Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods and Material

Ethical Clearance

Study Population and Specimen Collection

Viral Load Determination and cDNA Synthesis

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Assembly

Variant Analysis

Phylogenetic Analysis

Statistical Analysis and Visualization

Results

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Assembly and Sequencing Metrics of SARS-CoV-2 Raw Read Sequences

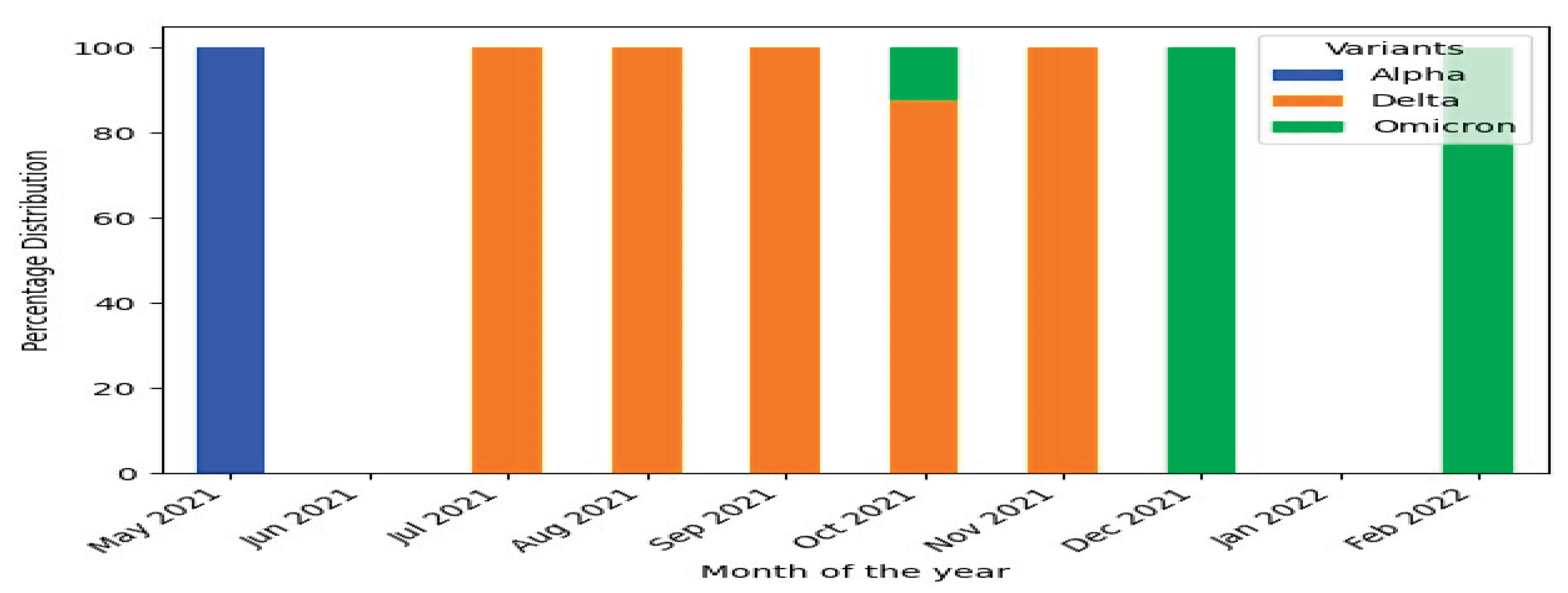

SARS-CoV-2 Genetic Diversity over the Study Period

| WHO Variant N (%) | Pangolin Lineage N (%) | Next strain Clade N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | 2 (7.7) | B.1.1.7 | 2 (7.7) | 20I | 2 (7.7) |

| Delta | 21 (80.8) | AY.120 | 12 (46.2) | 21J | 21 (80.8) |

| B.1.617.2 | 7 (26.9) | ||||

| AY.32 | 2 (7.7) | ||||

| Omicron | 3 (11.5) | BA.1.1 | 1 (3.8) | 21K | 3 (11.5) |

| BA.1.17 | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| BA.1 | 1 (3.8) | ||||

