1. Introduction

The emergence of novel mutations of SARS-CoV-2 introduced new challenges and breakthroughs in the global fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. These mutations in the viral genome, have impacted various aspects of the pandemic response [

1,

2]. Notably, mutations in the spike gene and other accessory genes have been identified, affecting transmission dynamics, vaccine efficacy, disease severity, therapeutic interventions, diagnostic testing, and public health measures [

3,

4]. Within the spike gene, several mutations such as R203K, G204R, N501Y, E484K, L452R, and E484Q have been identified, which have the potential to increase viral replication, fitness, and immune evasion [

3,

4].

Additionally, the D614G mutation in the spike protein has been found to influence the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 by enhancing spike protein trafficking to lysosomes, resulting in decreased spike expression on the cell surface [

5]. Epistasis, the interaction between mutations, has also been studied extensively in the context of SARS-CoV-2. Research has shown that mutations in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein can confer resistance to neutralizing antibodies, indicating complex interactions between mutations and antibody recognition [

6]. Studies have identified sites under strong and weak epistatic constraints, highlighting their roles in viral replication and pathogenicity [

7]. Furthermore, deep mutational scans have revealed epistatic shifts in the effects of mutations, suggesting that certain substitutions shape subsequent evolutionary changes [

8]. Bernando et al. also found that substitutions in the RBD can cause epistatic shifts, influencing the virus's affinity for the ACE2 receptor [

9].

In Kenya, the pandemic has been characterized by multiple waves, each with unique features. Initial waves occurred before the emergence of variants of concern (VoCs) and had lower attack rates [

10]. Subsequent waves, driven by Alpha, Delta, and Omicron VoCs, exhibited higher attack rates [

10]. The Omicron variant, notably first identified in South Africa, gained worldwide recognition due to its numerous mutations, particularly in the spike protein's receptor-binding domain [

11]. The occurrence and rise of new strains of the SARS-CoV-2 virus have drawn global attention and caused concern. These changes can affect how easily the pathogen spreads, how severe the disease is, or its ability to escape immune system responses.

Every new mutation brings more uncertainty about what it could mean for the pandemic. Worries include the possibility of faster community spread and potential reduced efficacy of existing vaccines. The emergence of new mutations among general populations can be a cause of confusion and anxiety. This further fuels fear and panic, especially in places already severely hit by the virus. This emphasis on novel strains mirrors international anxiety to understand and tackle COVID-19 urgently. To keep the virus from spreading, there has to be constant monitoring alongside research as well as cooperation between countries

2. Materials and Methods

Swab samples were obtained from the oropharynx/nasopharynx of patients attending Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret, North Rift Kenya subsequent to obtaining informed consent as well as Institutional Review and Ethics Committee (IREC) approval. These samples were then preserved in viral transport medium (VTM) and transported to the laboratory within a period of 6 hours, adhering strictly to the cold chain, and subsequently stored at -20°C. Utilizing the DaAn Gene Detection kit for 2019-nCoV (DaAnGene, China) on the Rotor Gene Q real-time PCR machine, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis was performed. Samples yielding positive results for SARS-CoV-2 with a cycle threshold (CT) value less than 30 were earmarked for sequencing.

Prior to sequencing, samples underwent preparation procedures. Initially, reverse transcription (RT) was carried out using the SuperScript™ IV Reverse Transcriptase kit from Illumina, enabling the conversion of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA). Subsequent to this, cDNA underwent amplification via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting specific SARS-CoV-2 genes, facilitated by the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit. During library preparation, adapters tailored for Illumina sequencing were affixed to the amplified fragments. Cleanup procedures were then conducted utilizing the Agencourt AMPure XP system, followed by size selection to eliminate contaminants. Quantification of library concentration was performed using qubit to ensure an optimal loading concentration. Finally, sequencing was executed using the MiSeq sequencing platform (Illumina, California, USA), adhering strictly to the manufacturer’s stipulated protocols.

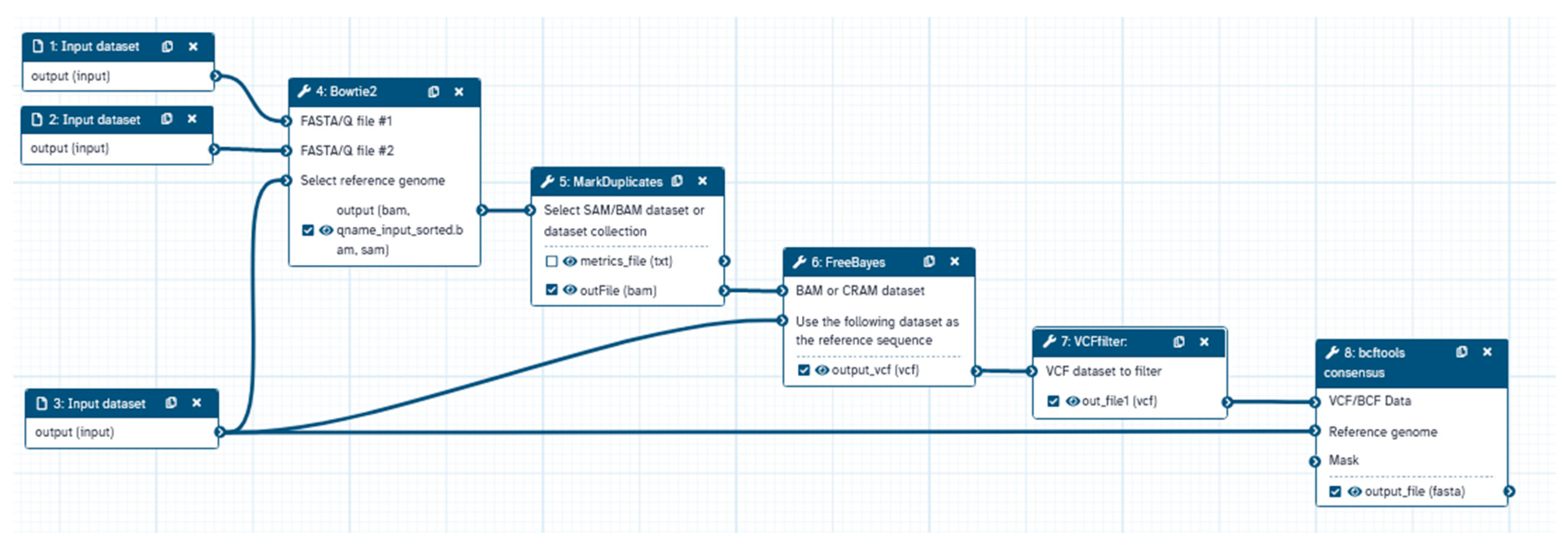

After to sequencing, bioinformatics analyses were performed utilizing the Galaxy platform through steps shown in

