1. Introduction

Electron correlation energy lies at the heart of quantum chemistry. [

1,

2] However, the computational cost of high-level

post-Hartree

–Fock methods skyrockets with system size. In this context, there is a pressing need for alternative lower-scaling cost-efficient methods across broad classes of systems. In recent years, the information-theoretic approach (ITA) [

3,

4,

5,

6] has emerged as a promising framework for understanding and predicting the electron correlation energy from the perspective of information theory. By treating the electron density as a continuous probability distribution, ITA introduces a set of descriptors—such as Shannon entropy [

7] and Fisher information [

8]—that encode global and local features of the electron density distribution. These quantities are inherently basis-agnostic and physically interpretable, providing a new lens through which quantum chemical problems can be approached.

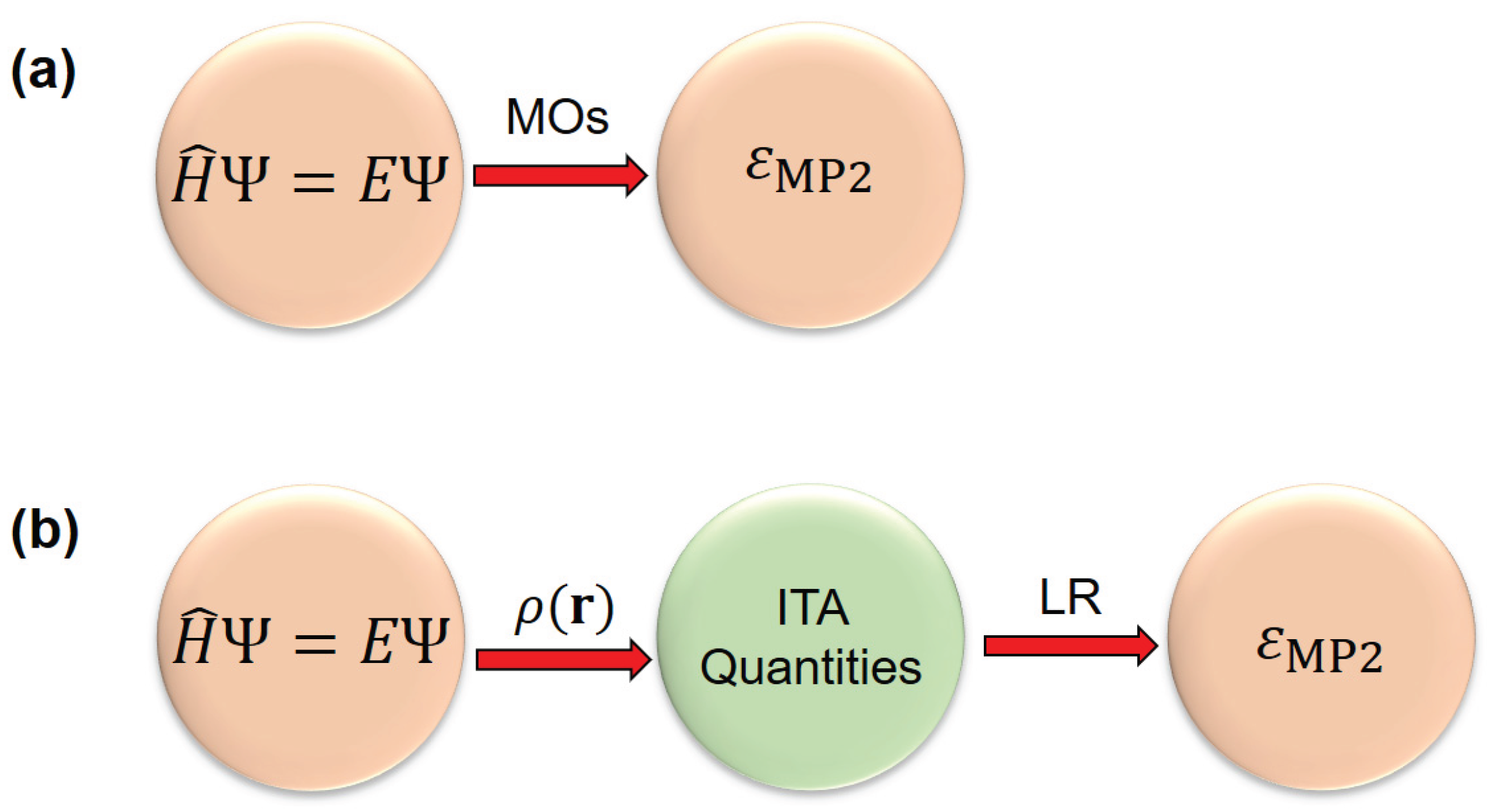

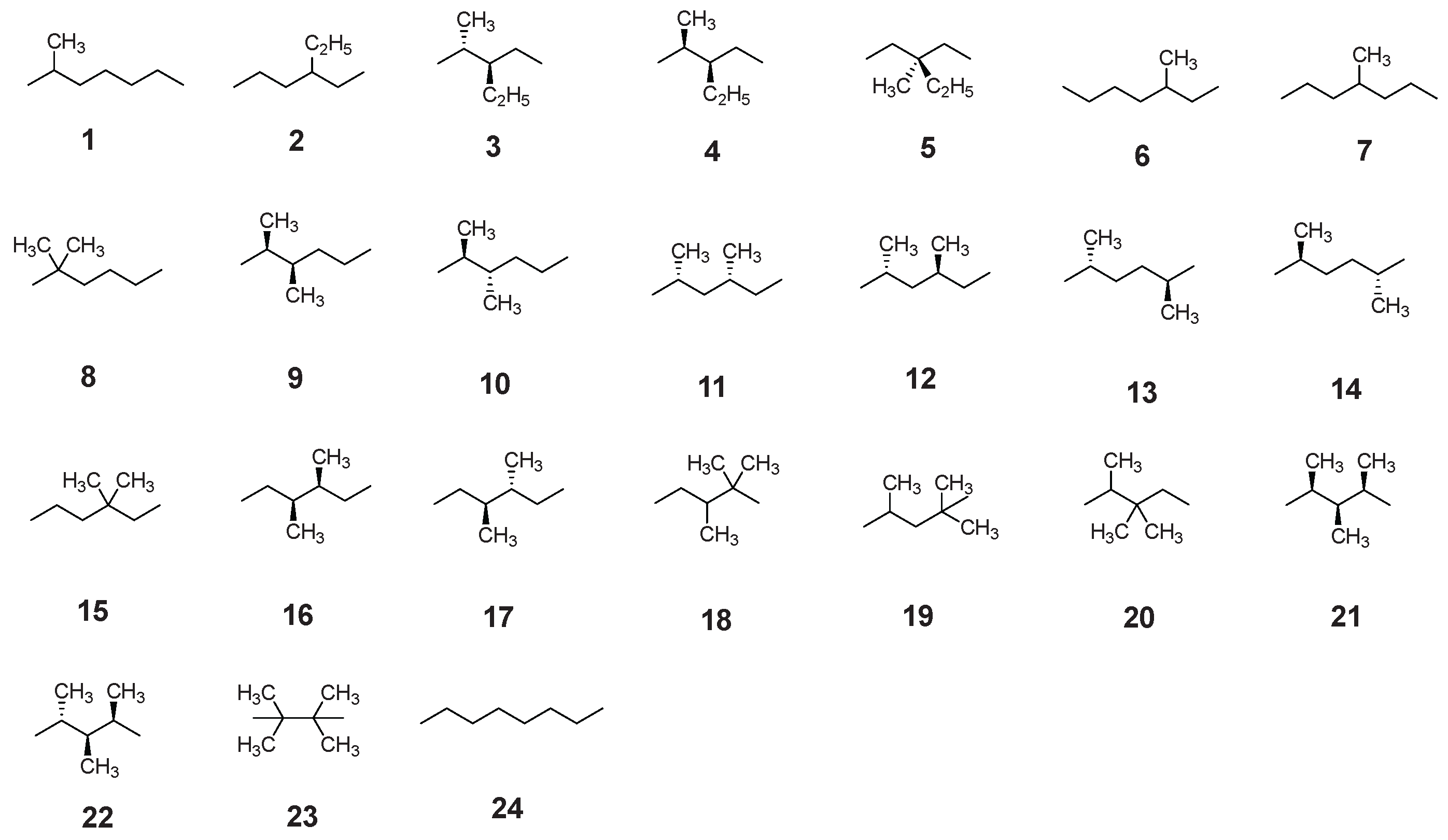

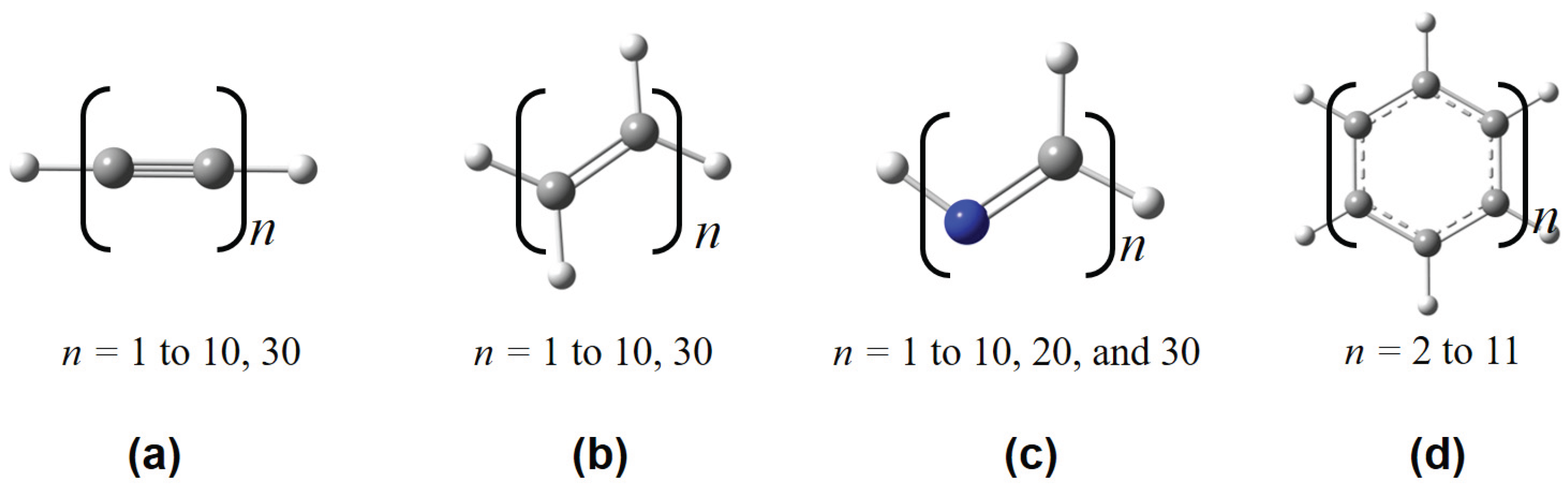

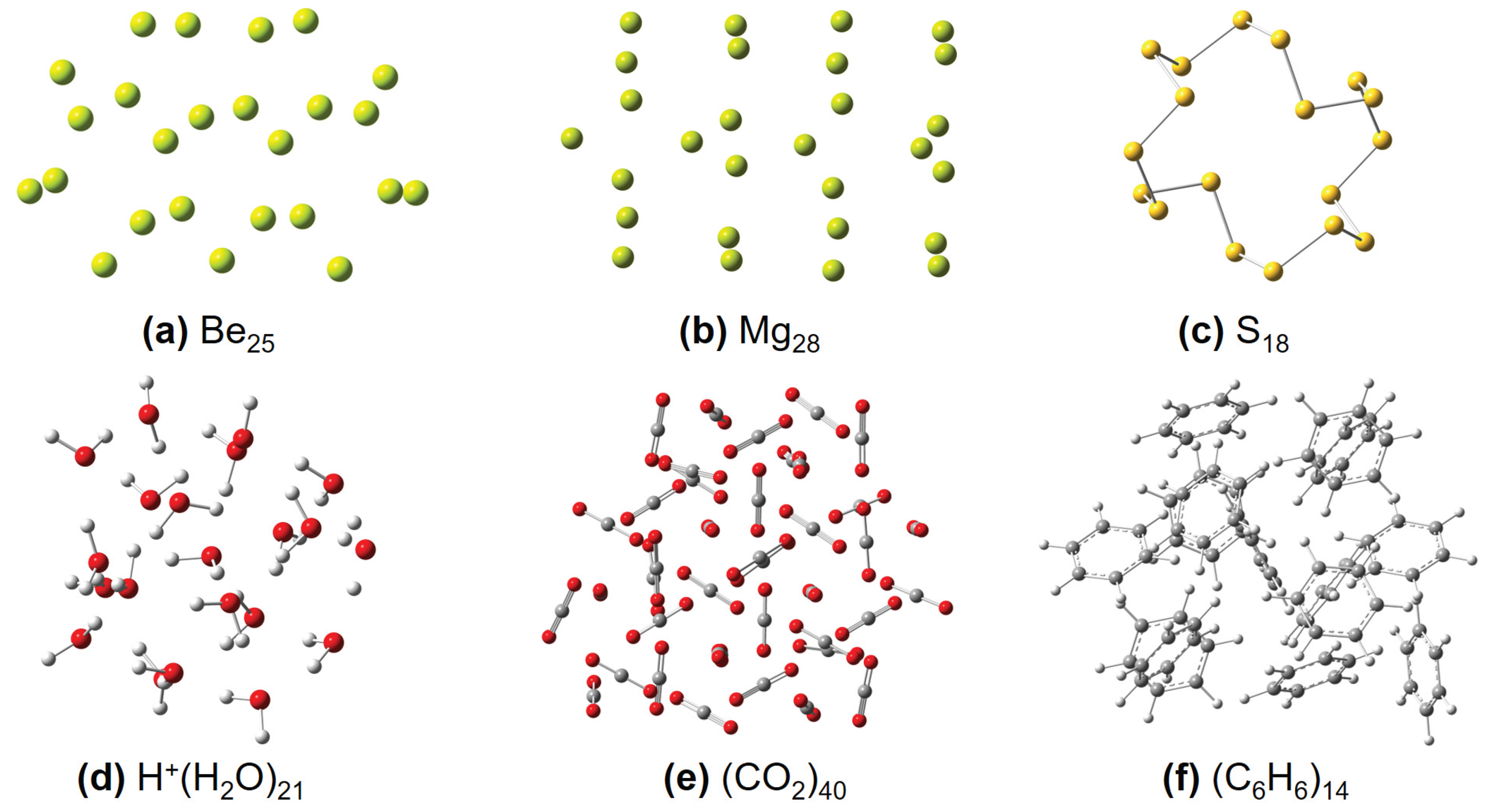

In continuation with our previous work by employing the simple density-based ITA quantities to appreciate response properties [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] (such as molecular polarizability and NMR chemical shielding constant) and energetics of elongated hydrogen chains, [

14] in this work, we aim to predict the

post-Hartree

–Fock (see

Figure 1) electron correlation energies of various molecular clusters and linear or quasi-linear organic polymers with increasing cluster size and polymer length. These systems including 24 octane isomers (see

