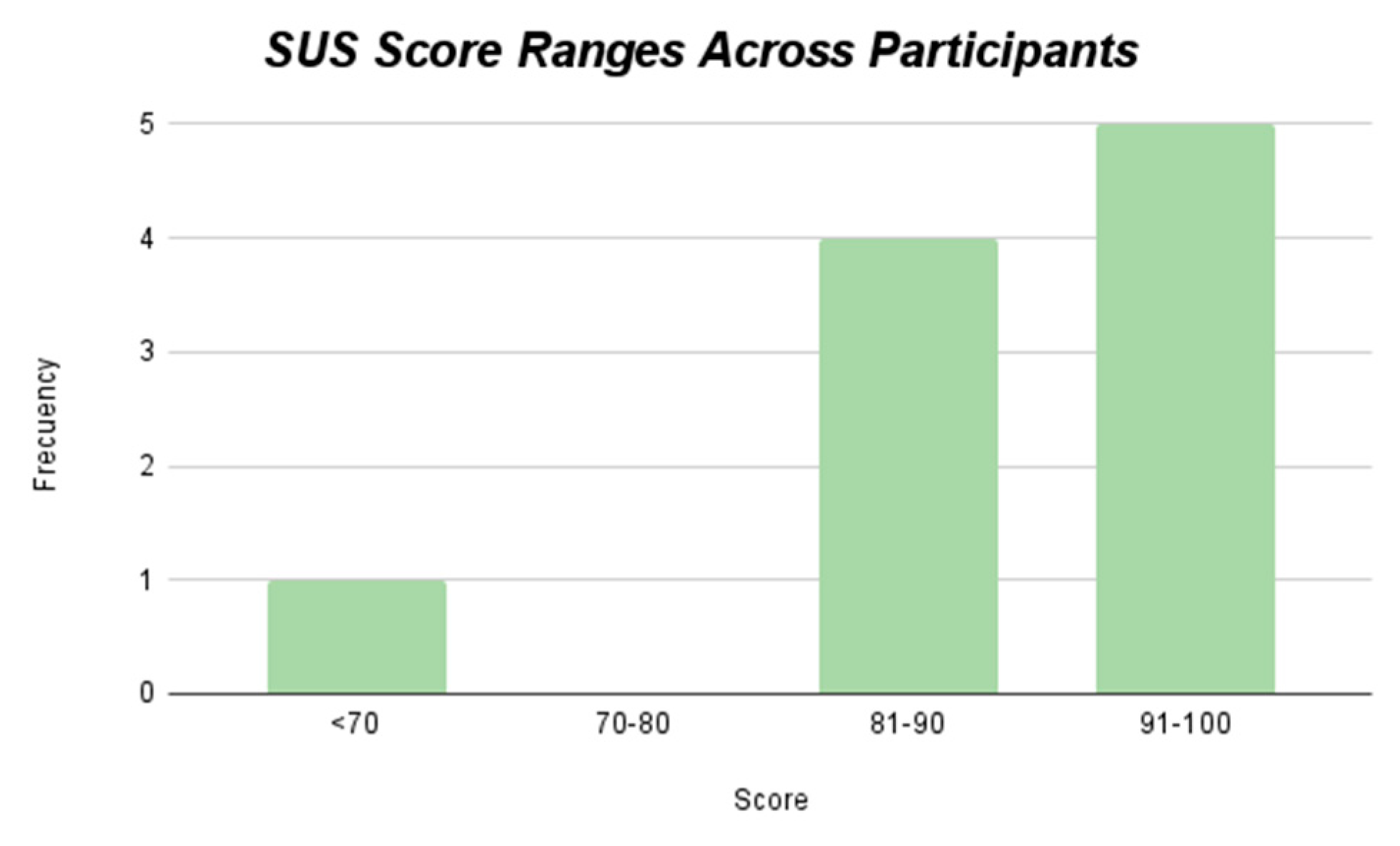

With the objective of measuring the usability of the prototype, we used the standardized SUS (System Usability Scale), which is widely used in user experience research due to its practicality and reliability.

4.6.1. Participant Selection

Profiles: Plant managers (7) and quality auditors (3)

Criteria: Minimum 6 months of experience in a similar role and basic computer literacy.

Sampling: intentional sampling in two pilot companies with prototypes in alpha phase.

