Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

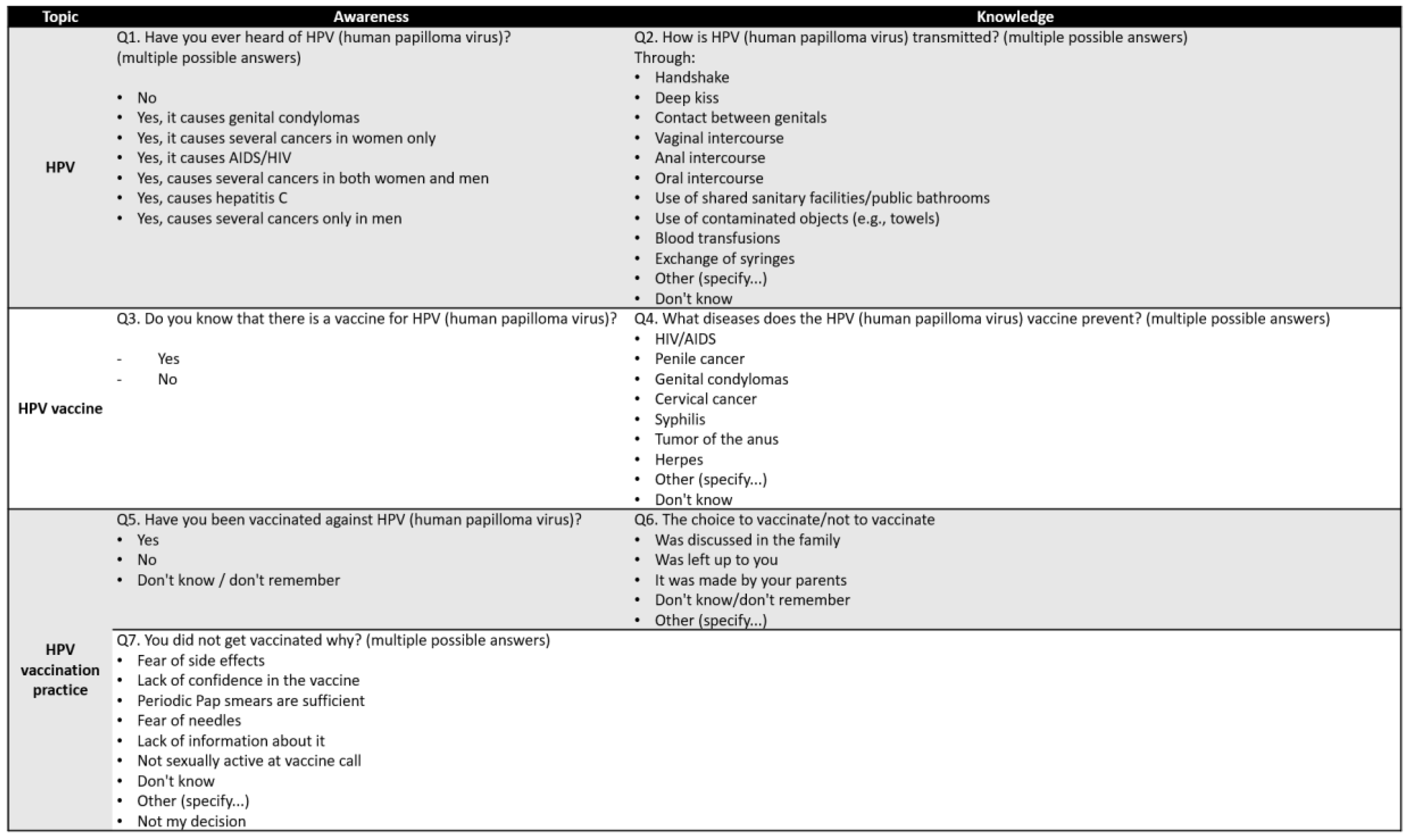

Background/Objectives: HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infectious agent worldwide and adolescents are at high risk of becoming infected with HPV. Our study aimed at understanding how much adolescents know about the virus and its effects, and to obtain infor-mation on attitudes and behaviors regarding HPV vaccination to close these gaps. Methods: Within the ESPRIT project, 598 lower and upper secondary school students from 3 Italian regions were surveyed between December 2023 and March 2024 using an online questionnaire with 7 questions on awareness, knowledge and attitudes towards HPV and the HPV vaccine. A regres-sion model was used to determine correlations based on sex, living context, province of residence and school type. Results: Younger students believed that HPV causes HIV/AIDS (8.9%) or hepati-tis C (3.0%) and rarely mentioned anal (21%) and oral sex (9.6%) as ways of transmission. Among older students the misconceptions were similar, with worrying rates of students stating that HPV causes cancer only in women (18%) or men (2.4%), and low rates of identifying trans-mission risk from anal (41%) and oral (34%) intercourse and genital contact (38%). HPV vac-cination rate was quite low (47% in younger, 61% in older students). Considering regressions, the living context was decisive for the knowledge of younger students; sex, school type and province of residence in older students. Conclusions: Awareness and knowledge of HPV and the HPV vaccine are low among Italian students, and reported vaccination coverage is below the national target. Coordinated efforts at national level are needed to address this public health issue.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Research Instrument

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample of Participants subsection

3.2. Lower Secondary School Adolescents

3.3. Upper Secondary School Adolescents

3.4. Determinants of Higher Knowledge about HPV and the HPV Vaccine

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

ESPRIT study collaboration group

ESPRIT study network group

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human papillomaviruses. Vol. 90. IARC; 2007. 670 p.

- Global Cancer Observatory I. IARC. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Cancers attributable to infections. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/causes/infections/tools-bars?mode=2&sex=0&population=who&country=4&continent=0&agent=0&cancer=0&key=attr_cases&lock_scale=0&nb_results=10.

- Formana D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomatarama I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012;30(SUPPL.5).

- World Health Organization. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. World Health Organization; 2020. 52 p.

