Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

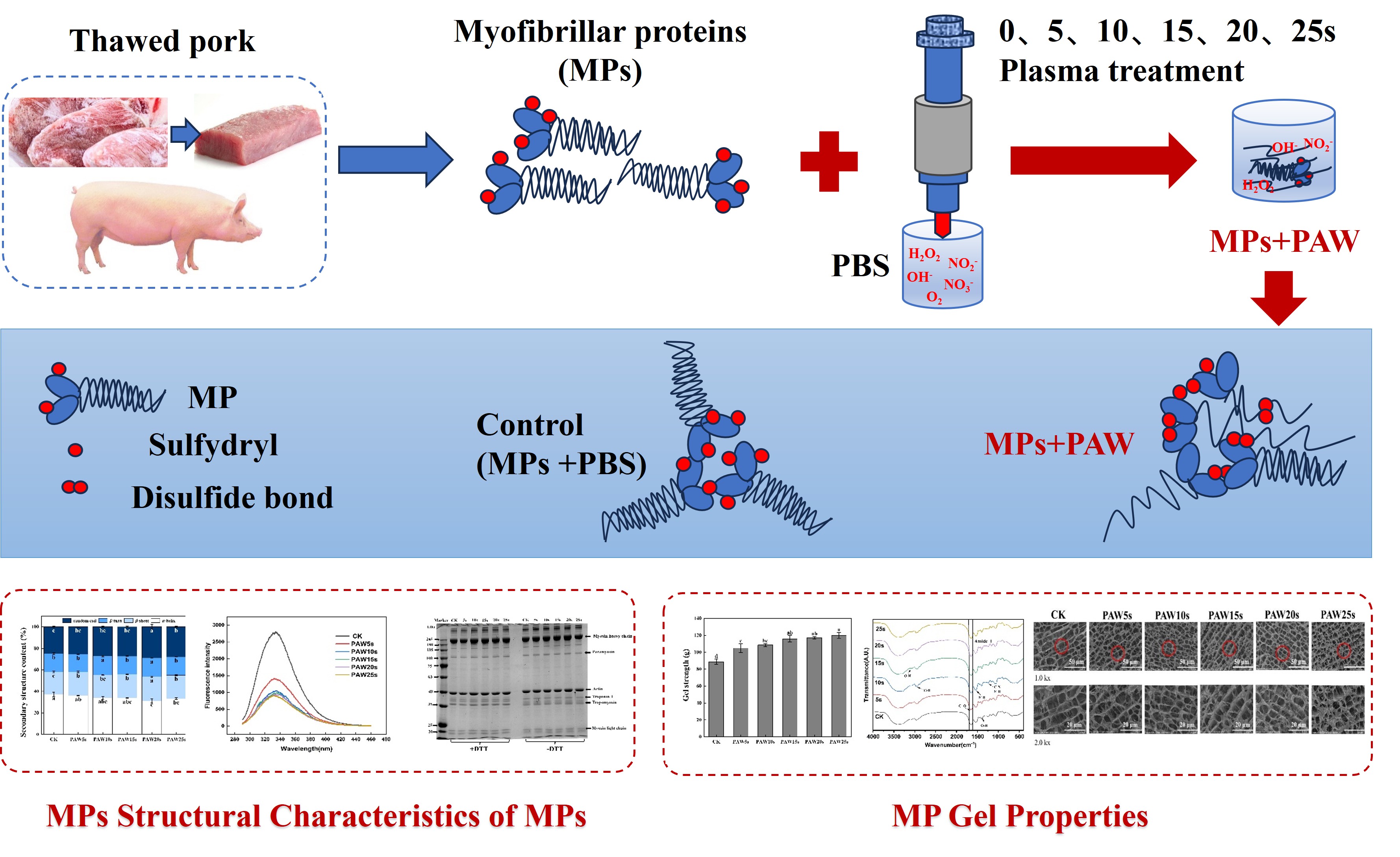

Abstract

In this study, myofibrillar proteins (MPs) of thawed pork were treated with plasma-activated water (PAW) for diverse durations (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 s) to investigate whether the function of MPs improved by PAW and the corresponding regulatory mechanism. The results found that PAW treatments increased the surface hydrophobicity, altered secondary and tertiary structure of MPs. The α-helix content of MPs treated by PAW reduced from 37.3% to 31.25%. In PAW25s group, the oxidation of MPs significantly raised reflected by the higher carbonyl content and lower total sulfhydryl content compared to other groups (P<0.05). Furthermore, PAW treatments increased the whiteness, improved the strength, immobilized water contents, resilience, chewiness, and adhesiveness of MP gels. The observation of intermolecular forces and microstructure of MP gels presented the increase in ionic bonding, disulfide bonding, and hydrophobic interactions, but decrease in hydrogen bonding in MP gels with PAW treatments, leading to more homogeneous and denser gel structures compared to control group. In conclusion, PAW treatment for a short duration significantly fixed and enhanced the function of MPs extracted from thawed pork, and to some extent, improved the processing quality of MPs of thawed pork.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of PAW

2.3. Extraction of MPs and PAW Treatment

2.4. Surface Hydrophobicity Measurement of Carbonyl Value

2.5. Ultraviolet Spectroscopy

2.6. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.7. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.8. Total Sulfhydryl Content

