Submitted:

30 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects Selection

2.2. Ethical Implication

2.3. Isolation of RNA

2.4. Synthesis and Amplification of cDNA

2.5. Amplification of Tagmented Amplicons and Library Preparation

2.6. Loading of the Libraries to the MiSeq Flow Cell and Sequencer Running

2.7. Sequence Data Processing and Evaluation

2.8. Statistical Analysis and Graph Construction

3. Results

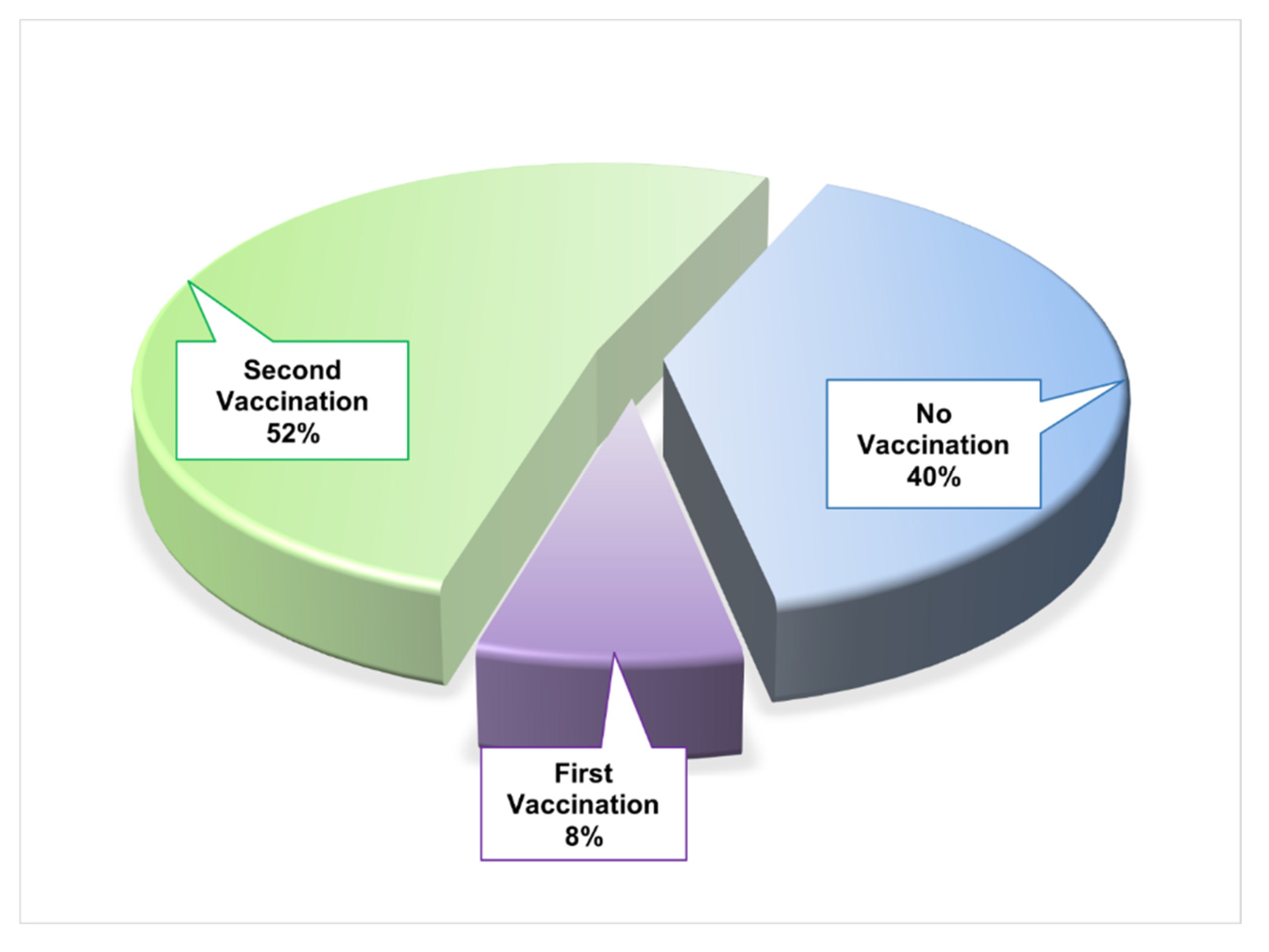

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Disease-Related Data of COVID-19 Patients

