Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. RNA Extraction

2.3. cDNA Synthesis

2.4. Primer Design and Synthesis

2.5. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Setup

2.6. Determination of Nucleotide Sequences

2.7. Lineage Determination and Mutation Identification of the Studied Isolates

2.8. Analysis of Non-Synonymous Mutation Function

2.9. Phylogenetic Analysis of Nucleotide Sequences

3. Results

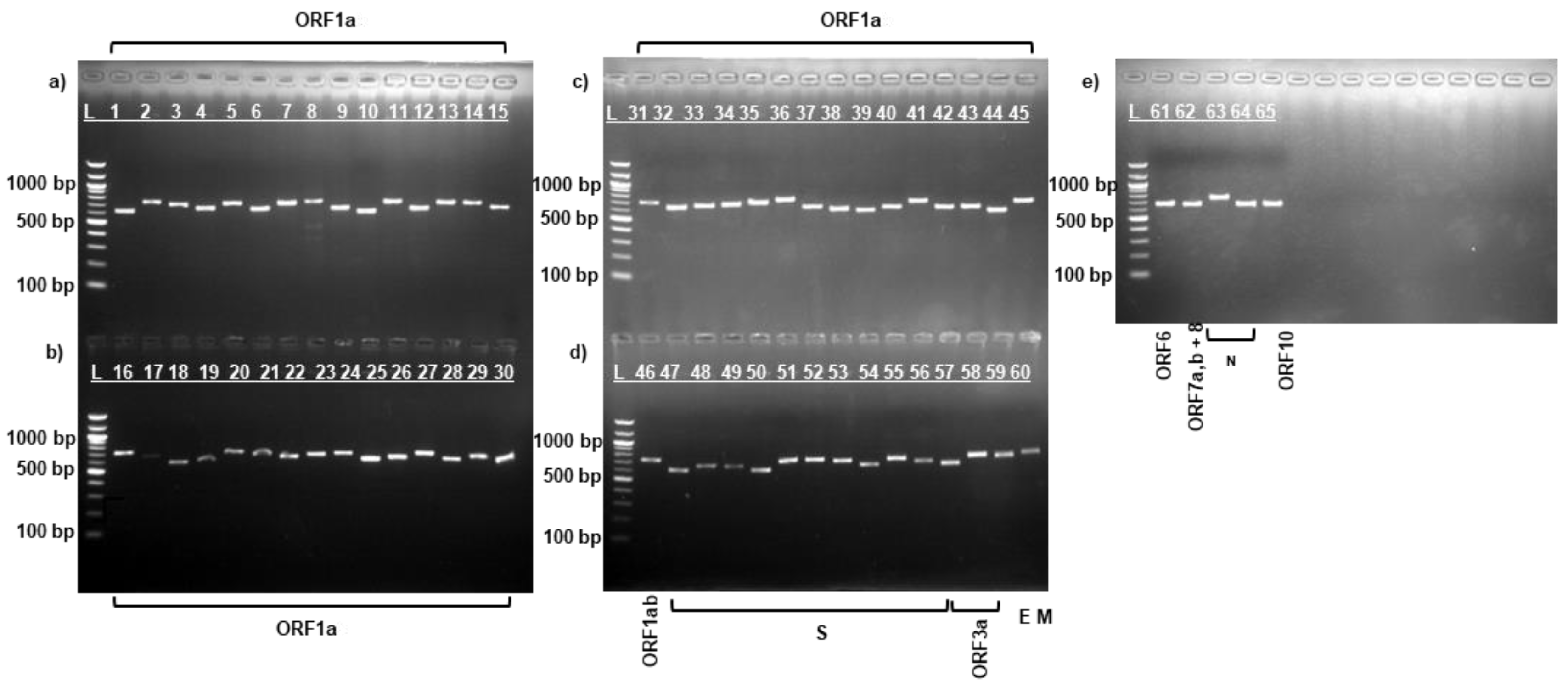

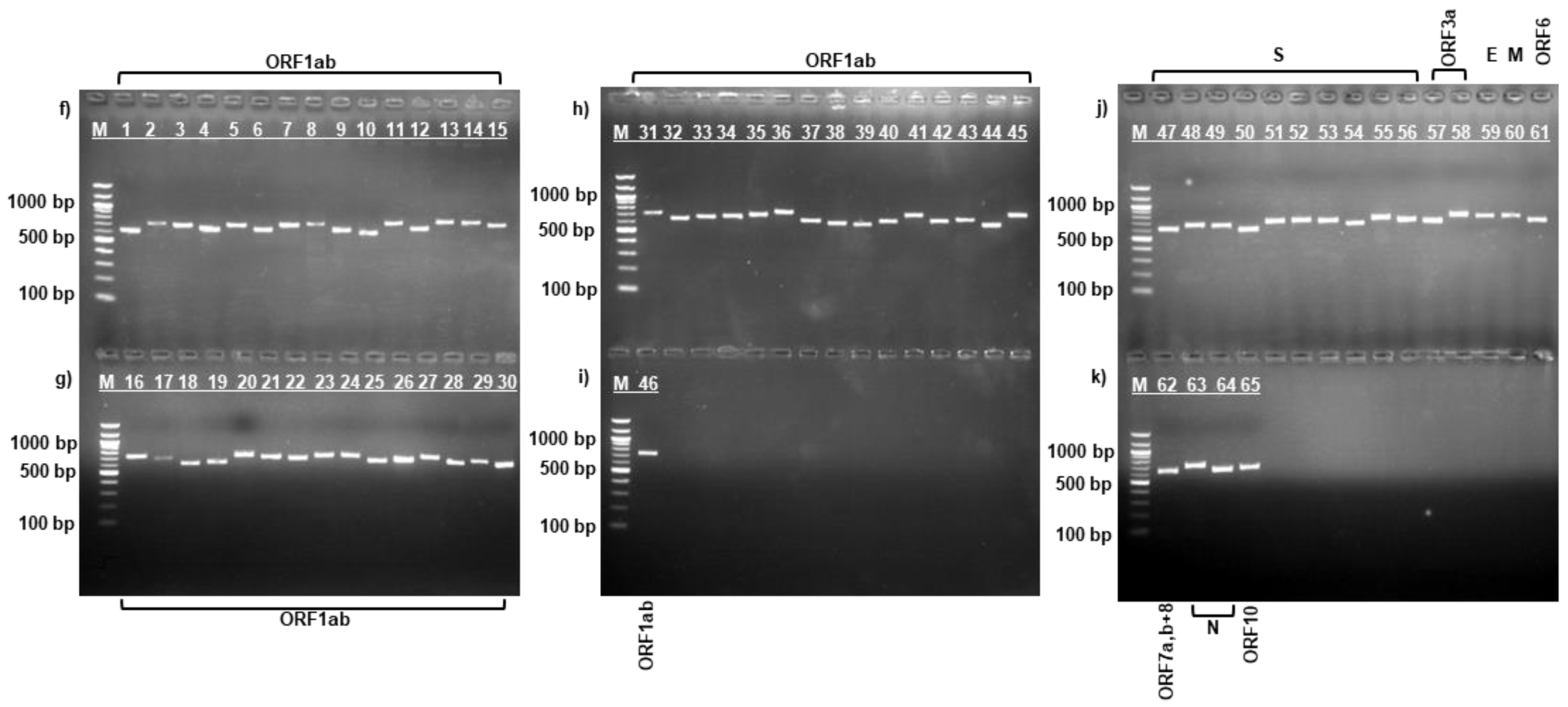

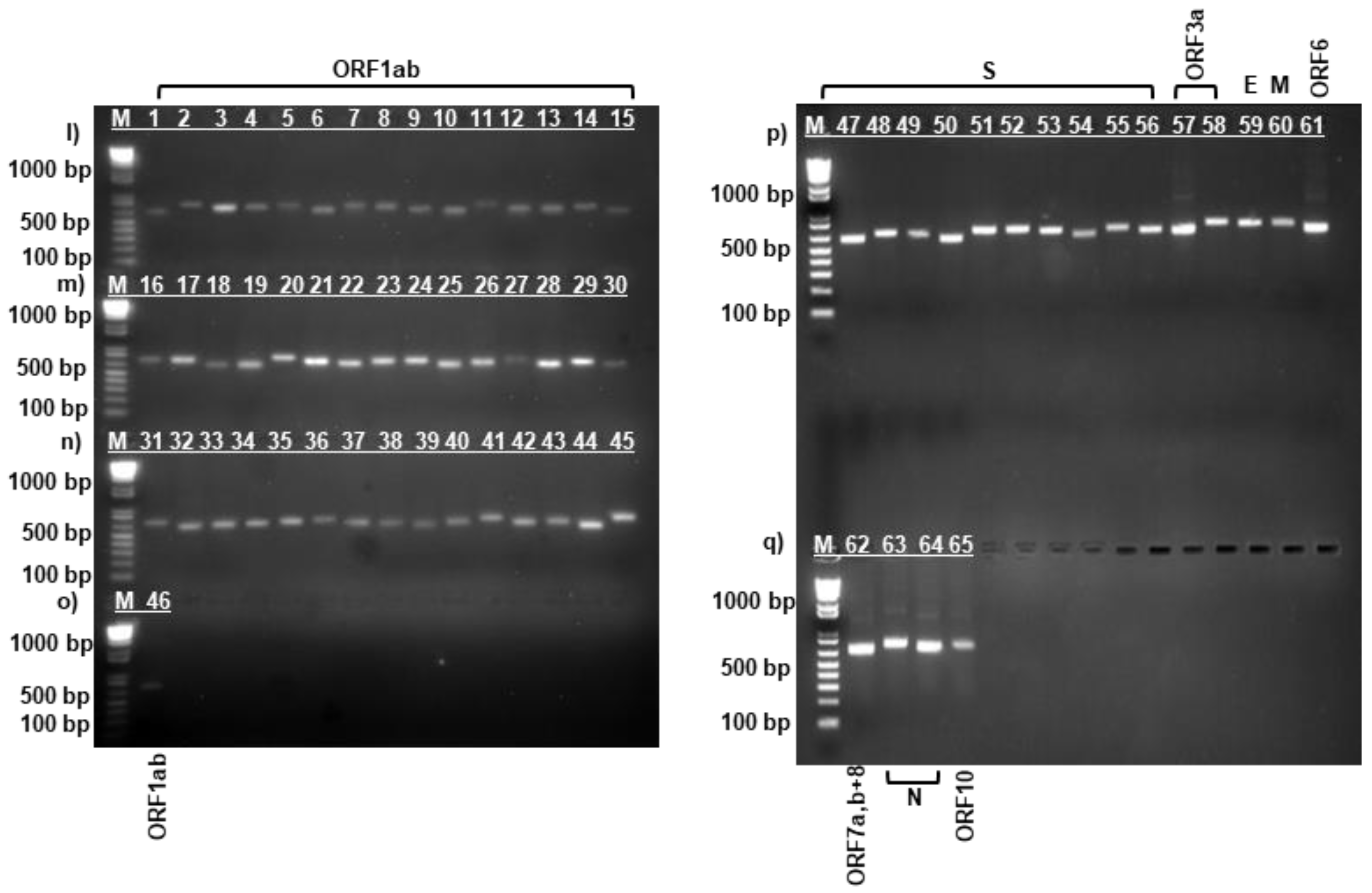

3.1. PCR Amplification of SARS-CoV-2 Virus Strains

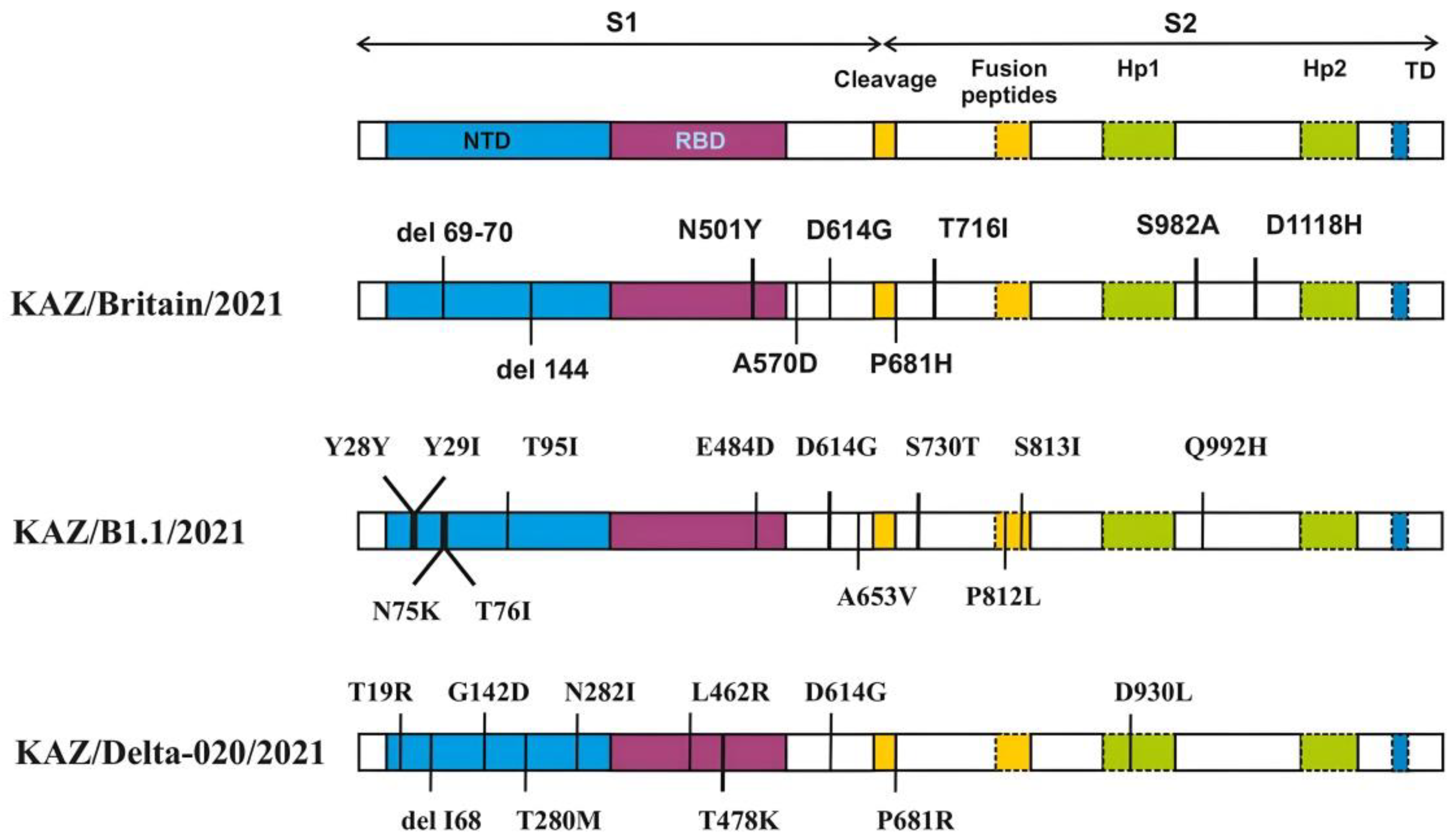

3.2. Characteristics of the Genomes of the Studied SARS-CoV-2 Virus Strains

3.3. Impact of Mutations on Biological Function of Proteins in the Studied SARS-CoV-2 Samples

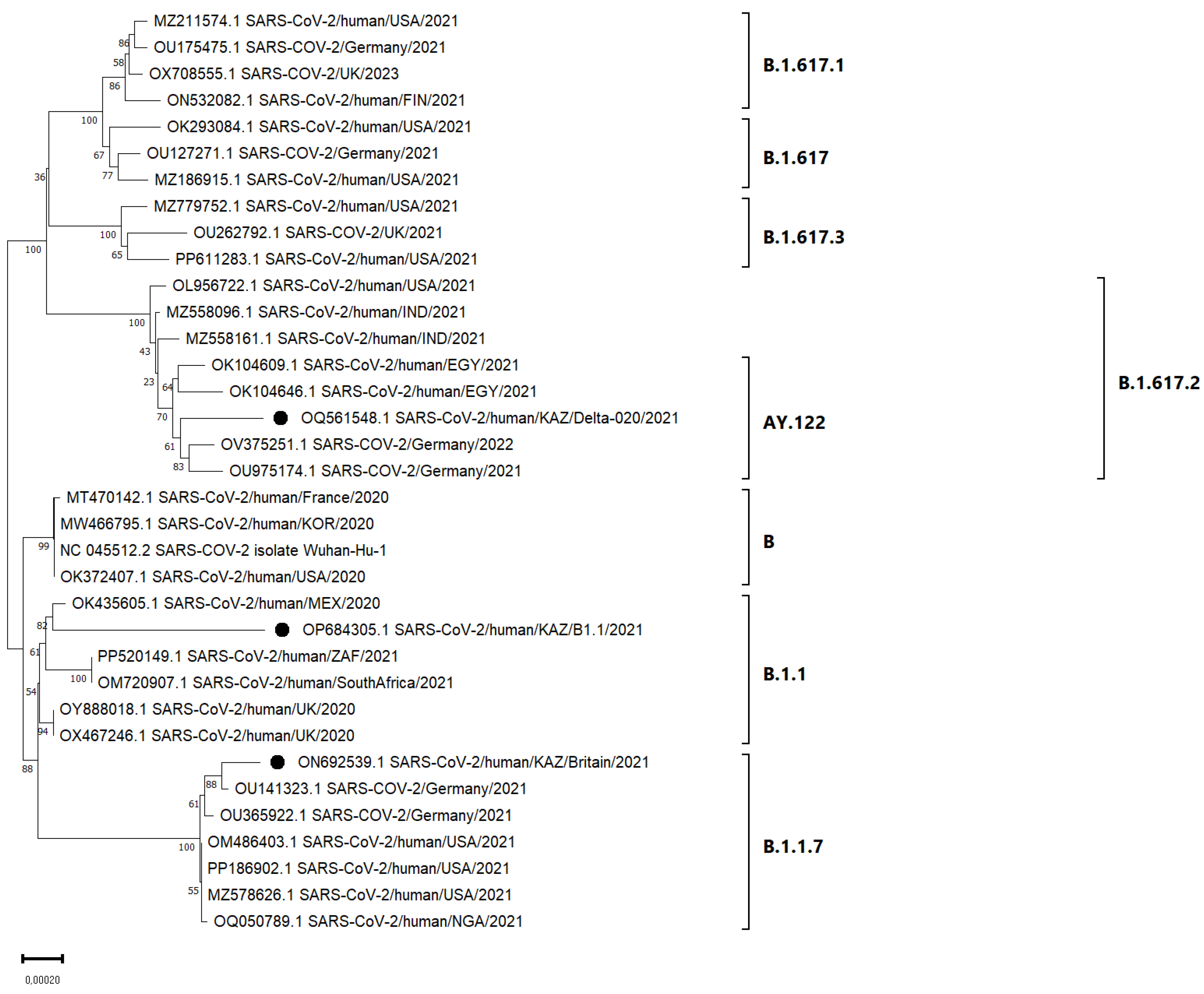

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020, 24, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhugunissov, K.; Zakarya, K.; Khairullin, B.; Orynbayev, M.; Abduraimov, Y.; Kassenov, M.; Sultankulova, K.; Kerimbayev, A.; Nurabayev, S.; Myrzakhmetova, B.; Nakhanov, A.; Nurpeisova, A.; Chervyakova, O.; Assanzhanova, N.; Burashev, Y.; Mambetaliyev, M.; Azanbekova, M.; Kopeyev, S.; Kozhabergenov, N.; Issabek, A.; Tuyskanova, M.; Kutumbetov, L. Development of the Inactivated QazCovid-in Vaccine: Protective Efficacy of the Vaccine in Syrian Hamsters. Front Microbiol. 2021, 12, 720437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usserbayev B, Zakarya K, Kutumbetov L, Orynbaуev M, Sultankulova K, Abduraimov Y, Myrzakhmetova B, Zhugunissov K, Kerimbayev A, Melisbek A, Shirinbekov M, Khaidarov S, Zhunushov A, Burashev Y. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2022, 11, 9–e0061922.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 727–733.

