Introduction

Iron deficiency is a widespread condition, affecting approximately

25% of the general population and 30–45% of chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients [

1]. Although bone marrow iron staining is the gold standard for assessing iron stores, its invasiveness limits routine use. Consequently, serum ferritin and transferrin saturation (TSAT) are widely used biomarkers—ferritin reflecting iron storage and TSAT indicating iron availability. Iron is vital for hemoglobin and myoglobin function, DNA synthesis, enzymatic activity, and mitochondrial energy production [

2]. Ferritin functions not only as an iron storage protein but also as an acute-phase reactant, rising in response to inflammation, malignancy, and systemic disease. Elevated ferritin has been associated with poor outcomes in

sepsis [

3]

, acute myocardial infarction [

4]

, cerebrovascular disease [

5]

, and rheumatoid disorders [

6], highlighting its dual role as a marker of both iron status and inflammation. To better distinguish these effects, future studies should incorporate inflammatory markers such as CRP and IL-6, along with immunomodulators like vitamin D, to determine whether adverse outcomes are driven by iron imbalance or underlying inflammation [

7].

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines suggest starting iron therapy in non-dialysis CKD patients if ferritin is below 100 ng/mL and transferrin saturation (TSAT) is below 40%, or if ferritin is between 100 and 300 ng/mL with a TSAT less than 25%. Conversely, iron supplementation is typically avoided when ferritin is above 700 ng/mL or TSAT exceeds 40% [

8]. A large retrospective study of 18,878 non-dialysis-dependent-CKD patients found no link between ferritin levels and mortality in females, while in males, ferritin <100 ng/mL was associated with a 23% increase in all-cause mortality by 23%, and TSAT ≤20% was associated with a 121% increase in all-cause mortality, suggesting that TSAT may be a superior prognostic marker [

9]. Another study found that low TSAT was a stronger predictor of mortality and MACE in NDD-CKD patients, while ferritin ≥300 ng/mL was linked to higher mortality, with no consistent associations at lower ferritin levels [

10]. These findings underscore the limitations of ferritin as a standalone biomarker, as it may reflect inflammation rather than true iron status. Despite growing interest, data on iron deficiency in non-anemic CKD patients are limited. This study addresses that gap by examining clinical outcomes by ferritin levels in non-anemic female CKD patients.

This study aims to evaluate the impact of serum ferritin levels on clinical outcomes in non-anemic female patients with stage 3 CKD over a five-year period. Using TriNetX data, it examines associations with all-cause mortality, MACE, AKI, pneumonia, fractures, and CKD progression (GFR ≤30 mL/min). The findings aim to clarify ferritin’s role in CKD progression and inform individualized iron management strategies.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study was conducted by analysing data from the TriNetX network and adhered to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. TriNetX is a global federated health research network (

https://live.trinetx.com/) that offers access to electronic medical records—including diagnoses, procedures, medications, laboratory results, and genomic data—from numerous large healthcare organizations (HCOs). This study utilized a subset of HCOs within the Global Collaborative Network, which includes 139 healthcare organizations. The study features a Compare Outcomes Analysis titled "Ferritin <100 ng/mL vs 100–700 ng/mL Analysis," generated by the TriNetX platform on March 1, 2025, at 07:11:50 UTC. This analysis compares outcomes between two groups: Cohort A, consisting of 67,091 patients classified as F<100, and Cohort B, consisting of 60,238 patients classified as F100–700. TriNetX, facilitates the querying of deidentified patient data from the electronic health records of hundreds of member healthcare organizations. The de-identification of patient data by TriNetX complies with Section §164.514(b)(1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule [

11]. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital (Approval Number: 14-IRB027; approval date: 06/03/2025). 140 healthcare organizations were queried at the time of analysis using ICD-10 codes aligned with the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study Cohorts

