1. Introduction

Neuromuscular adaptations are foundational to

improvements in athletic performance, directly influencing strength, power,

speed, and injury resilience. Strength training, characterized by resistance

exercises targeting maximal force production, typically induces muscular

hypertrophy and neural improvements, enhancing motor unit recruitment and

synchronization. Plyometric training, involving rapid stretch-shortening

cycles, primarily develops neuromuscular efficiency, power, and reactive

strength by optimizing muscle activation patterns and stiffness properties.

Despite extensive empirical research into these

training methods, the precise mechanisms underpinning neuromuscular adaptations

remain partially understood, and the optimization of combined strength and

plyometric training protocols remains challenging. Computational modeling,

notably musculoskeletal simulation software like OpenSim, provides powerful

tools for dissecting the intricate biomechanical and physiological adaptations

occurring in response to diverse training stimuli. Further integration with artificial

intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning algorithms, enables

sophisticated predictive analyses, potentially revolutionizing training

prescription and injury prevention strategies.

The neuromuscular adaptations explored in this

study hold significant practical implications across various sports

disciplines, including athletics, soccer, basketball, and volleyball. Enhanced

muscular activation, increased joint stability, and improved force development

directly contribute to superior performance in sport-specific tasks such as

sprinting, vertical and horizontal jumping, rapid directional changes, and

efficient energy transfer during complex movements. Coaches and athletes in

these disciplines could significantly benefit from understanding and

strategically applying the findings to optimize training protocols, boost

competitive performance, and enhance injury resilience.

This study aims to address existing gaps by

presenting an integrated computational analysis to simulate and predict

neuromuscular adaptations arising from strength and plyometric training. By

leveraging OpenSim-based modeling alongside machine learning techniques, the

current research explores individual and combined effects of these training

modalities. The findings are expected to enhance the understanding of specific

neuromuscular responses, inform evidence-based training practices, and

establish foundations for future research in computational sports science.

1.2. Theoretical Background

Neuromuscular adaptations constitute fundamental

mechanisms underlying enhancements in athletic performance, influencing

strength, power, speed, coordination, and injury resilience. These adaptations

occur through complex interactions between neural and muscular systems, driven

by specific training stimuli and resulting physiological responses. A thorough

understanding of these adaptations is essential for optimizing athletic

training and performance outcomes [1–3].

At a physiological level, neuromuscular adaptations

involve intricate processes within the central nervous system (CNS) and

skeletal muscles. Neural adaptations specifically encompass enhanced motor unit

recruitment, increased motor neuron firing rates, and improved synchronization

of motor unit activation. A motor unit, defined as a single motor neuron and

the muscle fibers it innervates, serves as the fundamental functional unit

responsible for muscle contractions. Initiation of muscular contractions occurs

when action potentials travel along motor neurons, triggering neurotransmitter

release at neuromuscular junctions and facilitating muscle fiber depolarization

and subsequent contraction. Regular exposure to training stimuli significantly

enhances the efficiency, synchronization, and magnitude of these neuromuscular

processes, leading to notable improvements in muscle strength, coordination,

and overall athletic capabilities [4–6].

Strength training primarily induces neuromuscular

adaptations via mechanical loading, stimulating both neural and muscular

pathways. Neural adaptations include improved motor unit recruitment, increased

motor unit firing frequency, and enhanced synchronization of motor units. Such

neural changes contribute significantly to gains in muscular strength,

especially during early training phases, even before notable muscular

hypertrophy occurs [7–9].

Muscular adaptations resulting from strength

training predominantly involve hypertrophy, characterized by an increase in

muscle fiber cross-sectional area. This structural change directly enhances

force-generating capacity. Additionally, strength training facilitates shifts

in muscle fiber type composition, typically promoting transitions towards

fast-twitch muscle fibers, which possess greater force-production potential and

responsiveness to high-intensity exercise [10–13].

In contrast, plyometric training emphasizes rapid,

explosive muscle contractions through the utilization of the stretch-shortening

cycle (SSC). This training modality predominantly stimulates improvements in

neuromuscular efficiency, reactive strength, and power output. Key adaptations

from plyometric training include increased muscle-tendon stiffness, optimized

timing and magnitude of muscle activation patterns, and enhanced stretch reflex

sensitivity, collectively resulting in improved explosive performance [14–16].

The stretch-shortening cycle represents a crucial

biomechanical mechanism wherein a rapid eccentric muscle contraction

immediately precedes a concentric contraction. Effective use of the SSC enables

athletes to produce maximal force and power output rapidly, critical for

actions such as sprinting, jumping, and rapid directional changes [17–19].

While both strength and plyometric training

independently foster distinct adaptations, integrating these methods within

training programs could yield synergistic effects, further augmenting athletic

performance. However, optimal strategies for combining these modalities remain

a subject of ongoing investigation due to the complexity of physiological

interactions involved [20,21].

Computational musculoskeletal modeling has emerged

as a powerful tool for investigating biomechanical and physiological

adaptations induced by different training stimuli. Platforms such as OpenSim

facilitate detailed analyses of muscle activation patterns, joint kinetics, and

neuromechanical interactions, offering insights beyond what can be readily

observed in experimental settings alone [22,23].

Moreover, integrating computational modeling with

artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning algorithms, expands the

potential for predictive analysis and optimization of training interventions.

Machine learning models leverage extensive biomechanical and physiological data

to predict individualized adaptation trajectories, enabling precise adjustments

to training variables tailored to specific athletic goals [25–27].

This integrative computational approach provides

unprecedented opportunities to dissect the mechanisms underpinning

neuromuscular adaptations comprehensively. By simulating various training

scenarios, researchers can explore the nuances of neuromuscular responses,

refine training prescriptions, and enhance individualized training

effectiveness while minimizing injury risks [28,29].

In practice, applying computational and AI-driven

analyses enables sports scientists and practitioners to move beyond generalized

training protocols, developing highly individualized programs based on

predictive outcomes. This precision-based methodology could revolutionize

current practices in sports training and rehabilitation, ensuring athletes

receive optimal, evidence-based interventions.

Furthermore, computational approaches help address

limitations inherent in traditional empirical studies, such as ethical

concerns, logistical constraints, and participant variability. Through

computational simulations, researchers can systematically manipulate specific

training variables and observe detailed neuromuscular responses, providing

robust and controlled environments for testing hypotheses and refining

theoretical models [30–32].

Current research trends increasingly recognize the

value of interdisciplinary collaboration, integrating biomechanics, physiology,

data science, and artificial intelligence. Such integrative approaches enhance

the understanding of neuromuscular adaptation processes, facilitate the

development of innovative training methodologies, and encourage the translation

of scientific knowledge into practical sports applications.

Despite the potential advantages, challenges remain

in ensuring computational models accurately reflect the complex biological

realities of human neuromuscular systems. Model validation, calibration, and

refinement using empirical data are crucial steps in guaranteeing the

reliability and applicability of computational findings in practical settings [33–35].

Future research directions include refining

computational models to incorporate individualized athlete data, enhancing

predictive accuracy, and expanding simulation capabilities. Additionally,

exploring interactions between neuromuscular adaptations and other

physiological systems through integrated computational frameworks will further

enrich understanding and application.

