1. Introduction

Pulmonary delivery of biologics represents an effective approach for treating both respiratory and systemic diseases. The pulmonary route offers several therapeutic advantages, including rapid onset of action, high local drug concentrations at the site of disease, and avoidance of first-pass metabolism[

1]. Dry powder inhalers are widely used for pulmonary drug administration due to their portability, ease of use, and minimal need for patient coordination during inhalation[

2]. Despite these benefits, formulating biologics as dry powder formulations remains challenging. Critical factors such as the physicochemical stability of the biologic in the dry state and the aerodynamic performance of the powder must be optimized to ensure deep lung deposition and therapeutic efficacy.

Spray drying is widely employed to produce inhalable dry powders with suitable aerodynamic properties for pulmonary administration[

3]. In this process, biologics are co-formulated with stabilizing excipients that form an amorphous matrix, thereby preserving structural integrity during both drying and storage[

2,

4]. Inulin, a polysaccharide with a relatively high glass transition temperature (Tg), has been investigated for its potential to enhance protein stability in spray-dried formulations[

2]. Compared to disaccharides such as sucrose and trehalose, inulin offers advantages due to its higher Tg, allowing it to remain in the glassy state at high temperatures and RHs, thereby improving its stabilizing capacity[

5,

6]. However, under conditions of high RH, the Tg of inulin may decrease below 20 ± 2 °C, resulting in increased translational molecular mobility and promoting physical instability, including particle fusion through viscous flow. This may negatively impact both protein stability and aerosol performance[

7,

8,

9].

To mitigate moisture-induced challenges related to dispersibility, hydrophobic amino acids such as leucine are frequently incorporated into spray-dried formulations. Leucine exhibits moderate surface activity and low aqueous solubility (22 mg/mL at room temperature), enabling its migration to the droplet surface during spray drying. Once enriched at the interface, leucine forms a shell that minimizes interparticle cohesion, thereby improving powder dispersibility and directly enhancing aerodynamic performance[

10,

11,

12]. This aerodynamic benefit is strongly concentration dependent: optimal aerosolization is generally achieved at 2–5% w/w leucine, whereas higher levels (≥10% w/w) can instead compromise aerodynamic properties. At elevated concentrations, leucine induces a morphological shift from spherical to corrugated dry powder particles and promotes the formation of larger surface crystals, resulting in a heterogeneous, non-uniform shell that diminishes aerodynamic properties[

1,

8,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Although leucine’s dispersibility-enhancing effects are well established, its role in preventing moisture-induced destabilization is less clearly defined. Due to its hydrophobic nature leucine may act as barrier against moisture induced destabilization. Previous research has shown that hydrophobic amino acids, including leucine, can provide moisture protection in spray-dried powders[

17,

18]. For example, trehalose–leucine formulations stored at high RH (>50%) retained favorable aerodynamic properties after storage despite trehalose transitioning to the rubbery state[

16,

18,

19]. In the study of Zhang et al. 5% (w/w) leucine inhibited trehalose recrystallization at 55% RH[

16]. However, Wang et al. found that leucine could not prevent the transition to the rubbery state of trehalose at 90% RH[

19]. Similarly, in addition to sugars, small molecule drugs (e.g., disodium cromoglycate and salbutamol) and biologics (e.g., bovine serum albumin), co-formulated with leucine have shown preserved aerosol performance after storage at high RH[

8,

14,

20,

21].

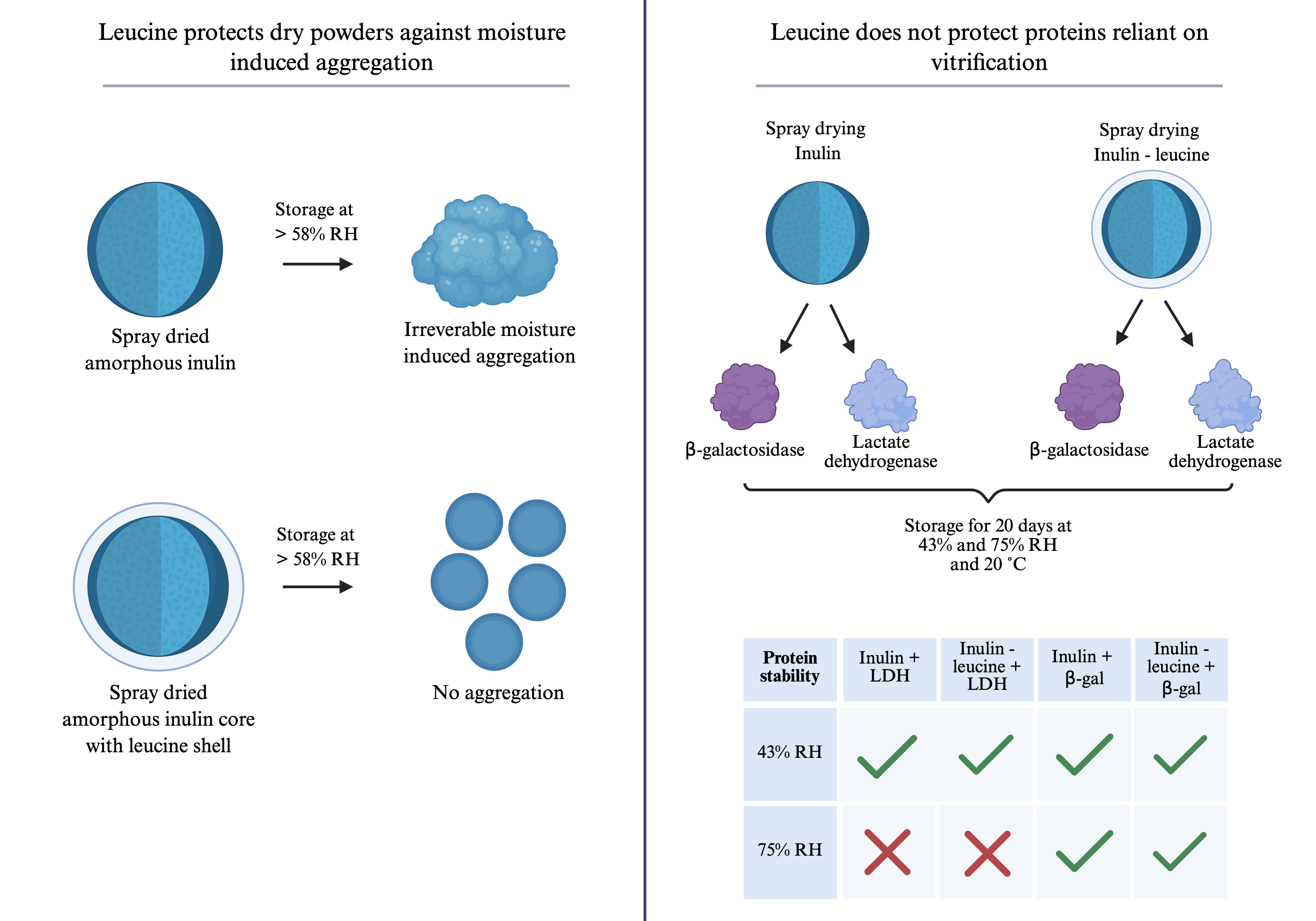

These findings indicate that leucine can protect dry powders from irreversible moisture-induced aggregation, but it does not prevent a transition from the glassy to the rubbery state of the co-spray-dried amorphous excipient at high RH[

