Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. WGS

2.3. Classification/Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Mutations

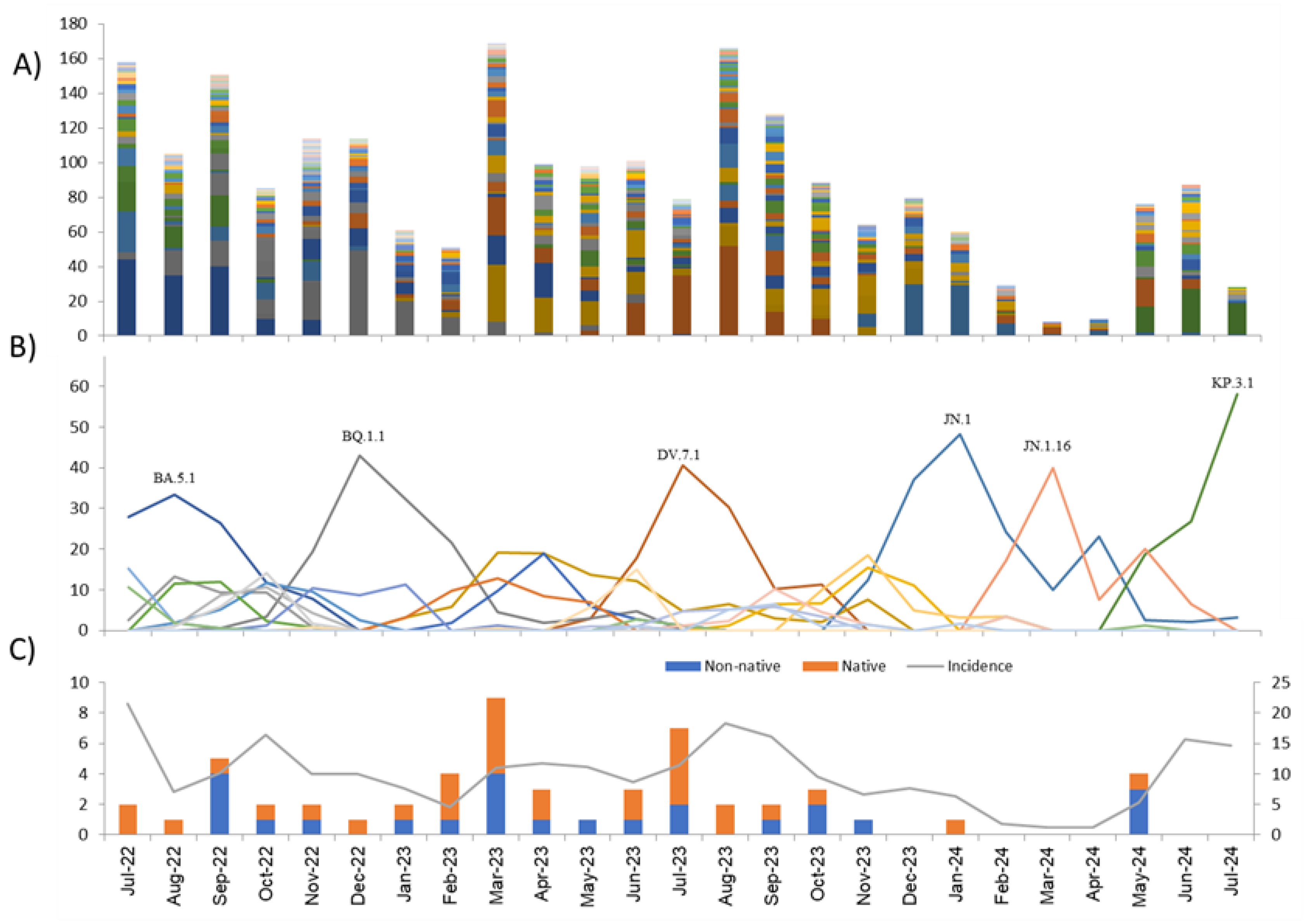

3.2. Lineages

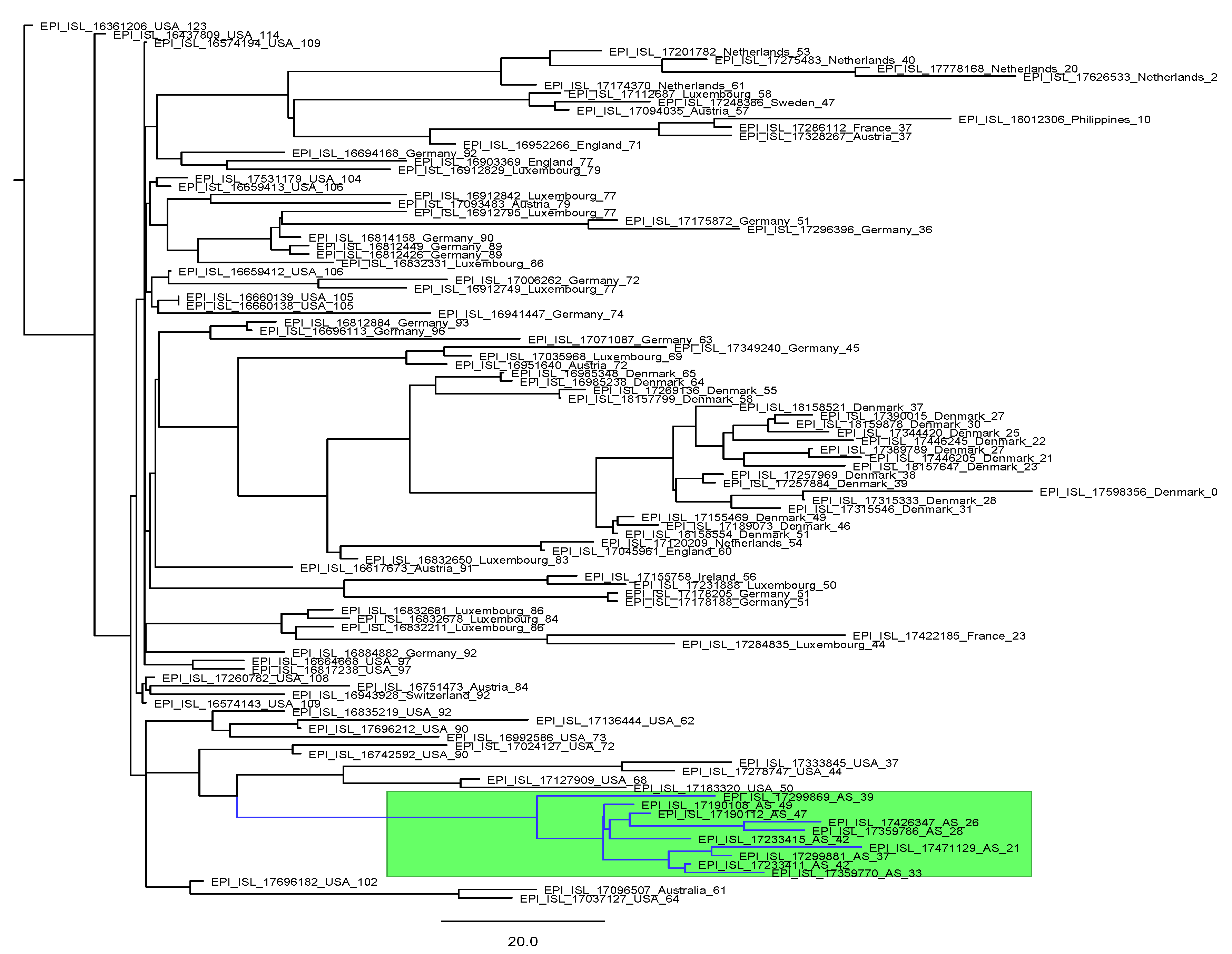

3.3. Variants of Interest

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, C.-M.; Qin, X.-R.; Yan, L.-N.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, X.-J. Global trends in COVID-19. Infect. Med. 2022, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Sun, Y.; Xu, H.; Ye, Q. The emergence and epidemic characteristics of the highly mutated SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 2376–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino, A.; Cardoso, M.A.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Gonçalves, H.M.R. Omicron—The new SARS-CoV-2 challenge? Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Alba JM, Rojo-Alba S, Perez-Martinez Z, Boga JA, Alvarez-Arguelles ME, Gomez J, Herrero P, Costales I, Alba LM, Martin-Rodriguez G, Campo R, Castelló-Abietar C, Sandoval M, Abreu-Salinas F, Coto E, Rodriguez M, Rubianes P, Sanchez ML, Vazquez F, Antuña L, Álvarez V, Melón García S. Monitoring and tracking the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Asturias, Spain. Access Microbiol. 