1. Introduction

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rate in Japan remains significantly lower than in other developed countries, making improved coverage an urgent public health concern. Although routine, publicly funded HPV immunization was introduced in 2013, media reports of adverse events such as pain and motor dysfunction prompted the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare to halt its active promotion of the vaccine later that year [

1,

2]. This decision led to a drastic decline in vaccination rates from an initial 70% at the start of the program to less than 1% [

3]. Subsequent reviews by the Health Sciences Council, based on domestic and international studies, found no clear evidence of a causal relationship between the reported adverse events and the HPV vaccine [

2]. Consequently, proactive recommendations for routine vaccination of girls aged 12 to 16 years resumed in April 2022 [

4]. However, in 2022, the HPV vaccination rate for the first dose remained at just 42.2%, which is still inadequate [

5].

Internationally, there has been progress in recommending HPV vaccination for both males and females. In the United States, reports suggest that more than 90% of cervical and anal cancers, and 63–75% of penile, vulvar, vaginal, and oropharyngeal cancers are caused by HPV [

6,

7]. Another study suggests that the acquisition of HPV is common among males, with patterns similar to those in females [

8]. A systematic review also supports early vaccination of boys before the onset of sexual activity [

9]. According to a survey by World Health Organization (WHO), at least 39 countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, and France, have implemented publicly funded HPV vaccination programs for males [

10]. Vaccinating males helps prevent conditions such as genital warts, anal cancer, and oropharyngeal cancer, and also contributes to herd immunity, thereby reducing HPV infection rates among females. In contrast, in Japan, HPV vaccination for boys aged 9 years and older is generally available only on a self-pay basis, except in a few municipalities. The high cost—approximately 20,000 yen per dose, or 50,000–60,000 yen for the full three-dose series—acts as a barrier, limiting the number of individuals seeking vaccination [

11]. Discussions on routine vaccination for males have only recently begun in Japan. Additionally, HPV vaccination recommendations are being expanded to include special populations, such as childhood cancer survivors [

12], men who have sex with men, and immunocompromised individuals [

13].

In Japan, HPV vaccination behavior is influenced by the Immunization Act, which requires parental consent for individuals under 15 years old to be vaccinated [

14]. As a result, parental decision-making plays a significant role in vaccine uptake. Previous studies in Japan have shown that approximately 90% of junior high school girls who received the HPV vaccine cited their mothers’ opinions as the most influential factor in their decision [

15], highlighting the strong impact of parental influence. Additionally, parental explanations about HPV vaccination have been identified as key factors associated with children’s willingness to receive the vaccine [

16]. Although target populations and vaccination rates vary across countries and regions, global studies have examined the factors related to parents’ willingness to vaccinate. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 79 studies from 15 countries reported that factors positively influencing parents’ decisions included general vaccine beliefs, perceived benefits, awareness of risks from non-vaccination, and knowledge of HPV and cervical cancer [

17]. Other studies have also found associations between mothers’ knowledge of HPV infection and vaccination [

18,

19,

20,

21], as well as their knowledge of cervical cancer [

19], and their willingness to vaccinate their children. Conversely, low levels of knowledge have been linked to prejudice and hesitancy regarding vaccination [

22,

23]. However, some studies have reported no significant association between parental knowledge and actual vaccination uptake among adolescents [

24]. Notably, the definitions and measures of HPV-related knowledge varies across these studies.

Providing parents with accurate information about the benefits of the vaccine may facilitate informed decision-making and encourage initiation and completion of the full HPV vaccine series [

25]. In Japan, although various studies have examined factors influencing parental decisions, most were conducted before the reinstatement of proactive vaccination, and there is limited research on decision-making and knowledge dissemination since then. Japan’s unique history with HPV vaccine introduction may affect how parents acquire and interpret information, highlighting the need for a scientifically validated scale to measure HPV vaccine knowledge. Understanding current knowledge levels and identifying information gaps are essential for designing effective educational initiatives to increase HPV vaccination rates. Therefore, we developed an HPV knowledge scale and evaluated its reliability and validity to support practical application in public health and education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Items for the HPV Knowledge Scale

In Japan, no validated and reliable knowledge scale on HPV and HPV vaccination currently exits. Internationally, however, several such scales have been developed [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], among which the HPV Knowledge Scale (HPV-KS), created by Waller et al. in 2013, has been widely used in studies HPV-related research [

29].