19]. This limitation is critical, as protein stability depends on distinct stabilizing mechanisms. Nguyen et al. demonstrated that, when freeze-dried with arginine-pullulan combinations, some proteins are mainly protected through water replacement, whereas others rely more strongly on vitrification[

22]. Whether these mechanisms operate similarly in spray-dried proteins with inulin, with or without leucine, remains unclear. In the water replacement mechanism, sugars substitute for water by forming hydrogen bonds with the protein, thereby maintaining structural integrity of the protein even under plasticized conditions[

4,

16,

23]. In contrast, vitrification stabilizes proteins by embedding them in a matrix in the glassy state that kinetically immobilizes molecular motion. Under high RH, however, moisture uptake induces plasticization, lowering the Tg below the storage temperature. This reduction in Tg increases translational molecular mobility, and stabilization of the biologic by vitrification is lost[

23]. Because leucine cannot prevent water uptake and subsequent plasticization, proteins of which the stabilization relies on vitrification, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), may lose stability once the Tg is surpassed. Therefore, it remains unclear whether proteins like LDH can be effectively stabilized when co-formulated with a sugar and leucine stored under high-humidity conditions.

To date, to the best of our knowledge, it was neither investigated whether leucine can protect inulin-based spray-dried formulations from irreversible particle aggregation, nor has this been related to the stability of encapsulated proteins that rely on stabilization mechanisms (i.e., vitrification and/or water replacement). In this work, we address this gap by systematically evaluating the effect of leucine on inulin-based powders under controlled RH conditions (43%, 58%, 69%, and 75%) at 20 ± 2 °C. First, the physicochemical properties and primary particle sizes were examined to assess the influence of leucine on the moisture sensitivity of inulin. In parallel, the stabilizing capacity of inulin, with and without leucine, was investigated using two model enzymes with distinct stabilization mechanisms: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and β-galactosidase (β-gal). Together, this study provides a novel framework for assessing the role of leucine in mitigating irreversible moisture-induced aggregation in spray-dried inulin-based formulations and clarifies its relevance for protein stabilization under high humidity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Inulin (Frutafit TEX, molecular weight 4 kDa) was generously provided by Sensus. L-leucine was purchased from Ofipharma (1711027.1653). HEPES was acquired from Sigma Aldrich (H4034-100G). Sodium dihydrogen phosphate (1.06342.1000), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (1.04873.1000), disodium hydrogen phosphate (1.06580.1000), O-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) (4151737) and lactate dehydrogenase, rabbit muscle (427217-25KU) were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Magnesium chloride hexahydrate (63033) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) (A3912-50G) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). β-galactosidase (GAH-201, 8176409000) obtained from Sorachim (Lausanne, Switzerland). Potassium carbonate (209619-500G), strontium chloride and sodium bromide (310506-500G) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Sodium chloride (76051275-1000) was purchased from Boom. NADH (39267135) was purchased from Roche diagnostics. Sodium pyruvate was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (P2256-5G).

2.2. Formulations for Spray Drying

Two placebo formulations were made: 1) inulin (2.5 w/v) and 2) inulin (2.5% w/v) supplemented with 4% leucine (w/w). Furthermore, four protein formulations were made: 3) inulin (2.5% w/v) with β-gal (0.03% w/v), 4) inulin (2.5% w/v), 4% leucine (w/w) and β-gal (0.03% w/v), 5) inulin (2.5% w/v) with LDH (0.03% w/v) and 6) inulin (2.5% w/v), 4% leucine (w/w) and LDH (0.03% w/v) (

Table 1). All formulations were prepared in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). A weight ratio of 1:99 protein (β-gal or LDH) to total solute content (inulin, leucin and HEPES) was used.

2.3. Spray Drying

Spray drying was carried out using a Büchi B-290 system combined with a B-296 dehumidifier. A feed rate of 1 mL/min was applied using an NE-300 syringe pump (ProSense B.V.) connected to a 60 mL syringe (Codan B.V.). The formulation was transferred from the syringe to the nozzle (1.5 mm cap) through rubber tubing. Atomizing air was set to 601 Ln/h (rotameter at 50 mm), with an inlet temperature of 60 °C and aspirator operating at full capacity (100%). These conditions yielded an outlet temperature of 36 °C. The powder yield, typically above 80%, was determined gravimetrically by comparing the powder collection vessel mass before and after drying. Obtained powders were either analyzed directly or stored at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C) and 43%, 58%, 69% or 75% RH without lid for 2 hours, 6 hours, 1 day, 5 days and 20 days. A 43% RH environment was established by placing a saturated potassium carbonate solution in a desiccator. A 58% RH environment was established by placing a saturated sodium bromide solution in a desiccator. A 69% RH environment was established by placing saturated strontium chloride solution in a desiccator. A 75% RH environment was established by placing saturated sodium chloride solution in a desiccator. Each formulation was prepared as a single batch to ensure that all subsequent tests were conducted on material from the same production lot.

2.4. mDSC

The Tg of spray dried inulin powders, both with and without 4 wt-% leucine (formulations 1 and 2), was determined after spray drying by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a Q2000 calorimeter from TA Instruments. Roughly 5–10 mg of spray-dried powder was put in a T-zero pan without a lid. Each sample was first heated to 90 °C at a rate of 20 °C per minute and then held isothermal for 15 minutes to ensure complete water evaporation. Consequently, the samples were cooled at a rate of 20 °C per minute to -90 °C. Lastly, the samples were heated again to 180 °C at a rate of 20 °C per minute. The Tg was identified by finding the inflection point in the reversing heat flow versus temperature graph. Spray-dried inulin with and without 4 wt-% leucine was stored in open glass vessels for 1 day under controlled conditions of 43%, 58%, 69%, and 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C. Following storage, the Tg was determined using DSC with a heat-cool-heat run in closed aluminum T-zero pans. Initially, samples were cooled to –90 °C and held for 10 minutes. Subsequently, they were heated to 90 °C at a rate of 20 °C per minute. This thermal cycle was repeated by cooling the samples again to –90 °C, followed by reheating to 90 °C, both at a heating rate of 20 °C per minute. The Tg was identified by locating the inflection point on the first heat flow versus temperature curve. All analyses were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.5. X-Ray Powder Diffraction

X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) was carried out using a Bruker D2 Phaser (Billerica) on placebo formulations of spray-dried inulin, both with and without 4 wt-% leucine (formulations 1 and 2) directly upon spray drying. Measurements were taken across a 2θ range of 5–60°, with steps of 0.05° and a duration of 1 second per step. The detector aperture was fixed at 5°, and the stage rotated at 15 revolutions per minute during data collection. A 1 mm divergence slit and a 3 mm air scatter screen were applied. Samples were placed in a Si low-background holder. Formulation 1 and 2 were measured once directly after spray drying.

