Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

0. Introduction

1. Organic Food Supply Chain Challenges

1.0.1. Trust Challenge

1.0.2. Traceability Challenge

1.0.3. Certification Cost and Efficiency Challenge

2. Blockchain Application in the Food Supply Chain

3. Blockchain for Organic Food Supply Chain

3.1. Enhancing Trust and Traceability

3.2. Certification Cost and Efficiency

4. Blockchain System for Organic Food Supply Chain

4.1. High-Level Overview

4.1.1. Key Objectives

- Enhanced Transparency: The system strives to provide stakeholders with unprecedented transparency into the entire supply chain, from farm to fork. By recording all transactions and data on an immutable blockchain ledger, participants can access real-time information about product origins, certifications, and movement.

- Improved Traceability: One of the primary objectives of the system is to enhance traceability throughout the supply chain. By utilizing IoT devices and smart contracts, stakeholders can accurately track the journey of organic food products, ensuring compliance with organic standards and regulations.

- Streamlined Certification: The system aims to streamline the certification process for organic products, reducing administrative burdens and costs associated with traditional certification methods. Through automated verification processes and smart contracts, farmers and processors can obtain digital certification tokens, simplifying the certification process.

4.1.2. Potential Benefits for Stakeholders

- Farmers and Processors: The blockchain system offers farmers and processors greater visibility and control over their products’ certification status and supply chain movement. By reducing certification costs and administrative complexities, stakeholders can focus on sustainable production practices and market competitiveness.

- Distributors and Retailers: Distributors and retailers benefit from increased trust and credibility in their product offerings. With access to transparent and verifiable information about product origins and certifications, they can assure consumers of the quality and authenticity of organic food products, thereby enhancing brand reputation and customer loyalty.

- Consumers: Consumers stand to gain the most from the blockchain system, as it empowers them with unprecedented transparency and trust in the food they purchase. By scanning product QR codes and accessing detailed information about product origins, certifications, and supply chain journeys, consumers can make informed choices aligned with their values and preferences.

