1. Introduction

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a well-established, non-invasive index of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity, reflecting the dynamic interplay between sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation of cardiac function [

1]. It is widely used in physiological and clinical settings to evaluate cardiovascular regulation, stress reactivity, and recovery capacity [

2]. HRV’s variability across multiple time scales—captured by time-domain, frequency-domain, and non-linear indices—is considered a marker of both physiological adaptability and neurocardiac resilience to stressors such as immersion and hypoxia [

1,

3]. Diving represents a complex physiological stressor—combining immersion, increased ambient pressure, thermal load, and altered breathing gas composition—that significantly influences autonomic control.

Recent evidence suggests that individual cardiac responses to diving are partially determined by resting HRV profiles, particularly short-term vagal indices, highlighting their predictive potential for parasympathetic-mediated bradycardia during immersion. Interestingly, similar patterns have long been recognized in elite breath-hold divers, where trigeminocardiac reflexes and chemoreflex-mediated bradycardia act synergistically to preserve oxygen [

4,

5]. This bradycardic response, along with reductions in cardiac output and ventilatory drive, has also been observed in trained freedivers during repeated apnea bouts, suggesting a robust cardiovascular adaptation to hypoxic stress [

6]. While open-circuit SCUBA diving has been well-characterized, typically showing an initial parasympathetic surge due to the diving reflex, followed by sympathetic dominance during activity and a vagal rebound in recovery, with studies in experienced divers confirming a persistent parasympathetic predominance throughout immersion under real conditions [

2], the autonomic effects of closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) diving remain underexplored.

HRV recordings during open-circuit dives have shown that descent and bottom phases are characterized by elevated SDNN, RMSSD, and HF power, reflecting vagal predominance, while the recovery phase tends to show increased LF/HF ratios consistent with sympathetic reactivation. These findings are further supported by field investigations in SCUBA divers, which revealed dynamic HRV fluctuations across all dive phases, with parasympathetic predominance at depth and transient sympathetic surges during descent and ascent, reinforcing the modulatory role of environmental and task-related stressors on autonomic regulation [

7].

Other studies have shown transient reductions in SDNN and time-domain indices during immersion and rapid vagal reactivation post-dive, independent of depth, in recreational divers undergoing shallow air dives at 10 and 20 meters [

8]. These effects appear attenuated in CCR dives, likely due to the buffering effect of constant inspired oxygen pressure on autonomic cardiac control [

9]. These physiological shifts are paralleled by central changes, as cognitive performance and mood are modulated by autonomic dynamics during exposure to hyperbaric and cold environments—supporting the relevance of integrating neurocognitive endpoints with HRV in diving medicine [

10]. Recent studies using dry chamber simulations with wearable sensors have further validated the feasibility of combining HRV, EEG, and oxygen saturation metrics to monitor real-time cognitive load and physiological strain in hyperbaric contexts [

11,

12].

However, the reliability of wearable HRV monitoring in real-life and field conditions remains an open challenge. A recent systematic review highlighted considerable discrepancies in accuracy among different devices and protocols, pointing to the need for standardized validation procedures before clinical or operational deployment [

13].

Emerging evidence suggests that cold, more than pressure alone, may act as the principal driver of parasympathetic dominance over time in cold-water dives, initially through the trigeminocardiac reflex and later via cold-induced peripheral vasoconstriction and baroreceptor-mediated responses [

14]. A pivotal study conducted in Arctic conditions by Lundell et al. explored the temporal evolution of HRV responses during prolonged cold-water immersion in Finnish Navy divers. The authors observed a biphasic parasympathetic trend: an early increase during the first minutes—likely reflecting the trigeminocardiac component of the diving reflex—was followed by a transient decline and then a progressive parasympathetic reactivation over the course of the dive, attributed to sustained cold exposure and baroreflex engagement [

15].

Otherwise, CCR diving, characterized by longer underwater duration and stable oxygen partial pressure (PO₂), introduces additional physiological complexities. Limited existing data point to fluctuating sympathovagal activity and a potential for simultaneous activation of both ANS branches, raising questions about arrhythmogenic risk and individual tolerance. Notably, both HRV monitoring during real-life dive incidents and clinical observations in the post-dive period support the hypothesis of an autonomic conflict scenario, characterized by an early vagal dominance followed by sympathovagal desynchronization and coactivation—patterns that may increase arrhythmogenic susceptibility in predisposed individuals [

17,

18].

Similar autonomic coactivation has also been observed in normobaric hypoxic environments, where concurrent sympathetic and parasympathetic activity—possibly mediated by chemoreflex mechanisms—was associated with increased cardiac electrical instability, suggesting a broader relevance of HRV monitoring for identifying individuals at arrhythmic risk beyond diving contexts [

18]. A more recent investigation involving 26 experienced CCR divers confirmed this biphasic trend and further revealed a transient initial increase in SNS activity during immersion—likely related to cold stress and preparatory physical effort—followed by a concurrent rise in both ANS branches during descent, potentially enhancing arrhythmogenic risk and supporting the need for an adaptation phase before exertion [

19]. A previous study in cold-water CCR diving (2–4 °C, ~45 m depth) observed an early parasympathetic spike linked to the trigeminocardiac reflex, followed by persistent vagal tone and rising sympathetic activation due to sustained cold exposure.

Yet, a detailed HRV assessment spanning the full dive timeline (before, during, and after immersion) under controlled conditions remains to be defined. Notably, while simulated hyperbaric studies in dry and humid chambers have shown that humidity, body position, and thermal conditions can significantly affect HRV-derived indices—highlighting reduced parasympathetic tone and elevated sympathetic responses in humid settings—real-world CCR diving data under operational conditions are still scarce [

20].

This case study aims to fill that gap by characterizing ANS modulation across pre-dive, intra-dive, and post-dive phases in a trained military diver undergoing a CCR dive using the MCM100 apparatus. HRV was analyzed using time domain (SDNN, RMSSD), frequency domain (LF/HF ratio), and nonlinear (SD1, SD2, entropy) parameters via Kubios software. We hypothesized a biphasic autonomic response: an initial parasympathetic withdrawal during immersion followed by partial vagal reactivation in recovery. This physiological profiling contributes to our understanding of autonomic resilience in extreme environments and highlights the utility of HRV metrics in optimizing safety and performance in professional diving.