Ultimately, harnessing computational modeling and

artificial intelligence in the context of neuromuscular training represents a

promising frontier in sports science. It offers significant potential for

optimizing athletic performance, preventing injuries, and advancing the broader

field of exercise and health research.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological model employed in this study

integrates advanced musculoskeletal modeling techniques with powerful machine

learning algorithms, establishing a rigorous and innovative basis for

investigating neuromuscular adaptations. Leveraging detailed computational

simulations and sophisticated predictive analytics, the procedures described

herein ensure precision, reproducibility, and practical applicability,

providing a robust foundation for understanding and optimizing training-induced

effects on athletic performance. To clearly illustrate the methodological

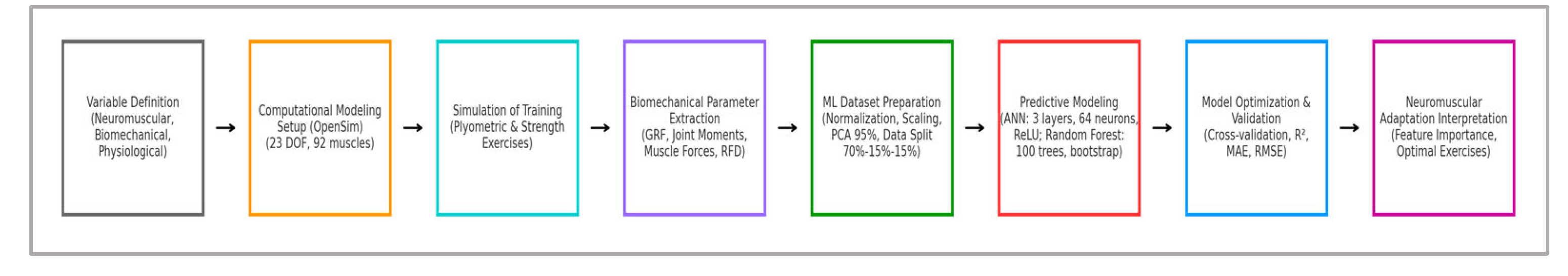

framework described above,

Figure 1

provides a schematic overview of the integrated computational modeling and

predictive analysis process employed in this study.

The methodological flow includes defining

neuromuscular, biomechanical, and physiological variables, setting up the

computational musculoskeletal model in OpenSim, simulating specific plyometric

and strength training exercises, extracting key biomechanical parameters (e.g.,

ground reaction forces, joint moments, muscle forces, rate of force

development), preparing datasets through normalization, scaling, principal

component analysis (PCA, 95% explained variance), and dataset partitioning (70%

training, 15% validation, 15% testing), performing predictive modeling using

artificial neural networks (ANN, three hidden layers, 64 neurons each, ReLU

activation function) and Random Forest regression (100 trees, bootstrap),

optimizing and validating models via cross-validation, hyperparameter tuning,

and performance metrics (R², MAE, RMSE), and finally interpreting neuromuscular

adaptations by analyzing feature importance, identifying optimal exercise

combinations, and providing training recommendations.

2.1. Computational Modeling Setup (OpenSim)

The computational analysis of neuromuscular

adaptations was conducted using OpenSim (version 4.4), an extensively validated

open-source musculoskeletal modeling software. OpenSim enables detailed

biomechanical simulations by solving equations of motion through inverse and

forward dynamics techniques, facilitating accurate estimations of joint

moments, muscle activations, and mechanical outputs [36].

The musculoskeletal model selected for this study

included 23 degrees of freedom and 92 musculotendon actuators, representing

major muscles of the lower limbs. The generic model was scaled precisely to

replicate a typical young adult athlete (height: 180 cm; body mass: 75 kg).

Scaling procedures involved adjusting segment lengths, inertial properties, and

muscle-tendon parameters proportionally according to anthropometric ratios

derived from standard reference databases [37].

Inverse kinematics analyses were conducted to

determine joint angles by minimizing marker-position errors, ensuring accuracy

within 2 cm. Inverse dynamics were subsequently performed to calculate joint

moments, utilizing ground reaction forces and measured kinematics as inputs,

based on Newton-Euler equations implemented numerically within OpenSim [38].

Static optimization methods were applied to

estimate muscle activation patterns required to produce calculated joint

moments. Specifically, this procedure minimized the sum of squared muscle

activations:

subject to where ai is the muscle activation for muscle i, Fm,i represents muscle force, rm,i is the moment arm for muscle i, and Mj indicates the net joint moment. Muscle forces were constrained physiologically, ensuring activations remained within realistic bounds (0 ≤ ai ≤ 1).

All simulations utilized consistent initial conditions, representing a resting state with zero initial joint velocities and normalized initial muscle activations. Integration settings in OpenSim, such as integrator accuracy (1e-5) and timestep (0.001 s), were carefully chosen to balance computational efficiency with solution stability. Outcomes from these simulations served as robust baselines for subsequent analyses of plyometric and strength training interventions.

The selection of exercises simulated in this study was based on extensive evidence from the existing sports science literature, demonstrating their effectiveness in eliciting significant neuromuscular adaptations relevant to athletic performance. Specifically, the back squat, deadlift, and leg press are widely documented for their capacity to enhance maximal strength and muscular coordination, while vertical jumps, horizontal broad jumps, and drop jumps have been consistently shown to effectively improve explosive power and reactive strength. This strategic choice of exercises ensured comprehensive coverage of neuromuscular adaptations essential for optimizing athletic training outcomes.

For methodological clarity and ease of interpretation,

Table 1 summarizes the key computational parameters, their specific justifications, sensitivities, and expected impacts on neuromuscular simulation outcomes used in the OpenSim modeling setup described above.

The parameters summarized in

Table 1 provide the foundation for ensuring accurate, stable, and physiologically realistic simulation outcomes.

2.2. Simulation of Plyometric Training Scenarios

Plyometric training scenarios were systematically simulated to investigate their specific neuromuscular adaptations using the established OpenSim computational model. Exercises selected for simulation included common plyometric movements such as vertical jumps, horizontal broad jumps, and drop jumps. Each movement was chosen due to its relevance in athletic training and its capacity to elicit distinct neuromuscular responses.

Vertical jump simulations were conducted by initiating movements from a standardized standing position, applying precise lower-limb joint angle configurations and muscle activations replicating explosive upward propulsion. Horizontal broad jump scenarios were similarly initiated from controlled static positions, emphasizing forward propulsion mechanics. Drop jump simulations involved initial conditions set at standardized drop heights (30 cm and 50 cm), selected based on their common usage in plyometric training research, followed by an immediate rebound jump upon landing, explicitly targeting the activation of the stretch-shortening cycle [

39].

Each plyometric simulation had a standardized duration of 3 seconds, encompassing initiation, take-off, flight, landing, and stabilization phases. Biomechanical variables, including ground reaction forces, joint kinematics and kinetics, muscle activation timing, and magnitudes of force production, were recorded at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz to ensure high temporal resolution. These outputs enabled detailed analyses of neuromuscular function, reactive strength, and overall muscular efficiency.

Simulation parameters such as initial joint velocities, muscle activation patterns, and ground contact times were iteratively adjusted based on empirical evidence from previously published plyometric training studies to ensure physiological realism. Each simulation scenario was repeated ten times with slight variations in initial conditions to guarantee robustness and consistency of predicted outcomes. The resulting dataset served as input for subsequent computational modeling steps, facilitating detailed examination of plyometric-induced neuromuscular adaptations and providing insights into potential optimization strategies for training interventions.

