1. Introduction

Dehydrated proteins are widely used ingredients in the food industry due to the wide range of applications associated with their technological and functional versatility. This includes the ability to form stable and self-sustaining heat-induced gels, which are of interest to improve texture and mouthfeel in the development of low-fat products. However, gelling ability is a property intrinsically linked to the molecular structure of proteins, which can be significantly altered during dehydration processes.

To further elucidate structural changes in proteins resulting from different dehydration methods, analytical techniques such as Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) offer valuable insights. On one hand, FTIR spectroscopy enables the identification of alterations in protein secondary structure by analyzing characteristic absorption bands, particularly within the amide I region, which is sensitive to the presence of α-helices, β-sheets, and random coil conformations [

1,

2]. Complementarily, XRD analysis assesses the degree of crystallinity or amorphousness in protein powders, providing further information on molecular packing and order by distinguishing between the predominantly amorphous state characteristic of freeze-dried proteins and the increased crystallinity or β-sheet aggregation often observed in conventionally dried simples [

3].

It is well-established that the structural integrity of proteins significantly influences their gelling capacity; proteins maintaining a more ordered conformation are generally better suited for forming robust gel networks, whereas extensive denaturation can lead to less desirable gel characteristics [

4,

5]. In this sense, freeze-dried proteins tend to preserve the native structure and a less aggregated and predominantly amorphous state [

6,

7], which can facilitate the reconstitution in water [

8] and yield low syneresis gel structures [

9]. In contrast, proteins subjected to conventional drying may exhibit more extensive aggregation, promoting the conversion of α-helix to β-sheet conformations [

10] that yield gels with different properties.

In addition, during the heating step required to induce gelation, globular proteins typically undergo significant conformational changes that lead to the exposure of hydrophobic regions that facilitate critical intermolecular interactions for gel formation. It is also established that the strength of heat-induced gels and their elastic behavior significantly increase as the disulfide bond formation via sulfhydryl (SH) groups rises [

11]. Besides, several studies report that the structural integrity, textural behavior and the water retention capacity of the gel depend on the balance between hydrophobic interactions and disulfide crosslinks [

12,

13,

14].

On the other hand, the current demand for low-fat food products has soared as consumers become increasingly health-conscious and seek to reduce their intake of saturated fats for better cardiovascular health and overall well-being [

15,

16]. This shift in dietary preferences is paralleled by a growing emphasis on sustainability within the food industry, as both producers and consumers recognize the importance of minimizing environmental impact and reducing food waste [

17]. Thus, innovative approaches, such as developing functional ingredients from sources traditionally considered waste, have gained traction as part of this broader movement [

18,

19]. By aligning the pursuit of healthier, low-fat alternatives with sustainable production practices, the industry is not only meeting consumer expectations but also supporting the transition toward a more responsible and circular food system.

In this regard, bovine blood is an abundant by-product of the meat industry. It is composed of several key protein fractions (including albumin, globulin, and fibrinogen) which together represent nearly 18% of its total mass [

20,

21]. These component fractions possess a remarkable gelling capability and are often dried to extend their shelf life and facilitate their use as functional ingredients in different applications. Nevertheless, although many authors have evaluated the techno-functionality of these component fractions [

9,

10,

22], there remains a lack of studies addressing the impact of drying methods on the gelling capability of plasma and cell fractions.

This gap in the literature underscores the need for systematic investigations into how proteins from bovine plasma and red cell fractions contribute to gel formation, and how their properties may be harnessed or optimized in food applications. Thus, we aimed to elucidate how different dehydration methods, such as freeze drying versus conventional oven drying, affect the structure of proteins in bovine blood fractions (as precursors for gel formation) and how these alterations impact the properties of edible gels formed from these proteins. By understanding these relationships, researchers can design innovative ingredients that closely mimic the sensory qualities of traditional fats. This knowledge is critical for advancing both the quality and the sustainability of modern food systems.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra Analysis (FTIR) of Protein-Based Powders

The dehydration stage is a critical process that can induce irreversible changes in protein structure, thereby affecting their subsequent functionality. The general analysis of the infrared spectra together with their second derivative, allowed for elucidating the impact of freeze-drying and oven drying on the secondary structure, revealing significant differences influenced by the origin of the protein fraction.