2023 Sep 27;5(9):000573.v4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba JMG, Pérez-Martínez Z, Boga JA, Rojo-Alba S, de Oña JG, Alvarez-Argüelles ME, Rodríguez GM, Gonzalez IC, González IH, Coto E, García SM. Emergence of New SARS-CoV2 Omicron Variants after the Change of Surveillance and Control Strategy. Microorganisms. 2022 Sep 30;10(10):1954. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Salud Publica. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/alertasEmergenciasSanitarias/alertasActuales/nCov/variantesSARS-COV-2/home.htm (accessed on 1 July 2024 ).

- Peck, K.M. Laurin A.S. Complexities of viral mutation rates. J. Virol. 2018;92(14):1031–1037. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Salud Publica. Available online https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Nueva_estrategia_vigilancia_y_control.pdf.

- Colson, P. Bader, W., Fantini, J., Dudouet, P., Levasseur, A., Pontarotti, P., et al. (2023). From viral democratic genomes to viral wild bunch of quasispecies. J. Med. Virol. 95:e29209. [CrossRef]

- Messali, S. Rondina, A., Giovanetti, M., Bonfanti, C., Ciccozzi, M., Caruso, A., et al. (2023). Traceability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission through quasispecies analysis. J. Med. Virol. 95:e28848. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Is SARS-CoV-2 facing constraints in its adaptive evolution? Biomol Biomed. 2025 Jun 9. [CrossRef]