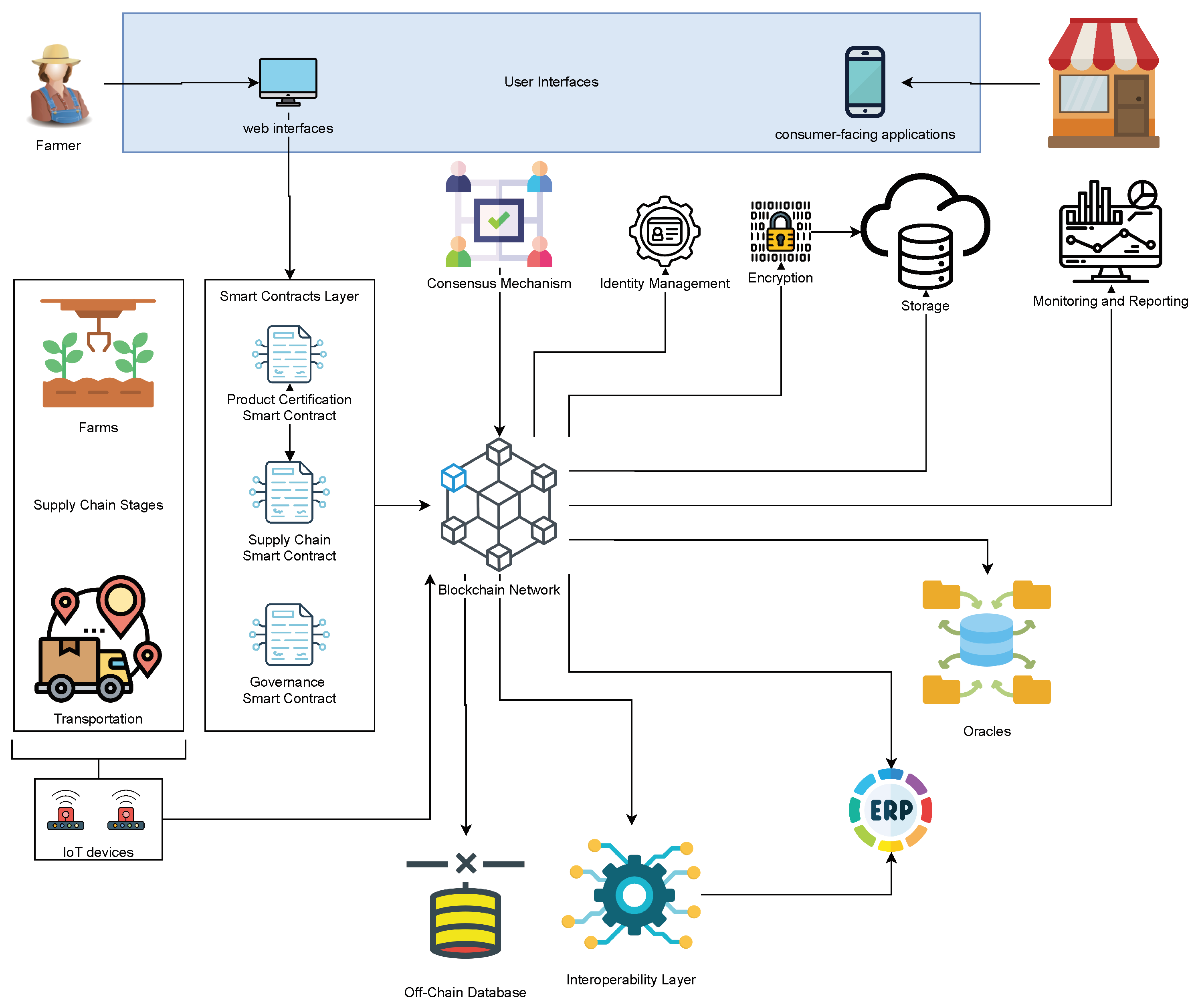

4.2. System Architecture Components

4.2.1. User Interfaces (Web Interface)

4.2.2. Smart Contracts Layer

Product Certification Smart Contract

Supply Chain Smart Contract

4.2.3. Consensus Mechanism

4.2.4. Blockchain Network

4.2.5. Identity Management

4.2.6. Data Encryption

4.2.7. Interoperability Layer

4.2.8. Internet of Things (IoT) Integration

4.2.9. Data Storage

4.2.10. Off-Chain Database

4.2.11. Oracles

4.2.12. Governance and Compliance

4.2.13. Monitoring and Reporting

4.2.14. User Authentication

4.2.15. Integration with External Systems

4.2.16. Consumer-Facing Applications

4.2.17. Audit Trail

4.2.18. Scalability and Performance Optimization

4.2.19. Legal and Regulatory Compliance

4.3. Limitations and Challenges

4.4. Use Case: Certified Organic Tofu in the Organic Food Supply Chain

4.4.1. Product Certification

Initiation

Smart Contract Execution

4.4.2. Supply Chain Movement

Blockchain Transaction

Node Communication

4.4.3. IoT Data Collection

Sensors and Devices

Data Recording

4.4.4. Retailer Integration

ERP System Integration

4.4.5. Consumer Verification

Mobile App Interaction

Blockchain Query

4.4.6. Governance and Compliance

Decision-Making

Voting

Enforcement

4.4.7. Traceability and Audit

Immutable Ledger

4.4.8. Legal Compliance

Smart Contracts for Compliance

4.5. Discussion of Future Research

4.5.1. Scalability

4.5.2. Security

4.5.3. Real-World Implementation Challenges

4.5.4. Sustainability

4.5.5. Governance and Standardization

5. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Application Programming Interfaces | APIs |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GMO | Genetically Modified Organism |

| IFAD | International Fund for Agricultural Development |

| IFOAM | International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| NFC | Near Field Communication |

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identification |

| WEF | World Economic Forum |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture; 2019.

- Research, P. Organic Food Market (By Product: Fruits and vegetables, Dairy products, Meat, fish and poultry, Frozen foods, Others; By Distribution Channel: Online, Offline) - Global Industry Analysis, Size, Share, Growth, Trends, Regional Outlook, and Forecast 2023-2032. Report, 2023. Report Code: 1843, Category: Food and Beverages, Number of Pages: 150+, Format: PDF/PPT/Excel, Historical Year: 2021-2022, Base Year: 2023, Estimated Years: 2024-2033.

- Fotopoulos, C.; Krystallis, A. Purchasing motives and profile of the Greek organic consumer: a countrywide survey. British Food Journal 2002, 104, 730–765. [CrossRef]

- Larue, B.; West, G.E.; Gendron, C.; Lambert, R. Consumer response to functional foods produced by conventional, organic, or genetic manipulation. Agribusiness 2004, 20, 155–166. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Magnusson, M.; Sjödén, P.O. Determinants of Consumer Behavior Related to Organic Foods. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 2005, 34, 352 – 359. [CrossRef]

- Langelaan, H.; Pereira da Silva, F.; Thoden van Velzen, U.; Broeze, J.; Matser, A.; Vollebregt, M.; Schroën, K. Technology options for feeding 10 billion people Options for sustainable food processing. STOA Research Administrator: Brussels, Belgium 2013, 1.

