Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

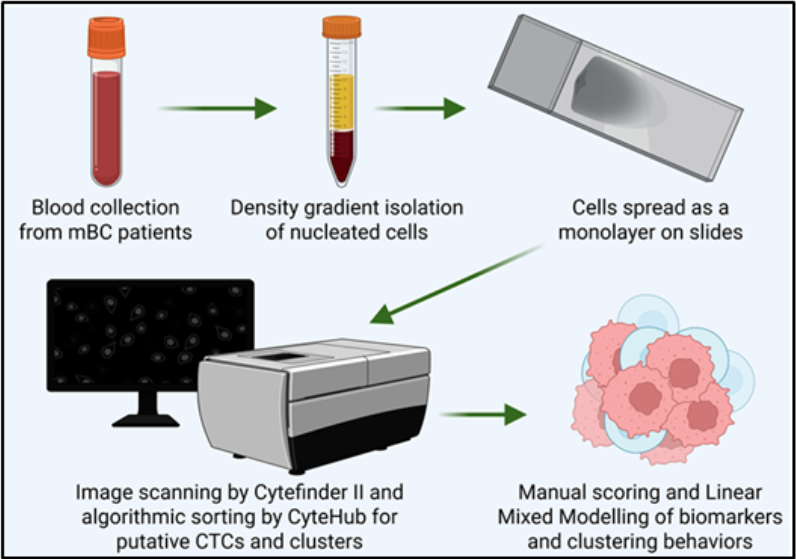

2.2. RareCyte® Sample Processing, Scanning, and Analysis

2.3. Confocal Imaging

2.4. Endpoints and Assessments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Data Availability

3. Results

3.1. RareCyte Reveals Expression of Trop2 in Breast Cancer Patient CTCs and High Inter-Marker Correlation

3.2. No Individual CTC Biomarker Condition Was Significantly Associated with Receptor Status

3.3. Longitudinal Analysis Reveals Differences in Clustering Behavior Between HR+ and HER2+ Cancers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTC | Circulating Tumor Cell |