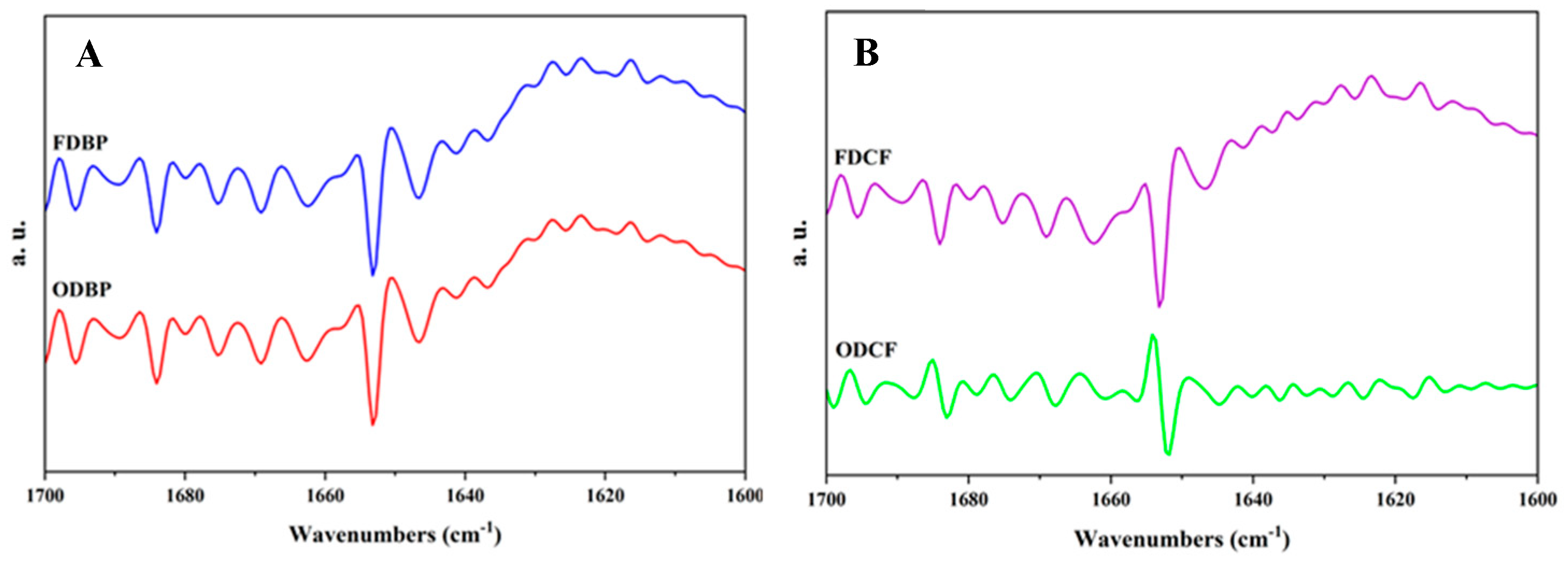

As shown in

Figure 1A, freeze-drying proved to be the method that best preserved the native secondary structure of the plasma fraction proteins (FDBP). This protective effect was evidenced, on the one hand, by the stability of the α-helices, whose characteristic minimum was maintained at 1655.67 cm-1, a value consistent with the α-helical conformation of plasma proteins such as bovine serum albumin [

23]. On the other hand, no significant aggregation of low-frequency β-strands (1620-1640 cm-1) was observed, confirming the non-aggressive nature of freeze-drying, in agreement with that reported in other studies in which freeze-drying was applied to dehydrate protein systems of different origin, including crustacean isolates [

3] and chicken egg white [

24].

In contrast, drying at 35°C (ODBP) induced, on the one hand, a relaxation or destabilization of the α-helices, whose minimum shifted to 1650.76 cm-1 and, on the other hand, the formation of aggregates, evidenced by peaks in the low-frequency region. These changes were striking since, although a denaturing effect of temperature was expected, it is frequently reported for values of 40 °C or higher in convective dehydration techniques [

1,

25,

26].

This unexpected effect was attributed to the formation of differentiated aggregates during the oven-drying process. While ODBP showed a higher β-sheet signal in the low frequency region, the lower intensity in the high frequency region (1670-1690 cm-1) suggested the formation of more disordered aggregates or aggregates with different folding characteristics compared to those that might have formed during freeze-drying. In this case, the lower intensity in the high-frequency region of the oven-dried sample could have reflected a loss or alteration of these more organized structures, such as β-turns or short β-sheets, due to thermal denaturation.

For the cell pack fractions (

Figure 1B), in contrast, neither drying method achieved optimal preservation of the native structure, with atypical results in both cases. Contrary to expectations, freeze-drying (FDCF) caused considerable denaturation, as evidenced by the formation of β-sheets aggregated, indicating that the cellular fraction proteins were intrinsically more susceptible to freeze-drying. This susceptibility was attributed to several factors. First, consideration was given to the inherent complexity of this biological matrix, which, unlike plasma, is a heterogeneous mixture of intracellular proteins with diverse functions and stability, potentially making it more sensitive to phase changes and osmotic stress associated with lyophilization.

Second, the gradual removal of water during primary and secondary lyophilization drying may have led to the loss of essential hydration water surrounding the proteins. This water movement could have destabilized the native structure, exposing hydrophobic residues that promoted interactions between molecules, leading to aggregation. Finally, no cryoprotectants were used in our study, which are commonly employed to stabilize cellular systems during freezing and drying, thus reducing structural damage caused by dehydration and solute concentration, which can induce unfolding and aggregation [

27,

28,

29].

The behavior of the cell fraction during oven drying was also unusual. The ODCF powder spectrum exhibited a clear signal at 1654.24 cm-1, which hinted at an apparent preservation of the α-helices. However, this signal coexisted with the appearance of peaks associated with low-frequency β-sheets, indicative of more severe overall denaturation. These observations suggest a different type of structural rearrangement, where specific helical structures may have been maintained or even rearranged within a highly aggregated and denatured environment. According to Tajoddin

et al [

30], heat is particularly effective in this regard, since, under these conditions, instead of complete denaturation that would result in a random ball, some cellular proteins could have undergone a rearrangement or compaction that increased the proportion or detectability of α-helical structures. However, as observed for bovine plasma, this phenomenon was expected at higher temperatures, since it is established that the aggregation of proteins such as hemoglobin is a sequence of events that initiates above 40 °C [

31].

2.2. Characterization of the Physical State by X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

Although recent scientific literature usually focuses on the crystallization of salts added to suspension buffers during dehydration processes [

32,

33], it is relevant to analyze the fate of salts initially present in the composition of a biological matrix that has not been subjected to previous treatments, since they can significantly influence the properties and stability of the dehydrated powders [

6,

34]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that gentle dehydration processes, such as freeze-drying, promote the formation of amorphous matrices in protein-rich materials, thereby preserving structure and functionality by minimizing thermal stress [

7].