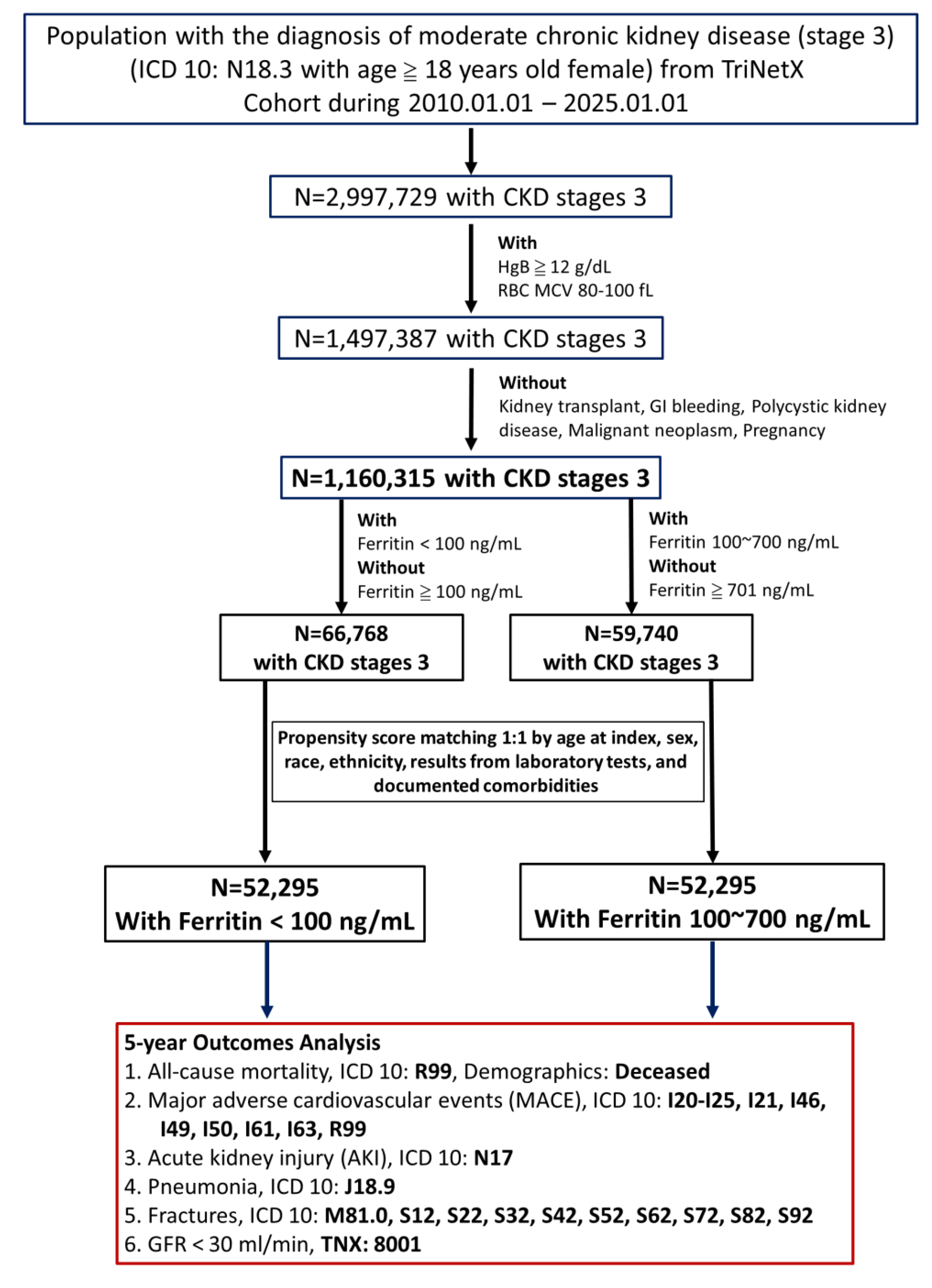

Patient selection criteria, cohort characteristics, and the analytical methodology for assessing the long-term (5-year) outcomes in females with CKD stage 3 can be seen in Figure 1. The study involved females aged 18 years and older with moderate chronic kidney disease (CKD) defined by ICD-10 code N18.3, hemoglobin levels of 12 g/dL or higher, normal mean corpuscular volume (MCV) between 80 and 100 fL, and available serum ferritin measurements recorded between January 1, 2010, and January 1, 2025. Patients were excluded if they had a history of kidney transplantation (ICD-10: Z94.0), genitourinary tract malignancies (ICD-10: C51-C58, C64-C68), pregnancy (ICD-10: O00-O08, O09, O10-O16, O60-O77, O20-O29, O30-O48), or gastrointestinal bleeding (ICD-10: K92.2), conditions that may indicate more severe illness. Initially, 66,768 patients had low ferritin levels, and 59,740 had adequate ferritin levels; following 1:1 propensity score matching, each cohort included 52,295 patients. Moderate CKD (stage 3) was defined in this study using ICD-10 code N18.3 and TriNetX code 8001, with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated by the creatinine-based MDRD formula.

The study compares patients with a low ferritin group (<100 ng/mL) and an adequate ferritin group (100~700 ng/mL). To reduce the effect of demographic confounders, 1:1 propensity score matching was performed based on demographic factors. The primary outcomes assessed over five years include all-cause mortality (ICD-10: R99), major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (ICD-10: I20-I25, I21, I46, I49, I50, I61, I63, R99), acute kidney injury (ICD-10: N17), pneumonia (ICD-10: J18.9), fractures (ICD-10: M81.0, S12, S22, S32, S42, S52, S62, S72, S82, S92), and progression to GFR < 30 mL/min (TNX: 8001).

Figure 1.

Flowchart outlining the patient selection process for the study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart outlining the patient selection process for the study.

Data Analysis

The data analysis for this study involved evaluating clinical outcomes in propensity-matched cohorts of stage 3 CKD, non-anemic women with low or adequate serum ferritin levels over a follow-up period of five years. The presence of additional comorbidities or covariates such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, menopause, age, 25-vitamin D and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were also analyzed compared between the two cohorts.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to calculate survival probabilities, and Cox proportional hazards regression models were applied to determine hazard ratios for all outcomes. Kaplan-Meier curves illustrate survival probability over time following an index event. In Kaplan-Meier functional analysis, TriNetX provides datasets where patients are censored if their last documented clinical event falls within the observation period. However, when calculating cohort risks for a specific timeframe, TriNetX includes these patients rather than excluding them. To address this, the five-year observation period was divided into consecutive 90-day intervals. Thereafter, we determined the number of patients with the outcome and the corresponding risk for each 90-day interval (excluding repeated measures) and summed these values to obtain the total number of patients with the outcome over five years (90 x 21 = 1890 days). Using these manually aggregated data, cumulative survival rates were computed using the Kaplan-Meier estimator to compare cohorts using the log-rank test. The survival analysis was performed using the 'survival' R package for R software (version 4.4.2, Vienna, Austria).

To assess statistical significance, independent two-sample t-tests were conducted, and the Bonferroni-Holm correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons across three tests, with adjusted α thresholds iteratively defined (e.g., α = 0.0083 for the smallest p-value of six tests). The pre-specified six primary outcomes for analysis: mortality, MACE, AKI, pneumonia, fractures, and CKD progression. For these outcomes, both unadjusted p-values and Holm–Bonferroni adjusted p-values were reported—for example, an adjusted significance level of α = 0.0083 was used for the smallest p-value among the six tests—to control the family-wise error rate across all planned comparisons. However, because of the reduced sample size after propensity score matching, the adjustment was not consistently applied across all analyses. Despite this, all results identified as statistically significant in the manuscript had unadjusted p-values below their respective significance thresholds.

Sensitivity analysis: To assess the potential variability in clinical outcomes based on ferritin levels, the sensitivity analyses using narrower ferritin ranges (100–300, 300–500, and 500–700 ng/mL) as well as modeling ferritin as a continuous variable were conducted.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 66,768 low ferritin patients and 59,740 adequate ferritin patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study.

Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of patient baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching. Demographic data, diagnosis comorbidity prevalence, medication usage, and laboratory values, were compared between patients with low or adequate ferritin levels. Propensity score matching successfully eliminated differences in demographic variables between the two cohorts. Before matching, the adequate ferritin group was older (63.4 ± 12.4 years vs. 59.6 ± 13.9 years, p<0.001, standardized difference = 0.290) and had a lower proportion of White patients (70.9% vs. 62.6%, p<0.001). Hypertensive diseases and Diabetes mellitus were significantly more prevalent in the adequate ferritin group (28.3% vs. 26.0%, p<0.001; 10.9% vs. 10.3%, p<0.001). After matching, demographic disparities were minimized, as reflected by standardized differences approaching zero.

