1. Introduction

Crystallization in polymers is fundamentally more complex than in small molecules due to chain connectivity and topological constraints, which necessitate both conformational and spatial ordering. Upon cooling, polymers transition from coiled to semicrystalline states, yet a persistent amorphous phase often remains [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This transformation is driven by weak van der Waals interactions, whereas excluded volume effects hinder the entropic collapse into crystalline configurations [

6]. Classical models such as Lauritzen-Hoffman (LH) [

7] and Sadler-Gilmer (SD) [

8] have described lamellar growth, but several aspects remain unresolved: the role of local structure in the melt prior to nucleation, the dynamic reentry of chains into crystalline regions, and how heterogeneous liquid environments influence growth pathways [

9,

10,

11].

Molecular simulations have helped clarify non-equilibrium crystallization mechanisms in short [

12,

13,

14] and entangled chains [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], often using local order parameters. These descriptors are designed to extract physically meaningful structure from disordered polymer configurations using rotation- and translation-invariant representations [

21,

22]. Angle-based alignment metrics, commonly applied to quantify segmental order, classify crystalline domains by comparing the principal axes of adjacent segments [

12,

14,

23,

24,

25]. However, angle-based metrics lack universal thresholds and are undefined at chain ends, and spatial averaging, though useful for noise reduction, often obscures interfacial and precursor structures critical to nucleation and growth.

A range of translational and orientational order parameters (OPs) have been developed for identifying structural motifs in small-molecule systems, including Common Neighbor Analysis (CNA) [

26], Bond Angle Analysis (BAA) [

27], the Centrosymmetry Parameter (CNP) [

28], Voronoi tessellation [

29,

30], and Steinhardt’s Bond-Orientational Order (BOO) parameters [

31]. Although many of these descriptors were originally designed to detect crystalline phases such as fcc, bcc, and icosahedral structures in atomic systems [

21], select methods, particularly Voronoi and BOO, have shown promise for application to polymeric systems. Recently, we systematically assessed these OPs in the context of polymer crystallization. Voronoi analysis adapts well to local density variations, but lacks information on orientational symmetry. In contrast, BOO parameters capture rotationally invariant local motifs using spherical harmonics [

32] and have been used to study crystallization, glass transitions, and interface behavior in soft matter systems [

33,

34,

35,

36]. However, conventional BOO calculations are highly sensitive to how neighbors are defined, by distance, number, or topology, and can fail to resolve subtle structural distinctions, such as variations in Wyckoff positions [

37]. Methods such as solid angle nearest neighbors (SANN) [

38] and polyhedral template matching (PTM) [

39] have addressed some of these limitations in small-molecule systems, but their effectiveness in polymers remains limited. In particular, the search for unique order parameters to identify and classify potentially short-lived precursor states has not yet been successful.

Spectrum-based descriptors, such as Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) [

40], Behler– Parrinello symmetry functions, and bispectrum coefficients, have extended the capabilities of traditional order parameters by mapping local environments into high-dimensional feature spaces. Unlike conventional BOO parameters, which summarize local symmetry using spherical harmonics, these descriptors retain richer structural information and enable advanced machine learning workflows [

41,

42,

43]. To the best of our knowledge, this study presents the first systematic application and evaluation of SOAP descriptors in polymer crystallization, as their ability to capture chain connectivity, local packing anisotropy, and precursor states has not been previously explored.

Machine learning techniques have been increasingly used to extract structure-property relationships from high-dimensional data in a wide range of materials applications [

22,

44,

45,

46,

47]. The Spectrum-based descriptors have been widely used in atomic systems to investigate crystallization, phase behavior, and self-assembly through unsupervised learning and clustering techniques, often combined with dimensionality reduction [

48,

49,

50]. In particular, Spellings and Glotzer [

41] introduced a fingerprint that avoids spherical harmonic averaging, using odd

l values and variable neighborhood sizes to enhance rotational sensitivity. Adorf et al. [

42] further integrated bispectrum features with BOO, bond angle, and distance metrics for manifold learning via HDBSCAN and classifier training. More recently, Bhardwaj et al. [

51] applied self-supervised autoencoders to analyze conformational fingerprints constructed from shell-averaged angle-based OPs, enabling the detection of local order in entangled polymer systems.

Parallel to geometric and symmetry-based descriptors, local thermodynamic-like parameters, specifically entropy and enthalpy, have shown strong potential for identifying phase transitions at the particle level. Building on the early statistical mechanics work by Nettleton and Green [

52], Piaggi et al. [

53,

54] introduced localized entropy and enthalpy measures derived from smoothed radial distribution functions, successfully distinguishing liquid and crystalline regions in atomic systems. Unlike ensemble-averaged thermodynamic quantities, these local estimates capture spatial variations relevant to nucleation. Nafar Sefiddashti et al. [

19,

55] extended this framework to polymer crystallization under elongational flow, demonstrating that configurational entropy could signal the onset of crystallization without requiring system-specific hyperparameters. However, challenges remain in quiescent systems, where radial distribution-based entropy may misclassify folded regions due to their proximity but lack of geometric symmetry. Although folds often appear entropically ordered, they lack orientational coherence and scalar entropy values cannot fully resolve this distinction.

Recognizing these limitations, in our previous study [

56], we developed a machine learning framework that quantitatively assessed a broad set of geometric, entropic, and symmetry-based order parameters in polymer crystallization. Our results showed that scalar entropy outperformed other descriptors in the detection of early nucleation events, but its effectiveness diminished in the resolution of the surface structure or the distinction between competing internal motifs. To address this, we introduced the crystallinity index (

C-index) [

56] to evaluate the OP sensitivity in the nucleation stages and identified entropy as one of the most informative indicators of the early stages. These insights motivate a new direction: moving beyond scalar thermodynamic variables toward spatially resolved entropy-based features that retain physical interpretation while capturing configurational anisotropy.

To overcome the limitations of scalar entropy and enhance local structural resolution, we introduce a new class of thermodynamic-like descriptors, namely, directional entropy bands. This approach extends the idea of local entropy by partitioning the radial space around each atom into concentric shells, or “bands”, and computing the entropy contributions within each band separately. These directional bands capture anisotropic variations in local configurational order and enable a more detailed distinction between folded segments, crystal surfaces, amorphous regions, and precursor structures. By combining radial decomposition with angular moments and dimensionality reduction, this method produces spatially resolved fingerprints that are both interpretable and physically grounded. Importantly, we demonstrate that simple averages of directional entropy bands, when combined with local enthalpy or spatial orientation metrics, can match or exceed the discriminative power of high-dimensional spectral descriptors like SOAP, particularly in early-stage crystallization.

The data summarize the performance of these descriptors against conventional OPs and spectrum-based ML fingerprints across nucleation regimes; (ii) benchmark the performance of these descriptors against conventional OPs and spectrum-based ML fingerprints across nucleation regimes, (iii) propose a simple yet effective averaging scheme that combines entropy bands with angular information to enhance the identification of anisotropic structures, such as folds and crystal edges, and (iv) provide a machine learning workflow that integrates unsupervised

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section II presents the theoretical foundation and computational methodology, including the calculation of entropy bands, angular expansions, and ML workflows. Section III evaluates the performance of entropy bands through dimensionality reduction, clustering, and classification, comparing them with conventional and spectrum-based OPs. Section IV discusses the implications of directional entropy in identifying precursor structures and interfacial features. Finally, Section V summarizes the key findings and provides directions for future work.

3. Results and Discussion

To assess the effectiveness of structural order parameters in distinguishing amorphous, crystalline, and interfacial phases during polymer crystallization, we analyze both high-dimensional symmetry-based descriptors and physically interpretable thermodynamic metrics. We begin with the Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP), a geometric fingerprint that encodes local environments via rotationally invariant density projections. As a high-dimensional symmetry-aware descriptor, SOAP has demonstrated strong performance in capturing subtle structural motifs in both crystalline and disordered materials [

22,

40,

43]. Given its sensitivity to local geometric arrangements, we hypothesize that SOAP may also capture interfacial complexity in polymers, particularly in regions where traditional order parameters fail to resolve transitional environments. In the following, after discussing the results of the SOAP method, we will evaluate entropy-based descriptors, beginning with scalar entropy bands and then we add the directional variants which integrate the local anisotropy.

Throughout this study, we focus more on four representative simulation time points to be consistent with the literature [

51,

56]: pre-nucleation (

), transitional (

), intermediate growth (

), and steady-state crystallization (

). These time points were defined in our previous work [

56], based on the evolution of system density and cluster size.

3.1. Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) Descriptors

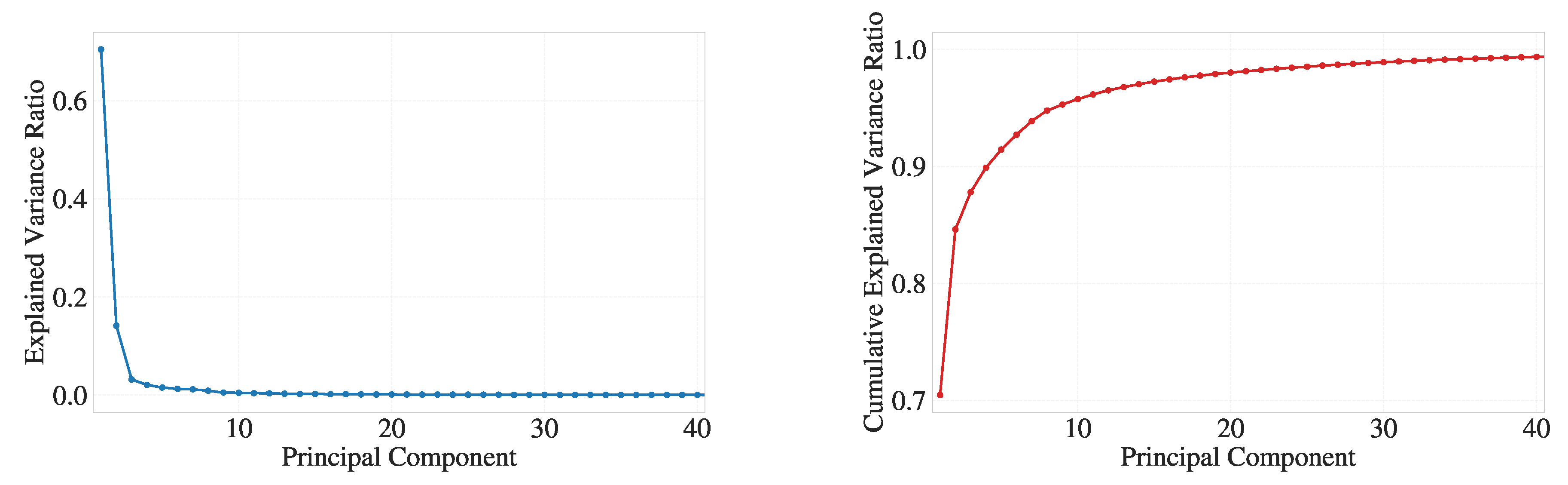

To the best of our knowledge, the use of SOAP in polymeric systems and the findings of the ML analyses to be presented are novel contributions. Therefore, this work is a test application of SOAP descriptors to distinguish structural phases in a polymeric system. In the present case, each SOAP fingerprint vector has 324 components, generated using the parameters , , , and .