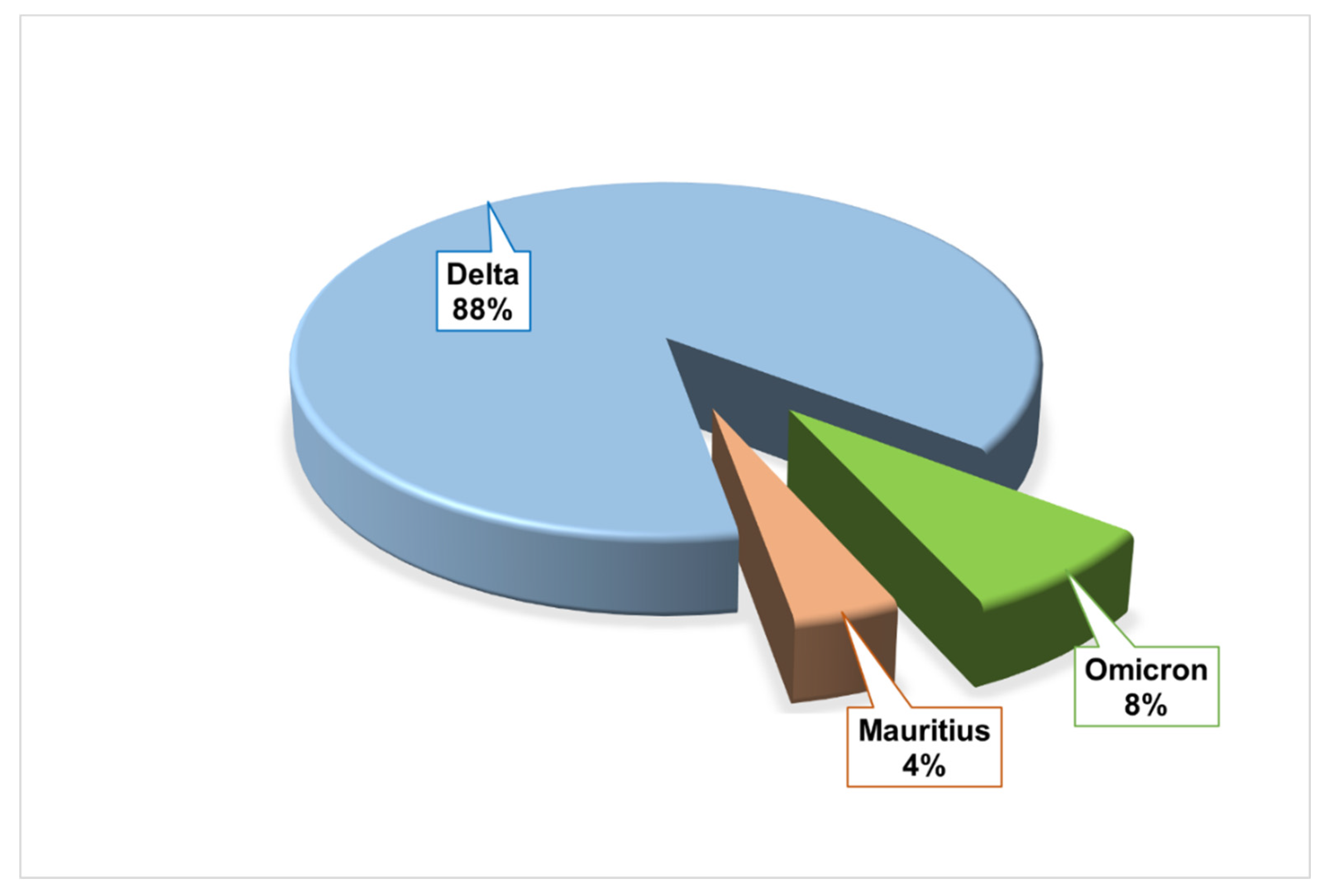

3.2. SARS-CoV-2 Variants, Clades and Lineage Evaluation

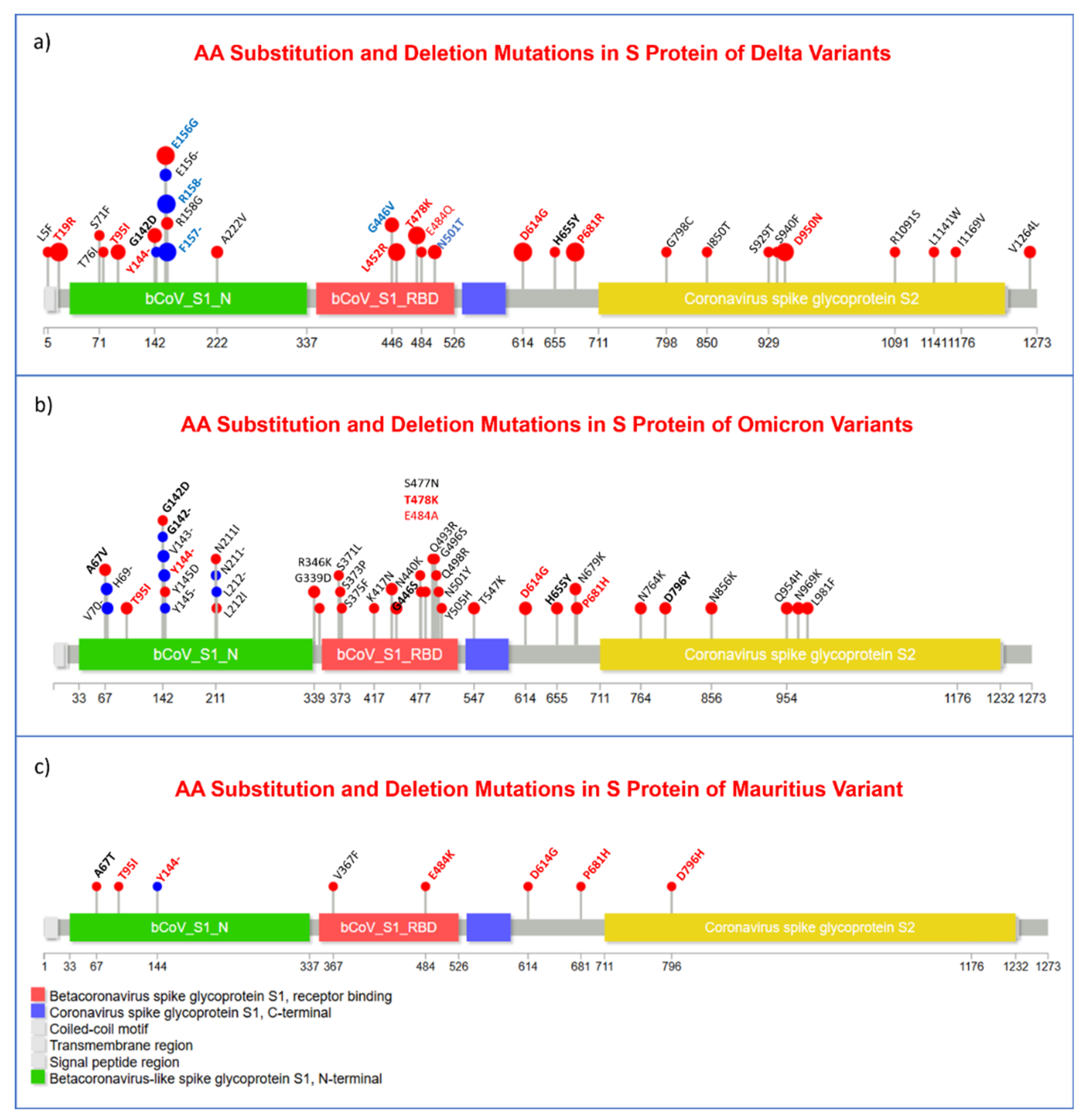

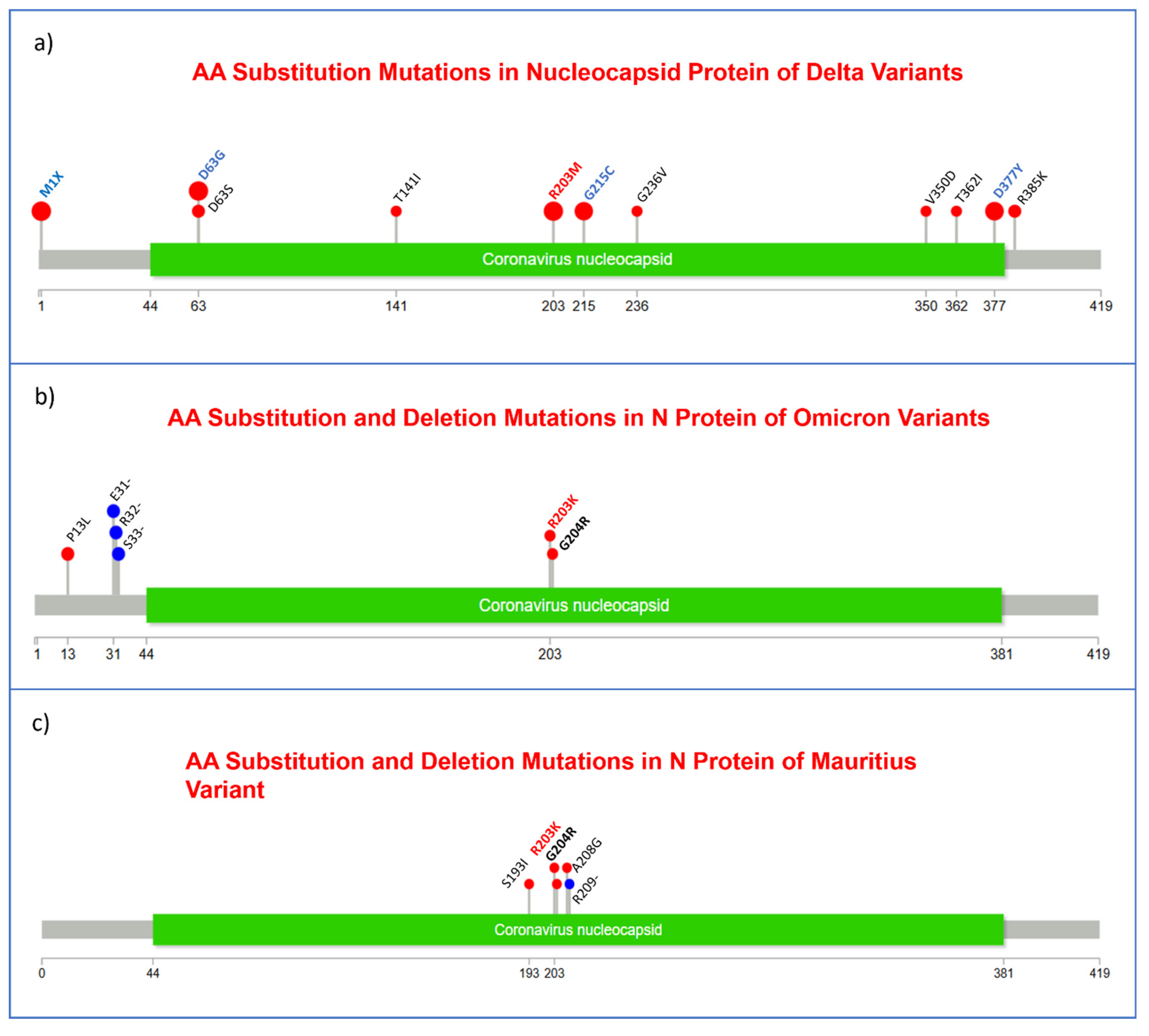

3.3. Substitution, and Insertion-Deletion Mutation Analysis

3.4. Comprehensive Investigation of Nucleotide Substitution Mutations

3.5. Extensive Analysis of Nucleotide Deletion Mutations

3.6. Detailed Evaluation of Insertion Mutations

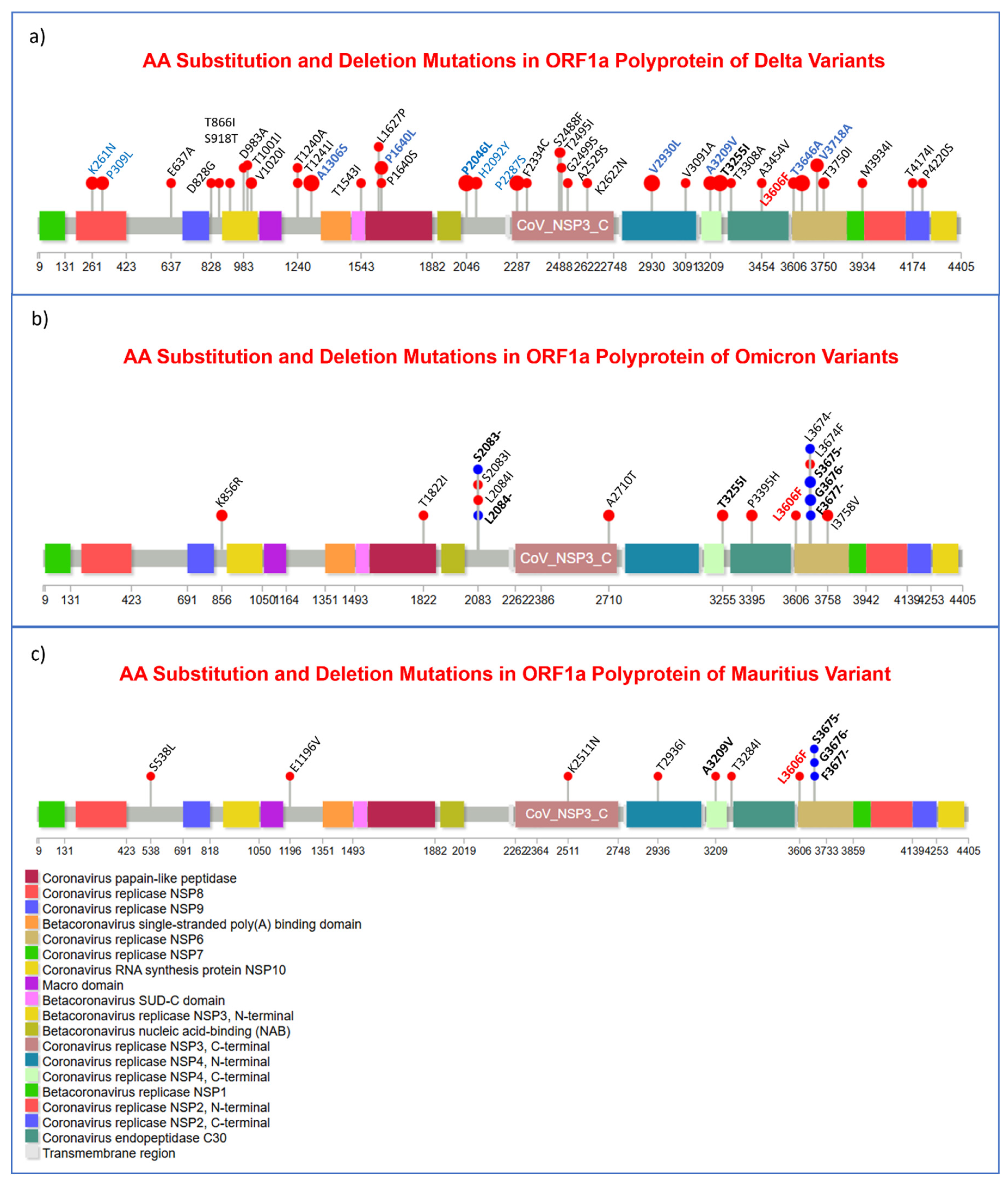

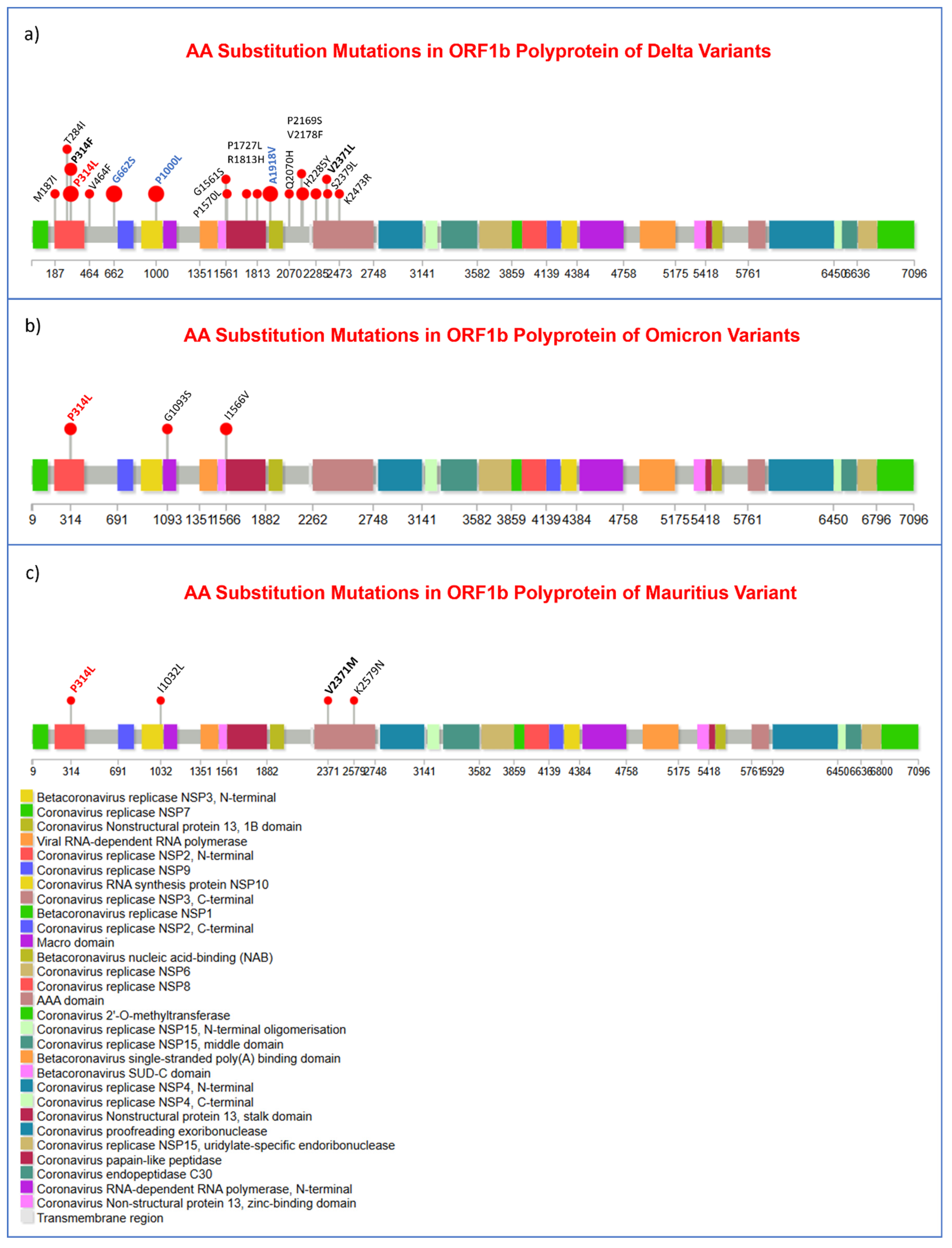