4.6.2. Instrument

The System Usability Scale (SUS) consists of 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = "Strongly disagree"; 5 = "Strongly agree"). The questionnaire was self-administered by participants.

4.6.3. SUS Data Processing

For odd-numbered items: Score′= (response – 1)

For even-numbered items: Score′ = (5 – response)

Sum the 10 score′ for each participant → multiply by 2.5 → range 0-100.

Acceptability threshold: SUS ≥ 68

4.6.4. The Response Distribution Among the 10 Participants Is Presented Below:

Items 1, 5 and 10 (“easy to use”, “others would learn quickly”, “I would like to use it”) scored mostly 4-5.

Items 2, 4, 6, 8 and 9 (prior to learning, cumbersome, inconsistency, technical support, complexity) scored low (1-2) in 70-90% of cases.

Items 3 and 7 (safety, integrated functions) received 4 - 5 out of 90% of the participants.

4.6.5. Interpretation:

Figure 14 shows the distribution of SUS scores among the participants. The overall majority obtained scores in the 91-100 (n=5) and 81-90 (n=4) ranges, indicating a perception of excellent usability. Only one participant scored below 70 and no values between 70 and 80 were recorded.

5. Discussion

The validity and applicability of the SUS scale are based on its widespread use as a standardized, reliable tool for assessing the usability of digital systems in a variety of domains, including healthcare and new technologies [

27]. This research demonstrates that the SUS effectively identifies usability issues, allowing consistent interpretations of ease of use.

First, the result that we obtained in this study with an average score of 90 is above the minimum acceptable threshold, which confirms an excellent user experience. This supports the applicability of the scale and confirms that the designed prototype meets the expectations of the end users.

Secondly, when comparing this result with the studies reviewed in the related works section, it can be observed that projects such as IBM Food Trust and SmartBeanFutures focused mainly on traceability efficiency and trust among supply chain actors. However, these works did not present quantitative usability data such as the SUS scale. Therefore, this project contributes additional objective data that reinforces the quality of the proposed solution.

Therefore, unlike the other solutions, our contribution is focused on combining blockchain technology with smart contracts and a user-friendly interface for non-technical users.

Furthermore, this approach helps small and medium-sized agricultural enterprises improve transparency and adopt technology more easily.

Finally, the combination of blockchain and usability elevates the proposal of the prototype as a solid and distinctive tool for traceability in the agricultural supply chain.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to design and validate a web prototype based on blockchain technology to improve traceability and transparency in agricultural supply chains, aligning with the efficiency and security demands of the stakeholders involved. The results of the usability tests evidenced an average score of 90 on the SUS scale, which categorizes it as an excellent usability prototype. Four critical functionalities were also addressed, such as batch registration and monitoring, generation of immutable events, access management, and interface adapted to low-technical profiles through validation with end users.

A Smart contracts integration model is presented in Hyperledger Fabric that guarantees the immutability of records for detailed traceability of each stage of the plant management process within the supply chain, offering a reusable solution for SMEs in the agricultural sector. Among the limitations, it is implicitly assumed that all data entered by users is valid and reliable. The prototype is also limited in terms of accuracy, as it does not integrate IoT-scale sensors or automatic data capture devices. As a result, its reliability is constrained to ideal scenarios where data is entered manually, such as inventory weight or order tracking.

5. Future Works

The future development of this project will focus on deploying and evaluating the blockchain-based traceability system in a real agricultural warehouse environment. This next phase will aim to validate the prototype in real operating conditions, evaluating its performance, usability, and data consistency when used by real warehouse personnel. The application will not include IoT sensors but will rely on manual data entry to evaluate the adoption and impact of the system in typical small and medium-sized agricultural business scenarios. The results of this pilot application will serve as the basis for a broader implementation strategy and further enhancements.