Figure 1. Initial quality assessments of sequencing data were conducted utilizing FastQC. This was followed by sequence trimming using the trim sequence tool and alignment to the reference SARS-CoV-2 genome (NCBI accession number MN908947.2) employing bowtie2 [

12]. Duplicate sequences were removed via the Markduplicates tool. Variant calling was executed using FreeBayes [

13], with subsequent variant filtering utilizing VCFfilter to ensure criteria met for read depth (DP >30), allele frequency (AF >0.2), and variant quality (QUAL >30). The consensus tool was then employed to generate a fasta file amalgamating variant information.

Further categorization of SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences into genetic lineages was achieved utilizing the Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak LiNeages (PANGOLIN). Annotation of sequences was carried out using the COVID-19 Annotation tool (

http://giorgilab. unibo.it/coronannotator/) [

14].

To elucidate novel mutations, sequences from previous mutations were retrieved from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) database. These mutations were annotated utilizing the COVID-19 Annotation tool (

http://giorgilab. unibo.it/coronannotator/) [

14] for comparison with mutations identified in the study

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing Data

The sequencing information from the set of 44 SARS-CoV-2 sequenced samples had an average of base coverage of 95%. Each base on average had a coverage depth of 282.73, with a maximum coverage depth reaching up to 1031.16. The sequences were deposited in GISAID and published with the accession numbers EPI_ISL_19004000 to EPI_ISL_19004016 and EPI_ISL_19004981 to EPI_ISL_19005007.

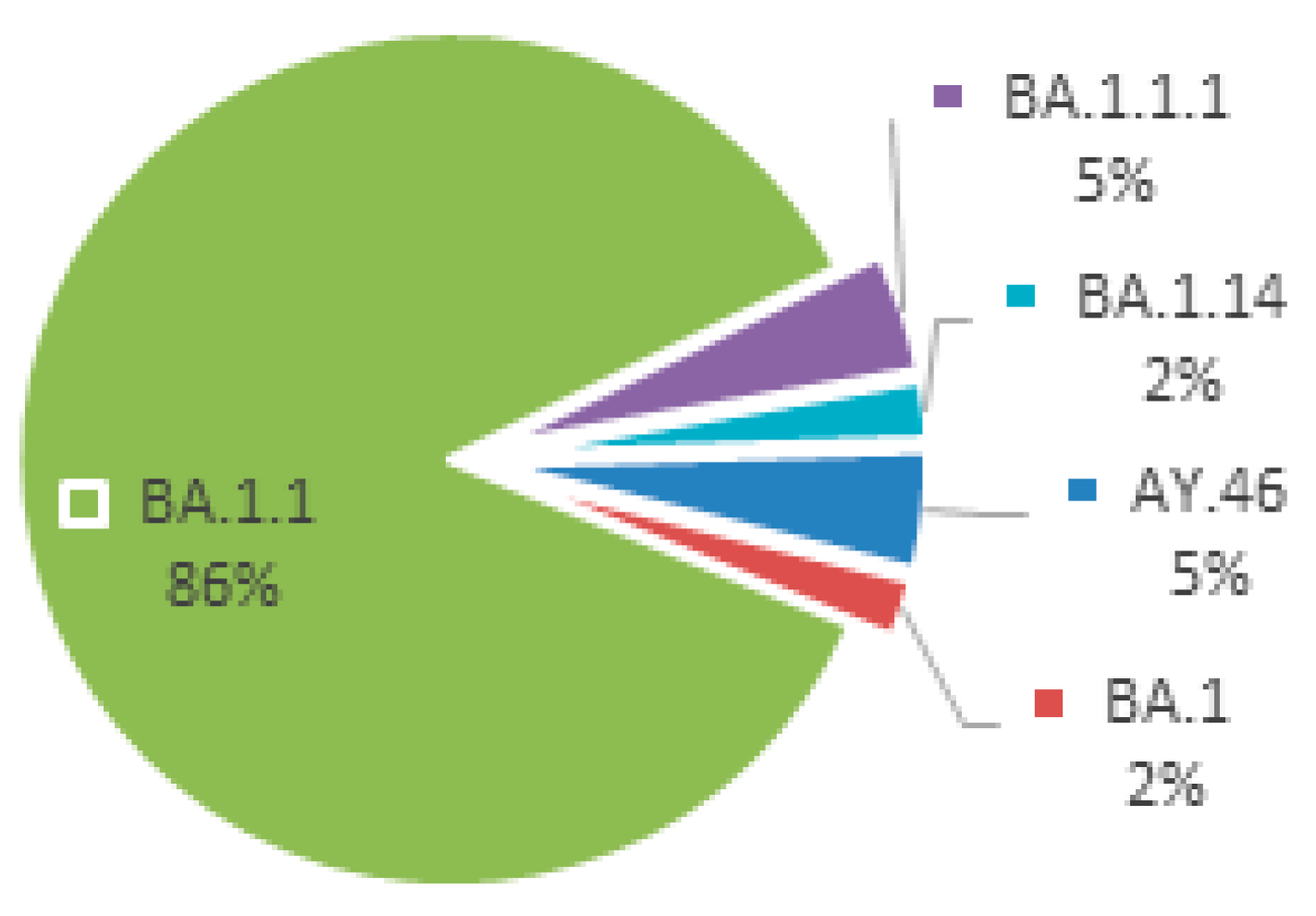

3.2. Variants of Concern

The sequencing outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 encompassed a cohort of 44 samples. Notably, the genomic analysis revealed the presence of two variants of concern: Delta (2 samples) and Omicron (42 samples). Within the Omicron variant, a nuanced genetic diversity was observed, with four discernible clades denoted as BA.1, BA.1.1, BA.1.1.1, and BA.1.14. Noteworthy is the dominance of the BA.1.1 clade, constituting a substantial majority at 86.4% of the total sequenced samples. These detailed genetic insights are graphically depicted in

Figure 2, providing a comprehensive visual representation of the intricate distribution and prevalence of identified SARS-CoV-2 variants and their respective clades within the examined dataset.