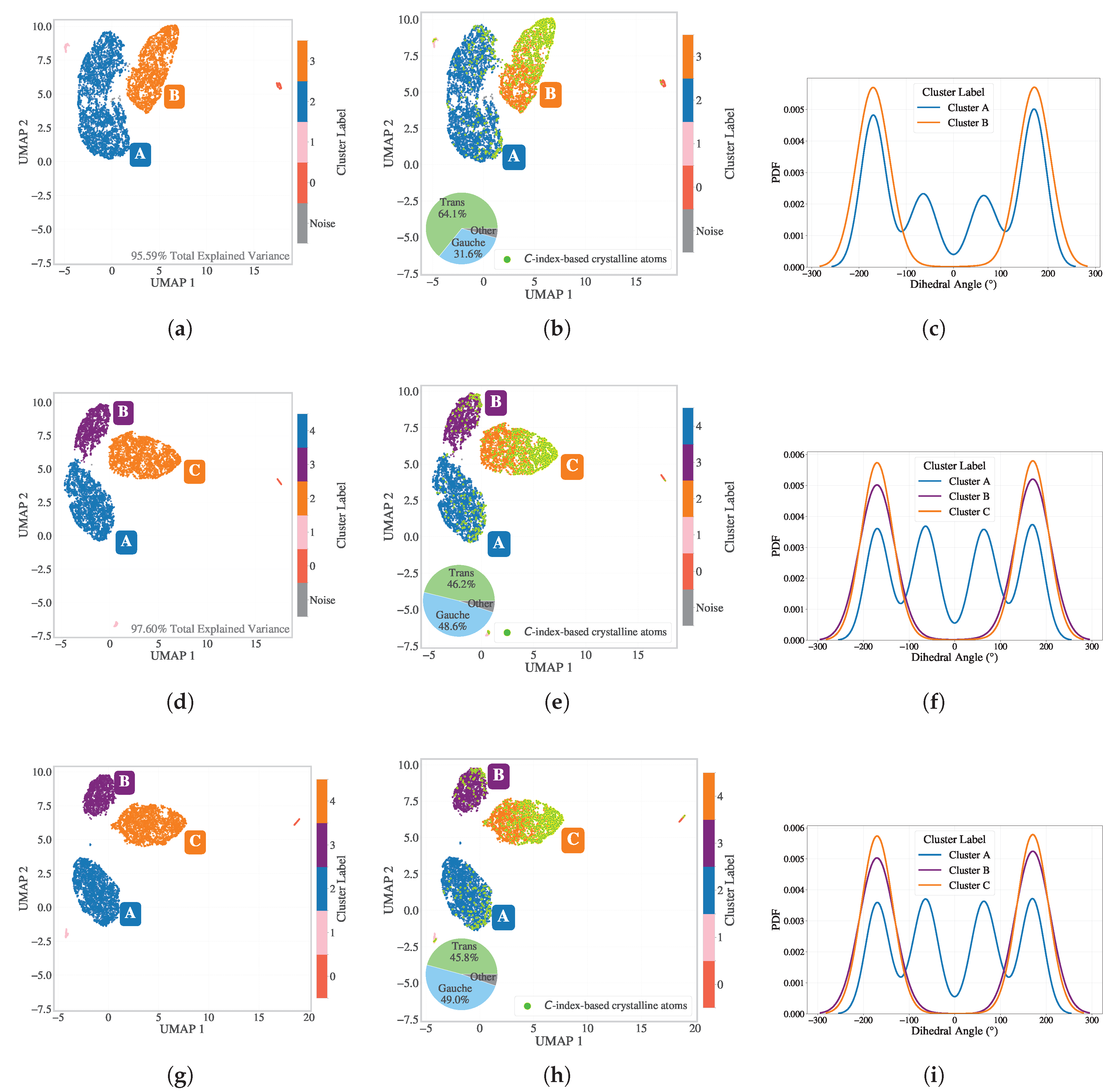

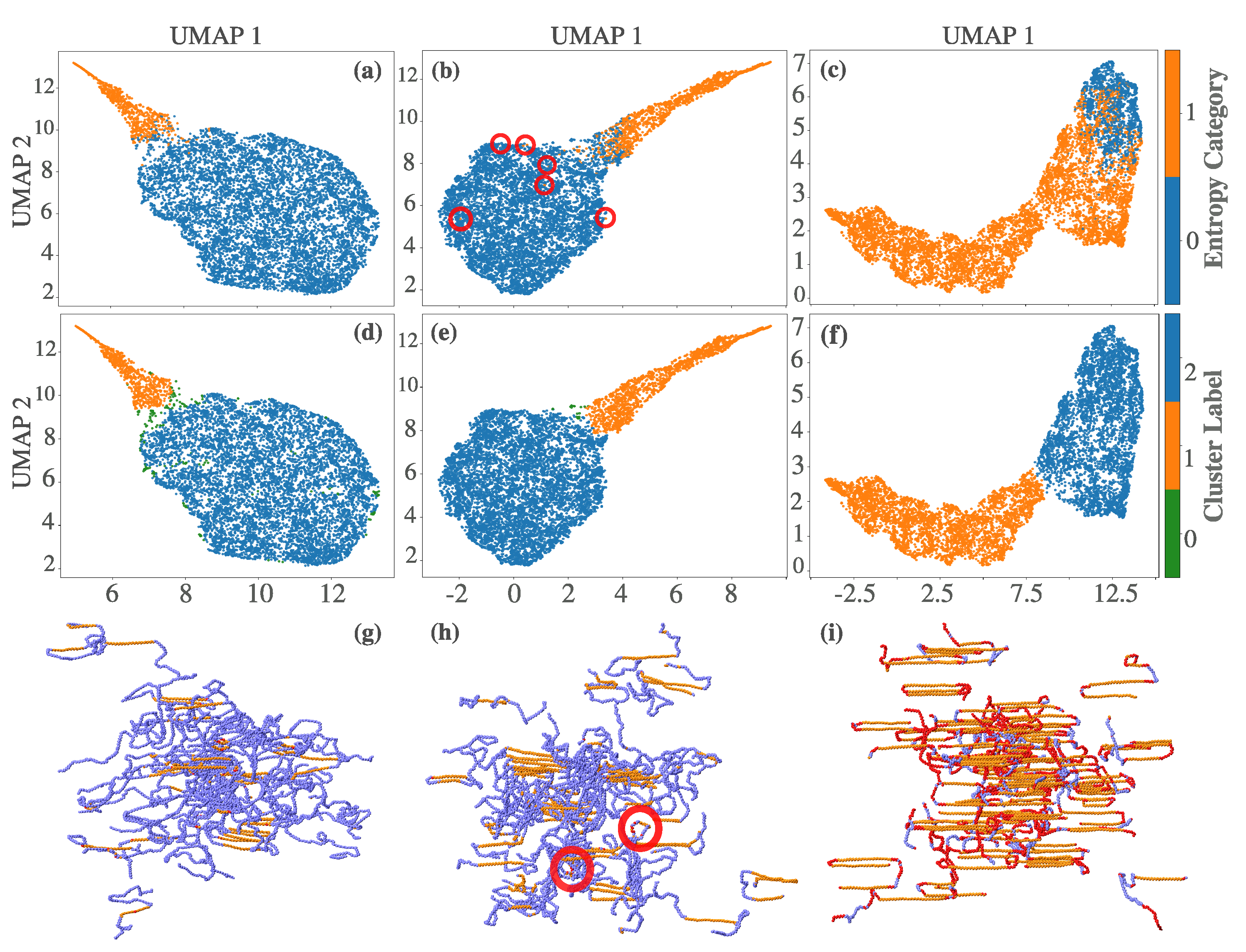

To assess how best to reduce these high-dimensional data, dimensionality reduction was performed at a representative intermediate time step (

). In

Figure 2, three approaches are compared: (a), (b), (c) PCA for 15 components followed by UMAP to 2D, (d), (e), (f) PCA for 25 components followed by UMAP and (g), (h), (i) direct UMAP without PCA. For PCA-based reductions, the total variance retained was 95.59% with 15 components and 97.60% with 25 components (shown in panels (a) and (d), respectively). The retention of the variance for the PCA projections is summarized in Appendix

Figure A2. In panel (a), the 2D embedding after PCA(15)+UMAP is shown. When colored by

values (panel b), two major clusters emerge, albeit with considerable noise within the crystalline cluster that

shows noncrystal particles as well. Interestingly, when plotted by the dihedral backbone conformation (panel c), the entire orange cluster consists of trans conformations, whereas the blue cluster includes both trans and gauche (with approximately 64% trans and 31% gauche).

Panel (d) shows PCA(25)+UMAP, where the embedding reveals three clusters. In panel (e), the classification highlights the crystalline cluster, now more distinct from the rest. The dihedral coloring (f) reveals that both the orange and purple clusters correspond to trans conformations, while the blue cluster retains mixed conformations with around 46% trans and 49% gauche.

Panel (g) presents the direct UMAP result, which shows even greater separation among the clusters. Again, panel (h) highlights the -classified crystalline particles concentrated in the orange cluster. Cluster A includes 46% trans and 49% gauche dihedral configurations. Panel (i) confirms the trans and gauche conformation separation. Given cleaner separation and the potential to retain subtle features, the direct UMAP pipeline was selected for SOAP dimensionality reduction. Since the resulting UMAP embeddings showed well-separated clusters, it was not necessary to perform a detailed hyperparameter benchmark for HDBSCAN in this case.

Pie charts were added next to cluster A in the embeddings to display the proportion of trans versus gauche conformations. And small peripheral clusters across all UMAP embeddings were found to correspond to chain-end particles or those immediately adjacent to them.

All analyses were performed on per-particle SOAP descriptors computed in the quiescent state without alignment or centering, ensuring consistent treatment of local chain geometry across the system. Researchers adopting different SOAP parameterizations that lead to even higher-dimensional feature spaces are advised to repeat this PCA+UMAP comparison. UMAP performance may be degraded in extremely high dimensions [

80], and overaggressive PCA may ignore informative variance.

