1. Introduction

Environmental scientists and activists consider sustainable behavior, such as adopting eco-friendly products and habits, essential in effectively addressing environmental problems [

1]. Adopting sustainable behavior is necessary to mitigate environmental degradation and achieve sustainable development [

2]. However, despite significant scientific research and various efforts to raise awareness, unsustainable practices are still widespread [

3].

In Singapore, a survey on sustainable habits and climate change awareness revealed that, despite respondents' awareness of environmental problems in the country, they do not engage in sustainable behavior primarily because of the high costs involved and the inconvenience of adopting them [

4]. Moreover, Genovese [

5] reported that students at a university in Torino, Italy, do not necessarily take action, despite their sensitivity to environmental issues. Additionally, Nahar et al. [

6] identified unsustainable use of automobiles, solid waste, and domestic activities as major pollution sources contributing to environmental degradation.

Furthermore, studies have shown that behavioral patterns become more unsustainable as humans develop socio-economically [

7,

8]. In the Philippines, it was reported by Never and Albert [

9] that the growing number of middle-class lack significant concern about the environmental impact of their lifestyle choices. Additionally, Montebon et al. [

10] revealed in their study that household practices in both rural and urban areas in the National Capital Region (NCR) of the Philippines lean towards sustainability; however, unsustainable practices are still evident, such as the use of non-renewable energy sources, the usage of single-use plastics, and improper waste disposal.

Sustainable behaviors are essential in addressing environmental problems and ensuring the sustainability of the planet [

11]. In addition, they can improve human well-being and quality of life by promoting the satisfaction of human psychological needs [

12]. As declared by Pritchard and Richardson [

13], human well-being is intricately connected with nature’s well-being, emphasizing the importance of sustainable behaviors as a factor that strengthens this connection.

The study explores the connection between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior as mediated by social connectedness. It is framed within Stern’s integrated

Attitude-Behavior-Context (ABC) Theory [

14], which posits that behavior (B) is a product of the interaction between attitudinal variables (A) and contextual factors (C), which includes interpersonal influences. In the context of the study, the interaction of environmental attitude (attitudinal variable) and social connectedness (contextual factor) determines the contingency of an environmentally sound behavior. Smith and Kingston [

15] posited that attitudinal and social factors have complex and dynamic connections that predict sustainable behavior. In addition, Xing et al. [

16] asserted that individuals with high social trust and social identity drawn from social connectedness are more likely to exhibit their positive environmental attitude through sustainable behaviors.

The

Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Stern et al. [

17] underpins the relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior. This theory proposes that sustainable behavior occurs when positive values, beliefs, and personal norms are present. Tian et al. [

18] revealed that a positive environmental attitude significantly predicts green behavior. In addition, Khan et al. [

19] claimed that decisions related to sustainable behavior highly depend on consumers’ environmental attitudes.

The relationship between environmental attitude and social connectedness is grounded in the

Social Identity Theory of Tajfel and Turner [

20]. This theory proposes that individuals identify themselves and others whose attributes are similar to theirs as members of one social group (Social Identification), which results in a sense of connection among them [

21]. In the same manner, individuals may identify themselves as members of one social group with others who share the same environmental attitudes as them, resulting in social connectedness. Studies have shown that positive environmental attitudes are highly correlated with social connectedness [

22]. In addition, individuals who promote environmental protection become more motivated if they are connected with others who share the same attitude [

23].

Deci and Ryan’s

Self-Determination Theory [

24] supports the relationship between social connectedness and sustainable behavior. Deci and Ryan [

24] posited that one of the human's basic psychological needs is

relatedness, or the need to feel a sense of connectedness to others. When individuals feel connected with others, engagement in desirable behaviors increases. Triantafyllidis and Darvin [

25] revealed that an increased sense of social bonding cultivates environment-friendly behavior. In addition, van Hoepen [

26] revealed that social connectedness positively correlates with environmental concern, resulting in environmentally sustainable behavior.