Key laboratory parameters also showed notable variations; the adequate ferritin group had significantly higher ferritin levels (177.0 ± 133.2ng/m vs. 49.2 ± 34.4 ng/mL, p<0.001), elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) and CRP levels, indicating a possible association between elevated ferritin and metabolic or inflammatory disturbances. Conversely, the low ferritin group exhibited higher bicarbonate (26.3 ± 3.2 ng/mL vs. 25.9 ± 3.4 ng/mL, p<0.001) and calcidiol (vitamin D) levels (39.6 ± 19.1 ng/mL vs. 37.4 ± 18.6 ng/mL, p<0.001). These findings suggest that ferritin levels may influence systemic inflammation, mineral metabolism, and cardiovascular risk factors in non-anemic CKD patients.

Residual confounding due to inflammation is an important limitation, as ferritin acts as an acute-phase reactant. In the cohort, higher ferritin levels were significantly associated with elevated CRP values, indicating a greater inflammatory burden. To address this, CRP was included in the propensity score model categorized into four strata, each achieving standardized mean differences below 0.1, indicating sufficient balance between groups. Nonetheless, the overall CRP comparison between cohorts remained statistically significant, suggesting the presence of minor but meaningful residual confounding. The detailed results of this four-level CRP adjustment are provided in Supplemental

Table 1. Furthermore, baseline characteristics of other laboratory parameters that initially showed imbalance were reported before and after propensity score matching to support stratified analyses.

The Association of Serum Ferritin Level with Clinical Outcomes

Cox proportional-hazards analysis (Supplemental Table 2)

Cox proportional-hazards models were used to estimate the risk of six outcomes by comparing patients with ferritin levels below 100 ng/mL to those with ferritin between 100 and 700 ng/mL (reference group). Compared to women with ferritin levels of 100–700 ng/mL, those with ferritin <100 ng/mL showed lower risks of all-cause mortality (HR 0.897; 95% CI 0.832–0.968; p=0.0048), acute kidney injury (AKI) (HR 0.857; 95% CI 0.812–0.904; p<0.0001), and pneumonia (HR 0.893; 95% CI 0.845–0.943; p<0.0001). No significant difference was found in progression to eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m² (HR 0.973; 95% CI 0.93–1.018; p=0.2359), as the confidence interval included 1. Conversely, low ferritin was associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (HR 1.042; 95% CI 1.018–1.067; p=0.0007) and fractures (HR 1.236; 95% CI 1.202–1.27; p<0.0001).

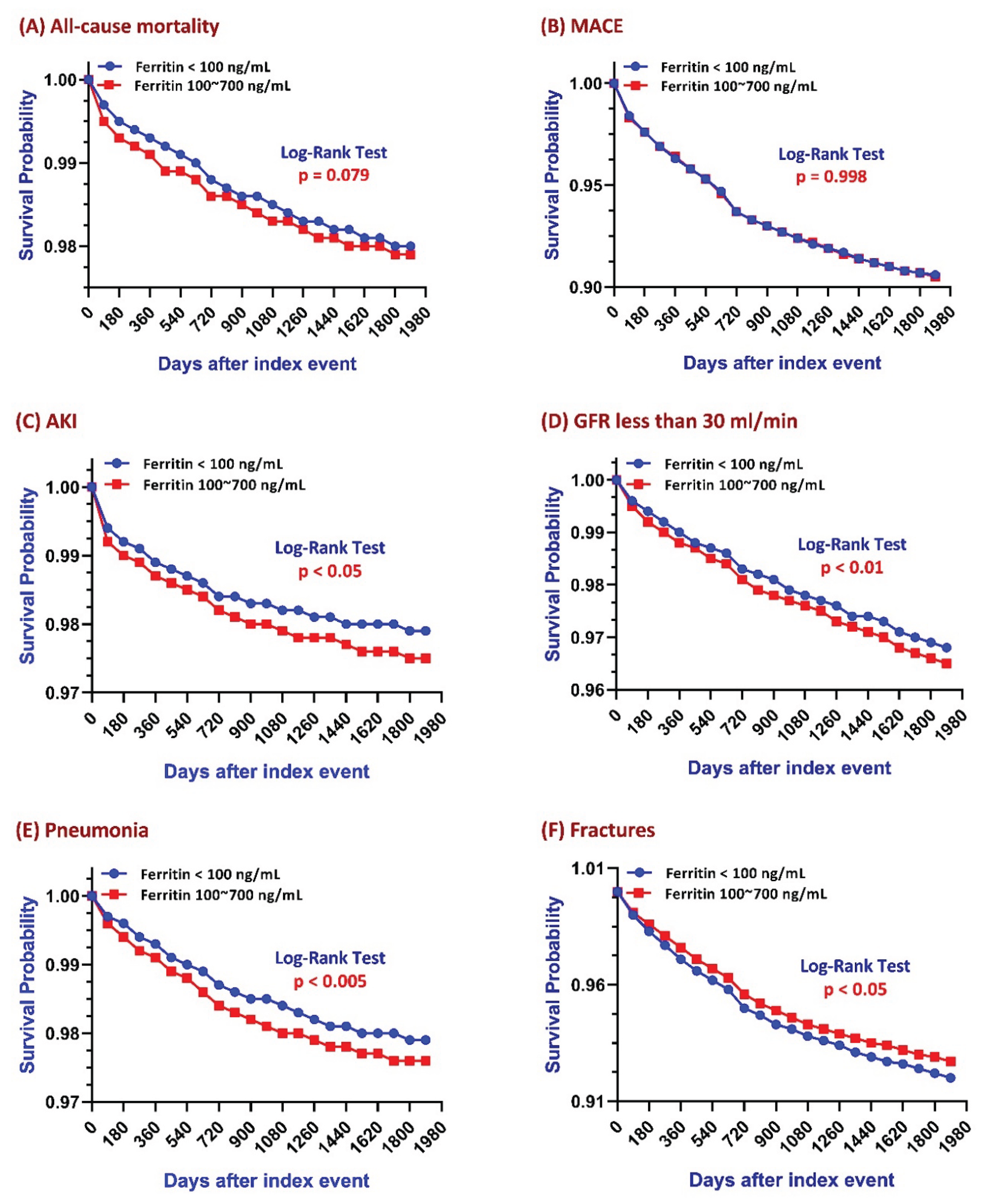

Kaplan–Meier survival analyses (

Figure 2) demonstrated differential long-term risks between low ferritin and adequate ferritin patients. Over a 5-year follow-up:

All-Cause mortality and MACE

Overall risk for all-cause mortality and MACE across the 5-year observation period were not statistically significantly different between the two groups (