2.6. Dynamic Vapor Sorption

The water sorption behavior of spray dried inulin or inulin with 4 wt-% leucine (formulations 1 and 2) were assessed using a dynamic vapor sorption (DVS)-1000 gravimetric analyzer (Surface Measurement Systems Ltd., London, UK). Samples weighing roughly 10 mg were tested at 25 °C under ambient pressure. Moisture uptake by the inulin and inulin with 4 wt-% leucine formulation were monitored over a relative humidity (RH) range of 0% to 90%, increasing in 10% steps where the RH was raised only after mass equilibrium was reached, defined as a change below 0.5 μg over a 10-minute interval. Furthermore, moisture uptake of the inulin and inulin with 4 wt-% leucine formulations was monitored at set RHs (43%, 58%, 69% and 75%). The measurement was considered finished when an equilibrium was reached at 600 minutes.

2.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis was performed to determine the moisture content of spray-dried inulin formulations, with and without 4 wt-% leucine (formulations 1 and 2). Samples were stored for 1 week at controlled conditions of 43%, 58%, 69%, and 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C without lid. TGA was conducted in duplicate by heating the samples from room temperature to 95 °C at a rate of 10 °C per minute. Weight loss up to 95 °C was used as a measure of the water content in the samples.

2.8. Primary Particle Size Analysis

Geometric size distribution of spray-dried inulin and inulin with 4 wt-% leucine (formulations 1 and 2) were assessed in triplicate by laser diffraction. A RODOS dry powder disperser, operating at 3 bar, was used in combination with a HELOS BF laser diffractometer (Sympatec) fitted with an R3 lens (100 mm). Roughly 10 mg of powder was placed on a spinning disk, and the measurement started once optical density reached 0.2% on channel 30. Each scan lasted 3 seconds. Particle size parameters (X50) were determined based on Fraunhofer diffraction theory.

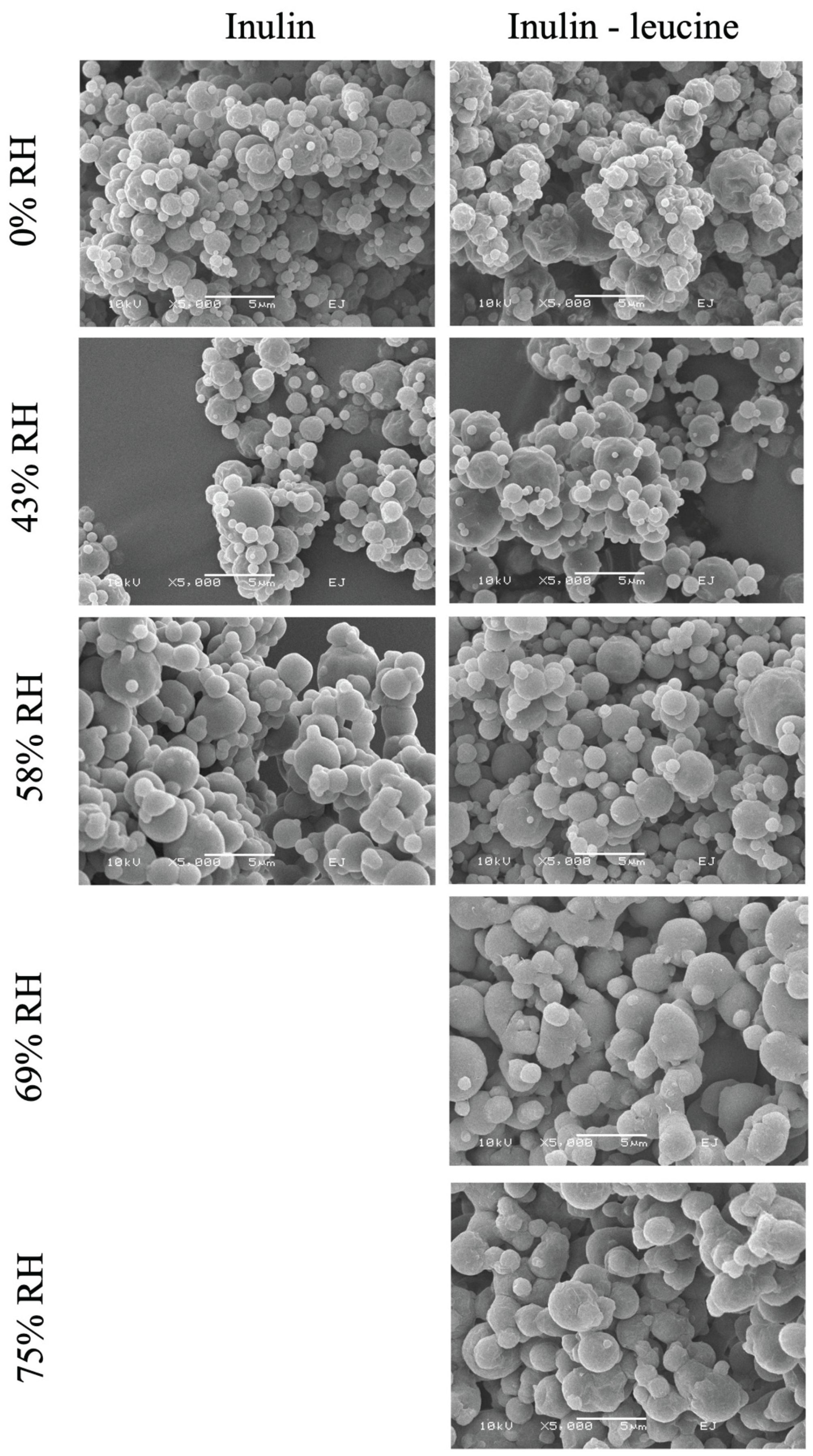

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Particle morphology of spray dried inulin and inulin with 4 wt-% leucine (formulations 1 and 2) were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Spray dried inulin and inulin 4 wt-% leucine were analyzed by SEM directly upon spray drying and after storage for 1 day at 0%, 43%, 58%, 69% and 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C without lid. A JSM 6460 microscope (Jeol) was used. Powder samples were mounted onto aluminum stubs with double-sided carbon tape. Before imaging, a gold/palladium layer (~10 nm) was applied by sputter-coating using a JFC-1300 auto fine coater (Jeol). Images were acquired under vacuum at 10 kV acceleration voltage, a 10 mm working distance, and a spot size of 25.

2.10. Storage Stability of Spray Dried Model Proteins

To evaluate storage stability, spray dried inulin with β-gal or LDH and inulin with 4 wt-% leucine with β-gal or LDH (formulations 3-6) were stored at 43% or 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C. Samples were stored at these controlled conditions without lid for 5 days and 20 days. The enzymatic activity of two model enzymes, β-gal and LDH, was measured to assess their stability, following the method described by Tonnis et al.[

24]. For β-gal, activity was quantified using a kinetic assay based on the conversion of ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG) (colorless) to the chromogenic product ortho-nitrophenol (yellow). LDH activity was determined by its ability to convert pyruvate to lactate. Enzyme stability was expressed as the percentage of remaining activity relative to the theoretical value derived from a calibration curve.

