1. Introduction

The food industry faces increasing complexity due to globalization, regulatory demands, and the need for efficient traceability. Blockchain has emerged as a promising solution, yet existing implementations often rely on a single distributed ledger, leading to data silos and privacy concerns. Despite recent efforts, there is a gap in blockchain solutions that effectively balance transparency, security, and interoperability. This research addresses that gap by introducing FoodFresh, a multi-chain blockchain system that ensures controlled transparency while enabling seamless data exchange across organizations. A thorough literature review highlights existing interoperability challenges and justifies the need for a multi-chain approach.

Blockchain technology, with its decentralized and immutable nature, is seen as a powerful tool for enhancing transparency and trust within supply chains. By enabling the secure and transparent recording of transactions, blockchain allows all participants in a supply chain to access the same trusted data, reducing the likelihood of fraud, errors, and disputes. Furthermore, blockchain can facilitate the optimization of supply chain operations by providing real-time data on product movement, quality, and condition. These benefits have led to the adoption of blockchain in various sectors, including food supply chains, where traceability and food safety are of paramount importance. Current blockchain solutions, such as IBM Food Trust and similar initiatives, typically utilize a single distributed ledger to record and share data among participants. While this approach offers benefits in terms of transparency and traceability, it also presents two significant challenges: (i) the need for organizations to share data across multiple blockchains, which can lead to data silos and interoperability issues, and (ii) the risk of exposing sensitive or proprietary information, as the transparent nature of blockchain can allow unintended access to data by participants who may not require it.

To address these challenges, this paper introduces FoodFresh, a novel approach that leverages a multi-chain architecture to overcome the limitations of single-chain solutions. In FoodFresh, each participating organization in the supply chain controls its own private blockchain, allowing for the secure and private storage of data. A decentralized hub, known as the relay chain, manages cross-chain communication, ensuring that data can be shared between participants in a compliant and controlled manner. This multi-chain approach not only mitigates the risks associated with data transparency but also enables greater flexibility and scalability for food supply chains. The rest of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in the field of blockchain applications for supply chains, highlighting existing solutions and their limitations.

Section 3 provides an overview of the relevant technologies, including food supply chain networks and blockchain interoperability.

Section 4.1 presents the FoodFresh approach in detail, explaining the system architecture and its components. Finally,

Section 6 discusses the conclusions drawn from this research and outlines potential directions for future work.

2. Related Work

Different blockchain-empowered inventory network arrangements have been proposed. For example, it acquainted with a product connector with the interface of an Ethereum-like public blockchain with big business frameworks, permitting organizations to impart data to changing degrees of permeability. Schulz proposed a disseminated store network plan that utilizes space-explicit blockchains for explicit business processes, with a primary center point blockchain interfacing them for correspondence.

Polkadot utilizes a crossover agreement model, isolating block creation (babe! (babe!)) from conclusiveness (grandpa! (grandpa!)), permitting quick block creation and a slower finish. It empowers chain correspondence through the xcmp! (xcmp!) convention, which utilizes a Merkle tree-based lining framework for inconsistent message correspondence between parachains. While xcmp! is still a work in progress, the hrmp! (hrmp!) convention briefly upholds this capability. The essential contrast is that hrmp! stores full message payloads on the hand-off chain, while xcmp! will just store references to the payload, with the objective parachain liable for interpreting it.

3. Background

Blockchain solutions for food supply chains require interoperability to facilitate communication among multiple stakeholders, including farmers, distributors, retailers, and regulators. However, complex networks face scalability issues as the number of participants increases. Additionally, existing solutions lack cross-chain communication mechanisms, hindering efficient data exchange. The FoodFresh system aims to overcome these limitations by incorporating a decentralized relay hub that ensures seamless cross-chain transactions and compliance enforcement.

3.1. Food Production Network Network

A food production network organization (FSCN) alludes to the interconnected arrangement of associations, assets, and data that works with the creation and conveyance of unrefined substances, fixings, and semi-completed items to the last customer. The organization traverses numerous stages, from cultivating and gathering to handling, bundling, appropriation, and at last, retailing. Key partners in a FSCN incorporate ranchers, food processors, wholesalers, coordinated factors specialist co-ops, and retailers, all of which should team up to guarantee the proficient progression of merchandise and data.

