3.1. Cell Viability with Different Processing Types

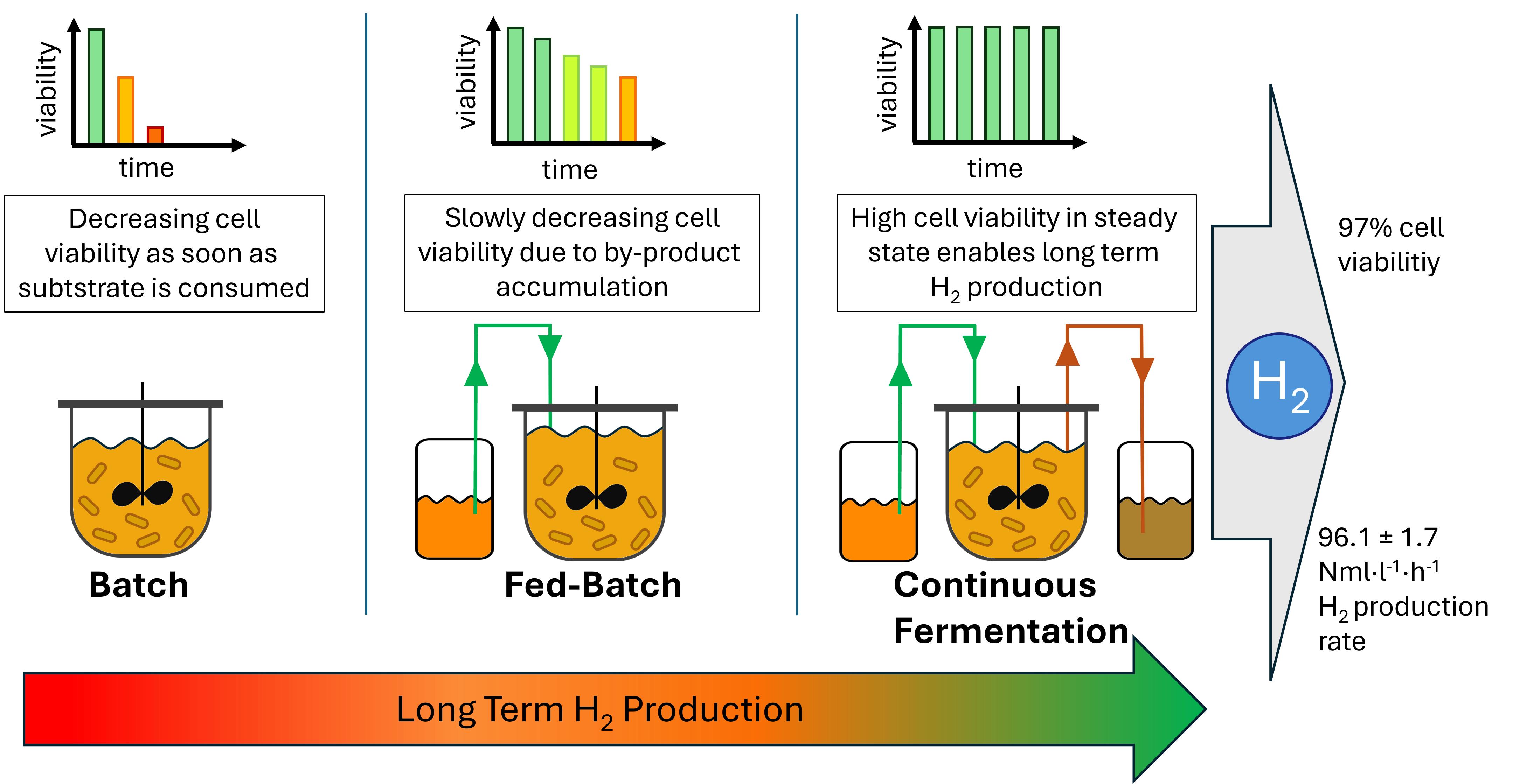

Bacterial cell viability is an important factor in establishing long term processes. The expectation for each batch cultivation is a decreasing cell viability, as the consumption of all substrates and accumulation of by-products lead to increasingly unfavourable conditions. In fed-batch processes, where substrate limitations are mitigated, cell viability also tends to decline over time due to by-product accumulation, ultimately leading to cell lysis. This effect is particularly critical in fed-batch systems with slow-growing organisms and in batch systems with cell retention, as long-term viability directly impacts process stability. Despite the accumulation of by-products, the cells begin to lyse at a certain point. After complete lysis, the cells were neither detectable for biomass determination nor for viability determination.

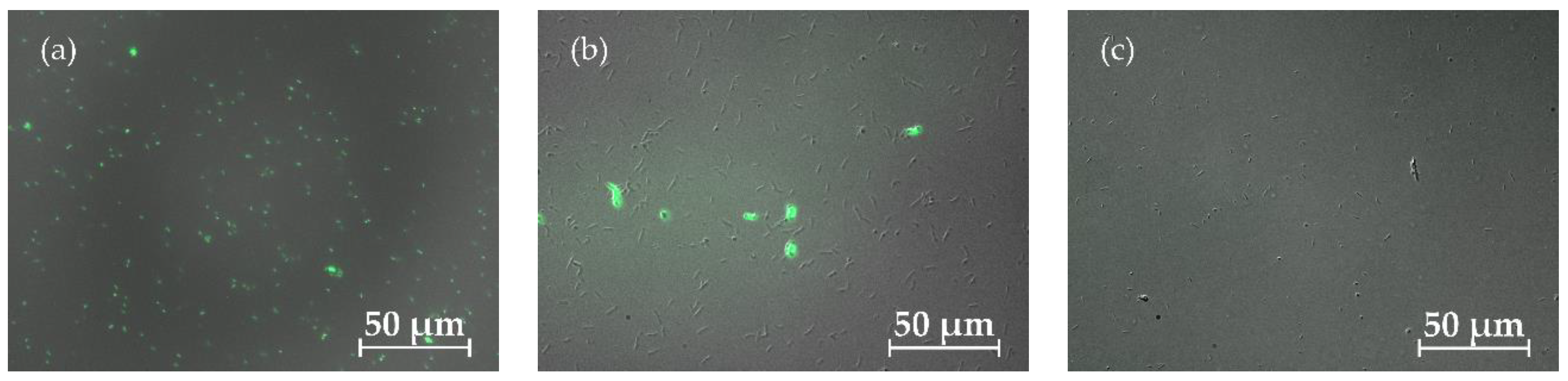

As shown in

Figure 2, dead (coloured) cells can be distinguished from living (uncoloured) cells. By counting the stained and unstained cells, the relative proportions of cells still alive could be determined. Samples were taken at different times for all fermentation approaches and compared with fresh dead or live controls.