2. Results

2.1. Overview of Time-Domain, Frequency-Domain, and Nonlinear HRV Parameters

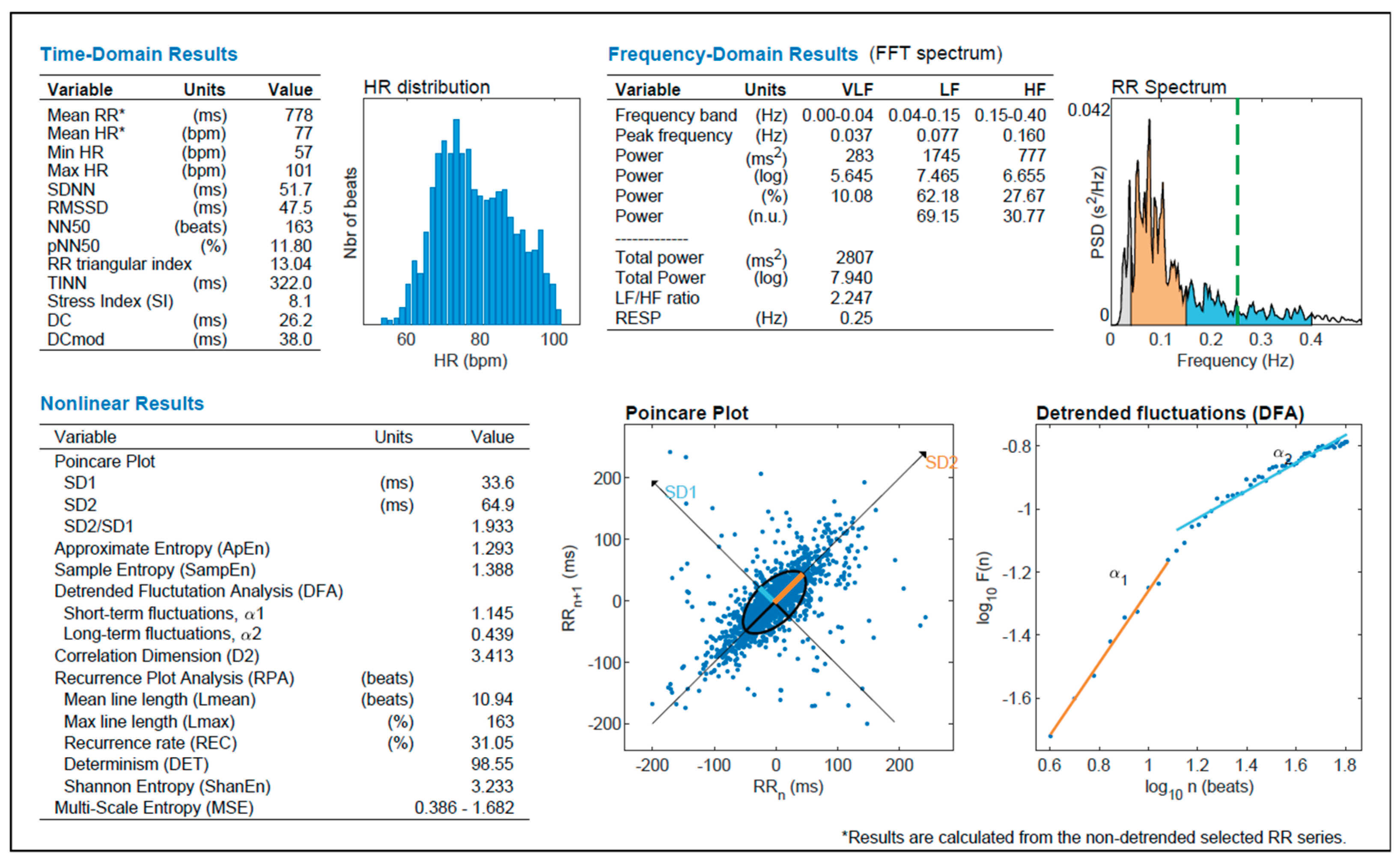

HRV analysis was conducted across three phases of a CCRdive using the MCM100 system: pre-dive (baseline), immersion, and post-dive recovery. HRV parameters were extracted with Kubios software and included time-domain, frequency-domain, and nonlinear indices. Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied applied independently to each phase to reduce dimensionality and identify latent patterns of autonomic regulation.The analysed HRV features time-domain metrics (mean RR, SDNN, RMSSD), frequency-domain indices (LF, HF, LF/HF), and nonlinear measures (SD1, SD2, SD2/SD1, DFA α1 and α2, sample entropy, and approximate entropy). Components with eigenvalues >1 were retained, and Varimax rotation was used to enhance interpretability.

- Pre-dive: Two components were extracted. The first component (explaining the majority of variance) was primarily loaded by vagal and complexity-related variables such as RMSSD and SampEn, while the second reflected sympathetic or or mixed autonomic activity (,i.e.: mean HR, LF/HF).

- Immersion: a single dominant component emerged, suggesting a collapse of HRV complexity into a unified physiological pattern, likely due the environmental constraints (,i.e.: hydrostatic pressure, hyperoxia, ventilatory drive).

- Post-dive: Again, a single component was retained, indicating partial autonomic recovery, but with persistently reduced dimensionality compared to baseline.

This phase-dependent shift from a multifactorial (pre-dive) to unidimensional autonomic signature (during and post-dive) suggests a temporary reduction in HRV complexity during CCR exposure, followed by incomplete restoration post-dive.