In a commonplace FSCN, the unrefined substances like natural products, vegetables, and grains are obtained from ranchers, handled into semi-completed merchandise (e.g., juices, canned merchandise), and afterward disseminated to retailers and wholesalers for conclusive deal to clients. The contribution of different partners implies that the inventory network can be mind boggling, including various business cycles and cooperations.

FSCNs are vigorously affected by different sociopolitical factors, including administrative guidelines, worldwide economic alliance, and shopper inclinations. For example, administrative bodies like the US Division of Horticulture (USDA) force rules and guidelines in regards to food handling, discernibility, and quality control, guaranteeing that food items meet explicit wellbeing and security models. These guidelines are fundamental to keeping up with the monetary practicality and security of the food store network, particularly with regards to new rural items.

Besides, straightforwardness in FSCNs is a huge test, as food handling and quality worries require precise following and confirmation of every item’s excursion across the store network. The combination of blockchain innovation can address these worries by giving a solid, unchanging record of every exchange and cycle, empowering full detectability of food items from homestead to fork.

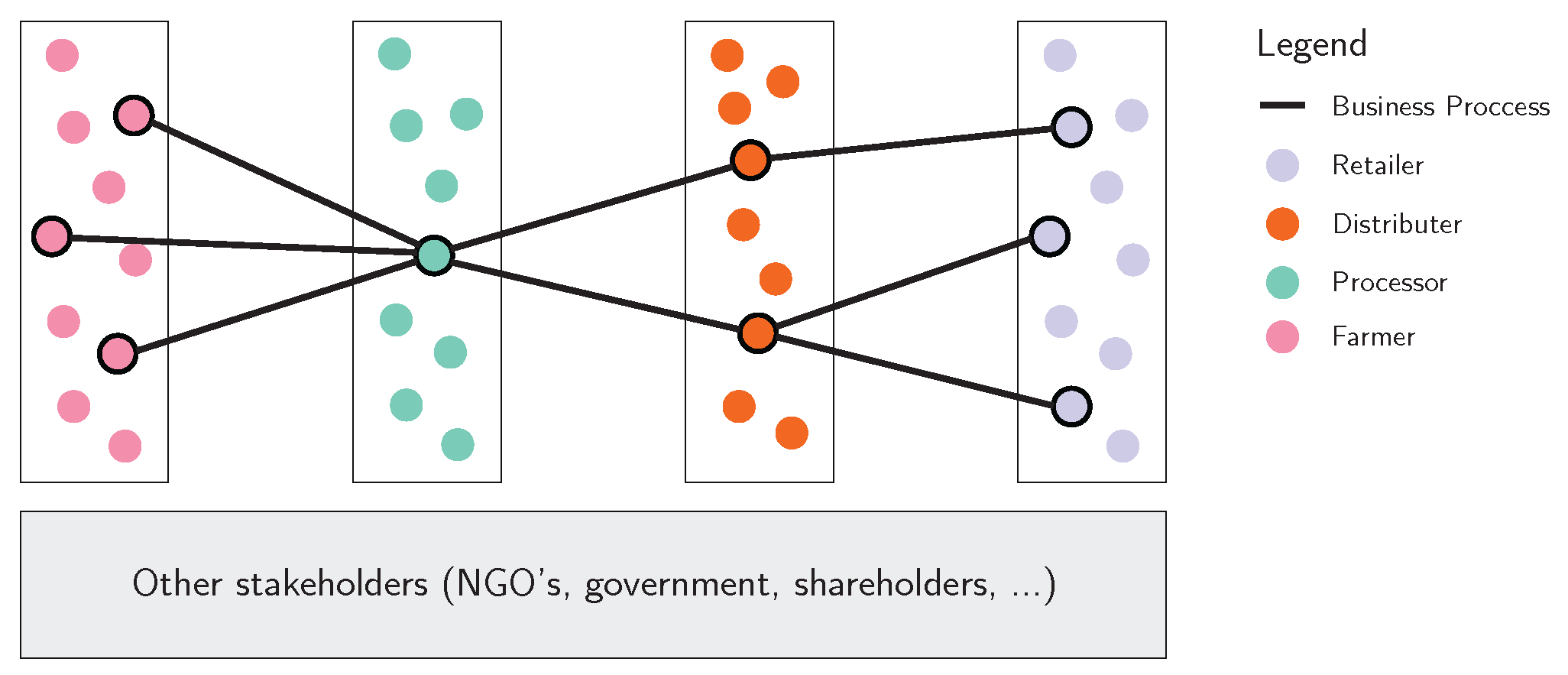

Figure 1 illustrates a simplified representation of an FSCN for fresh agricultural products. The processor (depicted with bold lines) is connected to key stakeholders such as distributors and farmers, representing the core flow of goods and information within the network.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of an fscn! (fscn!)

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of an fscn! (fscn!)

3.2. Blockchain Types

Blockchain technology has evolved into three primary types of systems, each suited to different use cases: public, consortium, and private blockchains. These types differ in terms of permissioning, governance, and the level of decentralization.

Public Blockchains: Public blockchains are permissionless and open to anyone who wishes to participate in the network. They are fully decentralized, with consensus mechanisms such as Proof of Work (PoW) or Proof of Stake (PoS) used to validate transactions. Public blockchains are commonly associated with cryptocurrencies (e.g., Bitcoin, Ethereum) and are used for applications that require transparency and decentralization. Users can join the network, read data, and participate in the consensus process without needing approval from any central authority. Public blockchains are ideal for applications such as cryptocurrency exchanges, digital document validation, and decentralized finance (DeFi) systems.

Consortium Blockchains: A consortium blockchain involves a permissioned network of organizations that have been pre-selected to participate in the consensus process. Unlike public blockchains, consortium blockchains are governed by a group of trusted entities rather than being fully decentralized. This type of blockchain is ideal for enterprise applications where multiple organizations collaborate, such as in supply chain management, healthcare, and financial services. In a consortium blockchain, participating organizations can maintain control over their data while ensuring that transactions are securely validated by trusted peers. It allows for scalability and privacy while still offering some level of decentralization. Consortium blockchains are particularly well-suited for industries such as supply chains, where multiple stakeholders need to interact securely and efficiently.