- Bloom JD, Neher RA. Fitness effects of mutations to SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Virus Evol. 2023 Sep18;9(2):vead055. Erratum in: Virus Evol. 2024 Mar 26;10(1):veae026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, AK. Progressive Evolutionary Dynamics of Gene-Specific ? Led to the Emergence of Novel SARS -CoV-2 Strains Having Super-Infectivity and Virulence with Vaccine Neutralization. Int J Mol Sci.2024 Jun 7;25(12):6306. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emam M, Oweda M, Antunes A et al. Positive selection as a key player for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity: Insights into ORF1ab, S and E genes. Virus Res. 2021 Sep;302:198472. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocherie T, Zafilaza K, Leducq V et al. Epidemiology and Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern: The Impacts of the Spike Mutations. Microorganisms. 2022 Dec 22;11(1):30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao Y, Wang J, Jian F, Xiao T, Song W, Yisimayi A, Huang W, Li Q, Wang P, An R, Wang J, Wang Y, Niu X, Yang S, Liang H, Sun H, Li T, Yu Y, Cui Q, Liu S, Yang X, Du S, Zhang Z, Hao X, Shao F, Jin R, Wang X, Xiao J, Wang Y, Xie XS. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2022 Feb;602(7898):657-663. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang S, Yu Y, Jian F, Song W, Yisimayi A, Chen X, Xu Y, Wang P, Wang J, Yu L, Niu X, Wang J, Xiao T, An R, Wang Y, Gu Q, Shao F, Jin R, Shen Z, Wang Y, Cao Y. Antigenicity and infectivity characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Nov;23(11):e457-e459. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett CT, Neal HE, Edmonds K, Moncman CL, Thompson R, Branttie JM, Boggs KB, Wu CY, Leung DW, Dutch RE. Effect of clinical isolate or cleavage site mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on protein stability, cleavage, and cell-cell fusion. J Biol Chem. 2021 Jul;297(1):100902. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandi M, Shafaati M, Kalantar-Neyestanaki D, Pourghadamyari H, Fani M, Soltani S, Kaleji H, Abbasi S. The role of SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins in immune evasion. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Dec;156:113889. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Hou P, Ma W, Wang X, Wang H, Yu Z, Chang H, Wang T, Jin S, Wang X, Wang W, Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Xu C, Ma X, Gao Y, He H. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 suppresses the antiviral innate immune response by degrading MAVS through mitophagy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022 Jan;19(1):67-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L. R. and Perlman, S. (2022). Immune dysregulation and immunopathology induced by SARS-CoV -2 and related coronaviruses—are we our own worst enemy? Nat. Rev. Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Cornillez-Ty CT, Liao L, Yates JR 3rd, Kuhn P, Buchmeier MJ. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 2 interacts with a host protein complex involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and intracellular signaling. J Virol. 2009 Oct;83(19):10314-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Kusov, Y.; Hilgenfeld, R. Nsp3 of coronaviruses: Structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antivir. Res. 2018, 149, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustaqil M, Ollivier E, Chiu HP, Van Tol S, Rudolffi-Soto P, Stevens C, Bhumkar A, Hunter DJB, Freiberg AN, Jacques D, Lee B, Sierecki E, Gambin Y. SARS-CoV-2 proteases PLpro and 3CLpro cleave IRF3 and critical modulators of inflammatory pathways (NLRP12 and TAB1): implications for disease presentation across species. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021 Dec;10(1):178-195. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohari K, Kazemnejad A, Sheidaei A, Hajari S. Clustering of countries according to the COVID-19incidence and mortality rates. BMC Public Health. (2022)22:632. [CrossRef]

- Darques R, Trottier J, Gaudin R, Ait-Mouheb N. Clustering and mapping the first COVID-19 outbreak in France. BMC Public Health. (2022)22:1279. [CrossRef]

- Arora P, Mrig S, Goldust Y, Kroumpouzos G, Karadağ AS, Rudnicka L, Galadari H, Szepietowski JC, Di Lernia V, Goren A, Kassir M, Goldust M. New Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Crossing Borders Beyond Cities, Nations, and Continents: Impact of International Travel. Balkan Med J. 2021 Jul;38(4):205-211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang L,Ma S, Yu L,WangW, Yin Z.Modeling the global dynamic contagion of COVID-19. Front Public Health. (2022) 9:809987. [CrossRef]

- Findlater A, Bogoch II. Human mobility and the global spread of infectious diseases: a focus on air travel. Trends Parasitol. (2018) 34:772–83. [CrossRef]

- www.who.