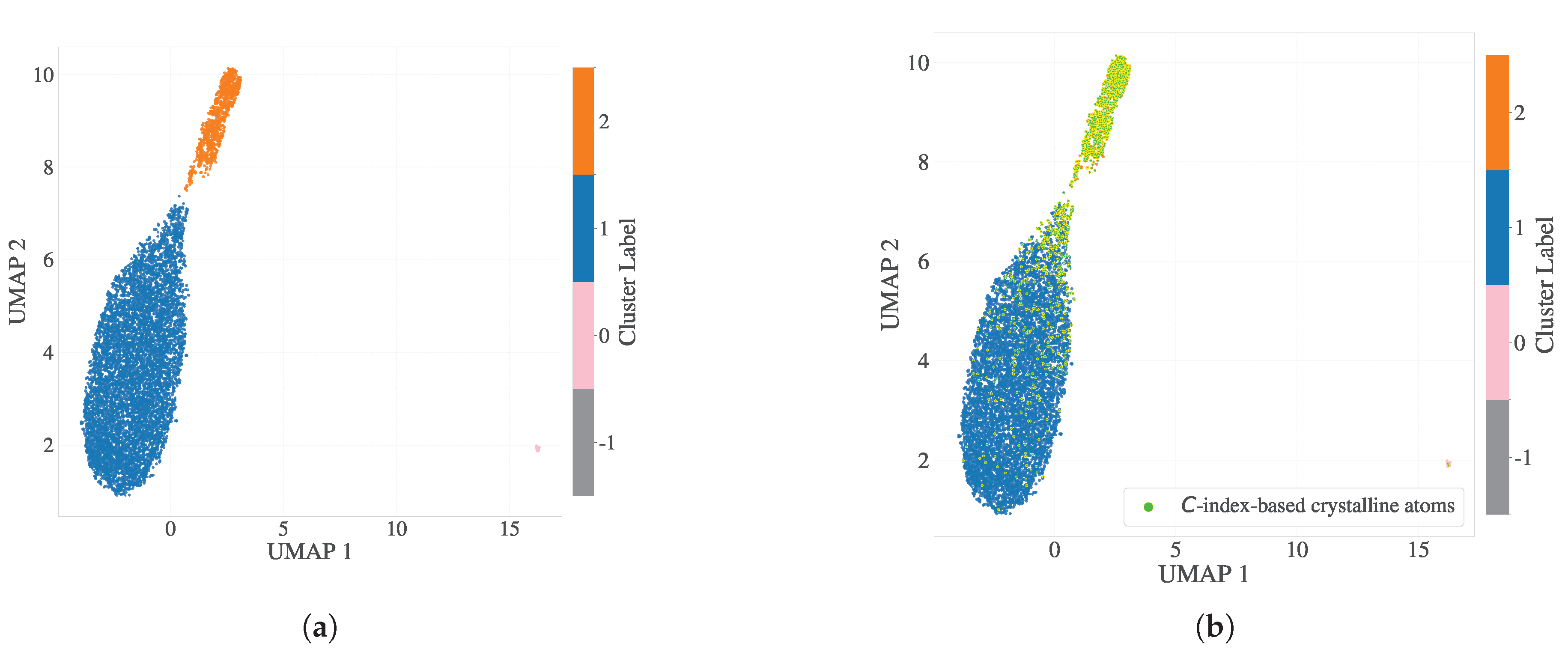

To investigate the temporal stability of SOAP-based classifications, we extended each particle’s descriptor by concatenating SOAP vectors across 20 consecutive time steps centered around

, ranging from

to

. This resulted in high-dimensional fingerprints of size

per particle. Dimensionality reduction was performed using PCA (retaining 25 components) followed by UMAP to embed the data into two dimensions, which was subsequently clustered using HDBSCAN (

Figure 3a). The resulting clusters aligned closely with those classified as crystalline by the scalar parameter

(panel b), although the stacked temporal representation precludes the analysis of instantaneous conformational states such as dihedrals.

A similar strategy was applied in our previous study for bond orientation order (BOO) descriptors using 5, 10 and 20 time-step windows, where longer temporal windows led to progressively improved separability between phases [

56]. This finding echoes the observations by Adorf et al. [

42], who demonstrated that incorporating time into high-dimensional spherical harmonic descriptors significantly improves clustering resolution.

However, despite its benefits, we do not adopt temporally stacked descriptors in the remainder of this study, as the goal here is to study OPs that achieve high performance on the same-time structures so that we can move towards creating better and parsimonious models of high temporal resolution dynamics of structures, e.g. nucleation and surface growth. Simple concatenation of features over time and use of opaque models would not help in this regard.

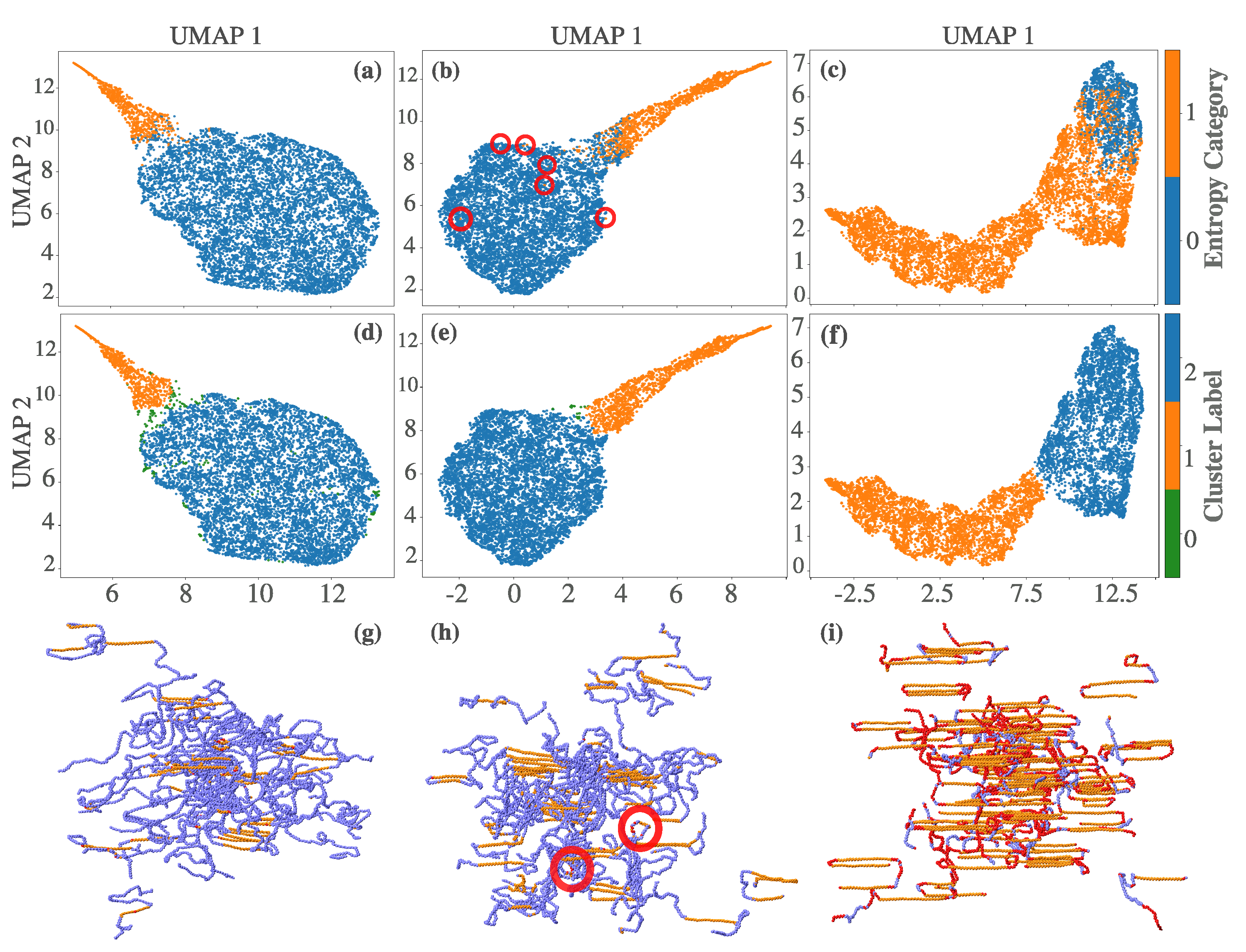

3.2. Directional Entropy Bands: Resolving Local Configurational Order

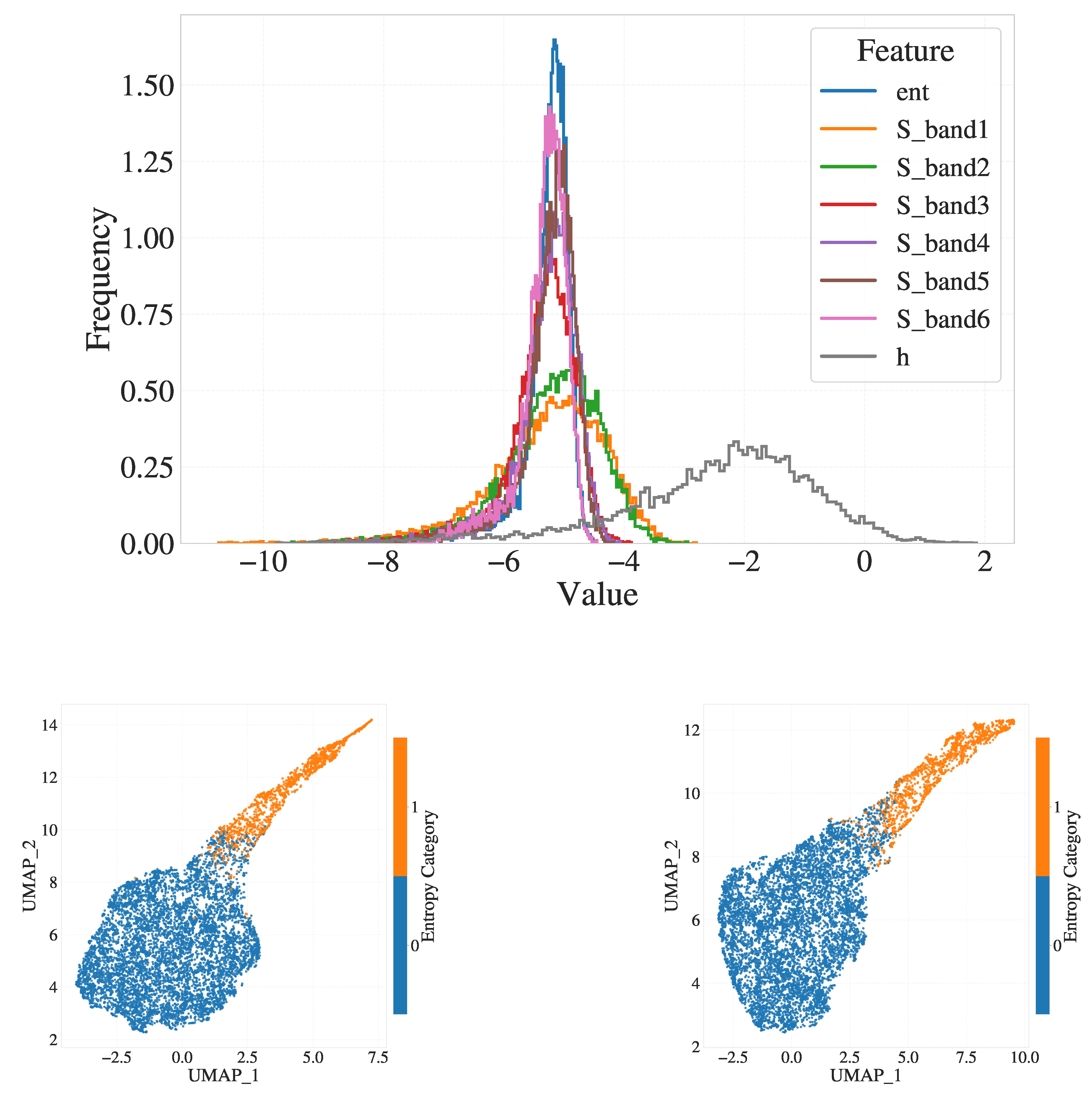

3.2.1. Manifold Learning and Comparison of Band-Averaged and Scalar Entropy

To investigate whether entropy bands provide enhanced structural resolution over scalar entropy, we applied UMAP to the entropy band vectors combined with local enthalpy (see

Appendix A.1 for a comparison of feature scaling methods, including skewness correction of thermodynamic-like parameters prior to dimensionality reduction).

