Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement Procedure

2.3. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.4. R-Peak Detection and RR Interval Calculation

2.5. Spectral and Complexity Analysis

2.6. Significance Analysis

3. Results

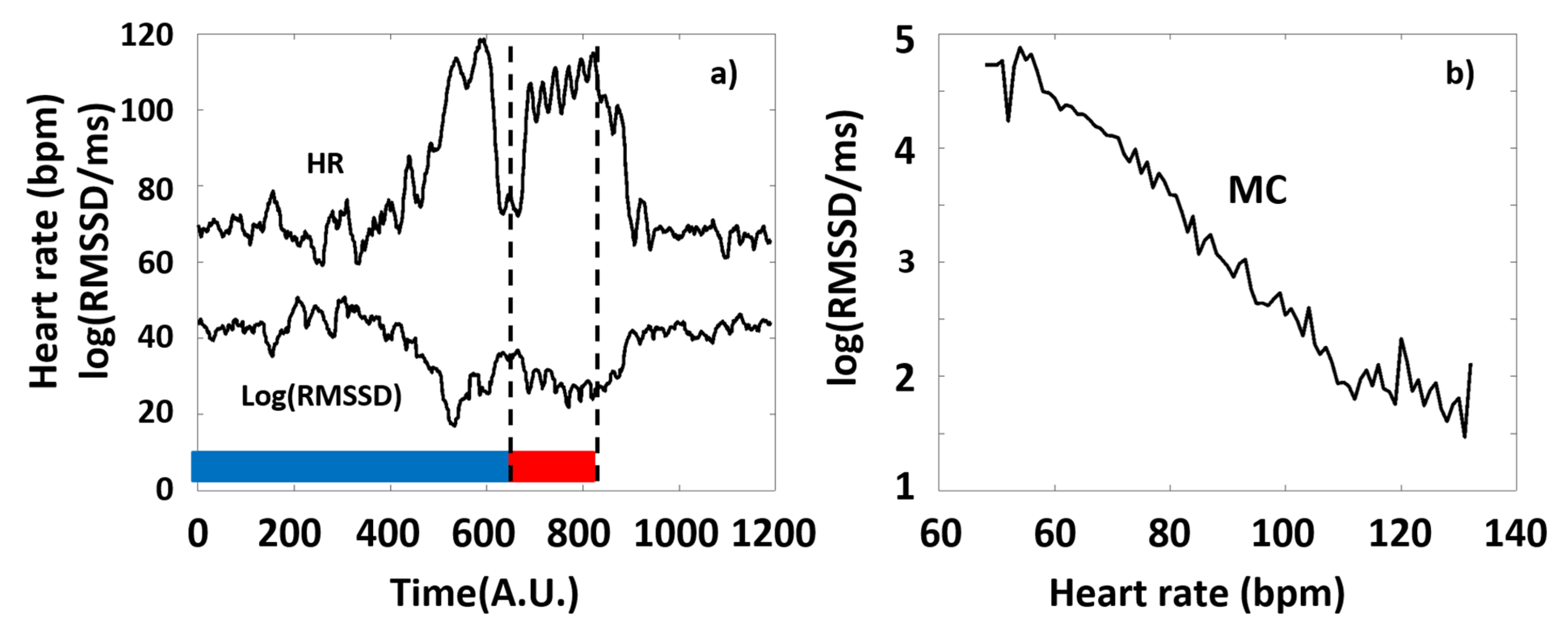

3.1. The HR-Dependence Approach

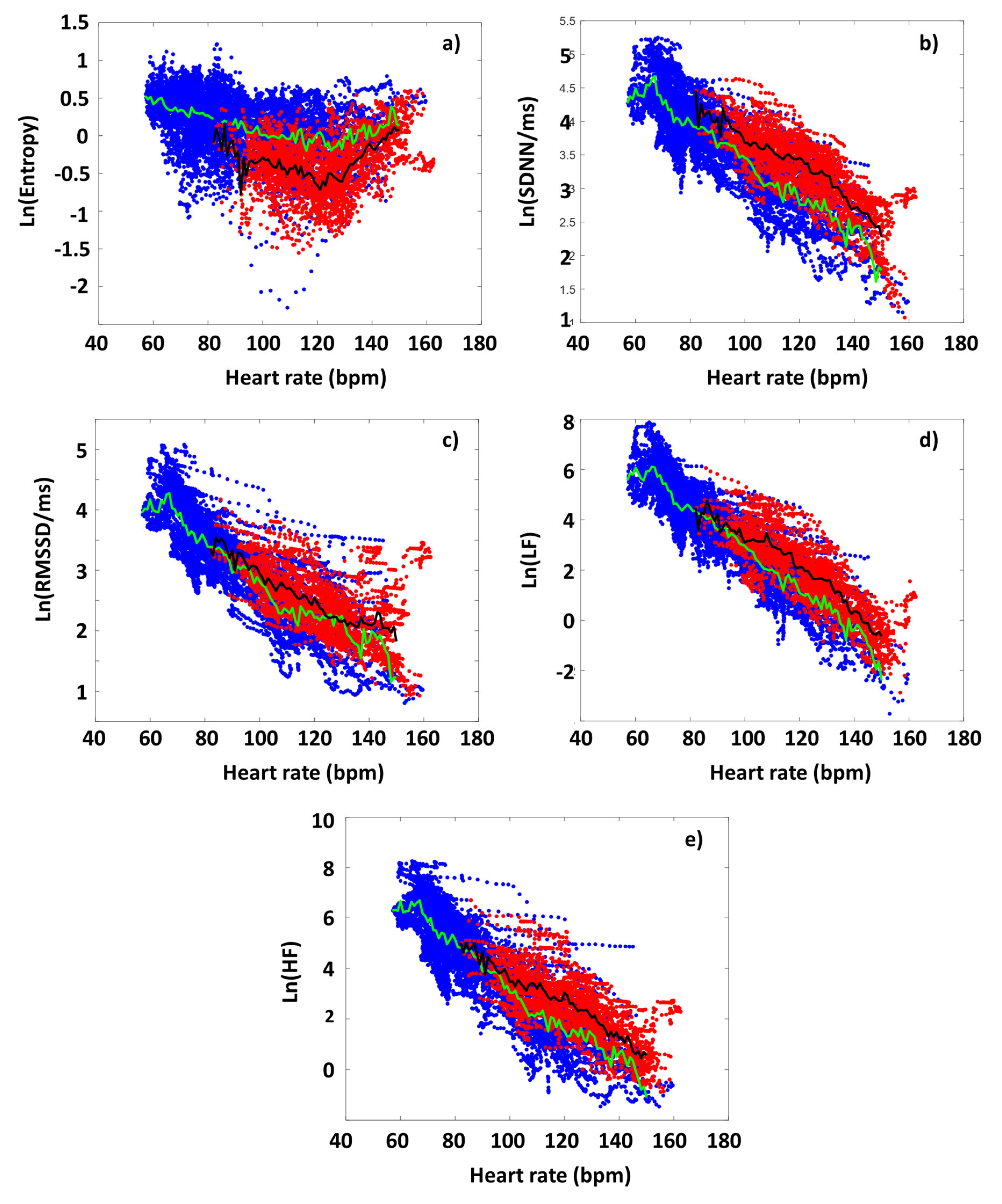

3.2. The Effect of Exercise on the HRV Parameters of the Athletes

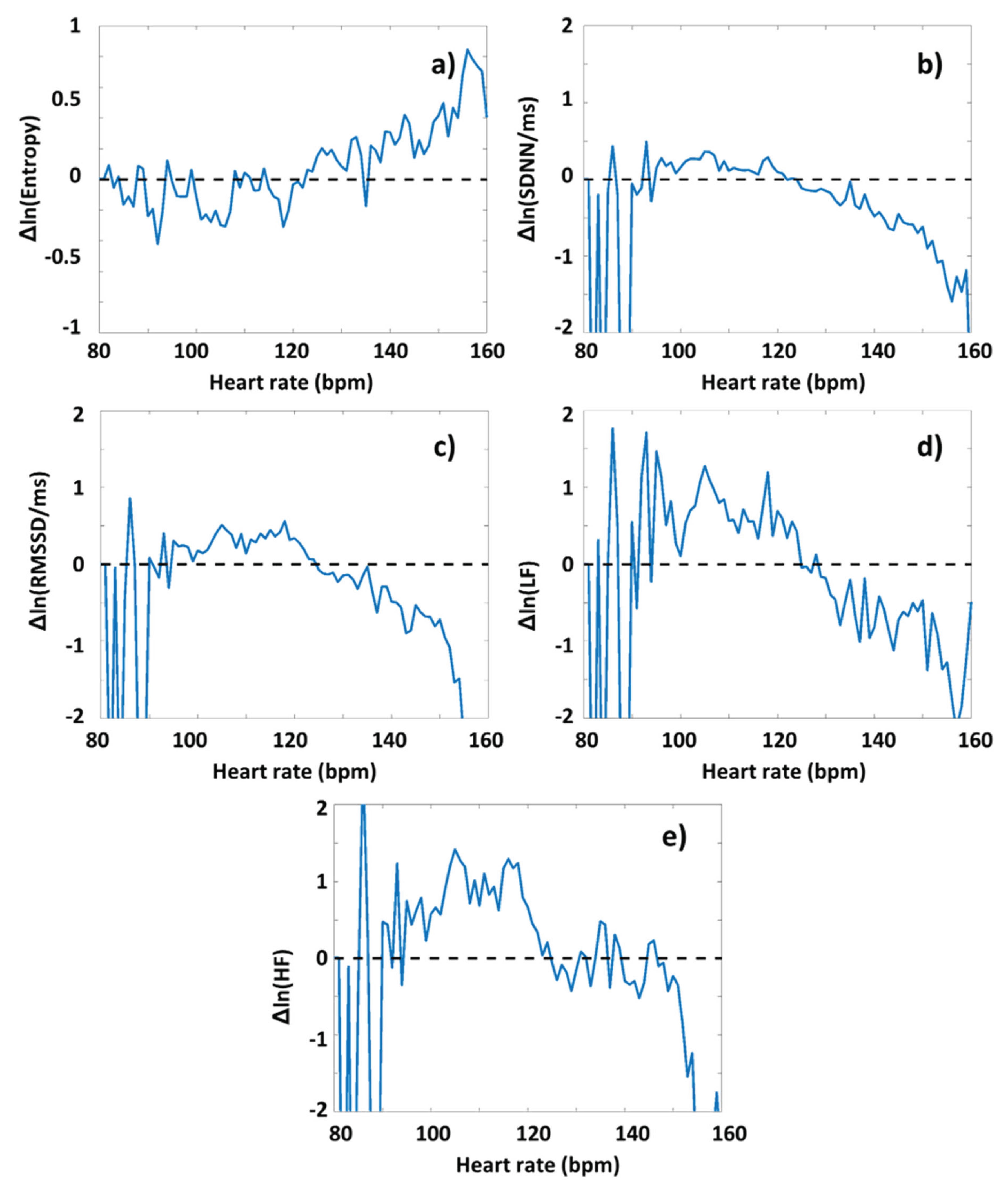

3.3. DOMS-Related Differences in Typical HRV Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| ASR | Acute stress response |

| BRC | Basic-rest-activity-cycle |

| CON | Concentric contraction |

| DAR | Defensive arousal response |

| DOMS | Delayed onset muscle soreness |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglion |

| ECC | Eccentric contraction |

| GAG | glycosaminoglycan |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HRV | Heart rate variability |

| Hsp70 | Heat shock protein 70 |

| LF | Low frequency |

| MC | Master curve |

| PES | Peripheral electromagnetic stimulation |

| REM | Rapid eye movement |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SampEn | Sample entropy |

| SAN | Sinoatrial node |

| SGB | Stellate ganglion block |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| TES | Transcranial electromagnetic stimulation |

| VAS | Visual analogue scale |

| WDR | Wide dynamic range |

References

- Hough, T. Ergographic Studies in Muscular Fatigue and Soreness. J Boston Soc Med Sci 1900, 5, 81-92.

- Cheung, K.; Hume, P.; Maxwell, L. Delayed onset muscle soreness : treatment strategies and performance factors. Sports Med 2003, 33, 145-164. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Nosaka, K.; Braun, B. Muscle function after exercise-induced muscle damage and rapid adaptation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1992, 24, 512-520.