Private Blockchains: Private blockchains are permissioned blockchains that are controlled by a single organization or entity. In this model, the organization dictates who can participate in the network and access data. Private blockchains are typically used for internal organizational purposes, such as managing assets, auditing transactions, or securing financial records. Since the network is controlled by a central authority, private blockchains offer high performance and low latency, but they lack the decentralization and transparency found in public blockchains. Private blockchains are often used by banks, insurance companies, and corporations to manage sensitive data and business processes.

Each type of blockchain has its advantages and trade-offs, and the choice of blockchain type depends on the specific needs and goals of the application. For instance, a public blockchain may be suitable for applications that require transparency and decentralization, while a consortium blockchain may be a better fit for collaborative efforts in supply chain management, where multiple trusted participants need to exchange information securely and efficiently.

3.3. Blockchain Interoperability

Blockchain interoperability is the ability of different blockchain systems to communicate and share data with one another. As the blockchain ecosystem continues to expand, the need for interoperability has become increasingly important, especially in scenarios where multiple blockchain networks need to interact seamlessly. Interoperability enables different distributed ledger technologies (DLTs) to exchange information in a secure and efficient manner, breaking down the silos between isolated blockchain networks.

Interoperability solutions are generally categorized into three types:

Public Connectors: Public connectors facilitate interoperability between public blockchains, allowing for the exchange of data and assets across different public networks. These solutions are typically built on top of existing public blockchains and allow for cross-chain communication between different blockchain ecosystems. Examples of public connectors include atomic swaps, cross-chain bridges, and federated chains that enable the exchange of tokens or data between distinct public blockchain systems.

Blockchains of Blockchains: This approach involves the creation of a "meta" blockchain network that connects multiple independent blockchains. The idea is to establish a higher-level blockchain that can facilitate cross-chain communication and data sharing among different blockchains. This architecture is often referred to as a blockchain of blockchains or a multi-chain network. One of the most prominent examples of this concept is Polkadot, a blockchain platform that enables different blockchains to interoperate and share data securely and efficiently.