Figure 2); [

11,

15] (

ii) polymeric structures (see

Figure 3), polyyne, polyene, all-

trans-polymethineimine, and acene; [

11] (

iii) molecular clusters (see

Figure 4), such as metallic Be

nand Mg

n, [

16,

17] covalent S

n, [

18,

19] hydrogen-bonded protonated water clusters H

+(H

2O)

n, [

20] and dispersion-bound carbon dioxide (CO

2)

n, [

21] and benzene clusters (C

6H

6)

n. [

22] We construct strong linear relationships between the low-cost Hartree

–Fock [

23] ITAs and the electron correlation energies from

post-Hartree

–Fock methods, such as MP2 or RI-MP2, [

24,

25] CCSD, [

26] and CCSD(T). [

27] It is noteworthy to mention that MP2 is mainly used here only as a proof-of-concept; Hartree

–Fock can be simply replaced with any approximate functionals of density functional theory (DFT) [

28,

29].

By examining trends across increasing cluster size and polymer length, we assess the transferability, scalability, and physical insights provided by ITA features in capturing electron correlation. Our findings highlight not only the feasibility of ITA-driven correlation energy prediction, but also reveal key descriptors that most strongly govern correlation effects in extended systems. These results suggest that ITA may serve as a promising direction for developing efficient, interpretable, and physically grounded models in quantum machine learning and electronic structure theory.

2. Results

To validate the accuracy of the LR(ITA) method, we choose a total of 24 octane isomers as shown in

Figure 2. MP2, CCSD, and CCSD(T) are used to generate the electron correlation energies and ITA quantities are obtained at the Hartree‒Fock level at the same basis set 6-311++G(d,p) level. More details can be found in the