- Mizumura, K.; Taguchi, T. Delayed onset muscle soreness: Involvement of neurotrophic factors. J Physiol Sci 2016, 66, 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.P.; Clarkson, P.M. Exercise-induced muscle pain, soreness, and cramps. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1994, 34, 203-216.

- Forstenpointner, J.; Sendel, M.; Moeller, P.; Reimer, M.; Canaan-Kuhl, S.; Gaedeke, J.; Rehm, S.; Hullemann, P.; Gierthmuhlen, J.; Baron, R. Bridging the Gap Between Vessels and Nerves in Fabry Disease. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 448. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Laursen, P.B.; Ahmaidi, S. Parasympathetic reactivation after repeated sprint exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 293, H133-141. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Peake, J.M.; Buchheit, M. Cardiac parasympathetic reactivation following exercise: implications for training prescription. Sports Med 2013, 43, 1259-1277. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Acquired Piezo2 Channelopathy is One Principal Gateway to Pathophysiology. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 33389. [CrossRef]

- Buzás, A.; Sonkodi, B.; Dér, A. Principal Connection Between Typical Heart-Rate-Variability Parameters as Revealed by a Comparative Analysis of Their Heart-Rate- and Age-Dependence. In Preprints, Preprints: 2025; 10.20944/preprints202505.0641.v2.

- Torres, R.; Vasques, J.; Duarte, J.A.; Cabri, J.M. Knee proprioception after exercise-induced muscle damage. Int J Sports Med 2010, 31, 410-415. [CrossRef]

- Seil, R.; Rupp, S.; Tempelhof, S.; Kohn, D. Sports injuries in team handball. A one-year prospective study of sixteen men's senior teams of a superior nonprofessional level. Am J Sports Med 1998, 26, 681-687. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Acquired Piezo2 Channelopathy is One Principal Gateway to Pathophysiology. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 33389. [CrossRef]

- Sümegi, T.; Langmár, G.; Fülöp, B.; Pozsgai, L.; Mocsai, T.; Tóth, M.; L., R.; B., K.; Sonkodi, B. Delayed-onset muscle soreness mimics a tendency towards a positive romberg test. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square 2025, doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6667123/v1, doi:doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6667123/v1.

- Sonkodi, B.; Radovits, T.; Csulak, E.; Kopper, B.; Sydo, N.; Merkely, B. Orthostasis Is Impaired Due to Fatiguing Intensive Acute Concentric Exercise Succeeded by Isometric Weight-Loaded Wall-Sit in Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness: A Pilot Study. Sports (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B.; Pállinger, É.; Radovits, T.; Csulak, E.; Shenker-Horváth, K.; Kopper, B.; Buzás, E.I.; Sydó, N.; Merkely, B. CD3+/CD56+ NKT-like Cells Show Imbalanced Control Immediately after Exercise in Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 11117.

- Sonkodi, B.; Berkes, I.; Koltai, E. Have We Looked in the Wrong Direction for More Than 100 Years? Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness Is, in Fact, Neural Microdamage Rather Than Muscle Damage. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Acquired Piezo2 Channelopathy is One Principal Gateway to Pathophysiology. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 33389. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L.; Allen, D.G. Early events in stretch-induced muscle damage. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999, 87, 2007-2015. [CrossRef]

- Friden, J.; Seger, J.; Sjostrom, M.; Ekblom, B. Adaptive response in human skeletal muscle subjected to prolonged eccentric training. Int J Sports Med 1983, 4, 177-183. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.G.; Carlsson, L.; Thornell, L.E. Evidence for myofibril remodeling as opposed to myofibril damage in human muscles with DOMS: an ultrastructural and immunoelectron microscopic study. Histochem Cell Biol 2004, 121, 219-227. [CrossRef]

- Mizumura, K.; Taguchi, T. Neurochemical mechanism of muscular pain: Insight from the study on delayed onset muscle soreness. J Physiol Sci 2024, 74, 4. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness and Critical Neural Microdamage-Derived Neuroinflammation. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1207.