The original HPV-KS consists of three subscales: general HPV knowledge (16 items), HPV testing knowledge (6 items), and HPV vaccination knowledge (7 items), totaling 29 items. Each item is uses a three-option response format: “True,” “False,” or “Don’t know.” Correct responses are scored as 1 point, while incorrect or “Don’t know” answers receive 0 points. Higher total scores indicate greater knowledge. Th scale was developed and validated using data from a survey of 2,409 men and women in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, and has demonstrated high reliability and validity.

In Japan, cervical cancer screening using cytology is recommended once every two years for individuals aged 20 years and older, but the inclusion of routine HPV testing remains under discussion [

31]. For this study, we adopted two of the three original subscales: general HPV knowledge and HPV vaccination knowledge. The general HPV knowledge subscale showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.849. The HPV vaccination knowledge subscale had a relatively low Cronbach’s alpha of 0.561; although removing the item “HPV can cause HIV/AIDS” might improve the scale’s internal consistency, it was retained due to its perceived importance in previous research [

32], and we chose to retain it as well. Permission to use only the two subscales was obtained from the original author. (

Table 1)

2.2. Additional Questions

To address issues specific to HPV vaccination in Japan, particularly long-standing public concerns over vaccine side effects, three additional items (Q27–Q29) were added. To highlight the risks of HPV-related diseases in both males and females beyond genital warts, three more items (Q17–Q19) were included. In total, six new items were incorporated, resulting in a final 29-item scale. (

Table 1)

2.3. Translation

The original scale was translated from English into Japanese by a university faculty member specializing in nursing and midwifery along with graduate students proficient in English. Care was taken to preserve the original meaning, while ensuring the language was natural and easily understandable for Japanese respondents. A panel consisting of the principal investigator, research collaborators (including an obstetrician-gynecologist), and graduate students reviewed the translated version for content validity. Based on their feedback, a preliminary draft was created and further refined through discussions between the principal investigator and research collaborator.

Special attention was given to five items from the original scale: “Girls who have the HPV vaccine do not need a smear test when they are older,” “HPV can cause genital warts,” “HPV can be cured with antibiotics,” “One of the HPV vaccines offers protection against genital warts,” and “The HPV vaccine requires three doses.” These were carefully adjusted to ensure natural and culturally appropriate wording in Japanese. Additionally, the item “HPV can be passed on by genital skin-to-skin contact,” was translated more broadly to avoid overly narrow interpretations of the terms “genital” or “skin.”

2.4. Back-Translation

To ensure the accuracy and conceptual equivalence of the translated scale, a back-translation was conducted by Crimson Interactive Japan, Inc. [

33], a professional academic English editing service. In this process, a native Japanese translator who had no access to the original English version, translated the Japanese version back into English. A third-party reviewer then compared the original and back-translated versions, focusing on terminology, expressions, and subtle nuances. This evaluation confirmed that the translated scale accurately conveyed the concepts and meanings of the original. Additionally, the principal investigator and research collaborators reviewed both versions to verify the appropriateness of the wording for each item.

2.5. Cognitive Debriefing

To confirm the clarity and comprehensibility of the translated scale, cognitive debriefing was conducted with eleven graduate students. They completed the translated version, and their understanding of each item was assessed. Based on their feedback, the research team reviewed the responses and confirmed the appropriateness of the item wording.

2.6. Participants

Between April and August 2024, the study targeted parents or guardians of all students enrolled at six junior high schools in two cities and two towns in Prefecture A, Japan, where research cooperation was obtained. As of April 1, 2024, these students had received HPV vaccination vouchers distributed by the end of March, making them eligible for publicly funded vaccination. This consistent eligibility formed the basis for selecting their parents or guardians as the study population.