Figure 4 presents the resulting embeddings in three representative crystallization stages: transitional (

), intermediate (

) and steady state (

). Panels (a)–(c) show the UMAP projections colored by the scalar entropy threshold (

). These embeddings highlight the absence of sharp phase separation, especially as crystallization proceeds (panel c). Interestingly, many atoms classified as crystalline by scalar entropy appear in amorphous regions of the entropy band manifold — most notably in folded or bridged regions — suggesting that scalar entropy fails to capture key configurational nuances. The red circles in panel (b) mark such discrepancies at

.

To further investigate these structural groupings, we applied HDBSCAN to the UMAP representations (panels d–f). The resulting clusters broadly align with amorphous and crystalline regions, and boundary overlaps diminish as crystallization matures. Compared to scalar entropy, these clusters offer a more refined partitioning of the phase space, particularly in regions involving interfacial or partially ordered configurations.

The spatial distribution of these clusters is visualized in panels (g)–(i), showing particle-level reconstructions at , and , respectively. In the early stages (panel g), the differences in clustering are minimal. By (panel h), the entropy bands correctly classify folded-chain atoms misidentified by scalar entropy. In steady state (panel i), the entropy bands robustly distinguish the folded, bridged, and chain-end segments, underscoring their improved sensitivity to configurational heterogeneity.

While represents a spatial average within concentric radial shells and captures total local entropy, the two differ in their ability to resolve phase interfaces. Band-averaged entropy demonstrates improved separability between amorphous and crystalline regions, as evidenced by UMAP manifolds and HDBSCAN clustering results. However, this separation remains incomplete: the manifold does not exhibit fully disjoint clusters, and HDBSCAN classification near phase boundaries is sensitive to hyperparameters and density fluctuations. These ambiguities particularly affect interfacial or partially ordered atoms, where scalar descriptors, even band-averaged ones, struggle to provide consistent phase assignments.

To address this limitation, we now turn to the full directional entropy vector , which retains first-order angular information about the local entropy field. This vectorized representation is sensitive to configurational anisotropy and directional gradients, key signatures of folded structures, interfacial asymmetries, and structural motifs that are often overlooked by scalar metrics. In the next subsection, we examine whether offers improved phase discrimination and interface resolution, particularly compared to the crystallinity index.

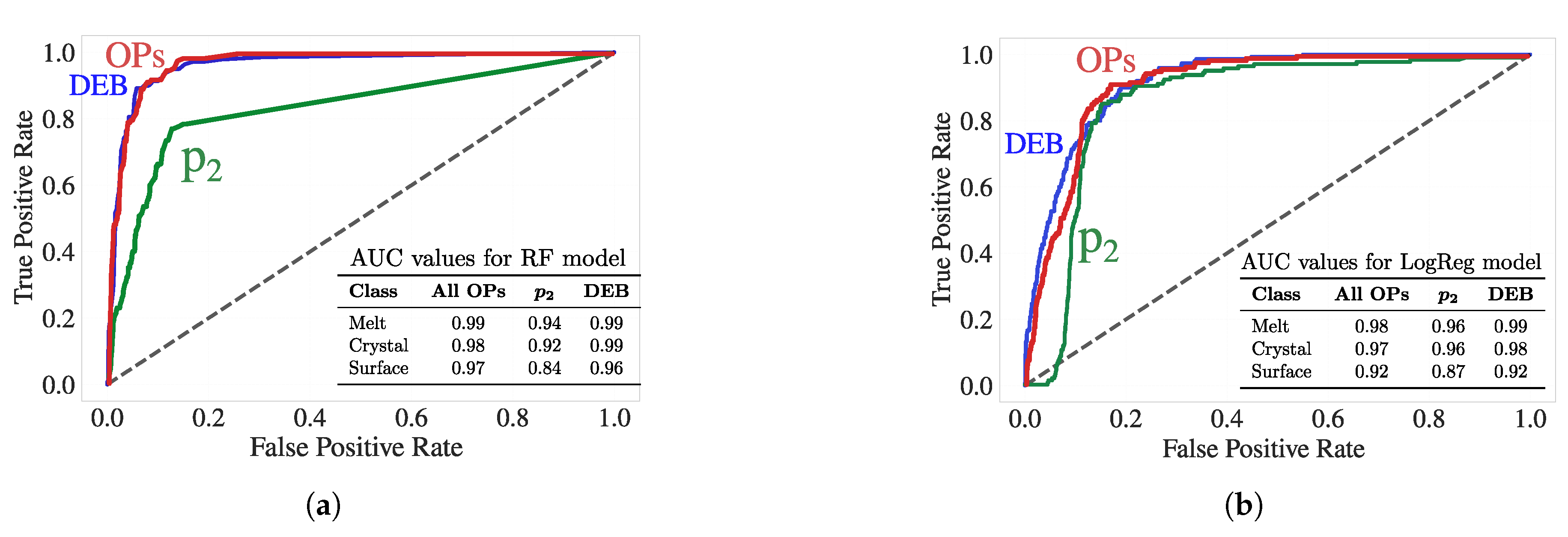

3.2.2. Comparison of Directional Entropy Bands (DEB),

, with the Crystallinity Index (C-Index) and Phase Boundaries

To evaluate the spatial and phase resolution capacity of the directional entropy bands, we applied UMAP to feature sets that comprise the full directional entropy vector

. These features include the band-averaged entropy, directional projections (

), the normalized angular moment (

), and the surface-weighted entropy gradient

. Full details of the structure of the feature are provided in

Section 2.2.3.

Figure 5 shows the embeddings of

in the same three key crystallization stages: transitional (

), intermediate (

), and steady state (

). Panels (a)–(c) display UMAP projections colored by the scalar entropy (

). These embeddings reveal smooth, though not sharply delineated, phase separation, particularly at later crystallization stages (panel c), where increasing interfacial heterogeneity becomes prominent. This outcome is intentional, as the set of characteristics includes the surface-weighted entropy gradient

, which improves sensitivity to transitional and boundary atoms. Excluding

leads to sharper melt–crystal separation in the manifold, but at the expense of interface resolution, which is essential to characterize crystal growth dynamics.

The surface-weighted entropy gradient parameter

plays a critical role in enhancing the sensitivity to interfacial structure. In this study, we selected

for

as a representative value that balances resolution and stability at different stages of crystallization. Qualitatively similar results are obtained for

values in the range of 0.1 to 2.0, with minor changes in the position of the inferred interface. Specifically, increasing

tends to bias the interfacial boundary slightly towards the crystalline side, reflecting a stronger surface weighting. This choice ultimately depends on the desired trade-off between strict geometric separation and the inclusion of interfacial disorder. A comparison of UMAP embeddings and C-index disagreement maps across the range

is provided in Appendix

Figure A4.

In general, directional components and together introduce sufficient angular and boundary sensitivity to delineate physically meaningful subpopulations - corresponding to melt, crystalline cores, and structurally complex interface regions - that are not easily distinguishable using scalar entropy alone or any other order parameter.

To further assess the effectiveness of

in resolving local phase identity, we focus on the intermediate crystallization stage (

), where phase boundaries are the most structurally uncertain.