| cCTC | Classically defined Circulating Tumor Cell |

| T2CTC | Trop2-expressing Circulating Tumor Cell |

| mBC | Metastatic Breast Cancer |

| TCCP | Total Cancer Care Protocol |

| CK | Cytokeratin |

| EpCAM | Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

References

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Siesling, S.; et al. Current and Future Burden of Breast Cancer: Global Statistics for 2020 and 2040. The Breast 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heer, E.; Harper, A.; Escandor, N.; Sung, H.; McCormack, V.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global Burden and Trends in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Study. The Lancet Global Health 2020, 8, e1027–e1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.T.; Li, Z.Y.; Ma, C.X.; Zhou, S.Q.; Chen, D.D. Opportunities and Challenges in the Development of Antibody-Drug Conjugate for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: The Diverse Choices and Changing Needs. World J Oncol 2024, 15, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrigos, L.; Camacho, D.; Perez-Garcia, J.M.; Llombart-Cussac, A.; Cortes, J.; Antonarelli, G. Sacituzumab Govitecan for Hormone Receptor-Positive HER2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2024, 24, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.K.; Tellez-Gabriel, M.; Cartron, P.-F.; Vallette, F.M.; Heymann, M.-F.; Heymann, D. Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells as a Reflection of the Tumor Heterogeneity: Myth or Reality? Drug Discov Today 2019, 24, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, N.; Bardia, A.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Donaldson, M.C.; Wittner, B.S.; Spencer, J.A.; Yu, M.; Pely, A.; Engstrom, A.; Zhu, H.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Clusters Are Oligoclonal Precursors of Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cell 2014, 158, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauken, C.M.; Kenney, S.R.; Brayer, K.J.; Guo, Y.; Brown-Glaberman, U.A.; Marchetti, D. Heterogeneity of Circulating Tumor Cell Neoplastic Subpopulations Outlined by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffer, C.L.; Weinberg, R.A. A Perspective on Cancer Cell Metastasis. Science 2011, 331, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeVasseur, N.; Manna, M.; Jerzak, K.J. An Overview of Long-Acting GnRH Agonists in Premenopausal Breast Cancer Patients: Survivorship Challenges and Management. Curr Oncol 2024, 31, 4209–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliassen, F.M.; Blåfjelldal, V.; Helland, T.; Hjorth, C.F.; Hølland, K.; Lode, L.; Bertelsen, B.-E.; Janssen, E.A.M.; Mellgren, G.; Kvaløy, J.T.; et al. Importance of Endocrine Treatment Adherence and Persistence in Breast Cancer Survivorship: A Systematic Review. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spizzo, G.; Obrist, P.; Ensinger, C.; Theurl, I.; Dünser, M.; Ramoni, A.; Gunsilius, E.; Eibl, G.; Mikuz, G.; Gastl, G. Prognostic Significance of Ep-CAM AND Her-2/Neu Overexpression in Invasive Breast Cancer. Int J Cancer 2002, 98, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, F. Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab with or without a Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor for HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2023, 1878, 188969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.U.; Claus, E.; Sohl, J.; Razzak, A.R.; Arnaout, A.; Winer, E.P. Sites of Distant Recurrence and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer 2008, 113, 2638–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, R.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Hanna, W.M.; Kahn, H.K.; Sawka, C.A.; Lickley, L.A.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Clinical Features and Patterns of Recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 2007, 13, 4429–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofanilli, M.; Budd, G.T.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Reuben, J.M.; Doyle, G.V.; Allard, W.J.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells, Disease Progression, and Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2004, 351, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, U.; Cirulli, V.; Giepmans, B.N.G. EpCAM: Structure and Function in Health and Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2013, 1828, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trzpis, M.; McLaughlin, P.M.J.; de Leij, L.M.F.H.; Harmsen, M.C. Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule: More than a Carcinoma Marker and Adhesion Molecule. The American Journal of Pathology 2007, 171, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Guo, X.; Yang, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Y.; Liang, X.; Su, J.; Jiang, L.; Li, J.; et al. EpCAM-Targeting CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy Is Safe and Efficacious for Epithelial Tumors. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, L.A.; Ebian, H.; Harb, O.; Nosery, Y.; Taha, H.; Nawar, N. Clinical Significance of Cytokeratin 19 and OCT4 as Survival Markers in Non-Metastatic and Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2022, 26, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, E.; Moghbelinejad, S.; Mohammadi, G.; Shahbazmohammadi, H.; Abdolvahabi, Z.; Jalilvand, M.; Zare, I.; Alaei, M.; Keshavarz Shahbaz, S. Cytokeratin Expression in Breast Cancer: From Mechanisms, Progression, Diagnosis, and Prognosis to Therapeutic Implications. Molecular & Cellular Oncology 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, S.; Sharma, P.; Bursch, K.; Milliken, R.; Lam, V.; Fallatah, A.; Phan, T.; Collins, M.; Dohlman, P.; Tiufekchiev, S.; et al. Keratin 19 Maintains E-Cadherin Localization at the Cell Surface and Stabilizes Cell-Cell Adhesion of MCF7 Cells. Cell Adh Migr 2021, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, S.E.; Klebanov-Akopyn, O.; Pavlov, V.; Laks, S.; Hazzan, D.; Nissan, A.; Zippel, D. Detection of Minimal Residual Disease in the Peripheral Blood of Breast Cancer Patients, with a Multi Marker (MGB-1, MGB-2, CK-19 and NY-BR-1) Assay. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2021, 13, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, R.R.; Yang, Q.; Higgins, S.A.; Haffty, B.G. Outcomes in Young Women with Breast Cancer of Triple-Negative Phenotype: The Prognostic Significance of CK19 Expression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008, 70, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsifaki, A.; Maroulaki, S.; Armakolas, A. Exploring the Immunological Profile in Breast Cancer: Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Prognosis through Circulating Tumor Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ridgway, L.D.; Wetzel, M.D.; Ngo, J.; Yin, W.; Kumar, D.; Goodman, J.C.; Groves, M.D.; Marchetti, D. The Identification and Characterization of Breast Cancer CTCs Competent for Brain Metastasis. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5, 180ra48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.R.; Durrans, A.; Lee, S.; Sheng, J.; Li, F.; Wong, S.T.C.; Choi, H.; El Rayes, T.; Ryu, S.; Troeger, J.; et al. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Is Not Required for Lung Metastasis but Contributes to Chemoresistance. Nature 2015, 527, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, S.J.; Thomas, J.S.; Langdon, S.P.; Harrison, D.J.; Faratian, D. Quantitative Analysis of Changes in ER, PR and HER2 Expression in Primary Breast Cancer and Paired Nodal Metastases. Annals of Oncology 2010, 21, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, D.J.E.; Van Dam, P.