- Harris B, McCredie MN, Truong T, Regan T, Thompson CG, Leach W, et al. Relations Between Adolescent Sensation Seeking and Risky Sexual Behaviors Across Sex, Race, and Age: A Meta-Analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2023 Jan 1;52(1):191–204. [CrossRef]

- Icardi G, Costantino C, Guido M, Zizza A, Restivo V, Amicizia D, et al. Burden and Prevention of HPV. Knowledge, Practices and Attitude Assessment Among Pre-Adolescents and their Parents in Italy. Curr Pharm Des. 2020 Jan 14;26(3):326–42. [CrossRef]

- Brunelli L, Bravo G, Romanese F, Righini M, Lesa L, De Odorico A, et al. Beliefs about HPV vaccination and awareness of vaccination status: Gender differences among Northern Italy adolescents. Prev Med Rep [Internet]. 2021;24:101570. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Zizza A, Guido M, Recchia V, Grima P, Banchelli F, Tinelli A. Knowledge, information needs and risk perception about hiv and sexually transmitted diseases after an education intervention on italian high school and university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb 2;18(4):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Juneau C, Fall E, Bros J, Le Duc-Banaszuk AS, Michel M, Bruel S, et al. Do boys have the same intentions to get the HPV vaccine as girls? Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions in France. Vaccine. 2024 Apr 11;42(10):2628–36. [CrossRef]

- Brunelli L, Bravo G, Romanese F, Righini M, Lesa L, De Odorico A, et al. Sexual and reproductive health-related knowledge, attitudes and support network of Italian adolescents. Public Health in Practice [Internet]. 2022;3(April):100253. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro F, Segala FV, Guido G, Poliseno M, De Santis L, Belati A, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices about HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among High School students in Southern Italy: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2024 Apr 1;19(4). [CrossRef]

- Tilson EC, Sanchez V, Ford CL, Smurzynski M, Leone PA, Fox KK, et al. Barriers to asymptomatic screening and other STD services for adolescents and young adults: focus group discussions [Internet]. 2004. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/4/21.

- Jin SW, Lee Y, Brandt HM. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Knowledge, Beliefs, and Hesitancy Associated with Stages of Parental Readiness for Adolescent HPV Vaccination: Implications for HPV Vaccination Promotion. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023 May 1;8(5). [CrossRef]

- Jiboc NM, Paşca A, Tăut D, Băban AS. Factors influencing human papillomavirus vaccination uptake in European women and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 33, Psycho-Oncology. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Harrell ;, Chesson W, Unger ER, Romero JR, et al. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [Internet]. 2019 Aug. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/.