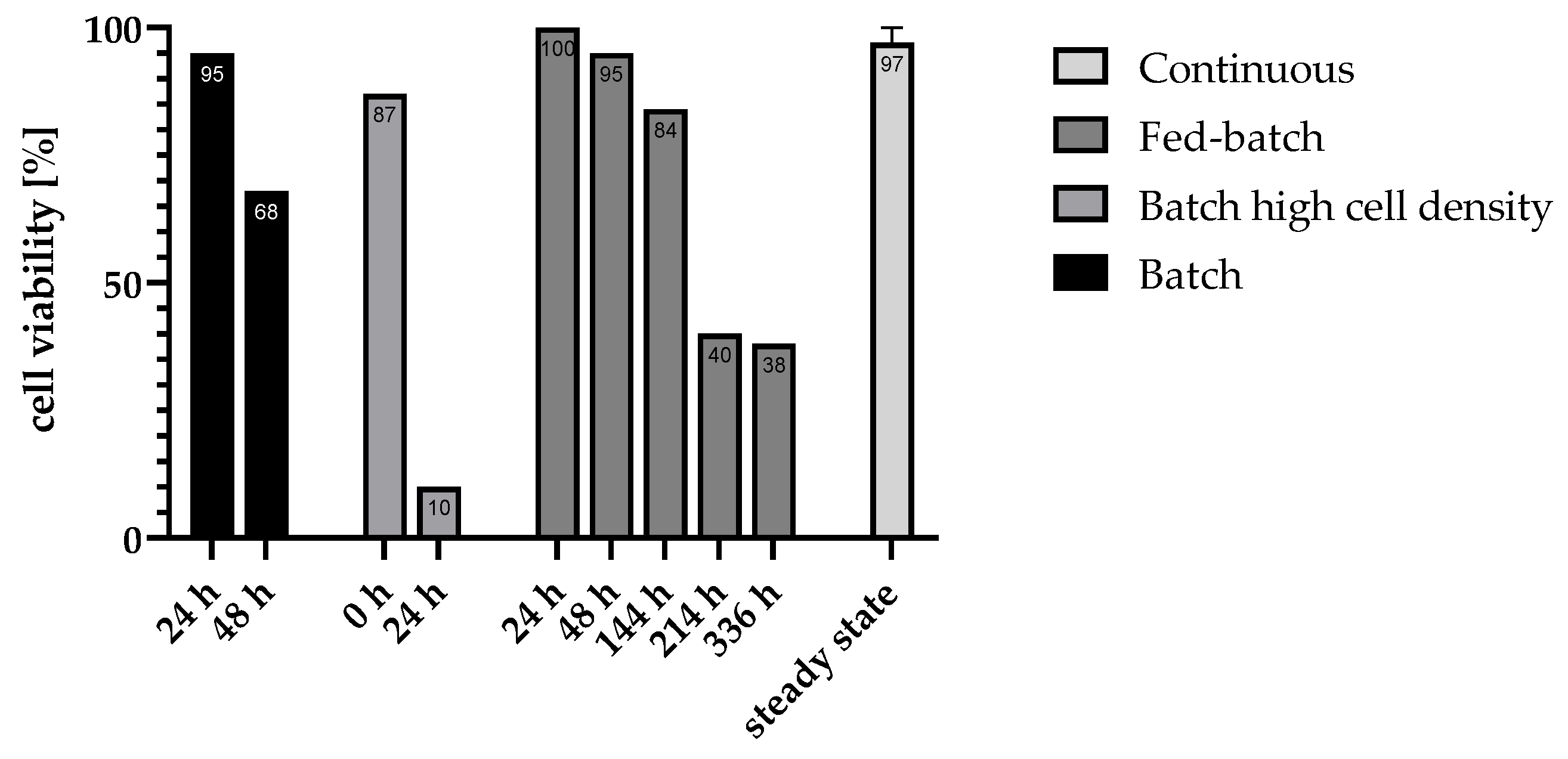

Figure 3 illustrates cell viability across different fermentation modes over time, highlighting the varying stability and resilience of each approach.

In batch processes, a rapid decline in cell viability was observed, with viability dropping from 95% at 24 h to 68% at 48 h, indicating a limited capacity to sustain cells under nutrient-depleted and by-product-accumulating conditions.

In contrast, the fed-batch approach demonstrated a more gradual decline in viability, starting from 100%, slight decreasing to 95% at 48 h and further decreasing to 84% at 144 h. Nevertheless, viability fell to 38% at later stages, suggesting improved but still limited longevity due to eventual by-product toxicity. This indicates that the availability of essential nutrients alone is not enough to maintain high cell viability over longer periods of time.

High-density batch cultures maintained high initial viability, which indicates, that the process of centrifugation for preparing the fermentation approach did not damage most cells. Nonetheless the dropped viability to 10% within the first 24 h displayed, indicates that even high cell concentrations cannot mitigate long-term viability loss in batch setups.

The consistently high viability of 97% observed in the continuous mode can be attributed to the absence of inhibitory by-product accumulation, as cells are continuously flushed out and replaced by freshly generated cells. This constant renewal maintains a stable and active cell population, supporting prolonged hydrogen production without the inhibitory effects seen in batch and fed-batch processes

3.2. Bacterial Cell Growth

At first to estimate possible dilution rates for continuous process and feeding rate for fed-batch, a normal batch cultivation and a batch cultivation with high cell density at beginning was performed. Based on these results the highest growth rate and substrate consumption could be calculated.