- Parsons RJ, Acharya P. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron spike. Cell Rep. 2023 Dec 26;42(12):113444. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed AM, Ciling A, Khalid MM, Sreekumar B, Chen PY, Kumar GR, Silva I, Milbes B, Kojima N, Hess V, Shacreaw M, Lopez L, Brobeck M, Turner F, Spraggon L, Taha TY, Tabata T, Chen IP, Ott M, Doudna JA. Omicron mutations enhance infectivity and reduce antibody neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particles. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2022 Jan 2:2021.12.20.21268048. Update in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Aug 2;119(31):e2200592119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, Hengartner N, Giorgi EE, Bhattacharya T, Foley B, Hastie KM, Parker MD, Partridge DG, Evans CM, Freeman TM, de Silva TI; Sheffield COVID-19 Genomics Group; McDanal C, Perez LG, Tang H, Moon-Walker A, Whelan SP, LaBranche CC, Saphire EO, Montefiori DC. Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell. 2020 Aug 20;182(4):812-827.e19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley PD, Tillett RL, AuCoin DP, Sevinsky JR, Xu Y, Gorzalski A, Pandori M, Buttery E, Hansen H, Picker MA, Rossetto CC, Verma SC. Genomic surveillance of Nevada patients revealed prevalence of unique SARS-CoV-2 variants bearing mutations in the RdRp gene. J Genet Genomics. 2021 Jan 20;48(1):40-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang P, Casner RG, Nair MS, Wang M, Yu J, Cerutti G, Liu L, Kwong PD, Huang Y, Shapiro L, Ho DD. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variant P.1 to antibody neutralization. Cell Host Microbe. 2021 ;29(5):747-751.e4. 12 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami S, Kotaki T, Sakai Y, Okamura S, Torii S, Ono C, Motooka D, Hamajima R, Nouda R, Nurdin JA, Yamasaki M, Kanai Y, Ebina H, Maeda Y, Okamoto T, Tachibana T, Matsuura Y, Kobayashi T. Vero cell-adapted SARS-CoV-2 strain shows increased viral growth through furin-mediated efficient spike cleavage. Microbiol Spectr. 2024 Apr 2;12(4):e0285923. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu P, Evans JP, Kurhade C, Zeng C, Zheng YM, Xu K, Shi PY, Xie X, Liu SL. Determinants and Mechanisms of the Low Fusogenicity and High Dependence on Endosomal Entry of Omicron Subvariants. mBio. 2023 Feb 28;14(1):e0317622. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramoney K, Mtileni N, Giandhari J, Naidoo Y, Ramphal Y, Pillay S, Ramphal U, Maharaj A, Tshiabuila D, Tegally H, Wilkinson E, de Oliveira T, Fielding BC, Treurnicht FK. Molecular Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 during Five COVID-19 Waves and the Significance of Low-Frequency Lineages. Viruses. 2023 ;15(5):1194. 18 May; Erratum in: Viruses. 2023 Jul 04;15(7):1502. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu H, Xing N, Meng K, Fu B, Xue W, Dong P, Tang W, Xiao Y, Liu G, Luo H, Zhu W, Lin X, Meng G, Zhu Z. Nucleocapsid mutations R203K/G204R increase the infectivity, fitness, and virulence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2021 Dec 8;29(12):1788-1801.e6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsuwairi FA, Alsaleh AN, Alsanea MS, Al-Qahtani AA, Obeid D, Almaghrabi RS, Alahideb BM, AlAbdulkareem MA, Mutabagani MS, Althawadi SI, Altamimi SA, Alshukairi AN, Alhamlan FS. Association of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Mutations with Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics during the Delta and Omicron Waves. Microorganisms. 2023 ;11(5):1288. 15 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen A, Zhao H, Myagmarsuren D, Srinivasan S, Wu D, Chen J, Piszczek G, Schuck P. Modulation of biophysical properties of nucleocapsid protein in the mutant spectrum of SARS-CoV-2. Elife. 2024 Jun 28;13:RP94836. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang WT, Huang WH, Liao TL, Hsiao TH, Chuang HN, Liu PY. SARS-CoV-2 E484K Mutation Narrative Review: Epidemiology, Immune Escape, Clinical Implications, and Future Considerations. Infect Drug Resist. 2022 Feb 3;15:373-385. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin X, Sha Z, Trimpert J, Kunec D, Jiang C, Xiong Y, Xu B, Zhu Z, Xue W, Wu H. The NSP4 T492I mutation increases SARS-CoV-2 infectivity by altering non-structural protein cleavage. Cell Host Microbe. 2023 Jul 12;31(7):1170-1184.e7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang Y, Nie Y, PennyM. Transmission dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak and effectiveness of government interventions: a data-driven analysis. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:645–59. [CrossRef]

- Brand SPC, Ojal J, Aziza R, Were V, Okiro EA, Kombe IK, Mburu C, Ogero M, Agweyu A, Warimwe GM, Nyagwange J, Karanja H, Gitonga JN, Mugo D, Uyoga S, Adetifa IMO, Scott JAG, Otieno E, Murunga N, Otiende M, Ochola-Oyier LI, Agoti CN, Githinji G, Kasera K, Amoth P, Mwangangi M, Aman R, Ng'ang'a W, Tsofa B, Bejon P, Keeling MJ, Nokes DJ, Barasa E. COVID-19 transmission dynamics underlying epidemic waves in Kenya. Science. 2021 Nov 19;374(6570):989-994. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principio del formulario.