- Gazzetta S, Valent F, Sala A, Driul L, Brunelli L. Sexually transmitted infections and the HPV-related burden: evolution of Italian epidemiology and policy. Front Public Health. 2024;12. [CrossRef]

- Mennini FS, Silenzi A, Marcellusi A, Conversano M, Siddu A, Rezza G. HPV Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy: Opportunity Loss or Incremental Cost. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Jul 1;10(7). [CrossRef]

- Brunelli L, Valent F, Comar M, Suligoi B, Salfa MC, Gianfrilli D, et al. Study protocol for a pre/post study on knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding STIs and in particular HPV among Italian adolescents, teachers, and parents in secondary schools. Front Public Health. 2024;12(1414631). [CrossRef]

- Fallucca A, Immordino P, Riggio L, Casuccio A, Vitale F, Restivo V. Acceptability of HPV Vaccination in Young Students by Exploring Health Belief Model and Health Literacy. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Jul 1;10(7). [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Salute. Piano Nazionale della Prevenzione Vaccinale 2023-2025. 2023.

- Thanasas I, Lavranos G, Gkogkou P, Paraskevis D. The Effect of Health Education on Adolescents’ Awareness of HPV Infections and Attitudes towards HPV Vaccination in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 1;19(1). [CrossRef]

- Costantino C, Amodio E, Vitale F, Trucchi C, Maida CM, Bono SE, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and vaccination: Pre-post intervention analysis on knowledge, attitudes and willingness to vaccinate among preadolescents attending secondary schools of palermo, sicily. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Aug 1;17(15):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Huang Y, Lv Q, Wang L, Wu S, Wu Q. Knowledge, awareness, and correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability among male junior high school students in Zhejiang Province, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024;20(1). [CrossRef]

- Martinelli M, Veltri GA. Shared understandings of vaccine hesitancy: How perceived risk and trust in vaccination frame individuals’ vaccine acceptance. PLoS One. 2022 Oct 1;17(10 October). [CrossRef]

- Chyderiotis S, Derhy S, Gaillot J, Cobigo A, Zanetti L, Piel C, et al. Providing parents with HPV vaccine information from a male perspective may render them more inclined to have their daughters vaccinated. Infect Dis Now. 2024 Jun 1;54(4). [CrossRef]

- Lefevre H, Samain S, Ibrahim N, Fourmaux C, Tonelli A, Rouget S, et al. HPV vaccination and sexual health in France: Empowering girls to decide. Vaccine. 2019 Mar 22;37(13):1792–8. [CrossRef]

- Dionne M, Étienne D, Witteman HO, Sauvageau C, Dubé È. Impact of interventions to improve HPV vaccination acceptance and uptake in school-based programs: Findings of a pilot project in Quebec. Vaccine. 2024 Jul 11;42(18):3768–73. [CrossRef]

- Choi J, Gabay EK, Cuccaro PM. School Teachers’ Perceptions of Adolescent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination: A Systematic Review. Vol. 12, Vaccines. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024. [CrossRef]

- Felsher M, Shumet M, Velicu C, Chen YT, Nowicka K, Marzec M, et al. A systematic literature review of human papillomavirus vaccination strategies in delivery systems within national and regional immunization programs. Vol. 20, Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2024. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. International technical guidance on sexuality education. An evidence-informed approach [Internet]. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); 2018. Available from: www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbyncnd-en.

- Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MIUR). MIUR. 2022 [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Circolare n. 1211 del 4 maggio 2022. Available from: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/6740601/nota+17+maggio-+prot.+n.1211.05-05-2022.pdf/1cf7c827-f5d7-91b0-9f57-0557e338b555?version=1.0&t=1651756892286.

- Ministero della Salute. Piano Nazionale della Prevenzione 2020-2025 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2955_allegato.pdf.