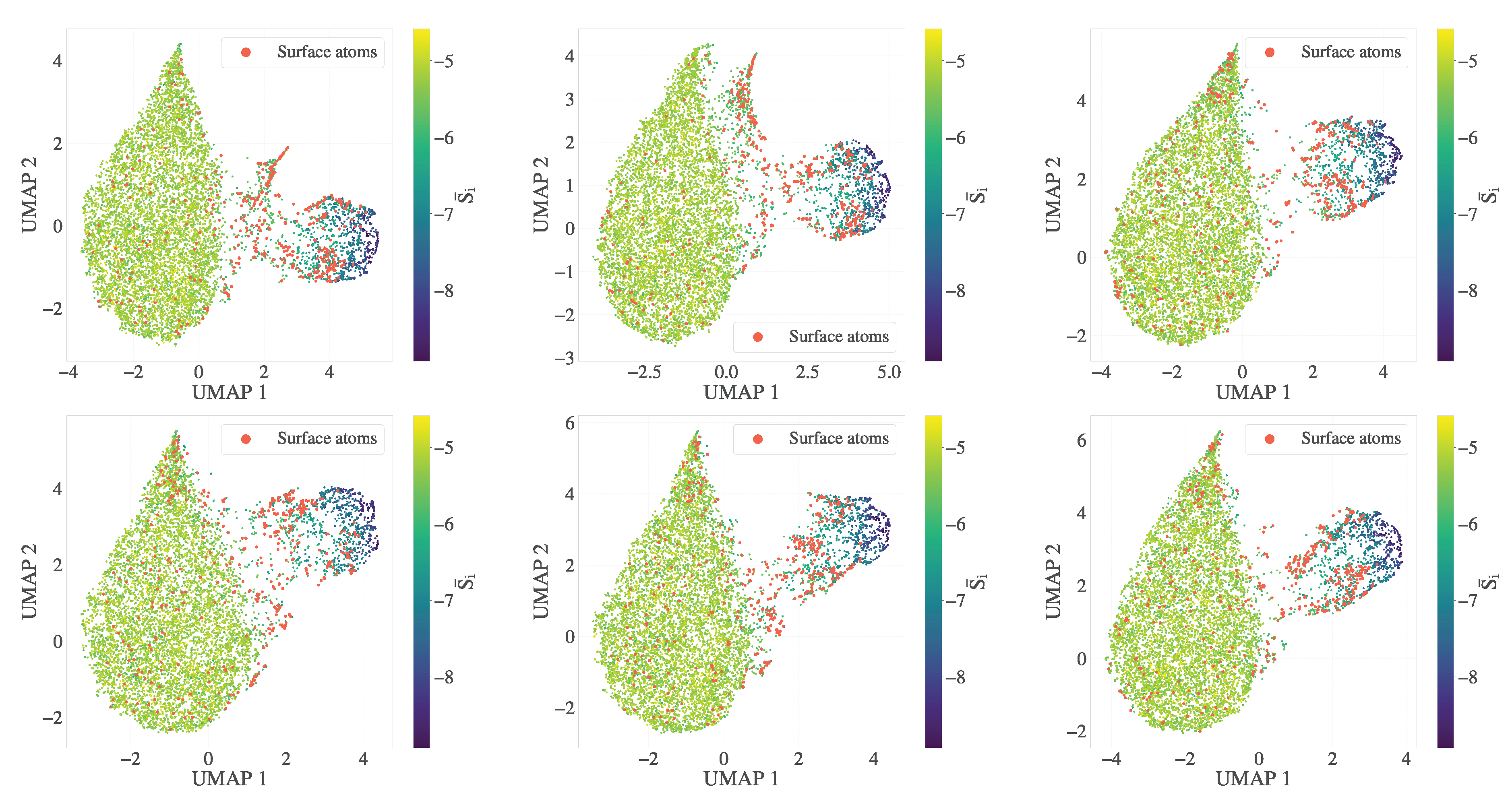

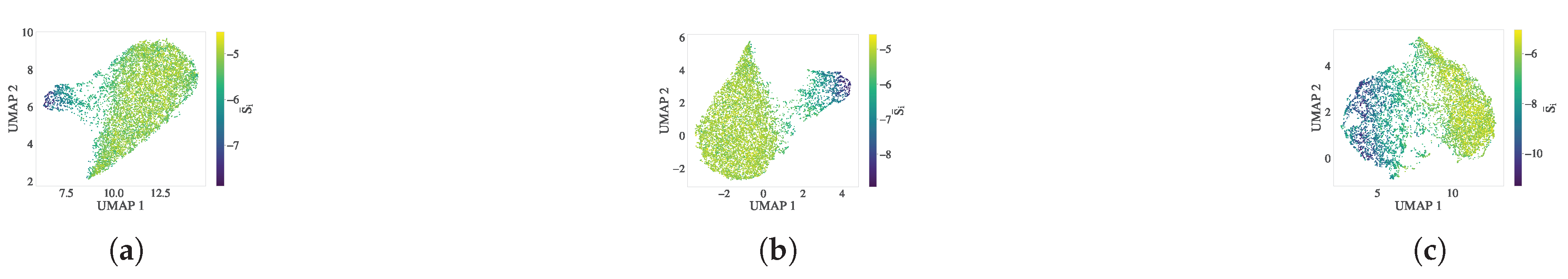

Figure 6 compares the directional entropy vectors with the C-index in four panels.

Panel (a) presents a map of the scalar entropy band (

), with atoms highlighted in red or blue to indicate disagreement with the C index: red atoms are labeled crystalline by the entropy bands but amorphous by the C index, while blue atoms show the opposite discrepancy. (b) Maps these discordant atoms onto a VMD [

83]-rendered snapshot of the polymer configuration. Orange atoms correspond to regions where both descriptors agree on crystallinity, while red and blue atoms lie predominantly at interfaces or folded chain regions. Panel (c) shows a contour plot of the manifold built from

, colored by discordance with the C-index. Compared with panel (a), the number of conflicting atoms is significantly reduced. (d) Improved consistency between DEB predictions and local structure from C-index results, with fewer discordant atoms (red/blue) on the surface of the crystalline regions.

These comparisons illustrate that directional entropy vectors align better with the physical morphology and reduce classification ambiguity at phase boundaries.

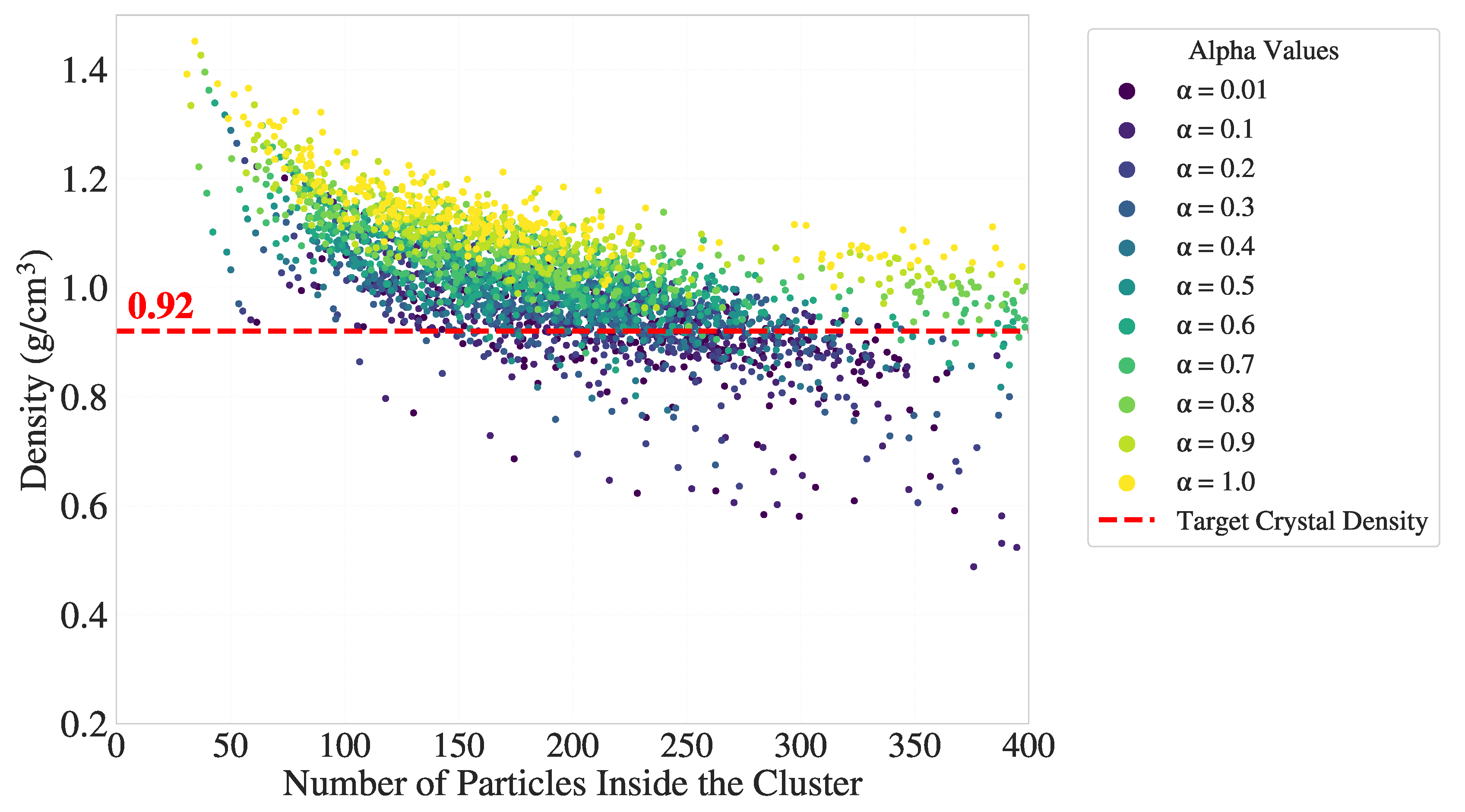

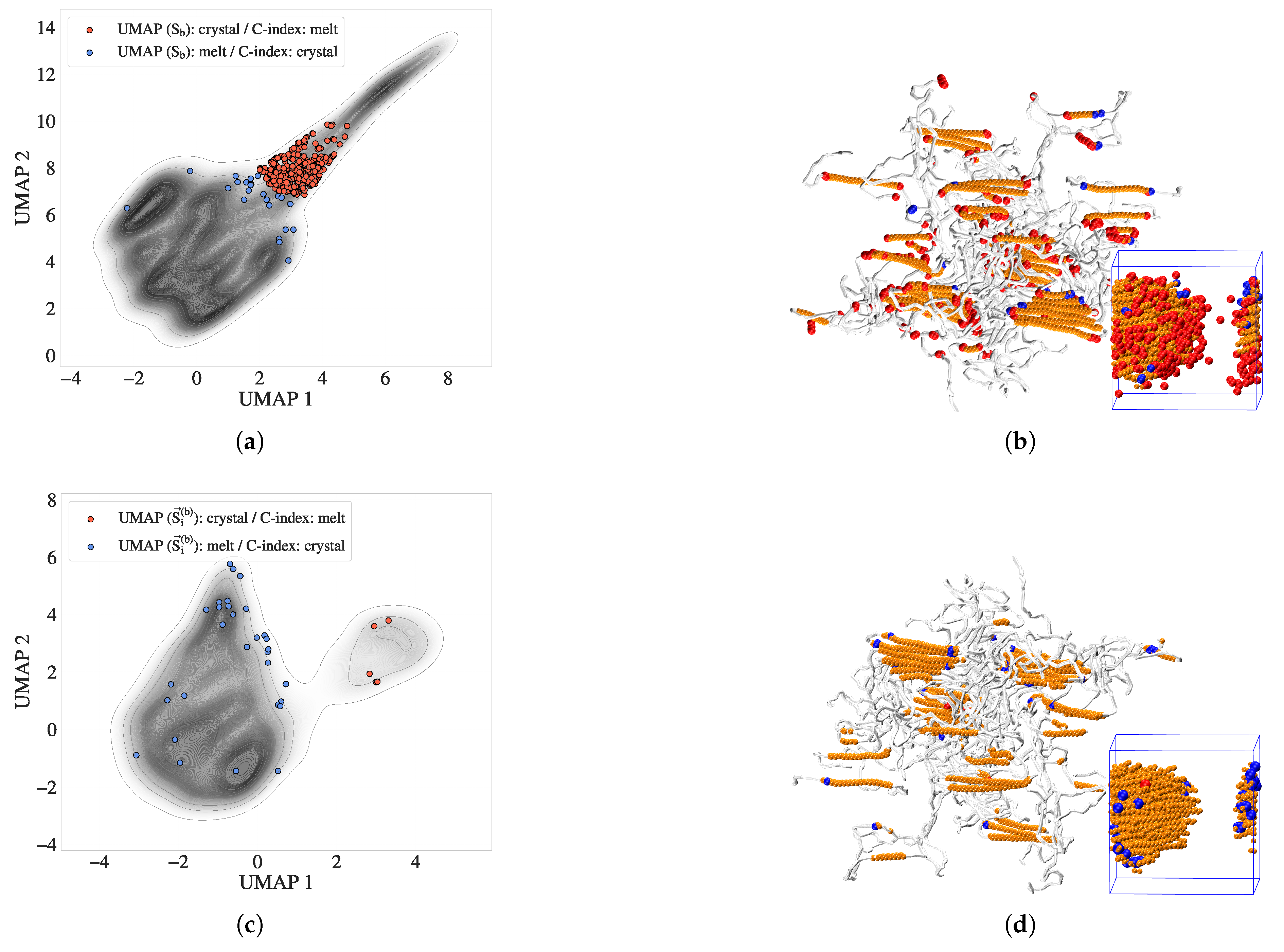

To further validate the ability of the directional entropy bands to resolve the interfacial structure, we adopted a geometric surface reference (’silver standard’) derived from alpha shapes constructed on the C-index-defined crystalline cluster. This approach identifies atoms located on the geometric boundary of the cluster at , independent of entropy-based criteria.