2.11. Statistics

Results are shown as mean with standard deviation (SD), and both sample size and number of replicates are indicated in the relevant figure captions. For evaluating differences across multiple groups, a two-way ANOVA was employed, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically meaningful. All analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism software, version 10 (GraphPad Software).

3. Results

3.1. Dry Powder Characteristics of Spray Dried Inulin and Inulin-Leucine Formulations

Initially, the physicochemical characteristics of spray-dried inulin, both with and without the addition of 4 wt-% leucine, were evaluated to elucidate the influence of leucine incorporation. DSC measurements conducted immediately post spray drying indicated a Tg of 134.01 ± 0.29 °C for the inulin formulation without leucine. This Tg was slightly, yet significantly, higher than that of the leucine-containing formulation, which exhibited a Tg of 130.13 ± 0.37 °C (

Table 2,

Figures S1 and S2). Subsequently, the Tg of spray dried inulin was examined after 1 day of storage under controlled RH conditions of 43% and 58% at 20 ± 2 °C. After storage at 43% RH, a distinct Tg was observed at 42.41 ± 1.54 (

Table 2,

Figure S1). At 58% RH, the Tg remained detectable. However, the glass transition became broader and less sharply defined at 16.70 ± 2.15 (

Table 2,

Figure S1). At 69% and 75% RH, the spray-dried inulin samples exhibited viscous flow, which prevented further DSC analysis due to handling problems (

Figure S3). Nevertheless, the Tg of spray-dried inulin stored at 69% and 75% RH can be expected to fall below room temperature (20 ± 2 °C), as inferred from the Tg values obtained for samples stored at 0% to 58% RH. Comparable trends were noted for spray-dried inulin containing 4 wt-% leucine. Following storage at 43% RH and 20 ± 2 °C, a distinct Tg was recorded at 29.82 ± 1.89 °C. At 58% RH and 20 ± 2 °C, although the Tg broadened and became less distinct, it remained observable at 3.41 ± 4.01 °C (

Table 2,

Figure S2). In contrast, at 69% and 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C, the Tg was highly diffuse and challenging to identify reliably (

Figure S2), but based on the lower RH data, these Tg values lay below room temperature (20 ± 2 °C). The results indicate that exposure to high humidity leads to plasticization of the inulin matrix, thereby reducing its Tg.

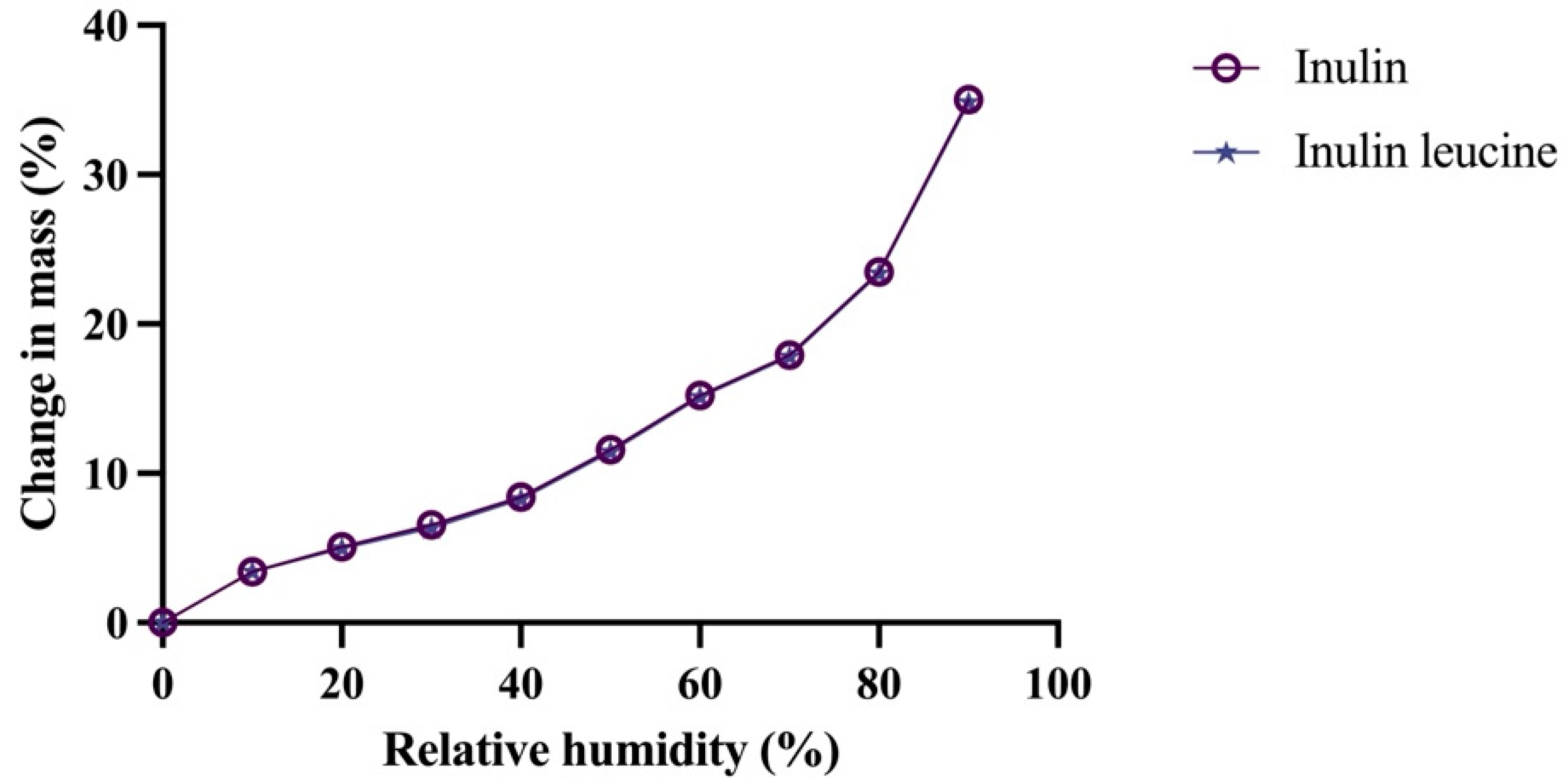

DVS analysis was subsequently conducted to investigate the moisture uptake profiles of both formulations. Comparable moisture sorption behavior of spray dried inulin and spray dried inulin with leucine was observed, indicating that the addition of leucine did not significantly alter the hygroscopicity of spray-dried inulin (

Figure 1). Furthermore, overall moisture uptake increased proportionally with RH and was similar for both formulations (

Figure S4). TGA supported these findings, demonstrating increased weight loss at higher RH, with no significant differences between the two formulations (

Figure S5). Finally, XRPD analysis confirmed the amorphous nature of spray dried inulin and inulin with 4 wt-% leucine formulations immediately post spray drying, as evidenced by the absence of distinct Bragg peaks (

Figure S6). Although leucine is known to crystallize upon spray drying, the concentration used (4 wt-%) was insufficient to detect crystalline domains by XRPD[

8,

14]. In summary, these results demonstrate that incorporating 4 wt-% leucine does not significantly affect the moisture sorption behavior or solid-state characteristics of spray-dried inulin powders.