Figure 2A & 2B). However, Kaplan–Meier analysis for all-cause mortality (

Figure 2A) showed a clear separation starting at year 1, with the adequate ferritin group exhibiting a significantly higher mortality risk during the first two years of follow-up. As illustrated in

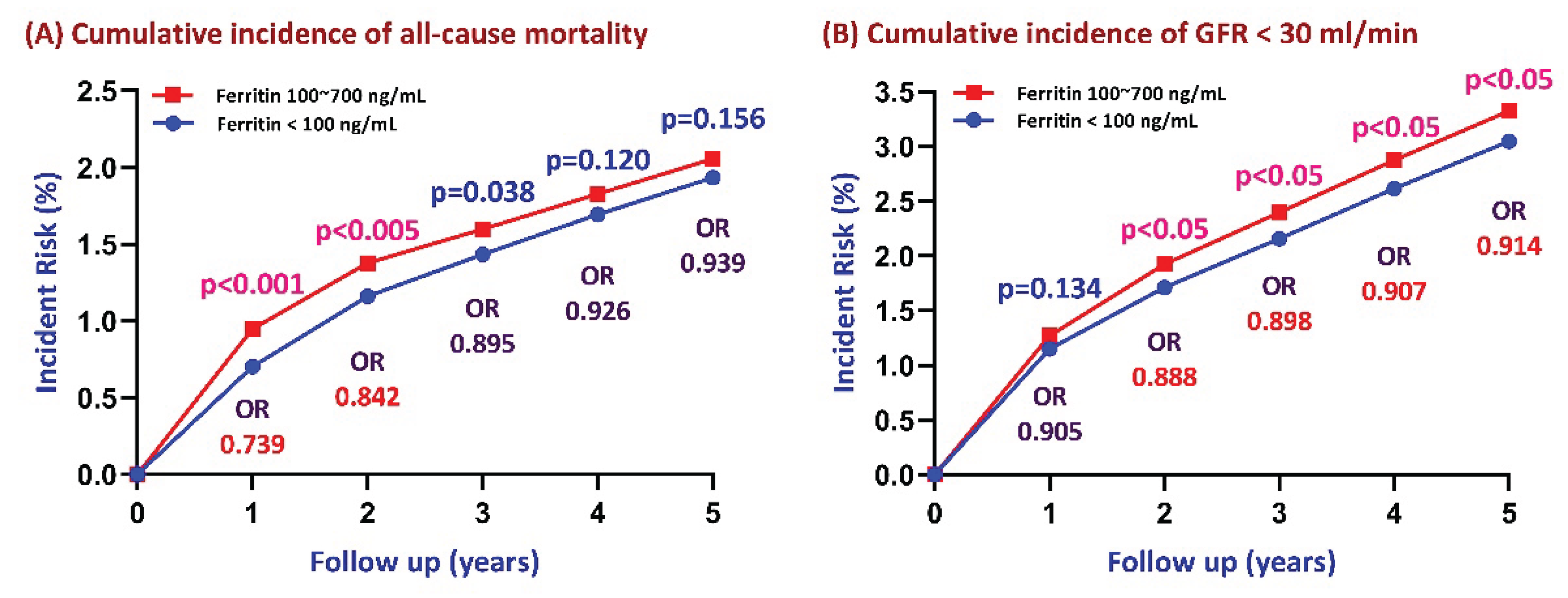

Figure 3A, the cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality was consistently higher in the adequate ferritin group at year 1 (p < 0.001) and year 2 (p < 0.05), but the difference became non-significant beyond year 2 (year 3, p = 0.038; year 4, p = 0.120; year 5, p = 0.156). The difference in mortality risk between the two groups dissipated over time, with yearly odds ratios progressively converging on 1.

Figure 2.

Five-year Kaplan–Meier survival curves evaluating the association between serum ferritin levels and clinical outcomes in patients stratified by ferritin levels (100–700 ng/mL vs. <100 ng/mL).

Figure 2.

Five-year Kaplan–Meier survival curves evaluating the association between serum ferritin levels and clinical outcomes in patients stratified by ferritin levels (100–700 ng/mL vs. <100 ng/mL).

Figure 3.

Association between serum ferritin levels and five-year cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality and renal function decline (defined as GFR < 30 mL/min). P-values and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for comparisons between ferritin levels of 100–700 ng/mL and <100 ng/mL at the end of each follow-up year.

Figure 3.

Association between serum ferritin levels and five-year cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality and renal function decline (defined as GFR < 30 mL/min). P-values and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for comparisons between ferritin levels of 100–700 ng/mL and <100 ng/mL at the end of each follow-up year.

AKI andrenal function Decline

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that log-rank p-values for both AKI and renal function decline were <0.05 & <0.01 respectively, indicating significantly lower incidence rates in patients with lower ferritin levels (

Figure 2C & 2D). CKD progression was defined as a decline in GFR to <30 mL/min/1.73 m². Patients in the adequate ferritin group experienced a significantly faster decline in renal function (log-rank p < 0.01). As shown in

Figure 3B, the cumulative incidence of CKD progression over the 5-year follow-up was consistently higher in the adequate ferritin group compared to the low ferritin group. Although the between-group difference was not significant at year 1 (p = 0.134), it became statistically significant from year 2 onward (p < 0.05). The difference in CKD progression risk between the two cohorts dissipated over time, with ORs of 0.888 at year 2, 0.898 at year 3, 0.907 at year 4, and 0.914 at year 5.

Pneumonia

Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a significantly lower incidence of pneumonia in patients with low ferritin levels (log-rank p < 0.05;

Figure 2E).

Fractures

Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a significantly higher fracture risk in the low ferritin group (p < 0.05;

Figure 2F). A comparison of the cohort’s overall risk at 5-years follow-up confirmed this association, suggesting that low ferritin may contribute to increased fracture risk, possibly due to impaired bone metabolism related to iron deficiency.