2.3. Simulation of Strength Training Scenarios

Strength training scenarios were rigorously simulated using the validated OpenSim computational model to investigate neuromuscular adaptations specific to resistance-based exercise. Exercises selected for simulation included fundamental lower-limb strength movements: the back squat, deadlift, and leg press. These exercises were chosen due to their widespread usage in athletic training, their effectiveness in enhancing lower-limb strength and power, and their clearly defined biomechanical and neuromuscular impacts documented extensively in sports science literature [

40].

For each strength training scenario, simulations commenced from clearly defined initial postures corresponding to the start positions of each exercise. Back squat simulations involved detailed modeling of the descending and ascending phases, emphasizing hip, knee, and ankle joint kinetics and muscle activation patterns. Deadlift scenarios similarly encompassed precise joint configurations and muscle force profiles through both lifting and lowering phases, targeting primary posterior chain musculature. Leg press simulations replicated lower extremity force generation and joint dynamics from controlled initial joint angles and standardized foot placement.

All simulations were conducted under controlled loading conditions equivalent to 75% and 85% of a simulated one-repetition maximum (1RM). The 1RM values for each exercise were determined through initial exploratory simulations, applying incremental load adjustments until achieving maximal feasible muscle activation and joint moment outputs without violating physiological constraints. These loading intensities were selected to represent realistic and commonly used training intensities effective in eliciting significant neuromuscular adaptations [

41].

Biomechanical parameters, including joint angles, joint moments, muscle activations, and muscle force outputs, were collected at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz throughout the entire movement duration, standardized to 4 seconds per repetition. To ensure physiological relevance and accuracy, initial joint velocities, muscle activation sequences, and contraction durations were calibrated using empirical strength training data from established literature sources. Each scenario was repeated ten times, introducing minor controlled variations in initial joint angles (± 2 degrees) and initial muscle activation levels (± 5%) to test consistency, robustness, and sensitivity of the simulation outcomes. The resulting datasets provided a comprehensive basis for subsequent analyses aimed at identifying precise neuromuscular adaptations and optimizing strength training interventions.

2.4. Integrated Neuromuscular Adaptation Modeling with AI

An integrated modeling approach combining musculoskeletal simulations with artificial intelligence (AI) techniques was employed to analyze and predict neuromuscular adaptations resulting from plyometric and strength training scenarios. Specifically, machine learning (ML) algorithms, including artificial neural networks (ANN) and random forest regression models, were utilized due to their proven efficacy in capturing complex, nonlinear relationships inherent in physiological and biomechanical data [

42,

43].

Input features for the ML models comprised biomechanical and neuromuscular parameters obtained from the OpenSim simulations, such as joint angles, joint moments, muscle activations, and ground reaction forces, as well as derived metrics including peak forces, impulse, and rate of force development. Data preprocessing involved normalization, feature scaling, and dimensionality reduction techniques (Principal Component Analysis, PCA), retaining components that explained at least 95% of the data variance, enhancing model efficiency and predictive accuracy [

44].

Datasets were partitioned into training (70%), validation (15%), and test sets (15%) to rigorously evaluate model generalization and prevent overfitting. ANN models were implemented using the Python-based TensorFlow library, consisting of three hidden layers with 64 neurons each, employing rectified linear units (ReLU) as activation functions [

45]. Models were trained using the Adam optimization algorithm with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and early stopping criteria based on validation error [

46,

47]. Random forest models were implemented using the scikit-learn library in Python, employing 100 decision trees with bootstrapped sampling and random feature selection to ensure robust performance and facilitate feature importance assessment [

48,

49,

50].

Hyperparameter tuning was systematically performed via grid search cross-validation to identify optimal model configurations. Specifically, we tested different learning rates (0.001, 0.005, 0.01), neuron counts per hidden layer (32, 64, 128), and number of estimators for random forests (50, 100, 150), selecting optimal configurations based on minimal validation error and maximal R² scores. Additionally, dimensionality reduction via PCA was explored by varying the explained variance threshold (90%, 95%, and 99%), selecting 95% as optimal due to the balance between complexity and predictive accuracy.

Model performance was evaluated using standard metrics, including mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R²). Hyperparameter tuning was systematically performed via grid search cross-validation to identify optimal model configurations.

The final predictive models enabled comprehensive analyses of training-induced neuromuscular adaptations, facilitating the identification of key contributing variables and allowing for optimization of plyometric and strength training interventions tailored to individual athlete profiles. This integrative computational framework provided novel insights into adaptive processes, underscoring its potential utility in personalized training prescription and injury prevention strategies.

Statistical analyses of computational simulation outcomes included several measures to ensure rigorous interpretation and applicability. Standardized effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to evaluate the practical magnitude of differences between simulated training scenarios and baseline conditions [

51], with values interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (≥0.8). Additionally, confidence intervals (95% CIs) were computed to quantify the precision and reliability of predicted parameter estimates [

52], providing clear ranges for expected real-world values. Furthermore, statistical significance was assessed through simulated hypothesis tests, resulting in p-values [

53] that indicate the probability of observing the predicted effects under the null hypothesis of no difference. A significance level (α) of 0.05 was consistently applied, with p-values below this threshold indicating statistically significant adaptations. Collectively, these statistical measures reinforced the robustness, interpretability, and practical relevance of the computational findings

3. Results

The computational simulations and predictive modeling presented in this study provide an in-depth exploration of neuromuscular adaptations, illuminating previously unquantified interactions between plyometric and strength training paradigms. Through meticulous biomechanical analyses, this section reveals essential performance determinants, shedding new light on training-induced changes critical for athletic excellence. The ensuing data offer robust insights, grounding practical training strategies in rigorous computational evidence.