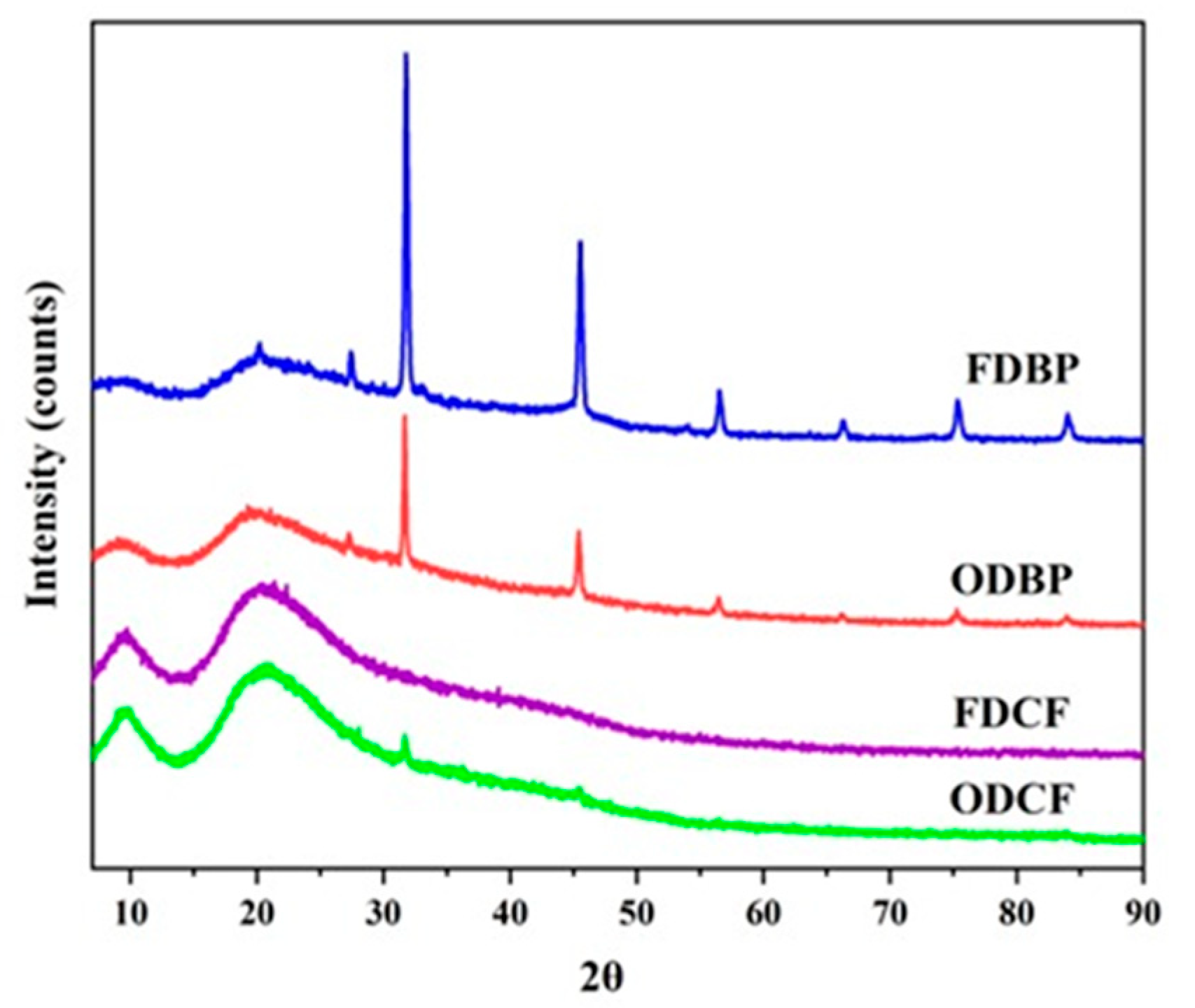

However, the findings on the crystallinity of plasma fraction powders in our study represented a considerable deviation from this expectation, especially in the freeze-drying of bovine plasma, which, without specific additives, promoted crystallization of an endogenous salt. As shown in

Figure 2, the FDBP pattern revealed predominantly crystalline behavior. A sharp and relatively intense peak was observed at 2θ=32°, accompanied by lower intensity signals, suggesting the formation of an ordered phase in the plasma matrix during lyophilization and a different finding from that reported in similar studies, where amorphous behavior predominated [

3], crystallinity was associated with a phase separation of matrix components [

35] or was assessed directly in the gel rather than in the precursor solid [

36].

ODBP, on the other hand, exhibited a combination of amorphous and crystalline phases, characterized by a broad band with a peak centered at 2θ = 20°, indicative of a dominant amorphous phase. Additionally, highly defined and sharp peaks were observed at 2θ = 27 ° and 45°, suggesting that oven drying induced the formation of specific types of crystals, distinct from those observed in FDBP.

According to Li

et al [

37], the similarity in peaks position in FDBP and ODBP indicated crystals of endogenous NaCl (~0.9% of plasma), consistent with the plasma composition, which contains Na+ and Cl- ions dissolved in water endogenously. Rendering XRD patterns, these ions encountered during dehydration (either freeze-drying or oven drying), while water was progressively removed. As the volume of water decreased, the concentration of these ions increased until they exceeded their solubility limit. At that point, the ions could not remain dissolved and began to precipitate, forming a crystalline lattice.

While in FDBP NaCl appeared to have crystallized directly during the freeze-drying process, oven drying provided a different kinetic and thermodynamic environment. As convection drying conditions involved gradual dehydration at temperatures above the freezing point, it might have induced the formation of different polymorphs of salts or even crystallization of other components with lower solubility at that temperature or in the absence of water. Thus, the fate of NaCl was markedly different in both dehydration methods, reflecting the influence of the water removal process and thermal conditions on the final microstructure of the plasma powders.