2.9. Carbonyl Content

2.10. Secondary Structure

2.11. Preparation of MP Gels

2.12. Color and Whiteness

2.13. Gel Strength

2.14. Textural Properties

2.15. Moisture Distribution

2.16. Secondary Structure

2.17. Molecular Forces

2.18. Microstructure

2.19. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

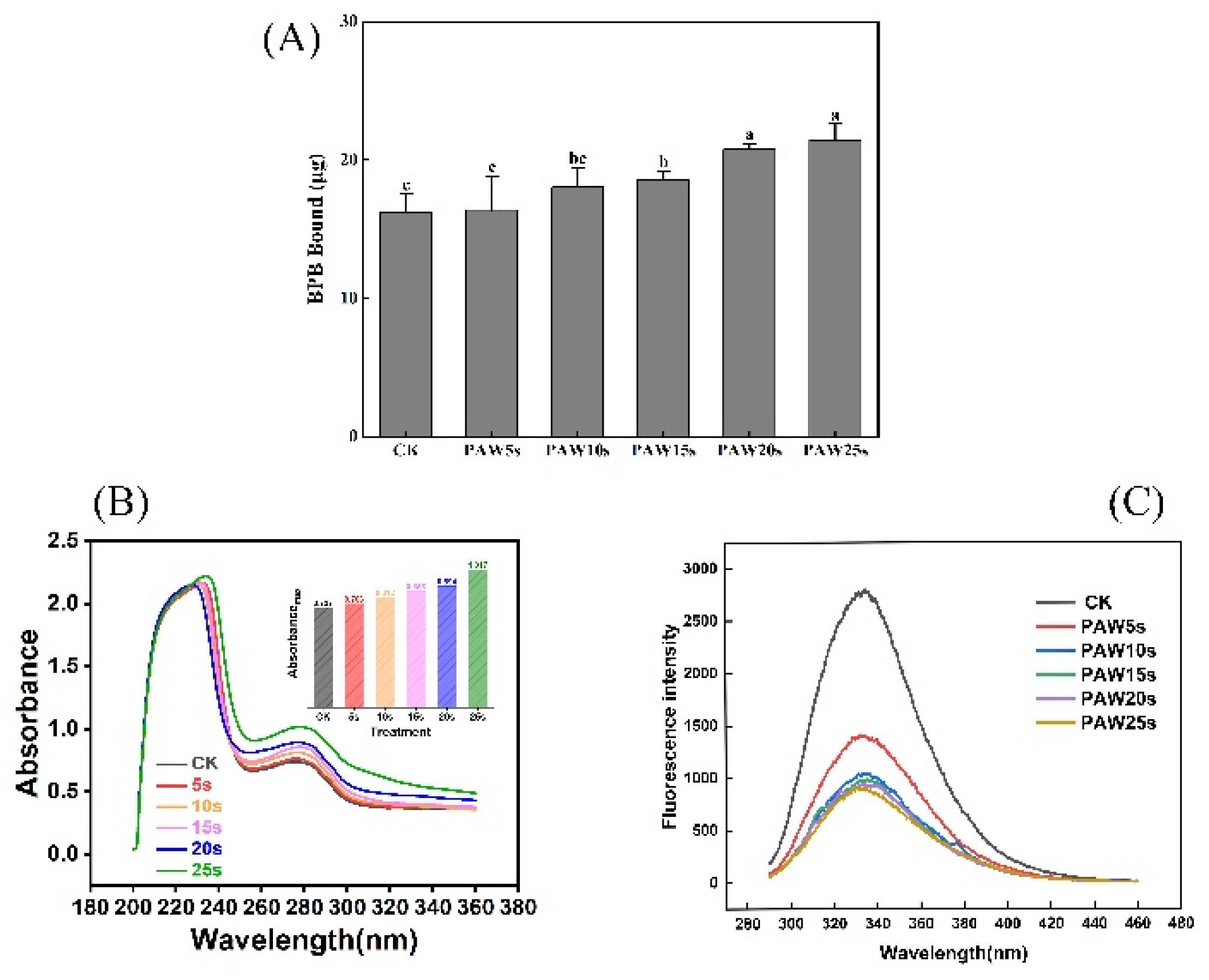

3.1. Surface Hydrophobicity

3.2. Ultraviolet Spectroscopy

3.3. Intrinsic Fluorescence Spectroscopy

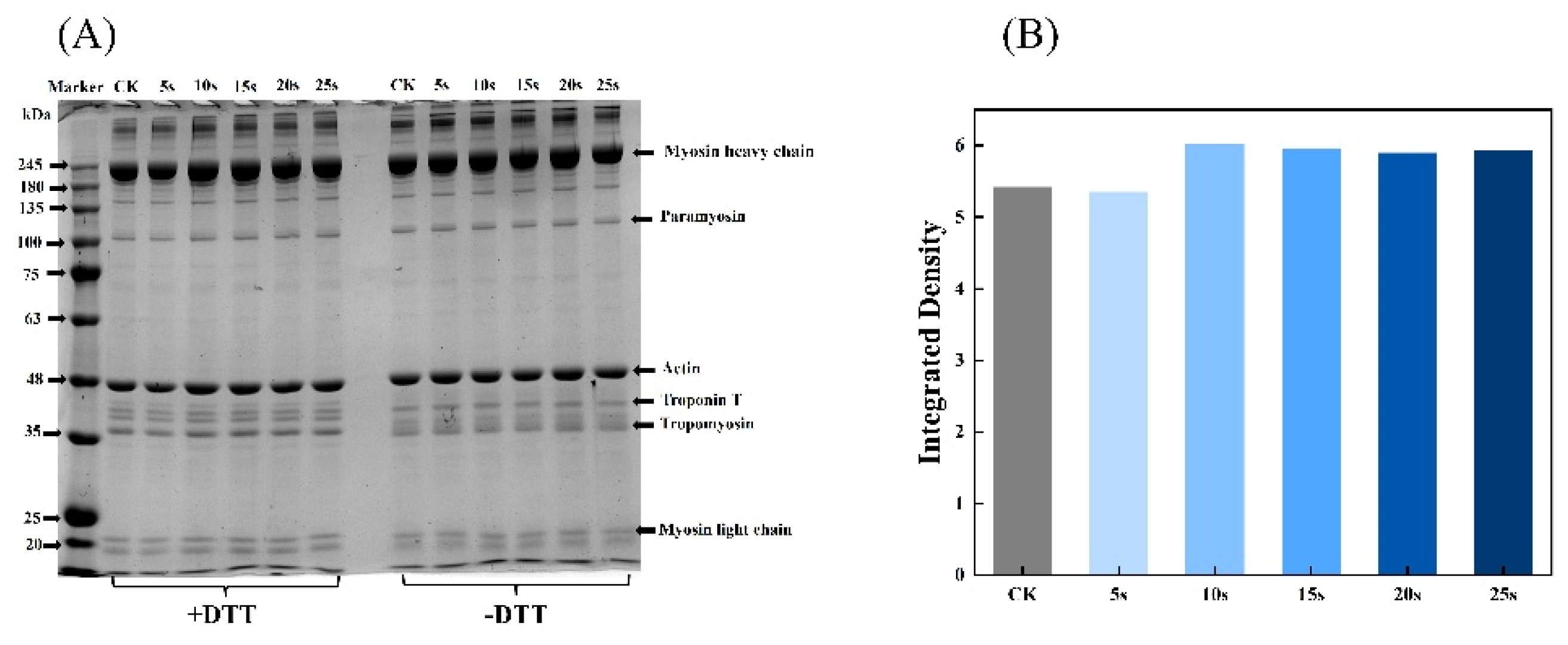

3.4. SDS-PAGE

3.5. Total Sulfhydryl Content

3.6. Carbonyl Content

3.7. Secondary Structure

3.8. Color and Whiteness of MP Gels

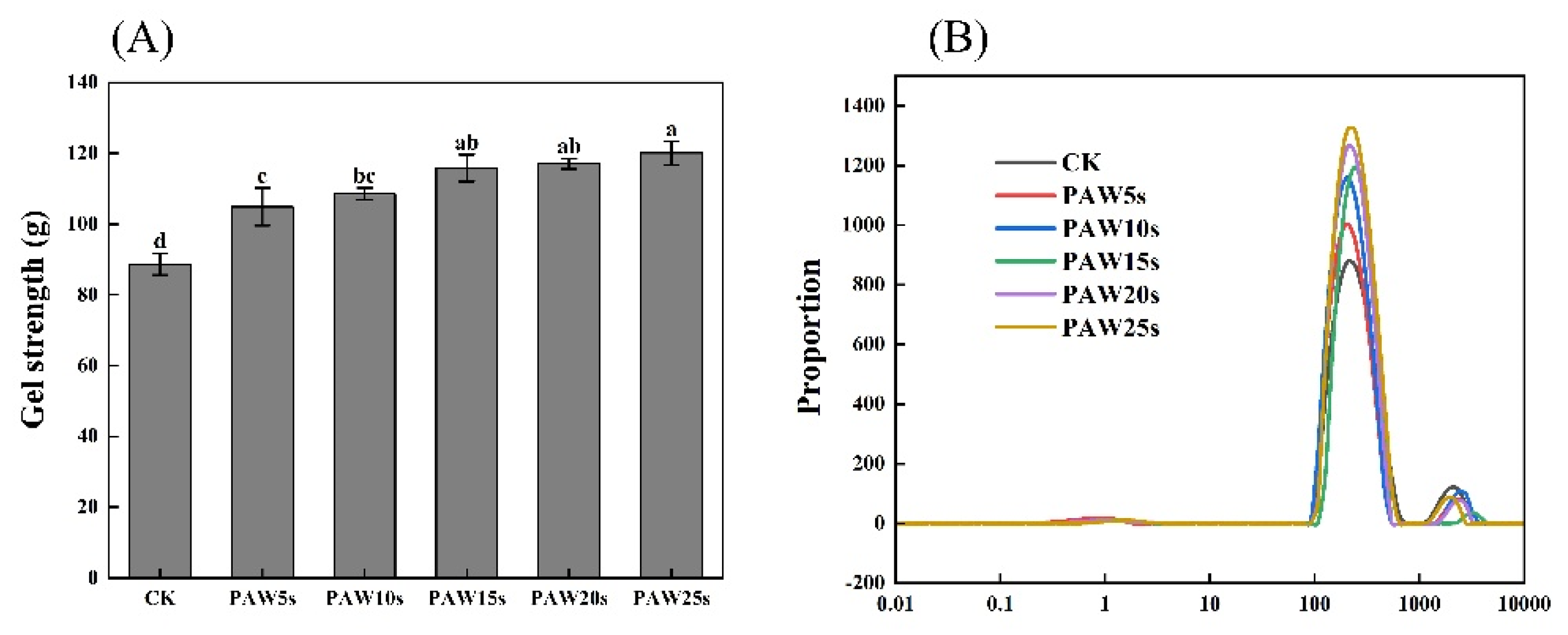

3.9. Gel Strength

3.10. Moisture Distribution

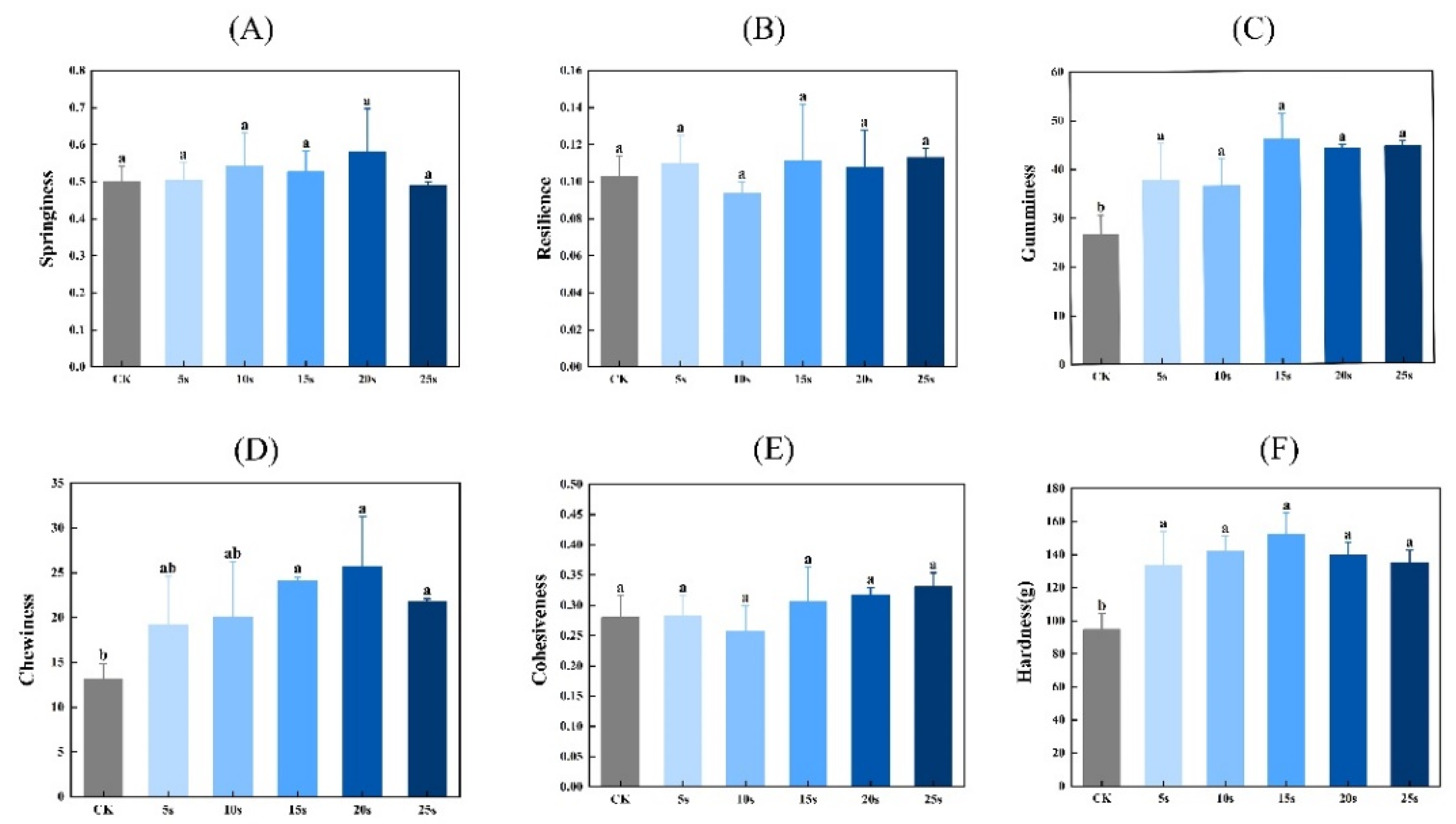

3.11. Textural Properties

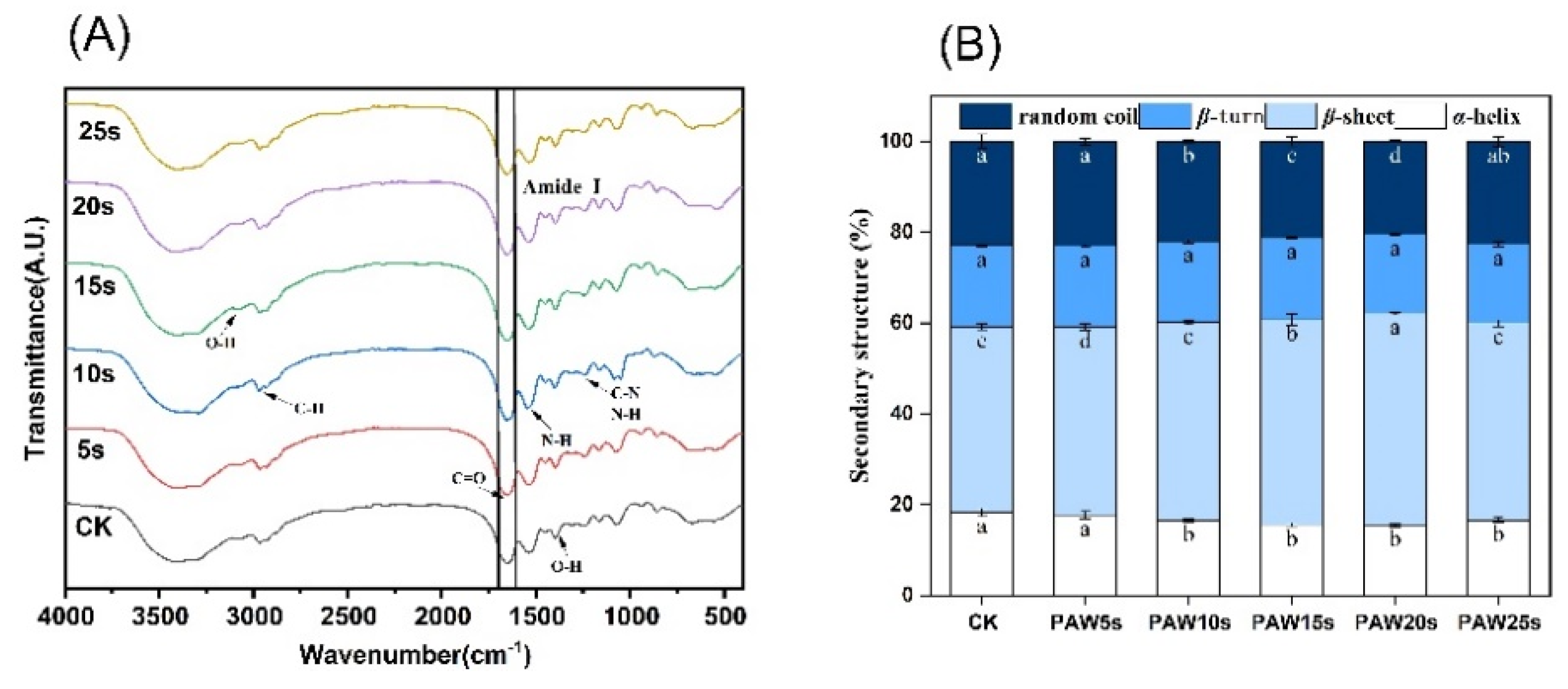

3.12. FTIR