Hybrid Connectors: Hybrid connectors provide interoperability solutions for cases where public connectors and blockchains of blockchains are not feasible or practical. Hybrid connectors combine elements of both public and private systems, enabling secure communication between different types of blockchain networks, including permissioned and permissionless blockchains. This solution is particularly useful in scenarios where different organizations or industries need to collaborate while maintaining their privacy and security requirements.

Interoperability plays a crucial role in facilitating the seamless exchange of data and assets across blockchain networks, promoting collaboration between different organizations, and enabling the creation of larger and more complex ecosystems. In the context of supply chains, blockchain interoperability ensures that data from multiple participants, each operating on different blockchains, can be shared and validated in a secure, transparent, and efficient manner. This is particularly important for creating end-to-end traceability and transparency within a global supply chain system, such as that required in the food industry.

4. FoodFresh

This section provides an in-depth explanation of FoodFresh, a consortium blockchain designed for ensuring interoperability and controlled transparency in food supply chains. FoodFresh leverages blockchain technology to offer seamless data sharing and coordination between different organizations while maintaining data privacy and compliance. The approach and design philosophy are presented in

Section 4.1, while the system architecture, consisting of three distinct tiers, is elaborated in

Section 4.2.1,

Section 4.2.2, and

Section 4.2.3.

4.1. FoodFresh Approach

FoodFresh utilizes a multi-chain approach within a blockchain consortium, wherein each organization within the consortium operates its own private blockchain. This structure allows organizations to retain control over their data while benefiting from secure data sharing via a main relay chain. The relay chain acts as a central hub that coordinates the data exchange between all participants in the supply chain, ensuring that they adhere to common compliance standards and facilitating transparent and immutable data sharing. The approach allows participants to join or leave the ecosystem with minimal disruption, enhancing flexibility and scalability.

Each participant organization in the network has its own private blockchain where it stores and manages its data. The relay chain ensures that organizations comply with predefined rules and allows them to securely share relevant data with other participants. This design ensures that the overall network remains efficient, secure, and transparent while allowing each participant to maintain control over their own operations and data. The FoodFresh approach fosters a collaborative ecosystem, where trust and compliance are central to the system’s design.

4.2. System Architecture

The FoodFresh framework consists of three tiers:

Presentation Tier: Provides a user interface for stakeholders to interact with the blockchain system.

Application Tier: Stores immutable supply chain data using parachains, enabling traceability.

Relay Tier: Facilitates secure and verifiable cross-chain communication through a decentralized relay chain.