In contrast, the XRD patterns of the powders obtained from the cell package (FDCF and ODCF) showed a predominantly amorphous behavior, similar to that expected in protein dehydration processes [

3,

7]. The non-crystalline behavior was evidenced by the presence of significant broad bands centered at 2θ = 10 ° and 21°, and by the absence of sharp and defined diffraction peaks. The broad halo at 2θ = 21 °, particularly characteristic of disordered packing of polypeptide chains, was the trademark of amorphous protein aggregates, demonstrating that the amorphous nature of the cell packet matrix was maintained despite the different dehydration methods employed.

The observation of predominantly amorphous patterns in both cell-packet fractions (FDCF and ODCF) was more consistent with expectations for complex proteins, such as hemoglobin, which is the major protein in cell packets. This behavior suggested that, despite differences in drying stress, the major protein matrix of the cell packet maintained a disordered state of packing, evidenced by the broad bands on XRD. Together with the plasma, the cell pack results indicated that the intrinsic composition of the protein fraction is a determining factor in the final physical state of the dehydrated powder, even beyond the choice of drying method.

2.3. Free Sulfhydryl Content in Protein-Based Powders

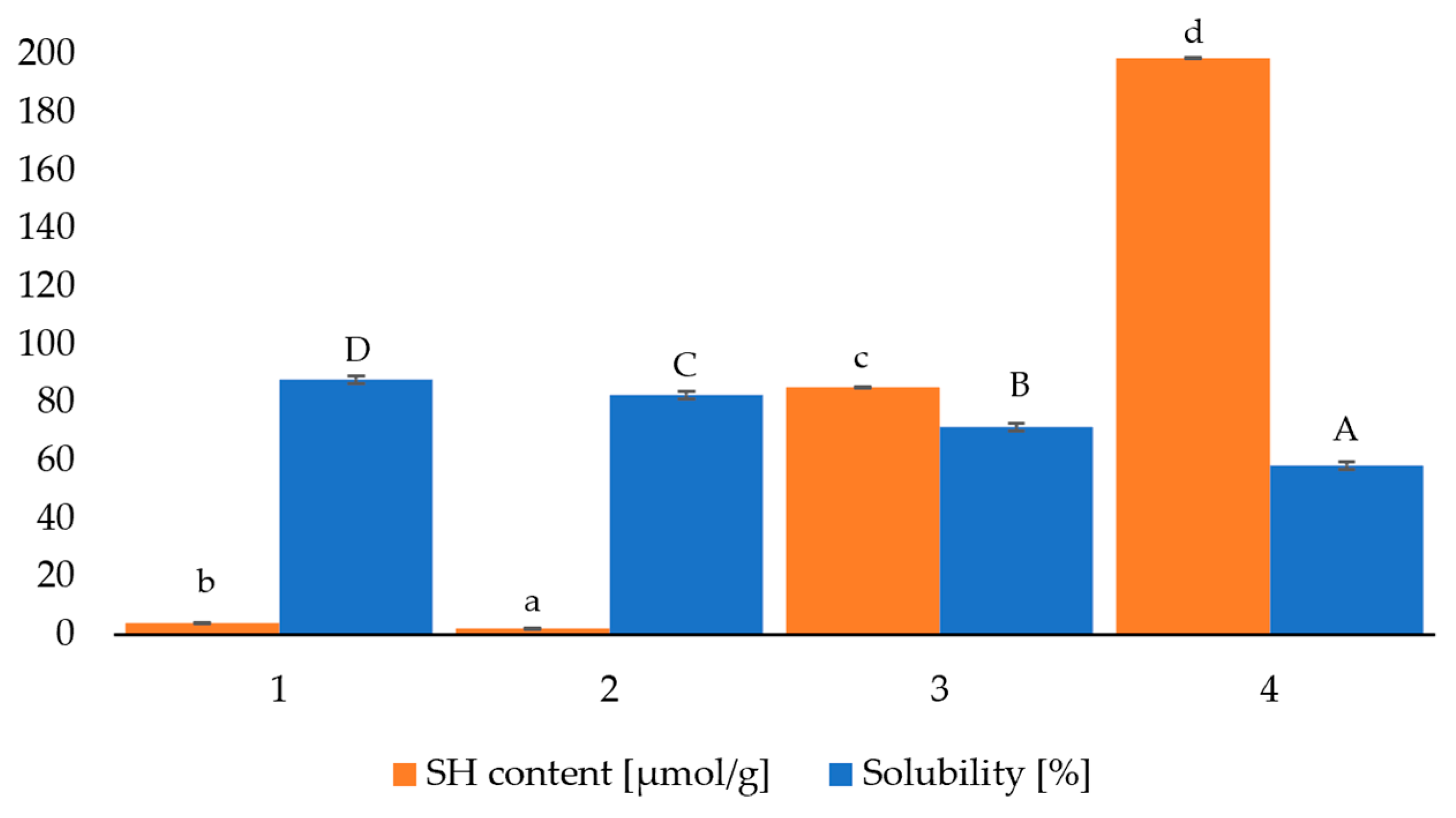

As shown in

Figure 3, both powders derived from the plasma fraction had a much lower SH content than those derived from the cell fraction. The values were 3.91 ± 0.28 µmol/g and 2.01 ± 0.14 µmol/g for FDBP and ODBP, respectively, which was initially considered counterintuitive when associating lyophilized plasma with a better-preserved structure, as suggested by infrared spectra. Therefore, it was inferred that the protein unfolding induced by freeze-drying was less drastic than that produced by oven-drying, which preserved a higher number of SH groups in their free and reactive state. In contrast, thermal denaturation and subsequent aggregation in ODBP might have promoted the formation of intermolecular disulfide bridges, thereby reducing the pool of detectable free SH.