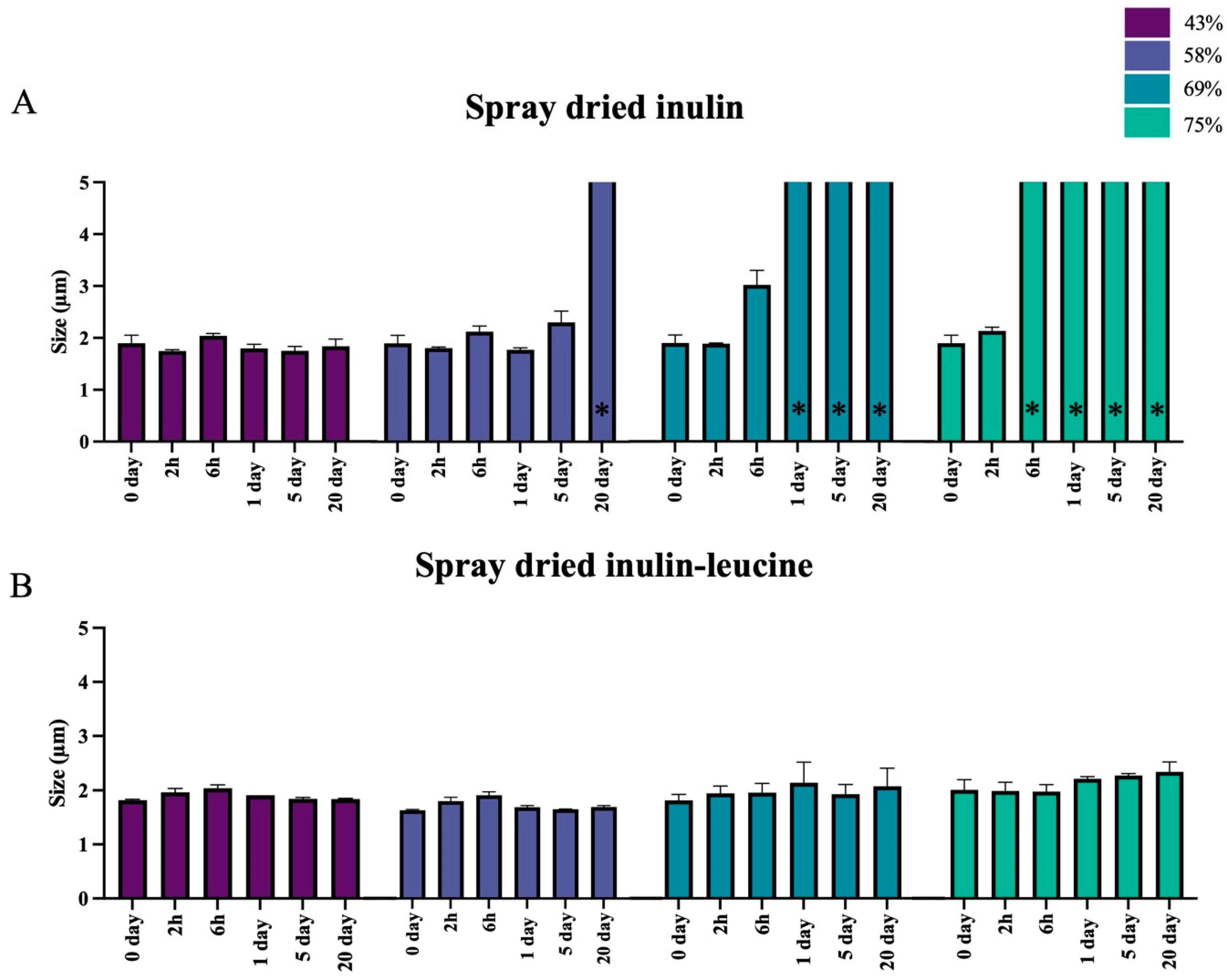

3.2. Leucine Protects Spray Dried Inulin Against Irreversible Moisture Induced Aggregation

To assess the protective effect of leucine against irreversible moisture-induced aggregation, inulin was spray-dried with and without 4 wt-% leucine and stored at 43%, 58%, 69%, and 75% RH at 20 ± 2 °C. Directly upon spray drying, the primary particle size of the spray dried inulin and inulin-leucine formulation were similar (

Figure 2A, B). This indicates that leucine does not influence the particle size of spray dried inulin. Upon storage for 2 hours, 6 hours, 1 day, 5 days and 20 days the primary particle size was examined. Inulin-only powders showed irreversible particle aggregation and viscous flow at high RH levels (

Figure 2A and

Figure S3). At 58% RH (after 20 days), 69% RH (from day 1 onwards), and 75% RH (from 6 hours onwards), laser diffraction measurements could not be performed for these inulin-only powders because the dry powder particles showed viscous flow preventing the generation of a dispersed flowable sample. Therefore, particle sizes > 5 µm are shown in

Figure 2A to indicate irreversible particle aggregation. In contrast, the primary particle size of leucine-containing formulations remained unchanged for up to 20 days across all RH conditions (

Figure 2B). SEM images showed that the spray dried particles of both formulations have a spherical somewhat raisin-like structure (

Figure 3). Satellite particles adhere to the spray dried leucine. For spray dried inulin stored at 69% and 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C no SEM picture could be taken, since these particles completely fused by viscous flow (

Figure S3). These findings demonstrate that leucine effectively protects spray-dried inulin powders from moisture-induced irreversible aggregation. The extent and speed of irreversible aggregation increased with increasing RH in the absence of leucine, underscoring the importance of leucine as a moisture-protective excipient for maintaining the physical stability and dispersibility of spray-dried dry powder formulations during storage.