3.7. Missense Mutations Analysis in SARS-CoV-2 Viral Genome

3.8. Amino Acid Deletion Mutation Analysis

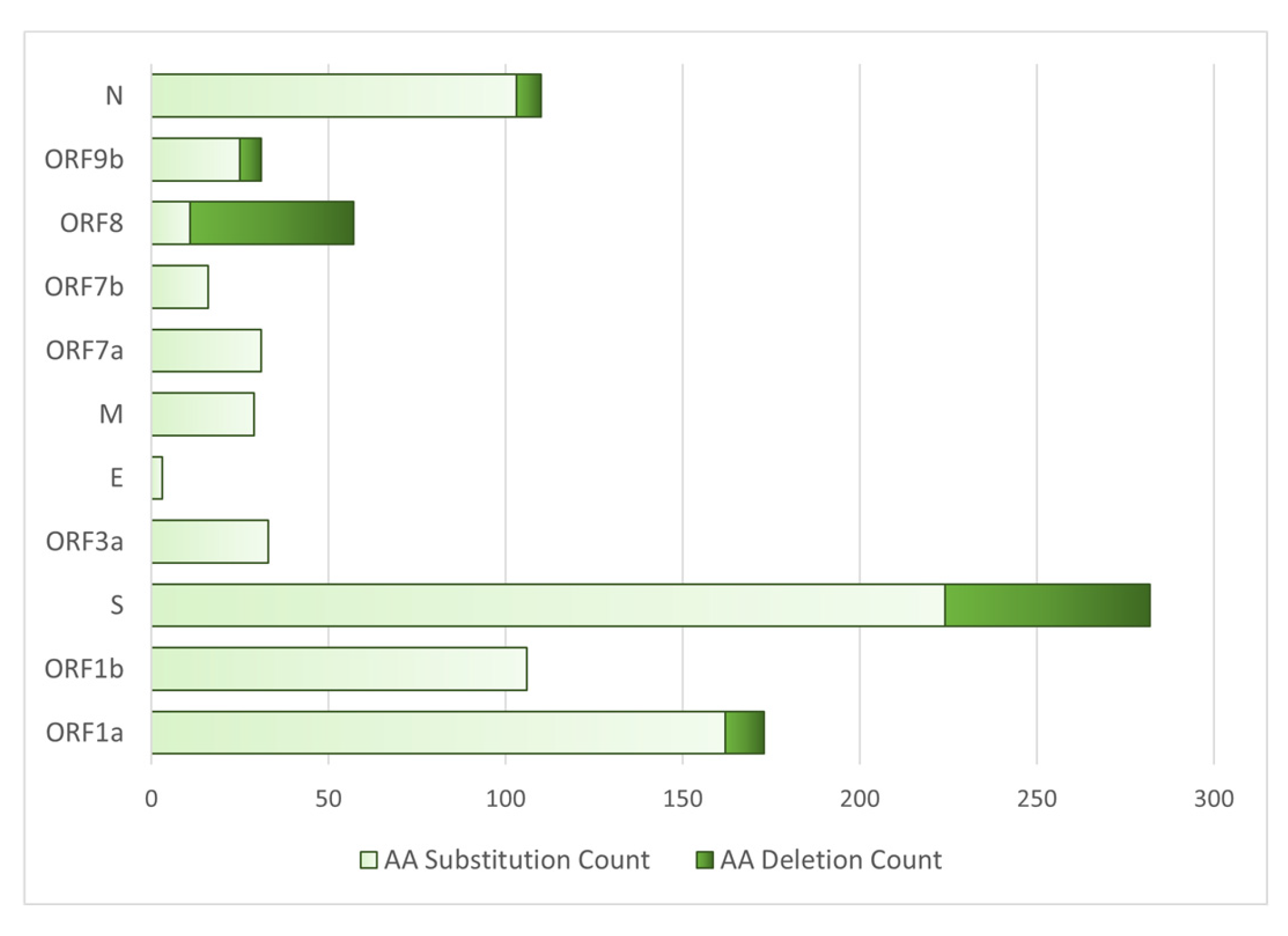

3.9. Proteins with the Highest Mutation Count

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, A.; Tiwari, S.; Deb, M. K.; Marty, J. L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): a global pandemic and treatment strategies. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, S. M.; Yu, X. H.; Tang, S. L.; Tang, C. K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): current status and future perspectives. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabutti, G.; d’Anchera, E.; Sandri, F.; Savio, M.; Stefanati, A. Coronavirus: update related to the current outbreak of COVID-19. Infectious diseases and therapy 2020, 9, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umakanthan, S.; Sahu, P.; Ranade, A. V.; Bukelo, M. M.; Rao, J. S.; Abrahao-Machado, L. F.; Dahal, S.; Kumar, H.; Kv, D. Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Postgrad Med J 2020, 96, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siam, M. H. B.; Hasan, M. M.; Tashrif, S. M.; Rahaman Khan, M. H.; Raheem, E.; Hossain, M. S. Insights into the first seven-months of COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: lessons learned from a high-risk country. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Dynamic Dashboard for Bangladesh. (DGHS), D. G. o. H. S., Ed.; 2024.

- Fehr, A. R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Coronaviruses: methods and protocols 2015, 1-23.