- Lee, C.H.; Shin, H.W.; Shin, D.G. Impact of Oxidative Stress on Long-Term Heart Rate Variability: Linear Versus Non-Linear Heart Rate Dynamics. Heart Lung Circ 2020, 29, 1164-1173. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Does Proprioception Involve Synchronization with Theta Rhythms by a Novel Piezo2 Initiated Ultrafast VGLUT2 Signaling? Biophysica 2023, 3, 695-710.

- Sonkodi, B. Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness Begins with a Transient Neural Switch. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 2319.

- Woo, S.H.; Lukacs, V.; de Nooij, J.C.; Zaytseva, D.; Criddle, C.R.; Francisco, A.; Jessell, T.M.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo2 is the principal mechanotransduction channel for proprioception. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 1756-1762. [CrossRef]

- Keriven, H.; Sierra, A.S.; Gonzalez-de-la-Flor, A.; Arrabe, M.G.; de la Plaza San Frutos, M.; Maestro, A.L.; Guillermo Garcia Perez de, S.; Aguilera, J.F.T.; Suarez, V.J.C.; Balmaseda, D.D. Influence of combined transcranial and peripheral electromagnetic stimulation on the autonomous nerve system on delayed onset muscle soreness in young athletes: a randomized clinical trial. J Transl Med 2025, 23, 306. [CrossRef]

- Keriven, H.; Sanchez-Sierra, A.; Gonzalez-de-la-Flor, A.; Garcia-Arrabe, M.; Bravo-Aguilar, M.; de-la-Plaza-San-Frutos, M.; Garcia-Perez-de-Sevilla, G.; Tornero Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suarez, V.J.; Dominguez-Balmaseda, D. Neurophysiological outcomes of combined transcranial and peripheral electromagnetic stimulation on DOMS among young athletes: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0312960. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Duan, Y.; Huang, L.; Ye, T.; Gu, N.; Tan, T.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J. PIEZO2 is the underlying mediator for precise magnetic stimulation of PVN to improve autism-like behavior in mice. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 494. [CrossRef]

- Perini, R.; Veicsteinas, A. Heart rate variability and autonomic activity at rest and during exercise in various physiological conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol 2003, 90, 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Buzás, A.; Sonkodi, B.; Dér, A. The Fundamental Connection Between Typical Time-Domain, Frequency-Domain and Nonlinear Heart-Rate-Variability Parameters as Revealed by a Comparative Analysis of Their Heart-Rate Dependence. In Preprints, Preprints: 2025; 10.20944/preprints202505.0641.v1.

- Sonkodi, B. LF Power of HRV Could Be the Piezo2 Activity Level in Baroreceptors with Some Piezo1 Residual Activity Contribution. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Is acquired Piezo2 channelopathy the critical impairment of the brain axes and dysbiosis? 2025.

- Oosting, J.; Struijker-Boudier, H.A.; Janssen, B.J. Autonomic control of ultradian and circadian rhythms of blood pressure, heart rate, and baroreflex sensitivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 1997, 15, 401-410. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.Z.; Marshall, K.L.; Min, S.; Daou, I.; Chapleau, M.W.; Abboud, F.M.; Liberles, S.D.; Patapoutian, A. PIEZOs mediate neuronal sensing of blood pressure and the baroreceptor reflex. Science 2018, 362, 464-467. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.S.; Allotey, A.A.; Fanelli, R.E.; Satyanarayana, S.B.; Bettadapura, S.S.; Wyatt, C.R.; Landen, J.G.; Nelson, A.C.; Schmitt, E.E.; Bruns, D.R., et al. Diurnal Regulation of Urinary Behavior and Gene Expression in Aged Mice. bioRxiv 2025, 10.1101/2025.03.16.642675. [CrossRef]

- Stupfel, M.; Pavely, A. Ultradian, circahoral and circadian structures in endothermic vertebrates and humans. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol 1990, 96, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Blessing, W.W. Thermoregulation and the ultradian basic rest-activity cycle. Handb Clin Neurol 2018, 156, 367-375. [CrossRef]

- Bijur, P.E.; Silver, W.; Gallagher, E.J. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Acad Emerg Med 2001, 8, 1153-1157. [CrossRef]

- Karcioglu, O.; Topacoglu, H.; Dikme, O.; Dikme, O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Am J Emerg Med 2018, 36, 707-714. [CrossRef]

- Richman, J.S.; Moorman, J.R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000, 278, H2039-2049. [CrossRef]

- Buzas, A.; Horvath, T.; Der, A. A Novel Approach in Heart-Rate-Variability Analysis Based on Modified Poincaré Plots. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 36606–36615, doi:doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3162234.