As illustrated in

Table 1, a comprehensive examination of genomic variations within distinct regions of the genome, unveiled varying percentages of mutated sequences.

In the 5'UTR region at reference position 241, a substitution from C to T occurred, resulting in a mutated sequence at position 241 (5'UTR: 241) with a mutation rate of 34.2%. Moving to the NSP2 region (reference position 2470), a C to T substitution at this position led to the variant A555A, presenting a mutation rate of 21.1%. Within the NSP3 region, specific mutations such as NSP3:F106F, NSP3:A889A, NSP3:S1265 and NSP3:A1892T exhibited a 100.0% mutation rate, indicating substantial variations in these regions. The NSP4 region, particularly at reference position 10029, demonstrated the mutation T492I with a 100.0% mutation rate. Regarding the NSP6 region, deletions at positions L105 and I189V were reported, each showing a 100.0% mutation rate. Moving through NSP10, NSP12b, NSP13, NSP14, NSP15, ORF3a, E, M, ORF6, ORF7b, 3'UTR, and Nucleocapsid proteins, multiple mutations were observed with a consistent 100.0% mutation rate. In the Spike protein region (reference positions 21762 to 24503), S:A67, S:A67, S:I68, S:T95I, S:G142 mutations were 100.0%, in addition, specific positions S:T547K, S:D614G, S:H655Y, S:N679K, S:P681H, S:N764K, S:D796Y, S:N856K, S:Q954H, S:N969K, S:L981F and S:D1146D, exhibiting a complete mutation rate. For the ORF7b region at reference position 27807, the L17L mutation was detected with a 71.1% mutation rate. From the 3'UTR region at reference position 28271 to the Nucleocapsid protein region at 28881, a 100.0% mutation rate was observed, indicating pervasive variations in these genomic segments.

3.3. Frequency of Mutations in the Population

In protein NSP1, mutation N178S was observed as having a frequency of 2.3%. There were also mutations in NSP2 such as N9N, S36N, D40Y, H194N and others with this same mutation occurrence. Likewise, NSP3 had K38R; D136G and Y317H among other such changes which all occurred at 2.3% frequency. The same was true for NSP4 since it displayed V30G; V258A and T265I among others at 2.3% rate. Meanwhile, NSP9, NSP12b, NSP13 and NSP14 exhibited similar mutations but donned on diverse positions yet they all had a mutation frequency of 2.3%. Moreover, there were several mutations that were detected at higher rates of mutation too. One example is the presence of these mutations A488S or P1228L in protein NSP3 with a frequency of 4.5%. The same was true for the two other proteins namely nsps 4 muts D144D/V167L as shown in the

Table A2.

Likewise, in case of nsps6 which gave rise to A2V/T77A/and V120V alterations with a gene change rate of 4.5% on each one. Additionally, nsp12b/nsp13/orf7a/orf8 displayed similar percentage frequencies. As noted before there are different levels or percentages when it comes to nsp3/s protein/other proteins. Furthermore, some other set of mutations had a greater prevalence. For example in the s-protein we have seen cases where S477N/N501Y/Y505H etc were recorded between 36-38% differently. The spike protein mutations include N440K; G446S; T478K; and E484A which were found to have frequencies of 40.9-43.2% in S protein. Likewise, there were also mutations with significantly higher mutation rates like R346K and G339D in the spike protein that had a percentage of 81.8% and 84.1%, respectively. Moreover, the D614G variant in the spike protein showed a total mutation rate of 100%.

3.4. Emerging Mutations

Each novel mutation is listed along with its corresponding percentage of cases within the study cohort, as well as its occurrence in five distinct waves (wave1 through wave5). The first mutation, S:R214R, is notable for its prevalence, accounting for 43.2% of cases within the study. However, intriguingly, this mutation has not been observed in any of the waves examined, suggesting its emergence may be specific to the study cohort. The second mutation, NSP2:A555A, is identified in 18.2% of cases in the study group. While absent in the earlier waves (wave 1 to wave 4), it makes a notable appearance in wave 5, albeit representing a minor fraction (0.6%) of cases. The third mutation represents a complex combination of mutations affecting various viral proteins, as delineated extensively. Despite its complexity, this mutation pattern is relatively rare, comprising only 2.3% of cases within the study. Similar to the previous mutations, it is conspicuously absent in earlier waves but manifests exclusively in wave 5.

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of recently identified mutations found within the study population, offering insights into their prevalence and distribution across multiple waves of cases.

4. Discussion

The analysis of mutations across different clades of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have yielded intriguing findings regarding the varying numbers of mutated bases. When considering the clades that were examined, it was observed that the clade BA.1.1 exhibited the highest number of mutations, specifically 122 mutations. Following closely behind, the clade BA.1.1.1 displayed 61 mutations. In stark contrast, the clade BA.1 presented the least number of mutations, with only 34. Additionally, the clades AY.46 and BA.1.14 had 44 and 41 mutations, respectively, thus further contributing to the overall understanding of the distribution of mutations within different clades.

In the beginning of the pandemic, the B.1 global parental lineage, present since the outset of the outbreak in the country, held sway, constituting 94% of all genomes in the first wave and 71% in the second wave. As the second wave progressed into the third wave, a variety of virus strains emerged, encompassing both Variants of Concern (VoCs) like B.1.351 (Beta) and B.1.1.7 (Alpha), as well as non-VoCs including B.1.3x, B.1.5x, B.1.525 (Eta), A, and A.23x. However, by the midpoint of the third wave, the Alpha variant took center stage, representing 74.9% of all sequenced genomes. The B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant and its AY.x sub-variant were identified in March 2021, rapidly surpassing other variants to become the predominant strain (99.3% of sequenced genomes) during forth wave [

10]. This is study that was conducted during the fifth wave was dominated with clade BA.1.1 which is a subvariant BA.1, the clade that was dominant in the country during this wave.