- Schleenbecker, R.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perception of organic product characteristics. A review. Appetite 2013, 71, 420–429. [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, U. Sustainable supply chain management in agri-food chains: a competitive factor for food exporters. Sustainability Challenges in the agrofood sector 2017, pp. 150–174.

- Bodnaruk, K. Pesticide residues in food 2018 - Report 2018 - Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues.

- van Hilten, M.; Ongena, G.; Ravesteijn, P. Blockchain for organic food traceability: Case studies on drivers and challenges. Frontiers in Blockchain 2020, 3, 43. [CrossRef]

- (EFSA), E.F.S.A. The 2017 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA Journal, 17, e05743. [CrossRef]

- Bitcoin Magazine. Innovation Percolates When Coffee Meets the Blockchain. Nasdaq 2017.

- Atzori, M. Blockchain technology and decentralized governance: Is the state still necessary? Available at SSRN 2709713 2015. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, S. Blockchain beyond bitcoin. Communications of the ACM 2016, 59, 15–17. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhu, D. Fraud detections for online businesses: a perspective from blockchain technology. Financial Innovation 2016, 2, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kraft, D. Difficulty control for blockchain-based consensus systems. Peer-to-peer Networking and Applications 2016, 9, 397–413. [CrossRef]

- Swan, M. Blockchain: Blueprint for a new economy; " O’Reilly Media, Inc.", 2015.

- Yu, Y.; He, Y. Information disclosure decisions in an organic food supply chain under competition. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 292, 125976. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Fourth Industrial Revolution for the Earth Series: Building Block(chain)s for a Better Planet; World Economic Forum, 2018. In collaboration with PwC and Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

- Bauer, H.H.; Heinrich, D.; Schäfer, D.B. The effects of organic labels on global, local, and private brands: More hype than substance? Journal of Business Research 2013, 66, 1035–1043. [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J.; Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Parras-Rosa, M. Organic as a heuristic cue: What Spanish consumers mean by organic foods. Psychology & Marketing 2014, 31, 349–359.

- Popa, M.E.; Mitelut, A.C.; Popa, E.E.; Stan, A.; Popa, V.I. Organic foods contribution to nutritional quality and value. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 84, 15–18.

- Sazvar, Z.; Rahmani, M.; Govindan, K. A sustainable supply chain for organic, conventional agro-food products: The role of demand substitution, climate change and public health. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 194, 564–583. [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H.N.; Ophuis, P.A.O. Health-related determinants of organic food consumption in the Netherlands. Food quality and Preference 1998, 9, 119–133. [CrossRef]

- Marotta, G.; Simeone, M.; Nazzaro, C. Product reformulation in the food system to improve food safety. Evaluation of policy interventions. Appetite 2014, 74, 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Dabbert, S.; Lippert, C.; Zorn, A. Introduction to the special section on organic certification systems: Policy issues and research topics. Food Policy 2014, 49, 425–428. [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, M.C.; Armbruster, W.; Young, R. Big data’s potential to improve food supply chain environmental sustainability and food safety. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2016, 19, 155–171.

- Barbosa, R.M.; de Paula, E.S.; Paulelli, A.C.; Moore, A.F.; Souza, J.M.O.; Batista, B.L.; Campiglia, A.D.; Barbosa Jr, F. Recognition of organic rice samples based on trace elements and support vector machines. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2016, 45, 95–100. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, M.D.; Barbosa, R. Methods of authentication of food grown in organic and conventional systems using chemometrics and data mining algorithms: A review. Food Analytical Methods 2019, 12, 887–901. [CrossRef]

- Pollard, S.; Namazi, H.; Khaksar, R. Big data applications in food safety and quality 2019.