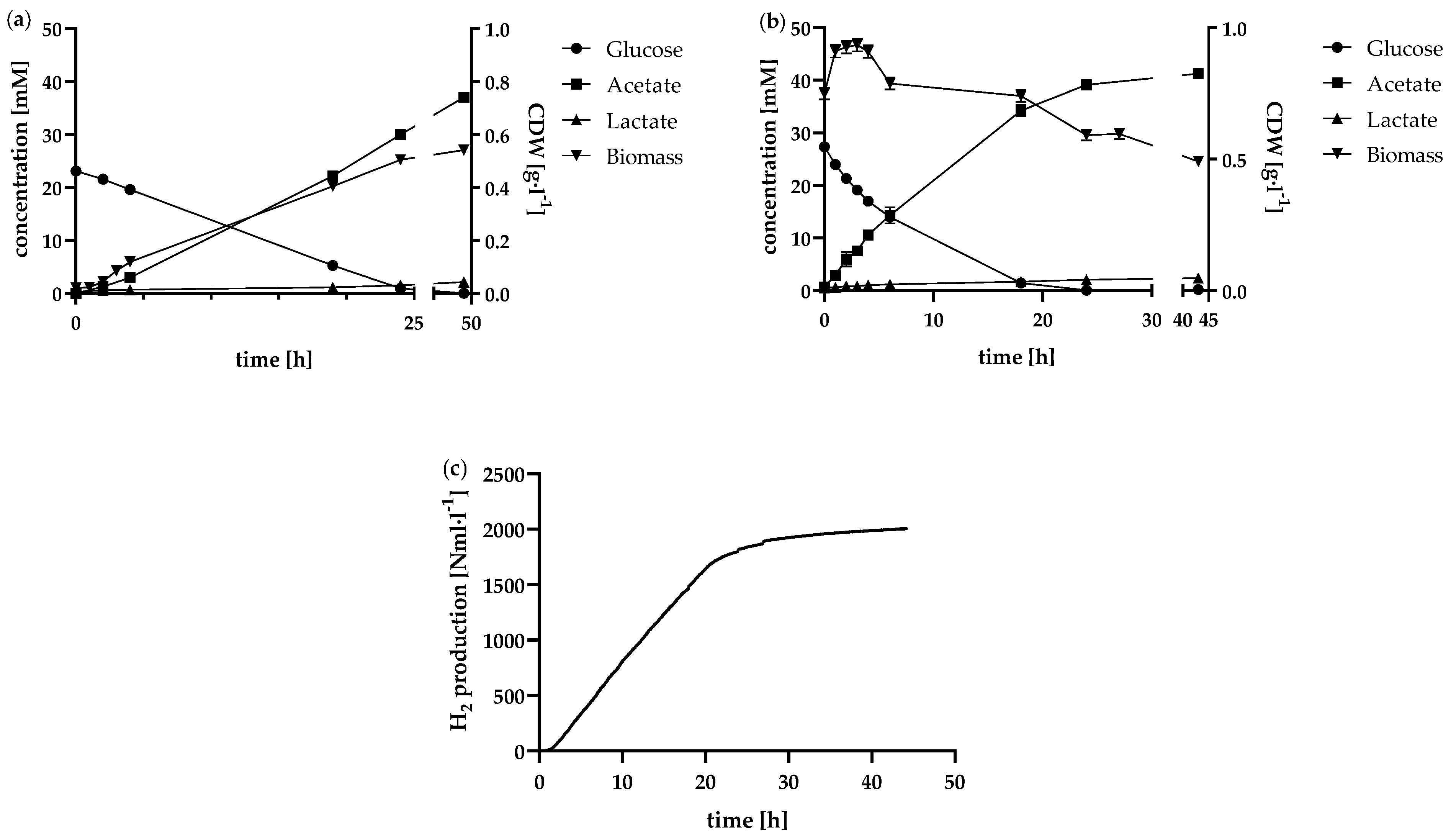

In addition to the metabolisation of glucose,

Figure 4a also shows the course of biomass formation in a normal batch mode fermentation. Based on biomass concentration measurements, the exponential growth phase between 1 h and 3 h was identified. The maximum growth rate µ

max was 0.77 ± 0.06 h

−1.

Although this growth rate is slightly lower than the value of 0.94 h

−¹ reported by Yu [

39] and Jannasch

et al., who calculated a similar growth rate from a doubling time of 0.75 h (equivalent to 0.92 h⁻¹) [

10,

39], it is notably higher than the rate reported by Frascari

et al. for suspended cells with glucose as a substrate, which was 0.024 ± 0.005 h⁻¹ [

40]. Differences in media composition and preculture treatments likely account for these variations, highlighting how specific cultivation conditions can significantly influence the maximum growth rate.

The maximum growth rate defines the upper limit for feasible dilution rates in continuous operation, as higher dilution rates would lead to cell washout, exceeding the rate of cellular growth [

41,

42]. Another approach to determining optimal dilution rates is to consider the maximum substrate consumption rate, since the feed medium for continuous operation was identical to that used in batch fermentation. In this study, the maximum glucose consumption rate was 0.97 ± 0.10 mmol·l⁻¹·h⁻¹. It is important to note, however, that cell density at the start of batch fermentation during exponential growth is significantly lower than after 24 h of fermentation. Within the first 24 h, the substrate was almost entirely depleted, similar to findings in other batch studies using a pH-controlled bioreactor with glucose as the substrate [

20,

35]. Accordingly, the biomass concentration also almost reached its maximum after 24 h at 0.50 ± 0.02 g·l

−1. Hardly any metabolic activity was observed in the following 24 h of fermentation. This is also reflected in the viability of the cells during the course of fermentation, as shown in

Figure 3. While the viability only dropped to 95% in the first 24 h of fermentation, it fell further to 68% in the further course. From this point on it can be concluded that at later stages of the fermentation with higher cell densities in a batch approach, optimal growth conditions were no longer present. This can also be attributed to the fact that substrate was no longer available in excess and by-products accumulated in the reactor as a result of metabolism, which can have inhibiting effects. In order to be able to simulate how high the substrate consumption rate can be with cultures of increased biomass concentration, this was also determined for the batch approach with increased cell concentration. In the high cell concentrated batch, a glucose consumption rate of 2.58 ± 0.16 mmol·l

−1·h

−1 was determined for the period between 0 and 4 h, during which exponential growth occurred in the normal batch. This value indicates how fast the substrate consumption rate can be under optimal conditions without inhibition by by-products. The feed rate for the fed-batch and the dilution rate for the chemostat were based on these results.

In contrast to the normal batch, no exponential growth of the bacteria was observed in the high cell density batch, as shown in

Figure 4b. The biomass concentration rose from 0.75 to 0.91 g·l

−1, stagnated and fell again after 4 h. With a cell viability of 87% at the start of fermentation, the concentrated cell inoculum demonstrated high viability, indicating that the initial cell concentration was suitable for most cells. This high biomass concentration, along with an increased substrate consumption rate, contributed to correspondingly elevated H₂ production rates. As illustrated in

Figure 4c, H

2 production between 1 h and 17 h was almost linear. Calculated at 1 h intervals, the average H

2 production rate during this period was 89.0 ± 6.5 Nml·l

−1·h

−1. A total of 2,005 ± 44 Nml·l

−1 H

2 was produced over the fermentation period of 44 h.

In order to determine what was produced in the process of fermentation in addition to the products already mentioned, further by-product formation was analysed in more detail. As already known from

T. neapolitana, alanine was detected. However, another amino acid, namely glutamate, was also detected. An increase in alanine (

Figure S1) and glutamate (

Figure S2) concentration could be observed. Both batch approaches ended up with comparable amino acid concentrations. The concentration of alanine reached with 0.84 ± 0.01 mM its maximum and highest glutamate concentration was 0.67 ± 0.08 mM. Alanine as by-product is known from

T. neapolitana in low amounts. However, little is known so far about glutamate production. Nonetheless, a glutamate dehydrogenase has been described previously for a closely related species,

T. maritima [

43]. The concentrations measured here are comparatively low compared to the main by-products produced. Others with considerably higher production rates, such as

Corynebacterium glutamicum, have already been established for the industrial production of amino acids [

44]. Here, the analysis of the amino acids produced is primarily used to determine the products into which the glucose is metabolised, as all by-products can affect the possible H

2 yield.