- Cantile T, Leuci S, Blasi A, Coppola N, Sorrentino R, Ferrazzano GF, et al. Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination and Oropharyngeal Cancer: Knowledge, Perception and Attitude among Italian Pediatric Dentists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 1;19(2). [CrossRef]

- Verhees F, Demers I, Schouten LJ, Lechner M, Speel EJM, Kremer B. Public awareness of the association between human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. Eur J Public Health. 2021 Oct 1;31(5):1021–5. [CrossRef]

| Answers | Overall (N=135) | Sex (n (%)) | Living context (n (%)) | Province of residence (n (%)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (N=59) |

Girls (N=74) | Other (N=2) | Urban (N=71) | Extra-urban (N=64) | Udine (N=51) | Palermo (N=84) | ||

| Awareness about HPV – Q1: Have you ever heard of HPV (human papilloma virus)? | ||||||||

| No | 68 (50%) | 30 (51%) | 37 (50%) | 1(50%) | 36 (51%) | 32 (50%) | 24 (47%) | 44 (52%) |

| Yes, it causes several cancers in both women and men | 33 (24%) | 11 (19%) | 22 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 20 (28%) | 13 (20%) | 18 (35%)§ | 15 (18%)§ |

| Yes, it causes genital condylomas | 18 (13%) | 11 (19%) | 7 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (17%) | 6 (9.4%) | 3 (5.9%) | 15 (18%) |

| Yes, it causes AIDS/HIV | 12 (8.9%) | 6 (10%) | 6 (8.1%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (8.5%) | 6 (9.4%) | 5 (9.8%) | 7 (8.3%) |

| Yes, it causes several cancers in women only | 10 (7.4%) | 6 (10%) | 4 (5.4%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (5.6%) | 6 (9.4%) | 2 (3.9%) | 8 (9.5%) |

| Yes, it causes hepatitis C | 4 (3.0%) | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.8%) | 2 (3.1%) | 2 (3.9%) | 2 (2.4%) |

| Yes, it causes several cancers only in men | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| missing | 5 (3.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 3 (4.1%) | 1(50%) | 1 (1.4%) | 4 (6.3%) | 2 (3.9%) | 3 (3.6%) |

| Knowledge about HPV – Q2: How is HPV (human papilloma virus) transmitted? | ||||||||

| Contact between genitals* | 57 (42%) | 23 (39%) | 34 (46%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (44%) | 26 (41%) | 18 (35%) | 39 (46%) |

| Vaginal intercourse* | 56 (41%) | 22 (37%) | 34 (46%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (44%) | 25 (39%) | 21 (41%) | 35 (42%) |

| Anal intercourse* | 29 (21%) | 15 (25%) | 14 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (27%) | 10 (16%) | 13 (25%) | 16 (19%) |

| Deep kiss* | 17 (13%) | 4 (6.8%) | 13 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (15%) | 6 (9.4%) | 5 (9.8%) | 12 (14%) |

| Use of shared sanitary facilities /public bathrooms | 14 (10%) | 5 (8.5%) | 9 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (9.9%) | 7 (11%) | 2 (3.9%) | 12 (14%) |

| Use of contaminated objects (e.g., towels)* | 13 (9.6%) | 5 (8.5%) | 8 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (8.5%) | 7 (11%) | 3 (5.9%) | 10 (12%) |

| Oral intercourse* | 13 (9.6%) | 5 (8.5%) | 8 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (11%) | 5 (7.8%) | 3 (5.9%) | 10 (12%) |

| Exchange of syringes* | 13 (9.6%) | 4 (6.8%) | 9 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (11%) | 5 (7.8%) | 5 (9.8%) | 8 (9.5%) |

| Blood transfusions* | 13 (9.6%) | 5 (8.5%) | 8 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (13%) | 4 (6.3%) | 5 (9.8%) | 8 (9.5%) |

| Handshake | 3 (2.2%) | 1 (1.7%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (2.4%) |

| Don't know | 44 (33%) | 23 (39%) | 20 (27%) | 1(50%) | 29 (41%)§ | 15 (23%)§ | 22 (43%) | 22 (26%) |

| missing | 7 (5.2%) | 3 (5.1%) | 3 (4.1%) | 1(50%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (11%) | 4 (7.8%) | 3 (3.6%) |

| Awareness about HPV vaccine – Q3: Do you know that there is a vaccine for HPV (Human Papilloma Virus)? | ||||||||

| Yes | 109 (81%) | 45 (76%) | 64 (86%) | 0 (0%) | 61 (86%) | 48 (75%) | 44 (86%) | 65 (77%) |

| No | 22 (16%) | 12 (20%) | 9 (12%) | 1(50%) | 9 (13%) | 13 (20%) | 6 (12%) | 16 (19%) |