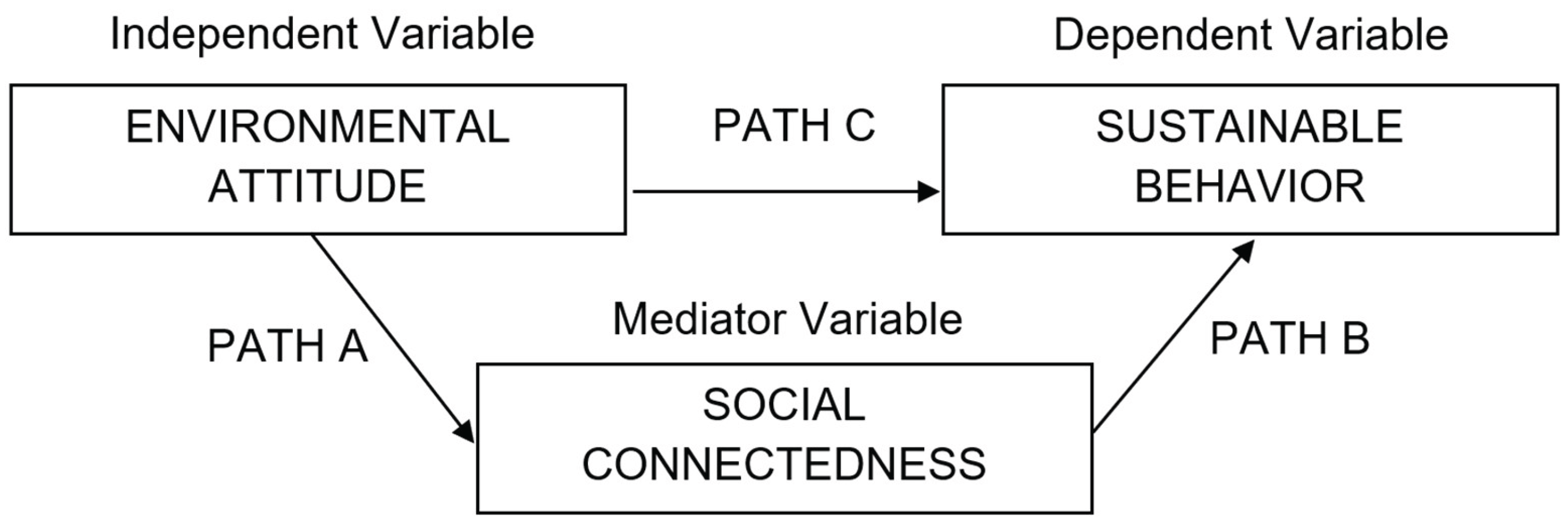

The variables of the study are shown in

Figure 1. The independent variable is the students’ environmental attitude.

Environmental attitude refers to the collection of beliefs, values, and behavioral intentions a person holds about the environment [

27]. The dependent variable is the students' sustainable behavior.

Sustainable behavior is a set of intentional actions that aim to satisfy present needs without compromising future generations' ability to satisfy their own [

11]. The mediator variable is

social connectedness, the degree to which individuals feel connected to people in their social relationships [

28].

Undoubtedly, a favorable environmental attitude is essential; however, many studies have shown that it does not automatically translate into sustainable behavior [

29,

30]. Many factors that can potentially bridge the gap between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior have been studied, particularly psychological factors like knowledge and concern [

11,

27], as well as social factors like social norms and interpersonal communication [

31,

32]. However, there is a dearth of research about the mediating role of social connectedness in this relationship.

As humanity develops, there is a need to guide our behavioral patterns, consumption habits, and lifestyles to make sure that we satisfy our needs without impairing the future generation’s ability to satisfy their own. Studies that analyze factors that affect individuals' engagement with sustainable behaviors are essential to promote sustainability. This study can potentially generate knowledge about the predictors of sustainable behaviors among individuals. Additionally, it can inform policies, intervention programs, and other strategies for promoting sustainable behaviors.

The main purpose of this study is to examine how social connectedness mediates the relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior among university students. In particular, this study intends to accomplish the following research objectives: (1) ascertain the level of students’ environmental attitude, sustainable behavior, and social connectedness; (2) ascertain whether there is a significant relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior, environmental attitude and social connectedness, and social connectedness and sustainable behavior; and (3) ascertain whether social connectedness mediates the relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior. Furthermore, the study aligns with three of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) outlined by the United Nations, particularly SDG4 (Quality Education), SDG12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG13 (Climate Action).