This particular observation aligns with previous studies that have emphasized the presence of distinct clades harboring specific mutations. It has been demonstrated that these mutations, such as the D614G mutation, play a significant role in enhancing the infectiousness of the virus when compared to the original strains [

15].

Extensive research efforts have revealed that these clades underwent evolutionary changes during the early stages of the pandemic and have subsequently disseminated across different geographical regions, thereby contributing to the global burden of COVID-19 [

16]. This genetic analysis encompasses a wide range of genes, including 3'UTR, 5'UTR, E, M, N, NSP10, NSP12b, NSP13, NSP14, NSP15, NSP16, NSP1, NSP2, NSP3, NSP4, NSP6, NSP9, ORF3a, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF7b, ORF8, and S. By focusing on these essential genes, researchers have been able to shed light on the significance of viral proteins and their intricate interactions with the host cellular pathways. It is noteworthy that coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, have demonstrated their ability to neutralize and exploit cellular pathways such as autophagy, which serve as critical support systems for their replication and overall life cycle [

17]. Furthermore, the examination of mutations in various viral genes has revealed the existence of epistasis, highlighting the delicate and complex interactions that significantly influence the evolutionary trajectory and pathogenicity of the virus [

18]. It is also worth mentioning that investigations into the mutations present in different SARS-CoV-2 variants have uncovered distinct changes unique to each clade. For instance, in the case of the omicron subvariants BA.2 and BA.4, distinctive mutation patterns have been observed in genes such as ORF6, ORF7b, and NSP1, thereby underscoring the profound genetic diversity within this virus (Liang, 2023). Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of these mutations is of paramount importance for effective monitoring of the virus's evolution and for the development of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that can effectively mitigate the impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In conclusion, the genetic analysis of different SARS-CoV-2 clades and their corresponding mutations across a wide range of genes presents an extraordinary opportunity to gain valuable insights into the intricate evolutionary dynamics and remarkable diversity exhibited by this viral pathogen. By exploring the intricate interactions between viral proteins and host cellular pathways, as well as the effects of mutations on different clades, researchers can significantly enhance their comprehension of the complex nature of SARS-CoV-2 and contribute to the development of evidence-based public health responses aimed at effectively managing the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The most abundant novel mutation is S: R214R, a synonymous mutation, which account for 43.2% and of cases within the study. Synonymous mutations in SARS-CoV-2 have been found to be functionally and evolutionarily significant. In the past, synonymous mutations were viewed as phenotypically silent but recent studies indicate they can affect viral fitness with potential functional associations [

19,

20]. These types of mutations may alter RNA secondary structure leading to a higher probability of base pairing [

21]. Moreover, there is a different frequency and regularity of mutations in various SARS-CoV-2 genes, where some genes have more non-synonymous mutations than others [

22]. Better controlling pandemic requires an understanding of the impact of synonymous mutation on treatment and vaccine development vaccines [

23]. Using millions of publicly accessible SARS-CoV-2 sequences could allow estimation of mutation effects which can provide crucial details for the assessment therapeutics that would be impervious to escape from newly derived variants. NSP2:A555A is not entirely a novel mutation but is notable. Other novel mutations were seen in low frequency and further research in the region may be required to ascertain their dominance.

5. Conclusion

The emergence of novel mutations and variants of SARS-CoV-2 has posed significant challenges in the global battle against the COVID-19 pandemic. These mutations, particularly those affecting the spike gene, have far-reaching implications for various aspects of the pandemic response, including transmission dynamics, vaccine efficacy, and disease severity. Variants such as Alpha, Delta, and Omicron underscore the need for continuous monitoring and international collaboration to effectively combat the spread of the virus.

To understand the genetic landscape of SARS-CoV-2, comprehensive genomic analyses are imperative. Patient swab samples are collected, preserved, and analyzed using advanced molecular techniques like RT-PCR and sequencing. Bioinformatic tools aid in the interpretation of sequencing data, allowing for the identification of novel mutations and variants. This holistic approach provides valuable insights into the virus's evolution and informs public health strategies to mitigate its impact.

The study of 44 SARS-CoV-2 samples revealed the presence of Delta and Omicron variants, with Omicron exhibiting genetic diversity across clades. Detailed genomic analyses uncovered mutations across various regions of the genome, with some mutations showing higher prevalence rates, such as those in the spike protein. Notably, synonymous mutations like S:R214R and NSP2:A555A, exhibit distinct patterns of emergence, appearing exclusively in this study. Synonymous mutations, once considered phenotypically silent, are now recognized for their potential impact on viral fitness and RNA secondary structure. Understanding the functional significance of these mutations is crucial for developing effective therapeutics and vaccines resistant to emerging variants.

In conclusion, the ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 underscores the need for vigilant surveillance, research, and international cooperation. By continuously monitoring the genetic landscape of the virus and understanding the implications of novel mutations, we can better adapt our public health strategies to control the spread of COVID-19 and mitigate its impact on global health and society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Elius Mbogori, and Stanslaus Musyoki; methodology, Elius Mbogori, Richard Biegon; software, Harrison Yunying Deng.; validation, Binhua Liang and Elijah Songok; formal analysis, Elius Mbogori; investigation, Elius Mbogori, Caroline Gikunyu, Winfrida Cheriro, Kelvin Thion’go and Damaris Matoke-Muhia.; resources, Elijah Songok; data curation, Elius Mbogori, Caroline Gikunyu, and Binhua Liang;. writing—original draft preparation, Elius Mbogori.; writing—review and editing, Elijah Songok, Stanslaus Musyoki, Kirtika Patel, Richard Biegon and Binhua Liang.; visualization, Elius Mbogori.; supervision, Kirtika Patel, Richard Biegon and Elijah Songok; project administration, Elius Mbogori and Elijah Songok.; funding acquisition, Elijah Songok. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sequencing data and Clade for each genome.

Table A1.