| missing | 4 (3.0%) | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1(50%) | 1 (1.4%) | 3 (4.7%) | 1 (2.0%) | 3 (3.6%) |

| Knowledge about HPV vaccine – Q4: What diseases does the HPV (Human Papilloma Virus) vaccine prevent? | ||||||||

| Genital condylomas* | 17 (13%) |

8 (14%) |

9 (12%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (15%) |

6 (9.4%) |

4 (7.8%) | 13 (15%) |

| HIV/AIDS | 28 (21%) | 14 (24%) | 14 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (15%) | 17 (27%) | 6 (12%) | 22 (26%) |

| Penile cancer* | 28 (21%) | 8 (14%) | 20 (27%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (27%) | 9 (14%) | 8 (16%) | 20 (24%) |

| Tumor of the anus* | 22 (16%) | 5 (8.5%) | 16 (22%) |

1 50%) |

15 (21%) |

7 (11%) |

6 (12%) | 16 (19%) |

| Herpes | 19 (14%) |

5 (8.5%) |

14 (19%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (15%) | 8 (13%) |

2 (3.9%) | 17 (20%) |

| Cervical cancer* | 17 (13%) | 3 (5.1%) | 14 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (9.9%) | 10 (16%) | 4 (7.8%) | 13 (15%) |

| Syphilis | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Don't know | 36 (27%) | 14 (24%) | 22 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (30%) | 15 (23%) | 36 (71%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 28 (21%) | 16 (27%) | 12 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (31%)§ | 6 (9.4%)§ | 0 (0%) | 28 (33%) |

| missing | 4 (3.0%) | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1(50%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (6.3%) |

1 (2.0%) | 3 (3.6%) |

| *Correct option; in bold: statistically different values when <0.05§ or <0.001^. | ||||||||

| Answers | Overall (N=463) | Sex (n (%)) | Living context (n (%)) | Province of residence (n (%)) | Type of upper secondary school (n (%)) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (N=185) |

Girls (N=270) | Other (N=8) | Urban (N=279) | Extra-urban (N=184) | Udine (N=226) | Rome (N=116) | Palermo (N=121) | Academic (N=206) | Vocational (N=114) | Technical (N=143) | ||

| Awareness about HPV – Q1: Have you ever heard of HPV (human papilloma virus)? | ||||||||||||

| No | 158 (34%) | 74 (40%)§ |

78 (29%)§ |

6 (75%)§ |

88 (32%) | 70 (38%) |

70 (31%) |

45 (39%) |

43 (36%) |

56 (27%)§ |

42 (37%)§ |

60 (42%)§ |

| Yes, it causes several cancers in both women and men | 130 (28%) |

44 (24%) |

85 (31%) |

1 (13%) |

89 (32%)§ |

41 (22%)§ |

65 (29%) |

33 (28%) |

32 (26%) |

69 (33%) |

25 (22%) |

36 (25%) |

| Yes, it causes AIDS/HIV | 89 (19%) | 39 (21%) | 50 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 47 (17%) |

42 (23%) | 41 (18%) | 23 (20%) | 25 (21%) | 37 (18%) | 26 (23%) | 26 (18%) |

| Yes, it causes several cancers in women only | 83 (18%) |

19 (10%)^ |

64 (24%)^ |

0 (0%)^ |

49 (18%) | 34 (18%) |

40 (18%)§ |

13 (11%)§ |

30 (25%)§ | 40 (19%) |

20 (18%) |

23 (16%) |

| Yes, it causes genital condylomas | 52 (11%) |

17 (9.2%) |

34 (13%) |

1 (13%) |

36 (13%) |

16 (8.7%) |

24 (11%)§ |

20 (17%)§ |

8 (6.6%)§ |

19 (9.2%) |

17 (15%) |

16 (11%) |

| Yes, it causes hepatitis C | 21 (4.5%) | 12 (6.5%) | 9 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (3.2%) |