On the other hand, FDCF exhibited a content of 85.37±2.81 µmol/g, significantly lower than the 198.96±0.81 µmol/g present in ODCF, this being the main difference with plasma powders. Furthermore, although a difference in SH contents was expected given the presence in the cell package of cysteine-rich proteins, such as hemoglobin, it was striking that oven drying induced such a high amount of SH. Therefore, the cell-packet powder data suggested, on the one hand, a lower effectiveness of oven drying in inducing oxidation or disulfide bridge formation, which, again, was counterintuitive since heat often promotes oxidation.

However, analysis of the infrared spectra somewhat anticipated this situation. The severe denaturation and formation of aggregated β-sheets detected could have been originated from hydrophobic interactions or hydrogen bridges, rather than the formation of disulfide bridges. Thus, the SH groups were buried (i.e., sequestered) within the dense aggregates without being oxidized, although they were still detected as free.

On the other hand, freeze-drying was more effective in inducing SH oxidation or the formation of disulfide bridges in the cell pack proteins. This apparent pro-oxidant effect may be attributed to the fact that the concentration of solutes during the freezing phase increased the reactivity of SH groups; however, the secondary drying process exposed them to oxygen, promoting their oxidation. Adding to this interpretation, although the considerable formation of low-frequency β-sheets in FDCF indicated denaturation and aggregation, the reduction of free SH suggests that part of this aggregation was mediated by disulfide bonds generated during dehydration.

Compared to other dehydrated proteins, the SH content of the plasma-derived powders was lower than that reported by Niu

et al [

38] for freeze-dried (~ 8 µmol/g) and spray-dried (~ 7 µmol/g) fish myofibrillar protein isolates. At the same time, it was similar to that reported by Upadyahy

et al [

39] for mung bean proteins (~ 6 µmol/g), although considerably lower than that reported by Shen

et al [

40] for freeze-dried gingko seed proteins (~ 24 µmol/g). It should be clarified that no recent studies were found that reported the SH content in powders based on plasma proteins or similar, for which there is information referring to the gel state, such as the study by Dai

et al [

11], who evaluated the SH content in egg white and egg yolk gels added with bovine serum albumin.

2.4. Solubility of Protein-Based Powders

The structural differences suggested by infrared spectroscopy and XRD patterns, together with the content of SH groups, were manifested in the solubility of the protein powders, as shown in

Figure 3. For powders derived from the plasma fraction, FDBP dissolved completely and without difficulty in water at room temperature (~ 25 °C), forming a homogeneous mixture. This maximum solubility was consistent with the structural stability of FDBP, as reflected in the FTIR, and was accompanied by the crystallization of NaCl, which did not compromise the integrity of the proteins and even facilitated the solubilization of the powder.

ODBP, on the other hand, exhibited low initial solubility, leading to the formation of rubbery aggregates that adhered to the vessel's surfaces, a situation that worsened considerably with vigorous stirring. However, the complete dissolution of ODBP was achieved after a prolonged period of contact with water (approximately 6 hours) without mechanical agitation, suggesting a gradual hydration of the gummy aggregates, in agreement with the structural and crystalline changes previously observed.

As for the cellular fraction, FDCF exhibited similar dispersion behavior to ODBP, forming aggregates and requiring a comparable amount of time to reach a total solution. In contrast, complete solubilization of ODCF was much more challenging to achieve, as insoluble aggregates formed as soon as stirring was started. However, complete dissolution of ODCF was possible after a considerably longer resting period (~ 24 h) in contact with water, which confirmed the robustness and density of the aggregates formed.

These findings confirmed that the solubility of a protein powder depends not only on its intrinsic structure but also on the rehydration conditions. The increase in dissolution difficulty as agitation increased and aggregation was promoted in ODBP, FDCF, and, particularly, ODCF was attributed to shear-induced interfacial denaturation and the irreversible nature of specific aggregates. Thus, agitation exacerbated the denaturation and aggregation of powders through shear stress and interfacial denaturation, a well-documented phenomenon in protein-based therapeutics research [

41].

2.5. Minimum Gelation Concentration of Protein-Based Powders

The minimum gelation concentration (MGC) refers to the minimum amount of protein required to form a stable three-dimensional network that can immobilize water and resist flow under specific conditions. It is an essential value in several applications where gelation is a key process, as it allows modulating the texture profile of the food product of interest.

For both FDBP and ODBP, 4% w/v of each powder was enough to prevent runoff in the inverted tube test. However, stability to the touch was achieved at higher concentrations, thus 8% P/V was considered as the MGC. The same pattern was observed with FDCF and ODCF, for which the same MGC value was considered. However, the runoff of cell fraction gels was avoided with a higher amount of powder (6% w/v).

The differential behavior in the solubility of plasma powders had direct implications for gelation efficiency. The optimal solubility of FDBP, attributed to its better preservation of α-helices and the absence of significant aggregation in the powder, allowed proteins to disperse and rehydrate rapidly, facilitating homogeneous gel network formation once gelation was induced. In contrast, the low initial solubility and formation of rubbery aggregates of ODBP, resulting from destabilization of the α-helices and formation of aggregates caused by oven drying, required longer hydration to achieve the protein dispersion necessary for gelation. Despite these differences, the fact that both powders exhibited a similar MGC (8% w/v) to remain stable under manual pressure suggested that, once ODBP proteins were sufficiently dispersed and denatured by heating, their ability to form a gel network was comparable to that of FDBP.

A similar MGC pattern was observed for the cell pack fractions (FDCF and ODCF), with their MGC also being set at 8% w/v for touch stability. However, a higher concentration (6% w/v) was required to avoid initial runoff, suggesting a lower initial efficiency in network formation compared to plasma proteins. This difference was directly related to the lower solubility and marked aggregation tendency observed in the cell pack powders.