We examined the use of alpha shapes to define geometric boundaries on the C-index-defined crystalline cluster. Based on Appendix

Figure A3, a suitable range for the alpha parameter is

, where the balance between over-smoothing (too small

) and more sharp surface (too large

) is optimal. For the results shown in this section, we selected

to include a larger number of atoms on the crystal–melt boundary as surface atoms. This choice facilitates both a richer visual interpretation of interfacial behavior in UMAP space and a broader set of labels for subsequent classification tasks.

Figure 7 presents a complementary comparison in both feature space and real space. Panel (a) shows the UMAP embedding of

, where the silver standard surface atoms are colored red. These atoms form a distinct transitional group located between melt-like and crystalline clusters in the feature space, consistent with their physical interfacial role. (b) VMD rendering of the crystalline cluster (cyan), overlaid with red atoms denoting the alpha shape surface and blue atoms denoting additional DEB-inferred surface atoms to the alpha shape. The DEB-identified surface population closely matches or slightly extends the alpha-shaped boundary, suggesting that it captures both geometric and entropic signatures of the crystal–melt interface.

This correspondence highlights the potential of directional entropy bands to encode interfacial structure with high fidelity, capturing both geometric and entropic signatures of surface atoms. These findings motivate a deeper investigation into whether such features can be leveraged in supervised modeling tasks to systematically identify surface environments.

3.3. Model Explanation via Supervised Classification

3.3.1. Motivation and Approach

To further explore the structural information encoded in directional entropy bands, we adopt a supervised classification approach, not to demonstrate the superiority of any particular ML model, but to assess whether entropy-based features alone can reproduce known phase assignments and provide interpretable insights into interfacial structure. As target labels, we use the C-index derived in our previous work [

56], which combines clustering results from a broad set of conventional order parameters.

Our objective is to determine whether the features of the directional entropy band, derived solely from differential entropy estimates, are sufficiently expressive to learn phase distinctions and surface localization in a physically interpretable way. In particular, our aim is to: Fit supervised models to establish the predictive power of entropy bands without relying on geometric or symmetry-based descriptors, Examine label uncertainty near interfacial regions to assess robustness of entropy-based boundaries, Identify the most informative subset of components of the entropy band by analyzing the importance of characteristics.

This framework allows us to assess the potential of entropy-derived descriptors to serve as early, physically grounded indicators of interfacial structure, complementing or even anticipating more complex symmetry-based features. In particular, in our previous work [

56], we showed that scalar entropy outperforms traditional order parameters in detecting early stage crystallization in entangled polymer chains. Building on that result, the present framework investigates whether directional entropy band features, enhanced with interfacial sensitivity, can improve both interpretation and predictive performance in resolving phase boundaries and surface environments.

3.3.2. Data Preparation

The supervised classification task used band descriptors of directional entropy, including band-averaged entropy (), directional projections (, , ), max-based gradient estimate (), and the surface-weighted entropy gradient (). All continuous features were standardized to zero mean and unit variance for the random forest model. The data set was divided into training subsets (80%) and testing subsets (20%) using stratified sampling to maintain class balance.

3.3.3. Model Selection and Training

We evaluated both a Random Forest (RF) classifier and a Logistic Regression (LogReg) model to assess the separability of surface atoms based solely on entropy-derived descriptors. The RF model, known for capturing nonlinear feature interactions and robustness to colinearity, was used as a high-capacity baseline. The hyperparameters (number of estimators and maximum tree depth) were tuned through 5-fold stratified cross-validation using grid search to maximize the mean area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

To complement this, we also trained a Logistic Regression model, which provides a linear and additive mapping between input features and predicted probabilities. This model allows for direct interpretation of the feature weights, making it especially suited to identifying combinations of entropy band components that align with a physically meaningful interfacial structure. Our goal here is not to optimize predictive performance per se, but to evaluate whether a linear combination of entropy-based features is sufficient to distinguish surface environments, a valuable step toward building mechanistic understanding of nucleation and growth processes.

The surface atom labels used for classification were generated using alpha shapes constructed in the C-index-defined crystalline cluster, as described in

Section 3.2.2. Although alpha-shape surfaces are geometric proxies and not exact thermodynamic boundaries, they serve as a useful silver standard for assessing the extent to which directional entropy bands capture interfacial structure.

3.3.4. Performance Evaluation: ROC Analysis

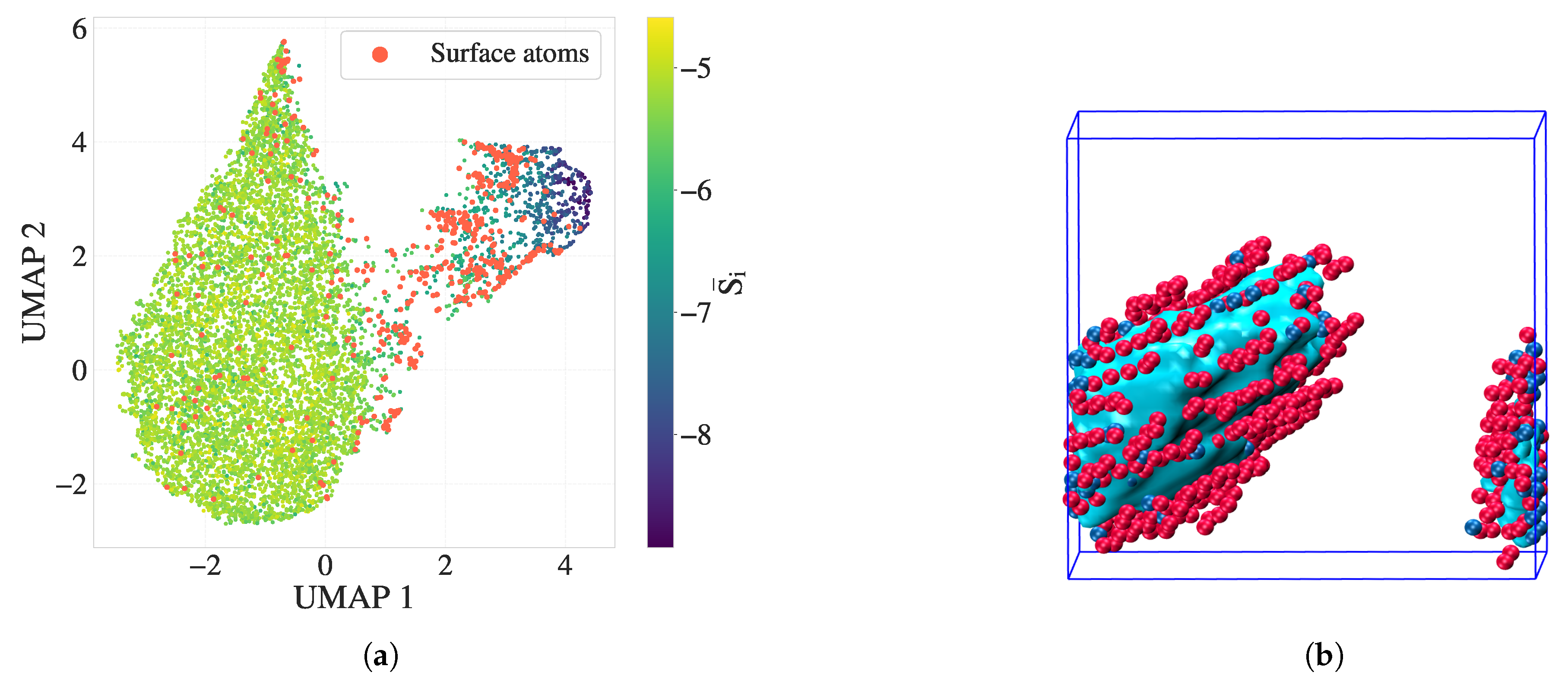

Figure 8 presents the ROC curves for the surface class using both the RF and LogReg models trained on three sets of characteristics:

, the set of conventional scalar OPs (excluding entropy) and the proposed DEB descriptors. Despite the silver-standard ground truth labels (i.e., the C index clusters) being derived using the OPs set (including scalar entropy), DEB descriptors alone achieve comparable or even superior predictive performance. For surface classification, DEB reaches AUCs of 0.92 (LogReg) and 0.96 (RF), outperforming

(0.87 and 0.84) and closely matching the OPs group (0.92 and 0.97), which aggregates more variables.

These results underscore a key contribution of this work: DEB descriptors, built solely from differential entropy without relying on high-order symmetry terms, are not only physically interpretable but also highly predictive of interfacial environments. The fact that DEB matches the performance of a broader OP set, even though the ground-truth clustering was derived from those OPs, highlights its robustness. Furthermore, in light of our previous findings that entropy is a sensitive early stage indicator of nucleation, these entropy-based features may offer a more timely and mechanistically meaningful route toward understanding crystallization front propagation and interfacial dynamics in polymeric systems.

3.3.5. Uncertainty of Cluster_Label

To quantify the uncertainty of the label in interfacial regions, we manually inspected 600 atoms selected near the boundaries of the UMAP cluster (surface atoms) in three representative time steps (200 atoms per timestep). Approximately 10 atoms (∼1.7%) were clearly mislabeled, while more than 100 atoms (∼17%) exhibited ambiguous labeling due to their proximity to phase interfaces. Conservatively, we adopt an estimate of uncertainty ∼ 2% for clearly mislabeled atoms, acknowledging a potential upper bound of ∼18% if ambiguous cases are considered. This manually estimated uncertainty provides a practical ceiling for classification AUCs, beyond which additional predictive gains may reflect overfitting to label noise rather than improved physical resolution of the interfacial structure.

3.3.6. Forward Feature Selection and Model Interpretation

Using both logistic regression and XGBoost classifiers, we applied forward feature selection (FFS) with five-fold stratified cross-validation to identify key directional entropy band descriptors for surface atom classification. The descriptors were added one at a time until the AUC of the test set plateaued or reached the noise floor determined by manual inspection (

Section 3.3.5).