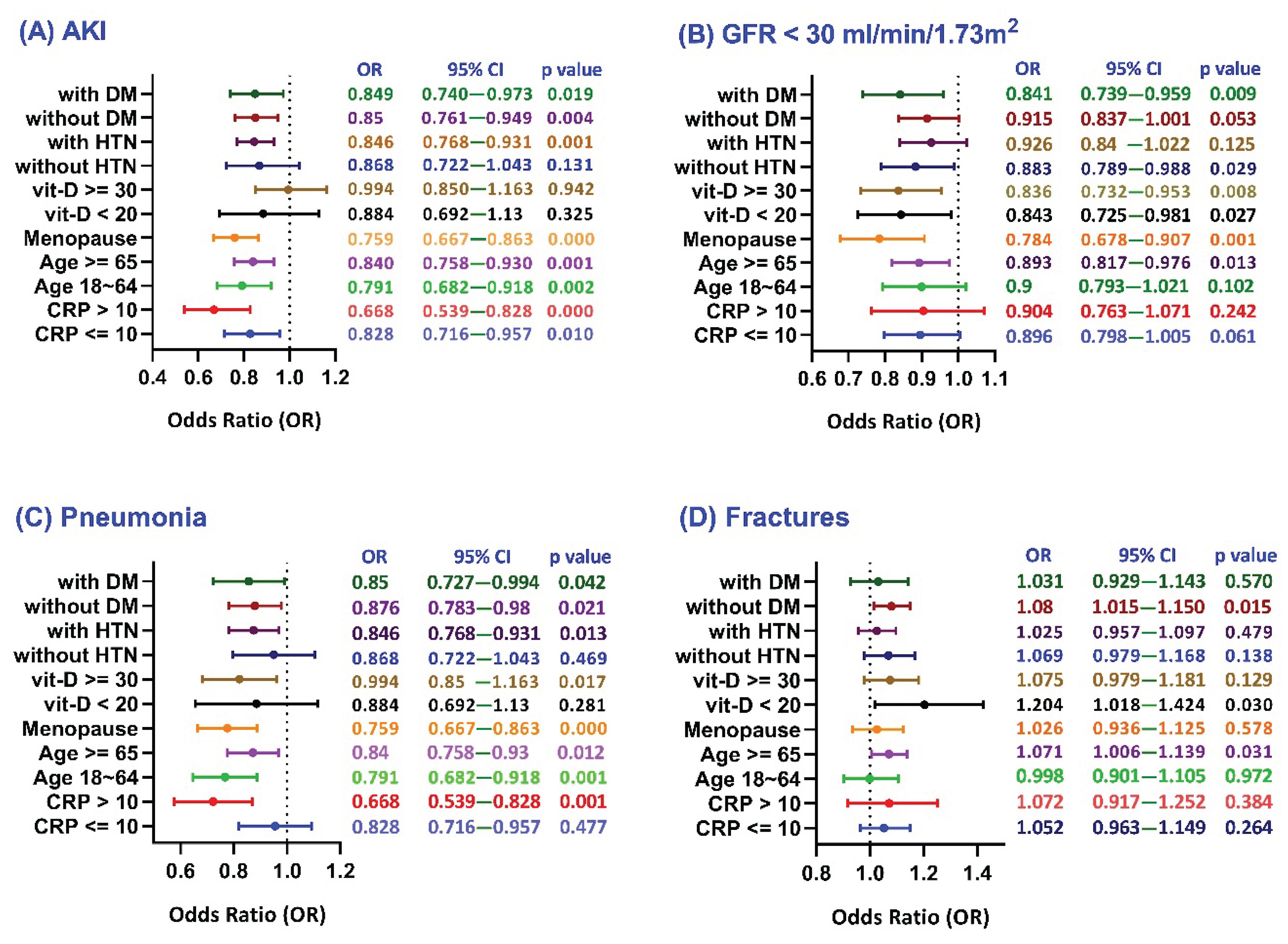

Subgroup Analyses of Clinical Outcomes by Ferritin Levels (100–700 ng/mL vs. <100 ng/mL)

The forest plots present subgroup analyses of 5-year clinical outcomes—including acute kidney injury (AKI;

Figure 4A), renal function decline (GFR <30 mL/min;

Figure 4B), pneumonia (

Figure 4C), and fractures (

Figure 4D) —in female patients with moderate CKD and normal hemoglobin levels. The analysis examines the influence of key variables such as CRP levels (≤10 vs. >10 mg/L), age (18–64 vs. ≥65 years), menopausal status, vitamin D levels (<20 vs. ≥30 ng/mL), and the presence or absence of hypertension (HTN) and diabetes (DM) on these outcomes.

Figure 4.

Forest plots depicting subgroup analyses of selected covariates in relation to specific clinical outcomes among patients stratified by serum ferritin levels (100–700 ng/mL vs. <100 ng/mL).

Figure 4.

Forest plots depicting subgroup analyses of selected covariates in relation to specific clinical outcomes among patients stratified by serum ferritin levels (100–700 ng/mL vs. <100 ng/mL).

Acute Kidney Injury and Renal function decline

The analysis shows that lower ferritin levels were generally associated with reduced risks of AKI and renal function decline, suggesting a potential protective effect. The greatest reduction in AKI risk was observed in patients with elevated CRP (>10 mg/L), postmenopausal women, and individuals aged 18–64 years (

Figure 4A). Similarly, the strongest protective effects against renal decline were seen in postmenopausal women, those with vitamin D ≥30 ng/mL, patients with diabetes, and older adults (

Figure 4B).

Pneumonia

The low ferritin group was associated with a reduced risk of pneumonia across most subgroups (

Figure 4C). The strongest protective effects were seen in patients with elevated CRP (>10 mg/L), younger age (18–64 years), and postmenopausal women. Notably, protection was also observed in those with vitamin D deficiency and diabetes, suggesting that systemic inflammation, hormonal status, and metabolic or nutritional factors may influence pneumonia risk in female CKD patients.

Fractures

The adequate ferritin group (100–700 ng/mL) was associated with a lower fracture risk, suggesting a protective role of iron stores in bone health (

Figure 4D). The protective effect of adequate ferritin on fracture risk was significant in patients with vitamin D deficiency, older age (≥65), and without diabetes. No significant difference was observed in younger patients, indicating that age-related bone loss may be more influential than ferritin levels in fracture risk among younger CKD women.

Collectively, Kaplan–Meier survival analyses revealed that the adequate-ferritin group experienced higher mortality during the first two years; however, this difference became non-significant thereafter, with odds ratios approaching one. In contrast, the associations with AKI, pneumonia, and renal decline remained statistically significant and stable over the five-year follow-up period (log-rank p < 0.05 for AKI and pneumonia; p < 0.01 for renal decline). These effects were more pronounced and clinically meaningful in high-risk subgroups—such as patients with CRP levels above 10 mg/L, postmenopausal women, and younger individuals—where the protective effect of low ferritin was most evident. Although mortality differences lessened over time and effect sizes varied, the consistent pattern of results across multiple outcomes and subgroups supports biologically plausible mechanisms involving inflammation and iron metabolism, highlighting the need for further prospective research.