- Hartog, N.; Faber, W.; Frisch, A.; Bauss, J.; Bupp, C. P.; Rajasekaran, S.; Prokop, J. W. SARS-CoV-2 infection: molecular mechanisms of severe outcomes to suggest therapeutics. Expert review of proteomics 2021, 18, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J. K.; Whittaker, G. R. Host cell proteases: critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus research 2015, 202, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Shang, J.; Jiang, S.; Du, L. Subunit vaccines against emerging pathogenic human coronaviruses. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The lancet 2020, 395, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebuhr, J. Molecular biology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2004, 7, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlam, M.; Xu, Y.; Rao, Z. Structural proteomics of the SARS coronavirus: a model response to emerging infectious diseases. Journal of Structural and Functional Genomics 2007, 8, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Niu, Y.; Lou, Y.; Wang, H. The SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein biosynthesis, structure, function, and antigenicity: implications for the design of spike-based vaccine immunogens. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 576622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Yang, J.-S.; Kim, J. W.; Kim, V. N.; Chang, H. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome. Cell 2020, 181, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiao, G.; Chen, Y.; He, Y.; Niu, J.; Escalante, C. R.; Xiong, H.; Farmar, J.; Debnath, A. K.; Tien, P. Interaction between heptad repeat 1 and 2 regions in spike protein of SARS-associated coronavirus: implications for virus fusogenic mechanism and identification of fusion inhibitors. The Lancet 2004, 363, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Oton, J.; Qu, K.; Cortese, M.; Zila, V.; McKeane, L.; Nakane, T.; Zivanov, J.; Neufeldt, C. J.; Cerikan, B. Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions. Nature 2020, 588, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B. C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virology journal 2019, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lai, S.; Gao, G. F.; Shi, W. The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 600, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. C.; Chen, C. S.; Chan, Y. J. The outbreak of COVID-19: An overview. J Chin Med Assoc 2020, 83, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baz, S.; Draoui, A.; Echchakery, M.; del Rey, N. L.-G.; Chgoura, K. Spread of COVID-19 and Its Main Modes of Transmission. In Handbook of Research on Pathophysiology and Strategies for the Management of COVID-19, IGI Global, 2022; pp 78-95.

- Tang, B.; Bragazzi, N. L.; Li, Q.; Tang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, J. An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCov). Infectious disease modelling 2020, 5, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K. S.; Lau, E. H.; Wong, J. Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. New England journal of medicine 2020, 382, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Ruan, F.; Huang, M.; Liang, L.; Huang, H.; Hong, Z.; Yu, J.; Kang, M.; Song, Y.; Xia, J. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. New England journal of medicine 2020, 382, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). The indian journal of pediatrics 2020, 87, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raoult, D.; Zumla, A.; Locatelli, F.; Ippolito, G.; Kroemer, G. Coronavirus infections: Epidemiological, clinical and immunological features and hypotheses. Cell stress 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Du, C.; Zhang, Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA internal medicine 2020, 180, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymouri, M.; Mollazadeh, S.; Mortazavi, H.; Naderi Ghale-noie, Z.; Keyvani, V.; Aghababaei, F.; Hamblin, M. R.; Abbaszadeh-Goudarzi, G.; Pourghadamyari, H.; Hashemian, S. M. R.; et al. Recent advances and challenges of RT-PCR tests for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Pathology—Research and Practice 2021, 221, 153443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascola, J. R.; Graham, B. S.; Fauci, A. S. SARS-CoV-2 viral variants—tackling a moving target. Jama 2021, 325, 1261–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rella, S. A.; Kulikova, Y. A.; Dermitzakis, E. T.; Kondrashov, F. A. Rates of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and vaccination impact the fate of vaccine-resistant strains. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- for Immunization, N. C. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Infection-induced and Vaccine-induced Immunity. In CDC COVID-19 Science Briefs [Internet], Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), 2021.

- Forchette, L.; Sebastian, W.; Liu, T. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 virology, vaccines, variants, and therapeutics. Current medical science 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftekhar, E. N.; Priesemann, V.; Balling, R.; Bauer, S.; Beutels, P.; Valdez, A. C.; Cuschieri, S.; Czypionka, T.; Dumpis, U.; Glaab, E. A look into the future of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: an expert consultation. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLOS ONE 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, A.; Mirzazadeh, A.; Tavakolpour, S. Genetics and genomics of SARS-CoV-2: A review of the literature with the special focus on genetic diversity and SARS-CoV-2 genome detection. Genomics 2021, 113, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-w.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Ren, H.; Hu, P. Global genetic diversity patterns and transmissions of SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv 2020, 2020.2005. 2005.20091413.