- Rudics, E.; Buzas, A.; Palfi, A.; Szabo, Z.; Nagy, A.; Hompoth, E.A.; Dombi, J.; Bilicki, V.; Szendi, I.; Der, A. Quantifying Stress and Relaxation: A New Measure of Heart Rate Variability as a Reliable Biomarker. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Monfredi, O.; Lyashkov, A.E.; Johnsen, A.B.; Inada, S.; Schneider, H.; Wang, R.; Nirmalan, M.; Wisloff, U.; Maltsev, V.A.; Lakatta, E.G., et al. Biophysical characterization of the underappreciated and important relationship between heart rate variability and heart rate. Hypertension 2014, 64, 1334-1343. [CrossRef]

- Billman, G.E. The effect of heart rate on the heart rate variability response to autonomic interventions. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 222. [CrossRef]

- Billman, G.E. The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 26. [CrossRef]

- Platisa, M.M.; Gal, V. Reflection of heart rate regulation on linear and nonlinear heart rate variability measures. Physiol Meas 2006, 27, 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Bentho, O.; Park, M.Y.; Sharabi, Y. Low-frequency power of heart rate variability is not a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone but may be a measure of modulation of cardiac autonomic outflows by baroreflexes. Exp Physiol 2011, 96, 1255-1261. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Duan, S.; Peng, C.; Xu, S.; Liu, C.; Li, R.; Deng, Q., et al. Piezo2 expressed in ganglionated plexi: Potential therapeutic target of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2025, 10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.03.1964. [CrossRef]

- Kloth, B.; Mearini, G.; Weinberger, F.; Stenzig, J.; Geertz, B.; Starbatty, J.; Lindner, D.; Schumacher, U.; Reichenspurner, H.; Eschenhagen, T., et al. Piezo2 is not an indispensable mechanosensor in murine cardiomyocytes. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 8193. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Progressive Irreversible Proprioceptive Piezo2 Channelopathy-Induced Lost Forced Peripheral Oscillatory Synchronization to the Hippocampal Oscillator May Explain the Onset of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Pathomechanism. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.M.; Luiz, A.; Tian, N.; Arcangeletti, M.; Iseppon, F.; Sexton, J.E.; Millet, Q.; Caxaria, S.; Ketabi, N.; Celik, P., et al. Gate control of sensory neurotransmission in peripheral ganglia by proprioceptive sensory neurons. Brain 2023, 146, 4033-4039. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, H.; Huo, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, Q.; Ye, Z.; Cao, J.; Wu, S.; Ma, C.; Shang, C. Neural mechanism of trigeminal nerve stimulation recovering defensive arousal responses in traumatic brain injury. Theranostics 2025, 15, 2315-2337. [CrossRef]

- Hedayatpour, N.; Hassanlouei, H.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Kersting, U.G.; Falla, D. Delayed-onset muscle soreness alters the response to postural perturbations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011, 43, 1010-1016. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B.; Hegedűs, Á.; Kopper, B.; Berkes, I. Significantly Delayed Medium-Latency Response of the Stretch Reflex in Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness of the Quadriceps Femoris Muscles Is Indicative of Sensory Neuronal Microdamage. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 2022, 7, 43.

- Hamill, O.P. Arterial pulses link heart-brain oscillations. Science 2024, 383, 482-483. [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.A.; Ogren, J.A.; Abouzeid, C.M.; Macey, P.M.; Sairafian, K.G.; Saharan, P.S.; Thompson, P.M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Hamilton, M.A.; Harper, R.M., et al. Regional hippocampal damage in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17, 494-500. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hamill, O.P. Piezo2-peripheral baroreceptor channel expressed in select neurons of the mouse brain: a putative mechanism for synchronizing neural networks by transducing intracranial pressure pulses. J Integr Neurosci 2021, 20, 825-837. [CrossRef]