Relative to other studies, the gelling performance of our powders was comparable to that reported by Fernandez

et al [

9], who reported similar MGC when using mixtures of bovine blood protein fractions to obtain hydrogels. However, our powders were less efficient than freeze-dried tuna collagen proteins, although more efficient than the same spray-dried proteins, as reported by Azaza

et al [

42]. These authors concluded that the freeze-dried collagen proteins had an MGC of 6 % w/v, which implied a higher gelling capacity than the spray-dried ones, whose MGC was 20 % w/v.

At the same time, our powders had a lower gelling capacity than the porcine plasma proteins (freeze-dried or spray-dried) studied by Hou et al [

43], who reported an MGC of 6 % w/v for both freeze-dried and spray-dried powders. However, the authors did not mention the relationship between MGC and touch stability, thus the efficiency of our powders was probably similar.

2.6. Structural Characterization of Protein-Based Gels

The pre-gelation conformational history, determined by powder drying or processing methods, defines the molecular starting point from which proteins reorganize their interactions and assemble new networks during the gelation process. Thus, the presence or absence of certain structural elements, such as α-helices or β-sheets, influences the compaction, elasticity, and water-holding capacity of the resulting gel.

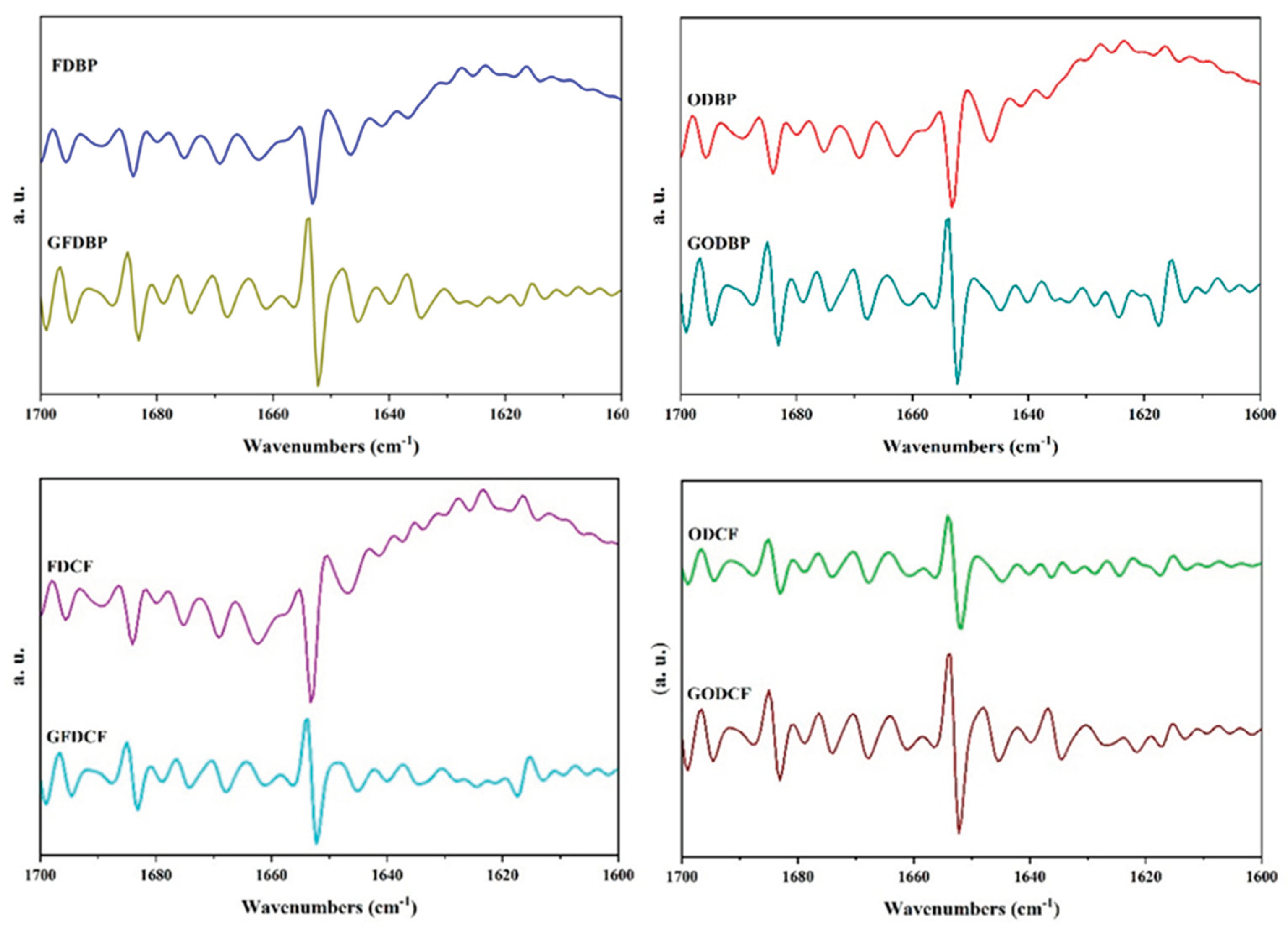

As shown in

Figure 4, the comparative analysis of the four samples revealed distinctive patterns. On the one hand, the central role of β-sheets, a robust and universal molecular mechanism in the gelation of all proteins studied, regardless of their origin (plasma or cell packet) or initial drying method, was highlighted, underscoring the importance of these interactions in forming the gel network. On the other hand, the most notable differences between samples were observed in the behavior of the α-helices, suggesting a differential susceptibility to rehydration and heating processes, as explained below.