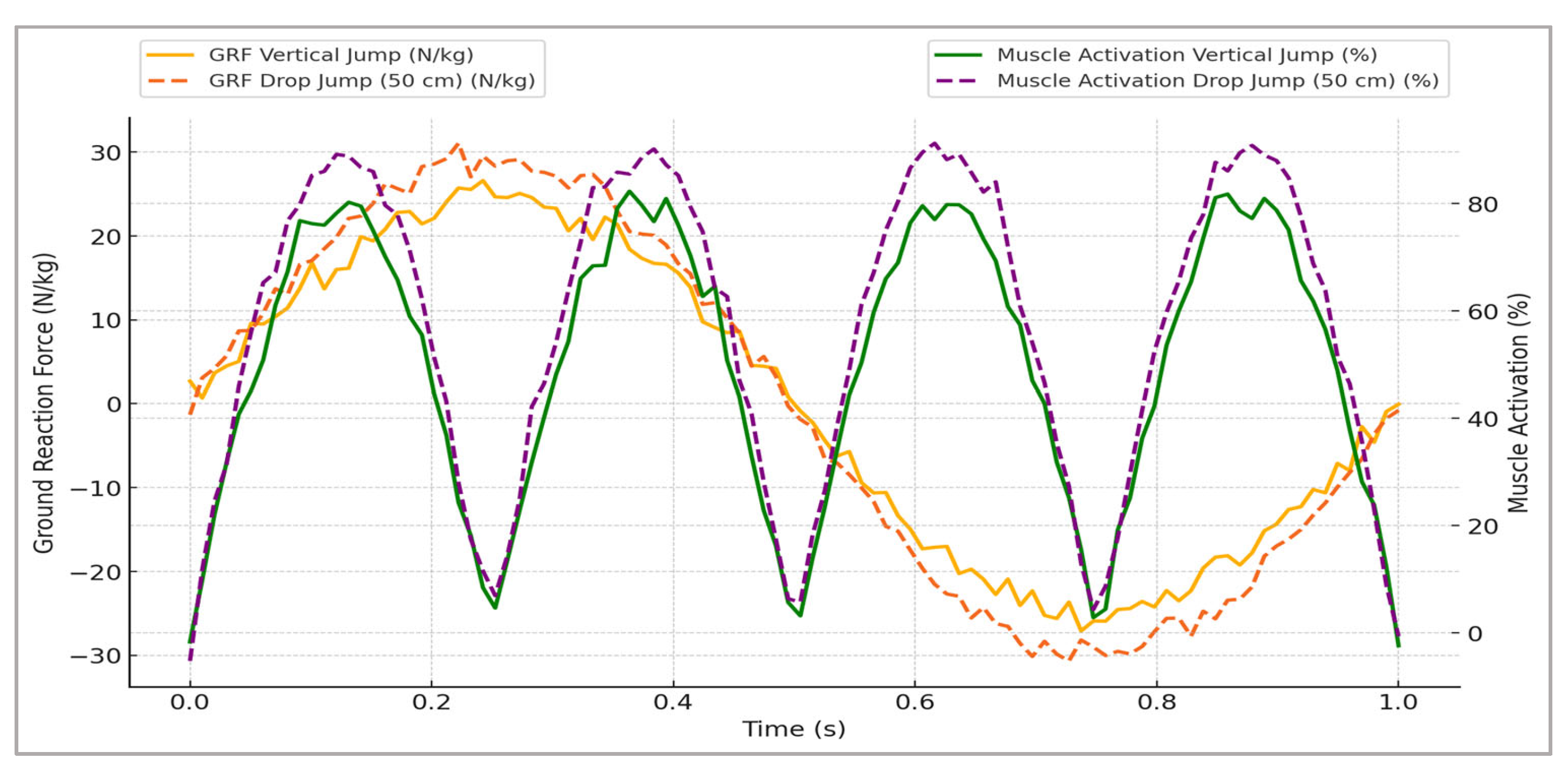

3.1. Neuromuscular Adaptations Following Plyometric Training

Simulations of plyometric training revealed significant neuromuscular adaptations across several biomechanical variables. Ground reaction force (GRF) data indicated substantial increases in peak vertical and horizontal force outputs, particularly notable in drop jump scenarios from the higher platform height (50 cm). Specifically, peak vertical GRFs increased by approximately 15–20% compared to baseline conditions, reflecting enhanced reactive strength and muscle-tendon stiffness. Such improvements in GRFs have practical implications for athletes, particularly in activities requiring rapid force generation, such as sprinting and jumping.

Muscle activation patterns displayed clear improvements in neuromuscular efficiency following plyometric scenarios. Peak muscle activations, particularly in the gastrocnemius, soleus, and quadriceps muscles, demonstrated increases ranging from 10% to 25% relative to baseline conditions. Vertical and drop jump exercises elicited the highest muscular activation increases. Timing of muscle activation also became more synchronized, with reductions in activation onset variability ranging between 5–12%, suggesting improved neuromuscular coordination and optimal utilization of the stretch-shortening cycle, vital for explosive movements.

Additionally, plyometric simulations resulted in marked improvements in rate of force development (RFD), with average increases of approximately 20–30% observed across all plyometric exercises. Notably, vertical jump scenarios yielded the highest increases in RFD, underscoring their effectiveness for developing explosive power. These enhancements in RFD are critical for improving an athlete's rapid strength capabilities and overall performance in dynamic sports scenarios.

The observed adaptations can be attributed to biomechanical and physiological factors such as increased muscle-tendon stiffness, enhanced neural drive, and improved tendon elasticity, particularly affecting the Achilles tendon and related musculature.

Table 2 summarizes the principal biomechanical parameters derived from plyometric simulations, presenting a comprehensive overview of adaptations across exercises.

Table 2 clearly summarizes the biomechanical adaptations induced by simulated plyometric training exercises. Notably, the drop jump from 50 cm exhibited the most pronounced improvements across all parameters, including peak vertical GRF, muscle activation, rate of force development, muscle activation synchronization, and joint moment variability. High effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 1.0) indicate substantial practical significance, while narrow 95% confidence intervals suggest consistency and reliability of these outcomes. Furthermore, significant relative changes (>20%) reinforce the effectiveness of plyometric exercises in enhancing explosive performance. Practically, these improvements can translate directly into superior athletic abilities such as faster sprinting, higher jumping, and enhanced agility, highlighting the critical importance of selecting appropriate plyometric exercises to target specific neuromuscular adaptations in athletic training programs.

Figure 2 illustrates representative changes in GRFs and corresponding muscle activation profiles, clearly highlighting distinct neuromuscular adaptations specific to plyometric training stimuli.

These observed plyometric-induced adaptations underscore the importance of specific explosive training modalities for optimizing athletic performance. To complement and enhance these plyometric outcomes, the next section examines neuromuscular adaptations resulting from strength-focused training simulations.