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; Yuan, M.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Dai, F.H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.M.; Zheng, J.J.; Xu, L.; Holmes, E.C.; Zhang, Y.Z. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [CrossRef]

- Cosar, B.; Karagulleoglu, Z.Y.; Unal, S.; Ince, A.T.; Uncuoglu, D.B.; Tuncer, G.; Kilinc, B.R.; Ozkan, Y.E.; Ozkoc, H.C.; Demir, I.N.; Eker, A.; Karagoz, F.; Simsek, S.Y.; Yasar, B.; Pala, M.; Demir, A.; Atak, I.N.; Mendi, A.H.; Bengi, V.U.; Cengiz Seval, G.; Gunes Altuntas, E.; Kilic, P.; Demir-Dora, D.S. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2022, 63, 10–22. [CrossRef]

- Safari, I.; Elahi, E. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 genome and emergence of variants of concern. Arch Virol. 2022, 167, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, M.; Lau, L.S.; Pokharel, M.D.; Ramelow, J.; Owens, F.; Souchak, J.; Akkaoui, J.; Ales, E.; Brown, H.; Shil, R.; Nazaire, V.; Manevski, M.; Paul, N.P.; Esteban-Lopez, M.; Ceyhan, Y.; El-Hage, N. Biology 2023, 12, 1267. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Behera, S.P.; Zaman, K.; Kant, R.; Singh, R. Genomic evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern: COVID-19 pandemic waves in India. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 451–465. [Google Scholar]