Sequencing data and Clade for each genome.

| Sequence Name |

Lineage |

Bases with coverage |

Average coverage depth |

Maximum coverage depth |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME008_MTRH_S13/2021 |

AY.46 |

97.8 |

265.6 |

1000 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME026_MTRH_S37/2021 |

AY.46 |

93.6 |

36.5 |

142 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME028a_MTRH_S7/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

82.6 |

28.7 |

247 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME029_MTRH_S49/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.1 |

386.4 |

1222 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME030_MTRH_S61/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

91.4 |

74.5 |

414 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME036_MTRH_S85/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

98.4 |

514.8 |

1510 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME037_MTRH_S2/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.78 |

427.7 |

1.175 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME038_MTRH_S14/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

97.9 |

167.4 |

609 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME039_MTRH_S26/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

86.4 |

32.7 |

177 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME041_MTRH_S38/2021 |

BA.1.1.1 |

99.8 |

524.3 |

1572 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME042_MTRH_S50/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

87.9 |

41.9 |

239 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME043_MTRH_S62/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

97.8 |

196.2 |

684 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME045_MTRH_S74/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.2 |

489.8 |

1519 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME047_MTRH_S86/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

97.4 |

431.7 |

1325 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME048_MTRH_S3/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

96.25 |

71.23 |

290 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME066_MTRH_S15/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

95.6 |

120.8 |

461 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME071_MTRH_S27/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

95 |

113 |

502 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME072_MTRH_S39/2021 |

BA.1.1.1 |

90.6 |

40.7 |

220 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME077_MTRH_S51/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

95.7 |

200.9 |

1041 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME078_MTRH_S63/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

96.3 |

382.7 |

2277 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME091_MTRH_S75/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

98.6 |

404.9 |

1438 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME092_MTRH_S87/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.8 |

2283.2 |

6175 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME093_MTRH_S4/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

98.9 |

613.3 |

2358 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME095_MTRH_S16/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.8 |

342.3 |

1298 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME099_MTRH_S28/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

93.3 |

99.4 |

609 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME103_MTRH_S52/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

90.6 |

98.9 |

610 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME106_MTRH_S64/2021 |

BA.1.14 |

83.5 |

77.3 |

898 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME108_MTRH_S76/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

95.6 |

378.8 |

2055 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME109_MTRH_S88/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.4 |

854.9 |

2741 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME110_MTRH_S5/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

87.8 |

36.6 |

200 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME112_MTRH_S17/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.7 |

606.6 |

1817 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME116_MTRH_S41/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

95.9 |

437.4 |

2126 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME117_MTRH_S53/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

97.4 |

122.9 |

395 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME118_MTRH_S65/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

91 |

43.8 |

192 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME119_MTRH_S77/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

90.7 |

124.2 |

887 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME123_MTRH_S6/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

95.8 |

110.2 |

612 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME124_MTRH_S18/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.2 |

228.4 |

623 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME125_MTRH_S29/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

98.2 |

106.6 |

365 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME126_MTRH_S30/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

90.1 |

171.6 |

1453 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME127_MTRH_S42/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.4 |

340 |

1031 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME128_MTRH_S54/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

99.2 |

197.4 |

657 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME133_MTRH_S66/2021 |

BA.1 |

75.5 |

14 |

90 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME135_MTRH_S78/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

92.7 |

110.8 |

807 |

| hCoV-19/Kenya/SME137_MTRH_S90/2021 |

BA.1.1 |

93.4 |

89.3 |

482 |

Table A2.

Mutation frequency for each mutated position in Percentage.

Table A2.

Mutation frequency for each mutated position in Percentage.