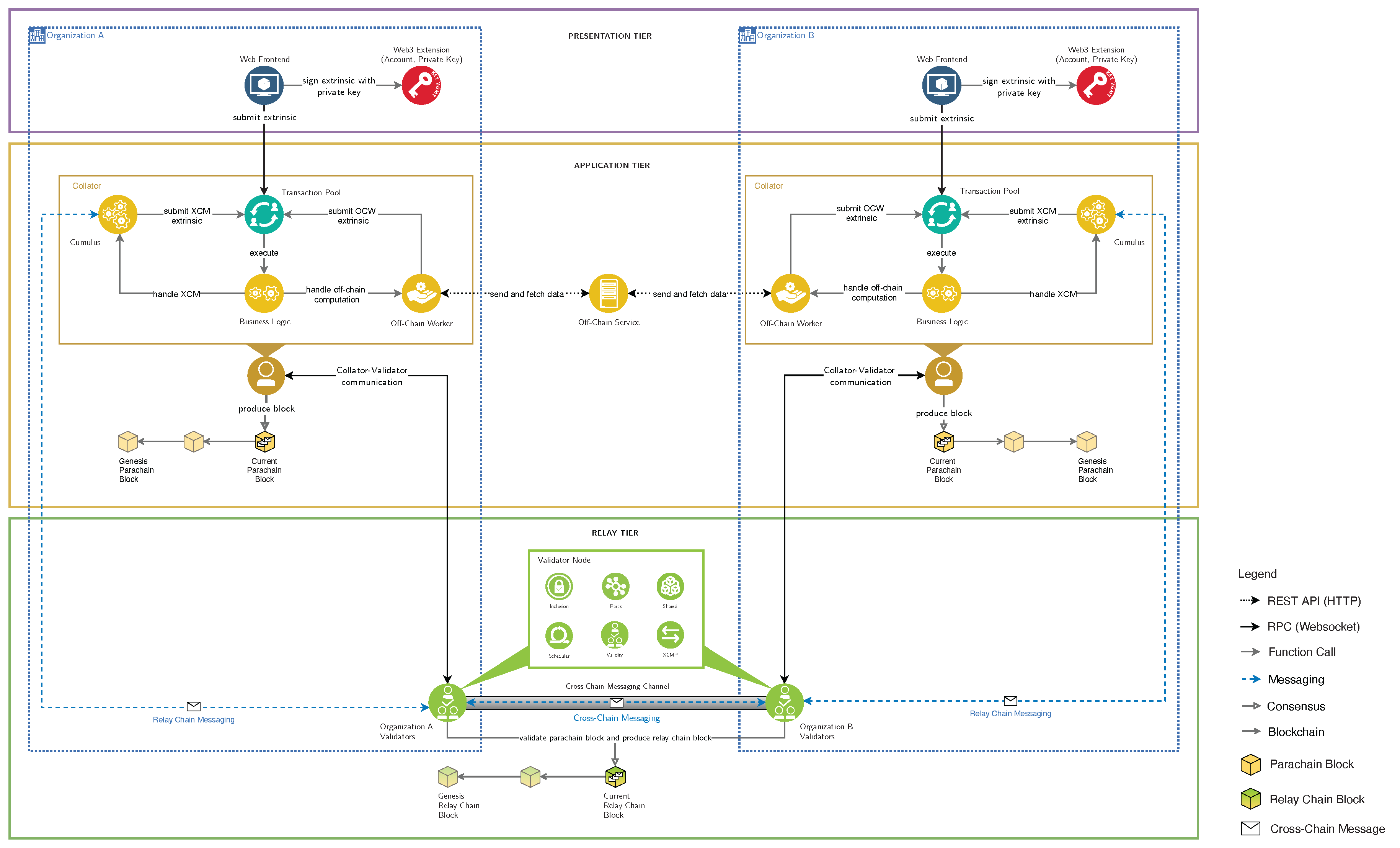

Figure 3 shows the general framework engineering for two interoperating inventory network associations, featuring the communications between the levels.

4.2.1. Presentation Tier

The show level gives the UI through which members cooperate with the FoodFresh framework. It goes about as the front-end layer, empowering clients to perform undertakings, for example, overseeing part consents, enlisting shipments and items, and following shipments all through the store network. The show level speaks with the application level through a websocket association, guaranteeing ongoing cooperation between the client and the framework. Clients can collaborate with the framework utilizing any websocket-able gadget or client.

To cooperate with the blockchain, a program expansion is required. This augmentation permits clients to deal with their blockchain accounts, sign exchanges, and perform different tasks connected with blockchain collaborations. This guarantees that all blockchain-related activities are secure and obvious, furnishing the two members and end-clients with an easy-to-use interface for dealing with their jobs in the store network.

4.2.2. Application Tier

The application tier is responsible for managing the data and operations associated with the individual participants in the FoodFresh ecosystem. This tier consists of parachains, which are specialized blockchains that store immutable data for each organization. Organizations can create products, register shipments, and monitor transport conditions within their respective parachains. The application tier ensures that all data related to shipments is tracked from creation to delivery, allowing for full traceability.

The subsystem Cumulus is part of the application tier and enables cross-chain messaging between parachains. This subsystem allows parachains to send and receive messages from each other, facilitating the sharing of relevant data, such as shipment status and transport conditions. Furthermore, an outer correspondence covering (OCW) is utilized to impart the most recent shipment status with outside frameworks, guaranteeing that the inventory network information is synchronized with outside partners.