- Rehman, S. U.; Shafique, L.; Ihsan, A.; Liu, Q. Evolutionary trajectory for the emergence of novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minskaia, E.; Hertzig, T.; Gorbalenya, A. E.; Campanacci, V.; Cambillau, C.; Canard, B.; Ziebuhr, J. Discovery of an RNA virus 3′→ 5′ exoribonuclease that is critically involved in coronavirus RNA synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 5108–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, E. Mechanisms of viral emergence. Veterinary research 2010, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.; Tantray, V. G.; Kirmani, A. R.; Ahangar, A. G. A review on current status of antiviral siRNA. Reviews in Medical Virology 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Firdous, S. M.; Nath, A. siRNA could be a potential therapy for COVID-19. EXCLI journal 2020, 19, 528. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, M. D. S.; Adan, A. Computational analysis of microRNA-mediated interactions in SARS-CoV-2 infection. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chu, H.; Wen, L.; Shuai, H.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yuan, S.; Yin, F. Competing endogenous RNA network profiling reveals novel host dependency factors required for MERS-CoV propagation. Emerging microbes & infections 2020, 9, 733–746. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Sharma, A. R.; Patra, P.; Ghosh, P.; Sharma, G.; Patra, B. C.; Lee, S. S.; Chakraborty, C. Development of epitope-based peptide vaccine against novel coronavirus 2019 (SARS-COV-2): Immunoinformatics approach. Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Kream, R. M.; Stefano, G. B. An evidence based perspective on mRNA-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research 2020, 26, e924700–924701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-y.; Kong, W.-p.; Huang, Y.; Roberts, A.; Murphy, B. R.; Subbarao, K.; Nabel, G. J. A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice. Nature 2004, 428, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, M. S. A.; Rahman, M. M.; Morshed, M. N.; Rahman, D.; Anwar, S.; Hosen, M. J. Genetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 isolates collected from Bangladesh: Insights into the origin, mutational spectrum and possible pathomechanism. Comput Biol Chem 2021, 90, 107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y. J.; Wei, C. L.; Ee, A. L.; Vega, V. B.; Thoreau, H.; Su, S. T.; Chia, J. M.; Ng, P.; Chiu, K. P.; Lim, L.; et al. Comparative full-length genome sequence analysis of 14 SARS coronavirus isolates and common mutations associated with putative origins of infection. Lancet 2003, 361, 1779–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, H.; Wang, X.; Yuan, X.; Xiao, G.; Wang, C.; Deng, T.; Yuan, Q.; Xiao, X. The epidemiology and clinical information about COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2020, 39, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Mannan, R.; Islam, S.; Banu, L. A.; Jamee, A. R.; Hassan, Z.; Elias, S. M.; Das, S. K.; Azad Khan, A. K. Unveiling the occurrence of COVID-19 in a diverse Bangladeshi population during the pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12, Original. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Marinkovic, A.; Patidar, R.; Younis, K.; Desai, P.; Hosein, Z.; Padda, I.; Mangat, J.; Altaf, M. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med 2020, 2, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, S.; Potdar, V.; Jadhav, S.; Yadav, P.; Gupta, N.; Das, M.; Rakshit, P.; Singh, S.; Abraham, P.; Panda, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutations, L452R, T478K, E484Q and P681R, in the Second Wave of COVID-19 in Maharashtra, India. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Kamil, J.; Lee, B.; Moore, P.; Schulz, T. F.; Muik, A.; Sahin, U.; Türeci, Ö.; Pather, S. The Impact of Evolving SARS-CoV-2 Mutations and Variants on COVID-19 Vaccines. mBio 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manouana, G. P.; Nzamba Maloum, M.; Bikangui, R.; Oye Bingono, S. O.; Ondo Nguema, G.; Honkpehedji, J. Y.; Rossatanga, E. G.; Zoa-Assoumou, S.; Pallerla, S. R.; Rachakonda, S.; et al. Emergence of B.1.1.318 SARS-CoV-2 viral lineage and high incidence of alpha B.1.1.7 variant of concern in the Republic of Gabon. Int J Infect Dis 2022, 114, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegally, H.; Ramuth, M.; Amoako, D.; Scheepers, C.; Wilkinson, E.; Giovanetti, M.; Lessells, R.; Giandhari, J.; Ismail, A.; Martin, D.; et al. A Novel and Expanding SARS-CoV-2 Variant, B.1.1.318, dominates infections in Mauritius; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Olawoye, I. B.; Oluniyi, P. E.; Oguzie, J. U.; Uwanibe, J. N.; Kayode, T. A.; Olumade, T. J.; Ajogbasile, F. V.; Parker, E.; Eromon, P. E.; Abechi, P.; et al. Emergence and spread of two SARS-CoV-2 variants of interest in Nigeria. Nature Communications 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercatelli, D.; Giorgi, F. M. Geographic and genomic distribution of SARS-CoV-2 mutations. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T.; Platt, D.; Parida, L. Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2020, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laamarti, M.; Alouane, T.; Kartti, S.; Chemao-Elfihri, M.; Hakmi, M.; Essabbar, A.; Laamarti, M.; Hlali, H.; Bendani, H.; Boumajdi, N. Large scale genomic analysis of 3067 SARS-CoV-2 genomes reveals a clonal geo-distribution and a rich genetic variations of hotspots mutations. PloS one 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, T. SARS-CoV-2 viral spike G614 mutation exhibits higher case fatality rate. Int J Clin Pract 2020, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C. Genotyping coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: methods and implications. Genomics 2020, 112, 3588–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, H.; Yin, B.; Yang, X.; Jiang, W. The divergence between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 might be overestimated due to the extensive RNA modification. Future Virology 2020, 15, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T. S.; Liu, D. X. Post-translational modifications of coronavirus proteins: roles and function. Future Virol 2018, 13, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Bernal, J.; Andrews, N.; Gower, C.; Gallagher, E.; Simmons, R.; Thelwall, S.; Stowe, J.; Tessier, E.; Groves, N.; Dabrera, G. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B. 1.617. 2 (Delta) variant. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARS-CoV-2, B. 1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant—United States, December 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1731–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, O. P.; Dhawan, M. Omicron variant (B. 1.1. 529) of SARS-CoV-2: threat assessment and plan of action. International Journal of Surgery 2022, 97, 106187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abulsoud, A. I.; El-Husseiny, H. M.; El-Husseiny, A. A.; El-Mahdy, H. A.; Ismail, A.; Elkhawaga, S. Y.; Khidr, E. G.; Fathi, D.; Mady, E. A.; Najda, A.; et al. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2: Insights on structure, variants, vaccines, and biomedical interventions. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 157, 113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Socio-demography and Comorbidity | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 12 | 48 |

| Female | 13 | 52 |

| Family history of COVID-19 Infection | 4 | 16 |

| Maintained quarantine period | 12 | 48 |

| Hypertension | 3 | 12 |

| Hypertension with asthma | 1 | 4 |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | 0 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 0 | 0 |

| Re-infected with SARS-CoV-2 | 3 | 12 |

| Vaccinated | 15 | 60 |

| Long duration of COVID-19 positive | 1 | 4 |

| History of long-distance traveling | 0 | 0 |

| Variant | Clade | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | 21A | 20 | 80 |

| 21J | 2 | 8 | |

| Omicron | 20A | 1 | 4 |

| 21K | 1 | 4 | |

| Mauritius | 20B | 1 | 4 |

| Variant | Lineage | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | B.1.617.2 | 7 | 28 |

| AY.4 | 6 | 24 | |

| AY.131 | 2 | 8 | |

| AY.26 | 2 | 8 | |

| AY.29 | 1 | 4 | |

| AY.30 | 1 | 4 | |

| AY.39 | 1 | 4 | |

| AY.122 | 1 | 4 | |

| AY.122.1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Omicron | BA.1 | 2 | 8 |

| Mauritius | B.1.1.318 | 1 | 4 |

| Mutation | Variant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omicron | Delta | Mauritius | |||