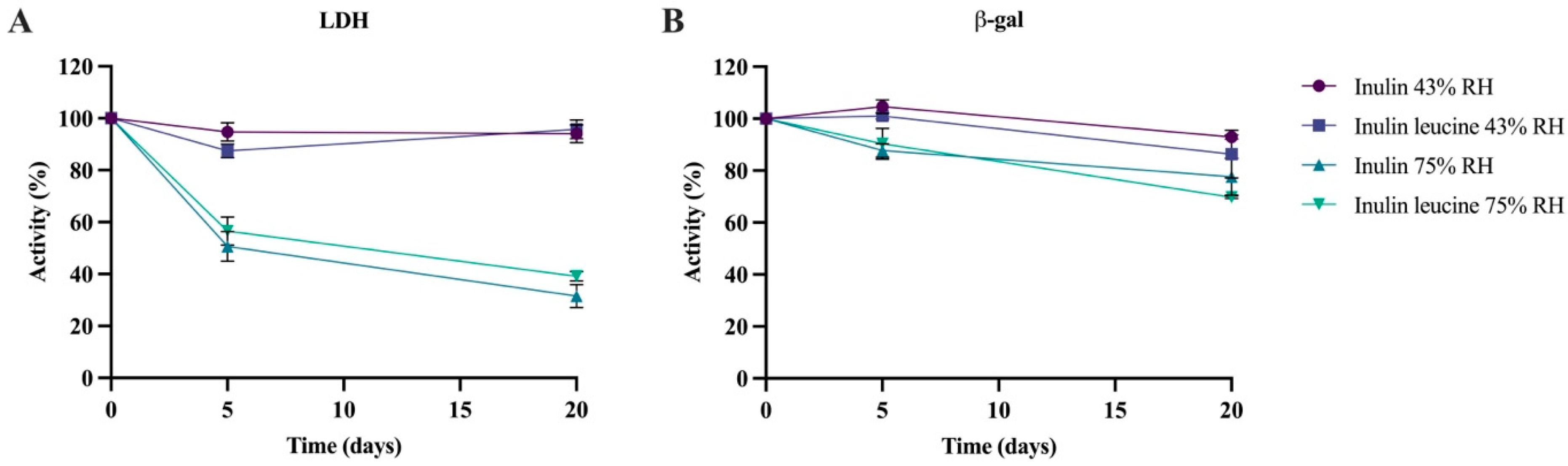

3.3. Protein Activity is not Influenced by the Addition of Leucine

Leucine protects spray-dried inulin particles from irreversible moisture-induced aggregation, thereby enhancing their physical stability at high RH. While leucine preserves external particle morphology, the amorphous inulin core remains susceptible to water-induced plasticization. Plasticization lowers the Tg, and once the Tg drops below room temperature, the capacity of inulin to stabilize proteins through vitrification is compromised. To address this issue, we investigated whether the incorporation of leucine could affect the stability of proteins that rely on either vitrification or water replacement as their primary stabilization mechanism. To investigate this, we examined two model proteins with distinct stabilization mechanisms: LDH and β-gal. The formulations were stored at 43% RH, where the Tg was above storage temperature (20 ± 2 °C), and at 75% RH, where the Tg falls below the storage temperature (20 ± 2 °C).

LDH and β-gal were spray dried with either inulin alone or inulin containing 4 wt-% leucine and subsequently stored at 43% and 75% RH at 20 ± 2 °C for 5 days and 20 days. Immediately after spray drying, enzymatic activity remained above 86% for all formulations. To facilitate comparison, all subsequent storage stability data were normalized to the initial activity values. For LDH, activity was well maintained at 43% RH throughout the 20-day storage period, and no notable differences were observed between inulin-only and inulin–leucine formulations (

Figure 4A). At 75% RH, however, LDH activity decreased significantly over time. In the inulin-only formulation, activity dropped to 50.6 ± 5.7% after 5 days and further declined to 31.5 ± 4.4% after 20 days. A similar pattern was seen for the inulin–leucine formulation, with activity reduced to 56.5 ± 5.4% after 5 days and to 39.1 ± 1.8% after 20 days of storage (

Figure 4A).

Similar to LDH, β-gal remained stable at 43% RH and 20 ± 2 °C, up to 20 days of storage when spray-dried with inulin alone (

Figure 4B). For the inulin–leucine formulation, activity was unchanged after 5 days, but a small yet significant decline was observed after 20 days. Nevertheless, 86.4 ± 9.2% of β-gal activity was retained after 20 days of storage at 43% RH of the inulin–leucine formulation. At 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C, both the inulin and inulin–leucine formulations showed a small but significant decline in β-gal activity after 5 and 20 days of storage. After 5 days, 87.8 ± 2.6% and 90.4 ± 6.0% of the initial activity were retained for the inulin and inulin–leucine formulations, respectively. After 20 days, 77.7 ± 7.1% and 69.7% ± 0.5% of activity were maintained for the inulin and inulin–leucine formulations, respectively. All in all, β-gal activity was largely preserved across both humidity levels and formulations, with only modest activity reductions during storage. Overall, these findings demonstrate that leucine does not inhibit moisture uptake in the amorphous inulin core. At 43% RH and 20 ± 2 °C, where the Tg remains above the storage temperature, inulin retains its amorphous state and vitrification is maintained, independent of the presence of leucine. In contrast, at 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C the Tg falls below the storage temperature, resulting in the loss of vitrification, a process that leucine cannot prevent. Consequently, only biologics that do not depend on vitrification for stabilization can remain enzymatically stable under humid storage conditions when spray-dried with inulin, irrespective of the presence of leucine.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of leucine in mitigating irreversible moisture-induced aggregation in spray-dried inulin particles and evaluated the influence of leucine on the protein stability enhancing effect of inulin using the model proteins LDH and β-gal. Initially, the physicochemical properties of the spray-dried inulin and inulin–leucine formulations were characterized. Interestingly, the initial physicochemical properties of the spray-dried inulin and inulin–leucine formulations appeared to be comparable. Particle size analysis, DVS and TGA revealed similar size and moisture uptake profiles, also XRPD patterns showed no significant differences between the two formulations. This observation is noteworthy given that previous studies have reported that the incorporation of leucine often influences the water sorption behavior and crystallinity of spray-dried powders. However, those studies typically employed higher leucine concentrations, frequently 20% w/w or more. For example, with spray-dried formulations of trehalose, salbutamol or disodium cromoglycate with varying leucine concentrations it was shown that increasing the leucine content reduced water uptake and increased the overall crystalline fraction in the spray dried formulations[

8,

14,

18]. This effect is consistent with the effect caused by leucine’s hydrophobic nature, which limits water absorption. Li et al. investigated the effects of lower leucine concentrations (2 wt-% and 5 wt-%) resembling the leucine concentration used in this study (4 wt-%) and found, similar to our results, that such low levels of leucine did not significantly alter moisture uptake or the crystallinity of the spray dried powders[

8,

14]. These findings collectively suggest that leucine, when used at low concentrations, does not markedly affect the physicochemical properties of spray-dried amorphous formulations.

Despite the limited influence of leucine on the physicochemical properties of spray dried inulin, leucine conferred clear protection against irreversible moisture-induced aggregation. The inulin–leucine formulation did not exhibit irreversible aggregation when stored at 43%, 58%, 69%, or 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C, whereas the inulin-only formulation irreversibly aggregated extensively at higher RH levels. This protective effect of leucine is particularly relevant because the amorphous inulin core remained highly susceptible to water-induced plasticization even with leucine. Water is a well-known plasticizer for amorphous materials and can significantly reduce the Tg, even at low levels of moisture uptake[

25]. Disaccharides such as sucrose and trehalose are especially sensitive to this effect. The Tg of sucrose and trehalose decreases to below 20 ± 2 °C even at relatively low RH, limiting their ability to stabilize biologics under humid conditions[

6]. Inulin, in contrast, has a much higher Tg, which enables it to remain in the glassy state at moderate RH and 20 ± 2 °C. However, previous studies demonstrated that the Tg of amorphous inulin also decreases progressively with increasing RH[

9]. Our findings confirm this behavior: the Tg of spray-dried inulin with or without leucine decreased notably when stored at 43% and 58% RH at 20 ± 2 °C. At higher RH levels (69% and 75%), the Tg of inulin–leucine formulations could not be reliably determined, as water plasticization resulted in broad, poorly defined transitions. Moreover, for the inulin-only formulation showed viscous flow within one day of storage at 69% and 75% RH levels and 20 ± 2 °C, preventing DSC measurements altogether. These observations align with the work of Ronkart et al., who showed that inulin has a high Tg and can withstand moisture to a high extent, it can still undergo physical instability under high humid conditions[

26].