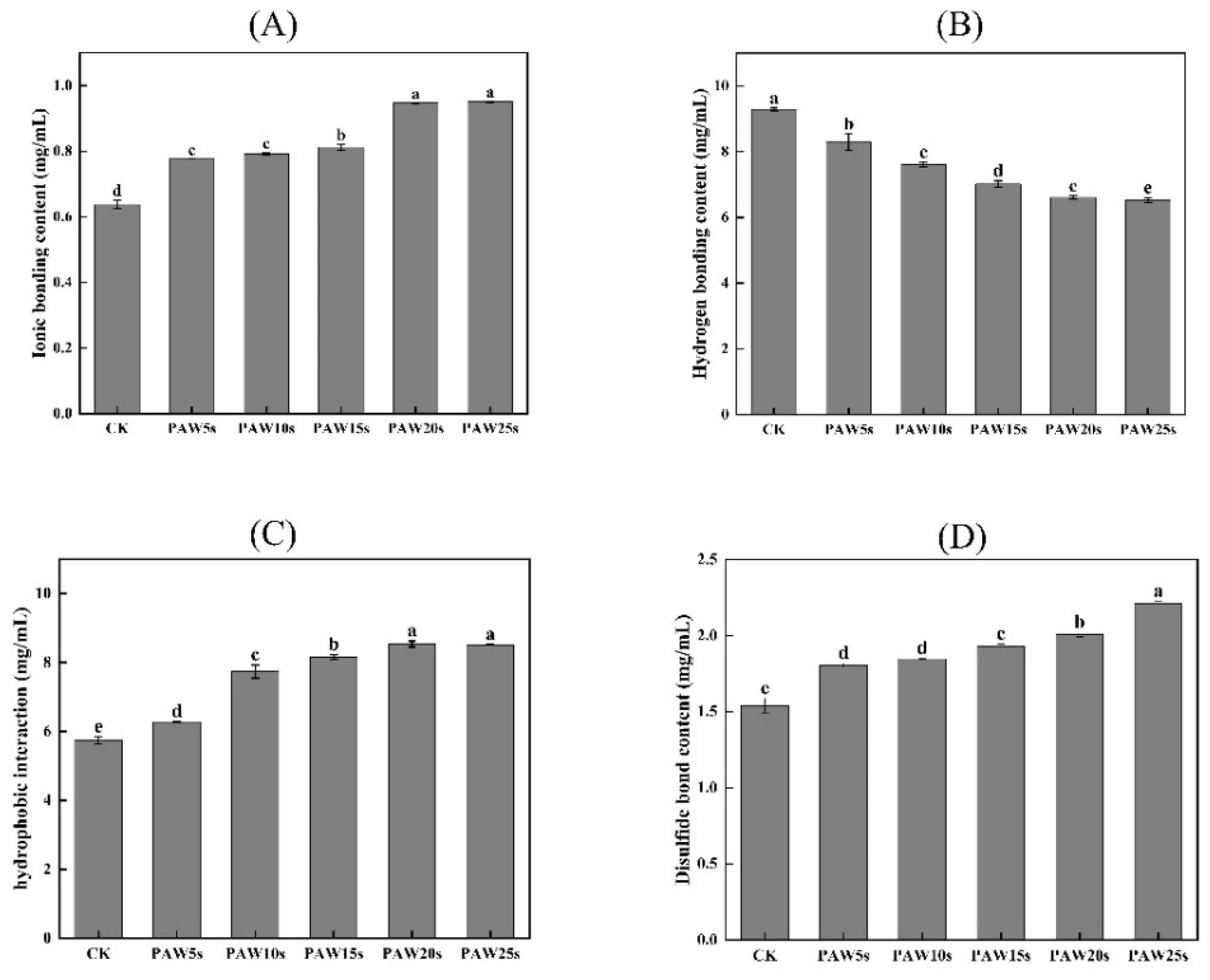

3.13. Molecular Forces

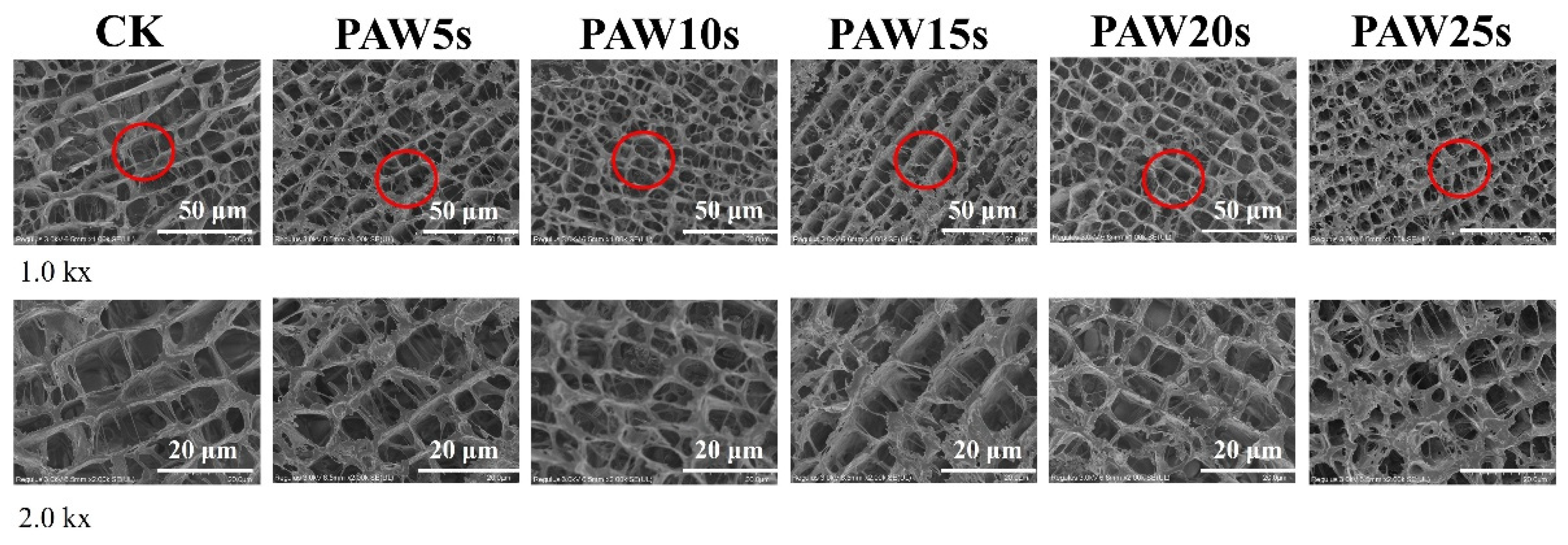

3.14. Microstructure

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medic H.; Djurkin Kusec I.; Pleadin J; Kozacinski, L.; Njari, B.; Hengl, B.; Kusec, G. The Impact of Frozen Storage Duration on Physical, Chemical and Microbiological Properties of Pork. Meat Science, 2018, 140, 119-127. [CrossRef]

- Kim H. W.; Kim J. H.; Seo J. K.; Setyabrata, D.; Kim, Y. H. B. Effects of Aging/freezing Sequence and Freezing Rate on Meat Quality and Oxidative Stability of Pork Loins. Meat Science, 2018, 139, 162-170. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, Y. H.; Ma, F.; Li, K.; Zhou, H.; Chen, C. G. (2021). Combination Treatment of High-pressure and CaCl2 for the Reduction of Sodium Content in Chicken Meat Batters: Effects on Physicochemical Properties and Sensory Characteristics. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2021, 56(12), 6322-6334. [CrossRef]

- Chaijan, M.; Chaijan, S.; Panya, A.; Nisoa, M.; Cheong, L. Z.; Panpipat, W. High Hydrogen Peroxide Concentration-low Exposure Time of Plasma-activated Water (PAW): A Novel Approach for Shelf-life Extension of Asian Sea Bass (Lates calcarifer) Steak. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2021, 74, 102861. [CrossRef]

- Laurita, R.; Gozzi, G.; Tappi, S.; Capelli, F.; Bisag, A.; Laghi, G.; Gherardi, M.; Cellini, B.; Abouelenein, D.; Vittori, S. Effect of plasma activated water (PAW) on rocket leaves decontamination and nutritional value. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2021, 73, 102805. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Z.; Wang, X.; Shi, T.; Xiong, Z. Y.; Jin, W. A.; Bao, L.; Monto, A. R.; Yuan, L.; Gao, R. C. Mechanism of Plasma-activated Water Promoting the Heat-induced Aggregation of Myofibrillar Protein from Silver Carp (Aristichthys Nobilis). Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2024, 91, 103555. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wang, Y. Y.; Zhuang, H.; Yan, W. J.; Zhang, J. H.; Luo, J. Plasma Activated Water-induced Formation of Compact Chicken Myofibrillar Protein Gel Structures with Intrinsically Antibacterial Activity. Food Chemistry, 2021, 351, 129278. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X. Y.; Liu, D. H.; Xiang, Q. S.; Ahn, J.; Chen, S. G.; Ye, X. Q.; Ding, T. Inactivation Mechanisms of Non-thermal Plasma on Microbes: A Review. Food Control, 2017, 75, 83-91. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M. M.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. J.; Kang, Z. L.; Ma, H. J.; Zhao, S. M.; Jiao, L. X. Low-frequency Alternating Magnetic Field Thawing of Frozen Pork Meat: Effects of Intensity on Quality Properties and Microstructure of Meat and Structure of Myofibrillar Proteins. Meat Science, 2023, 204, 109241. [CrossRef]

- Li, F. F.; Wang, B.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, H. W.; Xia, X. F.; Kong, B. H. Changes in Myofibrillar Protein Gel Quality of Porcine Longissimus Muscle Induced by Its Stuctural Modification under Different Thawing Methods. Meat Science, 2019, 147, 108-115. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Arner, A.; Puolanne, E.; Ertbjerg, P. On the Water-holding of Myofibrils: Effect of Sarcoplasmic Protein Denaturation. Meat Science, 2016, 119, 32-40. [CrossRef]