Proteins from the cell fraction (FDCF, ODCF) and those oven-dried (ODBP, ODCF) showed a bigger tendency to destabilization or reorganization of their α-helices compared to the freeze-dried plasma fraction (FDBP), which showed better preservation or even slight compaction of these structures. These shifts could have been due to inherent differences in the composition and stability of the proteins in each fraction, as well as the impact of the drying method on their native powder conformation.

Briefly, the results of the second derivative analysis provided detailed insight into the conformational changes of the protein's secondary structure during gelation. The formation of the gel network was strongly driven by the creation of new beta-sheet aggregates, in agreement with the studies of Du et al [

10], who evaluated the gelation of chicken proteins in the presence of fibrin and verified that the increased exposure of hydrophobic groups and protein aggregates increased the amount of β-sheets, which contributed to a strong protein-protein interaction.

In contrast, the fate of α-helices turned out to be more sensitive to the origin of the protein and the previous dehydration method. On the one hand, our results agreed with what has already been established for the fate of α-helices during heating, as reported by Goulding

et al [

44], who verified the reduction of α-helix domains when evaluating conformational changes of bovine lactoferrin subjected to different heating times. On the other hand, the dependence of the fate of α-helices on the applied drying method agrees with that reported by Hou

et al [

43], who evaluated the gelation of dehydrated plasma proteins and observed that the secondary structure of the gels of spray-dried plasma protein powders exhibited higher α-helices content than that of the freeze-dried powder and the original plasma in liquid state.

FTIR analysis corroborated that the extensive creation of intermolecular aggregates of β-sheets predominantly drove gel network formation in all samples. The MGC of 8% w/v (for touch stability) was consistent with the need for sufficient protein concentration to generate a critical mass of these binding sites. In contrast, subtle differences, such as the slightly higher amount to prevent runoff in the cell fractions (6% w/v vs 4% w/v for plasma), could have been related to the less stable behavior of the α-helices in these fractions, or else to differences in protein composition that necessitated a higher concentration to initiate the formation of a self-sustaining network.

2.7. Disulfide Bridge Content in Protein-Based Gels

Disulfide (S-S) bridges are a critical factor in determining the structure and properties of protein gels, as they contribute to the formation of a stabilized covalent network. They are formed through the oxidation of SH groups present on the cysteine side chains, thus stabilizing the three-dimensional network and reinforcing the gel structure. They determine covalent crosslinking, and, at first glance, one might expect a direct correlation between the amount of free SH in the powder (precursors) and the amount of S-S formed in the gel (product).

However, our data showed a more complex pattern. On the one hand, the plasma gels, GFDBP and GODBP, exhibited significantly similar S-S content (

Table 1), despite coming from powders with different SH contents (FDBP contained twice as much as ODBP). This behavior suggested that the dehydration method did not substantially impact covalent crosslinking by this route in this fraction. On the other hand, for the cell fraction gels, a strong and direct relationship was observed with SH levels in the precursor powders. ODCF, with the highest amount of SH, also produced the gel with the highest amount of S-S.

In plasma gels, oven drying (ODBP) exposed fewer SH groups in the powder than freeze drying (FDBP), but this did not translate into lower S-S in the gel. This suggested that the accessibility of SH in the powder and its subsequent unfolding during heating were complex and nonlinear with the total SH content. In contrast, for the cell fraction gels, oven drying (ODCF) generated a powder with twice the amount of free SH as freeze-drying (FDCF), resulting in nearly twice the amount of S-S in the gel. This indicated that oven drying was more effective in preserving or exposing the free SH groups in the cellular proteins, which allowed them to form a denser disulfide network during gelation.

As seen, the S-S values complemented the analysis of secondary structures by infrared spectroscopy. While the formation of aggregated β-sheets was the universal and primary mechanism enabling gelation in all samples, the contribution of disulfide bridges varied significantly between plasma and cellular fractions. Also, S-S impact was modulated by the drying method applied to the precursor powder.

Thus, the proteins in the cellular fraction had a much higher ability to form disulfide bonds, which was directly related to the SH content in the powder and anticipated gels of higher hardness. On the contrary, disulfide bridge formation appeared to reach a threshold in the plasma fractions, or else be limited by accessibility or kinetic factors, beyond the initial SH content. Thus, the noticeable ability of cell proteins to form a large number of disulfide bridges during gelation (evidenced by the high S-S values in the cell-pack gels, 151.87 µmol/g for GFDCF and 297.33 µmol/g for GODCF) was considered the main driver for achieving gel stability, compensating for the initial denaturation and low solubility of the powders.

2.8. Physical Properties of Protein-Based Gels

FTIR data on the resulting gels showed that, regardless of the drying method, the gelation process tended to homogenize the protein structures toward a high β-sheet state, which is a common mechanism of gelation for many proteins. However, the previous dehydration history of the powders subtly influenced this restructuring and, more markedly, the final textural properties.

In this sense, a finding that extended our knowledge of plasma protein gelation was the higher hardness of the GODBP (oven-dried plasma) gel compared to the GFDBP (freeze-dried plasma) gel, despite both gels showing similar disulfide bridge content (

Table 1). This non-correlation was considered novel because gel hardness often correlates directly with disulfide-mediated covalent crosslinking density. However, our results suggested that the quality of the initial drying-induced aggregation is as essential as the amount of covalent bonds formed during gelation in determining the final texture, as discussed below.

The ODBP powder, with its lower initial solubility and tendency to form rubbery aggregates, likely already contained pre-aggregates or less dispersed structures. These pre-aggregates could have acted as nucleation points that, upon heating, formed a gel network with a higher packing density or stronger hydrophobic interactions, which contributed to the hardness, even though the disulfide formation was comparable to that of the freeze-dried plasma powder.