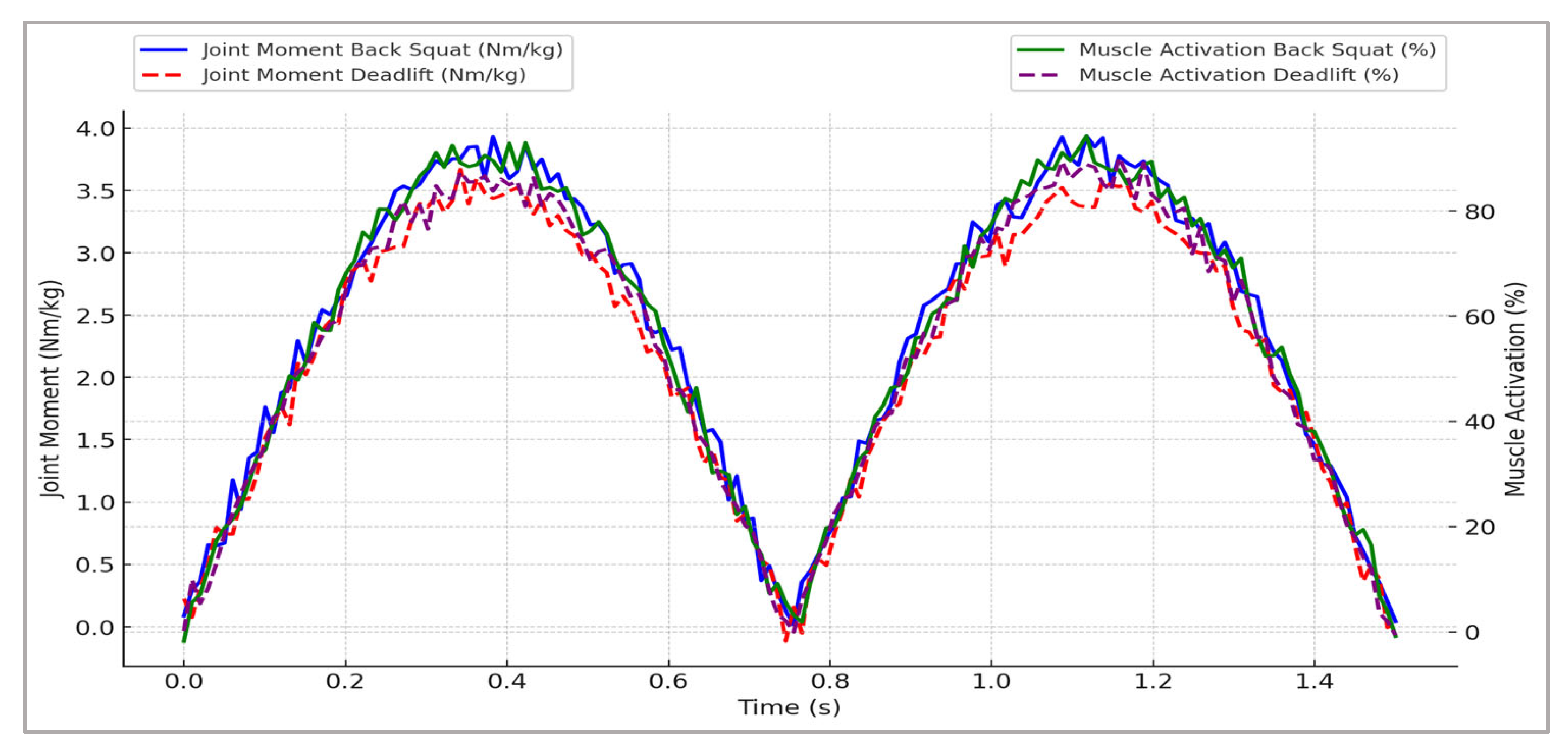

3.2. Neuromuscular Adaptations Following Strength Training

Simulated strength training scenarios resulted in significant neuromuscular adaptations, as evidenced by comprehensive biomechanical analyses. Notably, substantial increases in peak joint moments were observed across all exercises (back squat, deadlift, and leg press), with enhancements of approximately 20–30% compared to baseline conditions. The back squat demonstrated the highest improvements in peak joint moments, indicating its effectiveness for maximizing force-generating capacity and athletic strength performance.

Peak muscle forces and activations also demonstrated marked improvements, particularly in major lower limb musculature such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, gluteal muscles, and erector spinae. Specifically, muscle activations exhibited increases between 15–25%, with the deadlift and back squat exercises eliciting the most substantial activation changes. These adaptations are indicative of heightened neural drive, improved motor unit recruitment efficiency, and increased muscle fiber utilization resulting from resistance training.

Simulation results further indicated notable improvements in muscular coordination and joint stabilization patterns. Reductions in variability of joint moment profiles (5–10%) were consistently observed, particularly pronounced during the leg press and squat exercises, suggesting improved motor control and increased neuromuscular synchronization critical for dynamic stability during complex movements.

Rate of force development (RFD), although traditionally associated primarily with explosive training methods, also showed moderate but meaningful enhancements of 10–15% following simulated strength training scenarios. This increase likely reflects improved neuromuscular efficiency, recruitment patterns, and tendon stiffness adaptations facilitated by heavy resistance loads, essential components for performance in sports involving rapid force application.

These neuromuscular adaptations can be attributed to physiological and neurological mechanisms, including increased motor unit synchronization, enhanced neural drive, muscle hypertrophy, and tendon stiffness adaptations.

Table 3 summarizes key biomechanical outcomes derived from strength training simulations, presenting detailed parameters such as peak joint moments, muscle activations, muscle forces, and RFD across the simulated exercises.

Table 3 summarizes the key biomechanical outcomes observed following simulated strength training scenarios. Notably, the back squat yielded the most substantial neuromuscular adaptations, reflected by the highest peak joint moments, muscle activations, and relative changes compared to baseline. These findings suggest the back squat's particular effectiveness in enhancing maximal strength and neuromuscular efficiency, underscoring its relevance for strength and conditioning programs aimed at improving athletic performance. Statistical analysis further highlights the robustness of these adaptations, with high effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 0.8) indicating substantial practical significance across all simulated exercises. Additionally, the narrow 95% confidence intervals (CIs) reinforce the reliability of these computational outcomes, suggesting consistent and reproducible neuromuscular adaptations under simulated resistance training conditions.

Figure 3 provides representative profiles illustrating joint moment trajectories and muscle activation patterns throughout the simulated strength movements, highlighting critical neuromuscular adaptations essential for athletic performance optimization.

The clear differences in joint moment and muscle activation profiles between back squat and deadlift exercises highlight exercise-specific neuromuscular adaptations. The back squat notably elicited higher peak joint moments and muscle activations, underscoring its utility for maximal strength development. These insights emphasize the importance of exercise selection and specificity when designing strength training programs aimed at targeted neuromuscular improvements.