Although previous studies have primarily focused on mothers, research including parents or guardians more broadly is limited. This study aimed to identify individuals involved in decision-making regarding their child’s HPV vaccination, and thus defined the target population as “parents or guardians.”

2.7. Study Procedure

An anonymous web-based questionnaire survey was employed. After obtaining approval from the principals of each school, a research information sheet containing a Quick Response (QR) code and URL for the survey was distributed to students by their homeroom teachers, with instructions to deliver it to their parents or guardians. For parents or guardians with multiple children enrolled in junior high school, the instructions specified that responses should be based on their eldest child.

Participants who consented to participate in the test-retest reliability assessment received a follow-up questionnaire via email two weeks after completing the initial survey.

The web-based questionnaire was developed and administered using Google Forms, a form-creation tool provided by Google Cloud Japan LLC [

34].

2.8. Data Analysis

Parallel and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.1, whereas all other analyses were performed using IBM® Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics for Windows, version 28.0. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.9. Validity Assessment of the Scale

To assess the sampling adequacy for factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted. Construct validity, specifically factor validity, was examined through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with the maximum likelihood method and Promax rotation. The number of factors was determined based on Guttman’s criterion and parallel analysis [

35].

Items were retained if they had a factor loading of ≥ 0.40 on a single factor and no cross-loadings of ≥ 0.40 on multiple factors. Items with communality values ≥ 0.16 were also retained.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was subsequently conducted to validate the factor structure derived from the EFA. Model fit was assessed using the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

2.10. Reliability Assessment of the Scale

Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Test-retest reliability, reflecting the scale’s stability over time, was examined by calculating Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between total scores from the first and second administrations. Item-total correlations were also to assess the relationship between each item and the overall score.

2.11. Ethical Considerations

For both the initial and follow-up surveys, a research information sheet was provided on the webpage hosting the online questionnaire. Participants were instructed to read the information carefully before beginning the survey and were free to decline participation. This approach ensured informed consent.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kagawa University Faculty of Medicine (Approval Number: 2024-009).

3. Results

A total of 2,828 study information sheets were distributed, and 851 responses were received (response rate, 30.1%). Of these, 793 responses (93.2%) were valid. The average age of participants was 44.2 years, and 93.1% were mothers. The gender distribution of participants’ children was 401 girls (50.6%) and 392 boys (49.4%).

3.1. Validity Analyses

Guttman’s criterion and parallel analysis suggested a five-factor structure. Of the initial 29 items, 12 did not meet the threshold for factor loadings and were excluded. EFA using the maximum likelihood method with Promax rotation was conducted, assuming a five-factor structure (

Table 2).

In the first round, items 1, 2, 4, 10, 11, 12, 14, 24, 25, and 26 had factor loadings below 0.40 and were removed. A second EFA excluded items 6 and 8 for the same reason.

A final EFA was then conducted on the remaining 17 items, all of which showed factor loadings above 0.40. Sampling adequacy was confirmed by a KMO value of 0.870, indicating a “very good” level of correlation. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also significant (χ² = 4833.5, p < 0.001), supporting the suitability of the data for factor analysis.