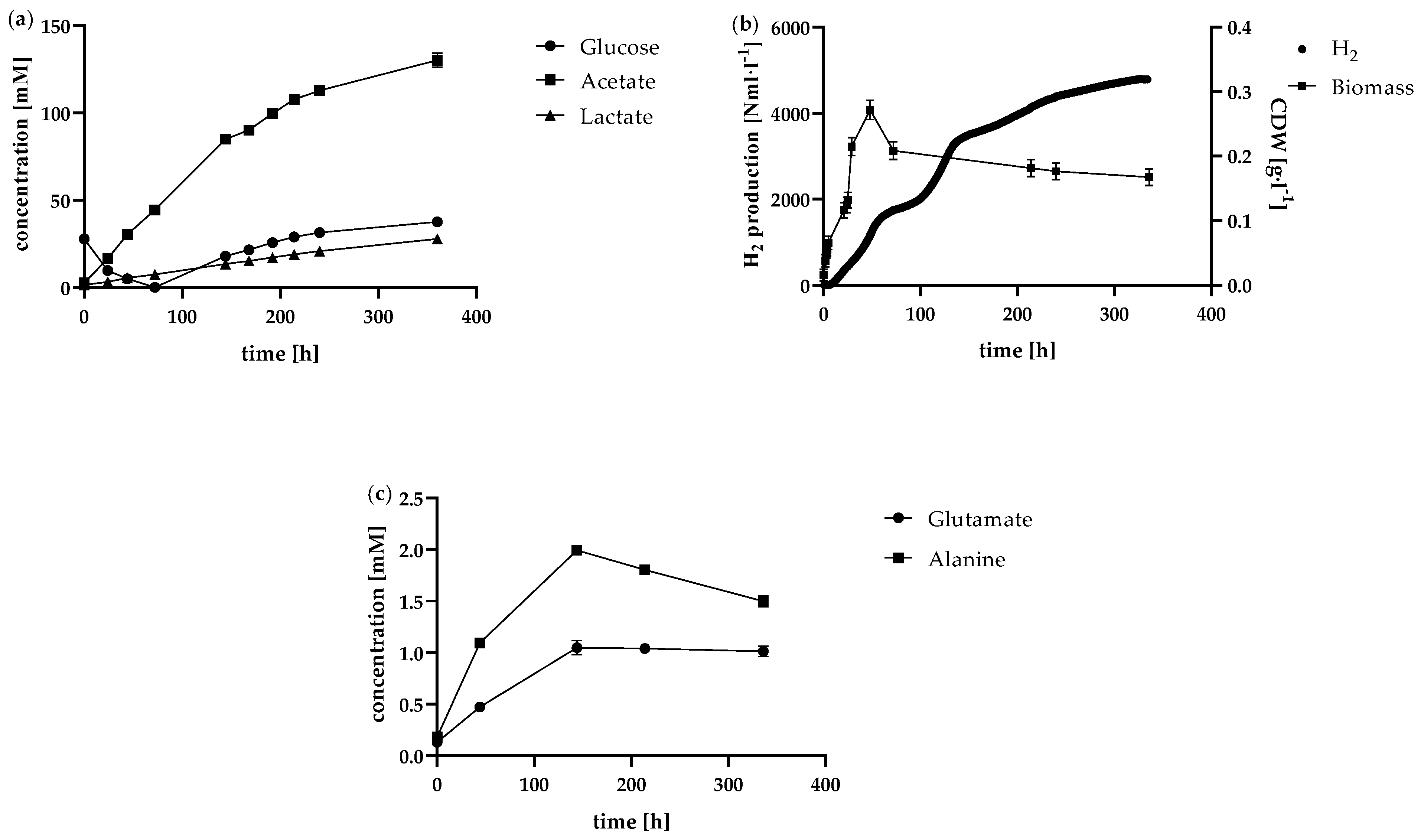

3.3. Fed-Batch

The fed-batch was initially allowed to run for 26 h in batch mode. The feed was subsequently run at 0.7 ml·h

−1. At 20-fold glucose feed concentration, this corresponded to a feed of 0.56 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1. The highest H

2 production rate during fed-batch was 49,2 ± 1,4 Nml·l

−1·h

−1, which was maintained for 4 h during this first feed phase. After 35 h of feed supply, the feed was paused to confirm that

T. neapolitana was able to completely metabolise the glucose present (

Figure 5a). As the glucose in the reactor was completely consumed, H

2 production dropped rapidly, as evident from the decline in the H₂ production curve (

Figure 5b). At 73 h, following the complete depletion of glucose in the reactor, the feed rate was increased to 1 ml·h⁻¹, corresponding to 0.793 mmol·l⁻¹·h⁻¹ of glucose. This adjustment initially led to an increase in hydrogen production, indicating that substrate availability directly influences H₂ output. However, despite the increased glucose feed rate, biomass concentration did not continue to rise. Instead, it slightly decreased and subsequently turned stationary. This suggests that a threshold in cell growth was reached, possibly due to limitations from by-product accumulation (e.g., acetate and lactate) or other inhibitory effects specific to the metabolic environment.

One possible reason for this is the accumulation of by-products such as acetate and lactate. The concentrations of these two components were similar to the batch approach in the first 48 h but then increased accordingly (

Figure 5a). The inhibitory effect of acetate had already been demonstrated by Dreschke

et al. [

17]. Another recent study focussed on the inhibition of acetate on hydrogen production by dark fermentation in a bacterial consortium. Here, increased acetate concentrations led to the lactate metabolic pathway being favoured and the composition of the dominant bacteria changed considerably [

32]. After 144 h, the concentration of acetate already exceeded with 84.9 ± 0.5 mM more than twice that of the batch approach at the end of fermentation (37.0 ± 0.2 mM). This was reflected in the productivity of the cells. On the one hand,

Figure 5a shows that the glucose concentration increased and the glucose consumption rate decreased accordingly. On the other hand, as H

2 production became noticeably slower and the biomass in the reactor decreased slightly. As the cells were no longer able to consume all the glucose supplied from the feed, the feed rate was consequently reduced from 1 ml·h

−1 to 0.7 ml·h

−1 after 146 h of fermentation time, corresponding to a glucose supply of 0.556 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1. A similar trend emerged as the fermentation time progressed. The glucose concentration in the reactor continued to increase, indicating that the glucose consumption rate was still below the feed rate. The by-products acetate and lactate continued to increase, possibly leading to increasing inhibition effects. The H

2 formation rate decreased to an average of 10.0 ± 3.0 Nml·l

−1·h

−1 between 146 h and 217 h. Since the pH value of the reactor was permanently regulated to pH 7.35, the inhibitory effect due to the accumulation of the acids produced cannot be attributed to pH reduction. In this case, the increasing ionic strength in the reactor could possibly have negative effects on the bacteria. Due to the continuing increase in glucose concentration, the feed rate was further adjusted downwards from time 217 h and changed to 0.5 ml·h

−1, corresponding to 0.396 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1. During this period of fermentation, H

2 was still produced, but at a lower production rate of 5.4 ± 3.1 Nml·l

−1·h

−1. Even at the lower feed rate, less glucose was metabolised than was supplied.