2.1.1. Time-Domain Indices

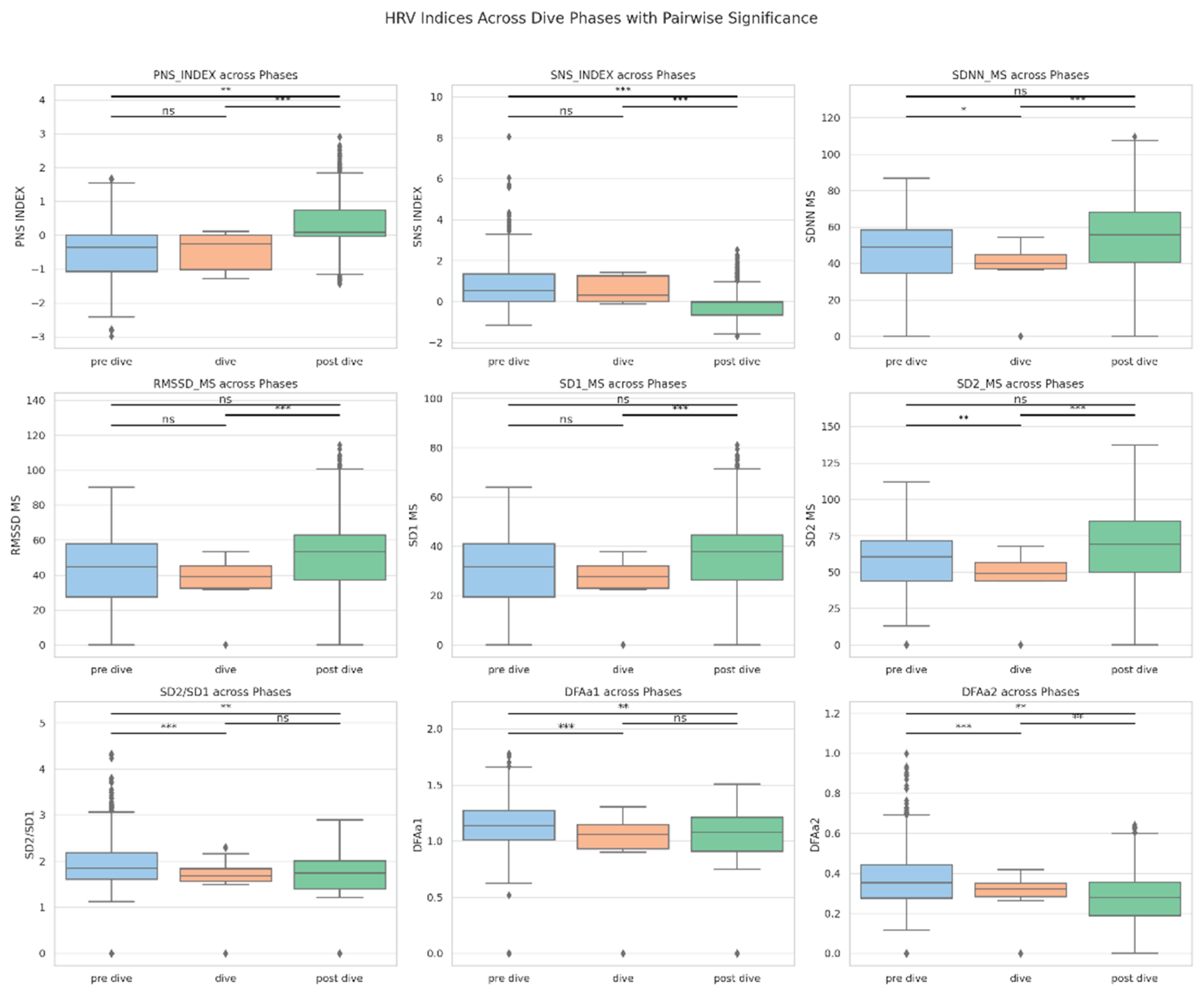

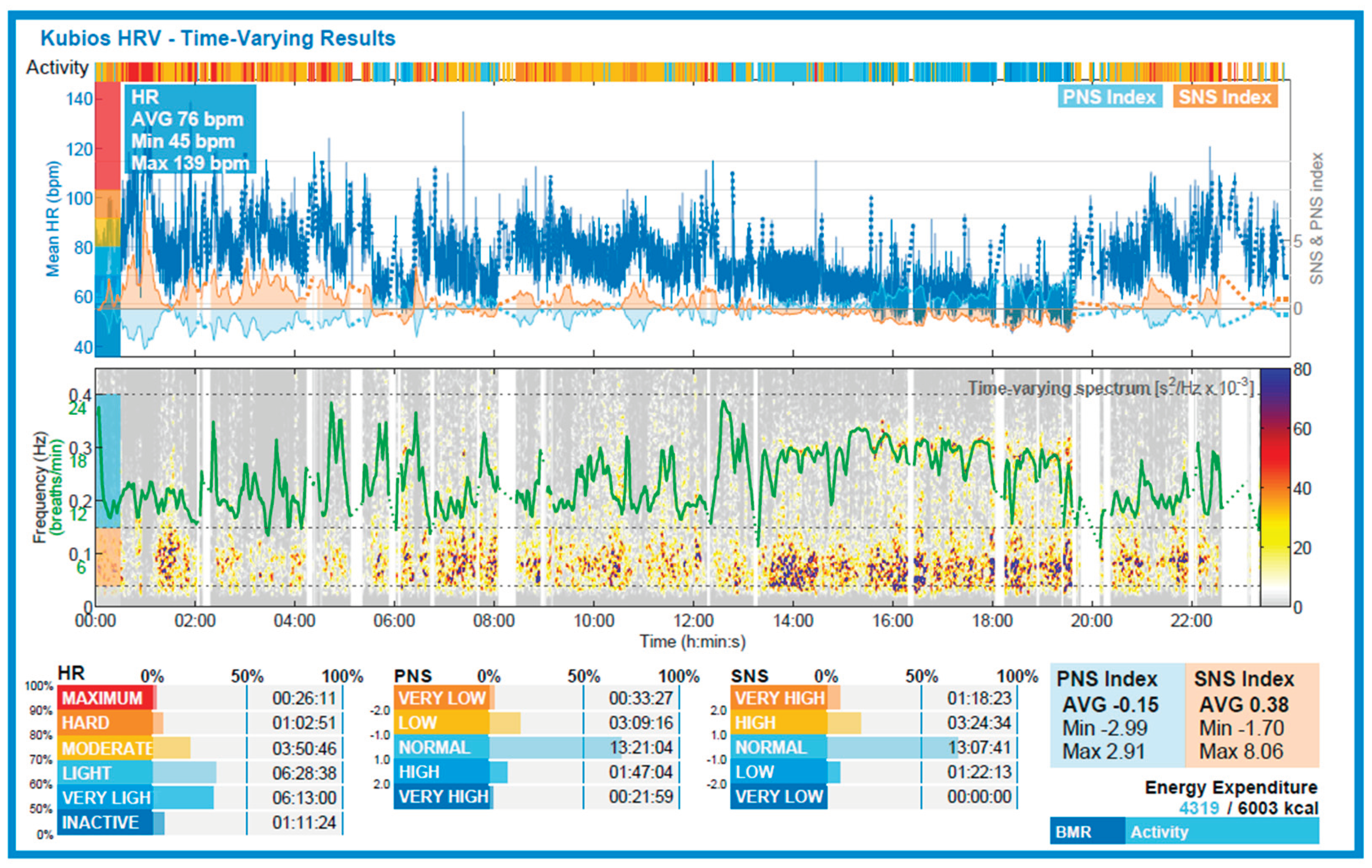

SDNN decreased significantly during immersion, indicating a reduction in overall HRV. RMSSD and SD1 exhibited non-significant downward trends during immersion. However, SDNN and RMSSD values returned to baseline rather than exceeding them, suggesting a recovery rather than overshoot. Post-dive, SDNN, RMSSD, and SD1 significantly increased compared to immersion, reflecting parasympathetic reactivation (see

Figure 2). Although mean heart rate was not included in the statistical analysis, time-resolved HR data from wearable monitoring (

Figure 3) revealed a visible increase during the dive phase (12:15–12:35), followed by a gradual decrease in the post-dive period. This pattern aligns with the expected transient sympathetic activation during immersion and subsequent vagal reactivation, supporting the physiological interpretation of the observed HRV trends [

19].

2.1.2. Frequency-Domain Analysis

The LF/HF ratio demonstrated a trend toward increase during immersion and normalization post-dive, though these changes were not statistically significant. Future studies with larger sample sizes or repeated dives may help elucidate spectral HRV responses to CCR diving.

2.1.3. Nonlinear Metrics

SD1, derived from Poincaré plots, declined non-significantly during immersion and rose significanlty in the post-dive phase, suggesting parasympathetic reactivation. SD2 showed a similar trend, but without statistical significance. The SD2/SD1 ratio remained stable across phases, indicating preserved proportionality between short- and long-term HRV dynamics.

Entropy-based indices (SampEn and ApEn) showed a decreasing trend during immersion and partial post-dive recovery, consistent with reduced physiological complexity under environmental and equipment-related stressors. However, these changes did not reach significance in this single-subject analysis.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Given the single-subject design and non-normal distribution of some HRV variables, non-parametric tests were applied. A Friedman test was used to assess differences across the three phases. For significant results (p < 0.05), Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted for pairwise comparisons.

Pre vs. During immersion: SDNN significantly decreased, suggesting reduced HRV. RMSSD and SD1 trended downward. PNS_INDEX and SNS_INDEX showed no significant change. During vs. Post immersion: PNS_INDEX increased and SNS_INDEX decreased significantly, indicating vagal reactivation and sympathetic withdrawal. SDNN, RMSSD, and SD1 all increased significantly. Pre vs. Post immersion: PNS_INDEX and SNS_INDEX differed significantly from baseline, suggesting ongoing autonomic adjustment, while SDNN and RMSSD were statistically unchanged, consistent with recovery to baseline. All analyses were conducted in Python 3.11 using the SciPy 1.11 library. Visualizations were generated with Seaborn and Matplotlib. PCA was performed independently for each dive phase, retaining components with eigenvalues >1 and applying Varimax rotation for enhanced interpretability.

2.3. Subjective Workload Assessment

To complement physiological findings, subjective workload was assessed immediately after surfacing using the full version of the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) via the AHRQ mobile application. The subject completed both the pairwise comparison of domains and the rating scale. Frustration emerged as the most heavily weighted and highest-rated domain (rating: 50/100; weight: 5; adjusted score: 250), followed by Performance (rating: 10; weight: 4) and Physical Demand (rating: 15; weight: 3). The total weighted score computed by the app was 25.33, indicating a low to moderate perceived workload. The low rating for Mental, Physical, and Temporal demands suggests the diver did not experience significant cognitive or physical strain, consistent with familiarity with the task and limited exertion during the dive. Blood pressure measurements obtained across the dive phases showed values of 110/65 mmHg pre-dive, a nadir of 96/60 mmHg during immersion, and a return to baseline immediately post-dive. This transient decrease during immersion did not result in clinical symptoms and was consistent with the subject’s known baseline profile and increased parasympathetic activity.