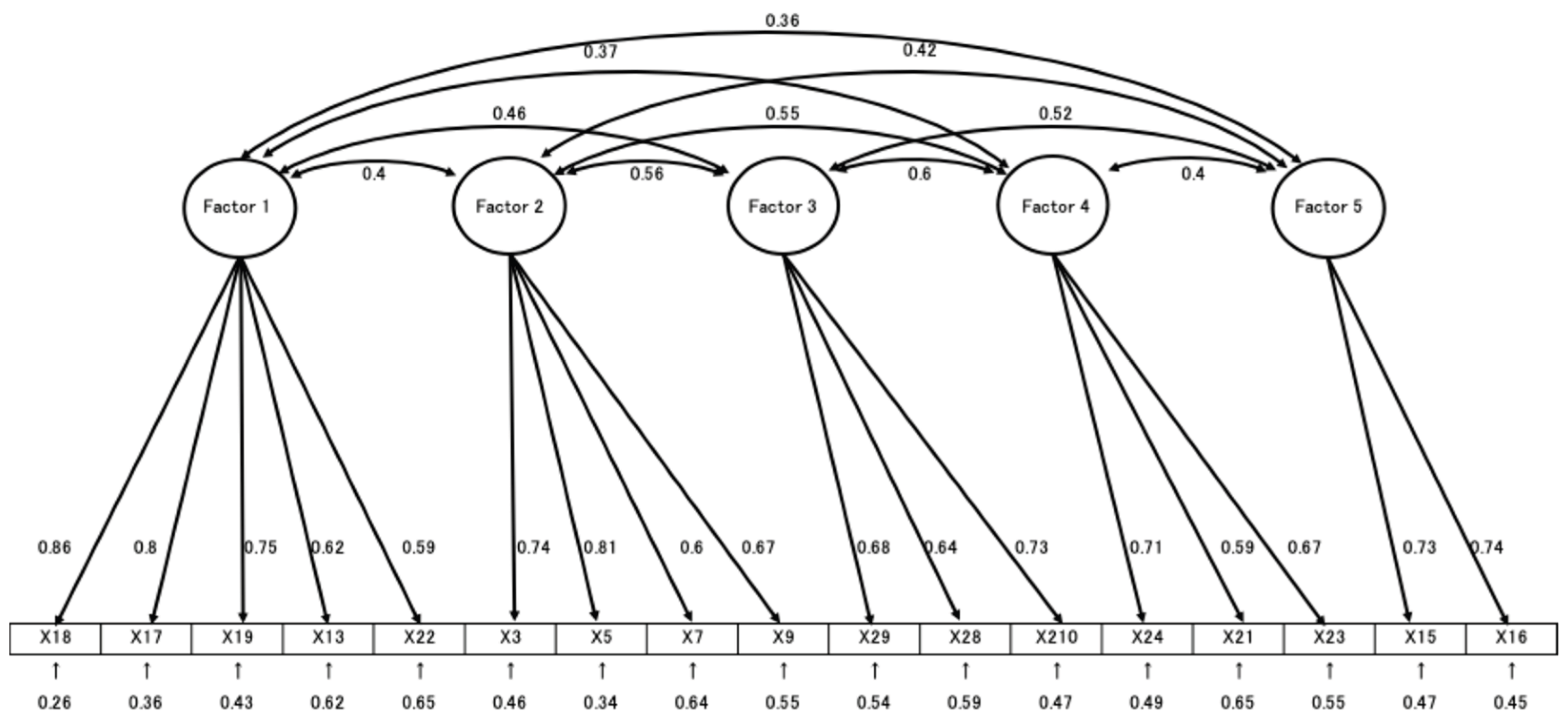

The EFA identified five distinct factors: Factor 1, labeled “Risk of HPV-related diseases and their prevention,” including items 18, 17, 19, 13, and 21 with factor loadings ranging from 0.424 to 0.896; Factor 2, “Transmission pathways of HPV and its prevention,” with items 3, 5, 7, and 9, and factor loadings between 0.530 and 0.821; Factor 3, “Evaluation of HPV vaccine safety and efficacy,” including items 28, 27, and 29, with loadings from 0.576 to 0.737; Factor 4, “Limitations of HPV vaccine efficacy,” including items 20, 22, and 23, with loadings from 0.565 to 0.813; and Factor 5, “HPV infection risk and its natural course,” including items 15 and 16, with loadings ranging from 0.710 to 0.790.

CFA was performed to validate the factor model derived from EFA (

Figure 1). Model fit indices indicated good fit: GFI = 0.934, AGFI = 0.907, CFI = 0.928, and RMSEA = 0.063. In total, 17 items were retained and included in the final version of the scale.

3.2. Reliability Analyses

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire 17-item scale was 0.868, indicating good internal consistency. Among the individual factors, Factor 4 had a slightly lower alpha of 0.688, just below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, while the other factors ranged from 0.702 to 0.845, demonstrating acceptable to good consistency.

Item-total correlations ranged from 0.393 to 0.584, all positive, further supporting the scale’s internal reliability.