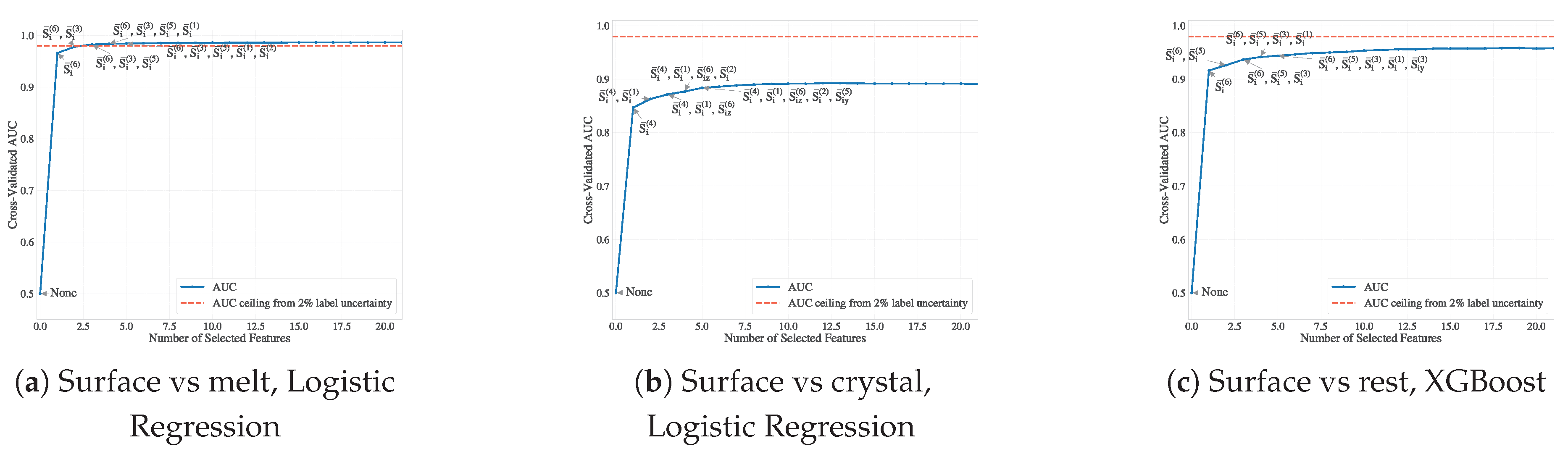

As shown in

Figure 9, the performance of the classifier was rapidly saturated, usually after incorporating only 3 to 5 directional features of the entropy band. For example, the XGBoost model reached an AUC of 0.955 for the surface vs. rest classification (including both melt and crystal), while logistic regression plateaued at 0.985 for surface vs. melt and 0.89 for surface vs. crystal. Given our estimated labeling uncertainty of 1–2%, this corresponds to a practical AUC ceiling of approximately 0.98–0.99

1, so the inclusion of additional features led to only marginal gains. This plateau behavior indicates potential overfitting to boundary noise and confirms that a small, physically significant subset of entropy band components suffices for accurate surface classification. Including additional features risks fitting spurious correlations rather than capturing meaningful structure, especially in interfacial regions where labels are intrinsically uncertain due to geometric or thermodynamic ambiguity.

Logistic regression was also applied separately to classify surface atoms against either melt or crystal environments. This decomposition avoids confounding effects in three-class linear models and reflects the inherent physical asymmetry between the two interfacial types. In the main model here, constructed with for alpha-shape surfaces and for , we observed that surface–crystal boundaries were harder to distinguish, consistent with tighter packing and reduced entropy gradients near the crystalline domains. These surface atoms are more deeply embedded and less geometrically distinct from the bulk, whereas the surface–melt interface exhibits broader spatial separation and more pronounced configurational contrast.

To examine whether the observed asymmetry is due to model resolution or label definition rather than intrinsic structural complexity, we repeated the classification using hyperparameters:

for the alpha-shaped surface and

for the weighting of the entropy gradient in

. This configuration yields a more spacious cluster and a thinner interfacial layer (i.e., fewer surface atoms). As shown in Appendix

Figure A5, the surface–crystal classification performance improved to AUC > 0.91, suggesting that the earlier difficulty was partially due to label ambiguity in those definitions. However, the modest gain in AUC (approximately three percentage points) implies that learning the surface–crystal boundary remains intrinsically more challenging using linear decision boundaries (here, logistic regression). This refinement also came at the cost of surface melt classification, which decreased to AUC ≃ 0.95, probably due to the reduced spatial distinction when the surface region is narrowly defined with lower values

.

These results suggest that surface atom classification using DEB descriptors is consistently robust across different interface definitions. The set of DEB components required to reach performance saturation may vary depending on the classifier and hyperparameters, but the overall predictive power remains strong. Importantly, we observe that AUC values plateau after inclusion of only a few DEB features, underscoring their relevance and sufficiency for identifying interfacial atoms in polymeric systems with varying structural resolution.

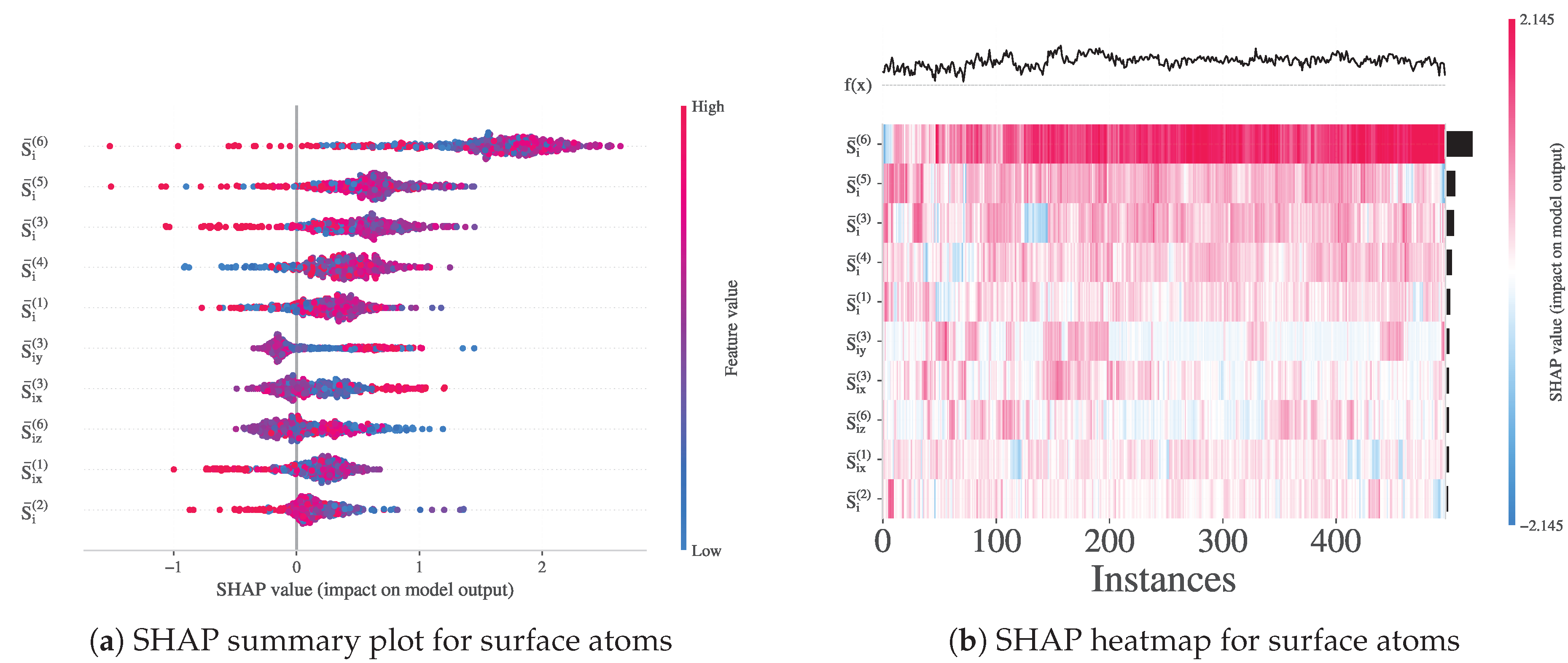

To capture non-linear interactions among entropy band descriptors, we also trained an XGBoost classifier for surface vs. rest (melt + crystal). This model achieved a high AUC (≥ 0.985) using only 3-4 features, indicating a strong discriminative power of the directional entropy bands. SHAP values were computed to interpret these non-linear decision boundaries, focusing on surface atoms and stratifying results by radial and longitudinal surface geometries. Together, these results confirm that directional entropy bands are physically grounded, compact, and effective variables for surface detection and provide a foundation for future modeling of interfacial dynamics.

3.3.7. Feature Importance and Local Structure Patterns

To interpret the trained non-linear XGBoost classifier for surface detection, we calculated SHAP values over the subset of surface atoms (Cluster_Label = 1). The SHAP summary plot (

Figure 10a) highlights that the most influential features are the band-averaged entropies

, particularly from the outermost and midrange shells (

, 5, and 3), along with directional components such as

and

. This confirms the central role of band-resolved entropy profiles in characterizing interfacial order. In particular, both positive and negative SHAP values appear across bands, indicating nonmonotonic interactions between local order and surface classification. The heatmap (

Figure 10b) further reveals structured, non-random patterns in SHAP values across atoms, with feature contributions varying coherently between instances. These results demonstrate that directional entropy bands capture reproducible interfacial features with high discriminative value, validating their use in subsequent modeling of surface and transition dynamics.

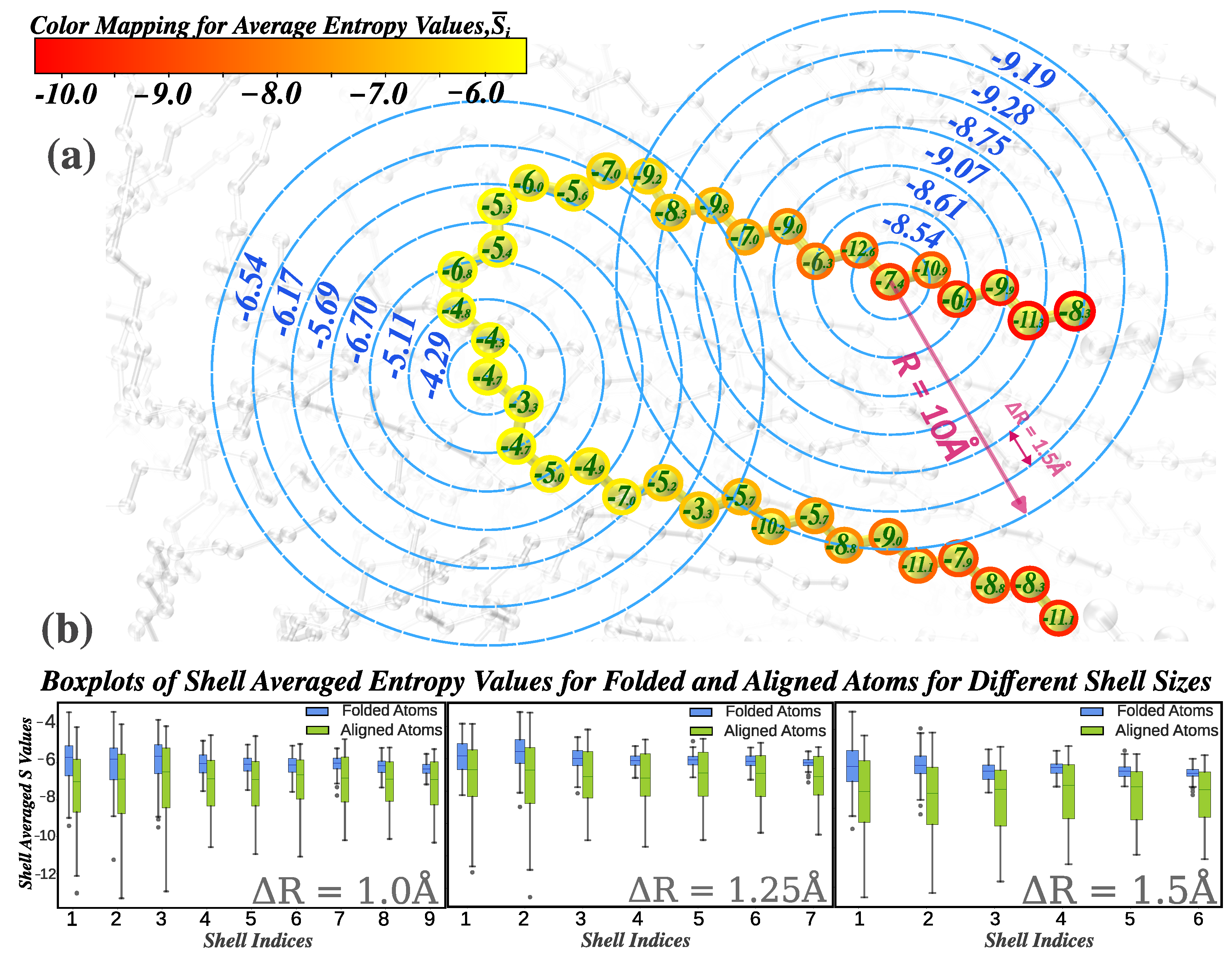

Figure 1.