- Vidanović, D.; Tešović, B.; Volkening, J.D.; Afonso, C.L.; Quick, J.; Šekler, M.; Knežević, A.; Janković, M.; Jovanović, T.; Petrović, T.; Đeri, B.B. Epidemiol Infect. 2021, 149, e246. [CrossRef]

- Mercatelli, D.; Giorgi, F.M. Geographic and Genomic Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Mutations. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaTourrette, K.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. Determinants of Virus Variation, Evolution, and Host Adaptation. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez, S.; Prado-Vivar, B.; Guadalupe, J.J.; Gutierrez, B.; Jibaja, M.; Tobar, M.; Mora, F.; Gaviria, J.; García, M.; Espinosa, F.; Ligña, E.; Reyes, J.; Barragán, V.; Rojas-Silva, P.; Trueba, G.; Grunauer, M.; Cárdenas, P. Genome sequencing of the first SARS-CoV-2 reported from patients with COVID-19 in Ecuador. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2012; 2020.06.11.20128330. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, E.; Shafiee, F.; Shahzamani, K.; Ranjbar, M.M.; Alibakhshi, A.; Ahangarzadeh, S.; Beikmohammadi, L.; Shariati, L.; Hooshmandi, S.; Ataei, B.; Javanmard, S.H. Novel and emerging mutations of SARS-CoV-2: Biomedical implications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi Y, Chan A. P. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015, 31, 2745–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., and Kumar S.. MEGA 11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2021.

- Saitou N. and Nei M.. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1987, 4, 406–425.