For test-retest reliability, 67 participants completed both the initial and follow-up surveys. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the two administrations was 0.791 (p < 0.001), indicating good temporal stability.

4. Discussion

The Japan HPV Knowledge Scale (J-HPV-KS) was developed by adapting the original HPV Knowledge Scale to incorporate elements specific to the Japanese context. The resulting scale consists of 17 items, including 11 from the original and six newly developed items unique to Japan. Notably, one factor consists entirely of newly added items, marking a substantial structural deviation from the original scale. As a result, we decided it would be difficult to maintain consistency with the original and positioned this as a newly developed, distinct scale. With the original developer’s consent, we named it the Japan HPV Knowledge Scale (J-HPV-KS) was developed.

The scale features a five-factor structure, with the following factors: “Risk of HPV-related diseases and their prevention,” “Transmission pathways of HPV and its prevention,” “Safety and effectiveness of the HPV vaccine,” “Efficacy of the HPV vaccine against cervical cancer and sexually transmitted diseases,” and “Susceptibility and natural progression of HPV infection.” In comparison, the Turkish version of the original scale extracted four factors, adapted to Turkey’s cultural context and HPV vaccine policies. We agree with those authors that conducting validity and reliability analyses across different cultural settings promotes broader use of the scale as a standard measurement tool and facilitates cross-cultural comparisons [

32]. We believe that such efforts will further advance research toward HPV eradication within each country.

The J-HPV-KS provides a more subdivided view of HPV and vaccine knowledge. For HPV, it covers associated diseases, transmission modes, and natural history. For vaccines, it addresses safety, efficacy, and the scope of protection. While its Cronbach’s alpha (0.868) did not reach the Turkish version’s 0.96, it is comparable to the original scale’s 0.838, indicating sufficient internal consistency.

Based on these findings, the scale is valid and reliable for use in contemporary Japanese society. This study did not restrict the gender of children, anticipating potential expansion of HPV vaccination programs to include boys in Japan. Although male vaccination is considered less cost-effective [

36], and studies have shown lower antibody titers in young men compared to women [

37,

38,

39], expanding vaccination to boys could maximize public health benefits and help gender stereotypes and misconceptions disproportionately affecting women [

40]. Equitable sharing of HPV prevention benefits is essential, and we hope this scale contributes to advancing research toward that goal.

This study is not without limitations. It included parents of junior high school students from a single prefecture in Japan. Since participation was voluntary, it is possible that those with a greater interest in the HPV vaccine were more likely to respond, which may have influenced their responses. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for Factor 4 of the HPV knowledge scale was relatively low (0.688), warranting cautious interpretation of this subscale.

5. Conclusions

The J-HPV-KS, consisting of 17 items, was developed by modifying the original HPV Knowledge Scale. It includes 11 items from the original and 6 newly developed ones tailored to the Japanese context. The scale was confirmed to be valid and reliable for use in the country. It is recommended as a screening tool to assess HPV-related knowledge and may also support research and inform more effective interventions aimed at increasing HPV vaccine uptake.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and K.K.; methodology, A.T., A.S. and K.K.; software, A.T., validation, A.T. and A.S.; formal analysis, A.T.; investigation, A.T. and K.K.; resources, K.K.; data curation, A.T. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T. and P.W.; writing—review and editing, A.T., A.S., P.W., and K.K.; visualization, A.T. and P.W.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kagawa University Faculty of Medicine (Approval Number: 2024-009).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. An information sheet describing the study was presented on the webpage hosting the web-based questionnaire. Participants were asked to read the information before beginning the survey and were informed that participation was voluntary. Consent was obtained when participants clicked the statement, “I understand the study contents and agree to participate in this study,” before proceeding to the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The article’s data will be shared upon reasonable request with the corresponding author. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Jo Walker for her invaluable support and guidance throughout this manuscript. We would also like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HPV |

Human Papillomavirus |

| J-HPV-KS |

Japan HPV Knowledge Scale |

| EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| KMO |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| GFI |

Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| AGFI |

Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| CFI |

Comparative Fit Index |

| RMSEA |

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| QR |

Quick Response |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available online (in Japanese), 2024a. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou28/index.html (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available online (in Japanese), 2021. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10601000/000854617.pdf (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available online (in Japanese), 2022. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou_kouhou/kouhou_shuppan/magazine/202205_00001.html (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Japan medical Association. Available online (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.med.or.jp/people/health/kansen/011756.html (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available online (in Japanese), 2023a. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10601000/001126459.pdf (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Gargano, J.W.; Wilkinson, E.J.; Unger, E.R.; Steinau, M.; Watson, M.; Huang, Y.; Copeland, G.; Cozen, W.; Goodman, M.T.; Hopenhayn, C.; et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus types in invasive vulvar cancers and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 3 in the United States before vaccine introduction. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2012, 16, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinau, M.; Unger, E.R.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Goodman, M.T.; Copeland, G.; Hopenhayn, C.; Cozen, W.; Saber, M.S.; Huang, Y.; Peters, E.S.; et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence in invasive anal cancers in the United States before vaccine introduction. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013, 17, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, E.D., Jr.; Giuliano, A.R.; Palefsky, J.; Flores, C.A.; Goldstone, S.; Ferris, D.; Hillman, R.J.; Moi, H.; Stoler, M.H.; Marshall, B.; et al. Incidence, clearance, and disease progression of genital human papillomavirus infection in heterosexual men. J Infect Dis 2014, 210, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado, C.; Ângela, R.F.; Acácio, G.R.; Carmen, L. Impact of human papillomavirus vaccination on male disease: A systematic review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Targeted sex of HPV vaccine national immunization programme. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNDIxZTFkZGUtMDQ1Ny00MDZk (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Bureau of Public Health; Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Available online (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.hokeniryo.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/kansen/info/hpv/hpvdansei (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Kirchhoff, A.C.; Mann, K.; Warner, E.L.; Kaddas, H.K.; Fair, D.; Fluchel, M.; Knackstedt, E.D.; Kepka, D. HPV vaccination knowledge, intentions, and practices among caregivers of childhood cancer survivors. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019, 15, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosky, E.; Bocchini, J.A.; Hariri, S.; Chesson, H.; Curtis, C.R.; Saraiya, M.; Unger, E.R.; Markowitz, L.E.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2015, 64, 300–304. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6411a3.htm (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Japanese law translation. Immunization act. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/ja/laws/view/2964/en (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Fukutori, K.; Oda, A.; Yamamoto, C.; Nukata, A.; Hirata, C.; Ito, M. Joshichugakusei no HPV kansenyobouwakuchin sesshukeiken to sonoyouin ni kansurukenkyu (in Japanese). J Health Welf Stat 2014, 61, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Furuta, K.; Yamada, K.; Morioka, I. Relationship between explanation from guardians and preventive behaviors against uterine cervical cancer at the time of inoculation of HPV vaccine: A case involving junior high school girls. J Jpn Soc Hyg 2016, 71, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.A.; Logie, C.H.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Baiden, P.; Tepjan, S.; Rubincam, C.; Doukas, N.; Asey, F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, S.J.; Yoshioka, E.; Ito, Y.; Konno, R.; Hayashi, Y.; Kishi, R.; Sakuragi, N. Acceptance of and attitudes towards human papillomavirus vaccination in Japanese mothers of adolescent girls. Vaccine 2012, 30, 5740–5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egawa-Takata, T.; Nakae, R.; Shindo, M.; Miyoshi, A.; Takiuchi, T.; Miyatake, T.; Kimura, T. Fathers. Fathers’ participation in the HPV vaccination decision-making process doesn’t increase parents’ intention to make daughters get the vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 1653–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spleen, A.M.; Kluhsman, B.C.; Clark, A.D.; Dignan, M.B.; Lengerich, E.J.; ACTION Health Cancer Task Force. An increase in HPV-related knowledge and vaccination intent among parental and non-parental caregivers of adolescent girls, age 9–17 years, in Appalachian Pennsylvania. J Cancer Educ 2012, 27, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarczyk, K.; Duszewska, A.; Drozd, S.; Majewski, S. Parents’ knowledge and attitude towards HPV and HPV vaccination in Poland. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.L.; Caldera, M.; Maurer, J. A short report: parents HPV vaccine knowledge in rural South Florida. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019, 15, 1666–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwanali, A.N.; Liundi, P.; Lubanga, A.F.; Mpinganjira, S.L.; Gadama, L.A. Caregiver acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccine for their female children in Chileka, Blantyre, Malawi. Vaccin X 2024, 20, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J.; Taylor, L.; Kooker, P.; Frank, I. Parent and adolescent knowledge of HPV and subsequent vaccination. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1049–e1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbajo, A.; Hansen, C.E.; North, A.L.; Okoloko, E.; Niccolai, L.M. ‘I think they’re all basically the same’: parents’ perceptions of human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine compared with other adolescent vaccines. Child Care Health Dev 2016, 42, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham-Erves, J.; Talbott, L.L.; O’Neal, M.R.; Ivankova, N.V.; Wallston, K.A. Development of a theory-based, sociocultural instrument to assess Black maternal intentions to vaccinate their daughters aged 9 to 12 against HPV. J Cancer Educ 2016, 31, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, S.; Tatar, O.; Ostini, R.; Shapiro, G.K.; Waller, J.; Zimet, G.; Rosberger, Z. Extending and validating a human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge measure in a national sample of Canadian parents of boys. Prev Med 2016, 91, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.L.; Strickland, O.L.; DiClemente, R.; Higgins, M.; Williams, B.; Hickey, K. Parental Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Survey (PHPVS): nurse-led instrument development and psychometric testing for use in research and primary care screening. J Nurs Meas 2013, 21, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, J.; Ostini, R.; Marlow, L.A.; McCaffery, K.; Zimet, G. Validation of a measure of knowledge about human papillomavirus (HPV) using item response theory and classical test theory. Prev Med 2013, 56, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.E.; Yelverton, V.; Wang, Y.; Ostermann, J.; Fish, L.J.; Williams, C.L.; Vasudevan, L.; Walter, E.B. Examining associations between knowledge and vaccine uptake using the human papillomavirus knowledge questionnaire (HPV-KQ). Am J Health Behav 2021, 45, 810–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Available online (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.jsog.or.jp/news_m/2163/ (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Demir Bozkurt, F.; Özdemir, S. Validity and reliability of a Turkish version of the human papillomavirus knowledge scale: a methodological study. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2023, 24, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimson Interactive Japan, Inc. Available online (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.crimsonjapan.co.jp/en/ (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Google. Google. Forms. Available online (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.google.com/forms/about/ (accessed on 22 Jul 2025).