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at one of the private higher education institutions in Davao City, Philippines. It employed the

stratified random sampling technique, which is typically used when analyzing data from multiple subgroups of a population [

33]. The total population of undergraduate students was divided into subgroups based on their respective colleges. In addition, inclusion criteria were taken into account: (1) the respondent must be a bonafide student of the university; (2) the respondent must be an undergraduate student from one of the colleges of the university; (3) the respondent must be enrolled in the second semester of the academic year 2024-2025; and (4) the respondent must have the willingness to participate in the study.

The study gathered a total of 378 respondents from the nine colleges of the university. In particular, 35 respondents were gathered from the College of Accounting Education, 33 from the College of Architecture and Fine Arts Education, 45 from the College of Arts and Sciences Education, 43 from the College of Computing Education, 42 from the College of Criminal Justice Education, 88 from the College of Engineering Education, 34 from the College of Hospitality Education, 30 from the College of Health Sciences Education, and 28 from the College of Teacher Education. Additionally, the total sample size was determined using the Raosoft sample size calculator with a 5% margin of error.

To gather quantitative data for the study, the researchers utilized three sets of adapted questionnaires that were validated and tested for reliability by a pool of experts in questionnaire design. The questionnaire used to assess the level of environmental attitude was adapted from

New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale by Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, and Jones [

34]. It has five indicators:

the reality of limits to growth,

anti-anthropocentrism,

the fragility of nature’s balance,

rejection of exemptionalism, and

the possibility of an eco-crisis. Its

Cronbach’s alpha was found to be .765, which means it has an acceptable reliability. Additionally, even-numbered items are negative and were scored in reverse.

The questionnaire used to assess the level of sustainable behavior was adapted from

Identifying Sustainable Population Segments Using a Multi-Domain Questionnaire: A Five Factor Sustainability Scale by Haan, Konijn, Burgers, Eden, Brugman, and Verheggen [

35]. It has five indicators: sustainability

in general,

household,

consumption,

mobility, and

nature. It has excellent reliability, with a

Cronbach’s alpha of .906. In addition, items 8, 9, 13, 17, 25, and 30 are negative and were scored in reverse.

The questionnaire used to assess the level of social connectedness was adapted from

Measuring Belongingness: The Social Connectedness and the Social Assurance Scales by Lee and Robbins [

36]. Its

Cronbach’s alpha was found to be .919, meaning it has excellent reliability. In addition, all items are negative and were scored in reverse.

The modified questionnaire used a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from 5 – Strongly Agree to 1 – Strongly Disagree. A rating of 5, which equates to Strongly Agree, indicates that the respondent completely agrees with the statement. A rating of 4, which equates to Agree, indicates that the respondent partially agrees with the statement. A rating of 3, which equates to Neutral, indicates that the respondent neither agrees nor disagrees with the statement. A rating of 2, which equates to Disagree, indicates that the respondent partially disagrees with the statement. A rating of 1, which equates to Strongly Disagree, indicates that the respondent completely disagrees with the statement.

To interpret the respondents' levels of environmental attitude, sustainable behavior, and social connectedness, the mean scores were calculated and interpreted using the following scale: a mean score ranging from 4.20 to 5.00 indicates a very high level; 3.40 to 4.19 indicates a high level; 2.60 to 3.39 indicates a moderate level; 1.80 to 2.59 indicates a low level; and 1.00 to 1.79 indicates a very low level.

The researchers employed the

descriptive-correlational research design for the study. This design is non-experimental, which means that the relationship between the variables was investigated without any manipulation by the researchers [

37]. The steps that were taken to gather the data are as follows: the questionnaire was validated, and permission was obtained from the deans of the respective colleges to conduct the data-gathering procedure. A pilot test was conducted to calculate the

Cronbach's alpha for each item to test the reliability of the questionnaire before conducting the formal data-gathering procedure. After completing the formal data-gathering procedure, the completed survey questionnaires were tabulated and analyzed using statistical tools appropriate for data interpretation.

Mean was used to determine the level of environmental attitude, sustainable behavior, and social connectedness among university students. In addition,

Pearson's r was used to determine the significance of the relationship between the variables.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the analysis on university students' levels of environmental attitude, sustainable behavior, and social connectedness, as well as the significance of the relationships among these variables.