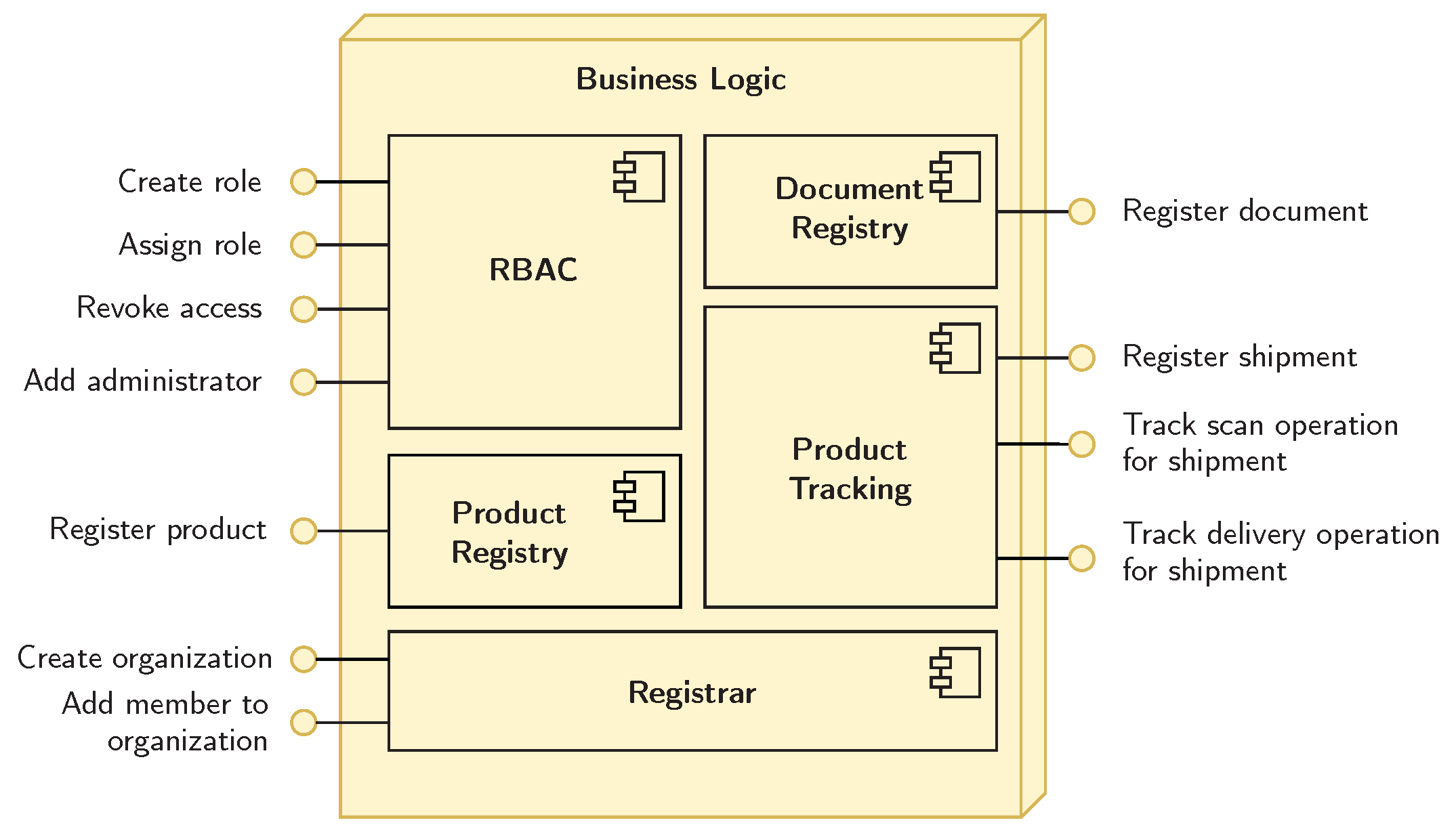

Figure 2.

An overview of the business logic, decomposed into pallets.

Figure 2.

An overview of the business logic, decomposed into pallets.

4.2.3. Relay Tier

The transfer chain is the focal part of the FoodFresh framework, giving the important foundation to cross-chain correspondence and approval. The transfer chain associates the parachains, empowering them to convey safely and effectively. It oversees cross-chain messages utilizing the xcm! (xcm!) convention, which works with the exchange of information and guarantees that messages are conveyed in an ideal and requested design.