-J.; Van Den Eynden, G.G.M.; Rutten, A.; Wuyts, H.; Pouillon, L.; Peeters, M.; Pauwels, P.; Van Laere, S.J.; Van Dam, P.A.; et al. Detection and Prognostic Significance of Circulating Tumour Cells in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer According to Immunohistochemical Subtypes. Br J Cancer 2014, 110, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasinghe, A.; Wu, H.; Punyadeera, C.; Warkiani, M.E. The Use of Microfluidic Technology for Cancer Applications and Liquid Biopsy. Micromachines (Basel) 2018, 9, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, M.; Peddibhotla, S.; Yin, W.; T. Scamardo, A.; George, G.C.; Hong, D.S.; Marchetti, D. The Isolation and Characterization of CTC Subsets Related to Breast Cancer Dormancy. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampignano, R.; Schneck, H.; Neumann, M.; Fehm, T.; Neubauer, H. Enrichment, Isolation and Molecular Characterization of EpCAM-Negative Circulating Tumor Cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017, 994, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Königsberg, R.; Obermayr, E.; Bises, G.; Pfeiler, G.; Gneist, M.; Wrba, F.; de Santis, M.; Zeillinger, R.; Hudec, M.; Dittrich, C. Detection of EpCAM Positive and Negative Circulating Tumor Cells in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Acta Oncol 2011, 50, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrichova, I.; Kalinkova, L.; Ciernikova, S. Clinical Relevancy of Circulating Tumor Cells in Breast Cancer: Epithelial or Mesenchymal Characteristics, Single Cells or Clusters? Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Zhang, R.; Ou, Z.; Ye, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, A.; Chen, T.; Chai, C.; Guo, B. TROP2 Is Highly Expressed in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer CTCs and Is a Potential Marker for Epithelial Mesenchymal CTCs. Molecular Therapy: Oncology 2024, 32, 200762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroudis, D.; Lagoudaki, E.; Gounaki, S.; Hatziavraam, S.; Fotsitzoudis, C.; Michaelidou, K.; Agelaki, S.; Papadaki, M.A. Abstract P4-05-27: Comparative Analysis of TROP2 Expression in Tumor Tissues and Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) in the Peripheral Blood of Patients with Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2025, 31, P4–05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-J.; Lu, M.; Feng, X.; Nakato, G.; Udey, M.C. Matriptase Cleaves EpCAM and TROP2 in Keratinocytes, Destabilizing Both Proteins and Associated Claudins. Cells 2020, 9, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-J.; Feng, X.; Lu, M.; Morimura, S.; Udey, M.C. Matriptase-Mediated Cleavage of EpCAM Destabilizes Claudins and Dysregulates Intestinal Epithelial Homeostasis. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenárt, S.; Lenárt, P.; Šmarda, J.; Remšík, J.; Souček, K.; Beneš, P. Trop2: Jack of All Trades, Master of None. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, A.; Lony, N.; Lennartz, M.; Dwertmann Rico, S.; Schlichter, R.; Kind, S.; Reiswich, V.; Viehweger, F.; Dum, D.; Luebke, A.M.; et al. Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (EpCAM) Expression in Human Tumors: A Comparison with Pan-Cytokeratin and TROP2 in 14,832 Tumors. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslemarz, A.; Fagotto-Kaufmann, M.; Ruppel, A.; Fagotto-Kaufmann, C.; Balland, M.; Lasko, P.; Fagotto, F. An EpCAM/Trop2 Mechanostat Differentially Regulates Collective Behaviour of Human Carcinoma Cells. EMBO J 2025, 44, 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szostakowska-Rodzos, M.; Fabisiewicz, A.; Wakula, M.; Tabor, S.; Szafron, L.; Jagiello-Gruszfeld, A.; Grzybowska, E.A. Longitudinal Analysis of Circulating Tumor Cell Numbers Improves Tracking Metastatic Breast Cancer Progression. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, D.G.; Duyverman, A.M.M.J.; Kohno, M.; Snuderl, M.; Steller, E.J.A.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Malignant Cells Facilitate Lung Metastasis by Bringing Their Own Soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 21677–21682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabisiewicz, A.; Grzybowska, E. CTC Clusters in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Med Oncol 2017, 34, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, E.; Taftaf, R.; Reduzzi, C.; Albert, M.K.; Romero-Calvo, I.; Liu, H. Better Together: Circulating Tumor Cell Clustering in Metastatic Cancer. Trends Cancer 2021, 7, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Luo, S.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, L.; Ren, H.; Angele, M.K.; Börner, N.; Yu, K.; et al. Circulating Tumor Microenvironment in Metastasis. Cancer Research 2025, 85, 1354–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, Z.S.; Khattap, M.G.; Madkour, M.A.; Yasen, N.S.; Elbary, H.A.; Elsayed, R.A.; Abdelkawy, D.A.; Wadan, A.-H.S.; Omar, I.; Nafady, M.H. Circulating Tumor Cells Clusters and Their Role in Breast Cancer Metastasis; a Review of Literature. Discov Onc 2024, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Carstens, J.L.; Kim, J.; Scheible, M.; Kaye, J.; Sugimoto, H.; Wu, C.-C.; LeBleu, V.S.; Kalluri, R. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Is Dispensable for Metastasis but Induces Chemoresistance in Pancreatic Cancer. Nature 2015, 527, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebright, R.Y.; Lee, S.; Wittner, B.S.; Niederhoffer, K.L.; Nicholson, B.T.; Bardia, A.; Truesdell, S.; Wiley, D.F.; Wesley, B.; Li, S.; et al. Deregulation of Ribosomal Protein Expression and Translation Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis. Science 2020, 367, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, F.; Consalvo, N.; Frey, N.; Phipps, A.; Ribba, B. From Waterfall Plots to Spaghetti Plots in Early Oncology Clinical Development. Pharm Stat 2019, 18, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.; Muinelo-Romay, L.; Cebey-López, V.; Pereira-Veiga, T.; Martínez-Pena, I.; Abreu, M.; Abalo, A.; Lago-Lestón, R.M.; Abuín, C.; Palacios, P.; et al. Analysis of a Real-World Cohort of Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients Shows Circulating Tumor Cell Clusters (CTC-Clusters) as Predictors of Patient Outcomes. Cancers 2020, 12, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boral, D.; Vishnoi, M.; Liu, H.N.; Yin, W.; Sprouse, M.L.; Scamardo, A.; Hong, D.S.; Tan, T.Z.; Thiery, J.P.; Chang, J.C.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Breast Cancer CTCs Associated with Brain Metastasis. Nat Commun 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talmadge, J.E.; Fidler, I.J. AACR Centennial Series: The Biology of Cancer Metastasis: Historical Perspective. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 5649–5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Qu, X.; Wang, Z.; Ji, C.; Ling, R.; Yan, C. Leaf-Vein-Inspired Multi-Organ Microfluidic Chip for Modeling Breast Cancer CTC Organotropism. Front Oncol 2025, 15, 1602225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polioudaki, H.; Agelaki, S.; Chiotaki, R.; Politaki, E.; Mavroudis, D.; Matikas, A.; Georgoulias, V.; Theodoropoulos, P.A. Variable Expression Levels of Keratin and Vimentin Reveal Differential EMT Status of Circulating Tumor Cells and Correlation with Clinical Characteristics and Outcome of Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianat-Moghadam, H.; Azizi, M.; Eslami-S, Z.; Cortés-Hernández, L.E.; Heidarifard, M.; Nouri, M.; Alix-Panabières, C. The Role of Circulating Tumor Cells in the Metastatic Cascade: Biology, Technical Challenges, and Clinical Relevance. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochi, T.; Yuki, Y.; Terahara, K.; Hino, A.; Kunisawa, J.; Kweon, M.-N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kiyono, H. Biological Role of Ep-CAM in the Physical Interaction between Epithelial Cells and Lymphocytes in Intestinal Epithelium. Clin Immunol 2004, 113, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J. -h; Oh, S.; Lee, K. -m; Yang, W.; Nam, K.S.; Moon, H.-G.; Noh, D.-Y.; Kim, C.G.; Park, G.; Park, J.B.; et al. Cytokeratin19 Induced by HER2/ERK Binds and Stabilizes HER2 on Cell Membranes. Cell Death Differ 2015, 22, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Characteristic |