3.1. Environmental Attitude

Table 1 shows the level of students' environmental attitude in terms of

the reality of limits to growth,

anti-anthropocentrism,

the fragility of nature’s balance,

rejection of exemptionalism, and

the possibility of an eco-crisis. Data reveal that the level of environmental attitude among university students is

moderate (

M = 3.30;

SD = .361). This indicates that the collection of beliefs, values, and behavioral intentions they hold regarding environment-related activities or issues is moderately positive. Additionally, among the indicators,

the possibility of an eco-crisis has the highest mean (

M = 3.77;

SD = .573). This translates to

high, which means that they believe that humans are severely abusing the environment and will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe if this continues. This is followed by

the fragility of nature’s balance (

M = 3.52;

SD = .500), which also translates to

high, which means that they believe that nature’s balance is very delicate, and human interference leads to disastrous consequences.

Furthermore, the indicators that obtained a moderate level of environmental attitude are anti-anthropocentrism (M = 3.25; SD = .717), the reality of limits to growth (M = 3.04; SD = .615), and rejection of exemptionalism (M = 2.97; SD = .448). Students being moderately pro-environmental in terms of anti-anthropocentrism means that they partially believe that humans do not rule over the rest of nature and that plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. Additionally, students being moderately pro-environmental in terms of the reality of limits to growth means that they partially believe that the Earth has limited resources, and it is approaching the limit of the number of people it can support. Moreover, students being moderately pro-environmental in terms of the rejection of exemptionalism means that they partially believe that, despite human ingenuity, we are subject to the laws of nature.

3.2. Sustainable Behavior

Table 2 shows the level of students' sustainable behavior in terms of sustainability

in general,

household,

consumption,

mobility, and

nature. Data reveal that the level of sustainable behavior among university students is

high (

M = 3.43;

SD = .455). This indicates that their deliberate actions to satisfy their present needs are done with consideration of their environmental impact. Additionally, among the indicators, sustainability in

nature obtained the highest mean (

M = 3.60;

SD = .706). This translates to

high, which means that students’ behavior towards nature is highly sustainable. They work on reducing their impact on nature and participate in activities that aim to preserve it. This is followed by sustainability in the

household (

M = 3.59;

SD = .517), which also translates to

high. This means that students’ behavior in the household is highly sustainable. They engage in energy-saving practices and proper segregation of waste at home. Next is sustainability

in general (

M = 3.55;

SD = .686), which also translates to

high, which means that students are highly sustainable with their actions in general. They incorporate sustainability into their lifestyle and encourage the people around them to live sustainably.

Furthermore, the indicators that registered a moderate level of sustainable behavior are consumption (M = 3.35; SD = .549) and mobility (M = 3.08; SD = .535). This means that students' behavior in terms of consumption and mobility is moderately sustainable. Students being moderately sustainable in consumption means that they sometimes engage in sustainable consumption practices such as buying sustainable products and recycling materials. Moreover, students being moderately sustainable in mobility means that they sometimes follow sustainable mobility patterns such as using public transportation, walking, and cycling.

3.3. Social Connectedness

Table 3 shows the level of university students’ social connectedness. Data reveal that the level of social connectedness among university students is

high (

M = 3.45;

SD = .934). This indicates that students are highly socially connected. The degree to which they experience belonging, togetherness, or entrenchment in their social relationships is high.

3.4. Correlation Between Environmental Attitude and Sustainable Behavior

Presented in

Table 4 is the

Pearson’s correlational analysis between students’ environmental attitude and sustainable behavior. Data reveal that there is no significant relationship between the two variables (

r = .061;

p = .235). There appears to be a disconnect between what students believe and feel about the environment and how they behave in it. Additionally, although students reported only a moderate level of environmental attitude, they exhibited a high level of sustainable behavior. This discrepancy implies that other, potentially more influential factors beyond attitude may be motivating their sustainable actions.

3.5. Correlation Between Environmental Attitude and Social Connectedness

Presented in

Table 5 is the

Pearson’s correlational analysis between students’ environmental attitude and social connectedness. Data reveals that there is no significant relationship between the two variables (

r = .071;

p = .093). This suggests that students who possess a positive outlook on the environment do not necessarily feel a deeper sense of connection with other people. It can also be implied that experiencing a stronger sense of belonging within social relationships does not influence the attitude that one holds toward the environment.