Supplementary Information (SI, Table S1).

Table 1 shows the linear relationships and RMSDs between the LR(ITA)-predicted and calculated electron correlation energies. For

SS,

IF, and

SGBP, the RMSDs are < 2.0 mH, indicating that LR(ITA) should be accurate enough to predict the electron correlation energies. Because CCSD and CCSD(T) are too computationally-intensive and intractable, only MP2 is used hereafter as proof-of-concept.

In

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5, we have collected the linear correlation coefficients (

R2 = 1.000) and RMSDs (root mean squared deviations) between the calculated correlation energies at the MP2/6-311++G(d,p) level and those predicted based on the ITA quantities at the HF/6-311++G(d,p) level for polyyne, polyene, all-

trans-polymethineimine, and acene, respectively. More details can be found in

Tables S2–S5. It is clearly showcased that

R2 is close to 1 for most ITA quantities. More strikingly, based on the linear regression (LR) equations of ITA quantities, the predicted electron correlations deviate from the calculated ones only by ~1.5 mH for polyyne, ~3.0 mH for polyene, and < 4.0 mH for all-

trans-polymethineimine. For acene, the RMSDs are reasonably satisfactory by ~ 10 ‒ 11 mH. These results collectively reveal that ITA quantities are indeed good descriptors of electron correlations for those linear or quasi-linear polymeric systems with delocalized electronic structures. For more challenging acenes, a single ITA quantity fails to capture sufficient amount of information of more delocalized electronic structures.