| Maximum | Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | ||

| Substitution | 53 | 41 | 45 | 14 | 36 |

| Deletion sites with gap in bp | 6 (45) | 6 (39) | 4 (18) | 3(13) | 5 (35) |

| Insertion sites with length in bp | 1 (9) | 0 | - | - | 1 (3) |

| Genomic region | Substitution | Number of Mutation | Genomic region | Substitution | Number of Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1a | C3037T | 25 | S | C23604G | 22 |

| C10029T | 16 | C21618G | 20 | ||

| G4181T | 15 | G24410A | 17 | ||

| C6402T | 15 | C22995A | 16 | ||

| C8986T | 15 | T22917G | 14 | ||

| G9053T | 15 | C21846T | 9 | ||

| A11201G | 14 | G21987A | 5 | ||

| A11332G | 14 | G22899T | 5 | ||

| C7124T | 10 | A23064C | 4 | ||

| C9891T | 7 | ORF3a | C25469T | 22 | |

| C5184T | 6 | G26104T | 4 | ||

| T12946C | 6 | M | T26767C | 23 | |

| C1191T | 5 | ORF7a | C27752T | 14 | |

| C1267T | 5 | T27638C | 13 | ||

| T11418C | 5 | ORF7b | C27874T | 15 | |

| G1048T | 4 | ORF8 | C28054G | 5 | |

| A2560G | 4 | N | A28461G | 21 | |

| G11083T | 4 | G28881T | 19 | ||

| ORF1b | C14408T | 25 | G29402T | 15 | |

| G15451A | 22 | G28916T | 14 | ||

| C16466T | 19 | T29014C | 4 | ||

| C19220T | 15 | 5′ Leader Sequence | C241T | 16 | |

| C14407T | 5 | G210T | 14 | ||

| G19999T | 5 | near 3′ end | G29742T | 14 | |

| S | A23403G | 25 | G29688T | 5 |

| Nucleotide base change | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| C>T | 344 | 38.48 |

| G>T | 163 | 18.23 |

| A>G | 103 | 11.52 |

| G>A | 77 | 8.61 |

| T>C | 75 | 8.39 |

| C>G | 48 | 5.37 |

| C>A | 33 | 3.69 |

| T>G | 22 | 2.46 |

| A>C | 10 | 1.12 |

| A>T | 7 | 0.78 |

| G>C | 6 | 0.67 |

| T>A | 6 | 0.67 |

| Mutation | Base Change | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition | Purine>Purine/ Pyrimidine>Pyrimidine |

599 | 67 |

| Transversion | Purine>Pyrimidine/ Pyrimidine>Purine |

295 | 33 |

| Deletion (bp) of variant (gene) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | Omicron | Mauritius | ||

| 21A | 21J | 20A | 21K | 20B |

| 22029-22035 (S) | 21992-21994 (S) | 6513-6516 (ORF1a) | 6513-6515 (ORF1a) | 11288-11297 (ORF1a) |

| 28248-28254 (ORF8) | 22029-22034 (S) | 11287-11296 (ORF1a) | 11285-11293 (ORF1a) | 21994-21997(S) |

| 28274 (N) | 28248-28253 (ORF8) |

21766-21772 (S) |

21765-21770 (S) | 27887-27902 (ORF7b, ORF8) |

| 29750-29752 (Non-coding) | 28271 (Non-coding) |

21987-21996 (S) | 21987-21995 (S) | 28254 (ORF8) |

| 22194-22197 (S) |

22194-22196 (S) | 28896-28899 (N) | ||

| 28363-28372 (N) | 28362-28370 (N) | |||

| Variant (Clade) |

Insertion position with inserted sequence | Length (bp) | Mapped gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omicron (21K) |

22204:GAGCCAGAA | 9 | S |

| Omicron (20A) |

22206:GCCAGAAGA | 9 | S |

| Mauritius (20B) |

28250:CTG | 3 | ORF8 |

| Genomic region | Amino Acid Substitutions | Number of Mutations | Genomic region | Amino Acid Substitutions | Number of Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1a | T3255I | 16 | S | D950N | 17 |

| A1306S | 15 | T478K | 16 | ||

| P2046L | 15 | L452R | 14 | ||

| V2930L | 15 | T95I | 9 | ||

| T3646A | 14 | G142D | 6 | ||

| P2287S | 10 | G446V | 5 | ||

| A3209V | 7 | N501T | 4 | ||

| P1640L | 5 | H655Y | 3 | ||

| P309L | 5 | P681H | 3 | ||

| V3718A | 5 | ORF3a | S26L | 22 | |

| K261N | 4 | D238Y | 4 | ||

| L3606F | 4 | M | I82T | 24 | |

| H2092Y | 3 | ORF7a | T120I | 14 | |

| ORF1b | G662S | 22 | V82A | 13 | |

| P314L | 20 | L116F | 3 | ||

| P1000L | 19 | ORF7b | T40I | 15 | |

| A1918V | 15 | ORF8 | S54* | 5 | |

| P314F | 5 | ORF9b | T60A | 21 | |

| V2178F | 5 | N | M1X | 20 | |

| S | D614G | 25 | D63G | 19 | |

| P681R | 22 | R203M | 19 | ||

| E156G | 20 | D377Y | 15 | ||

| T19R | 20 | G215C | 14 |

| Gene | Deletion Mutations |

Number of Mutations |

|---|---|---|

| ORF1a | S3675- | 3 |

| G3676- | 3 | |

| F3677- | 2 | |

| L2084- | 1 | |

| S2083- | 1 | |

| L3674- | 1 | |

| S | F157- | 22 |

| R158- | 20 | |

| E156- | 2 | |

| H69- | 2 | |

| V70- | 2 | |

| V143- | 2 | |

| Y144- | 4 | |

| Y145- | 1 | |

| L212- | 1 | |

| G142- | 1 | |

| N211- | 1 | |

| ORF8 | D119- | 22 |

| F120- | 22 | |

| M1- | 1 | |

| K2- | 1 | |

| ORF9b | N28- | 2 |

| A29- | 2 | |

| V30- | 1 | |

| E27- | 1 | |

| N | E31- | 2 |

| R32- | 2 | |

| S33- | 2 | |

| R209- | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).