3.6. Correlation Between Social Connectedness and Sustainable Behavior

Presented in

Table 6 is the

Pearson’s correlational analysis between students’ social connectedness and sustainable behavior. Data reveal that there is no significant relationship between the two variables (

r = .050;

p = .333). This suggests that the degree to which students feel socially connected does not significantly influence whether they engage in sustainable practices.

3.7. Mediation Analysis of the Three Variables

The researchers intended to employ mediation analysis to determine whether social connectedness mediates the relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior. However, this method could not be performed due to the lack of a statistically significant relationship between the variables. Given this, the researchers conclude that social connectedness does not mediate the relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior, a relationship which, based on their correlational analysis, is also nonexistent. This implies that students who hold an environmentally responsible attitude do not necessarily feel a deeper sense of connection with other people, which helps translate their pro-environmental attitude into sustainable behavior.

4. Discussion

The findings about the level of university students’ environmental attitude align with the findings of AL-Tkhayneh and Ashour [

38], who claimed that university students exhibit a moderate level of environmental attitude. Additionally, the findings partially conform to those of Li et al. [

39] and Sousa et al. [

40], who revealed that students’ level of environmental attitude is high. They claimed that students have a positive attitude toward environmentally friendly practices and recognize that Earth's resources are finite. On the other hand, the findings contradict those of Arshad et al. [

41], who revealed that university students' level of environmental attitude is significantly low. They reported that students believe that humans are more important than other beings and have the right to modify the environment according to their needs.

Furthermore, the results obtained for the level of university students’ sustainable behavior align with the findings of Wardhana [

42], who revealed that university students exhibit a high level of sustainable behavior. Proper waste disposal, energy and resource-saving practices, and the use of eco-friendly products are among their most common practices. Additionally, the findings are partially aligned with those of Kirby and Zwickle [

43], who revealed that students tend to cut back on driving, limit meat consumption, and responsibly use electronics. On the other hand, the results oppose the findings of Wendlandt Amézaga et al. [

44], who revealed a low level of sustainable behavior among students. Their findings revealed that students do not consider the impact of their daily activities on the environment.

Moreover, the findings about university students’ level of social connectedness align with existing studies [

45,

46], which revealed that university students have a high level of social connectedness. They experience strong connections with people within their social networks, including their family, friends, classmates, instructors, and the university community. Additionally, university students often feel valued, trusted, respected, and cared for by their classmates, friends, professors, and family [

47].

Moving forward, the result of the correlational analysis between students’ environmental attitude and sustainable behavior fails to reject the null hypothesis, which states that there is no significant relationship between the two variables. This contradicts the

Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Stern et al. [

17], which suggests that sustainable behavior occurs when positive values, beliefs, and personal norms are present. On the other hand, these findings align with those of Aguilar and Olayta [

48], who revealed that while students possess a positive attitude toward solid waste management and the responsible purchase and use of products, they lack actual engagement in these environmentally friendly practices. Similarly, Bashirun et al. [

49] found that despite students’ positive attitudes toward recycling, only a small number of them actively engage in it, and most do so rarely. Additionally, Teather and Etterson [

50], in their discussion of the

value-action gap, demonstrated that although students held positive attitudes toward sustainability principles, they were less likely to act on these values.

Furthermore, the result of the correlational analysis between students’ environmental attitude and social connectedness fails to reject the null hypothesis, which states that there is no significant relationship between the two variables. This challenges the

Social Identity Theory of Tajfel and Turner [

20], which suggests that individuals may identify themselves as members of one social group with others who have the same attitudes as them, which fosters social connectedness. However, this result aligns with that of Kesenheimer and Greitemeyer [

51], who found that individuals with pro-environmental attitudes primarily care about environmental issues but are not more pro-social in general. In contrast, Drosinou et al. [

52] reported that individuals who felt more connected to others expressed greater concern for biospheric issues. Additionally, Lee et al. [

53] demonstrated that the perceived influence of social ties significantly enhances both positive attitudes toward recycling and the intention to engage in actual recycling behavior.