- Buzas, A.; Makai, A.; Groma, G.I.; Dancshazy, Z.; Szendi, I.; Kish, L.B.; Santa-Maria, A.R.; Der, A. Hierarchical organization of human physical activity. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5981. [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.R.; Heynen, A.J.; Shuler, M.G.; Bear, M.F. Learning induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Science 2006, 313, 1093-1097. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-T.; Valls, O.T.; Halterman, K. Reentrant Superconducting Phase in Conical-Ferromagnet--Superconductor Nanostructures. Physical Review Letters 2012, 108, 117005. [CrossRef]

- Panna, D.; Balasubramanian, K.; Bouscher, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, P.; Chen, X.; Hayat, A. Nanoscale High-Tc YBCO/GaN Super-Schottky Diode. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 5597. [CrossRef]

- Fogelström, M.; Graf, M.J.; Sidorov, V.A.; Lu, X.; Bauer, E.D.; Thompson, J.D. Two-channel point-contact tunneling theory of superconductors. Physical Review B 2014, 90, 104512. [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.S.; Veras, F.P.; Ferreira, D.W.; Sant'Anna, M.B.; Lollo, P.C.B.; Cunha, T.M.; Galdino, G. Involvement of the Hsp70/TLR4/IL-6 and TNF-alpha pathways in delayed-onset muscle soreness. J Neurochem 2020, 155, 29-44. [CrossRef]

- Treede, R.D. Pain research in 2022: nociceptors and central sensitisation. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 24-25. [CrossRef]

- Brazenor, G.A.; Malham, G.M.; Teddy, P.J. Can Central Sensitization After Injury Persist as an Autonomous Pain Generator? A Comprehensive Search for Evidence. Pain Med 2022, 23, 1283-1298. [CrossRef]

- Szczot, M.; Liljencrantz, J.; Ghitani, N.; Barik, A.; Lam, R.; Thompson, J.H.; Bharucha-Goebel, D.; Saade, D.; Necaise, A.; Donkervoort, S., et al. PIEZO2 mediates injury-induced tactile pain in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R.; Wall, P.D. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 1965, 150, 971-979. [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, J.; Neuberger, E.W.I.; Bormuth, P.; Comes, F.; Schneider, A.; Banzer, W.; Fischer, L.; Simon, P. Investigation of the Sympathetic Regulation in Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness: Results of an RCT. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 697335. [CrossRef]

- Calle, M.C.; Fernandez, M.L. Effects of resistance training on the inflammatory response. Nutr Res Pract 2010, 4, 259-269. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.; Bienso, R.S.; Meinertz, S.; van Hauen, L.; Rasmussen, S.M.; Gliemann, L.; Plomgaard, P.; Pilegaard, H. Impact of training status on LPS-induced acute inflammation in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015, 118, 818-829. [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. The Physiology and Pathology of Exposure to Stress: A Treatise Based on the Concepts of the General-adaptation-syndrome and the Diseases of Adaptation.-Supplement. Annual Report on Stress; Acta: 1951.

- Sonkodi, B. Commentary: Effects of combined treatment with transcranial and peripheral electromagnetic stimulation on performance and pain recovery from delayed onset muscle soreness induced by eccentric exercise in young athletes. A randomized clinical trial. Frontiers in Physiology 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Khataei, T.; Benson, C.J. ASIC3 plays a protective role in delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) through muscle acid sensation during exercise. Front Pain Res (Lausanne) 2023, 4, 1215197. [CrossRef]

- Zechini, L.; Camilleri-Brennan, J.; Walsh, J.; Beaven, R.; Moran, O.; Hartley, P.S.; Diaz, M.; Denholm, B. Piezo buffers mechanical stress via modulation of intracellular Ca(2+) handling in the Drosophila heart. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 1003999. [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Cai, Z.; Sen, P.; van Uden, D.; van de Kamp, E.; Thuillet, R.; Tu, L.; Guignabert, C.; Boomars, K.; Van der Heiden, K., et al. Loss of lung microvascular endothelial Piezo2 expression impairs NO synthesis, induces EndMT, and is associated with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2022, 323, H958-H974. [CrossRef]