- Jia, G. L.; Nirasawa, S.; Ji, X. H.; Luo, Y. K.; Liu, H. J. Physicochemical Changes in Myofibrillar Proteins Extracted from Pork Tenderloin Thawed by A High-voltage Electrostatic Field. Food Chemistry, 2018, 240, 910-916. [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Xiong, Z. Y.; Jin, W. G.; Yuan, L.; Sun, Q. C.; Zhang, Y. H.; Li, X. T.; Gao, R. C. Suppression Mechanism of l-Arginine in the Heat-induced Aggregation of Bighead Carp (Aristichthys nobilis) Myosin: The Significance of Ionic Linkage Effects and Hydrogen Bond Effects. Food Hydrocolloids, 2020, 102, 105596. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, J. J.; Li, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. T.; Bai, Y. H. Evaluation of Chickpea Protein Isolate as A Partial Replacement for Phosphate in Pork Meat Batters: Techno-functional Properties and Molecular Characteristic Modifications. Food Chemistry, 2023 404, 134585. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, L. M.; Gao, H. J.; Du, M. T.; Bai, Y. H. Use of Basic Amino Acids to Improve Gel Properties of PSE-like Chicken Meat Proteins Isolated Via Ultrasound-assisted Alkaline Extraction. Journal of Food Science, 2023, 88(12), 5136-5148. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. S.; Wang, X. H.; Yang, H. M.; Lin, R.; Wang, H. T.; Tan, M. Q. Characterization of Moisture Migration of Beef During Refrigeration Storage by Low-field NMR and Its Relationship to Beef Quality. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2020, 100(5), 1940-1948. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. Z.; Zhou, F. B.; Sun, D. W.; Zhao, M. M. Effect of Oxidation on the Emulsifying Properties of Myofibrillar Proteins. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 2013, 6(7), 1703-1712. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z. Y.; Shi, T.; Zhang, W.; Kong, Y. F.; Yuan, L.; Gao, R. C. Improvement of Gel Properties of Low Salt Surimi using Low-dose L-arginine Combined with Oxidized Caffeic Acid. Lwt-Food Science and Technology, 2021, 145, 111303. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F. B.; Zhao, M. M.; Su, G. W.; Cui, C.; Sun, W. Z. Gelation of Salted Myofibrillar Protein under Malondialdehyde-induced Oxidative Stress. Food Hydrocolloids, 2014, 40, 153-162. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. Q.; Yang, C. J.; Bai, R.; Li, Z. W.; Zhang, L. L.; Chen, Y.; Ye, X.; Wang, S. Y.; Jiang, H.; Ding, W. Modifying Duck Myofibrillar Proteins Using Sodium Bicarbonate Under Cold Plasma Treatment: Impact on the Conformation, Emulsification, and Rheological Properties. Food Hydrocolloids, 2024, 150 109682. [CrossRef]

- Inbakumar, S. (2010). Effect of Plasma Treatment on Surface of Protein Fabrics. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2010, 208, 012111: IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiang, Q.; Liu, X.; Ding, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, Y.; Bai, Y. Inactivation of Soybean Trypsin Inhibitor by Dielectric-barrier Discharge (DBD) Plasma. Food chemistry, 2017, 232, 515-522. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Z.; Wang, X.; Shi, T.; Xiong, Z. Y.; Jin, W. A.; Bao, Y. L.; Monto, A. R.; Yuan, L.; Gao, R. C. (2024). Mechanism of Plasma-activated Water Promoting the Heat-induced Aggregation of Myofibrillar Protein from Silver Carp (Aristichthys Nobilis). Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2024, 91, 103555. [CrossRef]

- Bußler, S.; Rumpold, B. A.; Fröhling, A.; Jander, E.; Rawel, H. M.; Schlüter, O. K. Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Processing of Insect Flour from Tenebrio Molitor: Impact on Microbial Load and Quality Attributes in Comparison to Dry Heat Treatment. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2016, 36, 277-286. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; True, A. D.; Chen, J.; Xiong, Y. L. Dual Role (Anti-and Pro-oxidant) of Gallic Acid in Mediating Myofibrillar Protein Gelation and Gel in Vitro Digestion. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2016, 64(15), 3054-3061. [CrossRef]

- Nyaisaba, B. M.; Miao, W. H.; Hatab, S.; Siloam, A.; Chen, M. L.; Deng, S. G. Effects of Cold Atmospheric Plasma on Squid Proteases and Gel Properties of Protein Concentrate from Squid (Argentinus ilex) Mantle. Food Chemistry, 2019, 291, 68-76. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. C.; Kao, M. C.; Chen, C. J.; Jao, C. H.; Hsieh, J. F. Improvement of Enzymatic Cross-linkin of Ovalbumin and Ovotransferrin Induced by Transglutaminase with Heat and Reducing Agent Pretreatment. Food Chemistry, 2023, 409, 135281. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G. Q.; Cheng, W.; Ye, L. X.; Du, X.; Zhou, M.; Lin, R. T.; Geng, S. R.; Chen, M. L.; Corke, H.; Cai, Y. Z. Effects of Konjac Glucomannan on Physicochemical Properties of Myofibrillar Protein and Surimi Gels from Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Food Chemistry, 2009, 116(2), 413-418. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Zhou, X. S.; Zhao, M. M.; Yang, B. Effect of Thermal Treatment on the Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Chicken Proteins. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2009, 10(1), 37-41. [CrossRef]

- Xia, T. L.; Xu, Y. J.; Zhang, Y. L.; Xu, L. A.; Kong, Y. W.; Song, S. X.; Huang, M. Y.; Bai, Y.; Luan, Y.; Han, M. Y.; Zhou, G. H.; Xu, X. L. Effect of Oxidation on the Process of Thermal Gelation of Chicken Breast Myofibrillar Protein. Food Chemistry, 2022, 384. [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M. Protein Carbonyls in Meat Systems: A Review. Meat science, 2011, 89(3), 259-279. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhao, S. M.; Xiong, S. B.; Die, B. J.; Qin, L. H. Role of Secondary Structures in the Gelation of Porcine Myosin at Different pH Values. Meat science, 2008, 80(3), 632-639. [CrossRef]