References

- Tran, D.; Schouteten, J.J.; Gellynck, X.; De Steur, H. How Do Consumers Value Food Traceability?–A Meta-Analysis. Food Control 2024, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.B.; Torrisi, N.M.; Pantoni, R.P. Third Party Certification of Agri-Food Supply Chain Using Smart Contracts and Blockchain Tokens. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y. Research on the Cross-Chain Model of Rice Supply Chain Supervision Based on Parallel Blockchain and Smart Contracts. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subashini, B.; Hemavathi, D. Scalable Blockchain Technology for Tracking the Provenance of the Agri-Food. Computers, Materials and Continua 2023, 75, 3339–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, M.; Agnusdei, G.P.; Tadić, S.; Miglietta, P.P. Prioritization of E-Traceability Drivers in the Agri-Food Supply Chains. Agricultural and Food Economics 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugandh, U.; Nigam, S.; Khari, M.; Misra, S. An Approach for Risk Traceability Using Blockchain Technology for Tracking, Tracing, and Authenticating Food Products. Information (Switzerland) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, K.A.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Kim, B.-S. Fog-Computing-Based Cyber–Physical System for Secure Food Traceability through the Twofish Algorithm. Electronics (Switzerland) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagarakis, A.C.; Benos, L.; Kateris, D.; Tsotsolas, N.; Bochtis, D. Bridging the Gaps in Traceability Systems for Fresh Produce Supply Chains: Overview and Development of an Integrated Iot-based System. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, J.P.; Gaspar, P.D. Traceability in Food Supply Chains: SME Focused Traceability Framework for Chain-Wide Quality and Safety—Part 2. AIMS Agriculture and Food 2021, 6, 708–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Alam, T.; Al Sulaie, S.; Bouye, M.; Deebani, W.; Song, M. An Efficient IoT-Based Perspective View of Food Traceability Supply Chain Using Optimized Classifier Algorithm. Inf Process Manag 2023, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyan, S. A Blockchain-Based Inventory System with Lot Size-Dependent Lead Times and Uncertain Carbon Footprints. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Li, H. The Effect of Blockchain Technology on Supply Chain Sustainability Performances. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, C.C.; Organero, M.M.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, G.; Corrales, J.C. Smart Contracts as a Tool to Support the Challenges of Buying and Selling Coffee Futures Contracts in Colombia. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Rozuar, N.H.M.; Mergeresa, F. The Blockchain-Enabled Technology and Carbon Performance: Insights from Early Adopters. Technol Soc 2021, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, M.; Soregaroli, C.; Frizzi, G.L.; Stranieri, S. Impacts of Blockchain Technology in Agrifood: Exploring the Interplay between Transactions and Firms’ Strategic Resources. Supply Chain Management 2024, 29, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varavallo, G.; Caragnano, G.; Bertone, F.; Vernetti-Prot, L.; Terzo, O. Traceability Platform Based on Green Blockchain: An Application Case Study in Dairy Supply Chain. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, M.; Yu, H.; Wang, M.; Xu, D.; Sun, C. A Trusted Blockchain-Based Traceability System for Fruit and Vegetable Agricultural Products. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36282–36293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, M.U.A.; Khan, M.A.; Haseeb, A.; Albarakati, H.M.; Shabaz, M. A Secure Food Supply Chain Solution: Blockchain and IoT-Enabled Container to Enhance the Efficiency of Shipment for Strawberry Supply Chain. Front Sustain Food Syst 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yuen, C.W.; Koting, S.B.; Musa, S.N.B. Construction of a Blockchain Based Cold Chain Logistics Information Platform for Gannan Navel Oranges to Enhance Transparency and Efficiency. Front Sustain Food Syst 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikelsone, E.; Cīrule, I. Design Thinking Approach to Create Impact Assessment Tool: Cities2030 Case Study. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, U.; Regan, Á.; Hearne, D.; O’Meara, C. Empathising, Defining and Ideating with the Farming Community to Develop a Geotagged Photo App for Smart Devices: A Design Thinking Approach. Agric Syst 2021, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, Z.M.; Spiegal, S. Design Thinking for Responsible Agriculture 4.0 Innovations in Rangelands. Rangelands 2023, 45, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, R.; Schlögl, S.; Schweitzer, M. Technology-Supported Behavior Change—Applying Design Thinking to MHealth Application Development. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2024, 14, 584–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Ryu, S.J. Enhancing Sustainable Design Thinking Education Efficiency: A Comparative Study of Synchronous Online and Offline Classes. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, D.; Ruz, F.; Díaz-Arancibia, J.; Paz, F.; Osega, J.; Rojas, L.F. Innovating Statistics Education: The Design of a Novel App Using Design Thinking. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A “Quick and Dirty” Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation In Industry; CRC Press: London, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hyzy, M.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.; Bai, L.; Dix, A.; Leigh, S.; Hunt, S. System Usability Scale Benchmarking for Digital Health Apps: Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e37290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).