- Aon, M.A.; Cortassa, S.; O'Rourke, B. Mitochondrial oscillations in physiology and pathophysiology. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008, 641, 98-117. [CrossRef]

- Close, G.L.; Ashton, T.; Cable, T.; Doran, D.; Noyes, C.; McArdle, F.; MacLaren, D.P. Effects of dietary carbohydrate on delayed onset muscle soreness and reactive oxygen species after contraction induced muscle damage. Br J Sports Med 2005, 39, 948-953. [CrossRef]

- Knapp, L.T.; Klann, E. Role of reactive oxygen species in hippocampal long-term potentiation: contributory or inhibitory? J Neurosci Res 2002, 70, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, F.; Klann, E. Reactive oxygen species and synaptic plasticity in the aging hippocampus. Ageing Res Rev 2004, 3, 431-443. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.; Zweier, J.L. Cardiac mitochondria and reactive oxygen species generation. Circ Res 2014, 114, 524-537. [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, Z.A. An attempt at a rational classification of theories of ageing. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 1990, 65, 375-398. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.P., Jr.; Onyango, I.G. Energy, Entropy and Quantum Tunneling of Protons and Electrons in Brain Mitochondria: Relation to Mitochondrial Impairment in Aging-Related Human Brain Diseases and Therapeutic Measures. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Chenna, S.; Koopman, W.J.H.; Prehn, J.H.M.; Connolly, N.M.C. Mechanisms and mathematical modeling of ROS production by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2022, 323, C69-C83. [CrossRef]

- Keriven, H.; Sanchez Sierra, A.; Gonzalez de-la-Flor, A.; Garcia-Arrabe, M.; Bravo-Aguilar, M.; de la Plaza San Frutos, M.; Garcia-Perez-de-Sevilla, G.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suarez, V.J.; Dominguez-Balmaseda, D. Effects of combined treatment with transcranial and peripheral electromagnetic stimulation on performance and pain recovery from delayed onset muscle soreness induced by eccentric exercise in young athletes. A randomized clinical trial. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1267315. [CrossRef]

- Keriven, H.; Sanchez-Sierra, A.; Minambres-Martin, D.; Gonzalez de la Flor, A.; Garcia-Perez-de-Sevilla, G.; Dominguez-Balmaseda, D. Effects of peripheral electromagnetic stimulation after an eccentric exercise-induced delayed-onset muscle soreness protocol in professional soccer players: a randomized controlled trial. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1206293. [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.P.; Bandeira, J.P.; Perez Chumbiauca, C.N.; Lahiri, D.K.; Morisaki, J.; Rizkalla, M. Multidimensional insights into the repeated electromagnetic field stimulation and biosystems interaction in aging and age-related diseases. J Biomed Sci 2022, 29, 39. [CrossRef]

- Agmon, N. The Grotthuss mechanism. Chemical Physics Letters 1995, 244, 456-462. [CrossRef]

- Fukami, Y. Studies of capsule and capsular space of cat muscle spindles. J Physiol 1986, 376, 281-297. [CrossRef]

- Dér, A.; Kelemen, L.; Fábián, L.; Taneva, S.G.; Fodor, E.; Páli, T.; Cupane, A.; Cacace, M.G.; Ramsden, J.J. Interfacial Water Structure Controls Protein Conformation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2007, 111, 5344-5350. [CrossRef]

- Golaraei, A.; Mirsanaye, K.; Ro, Y.; Krouglov, S.; Akens, M.K.; Wilson, B.C.; Barzda, V. Collagen chirality and three-dimensional orientation studied with polarimetric second-harmonic generation microscopy. Journal of Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800241. [CrossRef]

- Banks, R.W.; Ellaway, P.H.; Prochazka, A.; Proske, U. Secondary endings of muscle spindles: Structure, reflex action, role in motor control and proprioception. Exp Physiol 2021, 106, 2339-2366. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.K.; Rothstein, J.M.; Mayhew, T.P.; Lamb, R.L. Exercise-induced muscle soreness after concentric and eccentric isokinetic contractions. Phys Ther 1991, 71, 505-513. [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, K.; Clarkson, P.M.; McGuiggin, M.E.; Byrne, J.M. Time course of muscle adaptation after high force eccentric exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1991, 63, 70-76. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).