Sensitivity Analysis to Assess the Impact of Ferritin Levels on Clinical Outcome Heterogeneity

To assess potential variability in clinical outcomes associated with ferritin levels, sensitivity analyses were conducted using narrower ferritin categories (100–300, 300–500, and 500–700 ng/mL) and by modeling ferritin as a continuous variable. These approaches did not materially change the overall findings (see Supplemental Table 3). Among non-anemic women with stage 3 CKD, baseline ferritin below 100 ng/mL was not significantly associated with five-year all-cause mortality when compared to the broader 100–700 ng/mL range. However, sensitivity analyses demonstrated substantially lower mortality hazards in the low ferritin group compared to higher ferritin subgroups (301–500 and 501–700 ng/mL), suggesting that elevated ferritin may be more strongly linked to mortality risk than iron deficiency itself. Ferritin levels under 100 ng/mL showed minimal and inconsistent associations with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), with only a slight increase in risk observed relative to the 100–300 ng/mL category. Notably, the low ferritin group exhibited a marked reduction in acute kidney injury risk compared to middle-range ferritin levels, indicating a potential renal protective effect. Ferritin concentrations did not significantly affect progression of chronic kidney disease or pneumonia risk. In contrast, low ferritin was consistently associated with a clinically meaningful increase in fracture risk across several comparisons, underscoring the importance of monitoring bone health in patients with low iron stores.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between serum ferritin levels and clinical outcomes in non-anemic, non-dialysis female patients with stage 3 CKD. Low ferritin levels (<100 ng/mL) were associated with reduced risks of AKI, renal decline, and pneumonia, particularly in postmenopausal women. Additionally, low ferritin was linked to lower all-cause mortality before year 2 and continued protection against renal decline beyond year 2. However, it was also associated with a higher risk of fractures, whereas adequate ferritin levels (100–700 ng/mL) were protective, especially in older adults and those with vitamin D deficiency. These findings underscore the complex role of ferritin in inflammation, bone health, and kidney function, demonstrating the importance of a personalized approach to CKD management.

Previous studies suggest that transferrin saturation (TSAT) is a more reliable predictor of mortality risk than serum ferritin. For instance, Guedes et al. found low TSAT, not ferritin, was more strongly associated with MACE, and serum ferritin ≥300 ng/mL showed no significant link to cardiovascular outcomes [3, 4]. Rostoker et al. also highlighted inflammation as a key confounder affecting the interpretation of ferritin and TSAT, with significant impacts on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in non-dialysis CKD patients [

12]. The study did not identify a statistically significant association between ferritin levels and 5-year all-cause mortality or major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) [9, 10]. Further analysis showed that low ferritin levels were associated with significantly lower mortality within the first two years, suggesting elevated ferritin—possibly reflecting inflammation—may contribute to short-term mortality in female CKD patients. These findings highlight the need for monitoring ferritin and investigating inflammatory markers to improve risk stratification and management.

In non-anemic CKD patients, the link between serum ferritin and kidney disease reflects the complex interaction of iron metabolism, inflammation, and kidney damage. A retrospective study in critically ill patients found ferritin levels >680 ng/mL were associated with higher 28-day mortality, regardless of sepsis, suggesting ferritin may indicate disease severity rather than cause injury directly [

13]. The Korean National Health Survey found high ferritin levels linked to increased CKD risk in men but not women, suggesting a possible sex-specific susceptibility to renal decline [

14]. Consistent with prior studies, the findings indicated that adequate ferritin levels (100–700 ng/mL) were associated with a higher incidence of AKI, while low ferritin levels (<100 ng/mL) were linked to a reduced risk of AKI—particularly among postmenopausal women, individuals aged 18–64, and those with CRP >10 mg/L—supporting the role of inflammation in increasing AKI risk.

Recent studies have clarified the link between ferritin and CKD progression. Tsai et al. found that elevated ferritin and hsCRP were independently associated with faster CKD progression and initiation of renal replacement therapy, with the highest ferritin tertile showing a 1.4-fold increased risk of renal decline [

15]. Eisenga et al. reported J- or U-shaped associations, with both low and high ferritin levels independently predicting CKD progression [

16]. Findings align with previous studies, indicating that female stage 3 CKD patients with adequate ferritin levels experienced greater renal decline over time, with the protective effect of low ferritin becoming most evident after year 2. This supports the role of inflammation in influencing ferritin’s impact, as CKD-related inflammation elevates hepcidin, promoting iron retention and ferritin synthesis. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α further drive kidney damage by increasing ferritin expression and disrupting iron balance [17-19].

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction, has emerged as a key mechanism in AKI. Unlike apoptosis or necrosis, ferroptosis contributes to renal tubular injury in animal models through iron overload and oxidative stress [

20]. Clinically, this is relevant as nearly 50% of patients with hospital-associated AKI develop new-onset CKD within 3.3 years [

21]. The transition from AKI to CKD is primarily driven by maladaptive repair, involving proximal tubule injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, immune activation, and chronic inflammation [

22]. Emerging preclinical data suggest that inhibiting ferroptosis may protect mitochondrial function, reduce inflammation, and prevent tubular injury, offering potential benefits in diabetic nephropathy and AKI [23-26]. These mechanisms may partly explain the long-term renal decline observed in this study. However, clinical evidence linking ferroptosis to AKI-to-CKD progression remains limited, warranting further investigation.

The link between serum ferritin and pneumonia risk in non-anemic CKD patients remains unclear due to limited direct evidence [14, 27]. In CKD, elevated ferritin often reflects chronic inflammation, complicating the distinction between true iron overload and inflammation-driven hyperferritinemia [

28]. Emerging evidence suggests elevated ferritin may indicate inflammatory burden and increased infection risk, including infection by influenza and SARS-CoV-2 [

29]. In CKD, a pro-inflammatory state, high ferritin likely reflects immune dysregulation rather than iron overload [30, 31]. Studies in critically ill patients further support this, linking hyperferritinemia to poorer sepsis outcomes, reinforcing its role as a marker of immune dysfunction [

32]. The study demonstrates a significant association between relatively high ferritin levels and increased pneumonia risk, while lower risk was observed in patients with reduced ferritin—especially among postmenopausal women, individuals with CRP >10 mg/L, and those aged 18–64. Prior research suggests iron overload may raise infection risk by promoting bacterial growth, especially in CKD patients on iron therapy [

33].