- Bellissent-Funel, M. C.; Hassanali, A.; Havenith, M.; Henchman, R.; Pohl, P.; Sterpone, F.; van der Spoel, D.; Xu, Y.; Garcia, A. E. Water Determines the Structure and Dynamics of Proteins. Chemical Reviews, 2016, 116(13), 7673-7697. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, Y.; Meng, D.; Wang, D.; Blanchard, C. L.; Zhou, Z. Effect of Atmospheric Cold Plasma on Structure, Activity, and Reversible Assembly of the Phytoferritin. Food Chemistry, 2018, 264, 264, 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Liu, Y. D.; Luo, L. H.; Chen, Y. Y.; Zheng, Y. H.; Ran, G. L.; Liu, D. Y. Screening of Optimal Konjac Glucomannan-Protein Composite Gel Formulations to Mimic the Texture and Appearance of Tripe. Gels, 2024, 10(8), 528. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. B.; Han, Y. R.; Ge, G.; Zhao, M. M.; Sun, W. Z. Partial substitution of NaCl with Chloride Salt Mixtures: Impact on Oxidative Characteristics of Meat Myofibrillar Protein and Their Rheological Properties. Food Hydrocolloids, 2019, 96, 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H. Y.; Luo, K. X.; Fu, R. H.; Lin, X. D.; Feng, A. G. Impact of the Magnetic Field-assisted Freezing on the Moisture Content, Water Migration Degree, Microstructure, Fractal Dimension, and the Quality of the Frozen Tilapia. Food Science & Nutrition, 2022, 10(1), 122-132. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B.; Gao, Z. X. Effects of Malondialdehyde-induced Protein Modification on Water Functionality and Physicochemical State of Fish Myofibrillar Protein Gel. Food Research International, 2016, 86, 131-139. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Y.; Regenstein, J. M.; Zhou, P.; Yang, Y. L. Effects of High Intensity Ultrasound Modification on Physicochemical Property and Water in Myofibrillar Protein Gel. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 2017, 34, 960-967. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Y.; Ren, Y. X.; Zhang, K. S.; Xiong, Y. L. L.; Wang, Q.; Shang, K.; Zhang, D. Site-specific Incorporation of Sodium Tripolyphosphate into Myofibrillar Protein from Mantis Shrimp (Oratosquilla oratoria) Promotes Protein Crosslinking and Gel Network Formation. Food Chemistry, 2020, 312, 126113. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xu, W. M.; Liu, Q.; Zou, Y.; Wang, D. Y.; Zhang, J. H. Dielectric Barrier Discharge Cold Plasma Treatment of Pork Loin: Effects on Muscle Physicochemical Properties and Emulsifying Properties of Pork Myofibrillar Protein. Lwt-Food Science and Technology, 2022, 162, 113484. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Singh, B. R. Identification of Beta-turn and Random Coil Amide III Infrared Bands for Secondary Structure Estimation of Proteins. Biophysical Chemistry, 1999, 80(1), 7-20. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A. S.; Chen, B. Effects of Electric and Magnetic Field on Freezing Characteristics of Gel Model Food. Food Research International, 2023, 166, 112566. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhao, S. C.; Jia, X. W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Kong, B. H. Thermal Gelling Properties and Structural Properties of Myofibrillar Protein Including Thermo-reversible and Thermo-irreversible Curdlan Gels. Food Chemistry, 2020, 311, 126018. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Lv, Y.; Su, Y.; Chang, C.; Gu, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Influence of Konjac Glucomannan on the Emulsion-filled/Non-filled Chicken Gel: Study on Intermolecular Forces, Microstructure and Gelling Properties. Food Hydrocolloids, 2022, 124, 107269. [CrossRef]

- Farouk, M. M.; Wieliczko, K.; Lim, R.; Turnwald, S.; Macdonald, G. A. Cooked sausage Batter Cohesiveness as Affected by Sarcoplasmic Proteins. Meat Science, 2002, 61(1), 85-90. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. W.; Lanier, T. C.; Farkas, B. E. High Pressure Effects on Heat-induced Gelation of Threadfin Bream (Nemipterus spp.) Surimi. Journal of Food Engineering, 2015, 146, 23-27. [CrossRef]

| L* | a* | b* | W | |

| CK | 76.75±1.26d | -2.45±0.17c | -3.52±0.64c | 76.35±1.32d |

| PAW5s | 80.32±0.38c | -2.38±0.02c | -2.59±0.05abc | 80.01±0.36c |

| PAW10s | 81.47±0.53c | -1.87±0.11b | -3.32±0.48bc | 81.08±0.43c |

| PAW15s | 83.03±0.36b | -1.83±0.04b | -2.54±0.44abc | 82.74±0.32b |

| PAW20s | 85.28±0.63a | -1.59±0.02a | -1.89±0.41a | 85.06±0.59a |

| PAW25s | 83.11±0.79b | -2.04±0.14b | -2.38±0.81ab | 82.82±0.85b |

| T2b | T21 | T22 | |

| CK | 0.825±0.195a | 92.573±0.229b | 6.662±0.128a |

| PAW5s | 0.867±0.783a | 94.798±0.310a | 4.335±0.493b |

| PAW10s | 0.700±0.056a | 96.287±0.173a | 3.014±0.115b |

| PAW15s | 0.797±0.128a | 96.815±0.130a | 2.389±0.009b |

| PAW20s | 0.698±0.142a | 95.965±0.231a | 3.336±0.368b |

| PAW`25s | 0.749±0.147a | 95.362±2.428a | 3.889±2.459b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).