Patterns of SARS-CoV-2 Genetic Variation During the Study

Nucleotide and Amino Acid Mutation Analysis in SARS-CoV-2 Genes

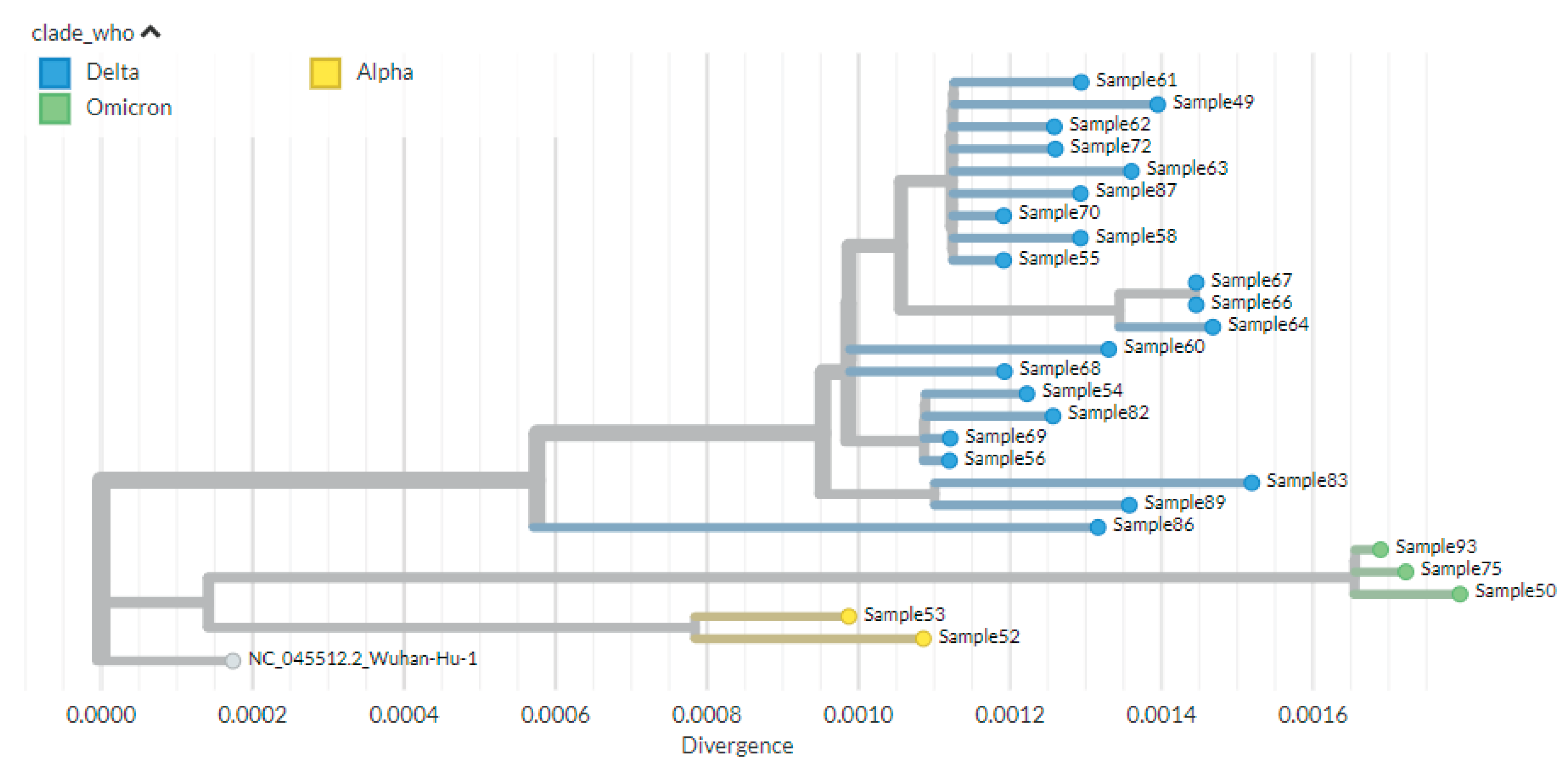

Phylogenetic Analysis

Discussion

Limitations of the Study

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

Author Disclaimer

References

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants, https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants, 2021.