Moreover, the result of the correlational analysis between students’ social connectedness and sustainable behavior fails to reject the null hypothesis, which states that there is no significant relationship between the two variables. This negates the

Self-Determination Theory of Deci and Ryan [

24], which claims that when individuals satisfy their

relatedness needs, engagement in favorable behaviors increases. On the contrary, the result aligns with that of Clark [

28], who reported that social connectedness has no significant relationship with the level of sustainable behavior. Students who are socially connected were not significantly more pro-environmental than the socially excluded ones in terms of behavior. However, other studies [

25,

26] revealed that an increased sense of connectedness to other people results in environmentally sustainable behavior. Students who experience a stronger connection with others are more concerned about the environment, fostering environmentally friendly practices.

Overall, the results fail to reject the null hypothesis, which states that social connectedness does not mediate the relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior. These findings contradict the integrated

Attitude-Behavior-Context (ABC) Theory of Stern [

14], which claims that the interaction of attitudinal variables and contextual factors determines the contingency of an environmentally favorable behavior. These challenge the findings of Xing et al. [

16], who argued that collective social bonds within a society encourage individuals to translate their environmental attitudes into practical actions. It also has implications for claims that attitudinal and social factors have complex and dynamic connections that predict sustainable behavior [

15]. Nevertheless, the findings support the assertions of Wintschnig [

54], who emphasized the need for more extensive studies to better understand the influence of social factors in addressing the discrepancy between people’s attitudes toward sustainable practices and the extent to which they act on them.

The overall findings challenge the established theories that served as the framework for the study. It suggests that although these theories have previously explained the associations among the variables, and earlier research may have supported such links, the relationships may be influenced by contextual factors and could apply only to specific populations, demographic groups, settings, or periods. For this reason, the researchers recommend that future studies revisit the theoretical framework used in the study and explore alternative theories that may more effectively explain the relationships among the variables.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the study revealed that university students' level of environmental attitude is moderate, while their levels of sustainable behavior and social connectedness are high. The study also found no significant relationship between students' environmental attitudes, sustainable behavior, and social connectedness. Furthermore, the lack of a significant relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior indicates that social connectedness does not serve as a mediating variable between the two. The results led the researchers to disprove the theoretical assumptions of the study: social connectedness mediates the relationship between environmental attitude and sustainable behavior. This implies that students’ attitudes toward the environment do not influence the degree to which they are connected with people within their social relationships in a way that subsequently results in sustainable behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.; methodology, K.M.A. and P.S.B.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.; writing—review and editing, G.P.; supervision, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the following individuals and institutions for their invaluable support and contributions to the completion of this research study: Dr. Christian Jay O. Syting, our Research 1 instructor, for imparting foundational knowledge that guided the initial stages of this study; Dr. Melissa C. Napil, our research coordinator and panelist, for rigorously reviewing our paper to ensure its quality; Sir Mark John T. Pepito, our panelist, for his constructive feedback and suggestions that significantly enhanced the quality of our work; Sir Lloyd Psyche T. Baltazar, our statistician, for his expertise in statistical analysis and assistance in interpreting our data; the Department of Science and Technology – Science Education Institution (DOST - SEI) and the DOST Regional Office XI, for their generous support in making this study possible; our families and friends, for their unwavering belief in us, and their encouragement, emotional and moral support; and above all, to the Almighty God, for guiding us from the beginning to the successful completion of this study. This endeavor would not have been possible without the wisdom, strength, and grace He has bestowed upon us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Islam, Q., & Ali Khan, S. M. F. (2024). Assessing consumer behavior in sustainable product markets: A structural equation modeling approach with partial least squares analysis. Sustainability, 16(8) 3400. [CrossRef]

- Klaniecki, K., Wuropulos, K., & Hager, C. P. (2019). Behavior change for sustainable development. In Encyclopedia of sustainability in higher education (pp. 85-94). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Grilli, G., & Curtis, J. (2021). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: A review of methods and approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 135, 110039. [CrossRef]

- Hirschmann, R. (2024, May 29). Leading reasons for not adopting sustainable habits in Singapore as of June 2021: Main reasons for not adopting sustainable habits in Singapore 2021. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1312723/singapore-reasons-for-not-adopting-sustainable-habits/#statisticContainer.