| Ref pos |

Protein |

Ref var |

Q var |

Variant |

Var name |

Mutation frequency in Percentage |

| 241 |

5'UTR |

C |

T |

241 |

5'UTR:241 |

31.8 |

| 798 |

NSP1 |

A |

G |

N178S |

NSP1:N178S |

2.3 |

| 832 |

NSP2 |

C |

T |

N9N |

NSP2:N9N |

2.3 |

| 910 |

NSP2 |

GTC |

AAA |

S36N |

NSP2:S36N |

2.3 |

| 923 |

NSP2 |

G |

T |

D40Y |

NSP2:D40Y |

2.3 |

| 1385 |

NSP2 |

C |

A |

H194N |

NSP2:H194N |

2.3 |

| 1987 |

NSP2 |

A |

. |

S394 |

NSP2:S394 |

2.3 |

| 2470 |

NSP2 |

C |

T |

A555A |

NSP2:A555A |

18.2 |

| 2832 |

NSP3 |

A |

G |

K38R |

NSP3:K38R |

2.3 |

| 3037 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

F106F |

NSP3:F106F |

97.7 |

| 3126 |

NSP3 |

A |

G |

D136G |

NSP3:D136G |

2.3 |

| 3668 |

NSP3 |

T |

C |

Y317H |

NSP3:Y317H |

2.3 |

| 3685 |

NSP3 |

G |

T |

Q322H |

NSP3:Q322H |

2.3 |

| 3695 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

V325V |

NSP3:V325V |

2.3 |

| 3869 |

NSP3 |

A |

G |

K384E |

NSP3:K384E |

2.3 |

| 3881 |

NSP3 |

A |

C |

I388L |

NSP3:I388L |

11.4 |

| 4181 |

NSP3 |

G |

T |

A488S |

NSP3:A488S |

4.5 |

| 4795 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

S692S |

NSP3:S692S |

2.3 |

| 4800 |

NSP3 |

A |

G |

K694R |

NSP3:K694R |

2.3 |

| 5017 |

NSP3 |

G |

. |

V766 |

NSP3:V766 |

2.3 |

| 5020 |

NSP3 |

C |

G |

D767E |

NSP3:D767E |

2.3 |

| 5023 |

NSP3 |

GT |

CG |

MS768IA |

NSP3:MS768IA |

2.3 |

| 5028 |

NSP3 |

T |

. |

M770 |

NSP3:M770 |

2.3 |

| 5260 |

NSP3 |

TT |

AG |

S848A |

NSP3:S848A |

2.3 |

| 5299 |

NSP3 |

T |

A |

T860T |

NSP3:T860T |

2.3 |

| 5339 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

P874S |

NSP3:P874S |

2.3 |

| 5365 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

Y882Y |

NSP3:Y882Y |

2.3 |

| 5386 |

NSP3 |

T |

G |

A889A |

NSP3:A889A |

95.5 |

| 5602 |

NSP3 |

T |

C |

F961F |

NSP3:F961F |

2.3 |

| 6402 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

P1228L |

NSP3:P1228L |

4.5 |

| 6513 |

NSP3 |

GTT |

. |

S1265 |

NSP3:S1265 |

95.5 |

| 6589 |

NSP3 |

G |

T |

K1290N |

NSP3:K1290N |

2.3 |

| 7119 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

S1467F |

NSP3:S1467F |

2.3 |

| 7124 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

P1469S |

NSP3:P1469S |

2.3 |

| 7256 |

NSP3 |

T |

C |

Y1513H |

NSP3:Y1513H |

2.3 |

| 8293 |

NSP3 |

C |

A |

T1858T |

NSP3:T1858T |

2.3 |

| 8393 |

NSP3 |

G |

A |

A1892T |

NSP3:A1892T |

95.5 |

| 8476 |

NSP3 |

C |

T |

N1919N |

NSP3:N1919N |

2.3 |

| 8643 |

NSP4 |

T |

G |

V30G |

NSP4:V30G |

2.3 |

| 8986 |

NSP4 |

C |

T |

D144D |

NSP4:D144D |

4.5 |

| 9053 |

NSP4 |

G |

T |

V167L |

NSP4:V167L |

4.5 |

| 9327 |

NSP4 |

T |

C |

V258A |

NSP4:V258A |

2.3 |

| 9348 |

NSP4 |

C |

T |

T265I |

NSP4:T265I |

2.3 |

| 9397 |

NSP4 |

A |

G |

S281S |

NSP4:S281S |

2.3 |

| 9808 |

NSP4 |

C |

T |

C418C |

NSP4:C418C |

2.3 |

| 10029 |

NSP4 |

C |

T |

T492I |

NSP4:T492I |

97.7 |

| 10977 |

NSP6 |

C |

T |

A2V |

NSP6:A2V |

4.5 |

| 11201 |

NSP6 |

A |

G |

T77A |

NSP6:T77A |

4.5 |

| 11286 |

NSP6 |

TGTCTGGTT |

. |

L105 |

NSP6:L105 |

95.5 |

| 11332 |

NSP6 |

A |

G |

V120V |

NSP6:V120V |

4.5 |

| 11537 |

NSP6 |

A |

G |

I189V |

NSP6:I189V |

95.5 |

| 12786 |

NSP9 |

C |

T |

T34I |

NSP9:T34I |

2.3 |

| 13195 |

NSP10 |

T |

C |

V57V |

NSP10:V57V |

95.5 |

| 13879 |

NSP12b |

G |

A |

V138I |

NSP12b:V138I |

2.3 |

| 14408 |

NSP12b |

C |

T |

P314L |

NSP12b:P314L |

100.0 |

| 15240 |

NSP12b |

C |

T |

N591N |

NSP12b:N591N |

11.4 |

| 15426 |

NSP12b |

A |

G |

V653V |

NSP12b:V653V |

2.3 |

| 15451 |

NSP12b |

G |

A |

G662S |

NSP12b:G662S |

4.5 |

| 15982 |

NSP12b |

G |

A |

V839I |

NSP12b:V839I |

2.3 |

| 16064 |

NSP12b |

A |

G |

Q866R |

NSP12b:Q866R |

4.5 |

| 16466 |

NSP13 |

C |

T |

P77L |

NSP13:P77L |

4.5 |

| 16744 |

NSP13 |

G |

A |

G170S |

NSP13:G170S |

63.6 |

| 16752 |

NSP13 |

T |

C |

P172P |

NSP13:P172P |

2.3 |

| 16759 |

NSP13 |

C |

A |

P175T |

NSP13:P175T |

2.3 |

| 18163 |

NSP14 |

A |

G |

I42V |

NSP14:I42V |

95.5 |

| 18866 |

NSP14 |

T |

C |

M276T |

NSP14:M276T |

2.3 |

| 19220 |

NSP14 |

C |

T |

A394V |

NSP14:A394V |

4.5 |

| 19240 |

NSP14 |

TTT |

GGG |

F401G |

NSP14:F401G |

2.3 |

| 19327 |

NSP14 |

G |

C |

A430P |

NSP14:A430P |

2.3 |

| 19698 |

NSP15 |

C |

A |

I26I |

NSP15:I26I |

2.3 |

| 19961 |

NSP15 |

C |

T |

T114M |

NSP15:T114M |

2.3 |

| 20016 |

NSP15 |

C |

A |

D132E |

NSP15:D132E |

2.3 |

| 21384 |

NSP16 |

T |

C |

Y242Y |

NSP16:Y242Y |

2.3 |

| 21618 |

S |

C |

G |

T19R |

S:T19R |

2.3 |

| 21762 |

S |

C |

. |

A67 |

S:A67 |

95.5 |

| 21764 |

S |

A |

. |

A67 |

S:A67 |

95.5 |

| 21767 |

S |

CATG |

. |

I68 |

S:I68 |

95.5 |

| 21846 |

S |

C |

T |

T95I |

S:T95I |

95.5 |

| 21987 |

S |

GTGTTTATT |

. |

G142 |

S:G142 |

95.5 |

| 22029 |

S |

AGTTCA |

. |

E156 |

S:E156 |

4.5 |

| 22039 |

S |

TT |

AC |

Y160H |

S:Y160H |

2.3 |

| 22193 |

S |

. |

T |

I210 |

S:I210 |

43.2 |

| 22194 |

S |

ATT |

. |

N211 |