Interestingly, the concentrations of the by-products alanine and glutamate, which are depicted in

Figure 5c, show different courses. The concentration of the analysed amino acids were above 0 mM at the begin of fermentation, mainly due to the addition of yeast extract to the media. Here, an increase in concentration was observed from the start of fermentation until after 144 h fermentation time. Alanine increased from 0.18 ± 0.03 mM to 1.99 ± 0.04 mM and glutamate from 0.13 ± 0.03 mM to 1.05 ± 0.07 mM. Unlike the continuous accumulation observed for acetate and lactate, glutamate concentration stabilised, remaining relatively constant until the end of the fermentation process. Alanine, on the other hand, began to decrease, suggesting a shift from production to consumption. Considering the initial amino acid concentrations (e.g., 0.18 mM alanine from yeast extract at 0 h) and the low amino acid input from the feed, which primarily contained glucose in concentrated form, it is likely that the ongoing addition of amino acids was minimal. Accordingly, it is conceivable that

T. neapolitana consumed rather than produced amino acids in the later course of the fermentation, possibly as an adaptive response to prolonged fermentation conditions or limited nutrient availability.

An additional indication that the cells may have experienced inhibition in their metabolic pathway toward acetate and H₂ is the accumulation of another by-product ethanol. While ethanol could not be quantified in all batch or continuous approaches (c< 0.1 g·l

−1), the fed-batch showed an increasing ethanol concentration in the reactor over the course of 72 h fermentation time. The concentration profile is displayed in

Table 2 and reached its maximum of 0.61 ± 0.04 g·l

−1 at the end of fermentation. Although

T. neapolitana possesses the enzymatic system required for ethanol production, previous studies indicate that the activity of these enzymes is relatively low [

19]. This suggests that ethanol accumulation may occur under specific conditions, such as those present in the fed-batch process, where inhibition of primary pathways (e.g., acetate and hydrogen production) prompts the cells to redirect metabolism toward ethanol as an alternative by-product. H₂ and CO₂ are unlikely to cause product inhibition, as they readily escape as gases and are continuously expelled through N₂ sparging. However, dissolved by-products that accumulate in the liquid phase can reach inhibitory concentrations, potentially leading to a metabolic shift towards ethanol production. This accumulation of liquid-phase inhibitors may alter the metabolic balance, favouring ethanol as an alternative by-product under higher concentration conditions. As H

2 is produced in the same metabolic pathway as acetate, inhibition of acetate production also results in lower H

2 production. It would therefore be advisable to plan for in-situ product removal of acetate if longer lasting H

2 production in the fed-batch is intended.

In addition to the expected results that in the course of a batch process, the viability decreased with time and the running out of the substrate, the same could also be determined for the fed-batch. Here, the consumption of the substrate was not the limiting factor that caused the viability to decrease over time (

Figure 3). The inhibition caused by the accumulation of by-products inhibited the cells in their metabolism and growth. It is likely that in this case it was not just the by-products, but the overall ionic strength of the medium. This naturally also increased due to the accumulation of by-products. Various experiments with different buffer concentrations have already shown that increased buffer concentrations might have inhibitory effects on

T. neapolitana [

45]. Thus, by-product enrichment and the associated increase in ionic strength could also have a negative effect on

T. neapolitana. In any case, it can be deduced from the viability profile that a fed-batch can no longer maintain high viability rates over several weeks under the tested conditions. While the viability was still relatively high at 84% after 144 h fermentation time, it dropped to only 40% after 214 h. After 336 h, viability was at its lowest at 38%. It should be noted that only whole cells could be detected as living or dead by staining. Accordingly, cells that died and were completely lysed during fermentation could not be detected. As the fermentation lasted a total of two weeks and low cell viabilities were present at later times, it can be assumed that several cells were already lysed during fermentation.

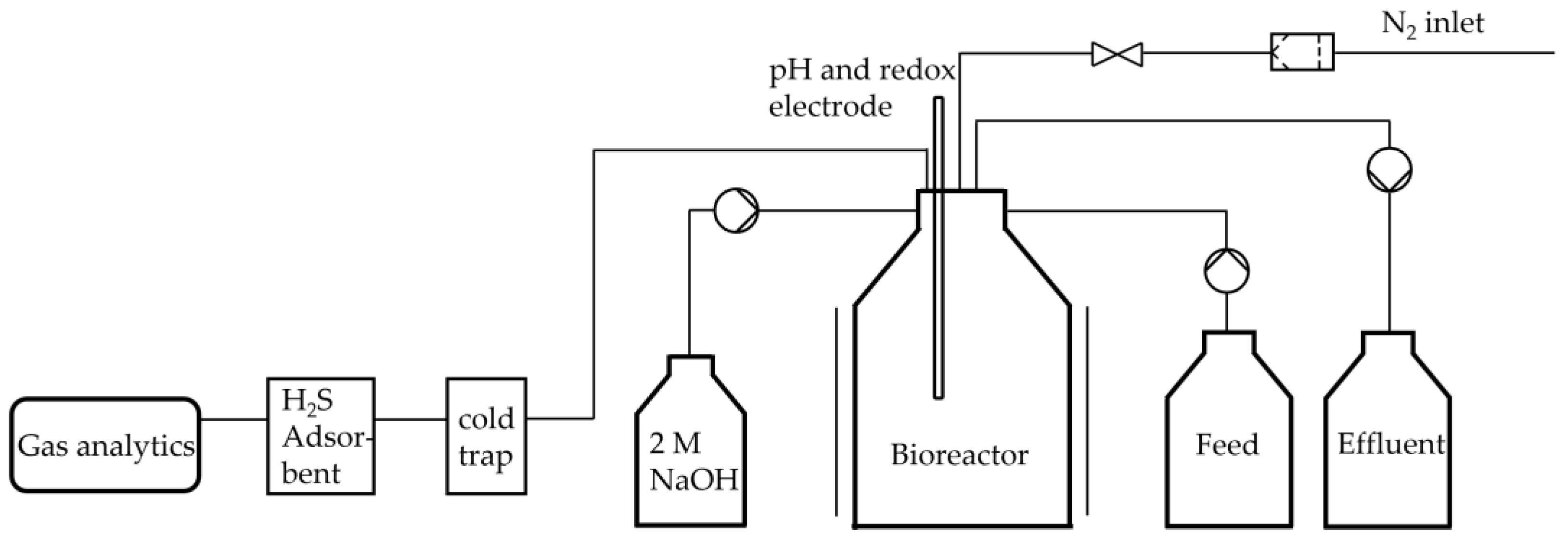

3.4. Continuous Fermentation

Due to the limitations observed in the fed-batch system, especially concerning extended fermentation times, a continuous bioreactor was implemented following the setup outlined in