Shown in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 are the results of the linear correlation coefficients (

R2) and RMSDs (root mean squared deviations) between the calculated correlation energies at the MP2/6-311++G(d,p) level and those predicted based on the ITA quantities at the HF/6-311++G(d,p) level for neutral metallic Be

n, Mg

n, and covalent S

n systems, respectively. More details can be found in

Tables S6–S11. One can see that strong correlations exist (

R2 > 0.990) between ITA quantities and MP2 correlation energies, indicating that they are extensive in nature. However, the predicted electron correlation energies deviate much from the calculated ones by ~28 ‒ 37 mH for Be

n, ~17 ‒ 33 mH for Mg

n, and ~26 ‒ 42 mH for S

n, respectively. These results collectively showcase that for 3-dimensional metallic clusters, Be

n and Mg

n, and covalent S

n, a single ITA quantity fails to quantitively capture enough amount information of electron energies of complex systems.

Shown in

Table 9 are the results of the linear correlation coefficients (

R2), the corresponding regression coefficients, and RMSDs (root mean squared deviations) between the calculated correlation energies at the MP2/6-311++G(d,p) level and those predicted based on the ITA quantities at the HF/6-311++G(d,p) level for hydrogen-bonded protonated water clusters. One can see that strong correlations exist (

R2 = 1.000) between (8 out of 11) ITA quantities and MP2 correlation energies, indicating that they are extensive in nature. The RMSDs range from 2.1 (

and

) to 9.3 (

) mH, indicating that ITA quantities are good descriptors of the

post-Hartree‒Fock electron correlation energies of hydrogen-bonded systems.

Finally, we will switch our gear to two dispersion-bound clusters, (CO

2)

n and (C

6H

6)

n.

Table 10 gives the strong correlations (

R2 = 1.000) and RMSDs between the RI-MP2 correlation energies and Hartree‒Fock ITA quantities at the same basis set 6-311++G(d,p) for (CO

2)

n(

n = 4 ‒ 40). More details can be found in

Table S12. The RMSDs vary from 6.3 (

and

) to 10.8 (

) to 14.6 (

) mH. For (C

6H

6)

n (

n = 4 ‒ 14) clusters, we have calculated the linear correlations (

R2 = 1.000) and RMSDs between the MP2/6-311++G(d,p) electron correlation energies and HF/6-311++G(d,p) ITA quantities, as collected in

Table 11. More details can be found in

Tables S13 and S14. The RMSDs range from 2.8 (

) to 6.9 (

) to 10.7 (

) mH. The RMSD results collectively suggest (8 out of 11) ITA quantities are reasonably good descriptors of the

post-Hartree‒Fock electron correlation energies of dispersion-bound clusters.