3. Discussion

This case study aimed to explore autonomic nervous system (ANS) modulation through HRV parameters in a military diver undergoing a CCR dive using MCM100 equipment. The diving environment—characterized by elevated ambient pressure, hyperoxia, and moderate thermal load—posed a unique combination of physiological stressors, eliciting a phase-dependent autonomic adjustments. A significant reduction in SDNN during immersion compared to both pre- and post-dive phases reflects an acute drop in overall HRV, likely due to vagal withdrawal, reduced baroreflex sensitivity and sympatho-vagal imbalance under hydrostatic and hyperoxic stress.

Although RMSSD and SD1 showed a decreasing trend during immersion, their reduction did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to interindividual variability and compensatory mechanisms. Following the dive, SDNN, RMSSD, and SD1 all increased significantly compared to the immersion phase, indicating rapid parasympathetic reactivation and autonomic recovery. The fact that SDNN and RMSSD returned to, but did not exceed, baseline values suggest normalization without evidence of overshoot.

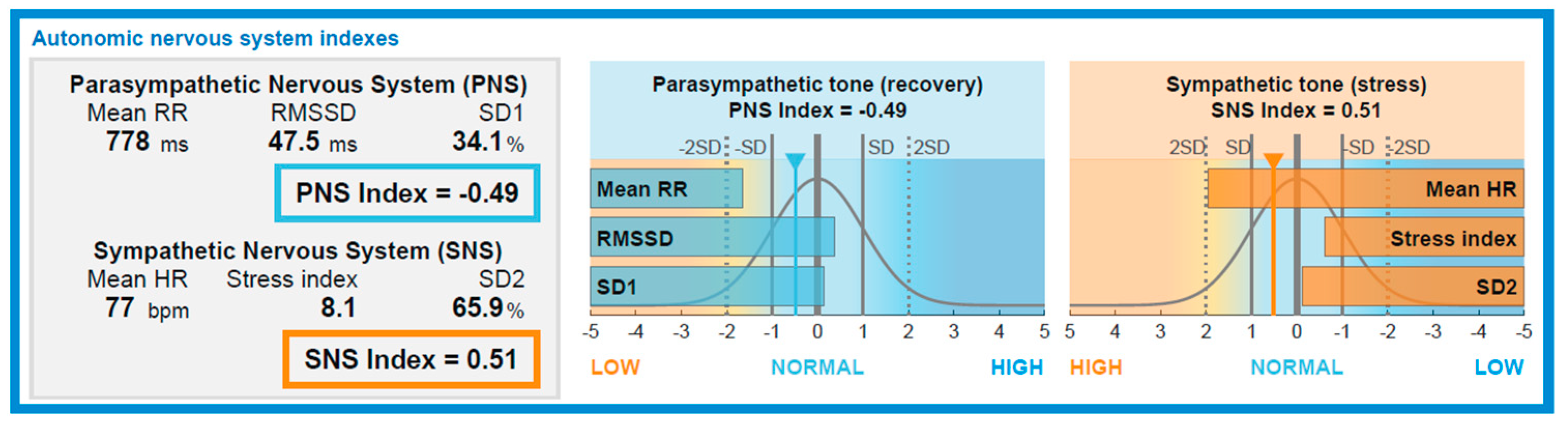

In contrast to initial expectations, PNS\_INDEX and SNS\_INDEX did not significantly change between the pre-dive and immersion phases. However, a significant post-dive increase in PNS\_INDEX and simultaneous decrease in SNS\_INDEX indicate a shift toward parasympathetic rebalancing. These findings support the hypothesis of a biphasic autonomic response, with sympathetic predominance during immersion followed by vagal restoration upon resurfacing (see

Figure 5). This autonomic shift was paralleled by a transient drop in blood pressure during immersion (minimum 96/60 mmHg), with values returning to the subject’s baseline of 110/65 mmHg post-dive. Given the subject’s known chronic low resting blood pressure, this response is likely the result of enhanced vagal tone and baroreflex sensitivity, consistent with parasympathetic predominance during recovery.

To further elucidate autonomic modulation, a phase-specific Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied. Two distinct components emerged during the pre-dive phase, suggesting a multifactorial autonomic architecture involving vagal activity and system complexity. During immersion, only a single principal component was retained, reflecting autonomic convergence and reduced dimensionality—likely due to the combined influence of hydrostatic pressure, constrained respiratory patterns through CCR, and uniform stress input from environmental exposure.

After resurfacing, a single component persisted, indicating only partial restoration of the autonomic complexity. From a nonlinear perspective, lower SD2/SD1 and entropy indices during immersion corroborate a temporary suppression of system adaptability, consistent with prior SCUBA and apnea diving studies. These reductions in complexity could reflect limited flexibility in autonomic output under CCR-induced respiratory and environmental load. Environmental and behavioral factors, including pre-dive heat exposure (~35 °C while wearing a dry suit) and resistance training, may have influenced baseline autonomic tone and recovery kinetics (see

Figure 4).

Additionally, a brief resurfacing to assist a teammate was included in the dataset due to signal stability, although it may have transiently influenced the physiological profile. In line with this interpretation, subjective workload data obtained via the weighted NASA-TLX revealed Frustration as the most impactful domain, contributing disproportionately to the final score. Although physical and mental demands were rated low, the diver experienced high emotional and performance-related stress, consistent with the observed difficulty in middle ear equalization after a brief resurfacing. This episode prevented a full return to depth and likely represented the principal psychological stressor of the dive, rather than the environmental or physical load itself. The combination of low HRV complexity, transient physiological disruption, and elevated frustration index underscores how even brief operational interruptions can shift autonomic and subjective responses in trained military divers. This observation suggests the importance of integrating subjective stress indices with physiological markers when assessing diver resilience and mission impact, especially in scenarios involving task interruption or incomplete protocol execution.

The use of a wearable ECG device (RootiRX) combined with high-resolution HRV analysis via Kubios Premium ensured methodological accuracy. While limited to a single-subject design, this case offers valuable model for understanding individual autonomic responses to CCR diving. Future work should extend to larger cohorts, open- vs. closed-circuit systems, and apply longer follow-up post-dive windows to capture delayed autonomic normalization. The integration of time-domain, frequency-domain, and nonlinear HRV indices—enhanced by multivariate analysis—provides a robust approach for assessing diver readiness, fatigue, and stress adaptation. Such approaches may also support risk stratification, performance optimization and mission planning in high-stakes military diving operations (see

Figure 6).

3.1. Correlation Analysis

The matrix correlation (see

Table A1) supports the interpretation of coordinated and phase-sensitive autonomic modulation. Strong and statistically significant positive correlations were observed among key time-domain HRV indices. Specifically, SDNN correlated robustly with RMSSD, SD1, and SD2 (all r > 0.95, p < 0.01), confirming that short- and long-term HRV variability co-vary under CCR-induced stress.. The SD2/SD1 ratio—a nonlinear surrogate of system complexity and sympathovagal balance—was also positively correlated with SDNN and RMSSD, reinforcing its value as composite marker. An inverse, near-perfect correlation between SNS_INDEX and PNS_INDEX (r = –0.99, p < 0.01), reflects the physiological antagonism of sympathetic and parasympathetic branches. Interstingly, neither index significantly changed between the pre-dive and immersion phases, suggesting a relatively stable but constrained autonomic balance during underwater exposure. More pronounced autonomic shifts occurred only post-dive, consistent with a delayed parasympathetic rebound.