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K. , Nei M., and Kumar S.. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA). 2004, 101, 11030–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burashev, Y.; Usserbayev, B.; Kutumbetov, L.; Abduraimov, Y.; Kassenov, M.; Kerimbayev, A.; Myrzakhmetova, B.; Melisbek, A.; Shirinbekov, M.; Khaidarov, S.; Tulman, E.R. Coding Complete Genome Sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus Strain, Variant B.1.1, Sampled from Kazakhstan. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2022, 11, e0111422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usserbayev, B.; Abduraimov, Y.; Kozhabergenov, N.; Melisbek, A.; Shirinbekov, M.; Smagul, M.; Nusupbaуeva, G.; Nakhanov, A.; Burashev, Y. Complete Coding Sequence of a Lineage AY.122 SARS-CoV-2 Virus Strain Detected in Kazakhstan. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2023, 12, e0030123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian Alfredo, K. Cruz, Paul Mark B. Medina. Temporal changes in the accessory protein mutations of SARS-CoV-2 variants and their predicted structural and functional effects. 2022, 94.

- Cleaveland, S.; Laurenson, M.K.; Taylor, L.H. Diseases of humans and their domestic mammals: pathogen characteristics, host range and the risk of emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001, 356, 991–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, K.; Parvez, M.K.; Al-Dosari, M.S. Comparative sequence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 suggests its high transmissibility and pathogenicity. Future Virol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.K.; Parveen, S. Evolution and Emergence of Pathogenic Viruses: Past, Present, and Future. Intervirology. 2017, 60(1-2):1-7.