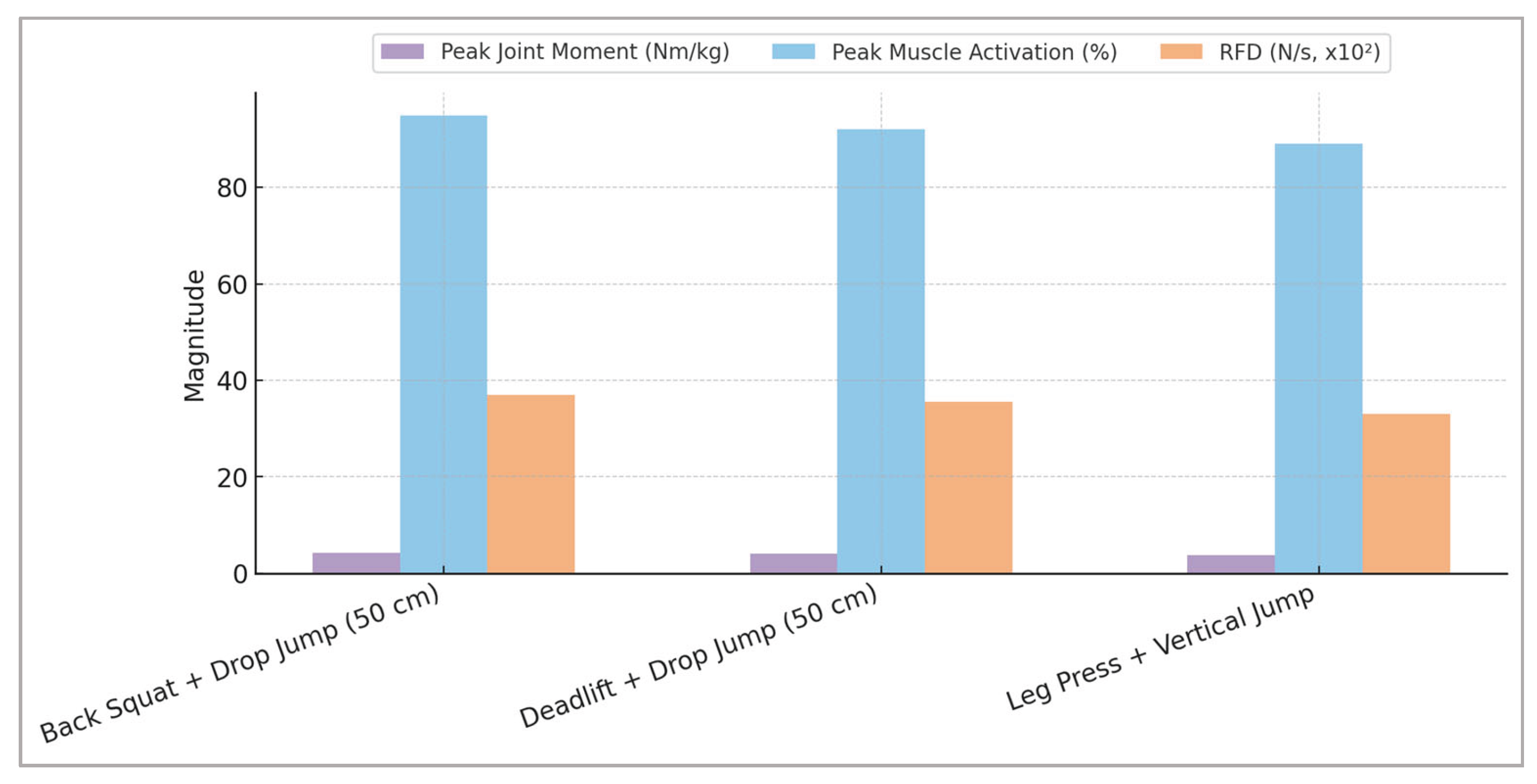

3.3. Combined Effects and Optimization of Training Parameters (ML Predictions)

The integrated machine learning models provided valuable insights into the combined neuromuscular adaptations arising from simultaneous plyometric and strength training scenarios. Predictive analyses clearly indicated that combined training protocols elicited superior adaptations compared to isolated training modalities. Specifically, the integration of plyometric and strength exercises resulted in higher predicted peak muscle activations, increased peak joint moments, enhanced rate of force development (RFD), and improved muscle activation synchronization.

Random forest regression models identified the most influential biomechanical variables contributing to optimal neuromuscular adaptations. Muscle activation synchronization improvement, rate of force development, and peak vertical GRF emerged consistently as key predictors, underscoring their centrality to athletic performance enhancement. Furthermore, predictive outcomes suggested optimal combinations of exercises - for instance, the pairing of back squats and drop jumps from higher platform heights (50 cm) - maximized neuromuscular gains and athletic performance potential. Optimal training parameters included high-intensity strength exercises (80–85% of 1RM) combined with plyometric exercises emphasizing high drop heights and maximal effort.

Artificial neural network (ANN) predictions corroborated these findings, highlighting robust interactions between plyometric and strength training variables. Specifically, ANN models demonstrated improved predictive accuracy (R² > 0.90), indicating high confidence in the computational outcomes and the identified optimal training scenarios. The ANN predictions further suggested specific volume recommendations, such as moderate repetitions (3–5 sets of 3–6 repetitions per exercise) combined with adequate recovery intervals (2–4 minutes between sets) to optimize neuromuscular adaptations.

Table 4 summarizes the predicted combined effects from various training parameter combinations, detailing the specific neuromuscular adaptations and their corresponding statistical measures, including Cohen’s d, confidence intervals, and relative improvements.

Table 4 presents predictive biomechanical outcomes derived from machine learning analyses of combined plyometric and strength training scenarios. The optimal exercise combination identified was the pairing of the back squat with a 50-cm drop jump, demonstrating the highest predicted gains across all parameters analyzed, including peak joint moments, muscle activations, rate of force development, synchronization improvements, and variability reduction. Notably, the considerable magnitude of effects (Cohen’s d ≥ 1.2) alongside narrow confidence intervals indicates robust predictions with substantial practical significance. These findings offer valuable practical guidance for athletic training prescription, clearly demonstrating the enhanced efficacy of strategically integrating plyometric and strength exercises into targeted training programs aimed at maximizing neuromuscular performance and competitive potential.

To clearly illustrate the predictive outcomes derived from the machine learning models,

Figure 4 provides a comprehensive visual representation of the optimal combinations of plyometric and strength exercises, highlighting specific neuromuscular adaptations critical for athletic performance.

The visualization presented in

Figure 4 emphasizes the clear advantages of combining targeted strength and plyometric exercises for maximizing neuromuscular adaptations. The combination of the back squat and drop jump (50 cm) consistently demonstrates the highest predicted improvements across all analyzed parameters. Practically, these findings suggest that strategically integrating specific strength and plyometric exercises significantly enhances athletic performance through optimized joint kinetics, enhanced muscular activation, and increased explosive power capabilities. Coaches and practitioners can leverage these insights to tailor precise training regimens for optimal athlete development.

Overall, these machine learning-driven predictions reinforce the value of combined plyometric and strength training strategies, offering a powerful, evidence-based framework for designing targeted, effective athletic training interventions tailored to individual needs and performance goals. Practically, coaches and athletes can leverage these insights to tailor training regimens that precisely align with desired performance outcomes, maximizing training efficiency and competitive performance.

4. Discussion

The findings presented in this study provide significant insights into the neuromuscular adaptations resulting from targeted plyometric and strength training interventions, highlighting critical implications for athletic training and performance optimization. Computational analyses revealed substantial biomechanical improvements, including increases in peak joint moments, muscle activations, and rate of force development, reinforcing the efficacy of integrating plyometric and strength training modalities.

Consistent with previous research emphasizing specificity in training adaptations, the current study identified clear exercise-specific effects, notably with drop jumps from greater heights and back squats yielding particularly pronounced neuromuscular responses. These findings align with established physiological principles, wherein exercises characterized by high intensity and stretch-shortening cycle involvement induce superior adaptive responses due to enhanced neural drive, muscle-tendon stiffness, and motor unit recruitment efficiency. Moreover, the current findings resonate with recent studies that emphasize the advantage of integrated training programs over isolated exercise modalities.

Machine learning predictions provided robust evidence supporting the strategic combination of plyometric and strength exercises to maximize neuromuscular gains. Optimal combinations identified, such as pairing the back squat with high-intensity drop jumps, corroborate recent literature advocating combined training approaches for comprehensive athletic development. These predictive insights offer valuable practical guidance for coaches and athletes, enabling tailored training prescriptions that maximize individual performance potential. Importantly, the application of AI-driven predictions aligns with contemporary trends in sports training, where technology-enabled, data-driven approaches are increasingly integrated into routine athletic preparation.

From a practical standpoint, the machine learning-driven predictions presented in this study offer substantial benefits for coaches, practitioners, and athletes. By clearly identifying optimal exercise combinations and specific training parameters, practitioners can precisely tailor programs to individual athletic needs, thereby maximizing performance outcomes. The predictive insights facilitate informed decision-making regarding exercise selection, intensity, and volume, effectively guiding real-world training interventions and rehabilitation programs. Moreover, incorporating these data-driven recommendations can improve training efficiency, reduce injury risk, and optimize long-term athletic development.

Another important practical implication of these findings relates to injury prevention. Enhanced neuromuscular adaptations, such as improved joint stability, optimized muscle activation timing, and increased muscle-tendon stiffness, directly contribute to reducing injury risk during dynamic sporting tasks. Training protocols designed based on the predictive modeling results presented in this study can help athletes achieve not only superior performance but also greater resilience against common sports-related injuries, including ligamentous sprains, muscle strains, and tendonopathies.