Definition of entropy bands: (a) Entropy fingerprint vectors for random particles, with a color bar indicating scalar average entropy. Particle labels show non-averaged entropy values, and shell labels represent entropy from distinct radial shells (); (b) Box plots of shell-averaged entropy values for randomly selected folded and aligned atoms across varying shell thicknesses (), highlighting the resolution impact of .

Figure 1.

Definition of entropy bands: (a) Entropy fingerprint vectors for random particles, with a color bar indicating scalar average entropy. Particle labels show non-averaged entropy values, and shell labels represent entropy from distinct radial shells (); (b) Box plots of shell-averaged entropy values for randomly selected folded and aligned atoms across varying shell thicknesses (), highlighting the resolution impact of .

Figure 2.

Comparison of SOAP dimensionality reduction pipelines at . (a)–(c) PCA to 15 components + UMAP + HDBSCAN: (a) 2D embedding with 95.59% explained the retained variance; (b) colored by ; (c) Dihedral distribution for different clusters. Dihedral proportions for cluster A (64% trans, 31% gauche) are shown in inset pie chart of panel (b). (d)–(f) PCA to 25 components + UMAP + HDBSCAN: (d) embedding with 97.60% explained the retained variance; (e) colored by ; (f) Dihedral distribution for different clusters with dihedral proportions (46% trans, 49% gauche) shown in inset pie chart in panel (e). (g)–(i) Direct UMAP + HDBSCAN: cleanest separation and consistent dihedral interpretation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of SOAP dimensionality reduction pipelines at . (a)–(c) PCA to 15 components + UMAP + HDBSCAN: (a) 2D embedding with 95.59% explained the retained variance; (b) colored by ; (c) Dihedral distribution for different clusters. Dihedral proportions for cluster A (64% trans, 31% gauche) are shown in inset pie chart of panel (b). (d)–(f) PCA to 25 components + UMAP + HDBSCAN: (d) embedding with 97.60% explained the retained variance; (e) colored by ; (f) Dihedral distribution for different clusters with dihedral proportions (46% trans, 49% gauche) shown in inset pie chart in panel (e). (g)–(i) Direct UMAP + HDBSCAN: cleanest separation and consistent dihedral interpretation.

Figure 3.

Dimensionality reduction and clustering of SOAP descriptors incorporating 20 consecutive timesteps around . (a) 2D UMAP embedding of PCA(25)-reduced SOAP vectors (6480 dimensions per particle) with HDBSCAN clustering. (b) Particles are colored based on -based crystallinity classification. The crystalline cluster closely aligns with the cluster identified by HDBSCAN, as the yellow-green points correspond with the orange points identified through clustering in the 2D embedding. However, instantaneous dihedral information was not preserved in this analysis due to the concatenation of temporal data.

Figure 3.

Dimensionality reduction and clustering of SOAP descriptors incorporating 20 consecutive timesteps around . (a) 2D UMAP embedding of PCA(25)-reduced SOAP vectors (6480 dimensions per particle) with HDBSCAN clustering. (b) Particles are colored based on -based crystallinity classification. The crystalline cluster closely aligns with the cluster identified by HDBSCAN, as the yellow-green points correspond with the orange points identified through clustering in the 2D embedding. However, instantaneous dihedral information was not preserved in this analysis due to the concatenation of temporal data.

Figure 4.

UMAP analysis of shell-based entropy vectors (entropy bands) combined with enthalpy values for three key crystallization stages. (a)–(c) UMAP embeddings for , , and , respectively, colored by scalar entropy. Red circles in (b) highlight discrepancies where scalar entropy classifies particles as crystalline, yet their embedding position suggests otherwise. (d)–(f) HDBSCAN clustering applied to the UMAP embeddings of entropy bands, identifying two major structural populations. (g)–(i) Structural reconstructions of the clusters at , , and , respectively. Misclassified particles from panel (b) appear in folded or bridged segments in panel (h), demonstrating the improved sensitivity of entropy bands in capturing configurational complexity beyond scalar entropy metrics. In panel (i), red particles represent disordered regions—primarily folded segments—that are incorrectly classified as crystalline by scalar entropy (panel c), but correctly identified as amorphous by scalar entropy bands. Orange particles correspond to atoms consistently classified as crystalline by both methods.

Figure 4.

UMAP analysis of shell-based entropy vectors (entropy bands) combined with enthalpy values for three key crystallization stages. (a)–(c) UMAP embeddings for , , and , respectively, colored by scalar entropy. Red circles in (b) highlight discrepancies where scalar entropy classifies particles as crystalline, yet their embedding position suggests otherwise. (d)–(f) HDBSCAN clustering applied to the UMAP embeddings of entropy bands, identifying two major structural populations. (g)–(i) Structural reconstructions of the clusters at , , and , respectively. Misclassified particles from panel (b) appear in folded or bridged segments in panel (h), demonstrating the improved sensitivity of entropy bands in capturing configurational complexity beyond scalar entropy metrics. In panel (i), red particles represent disordered regions—primarily folded segments—that are incorrectly classified as crystalline by scalar entropy (panel c), but correctly identified as amorphous by scalar entropy bands. Orange particles correspond to atoms consistently classified as crystalline by both methods.

Figure 5.

UMAP embeddings of the directional entropy vector at three crystallization stages: (a) , (b) , and (c) , colored by scalar entropy . The embeddings reveal smooth phase separation and reflecting the influence of interfacial and directional features.

Figure 5.

UMAP embeddings of the directional entropy vector at three crystallization stages: (a) , (b) , and (c) , colored by scalar entropy . The embeddings reveal smooth phase separation and reflecting the influence of interfacial and directional features.

Figure 6.

Comparison of scalar entropy bands and directional entropy vectors with the Crystallinity Index (C-index) at . (a) Contour map of scalar entropy bands (), with discordant atoms highlighted: red atoms are classified as crystalline by entropy bands but amorphous by the C-index, and blue atoms vice versa. (b) VMD snapshot of the same atoms from (a), showing their spatial distribution. Orange atoms represent crystalline regions where both methods agree; red and blue atoms lie predominantly at interfaces and folded chain segments. (c) UMAP embedding of the directional entropy vector , showing reduced phase disagreement relative to (a). (d) VMD visualization of (c), confirming improved agreement with local structure and enhanced resolution of interfacial atoms.

Figure 6.

Comparison of scalar entropy bands and directional entropy vectors with the Crystallinity Index (C-index) at . (a) Contour map of scalar entropy bands (), with discordant atoms highlighted: red atoms are classified as crystalline by entropy bands but amorphous by the C-index, and blue atoms vice versa. (b) VMD snapshot of the same atoms from (a), showing their spatial distribution. Orange atoms represent crystalline regions where both methods agree; red and blue atoms lie predominantly at interfaces and folded chain segments. (c) UMAP embedding of the directional entropy vector , showing reduced phase disagreement relative to (a). (d) VMD visualization of (c), confirming improved agreement with local structure and enhanced resolution of interfacial atoms.

Figure 7.

Surface atom identification using the C-index alpha shape (silver standard) and directional entropy bands at . (a) UMAP embedding of , with surface atoms highlighted in red. These atoms form a transitional group between melt-like and crystalline clusters. (b) VMD snapshot of the crystalline cluster (cyan), overlaid with silver-standard surface atoms (red) and DEB-inferred surface atoms (blue). The strong correspondence illustrates the interface-resolving capability of directional entropy bands.

Figure 7.

Surface atom identification using the C-index alpha shape (silver standard) and directional entropy bands at . (a) UMAP embedding of , with surface atoms highlighted in red. These atoms form a transitional group between melt-like and crystalline clusters. (b) VMD snapshot of the crystalline cluster (cyan), overlaid with silver-standard surface atoms (red) and DEB-inferred surface atoms (blue). The strong correspondence illustrates the interface-resolving capability of directional entropy bands.

Figure 8.

ROC curves for surface classification using (a) RF, and (b) LogReg models, trained on three feature sets: , the set of conventional scalar OPs (excluding entropy), and DEB. Only the surface-class ROC curves are shown for clarity. AUC values for melt, crystal, and surface classes are reported in the inset tables. Despite the silver truth labels being derived from the full OP set (including entropy), the DEB features alone exhibit competitive or superior surface-prediction performance.

Figure 8.

ROC curves for surface classification using (a) RF, and (b) LogReg models, trained on three feature sets: , the set of conventional scalar OPs (excluding entropy), and DEB. Only the surface-class ROC curves are shown for clarity. AUC values for melt, crystal, and surface classes are reported in the inset tables. Despite the silver truth labels being derived from the full OP set (including entropy), the DEB features alone exhibit competitive or superior surface-prediction performance.

Figure 9.

Forward feature selection (FFS) results using ROC-AUC as the performance metric. Dashed red and gray lines denote uncertainty ceilings derived from 2% clearly mislabeled atoms and 18% ambiguous labels, respectively.

Figure 9.

Forward feature selection (FFS) results using ROC-AUC as the performance metric. Dashed red and gray lines denote uncertainty ceilings derived from 2% clearly mislabeled atoms and 18% ambiguous labels, respectively.

Figure 10.

SHAP value analysis for the XGBoost model trained to distinguish surface atoms. (a) Summary plot showing the contribution of each feature across atoms labeled as surface (Cluster_Label = 1). (b) Heatmap visualization of SHAP values across surface atoms, illustrating consistent patterns in the importance of band entropy features.

Figure 10.

SHAP value analysis for the XGBoost model trained to distinguish surface atoms. (a) Summary plot showing the contribution of each feature across atoms labeled as surface (Cluster_Label = 1). (b) Heatmap visualization of SHAP values across surface atoms, illustrating consistent patterns in the importance of band entropy features.