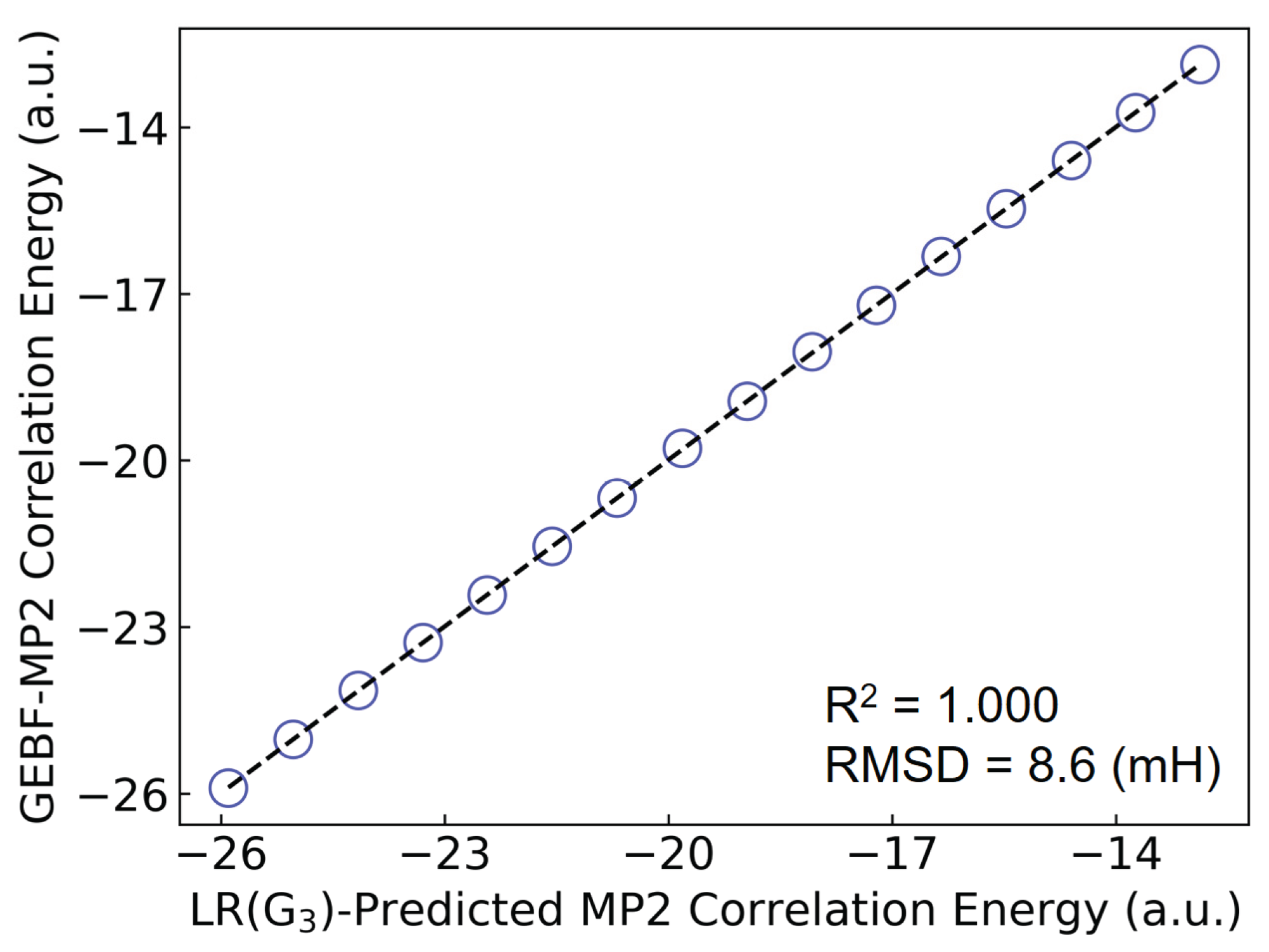

To further verify the accuracy of the LR(ITA) method, we employ some relatively larger (C

6H

6)

n (

n = 15 ‒ 30) clusters to this end. Plus, conventional MP2/6-311++G(d,p) calculations are too computationally-intensive, we employ GEBF [

30,

31,

32,

33] to obtain the MP2-level electron correlation energies as reference. Finally, as the linear regression based on the ITA quantity

has the least RMSD value, we choose LR(G

3) to make predictions of electron correlation energies of benzene clusters. More details can be found in Tables 15 and 16.

Figure 5 shows a comparison of the LR(G

3)-predicted and GEBF-calculated MP2 electron correlation energies for benzene clusters. The RMSD is 8.6 mH, indicative that the LR(ITA) method has a comparable performance to the linear-scaling GEBF method. In addition, we have found that when subsystem wavefunctions (thus electron density and ITA quantities) are used to obtain the subsystem electron correlation energies, the final total electron correlation energies deviate from GEBF by 40.0 mH in terms of RMSD as shown in

Table S16. One possible for this observation may come from the error accumulation, rather than error cancellation.

3. Discussion

To accurately and efficiently predict the

post-Hartree‒Fock electron correlation energy at a relatively low cost is a hot area in the community of quantum chemistry. Starting from Hartree‒Fock molecular orbitals, there exist two typical methods. One is to calculate the local correlation energy, whose early development is due to Pulay and Sæbø; [

34,

35,

36] the other is to predict the correlation energy with the aid of deep learning (DL). [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46] Our proposed LR(ITA) method is a special favor of DL. Suffice to note that an inherent drawback of local correlation methods is to perform orbital localization. This problem is also encountered by the DL-driven method. For our LR(ITA) method, only the molecular orbitals (thus electron density) are required without any manipulation. Very recently, we have showcased the good accuracy of LR(ITA) and its variant DL(ITA). With LR(ITA), one can even predict the FCI-level electron correlation with the DMRG (density matrix renormalization group) algorithm as a solver for elongated hydrogen chain, [

14] and the RMSD is only a few mH. Moreover, with DL(ITA) where a total 11 ITA quantities are used as input, [

13] we have predicted the DLPNO-MP2 electron correlation energy for a database of > 90 K real organic molecules and the RMSD is about 6.8 mH. In addition, LR(ITA) is not limited to any

post-Hartree‒Fock electronic structure methods; MP2 is used here as a proof-of-concept. Thus, we have showcased that LR(ITA) is designed with architectural and conceptual simplicity and is numerically shown to be a good protocol to predict the electron correlation energies of various systems.

Admittedly, using LR(ITA) to accurately and efficiently predict the electron correlation energy is still in its infancy. In the near future, we will implement a new concept of “ITL-DL Loop”. The physics behind is simple: low-tier (such as semiempirical PM7 or even promolecular) electron densities are used as input for ITA quantities, and DL is introduced to obtain high-tier (such as DFT) electron densities. Based on the newly generated electron densities, ITA quantities are obtained and used as input for another either classical or quantum DL model to predict the electron correlation energies of electrons of physicochemical properties of molecules. Work along this line is in progress and the results will be presented elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Comparison of (a) conventional MP2 method (with Hartree‒Fock orbitals as input) and (b) linear regression LR(ITA) models used in this work, where the density-based information-theoretic approach (ITA) quantities are used as input. Here MP2 is used only as a proof-of-concept.

Figure 1.

Comparison of (a) conventional MP2 method (with Hartree‒Fock orbitals as input) and (b) linear regression LR(ITA) models used in this work, where the density-based information-theoretic approach (ITA) quantities are used as input. Here MP2 is used only as a proof-of-concept.

Figure 2.

Shown here are a total of 24 isomers of both branched and linear octane studied in this work.

Figure 2.

Shown here are a total of 24 isomers of both branched and linear octane studied in this work.

Figure 3.

Some representative polymeric structures used in this work, including (a) polyyne, (b) polyene, (c) all-trans-polymethineimine, and (d) acene.

Figure 3.

Some representative polymeric structures used in this work, including (a) polyyne, (b) polyene, (c) all-trans-polymethineimine, and (d) acene.

Figure 4.

Some representative molecular structures used in this work, including (a) Ben, (b) Mgn, (c) Sn, (d) [H+(H2O)n], (e) (CO2)n, and (f) (C6H6)n clusters, respectively.

Figure 4.

Some representative molecular structures used in this work, including (a) Ben, (b) Mgn, (c) Sn, (d) [H+(H2O)n], (e) (CO2)n, and (f) (C6H6)n clusters, respectively.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the LR(G3)-predicted and GEBF-calculated MP2-level electron correlation energies for benzene clusters (C6H6)n (n = 15 ‒ 30).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the LR(G3)-predicted and GEBF-calculated MP2-level electron correlation energies for benzene clusters (C6H6)n (n = 15 ‒ 30).

Table 1.

Strong linear correlations (R2) and RMSDa (in mH) between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for octane isomers.

Table 1.