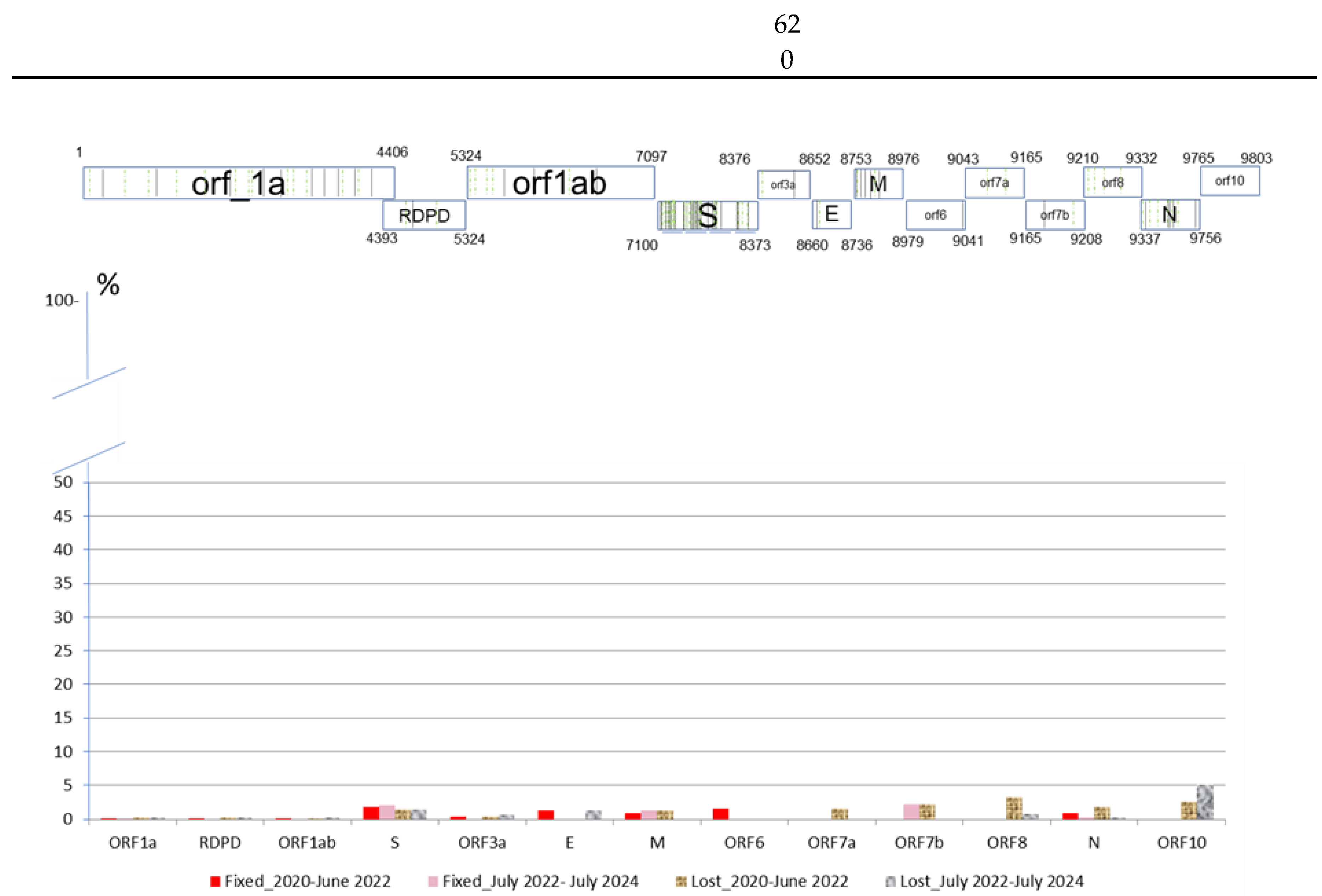

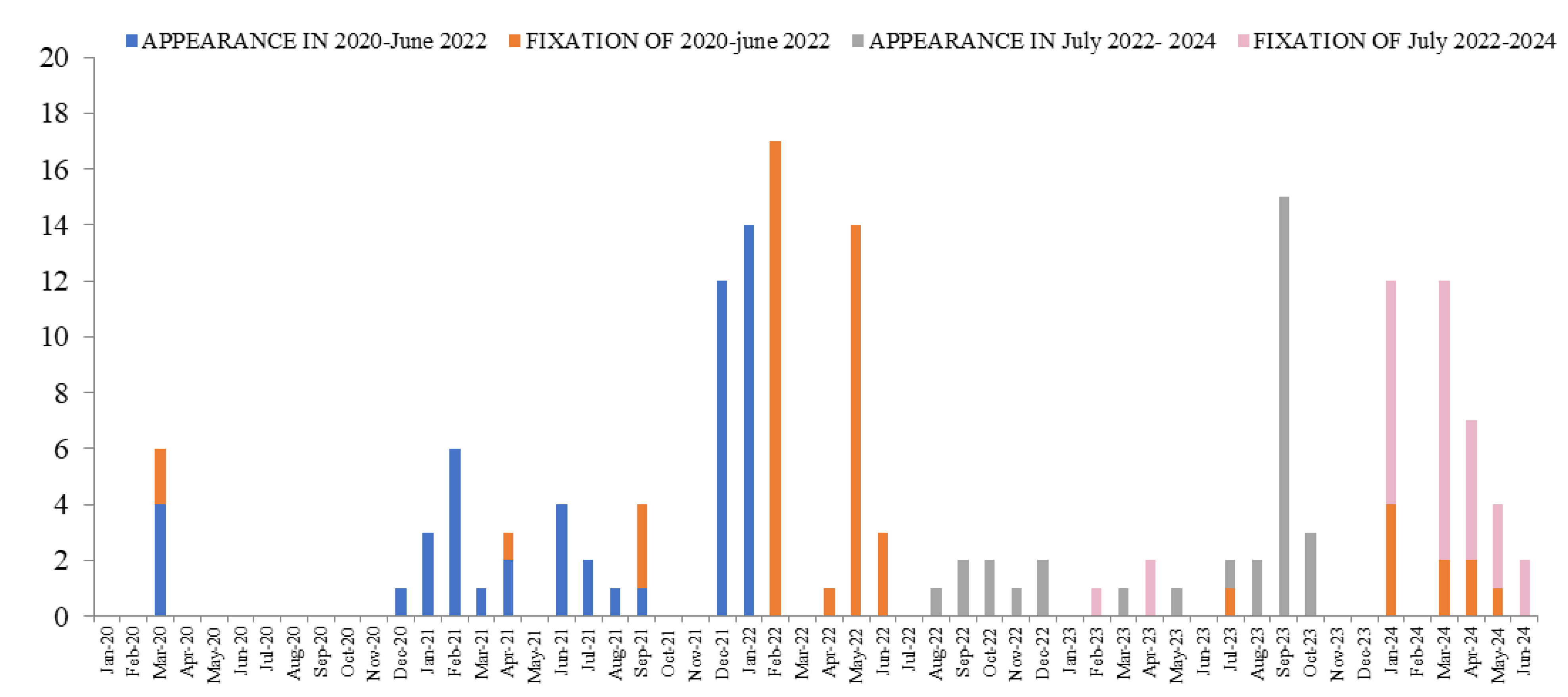

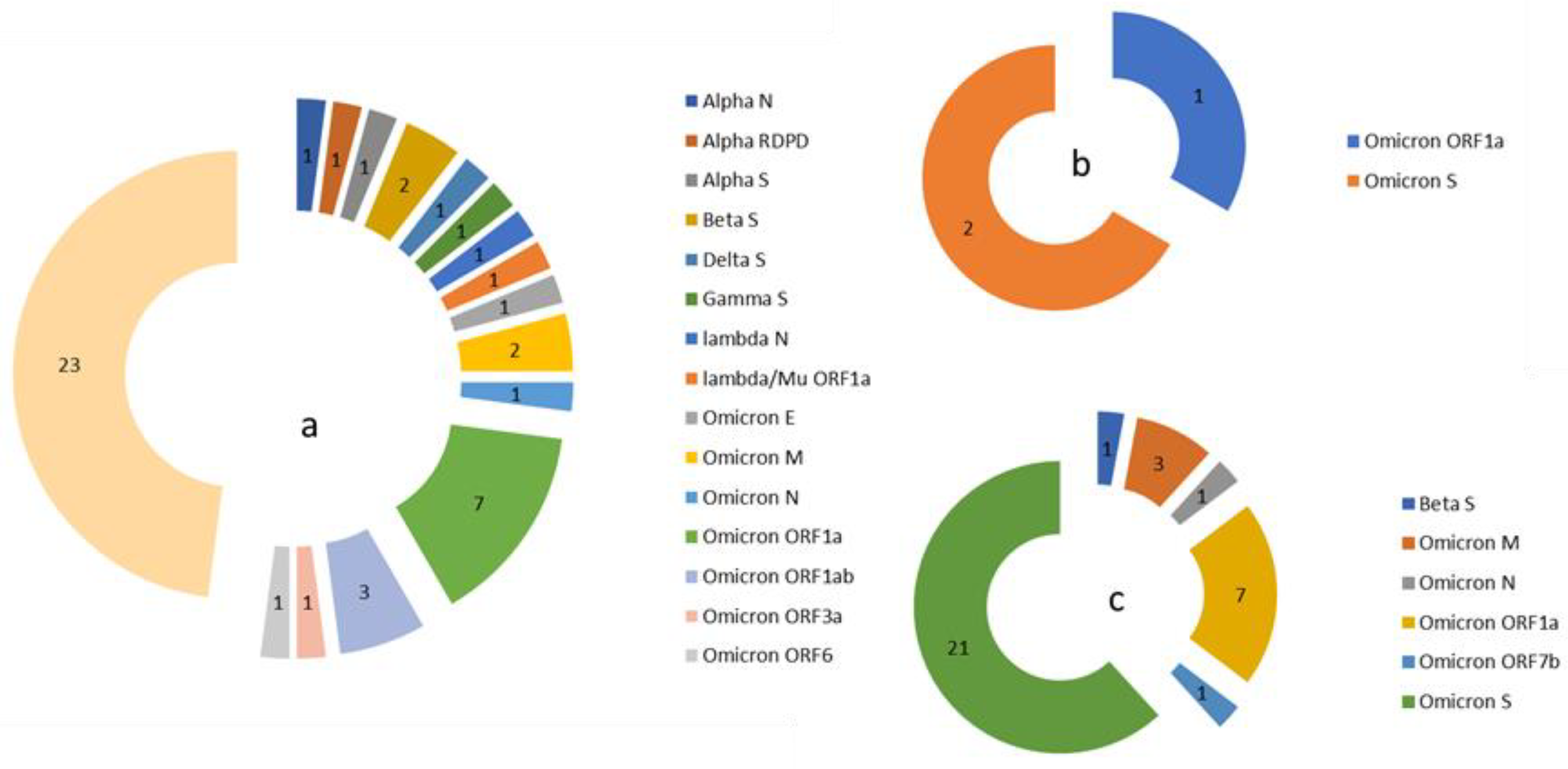

) and lost (

) and lost ( ) in the population in two period analyzed.

) in the population in two period analyzed.

) and lost (

) and lost ( ) in the population in two period analyzed.

) in the population in two period analyzed.

| ORF1a | RDPD | ORF1ab | S | ORF3a | E | M | ORF6 | ORF7a | ORF7b | ORF8 | N | ORF10 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GISAID | 21 | 2 | 6 | 59 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 116 | |

| SPAIN | 29 | 4 | 7 | 82 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 158 |

| ASTURIAS | 31 | 3 | 8 | 82 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 1 | 157 |

| Mutations | ORF1a | RDPD | ORF1ab | S | ORF3a | E | M | ORF6 | ORF7a | ORF7b | ORF8 | N | ORF10 | Total | |

| 2020-22 | Occurred | 21 | 3 | 5 | 47 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 1 | 105 |

| Fixed | 8 | 1 | 3 | 29 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 51 | |||||