S:N211 |

2.3 |

| 22195 |

S |

T |

G |

N211K |

S:N211K |

43.2 |

| 22197 |

S |

TA |

GC |

L212C |

S:L212C |

43.2 |

| 22201 |

S |

. |

AGC |

S214 |

S:S214 |

43.2 |

| 22202 |

S |

. |

A |

V213 |

S:V213 |

43.2 |

| 22203 |

S |

. |

A |

R214 |

S:R214 |

43.2 |

| 22204 |

S |

. |

AGAA |

R214 |

S:R214 |

2.3 |

| 22204 |

S |

. |

GA |

R214 |

S:R214 |

2.3 |

| 22204 |

S |

T |

A |

R214R |

S:R214R |

43.2 |

| 22261 |

S |

TA |

CT |

N234Y |

S:N234Y |

2.3 |

| 22434 |

S |

G |

A |

C291Y |

S:C291Y |

2.3 |

| 22578 |

S |

G |

A |

G339D |

S:G339D |

84.1 |

| 22599 |

S |

G |

A |

R346K |

S:R346K |

81.8 |

| 22673 |

S |

TC |

CT |

S371L |

S:S371L |

22.7 |

| 22679 |

S |

T |

C |

S373P |

S:S373P |

22.7 |

| 22686 |

S |

C |

T |

S375F |

S:S375F |

22.7 |

| 22813 |

S |

G |

T |

K417N |

S:K417N |

6.8 |

| 22882 |

S |

T |

G |

N440K |

S:N440K |

40.9 |

| 22898 |

S |

G |

A |

G446S |

S:G446S |

40.9 |

| 22917 |

S |

T |

G |

L452R |

S:L452R |

4.5 |

| 22927 |

S |

G |

A |

L455L |

S:L455L |

2.3 |

| 22992 |

S |

G |

A |

S477N |

S:S477N |

36.4 |

| 22995 |

S |

C |

A |

T478K |

S:T478K |

40.9 |

| 23013 |

S |

A |

C |

E484A |

S:E484A |

40.9 |

| 23040 |

S |

A |

G |

Q493R |

S:Q493R |

38.6 |

| 23048 |

S |

G |

A |

G496S |

S:G496S |

38.6 |

| 23055 |

S |

A |

G |

Q498R |

S:Q498R |

38.6 |

| 23063 |

S |

A |

T |

N501Y |

S:N501Y |

36.4 |

| 23075 |

S |

T |

C |

Y505H |

S:Y505H |

36.4 |

| 23121 |

S |

C |

A |

A520E |

S:A520E |

2.3 |

| 23202 |

S |

C |

A |

T547K |

S:T547K |

95.5 |

| 23383 |

S |

G |

T |

Q607H |

S:Q607H |

2.3 |

| 23403 |

S |

A |

G |

D614G |

S:D614G |

100.0 |

| 23525 |

S |

C |

T |

H655Y |

S:H655Y |

95.5 |

| 23599 |

S |

T |

G |

N679K |

S:N679K |

95.5 |

| 23604 |

S |

C |

G |

P681R |

S:P681R |

4.5 |

| 23604 |

S |

C |

A |

P681H |

S:P681H |

95.5 |

| 23854 |

S |

C |

A |

N764K |

S:N764K |

86.4 |

| 23948 |

S |

G |

T |

D796Y |

S:D796Y |

90.9 |

| 24130 |

S |

C |

A |

N856K |

S:N856K |

95.5 |

| 24424 |

S |

A |

T |

Q954H |

S:Q954H |

95.5 |

| 24469 |

S |

T |

A |

N969K |

S:N969K |

95.5 |

| 24503 |

S |

C |

T |

L981F |

S:L981F |

95.5 |

| 25000 |

S |

C |

T |

D1146D |

S:D1146D |

95.5 |

| 25006 |

S |

C |

T |

F1148F |

S:F1148F |

2.3 |

| 25209 |

S |

T |

C |

I1216T |

S:I1216T |

2.3 |

| 25249 |

S |

G |

. |

M1229 |

S:M1229 |

2.3 |

| 25283 |

S |

T |

A |

C1241S |

S:C1241S |

2.3 |

| 25469 |

ORF3a |

C |

T |

S26L |

ORF3a:S26L |

4.5 |

| 25474 |

ORF3a |

T |

C |

F28L |

ORF3a:F28L |

2.3 |

| 25584 |

ORF3a |

C |

T |

T64T |

ORF3a:T64T |

95.5 |

| 25782 |

ORF3a |

C |

T |

C130C |

ORF3a:C130C |

4.5 |

| 25836 |

ORF3a |

C |

T |

C148C |

ORF3a:C148C |

2.3 |

| 25997 |

ORF3a |

T |

A |

V202E |

ORF3a:V202E |

2.3 |

| 26038 |

ORF3a |

T |

A |

S216T |

ORF3a:S216T |

2.3 |

| 26191 |

ORF3a |

C |

T |

P267S |

ORF3a:P267S |

2.3 |

| 26220 |

3'UTR |

A |

G |

26220 |

3'UTR:26220 |

2.3 |

| 26257 |

E |

G |

T |

V5F |

E:V5F |

2.3 |

| 26263 |

E |

G |

T |

E7* |

E:E7* |

2.3 |

| 26270 |

E |

C |

T |

T9I |

E:T9I |

88.6 |

| 26285 |

E |

T |

C |

V14A |

E:V14A |

2.3 |

| 26288 |

E |

. |

GT |

N15 |

E:N15 |

2.3 |

| 26577 |

M |

C |

G |

Q19E |

M:Q19E |

95.5 |

| 26601 |

M |

C |

T |

F26F |

M:F26F |

2.3 |

| 26709 |

M |

G |

A |

A63T |

M:A63T |

95.5 |

| 26767 |

M |

T |

C |

I82T |

M:I82T |

4.5 |

| 26828 |

M |

G |

T |

L102L |

M:L102L |

2.3 |

| 27092 |

M |

C |

T |

D190D |

M:D190D |

2.3 |

| 27259 |

ORF6 |

A |

C |

M19M |

ORF6:M19M |

95.5 |

| 27382 |

ORF6 |

GAT |

CTC |

D61L |

ORF6:D61L |

2.3 |

| 27465 |

ORF7a |

T |

C |

V24V |

ORF7a:V24V |

2.3 |

| 27494 |

ORF7a |

C |

T |

P34L |

ORF7a:P34L |

2.3 |

| 27624 |

ORF7a |

A |

. |

L77 |

ORF7a:L77 |

2.3 |

| 27638 |

ORF7a |

T |

C |

V82A |

ORF7a:V82A |

4.5 |

| 27675 |

ORF7a |

AGAACTTTACTCTCCAATT |

. |

Q94 |

ORF7a:Q94 |

2.3 |

| 27752 |

ORF7a |

C |

T |

T120I |

ORF7a:T120I |

4.5 |

| 27807 |

ORF7b |

C |

T |

L17L |

ORF7b:L17L |

61.4 |

| 27874 |

ORF7b |

C |

T |

T40I |

ORF7b:T40I |

4.5 |

| 28248 |

ORF8 |

GATTTC |

. |

D119 |

ORF8:D119 |

4.5 |

| 28271 |

3'UTR |

A |

T |

28271 |

3'UTR:28271 |

95.5 |

| 28273 |

3'UTR |

A |

. |

28273 |

3'UTR:28273 |

4.5 |

| 28311 |

N |

C |

T |

P13L |

N:P13L |

95.5 |

| 28362 |

N |

GAGAACGCA |

. |

E31 |

N:E31 |

95.5 |

| 28739 |

N |

G |

T |

A156S |

N:A156S |

2.3 |

| 28881 |

N |

G |

T |

R203M |

N:R203M |

4.5 |

| 28881 |

N |

GGG |

AAC |

RG203KR |

N:RG203KR |

95.5 |

| 28916 |

N |

G |

T |

G215C |

N:G215C |

4.5 |

| 29402 |

N |

G |

T |

D377Y |

N:D377Y |

4.5 |

| 29486 |

N |

A |

G |

K405E |

N:K405E |

2.3 |

| 29738 |

3'UTR |

C |

A |

29738 |

3'UTR:29738 |

2.3 |

| 29742 |

3'UTR |

G |

T |

29742 |

3'UTR:29742 |

4.5 |

References