- Domingo E, García-Crespo C, Lobo-Vega R, Perales C. Mutation rates, mutation frequencies, and proofreading-repair activities in rna virus genetics. Vol. 13, Viruses. MDPI; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wu A, Peng Y, Huang B, Ding X, Wang X, Niu P, et al. Genome Composition and Divergence of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Originating in China. Vol. 27, Cell Host and Microbe. Cell Press; 2020. p. 325–8. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html. 2021;

- GISAID) GI o. SAID. Tracking of Variants, https://www.gisaid.org/hcov19-284 variants (2021). 2021;

- CDC. Delta variant: what we know about the science. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2021. 2021.

- Tao K, Tzou PL, Nouhin J, Gupta RK, de Oliveira T, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Vol. 22, Nature Reviews Genetics. Nature Research; 2021. p. 757–73. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Guidance on tools for detection and surveillance of SARS CoV-2 Variants Interim Guidance, Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Version 1.0. 2021.

- Eur Centre Dis Prev Control. Ba A, Changed VO, Added VO, Ba A, Replaced O. Changes to list of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, variants of interest, and variants under monitoring. 2022.

- World Health Organization. *Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants*. 2023.

- Bhattacharya M, Chatterjee S, Sharma AR, Lee SS, Chakraborty C. Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2: current understanding of infection, transmission, immune escape, and mutational landscape. Vol. 68, Folia Microbiologica. Springer Science and Business Media B.V.; 2023. p. 17–28. [CrossRef]

- Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, Staropoli I, Guivel-Benhassine F, Rajah MM, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021 Aug 12;596(7871):276–80. [CrossRef]

- McBroome J, Thornlow B, Hinrichs AS, Kramer A, De Maio N, Goldman N, et al. A Daily-Updated Database and Tools for Comprehensive SARSCoV-2 Mutation-Annotated Trees. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(12):5819–24. [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases Concern https://nccid.ca/covid-19-variants. Updates on COVID-19 Variants of. 2021.

- Mlcochova P, Kemp SA, Dhar MS, Papa G, Meng B, Ferreira IATM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 Delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature. 2021 Nov 4;599(7883):114–9. [CrossRef]

- Harvey WT, Carabelli AM, Jackson B, Gupta RK, Thomson EC, Harrison EM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Vol. 19, Nature Reviews Microbiology. Nature Research; 2021. p. 409–24. [CrossRef]

- Aga AM, Mulugeta D, Gebreegziabxier A, Zeleke GT, Girmay AM, Tura GB, et al. Genome diversity of SARS-CoV-2 lineages associated with vaccination breakthrough infections in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2025 Dec 1;25(1). [CrossRef]

- Hailu Alemayehu D, Adnew B, Alemu F, Abeje Tefera D, Seyoum T, Tesfaye Beyene G, et al. Whole-Genome Sequences of SARS-CoV-2 Isolates from Ethiopian Patients GENOME SEQUENCES. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chekol MT, Sugerman D, Tayachew A, Mekuria Z, Tesfaye N, Alemu A, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 virus among patients with acute febrile illness in selected sites of Ethiopia 2021–2022. Front Public Health. 2025;13.

- Kia P, Katagirya E, Kakembo FE, Adera DA, Nsubuga ML, Yiga F, et al. Genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2 from Uganda using MinION nanopore sequencing. Sci Rep. 2023 Dec 1;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Chan WS, Lam YM, Law JHY, Chan TL, Ma ESK, Tang BSF. Geographical prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, August 2020 to July 2021. Sci Rep. 2022 Dec 1;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Nicot F, Trémeaux P, Latour J, Jeanne N, Ranger N, Raymond S, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: Comparison of target capture and amplicon single molecule real-time sequencing protocols. J Med Virol. 2023 Jan 1;95(1).