- Lee, S.H. A Routine Sanger Sequencing Target Specific Mutation Assay for SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern and Interest. Viruses. 2021, 13, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Zai, J.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y.; Chaillon, A. Transmission dynamics and evolutionary history of 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. 2020, 92, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lai, D.Y.; Zhang, H.N.; Jiang, H.W.; Tian, X.; Ma, M.L.; Qi, H.; Meng, Q.F.; Guo, S.J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, X.; Shi, D.W.; Dai, J.B.; Ying, T.; Zhou, J.; Tao, S.C. Linear epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein elicit neutralizing antibodies in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020, 17, 1095–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, M.H.; Mahmanzar, M.; Rahimian, K.; Mahdavi, B.; Tokhanbigli, S.; Moradi, B.; Sisakht, M.M.; Deng, Y. Global landscape of SARS-CoV-2 mutations and conserved regions. J Transl Med. 2023, 21, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey WT, Carabelli AM, Jackson B, Gupta RK, Thomson EC, Harrison EM, Ludden C, Reeve R, Rambaut A; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium; Peacock SJ, Robertson DL. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esman, A.; Dubodelov, D.; Khafizov, K.; Kotov, I.; Roev, G.; Golubeva, A.; Gasanov, G.; Korabelnikova, M.; Turashev, A.; Cherkashin, E.; Mironov, K.; Cherkashina, A.; Akimkin, V. Development and Application of Real-Time PCR-Based Screening for Identification of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 Variant Sublineages. Genes (Basel). 2023, 14, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.; San, J.E.; Tegally, H.; Brzoska, P.M.; Anyaneji, U.J.; Wilkinson, E.; Clark, L.; Giandhari, J.; Pillay, S.; Lessells, R.J.; Martin, D.P.; Furtado, M.; Kiran, A.M.; de Oliveira, T. Targeted Sanger sequencing to recover key mutations in SARS-CoV-2 variant genome assemblies produced by next-generation sequencing. Microb Genom. 2022, 8, 000774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: a guide to implementation for maximum impact on public health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- Supasa, P.; Zhou, D.; Dejnirattisai, W.; Liu, C.; Mentzer, A.J.; Ginn, H.M.; Zhao, Y.; Duyvesteyn, H.M.E.; Nutalai, R.; Tuekprakhon, A.; Wang, B.; Paesen, G.C.; Slon-Campos, J.; López-Camacho, C.; Hallis, B.; Coombes, N.; Bewley, K.R.; Charlton, S.; Walter, T.S.; Barnes, E.; Dunachie, S.J.; Skelly, D.; Lumley, S.F.; Baker, N.; Shaik, I.; Humphries, H.E.; Godwin, K.; Gent, N.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Dold, C.; Levin, R.; Dong, T.; Pollard, A.J.; Knight, J.C.; Klenerman, P.; Crook, D.; Lambe, T.; Clutterbuck, E.; Bibi, S.; Flaxman, A.; Bittaye, M.; Belij-Rammerstorfer, S.; Gilbert, S.; Hall, D.R.; Williams, M.A.; Paterson, N.G.; James, W.; Carroll, M.W.; Fry, E.E.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D.I.; Screaton, G.R. Reduced neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant by convalescent and vaccine sera. Cell. 2021, 184, 2201–2211.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Ji, W.; Li, C.; Ren, L. Recent progress on the mutations of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and suggestions for prevention and controlling of the pandemic. Infect Genet Evol. 2021, 93, 104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar P, Niyogi S. SARS-CoV-2 mutations: the biological trackway towards viral fitness. Epidemiol Infect. 2021, 149, e110. [CrossRef]

- Meng B, Kemp SA, Papa G, Datir R, Ferreira IATM, Marelli S, Harvey WT, Lytras S, Mohamed A, Gallo G, Thakur N, Collier DA, Mlcochova P; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium; Duncan LM, Carabelli AM, Kenyon JC, Lever AM, De Marco A, Saliba C, Culap K, Cameroni E, Matheson NJ, Piccoli L, Corti D, James LC, Robertson DL, Bailey D, Gupta RK. Recurrent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 spike deletion H69/V70 and its role in the Alpha variant B.1.1.7. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109292.

- Weng, S.; Zhou, H.; Ji, C.; Li, L.; Han, N.; Yang, R.; Shang, J.; Wu, A. Conserved Pattern and Potential Role of Recurrent Deletions in SARS-CoV-2 Evolution. Microbiol Spectr. 2022, 10, e0219121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.R.; Rennick, L.J.; Nambulli, S.; Robinson-McCarthy, L.R.; Bain, W.G.; Haidar, G.; Duprex, W.P. Recurrent deletions in the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein drive antibody escape. Science. 2021, 371, 1139–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, NG; et al. Estimated transmissibility and severity of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/01 in England. medRxiv. 2020.

- Liu H, Yuan M, Huang D, Bangaru S, Zhao F, Lee CD, et al. A combination of cross-neutralizing antibodies synergizes to prevent SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV pseudovirus infection. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetran, S.R.; Mustafa, R. Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Structural Proteins in the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta Variants: Bioinformatics Analysis. JMIR Bioinform Biotech 2023, 4, e43906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; Chen, H.D.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Guo, H.; Jiang, R.D.; Liu, M.Q.; Chen, Y.; Shen, X.R.; Wang, X.; Zheng, X.S.; Zhao, K.; Chen, Q.J.; Deng, F.; Liu, L.L.; Yan, B.; Zhan, F.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Xiao, G.F.; Shi, Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, Hengartner N, Giorgi EE, Bhattacharya T, Foley B, Hastie KM, Parker MD, Partridge DG, Evans CM, Freeman TM, de Silva TI; Sheffield COVID-19 Genomics Group; McDanal C, Perez LG, Tang H, Moon-Walker A, Whelan SP, LaBranche CC, Saphire EO, Montefiori DC. Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell. 2020, 182, 812–827.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinski, B.; Fernandes, M.H.V.; Frazier, L.; Tang, T.; Daniel, S.; Diel, D.G.; Jaimes, J.A.; Whittaker, G.R. Functional evaluation of the P681H mutation on the proteolytic activation the SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 (Alpha) spike. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2021, 04.06.438731.