- Johnson, B.A.; Zhou, Y.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Vu, M.N.; Bopp, N.E.; Crocquet-Valdes, P.A.; Kalveram, B.; Schindewolf, C.; Liu, Y.; Scharton, D.; et al. Nucleocapsid Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Augment Replication and Pathogenesis. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010627–e1010627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, M.; Xue, Y.; Dillen, C.A.; Oldfield, L.M.; Assad-Garcia, N.; Zaveri, J.; Singh, N.; Baracco, L.; Taylor, L.; Vashee, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Spike and Accessory Gene Mutations Alter Pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoter, A.; Naim, H.Y. Biochemical Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD Mutations and Their Impact on ACE2 Receptor Binding. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürzinger, H. Functional Mutations of SARS-CoV-2: Implications to Viral Transmission, Pathogenicity and Immune Escape. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 2022, 135, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.; Siddqui, G.; Sadhu, S.; Maithil, V.; Vishwakarma, P.; Lohiya, B.; Goswami, A.; Ahmed, S.; Awasthi, A.; Samal, S. Intrinsic D614G and P681R/H Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 VoCs Alpha, Delta, Omicron and Viruses with D614G plus Key Signature Mutations in Spike Protein Alters Fusogenicity and Infectivity. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2022, 212, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, L.; Baharani, V.A.; Schmidt, F.; Wang, Z.; Cho, A.; Raspe, R.; Guzman-Cardozo, C.; Muecksch, F.; Canis, M.; Park, D.J.; et al. Epistasis Lowers the Genetic Barrier to SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Escape. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemrajabi, M.; Calix, K.M.; Assis, R.C. de Epistasis-Driven Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Secondary Structure. J. Mol. Evol. 2022, 90, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, T.N.; Greaney, A.J.; Hannon, W.W.; Loes, A.N.; Hauser, K.; Dillen, J.; Ferri, E.; Farrell, A.G.; Dadonaite, B.; McCallum, M.; et al. Shifting Mutational Constraints in the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain during Viral Evolution. Science (80-. ). 2022, 377, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernando, franky okto; Simpson, A. Shifting Mutational Constraints in the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain during Viral Evolution. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nasimiyu, C.; Matoke-Muhia, D.; Rono, G.K.; Osoro, E.; Ouso, D.O.; Mwangi, J.M.; Mwikwabe, N.; Thiong’o, K.; Dawa, J.; Ngere, I.; et al. Imported SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern Drove Spread of Infections across Kenya during the Second Year of the Pandemic. COVID 2022, 2, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Wong, L.; Arora, P.; Zhang, L.; Rocha, C.; Odle, A.E.; Nehlmeier, I.; Kempf, A.; Richter, A.; Halwe, N.; et al. Omicron Subvariant BA.5 Efficiently Infects Lung Cells. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamohara, M.; Yagi, S.; Ishii, Y.; Nara, H. Tie2 NOVEL ANTI-HUMAN TIE-2 ANTIBODY. 2017.

- Richter, F.; Morton, S.U.; Qi, H.; Kitaygorodsky, A.; Wang, J.; Homsy, J.G.; DePalma, S.; Patel, N.; Gelb, B.D.; Seidman, J.G.; et al. Whole Genome De Novo Variant Identification with FreeBayes and Neural Network Approaches. bioRxiv Genomics 2020, 2020.03.24.994160. [CrossRef]

- Mercatelli, D.; Holding, A.N.; Giorgi, F.M. Web Tools to Fight Pandemics: The COVID-19 Experience. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaaswarkhanth, M.; Madhoun, A.A.; Al-Mulla, F. Could the D614G Substitution in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) Protein Be Associated With Higher COVID-19 Mortality? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, L.P.P.; Sathyaseelan, C.; Uttamrao, P.P.; Rathinavelan, T. Global Variation in SARS-CoV-2 Proteome and Its Implication in Pre-Lockdown Emergence and Dissemination of 5 Dominant SARS-CoV-2 Clades. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, A.; Nazarko, T.Y. The Molecular Interplay Between Human Coronaviruses and Autophagy. Cells 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Dichio, V.; Horta, E.R.; Thorell, K.; Aurell, E. Global Analysis of More Than 50,000 SARS-CoV-2 Genomes Reveals Epistasis Between Eight Viral Genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldivar-Espinoza, B.; Garcia-Segura, P.; Macip, G.; Puigbò, P.; Cereto-Massagué, A.; Pujadas, G.; Garcia-Vallvé, S. The Mutational Landscape of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renn, O. Synonymous Base Substitution in SARS-CoV-2 EE.2 Lineage Furin Arginine CGG–CGG Codons. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zeng, J.; Tang, K.; Long, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Xin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Sun, L.; et al. Variation in Synonymous Evolutionary Rates in the SARS-CoV-2 Genome. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, W.X.; Sia, B.Z.; Ng, C.H. Prediction of the Effects of the Top 10 Synonymous Mutations from 26645 SARS-CoV-2 Genomes. F1000Research 2022, 10, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, J.D.; Neher, R.A. Fitness Effects of Mutations to SARS-CoV-2 Proteins. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).