Strong linear correlations (R2) and RMSDa (in mH) between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for octane isomers.

| ITA |

Method |

Slope |

Intercept |

R2

|

RMSD |

|

MP2 |

0.03673221 |

‒4.47037893 |

0.878 |

1.9 |

| |

CCSD |

0.02760739 |

‒3.77240773 |

0.897 |

1.3 |

| |

CCSD(T) |

0.03224137 |

‒4.22658251 |

0.893 |

1.5 |

|

MP2 |

0.01016369 |

‒21.9076991 |

0.987 |

0.6 |

| |

CCSD |

0.00756499 |

‒16.7278042 |

0.989 |

0.4 |

| |

CCSD(T) |

0.00885171 |

‒19.3909815 |

0.988 |

0.5 |

|

MP2 |

0.03958034 |

‒18.81389475 |

0.964 |

1.0 |

| |

CCSD |

0.02958941 |

‒14.48237993 |

0.974 |

0.6 |

| |

CCSD(T) |

0.03459737 |

‒16.75258592 |

0.972 |

0.8 |

Table 2.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for polyyne.

Table 2.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for polyyne.

| n |

|

/103

|

/103

|

|

/103

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

17.116 |

0.503 |

0.096 |

63.341 |

2.251 |

14.478 |

15.411 |

‒6.702 |

13.889 |

0.253 |

| 2 |

27.503 |

0.996 |

0.178 |

126.454 |

4.498 |

26.687 |

28.049 |

‒11.822 |

26.724 |

0.357 |

| 3 |

37.877 |

1.489 |

0.260 |

189.565 |

6.744 |

38.891 |

40.680 |

‒16.946 |

39.589 |

0.458 |

| 4 |

48.238 |

1.982 |

0.342 |

252.682 |

8.991 |

51.093 |

53.301 |

‒22.064 |

52.468 |

0.556 |

| 5 |

58.604 |

2.475 |

0.425 |

315.797 |

11.238 |

63.292 |

65.918 |

‒27.186 |

65.335 |

0.654 |

| 6 |

68.968 |

2.968 |

0.507 |

378.914 |

13.485 |

75.491 |

78.532 |

‒32.303 |

78.206 |

0.751 |

| 7 |

79.331 |

3.461 |

0.589 |

442.032 |

15.731 |

87.690 |

91.146 |

‒37.422 |

91.079 |

0.849 |

| 8 |

89.696 |

3.954 |

0.671 |

505.147 |

17.978 |

99.888 |

103.759 |

‒42.541 |

103.952 |

0.946 |

| 9 |

100.063 |

4.447 |

0.753 |

568.264 |

20.225 |

112.086 |

116.372 |

‒47.659 |

116.821 |

1.043 |

| 10 |

110.435 |

4.940 |

0.835 |

631.378 |

22.472 |

124.284 |

128.984 |

‒52.780 |

129.686 |

1.139 |

| 30 |

317.730 |

14.800 |

2.478 |

1893.708 |

67.408 |

368.246 |

381.243 |

‒155.141 |

387.180 |

3.076 |

| R 2 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| RMSD |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

2.9 |

Table 3.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for polyene.

Table 3.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for polyene.

| n |

|

/103

|

/103

|

|

/103

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

22.069 |

0.510 |

0.109 |

63.427 |

2.243 |

16.638 |

17.935 |

‒8.846 |

18.948 |

| 2 |

37.486 |

1.010 |

0.204 |

126.732 |

4.489 |

31.067 |

33.236 |

‒16.196 |

37.205 |

| 3 |

52.876 |

1.510 |

0.298 |

189.930 |

6.726 |

45.493 |

48.534 |

‒23.495 |

55.289 |

| 4 |

68.260 |

2.009 |

0.393 |

253.162 |

8.967 |

59.918 |

63.824 |

‒30.808 |

73.409 |

| 5 |

83.643 |

2.509 |

0.488 |

316.406 |

11.209 |

74.342 |

79.111 |

‒38.125 |

91.575 |

| 6 |

99.023 |

3.009 |

0.583 |

379.653 |

13.451 |

88.766 |

94.397 |

‒45.438 |

109.749 |

| 7 |

114.403 |

3.509 |

0.677 |

442.902 |

15.693 |

103.190 |

109.682 |

‒52.756 |

127.925 |

| 8 |

129.783 |

4.008 |

0.772 |

506.150 |

17.934 |

117.613 |

124.967 |

‒60.070 |

146.103 |

| 9 |

145.163 |

4.508 |

0.867 |

569.399 |

20.176 |

132.037 |

140.251 |

‒67.385 |

164.282 |

| 10 |

160.542 |

5.008 |

0.962 |

632.647 |

22.418 |

146.460 |

155.536 |

‒74.701 |

182.461 |

| 30 |

468.132 |

15.003 |

2.856 |

1897.616 |

67.253 |

434.930 |

461.224 |

‒221.004 |

546.043 |

| R 2 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| RMSD |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

2.4 |

Table 4.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for all-trans-polymethineimine.

Table 4.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for all-trans-polymethineimine.

| n |

|

|

/103

|

|

/103

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

17.891 |

0.602 |

0.109 |

84.234 |

4.138 |

16.585 |

17.767 |

17.765 |

| 2 |

29.226 |

1.194 |

0.204 |

168.281 |

8.272 |

30.918 |

32.784 |

35.058 |

| 3 |

40.534 |

1.786 |

0.300 |

252.322 |

12.406 |

45.247 |

47.797 |

52.420 |

| 4 |

51.834 |

2.377 |

0.395 |

336.418 |

16.546 |

59.576 |

62.805 |

69.772 |

| 5 |

63.128 |

2.969 |

0.490 |

420.432 |

20.675 |

73.905 |

77.814 |

87.181 |

| 6 |

74.418 |

3.561 |

0.585 |

504.457 |

24.806 |

88.234 |

92.823 |

104.601 |

| 7 |

85.706 |

4.152 |

0.680 |

588.488 |

28.940 |

102.564 |

107.833 |

121.973 |

| 8 |

96.990 |

4.744 |

0.775 |

672.535 |

33.072 |

116.894 |

122.845 |

139.422 |

| 9 |

108.273 |

5.336 |

0.871 |

756.623 |

37.210 |

131.224 |

137.857 |

156.850 |

| 10 |

119.552 |

5.927 |

0.966 |

840.677 |

41.345 |

145.555 |

152.870 |

174.241 |

| 20 |

232.308 |

11.844 |

1.917 |

1681.135 |

82.670 |

288.867 |

303.008 |

348.833 |

| 30 |

345.014 |

17.761 |

2.869 |

2521.373 |

123.976 |

432.195 |

453.192 |

523.649 |

| R 2 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| RMSD |

0.4 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

3.9 |

Table 5.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for acene.