- Dhawan M, Sharma A, Priyanka, Thakur N, Rajkhowa TK, Choudhary OP. Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2: Mutations, impact, challenges and possible solutions. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022, 18, 2068883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.I.; Ether, S.A.; Islam, M.R. The "Delta Plus" COVID-19 variant has evolved to become the next potential variant of concern: mutation history and measures of prevention. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2021, 33, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Thambiraja, T.S.; Karuppanan, K.; Subramaniam, G. Omicron and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2: A comparative computational study of spike protein. J Med Virol. 2022, 94, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planas, D.; Veyer, D.; Baidaliuk, A.; Staropoli, I.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Rajah, M.M.; Planchais, C.; Porrot, F.; Robillard, N.; Puech, J.; Prot, M.; Gallais, F.; Gantner, P.; Velay, A.; Le Guen, J.; Kassis-Chikhani, N.; Edriss, D.; Belec, L.; Seve, A.; Courtellemont, L.; Péré, H.; Hocqueloux, L.; Fafi-Kremer, S.; Prazuck, T.; Mouquet, H.; Bruel, T.; Simon-Lorière, E.; Rey, F.A.; Schwartz, O. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021, 596, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlcochova P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature. 2021, 599, 114–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abavisani, M.; Rahimian, K.; Mahdavi, B.; Tokhanbigli, S.; Mollapour Siasakht, M.; Farhadi, A.; Kodori, M.; Mahmanzar, M.; Meshkat, Z. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 structural proteins: a global analysis. Virol J. 2022, 19, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periwal, N.; Rathod, S.B.; Sarma, S.; Johar, G.S.; Jain, A.; Barnwal, R.P.; Srivastava, K.R.; Kaur, B.; Arora, P.; Sood, V. Time Series Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Genomes and Correlations among Highly Prevalent Mutations. Microbiol Spectr. 2022, 10, e0121922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Yang, J.S.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, V.N.; Chang, H. The Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 Transcriptome. Cell. 2020, 181, 914–921.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Pathan, A.Q.M.S.U.; Islam, M.N.; Tonmoy, M.I.Q.; Rakib, M.I.; Munim, M.A.; Saha, O.; Fariha, A.; Reza, H.A.; Roy, M.; Bahadur, N.M.; Rahaman, M.M. Genome-wide identification and prediction of SARS-CoV-2 mutations show an abundance of variants: Integrated study of bioinformatics and deep neural learning. Inform Med Unlocked. 2021, 27, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subissi L, Imbert I, Ferron F, Collet A, Coutard B, Decroly E, Canard B. SARS-CoV ORF1b-encoded nonstructural proteins 12-16: replicative enzymes as antiviral targets. Antiviral Res. 2014, 101, 122–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad D, John SE, Mohammad A, Hammad MM, Hebbar P, Channanath A, Nizam R, Al-Qabandi S, Al Madhoun A, Alshukry A, Ali H, Thanaraj TA, Al-Mulla F. SARS-CoV-2: Possible recombination and emergence of potentially more virulent strains. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0251368.

- Anand Archana, Chenghua Long, Kartik Chandran. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 amino acid mutations in New York City Metropolitan wastewater (2020-2022) reveals multiple traits with human health implications across the genome and environment-specific distinctions. medRxiv 2022, 07.15.22277689.

- Gao, Y.; Yan, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, T.; Sun, Q.; Ming, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ge, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Hu, T.; Hua, T.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, W.; Guddat, L.W.; Wang, Q.; Lou, Z.; Rao, Z. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science. 2020, 368, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira IATM, Kemp SA, Datir R, Saito A, Meng B, Rakshit P, Takaori-Kondo A, Kosugi Y, Uriu K, Kimura I, Shirakawa K, Abdullahi A, Agarwal A, Ozono S, Tokunaga K, Sato K, Gupta RK; CITIID-NIHR BioResource COVID-19 Collaboration, Indian SARS-CoV-2 Genomics Consortium; Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617 Mutations L452R and E484Q Are Not Synergistic for Antibody Evasion. J Infect Dis. 2021, 224, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Milan New 'Delta Plus' variant of SARS-CoV-2 identified; here's what we know so far. India Today. 2023.

| Protein | Data for strain: | Amino acid change | ||||||||

| Wuhan-Hu-1a | KAZ/Britain/2021 | KAZ/B1.1/2021 | KAZ/Delta020/2021 | Type of mutation | ||||||

| Position | Variant | Variant | Position | Variant | Position | Variant | Position | |||

| 5′ UTRb | 106 | C | - | - | T | 29 | - | - | - | 106 |

| 210 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 184 | - | 210 | |

| 241 | C | T | 215 | T | 164 | T | 215 | - | 241 | |

| ORF1ab | 344 | C | - | - | T | 267 | - | - | SNP | L27F |

| 913 | C | T | 887 | - | - | - | - | SNP_silent | S36S | |

| 1048 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 1022 | SNP | K81Nc | |

| 1688 | A | C | 1662 | - | - | - | - | SNP | I295L | |

| 1899 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 1873 | SNP | R365L | |

| 2110 | C | T | 2084 | - | - | - | - | SNP_silent | N435N | |

| 2530 | A | - | - | G | 2453 | - | - | SNP_silent | E575E | |

| 3037 | C | T | 3011 | T | 2960 | T | 3011 | SNP_silent | F106F | |

| 3267 | C | T | 3241 | - | - | - | - | SNP | T183I | |

| 4181 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 4155 | SNP | A488S | |

| 4449 | C | - | - | A | 4372 | - | - | SNP | T577N | |

| 4455 | C | - | - | T | 4378 | - | - | SNP | A579V | |

| 4475 | C | - | - | T | 4398 | - | - | SNP | R586C | |

| 5388 | C | A | 5362 | - | - | - | - | SNP | A890D | |

| 5829 | A | - | - | C | 5752 | - | - | SNP | K1037T | |

| 5986 | C | T | 5960 | - | - | - | - | SNP_silent | F1089F | |

| 6402 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 6376 | SNP | P1228L | |