- You taste what you see: Do organic labels bias taste perceptions? Food Quality and Preference 2013, 29, 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, B.; Duff, B.R.; Wang, Z.; White, T.B. Putting the organic label in context: Examining the interactions between the organic label, product type, and retail outlet. Food Quality and Preference 2016, 49, 140–150. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, H.R.; Browne, A.W.; Harris, P.; Cadoret, K. Organic certification and the UK market: organic imports from developing countries. Food policy 2002, 27, 301–318. [CrossRef]

- Veldstra, M.D.; Alexander, C.E.; Marshall, M.I. To certify or not to certify? Separating the organic production and certification decisions. Food Policy 2014, 49, 429–436. [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, K.; Tourte, L. Organic agricultural production in the United States: Debates and directions. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 1998, 80, 1119–1124. [CrossRef]

- Snider, A.; Gutiérrez, I.; Sibelet, N.; Faure, G. Small farmer cooperatives and voluntary coffee certifications: Rewarding progressive farmers of engendering widespread change in Costa Rica? Food Policy 2017, 69, 231–242. [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.; Martínez, L. Local alternatives to private agricultural certification in Ecuador: Broadening access to ‘new markets’? Journal of Rural Studies 2016, 45, 292–302. [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P.; Poulton, C.; Wiggins, S.; Dorward, A. The future of small farms: trajectories and policy priorities. World development 2010, 38, 1349–1361. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. The normative impact of consumer price expectations for multiple brands on consumer purchase behavior. Marketing Science 1992, 11, 266–286. [CrossRef]

- Baltas, G. A model for multiple brand choice. European Journal of Operational Research 2004, 154, 144–149. [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Laroche, M.; Zhu, H. The effects of multiple-ads and multiple-brands on consumer attitude and purchase behavior. Journal of consumer marketing 2007, 24, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Optimal pricing policies for differentiated brands under different supply chain power structures. European Journal of Operational Research 2017, 259, 437–451. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, A.; Van Klinken, R.; Schrobback, P.; Muller, J. Consumer Trust in Food and the Food System: A Critical Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2490. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W.; McGoldrick, P.J. Consumer’s risk-reduction strategies: a review and synthesis. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 1996, 6, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W. Consumer perceived risk: conceptualisations and models. European Journal of marketing 1999, 33, 163–195. [CrossRef]

- Boksberger, P.E.; Melsen, L. Perceived value: a critical examination of definitions, concepts and measures for the service industry. Journal of services marketing 2011, 25, 229–240. [CrossRef]

- Uncertainty risks and strategic reaction of restaurant firms amid COVID-19: Evidence from China. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2021, 92, 102752. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kang, J. Reducing perceived health risk to attract hotel customers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Focused on technology innovation for social distancing and cleanliness. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2020, 91, 102664. [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Pontier, S.; Schaer, B. Orientations de la confiance et choix du circuit de distribution: le cas des produits biologiques. Proceedings of the 10th FMA International Congres, St. Malo, France, 2004.

- The development and validation of a toolkit to measure consumer trust in food. Food Control 2020, 110, 106988. [CrossRef]

- Rampl, L.V.; Eberhardt, T.; Schütte, R.; Kenning, P. Consumer trust in food retailers: conceptual framework and empirical evidence. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2012, 40, 254–272.

- Aung, M.M.; Chang, Y.S. Traceability in a food supply chain: Safety and quality perspectives. Food control 2014, 39, 172–184. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, A.R. The third party certification system for organic products. Network Intelligence Studies 2015, 3, 145–151.

- Charlebois, S.; Sterling, B.; Haratifar, S.; Naing, S.K. Comparison of global food traceability regulations and requirements. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety 2014, 13, 1104–1123. [CrossRef]

- Mainetti, L.; Patrono, L.; Stefanizzi, M.L.; Vergallo, R. An innovative and low-cost gapless traceability system of fresh vegetable products using RF technologies and EPCglobal standard. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2013, 98, 146–157. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; He, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, L. Certify or not? An analysis of organic food supply chain with competing suppliers. Annals of Operations Research 2019, pp. 1–31.

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Decentralized business review 2008.

- Yang, R.; Wakefield, R.; Lyu, S.; Jayasuriya, S.; Han, F.; Yi, X.; Yang, X.; Amarasinghe, G.; Chen, S. Public and private blockchain in construction business process and information integration. Automation in construction 2020, 118, 103276. [CrossRef]

- Helliar, C.V.; Crawford, L.; Rocca, L.; Teodori, C.; Veneziani, M. Permissionless and permissioned blockchain diffusion. International Journal of Information Management 2020, 54, 102136. [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, C.; Yang, W. Blockchain-based trusted data sharing among trusted stakeholders in IoT. Software: practice and experience 2021, 51, 2051–2064. [CrossRef]

- Monkkonen, P. Are civil-law notaries rent-seeking monopolists or essential market intermediaries? Endogenous development of a property rights institution in Mexico. In An Endogenous Theory of Property Rights; Routledge, 2018; pp. 104–128.