The protective effect of leucine against irreversible moisture-induced particle aggregation can be explained by its surface-accumulation behavior during spray drying. Laser diffraction analysis confirmed that the addition of 4 wt-% leucine to spray-dried inulin preserved the primary particle size after storage at high RHs and 20 ± 2 °C for up to 20 days, indicating reduced irreversible moisture-induced aggregation and improved physical stability of the powder. When co-formulated with inulin, leucine orients preferentially at the air–liquid interface. This is due to its amphiphilic structure, with hydrophilic amino and carboxyl groups and a hydrophobic isobutyl side chain[

18,

27]. During spray drying, the hydrophilic moieties orient toward the droplet interior, whereas the hydrophobic isobutyl side chain aligns outwards toward the air interface. Rapid water evaporation drives leucine accumulation at this interface, where its local concentration exceeds its solubility limit and leads to precipitation[

11]. In contrast, the more soluble inulin remains uniformly distributed within the droplet core. This interfacial alignment of leucine promotes the formation of a leucine-enriched shell that acts as a moisture barrier after drying. Collectively, this explains leucine’s well-established role as a dispersibility enhancer and moisture protector in spray-dried formulations[

10,

11].

While leucine effectively limits irreversible moisture-induced aggregation, it does not prevent plasticization of the amorphous inulin core. To assess whether spray dried inulin-leucine dry powder formulations could still confer protection to an encapsulated protein at high humidity, protein stability of two model proteins with different stabilization mechanisms was investigated. At 43% RH, where the Tg of the inulin matrix was above the storage temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and thus in the glassy state, both LDH and β-gal remained stable. At 75% RH, however, the Tg dropped below storage temperature (20 ± 2 °C), leading to a glass to rubber transition of the inulin core and in an increased translational molecular mobility. This resulted in a pronounced loss of LDH activity. Demonstrating that vitrification is essential for LDH stabilization. In contrast, β-gal retained activity even at 75% RH and 20 ± 2 °C. Although the Tg of inulin dropped below 20 ± 2 °C at 75% RH, increasing molecular mobility, β-gal remained stable. This behavior is consistent with the water replacement mechanism, where hydroxyl groups of the sugar matrix form hydrogen bonds with the protein during drying, preserving the native structure of β-gal independently of the Tg[

23]. These findings agree with Nguyen et al., who freeze-dried LDH and β-gal with arginine-pullulan combinations. They demonstrated that LDH is more dependent on vitrification than β-gal, as LDH degradation accelerates upon moisture uptake by the amorphous matrix, which increases molecular mobility and thereby compromises stabilization through vitrification. In contrast, β-gal activity was hardly affected by moisture uptake, indicating a greater reliance on water replacement[

22]. In our study, a similar distinction was observed for LDH and β-gal spray-dried with inulin, with or without leucine. Together, these results highlight that proteins can be stabilized through distinct stabilizing mechanisms, i.e. vitrification or water replacement, across both freeze-drying and spray-drying processes with different stabilizers. Furthermore, it can be concluded that while leucine reduces irreversible moisture-induced aggregation and thereby preserves the physical integrity of spray-dried powders, it does not prevent degradation of proteins that rely on vitrification for stabilization.

Overall, our study highlights the importance of tailoring stabilization strategies to the specific needs of individual proteins in spray-dried formulations. As different proteins rely on distinct mechanisms for maintaining stability, such as vitrification or water replacement, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be effective. Future work should focus on systematically investigating combinations of sugars and amino acids to optimize both physical and biochemical stability across a range of environmental conditions. In this context, leucine emerges as a promising excipient due to its dual role in enhancing powder flowability and protecting against irreversible moisture-induced aggregation, particularly relevant for formulations intended for use in hot and humid climates. To further refine stabilization approaches, the application of Design of Experiments (DoE) could provide a structured framework for identifying optimal excipient compositions and storage conditions tailored to specific protein profiles. This strategy would support the development of robust, inhalable protein therapeutics with improved shelf-life and global applicability.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we showed that the presence of 4% (w/w) of leucine did not substantially alter the physicochemical properties of spray-dried inulin, but it does effectively prevent moisture-induced irreversible aggregation of spray dried inulin dry powder particles. However, leucine does not inhibit moisture uptake within the amorphous inulin core at high humidity (>58% RH). As a result, proteins that rely on vitrification by a sugar glass for stability, such as LDH, cannot be effectively stabilized by inulin and leucine under high RH. In contrast, proteins such as β-gal, stabilized via water replacement mechanisms, retain their activity when spray dried with inulin with or without leucine, even when stored above the Tg. This study highlights that leucine primarily protects dry powder particles from humidity-driven physical destabilization, rather than directly stabilizing proteins. This mechanistic insight challenges the prevailing view of leucine as a general protein stabilizer and instead highlights its unique role in safeguarding powder integrity under ambient conditions. By reducing irreversible moisture-induced aggregation at normal RH levels, leucine enables spray-dried inulin-based powders to be stored and handled outside of (ultra-)dry environments. This positions leucine as a key excipient for developing stable, inhalable formulations that are easier to distribute and more practical to use globally, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1. Typical example of DSC measurements of spray dried inulin. Figure S2. Typical example of DSC measurements of spray dried inulin with 4 wt-% leucine. Figure S3. Spray dried inulin and inulin-leucine stored at 43%, 58%, 69% and 75% RH for 1 day. Figure S4. DVS measurement of spray dried inulin and spray dried inulin with 4 wt-% leucine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Evalyne M Jansen, Luke van der Koog and Wouter L.J. Hinrichs; Data curation, Evalyne M Jansen, Henderik W Frijlink and Wouter L.J. Hinrichs; Formal analysis, Evalyne M Jansen; Funding acquisition, Henderik W Frijlink; Investigation, Evalyne M Jansen and Wouter L.J. Hinrichs; Methodology, Evalyne M Jansen, Luke van der Koog and Wouter L.J. Hinrichs; Project administration, Evalyne M Jansen; Resources, Henderik W Frijlink; Software, Evalyne M Jansen; Supervision, Henderik W Frijlink and Wouter L.J. Hinrichs; Validation, Evalyne M Jansen and Wouter L.J. Hinrichs; Visualization, Evalyne M Jansen and Henderik W Frijlink; Writing – original draft, Evalyne M Jansen; Writing – review & editing, Evalyne M Jansen, Luke van der Koog, Henderik W Frijlink and Wouter L.J. Hinrichs.

Funding

this research received no funding.