| 6954 | T | C | 6928 | - | - | - | - | SNP | I1412T | |

| 7042 | G | T | 7016 | - | - | - | - | SNP | M1441I | |

| 7124 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 7098 | SNP | P1469S | |

| 8986 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 8960 | SNP_silent | D144D | |

| 9053 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 9027 | SNP | V167L | |

| 9749 | A | - | - | G | 9672 | - | - | SNP | K399E | |

| 9867 | T | - | - | G | 9790 | - | - | SNP | L438R | |

| 10029 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 10003 | SNP | T492I | |

| 10198 | C | - | - | T | 10121 | - | - | SNP_silent | D48D | |

| 11195 | C | T | 11169 | - | - | - | - | SNP | L75F | |

| 11201 | A | - | - | - | - | G | 11175 | SNP | T77A | |

| 11288 | TCTGGTTTT | del | 11261 | del | 11210 | - | - | SNP_stop | S106 | |

| 11332 | A | - | - | G | 11306 | SNP_silent | V120V | |||

| 14120 | C | T | 14085 | - | - | SNP | P218L | |||

| 14408 | C | T | 14373 | T | 14322 | T | 14382 | SNP | P314L | |

| 14676 | C | T | 14641 | - | - | - | - | SNP_silent | P403P | |

| 15017 | C | - | - | T | 14931 | - | - | SNP | A517V | |

| 15279 | C | T | 15244 | - | - | - | - | SNP_silent | H604H | |

| 15451 | G | - | - | - | - | A | 15425 | SNP | G662S | |

| 16176 | T | C | 16141 | - | - | - | - | SNP | T903T | |

| 16466 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 16440 | SNP | P77L | |

| 18271 | G | - | - | - | - | A | 18245 | SNP | E78K | |

| 18337 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 18311 | SNP | A100S | |

| 19220 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 19194 | SNP | A394V | |

| 20405 | C | T | 20370 | - | - | - | - | SNP | P262L | |

| 20759 | C | - | - | T | 20673 | - | - | SNP | A34V | |

| 21080 | A | - | - | G | 20994 | - | - | SNP | K141R | |

| 21215 | A | G | 21180 | - | - | - | - | SNP | H186R | |

| 21446 | A | - | - | G | 21360 | - | - | SNP | K263R | |

| 3′ UTR | 27389 | C | - | - | T | 27303 | - | - | - | 27389 |

| 29733 | - | - | - | TA | 29648 | - | - | - | 29733 | |

| 29742 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 29716 | - | 29742 | |

| 29755 | - | - | - | C | 29672 | - | - | - | 29755 | |

| 29790 | - | - | - | T | 29708 | - | - | - | 29790 | |

| Protein | Data for strain: | |||||||

| Wuhan-Hu-1a | KAZ/Britain/2021 | KAZ/B1.1/2021 | KAZ/Delta020/2021 | |||||

| Position | Variant | Variant | Position | Variant | Position | Variant | Position | |

| S | 21618 | C | - | - | - | - | G | 21592 |

| 21646 | C | - | - | T | 21560 | - | - | |

| 21648 | C | - | - | T | 21562 | - | - | |

| 21765 | TACATG | del | 21729 | - | - | - | - | |

| 21766 | A | - | - | - | - | del | 21739 | |

| 21784 | T | - | - | A | 21698 | - | - | |

| 21789 | C | - | - | T | 21703 | - | - | |

| 21846 | C | - | - | T | 21760 | - | - | |

| 21987 | G | - | - | - | - | A | 21961 | |

| 21993 | ATT | del | 21951 | - | - | - | - | |

| 22185 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 22159 | |

| 22407 | A | - | - | - | - | T | 22381 | |

| 22917 | T | - | - | - | - | G | 22891 | |

| 22995 | C | - | - | - | - | A | 22969 | |

| 23014 | A | - | - | C | 22928 | - | - | |

| 23063 | A | T | 23019 | - | - | - | - | |

| 23271 | C | A | 32227 | - | - | - | - | |

| 23403 | A | G | 23359 | G | 23317 | G | 23377 | |

| 23520 | C | - | - | T | 23434 | - | - | |

| 23604 | C | A | 23560 | - | - | G | 23578 | |

| 23709 | C | T | 23665 | - | - | - | - | |

| 23751 | C | - | - | T | 23665 | - | - | |

| 23997 | C | - | - | T | 23911 | - | - | |

| 24000 | G | - | - | T | 23914 | - | - | |

| 24410 | G | - | - | - | - | A | 24384 | |

| 24506 | T | G | 24462 | - | - | - | - | |

| 24538 | A | - | - | T | 24452 | - | - | |

| 24914 | G | C | 24870 | - | - | - | - | |

| Protein | Data for strain: | Amino acid change | ||||||||

| Wuhan-Hu-1a | KAZ/Britain/2021 | KAZ/B1.1/2021 | KAZ/Delta020/2021 | Type of mutation | ||||||

| Position | Variant | Variant | Position | Variant | Position | Variant | Position | |||

| ORF3a | 25459 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 25443 | SNP | S26Lb |

| 25688 | C | - | - | T | 25602 | - | - | SNP | A99V | |

| 25838 | G | T | 25794 | - | - | - | - | SNP | W149L | |

| 26110 | C | - | - | T | 26024 | - | - | SNP | P240S | |

| M | 26767 | T | - | - | - | - | C | 26741 | SNP | I82T |

| 26895 | C | - | - | T | 26809 | - | - | SNP | H125Y | |

| 27008 | G | - | - | T | 26922 | - | - | SNP | K162N | |

| ORF6 | 27281 | GG | AA | 27237 | - | - | - | - | SNP_stop | W27 |

| 27285 | TC | AT | 27241 | - | - | - | - | SNP | NL28KF | |

| ORF7a | 27527 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 27501 | SNP | P45L |

| 27638 | T | - | - | - | - | C | 27612 | SNP | V82A | |

| 27630 | C | - | - | T | 27544 | - | - | SNP_silent | A79A | |

| 27667 | G | - | - | A | 27581 | - | - | SNP | E92K | |

| 27739 | C | - | - | T | 27653 | - | - | SNP | L116F | |

| 27752 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 27726 | SNP | T120I | |

| ORF7b | 27874 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 27848 | SNP | T40I |