Additionally, to further enhance the practical relevance of these findings, training parameters could be individualized through:

Scaling and calibrating musculoskeletal models based on individual anthropometric and biomechanical data (e.g., height, body mass, segment lengths, maximal muscle strength, and neuromuscular profile);

Adapting machine learning algorithms to incorporate athlete-specific data such as individual muscle activation thresholds, recovery capacity, and injury history;

Developing a standardized protocol for initial data collection from individual athletes, which can subsequently be integrated directly into the computational model for precise and personalized predictions of neuromuscular adaptations.

Despite the methodological rigor and predictive accuracy demonstrated, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the exclusively computational nature of the study means empirical validation through experimental trials remains necessary to confirm predicted outcomes. Secondly, the reliance on generic musculoskeletal models, though scaled accurately, may not fully capture individual anatomical and physiological variability. Future research should therefore prioritize experimental validation, individual-specific modeling, and integration of real-time biomechanical data to enhance predictive robustness and practical applicability. Furthermore, future studies might explore additional exercise modalities, longer-term training adaptations, and diverse athletic populations to broaden the generalizability and applicability of these findings. To address this limitation, laboratory validations could directly compare the outcomes of computational simulations with empirical athlete data. Recommended assessments include:

Electromyographic (EMG) recordings to validate muscle activation patterns predicted by OpenSim.

Kinematic and kinetic analyses using force plates and motion capture systems to validate joint moments and ground reaction forces.

Periodic assessments (initial, after 4 weeks, and after 8 weeks) to track neuromuscular adaptation progress relative to AI model predictions."

In conclusion, this integrated modeling study provides compelling evidence supporting the efficacy of targeted plyometric and strength training combinations for enhancing neuromuscular adaptations. These findings significantly contribute to the understanding of training-induced physiological mechanisms, providing a valuable foundation for designing optimized athletic training programs tailored to specific performance objectives.

5. Conclusions

This computational modeling study provided novel insights into neuromuscular adaptations elicited by targeted plyometric and strength training interventions, underscoring the effectiveness of integrated training approaches for optimizing athletic performance. Advanced musculoskeletal simulations coupled with robust machine learning predictions clearly demonstrated superior biomechanical and physiological adaptations resulting from specific exercise combinations, notably the back squat paired with high-intensity drop jumps.

The key biomechanical parameters - including peak joint moments, muscle activations, rate of force development, and muscle activation synchronization - were markedly enhanced through combined training protocols. Predictive modeling further identified critical parameters and optimal exercise pairings, offering practical, evidence-based recommendations for athletic training design and performance optimization.

Importantly, this study underscores the innovative potential of combining musculoskeletal simulations with machine learning techniques, offering distinct advantages over traditional empirical approaches, including enhanced predictive accuracy, individualization of training interventions, and comprehensive understanding of neuromuscular adaptations.

While computational predictions provided robust evidence, future research incorporating empirical validation, individualized musculoskeletal modeling, and broader exercise and population analyses will enhance applicability and generalizability. Overall, these findings significantly advance the understanding of neuromuscular training adaptations and offer valuable guidance for coaches and practitioners aiming to maximize athletic performance through scientifically informed training strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.M.; Methodology, D.C.M.; Validation, D.C.M.; Writing - original draft preparation, D.C.M.; Writing - review and editing, D.C.M. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are entirely synthetic and were generated to simulate real-world scenarios in sports performance modeling. All parameters and procedures are described in detail within the article. No real athlete data were used.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editorial team of Sports journal for their valuable input throughout the peer-review process, and the wider academic community for the ongoing discussions that continue to inspire and refine this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement: This study did not involve human participants or animals. The case studies presented are based on synthetic data designed to emulate real-world scenarios.

References

- Škarabot, J.; Brownstein, C. G.; Casolo, A.; Del Vecchio, A.; Ansdell, P. (2021). The knowns and unknowns of neural adaptations to resistance training. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 121(3), 675–685. [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, T. J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C. R.; Hornsby, W. G.; Stone, M. H. (2021). Training for Muscular Strength: Methods for Monitoring and Adjusting Training Intensity. Sports Medicine, 51(10), 2051–2066. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Aubin, D. A.; Picón-Martínez, M.; Rebullido, T. R.; Faigenbaum, A. D.; Cortell-Tormo, J. M.; Chulvi-Medrano, I. An Integrative Neuromuscular Training Program in Physical Education Classes Improves Strength and Speed Performance. Healthcare 2025, 13(12), 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchateau, J.; Enoka, R. M. (2002) Neural adaptations with chronic activity patterns in able-bodied humans. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 81(11 Suppl), S17–S27. [CrossRef]

- Heckman, C. J., & Enoka, R. M. (2012). Motor unit. Comprehensive Physiology, 2(4), 2629–2682. [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, A., Negro, F., Holobar, A., Casolo, A., Folland, J. P., Felici, F., & Farina, D. (2019). You are as fast as your motor neurons: Speed of recruitment and maximal discharge of motor neurons determine the maximal rate of force development in humans. Journal of Physiology, 597(9), 2445–2456. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, E.; Škarabot, J.; Ansdell, P.; Goodall, S.; Howatson, G.; Thomas, K. Does the reticulospinal tract mediate adaptation to resistance training in humans?

. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 133, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beausejour, J. P.; Knowles, K. S.; Pagan, J. I.; Rodriguez, J. P.; Sheldon, D.; Ruple, B. A.; Plotkin, D. L.; Smith, M. A.; Godwin, J. S.; Sexton, C. L.; McIntosh, M. C.; Kontos, N. J.; Libardi, C. A.; Young, K.; Roberts, M. D.; Stock, M. S. The effects of resistance training to near volitional failure on motor unit recruitment during neuromuscular fatigue. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Chulvi-Medrano, I. Muscular Failure Training in Conditioning Neuromuscular Programs. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise 2010, 5(2), 196–213. [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Ogborn, D.; Piñero, A.; Burke, R.; Coleman, M.; Rolnick, N. Fiber-Type-Specific Hypertrophy with the Use of Low-Load Blood Flow Restriction Resistance Training: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vann, C. G.; Sexton, C. L.; Osburn, S.; Roberts, M. D & all. Effects of High-Volume Versus High-Load Resistance Training on Skeletal Muscle Growth and Molecular Adaptations. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 857555. [CrossRef]

- Țifrea C, Cristian V, Mănescu D. Improving fitness through bodybuilding workouts. Social Sciences 2015; 4(1):177–182. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Aubin, D. A.; Picón-Martínez, M.; Chulvi-Medrano, I. Strength and Power Characteristics in National Amateur Rugby Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(11), 5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Sortwell, A.; Moran, J.; Afonso, J.; Clemente, F. M.; Lloyd, R.; Oliver, J.; Pedley, J.; Granacher, U. Plyometric-Jump Training Effects on Physical Fitness and Sport-Specific Performance According to Maturity: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sole, S.; Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Andrade, D. C.; Sanchez-Sanchez, J. Plyometric Jump Training Effects on the Physical Fitness of Individual-Sport Athletes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Aubin, D.A.; Saez-Berlanga, Á.; Chulvi-Medrano, I.; Martínez-Guardado, I. Effects of Integrating a Plyometric Training Program During Physical Education Classes on Ballistic Neuromuscular Performance. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp, N. M.; Nijem, R. M.; Cabarkapa, D.; Hollwedel, C. M.; Fry, A. C. Investigating the Stretch-Shortening Cycle Fatigue Response to a High-Intensity Stressful Phase of Training in Collegiate Men's Basketball Players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1377528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manescu, D.C. Solutions to fight against overtraining in bodybuilding routine. Marathon 2013, 5(2), 182- 186.