Category | Full Cohort |

HR+/HER2- | HR-/HER2+ | TNBC | Fisher exact test, p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at 1st blood collection |

<65 | 30 (60.0) | 17 (54.8) | 11 (68.8) | 2 (66.7) | |

| 65+ | 20 (40.0) | 14 (45.2) | 5 (31.2) | 1 (33.3) | 0.792 | |

| Total | 50 (100) | 31 (100) | 16 (100) | 3 (100) | ||

| Number of Metastatic sites |

1 2 3+ Total |

4 (8.0) 15 (30.0) 31 (62.0) 50 (100) |

4 (12.9) 7 (22.6) 20 (64.5) 31 (100) |

0 (0.0) 7 (43.8) 9 (56.2) 16 (100) |

0 (0.0) 1 (33.0) 2 (66.7) 3 (100) |

0.417 |

| Lung metastasis | N Y Total |

22 (43.1) 29 (56.9) 51 (100) |

14 (43.8) 18 (56.2) 32 (100) |

7 (43.8) 9 (56.2) 16 (100) |

1 (33.0) 2 (66.7) 3 (100) |

1.000 |

| Bone metastasis | N Y Total |

14 (27.5) 37 (72.5) 51 (100) |

6 (18.8) 26 (81.2) 32 (100) |

7 (43.8) 9 (56.2) 16 (100) |

1 (33.0) 2 (66.7) 3 (100) |

0.141 |

| Liver metastasis | N | 25 (50.0) | 16 (51.6) | 7 (43.8) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Y Total |