Lower ferritin levels (<100 ng/mL) were associated with an increased fracture risk in non-anemic CKD patients, particularly among those with low vitamin D, elevated CRP, and older age—suggesting a potential link between low ferritin and bone fragility. This aligns with prior research showing that iron deficiency impairs collagen synthesis and osteoblast function, reducing bone mineral density and increasing fracture risk [

34]. Iron deficiency leads to low bone turnover, impaired mineralization, and greater fracture risk, providing a mechanistic explanation for the increased fractures observed in the low-ferritin group [

35]. Patients with iron-deficiency anemia have also shown a higher risk of fractures, highlighting the essential role of iron in supporting skeletal integrity [

36]. Iron deficiency can impair bone metabolism, while excess iron may contribute to bone fragility through oxidative stress and reduced osteoblast activity [

37]. Additionally, CKD-related mineral and bone disorders independently affect bone health [

38]. These findings highlight the need for longitudinal studies incorporating bone turnover, inflammation, and mineral metabolism markers to clarify ferritin’s role in CKD-related bone fragility.

To address the potential for reverse causation inherent in retrospective studies, ferritin levels were measured at baseline prior to outcome assessment, followed by a five-year prospective follow-up to ensure proper temporal sequencing. The cohort was limited to stable, non-anemic women with stage 3 CKD, excluding individuals with conditions associated with severe inflammation to reduce bias from markedly ill patients. Furthermore, 1:1 propensity score matching was used to balance demographics, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory values between ferritin groups. Despite these measures, higher ferritin levels remained associated with elevated CRP, indicating the presence of residual confounding due to inflammation.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the lack of transferrin saturation (TSAT) data in the TriNetX network limited the assessment of iron availability. Second, the study did not fully adjust for key inflammatory markers such as CRP, nor did it account for the effects of iron supplementation, both of which could influence the relationship between ferritin levels and clinical outcomes. Finally, as the study population was predominantly white and based in the United States, generalizability to other ethnicities and regions may be limited, highlighting the need for future research in more diverse cohorts.

Conclusions

This study underscores the multifaceted role of serum ferritin in non-anemic female patients with stage 3 CKD. Over five years, low ferritin levels (<100 ng/mL) were consistently linked to reduced risks of AKI, renal decline, and pneumonia—particularly in patients with inflammation, younger age, or postmenopausal status. Conversely, adequate ferritin levels (100–700 ng/mL) were associated with lower fracture risk, especially in older adults and those with vitamin D deficiency, suggesting a protective role in bone health. While overall mortality and MACE risks were comparable, early mortality was higher in the adequate ferritin group, possibly reflecting inflammatory burden. These findings highlight the need to interpret ferritin not only as an iron marker but also as an indicator of inflammation. Individualized ferritin targets based on age, comorbidities, inflammation, and bone health may improve clinical risk assessment. Further research is warranted to confirm these associations and inform iron management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-C.L., M-T. L, and C.-L. L.; literature search, Y.-C. H., J. W., K.-W. T., and L.-J. S.; data collection, K.-C.L., L.-J. S., and Y.-C. W.; data analysis, J. W. and K.-W. T.; statistical analysis, J.W. and K.-C.L.; manuscript preparation, M-T. L and K.-W.T.; manuscript editing, C.-L.L. and K.-C.L.; manuscript review, Y.-C. W. and K.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (TCRD-TPE-113-RT-3(1/3)), and Taoyuan Armed Forces General Hospital (TYAFGH-A-114003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital (approval number: 14-IRB027; approval date: 06/03/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Since the study does not involve identifiable patients, written in-formed consent for publication is not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The dataset was obtained from the TriNetX global federated health research network, which collects deidentified electronic medical records from multiple healthcare institutions. Access to the dataset is restricted by institutional policies and data-sharing agreements. Researchers interested in accessing the data may request it from TriNetX, subject to institutional approval and compliance with data privacy regulations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank the Core Laboratory at the Department of Research, Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, for their technical support and the use of their facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 395, (10225), 709-733.

- Lopez, A.; Cacoub, P.; Macdougall, I. C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Iron deficiency anaemia. Lancet (London, England) 2016, 387, 907–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtner, A.; Tymoszuk, P.; Nairz, M.; Lehner, G. F.; Fritsche, G.; Vales, A.; Falkner, A.; Schennach, H.; Theurl, I.; Joannidis, M.; Weiss, G.; Pfeifhofer-Obermair, C. , Linkage of alterations in systemic iron homeostasis to patients' outcome in sepsis: a prospective study. Journal of intensive care 2020, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinza, C.; Floria, M.; Popa, I. V.; Burlacu, A., The Prognostic Performance of Ferritin in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 12, (2).

- Balla, J.; Balla, G.; Zarjou, A. Ferritin in Kidney and Vascular Related Diseases: Novel Roles for an Old Player. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Seyhan, S.; Pamuk Ö, N.; Pamuk, G. E.; Çakır, N. , The correlation between ferritin level and acute phase parameters in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. European journal of rheumatology 2014, 1, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenercioglu, A. K.; Gonen, M. S.; Uzun, H.; Sipahioglu, N. T.; Can, G.; Tas, E.; Kara, Z.; Ozkaya, H. M.; Atukeren, P. , The Association between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Levels and Pro-Inflammatory Markers in New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Prediabetes. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabed Eknoyan, N. L., Wolfgang C. Winkelmayer, KDIGO 2025 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR ANEMIA IN CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE (CKD). Kidney Int Supp 2025, (in print), 1-140.