- Cohen C, Kleynhans J, von Gottberg A, McMorrow ML, Wolter N, Bhiman JN, et al. Characteristics of infections with ancestral, Beta and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2 in the PHIRST-C community cohort study, South Africa, 2020-2021. BMC Infect Dis. 2024 Dec 1;24(1). [CrossRef]

- Tegally H, San JE, Cotten M, Moir M, Tegomoh B, Mboowa G, et al. The evolving SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Africa: Insights from rapidly expanding genomic surveillance. Science (1979). 2022 Oct 7;378(6615). [CrossRef]

- CDC. Science brief: COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2021. 2021.

- Smallman-Raynor MR, Cliff AD, Robson SC, Connor TR, Loman NJ, Golubchik T, et al. Spatial growth rate of emerging SARS-CoV-2 lineages in England, September 2020-December 2021. Epidemiol Infect. 2022 Jul 20;150.

- Gangavarapu K, Latif AA, Mullen JL, Alkuzweny M, Hufbauer E, Tsueng G, et al. Outbreak.info genomic reports: scalable and dynamic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants and mutations. Nat Methods. 2023 Apr 1;20(4):512–22. [CrossRef]

- Taboada B, Zárate S, García-López R, Muñoz-Medina JE, Sanchez-Flores A, Herrera-Estrella A, et al. Dominance of Three Sublineages of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant in Mexico. Viruses. 2022 Jun 1;14(6). [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe D, Jayathilaka D, Jeewandara C, Gunasinghe D, Ariyaratne D, Jayadas TTP, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of AY.28 and AY.104 Delta Sub-lineages in Sri Lanka. Front Public Health. 2022 Jun 21;10. [CrossRef]

- Tulimilli SR V., Dallavalasa S, Basavaraju CG, Kumar Rao V, Chikkahonnaiah P, Madhunapantula SR V., et al. Variants of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Vaccine Effectiveness. Vol. 10, Vaccines. MDPI; 2022.

- Alhamlan FS, Al-Qahtani AA. SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Genetic Insights, Epidemiological Tracking, and Implications for Vaccine Strategies. Vol. 26, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhan Y, Yin H, Yin JY. B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant of SARS-CoV-2: Features, transmission and potential strategies. Vol. 18, International Journal of Biological Sciences. Ivyspring International Publisher; 2022. p. 1844–51. [CrossRef]

- Shayan S, Jamaran S, Askandar RH, Rahimi A, Elahi A, Farshadfar C, et al. The SARS-Cov-2 Proliferation Blocked by a Novel and Potent Main Protease Inhibitor via Computer-aided Drug Design. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2021 Jun 1;20(3):399–418. [CrossRef]

- Hoteit R, Yassine HM. Biological Properties of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Epidemiological Impact and Clinical Consequences. Vol. 10, Vaccines. MDPI; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Carabelli AM, Peacock TP, Thorne LG, Harvey WT, Hughes J, de Silva TI, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Vol. 21, Nature Reviews Microbiology. Nature Research; 2023. p. 162–77. [CrossRef]

- Katowa B, Kalonda A, Mubemba B, Matoba J, Shempela DM, Sikalima J, et al. Genomic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in the Southern Province of Zambia: Detection and Characterization of Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron Variants of Concern. Viruses. 2022 Sep 1;14(9). [CrossRef]

- G/meskel W, Desta K, Diriba R, Belachew M, Evans M, Cantarelli V, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant typing using real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction–based assays in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. IJID Regions. 2024 Jun 1;11. [CrossRef]

- Sow MS, Togo J, Simons LM, Diallo ST, Magassouba ML, Keita MB, et al. Genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2 in Guinea, West Africa. PLoS One. 2024 Mar 1;19(3 March). [CrossRef]