25 (50.0) 50 (100) |

15 (48.4) 31 (100) |

9 (56.2) 16 (100) |

1 (33.3) 3 (100) |

0.816 | |

| Brain metastasis | N | 34 (68.0) | 24 (77.4) | 9 (56.2) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Y | 16 (32.0) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (43.8) | 2 (66.7) | 0.105 | |

| Total | 50 (100) | 31 (100) | 16 (100) | 3 (100) |

| Clinical Characteristic |

Category | Full Cohort |

HR+/HER2- | HR-/HER2+ | TNBC | Fisher exact test, p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at 1st blood collection |

<65 | 16 (64.0) | 7 (50.0) | 7 (87.5) | 2 (66.7) | |

| 65+ | 9 (36.0) | 7 (50.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (33.3) | 0.246 | |

| Total | 25 (100) | 14 (100) | 8 (100) | 3 (100) | ||

| Number of Metastatic sites |

1 2 3+ Total |

2 (7.7) 9 (34.6) 15 (57.7) 26 (100) |

2 (13.3) 4 (26.7) 9 (60.0) 15 (100)) |

0 (0.0) 4 (50.0) 4 (50.0) 8 (100) |

0 (0.0) 1 (33.0) 2 (66.7) 3 (100) |

0.834 |

| Lung metastasis | N Y Total |

13 (50.0) 13 (50.0) 26 (100) |

8 (53.3) 7 (46.7) 15 (100) |

4 (50.0) 4 (50.0) 8 (100) |

1 (33.0) 2 (66.7) 3 (100) |

1.000 |

| Bone metastasis | N Y Total |

7 (26.9) 19 (73.1) 26 (100) |

2 (13.3) 13 (86.7) 15 (100) |

4 (50.0) 4 (50.0) 8 (100) |

1 (33.0) 2 (66.7) 3 (100) |

0.139 |

| Liver metastasis | N | 11 (42.3) | 6 (40.0) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Y Total |

15 (57.7) 26 (100) |

9 (60.0) 15 (100) |

5 (62.5) 8 (100) |

1 (33.3) 3 (100) |

0.724 | |

| Brain metastasis | N | 18 (69.2) | 11 (73.3) | 6 (75.0) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Y | 8 (30.8) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (66.7) | 0.418 | |

| Total | 26 (100) | 15 (100) | 8 (100) | 3 (100) |

| Biomarker (per mL) | Receptor Effect | Time Effect | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| cCTCs | 0.6591061 | 0.7461176 | 0.840692 |

| CK | 0.4685809 | 0.6062315 | 0.4074604 |

| EpCAM | 0.7158591 | 0.1999038 | 0.0218357 |

| Clusters | 0.9510659 | 0.028952 | 0.0674635† |

| Clusters of 2 | 0.6826174 | 0.0805827 | 0.1121893 |

| cCTC in cluster | 0.4323639 | 0.5820074 | 0.5686966 |

| Clusters >2 | 0.5347161 | 0.0062573 | 0.0069147 |

| CD45 in cluster | 0.9598183 | 0.0401535 | 0.1091464 |

| † Indicates a marginally significant result |

| Biomarker (per mL) | Receptor Effect | Time Effect | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| CK/EpCAM/Trop2 | 0.4802839 | 0.8340946 | 0.8919177 |

| CK/EpCAM | 0.5649867 | 0.0955775 | 0.1789835 |

| Trop2 | 0.5484958 | 0.8870074 | 0.490742 |

| Clusters | 0.966292 | 0.2493243 | 0.5708911 |

| CTC in cluster | 0.7295486 | 0.5810308 | 0.8777693 |

| CD45 in cluster | 0.9998403 | 0.2495356 | 0.5364823 |

| Clusters of 2 | 0.2829963 | 0.6461081 | 0.4631998 |

| Clusters >2 | 0.633026 | 0.2716701 | 0.4975725 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).