Figure 1. The continuous supply of fresh medium and removal of used medium ensured that no by-products could accumulate in the medium in higher concentrations. The dilution rates of 0.03 h

−1, 0.05 h

−1, 0.07 h

−1 and 0.1 h

−1 tested here are based on the maximum observed glucose consumption rates of the batch runs. Since the feed had the same composition as the TBGY media described, the glucose feed rates were accordingly 0.833 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1, 1.388 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1, 1.943 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1 and 2.775 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1. The glucose concentration in the reactor increased from 0.11 ± 0.05 g·l

−1 to 1.08 ± 0.03 g·l

−1 at a dilution rate of 0.1 h

−1. This indicates that the critical dilution rate was already exceeded. Accordingly, a steady state could not be achieved. Steady state was observed for all other tested dilution rates. The steady state was characterised by the fact that the glucose concentration in the reactor remained constantly low and fluctuated by less than 0.1 g·l

−1. It can therefore be assumed that the substrate supplied was almost consumed. The highest glucose consumption rate in chemostat mode was 2.19 ± 0.05 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1. This observation matches the results of the maximum glucose consumption rate, which could be determined in batch fermentations. Here, a glucose consumption rate of 2.58 ± 0.16 mmol

glucose·l

−1·h

−1 could only be determined for the batch with an increased starting cell concentration under optimum conditions. This is slightly below the glucose supply rate at the 0.1 h

−1 dilution rate in continuous operation. Theoretically, based on the maximum growth rate, which was µ

max=0.77 ± 0.06 h

−1 during the batch fermentation in exponential growth phase, even considerably higher dilution rates would be conceivable. Several factors likely contribute to the observed discrepancy between the maximum growth rate and the achievable dilution rate in continuous operation. One primary factor is the significantly higher cell density in the steady state of the continuous reactor compared to the exponential growth phase in batch mode. The biomass grew between 0.023 ± 0.009 g·l

−1 and 0.085 ± 0.011 g·l

−1 during the exponential growth phase. The continuous reactor with a dilution rate of 0.03 h

−1 had an average biomass concentration of 0.550 ± 0.065 g·l

−1 during the steady state. The increased biomass concentration could therefore prevent the cells from continuing to grow at the maximum possible growth rate, as the availability of nutrients might be limited, or the cell density itself inhibits further growth. This also indicates that, as already mentioned, the maximum growth rate can vary greatly under different conditions and cannot be maintained for long. Accordingly, the specific growth rate can be significantly lower for a longer period of time. With an experimentally determined maximum dilution rate D=0.07 h

−1, this is noticeably higher than the prognosed optimal dilution rate of D=0.041 h

−1 predicted by Frascari

et al. for dissolved cells, which is based on substrate to product and biomass conversion rate and yield [

40]. The results are shown in

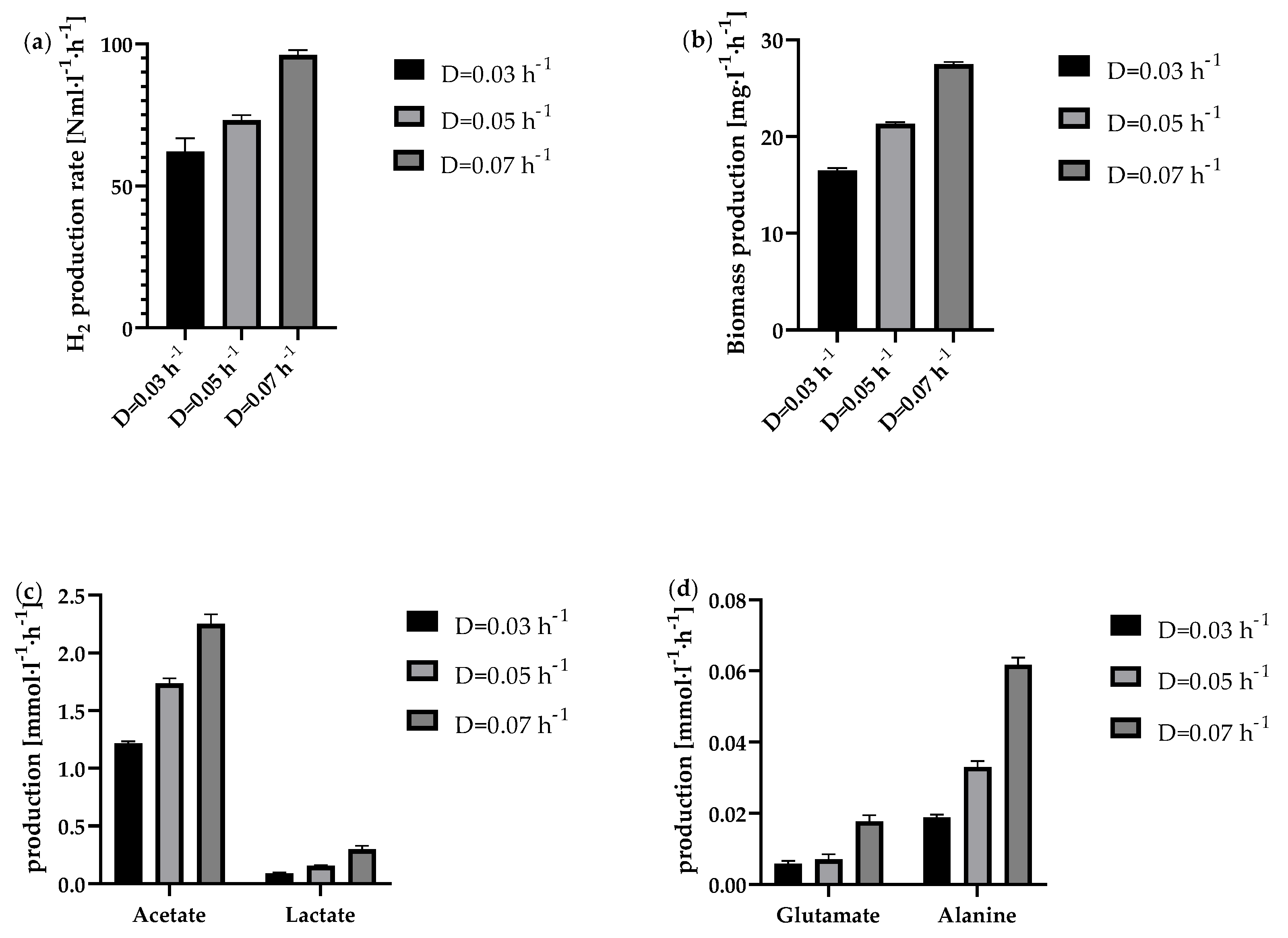

Figure 6a-d.