12 (6.5%) |

17 (7.5%) | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (1.7%) |

6 (2.9%) |

4 (3.5%) |

11 (7.7%) |

| Yes, it causes several cancers only in men | 11 (2.4%) | 8 (4.3%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (3.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | 7 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.3%) | 8 (3.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Knowledge about HPV – Q2: How is HPV (human papilloma virus) transmitted? | ||||||||||||

| Vaginal intercourse* | 299 (65%) | 115 (62%) | 180 (67%) | 4 (50%) | 179 (64%) | 120 (65%) | 145 (64%) | 69 (59%) | 85 (70%) | 145 (70%)§ | 72 (63%)§ | 82 (57%)§ |

| Anal intercourse* | 190 (41%) | 75 (41%) | 111 (41%) | 4 (50%) | 116 (42%) | 74 (40%) | 98 (43%) | 42 (36%) | 50 (41%) | 95 (46%) | 45 (39%) | 50 (35%) |

| Contact between genitals* | 178 (38%) | 52 (28%)^ | 124 (46%)^ | 2 (25%)^ | 107 (38%) | 71 (39%) | 87 (38%) | 45 (39%) | 46 (38%) | 81 (39%) | 45 (39%) | 52 (36%) |

| Oral intercourse* | 158 (34%) | 61 (33%) |

94 (35%) |

3 (38%) |

97 (35%) |

61 (33%) |

81 (36%) |

37 (32%) |

40 (33%) |

72 (35%) |

40 (35%) |

46 (32%) |

| Exchange of syringes* | 114 (25%) | 47 (25%) | 66 (24%) | 1 (13%) | 82 (29%)§ | 32 (17%)§ | 66 (29%)§ | 19 (16%)§ | 29 (24%)§ | 64 (31%)§ | 20 (18%)§ | 30 (21%)§ |

| Blood transfusions* | 107 (23%) | 47 (25%) |

58 (21%) |

2 (25%) |

77 (28%)§ |

30 (16%)§ |

66 (29%)§ |

17 (15%)§ |

24 (20%)§ |

59 (29%)§ |

21 (18%)§ |

27 (19%)§ |

| Use of contaminated objects (e.g., towels)* | 48 (10%) | 23 (12%) | 24 (8.9%) | 1 (13%) | 34 (12%) |

14 (7.6%) |

26 (12%) | 8 (6.9%) |

14 (12%) |

27 (13%) |

7 (6.1%) |

14 (9.8%) |

| Deep kiss* | 46 (9.9%) | 21 (11%) |

23 (8.5%) | 2 (25%) |

29 (10%) | 17 (9.2%) | 26 (12%) |

10 (8.6%) |

10 (8.3%) |

23 (11%) | 12 (11%) | 11 (7.7%) |

| Use of shared sanitary facilities /public bathrooms | 26 (5.6%) | 8 (4.3%) | 15 (5.6%) | 3 (38%) | 21 (7.5%)§ | 5 (2.7%)§ | 16 (7.1%) | 5 (4.3%) | 5 (4.1%) | 16 (7.8%) | 4 (3.5%) | 6 (4.2%) |

| Handshake | 2 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) |

1 (0.4%) | 1 (13%) |

1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.5%) |

2 (0.9%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (0.9%) |

1 (0.7%) |

| Other | 6 (1.3%) | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (13%) | 3 (1.1%) | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (2.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) | 4 (2.8%) |

| Don't know | 108 (23%) | 48 (26%) |

58 (21%) |

2 (25%) |

71 (25%) |

37 (20%) |

52 (23%) |

33 (28%) |

23 (19%) |

42 (20%) |

27 (24%) |

39 (27%) |

| missing | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

1 (0.5%) |

1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (0.7%) |

| Awareness about HPV vaccine – Q3: Do you know that there is a vaccine for HPV (human papilloma virus)? | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 406 (88%) | 152 (82%)^ | 248 (92%)^ | 6 (75%)^ | 246 (88%) | 160 (87%) |

195 (86%) |

100 (86%) |

111 (92%) |

189 (92%)^ |

92 (81%)^ |

125 (87%)^ |

| No | 57 (12%) | 33 (18%) | 22 (8.1%) | 2 (25%) | 33 (12%) | 24 (13%) | 31 (14%) | 16 (14%) | 10 (8.3%) | 17 (8.3%) | 22 (19%) | 18 (13%) |

| Knowledge about HPV vaccine – Q4: What diseases does the HPV (human papilloma virus) vaccine prevent? | ||||||||||||