- Yu, H.; Shao, X.; Guo, Z.; Pang, M.; Chen, S.; She, C.; Cao, L.; Luo, F.; Chen, R.; Zhou, S.; Xu, X.; Nie, S. , Association of iron deficiency with kidney outcome and all-cause mortality in chronic kidney disease patients without anemia. Nutrition journal 2025, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M.; Muenz, D. G.; Zee, J.; Bieber, B.; Stengel, B.; Massy, Z. A.; Mansencal, N.; Wong, M. M. Y.; Charytan, D. M.; Reichel, H.; Waechter, S.; Pisoni, R. L.; Robinson, B. M.; Pecoits-Filho, R. , Serum Biomarkers of Iron Stores Are Associated with Increased Risk of All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events in Nondialysis CKD Patients, with or without Anemia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2020, 32, 2020–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palchuk, M. B.; London, J. W.; Perez-Rey, D.; Drebert, Z. J.; Winer-Jones, J. P.; Thompson, C. N.; Esposito, J.; Claerhout, B. , A global federated real-world data and analytics platform for research. JAMIA open 2023, 6, ooad035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostoker, G.; Lepeytre, F.; Rottembourg, J. , Inflammation, Serum Iron, and Risk of Mortality and Cardiovascular Events in Nondialysis CKD Patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2022, 33, 654–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Yu, L.; Ma, C.; Wang, R. , Association of serum ferritin and all-cause mortality in AKI patients: a retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in medicine 2024, 11, 1368719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. T.; Linton, J. A.; Kwon, S. K.; Park, B. J.; Lee, J. H. , Ferritin Level Is Positively Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease in Korean Men, Based on the 2010-2012 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. International journal of environmental research and public health 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y. C.; Hung, C. C.; Kuo, M. C.; Tsai, J. C.; Yeh, S. M.; Hwang, S. J.; Chiu, Y. W.; Kuo, H. T.; Chang, J. M.; Chen, H. C. , Association of hsCRP, white blood cell count and ferritin with renal outcome in chronic kidney disease patients. PloS one 2012, 7, e52775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, H.; Nakayama, M.; Haruyama, N.; Fukui, A.; Yoshitomi, R.; Tsuruya, K.; Nakano, T.; Kitazono, T. , Association between iron status markers and kidney outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease. Scientific reports 2023, 13, 18278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torti, F. M.; Torti, S. V. , Regulation of ferritin genes and protein. Blood 2002, 99, 3505–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, D. R.; McMurdo, M.; Karaca, G.; Wilflingseder, J.; Leaf, I. A.; Gupta, N.; Miyoshi, T.; Susa, K.; Johnson, B. G.; Soliman, K.; Wang, G.; Morizane, R.; Bonventre, J. V.; Duffield, J. S. , Interleukin-1β Activates a MYC-Dependent Metabolic Switch in Kidney Stromal Cells Necessary for Progressive Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2018, 29, 1690–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Lu, X.; Ren, J.; Privratsky, J. R.; Yang, B.; Rudemiller, N. P.; Zhang, J.; Griffiths, R.; Jain, M. K.; Nedospasov, S. A.; Liu, B. C.; Crowley, S. D. , KLF4 in Macrophages Attenuates TNFα-Mediated Kidney Injury and Fibrosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2019, 30, 1925–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, L.; Yuan, C.; Wu, X. , Targeting ferroptosis in acute kidney injury. Cell death & disease 2022, 13, 182. [Google Scholar]

- Bucaloiu, I. D.; Kirchner, H. L.; Norfolk, E. R.; Hartle, J. E.; Perkins, R. M. , Increased risk of death and de novo chronic kidney disease following reversible acute kidney injury. Kidney international 2012, 81, 477–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Yanagita, M. , Pathophysiology of AKI to CKD progression. Seminars in nephrology 2020, 40, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.; Xu, D.; Zhao, W.; Lu, H.; Chen, R.; Duan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, L. , CIRBP promotes ferroptosis by interacting with ELAVL1 and activating ferritinophagy during renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2021, 25, 6203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, W.; Hu, F.; Xi, Y.; Chu, Y.; Bu, S. , Mechanism of Ferroptosis and Its Role in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of diabetes research 2021, 2021, 9999612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. J.; Jiang, X.; Gao, C. C.; Chen, Z. W. , Salusin-β participates in high glucose-induced HK-2 cell ferroptosis in a Nrf-2-dependent manner. Molecular medicine reports 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L. , The Cross-Link between Ferroptosis and Kidney Diseases. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2021, 2021, 6654887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernan, K. F.; Carcillo, J. A. , Hyperferritinemia and inflammation. International immunology 2017, 29, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, N.; Takasawa, K. , Impact of Inflammation on Ferritin, Hepcidin and the Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegelund, M. H.; Glenthøj, A.; Ryrsø, C. K.; Ritz, C.; Dungu, A. M.; Sejdic, A.; List, K. C. K.; Krogh-Madsen, R.; Lindegaard, B.; Kurtzhals, J. A. L.; Faurholt-Jepsen, D. , Biomarkers for iron metabolism among patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia caused by infection with SARS-CoV-2, bacteria, and influenza. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica 2022, 130, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, T.; Pawelzik, S. C.; Witasp, A.; Arefin, S.; Hobson, S.; Kublickiene, K.; Shiels, P. G.; Bäck, M.; Stenvinkel, P. , Inflammation and Premature Ageing in Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxins 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr, M.; Brandenburg, V.; Brunner-La Rocca, H. P. , How to diagnose iron deficiency in chronic disease: A review of current methods and potential marker for the outcome. European journal of medical research 2023, 28, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, F. S.; Nyvlt, P.; Heeren, P.; Spies, C.; Adam, M. F.; Schenk, T.; Brunkhorst, F. M.; Janka, G.; La Rosée, P.; Lachmann, C.; Lachmann, G. , Differential Diagnosis of Hyperferritinemia in Critically Ill Patients. Journal of clinical medicine 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T.; Aronoff, G. R.; Gaillard, C.; Goodnough, L. T.; Macdougall, I. C.; Mayer, G.; Porto, G.; Winkelmayer, W. C.; Wish, J. B. , Iron Administration, Infection, and Anemia Management in CKD: Untangling the Effects of Intravenous Iron Therapy on Immunity and Infection Risk. Kidney medicine 2020, 2, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, S. J.; Choi, Y. R.; Roh, Y. H.; Yun, B. H.; Cho, S.; Choi, Y. S.; Lee, B. S.; Seo, S. K. , Association between levels of serum ferritin and bone mineral density in Korean premenopausal and postmenopausal women: KNHANES 2008-2010. PloS one 2014, 9, e114972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Brackel, F. N.; Oheim, R. , Iron and bones: effects of iron overload, deficiency and anemia treatments on bone. JBMR Plus 2024, 8, ziae064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; An, J. , Dietary iron intake and its impact on osteopenia/osteoporosis. BMC endocrine disorders 2023, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhang, H.; He, W.; Zhang, H. , Iron accumulation and its impact on osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B 2023, 24, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketteler, M.; Evenepoel, P.; Holden, R. M.; Isakova, T.; Jørgensen, H. S.; Komaba, H.; Nickolas, T. L.; Sinha, S.; Vervloet, M. G.; Cheung, M.; King, J. M.; Grams, M. E.; Jadoul, M.; Moysés, R. M. A. , Chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney international 2025, 107, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).