- Genovese, E. (2022). University student perception of sustainability and environmental issues. AIMS Geosciences, 8(4), 645-657. [CrossRef]

- Nahar, N., Mahiuddin, S., & Hossain, Z. (2021). The severity of environmental pollution in the developing countries and its remedial measures. Earth, 2(1), 124-139. [CrossRef]

- Eini-Zinab, H., Shoaibinobarian, N., Ranjbar, G., Norouzian Ostad, A., & Sobhani, S. R. (2021). Association between the socio-economic status of households and a more sustainable diet. Public health nutrition, 24(18), 6566–6574. [CrossRef]

- Peleg-Mizrachi, M., & Tal, A. (2019). Caveats in environmental justice, consumption and ecological footprints: The relationship and policy implications of socioeconomic rank and sustainable consumption patterns. Sustainability, 12(1), 231. [CrossRef]

- Never, B., & Albert, J. R. G. (2021). Unmasking the middle class in the Philippines: Aspirations, lifestyles and prospects for sustainable consumption. Asian Studies Review, 45(4), 594–614. [CrossRef]

- Montebon, D., Gonzaga, M., Delos Santos, V., & Ginez, J. (2022). Sustainability and gender in select filipino households. Journal Of Community Development Research (Humanities And Social Sciences), 15(4), 125-140. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M., & Gomes, S. (2023). What role does sustainable behavior and environmental awareness from civil society play in the planet’s sustainable transition. Resources, 12(3), 42. [CrossRef]

- Mastria, S., Vezzil, A., & De Cesarei, A. (2023). Going green: A review on the role of motivation in sustainable behavior. Sustainability, 15(21), 15429. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A., & Richardson, M. (2022). The relationship between nature connectedness and human and planetary wellbeing: Implications for promoting wellbeing, tackling anthropogenic climate change and overcoming biodiversity loss. In: Kemp, A.H., Edwards, D.J. (eds) Broadening the Scope of Wellbeing Science. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of social issues, 56(3), 407-424. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. A., & Kingston, S. (2021). Demographic, attitudinal, and social factors that predict pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability and Climate Change, 14(1), 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y., Li, M., & Liao, Y. (2022). Trust, identity, and public-sphere pro-environmental behavior in China: an extended attitude-behavior-context theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 919578. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human ecology review, 81-97.

- Tian, H., Zhang, J., & Li, J. (2020). The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: the role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(7), 7341-7352. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. S., Saengon, P., Alganad, A. M. N., Chongcharoen, D., & Farrukh, M. (2020). Consumer green behaviour: An approach towards environmental sustainability. Sustainable Development, 28(5), 1168-1180. [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political psychology (pp. 276-293). Psychology Press.

- McLeod, S. (2023, October 5). Social identity theory in psychology (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html.

- Petersen, E., Fiske, A. P., & Schubert, T. W. (2019). The role of social relational emotions for human-nature connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 498311. [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S. A. (2019). Social identity and environmental concern: The importance of contextual effects. Environment and Behavior, 51(7), 828-855. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology, 1(20), 416-436.

- Triantafyllidis, S., & Darvin, L. (2021). Mass-participant sport events and sustainable development: Gender, social bonding, and connectedness to nature as predictors of socially and environmentally responsible behavior intentions. Sustainability science, 16(1), 239-253. [CrossRef]

- van Hoepen, M. A. (2020). The interplay of social comparison, social connectedness and environmental concern and how gender moderates these effects (Bachelor's thesis).

- Vieira, J., Castro, S. L., & Souza, A. S. (2023). Psychological barriers moderate the attitude-behavior gap for climate change. PLOS ONE, 18(7), e0287404. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. (2021). Does social connectedness increase pro-environmental behaviour? The Plymouth Student Scientist, 14(1), 529-544. https://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/17323. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Shen, M., & Chu, M. (2021). Why is green consumption easier said than done? Exploring the green consumption attitude-intention gap in China with behavioral reasoning theory. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 2, 100015. [CrossRef]

- Wyss, A. M., Knoch, D., & Berger, S. (2022). When and how pro-environmental attitudes turn into behavior: The role of costs, benefits, and self-control. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 79, 101748. [CrossRef]

- Han, R., & Xu, J. (2020). A comparative study of the role of interpersonal communication, traditional media and social media in pro-environmental behavior: A China-based study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6). [CrossRef]

- Perry, G. L., Richardson, S. J., Harré, N., Hodges, D., Lyver, P. O., Maseyk, F. J., Taylor, R., Todd, J. H., Tylianakis, J. M., Yletyinen, J., & Brower, A. (2021). Evaluating the role of social norms in fostering pro-environmental behaviors. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 9, 620125. [CrossRef]

- Hossan, D., Dato’Mansor, Z., & Jaharuddin, N. S. (2023). Research population and sampling in quantitative study. International Journal of Business and Technopreneurship (IJBT), 13(3), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Mertig, A. G., & Jones, R. E. (2000). New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: a revised NEP scale. Journal of social issues, 56(3), 425-442.