3.2. Principal Component Analysis Reveals Phase-Dependent Autonomic Reorganization

PCA applied to HRV indices across the three dive phases revealed distinct reconfigurations in autonomic functional architecture. In the pre-dive phase, two components were identified. The first was associated with parasympathetic tone and complexity-related variables (i.e.: RMSSD, SD1, SampEn), while the second integrated heterogeneous variables including SNS_INDEX, SD2/SD1, and other stress-linked features, reflecting a multidimensional and adaptable autonomic profile, combining vagal predominance with latent sympathetic readiness.

In contrast, only one component emerged during immersion, indicating a reduction in autonomic dimensionality. This simplification reflects the physiological constraints imposed by CCR-specific factors, including hydrostatic load, hyperoxic breathing and reduced respiratory variability. Notably, CCR setup increases anatomical dead space through the mouthpiece and corrugated hoses, potentially affecting gas exchange and ventilatory mechanics, thereby influencing autonomic output.

The convergence of both linear and nonlinear HRV indices into a single axis of variation suggests a narrowed adaptive range of physiological flexibility during immersion. After resurfacing, PCA continued to reveal a single component, albeit with modified loadings, suggesting incomplete restoration of baseline complexity This dissociation between parameter normalization and structural reintegration may imply residual dysregulation of autonomic networks or adaptation lag post-dive.

In summary, the transition from a two-component structure pre-dive to a single-component organization during and after the dive emphasizes phase-dependent autonomic reorganization. While average HRV metrics may normalize post-dive, the persistence of reduced complexity and coordination underscores a subtler, ongoing process of physiological recovery, with potential relevance for post-dive fatigue, cognitive performance, and mission readiness in operational diving scenarios.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subject and Dive Protocol

This case study involved a 32-year-old male diver serving as a palombaro (military diver) in the Italian Navy. The subject, physically fit and regularly engaged in strength and hypertrophy training (with high loads and moderate volume), had performed a gym workout the morning before the dive. He typically sleeps around six hours per night.

Resting blood pressure values for the subject are chronically low, averaging around 110/65 mmHg in the absence of symptoms, consistent with his individual physiological baseline.