- Rejeb, A.; Keogh, J.G.; Zailani, S.; Treiblmaier, H.; Rejeb, K. Blockchain Technology in the Food Industry: A Review of Potentials, Challenges and Future Research Directions. Logistics 2020, 4. [CrossRef]

- Dujak, D.; Sajter, D. Blockchain applications in supply chain. SMART supply network 2019, pp. 21–46.

- Tripoli, M.; Schmidhuber, J. Emerging Opportunities for the Application of Blockchain in the Agri-food Industry 2018.

- Andronie, M.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Iatagan, M.; Hurloiu, I.; Dijmărescu, I. Sustainable cyber-physical production systems in big data-driven smart urban economy: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 751. [CrossRef]

- Tribis, Y. Abdelali El Bouchti, and Houssine Bouayad.". Supply Chain Management Based on Blockchain: A Systematic Mapping Study." Edited by B. Abou El Majd and H. El Ghazi. MATEC Web of Conferences, 2018, Vol. 200, p. 00020.

- Wolfert, S.; Bogaardt, M.; Splinter, G. Towards Data-Driven Agri-Food Business, 2018.

- Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Lopez, C.; Lu, H.; Elgueta, S.; Chen, H.; Boshkoska, B.M. Blockchain technology in agri-food value chain management: A synthesis of applications, challenges and future research directions. Computers in industry 2019, 109, 83–99. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.; Jõudu, I. Emerging issues and challenges in agri-food supply chain. Sustainable food supply chains 2019, pp. 23–37.

- Dos Santos, R.B.; Torrisi, N.M.; Pantoni, R.P. Third party certification of agri-food supply chain using smart contracts and blockchain tokens. Sensors 2021, 21, 5307. [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Fonts, A.; Prenafeta-Boldύ, F.X. The rise of blockchain technology in agriculture and food supply chains. Trends in food science & technology 2019, 91, 640–652.

- Li, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Gharehgozli, A. Blockchain in food supply chains: A literature review and synthesis analysis of platforms, benefits and challenges. International Journal of Production Research 2023, 61, 3527–3546. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishna Reddy, G.; Ratna Kumar, K. Quality improvement in organic food supply chain using blockchain technology. Innovative Product Design and Intelligent Manufacturing Systems: Select Proceedings of ICIPDIMS 2019. Springer, 2020, pp. 887–896.

- Tian, F. An agri-food supply chain traceability system for China based on RFID & blockchain technology. 2016 13th international conference on service systems and service management (ICSSSM). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–6.

- Jeppsson, A.; Olsson, O. Blockchains as a solution for traceability and transparency 2017.

- Sharples, M.; Domingue, J. The blockchain and kudos: A distributed system for educational record, reputation and reward. Adaptive and Adaptable Learning: 11th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, EC-TEL 2016, Lyon, France, September 13-16, 2016, Proceedings 11. Springer, 2016, pp. 490–496.

- Abeyratne, S.A.; Monfared, R.P. Blockchain ready manufacturing supply chain using distributed ledger. International journal of research in engineering and technology 2016, 5, 1–10.

- Kshetri, N. 1 Blockchain’s roles in meeting key supply chain management objectives. International Journal of information management 2018, 39, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, H.; Alazab, M.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Han, Z.; Su, C. Blockchain-based reliable and efficient certificateless signature for IIoT devices. IEEE transactions on industrial informatics 2021, 18, 7059–7067. [CrossRef]

- White, B. Rural youth, today and tomorrow. In Rural Development Reports; IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development: Rome, Italy, 2019.

- Wang, Z.J.; Chen, Z.S.; Xiao, L.; Su, Q.; Govindan, K.; Skibniewski, M.J. Blockchain adoption in sustainable supply chains for Industry 5.0: A multistakeholder perspective. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, D.A.; Liu, J.K.; Suwarsono, D.A.; Zhang, P. A new blockchain-based value-added tax system. Provable Security: 11th International Conference, ProvSec 2017, Xi’an, China, October 23-25, 2017, Proceedings 11. Springer, 2017, pp. 471–486.

- Fanning, K.; Centers, D.P. Blockchain and its coming impact on financial services. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 2016, 27, 53–57.

- Making sense of blockchain technology: How will it transform supply chains? International Journal of Production Economics 2019, 211, 221–236. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.; Streew, e.a. Supply Chain Finance and Blockchain Technology: The Case of Reverse Securitisation; Softcover Springer Buiefs, 2018.