The H2 production rate was overall consistent, indicating a stable steady state. The biomass concentration remained constant as well. So was the viability of the cells in continuous operation very high at steady state for all dilution rates tested and averaged 97 ± 3%. Thus, in contrast to the batch and fed-batch approaches, there was no recognisable downward trend over the entire steady state period. This indicates that suitable fermentation conditions were generally available for the cells at all different dilution rates. But as the cells are also permanently rinsed out during the continuous process, the cells are only in the bioreactor for a certain time depending on the respective dilution rate. In this case, the residence time was 33.3 h (D=0.03 h−1), 20.0 h (D=0.05 h−1) or 14.3 h (D=0.07 h−1). For periods of time in this range, a comparably high viability was also observed at the start of fermentation in the batch or fed-batch. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that over the period of fermentation, some cells lysed as well. However, as soon as they lyse, they were no longer detectable.

As depicted in

Figure 6a, the H

2 production rate increased with increasing dilution rate. While at D=0.03 h

−1 it was 62.1 ± 4.7 Nml·l

−1·h

−1, at D=0.07 h

−1 it was even 96.1 ± 1.7 Nml·l

−1·h

−1 at steady state. An almost comparable increase in biomass production was also observed at higher dilution rates (

Figure 6b). Reasons for this are the higher availability of glucose at higher dilution rates. For the by-products analysed here, a trend of increasing production rate with increasing dilution rate could also be observed. However, the ratio of acetate to lactate production shifted slightly in favour of lactate as the dilution rate increased. While at the lowest dilution rate D=0.03 h

−1 the ratio was 13.4 acetate : 1 lactate, at D=0.05 h

−1 this ratio fell to 11.1 acetate : 1 lactate. At D=0.07 h

−1, the ratio was even decreased to 7.5 acetate : 1 lactate. As the metabolic pathway to lactate is in competition with the H

2 metabolic pathway [

14], the lowest possible lactate production rate should usually be aimed for. However, it could also be shown that lactate production does not necessarily have to reduce the H

2 yield, as

T. neapolitana, or the strain

T. neapolitana cf capnolactica (DSM33003) used in some cases, appears to be able to form lactate from acetate and CO

2 without negatively affecting H

2 production [

16,

46].

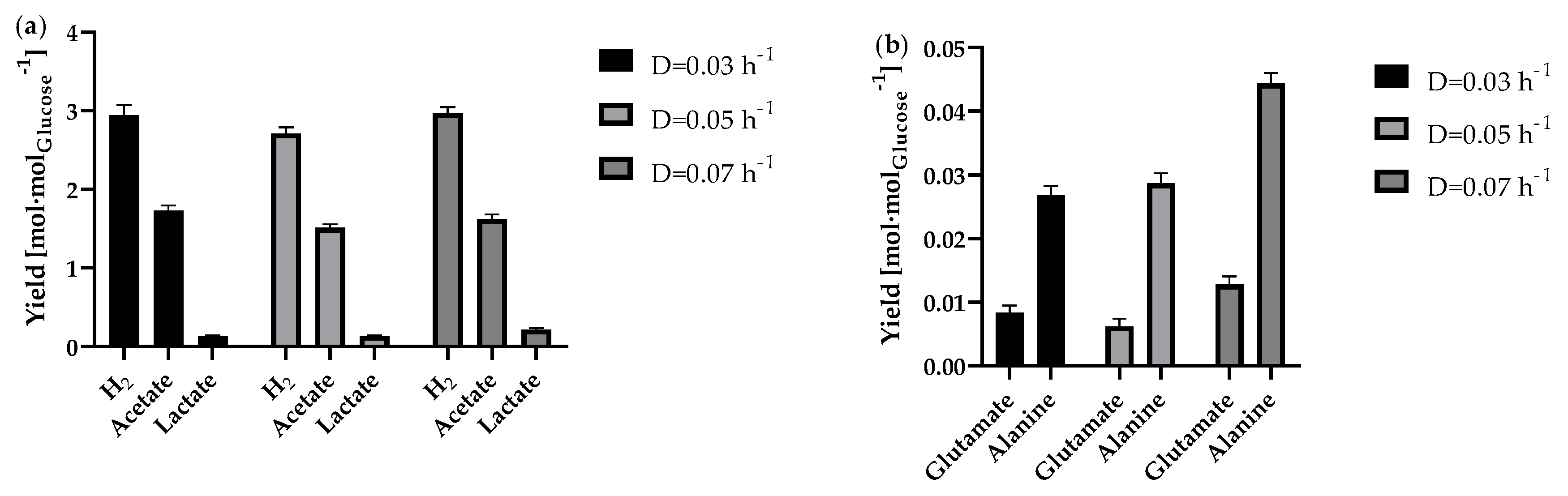

Interestingly, a look at the yields for all stable dilution rates showed hardly any differences in terms of product yields. As shown in

Figure 7a, the H

2 yield at steady state for the dilution rates tested was between 2.7 ± 0.1 mol

H2·mol

glucose−1 (D=0.05 h

−1) and 3.0 ± 0.1 mol

H2·mol

glucose−1 (D=0.07 h

−1). The yields also remained constant for the steady state period. The yields for acetate and lactate also showed hardly any differences. Only the yields of the produced amino acids alanine and glutamate showed a slightly increased yield at the dilution rate of D=0.07 h

−1 (

Figure 7b). The calculated yield of 0.044 ± 0.002 mol

alanine·mol

glucose−1 is close to the alanine yield reported before [

47]. However, among other things, production of alanine ensured the H

2 yield was below the theoretical maximum. This is because it has already been shown that both pyruvate and reduction equivalents are required for alanine production [

16,

20,

48]. As a consequence, these components are not available to the maximum possible extent for H

2 production. On the other hand, it could also be shown that alanine, among others, can be used as a nutrient source [

49], which is in line with the results from the fed-batch as described above. Accordingly, the use of pyruvate and reduction equivalents for alanine production could be counteracted by specifically adding small amounts of alanine to the fermentation.