Table 5.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for acene.

| n |

|

/103

|

/103

|

/103

|

/103

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

70.395 |

2.489 |

0.460 |

0.316 |

11.207 |

69.910 |

73.784 |

‒34.722 |

25.645 |

88.981 |

| 3 |

94.598 |

3.478 |

0.636 |

0.442 |

15.688 |

96.553 |

101.740 |

‒47.666 |

35.408 |

123.979 |

| 4 |

118.807 |

4.468 |

0.811 |

0.569 |

20.169 |

123.195 |

129.691 |

‒60.602 |

45.077 |

158.965 |

| 5 |

143.022 |

5.457 |

0.987 |

0.695 |

24.651 |

149.835 |

157.637 |

‒73.547 |

54.729 |

193.946 |

| 6 |

167.241 |

6.447 |

1.162 |

0.821 |

29.133 |

176.474 |

185.576 |

‒86.480 |

64.373 |

228.921 |

| 7 |

191.461 |

7.436 |

1.338 |

0.948 |

33.614 |

203.111 |

213.512 |

‒99.419 |

74.020 |

263.894 |

| 8 |

215.675 |

8.426 |

1.513 |

1.074 |

38.096 |

229.747 |

241.444 |

‒112.348 |

83.657 |

298.878 |

| 9 |

239.894 |

9.415 |

1.689 |

1.200 |

42.578 |

256.382 |

269.372 |

‒125.278 |

93.298 |

333.853 |

| 10 |

264.114 |

10.405 |

1.865 |

1.326 |

47.059 |

283.016 |

297.298 |

‒138.209 |

102.944 |

368.828 |

| 11 |

288.484 |

11.394 |

2.040 |

1.453 |

51.543 |

309.627 |

325.167 |

‒151.260 |

112.708 |

404.117 |

|

R2

|

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| RMSD |

10.5 |

11.5 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.6 |

11.9 |

10.4 |

10.9 |

10.3 |

Table 6.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for neutral Ben (n = 3 ‒ 25) clusters.

Table 6.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for neutral Ben (n = 3 ‒ 25) clusters.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R2

|

0.996 |

0.996 |

0.996 |

0.996 |

0.996 |

0.994 |

0.993 |

| RMSD |

28.5 |

28.6 |

27.9 |

28.0 |

27.9 |

35.9 |

37.1 |

Table 7.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for Mgn (n = 3 ‒ 20, and 28) clusters.

Table 7.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for Mgn (n = 3 ‒ 20, and 28) clusters.

| |

|

/103

|

/103

|

/103

|

/105

|

|

|

|

|

R2

|

0.998 |

0.996 |

0.996 |

0.996 |

0.996 |

0.995 |

0.993 |

0.995 |

| RMSD |

17.7 |

24.8 |

25.2 |

24.8 |

24.8 |

26.7 |

33.0 |

27.2 |

Table 8.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for covalent Sn (n = 2 ‒ 18) clusters. .

Table 8.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for covalent Sn (n = 2 ‒ 18) clusters. .

| |

|

/103

|

/103

|

/103

|

/106

|

|

|

|

|

R2

|

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.995 |

| RMSD |

29.5 |

26.9 |

26.7 |

26.9 |

26.9 |

27.7 |

29.5 |

42.2 |

Table 9.

Strong linear correlations and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for protonated water clusters.

Table 9.

Strong linear correlations and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for protonated water clusters.

| ITA |

Slope |

Intercept |

R2

|

RMSD (mH) |

|

‒0.03129182 |

0.00240752 |

1.000 |

4.2 |

|

‒0.00049499 |

0.01775234 |

1.000 |

2.2 |

|

‒0.00332260 |

0.01628422 |

1.000 |

2.2 |

|

‒0.00279107 |

0.01637182 |

1.000 |

2.1 |

|

‒3.24672546×10‒5

|

1.58843194×10‒2

|

1.000 |

2.1 |

|

‒0.02186241 |

0.00482623 |

1.000 |

3.0 |

|

‒0.02042257 |

‒0.00317343 |

1.000 |

6.8 |

|

‒0.01981287 |

0.03859503 |

1.000 |

9.3 |

Table 10.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for CO2 clusters. .

Table 10.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for CO2 clusters. .