Acknowledgments

The figures contained in this article were partially created with BioRender.com. During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

LK and HWF are co-founders and shareholders of the University of Groningen spin-off MimeCure B.V. This company had no role in the design of the study; analysis, data collection, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript and the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| β-gal |

β-Galactosidase |

| DPI |

Dry powder inhaler |

| DVS |

Dynamic vapor sorption |

| FPF |

Fine particle fraction |

| LDH |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LD |

Laser diffraction |

| DSC |

Differential scanning calorimetry |

| RH |

Relative humidity |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| Tg |

Glass transition temperature |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

References

- Dieplinger, J.; Isabel Afonso Urich, A.; Mohsenzada, N.; Pinto, J.T.; Dekner, M.; Paudel, A. Influence of L-leucine content on the aerosolization stability of spray-dried protein dry powder inhalation (DPI). Int J Pharm 2024, 666, 124822. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.M.; van der Koog, L.; Elferink, R.A.B.; Rafie, K.; Nagelkerke, A.; Gosens, R.; Frijlink, H.W.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Stabilized Extracellular Vesicle Formulations for Inhalable Dry Powder Development. Small 2025, e2411096. [CrossRef]

- Poozesh, S.; Connaughton, P.; Sides, S.; Lechuga-Ballesteros, D.; Patel, S.M.; Manikwar, P. Spray drying process challenges and considerations for inhaled biologics. J Pharm Sci 2025, 114, 766-781. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ling, J.; Li, M.; Su, Y.; Arte, K.S.; Mutukuri, T.T.; Taylor, L.S.; Munson, E.J.; Topp, E.M.; Zhou, Q.T. Understanding the Impact of Protein-Excipient Interactions on Physical Stability of Spray-Dried Protein Solids. Mol Pharm 2021, 18, 2657-2668. [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, W.L.J.; Sanders, N.N.; De Smedt, S.C.; Demeester, J.; Frijlink, H.W. Inulin is a promising cryo- and lyoprotectant for PEGylated lipoplexes. J Control Release 2005, 103, 465-479. [CrossRef]

- Van Drooge, D.J.; Hinrichs, W.L.J.; Frijlink, H.W. Incorporation of lipophilic drugs in sugar glasses by lyophilization using a mixture of water and tertiary butyl alcohol as solvent. J Pharm Sci 2004, 93, 713-725. [CrossRef]

- Mensink, M.A.; Frijlink, H.W.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Inulin, a flexible oligosaccharide I: Review of its physicochemical characteristics. Carbohydr Polym 2015, 130, 405-419. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, S.; Parumasivam, T.; Denman, J.A.; Gengenbach, T.; Tang, P.; Mao, S.; Chan, H.K. L-Leucine as an excipient against moisture on in vitro aerosolization performances of highly hygroscopic spray-dried powders. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2016, 102, 132-141. [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, W.L.J., Prinsen, M.G., Frijlink, H.W. Inulin glasses for the stabilization of therapeutic proteins. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2001, 215, 163-174.

- Ordoubadi, M.; Gregson, F.K.A.; Wang, H.; Nicholas, M.; Gracin, S.; Lechuga-Ballesteros, D.; Reid, J.P.; Finlay, W.H.; Vehring, R. On the particle formation of leucine in spray drying of inhalable microparticles. Int J Pharm 2021, 592, 120102. [CrossRef]

- Vehring, R. Pharmaceutical Particle Engineering via Spray Drying. Pharmaceutical Research 2007, 25, 999-1022. [CrossRef]

- Raula, J.; Thielmann, F.; Kansikas, J.; Hietala, S.; Annala, M.; Seppälä, J.; Lähde, A.; Kauppinen, E.I. Investigations on the humidity-induced transformations of salbutamol sulphate particles coated with L-leucine. Pharm Res 2008, 25, 2250-2261. [CrossRef]

- Mangal, S.; Meiser, F.; Tan, G.; Gengenbach, T.; Denman, J.; Rowles, M.R.; Larson, I.; Morton, D.A. Relationship between surface concentration of L-leucine and bulk powder properties in spray dried formulations. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2015, 94, 160-169. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Leung, S.S.Y.; Gengenbach, T.; Yu, J.; Gao, G.F.; Tang, P.; Zhou, Q.T.; Chan, H.K. Investigation of L-leucine in reducing the moisture-induced deterioration of spray-dried salbutamol sulfate power for inhalation. Int J Pharm 2017, 530, 30-39. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, G.; Cai, S.; Jing, H.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; et al. Moisture-Resistant Co-Spray-Dried Netilmicin with l-Leucine as Dry Powder Inhalation for the Treatment of Respiratory Infections. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; van de Weert, M.; Bjerregaard, S.; Rantanen, J.; Yang, M. Leucine as a Moisture-Protective Excipient in Spray-Dried Protein/Trehalose Formulation. J Pharm Sci 2024, 113, 2764-2774. [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.Y.K.; Li, M.; Chow, M.Y.T.; Ke, W.R.; Tai, W.; Chan, H.K. A dual action of D-amino acids on anti-biofilm activity and moisture-protection of inhalable ciprofloxacin powders. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2022, 173, 132-140. [CrossRef]

- Mah, P.T.; O'Connell, P.; Focaroli, S.; Lundy, R.; O'Mahony, T.F.; Hastedt, J.E.; Gitlin, I.; Oscarson, S.; Fahy, J.V.; Healy, A.M. The use of hydrophobic amino acids in protecting spray dried trehalose formulations against moisture-induced changes. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2019, 144, 139-153. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Vehring, R. Leucine enhances the dispersibility of trehalose-containing spray-dried powders on exposure to a high-humidity environment. Int J Pharm 2021, 601, 120561. [CrossRef]

- Arte, K.S.; Tower, C.W.; Moon, C.; Patil, C.D.; Huang, Y.; Munson, E.J.; Zhou, Q.T.; Qu, L.L. Understanding the impact of L-leucine on physical stability and aerosolization of spray-dried protein powder formulations containing trehalose. Int J Pharm 2025, 677, 125636. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Yue, X.; Huang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; et al. Co-spray-dried poly-L-lysine with L-leucine as dry powder inhalations for the treatment of pulmonary infection: Moisture-resistance and desirable aerosolization performance. Int J Pharm 2022, 624, 122011. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.T.; Zillen, D.; Lasorsa, A.; van der Wel, P.C.A.; Frijlink, H.W.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Combinations of arginine and pullulan reveal the selective effect of stabilization mechanisms on different lyophilized proteins. Int J Pharm 2024, 654, 123938. [CrossRef]

- Mensink, M.A.; Frijlink, H.W.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. How sugars protect proteins in the solid state and during drying (review): Mechanisms of stabilization in relation to stress conditions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2017, 114, 288-295. [CrossRef]

- Tonnis, W.F.; Mensink, M.A.; de Jager, A.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K.; Frijlink, H.W.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Size and molecular flexibility of sugars determine the storage stability of freeze-dried proteins. Mol Pharm 2015, 12, 684-694. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, B.C.; Zografi, G. The Relationship Between the Glass Transition Temperature and the Water Content of Amorphous Pharmaceutical Solids. Pharmaceutical Research 1994, 11, 471-477.

- Ronkart, S.N.; Paquot, M.; Blecker, C.S.; Fougnies, C.; Doran, L.; Lambrechts, J.C.; Norberg, B.; Deroanne, C. Impact of the Crystallinity on the Physical Properties of Inulin during Water Sorption. Food Biophysics 2008, 4, 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chan, H.K.; Gengenbach, T.; Denman, J.A. Protection of hydrophobic amino acids against moisture-induced deterioration in the aerosolization performance of highly hygroscopic spray-dried powders. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2017, 119, 224-234. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).