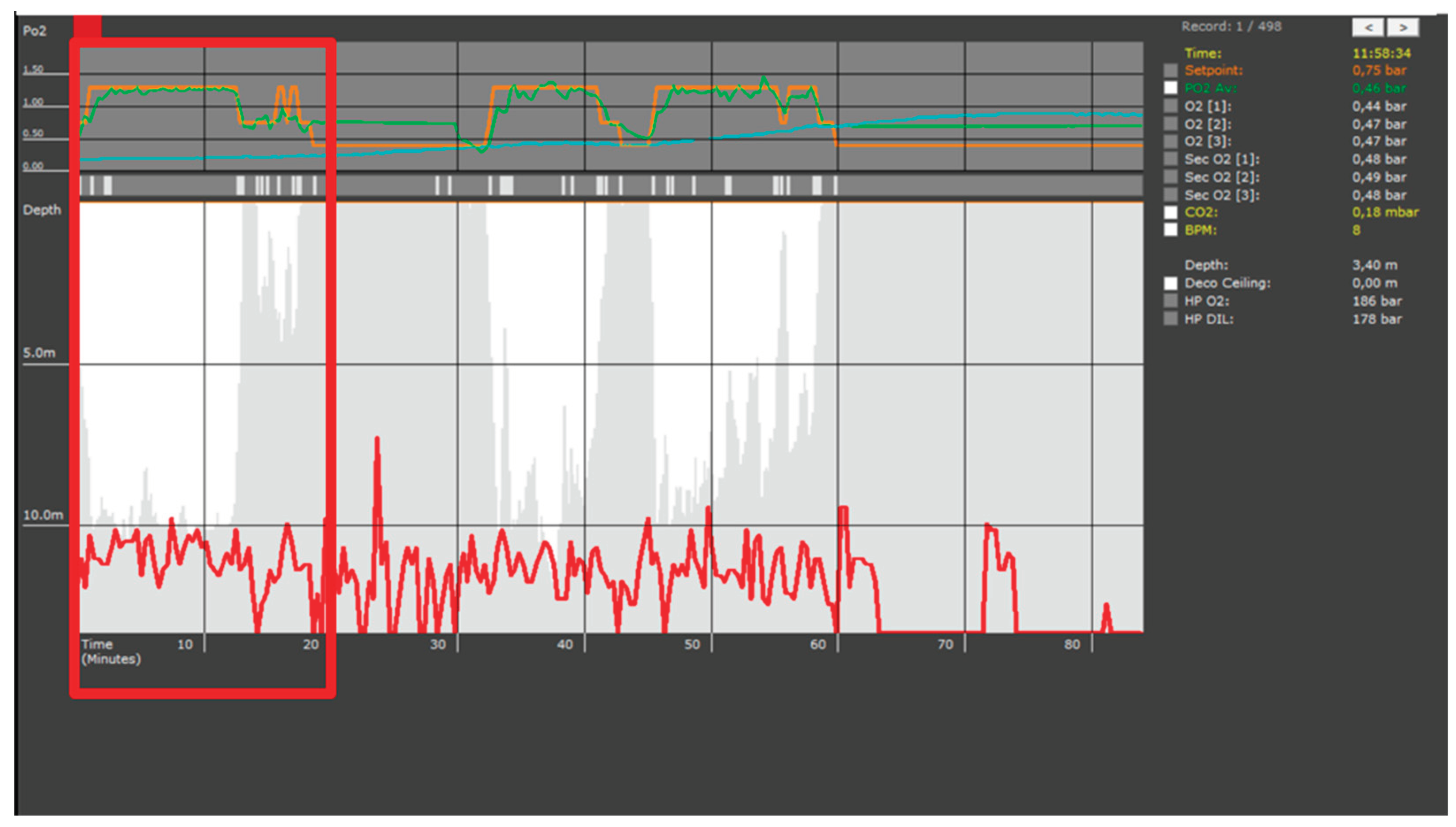

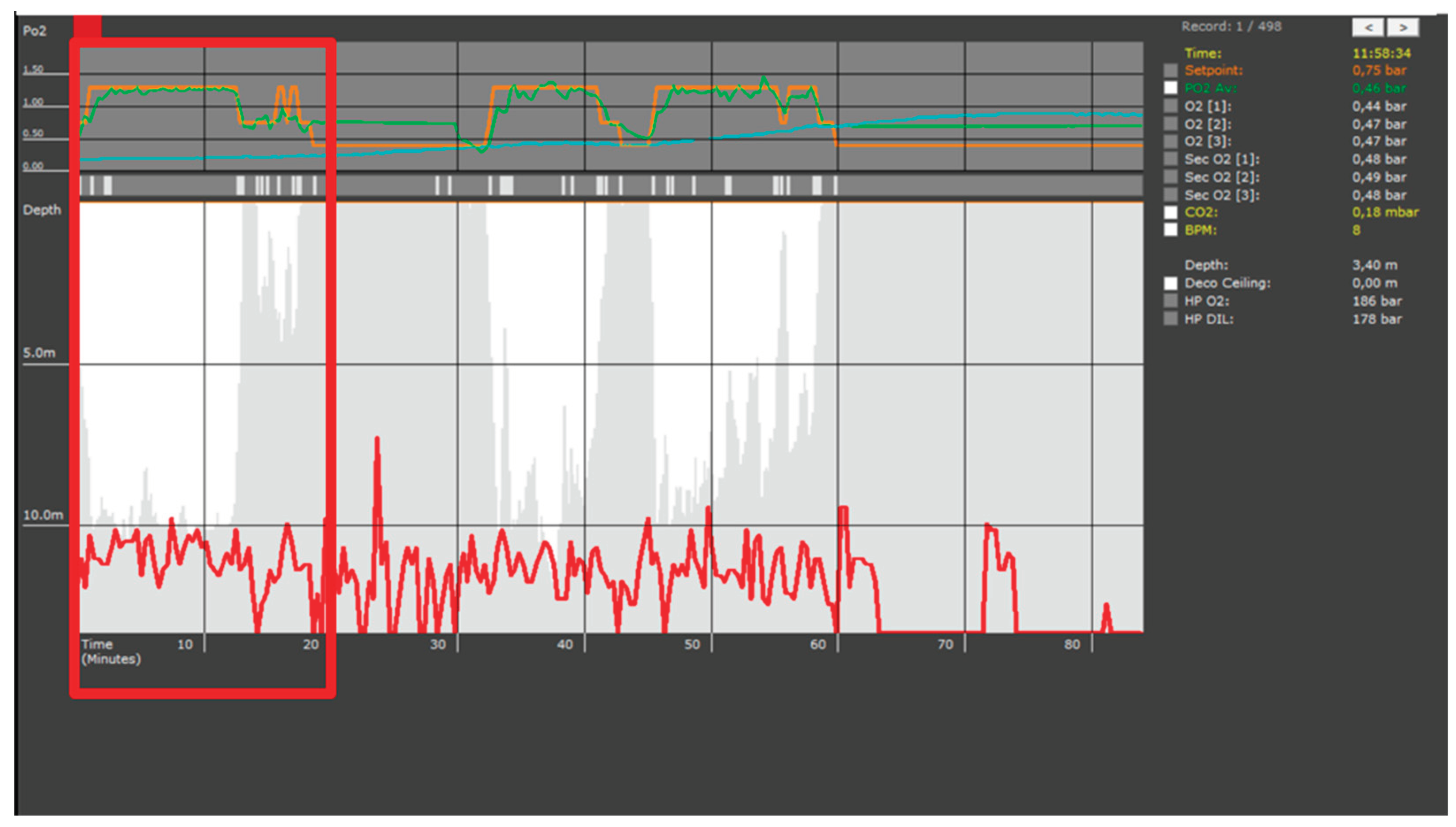

At the time of the dive, environmental conditions were hot, with an air temperature of approximately 35 °C reported on the boat. The diver measured 1.75 meters in height and weighed 80 kg, resulting in a body mass index (BMI) of 26.1 kg/m². He was equipped with a dry suit and an undersuit for thermal protection, as specifically required by the operational protocol of the training exercise conducted that day. The dive was conducted using the MCM100 closed-circuit rebreather, breathing a mixture of oxygen and air (Nitrox) as the diluent gas. The water temperature was approximately 21 °C. The immersion took place in a controlled marine setting, reaching a maximum depth of 12 meters for a total bottom time of 20 minutes, flanked by equal pre- and post-dive rest periods. During the dive, the subject was briefly required to ascend to pass an object to the surface crew. Following this action, he experienced difficulty with ear equalization and, as reflected in the dive profile (see

Figure 1), was unable to descend effectively for the remainder of the session. Physical exertion was minimized throughout the dive to avoid confounding autonomic responses related to effort. Subjective workload was assessed immediately after surfacing using the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) administered via the official mobile application developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The full version of the instrument was employed, including both the 15 pairwise comparisons between workload dimensions to determine individual weightings and the rating scale (0–100) for each dimension. The six domains evaluated were Mental Demand, Physical Demand, Temporal Demand, Performance, Effort, and Frustration. The final workload score was automatically calculated by the app as a weighted average (AW-TLX) of the adjusted domain scores, following the method originally described by Hart and Staveland (1988) [

21]. The pre-dive assessment was not administered, as the subject was a trained military diver routinely exposed to the operational scenario evaluated.

4.2. Data Collection and HRV Analysis

Electrocardiographic (ECG) data were recorded continuously during the three phases (pre-dive, dive, post-dive) using the RootiRx wearable chest sensor, positioned on the thorax and housed in a custom-made waterproof case to ensure data acquisition throughout the underwater session. The RootiRx device has been validated in both clinical and ambulatory environments for high-resolution ECG and HRV monitoring. While underwater use remains relatively novel, the device was enclosed in a custom waterproof case and demonstrated signal reliability throughout immersion. The RootiRx device provided a single-lead ECG trace, from which the RR interval time series was extracted using its proprietary software. Initial HRV analysis was performed within the RootiRx platform, after which the RR data were transferred to Kubios HRV Premium (version 3.5, Kubios Oy, Kuopio, Finland), a validated tool for heart rate variability assessment [

1].

Data segmentation was performed manually based on time intervals (12:15–12:35 for the dive phase), and artifact correction was applied using the medium filter setting. Time-domain, frequency-domain, and nonlinear HRV parameters were then exported in CSV format and imported into IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 23, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for further statistical analysis.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were imported into IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for statistical analysis. Variables were aggregated for each phase (pre, during, post) and tested for normality. Pairwise comparisons between phases were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, given the single-subject design and non-parametric distribution of several variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Graphical representation of results was performed using Matplotlib (Python 3.11) with boxplots highlighting statistically significant differences.

4.4. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As this was a case study on a single military volunteer with no identifiable data and no intervention beyond routine operational training, formal ethical committee approval was not required. Informed consent was obtained from the participant for data analysis and publication of anonymized results.

4.5. Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to institutional restrictions related to military personnel and equipment, full raw ECG data cannot be made publicly available.

4.6. Use of Generative AI

Generative AI was used solely to assist in structuring and editing scientific text. All analytical steps, data handling, and interpretations were conducted manually by the authors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Enrico Moccia; methodology, Enrico Moccia; software, Enrico Moccia; validation, Enrico Moccia and Laura Stefani; formal analysis, Enrico Moccia; investigation, Enrico Moccia and Gualtiero Meloni; data curation, Enrico Moccia; writing—original draft preparation, Enrico Moccia; writing—review and editing, Vincenzo Lionetti, Laura Stefani and Gualtiero Meloni; visualization, Enrico Moccia; supervision, Vincenzo Lionetti, Laura Stefani and Gualtiero Meloni; project administration, Enrico Moccia; critical discussion and scientific contextualization, Laura Stefani and Gualtiero Meloni; support in data organization and review, Fabio Di Pumpo and Lorenzo Rondinini. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the subject involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to individual health data. However, anonymized data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Francesco Schiavone and Dr. Fabio Gobbi for their general support and encouragement throughout the development of this work. They also wish to warmly thank the Italian Navy diver who enthusiastically volunteered for this case study, demonstrating exceptional professionalism and commitment. Special thanks are extended to Eng. Lebrun for his technical support in the deployment and operation of the recording equipment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRV |

Heart Rate Variability |

| SDNN |

Standard Deviation of NN intervals |

| RMSSD |

Root Mean Square of Successive Differences |

| LF |

Low-Frequency Power (typically 0.04–0.15 Hz) |

| HF |

High-Frequency Power (typically 0.15–0.4 Hz) |

| VLF |

Very Low-Frequency Power (typically < 0.04 Hz) |

| LF/HF |

Ratio of Low-Frequency to High-Frequency Power |

| SD1 |

Short-term variability (from Poincaré plot) |

| SD2 |

Long-term variability (from Poincaré plot) |

| SD2/SD1 |

Ratio of SD2 to SD1 (Poincaré asymmetry index) |

| ApEn |

Approximate Entropy |

| SampEn |

Sample Entropy |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| SNS Index |

Sympathetic Nervous System Activity Index |

| PNS Index |

Parasympathetic Nervous System Activity Index |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SCUBA |

Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus |

| CCR |

Closed-Circuit Rebreather |

| MCM100 |

Mixed-Gas Closed-Circuit Military Rebreather 100 |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Pearson correlation matrix of HRV parameters during the underwater phase of the closed-circuit rebreather dive. Strong positive correlations were observed between SDNN, RMSSD, SD1, and SD2, indicating consistent reductions in overall HRV under immersion. The SD2/SD1 ratio also showed significant correlations with both time-domain and nonlinear indices, supporting its role as a marker of autonomic modulation. A nearly perfect inverse correlation was found between SNS and PNS indices (r = –0.990, p < 0.01), highlighting the antagonistic behavior of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity during the dive. Statistically significant correlations (p < 0.01) are marked with **.