For the cell pack fractions, in contrast, disulfide bridge formation was significantly higher in GODCF compared to GFDCF, which was a direct consequence of the higher SH exposure in the ODCF powder. This finding, although expected given the abundance of cysteines in hemoglobin, was a quantifiable input on the ability of oven drying to enhance the formation of a massive covalent network in this fraction. Paradoxically, the extreme insolubility of the ODCF powder contrasted with the low syneresis of its gel (GODCF), which was comparable to that of plasma gels.

While the freeze-dried cell fraction gel (GFDCF) exhibited considerably higher syneresis, the gel capacity of the same fraction oven-dried GODCF proved more efficient in water retention, despite its initial rehydration difficulties. This contradictory effect suggested that the massive crosslinking by disulfide bridges in GODCF, coupled with the efficient formation of low-frequency β-sheets during gelation, might have created a highly dense and robust network capable of effectively trapping water. At the same time, the stress of oven drying might have preconditioned the cell pack proteins for more efficient reassembly into a gelled network once the initial solubility barriers were overcome.

Summarizing, plasma gels (especially GODBP) achieved considerable hardness with moderate disulfide input, where the efficiency of the β-sheet network and the behavior of the α-helices were the key to very low syneresis. In contrast, cell-fraction gels did not reach the maximum hardness and exhibited significantly higher syneresis, despite forming a substantial volume of disulfide bridges (GODCF > GFDCF). This suggested that while disulfides created a robust network, the overall conformation of these proteins and the nature of their interactions (including the alteration of α-helices and the specific structure of β-sheets) might lead to a less efficient network in terms of water retention, or more pronounced shrinkage despite their strength. The high density of covalent bonds may generate a stiffer network, but with less adaptive capacity to stably encapsulate water.

In comparison to that reported in other studies of animal-derived protein gels, the hardness of these gels (FDBP, FDCF and ODCF) was similar to those reported by Fernandez

et al [

9] (~ 1.6 N) and Hou

et al [

43] (~ 1.2 N), who developed heat-induced gels from mixed gelling agents composed of mixtures of bovine blood protein fractions and porcine plasma gels, respectively. At the same time, the hardness of FDBP, FDCF, and ODCF was slightly higher than that reported by Babaei et al [

46] (~ 0.78 N), who evaluated the properties of whey protein gels with and without the addition of polysaccharide mixtures and CaCl2.

Compared to traditional fat sources in bakery (H

margarine~ 4.5 N) and meat products (H

pork backfat ~ 14.4 N), the hardness of all gels was considerably lower. While this appears to be a disadvantage, it should be noted that hardness is not the sole determinant of the functionality of a fat substitute gel. Therefore, a significant difference in hardness does not necessarily imply lower efficiency [

45], as long as it can maintain a structure and behavior suitable for the desired application. In other words, the performance of a substitute must be evaluated considering the set of physical properties, as the functionality in food applications depends on both the interaction of these attributes and the context of use. At this point, syneresis, a key indicator that quantifies the gel's tendency to release water under specific conditions, becomes relevant.

In our study, the syneresis values of all gels were extremely low compared to the values usually reported for gels from similar proteins. This was interpreted as synonymous with the power of protein-based powders to generate networks with high water holding capacity. However, it should be noted that the values corresponded to spontaneous syneresis tests, which makes comparison with the existing literature difficult, since most studies report syneresis values under centrifugation conditions.

Therefore, our results indicate that protein-based powders possess physicochemical properties suitable for generating functional gels as fat substitutes in low-fat foods. The efficiency with which these powders form gelled networks and retain water highlights their potential to partially or fully replace fat in food matrices. Although initially designed for application in meat products, the final use of the powders and the corresponding gel will depend on the sensory and functional characteristics required in each specific food.

3. Conclusions

Our findings elucidate how the specific dehydration method employed for bovine plasma and red blood cell fractions (gel precursors) induces distinctive structural alterations in protein powders. Notably, the crystallization of endogenous NaCl in freeze-dried plasma powders, as opposed to the generally expected amorphous state, correlates with superior rehydration and functional properties in the subsequent gels.

At the same time, the pre-existing alterations in protein structure strongly influence the dynamics of heat-induced gelation and, consequently, the final physicochemical and textural characteristics of the resulting gels. These changes include initial challenges in rehydrating some precursors during gelation, which can be overcome to obtain highly functional gels, as well as a lack of correlation between covalent reticulation and physical gel properties.

On one hand, the paradoxical extreme insolubility of the oven-dried cell fraction powder, despite the high amount of exposed sulfhydryls, results in a gel with remarkably low syneresis due to extensive disulfide crosslinking. On the other hand, the dissociation between gel hardness and disulfide content in plasma gels underlines that covalent bonds do not solely govern the texture of heat-induced gels. Still, it is significantly determined by the non-covalent aggregation state established during the precursor drying step.

These contributions provide additional information on the intricate relationship between the processing history of the protein precursors and the resulting gel properties, which is essential for tailoring their gelation performance to various food applications. By understanding how specific drying-induced structural modifications in protein powders affect the mechanisms and characteristics of gel formation, this research provides insights into optimizing the production of functional protein ingredients from bovine blood byproducts. Nevertheless, while key structural changes were identified using FTIR and XRD, the scope of characterizing the molecular mechanisms of aggregation and gel microstructure at the nanometer level was limited. Furthermore, the apparent preservation of some α-helices in the oven-dried cell fraction, despite macroscopic denaturation, highlights the need for a more thorough characterization of this phenomenon. These additional studies could contribute to optimizing the use of these byproducts in the food industry, thereby enhancing sustainability and the development of innovative ingredients, as well as sustainable, high-quality food systems.