Validators assume a pivotal part in the transfer chain. They are liable for confirming the legitimacy of parablocks, which contain exchange data from the parachains, and for guaranteeing that the data inside these blocks is precise. Validators additionally partake in the agreement cycle to deliver the transfer chain blocks in light of legitimacy explanations from other validators. Moreover, they handle cross-chain messages and guarantee that information is communicated accurately between parachains. This ensures that messages are conveyed in good shape and that the respectability of the information is kept up with across the organization.

The transfer chain guarantees that correspondence between parachains is dependable and productive. It utilizes a progression of systems to check that messages show up immediately, are handled all put together, depend on finished exchanges from the sending parachain. This guarantees that the framework is powerful, secure, and fit for taking care of enormous volumes of cross-chain correspondence.

4.3. Substrate Framework

FoodFresh is built on the Substrate framework, a modular and flexible platform for building custom blockchains. Substrate was chosen for its ability to adapt to the specific requirements of food supply chains, such as the frequent updates to regulatory compliance. The framework’s modular nature allows developers to customize and extend the functionality of the blockchain to suit the needs of different supply chain participants.

Substrate is implemented in Rust, a programming language known for its performance, reliability, and safety features. Rust ensures that FoodFresh can handle complex operations efficiently while avoiding common issues such as memory leaks and data races. Additionally, Substrate supports off-chain processing via the OCW, which allows long-running tasks to be executed without affecting the performance of the blockchain. This is essential for the handling of supply chain data, which often requires real-time processing and interaction with external systems.

4.4. Deployment

FoodFresh requires both validator and collator hubs to successfully work. The validator hubs are liable for dealing with the transfer chain, guaranteeing agreement, and taking care of cross-chain correspondence. The collator hubs deal with the parachains and store the information connected with individual associations inside the framework. Hubs can be conveyed either locally inside an association’s foundation or somewhat through a cloud specialist co-op, for example, Amazon Web Administrations.

For parachains to take part in cross-chain correspondence, they should initially be enlisted on the transfer chain. As per the Collator Convention, the transfer chain should have validator hubs for n parachains to guarantee legitimate correspondence. For the model execution of FoodFresh, two transfer tie hubs are set up to interface a solitary parachain. Furthermore, the transfer fastens requirements to acquire the beginning condition of the para chain and the WebAssembly runtime approval capability to approve para blocks.

Figure 3.

Overview of my methodology. The design is made out of three levels: show, application, and relay.

Figure 3.

Overview of my methodology. The design is made out of three levels: show, application, and relay.

5. Results and Evaluation

To validate FoodFresh, a simulated supply chain dataset containing shipment records, timestamps, and temperature logs was used. The evaluation metrics include:

Transaction Latency: Average time for a cross-chain transaction.

Scalability: Performance analysis with increasing participants.

Data Integrity: Detection rate of unauthorized data modifications.

6. Conclusion & Future Work

In today’s highly competitive and rapidly evolving business landscape, fostering long-term, mutually beneficial relationships between participants in a supply chain has become increasingly essential. As the complexity of global supply chains continues to grow, there is a greater need for technological solutions that not only improve operational efficiency but also ensure the security, transparency, and trustworthiness of the information exchanged between different stakeholders. Blockchain technology, with its decentralized, immutable, and transparent nature, is increasingly being recognized as a promising tool for improving supply chain operations. It offers a unique solution to many of the challenges faced by industries today, particularly in terms of providing end-to-end traceability, ensuring the integrity of transactions, and enabling efficient, secure data sharing.

In this paper, I introduced FoodFresh, a multi-chain consortium-based blockchain approach designed specifically for food supply chain networks. FoodFresh leverages the power of blockchain technology to enhance interoperability, controlled transparency, and the seamless exchange of data between organizations within the supply chain. The core principle of FoodFresh is to allow each participating entity to retain control over its own data through private blockchains while benefiting from the collaborative sharing of information through a centralized relay chain. This relay chain acts as a hub that facilitates cross-chain communication, ensuring compliance with overarching consortium rules, while allowing individual participants to adapt and modify their operations to meet specific business needs and regulatory requirements.