- Nakamura, T. Shinrisyakudosakusei niokeru inshibunkeki no riyouhou (in Japanese). Annu Rep Educ Psychol Jpn 2007, 46, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihu-Amparan, L.; Pedroza-Saavedra, A.; Gutierrez-Xicotencatl, L. The immune response generated against HPV infection in men and its implications in the diagnosis of cancer. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, I.; Plata, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Correa, A.; Nossa, C.; Giuliano, A.R.; Joura, E.A.; Ferenczy, A.; Ronnett, B.M.; Stoler, M.H.; et al. Effectiveness, immunogenicity, and safety of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in women and men aged 27–45 years. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022, 18, 2078626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, S.E.; Villa, L.L.; Costa, R.L.; Petta, C.A.; Andrade, R.P.; Malm, C.; Iversen, O.E.; Høye, J.; Steinwall, M.; Riis-Johannessen, G.; et al. Induction of immune memory following administration of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine. Vaccine 2007, 25, 4931–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, A.R.; Isaacs-Soriano, K.; Torres, B.N.; Abrahamsen, M.; Ingles, D.J.; Sirak, B.A.; Quiterio, M.; Lazcano-Ponce, E. Immunogenicity and safety of Gardasil among mid-adult aged men (27–45 years)—the MAM Study. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5640–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, D.; Govender, K.; Mantell, J.E. Breaking barriers: why including boys and men is key to HPV prevention. BMC Med 2024, 22, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Original item

Original item  Added item.

Added item.