|

Days or Mean± CI |

62/124(x4)/217/775 930 | 0 | 62 124 124 |

358±132 (0-1209) |

496 | 372 | 62 62 |

868 | 124/310 403/713961 |

344±94 (0-1209) |

|||||

| 2022-24 | Ocsurred | 20 | 3 | 6 | 47 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 88 | ||

| Fixed | 6 | 21 | 3 | 1 | 31 | ||||||||||

|

Days or Mean± CI |

93/124(x2) 217(x3) | 257±53 (124-527) |

248 278 620 |

217 | 250±46 (93-620) |

||||||||||

| ORF_1a | RDPD | ORF_1ab | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP1 | NSP2 | NSP3 | NSP4 | NSP5 | NSP6 | NSP8 | NSP9 | NSP10 | NSP12 | NSP13 | NSP14 | NSP15 | NSP16 | S | ORF3a | E | ORF7a | ORF8 | N | ORF10 |

| G94C | A357S | D112N | A128V | K90R | F235L | P10S | G38V | T115I | A4774V | V157L | A320T | D36G | K160R | A67V | D155Y | T9V | L5F | D119Y | P151S | I27T |

| P6S | E574D | D1764G | V13I | V35L | L37F | T21I | I4563M | I15T | P205S | P215L | A701V | D27H | Q94L | P38S | ||||||

| V121A | G265S | E119K | M5021V | N71S | A845S | L140F | T28I | |||||||||||||

| G285S | E387D | S4621N | P203L | D253G | M260K | |||||||||||||||

| L24F | I541V | Q22H | D80E | Q185H | ||||||||||||||||

| N254S | M988L | V328F | F456L | Q57H | ||||||||||||||||

| S591I | N1322S | F486V | S171L | |||||||||||||||||

| T103I | N1680K | F59S | T270I | |||||||||||||||||

| P153L | G252V | V273L | ||||||||||||||||||

| Q167R | L249F | |||||||||||||||||||

| R1297G | N354K | |||||||||||||||||||

| S126L | P1263Q | |||||||||||||||||||

| S1428L | Q675H | |||||||||||||||||||

| S454G | T547I | |||||||||||||||||||

| T1203I | T572I | |||||||||||||||||||

| T424N | V1264L | |||||||||||||||||||

| T720I | V445P | |||||||||||||||||||

| T970M | ||||||||||||||||||||

| V1385I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| V1673I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Y1535H | ||||||||||||||||||||

| NVC | N(%Total identified) | First detection date | Last detection date | Time of detection (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frst detected in the world | ||||