- Haan, M., Konijn, E. A., Burgers, C., Eden, A., Brugman, B. C., & Verheggen, P. P. (2018). Identifying sustainable population segments using a multi-domain questionnaire: A five factor sustainability scale. Social Marketing Quarterly, 24(4), 264-280. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of counseling psychology, 42(2), 232. [CrossRef]

- Kumatongo, B., & Muzata, K. K. (2021). Research paradigms and designs with their application in education. Journal of Lexicography and Terminology (Online ISSN 2664-0899. Print ISSN 2517-9306)., 5(1), 16-32.

- AL-Tkhayneh, K. M., & Ashour, S. (2024). The green generation: a survey of environmental attitudes among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Yang, D., & Liu, S. (2024). The impact of environmental education at Chinese Universities on college students’ environmental attitudes. Plos one, 19(2), e0299231. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S., Correia, E., Leite, J., & Viseu, C. (2021). Environmental knowledge, attitudes and behavior of higher education students: a case study in Portugal. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 30(4), 348-365. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, H. M., Saleem, K., Shafi, S., Ahmad, T., & Kanwal, S. (2020). Environmental awareness, concern, attitude and behavior of university students: A comparison across academic disciplines. Polish journal of environmental studies, 30(1), 561-570. [CrossRef]

- Wardhana, D. Y. (2022). Environmental awareness, sustainable consumption and green behavior amongst university students. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 11, 242-252.

- Kirby, C. K., & Zwickle, A. (2021). Sustainability behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge: comparing university students and the general public. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 11(4), 639-647. [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt Amézaga, T. R., Camarena, J. L., Celaya Figueroa, R., & Garduño Realivazquez, K. A. (2022). Measuring sustainable development knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors: evidence from university students in Mexico. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(1), 765-788. [CrossRef]

- Olusegun-Emmanuel, F. (2023). Social connectedness and its relation to perceived stress and loneliness [Honours Thesis, Western University]. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/brescia_psych_uht/46.

- Su, N., & Wang, H. P. (2022). The influence of students’ sense of social connectedness on prosocial behavior in higher education institutions in Guangxi, China: A perspective of perceived teachers’ character teaching behavior and social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1029315. [CrossRef]

- Andrada, A. B., & Doromal, A. C. (2024). Social Connectedness among Emerging Adults in a State University in Western Visayas. Technium Soc. Sci. J., 58, 142. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, M. G. W., & Olayta, J. N. (2023). Environmental attitudes versus behavior of tourism management students: A basis for educational planning and development. Journal of Educational Studies, 5(2), 97-126.

- Bashirun, S. N., Razali, M., & Abdul Rahman, A. H. (2023). Environmental attitude and behaviour among students: Incorporating the green concept in learning outcome based. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 10(6.2), 16-24. [CrossRef]

- Teather, A., & Etterson, J. (2023). Value-action gaps between sustainability behaviors, knowledge, attitudes and engagement in campus and curricular activities within a cohort of Gen Z university students. The Journal of Sustainability Education.

- Kesenheimer, J. S., & Greitemeyer, T. (2021). Going green (and not being just more pro-social): do attitude and personality specifically influence pro-environmental behavior?. Sustainability, 13(6), 3560. [CrossRef]

- Drosinou, M., Palomäki, J., Jokela, M., & Laakasuo, M. (2025). Everything is connected: Reminders of environmental and social connectedness strengthen environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 102549. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. R., Hon, L., Won, J., You, L., Oloke, T., & Kong, S. (2020). The role of psychological proximity and social ties influence in promoting a social media recycling campaign. Environmental communication, 14(4), 431-449. [CrossRef]

- Wintschnig, B. A. (2021). The attitude-behavior gap–drivers and barriers of sustainable consumption. Junior Management Science (JUMS), 6(2), 324-346. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).