Table A1.

Pearson correlation matrix of HRV parameters during the underwater phase of the closed-circuit rebreather dive. Strong positive correlations were observed between SDNN, RMSSD, SD1, and SD2, indicating consistent reductions in overall HRV under immersion. The SD2/SD1 ratio also showed significant correlations with both time-domain and nonlinear indices, supporting its role as a marker of autonomic modulation. A nearly perfect inverse correlation was found between SNS and PNS indices (r = –0.990, p < 0.01), highlighting the antagonistic behavior of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity during the dive. Statistically significant correlations (p < 0.01) are marked with **.

| Correlations |

SDNN (ms) dive |

RMSSD (ms) dive |

PNS INDEX dive |

SNS INDEX dive |

SD1 (ms) dive |

SD2 (ms) dive |

SD2/SD1 dive |

| SDNN (ms) dive |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

,982**

|

-,264 |

,284 |

,982**

|

,998**

|

,910**

|

| Significance (2-tailed) |

|

,000 |

,261 |

,225 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

| N |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| RMSSD (ms) dive |

Pearson Correlation |

,982**

|

1 |

-,171 |

,202 |

1,000**

|

,970**

|

,841**

|

| Significance (2-tailed) |

,000 |

|

,471 |

,393 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

| N |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| PNS INDEX dive |

Pearson Correlation |

-,264 |

-,171 |

1 |

-,990**

|

-,171 |

-,287 |

-,587**

|

| Significance (2-tailed) |

,261 |

,471 |

|

,000 |

,471 |

,220 |

,006 |

| N |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| SNS INDEX dive |

Pearson Correlation |

,284 |

,202 |

-,990**

|

1 |

,202 |

,304 |

,577**

|

| Significance (2-tailed) |

,225 |

,393 |

,000 |

|

,394 |

,193 |

,008 |

| N |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| SD1 (ms) dive |

Pearson Correlation |

,982**

|

1,000**

|

-,171 |

,202 |

1 |

,970**

|

,841**

|

| Significance (2-tailed) |

,000 |

,000 |

,471 |

,394 |

|

,000 |

,000 |

| N |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| SD2 (ms) dive |

Pearson Correlation |

,998**

|

,970**

|

-,287 |

,304 |

,970**

|

1 |

,922**

|

| Significance (2-tailed) |

,000 |

,000 |

,220 |

,193 |

,000 |

|

,000 |

| N |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| SD2/SD1 dive |

Pearson Correlation |

,910**

|

,841**

|

-,587**

|

,577**

|

,841**

|

,922**

|

1 |

| Significance (2-tailed) |

,000 |

,000 |

,006 |

,008 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

| N |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| **. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). |

References

- Shaffer F, Ginsberg JP. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front Public Heal. 2017;5(September):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Billman, GE. Heart rate variability - A historical perspective. Front Physiol. 2011;2 NOV(November):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer F, McCraty R, Zerr CL. A healthy heart is not a metronome: an integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Front Psychol. 2014;5(September):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Lindholm P, Lundgren CEG. The physiology and pathophysiology of human breath-hold diving. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(1):284–92. [CrossRef]

- Malinowski KS, Wierzba TH, Neary JP, Winklewski PJ, Wszędybył-Winklewska M. Heart Rate Variability at Rest Predicts Heart Response to Simulated Diving. Biology (Basel). 2023;12(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Perini R, Veicsteinas A. Heart rate variability and autonomic activity at rest and during exercise in various physiological conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol [Internet]. 2003;90(3):317–25. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Dugrenot E, Balestra C, Gouin E, L’Her E, Guerrero F. Physiological effects of mixed-gas deep sea dives using a closed-circuit rebreather: a field pilot study. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2021 Dec;121(12):3323–31. [CrossRef]

- Vulić M, Milovanovic B, Obad A, Glavaš D, Glavicic I, Zubac D, et al. Depth of SCUBA Diving Affects Cardiac Autonomic Nervous System. Pathophysiology. 2024;31(2):183–9. [CrossRef]

- Lafère P, Lambrechts K, Germonpré P, Balestra A, Germonpré FL, Marroni A, et al. Heart Rate Variability During a Standard Dive: A Role for Inspired Oxygen Pressure? Front Physiol. 2021;12(July). [CrossRef]

- Bosco G, Rizzato A, Moon RE, Camporesi EM. Environmental physiology and diving medicine. Front Psychol. 2018;9(FEB):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Coca MD, Hernando A, Lozano MT, Bolea J, Izquierdo D, Sánchez C. Heart Rate Variability to Automatically Identify Hyperbaric States Considering Respiratory Component. Sensors. 2024;24(2):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Freiberger J, Derrick B, Chon KH, Hossain MB, Posada-Quintero HF, Cooter M, et al. Does Heart Rate Variability Predict Impairment of Operational Performance in Divers? Sensors. 2024;24(23). [CrossRef]

- Hernando A, Posada-Quintero H, Peláez-Coca MD, Gil E, Chon KH. Autonomic Nervous System characterization in hyperbaric environments considering respiratory component and non-linear analysis of Heart Rate Variability. Comput Methods Programs Biomed [Internet]. 2022;214:106527. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169260721006015. 0169.

- Lundell RV, Ojanen T. A systematic review of HRV during diving in very cold water. Int J Circumpolar Health [Internet]. 2023;82(1). Available from. [CrossRef]

- Lundell R, V. , Räisänen-Sokolowski AK, Wuorimaa TK, Ojanen T, Parkkola KI. Diving in the Arctic: Cold Water Immersion’s Effects on Heart Rate Variability in Navy Divers. Front Physiol. 2020;10(January):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zenske A, Koch A, Kähler W, Oellrich K, Pepper C, Muth T, et al. Assessment of a dive incident using heart rate variability. Diving Hyperb Med. 2020;50(2):157–63. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, G. Case report: Biphasic autonomic response in decompression sickness: HRV and sinoatrial findings. Front Physiol. 2025;16(April):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zenske A, Kähler W, Koch A, Oellrich K, Pepper C, Muth T, et al. Does oxygen-enriched air better than normal air improve sympathovagal balance in recreational divers?An open-water study. Res Sports Med. 2020;28(3):397–412. [CrossRef]

- Lundell R, V. , Tuominen L, Ojanen T, Parkkola K, Räisänen-Sokolowski A. Diving Responses in Experienced Rebreather Divers: Short-Term Heart Rate Variability in Cold Water Diving. Front Physiol. 2021;12(April):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez C, Hernando A, Bolea J, Izquierdo D, Rodríguez G, Olea A, et al. Enhancing Safety in Hyperbaric Environments through Analysis of Autonomic Nervous System Responses: A Comparison of Dry and Humid Conditions. Sensors. 2023;23(11):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Hart SG, Staveland LE. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research. Adv Psychol. 1988;52(C):139–83.

Figure 2.