| BA.5.2.1 + NSP3_S454G | 6 (43) | 17/09/2022 | 22/10/2022 | 35 |

| BA.5.2.6 + NSP3_M988L | 7 (3) | 22/09/2022 | 06/11/2022 | 45 |

| BF.5 + S_D80E + S_A701V + NSP1_G94C | 8 (62) | 22/09/2022 | 08/11/2022 | 47 |

| BA.5.1 + NSP12_M5021V | 5 (7) | 24/09/2022 | 16/11/2022 | 53 |

| BF.7 + NSP14_P203L | 13 (29) | 19/10/2022 | 07/12/2022 | 49 |

| BQ.1.1.18 + S_T547I | 5 (28) | 16/11/2022 | 11/01/2023 | 56 |

| XBB.1.5 + NSP3_T1203I | 12 (6) | 24/01/2023 | 01/05/2023 | 97 |

| FL.5 + NSP14_Q22H + NSP3_P153L | 6 (2) | 15/02/2023 | 24/05/2023 | 98 |

| XBB.1.5.8 + NSP14_V328F | 10 (10) | 01/03/2023 | 29/03/2023 | 28 |

| BQ.1.18 + NSP14_I15T | 20 (17) | 04/03/2023 | 29/06/2023 | 117 |

| XBB.1.5 + NSP2_S591I + NSP3_N1322S | 12 (1) | 04/03/2023 | 20/08/2023 | 169 |

| XBB.1.5 + NSP5_V35L | 6 (1) | 09/03/2023 | 07/07/2023 | 120 |

| XBB.1.5.71 + NSP1_P6S + ORF3a_Q57H + NSP12_I4563M | 5 (4) | 28/04/2023 | 13/06/2023 | 46 |

| XBB.1.5.71 + NSP1_P6S + NSP12_I4563M | 6 (2) | 12/05/2023 | 03/06/2023 | 22 |

| EG.5.1 + ORF3a_D27H | 5 (1) | 20/06/2023 | 24/08/2023 | 65 |

| XBB.1.16.11 + NSP2_N254S | 6 (1) | 20/07/2023 | 16/10/2023 | 88 |

| DV.7.1 + NSP3_E119K | 6 (18) | 26/07/2023 | 08/09/2023 | 44 |

| EG.5.1.3 + NSP3_I541V | 5 (42) | 05/09/2023 | 14/09/2023 | 9 |

| JD.1.1 + ORF3a_M260K | 5 (2) | 13/10/2023 | 28/11/2023 | 46 |

| JG.3 + ORF3a_S171L | 7 (14) | 27/10/2023 | 04/12/2023 | 38 |

| JN.1.31 + S_T572I | 6 (23) | 29/11/2023 | 13/03/2024 | 105 |

| JN.1.16 + S_A67V + S_L249F + S_V445P | 6 (10) | 07/05/2024 | 26/05/2024 | 19 |

| JN.1.32 + S_F456L | 7 (1) | 12/05/2024 | 06/06/2024 | 25 |

| JN.1.16.1 + NSP3_S1428L + NSP5_K90R + NSP6_L37F + S_F59S | 5 (83) | 13/05/2024 | 19/05/2024 | 6 |

| First detected in Asturias | ||||

| BA.4.6 + NSP2_G265S + NSP3_D112N + ORF7a_Q94L | 7 (100)** | 10/06/2022 | 17/10/2022 | 129 |

| CH.1.1.28 + NSP16_K160R | 14 (100)** | 22/12/2022 | 22/03/2023 | 90 |

| XBB.1.5 + NSP3_T970M + NSP12_A4774V | 6 (100)** | 27/01/2023 | 13/04/2023 | 76 |

| XBB.1.5.77 + S_G252V + NSP2_E574D + ORF7a_L5F + ORF7a_T28I | 6 (100)** | 14/02/2023 | 07/04/2023 | 52 |

| XBB.1.5.1 + NSP15_D36G + NSP3_S126LL + NSP1_V121A + ORF8_P38S | 7 (100)** | 03/04/2023 | 04/05/2023 | 31 |

| XBB.2.3 + E_T9V + NSP3_N1680K + NSP3_Y1535H + ORF10_I27T | 5 (100)** | 16/04/2023 | 11/08/2023 | 117 |

| EG.1.4 + NSP12_S4621N + S_A845S | 6 (100)** | 09/05/2023 | 03/08/2023 | 86 |

| DV.7.1 + NSP3_R1297G + ORF3a_Q185H | 6 (100)** | 21/05/2023 | 31/08/2023 | 102 |

| JG.3 + NSP3_V1385I | 8 (100)** | 04/10/2023 | 22/01/2024 | 110 |

| JN.1.16.2 + S_A67V + S_V445P + S_L249F | 8 (100)** | 24/01/2024 | 25/05/2024 | 122 |

| BQ.1.1.15 + NSP3_T1203I | 6 (55)* | 26/07/2022 | 27/12/2022 | 154 |

| BQ.1.1.66 + NSP3_E387D + NSP9_G38V + NSP10_T115II | 10 (83)* | 23/11/2022 | 15/03/2023 | 112 |

| XBB.1.5.37 + NSP9_T21I | 7 (78)* | 15/12/2022 | 23/04/2023 | 129 |

| XBB.2.3.13 + NSP3_Q167R | 6 (60)* | 28/02/2023 | 31/07/2023 | 153 |

| XBB.2.3.13 + NSP2_A357S + NSP6_F235L + S_A701V | 13 (93)* | 12/03/2023 | 24/04/2023 | 43 |

| XBB.1.5.71 + NSP15_P205S + NSP2_L24F | 5 (83)* | 10/05/2023 | 27/09/2023 | 140 |

| BA.4.1 + NSP13_V157L | 7 (88)* | 09/06/2022 | 15/08/2022 | 67 |

| BE.1 + ORF3a_T270I + ORF3a_V273L | 6 (86)* | 10/07/2022 | 08/09/2022 | 60 |

| BF.7 + NSP4_A128V + S_Q675H + S_P1263Q | 10 (19) | 29/06/2022 | 01/12/2022 | 155 |

| CK.2.1.1 + S_V1264L + ORF8_D119Y | 5 (63) | 03/10/2022 | 21/12/2022 | 79 |

| EL.1 + NSP2_T103I + NSP3_T720I | 35 (90) | 16/11/2022 | 19/05/2023 | 184 |

| EF.1.2 + S_D253G + NSP4_V13I + ORF3a_D155Y | 10 (67) | 20/12/2022 | 16/03/2023 | 86 |

| XBB.2.3.13 + NSP2_A357S | 12 (16) | 05/02/2023 | 09/06/2023 | 124 |

| EL.1 + NSP14_A320T + NSP2_G265S + NSP3_T970M | 6 (75) | 14/02/2023 | 19/05/2023 | 94 |

| DV.7.1 + NSP14_N71S | 8 (57) | 28/04/2023 | 02/09/2023 | 127 |

| XBB.1.5 + NSP3_V1673I + ORF3a_L140F | 13 (81) | 08/06/2023 | 19/09/2023 | 103 |

| EG.6.1 + NSP3_S1428L | 11 (79) | 16/06/2023 | 02/10/2023 | 108 |

| DV.7.1 + NSP8_P10S + NSP3_D1764G | 5 (16) | 23/06/2023 | 10/09/2023 | 79 |

| EG.5.1.5 + S_N354K + N_P151S | 12 (46) | 13/07/2023 | 26/08/2023 | 44 |

| HV.1 + NSP14_P203L | 6 (29) | 05/08/2023 | 13/10/2023 | 69 |

| JN.1 + S_F486V | 6 (75) | 29/10/2023 | 25/01/2024 | 88 |

| Variant Mutation |

Alpha | Beta | Gamma | Delta | Zeta | Eta | Theta | Iota | Kappa | Lambda | Mu | Epsilon | Omicron |

| E_T9I | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| M_A63T | X | ||||||||||||

| N_G204R | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| N_P13L | X | X | |||||||||||

| N_R203K | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| ORF1a_T3255I | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| RDPD_P323L | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| S_D614G | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| S_E484K | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| S_H655Y | X | X | |||||||||||

| S_K417N | X | ||||||||||||

| S_N501Y | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| S_N679K | X | ||||||||||||

| S_P681R | X | X | |||||||||||

| S_Q954H | X | ||||||||||||

| S_S373P | X | ||||||||||||

| S_T478K | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).