- Iansiti, M.; Lakhani, K.R.; others. The truth about blockchain. Harvard business review 2017, 95, 118–127.

- Kshetri, N. Blockchain’s Roles in Strengthening Cybersecurity and Protecting Privacy. Telecommunications Policy 2017, 41, 1027–1038. [CrossRef]

| Certification Standard | Allowed Inputs | Labeling Requirements | Inspection Procedures |

|---|---|---|---|

| USDA Organic | Organic inputs only, no synthetic pesticides or GMOs | USDA Organic seal, ingredient list with organic content | Annual on-site inspections, periodic residue testing |

| EU Organic | Organic inputs only, restricted use of synthetic pesticides | EU Organic logo, indication of organic status | Annual inspections, random sampling and testing |

| IFOAM Organic | Organic inputs only, no GMOs, biodiversity conservation | IFOAM Organic seal, clear labeling of organic ingredients | Regular inspections, risk-based audits |

| Other Regional Standards | Varies by region, typically similar to USDA or EU standards | Varies by region | Varies by region, but often include on-site inspections and residue testing |

| Benefit | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Improved Traceability | Blockchain technology enables the recording of every transaction in the supply chain, providing a transparent and immutable record of product movement from farm to fork. This enhances traceability by allowing stakeholders to track the origin, journey, and handling of organic products, reducing the risk of contamination and facilitating rapid recalls if necessary. |

| Enhanced Trust | The decentralized and tamper-proof nature of blockchain technology instills trust among stakeholders by ensuring the integrity and transparency of data. With every transaction recorded on the blockchain, consumers, producers, retailers, and certifying bodies can verify the authenticity of organic products and certifications, fostering trust in the supply chain. |

| Reduced Certification Costs | Blockchain streamlines the certification process by eliminating redundant paperwork, manual audits, and intermediary fees. The transparent and auditable nature of blockchain technology reduces the need for costly third-party verification, making organic certification more accessible and affordable for producers, particularly small-scale farmers. |

| Increased Efficiency | Blockchain automates and streamlines administrative tasks, such as record-keeping, auditing, and compliance management, reducing paperwork, human error, and processing time. Smart contracts enable automatic execution of agreements and transactions, facilitating faster payments, settlements, and supply chain coordination, thereby increasing overall efficiency. |

| Fraud Prevention | Blockchain’s immutable ledger and cryptographic security mechanisms make it highly resistant to fraud, tampering, and counterfeit products. By recording every transaction in a transparent and traceable manner, blockchain technology deters fraudulent activities, such as mislabeling, counterfeit certifications, and product adulteration, protecting the integrity of the organic food supply chain. |

| Metric | Blockchain System | Traditional Supply Chain Management |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency | Utilizes a decentralized and immutable ledger, providing real-time visibility into transactions and data across the entire supply chain. Transparency is inherent in the system architecture, enabling stakeholders to access accurate and up-to-date information about product origins, certifications, and movement. | Relies on centralized databases and manual record-keeping processes, which may lack transparency and lead to discrepancies or delays in accessing information. Limited visibility into the entire supply chain may hinder stakeholders’ ability to track product provenance effectively. |

| Traceability | Employs blockchain technology to create a transparent and auditable record of product movement from farm to fork. Each transaction is securely recorded on the blockchain, enabling stakeholders to trace the journey of products and verify their authenticity and compliance with organic standards. | Relies on traditional record-keeping methods such as paper-based documents or centralized databases, which may lack real-time traceability and are susceptible to errors or manipulation. Tracking product provenance may be challenging, leading to difficulties in verifying product authenticity and compliance. |

| Cost-effectiveness | Streamlines certification processes, reduces administrative burdens, and eliminates intermediary fees through automation and smart contracts. Reduces overall certification costs for stakeholders, particularly small-scale farmers and processors. | Involves manual certification processes, paperwork, and intermediary fees, which can be time-consuming and costly. Requires extensive administrative efforts and third-party verification, leading to higher certification expenses for stakeholders. |

| Scalability | Utilizes innovative approaches such as sharding and side chains to enhance scalability and accommodate growing transaction volumes. Can scale efficiently to meet the demands of a expanding network of participants and transactions. | May face scalability limitations due to centralized databases and legacy systems, particularly when handling large-scale supply chain operations or rapid growth in transaction volumes. Scaling traditional supply chain management approaches may require significant investments in infrastructure and technology upgrades. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).