Boxplots of significant heart rate variability (HRV) indices across the three dive phases (pre-dive, dive, and post-dive) in a single-subject design. Each plot displays the distribution of values for a given HRV parameter across phases. Asterisks indicate statistically significant pairwise comparisons as assessed by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns = not significant. Significant changes were observed particularly between the dive and post-dive phases for several indices, including PNS_INDEX, SNS_INDEX, SDNN, RMSSD, SD2, SD2/SD1, DFAa1, and DFAa2, highlighting a dynamic autonomic modulation induced by diving exposure.

Figure 2.

Boxplots of significant heart rate variability (HRV) indices across the three dive phases (pre-dive, dive, and post-dive) in a single-subject design. Each plot displays the distribution of values for a given HRV parameter across phases. Asterisks indicate statistically significant pairwise comparisons as assessed by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns = not significant. Significant changes were observed particularly between the dive and post-dive phases for several indices, including PNS_INDEX, SNS_INDEX, SDNN, RMSSD, SD2, SD2/SD1, DFAa1, and DFAa2, highlighting a dynamic autonomic modulation induced by diving exposure.

Figure 3.

Time-resolved HR and autonomic indices from 24-hour wearable monitoring (RootiRx) with immersion between 12:15 and 12:35. Top panel: mean heart rate (blue line), PNS index (light blue), and SNS index (orange) across the recording period. A transient increase in heart rate is visible during the dive phase, followed by gradual recovery in the post-dive period. Notably, PNS index decreased sharply during immersion and recovered afterward, while SNS index exhibited a modest rise. Bottom panel: time-varying frequency spectrum of HRV (green line: total power). The dive phase corresponds to a transient decrease in HRV power, consistent with autonomic withdrawal. Color bars indicate physical activity and categorized intensity of HR, PNS, and SNS indices. These data provide qualitative confirmation of a biphasic autonomic pattern surrounding the dive.

Figure 3.

Time-resolved HR and autonomic indices from 24-hour wearable monitoring (RootiRx) with immersion between 12:15 and 12:35. Top panel: mean heart rate (blue line), PNS index (light blue), and SNS index (orange) across the recording period. A transient increase in heart rate is visible during the dive phase, followed by gradual recovery in the post-dive period. Notably, PNS index decreased sharply during immersion and recovered afterward, while SNS index exhibited a modest rise. Bottom panel: time-varying frequency spectrum of HRV (green line: total power). The dive phase corresponds to a transient decrease in HRV power, consistent with autonomic withdrawal. Color bars indicate physical activity and categorized intensity of HR, PNS, and SNS indices. These data provide qualitative confirmation of a biphasic autonomic pattern surrounding the dive.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of autonomic nervous system indexes derived from HRV analysis. The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) index (–0.49) reflects reduced vagal modulation, as indicated by decreased Mean RR, RMSSD, and SD1. Conversely, the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) index (0.51) suggests elevated sympathetic tone, evidenced by increased Mean HR, Stress Index, and SD2. The bell curves illustrate each parameter's deviation from normative population values (±2SD), helping visualize the relative autonomic balance in terms of stress and recovery (generated with Kubios HRV Premium software (Kubios Oy, Kuopio, Finland)).

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of autonomic nervous system indexes derived from HRV analysis. The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) index (–0.49) reflects reduced vagal modulation, as indicated by decreased Mean RR, RMSSD, and SD1. Conversely, the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) index (0.51) suggests elevated sympathetic tone, evidenced by increased Mean HR, Stress Index, and SD2. The bell curves illustrate each parameter's deviation from normative population values (±2SD), helping visualize the relative autonomic balance in terms of stress and recovery (generated with Kubios HRV Premium software (Kubios Oy, Kuopio, Finland)).

Figure 4.

Representative ECG tracings recorded via the RootiRx wearable system during the dry phases (pre- and post-dive) of the closed-circuit rebreather dive. The tracing shows isolated premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) occurring in the dry phase (highlighted in red). Notably, no ectopic activity was detected in the ECG recordings obtained during the underwater phase (not shown in this figure ), suggesting a possible modulation of cardiac excitability during immersion.

Figure 4.

Representative ECG tracings recorded via the RootiRx wearable system during the dry phases (pre- and post-dive) of the closed-circuit rebreather dive. The tracing shows isolated premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) occurring in the dry phase (highlighted in red). Notably, no ectopic activity was detected in the ECG recordings obtained during the underwater phase (not shown in this figure ), suggesting a possible modulation of cardiac excitability during immersion.

Figure 6.

Comprehensive heart rate variability (HRV) analysis output including time-domain, frequency-domain, and nonlinear parameters. The histogram shows the distribution of heart rate (HR), while the Poincaré plot and detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) illustrate beat-to-beat variability and long-range correlation patterns, respectively. Key indices such as RMSSD, SDNN, SD1, SD2, and entropy values are reported alongside spectral power in VLF, LF, and HF bands. These combined metrics provide a multifaceted view of autonomic function, capturing both fast vagal activity and slower oscillations related to sympathetic tone and system complexity (generated with Kubios HRV Premium software (Kubios Oy, Kuopio, Finland)).

Figure 6.

Comprehensive heart rate variability (HRV) analysis output including time-domain, frequency-domain, and nonlinear parameters. The histogram shows the distribution of heart rate (HR), while the Poincaré plot and detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) illustrate beat-to-beat variability and long-range correlation patterns, respectively. Key indices such as RMSSD, SDNN, SD1, SD2, and entropy values are reported alongside spectral power in VLF, LF, and HF bands. These combined metrics provide a multifaceted view of autonomic function, capturing both fast vagal activity and slower oscillations related to sympathetic tone and system complexity (generated with Kubios HRV Premium software (Kubios Oy, Kuopio, Finland)).

Figure 1.

Dive profile recorded by the MCM100 closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) computer (AVON Underwater Systems). The red trace represents the diver’s depth (in meters) over time (minutes), with a primary bottom phase between minute 10 and 60, interspersed with brief ascents. The upper panel displays oxygen partial pressure (pO₂) values from both primary (O₂ [

1,

2,

3]) and secondary (Sec O₂ [

1,

2,

3]) electrochemical sensors, showing a maintained setpoint of approximately 0.75 bar. The onboard computer also records carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentration (0.18 mbar) and estimated heart rate (8 bpm at the time of capture). Ambient water temperature during the dive was approximately 21 °C. The shallow ascent and failed re-descent around minute 25 correspond to a momentary interruption in the dive, during which the diver briefly surfaced to assist a teammate, later reporting difficulty in middle ear equalization. The red box highlights the specific dive segment analyzed in this case report. Please note that the full trace also includes data from other operators, as the same MCM100 device is shared and continuously records multiple dives.

Figure 1.

Dive profile recorded by the MCM100 closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) computer (AVON Underwater Systems). The red trace represents the diver’s depth (in meters) over time (minutes), with a primary bottom phase between minute 10 and 60, interspersed with brief ascents. The upper panel displays oxygen partial pressure (pO₂) values from both primary (O₂ [

1,

2,

3]) and secondary (Sec O₂ [

1,

2,

3]) electrochemical sensors, showing a maintained setpoint of approximately 0.75 bar. The onboard computer also records carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentration (0.18 mbar) and estimated heart rate (8 bpm at the time of capture). Ambient water temperature during the dive was approximately 21 °C. The shallow ascent and failed re-descent around minute 25 correspond to a momentary interruption in the dive, during which the diver briefly surfaced to assist a teammate, later reporting difficulty in middle ear equalization. The red box highlights the specific dive segment analyzed in this case report. Please note that the full trace also includes data from other operators, as the same MCM100 device is shared and continuously records multiple dives.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).