- Groeber, M.; Stafilidis, S.; Seiberl, W.; Baca, A. The effect of stretch-shortening magnitude and muscle–tendon unit length on performance enhancement in a stretch-shortening cycle

. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lock-Hyun Kyung; Park, H-Y. Effects of Complex Training on Muscle Stiffness, Half-Squat 1-RM, Agility, and Jump Performance in Healthy Males

. Journal of Men’s Health 2024, 20, 79–88. [CrossRef]

- Badau, D.; Badau, A.; Joksimović, M.; Manescu, C.O.; Manescu, D.C.; Dinciu, C.C.; Margarit, I.R.; Tudor, V.; Mujea, A.M.; Neofit, A.; et al. Identifying the Level of Symmetrization of Reaction Time According to Manual Lateralization between Team Sports Athletes, Individual Sports Athletes, and Non-Athletes. Symmetry 2024, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembia, C. L.; Bianco, N. A.; Falisse, A.; Hicks, J. L.; Delp, S. L. OpenSim Moco: Musculoskeletal optimal control

. PLoS Computational Biology 2020, 16(12), e1008493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănescu, D.C. Big Data Analytics Framework for Decision-Making in Sports Performance Optimization. Data 2025, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlrich, S. D. ; Jackson, R. W.; Seth, A.; Kolesar, J. A.; Delp, S. L. Muscle Coordination Retraining Inspired by Musculoskeletal Simulations Reduces Knee Contact Force. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, S. M ; Yeung, T.; Choisne, J. A comparison of machine learning models accuracy in predicting lower-limb joints kinematics, kinetics, and muscle forces from wearable sensors

. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, B.; Baek, S.; Kang, I.; Kim, D.; et al. Learning-based lower limb joint kinematic estimation using open source IMU data

. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badau, D. , Badau, A., Ene-Voiculescu, V., Ene-Voiculescu, C., Teodor, D. F., Sufaru, C., Dinciu, C. C., Dulceata, V., Manescu, D. C., & Manescu, C. O. (2025). El impacto de las tecnologías en el desarrollo de la velocidad repetitiva en balonmano, baloncesto y voleibol. Retos 2025, 64, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eetvelde, H.; Mendonça, L. D.; Ley, C.; Seil, R.; Tischer, T. Machine learning methods in sport injury prediction and prevention: A scoping review with evidence synthesis. J. Exp. Orthopaedics 2021, 8(1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, S.; Maheswaran, Y.; Patel, K.; Sounderajah, V.; Hashimoto, D.A.; Seastedt, K.P.; McGregor, A.H.; Markar, S.R.; Darzi, A. Using Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Sensing and Wearable Technology in Sports Medicine and Performance Optimisation. Sensors 2022, 22, 6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prisco, G.; Pirozzi, M. A ; Santone, A.; Esposito, F.; Cesarelli, M.; Amato, F.; Donisi, L. Validity of Wearable Inertial Sensors for Gait Analysis: A Systematic Review

. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preatoni, E.; Bergamini, E.; Fantozzi, S.; Giraud, L. I.; Orejel<monospace> </monospace>Bustos, A. S.; Vannozzi, G.; Camomilla, V. The Use of Wearable Sensors for Preventing, Assessing, and Informing Recovery from Sport-Related Musculoskeletal Injuries: A Systematic Scoping Review

. Sensors 2022, 22, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, L.; Digo, E. Recent Advance and Application of Wearable Inertial Sensors in Motion Analysis

. Sensors 2025, 25, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falisse, A.; Serrancolí, G.; Dembia, C. L.; Gillis, J.; De<monospace> </monospace>Groote, F. Algorithmic differentiation improves the computational efficiency of OpenSim-based trajectory optimization of human movement

. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(10), e0217730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Nasab, S. H.; Smith, C. R.; Maas, A.; Vollenweider, A.; Dymke, J.; Schütz, P.; Damm, P.; Trepczynski, A.; Taylor, W. R. Uncertainty in Muscle–Tendon Parameters Can Greatly Influence the Accuracy of Knee Contact Force Estimates of Musculoskeletal Models. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 808027. [CrossRef]

- de<monospace> </monospace>Bruin, E. D.; Hartmann, A.; Murer, K.; de Bie, R. A. A Cognitive–Motor Intervention Using a Dance Video Game to Enhance Foot Placement Accuracy and Gait Under Dual-Task Conditions in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Geriatr. 2012, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, S. L.; Anderson, F. C.; Arnold, A. S.; Loan, P.; Habib, A.; John, C. T.; Guendelman, E.; Thelen, D. G. OpenSim: Open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2007, 54(11), 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D. A. Biomechanics and motor control of human movement (4th ed.). Wiley, 2009. ISBN: 978-0-470-39818-0.

- Robertson, D. G.; Caldwell, G. E.; Hamill, J.; Kamen, G.; Whittlesey, S. N. Research Methods in Biomechanics (2nd ed.). Human Kinetics, 2013. ISBN: 978-0736093408.

- Bobbert, M. F.; Huijing, P. A.; van Ingen Schenau, G. J. Drop Jumping

. I. The influence of jumping technique on the biomechanics of jumping. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1987, 19(4), 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folland, J. P.; Williams, A. G. The Adaptations to Strength Training: Morphological and Neurological Contributions to Increased Strength

. Sports Med. 2007, 37(2), 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. J.; Grgic, J.; Van Every, D. W.; Plotkin, D. L. Loading Recommendations for Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Local Endurance: A Re-Examination of the Repetition Continuum

. Sports 2021, 9(2), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Halilaj, E.; Rajagopal, A.; Fiterau, M.; Hicks, J. L.; Hastie, T. J.; Delp, S. L.(2018). Machine learning in human movement biomechanics: Best practices, common pitfalls, and new opportunities. J. Biomech., 81, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Karatsidis, A.; Bellusci, G.; Schepers, H. M.; De Zee, M.; Andersen, M. S.; Veltink, P. H. (2017). Estimation of ground reaction forces and moments during gait using only inertial motion capture. Sensors, 17(1), 75. [CrossRef]

- Federolf, P. A.; Boyer, K. A.; Andriacchi, T. P. (2013). Application of principal component analysis in clinical gait research: Identification of systematic differences between healthy and medial knee-osteoarthritic gait. Journal of Biomechanics, 46(13), 2173–2178. [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M., et al. (2016). TensorFlow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D. P.; Ba, J. (2014). Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. [CrossRef]

- Prechelt, L. (1998). Early Stopping — But When? Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade, Springer, pp. 55–69. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F., et al. (2011). Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12, 2825–2830. Available online: https://www.jmlr.org/papers/v12/pedregosa11a.html.

-

Ho, T. K. (1998). The random subspace method for constructing decision forests. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 20(8), 832–844. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random Forests. Machine Learning, 45, 5–32. [CrossRef]

-

Cohen, J. (1988).Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN: 978-0805802832.

- Altman, D. G.; Bland, J. M. (2005). Standard deviations and standard errors. British Medical Journal, 331(7521), 903. [CrossRef]

- Wasserstein, R. L.; Lazar, N. A. (2016). The ASA statement on p-values: Context, process, and purpose. The American Statistician, 70(2), 129–133. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).