One possible approach to improving the system would be to introduce a membrane that retains the cells in the bioreactor. It has already been shown that increasing the biomass concentration can lead to a significantly faster metabolisation of glucose [

47]. Higher biomass concentration could also overcome possible inhibition because of higher glucose concentration in the feed. As shown by Dreschke

et al. increased glucose concentration from 11.1 to 41.6 mM in the feed, reduced noticeably the hydrogen yield [

17]. A more efficient metabolisation of glucose would bring many advantages, especially with regard to scale-up. In this way, higher throughputs could also be achieved with lower volumes, making the entire process more cost-effective.

Another option for optimising the continuous system to enable an increase in the dilution rate would be to immobilise the cells in the reactor. Successful approaches for this have already been demonstrated by [

36,

40]. This would prevent a washout, even at higher dilution rates. However, it would have to be ensured that the substrate is as favourably accessible as possible for the cells and is metabolised as quickly as possible.

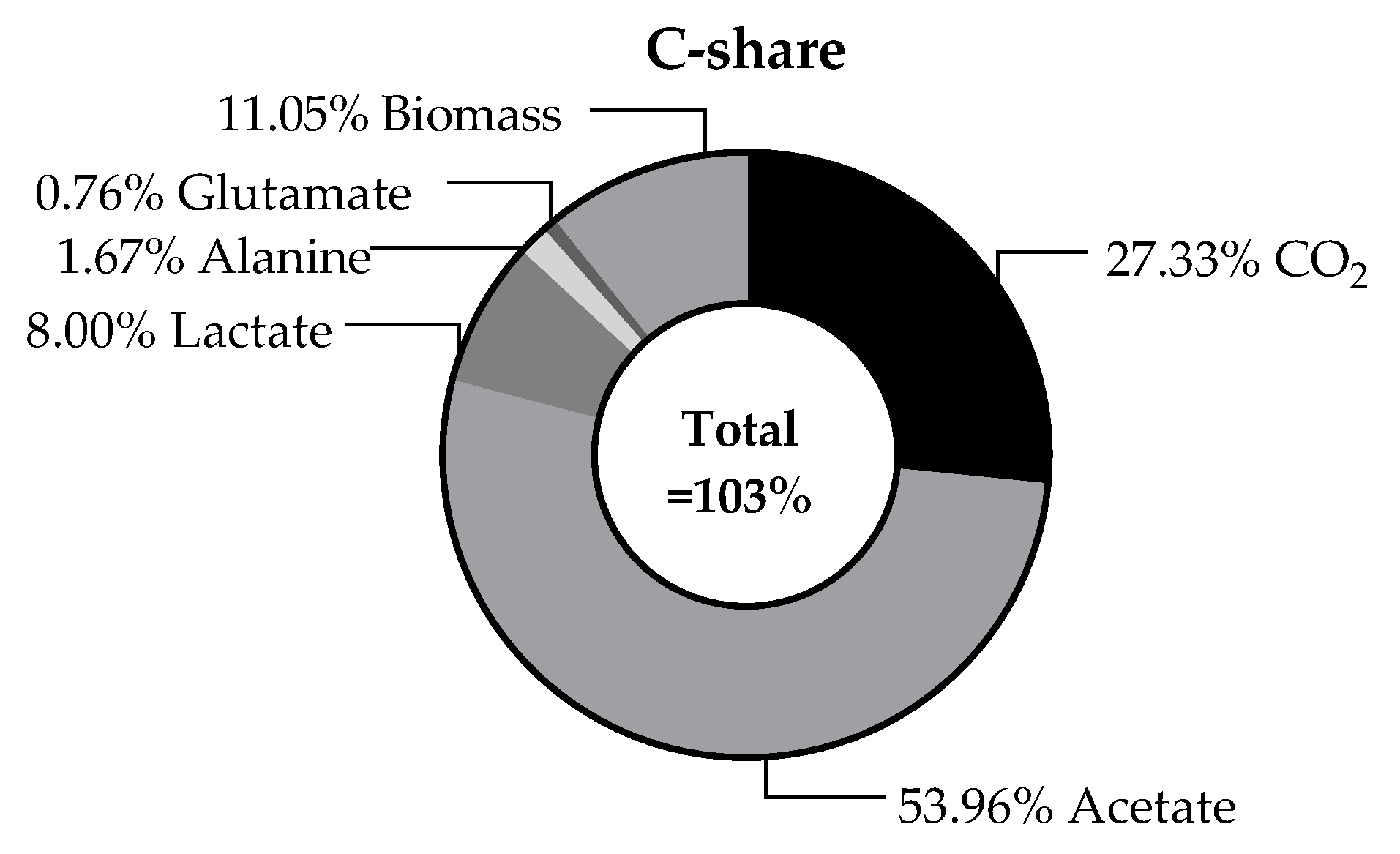

In addition to the individual production rates in a continuous process, the carbon balance is an important aspect to consider. This can provide information on whether all the main products produced have already been identified and quantified. Furthermore, an overview of the proportions of the products produced can provide information on whether contamination or a shift in metabolism has occurred over time.

The carbon balance, which is illustrates in

Figure 8, refers to the substrate consumption and the resulting products in continuous operation at steady state. A value of 45.9% carbon of the total cell dry weight was determined empirically for

T. maritima [

50]. Here, a C content of 38.7 ± 0.2% was determined experimentally for

T. neapolitana. For this purpose, the dried cell biomass from the fermenter was analysed as part of a C-H-N analysis using a Vario EL cube elemental analyser. It is initially noticeable that the overall balance of 102.8% is above the theoretical maximum. Compared to the carbon balance of Munro

et al. [

14] the value is quite similar, though. This could be explained by the assumption that the small amounts of yeast extract present in the media were also used to synthesise biomass. However, the balance suggests that all carbon-containing products that are formed in significant quantities have been found and quantified here. Overall, acetate was found to make up the largest proportion of carbon (54.0%). This was followed by CO

2 (27.3%) and biomass (11.1%). As acetate is produced in the same metabolic pathway as H

2, a correspondingly high acetate production is also to be expected with a high H

2 production [

48,

51]. Since the carbon that was used at the beginning of the process could be recovered in the form of various products, possible further utilisation options are quite calculable. For example, the biomass can be used as a favourable substrate for further fermentation processes. With the help of the CO

2 gas produced, it is even conceivable to subsequently produce methanol from CO

2 and H

2. Methanol would be a suitable way of both fixing the CO

2 and enabling the H

2 to be stored and transported more easily [

52].