| HIV/AIDS | 203 (44%) | 77 (42%) | 121 (45%) | 5 (63%) | 111 (40%)§ | 92 (50%)§ | 94 (42%) | 53 (46%) | 56 (46%) | 80 (39%) | 57 (50%) | 66 (46%) |

| Cervical cancer* | 171 (37%) | 41 (22%)^ | 127 (47%)^ | 3 (38%)^ | 102 (37%) | 69 (38%) | 81 (36%) | 39 (34%) | 51 (42%) | 88 (43%)§ | 41 (36%)§ | 42 (29%)§ |

| Penile cancer* | 109 (24%) | 56 (30%)§ | 52 (19%)§ | 1 (13%)§ | 65 (23%) | 44 (24%) | 46 (20%) | 30 (26%) | 33 (27%) | 51 (25%) | 29 (25%) | 29 (20%) |

| Genital condylomas* | 77 (17%) | 31 (17%) | 46 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 58 (21%)§ | 19 (10%)§ | 43 (19%) | 18 (16%) | 16 (13%) | 45 (22%)§ | 15 (13%)§ | 17 (12%)§ |

| Tumor of the anus* | 56 (12%) | 28 (15%) | 27 (10%) | 1 (13%) | 33 (12%) | 23 (13%) | 26 (12%) |

17 (15%) |

13 (11%) |

19 (9.2%) | 18 (16%) | 19 (13%) |

| Syphilis | 38 (8.2%) | 17 (9.2%) | 19 (7.0%) | 2 (25%) | 29 (10%) | 9 (4.9%) | 25 (11%) | 8 (6.9%) | 5 (4.1%) | 22 (11%) | 7 (6.1%) | 9 (6.3%) |

| Herpes | 34 (7.3%) | 12 (6.5%) | 20 (7.4%) | 2 (25%) |

21 (7.5%) | 13 (7.1%) |

20 (8.8%) |

6 (5.2%) |

8 (6.6%) |

14 (6.8%) |

11 (9.6%) | 9 (6.3%) |

| Other | 65 (14%) | 34 (18%) | 29 (11%) | 2 (25%) | 48 (17%) | 17 (9.2%) | 38 (17%) | 20 (17%) | 7 (5.8%) | 28 (14%) | 13 (11%) | 24 (17%) |

| missing | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| *Correct option; in bold: statistically different values when <0.05§ or <0.001^. | ||||||||||||

| Lower secondary school students | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Count model | Zero-inflation model | |||||||

| Estimate | Standard error | z-value | p-value | Estimate | Standard error | z-value | p-value | ||

| (Intercept) | 2.25 | 0.05 | 42.48 | <0.001 | -1.15 | 0.24 | -4.87 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Girls | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Boys | -0.11 | 0.05 | -2.42 | 0.015 | -0.11 | 0.23 | -0.47 | 0.641 | |

| Other | -0.23 | 0.30 | -0.75 | 0.450 | -12.80 | 1040.82 | -0.01 | 0.990 | |

| Living context | Extra-urban | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Urban | 0.20 | 0.05 | 4.08 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 3.43 | <0.001 | |

| Province of residence | Udine | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Palermo | 0.17 | 0.05 | 7.86 | <0.001 | -0.64 | 0.24 | -2.69 | 0.007 | |

| Upper secondary school students | |||||||||

| Model | Count model | Zero-inflation model | |||||||

| Estimate | Standard error | z-value | p-value | Estimate | Standard error | z-value | p-value | ||

| (Intercept) | 2.62 | 0.01 | 204.95 | <0.001 | -5.30 | 0.38 | -14.00 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Girls | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Boys | -0.12 | 0.01 | -12.11 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 1.91 | 0.056 | |

| Other | -0.41 | 0.14 | -3.01 | 0.003 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 0.315 | |

| Living context | Extra-urban | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Urban | -0.14 | 0.01 | -14.07 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.72 | 0.468 | |

| Province of residence | Udine | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Rome | 0.12 | 0.01 | 9.69 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 4.45 | <0.001 | |

| Palermo | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.59 | 0.56 | -0.83 | 0.30 | -2.80 | 0.005 | |

| Type of school | Academic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Technical | -0.16 | 0.01 | -13.15 | <0.001 | 2.42 | 0.34 | 7.16 | <0.001 | |

| Vocational | -0.13 | 0.01 | -11.44 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 0.37 | 3.32 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).