- Shaibu JO, Onwuamah CK, James AB, Okwuraiwe AP, Amoo OS, Salu OB, et al. Full-length genomic sanger sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2021 Jan 1;16(1 January). [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Chen D, Zhu C, Zhao Z, Gao S, Gou J, et al. Genetic Surveillance of Five SARS-CoV-2 Clinical Samples in Henan Province Using Nanopore Sequencing. Front Immunol. 2022 Apr 4;13. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=48) | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 22 | 46% |

| Male | 26 | 54% | |

| Age | 15-24 Years old | 3 | 6% |

| 25-44 Years old | 22 | 46% | |

| 45-64 years old | 8 | 17% | |

| 65+ | 15 | 31% | |

| Symptoms | Fever | 48 | 100% |

| Cough | 40 | 83% | |

| Sore Throat | 31 | 65% | |

| Difficulty of breathing | 27 | 56% | |

| Headache | 34 | 71% | |

| Muscle ache | 30 | 63% | |

| Arthralgia | 16 | 33% | |

| Admission Status | Inpatient | 43 | 90% |

| Outpatient | 5 | 10% | |

| Barcode | # Reads | Depth of Coverage | Nucleotide Identity (%) | Amino Acid Identity (%) | Genome Coverage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 | 27604 | 485 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 50 | 27620 | 502 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 96.0 |

| 52 | 55585 | 1014 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.4 |

| 53 | 15574 | 279 | 99.9 | 99.8 | 99.4 |

| 54 | 28642 | 486 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 55 | 42675 | 769 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 56 | 51054 | 915 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 58 | 27377 | 485 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 60 | 51101 | 931 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 97.7 |

| 61 | 43354 | 771 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 62 | 27608 | 495 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 63 | 55379 | 979 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 64 | 53559 | 959 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 66 | 26429 | 466 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.2 |

| 67 | 53016 | 937 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 68 | 37235 | 666 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 98.2 |

| 69 | 26743 | 467 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 97.5 |

| 70 | 33827 | 595 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 72 | 35043 | 610 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.2 |

| 75 | 37569 | 646 | 99.8 | 99.6 | 99.4 |

| 82 | 46077 | 841 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 83 | 17440 | 293 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 95.7 |

| 86 | 23716 | 430 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 87 | 37558 | 662 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 89 | 21772 | 360 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| 93 | 54886 | 949 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| Variant (Sub-lineage) | Protein | High-Frequency Substitutions (>75%) | High-Frequency Deletions (>75%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha (B.1.1.7) | ORF1a | T1001I, A1708D, P2287S | S3675-, G3676-, F3677- |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S | ||

| ORF8 | Q27, R52I, K68, Y73C | ||

| N | D3L, R203K, G204R, S235F | ||

| S | N501Y, D614G, P681H | H69-, V70-, Y144- | |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) | ORF1a | A1306S, P2046L, P2287S, V2930L, T3255I, T3646A | |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S, P1000L, A1918V | ||

| ORF3a | S26L | ||

| ORF7a | V82A, T120I | ||

| ORF7b | T40I | ||

| ORF9b | T60A | ||

| M | I82T | ||

| N | D63G, R203M, G215C, D377Y | ||

| S | T19R, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| Delta (AY.32) | ORF1a | A1306S, P2046L, P2287S, V2930L, T3255I, T3646A | |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S, P1000L, A1918V, T2376I, R2613C | ||

| ORF3a | S26L | ||

| ORF7a | V82A, T120I | ||

| ORF7b | T40I | ||

| ORF9b | T60A | ||

| M | I82T | ||

| N | D63G, R203M, G215C, D377Y | ||

| S | T19R, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| Delta (AY.120) | ORF1a | V28I, A1306S, P2046L, S2048F, P2287S, V2930L, T3255I, T3646A | |

| ORF1b | P314L, G662S, P1000L, A1918V, A2306T | ||

| ORF3a | S26L | ||

| ORF7a | V82A, T120I | ||

| ORF7b | T40I | ||

| ORF9b | T60A | ||

| M | I82T | ||

| N | D63G, R203M, G215C, D377Y | ||

| S | T19R, T95I, G142D, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N | E156-, F157- | |

| Omicron (BA.1; BA.1.1, BA.1.17) | ORF1a | K856R, A2710T, T3255I, P3395H, I3758V | L3674-, S3675-, G3676- |

| ORF1b | P314L, I1566V | ||

| ORF9b | P10S | E27-, N28-, A29- | |

| M | D3G, Q19E, A63T | ||

| N | P13L, R203K, G204R | E31-, R32-, S33- | |

| S | A67V, T95I, G142D, Y145D, L212I, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, L981F | H69-, V70-, G142-, V143-, Y144-, N211- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).