The unique value proposition of FoodFresh lies in its ability to combine the advantages of decentralized governance, data integrity, and secure information sharing in a manner that addresses the privacy concerns typically associated with blockchain transparency. By enabling participants to retain control over their own data while ensuring that they can interact with other participants in the network, FoodFresh addresses the significant challenges posed by data silos and limited interoperability between blockchain systems. This approach enhances operational efficiencies, reduces friction between supply chain participants, and helps to create a more transparent, accountable, and secure food supply chain system.

Moreover, the design and principles behind FoodFresh are not limited to the food supply chain industry. The fundamental concepts of interoperability, decentralized data governance, and controlled transparency can be readily applied to a variety of other industries that require the secure distribution or transfer of sensitive data. Industries such as healthcare, logistics, and manufacturing, where transparency, traceability, and security are of paramount importance, could greatly benefit from adopting a similar multi-chain approach. By facilitating seamless, secure communication across different entities within these sectors, such an approach could help to reduce inefficiencies, mitigate risks, and improve the overall quality and security of data exchanged across supply chains.

In conclusion, the FoodFresh approach not only contributes to enhancing the performance and transparency of food supply chains but also offers a blueprint for future developments in blockchain applications for cross-industry data exchange. With the continued growth and evolution of blockchain technology, future research could explore the implementation of FoodFresh in other industries, further refining the principles of multi-chain interoperability, decentralized data governance, and controlled transparency. Such efforts will likely lead to the creation of more robust and adaptable supply chain networks across diverse sectors, contributing to greater efficiency, security, and trust in the exchange of sensitive data. Future research will explore advanced cross-chain messaging protocols, real-world pilot testing, and AI-driven analytics for predictive insights into supply chain risks.

References

- R. Belchior, J. Rodrigues, A. L. Ferreira, and M. M. Freire, "A survey of blockchain interoperability," IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 48156–48175, 2021.

- H. Li, Z. Zhang, H. Zhang, et al., "Blockchain technology applications in supply chain management: A comprehensive review," Computers & Industrial Engineering, vol. 154, p. 107135, 2021.

- M. Ghorbani, M. Zarei, and M. Khoshgoftaar, "Blockchain-based solutions for food supply chain traceability: A review," Food Control, vol. 130, p. 108200, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhou, J. Liu, L. Wei, and Z. Liu, "Blockchain in food supply chains: A survey and future research directions," Food Research International, vol. 156, p. 111204, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Mohammad, P. Rajendran, M. Thirumalai, and G. Srinivasan, "Blockchain technology applications in agriculture supply chain management," Agricultural Systems, vol. 196, p. 103303, 2022.

- X. Qian, W. Zhang, and D. Liu, "Blockchain-enabled traceability for food supply chains: A review of applications and future research trends," Computers in Industry, vol. 139, p. 103640, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Tian, J. Zhang, X. Li, and Y. Zhang, "Blockchain and IoT integration for food safety management: A comprehensive review," International Journal of Information Management, vol. 62, p. 102447, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, C. Li, Z. Wang, and Y. Hu, "Blockchain for food safety and quality traceability: Opportunities and challenges," Food Control, vol. 141, p. 109172, 2023.

- Y. Li, G. Li, X. Xu, and M. Wang, "Smart contracts and blockchain technology for supply chain management: A systematic review and future research directions," International Journal of Production Research, vol. 61, no. 14, pp. 4470-4485, 2023.

- P. Garg, R. Sharma, and R. S. Sharma, "Blockchain-based food safety management in the food supply chain: A comprehensive review and future directions," Computers & Electrical Engineering, vol. 103, p. 107481, 2023.

- A. Ali, C. Liu, and W. Yang, "Blockchain for transparent and efficient food supply chains: A review of applications and challenges," Journal of Food Engineering, vol. 366, p. 110367, 2023.

- J. Chen, X. He, and Y. Li, "Integration of blockchain and Internet of Things for food traceability: A systematic review," Food Control, vol. 146, p. 109657, 2024.

- O. Galdamez, R. Diaz, and J. J. Lopez, "Blockchain and its impact on sustainable food supply chain management: A comprehensive analysis," Sustainable Production and Consumption, vol. 26, pp. 88–101, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lee, H. Cho, and J. Park, "Blockchain technology for decentralized supply chain management: A systematic review of applications and challenges," Journal of Business Research, vol. 140, pp. 197–212, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).