| n |

|

/103

|

/103

|

/103

|

/105

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

35.676 |

4.618 |

0.604 |

0.777 |

0.608 |

90.119 |

94.242 |

87.199 |

| 5 |

44.343 |

5.772 |

0.755 |

0.972 |

0.760 |

112.597 |

117.629 |

110.311 |

| 6 |

52.975 |

6.925 |

0.905 |

1.166 |

0.911 |

135.124 |

141.177 |

133.364 |

| 7 |

61.551 |

8.078 |

1.056 |

1.360 |

1.063 |

157.664 |

164.803 |

156.231 |

| 8 |

70.225 |

9.232 |

1.207 |

1.555 |

1.215 |

180.182 |

188.320 |

179.164 |

| 9 |

78.890 |

10.385 |

1.357 |

1.749 |

1.367 |

202.688 |

211.805 |

202.144 |

| 10 |

87.459 |

11.538 |

1.508 |

1.943 |

1.519 |

225.201 |

235.323 |

225.314 |

| 11 |

96.066 |

12.691 |

1.659 |

2.138 |

1.671 |

247.744 |

258.928 |

248.319 |

| 12 |

104.630 |

13.845 |

1.810 |

2.332 |

1.823 |

270.253 |

282.434 |

271.861 |

| 13 |

113.096 |

14.997 |

1.960 |

2.526 |

1.975 |

292.762 |

305.941 |

295.591 |

| 14 |

121.760 |

16.151 |

2.111 |

2.721 |

2.127 |

315.271 |

329.437 |

318.380 |

| 15 |

130.261 |

17.303 |

2.262 |

2.915 |

2.279 |

337.783 |

352.939 |

342.101 |

| 16 |

138.809 |

18.456 |

2.412 |

3.110 |

2.431 |

360.299 |

376.486 |

365.340 |

| 17 |

147.426 |

19.610 |

2.563 |

3.304 |

2.582 |

382.823 |

400.036 |

388.562 |

| 18 |

155.935 |

20.763 |

2.714 |

3.498 |

2.734 |

405.331 |

423.523 |

411.987 |

| 19 |

164.464 |

21.916 |

2.864 |

3.692 |

2.886 |

427.851 |

447.048 |

435.461 |

| 20 |

173.049 |

23.069 |

3.015 |

3.887 |

3.039 |

450.351 |

470.533 |

458.492 |

| 21 |

181.681 |

24.222 |

3.166 |

4.081 |

3.190 |

472.899 |

494.173 |

481.566 |

| 22 |

190.085 |

25.375 |

3.316 |

4.275 |

3.342 |

495.391 |

517.595 |

505.485 |

| 23 |

198.669 |

26.528 |

3.467 |

4.275 |

3.342 |

517.900 |

541.108 |

528.669 |

| 24 |

207.333 |

27.681 |

3.618 |

4.470 |

3.494 |

540.447 |

564.742 |

551.542 |

| 25 |

215.912 |

28.834 |

3.768 |

4.664 |

3.645 |

562.977 |

588.305 |

575.132 |

| 26 |

224.348 |

29.987 |

3.919 |

4.858 |

3.797 |

585.450 |

611.697 |

598.457 |

| 27 |

232.942 |

31.140 |

4.069 |

5.053 |

3.950 |

607.998 |

635.332 |

621.629 |

| 28 |

241.311 |

32.292 |

4.220 |

5.247 |

4.102 |

630.486 |

658.742 |

646.216 |

| 29 |

249.849 |

33.445 |

4.371 |

5.441 |

4.253 |

653.028 |

682.370 |

669.245 |

| 30 |

258.485 |

34.598 |

4.521 |

5.636 |

4.405 |

675.542 |

705.876 |

692.513 |

| 31 |

266.924 |

35.751 |

4.672 |

5.830 |

4.557 |

698.031 |

729.325 |

716.064 |

| 32 |

275.455 |

36.904 |

4.823 |

6.025 |

4.709 |

720.528 |

752.779 |

739.801 |

| 33 |

283.987 |

38.057 |

4.973 |

6.219 |

4.861 |

743.042 |

776.303 |

763.194 |

| 34 |

292.460 |

39.209 |

5.124 |

6.413 |

5.013 |

765.584 |

799.882 |

786.656 |

| 35 |

301.250 |

40.363 |

5.275 |

6.608 |

5.165 |

788.149 |

823.593 |

809.202 |

| 36 |

309.838 |

41.516 |

5.425 |

6.802 |

5.316 |

810.635 |

847.024 |

832.618 |

| 37 |

318.350 |

42.669 |

5.576 |

7.191 |

5.620 |

833.121 |

870.410 |

856.497 |

| 38 |

326.874 |

43.822 |

5.727 |

7.385 |

5.772 |

855.667 |

894.049 |

879.546 |

| 39 |

335.361 |

44.974 |

5.877 |

7.579 |

5.924 |

878.154 |

917.451 |

903.378 |

| 40 |

343.794 |

46.127 |

6.028 |

7.774 |

6.076 |

900.680 |

941.037 |

927.399 |

|

R2

|

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| RMSD |

14.6 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

6.3 |

6.3 |

6.4 |

6.8 |

10.8 |

Table 11.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for benzene (C6H6)n clusters. .

Table 11.

Strong linear relationships (R2) and RMSDa between the calculatedb and predicted correlation energies based on the ITA quantitiesc for benzene (C6H6)n clusters. .

| n |

|

/103

|

/103

|

|

/103

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

182.943 |

5.993 |

1.136 |

759.350 |

26.923 |

172.970 |

183.096 |

‒87.149 |

221.627 |

| 5 |

228.316 |

7.490 |

1.420 |

948.919 |

33.629 |

216.208 |

228.869 |

‒108.820 |

277.997 |

| 6 |

273.691 |

8.987 |

1.703 |

1138.819 |

40.367 |

259.454 |

274.657 |

‒130.621 |

334.386 |

| 7 |

318.886 |

10.483 |

1.987 |

1328.458 |

47.078 |

302.685 |

320.404 |

‒152.252 |

391.102 |

| 8 |

364.310 |

11.980 |

2.270 |

1518.321 |

53.807 |

345.919 |

366.163 |

‒174.079 |

447.714 |

| 9 |

409.374 |

13.477 |

2.554 |

1708.000 |

60.526 |

389.160 |

411.955 |

‒195.780 |

504.763 |

| 10 |

454.744 |

14.974 |

2.838 |

1897.903 |

67.261 |

432.383 |

457.676 |

‒217.571 |

561.267 |

| 11 |

500.069 |

16.471 |

3.121 |

2087.468 |

73.973 |

475.630 |

503.477 |

‒239.230 |

617.793 |

| 12 |

545.054 |

17.967 |

3.404 |

2277.421 |

80.708 |

518.879 |

549.286 |

‒261.020 |

675.525 |

| 13 |

589.963 |

19.462 |

3.688 |

2467.339 |

87.442 |

562.104 |

595.025 |

‒282.767 |

733.570 |

| 14 |

635.264 |

20.959 |

3.971 |

2656.842 |

94.148 |

605.328 |

640.753 |

‒304.418 |

789.848 |

|

R2

|

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| RMSD |

10.7 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

7.1 |

6.9 |

7.3 |

7.3 |

7.5 |

2.8 |