| ORF8 | 27919 | T | - | - | - | - | C | 27893 | SNP | I9T |

| 27972 | C | T | 27928 | - | - | - | - | SNP_stop | Q27 | |

| 28048 | G | T | 28004 | - | - | - | - | SNP | R52I | |

| 28095 | A | T | 28051 | - | - | - | - | SNP_stop | K68 | |

| 28111 | A | G | 28067 | - | - | - | - | SNP | Y73C | |

| 28251 | T | - | - | - | - | C | 28225 | SNP | F120L | |

| 28253 | C | - | - | - | - | A | 28227 | SNP | F120L | |

| 28255 | T | - | - | - | - | A | 28229 | SNP | I121N | |

| 28258 | A | - | - | - | - | G | 28232 | SNP_silent | *122* | |

| N | 28280 | GAT | CTA | 28236 | - | - | - | - | SNP | D3L |

| 28461 | A | - | - | - | G | 28435 | SNP | D63G | ||

| 28881 | GGG | AAC | 28837 | AAC | 28837 | - | - | SNP | RG203KR | |

| 28881 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 28855 | SNP | R203M | |

| 28916 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 28890 | SNP | G215C | |

| 28977 | C | T | 28933 | - | - | - | - | SNP | S235F | |

| 29236 | C | - | - | - | - | T | 29210 | SNP_silent | G312G | |

| 29402 | G | - | - | - | - | T | 29376 | SNP | D377Y | |

| 29436 | A | - | - | T | 29350 | - | - | SNP | K388I | |

| Protein | KAZ/Britain/2021 | KAZ/B1.1/2021 | KAZ/Delta020/2021 | ||||||

| Amino acid change | Оценка PROVEAN |

The effect of variation on protein |

Amino acid change | Оценка PROVEAN | The effect of variation on protein |

Amino acid change | Оценка PROVEAN | The effect of variation on protein |

|

| ORF1ab | I295L | 0.232 | Neutral | L27F | -0.047 | Neutral | K81N | -0.070 | Neutral |

| T183I | 0.216 | Neutral | A579V | 0.011 | Neutral | R365L | -0.939 | Neutral | |

| T577N | 0.240 | Neutral | R586C | -0.727 | Neutral | A488S | -0.061 | Neutral | |

| A890D | -1.749 | Neutral | K1037T | -1.196 | Neutral | P1228L | -1.038 | Neutral | |

| I1412T | -0.370 | Neutral | K399E | -1.877 | Neutral | P1469S | 0.338 | Neutral | |

| M1441I | 0.263 | Neutral | L438R | 0.659 | Neutral | V167L | -0.696 | Neutral | |

| L75F | -2.290 | Neutral | P314L | -0.446 | Neutral | T492I | 1.435 | Neutral | |

| P218L | -5.021 | Deleterious | A517V | -1.291 | Neutral | T77A | -0.878 | Neutral | |

| P314L | -0.446 | Neutral | A34V | 1.158 | Neutral | P314L | -0.446 | Neutral | |

| P262L | -0.014 | Neutral | K141R | -0.221 | Neutral | G662S | -2.475 | Neutral | |

| H186R | -0.267 | Neutral | K263R | -1.344 | Neutral | P77L | -6.845 | Deleterious | |

| - | - | - | E78K | -1.123 | Neutral | ||||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | A100S | 1.338 | Neutral | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | A394V | -1.523 | Neutral | |

| S | H69del | 0.260 | Neutral | Y28Y | 0.000 | Neutral | T19R | -0.839 | Neutral |

| Y145del | 0.853 | Neutral | T29I | -1.538 | Neutral | I68del | -0.821 | Neutral | |

| N501Y | -0.090 | Neutral | N74K | -1.309 | Neutral | G142D | -0.277 | Neutral | |

| A570D | -0.682 | Neutral | T76I | -0.115 | Neutral | T208M | -0.314 | Neutral | |

| D614G | 0.598 | Neutral | T95I | -1.214 | Neutral | N282I | -3.717 | Deleterious | |

| P681H | 0.060 | Neutral | E484D | -0.210 | Neutral | L452R | 0.559 | Neutral | |

| T716I | -3.293 | Deleterious | D614G | 0.598 | Neutral | T478K | -0.524 | Neutral | |

| S982A | -1.505 | Neutral | A653V | -0.715 | Neutral | D614G | 0.598 | Neutral | |

| D1118H | -1.142 | Neutral | S730T | -0.040 | Neutral | P681R | 0.741 | Neutral | |

| - | - | - | P812L | -0.868 | Neutral | D950N | -1.631 | Neutral | |

| - | - | - | S813I | -2.867 | Deleterious | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | Q992H | -4.059 | Deleterious | - | - | - | |

| ORF3a | - | - | - | - | - | - | S26L | -2.314 | Neutral |

| A99V | -1.962 | Neutral | - | - | - | ||||

| W149L | -9.419 | Deleterious | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| - | - | - | P240S | -1.495 | Neutra | - | - | - | |

| M | - | - | - | I82T | -3.853 | Deleterious | |||

| - | - | - | H125Y | 0.799 | Neutral | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | K162N | 0.501 | Neutral | - | - | - | |

| ORF7a | - | - | - | - | - | - | P45L | -10.000 | Deleterious |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | V82A | -2.667 | Deleterious | |

| - | - | - | A79A | 0.000 | Neutral | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | E92K | -1.842 | Neutral | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | L116F | -1.263 | Neutral | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | T120I | -1.789 | Neutral | |

| ORF7b | - | - | - | - | - | - | T40I | -2.000 | Neutral |

| ORF8 | - | - | - | I9T | -1.333 | Neutral | |||

| R52I | -6.417 | Deleterious | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Y73C | -4.500 | Deleterious | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | F120L | -2.667 | Deleterious | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | F120L | -2.667 | Deleterious | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | I121N | -0.667 | Neutral | |

| N | D3L | -0.230 | Neutral | - | - | - | |||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | D63G | -0.929 | Neutral | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | R203M | -3.304 | Deleterious | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | G215C | -0.953 | Neutral | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | S235F | -1.738 | Neutral | |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | D377Y | -1.779 | Neutral | |

| - | - | - | K388I | -1.204 | Neutral | - | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).